User login

Red painful nodules in a hospitalized patient

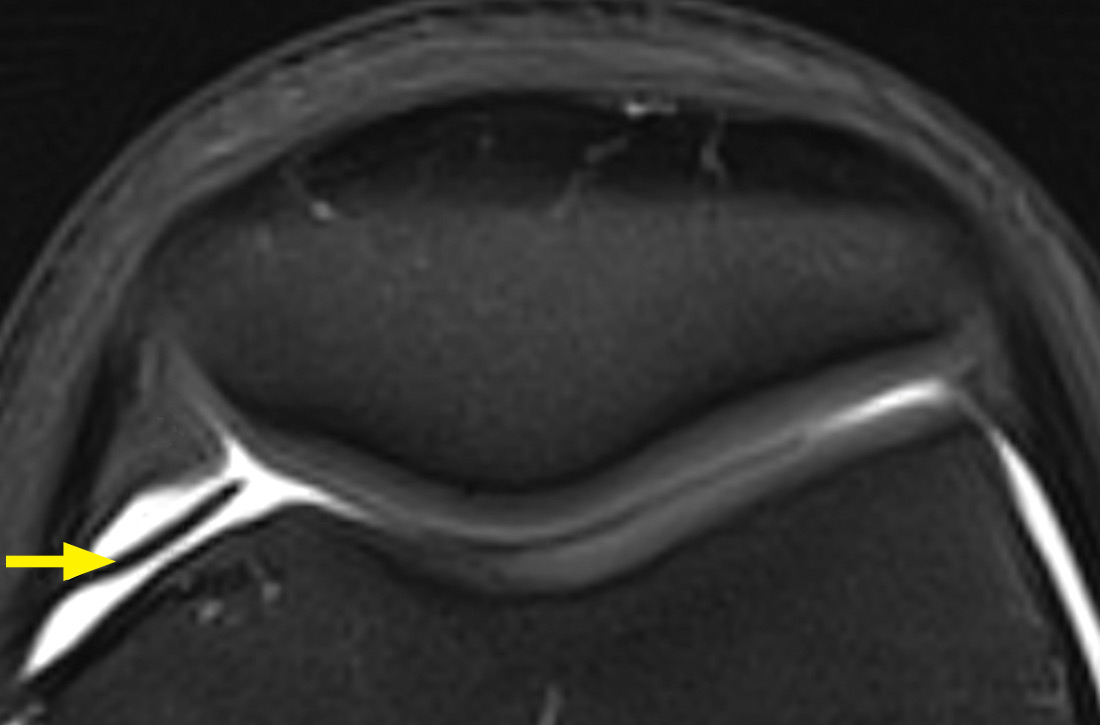

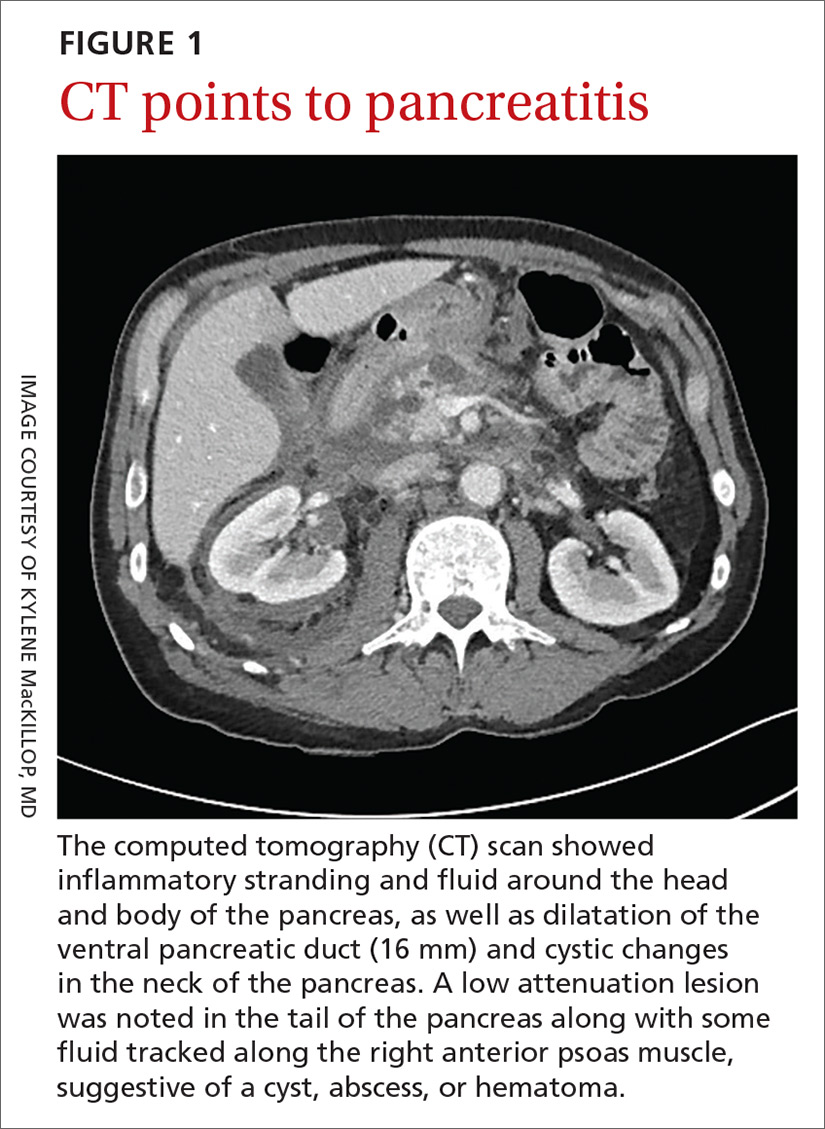

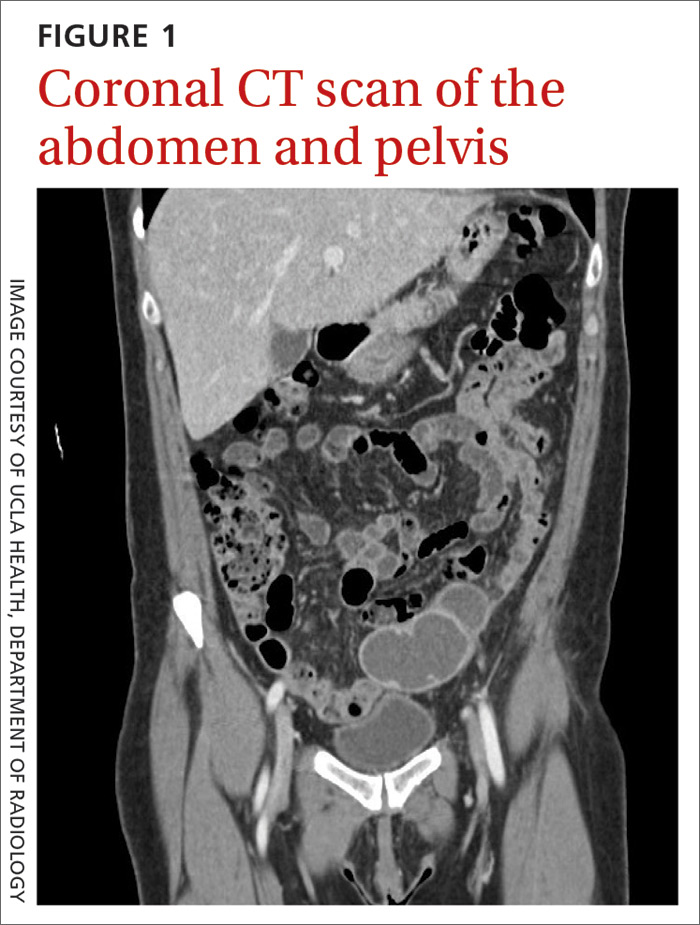

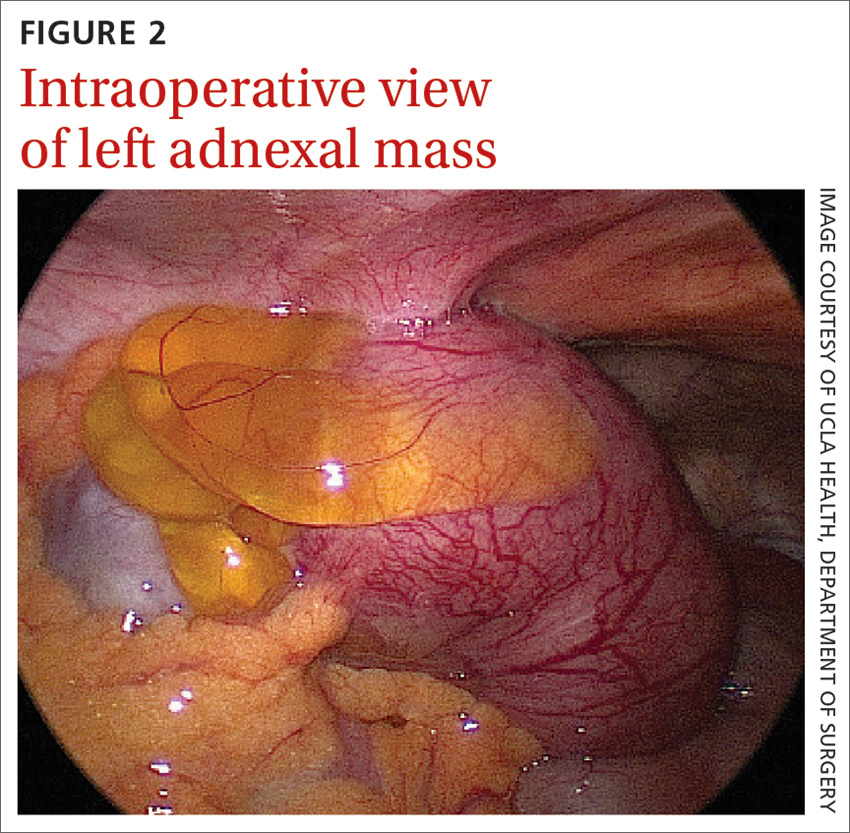

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

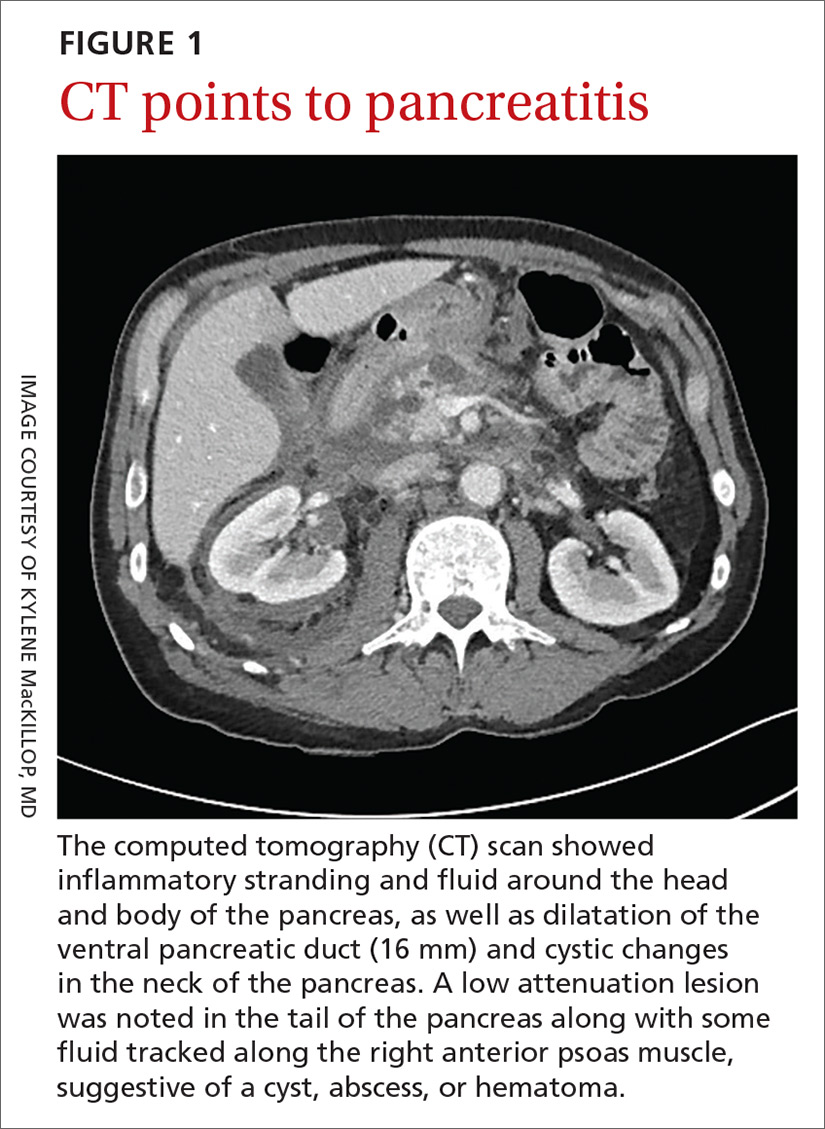

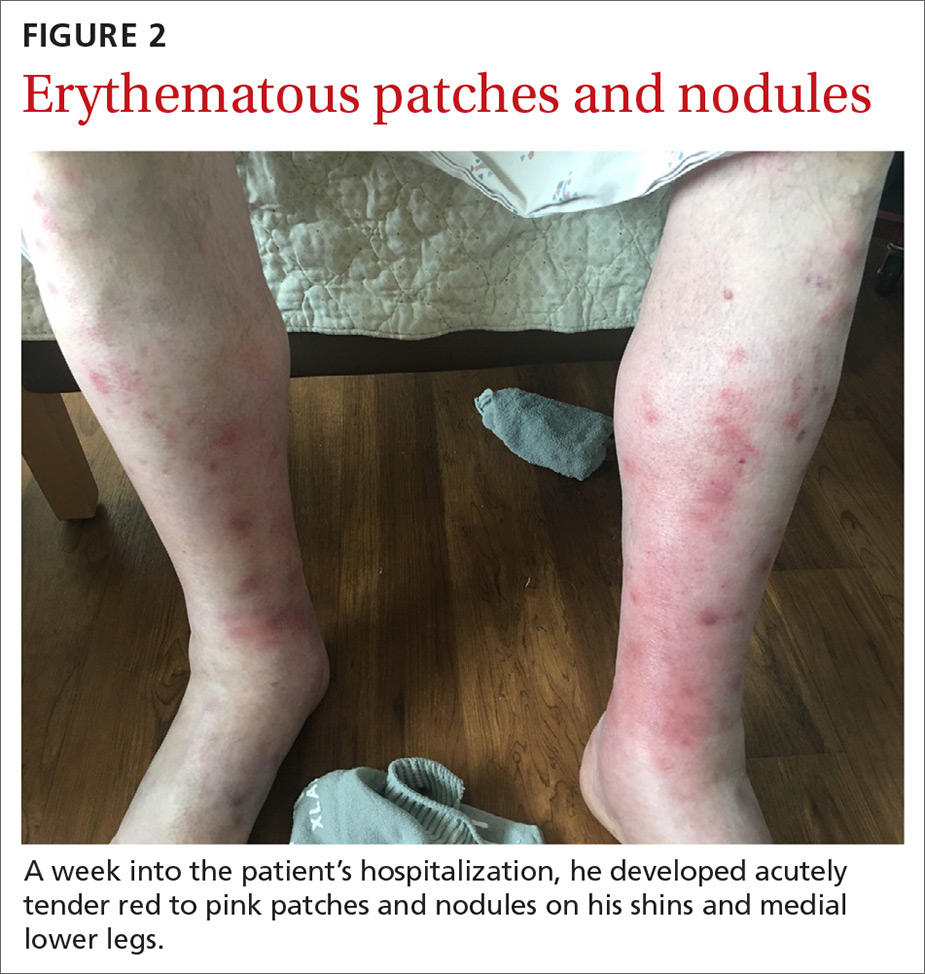

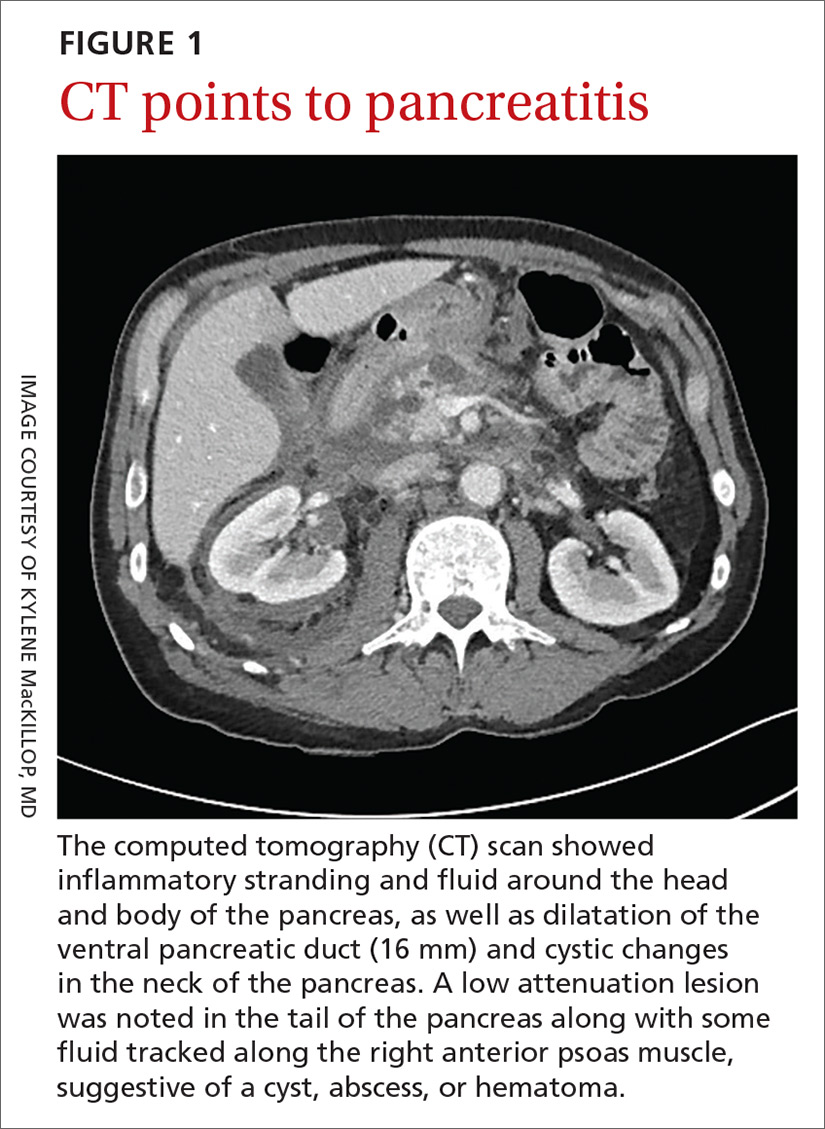

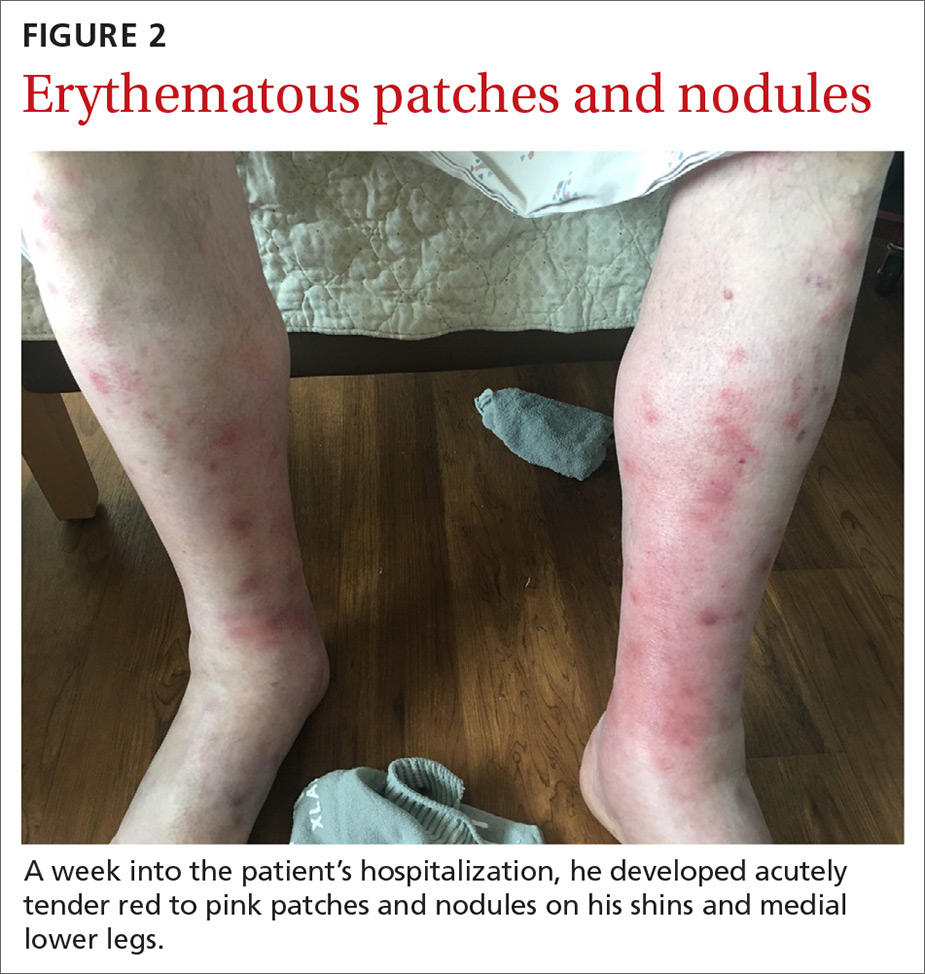

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

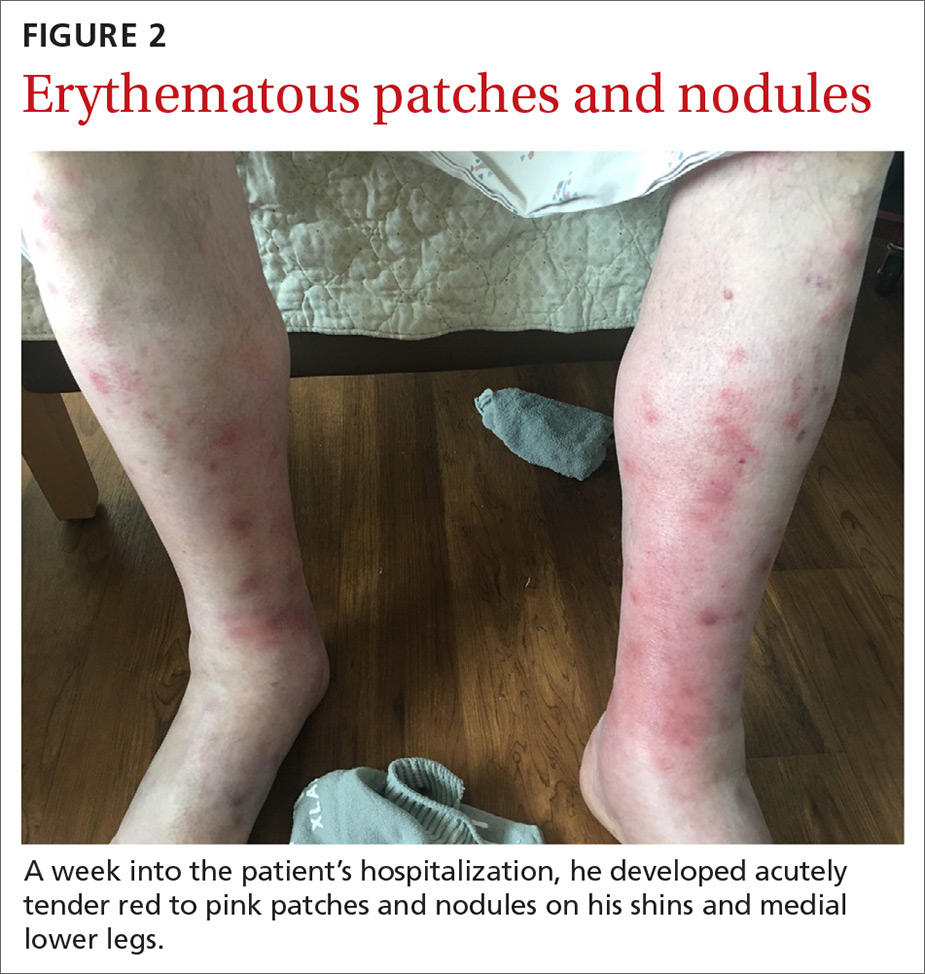

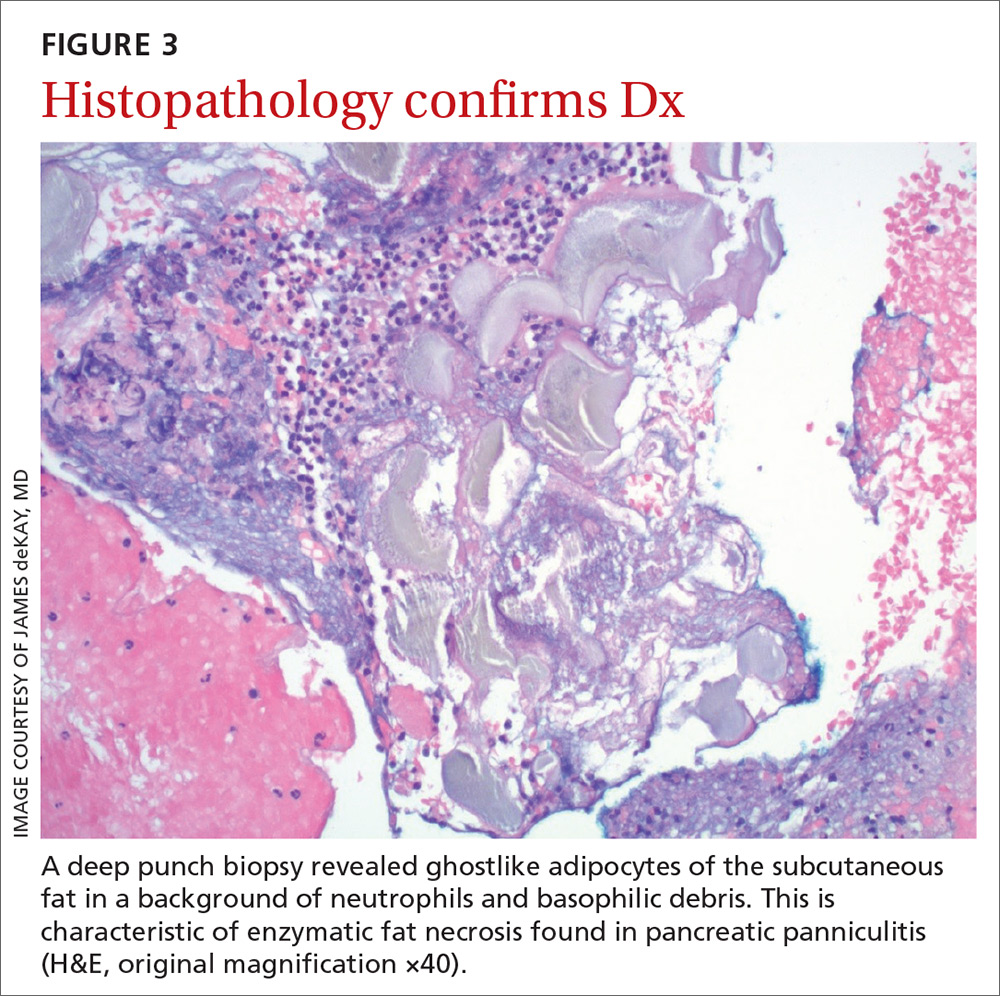

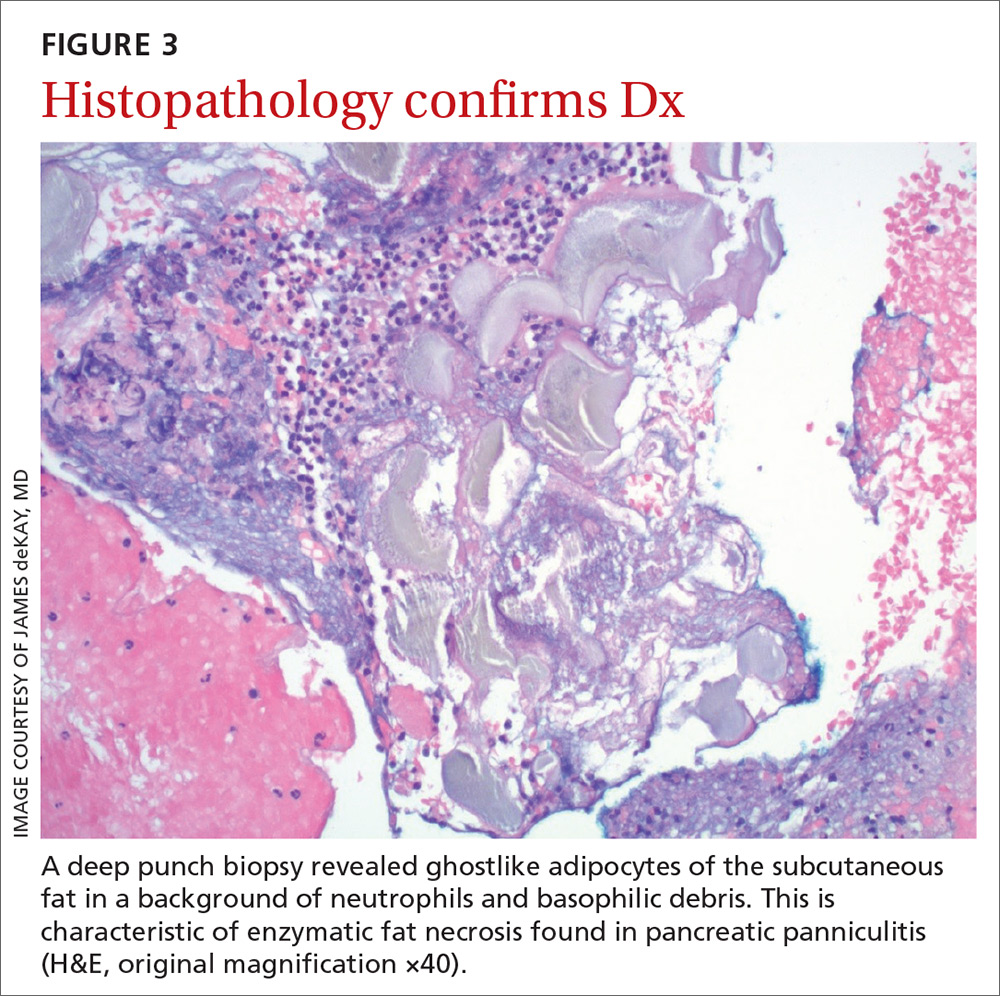

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

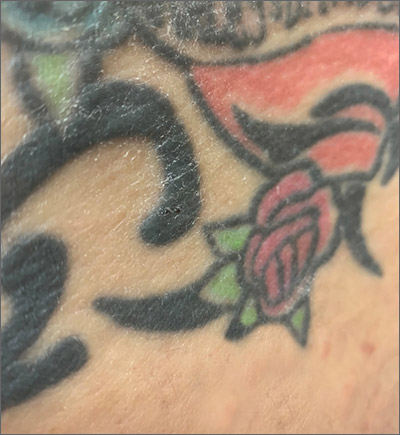

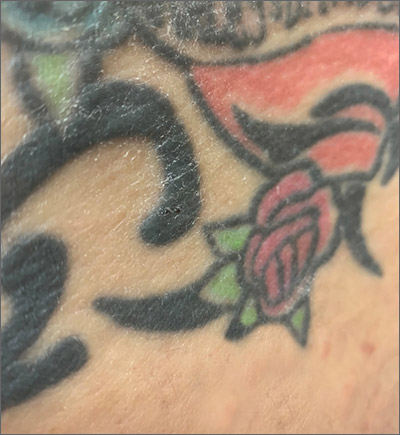

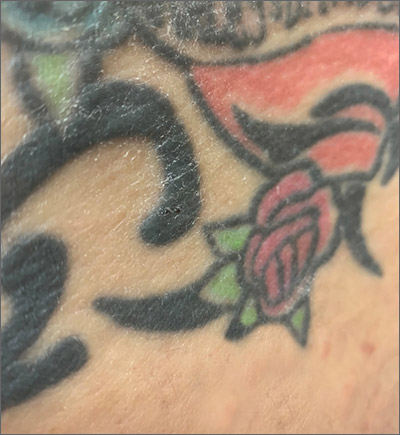

Thickening of tattoo

A punch biopsy to rule out other causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms confirmed tattoo granulomas with sarcoidal nodules.

Tattoo granulomas can occur years after the initial placement of the tattoo. They appear, as in this case, as a thickening of the tattooed skin due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the foreign body. It has been more commonly reported in yellow and red inks but also has been reported in black ink. Sarcoidosis has been diagnosed based on occurrence in tattoos, but in this case, the patient’s calcium level was normal, chest X-ray showed no signs of adenopathy, and she had no symptoms of sarcoidosis such as fevers, chills, night sweats, or fatigue. Thus, no further work-up for systemic sarcoidosis was performed.

During the patient’s biopsy visit, she was started on oral montelukast 10 mg/d for a possible allergic reaction to the tattoo ink. By the time pathology results returned 1 week later, her itching and puffiness had resolved. Montelukast is a leukotriene antagonist that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in asthma and allergic rhinitis; it is also used off label for chronic urticaria.

Usual therapies for tattoo granulomas include intralesional steroid injections or laser therapy to destroy the pigment. This patient had a large number of tattoos that would have required extensive laser therapy destruction of the pigment or numerous intralesional injections. Since she was no longer symptomatic, she elected to continue on the montelukast. She was cautioned about the possible development of suicidal ideation on this medication and was instructed to seek care if any such thoughts occurred.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Tittelbach J, Peckruhn M, Schliemann S, et al. Sarcoidal foreign body reaction as a severe side-effect to permanent makeup: successful treatment with intralesional triamcinolone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:458-459.

A punch biopsy to rule out other causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms confirmed tattoo granulomas with sarcoidal nodules.

Tattoo granulomas can occur years after the initial placement of the tattoo. They appear, as in this case, as a thickening of the tattooed skin due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the foreign body. It has been more commonly reported in yellow and red inks but also has been reported in black ink. Sarcoidosis has been diagnosed based on occurrence in tattoos, but in this case, the patient’s calcium level was normal, chest X-ray showed no signs of adenopathy, and she had no symptoms of sarcoidosis such as fevers, chills, night sweats, or fatigue. Thus, no further work-up for systemic sarcoidosis was performed.

During the patient’s biopsy visit, she was started on oral montelukast 10 mg/d for a possible allergic reaction to the tattoo ink. By the time pathology results returned 1 week later, her itching and puffiness had resolved. Montelukast is a leukotriene antagonist that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in asthma and allergic rhinitis; it is also used off label for chronic urticaria.

Usual therapies for tattoo granulomas include intralesional steroid injections or laser therapy to destroy the pigment. This patient had a large number of tattoos that would have required extensive laser therapy destruction of the pigment or numerous intralesional injections. Since she was no longer symptomatic, she elected to continue on the montelukast. She was cautioned about the possible development of suicidal ideation on this medication and was instructed to seek care if any such thoughts occurred.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A punch biopsy to rule out other causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms confirmed tattoo granulomas with sarcoidal nodules.

Tattoo granulomas can occur years after the initial placement of the tattoo. They appear, as in this case, as a thickening of the tattooed skin due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the foreign body. It has been more commonly reported in yellow and red inks but also has been reported in black ink. Sarcoidosis has been diagnosed based on occurrence in tattoos, but in this case, the patient’s calcium level was normal, chest X-ray showed no signs of adenopathy, and she had no symptoms of sarcoidosis such as fevers, chills, night sweats, or fatigue. Thus, no further work-up for systemic sarcoidosis was performed.

During the patient’s biopsy visit, she was started on oral montelukast 10 mg/d for a possible allergic reaction to the tattoo ink. By the time pathology results returned 1 week later, her itching and puffiness had resolved. Montelukast is a leukotriene antagonist that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in asthma and allergic rhinitis; it is also used off label for chronic urticaria.

Usual therapies for tattoo granulomas include intralesional steroid injections or laser therapy to destroy the pigment. This patient had a large number of tattoos that would have required extensive laser therapy destruction of the pigment or numerous intralesional injections. Since she was no longer symptomatic, she elected to continue on the montelukast. She was cautioned about the possible development of suicidal ideation on this medication and was instructed to seek care if any such thoughts occurred.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Tittelbach J, Peckruhn M, Schliemann S, et al. Sarcoidal foreign body reaction as a severe side-effect to permanent makeup: successful treatment with intralesional triamcinolone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:458-459.

Tittelbach J, Peckruhn M, Schliemann S, et al. Sarcoidal foreign body reaction as a severe side-effect to permanent makeup: successful treatment with intralesional triamcinolone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:458-459.

Vesicles on the thigh

On very close inspection, the physician noted translucent chambers within each vesicle, and within each chamber there was a horizontal line (parallel to the floor) separating serum-colored fluid from dark blood. This unique appearance prompted the physician to diagnose lymphangioma circumscriptum in this patient.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a rare type of microcytic lymphatic malformation most commonly found on the shoulders, limbs, axilla, and tongue that may enlarge during puberty. The clustered vesicles are firm. Vesicles can be red, brown, or straw colored in appearance and are focal to widespread; rarely, they may bleed or become infected. Their appearance has been compared to frog spawn.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is benign and requires no treatment. Any suspected infection could be treated with antibiotics. If removal is desired for cosmesis or functional treatment, areas may be treated with dermabrasion, sclerotherapy, laser ablation, or excision if feasible. Lymphangioma circumscriptum tends to recur in time and appropriate anticipatory guidance is key.

This patient was treated with sclerotherapy using hypertonic saline that was injected monthly for 3 months. The physician injected a 30-g needle into the broadest ectatic chambers after each area was anesthetized with lidocaine. The patient tolerated the injections well, and the treated areas resolved as slightly hypopigmented macules. No recurrence was noted at posttreatment follow-up 1 year later.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444.

On very close inspection, the physician noted translucent chambers within each vesicle, and within each chamber there was a horizontal line (parallel to the floor) separating serum-colored fluid from dark blood. This unique appearance prompted the physician to diagnose lymphangioma circumscriptum in this patient.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a rare type of microcytic lymphatic malformation most commonly found on the shoulders, limbs, axilla, and tongue that may enlarge during puberty. The clustered vesicles are firm. Vesicles can be red, brown, or straw colored in appearance and are focal to widespread; rarely, they may bleed or become infected. Their appearance has been compared to frog spawn.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is benign and requires no treatment. Any suspected infection could be treated with antibiotics. If removal is desired for cosmesis or functional treatment, areas may be treated with dermabrasion, sclerotherapy, laser ablation, or excision if feasible. Lymphangioma circumscriptum tends to recur in time and appropriate anticipatory guidance is key.

This patient was treated with sclerotherapy using hypertonic saline that was injected monthly for 3 months. The physician injected a 30-g needle into the broadest ectatic chambers after each area was anesthetized with lidocaine. The patient tolerated the injections well, and the treated areas resolved as slightly hypopigmented macules. No recurrence was noted at posttreatment follow-up 1 year later.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

On very close inspection, the physician noted translucent chambers within each vesicle, and within each chamber there was a horizontal line (parallel to the floor) separating serum-colored fluid from dark blood. This unique appearance prompted the physician to diagnose lymphangioma circumscriptum in this patient.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is a rare type of microcytic lymphatic malformation most commonly found on the shoulders, limbs, axilla, and tongue that may enlarge during puberty. The clustered vesicles are firm. Vesicles can be red, brown, or straw colored in appearance and are focal to widespread; rarely, they may bleed or become infected. Their appearance has been compared to frog spawn.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum is benign and requires no treatment. Any suspected infection could be treated with antibiotics. If removal is desired for cosmesis or functional treatment, areas may be treated with dermabrasion, sclerotherapy, laser ablation, or excision if feasible. Lymphangioma circumscriptum tends to recur in time and appropriate anticipatory guidance is key.

This patient was treated with sclerotherapy using hypertonic saline that was injected monthly for 3 months. The physician injected a 30-g needle into the broadest ectatic chambers after each area was anesthetized with lidocaine. The patient tolerated the injections well, and the treated areas resolved as slightly hypopigmented macules. No recurrence was noted at posttreatment follow-up 1 year later.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444.

Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444.

Forehead cyst

Upon palpation, the physician noted a strong pulse consistent with a traumatic arteriovenous fistula (in this case involving the superficial temporal artery). This finding, combined with the cyst’s appearance and the patient’s history, led the physician conclude that this was an epidermoid (sebaceous) cyst. (Prior to palpation, the visual differential diagnosis included dermoid cyst, lipoma, trichilemmal or epidermoid cyst, and foreign body granuloma.)

Cystic nodules on the forehead and midline deserve close scrutiny. This author has seen 3 similar cases in 10 years of daily dermatology consultative practice that have involved the superficial temporal artery and a history of head trauma. Each case had been stable for many months before presentation and had been incorrectly identified as a more common benign cyst.

In this particular case, the planned procedure in the outpatient setting was cancelled and the patient was referred to Vascular Surgery, where surgeons were planning to perform a ligation of the superficial temporal artery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Matsumoto H, Yamaura I, Yoshida Y. Identity of growing pulsatile mass lesion of the scalp after blunt head injury: case reports and literature review. Trauma Case Rep. 2018;17:43-47.

Upon palpation, the physician noted a strong pulse consistent with a traumatic arteriovenous fistula (in this case involving the superficial temporal artery). This finding, combined with the cyst’s appearance and the patient’s history, led the physician conclude that this was an epidermoid (sebaceous) cyst. (Prior to palpation, the visual differential diagnosis included dermoid cyst, lipoma, trichilemmal or epidermoid cyst, and foreign body granuloma.)

Cystic nodules on the forehead and midline deserve close scrutiny. This author has seen 3 similar cases in 10 years of daily dermatology consultative practice that have involved the superficial temporal artery and a history of head trauma. Each case had been stable for many months before presentation and had been incorrectly identified as a more common benign cyst.

In this particular case, the planned procedure in the outpatient setting was cancelled and the patient was referred to Vascular Surgery, where surgeons were planning to perform a ligation of the superficial temporal artery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Upon palpation, the physician noted a strong pulse consistent with a traumatic arteriovenous fistula (in this case involving the superficial temporal artery). This finding, combined with the cyst’s appearance and the patient’s history, led the physician conclude that this was an epidermoid (sebaceous) cyst. (Prior to palpation, the visual differential diagnosis included dermoid cyst, lipoma, trichilemmal or epidermoid cyst, and foreign body granuloma.)

Cystic nodules on the forehead and midline deserve close scrutiny. This author has seen 3 similar cases in 10 years of daily dermatology consultative practice that have involved the superficial temporal artery and a history of head trauma. Each case had been stable for many months before presentation and had been incorrectly identified as a more common benign cyst.

In this particular case, the planned procedure in the outpatient setting was cancelled and the patient was referred to Vascular Surgery, where surgeons were planning to perform a ligation of the superficial temporal artery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Matsumoto H, Yamaura I, Yoshida Y. Identity of growing pulsatile mass lesion of the scalp after blunt head injury: case reports and literature review. Trauma Case Rep. 2018;17:43-47.

Matsumoto H, Yamaura I, Yoshida Y. Identity of growing pulsatile mass lesion of the scalp after blunt head injury: case reports and literature review. Trauma Case Rep. 2018;17:43-47.

Enlarging scalp plaque

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae.

Follicular keloidalis, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. It also may be a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

In the earliest stages, when only small inflammatory papules are present, patients should be instructed not to cut their hair shorter than 0.25-in long to avoid hair retention. Also, topical clindamycin lotion or topical chlorhexidine solution may serve as sufficient treatment. As the disease progresses, oral doxycycline 100 mg bid, combination rifampin 300 mg bid and clindamycin 300 mg bid for 3 months, or isotretinoin 1 mg/kg daily for 6 to 8 months are medical therapeutic options. Procedural options include radiation and laser hair removal.

In this patient, trials of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL helped to flatten the plaque, but hair loss persisted. Ultimately, he was referred to Plastic Surgery for excision and was treated for several months with doxycycline 100 mg bid and monitored for recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017. pii: bcr-2017-222222. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222222.

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae.

Follicular keloidalis, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. It also may be a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

In the earliest stages, when only small inflammatory papules are present, patients should be instructed not to cut their hair shorter than 0.25-in long to avoid hair retention. Also, topical clindamycin lotion or topical chlorhexidine solution may serve as sufficient treatment. As the disease progresses, oral doxycycline 100 mg bid, combination rifampin 300 mg bid and clindamycin 300 mg bid for 3 months, or isotretinoin 1 mg/kg daily for 6 to 8 months are medical therapeutic options. Procedural options include radiation and laser hair removal.

In this patient, trials of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL helped to flatten the plaque, but hair loss persisted. Ultimately, he was referred to Plastic Surgery for excision and was treated for several months with doxycycline 100 mg bid and monitored for recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae.

Follicular keloidalis, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. It also may be a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

In the earliest stages, when only small inflammatory papules are present, patients should be instructed not to cut their hair shorter than 0.25-in long to avoid hair retention. Also, topical clindamycin lotion or topical chlorhexidine solution may serve as sufficient treatment. As the disease progresses, oral doxycycline 100 mg bid, combination rifampin 300 mg bid and clindamycin 300 mg bid for 3 months, or isotretinoin 1 mg/kg daily for 6 to 8 months are medical therapeutic options. Procedural options include radiation and laser hair removal.

In this patient, trials of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL helped to flatten the plaque, but hair loss persisted. Ultimately, he was referred to Plastic Surgery for excision and was treated for several months with doxycycline 100 mg bid and monitored for recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017. pii: bcr-2017-222222. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222222.

Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017. pii: bcr-2017-222222. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222222.

Nail growth

The treatment failure with the terbinafine made onychomycosis unlikely, and the appearance of the finger did not suggest that this was a wart. So, the physician opted for a 4-mm punch biopsy of the lateral nail fold, which confirmed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the fingertip.

Periungual SCC is twice as common in men as women. Lesions tend to appear as hyperkeratotic plaques or nodules, pushing the nail plate away from the nail bed. With onychomycosis, one would expect the nail to be more thickened and discolored. A wart would not be as keratotic as this lesion was, and there would be thrombosed capillaries on closer inspection.

SCC is the second most common skin cancer in humans. It is most common on sun-exposed areas but may present in sites not exposed to the sun. It has been hypothesized that high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types—particularly HPV 16—may contribute to diseases of the fingertips and nail unit in older adults. (There was no known history of HPV in this patient.)

A surgical approach often is curative. Achieving appropriate margins occasionally requires partial amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offers the highest cure rate and spares as much uninvolved tissue as possible. Radiation therapy is another tissue-sparing technique. It requires 15 to 30 sessions over 3 to 6 weeks and has a lower cure rate than MMS.

In this case, the patient underwent MMS. Follow-up skin surveillance exams revealed other small nonmelanoma skin cancers at other sites. The patient also developed a dystrophic nail spicule near the surgical site that was re-excised and deemed benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Riddel C, Rashid R, Thomas V. Ungual and periungual human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64:1147-1153.

The treatment failure with the terbinafine made onychomycosis unlikely, and the appearance of the finger did not suggest that this was a wart. So, the physician opted for a 4-mm punch biopsy of the lateral nail fold, which confirmed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the fingertip.

Periungual SCC is twice as common in men as women. Lesions tend to appear as hyperkeratotic plaques or nodules, pushing the nail plate away from the nail bed. With onychomycosis, one would expect the nail to be more thickened and discolored. A wart would not be as keratotic as this lesion was, and there would be thrombosed capillaries on closer inspection.

SCC is the second most common skin cancer in humans. It is most common on sun-exposed areas but may present in sites not exposed to the sun. It has been hypothesized that high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types—particularly HPV 16—may contribute to diseases of the fingertips and nail unit in older adults. (There was no known history of HPV in this patient.)

A surgical approach often is curative. Achieving appropriate margins occasionally requires partial amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offers the highest cure rate and spares as much uninvolved tissue as possible. Radiation therapy is another tissue-sparing technique. It requires 15 to 30 sessions over 3 to 6 weeks and has a lower cure rate than MMS.

In this case, the patient underwent MMS. Follow-up skin surveillance exams revealed other small nonmelanoma skin cancers at other sites. The patient also developed a dystrophic nail spicule near the surgical site that was re-excised and deemed benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The treatment failure with the terbinafine made onychomycosis unlikely, and the appearance of the finger did not suggest that this was a wart. So, the physician opted for a 4-mm punch biopsy of the lateral nail fold, which confirmed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the fingertip.

Periungual SCC is twice as common in men as women. Lesions tend to appear as hyperkeratotic plaques or nodules, pushing the nail plate away from the nail bed. With onychomycosis, one would expect the nail to be more thickened and discolored. A wart would not be as keratotic as this lesion was, and there would be thrombosed capillaries on closer inspection.

SCC is the second most common skin cancer in humans. It is most common on sun-exposed areas but may present in sites not exposed to the sun. It has been hypothesized that high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types—particularly HPV 16—may contribute to diseases of the fingertips and nail unit in older adults. (There was no known history of HPV in this patient.)

A surgical approach often is curative. Achieving appropriate margins occasionally requires partial amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) offers the highest cure rate and spares as much uninvolved tissue as possible. Radiation therapy is another tissue-sparing technique. It requires 15 to 30 sessions over 3 to 6 weeks and has a lower cure rate than MMS.

In this case, the patient underwent MMS. Follow-up skin surveillance exams revealed other small nonmelanoma skin cancers at other sites. The patient also developed a dystrophic nail spicule near the surgical site that was re-excised and deemed benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Riddel C, Rashid R, Thomas V. Ungual and periungual human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64:1147-1153.

Riddel C, Rashid R, Thomas V. Ungual and periungual human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64:1147-1153.

Chronic anterior knee pain

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

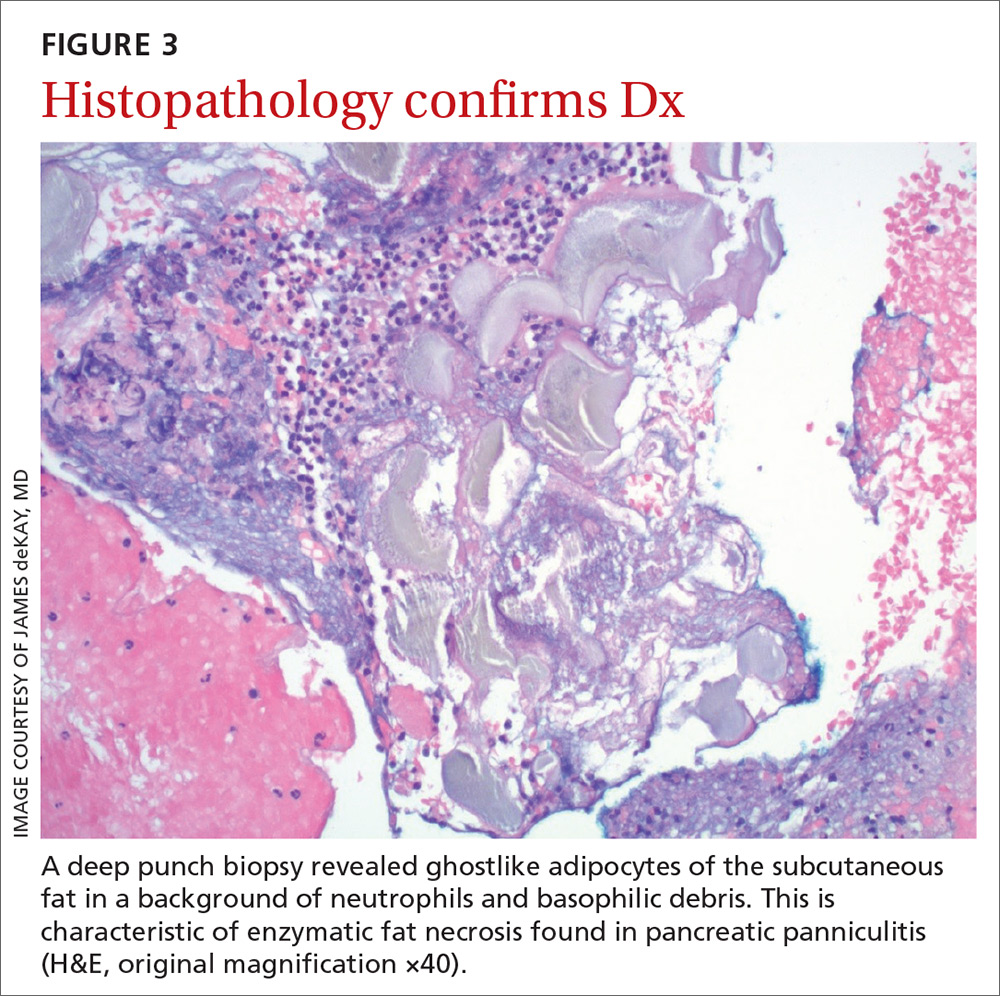

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; [email protected].

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; [email protected].

A 14-year-old girl with an unremarkable medical history presented to the family medicine clinic with a 6-month history of right knee pain (episodic locking and anterior pain). Physical examination of the knee ligaments revealed that the knee was stable and pain-free in the frontal and sagittal planes. There was no intra-articular effusion, the joint spaces were not painful, and range of motion was normal.

Palpation of the knee elicited pain, notably when the physician rolled his fingers over a “cord” above the internal parapatellar compartment. X-rays of the knee were normal. In light of the patient’s chronic pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Synovial plica

The MRI with fat saturation revealed a symptomatic synovial plica between the patellar facet and the condyle (FIGURE 1, arrow). The normal x-ray findings had already ruled out osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles, patellar abnormalities, and trochlear dysplasia; the MRI ruled out several additional items in the differential, such as damage to the meniscus, ligament, and/or cartilage.

The synovial plica is a normal structure that develops during the embryogenic phase; however, involution is incomplete in up to 50% of the population, resulting in persistent plicae.1 The plica is often located in a medial position but can occur lateral to, above, or below the knee cap. Although usually asymptomatic, the plica can become pathologic when irritation (eg, from repetitive motion) causes an inflammatory response.1

Synovial plica syndrome, as this condition is known, is a common cause of anterior knee pain in adolescents and athletes; incidence ranges from 3.8% to 5.5%.2 The patient often reports trauma (a direct impact to the knee) or participation in sports activities that require repeated flexion-extension of the knee.3

Presenting symptoms and MRI findings can unlock the diagnosis

The combination of anterior knee pain and a painful parapatellar “cord” on palpation is the most frequent diagnostic sign of synovial plica syndrome.1 Quadriceps wasting, intra-articular effusion, and reduced range of motion of the knee may also be observed.1,4 Some patients experience particularly disconcerting symptoms, such as knee locking, clicking, or instability.1

In most cases, MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis while ruling out other possible causes of the symptoms and associated pathologies.5 However, MRI may not reveal the plica if it is attached to the articular capsule or if there is no intra-articular effusion. Dynamic ultrasound might be of diagnostic value but is operator dependent.4

Continue to: If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

If conservative treatment fails, consider surgical repair

Conservative treatment—a combination of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and physiotherapy with vastus medialis strengthening and stretching—is the preferred first-line treatment, with a success rate of 40% to 60%.1 If conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be

Our patient underwent arthroscopic resection of the plica after 6 months of conservative treatment had failed (FIGURE 2). The patient was able to walk immediately after surgery. The outcome was favorable, since physiotherapy was no longer required 2 months after surgery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Céline Klein, MD, Service d’Orthopédie Pédiatrique, CHU Amiens, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, F-80054 Amiens cedex 1, France; [email protected].

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

1. Camanho GL. Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paolo). 2010;65:247-250.

2. Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

3. Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:190-198.

4. Paczesny Ł, Kruczyński J. Medial plica syndrome of the knee: diagnosis with dynamic sonography. Radiology. 2009;251:439-446.

5. Samim M, Smitaman E, Lawrence D, et al. MRI of anterior knee pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:875-893.

6. Weckström M, Niva MH, Lamminen A, et al. Arthroscopic resection of medial plica of the knee in young adults. Knee. 2010;17:103-107.

7. Kan H, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Characteristics of medial plica syndrome complicated with cartilage damage. Int Orthop. 2015;39:2489-2494.

Fever, abdominal pain, and adnexal mass

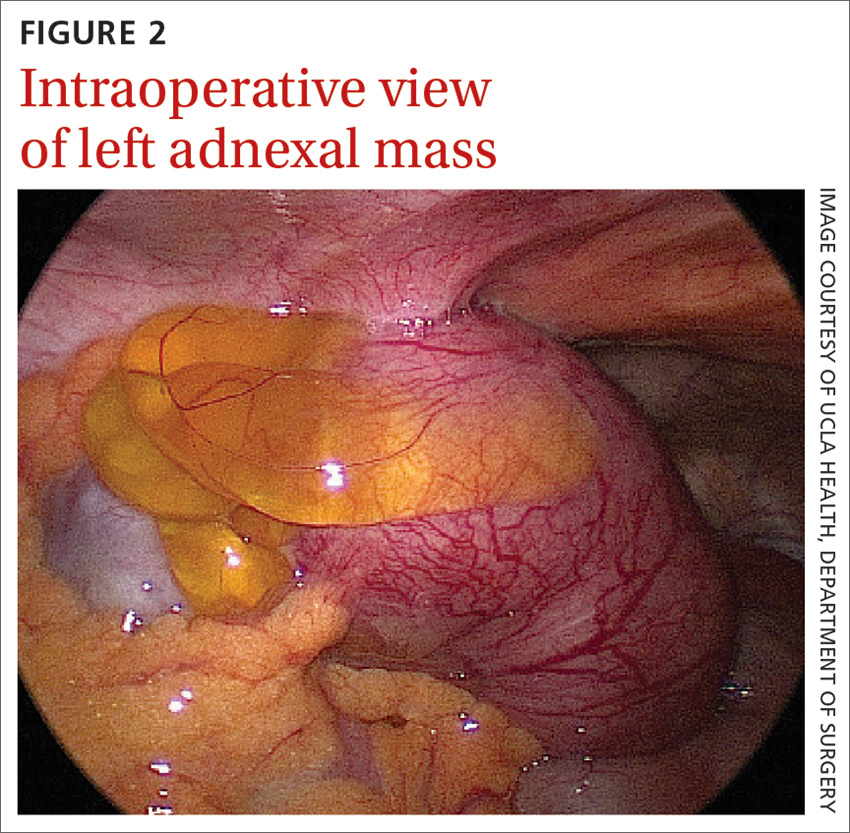

At the recommendation of her primary care physician, a 53-year-old perimenopausal woman sought care at the emergency department for the fever, abdominal pain, and pyuria that had persisted for 4 days despite outpatient treatment for pyelonephritis. On physical examination, she was febrile and tachycardic with abdominal tenderness of the left lower quadrant. Genitourinary examination revealed copious brown vaginal discharge, left adnexal tenderness, and no cervical motion tenderness.

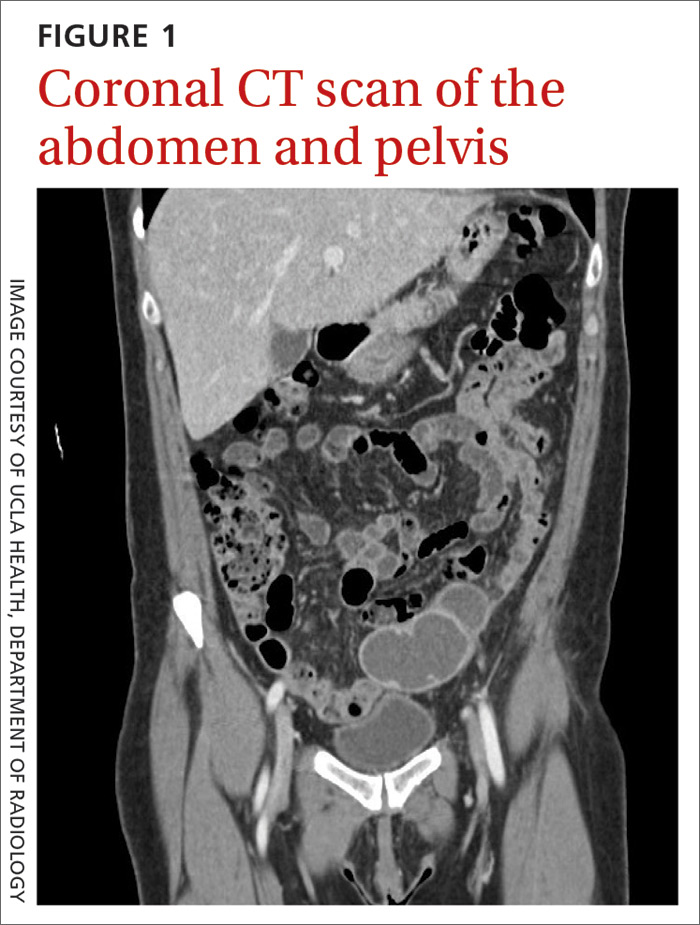

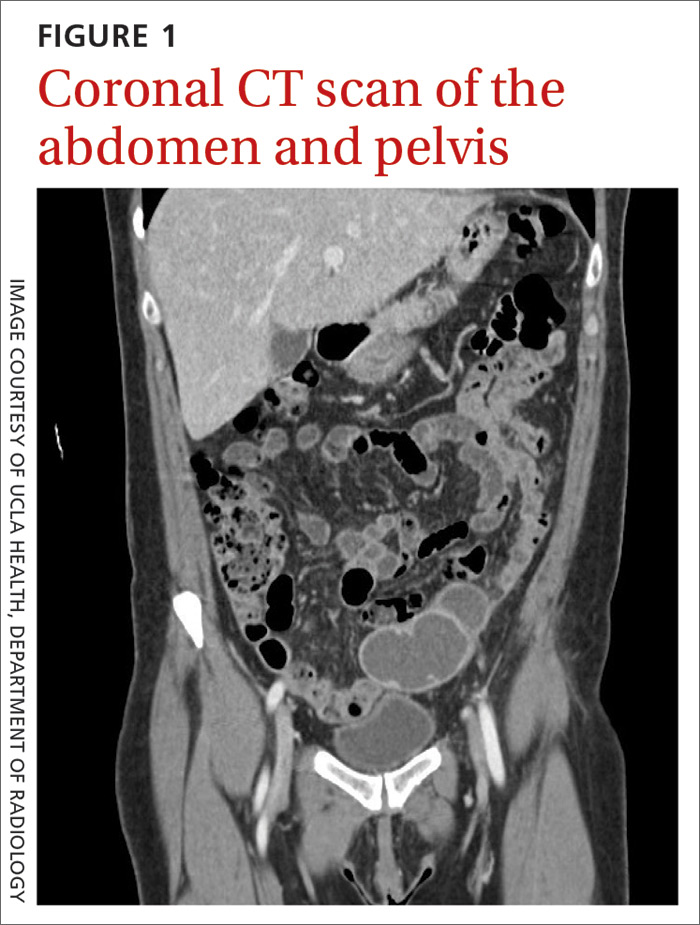

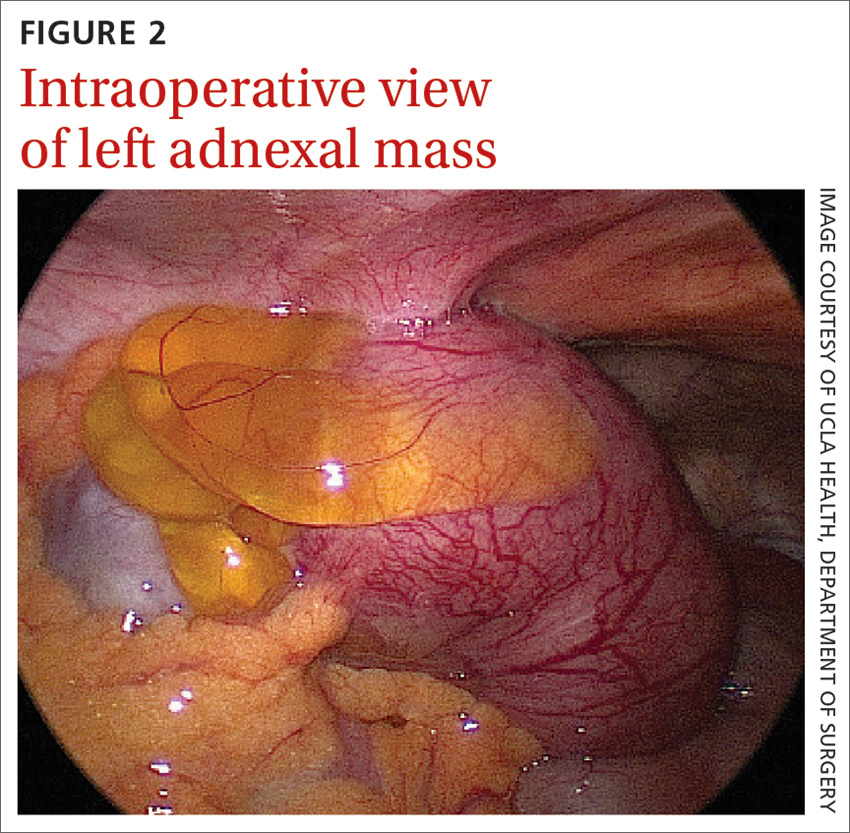

Laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis but otherwise normal electrolytes, liver function tests, and lactate levels. Urine culture obtained when she presented to an urgent care facility 3 days earlier had been negative. Computed tomography (CT) was performed and was read by Radiology as “closed loop small bowel obstruction in the left lower abdomen” (FIGURE 1). The patient was taken emergently to the operating room where her entire length of bowel was run without any obstruction found. Instead, the surgeons identified a mass in the left iliac fossa originating from the left ovary and fallopian tube (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess

The presence and location of this mass, paired with the patient’s symptoms, led to the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. PID is an acute infection of the upper genital tract in women thought to be due to ascending infection from the lower genital tract. The prevalence of PID in reproductive-aged women in the United States is estimated to be 4.4%.1

Diagnosis of PID in middle-aged women is a challenge given the broad differential diagnosis of nonspecific presenting symptoms, lower index of suspicion in this age group, and unknown exact incidence of PID in postmenopausal women. While delay in diagnosis of PID in women of reproductive age is associated with increased infertility and ectopic pregnancy,2 delay in diagnosis in postmenopausal women also poses serious potential complications such as tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA)—as was seen with this patient—and concurrent gynecologic malignancy found on pathology of TOA specimens.3,4

Risk factors for PID in the postmenopausal population include recent uterine instrumentation, history of prior PID, and structural abnormalities such as cervical stenosis, uterine anatomic abnormalities, or tubal disease. The microbiology of PID in postmenopausal women differs from that of women of reproductive age. While sexually transmitted pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis most commonly are implicated in PID among premenopausal patients, aerobic gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae most frequently are associated in postmenopausal cases.

Differential diagnosis for abdominal pain is broad

The differential diagnosis for a patient with fever and abdominal pain includes PID, as well as the following:

Diverticulitis classically presents with left lower abdominal pain and a low-grade fever. Complications may include bowel obstruction, abscess, fistula, or perforation. Abdominal imaging such as a CT scan is required to establish the diagnosis.

Continue to: Urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infection should be suspected in a patient with dysuria, urinary frequency or urgency, and abdominal or flank pain. Urinalysis and culture should be performed and imaging may be considered for suspected obstruction, complication, or failure to improve on appropriate therapy.

Appendicitis may present as right lower quadrant pain with anorexia, fever, and nausea. Imaging studies such as CT or ultrasound can help support the diagnosis and rule out alternate etiologies of the presenting symptoms.

Ectopic pregnancy—while not considered in this case—should be suspected in a patient presenting with pelvic pain, missed menses or vaginal bleeding, and a positive pregnancy test. Further evaluation may be performed with a transvaginal ultrasound and serial measurement of serum quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin level.

Diagnosing PID is a clinical process

PID often is difficult to diagnose because of an absence of symptoms or the presence of symptoms that are subtle or nonspecific. Laparoscopy or endometrial biopsy can be useful but may not be justifiable due to their invasive nature when symptoms are mild or vague.5 Thus, a diagnosis of PID usually is based on clinical findings.

Clinical criteria to look for. Although PID commonly is attributed to N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis, fewer than 50% of those with a diagnosis of acute PID test positive for either of these organisms.5 As such, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines recommend presumptive treatment for PID in women with pelvic or lower abdominal pain with 1 or more of the following clinical criteria: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.

Continue to: The following criteria...

The following criteria enhance specificity and support the diagnosis5:

- oral temperature > 101°F (> 38.3°C),

- abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability,

- presence of “abundant numbers of white blood cells on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid,”

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (reference range, 0–20 mm/hr),

- elevated C-reactive protein (reference range, 0.08-3.1 mg/L), and

- laboratory documentation of cervical infection with N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.

The CDC also suggests that the most specific criteria for PID include5

- endometrial biopsy consistent with endometritis,

- imaging (transvaginal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) demonstrating fluid-filled tubes, or

- laparoscopic findings consistent with PID.

Treatment of PID includes IV antibiotics

Due to the polymicrobial nature of PID, antibiotics should cover not only gonorrhea and chlamydia but also anaerobic pathogens. CDC guidelines recommend the following treatment5,6:

- intravenous (IV) cefotetan (2 g bid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid),

- IV cefoxitin (2 g qid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid), or

- IV clindamycin (900 mg tid) plus IV or intramuscular (IM) gentamicin loading dose (2 mg/kg) followed by a maintenance dose (1.5 mg/kg tid).

In mild-to-moderate PID cases deemed appropriate for outpatient therapy, the following regimens have been shown to have similar outcomes to IV therapy5,6:

- IM ceftriaxone (250 mg, single dose) plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days,

- IM cefoxitin (2 g, single dose) and PO probenecid (1 g, single dose) plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days, or

- other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days.

Management in older women may be more intensive

Due to the increased risk of malignancy in postmenopausal women with TOA, surgical intervention may be needed.3,4

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, hysterectomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy, and right salpingectomy (with her right ovary left in place due to her perimenopausal status). Intraoperatively, she was found to have cervical stenosis. Postoperatively, she improved on IV cefoxitin (2 g qid) and IV doxycycline (100 mg bid), which was eventually transitioned to oral doxycycline (100 mg bid) and metronidazole (500 mg bid) on discharge.

Her final microbiology was negative for gonorrhea/chlamydia but the bacterial culture of peritoneal fluid grew E coli. Pathology was consistent with acute salpingitis, TOA, and acute cervicitis. She made a full recovery and is doing well.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Peony Khoo, MD, 1920 Colorado Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90404; [email protected]

1. Kreisel K, Torrone E, Bernstein K, et al. Prevalence of pelvic inflammatory disease in sexually experienced women of reproductive age—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:80-83.

2. Weström L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility: a cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:185-192.

3. Jackson SL, Soper DE. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the postmenopausal woman. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1999;7:248-252.

4. Protopas AG, Diakomanolis ES, Milingos SD, et al. Tubo-ovarian abscesses in postmenopausal women: gynecological malignancy until proven otherwise? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114:203-209.

5. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

6. Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:929-937 .

At the recommendation of her primary care physician, a 53-year-old perimenopausal woman sought care at the emergency department for the fever, abdominal pain, and pyuria that had persisted for 4 days despite outpatient treatment for pyelonephritis. On physical examination, she was febrile and tachycardic with abdominal tenderness of the left lower quadrant. Genitourinary examination revealed copious brown vaginal discharge, left adnexal tenderness, and no cervical motion tenderness.

Laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis but otherwise normal electrolytes, liver function tests, and lactate levels. Urine culture obtained when she presented to an urgent care facility 3 days earlier had been negative. Computed tomography (CT) was performed and was read by Radiology as “closed loop small bowel obstruction in the left lower abdomen” (FIGURE 1). The patient was taken emergently to the operating room where her entire length of bowel was run without any obstruction found. Instead, the surgeons identified a mass in the left iliac fossa originating from the left ovary and fallopian tube (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess

The presence and location of this mass, paired with the patient’s symptoms, led to the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. PID is an acute infection of the upper genital tract in women thought to be due to ascending infection from the lower genital tract. The prevalence of PID in reproductive-aged women in the United States is estimated to be 4.4%.1

Diagnosis of PID in middle-aged women is a challenge given the broad differential diagnosis of nonspecific presenting symptoms, lower index of suspicion in this age group, and unknown exact incidence of PID in postmenopausal women. While delay in diagnosis of PID in women of reproductive age is associated with increased infertility and ectopic pregnancy,2 delay in diagnosis in postmenopausal women also poses serious potential complications such as tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA)—as was seen with this patient—and concurrent gynecologic malignancy found on pathology of TOA specimens.3,4

Risk factors for PID in the postmenopausal population include recent uterine instrumentation, history of prior PID, and structural abnormalities such as cervical stenosis, uterine anatomic abnormalities, or tubal disease. The microbiology of PID in postmenopausal women differs from that of women of reproductive age. While sexually transmitted pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis most commonly are implicated in PID among premenopausal patients, aerobic gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae most frequently are associated in postmenopausal cases.

Differential diagnosis for abdominal pain is broad

The differential diagnosis for a patient with fever and abdominal pain includes PID, as well as the following:

Diverticulitis classically presents with left lower abdominal pain and a low-grade fever. Complications may include bowel obstruction, abscess, fistula, or perforation. Abdominal imaging such as a CT scan is required to establish the diagnosis.

Continue to: Urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infection should be suspected in a patient with dysuria, urinary frequency or urgency, and abdominal or flank pain. Urinalysis and culture should be performed and imaging may be considered for suspected obstruction, complication, or failure to improve on appropriate therapy.

Appendicitis may present as right lower quadrant pain with anorexia, fever, and nausea. Imaging studies such as CT or ultrasound can help support the diagnosis and rule out alternate etiologies of the presenting symptoms.

Ectopic pregnancy—while not considered in this case—should be suspected in a patient presenting with pelvic pain, missed menses or vaginal bleeding, and a positive pregnancy test. Further evaluation may be performed with a transvaginal ultrasound and serial measurement of serum quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin level.

Diagnosing PID is a clinical process

PID often is difficult to diagnose because of an absence of symptoms or the presence of symptoms that are subtle or nonspecific. Laparoscopy or endometrial biopsy can be useful but may not be justifiable due to their invasive nature when symptoms are mild or vague.5 Thus, a diagnosis of PID usually is based on clinical findings.

Clinical criteria to look for. Although PID commonly is attributed to N gonorrhoeae and C trachomatis, fewer than 50% of those with a diagnosis of acute PID test positive for either of these organisms.5 As such, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines recommend presumptive treatment for PID in women with pelvic or lower abdominal pain with 1 or more of the following clinical criteria: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.

Continue to: The following criteria...

The following criteria enhance specificity and support the diagnosis5:

- oral temperature > 101°F (> 38.3°C),

- abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability,

- presence of “abundant numbers of white blood cells on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid,”

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (reference range, 0–20 mm/hr),

- elevated C-reactive protein (reference range, 0.08-3.1 mg/L), and

- laboratory documentation of cervical infection with N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.

The CDC also suggests that the most specific criteria for PID include5

- endometrial biopsy consistent with endometritis,

- imaging (transvaginal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging) demonstrating fluid-filled tubes, or

- laparoscopic findings consistent with PID.

Treatment of PID includes IV antibiotics

Due to the polymicrobial nature of PID, antibiotics should cover not only gonorrhea and chlamydia but also anaerobic pathogens. CDC guidelines recommend the following treatment5,6:

- intravenous (IV) cefotetan (2 g bid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid),

- IV cefoxitin (2 g qid) plus doxycycline (100 mg PO or IV bid), or

- IV clindamycin (900 mg tid) plus IV or intramuscular (IM) gentamicin loading dose (2 mg/kg) followed by a maintenance dose (1.5 mg/kg tid).

In mild-to-moderate PID cases deemed appropriate for outpatient therapy, the following regimens have been shown to have similar outcomes to IV therapy5,6:

- IM ceftriaxone (250 mg, single dose) plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days,

- IM cefoxitin (2 g, single dose) and PO probenecid (1 g, single dose) plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days, or

- other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin plus PO doxycycline (100 mg bid) for 14 days with/without PO metronidazole (500 mg bid) for 14 days.

Management in older women may be more intensive

Due to the increased risk of malignancy in postmenopausal women with TOA, surgical intervention may be needed.3,4

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, hysterectomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy, and right salpingectomy (with her right ovary left in place due to her perimenopausal status). Intraoperatively, she was found to have cervical stenosis. Postoperatively, she improved on IV cefoxitin (2 g qid) and IV doxycycline (100 mg bid), which was eventually transitioned to oral doxycycline (100 mg bid) and metronidazole (500 mg bid) on discharge.

Her final microbiology was negative for gonorrhea/chlamydia but the bacterial culture of peritoneal fluid grew E coli. Pathology was consistent with acute salpingitis, TOA, and acute cervicitis. She made a full recovery and is doing well.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Peony Khoo, MD, 1920 Colorado Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90404; [email protected]

At the recommendation of her primary care physician, a 53-year-old perimenopausal woman sought care at the emergency department for the fever, abdominal pain, and pyuria that had persisted for 4 days despite outpatient treatment for pyelonephritis. On physical examination, she was febrile and tachycardic with abdominal tenderness of the left lower quadrant. Genitourinary examination revealed copious brown vaginal discharge, left adnexal tenderness, and no cervical motion tenderness.

Laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis but otherwise normal electrolytes, liver function tests, and lactate levels. Urine culture obtained when she presented to an urgent care facility 3 days earlier had been negative. Computed tomography (CT) was performed and was read by Radiology as “closed loop small bowel obstruction in the left lower abdomen” (FIGURE 1). The patient was taken emergently to the operating room where her entire length of bowel was run without any obstruction found. Instead, the surgeons identified a mass in the left iliac fossa originating from the left ovary and fallopian tube (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess

The presence and location of this mass, paired with the patient’s symptoms, led to the diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. PID is an acute infection of the upper genital tract in women thought to be due to ascending infection from the lower genital tract. The prevalence of PID in reproductive-aged women in the United States is estimated to be 4.4%.1