User login

Let’s Dance: A Holistic Approach to Treating Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

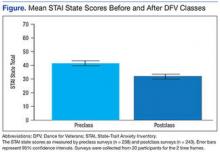

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

Shared Medical Appointments for Glycemic Management in Rural Veterans

In 2005, the VA mandated shared medical appointments (SMAs) to improve clinic efficiency and quality of care. Both local and national Advanced Clinic Access meetings endorsed this method for decreasing wait times, improving patient outcome measures, and minimizing cost. Additionally, SMAs offer an opportunity to use nonphysician providers to their fullest potential. The VA has recognized the important role nonphysicians play in improving care for patients, especially patients with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus (DM).1

Based on the chronic care model, SMAs are patient medical appointments in which a multidisciplinary/multiexpertise team of providers sees a group of 8 to 20 patients in a 1.5- to 2-hour visit. Chronic illnesses, such as DM, are right for this approach.1

Diabetes mellitus is the leading cause of kidney failure, nontraumatic lower-limb amputations, and new cases of blindness among adults. It also is a major cause of heart disease and stroke, and the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. The total cost of diagnosed DM in the U.S. in 2012 was $245 billion compared with $174 billion in 2007.2 Direct medical costs accounted for $176 billion, and $69 billion accounted for indirect costs, such as disability, work loss, and premature mortality.2 After adjusting for population age and sex differences, the average medical expenses among people diagnosed with DM were 2.3 times higher than medical expenses for those without DM. This figure does not include the cost of undiagnosed diabetes, prediabetes, or gestational diabetes.2

The purpose of this quality improvement study is to describe the results of SMA for management of DM conducted largely among rural veterans. The effectiveness of DM SMAs has been documented in several previous studies.3-10 However, this study focuses on using SMAs to manage veterans with DM in a rural environment.

Methods

The authors used the Primary Care Almanac (PCA) of the VHA Support Service Center to identify potential study participants at Lake City VAMC in Florida. The PCA is a database of VA primary care patients. The authors identified patients with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level > 9% through the DM Cohort Reports Menu. Veterans with behavioral issues and those with high no-show rates were excluded.

The clinic staff called the eligible participants, educated them about SMA, and asked whether they would be interested in attending a DM SMA. If interested, they were scheduled for the next SMA. If uninterested, they were offered DM home telehealth follow-up, an appointment with the DM pharmacist, an appointment with the dietitian, enrollment into a DM education class, or routine follow-up with their primary care provider (PCP). Using this method, 18 patients were scheduled for the DM SMA between November 2010 and April 2013.

SMA Procedures

A physician or advanced registered nurse practitioner (ARNP) led each appointment, and in most cases other staff attended, including a clinical pharmacist, physical therapist (PT), kinesiotherapist (KT), dietician, social worker, registered nurse (RN), patient educator, and mental health provider. A pharmacist and RN attended all SMA appointments. The basic format consisted of a 90-minute appointment and included an abbreviated, clothed physical exam, which included vital signs; auscultation of heart, lungs, and abdomen; and foot exam. If a veteran had not received an eye exam within the year, an eye clinic consult was ordered. There were 10- to 30-minute blocks of time for the support staff who attended. The physician or ARNP usually led the appointment, and in addition to speaking to the group and discussing a daily topic, also spoke one-on-one with each veteran while support staff spoke to other group members.

During the appointment, the pharmacist answered questions and reviewed and adjusted medications as needed. The RN educator acted as a transcriptionist and answered questions. The PT/KT led interactive exercises. The dietitian answered questions, gave out educational materials, and did cooking demonstrations. The psychologist discussed behavioral health goals and asked each veteran to set a health goal to evaluate at the next meeting. The nursing staff in the primary care clinic checked in the patients. One nurse checked-in 1 to 2 patients and gave the patient a medication list.

Appointments were held every 2 to 3 months. All veterans attending were invited to come to the next appointment, and new patients were enrolled throughout the study. The new veterans were invited based on HbA1c readings pulled from the PCA database.

Hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure (BP), weight, and lipid level data were collected. Participation ended when HbA1c improved to < 8%, a patient was no longer interested, or after the patient did not show up for an appointment and did not call to cancel.

Results

Eighteen patients met the inclusion criteria (Table). Participants mean age was 62 years with most aged 50 to 70 years. Most participants were male (94%) and white (61%). Thirty-nine percent of the participants were African American. Twelve group appointments were held from November 2010 through April 2013. The mean enrollment per session was 5.8 patients (range 3-9). The median number of sessions each patient participated in was 3 (range 1 to 10).

SMA Outcomes

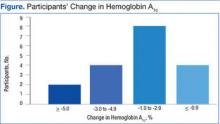

Among the 18 participants, the absolute change in HbA1c was -2.2% ± 2.0, representing a relative decrease in HbA1c of 18.2%. The study criterion for success was either a relative decrease of HbA1c by 13.5% or an absolute decrease in HbA1c of 1.5%. Of 18 patients participating in SMA, 14 (78%) patients achieved this goal. Of the 4 patients that were not successful, 2 patients had a relative HbA1c increase of 13% and 14%, respectively, 1 patient had no change at all, and 1 patient had a 9% relative decrease (Figure). Fourteen patients had improvement in their HbA1c after the first appointment, 2 patients had improvement after the second appointment, 1 patient had improvement after the fourth appointment, and 1 patient had no improvement.

In this population of rural veterans with poorly controlled diabetes, participation in SMAs was associated with marked improvement in measures of glucose control. Fourteen of the 18 (78%) veterans who participated in the DM SMA exhibited clinically significant decreases in HbA1c and achieved the defined goal.

Discussion

The effectiveness of DM SMAs has been documented in several previous studies. Sadur and colleagues found that a 6-month cluster visit group model of care for adults with DM improved glycemic control by 1.3% in the intervention subjects vs 0.2% in the control subjects in a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) with 185 participants.3 The intervention group received multidisciplinary outpatient diabetes management delivered by a diabetes nurse educator, a psychologist, a nutritionist, and a pharmacist in cluster visit settings of 10 to 18 patients per month for 6 months.

Metabolic Control

In another RCT trial of 112 patients, Trento and colleagues found that physician-led group consultations may improve metabolic control in the medium term by inducing more appropriate health behaviors.4 The consultations are feasible in everyday clinical practice without increasing working hours. After 2 years, HbA1c levels remained stable in patients seen in groups but had worsened in control subjects.

In a quasi-experiment with concurrent but nonrandomized controls, Kirsh and colleagues concluded that SMAs for DM constitute a practical system redesign that may help improve quality of care.5 Participants included 44 veterans from a VA primary care clinic who attended at least 1 physician-led SMA from April 2005 to September 2005 and from May 2006 to August 2006. Results showed levels of HbA1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and systolic BP (SBP) fell significantly postintervention with a mean decrease of HbA1c 1.4%, LDL-C 14.8 mg/dL, and SBP 16.0 mm Hg. The reductions in HbA1c and SBP were greater in the intervention group relative to the control group. The LDL-C reduction also was greater in the intervention group; however, the difference was not statistically significant.

Similarly, Sanchez concluded that patients who participated in a physician and nurse practitioner-led SMA using the diabetes self-management education (DSME) process had improvements in their HbA1c, self-management skills, and satisfaction.6 The study was considered a quality improvement project. Data were collected on 70 patients who were 96% Mexican American and received DSME via SMA during a 3-month span. The average HbA1c on visit 1 was 7.95%, 7.48% on visit 2, and 7.51% on visit 3. There were 34 patients with a decrease in HbA1c on visit 2 and 12 patients with a decrease in HbA1c on visit 3. Also, in a study on the effectiveness of SMAs in DM care, Guirguis and colleagues found that veterans showed an average decline in HbA1c whether they attended 1, 2, 3, or 4 SMAs.7 However, the decline was only statistically significant (P = .02) for those who had a baseline HbA1c > 9% prior to the study.

In contrast, other studies found no significant difference in improvement of DM patients in a SMA vs DM patients not in a SMA. Wagner and colleagues found periodic primary care sessions organized to meet the complex needs of diabetic patients improved the process of diabetes care and were associated with better outcomes.11 Primary care practices with a total of 700 patients were randomized within clinics to either a chronic care clinic (intervention) group or a usual care (control) group. Each chronic care clinic consisted of an assessment; individual visits with the primary care physician, nurse, and clinical pharmacist; and a group educational/peer support session. Although they found that the primary care group sessions improved the process of DM care and were associated with better outcomes, the mean HbA1c levels and cholesterol levels were comparable between the 2 groups.

In a 12-month RCT of 186 diabetic patients, Clancy and colleagues concluded physician and RN co-led group visits can improve the quality of care for diabetic patients, but modifications to the content and style of group visits may be necessary to achieve improved clinical outcomes.12 Results showed at both measurement points, HbA1c, BP, and lipid levels did not differ significantly for patients attending group visits vs those in usual care. Similarly, Edelman and colleaguesfound that provider-run group medical appointments are a potent strategy for improving BP but not HbA1c levels in DM patients in a RCT that compared a group medical appointment intervention with usual care among 239 primary care diabetic patients at the Durham VAMC in North Carolina and Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia.10 Of note, the HbA1c levels in the group medical clinics did improve from 9.2% at baseline to a final of 8.3%, whereas the HbA1c level in the usual care group only improved from 9.2 to 8.6%.

Pharmacist-Led SMAs

In comparison to physician or nurse practitioner-led SMA, there also have been studies regarding pharmacist-led group medical appointments that have shown to be beneficial. Taveira and colleagues found that pharmacist-led group medical visits were feasible and efficacious for improving cardiac risk factors in patients with DM.8 This RCT with 118 VA patient participants showed a greater proportion of the intervention group vs the usual care alone group achieved a HbA1c of < 7%, and a SBP < 130 mm Hg.

In a separate study, Taveira and colleagues found that pharmacist-led group SMA visits are effective for glycemic control in patients with DM and depression without a change in depression symptoms.9 This RCT compared standard care and VA Multidisciplinary Education in Diabetes and Intervention for Cardiac Risk Reduction in Depression vs standard care alone in 88 depressed patients with DM with HbA1c > 6.5%. Also, Cohen and colleagues concluded that pharmacist-led group intervention program was an effective and sustainable collaborative care approach to managing DM and reducing associated cardiovascular risks.10 This study was a RCT that compared standard primary care alone to a 6-month pharmacist-led SMA program added to standard primary care. A total of 99 VA patients were included in the final analysis.