User login

Medicare at 50: Is the end near for SGR?

The Sustainable Growth Rate formula. Few aspects of Medicare have been more problematic for physicians.

Designed to control Medicare costs, Congress has spent more since 2003 to delay SGR cuts than it would cost to fund current repeal legislation.

Passed as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the SGR was designed to make sure Medicare expenditures did not grow faster than the Gross Domestic Product based on four factors: estimated change in physician fees, estimated number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, estimated 10-year average change in GDP, and estimated changes in expenditures due to law or regulation.

It was not, however, designed to keep up with the Baby Boom. Because it does not adjust for the influx of boomers, it guarantees to produce pay cuts just as demand for physician services grows.

The next pay cut – 21% this time – is slated for April 1.

For doctors, the constant specter of lower payments simply makes it hard to do business.

“Each year, when there is supposedly a cut, it is a consideration for practices that they have to create some contingency thinking, ‘if this were actually to take place, how will I continue to maintain my practice?’ ” Dr. Robert Juhasz, president of the American Osteopathic Association, said in an interview. “If they have a high Medicare population that they take care of, and certainly if there was that kind of a cut, they could not sustain that and would have to make changes.”

Dr. Blase Polite, chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Government Relations Committee, agreed. “Ever since the flawed formula was put in place, it has created yearly uncertainty. In recent years, we have had it to the point where the SGR cuts went into effect and then we had to do things like hold bills for a month or 2 months to resubmit them when the SGR would get patched. It became an absolute nightmare from a small business operating standpoint.”

But the tyranny of the SGR may have outgrown itself. In January, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services announced a major expansion of its efforts to base physicians’ Medicare pay on value instead of volume, calling for half of all Medicare payments to be out of the fee-for-service system by 2018.

“This is the first time in the history of the program that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payment models have been set for Medicare,” HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell said in an editorial Jan. 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500445).

The goal is “to move away from the old way of doing things, which amounted to, ‘the more you do, the more you get paid,’ by linking nearly all pay to quality and value in some way to see that we are spending smarter,” Ms. Burwell said in a blog post on the HHS website.

As part of that effort, the department aims to have 30% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models by the end of 2016.

Further, real efforts to repeal the SGR took hold in the last Congress, with strong support to pass legislation among lawmakers of both parties in the House and in the Senate. H.R. 4015, SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014, passed the House but was not taken up by the Senate.

“We were cautiously optimistic that this 17th year of trying to repeal the SGR might have been the successful one,” Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, president of the American College of Cardiology, said in an interview. He said that the sticking point seemed to be that “there was no politically viable way to pay for it.”

Dr. David A. Fleming, president of the American College of Physicians, noted in a statement that finding the money had hung up what otherwise was huge progress: a bill that members of the House and Senate, Republicans and Democrats had put together, and that ultimately passed the House.

Renewed efforts at repeal are underway in the current Congress. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Health Subcommittee held 2 days of hearings in January, hearing from doctors and health economists on how to cover the $140 billion cost of SGR repeal. Although experts presented their thoughts on where the health care sector could come up with the money, Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the full committee, recently suggested that the funding might come from outside the health care sector, such as from his proposal to legalize Internet poker.

But with time running short, some believe that another SGR patch is in the cards and that repeal will come attached to a broader piece of legislation at the end of the year.

“I don’t think there is any way it gets fixed by the March deadline because the payment offsets are just far too complicated. I think that it has to wait to be incorporated, my guess, in a larger bill,” ASCO’s Dr. Polite said. “That’s how I would do it. You want to include it in a much bigger package of tax reforms, perhaps other entitlement reforms where there’s a lot of pluses and minuses of money flow and the $140 billion for SGR is easy to take care of in that.”

He also cautioned that if it is not taken care of this year, it could be at least another 2 years before the window for repeal is opened.

“There is some talk about it getting delayed 18 months,” Dr. Polite said. “I hope that doesn’t happen because if you kick this can down the road 18 months, you basically put us in the 2016 election cycle and nobody’s coming up with $140 billion during that time. Eighteen months basically means we will see you after the 2016 presidential election. And it would be a shame.”

SGR: A patchwork of fixes

Congress has passed 17 different bills to prevent across-the-board Medicare pay cuts due to the SGR, ranging from 3.3% (2005) to 27.4% (2012). Nearly all have been paid for by some kind of offset. Here’s the sordid history:

• 2003 Consolidated Appropriations Act (4.9%)

• 2004 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (4.5%)

• 2005 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (3.3%)

• 2006 Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (4.4%)

• 2007 Tax Relief and Health Care Act (5%)

• 2008 Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP Extension Act (about 10.%)

• 2009 Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (16%)

• 2010 DOD Appropriations Act plus two Temporary Extension Acts (21%)

• 2010 Preservation of Access to Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Act (21.2%)

• 2010 Physician Payment and Therapy Relief Act (23% )

• 2011 Medicare and Medicaid Extenders Act (25%)

• 2012 Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act (27.4%)

• 2012 Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act (27.4%)

• 2013 American Tax Payer Relief Act (26.5%)

• 2014 Pathway for SGR Reform Act (20.1%)

• 2014 Protecting Access To Medicare Act (24% )

The Sustainable Growth Rate formula. Few aspects of Medicare have been more problematic for physicians.

Designed to control Medicare costs, Congress has spent more since 2003 to delay SGR cuts than it would cost to fund current repeal legislation.

Passed as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the SGR was designed to make sure Medicare expenditures did not grow faster than the Gross Domestic Product based on four factors: estimated change in physician fees, estimated number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, estimated 10-year average change in GDP, and estimated changes in expenditures due to law or regulation.

It was not, however, designed to keep up with the Baby Boom. Because it does not adjust for the influx of boomers, it guarantees to produce pay cuts just as demand for physician services grows.

The next pay cut – 21% this time – is slated for April 1.

For doctors, the constant specter of lower payments simply makes it hard to do business.

“Each year, when there is supposedly a cut, it is a consideration for practices that they have to create some contingency thinking, ‘if this were actually to take place, how will I continue to maintain my practice?’ ” Dr. Robert Juhasz, president of the American Osteopathic Association, said in an interview. “If they have a high Medicare population that they take care of, and certainly if there was that kind of a cut, they could not sustain that and would have to make changes.”

Dr. Blase Polite, chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Government Relations Committee, agreed. “Ever since the flawed formula was put in place, it has created yearly uncertainty. In recent years, we have had it to the point where the SGR cuts went into effect and then we had to do things like hold bills for a month or 2 months to resubmit them when the SGR would get patched. It became an absolute nightmare from a small business operating standpoint.”

But the tyranny of the SGR may have outgrown itself. In January, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services announced a major expansion of its efforts to base physicians’ Medicare pay on value instead of volume, calling for half of all Medicare payments to be out of the fee-for-service system by 2018.

“This is the first time in the history of the program that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payment models have been set for Medicare,” HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell said in an editorial Jan. 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500445).

The goal is “to move away from the old way of doing things, which amounted to, ‘the more you do, the more you get paid,’ by linking nearly all pay to quality and value in some way to see that we are spending smarter,” Ms. Burwell said in a blog post on the HHS website.

As part of that effort, the department aims to have 30% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models by the end of 2016.

Further, real efforts to repeal the SGR took hold in the last Congress, with strong support to pass legislation among lawmakers of both parties in the House and in the Senate. H.R. 4015, SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014, passed the House but was not taken up by the Senate.

“We were cautiously optimistic that this 17th year of trying to repeal the SGR might have been the successful one,” Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, president of the American College of Cardiology, said in an interview. He said that the sticking point seemed to be that “there was no politically viable way to pay for it.”

Dr. David A. Fleming, president of the American College of Physicians, noted in a statement that finding the money had hung up what otherwise was huge progress: a bill that members of the House and Senate, Republicans and Democrats had put together, and that ultimately passed the House.

Renewed efforts at repeal are underway in the current Congress. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Health Subcommittee held 2 days of hearings in January, hearing from doctors and health economists on how to cover the $140 billion cost of SGR repeal. Although experts presented their thoughts on where the health care sector could come up with the money, Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the full committee, recently suggested that the funding might come from outside the health care sector, such as from his proposal to legalize Internet poker.

But with time running short, some believe that another SGR patch is in the cards and that repeal will come attached to a broader piece of legislation at the end of the year.

“I don’t think there is any way it gets fixed by the March deadline because the payment offsets are just far too complicated. I think that it has to wait to be incorporated, my guess, in a larger bill,” ASCO’s Dr. Polite said. “That’s how I would do it. You want to include it in a much bigger package of tax reforms, perhaps other entitlement reforms where there’s a lot of pluses and minuses of money flow and the $140 billion for SGR is easy to take care of in that.”

He also cautioned that if it is not taken care of this year, it could be at least another 2 years before the window for repeal is opened.

“There is some talk about it getting delayed 18 months,” Dr. Polite said. “I hope that doesn’t happen because if you kick this can down the road 18 months, you basically put us in the 2016 election cycle and nobody’s coming up with $140 billion during that time. Eighteen months basically means we will see you after the 2016 presidential election. And it would be a shame.”

SGR: A patchwork of fixes

Congress has passed 17 different bills to prevent across-the-board Medicare pay cuts due to the SGR, ranging from 3.3% (2005) to 27.4% (2012). Nearly all have been paid for by some kind of offset. Here’s the sordid history:

• 2003 Consolidated Appropriations Act (4.9%)

• 2004 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (4.5%)

• 2005 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (3.3%)

• 2006 Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (4.4%)

• 2007 Tax Relief and Health Care Act (5%)

• 2008 Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP Extension Act (about 10.%)

• 2009 Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (16%)

• 2010 DOD Appropriations Act plus two Temporary Extension Acts (21%)

• 2010 Preservation of Access to Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Act (21.2%)

• 2010 Physician Payment and Therapy Relief Act (23% )

• 2011 Medicare and Medicaid Extenders Act (25%)

• 2012 Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act (27.4%)

• 2012 Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act (27.4%)

• 2013 American Tax Payer Relief Act (26.5%)

• 2014 Pathway for SGR Reform Act (20.1%)

• 2014 Protecting Access To Medicare Act (24% )

The Sustainable Growth Rate formula. Few aspects of Medicare have been more problematic for physicians.

Designed to control Medicare costs, Congress has spent more since 2003 to delay SGR cuts than it would cost to fund current repeal legislation.

Passed as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the SGR was designed to make sure Medicare expenditures did not grow faster than the Gross Domestic Product based on four factors: estimated change in physician fees, estimated number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, estimated 10-year average change in GDP, and estimated changes in expenditures due to law or regulation.

It was not, however, designed to keep up with the Baby Boom. Because it does not adjust for the influx of boomers, it guarantees to produce pay cuts just as demand for physician services grows.

The next pay cut – 21% this time – is slated for April 1.

For doctors, the constant specter of lower payments simply makes it hard to do business.

“Each year, when there is supposedly a cut, it is a consideration for practices that they have to create some contingency thinking, ‘if this were actually to take place, how will I continue to maintain my practice?’ ” Dr. Robert Juhasz, president of the American Osteopathic Association, said in an interview. “If they have a high Medicare population that they take care of, and certainly if there was that kind of a cut, they could not sustain that and would have to make changes.”

Dr. Blase Polite, chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Government Relations Committee, agreed. “Ever since the flawed formula was put in place, it has created yearly uncertainty. In recent years, we have had it to the point where the SGR cuts went into effect and then we had to do things like hold bills for a month or 2 months to resubmit them when the SGR would get patched. It became an absolute nightmare from a small business operating standpoint.”

But the tyranny of the SGR may have outgrown itself. In January, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services announced a major expansion of its efforts to base physicians’ Medicare pay on value instead of volume, calling for half of all Medicare payments to be out of the fee-for-service system by 2018.

“This is the first time in the history of the program that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payment models have been set for Medicare,” HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell said in an editorial Jan. 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500445).

The goal is “to move away from the old way of doing things, which amounted to, ‘the more you do, the more you get paid,’ by linking nearly all pay to quality and value in some way to see that we are spending smarter,” Ms. Burwell said in a blog post on the HHS website.

As part of that effort, the department aims to have 30% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models by the end of 2016.

Further, real efforts to repeal the SGR took hold in the last Congress, with strong support to pass legislation among lawmakers of both parties in the House and in the Senate. H.R. 4015, SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014, passed the House but was not taken up by the Senate.

“We were cautiously optimistic that this 17th year of trying to repeal the SGR might have been the successful one,” Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara, president of the American College of Cardiology, said in an interview. He said that the sticking point seemed to be that “there was no politically viable way to pay for it.”

Dr. David A. Fleming, president of the American College of Physicians, noted in a statement that finding the money had hung up what otherwise was huge progress: a bill that members of the House and Senate, Republicans and Democrats had put together, and that ultimately passed the House.

Renewed efforts at repeal are underway in the current Congress. The House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Health Subcommittee held 2 days of hearings in January, hearing from doctors and health economists on how to cover the $140 billion cost of SGR repeal. Although experts presented their thoughts on where the health care sector could come up with the money, Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), chairman of the full committee, recently suggested that the funding might come from outside the health care sector, such as from his proposal to legalize Internet poker.

But with time running short, some believe that another SGR patch is in the cards and that repeal will come attached to a broader piece of legislation at the end of the year.

“I don’t think there is any way it gets fixed by the March deadline because the payment offsets are just far too complicated. I think that it has to wait to be incorporated, my guess, in a larger bill,” ASCO’s Dr. Polite said. “That’s how I would do it. You want to include it in a much bigger package of tax reforms, perhaps other entitlement reforms where there’s a lot of pluses and minuses of money flow and the $140 billion for SGR is easy to take care of in that.”

He also cautioned that if it is not taken care of this year, it could be at least another 2 years before the window for repeal is opened.

“There is some talk about it getting delayed 18 months,” Dr. Polite said. “I hope that doesn’t happen because if you kick this can down the road 18 months, you basically put us in the 2016 election cycle and nobody’s coming up with $140 billion during that time. Eighteen months basically means we will see you after the 2016 presidential election. And it would be a shame.”

SGR: A patchwork of fixes

Congress has passed 17 different bills to prevent across-the-board Medicare pay cuts due to the SGR, ranging from 3.3% (2005) to 27.4% (2012). Nearly all have been paid for by some kind of offset. Here’s the sordid history:

• 2003 Consolidated Appropriations Act (4.9%)

• 2004 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (4.5%)

• 2005 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvements, and Modernization Act (3.3%)

• 2006 Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (4.4%)

• 2007 Tax Relief and Health Care Act (5%)

• 2008 Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP Extension Act (about 10.%)

• 2009 Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (16%)

• 2010 DOD Appropriations Act plus two Temporary Extension Acts (21%)

• 2010 Preservation of Access to Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Act (21.2%)

• 2010 Physician Payment and Therapy Relief Act (23% )

• 2011 Medicare and Medicaid Extenders Act (25%)

• 2012 Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act (27.4%)

• 2012 Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act (27.4%)

• 2013 American Tax Payer Relief Act (26.5%)

• 2014 Pathway for SGR Reform Act (20.1%)

• 2014 Protecting Access To Medicare Act (24% )

Cost of ACA lowers budget deficit

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has reduced its budget deficit estimate over the next decade because of lower projected costs for the Affordable Care Act.

Updated projections released March 9 by the CBO find cumulative deficits between 2016 and 2025 will be $431 billion less than the office’s January projection of $7.6 trillion.

Lower costs for ACA provisions driven by smaller spending growth for insurance subsidies, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Medicaid drove the reduced figure, the CBO said in an online post.

The total projected cost of ACA provisions to the federal government over the next 9 years is $1.2 billion, 11% less than CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in January.

However, CBO predicts the annual budget deficit will rise to $486 billion in fiscal 2015, slightly higher than last year’s shortfall. The latest deficit estimate for 2015 is $18 billion higher than CBO had originally projected.

CBO said the estimated rise stems primarily from a projected rise in spending for student loans, Medicaid, and Medicare. The deficit for 2015 represents a slightly lower percentage of gross domestic product of 2.7%, compared with 2.8% last year.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has reduced its budget deficit estimate over the next decade because of lower projected costs for the Affordable Care Act.

Updated projections released March 9 by the CBO find cumulative deficits between 2016 and 2025 will be $431 billion less than the office’s January projection of $7.6 trillion.

Lower costs for ACA provisions driven by smaller spending growth for insurance subsidies, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Medicaid drove the reduced figure, the CBO said in an online post.

The total projected cost of ACA provisions to the federal government over the next 9 years is $1.2 billion, 11% less than CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in January.

However, CBO predicts the annual budget deficit will rise to $486 billion in fiscal 2015, slightly higher than last year’s shortfall. The latest deficit estimate for 2015 is $18 billion higher than CBO had originally projected.

CBO said the estimated rise stems primarily from a projected rise in spending for student loans, Medicaid, and Medicare. The deficit for 2015 represents a slightly lower percentage of gross domestic product of 2.7%, compared with 2.8% last year.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has reduced its budget deficit estimate over the next decade because of lower projected costs for the Affordable Care Act.

Updated projections released March 9 by the CBO find cumulative deficits between 2016 and 2025 will be $431 billion less than the office’s January projection of $7.6 trillion.

Lower costs for ACA provisions driven by smaller spending growth for insurance subsidies, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Medicaid drove the reduced figure, the CBO said in an online post.

The total projected cost of ACA provisions to the federal government over the next 9 years is $1.2 billion, 11% less than CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in January.

However, CBO predicts the annual budget deficit will rise to $486 billion in fiscal 2015, slightly higher than last year’s shortfall. The latest deficit estimate for 2015 is $18 billion higher than CBO had originally projected.

CBO said the estimated rise stems primarily from a projected rise in spending for student loans, Medicaid, and Medicare. The deficit for 2015 represents a slightly lower percentage of gross domestic product of 2.7%, compared with 2.8% last year.

On Twitter @legal_med

LISTEN NOW: David Pressel, MD, PHD, FHM, discusses violence in hospitals

DAVID PRESSEL, MD, PHD, FHM, medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, talks about the nature of violence in hospitals and a training program he has helped put into place at his center.

DAVID PRESSEL, MD, PHD, FHM, medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, talks about the nature of violence in hospitals and a training program he has helped put into place at his center.

DAVID PRESSEL, MD, PHD, FHM, medical director of inpatient services at Nemours Children’s Health System, talks about the nature of violence in hospitals and a training program he has helped put into place at his center.

LISTEN NOW: David Lichtman, PA, explains factors to determine when hospitalists perform procedures

DAVID LICHTMAN, PA, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service, explains the complicated set of factors used by

individual hospitals to determine which procedures fall under the scope of their HM practitioners.

DAVID LICHTMAN, PA, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service, explains the complicated set of factors used by

individual hospitals to determine which procedures fall under the scope of their HM practitioners.

DAVID LICHTMAN, PA, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service, explains the complicated set of factors used by

individual hospitals to determine which procedures fall under the scope of their HM practitioners.

Supreme Court justices appear split on ACA tax subsidies

Supreme Court justices appear to differ over whether the Affordable Care Act allows tax subsidies for patients who purchase insurance through the federal exchange.

During oral arguments March 4 in King v. Burwell, justices expressed mixed perspective not only on the ACA language on tax credits, but also on the ramifications of striking down use of the subsidies in states that rely on the federal exchange.

“One thing that was surprising was that the justices spent a lot of time asking questions about the consequences of agreeing with the petitioners,” said Brian M. Pinheiro, a Philadelphia-based health care and employee benefits attorney who attended the oral arguments. He said that some justices asked questions to find out “ ‘if the court struck down subsidies in the 34 states that had federal exchanges, what would that do to that law? What would that do to the health system, and could Congress have intended that result?’ I think that did trouble several of the justices who were thinking of the ultimate consequences of the decision.”

King v. Burwell centers on whether people who live in states that rely on the federal marketplace are eligible for tax credits to purchase insurance or whether such assistance can go only to residents whose states run their own marketplaces. The ACA states that tax credits apply to insurance purchased through an exchange “established by the state.” Challengers argue the law does not mention the federal exchange. The government interprets the ACA to allow subsidies whenever patients buys insurance on any exchange. Only 16 states and the District of Columbia have established a state-based exchange.

Recent research from the Urban Institute predicts that as many as 6 million Americans could lose their insurance coverage if the court rules against the government and strikes down the federal subsidies. Further, analysts from consultancy Avalere Health predict also that patients could see significant premium increases and health care providers could lose billions due to increased uncompensated care.

During the March 4 debate, the court’s four liberal justices appeared to side with the government’s reading of the law, including Justice Ruth Bader-Ginsberg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, said Eric J. Segall, professor of law at Georgia State University, Atlanta. Justice Sotomayor said the plaintiffs’ interpretation of the ACA would mean Congress intended to coerce states into creating exchanges.

“The choice the state had was establish your own exchange or let the federal government establish it for you,” Justice Sotomayor said to plaintiff’s attorney Michael Carvin. “If we read it the way you’re saying, then we’re going to read a statute as intruding on the federal/state relationship because then the states are going to be coerced into establishing their own exchanges. In those states that don’t, their citizens don’t receive subsidies. We’re going to have the death spiral that this system was created to avoid.”

But the high court’s more conservative judges, including Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Antonin Scalia, appeared to agree with the plaintiff’s reading. Justice Scalia noted that whether the ACA functions well or not based on King’s interpretation should not be the issue.

“Is it not the case that if the only reasonable interpretation of a particular provision produces disastrous consequences in the rest of the statute, it nonetheless means what it says?” Justice Scalia asked Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr., who represented the government. Justice Scalia stressed that addressing flaws within a law is the business of legislators. “You really think Congress is just going to sit there while all of these disastrous consequences ensue?”

Justices also grilled attorneys about whether the plaintiffs in the case have standing to sue, an issue that arose late in the litigation. The question surrounds whether all four plaintiffs have legal authority to challenge the ACA since some, or all, may not be penalized if they do not buy health insurance. Mr. Carvin argued the plaintiffs have clear standing to sue, while Mr. Verrilli indicated that the government was not interested in having the case decided on the basis of standing.

Although dismissing the case based on standing would be an easy out for the Supreme Court, the outcome is highly unlikely, Mr. Segall said.

“The court will do what it wants, regardless of the law of standing,” he said in an interview. “It felt like nobody wanted to get rid of this case based on standing. They’re going to basically ignore” the issue.

Mr. Pinheiro said that he believed the government had the stronger case. He predicted the Supreme Court will rule 6-3 in favor of the government.

Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute had originally predicted a 6-3 rule in favor of the challengers. However, after the arguments, he now says it’s anyone’s call.

“My only prediction is that it’s a complete toss-up,” he said in an interview. “Whichever side anyone thought had the edge before argument has to temper their expectations, because I would give each side an even 50-50 shot at this point.”

The Justices’ decision is expected in June.

On Twitter @legal_med

Supreme Court justices appear to differ over whether the Affordable Care Act allows tax subsidies for patients who purchase insurance through the federal exchange.

During oral arguments March 4 in King v. Burwell, justices expressed mixed perspective not only on the ACA language on tax credits, but also on the ramifications of striking down use of the subsidies in states that rely on the federal exchange.

“One thing that was surprising was that the justices spent a lot of time asking questions about the consequences of agreeing with the petitioners,” said Brian M. Pinheiro, a Philadelphia-based health care and employee benefits attorney who attended the oral arguments. He said that some justices asked questions to find out “ ‘if the court struck down subsidies in the 34 states that had federal exchanges, what would that do to that law? What would that do to the health system, and could Congress have intended that result?’ I think that did trouble several of the justices who were thinking of the ultimate consequences of the decision.”

King v. Burwell centers on whether people who live in states that rely on the federal marketplace are eligible for tax credits to purchase insurance or whether such assistance can go only to residents whose states run their own marketplaces. The ACA states that tax credits apply to insurance purchased through an exchange “established by the state.” Challengers argue the law does not mention the federal exchange. The government interprets the ACA to allow subsidies whenever patients buys insurance on any exchange. Only 16 states and the District of Columbia have established a state-based exchange.

Recent research from the Urban Institute predicts that as many as 6 million Americans could lose their insurance coverage if the court rules against the government and strikes down the federal subsidies. Further, analysts from consultancy Avalere Health predict also that patients could see significant premium increases and health care providers could lose billions due to increased uncompensated care.

During the March 4 debate, the court’s four liberal justices appeared to side with the government’s reading of the law, including Justice Ruth Bader-Ginsberg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, said Eric J. Segall, professor of law at Georgia State University, Atlanta. Justice Sotomayor said the plaintiffs’ interpretation of the ACA would mean Congress intended to coerce states into creating exchanges.

“The choice the state had was establish your own exchange or let the federal government establish it for you,” Justice Sotomayor said to plaintiff’s attorney Michael Carvin. “If we read it the way you’re saying, then we’re going to read a statute as intruding on the federal/state relationship because then the states are going to be coerced into establishing their own exchanges. In those states that don’t, their citizens don’t receive subsidies. We’re going to have the death spiral that this system was created to avoid.”

But the high court’s more conservative judges, including Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Antonin Scalia, appeared to agree with the plaintiff’s reading. Justice Scalia noted that whether the ACA functions well or not based on King’s interpretation should not be the issue.

“Is it not the case that if the only reasonable interpretation of a particular provision produces disastrous consequences in the rest of the statute, it nonetheless means what it says?” Justice Scalia asked Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr., who represented the government. Justice Scalia stressed that addressing flaws within a law is the business of legislators. “You really think Congress is just going to sit there while all of these disastrous consequences ensue?”

Justices also grilled attorneys about whether the plaintiffs in the case have standing to sue, an issue that arose late in the litigation. The question surrounds whether all four plaintiffs have legal authority to challenge the ACA since some, or all, may not be penalized if they do not buy health insurance. Mr. Carvin argued the plaintiffs have clear standing to sue, while Mr. Verrilli indicated that the government was not interested in having the case decided on the basis of standing.

Although dismissing the case based on standing would be an easy out for the Supreme Court, the outcome is highly unlikely, Mr. Segall said.

“The court will do what it wants, regardless of the law of standing,” he said in an interview. “It felt like nobody wanted to get rid of this case based on standing. They’re going to basically ignore” the issue.

Mr. Pinheiro said that he believed the government had the stronger case. He predicted the Supreme Court will rule 6-3 in favor of the government.

Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute had originally predicted a 6-3 rule in favor of the challengers. However, after the arguments, he now says it’s anyone’s call.

“My only prediction is that it’s a complete toss-up,” he said in an interview. “Whichever side anyone thought had the edge before argument has to temper their expectations, because I would give each side an even 50-50 shot at this point.”

The Justices’ decision is expected in June.

On Twitter @legal_med

Supreme Court justices appear to differ over whether the Affordable Care Act allows tax subsidies for patients who purchase insurance through the federal exchange.

During oral arguments March 4 in King v. Burwell, justices expressed mixed perspective not only on the ACA language on tax credits, but also on the ramifications of striking down use of the subsidies in states that rely on the federal exchange.

“One thing that was surprising was that the justices spent a lot of time asking questions about the consequences of agreeing with the petitioners,” said Brian M. Pinheiro, a Philadelphia-based health care and employee benefits attorney who attended the oral arguments. He said that some justices asked questions to find out “ ‘if the court struck down subsidies in the 34 states that had federal exchanges, what would that do to that law? What would that do to the health system, and could Congress have intended that result?’ I think that did trouble several of the justices who were thinking of the ultimate consequences of the decision.”

King v. Burwell centers on whether people who live in states that rely on the federal marketplace are eligible for tax credits to purchase insurance or whether such assistance can go only to residents whose states run their own marketplaces. The ACA states that tax credits apply to insurance purchased through an exchange “established by the state.” Challengers argue the law does not mention the federal exchange. The government interprets the ACA to allow subsidies whenever patients buys insurance on any exchange. Only 16 states and the District of Columbia have established a state-based exchange.

Recent research from the Urban Institute predicts that as many as 6 million Americans could lose their insurance coverage if the court rules against the government and strikes down the federal subsidies. Further, analysts from consultancy Avalere Health predict also that patients could see significant premium increases and health care providers could lose billions due to increased uncompensated care.

During the March 4 debate, the court’s four liberal justices appeared to side with the government’s reading of the law, including Justice Ruth Bader-Ginsberg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, said Eric J. Segall, professor of law at Georgia State University, Atlanta. Justice Sotomayor said the plaintiffs’ interpretation of the ACA would mean Congress intended to coerce states into creating exchanges.

“The choice the state had was establish your own exchange or let the federal government establish it for you,” Justice Sotomayor said to plaintiff’s attorney Michael Carvin. “If we read it the way you’re saying, then we’re going to read a statute as intruding on the federal/state relationship because then the states are going to be coerced into establishing their own exchanges. In those states that don’t, their citizens don’t receive subsidies. We’re going to have the death spiral that this system was created to avoid.”

But the high court’s more conservative judges, including Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Antonin Scalia, appeared to agree with the plaintiff’s reading. Justice Scalia noted that whether the ACA functions well or not based on King’s interpretation should not be the issue.

“Is it not the case that if the only reasonable interpretation of a particular provision produces disastrous consequences in the rest of the statute, it nonetheless means what it says?” Justice Scalia asked Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr., who represented the government. Justice Scalia stressed that addressing flaws within a law is the business of legislators. “You really think Congress is just going to sit there while all of these disastrous consequences ensue?”

Justices also grilled attorneys about whether the plaintiffs in the case have standing to sue, an issue that arose late in the litigation. The question surrounds whether all four plaintiffs have legal authority to challenge the ACA since some, or all, may not be penalized if they do not buy health insurance. Mr. Carvin argued the plaintiffs have clear standing to sue, while Mr. Verrilli indicated that the government was not interested in having the case decided on the basis of standing.

Although dismissing the case based on standing would be an easy out for the Supreme Court, the outcome is highly unlikely, Mr. Segall said.

“The court will do what it wants, regardless of the law of standing,” he said in an interview. “It felt like nobody wanted to get rid of this case based on standing. They’re going to basically ignore” the issue.

Mr. Pinheiro said that he believed the government had the stronger case. He predicted the Supreme Court will rule 6-3 in favor of the government.

Ilya Shapiro of the Cato Institute had originally predicted a 6-3 rule in favor of the challengers. However, after the arguments, he now says it’s anyone’s call.

“My only prediction is that it’s a complete toss-up,” he said in an interview. “Whichever side anyone thought had the edge before argument has to temper their expectations, because I would give each side an even 50-50 shot at this point.”

The Justices’ decision is expected in June.

On Twitter @legal_med

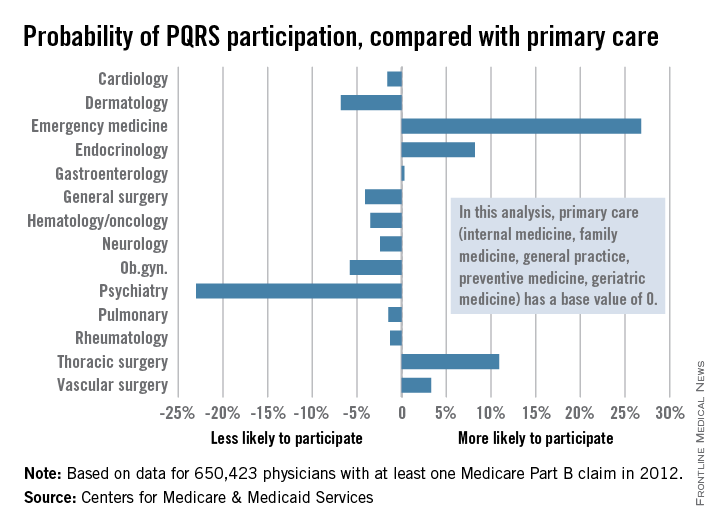

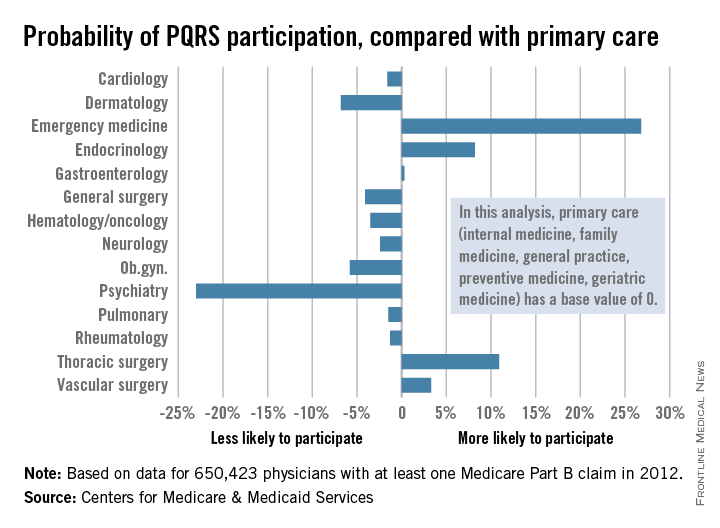

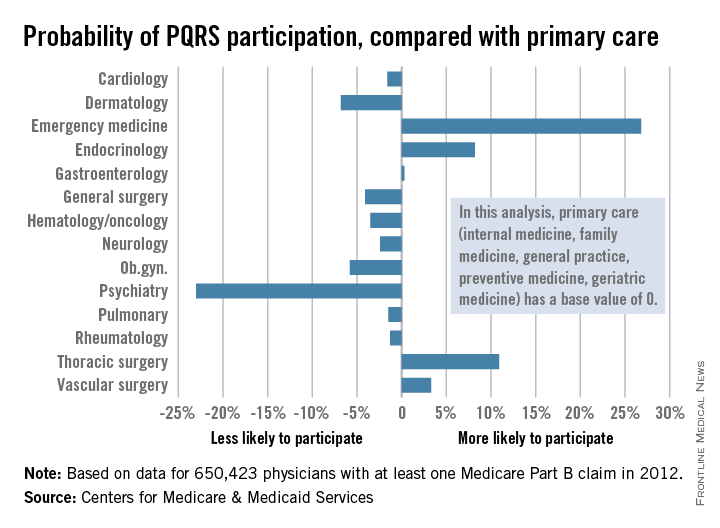

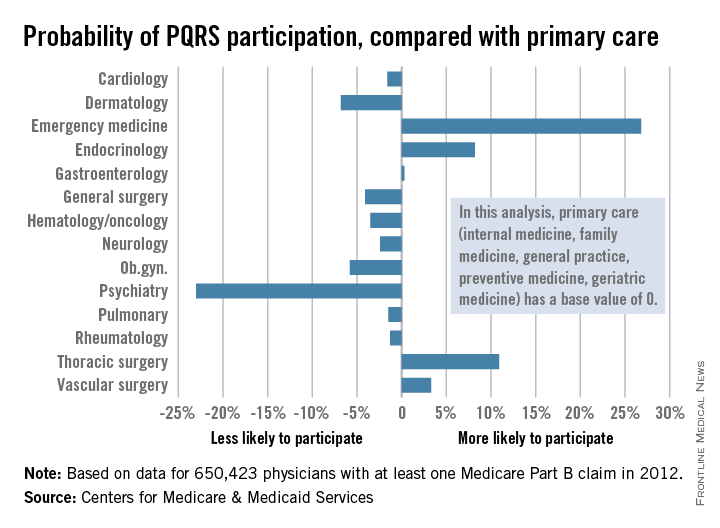

PQRS participation varies by specialty

Participation in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) varies considerably by specialty, according to an new analysis of 2012 data using primary care physicians as the base, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

Emergency medicine physicians were almost 27% more likely to participate in PQRS than were physicians in primary care (internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, preventive medicine, and geriatrics). On the other end of the scale were psychiatrists, who were 23% less likely than were primary care physicians to participate in PQRS, according to the CMS.

Among surgical specialties, general surgeons were 4% less likely to participate in PQRS, but thoracic surgeons and vascular surgeons were 11% and 3%, respectively, more likely to participate, compared with primary care physicians.

The PQRS participation rate in 2012 was 41.3% overall for the 650,423 MDs/DOs who submitted at least one Medicare Part B claim that year. Other health care professionals – including podiatrists, chiropractors, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and physical therapists – are eligible for PQRS but were not included in this analysis, the CMS said.

Participation in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) varies considerably by specialty, according to an new analysis of 2012 data using primary care physicians as the base, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

Emergency medicine physicians were almost 27% more likely to participate in PQRS than were physicians in primary care (internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, preventive medicine, and geriatrics). On the other end of the scale were psychiatrists, who were 23% less likely than were primary care physicians to participate in PQRS, according to the CMS.

Among surgical specialties, general surgeons were 4% less likely to participate in PQRS, but thoracic surgeons and vascular surgeons were 11% and 3%, respectively, more likely to participate, compared with primary care physicians.

The PQRS participation rate in 2012 was 41.3% overall for the 650,423 MDs/DOs who submitted at least one Medicare Part B claim that year. Other health care professionals – including podiatrists, chiropractors, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and physical therapists – are eligible for PQRS but were not included in this analysis, the CMS said.

Participation in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) varies considerably by specialty, according to an new analysis of 2012 data using primary care physicians as the base, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

Emergency medicine physicians were almost 27% more likely to participate in PQRS than were physicians in primary care (internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, preventive medicine, and geriatrics). On the other end of the scale were psychiatrists, who were 23% less likely than were primary care physicians to participate in PQRS, according to the CMS.

Among surgical specialties, general surgeons were 4% less likely to participate in PQRS, but thoracic surgeons and vascular surgeons were 11% and 3%, respectively, more likely to participate, compared with primary care physicians.

The PQRS participation rate in 2012 was 41.3% overall for the 650,423 MDs/DOs who submitted at least one Medicare Part B claim that year. Other health care professionals – including podiatrists, chiropractors, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and physical therapists – are eligible for PQRS but were not included in this analysis, the CMS said.

What Is the Best Approach to a Cavitary Lung Lesion?

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Imaging may reveal a cavitary lesion in the dependent pulmonary segments (posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes), at times associated with a pleural effusion or infiltrate. The most common appearance of a lung abscess is an asymmetric cavity with an air-fluid level and a wall with a ragged or smooth border. CT scan is often indicated when X-rays are equivocal and when cases are of uncertain cause or are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Bronchoscopy is reserved for patients with an immunocompromising condition, atypical presentation, or lack of response to treatment.

For those cavitary lesions in which there is a high degree of suspicion for lung abscess, empiric treatment should include antibiotics active against anaerobes and MRSA if the patient has risk factors. Patients often receive an empiric trial of antibiotics prior to biopsy unless there are clear indications that the cavitary lung lesion is related to cancer. Lung abscesses typically drain spontaneously, and transthoracic or endobronchial drainage is not usually recommended as initial management due to risk of pneumothorax and formation of bronchopleural fistula.

Lung abscesses should be followed to resolution with serial chest imaging. If the lung abscess does not resolve, it would be appropriate to consult thoracic surgery, interventional radiology, or pulmonary, depending on the location of the abscess and the local expertise with transthoracic or endobronchial drainage and surgical resection.

Septic emboli. Septic emboli are a less common cause of cavitary lung lesions. This entity should be considered in patients with a history of IV drug use or infected indwelling devices (central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and right-sided prosthetic heart valves). Physical examination should include an assessment for signs of endocarditis and inspection for infected indwelling devices. In patients with IV drug use, the likely pathogen is S. aureus.

Oropharyngeal infection or indwelling catheters may predispose patients to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, also known as Lemierre’s syndrome, a rare but important cause of septic emboli.5 Laboratory testing includes culture for sputum and blood and culture of the infected device if applicable. On chest X-ray, septic emboli commonly appear as nodules located in the lung periphery. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting cavitation associated with septic emboli.

Diagnosis of Noninfectious Causes

Upon identification of a cavitary lung lesion, noninfectious etiologies must also be entertained. Noninfectious etiologies include malignancy, rheumatologic diseases, pulmonary embolism, and other causes. Important components in the clinical presentation include the presence of constitutional symptoms (fevers, weight loss, night sweats), smoking history, family history, and an otherwise complete review of systems. Physical exam should include evaluation for lymphadenopathy, cachexia, rash, clubbing, and other symptoms pertinent to the suspected etiology.

Malignancy. Perhaps most important among noninfectious causes of cavitary lung lesions is malignancy, and a high index of suspicion is warranted given that it is commonly the first diagnosis to consider overall.2 Cavities can form in primary lung cancers (e.g. bronchogenic carcinomas), lung tumors such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma, or in metastatic disease. Cavitation has been detected in 7%-11% of primary lung cancers by plain radiography and in 22% by computed tomography.5 Cancers of squamous cell origin are the most likely to cavitate; this holds true for both primary lung tumors and metastatic tumors.6 Additionally, cavitation portends a worse prognosis.7

Clinicians should review any available prior chest imaging studies to look for a change in the quality or size of a cavitary lung lesion. Neoplasms are typically of variable size with irregular thick walls (greater than 4 mm) on CT scan, with higher specificity for neoplasm in those with a wall thickness greater than 15 mm.2

When the diagnosis is less clear, the decision to embark on more advanced diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, should rest on the provider’s clinical suspicion for a certain disease process. When a lung cancer is suspected, consultation with pulmonary and interventional radiology should be obtained to determine the best approach for biopsy.

Rheumatologic. Less common causes of cavitary lesions include those related to rheumatologic diseases (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). One study demonstrated that cavitary lung nodules occur in 37% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.8

Although uncommon, cavitary nodules can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis. Given that patients with rheumatologic diseases are often treated with immunosuppressive agents, infection must remain high on the differential. Suspicion of a rheumatologic cause should prompt the clinician to obtain appropriate serologic testing and consultation as needed.

Pulmonary embolism. Although often not considered in the evaluation of cavitary lung lesions, pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to infarction and the formation of a cavitary lesion. Pulmonary infarction has been reported to occur in as many as one third of cases of PE.9 Cavitary lesions also have been described in chronic thromboembolic disease.10

Other. Uncommon causes of cavitary lesions include bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis, among others. The hospitalist should keep a broad differential and involve consultants if the diagnosis remains unclear after initial diagnostic evaluation.

Back to the Case

The patient’s fever and productive cough, in combination with recent travel and location of the cavitary lesion, increase his risk for tuberculosis and endemic fungi, such as Coccidioides. This patient was placed on respiratory isolation with AFBs obtained to rule out TB, with Coccidioides antibodies, Cyptococcal antigen titers, and sputum for fungus sent to evaluate for an endemic fungus. He had a chest CT, which revealed a 17-mm cavitary mass within the right upper lobe that contained an air-fluid level indicating lung abscess. Coccidioides, cryptococcal, fungal sputum, and TB studies were negative.

The patient was treated empirically with clindamycin given the high prevalence of anaerobes in lung abscess. He was followed as an outpatient and had a chest X-ray showing resolution of the lesion at six months. The purpose of the X-ray was two-fold: to monitor the effect of antibiotic treatment and to evaluate for persistence of the cavitation given the neoplastic risk factors of older age and smoking.

Bottom Line

The best approach to a patient with a cavitary lung lesion includes assessing the clinical presentation and risk factors, differentiating infectious from noninfectious causes, and then utilizing this information to further direct the diagnostic evaluation. Consultation with a subspecialist or further testing such as biopsy should be considered if the etiology remains undefined after the initial evaluation.

Drs. Rendon, Pizanis, Montanaro, and Kraai are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-752.

- Barnes PF, Verdegem TD, Vachon LA, Leedom JM, Overturf GD. Chest roentgenogram in pulmonary tuberculosis. New data on an old test. Chest. 1988;94(2):316-320.

- Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2012;21(3):217-221. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b.

- Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):305-333.

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5(6):523-530.

- Kolodziejski LS, Dyczek S, Duda K, Góralczyk J, Wysocki WM, Lobaziewicz W. Cavitated tumor as a clinical subentity in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50(1):66-73.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97(4):906-912.

- He H, Stein MW, Zalta B, Haramati LB. Pulmonary infarction: spectrum of findings on multidetector helical CT. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21(1):1-7.

- Harris H, Barraclough R, Davies C, Armstrong I, Kiely DG, van Beek E Jr. Cavitating lung lesions in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(3):11-21.

- Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(6):1269-1271.

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Imaging may reveal a cavitary lesion in the dependent pulmonary segments (posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes), at times associated with a pleural effusion or infiltrate. The most common appearance of a lung abscess is an asymmetric cavity with an air-fluid level and a wall with a ragged or smooth border. CT scan is often indicated when X-rays are equivocal and when cases are of uncertain cause or are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Bronchoscopy is reserved for patients with an immunocompromising condition, atypical presentation, or lack of response to treatment.

For those cavitary lesions in which there is a high degree of suspicion for lung abscess, empiric treatment should include antibiotics active against anaerobes and MRSA if the patient has risk factors. Patients often receive an empiric trial of antibiotics prior to biopsy unless there are clear indications that the cavitary lung lesion is related to cancer. Lung abscesses typically drain spontaneously, and transthoracic or endobronchial drainage is not usually recommended as initial management due to risk of pneumothorax and formation of bronchopleural fistula.

Lung abscesses should be followed to resolution with serial chest imaging. If the lung abscess does not resolve, it would be appropriate to consult thoracic surgery, interventional radiology, or pulmonary, depending on the location of the abscess and the local expertise with transthoracic or endobronchial drainage and surgical resection.

Septic emboli. Septic emboli are a less common cause of cavitary lung lesions. This entity should be considered in patients with a history of IV drug use or infected indwelling devices (central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and right-sided prosthetic heart valves). Physical examination should include an assessment for signs of endocarditis and inspection for infected indwelling devices. In patients with IV drug use, the likely pathogen is S. aureus.

Oropharyngeal infection or indwelling catheters may predispose patients to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, also known as Lemierre’s syndrome, a rare but important cause of septic emboli.5 Laboratory testing includes culture for sputum and blood and culture of the infected device if applicable. On chest X-ray, septic emboli commonly appear as nodules located in the lung periphery. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting cavitation associated with septic emboli.

Diagnosis of Noninfectious Causes

Upon identification of a cavitary lung lesion, noninfectious etiologies must also be entertained. Noninfectious etiologies include malignancy, rheumatologic diseases, pulmonary embolism, and other causes. Important components in the clinical presentation include the presence of constitutional symptoms (fevers, weight loss, night sweats), smoking history, family history, and an otherwise complete review of systems. Physical exam should include evaluation for lymphadenopathy, cachexia, rash, clubbing, and other symptoms pertinent to the suspected etiology.

Malignancy. Perhaps most important among noninfectious causes of cavitary lung lesions is malignancy, and a high index of suspicion is warranted given that it is commonly the first diagnosis to consider overall.2 Cavities can form in primary lung cancers (e.g. bronchogenic carcinomas), lung tumors such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma, or in metastatic disease. Cavitation has been detected in 7%-11% of primary lung cancers by plain radiography and in 22% by computed tomography.5 Cancers of squamous cell origin are the most likely to cavitate; this holds true for both primary lung tumors and metastatic tumors.6 Additionally, cavitation portends a worse prognosis.7

Clinicians should review any available prior chest imaging studies to look for a change in the quality or size of a cavitary lung lesion. Neoplasms are typically of variable size with irregular thick walls (greater than 4 mm) on CT scan, with higher specificity for neoplasm in those with a wall thickness greater than 15 mm.2

When the diagnosis is less clear, the decision to embark on more advanced diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, should rest on the provider’s clinical suspicion for a certain disease process. When a lung cancer is suspected, consultation with pulmonary and interventional radiology should be obtained to determine the best approach for biopsy.

Rheumatologic. Less common causes of cavitary lesions include those related to rheumatologic diseases (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). One study demonstrated that cavitary lung nodules occur in 37% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.8

Although uncommon, cavitary nodules can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis. Given that patients with rheumatologic diseases are often treated with immunosuppressive agents, infection must remain high on the differential. Suspicion of a rheumatologic cause should prompt the clinician to obtain appropriate serologic testing and consultation as needed.

Pulmonary embolism. Although often not considered in the evaluation of cavitary lung lesions, pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to infarction and the formation of a cavitary lesion. Pulmonary infarction has been reported to occur in as many as one third of cases of PE.9 Cavitary lesions also have been described in chronic thromboembolic disease.10

Other. Uncommon causes of cavitary lesions include bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis, among others. The hospitalist should keep a broad differential and involve consultants if the diagnosis remains unclear after initial diagnostic evaluation.

Back to the Case

The patient’s fever and productive cough, in combination with recent travel and location of the cavitary lesion, increase his risk for tuberculosis and endemic fungi, such as Coccidioides. This patient was placed on respiratory isolation with AFBs obtained to rule out TB, with Coccidioides antibodies, Cyptococcal antigen titers, and sputum for fungus sent to evaluate for an endemic fungus. He had a chest CT, which revealed a 17-mm cavitary mass within the right upper lobe that contained an air-fluid level indicating lung abscess. Coccidioides, cryptococcal, fungal sputum, and TB studies were negative.

The patient was treated empirically with clindamycin given the high prevalence of anaerobes in lung abscess. He was followed as an outpatient and had a chest X-ray showing resolution of the lesion at six months. The purpose of the X-ray was two-fold: to monitor the effect of antibiotic treatment and to evaluate for persistence of the cavitation given the neoplastic risk factors of older age and smoking.

Bottom Line

The best approach to a patient with a cavitary lung lesion includes assessing the clinical presentation and risk factors, differentiating infectious from noninfectious causes, and then utilizing this information to further direct the diagnostic evaluation. Consultation with a subspecialist or further testing such as biopsy should be considered if the etiology remains undefined after the initial evaluation.

Drs. Rendon, Pizanis, Montanaro, and Kraai are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-752.

- Barnes PF, Verdegem TD, Vachon LA, Leedom JM, Overturf GD. Chest roentgenogram in pulmonary tuberculosis. New data on an old test. Chest. 1988;94(2):316-320.

- Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2012;21(3):217-221. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b.

- Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):305-333.

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5(6):523-530.

- Kolodziejski LS, Dyczek S, Duda K, Góralczyk J, Wysocki WM, Lobaziewicz W. Cavitated tumor as a clinical subentity in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50(1):66-73.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97(4):906-912.

- He H, Stein MW, Zalta B, Haramati LB. Pulmonary infarction: spectrum of findings on multidetector helical CT. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21(1):1-7.

- Harris H, Barraclough R, Davies C, Armstrong I, Kiely DG, van Beek E Jr. Cavitating lung lesions in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(3):11-21.

- Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(6):1269-1271.

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3