User login

The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine – 2017 revision

“You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” This famous quote from Mahatma Gandhi has inspired many to transform their work and personal space into an eternal quest for improvement. We hospitalists are now well-recognized agents of change in our work environment, improving the quality and safety of inpatient care, striving to create increased value, and promoting the delivery of cost-effective care.

Much has changed in the U.S. health care and hospital practice environment over the past decade. The 2017 revision of the Core Competencies seeks to maintain its relevance, value and more importantly, highlight areas for future growth and innovation.

What does the “Core Competencies” represent and who should use it?

It comprises a set of competency-based learning objectives that present a shared understanding of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected of physicians practicing hospital medicine in the United States.

A common misconception is that every hospitalist can be expected to demonstrate proficiency in all topics in the Core Competencies. While every item in the compendium is highly relevant to the field as a whole, its significance for individual hospitalists will vary depending on their practice pattern, leadership role, and local culture.

It also is noteworthy to indicate that it is not a set of practice guidelines that provide recommendations based on the latest scientific evidence, nor does it represent any legal standard of care. Rather, the Core Competencies offers an agenda for curricular training and to broadly influence the direction of the field. It also is important to realize that the Core Competencies is not an all-inclusive list that restricts a hospitalist’s scope of practice. Instead, hospitalists should use the Core Competencies as an educational and professional benchmark with the ultimate goal of providing safe, efficient, and high-value care using interdisciplinary collaboration when necessary.

As a core set of attributes, all hospitalists can use it to reflect on their knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as those of their group or practice collectively. The Core Competencies highlights areas within the field that are prime for further research and quality improvement initiatives on a national, regional, and local level. Thus, they also should be of interest to health care administrators and a variety of stakeholders looking to support and fund such efforts in enhancing health care value and quality for all.

It is also a framework for the development of curricula for both education and professional development purposes for use by hospitalists, hospital medicine programs, and health care institutions. Course Directors of Continuing Medical Education programs can use the Core Competencies to identify learning objectives that fulfill the goal of the educational program. Similarly, residency and fellowship program directors and medical school clerkship directors can use it to develop course syllabi targeted to the needs of their learner groups.

The structure and format of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine

The 53 chapters in the 2017 revision are divided into three sections – Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems, all integral to the practice of hospital medicine. Each chapter starts with an introductory paragraph that discusses the relevance and importance of the subject. Each competency-based learning objective describes a particular concept coupled with an action verb that specifies an expected level of proficiency.

For example, the action verb “explain” that requires a mere description of a subject denotes a lower competency level, compared with the verb “evaluate,” which implies not only an understanding of the matter but also the ability to assess its value for a particular purpose. These learning objectives are further categorized into knowledge, skills, and attitudes subsections to reflect the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains of learning.

Because hospitalists are the experts in complex hospital systems, the clinical and procedural sections have an additional subsection, “System Organization and Improvement.” The objectives in this paragraph emphasize the critical role that hospitalists can play as leaders of multidisciplinary teams to improve the quality of care of all patients with a similar condition or undergoing the same procedure.

Examples of everyday use of the Core Competencies for practicing hospitalists

A hospitalist looking to improve her performance of bedside thoracentesis reviews the chapter on Thoracentesis. She then decides to enhance her skills by attending an educational workshop on the use of point-of-care ultrasonography.

A hospital medicine group interested in improving the rate of common hospital-acquired infections reviews the Urinary Tract Infection, Hospital-Acquired and Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia, and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance chapters to identify possible gaps in practice patterns. The group also goes through the chapters on Quality Improvement, Practice-based Learning and Improvement, and Hospitalist as Educator, to further reflect upon the characteristics of their practice environment. The group then adopts a separate strategy to address identified gaps by finding suitable evidence-based content in a format that best fits their need.

An attending physician leading a team of medical residents and students reviews the chapter on Syncope to identify the teaching objectives for each learner. He decides that the medical student should be able to “define syncope” and “explain the physiologic mechanisms that lead to reflex or neurally mediated syncope.” He determines that the intern on the team should be able to “differentiate syncope from other causes of loss of consciousness,” and the senior resident should be able to “formulate a logical diagnostic plan to determine the cause of syncope while avoiding rarely indicated diagnostic tests … ”

New chapters in the 2017 revision

SHM’s Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) considered several topics as potential new chapters for the 2017 Revision. The SHM Education Committee judged each for its value as a “core” subject by its relevance, intersection with other specialties, and its scope as a stand-alone chapter.

There are two new clinical conditions – hyponatremia and syncope – mainly chosen because of their clinical importance, the risk of complications, and management inconsistencies that offer hospitalists great opportunities for quality improvement initiatives. The CCTF also identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as a notable advancement in the field. A separate task force is working to evaluate best practices and develop a practice guideline that hospitalists can use. The CCTF expects to add more chapters as the field of hospital medicine continues to advance and transform the delivery of health care globally.

The 2017 Revision of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine is located online at www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com or using the URL shortener bit.ly/corecomp17.

Dr. Nichani is assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the division of hospital medicine at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He serves as the chair of the SHM Education Committee.

“You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” This famous quote from Mahatma Gandhi has inspired many to transform their work and personal space into an eternal quest for improvement. We hospitalists are now well-recognized agents of change in our work environment, improving the quality and safety of inpatient care, striving to create increased value, and promoting the delivery of cost-effective care.

Much has changed in the U.S. health care and hospital practice environment over the past decade. The 2017 revision of the Core Competencies seeks to maintain its relevance, value and more importantly, highlight areas for future growth and innovation.

What does the “Core Competencies” represent and who should use it?

It comprises a set of competency-based learning objectives that present a shared understanding of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected of physicians practicing hospital medicine in the United States.

A common misconception is that every hospitalist can be expected to demonstrate proficiency in all topics in the Core Competencies. While every item in the compendium is highly relevant to the field as a whole, its significance for individual hospitalists will vary depending on their practice pattern, leadership role, and local culture.

It also is noteworthy to indicate that it is not a set of practice guidelines that provide recommendations based on the latest scientific evidence, nor does it represent any legal standard of care. Rather, the Core Competencies offers an agenda for curricular training and to broadly influence the direction of the field. It also is important to realize that the Core Competencies is not an all-inclusive list that restricts a hospitalist’s scope of practice. Instead, hospitalists should use the Core Competencies as an educational and professional benchmark with the ultimate goal of providing safe, efficient, and high-value care using interdisciplinary collaboration when necessary.

As a core set of attributes, all hospitalists can use it to reflect on their knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as those of their group or practice collectively. The Core Competencies highlights areas within the field that are prime for further research and quality improvement initiatives on a national, regional, and local level. Thus, they also should be of interest to health care administrators and a variety of stakeholders looking to support and fund such efforts in enhancing health care value and quality for all.

It is also a framework for the development of curricula for both education and professional development purposes for use by hospitalists, hospital medicine programs, and health care institutions. Course Directors of Continuing Medical Education programs can use the Core Competencies to identify learning objectives that fulfill the goal of the educational program. Similarly, residency and fellowship program directors and medical school clerkship directors can use it to develop course syllabi targeted to the needs of their learner groups.

The structure and format of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine

The 53 chapters in the 2017 revision are divided into three sections – Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems, all integral to the practice of hospital medicine. Each chapter starts with an introductory paragraph that discusses the relevance and importance of the subject. Each competency-based learning objective describes a particular concept coupled with an action verb that specifies an expected level of proficiency.

For example, the action verb “explain” that requires a mere description of a subject denotes a lower competency level, compared with the verb “evaluate,” which implies not only an understanding of the matter but also the ability to assess its value for a particular purpose. These learning objectives are further categorized into knowledge, skills, and attitudes subsections to reflect the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains of learning.

Because hospitalists are the experts in complex hospital systems, the clinical and procedural sections have an additional subsection, “System Organization and Improvement.” The objectives in this paragraph emphasize the critical role that hospitalists can play as leaders of multidisciplinary teams to improve the quality of care of all patients with a similar condition or undergoing the same procedure.

Examples of everyday use of the Core Competencies for practicing hospitalists

A hospitalist looking to improve her performance of bedside thoracentesis reviews the chapter on Thoracentesis. She then decides to enhance her skills by attending an educational workshop on the use of point-of-care ultrasonography.

A hospital medicine group interested in improving the rate of common hospital-acquired infections reviews the Urinary Tract Infection, Hospital-Acquired and Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia, and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance chapters to identify possible gaps in practice patterns. The group also goes through the chapters on Quality Improvement, Practice-based Learning and Improvement, and Hospitalist as Educator, to further reflect upon the characteristics of their practice environment. The group then adopts a separate strategy to address identified gaps by finding suitable evidence-based content in a format that best fits their need.

An attending physician leading a team of medical residents and students reviews the chapter on Syncope to identify the teaching objectives for each learner. He decides that the medical student should be able to “define syncope” and “explain the physiologic mechanisms that lead to reflex or neurally mediated syncope.” He determines that the intern on the team should be able to “differentiate syncope from other causes of loss of consciousness,” and the senior resident should be able to “formulate a logical diagnostic plan to determine the cause of syncope while avoiding rarely indicated diagnostic tests … ”

New chapters in the 2017 revision

SHM’s Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) considered several topics as potential new chapters for the 2017 Revision. The SHM Education Committee judged each for its value as a “core” subject by its relevance, intersection with other specialties, and its scope as a stand-alone chapter.

There are two new clinical conditions – hyponatremia and syncope – mainly chosen because of their clinical importance, the risk of complications, and management inconsistencies that offer hospitalists great opportunities for quality improvement initiatives. The CCTF also identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as a notable advancement in the field. A separate task force is working to evaluate best practices and develop a practice guideline that hospitalists can use. The CCTF expects to add more chapters as the field of hospital medicine continues to advance and transform the delivery of health care globally.

The 2017 Revision of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine is located online at www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com or using the URL shortener bit.ly/corecomp17.

Dr. Nichani is assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the division of hospital medicine at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He serves as the chair of the SHM Education Committee.

“You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” This famous quote from Mahatma Gandhi has inspired many to transform their work and personal space into an eternal quest for improvement. We hospitalists are now well-recognized agents of change in our work environment, improving the quality and safety of inpatient care, striving to create increased value, and promoting the delivery of cost-effective care.

Much has changed in the U.S. health care and hospital practice environment over the past decade. The 2017 revision of the Core Competencies seeks to maintain its relevance, value and more importantly, highlight areas for future growth and innovation.

What does the “Core Competencies” represent and who should use it?

It comprises a set of competency-based learning objectives that present a shared understanding of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected of physicians practicing hospital medicine in the United States.

A common misconception is that every hospitalist can be expected to demonstrate proficiency in all topics in the Core Competencies. While every item in the compendium is highly relevant to the field as a whole, its significance for individual hospitalists will vary depending on their practice pattern, leadership role, and local culture.

It also is noteworthy to indicate that it is not a set of practice guidelines that provide recommendations based on the latest scientific evidence, nor does it represent any legal standard of care. Rather, the Core Competencies offers an agenda for curricular training and to broadly influence the direction of the field. It also is important to realize that the Core Competencies is not an all-inclusive list that restricts a hospitalist’s scope of practice. Instead, hospitalists should use the Core Competencies as an educational and professional benchmark with the ultimate goal of providing safe, efficient, and high-value care using interdisciplinary collaboration when necessary.

As a core set of attributes, all hospitalists can use it to reflect on their knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as those of their group or practice collectively. The Core Competencies highlights areas within the field that are prime for further research and quality improvement initiatives on a national, regional, and local level. Thus, they also should be of interest to health care administrators and a variety of stakeholders looking to support and fund such efforts in enhancing health care value and quality for all.

It is also a framework for the development of curricula for both education and professional development purposes for use by hospitalists, hospital medicine programs, and health care institutions. Course Directors of Continuing Medical Education programs can use the Core Competencies to identify learning objectives that fulfill the goal of the educational program. Similarly, residency and fellowship program directors and medical school clerkship directors can use it to develop course syllabi targeted to the needs of their learner groups.

The structure and format of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine

The 53 chapters in the 2017 revision are divided into three sections – Clinical Conditions, Procedures, and Healthcare Systems, all integral to the practice of hospital medicine. Each chapter starts with an introductory paragraph that discusses the relevance and importance of the subject. Each competency-based learning objective describes a particular concept coupled with an action verb that specifies an expected level of proficiency.

For example, the action verb “explain” that requires a mere description of a subject denotes a lower competency level, compared with the verb “evaluate,” which implies not only an understanding of the matter but also the ability to assess its value for a particular purpose. These learning objectives are further categorized into knowledge, skills, and attitudes subsections to reflect the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains of learning.

Because hospitalists are the experts in complex hospital systems, the clinical and procedural sections have an additional subsection, “System Organization and Improvement.” The objectives in this paragraph emphasize the critical role that hospitalists can play as leaders of multidisciplinary teams to improve the quality of care of all patients with a similar condition or undergoing the same procedure.

Examples of everyday use of the Core Competencies for practicing hospitalists

A hospitalist looking to improve her performance of bedside thoracentesis reviews the chapter on Thoracentesis. She then decides to enhance her skills by attending an educational workshop on the use of point-of-care ultrasonography.

A hospital medicine group interested in improving the rate of common hospital-acquired infections reviews the Urinary Tract Infection, Hospital-Acquired and Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia, and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance chapters to identify possible gaps in practice patterns. The group also goes through the chapters on Quality Improvement, Practice-based Learning and Improvement, and Hospitalist as Educator, to further reflect upon the characteristics of their practice environment. The group then adopts a separate strategy to address identified gaps by finding suitable evidence-based content in a format that best fits their need.

An attending physician leading a team of medical residents and students reviews the chapter on Syncope to identify the teaching objectives for each learner. He decides that the medical student should be able to “define syncope” and “explain the physiologic mechanisms that lead to reflex or neurally mediated syncope.” He determines that the intern on the team should be able to “differentiate syncope from other causes of loss of consciousness,” and the senior resident should be able to “formulate a logical diagnostic plan to determine the cause of syncope while avoiding rarely indicated diagnostic tests … ”

New chapters in the 2017 revision

SHM’s Core Competencies Task Force (CCTF) considered several topics as potential new chapters for the 2017 Revision. The SHM Education Committee judged each for its value as a “core” subject by its relevance, intersection with other specialties, and its scope as a stand-alone chapter.

There are two new clinical conditions – hyponatremia and syncope – mainly chosen because of their clinical importance, the risk of complications, and management inconsistencies that offer hospitalists great opportunities for quality improvement initiatives. The CCTF also identified the use of point-of-care ultrasonography as a notable advancement in the field. A separate task force is working to evaluate best practices and develop a practice guideline that hospitalists can use. The CCTF expects to add more chapters as the field of hospital medicine continues to advance and transform the delivery of health care globally.

The 2017 Revision of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine is located online at www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com or using the URL shortener bit.ly/corecomp17.

Dr. Nichani is assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the division of hospital medicine at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He serves as the chair of the SHM Education Committee.

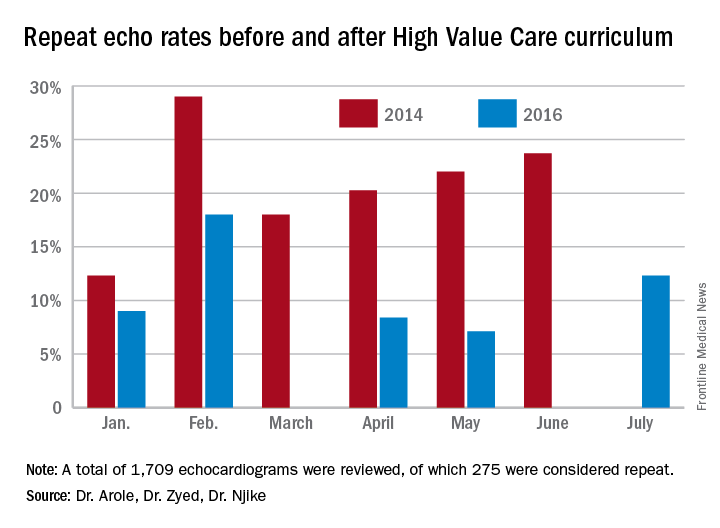

High Value Care curriculum reduced echocardiogram ordering

Study Title

The impact of a High Value Care curriculum on rate of repeat of trans-thoracic echocardiogram ordering among medical residents

Background

There is little data to confirm the impact of a High Value Care curriculum on echocardiogram ordering practices in a residency training program. We sought to evaluate the rate of performance of repeat transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) before and after implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum.

Methods

A High Value Care curriculum was developed for the medical residents at Griffin Hospital, a community hospital, in 2015. The curriculum included a series of lectures aimed at promoting cost-conscious care while maintaining high quality. It also involved house staff in different quality improvement (QI) projects aimed at promoting high value care.

A group of residents decided to work on an initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms. Repeat echocardiograms were defined as those performed within 6 months of a previous echocardiogram on the same patient. Only results in our EHR reflecting in-patient echocardiograms were utilized.

We retrospectively examined the rates of repeat echocardiograms performed in a 6 month period in 2014 before the High Vale Care curriculum was initiated. We assessed data from a 5 month period in 2016 to determine the rate of repeat electrocardiograms ordered at our institution.

Results

A total of 1,709 echocardiograms were reviewed in both time periods. Of these, 275 were considered repeat. At baseline, or before the implementation of a High Value Care curriculum, we examined 908 echocardiograms that were ordered, of which 21% were repeats.

After the implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum, 801 echocardiograms were ordered. Only 11% of these were repeats. This corresponds to a 52% reduction in the rate of repeated ordering of echocardiograms.

Discussion

The significant improvement in the rate of repeat echocardiograms was noted without any initiative directed specifically at echocardiogram ordering practices. During the planning phases of the proposed QI initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms, house staff noted that their colleagues were already being more selective in their echocardiogram ordering practices because of the impact of the-cost conscious care lectures they had attended, as well as hospital-wide attention on the first resident-driven QI initiative that was aimed at reducing repetitive daily labs.

As part of the reducing repetitive labs QI, house staff had to provide clear rationale for why they were ordering daily labs. The received regular updates about their lab ordering practices and direct feedback if they consistently did not provide clear rationale for ordering daily labs.

Conclusion

Our study clearly showed a greater than 50% reduction in the ordering of repeat echocardiograms because of a High Value Care curriculum in our residency training program.

The improvement was brought on by increased awareness by house staff regarding provision of high quality care while being cognizant of the costs involved. The reduction in repeat echocardiograms resulted in more efficient use of a limited hospital resource.

Dr. Arole is chief of hospital medicine at Griffin Hospital, Derby, Conn. Dr. Zyed is in the department of internal medicine at Griffin Hospital. Dr. Njike is with the Yale University Prevention Research Center at Griffin Hospital.

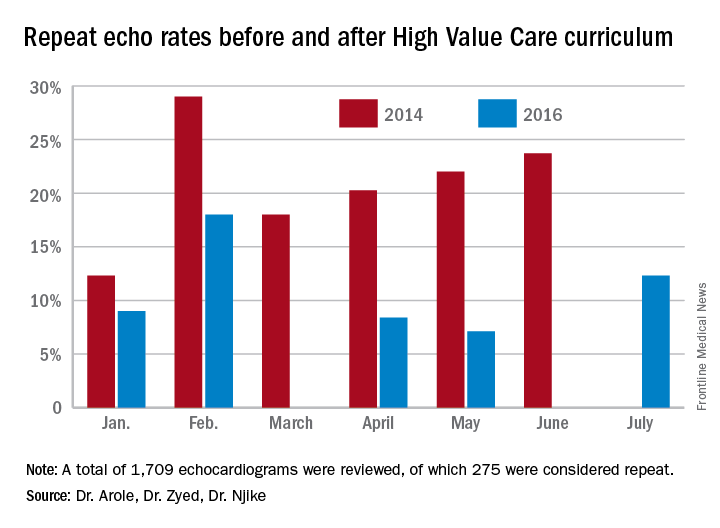

Study Title

The impact of a High Value Care curriculum on rate of repeat of trans-thoracic echocardiogram ordering among medical residents

Background

There is little data to confirm the impact of a High Value Care curriculum on echocardiogram ordering practices in a residency training program. We sought to evaluate the rate of performance of repeat transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) before and after implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum.

Methods

A High Value Care curriculum was developed for the medical residents at Griffin Hospital, a community hospital, in 2015. The curriculum included a series of lectures aimed at promoting cost-conscious care while maintaining high quality. It also involved house staff in different quality improvement (QI) projects aimed at promoting high value care.

A group of residents decided to work on an initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms. Repeat echocardiograms were defined as those performed within 6 months of a previous echocardiogram on the same patient. Only results in our EHR reflecting in-patient echocardiograms were utilized.

We retrospectively examined the rates of repeat echocardiograms performed in a 6 month period in 2014 before the High Vale Care curriculum was initiated. We assessed data from a 5 month period in 2016 to determine the rate of repeat electrocardiograms ordered at our institution.

Results

A total of 1,709 echocardiograms were reviewed in both time periods. Of these, 275 were considered repeat. At baseline, or before the implementation of a High Value Care curriculum, we examined 908 echocardiograms that were ordered, of which 21% were repeats.

After the implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum, 801 echocardiograms were ordered. Only 11% of these were repeats. This corresponds to a 52% reduction in the rate of repeated ordering of echocardiograms.

Discussion

The significant improvement in the rate of repeat echocardiograms was noted without any initiative directed specifically at echocardiogram ordering practices. During the planning phases of the proposed QI initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms, house staff noted that their colleagues were already being more selective in their echocardiogram ordering practices because of the impact of the-cost conscious care lectures they had attended, as well as hospital-wide attention on the first resident-driven QI initiative that was aimed at reducing repetitive daily labs.

As part of the reducing repetitive labs QI, house staff had to provide clear rationale for why they were ordering daily labs. The received regular updates about their lab ordering practices and direct feedback if they consistently did not provide clear rationale for ordering daily labs.

Conclusion

Our study clearly showed a greater than 50% reduction in the ordering of repeat echocardiograms because of a High Value Care curriculum in our residency training program.

The improvement was brought on by increased awareness by house staff regarding provision of high quality care while being cognizant of the costs involved. The reduction in repeat echocardiograms resulted in more efficient use of a limited hospital resource.

Dr. Arole is chief of hospital medicine at Griffin Hospital, Derby, Conn. Dr. Zyed is in the department of internal medicine at Griffin Hospital. Dr. Njike is with the Yale University Prevention Research Center at Griffin Hospital.

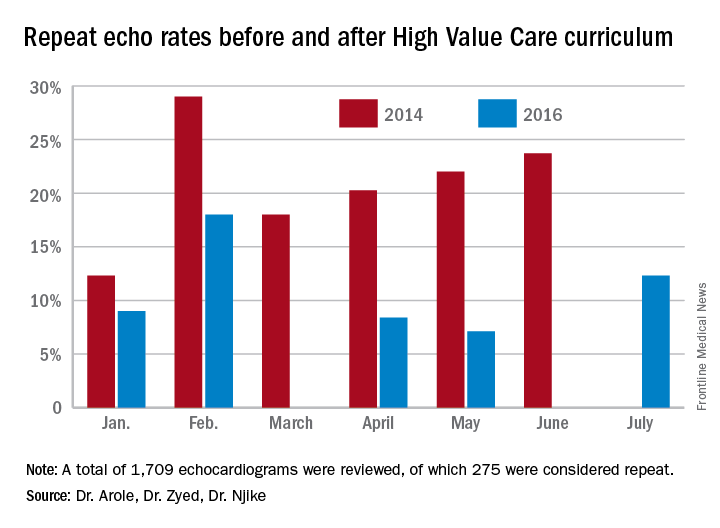

Study Title

The impact of a High Value Care curriculum on rate of repeat of trans-thoracic echocardiogram ordering among medical residents

Background

There is little data to confirm the impact of a High Value Care curriculum on echocardiogram ordering practices in a residency training program. We sought to evaluate the rate of performance of repeat transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) before and after implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum.

Methods

A High Value Care curriculum was developed for the medical residents at Griffin Hospital, a community hospital, in 2015. The curriculum included a series of lectures aimed at promoting cost-conscious care while maintaining high quality. It also involved house staff in different quality improvement (QI) projects aimed at promoting high value care.

A group of residents decided to work on an initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms. Repeat echocardiograms were defined as those performed within 6 months of a previous echocardiogram on the same patient. Only results in our EHR reflecting in-patient echocardiograms were utilized.

We retrospectively examined the rates of repeat echocardiograms performed in a 6 month period in 2014 before the High Vale Care curriculum was initiated. We assessed data from a 5 month period in 2016 to determine the rate of repeat electrocardiograms ordered at our institution.

Results

A total of 1,709 echocardiograms were reviewed in both time periods. Of these, 275 were considered repeat. At baseline, or before the implementation of a High Value Care curriculum, we examined 908 echocardiograms that were ordered, of which 21% were repeats.

After the implementation of a High Vale Care curriculum, 801 echocardiograms were ordered. Only 11% of these were repeats. This corresponds to a 52% reduction in the rate of repeated ordering of echocardiograms.

Discussion

The significant improvement in the rate of repeat echocardiograms was noted without any initiative directed specifically at echocardiogram ordering practices. During the planning phases of the proposed QI initiative to reduce repeat echocardiograms, house staff noted that their colleagues were already being more selective in their echocardiogram ordering practices because of the impact of the-cost conscious care lectures they had attended, as well as hospital-wide attention on the first resident-driven QI initiative that was aimed at reducing repetitive daily labs.

As part of the reducing repetitive labs QI, house staff had to provide clear rationale for why they were ordering daily labs. The received regular updates about their lab ordering practices and direct feedback if they consistently did not provide clear rationale for ordering daily labs.

Conclusion

Our study clearly showed a greater than 50% reduction in the ordering of repeat echocardiograms because of a High Value Care curriculum in our residency training program.

The improvement was brought on by increased awareness by house staff regarding provision of high quality care while being cognizant of the costs involved. The reduction in repeat echocardiograms resulted in more efficient use of a limited hospital resource.

Dr. Arole is chief of hospital medicine at Griffin Hospital, Derby, Conn. Dr. Zyed is in the department of internal medicine at Griffin Hospital. Dr. Njike is with the Yale University Prevention Research Center at Griffin Hospital.

QI enthusiast to QI leader: John Bulger, DO

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog - July 2017

“We Are Not Done Changing”

Recently, the online version of JAMA published an original investigation titled, “Patient Mortality During Unannounced Accreditation Surveys at US Hospitals.” The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effect of heightened vigilance during unannounced accreditation surveys on safety and quality of inpatient care.

The authors found that there was a significant reduction in mortality in patients admitted during the week of surveys by The Joint Commission. The change was more significant in major teaching hospitals, where mortality fell from 6.41% to 5.93% during survey weeks, a 5.9% relative decrease. The positive effects of being monitored have been well documented in all kinds of arenas, such as hand washing and antibiotic stewardship. But mortality?

Overall, I feel like I’m a reasonable person, but the clear lack of interest – or willingness to consider that this might not be a good idea on the part of the hospitalist in charge – incited a certain amount of anger and disbelief in me. She also received an antibiotic that she had a documented allergy to – a clear medical error. I instructed my sis-in-law to refuse access to the line; it was removed, and she ultimately recovered to discharge.

This brings me back to the JAMA study. It’s easy to perceive unannounced inspections as merely an inconvenience, where things are locked up that normally aren’t, or where that coveted cup of coffee you normally bring on rounds to get you through your day is summarily yanked out of your hand.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• How Often Do You Ask This (Ineffective) Question? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM• Building a Practice that People Want to Be a Part Of by Leslie Flores, MHA• A Need for Medicare Appeals Process Reform in Hospital Observation Care by Anne Sheehy, MD, MS, FHM

“We Are Not Done Changing”

Recently, the online version of JAMA published an original investigation titled, “Patient Mortality During Unannounced Accreditation Surveys at US Hospitals.” The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effect of heightened vigilance during unannounced accreditation surveys on safety and quality of inpatient care.

The authors found that there was a significant reduction in mortality in patients admitted during the week of surveys by The Joint Commission. The change was more significant in major teaching hospitals, where mortality fell from 6.41% to 5.93% during survey weeks, a 5.9% relative decrease. The positive effects of being monitored have been well documented in all kinds of arenas, such as hand washing and antibiotic stewardship. But mortality?

Overall, I feel like I’m a reasonable person, but the clear lack of interest – or willingness to consider that this might not be a good idea on the part of the hospitalist in charge – incited a certain amount of anger and disbelief in me. She also received an antibiotic that she had a documented allergy to – a clear medical error. I instructed my sis-in-law to refuse access to the line; it was removed, and she ultimately recovered to discharge.

This brings me back to the JAMA study. It’s easy to perceive unannounced inspections as merely an inconvenience, where things are locked up that normally aren’t, or where that coveted cup of coffee you normally bring on rounds to get you through your day is summarily yanked out of your hand.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• How Often Do You Ask This (Ineffective) Question? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM• Building a Practice that People Want to Be a Part Of by Leslie Flores, MHA• A Need for Medicare Appeals Process Reform in Hospital Observation Care by Anne Sheehy, MD, MS, FHM

“We Are Not Done Changing”

Recently, the online version of JAMA published an original investigation titled, “Patient Mortality During Unannounced Accreditation Surveys at US Hospitals.” The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effect of heightened vigilance during unannounced accreditation surveys on safety and quality of inpatient care.

The authors found that there was a significant reduction in mortality in patients admitted during the week of surveys by The Joint Commission. The change was more significant in major teaching hospitals, where mortality fell from 6.41% to 5.93% during survey weeks, a 5.9% relative decrease. The positive effects of being monitored have been well documented in all kinds of arenas, such as hand washing and antibiotic stewardship. But mortality?

Overall, I feel like I’m a reasonable person, but the clear lack of interest – or willingness to consider that this might not be a good idea on the part of the hospitalist in charge – incited a certain amount of anger and disbelief in me. She also received an antibiotic that she had a documented allergy to – a clear medical error. I instructed my sis-in-law to refuse access to the line; it was removed, and she ultimately recovered to discharge.

This brings me back to the JAMA study. It’s easy to perceive unannounced inspections as merely an inconvenience, where things are locked up that normally aren’t, or where that coveted cup of coffee you normally bring on rounds to get you through your day is summarily yanked out of your hand.

Read the full text of this blog post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• How Often Do You Ask This (Ineffective) Question? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM• Building a Practice that People Want to Be a Part Of by Leslie Flores, MHA• A Need for Medicare Appeals Process Reform in Hospital Observation Care by Anne Sheehy, MD, MS, FHM

Sneak Peek: Journal of Hospital Medicine – July 2017

BACKGROUND: Medicare patients account for approximately 50% of hospital days. Hospitalization in older adults often results in poor outcomes.

OBJECTIVE: To test the feasibility and impact of using Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) quality indicators (QIs) as a therapeutic intervention to improve care of hospitalized older adults.

SETTING: Large tertiary hospital in the greater New York Metropolitan area.

PATIENTS: Hospitalized patients, 75 and over, admitted to medical units.

INTERVENTION: A checklist, comprised of four ACOVE QIs, administered during daily interdisciplinary rounds: venous thrombosis prophylaxis (VTE) (QI 1), indwelling bladder catheters (QI 2), mobilization (QI 3), and delirium evaluation (QI 4).

MEASUREMENTS: Variables were extracted from electronic medical records with QI compliance as the primary outcome, and length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, and readmissions as secondary outcomes. Generalized linear mixed models for binary clustered data were used to estimate compliance rates for each group (intervention group or control group) in the postintervention period, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS: Of the 2,396 patients, 530 were on an intervention unit. In those patients not already compliant with VTE, the compliance rate was 57% in intervention vs. 39% in control (P less than .0056). For indwelling catheters, mobilization, and delirium evaluation, overall compliance was significantly higher in the intervention group 72.2% vs. 54.4% (P = .1061), 62.9% vs. 48.2% (P less than .0001), and 27.9% vs. 21.7% (P = .0027), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS: The study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating ACOVE QIs to improve the quality of care in hospitalized older adults.

Also in JHM

Use of simulation to assess incoming interns’ recognition of opportunities to choose wisely

AUTHORS: Kathleen M. Wiest, Jeanne M. Farnan, MD, MHPE, Ellen Byrne, Lukas Matern, Melissa Cappaert, MA, Kristen Hirsch, Vineet M. Arora, MD, MAPP

Clinician attitudes regarding ICD deactivation in DNR/DNI patients

AUTHORS: Andrew J. Bradley, MD, Adam D. Marks, MD, MPH

Using standardized patients to assess hospitalist communication skills

AUTHORS: Dennis T. Chang, MD, Micah Mann, MD, Terry Sommer, BFA, Robert Fallar, PhD, Alan Weinberg, MS, Erica Friedman, MD

Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: An exploratory qualitative study

AUTHORS: Nathan Houchens, MD, Molly Harrod, PhD, Stephanie Moody, PhD, Karen E. Fowler, MPH, Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH

A simple algorithm for predicting bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills: A prospective observational study

AUTHORS: Takayuki Komatsu, MD, PhD, Erika Takahashi, MD, Kentaro Mishima, MD, Takeo Toyoda, MD, Fumihiro Saitoh, MD, Akari Yasuda, RN, Joe Matsuoka, PhD, Manabu Sugita, MD, PhD, Joel Branch, MD, Makoto Aoki, MD, Lawrence M. Tierney Jr., MD, Kenji Inoue, MD, PhD

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

BACKGROUND: Medicare patients account for approximately 50% of hospital days. Hospitalization in older adults often results in poor outcomes.

OBJECTIVE: To test the feasibility and impact of using Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) quality indicators (QIs) as a therapeutic intervention to improve care of hospitalized older adults.

SETTING: Large tertiary hospital in the greater New York Metropolitan area.

PATIENTS: Hospitalized patients, 75 and over, admitted to medical units.

INTERVENTION: A checklist, comprised of four ACOVE QIs, administered during daily interdisciplinary rounds: venous thrombosis prophylaxis (VTE) (QI 1), indwelling bladder catheters (QI 2), mobilization (QI 3), and delirium evaluation (QI 4).

MEASUREMENTS: Variables were extracted from electronic medical records with QI compliance as the primary outcome, and length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, and readmissions as secondary outcomes. Generalized linear mixed models for binary clustered data were used to estimate compliance rates for each group (intervention group or control group) in the postintervention period, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS: Of the 2,396 patients, 530 were on an intervention unit. In those patients not already compliant with VTE, the compliance rate was 57% in intervention vs. 39% in control (P less than .0056). For indwelling catheters, mobilization, and delirium evaluation, overall compliance was significantly higher in the intervention group 72.2% vs. 54.4% (P = .1061), 62.9% vs. 48.2% (P less than .0001), and 27.9% vs. 21.7% (P = .0027), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS: The study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating ACOVE QIs to improve the quality of care in hospitalized older adults.

Also in JHM

Use of simulation to assess incoming interns’ recognition of opportunities to choose wisely

AUTHORS: Kathleen M. Wiest, Jeanne M. Farnan, MD, MHPE, Ellen Byrne, Lukas Matern, Melissa Cappaert, MA, Kristen Hirsch, Vineet M. Arora, MD, MAPP

Clinician attitudes regarding ICD deactivation in DNR/DNI patients

AUTHORS: Andrew J. Bradley, MD, Adam D. Marks, MD, MPH

Using standardized patients to assess hospitalist communication skills

AUTHORS: Dennis T. Chang, MD, Micah Mann, MD, Terry Sommer, BFA, Robert Fallar, PhD, Alan Weinberg, MS, Erica Friedman, MD

Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: An exploratory qualitative study

AUTHORS: Nathan Houchens, MD, Molly Harrod, PhD, Stephanie Moody, PhD, Karen E. Fowler, MPH, Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH

A simple algorithm for predicting bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills: A prospective observational study

AUTHORS: Takayuki Komatsu, MD, PhD, Erika Takahashi, MD, Kentaro Mishima, MD, Takeo Toyoda, MD, Fumihiro Saitoh, MD, Akari Yasuda, RN, Joe Matsuoka, PhD, Manabu Sugita, MD, PhD, Joel Branch, MD, Makoto Aoki, MD, Lawrence M. Tierney Jr., MD, Kenji Inoue, MD, PhD

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

BACKGROUND: Medicare patients account for approximately 50% of hospital days. Hospitalization in older adults often results in poor outcomes.

OBJECTIVE: To test the feasibility and impact of using Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) quality indicators (QIs) as a therapeutic intervention to improve care of hospitalized older adults.

SETTING: Large tertiary hospital in the greater New York Metropolitan area.

PATIENTS: Hospitalized patients, 75 and over, admitted to medical units.

INTERVENTION: A checklist, comprised of four ACOVE QIs, administered during daily interdisciplinary rounds: venous thrombosis prophylaxis (VTE) (QI 1), indwelling bladder catheters (QI 2), mobilization (QI 3), and delirium evaluation (QI 4).

MEASUREMENTS: Variables were extracted from electronic medical records with QI compliance as the primary outcome, and length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, and readmissions as secondary outcomes. Generalized linear mixed models for binary clustered data were used to estimate compliance rates for each group (intervention group or control group) in the postintervention period, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS: Of the 2,396 patients, 530 were on an intervention unit. In those patients not already compliant with VTE, the compliance rate was 57% in intervention vs. 39% in control (P less than .0056). For indwelling catheters, mobilization, and delirium evaluation, overall compliance was significantly higher in the intervention group 72.2% vs. 54.4% (P = .1061), 62.9% vs. 48.2% (P less than .0001), and 27.9% vs. 21.7% (P = .0027), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS: The study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating ACOVE QIs to improve the quality of care in hospitalized older adults.

Also in JHM

Use of simulation to assess incoming interns’ recognition of opportunities to choose wisely

AUTHORS: Kathleen M. Wiest, Jeanne M. Farnan, MD, MHPE, Ellen Byrne, Lukas Matern, Melissa Cappaert, MA, Kristen Hirsch, Vineet M. Arora, MD, MAPP

Clinician attitudes regarding ICD deactivation in DNR/DNI patients

AUTHORS: Andrew J. Bradley, MD, Adam D. Marks, MD, MPH

Using standardized patients to assess hospitalist communication skills

AUTHORS: Dennis T. Chang, MD, Micah Mann, MD, Terry Sommer, BFA, Robert Fallar, PhD, Alan Weinberg, MS, Erica Friedman, MD

Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: An exploratory qualitative study

AUTHORS: Nathan Houchens, MD, Molly Harrod, PhD, Stephanie Moody, PhD, Karen E. Fowler, MPH, Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH

A simple algorithm for predicting bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills: A prospective observational study

AUTHORS: Takayuki Komatsu, MD, PhD, Erika Takahashi, MD, Kentaro Mishima, MD, Takeo Toyoda, MD, Fumihiro Saitoh, MD, Akari Yasuda, RN, Joe Matsuoka, PhD, Manabu Sugita, MD, PhD, Joel Branch, MD, Makoto Aoki, MD, Lawrence M. Tierney Jr., MD, Kenji Inoue, MD, PhD

For more articles and subscription information, visit www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com.

Crossing the personal quality chasm: QI enthusiast to QI leader

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Everything We Say and Do: Setting discharge goals and visit expectations

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I always ensure at the end of my visit with a patient and their family that they know when to expect me to return to see their child again.

Why I do it

One of the biggest frustrations I hear from families pertains to the discharge process. In talking with families, they want to know the approximate time for discharge. Often, during morning rounds, we mention that the patient may be able to go home later in the day and we say that we will come in again later to check on them. However, unless we give families a time frame for when we will come back and do that check, they are left waiting without any clear expectations.

How I do it

One of our goals during morning family-centered rounds is to discuss discharge for every patient, every day. Along with discussing the possibility of going home, we try to give the family goals that they can work on throughout the day that are tied to discharge – for example, the approximate by-mouth intake for a toddler admitted for gastroenteritis and dehydration.

I also give the family an approximate time when either I or the resident team will come back to see if they have achieved this goal. This may be either late afternoon or first thing in the morning if we are planning an early-morning discharge before rounds. The families seem to find this helpful because they are not tied to the room all day waiting for the doctor to come back.

I also make sure that the families know they can contact their nurse any time if they need to see any of the doctors sooner than we planned. I let them know that a physician is here on the floor 24 hours a day and that the nurses can easily reach us at any time if they have further concerns. In my experience, this is reassuring to our families.

Christine Hrach is a pediatric hospitalist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I always ensure at the end of my visit with a patient and their family that they know when to expect me to return to see their child again.

Why I do it

One of the biggest frustrations I hear from families pertains to the discharge process. In talking with families, they want to know the approximate time for discharge. Often, during morning rounds, we mention that the patient may be able to go home later in the day and we say that we will come in again later to check on them. However, unless we give families a time frame for when we will come back and do that check, they are left waiting without any clear expectations.

How I do it

One of our goals during morning family-centered rounds is to discuss discharge for every patient, every day. Along with discussing the possibility of going home, we try to give the family goals that they can work on throughout the day that are tied to discharge – for example, the approximate by-mouth intake for a toddler admitted for gastroenteritis and dehydration.

I also give the family an approximate time when either I or the resident team will come back to see if they have achieved this goal. This may be either late afternoon or first thing in the morning if we are planning an early-morning discharge before rounds. The families seem to find this helpful because they are not tied to the room all day waiting for the doctor to come back.

I also make sure that the families know they can contact their nurse any time if they need to see any of the doctors sooner than we planned. I let them know that a physician is here on the floor 24 hours a day and that the nurses can easily reach us at any time if they have further concerns. In my experience, this is reassuring to our families.

Christine Hrach is a pediatric hospitalist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I always ensure at the end of my visit with a patient and their family that they know when to expect me to return to see their child again.

Why I do it

One of the biggest frustrations I hear from families pertains to the discharge process. In talking with families, they want to know the approximate time for discharge. Often, during morning rounds, we mention that the patient may be able to go home later in the day and we say that we will come in again later to check on them. However, unless we give families a time frame for when we will come back and do that check, they are left waiting without any clear expectations.

How I do it

One of our goals during morning family-centered rounds is to discuss discharge for every patient, every day. Along with discussing the possibility of going home, we try to give the family goals that they can work on throughout the day that are tied to discharge – for example, the approximate by-mouth intake for a toddler admitted for gastroenteritis and dehydration.

I also give the family an approximate time when either I or the resident team will come back to see if they have achieved this goal. This may be either late afternoon or first thing in the morning if we are planning an early-morning discharge before rounds. The families seem to find this helpful because they are not tied to the room all day waiting for the doctor to come back.

I also make sure that the families know they can contact their nurse any time if they need to see any of the doctors sooner than we planned. I let them know that a physician is here on the floor 24 hours a day and that the nurses can easily reach us at any time if they have further concerns. In my experience, this is reassuring to our families.

Christine Hrach is a pediatric hospitalist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Will artificial intelligence make us better doctors?

Given the amount of time physicians spend entering data, clicking through screens, navigating pages, and logging in to computers, one would have hoped that substantial near-term payback for such efforts would have materialized.

Many of us believed this would take the form of health information exchange – the ability to easily access clinical information from hospitals or clinics other than our own, creating a more complete picture of the patient before us. To our disappointment, true information exchange has yet to materialize. (We won’t debate here whether politics or technology is culpable.) We are left to look elsewhere for the benefits of the digitization of the medical records and other sources of health care knowledge.

Lately, there has been a lot of talk about the promise of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) in health care. Much of the resurgence of interest in AI can be traced to IBM Watson’s appearance as a contestant on Jeopardy in 2011. Watson, a natural language supercomputer with enough power to process the equivalent of a million books per second, had access to 200 million pages of content, including the full text of Wikipedia, for Jeopardy.1 Watson handily outperformed its human opponents – two Jeopardy savants who were also the most successful contestants in game show history – taking the $1 million first prize but struggling in categories with clues containing only a few words.

MD Anderson and Watson: Dashed hopes follow initial promise

As a result of growing recognition of AI’s potential in health care, IBM began collaborations with a number of health care organizations to deploy Watson.

In 2013, MD Anderson Cancer Center and IBM began a pilot to develop an oncology clinical decision support technology tool powered by Watson to aid MD Anderson “in its mission to eradicate cancer.” Recently, it was announced that the project – which cost the cancer center $62 million – has been put on hold, and MD Anderson is looking for other contractors to replace IBM.

While administrative problems are at least partly responsible for the project’s challenges, the undertaking has raised issues with the quality and quantity of data in health care that call into question the ability of AI to work as well in health care as it did on Jeopardy, at least in the short term.

Health care: Not as data rich as you might think

“We are not ‘Big Data’ in health care, yet.” – Dale Sanders, Health Catalyst.2

In its quest for Jeopardy victory, Watson accessed a massive data storehouse subsuming a vast array of knowledge assembled over the course of human history. Conversely, for health care, Watson is limited to a few decades of scientific journals (that may not contribute to diagnosis and treatment as much as one might think), claims data geared to billing without much clinical information like outcomes, and clinical data from progress notes (plagued by inaccuracies, serial “copy and paste,” and nonstandardized language and numeric representations), and variable-format reports from lab, radiology, pathology, and other disciplines.

To articulate how data-poor health care is, Dale Sanders, executive vice president for software at Health Catalyst, notes that a Boeing 787 generates 500GB of data in a six hour flight while one patient may generate just 100MB of data in an entire year.2 He pointed out that, in the near term, AI platforms like Watson simply do not have enough data substrate to impact health care as many hoped it would. Over the longer term, he says, if health care can develop a coherent, standard approach to data content, AI may fulfill its promise.

What can AI and related technologies achieve in the near-term?

“AI seems to have replaced Uber as the most overused word or phrase in digital health.” – Reporter Stephanie Baum, paraphrasing from an interview with Bob Kocher, Venrock Partners.3

My observations tell me that we have already made some progress and are likely to make more strides in the coming years, thanks to AI, machine learning, and natural language processing. A few areas of potential gain are:

Clinical documentation

Technology that can derive meaning from words or groups of words can help with more accurate clinical documentation. For example, if a patient has a documented UTI but also has in the record an 11 on the Glasgow Coma Scale, a systolic BP of 90, and a respiratory rate of 24, technology can alert the physician to document sepsis.

Quality measurement and reporting