User login

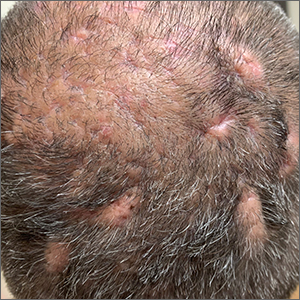

Scalp ridges

The gyrate or cerebriform pattern of inflammatory, often pus-filled, subcutaneous tracts of the scalp pointed to a diagnosis of dissecting cellulitis. This patient did not have the fluctuant tracts frequently seen in more active disease but did have the scarring and alopecia common with this disorder.

Dissecting cellulitis is similar to acne and hidradenitis suppurativa in that it starts with follicular plugging. This plugging leads to inflammation, dilation and rupture of the follicle, and purulent sinus tract formation. The sinus tracts of the scalp can be extensive. Dissecting cellulitis is most common in 18- to 40-year-olds and more common in Black individuals.1 When it occurs in conjunction with cystic acne and hidradenitis suppurativa, it is known as the follicular occlusion triad syndrome.

While oral antibiotics are an option for the treatment of dissecting cellulitis, oral isotretinoin is the first-line approach. Tumor necrosis factor alfa inhibitors have also been used with success, according to case reports.1

Given that this patient had a small area of current inflammation, he was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 months. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months to reassess his progress and to explore treatment with isotretinoin if the condition worsened or did not improve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Federico A, Rossi A, Caro G, et al. Are dissecting cellulitis and hidradenitis suppurativa different diseases? Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:496-499. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.01.002

The gyrate or cerebriform pattern of inflammatory, often pus-filled, subcutaneous tracts of the scalp pointed to a diagnosis of dissecting cellulitis. This patient did not have the fluctuant tracts frequently seen in more active disease but did have the scarring and alopecia common with this disorder.

Dissecting cellulitis is similar to acne and hidradenitis suppurativa in that it starts with follicular plugging. This plugging leads to inflammation, dilation and rupture of the follicle, and purulent sinus tract formation. The sinus tracts of the scalp can be extensive. Dissecting cellulitis is most common in 18- to 40-year-olds and more common in Black individuals.1 When it occurs in conjunction with cystic acne and hidradenitis suppurativa, it is known as the follicular occlusion triad syndrome.

While oral antibiotics are an option for the treatment of dissecting cellulitis, oral isotretinoin is the first-line approach. Tumor necrosis factor alfa inhibitors have also been used with success, according to case reports.1

Given that this patient had a small area of current inflammation, he was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 months. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months to reassess his progress and to explore treatment with isotretinoin if the condition worsened or did not improve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The gyrate or cerebriform pattern of inflammatory, often pus-filled, subcutaneous tracts of the scalp pointed to a diagnosis of dissecting cellulitis. This patient did not have the fluctuant tracts frequently seen in more active disease but did have the scarring and alopecia common with this disorder.

Dissecting cellulitis is similar to acne and hidradenitis suppurativa in that it starts with follicular plugging. This plugging leads to inflammation, dilation and rupture of the follicle, and purulent sinus tract formation. The sinus tracts of the scalp can be extensive. Dissecting cellulitis is most common in 18- to 40-year-olds and more common in Black individuals.1 When it occurs in conjunction with cystic acne and hidradenitis suppurativa, it is known as the follicular occlusion triad syndrome.

While oral antibiotics are an option for the treatment of dissecting cellulitis, oral isotretinoin is the first-line approach. Tumor necrosis factor alfa inhibitors have also been used with success, according to case reports.1

Given that this patient had a small area of current inflammation, he was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 months. He was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in 3 months to reassess his progress and to explore treatment with isotretinoin if the condition worsened or did not improve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Federico A, Rossi A, Caro G, et al. Are dissecting cellulitis and hidradenitis suppurativa different diseases? Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:496-499. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.01.002

1. Federico A, Rossi A, Caro G, et al. Are dissecting cellulitis and hidradenitis suppurativa different diseases? Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:496-499. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.01.002

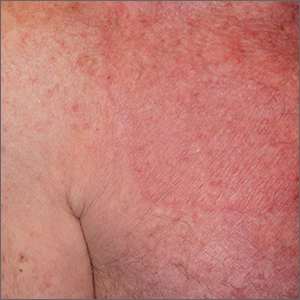

Palmar rash

This patient’s targetoid and tingling skin lesions, in association with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, are a classic presentation of erythema multiforme (EM).

EM is an acute, self-limited, immune-mediated process that most commonly arises in a symmetrical pattern on acral surfaces. These lesions may be accompanied by eruptions on oral, anogenital, or ocular mucosa. EM is classified into 2 subtypes: major and minor. EM major refers to EM with significant mucosal involvement on at least 2 mucosal sites; it may also manifest with a prodrome of fevers, arthralgias, and malaise. EM minor is used to classify EM with minimal mucosal involvement.1

The term “multiforme” denotes the varied dermatologic changes, including macules, papules, and targetoid lesions with 3 identifiable zones, which are pathognomonic for EM. The classic 3 zones consist of an inner dusky, vesicular, or necrotic center; a middle elevated edematous surrounding ring; and an outer ring of macular erythema. Patients may also present with an atypical macular target lesion, characterized by fewer than 3 zones with an ill-defined border between the zones. The lesions may be asymptomatic, or patients may describe an itchy or burning sensation.

The differential diagnosis of EM includes urticaria, fixed drug eruption, subacute lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease, erythema annulare centrifugum, vasculitis, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Infections with HSV types 1 or 2 are the leading cause of EM and are thought to involve a cell-mediated immune process directed against viral antigens in skin.2 Other infectious causes include cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza virus, and—rarely—newer strains of coronavirus.3 Pharmacologic reactions are the cause in a small percentage of patients, and may involve nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Studies also link the development of EM to primary malignancy, autoimmune disease, and immunizations.1

The treatment of EM is dependent on the clinical course and severity of the disease. If a causative agent is identified, it should be discontinued (if a drug) or treated (if an infection). Topical antiseptic mouthwashes, antihistamines, and topical corticosteroids can be used to relieve cutaneous discomfort. Biologics and immunosuppressants can be used with patients who have severe symptoms or functional impairment. Patients who have recurrences associated with HSV should be given antiviral prophylaxis for 6 months consisting of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg/d, valacyclovir 500 to 1000 mg/d, or famciclovir 250 mg twice daily.1

Given the recurrent nature of this patient’s disease, and its association with HSV outbreaks, he was prescribed prophylactic valacyclovir 1000 mg/d orally for 6 months to reduce HSV outbreaks and hopefully prevent future EM episodes.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Lynn Midani, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

2. Hafsi W, Badri T. Erythema multiforme. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed December 15, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470259/

3. Bennardo L, Nisticò SP, Dastoli S, et al. Erythema multiforme and COVID-19: what do we know? Medicina. 2021;57:828. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080828

This patient’s targetoid and tingling skin lesions, in association with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, are a classic presentation of erythema multiforme (EM).

EM is an acute, self-limited, immune-mediated process that most commonly arises in a symmetrical pattern on acral surfaces. These lesions may be accompanied by eruptions on oral, anogenital, or ocular mucosa. EM is classified into 2 subtypes: major and minor. EM major refers to EM with significant mucosal involvement on at least 2 mucosal sites; it may also manifest with a prodrome of fevers, arthralgias, and malaise. EM minor is used to classify EM with minimal mucosal involvement.1

The term “multiforme” denotes the varied dermatologic changes, including macules, papules, and targetoid lesions with 3 identifiable zones, which are pathognomonic for EM. The classic 3 zones consist of an inner dusky, vesicular, or necrotic center; a middle elevated edematous surrounding ring; and an outer ring of macular erythema. Patients may also present with an atypical macular target lesion, characterized by fewer than 3 zones with an ill-defined border between the zones. The lesions may be asymptomatic, or patients may describe an itchy or burning sensation.

The differential diagnosis of EM includes urticaria, fixed drug eruption, subacute lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease, erythema annulare centrifugum, vasculitis, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Infections with HSV types 1 or 2 are the leading cause of EM and are thought to involve a cell-mediated immune process directed against viral antigens in skin.2 Other infectious causes include cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza virus, and—rarely—newer strains of coronavirus.3 Pharmacologic reactions are the cause in a small percentage of patients, and may involve nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Studies also link the development of EM to primary malignancy, autoimmune disease, and immunizations.1

The treatment of EM is dependent on the clinical course and severity of the disease. If a causative agent is identified, it should be discontinued (if a drug) or treated (if an infection). Topical antiseptic mouthwashes, antihistamines, and topical corticosteroids can be used to relieve cutaneous discomfort. Biologics and immunosuppressants can be used with patients who have severe symptoms or functional impairment. Patients who have recurrences associated with HSV should be given antiviral prophylaxis for 6 months consisting of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg/d, valacyclovir 500 to 1000 mg/d, or famciclovir 250 mg twice daily.1

Given the recurrent nature of this patient’s disease, and its association with HSV outbreaks, he was prescribed prophylactic valacyclovir 1000 mg/d orally for 6 months to reduce HSV outbreaks and hopefully prevent future EM episodes.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Lynn Midani, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This patient’s targetoid and tingling skin lesions, in association with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, are a classic presentation of erythema multiforme (EM).

EM is an acute, self-limited, immune-mediated process that most commonly arises in a symmetrical pattern on acral surfaces. These lesions may be accompanied by eruptions on oral, anogenital, or ocular mucosa. EM is classified into 2 subtypes: major and minor. EM major refers to EM with significant mucosal involvement on at least 2 mucosal sites; it may also manifest with a prodrome of fevers, arthralgias, and malaise. EM minor is used to classify EM with minimal mucosal involvement.1

The term “multiforme” denotes the varied dermatologic changes, including macules, papules, and targetoid lesions with 3 identifiable zones, which are pathognomonic for EM. The classic 3 zones consist of an inner dusky, vesicular, or necrotic center; a middle elevated edematous surrounding ring; and an outer ring of macular erythema. Patients may also present with an atypical macular target lesion, characterized by fewer than 3 zones with an ill-defined border between the zones. The lesions may be asymptomatic, or patients may describe an itchy or burning sensation.

The differential diagnosis of EM includes urticaria, fixed drug eruption, subacute lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease, erythema annulare centrifugum, vasculitis, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Infections with HSV types 1 or 2 are the leading cause of EM and are thought to involve a cell-mediated immune process directed against viral antigens in skin.2 Other infectious causes include cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza virus, and—rarely—newer strains of coronavirus.3 Pharmacologic reactions are the cause in a small percentage of patients, and may involve nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Studies also link the development of EM to primary malignancy, autoimmune disease, and immunizations.1

The treatment of EM is dependent on the clinical course and severity of the disease. If a causative agent is identified, it should be discontinued (if a drug) or treated (if an infection). Topical antiseptic mouthwashes, antihistamines, and topical corticosteroids can be used to relieve cutaneous discomfort. Biologics and immunosuppressants can be used with patients who have severe symptoms or functional impairment. Patients who have recurrences associated with HSV should be given antiviral prophylaxis for 6 months consisting of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg/d, valacyclovir 500 to 1000 mg/d, or famciclovir 250 mg twice daily.1

Given the recurrent nature of this patient’s disease, and its association with HSV outbreaks, he was prescribed prophylactic valacyclovir 1000 mg/d orally for 6 months to reduce HSV outbreaks and hopefully prevent future EM episodes.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle F. Finan, MD. Text courtesy of Lynn Midani, BS, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Cyrelle F. Finan, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

2. Hafsi W, Badri T. Erythema multiforme. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed December 15, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470259/

3. Bennardo L, Nisticò SP, Dastoli S, et al. Erythema multiforme and COVID-19: what do we know? Medicina. 2021;57:828. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080828

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

2. Hafsi W, Badri T. Erythema multiforme. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed December 15, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470259/

3. Bennardo L, Nisticò SP, Dastoli S, et al. Erythema multiforme and COVID-19: what do we know? Medicina. 2021;57:828. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080828

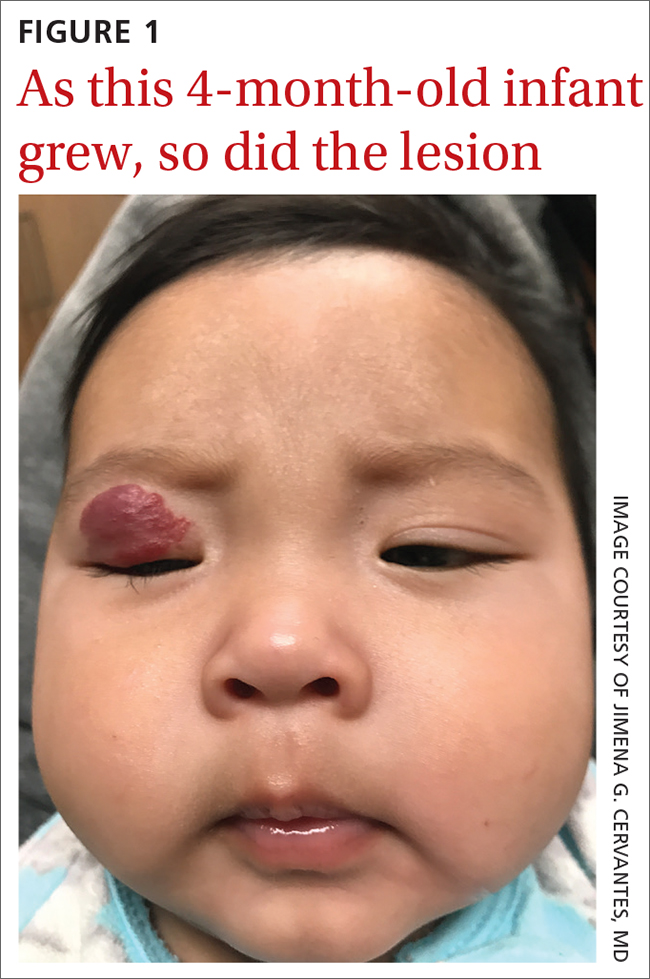

Infant with red eyelid lesion

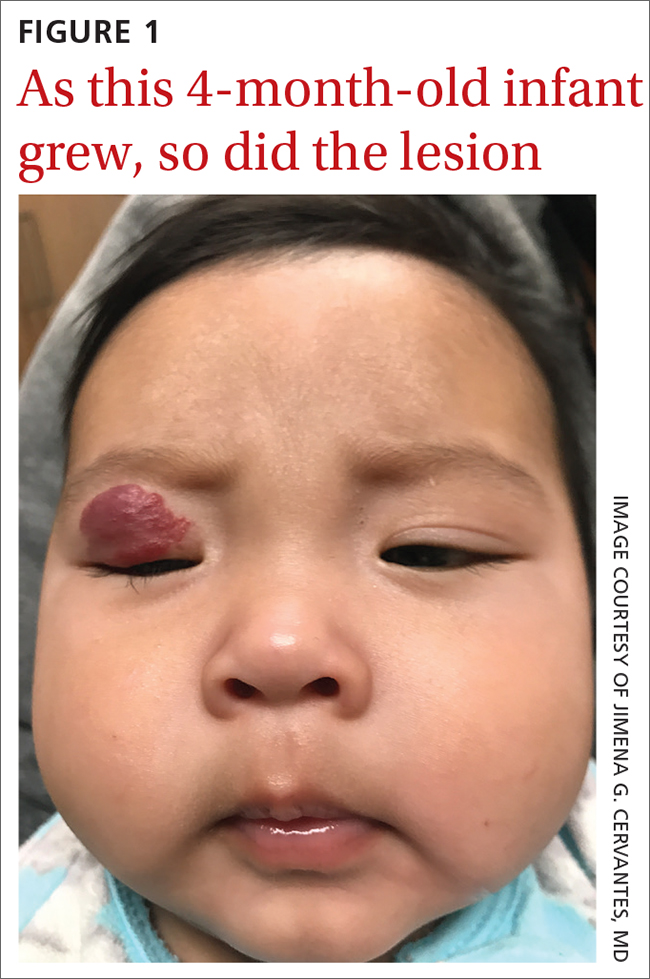

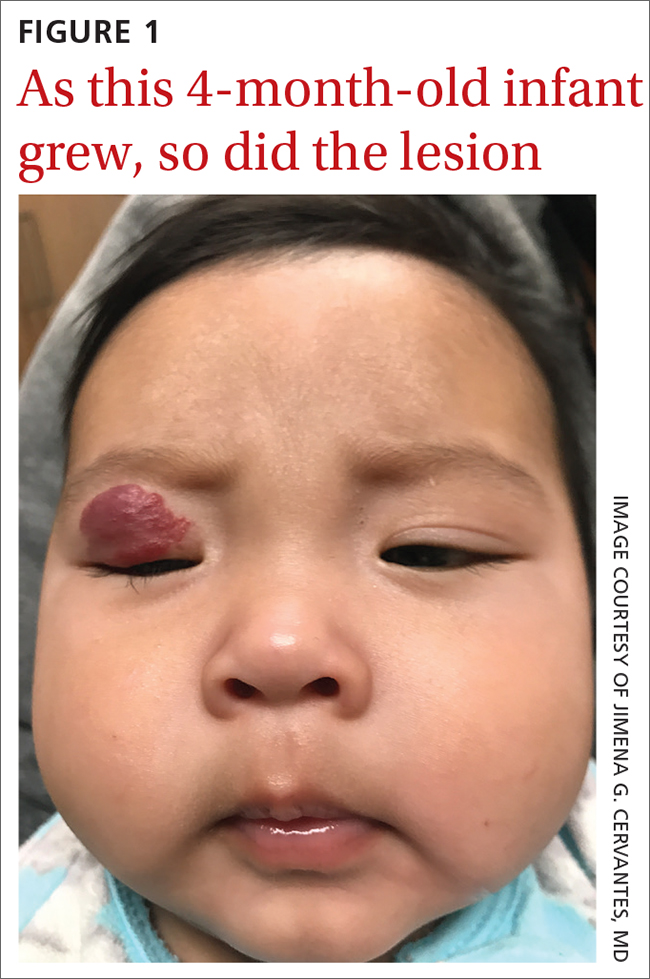

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

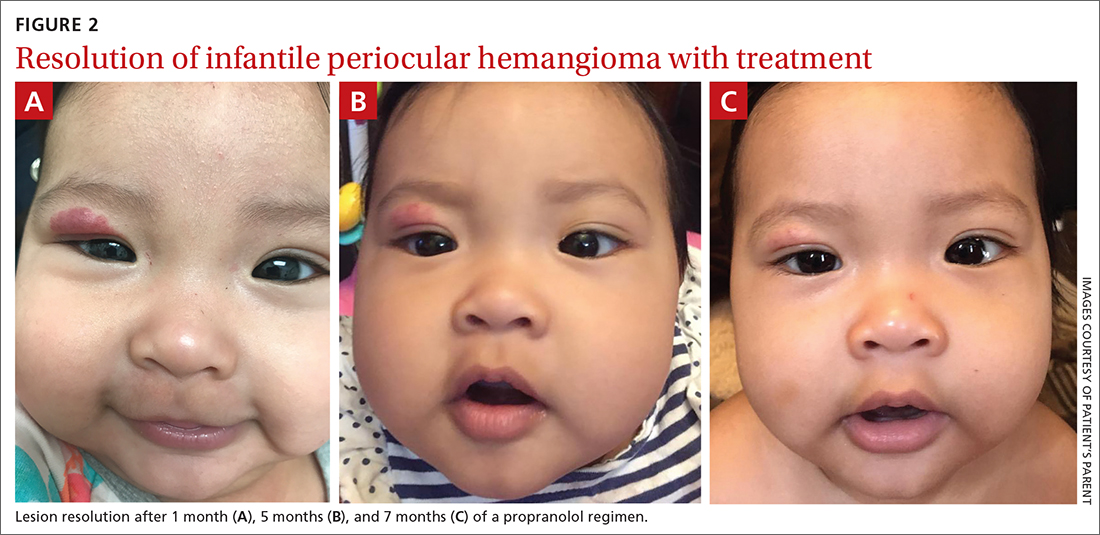

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

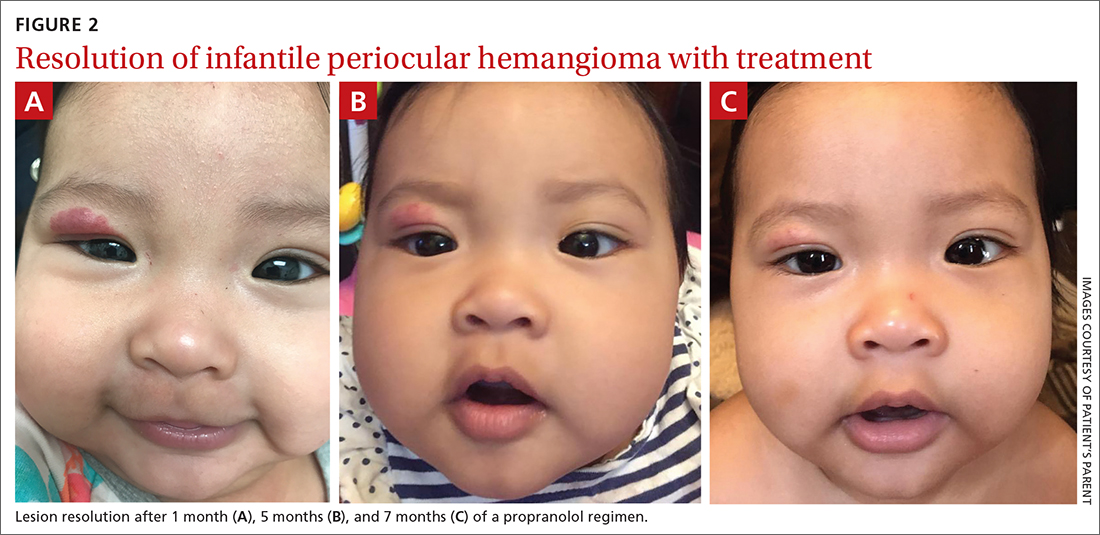

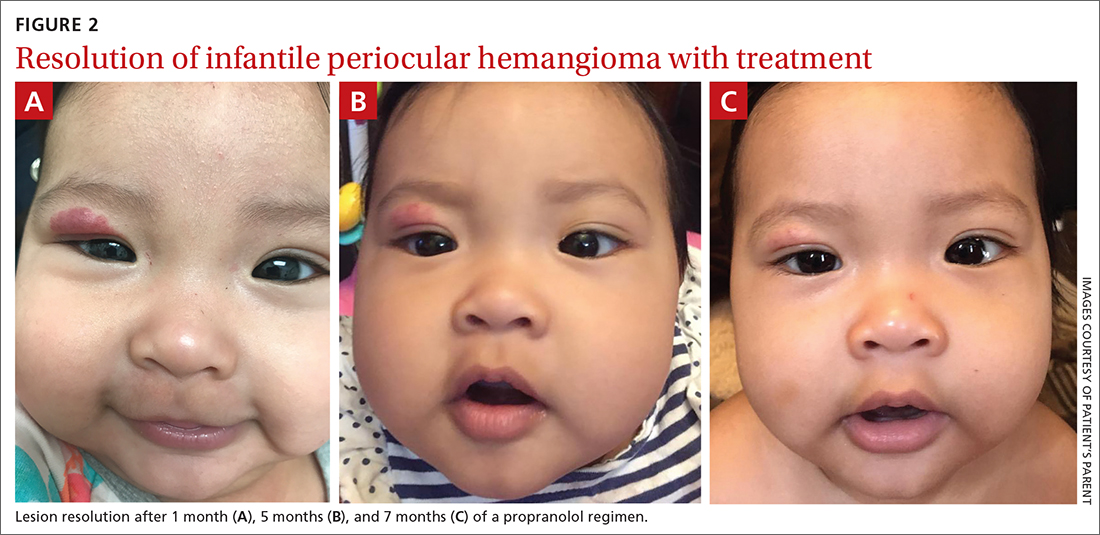

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

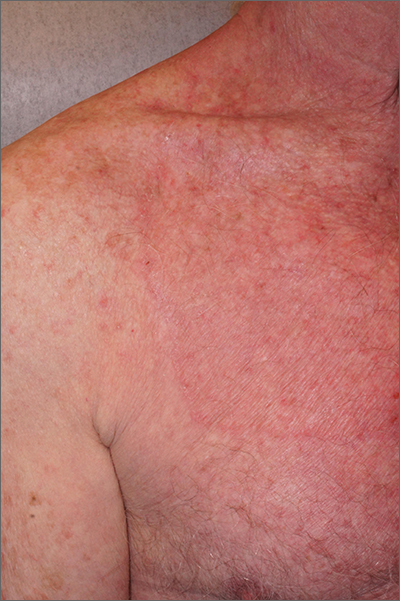

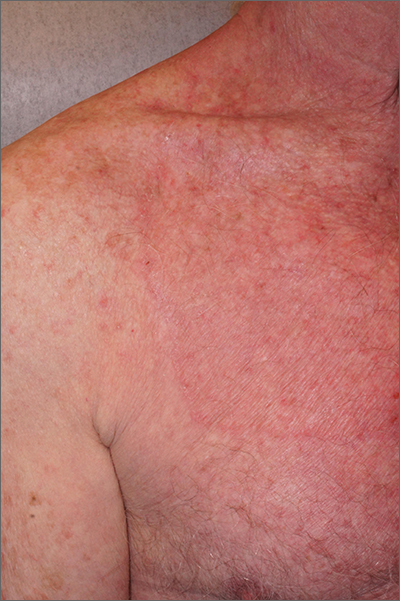

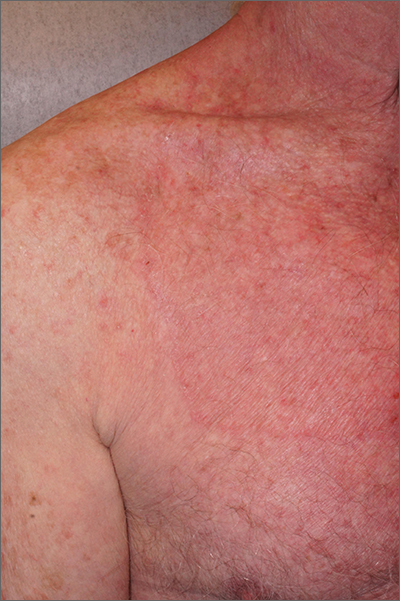

Circular patch on chest

A skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep confirmed the presence of branching hyphae, consistent with tinea corporis. The large size of this plaque could have easily made this diagnosis more difficult. When tinea corporis is suspected, look at the edge of the plaque; there is often thin scale and sometimes small pustules corresponding to follicular involvement.

Commonly called by the misnomer “ringworm,” tinea corporis is a skin infection caused by a wide variety of dermatophytes and affects all ages, sexes, and skin types. Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton species are frequently isolated.1 Patients with atopic dermatitis or weakened immunity may be more susceptible to more frequent or long-lasting episodes. Diabetes may have contributed to the extent of the disease in this case.

Patients with tinea corporis present with one or several annular patches to plaques that grow in size. When the source of contagion is an animal, inflammation can be dramatic. In the case above, there was minimal to no itching and the patient didn’t notice the rash; thus, it was able to enlarge for months.

Treatment options include systemic and topical antifungal therapy. Consideration should be given to the severity of the disease and causal organism. Azoles, terbinafine, and ciclopirox are common treatment options. Topical therapy with an appropriately selected antifungal for 1 to 6 weeks, based on clinical response, is safe and effective. It is important to consider other foci of infection, including the feet and hands. More extensive disease may be treated with oral therapy such as terbinafine, fluconazole, or itraconazole.

Because of the extent of the disease and the challenge of effective coverage with topical therapy, this patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 3 weeks. The plaque cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

A skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep confirmed the presence of branching hyphae, consistent with tinea corporis. The large size of this plaque could have easily made this diagnosis more difficult. When tinea corporis is suspected, look at the edge of the plaque; there is often thin scale and sometimes small pustules corresponding to follicular involvement.

Commonly called by the misnomer “ringworm,” tinea corporis is a skin infection caused by a wide variety of dermatophytes and affects all ages, sexes, and skin types. Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton species are frequently isolated.1 Patients with atopic dermatitis or weakened immunity may be more susceptible to more frequent or long-lasting episodes. Diabetes may have contributed to the extent of the disease in this case.

Patients with tinea corporis present with one or several annular patches to plaques that grow in size. When the source of contagion is an animal, inflammation can be dramatic. In the case above, there was minimal to no itching and the patient didn’t notice the rash; thus, it was able to enlarge for months.

Treatment options include systemic and topical antifungal therapy. Consideration should be given to the severity of the disease and causal organism. Azoles, terbinafine, and ciclopirox are common treatment options. Topical therapy with an appropriately selected antifungal for 1 to 6 weeks, based on clinical response, is safe and effective. It is important to consider other foci of infection, including the feet and hands. More extensive disease may be treated with oral therapy such as terbinafine, fluconazole, or itraconazole.

Because of the extent of the disease and the challenge of effective coverage with topical therapy, this patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 3 weeks. The plaque cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep confirmed the presence of branching hyphae, consistent with tinea corporis. The large size of this plaque could have easily made this diagnosis more difficult. When tinea corporis is suspected, look at the edge of the plaque; there is often thin scale and sometimes small pustules corresponding to follicular involvement.

Commonly called by the misnomer “ringworm,” tinea corporis is a skin infection caused by a wide variety of dermatophytes and affects all ages, sexes, and skin types. Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton species are frequently isolated.1 Patients with atopic dermatitis or weakened immunity may be more susceptible to more frequent or long-lasting episodes. Diabetes may have contributed to the extent of the disease in this case.

Patients with tinea corporis present with one or several annular patches to plaques that grow in size. When the source of contagion is an animal, inflammation can be dramatic. In the case above, there was minimal to no itching and the patient didn’t notice the rash; thus, it was able to enlarge for months.

Treatment options include systemic and topical antifungal therapy. Consideration should be given to the severity of the disease and causal organism. Azoles, terbinafine, and ciclopirox are common treatment options. Topical therapy with an appropriately selected antifungal for 1 to 6 weeks, based on clinical response, is safe and effective. It is important to consider other foci of infection, including the feet and hands. More extensive disease may be treated with oral therapy such as terbinafine, fluconazole, or itraconazole.

Because of the extent of the disease and the challenge of effective coverage with topical therapy, this patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 3 weeks. The plaque cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

1. Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

Scaly facial plaques

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

Nodule on gardener’s hand

Using an 18-gauge needle, a simple incision and drainage was performed, and copious turbid and bloody material was expressed and cultured for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria, as well as fungus. The patient was started on trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS twice daily while cultures and sensitivities were pending. Cultures grew Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a coagulase-negative staph species known to cause a range of infections from simple skin infections to bacteremia and endocarditis.1 If the drainage had been viscous and clear to blood-tinged, that would have been more consistent with a ganglion cyst. Lack of drainage would have prompted a small punch biopsy to exclude a tumor.

Fortunately, S lugdunensis is often broadly sensitive to antibiotics, although treatment choices should follow antibiotic sensitivity testing. Any signs of systemic illness should be worked up with blood cultures and consideration of endocarditis or involvement of an implant. Penicillin is recommended as a first line systemic agent if sensitivities support this, and for abscesses, incision and drainage is recommended. The length of treatment for skin infections is generally 1 to 2 weeks, guided by response to therapy.

This patient’s nodule resolved following the incision and drainage and 7 days of therapy with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Kleiner E, Monk AB, Archer GL, et al. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus lugdunensis isolated from routine cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:801-803. doi: 10.1086/656280

Using an 18-gauge needle, a simple incision and drainage was performed, and copious turbid and bloody material was expressed and cultured for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria, as well as fungus. The patient was started on trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS twice daily while cultures and sensitivities were pending. Cultures grew Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a coagulase-negative staph species known to cause a range of infections from simple skin infections to bacteremia and endocarditis.1 If the drainage had been viscous and clear to blood-tinged, that would have been more consistent with a ganglion cyst. Lack of drainage would have prompted a small punch biopsy to exclude a tumor.

Fortunately, S lugdunensis is often broadly sensitive to antibiotics, although treatment choices should follow antibiotic sensitivity testing. Any signs of systemic illness should be worked up with blood cultures and consideration of endocarditis or involvement of an implant. Penicillin is recommended as a first line systemic agent if sensitivities support this, and for abscesses, incision and drainage is recommended. The length of treatment for skin infections is generally 1 to 2 weeks, guided by response to therapy.

This patient’s nodule resolved following the incision and drainage and 7 days of therapy with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Using an 18-gauge needle, a simple incision and drainage was performed, and copious turbid and bloody material was expressed and cultured for aerobic and acid-fast bacteria, as well as fungus. The patient was started on trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS twice daily while cultures and sensitivities were pending. Cultures grew Staphylococcus lugdunensis, a coagulase-negative staph species known to cause a range of infections from simple skin infections to bacteremia and endocarditis.1 If the drainage had been viscous and clear to blood-tinged, that would have been more consistent with a ganglion cyst. Lack of drainage would have prompted a small punch biopsy to exclude a tumor.

Fortunately, S lugdunensis is often broadly sensitive to antibiotics, although treatment choices should follow antibiotic sensitivity testing. Any signs of systemic illness should be worked up with blood cultures and consideration of endocarditis or involvement of an implant. Penicillin is recommended as a first line systemic agent if sensitivities support this, and for abscesses, incision and drainage is recommended. The length of treatment for skin infections is generally 1 to 2 weeks, guided by response to therapy.

This patient’s nodule resolved following the incision and drainage and 7 days of therapy with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Kleiner E, Monk AB, Archer GL, et al. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus lugdunensis isolated from routine cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:801-803. doi: 10.1086/656280

1. Kleiner E, Monk AB, Archer GL, et al. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus lugdunensis isolated from routine cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:801-803. doi: 10.1086/656280

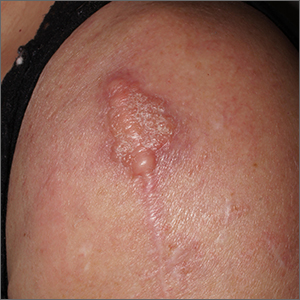

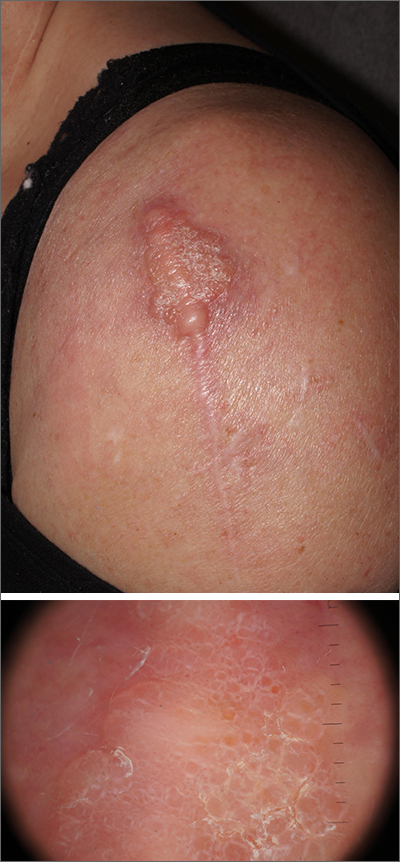

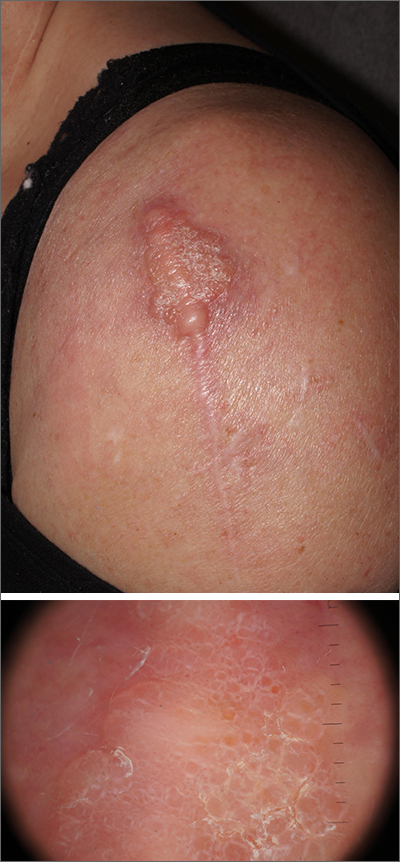

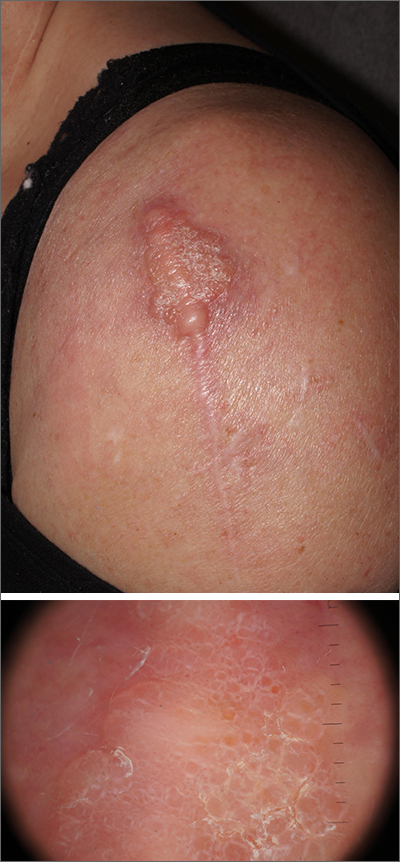

Scar overgrowth

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermatopathology was consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous myxoma (CM). There are very few dermoscopic descriptions of CM in the literature, so diagnostic features are not established. However, the absence of more diagnostic features of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) increases the likelihood of a rare diagnosis, such as CM.

CMs are rare benign neoplasms that manifest most commonly in young adults as small (< 1 cm) flesh-colored to blue papules on the head, neck, and trunk. The size of this particular CM was an outlier. CMs may be associated with Carney Complex (CNC), a rare inherited syndrome that has been linked to multiple endocrine neoplasias—namely, pituitary adenomas, testicular Sertoli cell tumors, thyroid tumors, and cardiac atrial myxomas.1 Additionally, in CNC, lentigines and multiple blue nevi develop on the skin and mucosal surfaces.

The differential diagnosis for a large, pink to flesh-colored nodule of this size includes benign histiocytoma, SCC, CM, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Benign histiocytomas and SCCs are much more common than CM. Clinical features only hint at the correct diagnosis, which must be made histologically.

Patients with CMs benefit from ongoing dermatology surveillance to monitor for the development of atypical nevi or new CMs. In this case, a wide excision with generous margins was planned with plastic surgery. (CMs have been reported to recur after surgery, which is why wide margins are essential.)

Additionally, 2 factors prompted an echocardiogram: the association between CMs and possible cardiac tumors and the patient’s need to undergo future orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. No cardiac tumors were visible on echocardiogram. Thyroid imaging and genetic evaluation were planned but not completed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

1. Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-18. doi: 10.1111/cup.12749.

Blue-black hyperpigmentation on the extremities

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.

Other metals implicated in skin hyperpigmentation include arsenic, gold, mercury, and iron. Review of all supplements and herbal remedies in patients presenting with skin hyperpigmentation is crucial.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent with a rare but unique adverse effect of inducing flagellate hyperpigmentation that favors the chest, abdomen, or back. This may be induced by trauma or scratching and is often transient. Hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to either intravenous or intralesional injection of the medication.2

Continue to: In addition to medication...

In addition to medication- or supplement-induced hyperpigmentation, there is a physiologic source that should be considered when a patient presents with lower-extremity hyperpigmentation:

Stasis hyperpigmentation. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities. Commonly due to dysfunctional venous valves or obstruction, stasis hyperpigmentation manifests with red-brown discoloration from dermal hemosiderin deposition.4

Unlike our patient, those with stasis hyperpigmentation may present symptomatically, with associated dry skin, pruritus, induration, and inflammation. Treatment involves management of the underlying venous insufficiency.4

When there’s no obvious cause, be prepared to dig deeper

At the time of initial assessment, a thorough review of systems and detailed medication history, including over-the-counter supplements, should be obtained. Physical examination revealing diffuse, generalized hyperpigmentation with no reliable culprit medication in the patient’s history warrants further laboratory evaluation. This includes ordering renal and liver studies and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone and ferritin and cortisol levels to rule out metabolic or endocrine hyperpigmentation disorders.

Stopping the offending medication is the first step

Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in mild improvement in skin hyperpigmentation over time. Some patients may not experience any improvement. If improvement occurs, it is important to educate patients that it can take several months to years. Dermatology guidelines favor discontinuation of antibiotics for acne or rosacea after 3 to 6 months to avoid bacterial resistance.5 Worsening hyperpigmentation despite medication discontinuation warrants further work-up.

Patients who are distressed by persistent hyperpigmentation can be treated using picosecond or Q-switched lasers.6

Our patient was advised to discontinue the minocycline. Three test spots on his face were treated with pulsed-dye laser, carbon dioxide laser, and dermabrasion. The patient noted that the spots responded better to the carbon dioxide laser and dermabrasion compared to the pulsed-dye laser. He did not follow up for further treatment.

1. Wetter DA. Minocycline hyperpigmentation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:e33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.013

2. Chang MW. Chapter 67: Disorders of hyperpigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al (eds). Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1122-1124.

3. Bowden LP, Royer MC, Hallman JR, et al. Rapid onset of argyria induced by a silver-containing dietary supplement. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:832-835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01755.x

4. Patterson J. Stasis dermatitis. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier;2010: 121-153.

5. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

6. Barrett T, de Zwaan S. Picosecond alexandrite laser is superior to Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: a case study and review of the literature. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:387-390. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1418514

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.

Other metals implicated in skin hyperpigmentation include arsenic, gold, mercury, and iron. Review of all supplements and herbal remedies in patients presenting with skin hyperpigmentation is crucial.

Bleomycin is a chemotherapeutic agent with a rare but unique adverse effect of inducing flagellate hyperpigmentation that favors the chest, abdomen, or back. This may be induced by trauma or scratching and is often transient. Hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to either intravenous or intralesional injection of the medication.2

Continue to: In addition to medication...

In addition to medication- or supplement-induced hyperpigmentation, there is a physiologic source that should be considered when a patient presents with lower-extremity hyperpigmentation:

Stasis hyperpigmentation. Patients with chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities. Commonly due to dysfunctional venous valves or obstruction, stasis hyperpigmentation manifests with red-brown discoloration from dermal hemosiderin deposition.4

Unlike our patient, those with stasis hyperpigmentation may present symptomatically, with associated dry skin, pruritus, induration, and inflammation. Treatment involves management of the underlying venous insufficiency.4

When there’s no obvious cause, be prepared to dig deeper

At the time of initial assessment, a thorough review of systems and detailed medication history, including over-the-counter supplements, should be obtained. Physical examination revealing diffuse, generalized hyperpigmentation with no reliable culprit medication in the patient’s history warrants further laboratory evaluation. This includes ordering renal and liver studies and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone and ferritin and cortisol levels to rule out metabolic or endocrine hyperpigmentation disorders.

Stopping the offending medication is the first step

Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in mild improvement in skin hyperpigmentation over time. Some patients may not experience any improvement. If improvement occurs, it is important to educate patients that it can take several months to years. Dermatology guidelines favor discontinuation of antibiotics for acne or rosacea after 3 to 6 months to avoid bacterial resistance.5 Worsening hyperpigmentation despite medication discontinuation warrants further work-up.

Patients who are distressed by persistent hyperpigmentation can be treated using picosecond or Q-switched lasers.6

Our patient was advised to discontinue the minocycline. Three test spots on his face were treated with pulsed-dye laser, carbon dioxide laser, and dermabrasion. The patient noted that the spots responded better to the carbon dioxide laser and dermabrasion compared to the pulsed-dye laser. He did not follow up for further treatment.

A 68-year-old man with type 2 diabetes presented with progressive hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities and face over the past 3 years. Clinical examination revealed confluent, blue-black hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities (Figure), upper extremities, neck, and face. Laboratory tests and arterial studies were within normal ranges. The patient’s medication list included lisinopril 10 mg/d, metformin 1000 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and omeprazole 20 mg/d.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Hyperpigmentation is a rare but not uncommon adverse effect of long-term minocycline use. In this case, our patient had been taking minocycline for more than 5 years. When seen in our clinic, he said he could not remember why he was taking minocycline and incorrectly assumed it was for his diabetes. Chart review of outside records revealed that it had been prescribed, and refilled annually, by his primary physician for rosacea.

Minocycline hyperpigmentation is subdivided into 3 types:

- Type I manifests with blue-black discoloration in previously inflamed areas of skin.

- Type II manifests with blue-gray pigmentation in previously normal skin areas.

- Type III manifests diffusely with muddy-brown hyperpigmentation on photoexposed skin.

Furthermore, noncutaneous manifestations may occur on the sclera, nails, ear cartilage, bone, oral mucosa, teeth, and thyroid gland.1

Diagnosis focuses on identifying the source

Minocycline is one of many drugs that can induce hyperpigmentation of the skin. In addition to history, examination, and review of the patient’s medication list, there are some clues on exam that may suggest a certain type of medication at play.

Continue to: Antimalarials

Antimalarials. Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine can cause blue-black skin hyperpigmentation in as many as 25% of patients. Common locations include the shins, face, oral mucosa, and subungual skin. This hyperpigmentation rarely fully resolves.2

Amiodarone. Hyperpigmentation secondary to amiodarone use typically is slate-gray in color and involves photoexposed skin. Patients should be counseled that pigmentation may—but does not always—fade with time after discontinuation of the drug.2

Heavy metals. Argyria results from exposure to silver, either ingested orally or applied externally. A common cause of argyria is ingestion of excessive amounts of silver-containing supplements.3 Affected patients present with diffuse slate-gray discoloration of the skin.