User login

Move to Allow Patients to Request 'Refund' Appealing and Risky

We’ve all seen hundreds of commercials from companies advertising products and services with a money-back guarantee. The Men’s Warehouse, for example, has been promising men across the globe for over a decade, “You’re going to like the way you look. I guarantee it!” But to date, no one has made such a “guarantee” in the healthcare industry. Buying a suit is not exactly like getting your gallbladder removed.

We know that medical diagnoses and treatments are filled with uncertainty in expected processes and outcomes, because the factors that are dependent on these processes and outcomes are endless. These include patient factors (overall health, functional status, comorbid conditions), procedural factors (emergency versus elective, time of day or night), and facility factors (having the optimal team with skills that match the patient need, having all the right products and equipment). Although we know that many medical procedures have a relatively predictable risk of complications, unpredictable complications still occur, so how can we ever offer a guarantee for the interventions we perform on patients?

First of Its Kind

David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president and CEO of Geisinger Health System, is doing just that. This healthcare system has developed an application, called the Geisinger ProvenExperience, which can be downloaded onto a smartphone. After a procedure, each patient is given a code for the condition that was treated. With that code, the patient can enter feedback on the services provided and can then request a refund if they are not fully satisfied.

Most remarkably, the request for a refund is based on the judgment of the recipient, not on that of the provider(s). At a recent public meeting, Dr. Feinberg said of the new program: “We’re going to do everything right. That’s our job, that’s our promise to you … and you’re the judge. If you don’t think so, we’re going to apologize, we’re going to try to fix it for the next guy, and, as a small token of appreciation, we’re going to give you some money back.”1

Although many are skeptical about whether or not the program will be successful, much less viable, Dr. Feinberg contends that early feedback on the program has shown that most patients don’t actually want their money back. Instead, if their needs have not been met, most have just wanted a sincere apology and a commitment to make things better for others. Dr. Feinberg also contests that even if this is not the best or only approach to improving healthcare (quickly), we should all feel compelled to do something about our repeated failures in meeting patient expectations in the quality and/or experience of their care; and because no other industry works this way, other than healthcare. Typically, when consumers get fed up with poor service in other industries, disruptive innovations (Uber, for example) are created to satisfy customers’ desires.

A New Paradigm?

In healthcare, patients certainly should be dissatisfied if they experience a preventable harm event. Some types of harm are considered “always preventable,” such as wrong-site surgery. These events are extremely rare and, thus, do not constitute most cases of harm in hospitals these days. Such “never events” are relatively well defined and have been adopted for nonpayment by Medicare and other insurers, which can serve to buffer a patient’s financial liability in the small number of these cases. For other, more common, types of preventable harm, some hospitals have instituted apology and disclosure policies, and some will also relieve the patient of the portion of the bill attributable to the preventable harm. But not all hospitals have adopted such policies, despite the fact that they are widely endorsed by influential agencies, including The Joint Commission, the American Medical Association, Leapfrog Group, the National Quality Forum, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

And, even for hospitals that have adopted such “best practice” policies, there is not always clear consensus on what constitutes preventable harm. Generally, the “judgment call” about what constitutes preventable harm is made by healthcare systems and providers—not patients. In addition, many cases of harm that are not necessarily preventable can often result in great dissatisfaction for the patient. There are countless stories of patients who are unfortunately harmed in the course of medical procedures, but who were informed of the possible risks of the procedure and consented to have the procedure performed despite the risks. These situations, which are agonizingly difficult for the system, the providers, and the patients, have no good solutions. Systems cannot “own” all harm, such as those resulting from the disease process itself or from risky and invasive procedures intended to benefit the patient. And there is ongoing inconsistency in healthcare systems when it comes to their willingness and ability to consistently define preventable harm or to disclose, apologize, and forgive payments in such cases.

So, while this move to allow patients to ask for a “refund” seems both extremely appealing and extremely risky, it certainly seems as though it will greatly enhance the trust of patients and their families in the Geisinger Health System.

I, among others, will eagerly follow the results of this program; while getting a cholecystectomy is not the same as buying a men’s suit, I do hope that someday, I will be able to say to every patient entering my healthcare system that before they leave, “You’re going to like the way you feel. I guarantee it!” TH

References

1. Guydish M. Geisinger CEO: money-back guarantee for health care coming. November 6, 2015. Times Leader website. Available at: http://timesleader.com/news/492790/geisinger-ceo-money-back-guarantee-for-health-car-coming. Accessed December 5, 2015.

2. Luthra S. When something goes wrong at the hospital, who pays? November 11, 2015. Kaiser Health News. Available at: http://khn.org/news/when-something-goes-wrong-at-the-hospital-who-pays/?utm_source=Managed&utm_campaign=9e17712a95-Quality+%26+Patient+Safety+Update&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ebe1fa6178-9e17712a95-319388717. Accessed December 5, 2015.

We’ve all seen hundreds of commercials from companies advertising products and services with a money-back guarantee. The Men’s Warehouse, for example, has been promising men across the globe for over a decade, “You’re going to like the way you look. I guarantee it!” But to date, no one has made such a “guarantee” in the healthcare industry. Buying a suit is not exactly like getting your gallbladder removed.

We know that medical diagnoses and treatments are filled with uncertainty in expected processes and outcomes, because the factors that are dependent on these processes and outcomes are endless. These include patient factors (overall health, functional status, comorbid conditions), procedural factors (emergency versus elective, time of day or night), and facility factors (having the optimal team with skills that match the patient need, having all the right products and equipment). Although we know that many medical procedures have a relatively predictable risk of complications, unpredictable complications still occur, so how can we ever offer a guarantee for the interventions we perform on patients?

First of Its Kind

David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president and CEO of Geisinger Health System, is doing just that. This healthcare system has developed an application, called the Geisinger ProvenExperience, which can be downloaded onto a smartphone. After a procedure, each patient is given a code for the condition that was treated. With that code, the patient can enter feedback on the services provided and can then request a refund if they are not fully satisfied.

Most remarkably, the request for a refund is based on the judgment of the recipient, not on that of the provider(s). At a recent public meeting, Dr. Feinberg said of the new program: “We’re going to do everything right. That’s our job, that’s our promise to you … and you’re the judge. If you don’t think so, we’re going to apologize, we’re going to try to fix it for the next guy, and, as a small token of appreciation, we’re going to give you some money back.”1

Although many are skeptical about whether or not the program will be successful, much less viable, Dr. Feinberg contends that early feedback on the program has shown that most patients don’t actually want their money back. Instead, if their needs have not been met, most have just wanted a sincere apology and a commitment to make things better for others. Dr. Feinberg also contests that even if this is not the best or only approach to improving healthcare (quickly), we should all feel compelled to do something about our repeated failures in meeting patient expectations in the quality and/or experience of their care; and because no other industry works this way, other than healthcare. Typically, when consumers get fed up with poor service in other industries, disruptive innovations (Uber, for example) are created to satisfy customers’ desires.

A New Paradigm?

In healthcare, patients certainly should be dissatisfied if they experience a preventable harm event. Some types of harm are considered “always preventable,” such as wrong-site surgery. These events are extremely rare and, thus, do not constitute most cases of harm in hospitals these days. Such “never events” are relatively well defined and have been adopted for nonpayment by Medicare and other insurers, which can serve to buffer a patient’s financial liability in the small number of these cases. For other, more common, types of preventable harm, some hospitals have instituted apology and disclosure policies, and some will also relieve the patient of the portion of the bill attributable to the preventable harm. But not all hospitals have adopted such policies, despite the fact that they are widely endorsed by influential agencies, including The Joint Commission, the American Medical Association, Leapfrog Group, the National Quality Forum, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

And, even for hospitals that have adopted such “best practice” policies, there is not always clear consensus on what constitutes preventable harm. Generally, the “judgment call” about what constitutes preventable harm is made by healthcare systems and providers—not patients. In addition, many cases of harm that are not necessarily preventable can often result in great dissatisfaction for the patient. There are countless stories of patients who are unfortunately harmed in the course of medical procedures, but who were informed of the possible risks of the procedure and consented to have the procedure performed despite the risks. These situations, which are agonizingly difficult for the system, the providers, and the patients, have no good solutions. Systems cannot “own” all harm, such as those resulting from the disease process itself or from risky and invasive procedures intended to benefit the patient. And there is ongoing inconsistency in healthcare systems when it comes to their willingness and ability to consistently define preventable harm or to disclose, apologize, and forgive payments in such cases.

So, while this move to allow patients to ask for a “refund” seems both extremely appealing and extremely risky, it certainly seems as though it will greatly enhance the trust of patients and their families in the Geisinger Health System.

I, among others, will eagerly follow the results of this program; while getting a cholecystectomy is not the same as buying a men’s suit, I do hope that someday, I will be able to say to every patient entering my healthcare system that before they leave, “You’re going to like the way you feel. I guarantee it!” TH

References

1. Guydish M. Geisinger CEO: money-back guarantee for health care coming. November 6, 2015. Times Leader website. Available at: http://timesleader.com/news/492790/geisinger-ceo-money-back-guarantee-for-health-car-coming. Accessed December 5, 2015.

2. Luthra S. When something goes wrong at the hospital, who pays? November 11, 2015. Kaiser Health News. Available at: http://khn.org/news/when-something-goes-wrong-at-the-hospital-who-pays/?utm_source=Managed&utm_campaign=9e17712a95-Quality+%26+Patient+Safety+Update&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ebe1fa6178-9e17712a95-319388717. Accessed December 5, 2015.

We’ve all seen hundreds of commercials from companies advertising products and services with a money-back guarantee. The Men’s Warehouse, for example, has been promising men across the globe for over a decade, “You’re going to like the way you look. I guarantee it!” But to date, no one has made such a “guarantee” in the healthcare industry. Buying a suit is not exactly like getting your gallbladder removed.

We know that medical diagnoses and treatments are filled with uncertainty in expected processes and outcomes, because the factors that are dependent on these processes and outcomes are endless. These include patient factors (overall health, functional status, comorbid conditions), procedural factors (emergency versus elective, time of day or night), and facility factors (having the optimal team with skills that match the patient need, having all the right products and equipment). Although we know that many medical procedures have a relatively predictable risk of complications, unpredictable complications still occur, so how can we ever offer a guarantee for the interventions we perform on patients?

First of Its Kind

David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president and CEO of Geisinger Health System, is doing just that. This healthcare system has developed an application, called the Geisinger ProvenExperience, which can be downloaded onto a smartphone. After a procedure, each patient is given a code for the condition that was treated. With that code, the patient can enter feedback on the services provided and can then request a refund if they are not fully satisfied.

Most remarkably, the request for a refund is based on the judgment of the recipient, not on that of the provider(s). At a recent public meeting, Dr. Feinberg said of the new program: “We’re going to do everything right. That’s our job, that’s our promise to you … and you’re the judge. If you don’t think so, we’re going to apologize, we’re going to try to fix it for the next guy, and, as a small token of appreciation, we’re going to give you some money back.”1

Although many are skeptical about whether or not the program will be successful, much less viable, Dr. Feinberg contends that early feedback on the program has shown that most patients don’t actually want their money back. Instead, if their needs have not been met, most have just wanted a sincere apology and a commitment to make things better for others. Dr. Feinberg also contests that even if this is not the best or only approach to improving healthcare (quickly), we should all feel compelled to do something about our repeated failures in meeting patient expectations in the quality and/or experience of their care; and because no other industry works this way, other than healthcare. Typically, when consumers get fed up with poor service in other industries, disruptive innovations (Uber, for example) are created to satisfy customers’ desires.

A New Paradigm?

In healthcare, patients certainly should be dissatisfied if they experience a preventable harm event. Some types of harm are considered “always preventable,” such as wrong-site surgery. These events are extremely rare and, thus, do not constitute most cases of harm in hospitals these days. Such “never events” are relatively well defined and have been adopted for nonpayment by Medicare and other insurers, which can serve to buffer a patient’s financial liability in the small number of these cases. For other, more common, types of preventable harm, some hospitals have instituted apology and disclosure policies, and some will also relieve the patient of the portion of the bill attributable to the preventable harm. But not all hospitals have adopted such policies, despite the fact that they are widely endorsed by influential agencies, including The Joint Commission, the American Medical Association, Leapfrog Group, the National Quality Forum, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

And, even for hospitals that have adopted such “best practice” policies, there is not always clear consensus on what constitutes preventable harm. Generally, the “judgment call” about what constitutes preventable harm is made by healthcare systems and providers—not patients. In addition, many cases of harm that are not necessarily preventable can often result in great dissatisfaction for the patient. There are countless stories of patients who are unfortunately harmed in the course of medical procedures, but who were informed of the possible risks of the procedure and consented to have the procedure performed despite the risks. These situations, which are agonizingly difficult for the system, the providers, and the patients, have no good solutions. Systems cannot “own” all harm, such as those resulting from the disease process itself or from risky and invasive procedures intended to benefit the patient. And there is ongoing inconsistency in healthcare systems when it comes to their willingness and ability to consistently define preventable harm or to disclose, apologize, and forgive payments in such cases.

So, while this move to allow patients to ask for a “refund” seems both extremely appealing and extremely risky, it certainly seems as though it will greatly enhance the trust of patients and their families in the Geisinger Health System.

I, among others, will eagerly follow the results of this program; while getting a cholecystectomy is not the same as buying a men’s suit, I do hope that someday, I will be able to say to every patient entering my healthcare system that before they leave, “You’re going to like the way you feel. I guarantee it!” TH

References

1. Guydish M. Geisinger CEO: money-back guarantee for health care coming. November 6, 2015. Times Leader website. Available at: http://timesleader.com/news/492790/geisinger-ceo-money-back-guarantee-for-health-car-coming. Accessed December 5, 2015.

2. Luthra S. When something goes wrong at the hospital, who pays? November 11, 2015. Kaiser Health News. Available at: http://khn.org/news/when-something-goes-wrong-at-the-hospital-who-pays/?utm_source=Managed&utm_campaign=9e17712a95-Quality+%26+Patient+Safety+Update&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ebe1fa6178-9e17712a95-319388717. Accessed December 5, 2015.

99% of Medical-Device Monitoring Alerts Not Actionable

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

LISTEN NOW: Scott Sears, MD, Discusses Hospitalist Challenges with Unassigned, Uninsured Patients

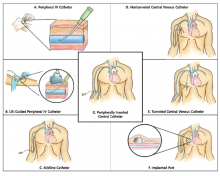

Guide Helps Hospitalists Choose Most Appropriate Catheter for Patients

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

Institute of Medicine Report Examines Medical Misdiagnoses

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Quality Improvement Initiative Targets Sepsis

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: [email protected].

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: [email protected].

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: [email protected].

Early Mobility Program

“I didn’t get out of bed for 10 days”

—Anonymous patient admitted to a skilled nursing facility post-hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation

Readmission penalties, “Medicare spending per beneficiary” under value-based purchasing, and the move to accountable care are propelling hospitalists to do more to ensure our patients recover well in the least restrictive setting, without returning to the hospital. As we build systems to support patient recovery, we are focused on a medical model, paying attention to managing diseases and reconciling medications. At the same time, there is a growing awareness that functional status and mobility are critical pieces of patient care during and post-hospitalization.

Regardless of principal diagnosis and comorbidities, patients’ functional mobility ultimately determines their trajectory during recovery. To illustrate the importance of functional status and outcomes, one study showed that models predicting readmission based on functional measures outperformed those based on comorbidities.1

The negative effects of hospitalization on patient mobility, and in turn, on recovery, have been recognized for a long time. Immobility is associated with functional decline, which contributes to falls, increased length of stay, delirium, loss of ability to perform activities of daily living, and loss of ambulatory independence. A number of studies have reported successful early mobility programs in critical care and surgical patients.2 Fewer have been reported in general medical patients.3 Taken together, they suggest that a program for mobilizing patients, using a team approach, is an important part of recovery during and after hospitalization.

The purpose of this column is to report the components of one healthcare system’s mobility program for general medical-surgical patients.

Early Mobility: A Case Study

St Luke’s University Health Network (SLUHN) in northeastern Pennsylvania has implemented an early mobility program as part of its broader strategy to reduce readmissions and discharge as many patients home as possible. Although the SLUHN early mobility program depends on nursing, nursing assistants, and the judicious use of therapists, physician leadership during implementation and maintenance of the program has been essential. Moreover, because the program represents a culture shift, especially for nursing, leadership and change management are crucial ingredients for success. Below are the key steps in the SLUHN early mobility program.

Establish baseline functional status. Recording baseline function is an essential first step. For patients admitted through the ED, nurses collect ambulatory status, patient needs for assistance, ambulatory aids/special equipment, and history of falls. They populate an SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) form with this information and, as part of the handoff, ensure that it is transmitted to the inpatient nurse receiving the patient.

Obtain and document Barthel Index score. SLUHN uses the Barthel Index (see Figure 1) to establish a patient’s degree of independence and need for supervision. The index is scored on a 0-100 scale, with a higher score corresponding to a greater degree of independence. SLUHN created three categories: 0-59, stage 1; 60-84, stage 2; 85-100, stage 3.

Patient mobility plan. Based on the Barthel-derived stage, a patient is assigned a mobility plan.

The role of nursing. The patient’s registered nurse is responsible for implementing the “patient mobility plan.” The nurse initiates an “interdisciplinary plan of care,” in which the mobility stage is written on the SBAR handoff report tool. The report is discussed at change of shift and at multidisciplinary rounds. Nursing also communicates the mobility plan to the nursing assistants and assigns responsibilities for the mobility plan (activities of daily living, out of bed, ambulation, and so on), including verifying documentation of daily activities and assessing the patient’s response to the activity level of the assigned stage.

Further, nursing maintains and revises the mobility status on the SBAR, updates progress toward outcomes on the care plan, consults with the physician and team regarding the discharge plan, and discusses progress with the patient and family.

The role of the nursing/patient care assistant. The nursing assistant is responsible for implementing elements of the plan, such as activities of daily living, getting out of bed, and ambulation, under the guidance of the nurse. The nursing assistant reports patient responses to activity level and reflects mobility goals back to the patient verbally and through white board messaging.

Patient progress in mobility. When a patient sustains progress at one stage for 24 hours, the nurse aims to move the patient to the next stage by reevaluating the Barthel Index and going through the same steps as those followed during the initial scoring. The process moves the patient to higher activity levels, unless there are intervening problems affecting mobility.

In such cases, according to the Barthel Index, the patient may remain at the same—or be moved to a lower—activity level. In practice, patients are assessed each shift, and those with higher function (stage 3) are progressed to unsupervised ambulation.

The role of physical and occupational therapy. Although the role of physical and occupational therapists in the SLUHN mobility program is well codified, it is reserved for patients with complex rehabilitation needs due to the number of patients requiring rehabilitation.

In sum, this patient mobility program–for non-ICU hospitalized patients–relies on:

- Documentation of baseline function;

- Independent scoring using the Barthel Index;

- Creation of clear roles for nursing, nursing assistants, and therapists; and

- Reevaluation of patients at regular intervals based on the Barthel Index, so that they may progress to greater activity levels (or to lower levels in the case of a setback).

A key subsequent step, an evaluation of the program’s performance in terms of readmissions, transfer rates to a skilled nursing facility, and skilled facility length of stay, has shown positive results in all three domains.

References

- Shi SL, Girrard P, Goldstein R, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities in predicting acute care readmissions in medically complex patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1688-1695.

- Dammeyer JA, Baldwin N, Packard D, et al. Mobilizing outcomes: implementation of a nurse-led multidisciplinary mobility program. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2013;36(1):109-119.

- Wood W, Tschannen D, Trotsky A, et al. A mobility program for an inpatient acute care medical unit. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(10):34-40.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65.

“I didn’t get out of bed for 10 days”

—Anonymous patient admitted to a skilled nursing facility post-hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation

Readmission penalties, “Medicare spending per beneficiary” under value-based purchasing, and the move to accountable care are propelling hospitalists to do more to ensure our patients recover well in the least restrictive setting, without returning to the hospital. As we build systems to support patient recovery, we are focused on a medical model, paying attention to managing diseases and reconciling medications. At the same time, there is a growing awareness that functional status and mobility are critical pieces of patient care during and post-hospitalization.

Regardless of principal diagnosis and comorbidities, patients’ functional mobility ultimately determines their trajectory during recovery. To illustrate the importance of functional status and outcomes, one study showed that models predicting readmission based on functional measures outperformed those based on comorbidities.1

The negative effects of hospitalization on patient mobility, and in turn, on recovery, have been recognized for a long time. Immobility is associated with functional decline, which contributes to falls, increased length of stay, delirium, loss of ability to perform activities of daily living, and loss of ambulatory independence. A number of studies have reported successful early mobility programs in critical care and surgical patients.2 Fewer have been reported in general medical patients.3 Taken together, they suggest that a program for mobilizing patients, using a team approach, is an important part of recovery during and after hospitalization.

The purpose of this column is to report the components of one healthcare system’s mobility program for general medical-surgical patients.

Early Mobility: A Case Study

St Luke’s University Health Network (SLUHN) in northeastern Pennsylvania has implemented an early mobility program as part of its broader strategy to reduce readmissions and discharge as many patients home as possible. Although the SLUHN early mobility program depends on nursing, nursing assistants, and the judicious use of therapists, physician leadership during implementation and maintenance of the program has been essential. Moreover, because the program represents a culture shift, especially for nursing, leadership and change management are crucial ingredients for success. Below are the key steps in the SLUHN early mobility program.

Establish baseline functional status. Recording baseline function is an essential first step. For patients admitted through the ED, nurses collect ambulatory status, patient needs for assistance, ambulatory aids/special equipment, and history of falls. They populate an SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) form with this information and, as part of the handoff, ensure that it is transmitted to the inpatient nurse receiving the patient.

Obtain and document Barthel Index score. SLUHN uses the Barthel Index (see Figure 1) to establish a patient’s degree of independence and need for supervision. The index is scored on a 0-100 scale, with a higher score corresponding to a greater degree of independence. SLUHN created three categories: 0-59, stage 1; 60-84, stage 2; 85-100, stage 3.

Patient mobility plan. Based on the Barthel-derived stage, a patient is assigned a mobility plan.

The role of nursing. The patient’s registered nurse is responsible for implementing the “patient mobility plan.” The nurse initiates an “interdisciplinary plan of care,” in which the mobility stage is written on the SBAR handoff report tool. The report is discussed at change of shift and at multidisciplinary rounds. Nursing also communicates the mobility plan to the nursing assistants and assigns responsibilities for the mobility plan (activities of daily living, out of bed, ambulation, and so on), including verifying documentation of daily activities and assessing the patient’s response to the activity level of the assigned stage.

Further, nursing maintains and revises the mobility status on the SBAR, updates progress toward outcomes on the care plan, consults with the physician and team regarding the discharge plan, and discusses progress with the patient and family.

The role of the nursing/patient care assistant. The nursing assistant is responsible for implementing elements of the plan, such as activities of daily living, getting out of bed, and ambulation, under the guidance of the nurse. The nursing assistant reports patient responses to activity level and reflects mobility goals back to the patient verbally and through white board messaging.

Patient progress in mobility. When a patient sustains progress at one stage for 24 hours, the nurse aims to move the patient to the next stage by reevaluating the Barthel Index and going through the same steps as those followed during the initial scoring. The process moves the patient to higher activity levels, unless there are intervening problems affecting mobility.

In such cases, according to the Barthel Index, the patient may remain at the same—or be moved to a lower—activity level. In practice, patients are assessed each shift, and those with higher function (stage 3) are progressed to unsupervised ambulation.

The role of physical and occupational therapy. Although the role of physical and occupational therapists in the SLUHN mobility program is well codified, it is reserved for patients with complex rehabilitation needs due to the number of patients requiring rehabilitation.

In sum, this patient mobility program–for non-ICU hospitalized patients–relies on:

- Documentation of baseline function;

- Independent scoring using the Barthel Index;

- Creation of clear roles for nursing, nursing assistants, and therapists; and

- Reevaluation of patients at regular intervals based on the Barthel Index, so that they may progress to greater activity levels (or to lower levels in the case of a setback).

A key subsequent step, an evaluation of the program’s performance in terms of readmissions, transfer rates to a skilled nursing facility, and skilled facility length of stay, has shown positive results in all three domains.

References

- Shi SL, Girrard P, Goldstein R, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities in predicting acute care readmissions in medically complex patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1688-1695.

- Dammeyer JA, Baldwin N, Packard D, et al. Mobilizing outcomes: implementation of a nurse-led multidisciplinary mobility program. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2013;36(1):109-119.

- Wood W, Tschannen D, Trotsky A, et al. A mobility program for an inpatient acute care medical unit. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(10):34-40.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65.

“I didn’t get out of bed for 10 days”

—Anonymous patient admitted to a skilled nursing facility post-hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation

Readmission penalties, “Medicare spending per beneficiary” under value-based purchasing, and the move to accountable care are propelling hospitalists to do more to ensure our patients recover well in the least restrictive setting, without returning to the hospital. As we build systems to support patient recovery, we are focused on a medical model, paying attention to managing diseases and reconciling medications. At the same time, there is a growing awareness that functional status and mobility are critical pieces of patient care during and post-hospitalization.

Regardless of principal diagnosis and comorbidities, patients’ functional mobility ultimately determines their trajectory during recovery. To illustrate the importance of functional status and outcomes, one study showed that models predicting readmission based on functional measures outperformed those based on comorbidities.1

The negative effects of hospitalization on patient mobility, and in turn, on recovery, have been recognized for a long time. Immobility is associated with functional decline, which contributes to falls, increased length of stay, delirium, loss of ability to perform activities of daily living, and loss of ambulatory independence. A number of studies have reported successful early mobility programs in critical care and surgical patients.2 Fewer have been reported in general medical patients.3 Taken together, they suggest that a program for mobilizing patients, using a team approach, is an important part of recovery during and after hospitalization.

The purpose of this column is to report the components of one healthcare system’s mobility program for general medical-surgical patients.

Early Mobility: A Case Study

St Luke’s University Health Network (SLUHN) in northeastern Pennsylvania has implemented an early mobility program as part of its broader strategy to reduce readmissions and discharge as many patients home as possible. Although the SLUHN early mobility program depends on nursing, nursing assistants, and the judicious use of therapists, physician leadership during implementation and maintenance of the program has been essential. Moreover, because the program represents a culture shift, especially for nursing, leadership and change management are crucial ingredients for success. Below are the key steps in the SLUHN early mobility program.

Establish baseline functional status. Recording baseline function is an essential first step. For patients admitted through the ED, nurses collect ambulatory status, patient needs for assistance, ambulatory aids/special equipment, and history of falls. They populate an SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) form with this information and, as part of the handoff, ensure that it is transmitted to the inpatient nurse receiving the patient.

Obtain and document Barthel Index score. SLUHN uses the Barthel Index (see Figure 1) to establish a patient’s degree of independence and need for supervision. The index is scored on a 0-100 scale, with a higher score corresponding to a greater degree of independence. SLUHN created three categories: 0-59, stage 1; 60-84, stage 2; 85-100, stage 3.

Patient mobility plan. Based on the Barthel-derived stage, a patient is assigned a mobility plan.

The role of nursing. The patient’s registered nurse is responsible for implementing the “patient mobility plan.” The nurse initiates an “interdisciplinary plan of care,” in which the mobility stage is written on the SBAR handoff report tool. The report is discussed at change of shift and at multidisciplinary rounds. Nursing also communicates the mobility plan to the nursing assistants and assigns responsibilities for the mobility plan (activities of daily living, out of bed, ambulation, and so on), including verifying documentation of daily activities and assessing the patient’s response to the activity level of the assigned stage.

Further, nursing maintains and revises the mobility status on the SBAR, updates progress toward outcomes on the care plan, consults with the physician and team regarding the discharge plan, and discusses progress with the patient and family.

The role of the nursing/patient care assistant. The nursing assistant is responsible for implementing elements of the plan, such as activities of daily living, getting out of bed, and ambulation, under the guidance of the nurse. The nursing assistant reports patient responses to activity level and reflects mobility goals back to the patient verbally and through white board messaging.

Patient progress in mobility. When a patient sustains progress at one stage for 24 hours, the nurse aims to move the patient to the next stage by reevaluating the Barthel Index and going through the same steps as those followed during the initial scoring. The process moves the patient to higher activity levels, unless there are intervening problems affecting mobility.

In such cases, according to the Barthel Index, the patient may remain at the same—or be moved to a lower—activity level. In practice, patients are assessed each shift, and those with higher function (stage 3) are progressed to unsupervised ambulation.

The role of physical and occupational therapy. Although the role of physical and occupational therapists in the SLUHN mobility program is well codified, it is reserved for patients with complex rehabilitation needs due to the number of patients requiring rehabilitation.

In sum, this patient mobility program–for non-ICU hospitalized patients–relies on:

- Documentation of baseline function;

- Independent scoring using the Barthel Index;

- Creation of clear roles for nursing, nursing assistants, and therapists; and

- Reevaluation of patients at regular intervals based on the Barthel Index, so that they may progress to greater activity levels (or to lower levels in the case of a setback).

A key subsequent step, an evaluation of the program’s performance in terms of readmissions, transfer rates to a skilled nursing facility, and skilled facility length of stay, has shown positive results in all three domains.

References

- Shi SL, Girrard P, Goldstein R, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities in predicting acute care readmissions in medically complex patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1688-1695.

- Dammeyer JA, Baldwin N, Packard D, et al. Mobilizing outcomes: implementation of a nurse-led multidisciplinary mobility program. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2013;36(1):109-119.

- Wood W, Tschannen D, Trotsky A, et al. A mobility program for an inpatient acute care medical unit. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(10):34-40.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65.

Younger Type 2 Diabetics Face Greater Mortality Risks

NEW YORK - People with type 2 diabetes are 15 percent more likely to die from any cause and 14 percent more likely to die from a cardiovascular cause than non-diabetics at any given time, according to data from several Swedish registries.

The rates are significantly lower than previous estimates. Fifteen years ago, research was suggesting that having diabetes doubled the risk of premature death.

But the new study also found that the risk was dramatically elevated among people whose type 2 diabetes appeared by age 54. The worse their glycemic control and the more evidence of renal problems, the higher the risk.

In contrast, by age 75, type 2 diabetes posed little additional risk for people with good control and no kidney issues, according to the results.

"The overall increased risk of 15 percent among type 2 diabetics in general is a very low figure that has not been found in earlier type 2 diabetes studies," coauthor Dr. Marcus Lind of Uddevalla Hospital said in a telephone interview.

"The other thing that was interesting is that when we looked at patients with good glycemic control and no renal complications, if they were 75 years age, they had a lower risk than those in the general population. That hasn't been shown before," he said.

"What we are seeing is, if you are younger, aggressive management makes a difference," said Dr. Robert Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer of the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved in the research. At age 75, "you don't have to worry about it as much."

The study, published in the October 29 New England Journal of Medicine, is the largest to date to look at premature death in general - and death from cardiovascular causes in particular - among people with type 2 diabetes.

It compared more than 435,000 diabetics who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years with more than 2 million matched controls who were tracked for a mean of 4.8 years. The diabetics had had glucose problems for an average of 5.7 years.

In terms of actual death rates, cardiovascular mortality during the study period was 7.9 percent for diabetics versus 6.1 percent for controls (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.14; 95 percent confidence interval: 1.13-1.15). The respective rates for death from any cause were 17.7 percent and 14.5 percent (aHR, 1.15; 95 percent CI: 1.14-1.16).

For patients under age 55 with glycated hemoglobin levels below 7.0 percent, the risk of death from any cause nearly doubled (aHR, 1.92; 95 percent CI: 1.75-2.11).

"Those who are younger than 55, those who have target glycemic control and no signs of any renal complications, they had a clearly-elevated risk," said Dr. Lind.

But for people over 75, the hazard was actually 5 percent lower than it was for people without diabetes (aHR, 0.95; 95 percent CI: 0.94-0.96).

When the research team factored in people with normoalbuminuria, the risks were slightly mitigated.

Heart attack was the most common cause of death among diabetics.

When glycated hemoglobin levels were at 9.7 percent and higher for people below age 55, the hazard of death from any cause more than quadrupled. The hazard of death from cardiovascular causes rose more than five-fold.

Once again, the danger was far less extreme for people over 75, the researchers found.

"Excess mortality in type 2 diabetes was substantially higher with worsening glycemic control, severe renal complications, impaired renal function, and younger age," they concluded.

Renal function is a key element, Dr. Ratner said.

The study "reinforces the importance of early aggressive management of diabetes in order to prevent premature death and the fact is that the prevention of renal disease is probably the most potent thing we can do to reduce cardiovascular events," he said.

Dr. Lind said the risk may appear lower in the elderly because older people with diabetes are more likely to be getting aggressive treatment for their high blood pressure and high lipid levels, therapy that other people who also have hypertension and high cholesterol levels might not be receiving.

"I think that's the reason the rates are a bit lower" for seniors, he said.

Dr. Ratner said he believes the data for older diabetics simply reflects the fact that "you're seeing the survival cohort. They've made it past the difficult time."

We're all going to die, he said. "The issue is when does it happen? With diabetes, it's happening years ahead of time - in their 50s and early 60s, more so than when they reach 75. The younger you are, the greater that risk. That's when aggressive therapy should be given."

NEW YORK - People with type 2 diabetes are 15 percent more likely to die from any cause and 14 percent more likely to die from a cardiovascular cause than non-diabetics at any given time, according to data from several Swedish registries.

The rates are significantly lower than previous estimates. Fifteen years ago, research was suggesting that having diabetes doubled the risk of premature death.

But the new study also found that the risk was dramatically elevated among people whose type 2 diabetes appeared by age 54. The worse their glycemic control and the more evidence of renal problems, the higher the risk.

In contrast, by age 75, type 2 diabetes posed little additional risk for people with good control and no kidney issues, according to the results.

"The overall increased risk of 15 percent among type 2 diabetics in general is a very low figure that has not been found in earlier type 2 diabetes studies," coauthor Dr. Marcus Lind of Uddevalla Hospital said in a telephone interview.

"The other thing that was interesting is that when we looked at patients with good glycemic control and no renal complications, if they were 75 years age, they had a lower risk than those in the general population. That hasn't been shown before," he said.

"What we are seeing is, if you are younger, aggressive management makes a difference," said Dr. Robert Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer of the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved in the research. At age 75, "you don't have to worry about it as much."

The study, published in the October 29 New England Journal of Medicine, is the largest to date to look at premature death in general - and death from cardiovascular causes in particular - among people with type 2 diabetes.

It compared more than 435,000 diabetics who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years with more than 2 million matched controls who were tracked for a mean of 4.8 years. The diabetics had had glucose problems for an average of 5.7 years.

In terms of actual death rates, cardiovascular mortality during the study period was 7.9 percent for diabetics versus 6.1 percent for controls (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.14; 95 percent confidence interval: 1.13-1.15). The respective rates for death from any cause were 17.7 percent and 14.5 percent (aHR, 1.15; 95 percent CI: 1.14-1.16).

For patients under age 55 with glycated hemoglobin levels below 7.0 percent, the risk of death from any cause nearly doubled (aHR, 1.92; 95 percent CI: 1.75-2.11).

"Those who are younger than 55, those who have target glycemic control and no signs of any renal complications, they had a clearly-elevated risk," said Dr. Lind.

But for people over 75, the hazard was actually 5 percent lower than it was for people without diabetes (aHR, 0.95; 95 percent CI: 0.94-0.96).

When the research team factored in people with normoalbuminuria, the risks were slightly mitigated.

Heart attack was the most common cause of death among diabetics.

When glycated hemoglobin levels were at 9.7 percent and higher for people below age 55, the hazard of death from any cause more than quadrupled. The hazard of death from cardiovascular causes rose more than five-fold.

Once again, the danger was far less extreme for people over 75, the researchers found.

"Excess mortality in type 2 diabetes was substantially higher with worsening glycemic control, severe renal complications, impaired renal function, and younger age," they concluded.

Renal function is a key element, Dr. Ratner said.

The study "reinforces the importance of early aggressive management of diabetes in order to prevent premature death and the fact is that the prevention of renal disease is probably the most potent thing we can do to reduce cardiovascular events," he said.

Dr. Lind said the risk may appear lower in the elderly because older people with diabetes are more likely to be getting aggressive treatment for their high blood pressure and high lipid levels, therapy that other people who also have hypertension and high cholesterol levels might not be receiving.

"I think that's the reason the rates are a bit lower" for seniors, he said.

Dr. Ratner said he believes the data for older diabetics simply reflects the fact that "you're seeing the survival cohort. They've made it past the difficult time."

We're all going to die, he said. "The issue is when does it happen? With diabetes, it's happening years ahead of time - in their 50s and early 60s, more so than when they reach 75. The younger you are, the greater that risk. That's when aggressive therapy should be given."

NEW YORK - People with type 2 diabetes are 15 percent more likely to die from any cause and 14 percent more likely to die from a cardiovascular cause than non-diabetics at any given time, according to data from several Swedish registries.

The rates are significantly lower than previous estimates. Fifteen years ago, research was suggesting that having diabetes doubled the risk of premature death.

But the new study also found that the risk was dramatically elevated among people whose type 2 diabetes appeared by age 54. The worse their glycemic control and the more evidence of renal problems, the higher the risk.

In contrast, by age 75, type 2 diabetes posed little additional risk for people with good control and no kidney issues, according to the results.

"The overall increased risk of 15 percent among type 2 diabetics in general is a very low figure that has not been found in earlier type 2 diabetes studies," coauthor Dr. Marcus Lind of Uddevalla Hospital said in a telephone interview.

"The other thing that was interesting is that when we looked at patients with good glycemic control and no renal complications, if they were 75 years age, they had a lower risk than those in the general population. That hasn't been shown before," he said.

"What we are seeing is, if you are younger, aggressive management makes a difference," said Dr. Robert Ratner, chief scientific and medical officer of the American Diabetes Association, who was not involved in the research. At age 75, "you don't have to worry about it as much."

The study, published in the October 29 New England Journal of Medicine, is the largest to date to look at premature death in general - and death from cardiovascular causes in particular - among people with type 2 diabetes.

It compared more than 435,000 diabetics who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years with more than 2 million matched controls who were tracked for a mean of 4.8 years. The diabetics had had glucose problems for an average of 5.7 years.

In terms of actual death rates, cardiovascular mortality during the study period was 7.9 percent for diabetics versus 6.1 percent for controls (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.14; 95 percent confidence interval: 1.13-1.15). The respective rates for death from any cause were 17.7 percent and 14.5 percent (aHR, 1.15; 95 percent CI: 1.14-1.16).

For patients under age 55 with glycated hemoglobin levels below 7.0 percent, the risk of death from any cause nearly doubled (aHR, 1.92; 95 percent CI: 1.75-2.11).

"Those who are younger than 55, those who have target glycemic control and no signs of any renal complications, they had a clearly-elevated risk," said Dr. Lind.

But for people over 75, the hazard was actually 5 percent lower than it was for people without diabetes (aHR, 0.95; 95 percent CI: 0.94-0.96).

When the research team factored in people with normoalbuminuria, the risks were slightly mitigated.

Heart attack was the most common cause of death among diabetics.

When glycated hemoglobin levels were at 9.7 percent and higher for people below age 55, the hazard of death from any cause more than quadrupled. The hazard of death from cardiovascular causes rose more than five-fold.

Once again, the danger was far less extreme for people over 75, the researchers found.

"Excess mortality in type 2 diabetes was substantially higher with worsening glycemic control, severe renal complications, impaired renal function, and younger age," they concluded.

Renal function is a key element, Dr. Ratner said.

The study "reinforces the importance of early aggressive management of diabetes in order to prevent premature death and the fact is that the prevention of renal disease is probably the most potent thing we can do to reduce cardiovascular events," he said.

Dr. Lind said the risk may appear lower in the elderly because older people with diabetes are more likely to be getting aggressive treatment for their high blood pressure and high lipid levels, therapy that other people who also have hypertension and high cholesterol levels might not be receiving.

"I think that's the reason the rates are a bit lower" for seniors, he said.

Dr. Ratner said he believes the data for older diabetics simply reflects the fact that "you're seeing the survival cohort. They've made it past the difficult time."

We're all going to die, he said. "The issue is when does it happen? With diabetes, it's happening years ahead of time - in their 50s and early 60s, more so than when they reach 75. The younger you are, the greater that risk. That's when aggressive therapy should be given."

Policy Changes Hospitalists May See in 2016

The year 2015 brought the repeal of the sustainable growth rate (SGR) and new rules for advanced care planning reimbursement. It saw hospitalists take the lead on improving the two-midnight rule and respond to a global infectious disease scare.

The Hospitalist caught up with Dr. Greeno, chief strategy officer at North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC Healthcare, to ask him about what he sees for the year ahead in policy.

Question: What are the biggest changes in store for 2016 that stand to impact hospitalists?

Answer: Much of it is just a magnification of the things that most hospitalists are already feeling or sensing. Clearly, there is a very solid movement toward alternative payment methodologies. BPCI (the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative) has been embraced by hospitalists and other physicians all over the country at a scale that has surprised everybody.

There is also more consolidation in the healthcare industry as a whole. Hospital organizations are getting bigger, and we’re seeing consolidation of hospitalist groups. We will see cross-integration in the healthcare system that occurs at a rapid pace: hospitals buying physician groups, health systems and providers starting health plans, health plans acquiring hospital systems. In the not-too-distant future, we are all going to be in the population health business. This is a complete realignment of the healthcare system, and we haven’t seen the half of it yet. We have to be prepared to do it all, or a very big piece of it. The good news is, we are an absolute necessity for success in the future.

Q: It’s a presidential election year. How much weight should physicians put on claims made by candidates?

A: I encourage people to be politically engaged, but I don’t think the majority of what’s happening in healthcare is being driven by politics. It’s being driven by dispassionate economic forces that aren’t going to go away, no matter who is president. We have to figure out how to care for our population more cost-effectively. The ACA (Affordable Care Act) has driven a lot of the political environment in D.C. since its passage, including a big divide between the two parties, but it’s about three things: insurance reform, expanded access, and, particularly, delivery system reform. That’s the part we really care about and can influence the most, I think. Both parties feel like the delivery system needs to be reformed. I don’t think the election will have a major impact on hospitalists and what we do.

The ACA created an environment where things moved faster, created the (CMS) Innovation Center that drives alternative payment methodologies. It created a burning platform for things that already needed to happen.

Q: Is there anything new for meaningful use/EHR in 2016?