User login

Choosing Wisely Case Competition Deadline Is September 9

Are you helping your hospital choose wisely? You could receive thousands of dollars in return for your good work in providing high-value care to hospitalized patients through SHM’s Choosing Wisely case study competition.

SHM will be awarding a total of $20,000 to hospitalists who submit winning case studies illustrating their implementation of the Choosing Wisely principles published by SHM in 2013. Grand prize winners for both adult and pediatric HM will receive $4,000 each, and three honorable mention winners in both categories will each receive $2,000.

But don’t wait long. The deadline for submissions is September 9. For information and submission forms, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Are you helping your hospital choose wisely? You could receive thousands of dollars in return for your good work in providing high-value care to hospitalized patients through SHM’s Choosing Wisely case study competition.

SHM will be awarding a total of $20,000 to hospitalists who submit winning case studies illustrating their implementation of the Choosing Wisely principles published by SHM in 2013. Grand prize winners for both adult and pediatric HM will receive $4,000 each, and three honorable mention winners in both categories will each receive $2,000.

But don’t wait long. The deadline for submissions is September 9. For information and submission forms, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

Are you helping your hospital choose wisely? You could receive thousands of dollars in return for your good work in providing high-value care to hospitalized patients through SHM’s Choosing Wisely case study competition.

SHM will be awarding a total of $20,000 to hospitalists who submit winning case studies illustrating their implementation of the Choosing Wisely principles published by SHM in 2013. Grand prize winners for both adult and pediatric HM will receive $4,000 each, and three honorable mention winners in both categories will each receive $2,000.

But don’t wait long. The deadline for submissions is September 9. For information and submission forms, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely.

TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

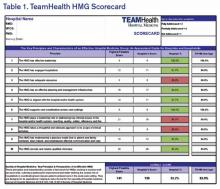

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

Deaf Hospitalist Focuses on Teaching, Co-Management, Patient-Centered Care

"What’s the bigger picture here?” Hospitalist Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP, drops his question neatly into the pause in resident Adrienne Victor, MD’s presentation of patient status and lab results.

We’re on the bustling 9th floor of University Hospital at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSCSA) in San Antonio during fast-paced morning rounds. As attending physician, Dr. Moreland is focusing intently on Dr. Victor’s face, simultaneously monitoring the American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation of Todd Agan, CI/CT, BEI Master Interpreter. Immediately after his question to Dr. Victor, the discussion—conducted in both ASL and spoken English—shifts to the patient’s psychosocial issues and whether a palliative care consult would be advisable.

It’s clear that for Dr. Moreland, the work, not his lack of hearing, is the main point here. A hospitalist with the UTHSCSA team since 2010, Dr. Moreland quickly established himself not only as a valuable HM team member and educator, but also as a leader in other domains. For example, in addition to his academic appointment as assistant clinical professor of medicine, he previously was co-director of the medicine consult and co-management service at University Hospital and now serves as UTHSCSA’s associate program director for the internal medicine residency program.

Dr. Moreland’s question this morning is typical of his teaching, says Bret Simon, PhD, an educational development specialist and assistant professor with the division of hospital medicine at UTHSCSA.

–Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP

“He’s very good at using questions to teach, promoting reflection rather than simply telling the student what to do,” Dr. Simon explains.

Why Medicine?

Chris Moreland’s parents discovered their son was deaf at age two, by which time he had acquired very few spoken words. After multiple visits to healthcare professionals, a physician finally identified his deafness. The family then embarked on a bimodal approach to his education, using both signed and spoken English. He learned ASL in college. As a result, he communicates through a variety of channels: ASL with interpreters Agan and Keri Richardson, speech reading, and spoken English. When examining patients, he uses an electronic stethoscope that interfaces with his cochlear implant.

Medicine was not Dr. Moreland’s first academic choice.

“I went into college thinking I wanted to do computer science,” he says, speaking of his undergraduate studies at the University of Texas in Austin. When he realized computers were not for him, he switched his major to theater arts, continuing an interest he had had in high school. After that, research seemed appealing, and he became a research assistant in a lab in the Department of Anthropology. Finally, after shadowing a number of physicians, his interest in medical science was stimulated.

“Medicine,” he says, “became a nice culmination of everything I was interested in doing.” From computer science, he learned to appreciate an understanding of algorithms; from theater arts came the ability to understand where people are coming from; and from his link with research in linguistics and anthropology came the contribution of problem solving and methodology.

Fearless Communicator

Dr. Moreland says his deafness presents no impediments to his practice of medicine. “I grew up working with interpreters, so I’m used to that process,” he says. “It forces you to become less inhibited about what you’re doing. People have questions [‘who is that other person in the room?’], and you learn how to handle those questions quickly, without interfering with communication in order to advance the work.”

When Dr. Moreland started his clinical rotations as a third-year medical student, he grappled with the best way to introduce himself and his interpreter to patients. His first attempt at explaining the interpretive process “went on for quite a while” and was too much information. “It ended up overwhelming the patient,” he says.

The next time he chose not to introduce the interpreter but to simply address the patient directly. “That didn’t work either, because the patient’s eyes kept wandering to that other person in the room.”

Finally, “I realized that it wasn’t about me,” he says. “It was about the patient.” So he simply shortened the introduction to himself and the interpreter and asked the patients how they were doing.

“Once I became more professional about the situation, the more positive and patient-centered it became, and it went well.” He says he’s had no negative experiences since then, at least not related to his deafness. He approaches each new patient interaction proactively, and he and his interpreters become part of the flow of care.

Teaching’s Missing Pieces

As illustrated with his first question, Dr. Moreland intends for his trainees to learn to think globally about their patients.

“Although rote information has its role,” he explains later in the conference room, “I’m always afraid of overemphasizing it. When I trained in medical school, we didn’t learn that much about communication skills and teamwork. We talked a lot about information we use as physicians—the mechanism of disease, the drugs we use.

“What I try to emphasize with trainees is, what skills in communication, teamwork, and self-education can we develop so that we can use those skills continuously throughout our practice?”

Dr. Moreland takes setting resident-generated learning goals seriously, says Dr. Simon, for which he and trainees give him high marks.

“He is very supportive and encourages us to make our own management decisions,” Dr. Victor says. “Though, of course, he will let us know if something is likely the wrong choice, usually by discussing it first.”

Patrick S. Romano, MD, MPH, professor of general medicine and pediatrics and former director of the Primary Care Outcomes Research (PCOR) faculty development program at the University of California Davis, where Dr. Moreland was a resident and then a fellow, found his trainee was always “very thoughtful and conscientious, presenting different ways of looking at problems and asking the right questions. And, of course, that’s what we look for in teachers: people who know how to ask the right questions, because, then, of course, they are able to answer students’ questions.”

Transformational and Inspirational

For many of Dr. Moreland’s colleagues and trainees, working with him has been their first exposure to a hearing-impaired physician. Richard L. Kravitz, MD, MSPH, professor and co-vice chair of research in the department of medicine at UC Davis, supervised Dr. Moreland during his residency and later during his PCOR fellowship. The American Disabilities Act-mandated interpreter for Dr. Moreland introduced a “change in standard operating procedure,” Dr. Kravitz notes. “None of us knew what to expect when he came onboard the residency program. But, very quickly, any unease was put to rest because he was just so talented.”

For visitors, Dr. Moreland seamlessly addresses his hearing impairment and makes sure that everyone on the team is following the discussion. Luci K. Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, hospital medicine division chief and associate dean for clinical affairs at UTHSCSA, says that Dr. Moreland has brought “a lot of positive energy to the group—and in ways I would not have expected.” She praised his talents as both a clinician and teacher.

John G. Rees, DBA, RN, patient care coordinator in the 5th Acute Care Unit, says that Dr. Moreland immediately “blended” with the staff on his service. “The rapport was perfect,” he adds.

Robert L. Talbert, PharmD, the SmithKline Centennial Professor of Pharmacy at the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin, often participates in teaching rounds. Dr. Moreland, he says, “has an excellent fund of knowledge; he’s very rational and evidence-based in decisions he makes. He’s exactly what a physician should be.”

Watching interpreters Agan and Richardson during group meetings, Dr. Leykum believes, has influenced their group dynamics. “On a subtle level, having Chris in the group has made us more aware of how we interact with each other.”

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM associate professor in the department of medicine and leader of ultrasound education, has noticed that he has become attuned to Dr. Moreland’s way of communicating and often does not need the interpreters to decipher the conversation between them. Working with Dr. Moreland has given Dr. Soni “a better understanding of how to communicate effectively with patients that have difficulty hearing.”

After working with Dr. Moreland at UC Davis, Dr. Kravitz observed that employing physicians with hearing impairment or other disabilities brings additional benefits to the institution. Dr. Moreland’s presence “probably raised the level of understanding of the entire internal medicine staff, because it demonstrated that a disability is what you make of it,” he says. “One recognizes how porous the barriers are, provided that people with disabilities are supported appropriately. In that way, Chris was inspiring, and may have changed the way some of us look at this specific disability that he had, but also other disabilities.”

A bigger picture, indeed.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Reference

"What’s the bigger picture here?” Hospitalist Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP, drops his question neatly into the pause in resident Adrienne Victor, MD’s presentation of patient status and lab results.

We’re on the bustling 9th floor of University Hospital at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSCSA) in San Antonio during fast-paced morning rounds. As attending physician, Dr. Moreland is focusing intently on Dr. Victor’s face, simultaneously monitoring the American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation of Todd Agan, CI/CT, BEI Master Interpreter. Immediately after his question to Dr. Victor, the discussion—conducted in both ASL and spoken English—shifts to the patient’s psychosocial issues and whether a palliative care consult would be advisable.

It’s clear that for Dr. Moreland, the work, not his lack of hearing, is the main point here. A hospitalist with the UTHSCSA team since 2010, Dr. Moreland quickly established himself not only as a valuable HM team member and educator, but also as a leader in other domains. For example, in addition to his academic appointment as assistant clinical professor of medicine, he previously was co-director of the medicine consult and co-management service at University Hospital and now serves as UTHSCSA’s associate program director for the internal medicine residency program.

Dr. Moreland’s question this morning is typical of his teaching, says Bret Simon, PhD, an educational development specialist and assistant professor with the division of hospital medicine at UTHSCSA.

–Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP

“He’s very good at using questions to teach, promoting reflection rather than simply telling the student what to do,” Dr. Simon explains.

Why Medicine?

Chris Moreland’s parents discovered their son was deaf at age two, by which time he had acquired very few spoken words. After multiple visits to healthcare professionals, a physician finally identified his deafness. The family then embarked on a bimodal approach to his education, using both signed and spoken English. He learned ASL in college. As a result, he communicates through a variety of channels: ASL with interpreters Agan and Keri Richardson, speech reading, and spoken English. When examining patients, he uses an electronic stethoscope that interfaces with his cochlear implant.

Medicine was not Dr. Moreland’s first academic choice.

“I went into college thinking I wanted to do computer science,” he says, speaking of his undergraduate studies at the University of Texas in Austin. When he realized computers were not for him, he switched his major to theater arts, continuing an interest he had had in high school. After that, research seemed appealing, and he became a research assistant in a lab in the Department of Anthropology. Finally, after shadowing a number of physicians, his interest in medical science was stimulated.

“Medicine,” he says, “became a nice culmination of everything I was interested in doing.” From computer science, he learned to appreciate an understanding of algorithms; from theater arts came the ability to understand where people are coming from; and from his link with research in linguistics and anthropology came the contribution of problem solving and methodology.

Fearless Communicator

Dr. Moreland says his deafness presents no impediments to his practice of medicine. “I grew up working with interpreters, so I’m used to that process,” he says. “It forces you to become less inhibited about what you’re doing. People have questions [‘who is that other person in the room?’], and you learn how to handle those questions quickly, without interfering with communication in order to advance the work.”

When Dr. Moreland started his clinical rotations as a third-year medical student, he grappled with the best way to introduce himself and his interpreter to patients. His first attempt at explaining the interpretive process “went on for quite a while” and was too much information. “It ended up overwhelming the patient,” he says.

The next time he chose not to introduce the interpreter but to simply address the patient directly. “That didn’t work either, because the patient’s eyes kept wandering to that other person in the room.”

Finally, “I realized that it wasn’t about me,” he says. “It was about the patient.” So he simply shortened the introduction to himself and the interpreter and asked the patients how they were doing.

“Once I became more professional about the situation, the more positive and patient-centered it became, and it went well.” He says he’s had no negative experiences since then, at least not related to his deafness. He approaches each new patient interaction proactively, and he and his interpreters become part of the flow of care.

Teaching’s Missing Pieces

As illustrated with his first question, Dr. Moreland intends for his trainees to learn to think globally about their patients.

“Although rote information has its role,” he explains later in the conference room, “I’m always afraid of overemphasizing it. When I trained in medical school, we didn’t learn that much about communication skills and teamwork. We talked a lot about information we use as physicians—the mechanism of disease, the drugs we use.

“What I try to emphasize with trainees is, what skills in communication, teamwork, and self-education can we develop so that we can use those skills continuously throughout our practice?”

Dr. Moreland takes setting resident-generated learning goals seriously, says Dr. Simon, for which he and trainees give him high marks.

“He is very supportive and encourages us to make our own management decisions,” Dr. Victor says. “Though, of course, he will let us know if something is likely the wrong choice, usually by discussing it first.”

Patrick S. Romano, MD, MPH, professor of general medicine and pediatrics and former director of the Primary Care Outcomes Research (PCOR) faculty development program at the University of California Davis, where Dr. Moreland was a resident and then a fellow, found his trainee was always “very thoughtful and conscientious, presenting different ways of looking at problems and asking the right questions. And, of course, that’s what we look for in teachers: people who know how to ask the right questions, because, then, of course, they are able to answer students’ questions.”

Transformational and Inspirational

For many of Dr. Moreland’s colleagues and trainees, working with him has been their first exposure to a hearing-impaired physician. Richard L. Kravitz, MD, MSPH, professor and co-vice chair of research in the department of medicine at UC Davis, supervised Dr. Moreland during his residency and later during his PCOR fellowship. The American Disabilities Act-mandated interpreter for Dr. Moreland introduced a “change in standard operating procedure,” Dr. Kravitz notes. “None of us knew what to expect when he came onboard the residency program. But, very quickly, any unease was put to rest because he was just so talented.”

For visitors, Dr. Moreland seamlessly addresses his hearing impairment and makes sure that everyone on the team is following the discussion. Luci K. Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, hospital medicine division chief and associate dean for clinical affairs at UTHSCSA, says that Dr. Moreland has brought “a lot of positive energy to the group—and in ways I would not have expected.” She praised his talents as both a clinician and teacher.

John G. Rees, DBA, RN, patient care coordinator in the 5th Acute Care Unit, says that Dr. Moreland immediately “blended” with the staff on his service. “The rapport was perfect,” he adds.

Robert L. Talbert, PharmD, the SmithKline Centennial Professor of Pharmacy at the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin, often participates in teaching rounds. Dr. Moreland, he says, “has an excellent fund of knowledge; he’s very rational and evidence-based in decisions he makes. He’s exactly what a physician should be.”

Watching interpreters Agan and Richardson during group meetings, Dr. Leykum believes, has influenced their group dynamics. “On a subtle level, having Chris in the group has made us more aware of how we interact with each other.”

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM associate professor in the department of medicine and leader of ultrasound education, has noticed that he has become attuned to Dr. Moreland’s way of communicating and often does not need the interpreters to decipher the conversation between them. Working with Dr. Moreland has given Dr. Soni “a better understanding of how to communicate effectively with patients that have difficulty hearing.”

After working with Dr. Moreland at UC Davis, Dr. Kravitz observed that employing physicians with hearing impairment or other disabilities brings additional benefits to the institution. Dr. Moreland’s presence “probably raised the level of understanding of the entire internal medicine staff, because it demonstrated that a disability is what you make of it,” he says. “One recognizes how porous the barriers are, provided that people with disabilities are supported appropriately. In that way, Chris was inspiring, and may have changed the way some of us look at this specific disability that he had, but also other disabilities.”

A bigger picture, indeed.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Reference

"What’s the bigger picture here?” Hospitalist Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP, drops his question neatly into the pause in resident Adrienne Victor, MD’s presentation of patient status and lab results.

We’re on the bustling 9th floor of University Hospital at the University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHSCSA) in San Antonio during fast-paced morning rounds. As attending physician, Dr. Moreland is focusing intently on Dr. Victor’s face, simultaneously monitoring the American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation of Todd Agan, CI/CT, BEI Master Interpreter. Immediately after his question to Dr. Victor, the discussion—conducted in both ASL and spoken English—shifts to the patient’s psychosocial issues and whether a palliative care consult would be advisable.

It’s clear that for Dr. Moreland, the work, not his lack of hearing, is the main point here. A hospitalist with the UTHSCSA team since 2010, Dr. Moreland quickly established himself not only as a valuable HM team member and educator, but also as a leader in other domains. For example, in addition to his academic appointment as assistant clinical professor of medicine, he previously was co-director of the medicine consult and co-management service at University Hospital and now serves as UTHSCSA’s associate program director for the internal medicine residency program.

Dr. Moreland’s question this morning is typical of his teaching, says Bret Simon, PhD, an educational development specialist and assistant professor with the division of hospital medicine at UTHSCSA.

–Christopher Moreland, MD, MPH, FACP

“He’s very good at using questions to teach, promoting reflection rather than simply telling the student what to do,” Dr. Simon explains.

Why Medicine?

Chris Moreland’s parents discovered their son was deaf at age two, by which time he had acquired very few spoken words. After multiple visits to healthcare professionals, a physician finally identified his deafness. The family then embarked on a bimodal approach to his education, using both signed and spoken English. He learned ASL in college. As a result, he communicates through a variety of channels: ASL with interpreters Agan and Keri Richardson, speech reading, and spoken English. When examining patients, he uses an electronic stethoscope that interfaces with his cochlear implant.

Medicine was not Dr. Moreland’s first academic choice.

“I went into college thinking I wanted to do computer science,” he says, speaking of his undergraduate studies at the University of Texas in Austin. When he realized computers were not for him, he switched his major to theater arts, continuing an interest he had had in high school. After that, research seemed appealing, and he became a research assistant in a lab in the Department of Anthropology. Finally, after shadowing a number of physicians, his interest in medical science was stimulated.

“Medicine,” he says, “became a nice culmination of everything I was interested in doing.” From computer science, he learned to appreciate an understanding of algorithms; from theater arts came the ability to understand where people are coming from; and from his link with research in linguistics and anthropology came the contribution of problem solving and methodology.

Fearless Communicator

Dr. Moreland says his deafness presents no impediments to his practice of medicine. “I grew up working with interpreters, so I’m used to that process,” he says. “It forces you to become less inhibited about what you’re doing. People have questions [‘who is that other person in the room?’], and you learn how to handle those questions quickly, without interfering with communication in order to advance the work.”

When Dr. Moreland started his clinical rotations as a third-year medical student, he grappled with the best way to introduce himself and his interpreter to patients. His first attempt at explaining the interpretive process “went on for quite a while” and was too much information. “It ended up overwhelming the patient,” he says.

The next time he chose not to introduce the interpreter but to simply address the patient directly. “That didn’t work either, because the patient’s eyes kept wandering to that other person in the room.”

Finally, “I realized that it wasn’t about me,” he says. “It was about the patient.” So he simply shortened the introduction to himself and the interpreter and asked the patients how they were doing.

“Once I became more professional about the situation, the more positive and patient-centered it became, and it went well.” He says he’s had no negative experiences since then, at least not related to his deafness. He approaches each new patient interaction proactively, and he and his interpreters become part of the flow of care.

Teaching’s Missing Pieces

As illustrated with his first question, Dr. Moreland intends for his trainees to learn to think globally about their patients.

“Although rote information has its role,” he explains later in the conference room, “I’m always afraid of overemphasizing it. When I trained in medical school, we didn’t learn that much about communication skills and teamwork. We talked a lot about information we use as physicians—the mechanism of disease, the drugs we use.

“What I try to emphasize with trainees is, what skills in communication, teamwork, and self-education can we develop so that we can use those skills continuously throughout our practice?”

Dr. Moreland takes setting resident-generated learning goals seriously, says Dr. Simon, for which he and trainees give him high marks.

“He is very supportive and encourages us to make our own management decisions,” Dr. Victor says. “Though, of course, he will let us know if something is likely the wrong choice, usually by discussing it first.”

Patrick S. Romano, MD, MPH, professor of general medicine and pediatrics and former director of the Primary Care Outcomes Research (PCOR) faculty development program at the University of California Davis, where Dr. Moreland was a resident and then a fellow, found his trainee was always “very thoughtful and conscientious, presenting different ways of looking at problems and asking the right questions. And, of course, that’s what we look for in teachers: people who know how to ask the right questions, because, then, of course, they are able to answer students’ questions.”

Transformational and Inspirational

For many of Dr. Moreland’s colleagues and trainees, working with him has been their first exposure to a hearing-impaired physician. Richard L. Kravitz, MD, MSPH, professor and co-vice chair of research in the department of medicine at UC Davis, supervised Dr. Moreland during his residency and later during his PCOR fellowship. The American Disabilities Act-mandated interpreter for Dr. Moreland introduced a “change in standard operating procedure,” Dr. Kravitz notes. “None of us knew what to expect when he came onboard the residency program. But, very quickly, any unease was put to rest because he was just so talented.”

For visitors, Dr. Moreland seamlessly addresses his hearing impairment and makes sure that everyone on the team is following the discussion. Luci K. Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, hospital medicine division chief and associate dean for clinical affairs at UTHSCSA, says that Dr. Moreland has brought “a lot of positive energy to the group—and in ways I would not have expected.” She praised his talents as both a clinician and teacher.

John G. Rees, DBA, RN, patient care coordinator in the 5th Acute Care Unit, says that Dr. Moreland immediately “blended” with the staff on his service. “The rapport was perfect,” he adds.

Robert L. Talbert, PharmD, the SmithKline Centennial Professor of Pharmacy at the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin, often participates in teaching rounds. Dr. Moreland, he says, “has an excellent fund of knowledge; he’s very rational and evidence-based in decisions he makes. He’s exactly what a physician should be.”

Watching interpreters Agan and Richardson during group meetings, Dr. Leykum believes, has influenced their group dynamics. “On a subtle level, having Chris in the group has made us more aware of how we interact with each other.”

Nilam Soni, MD, FHM associate professor in the department of medicine and leader of ultrasound education, has noticed that he has become attuned to Dr. Moreland’s way of communicating and often does not need the interpreters to decipher the conversation between them. Working with Dr. Moreland has given Dr. Soni “a better understanding of how to communicate effectively with patients that have difficulty hearing.”

After working with Dr. Moreland at UC Davis, Dr. Kravitz observed that employing physicians with hearing impairment or other disabilities brings additional benefits to the institution. Dr. Moreland’s presence “probably raised the level of understanding of the entire internal medicine staff, because it demonstrated that a disability is what you make of it,” he says. “One recognizes how porous the barriers are, provided that people with disabilities are supported appropriately. In that way, Chris was inspiring, and may have changed the way some of us look at this specific disability that he had, but also other disabilities.”

A bigger picture, indeed.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Reference

Hospitals Lose $45.9 Billion in Uncompensated Care in 2012

Dollar value of uncompensated care provided by U.S. hospitals in 2012, expressed in terms of actual costs, according to data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals.6 This figure represents 6.1% of total costs, an increase of 11.7% from 2011. The total includes both bad debt and charity care provided to patients unable to pay for their care, AHA says, but does not include underpayments by Medicare and Medicaid.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Dollar value of uncompensated care provided by U.S. hospitals in 2012, expressed in terms of actual costs, according to data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals.6 This figure represents 6.1% of total costs, an increase of 11.7% from 2011. The total includes both bad debt and charity care provided to patients unable to pay for their care, AHA says, but does not include underpayments by Medicare and Medicaid.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Dollar value of uncompensated care provided by U.S. hospitals in 2012, expressed in terms of actual costs, according to data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals.6 This figure represents 6.1% of total costs, an increase of 11.7% from 2011. The total includes both bad debt and charity care provided to patients unable to pay for their care, AHA says, but does not include underpayments by Medicare and Medicaid.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Health Information Technology Could Improve Hospital Discharge Planning

An RIV poster presented at SHM’s annual meeting describes the application of health information technology to improve the quality of hospital discharge summaries.4 Lead author Kristen Lewis, MD, in the clinical division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University (OSU) Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, described how SHM’s 2009 “Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement” was adopted as the medical center’s standard of care—although at baseline this standard was being fully met at the hospital only 4% of the time.5 Discharge summaries frequently lacked important information, including tests pending at discharge, and were not made available to those clinicians who needed them following discharge.

“We developed, piloted, and implemented an innovative electronic discharge summary template that incorporated prompts and automatically populated core components of a quality discharge summary,” Dr. Lewis says, adding that the process also offered opportunities for customization and free-text entries. Initial experience following a series of multidisciplinary educational initiatives to help physicians and case managers understand these mechanisms found full compliance rising to 75%.

Next steps for the project include improving the availability of discharge data for primary care providers, specialist physicians, and extended care facilities not affiliated with OSU; inclusion of the discharge summary in the “After Visit Summary” given to patients; and assessment of outpatient providers’ satisfaction with the process.

For more information about the electronic discharge template, contact Dr. Lewis at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

An RIV poster presented at SHM’s annual meeting describes the application of health information technology to improve the quality of hospital discharge summaries.4 Lead author Kristen Lewis, MD, in the clinical division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University (OSU) Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, described how SHM’s 2009 “Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement” was adopted as the medical center’s standard of care—although at baseline this standard was being fully met at the hospital only 4% of the time.5 Discharge summaries frequently lacked important information, including tests pending at discharge, and were not made available to those clinicians who needed them following discharge.

“We developed, piloted, and implemented an innovative electronic discharge summary template that incorporated prompts and automatically populated core components of a quality discharge summary,” Dr. Lewis says, adding that the process also offered opportunities for customization and free-text entries. Initial experience following a series of multidisciplinary educational initiatives to help physicians and case managers understand these mechanisms found full compliance rising to 75%.

Next steps for the project include improving the availability of discharge data for primary care providers, specialist physicians, and extended care facilities not affiliated with OSU; inclusion of the discharge summary in the “After Visit Summary” given to patients; and assessment of outpatient providers’ satisfaction with the process.

For more information about the electronic discharge template, contact Dr. Lewis at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

An RIV poster presented at SHM’s annual meeting describes the application of health information technology to improve the quality of hospital discharge summaries.4 Lead author Kristen Lewis, MD, in the clinical division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University (OSU) Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, described how SHM’s 2009 “Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement” was adopted as the medical center’s standard of care—although at baseline this standard was being fully met at the hospital only 4% of the time.5 Discharge summaries frequently lacked important information, including tests pending at discharge, and were not made available to those clinicians who needed them following discharge.

“We developed, piloted, and implemented an innovative electronic discharge summary template that incorporated prompts and automatically populated core components of a quality discharge summary,” Dr. Lewis says, adding that the process also offered opportunities for customization and free-text entries. Initial experience following a series of multidisciplinary educational initiatives to help physicians and case managers understand these mechanisms found full compliance rising to 75%.

Next steps for the project include improving the availability of discharge data for primary care providers, specialist physicians, and extended care facilities not affiliated with OSU; inclusion of the discharge summary in the “After Visit Summary” given to patients; and assessment of outpatient providers’ satisfaction with the process.

For more information about the electronic discharge template, contact Dr. Lewis at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Home Hospice Providers Offer Best Practices for End-of-Life Care

New research from the Birmingham, Ala., Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Alabama-Birmingham, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, finds that clinical techniques and care processes imported from home-based hospice professionals improved outcomes for hospitalized patients approaching the end of their lives.1

The project, conducted in six VA medical centers, employed a multi-modal strategy for improving end-of-life care processes, with staff training for all hospital providers in how to identify actively dying patients and then communicate this information to their families. Best clinical practices, supported by electronic order sets and paper-based educational materials, were implemented. Patients also were encouraged to eat what—and when—they wanted, to sit up in bed, and to receive family visitors at all hours.

“I started the project years ago, when I noticed that patients on hospice care at home often seemed more comfortable, while if I brought them into the hospital, they sometimes got worse,” says lead author F. Amos Bailey, MD. “We went out to the home to observe what the hospice nurses were doing and then came back to the hospital to write order sets to reflect that practice.”

Key quality endpoints included:

- Rates of orders for opioid pain medications;

- Anti-psychotic medications and scopolamine for death rattle;

- Completion of advance directives; and

- Consultations for palliative care and pastoral care.

Patients were more likely to have their pain relieved and symptoms addressed, according to chart reviews of 6,066 patients who died before or after the intervention was launched.

“All of the processes we measured moved in the direction of increased comfort,” Dr. Bailey says.

This is the first study to show that palliative care techniques developed in the home setting can have an impact on end-of-life care. That’s important, he adds, because most patients die in hospitals or nursing homes.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

New research from the Birmingham, Ala., Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Alabama-Birmingham, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, finds that clinical techniques and care processes imported from home-based hospice professionals improved outcomes for hospitalized patients approaching the end of their lives.1

The project, conducted in six VA medical centers, employed a multi-modal strategy for improving end-of-life care processes, with staff training for all hospital providers in how to identify actively dying patients and then communicate this information to their families. Best clinical practices, supported by electronic order sets and paper-based educational materials, were implemented. Patients also were encouraged to eat what—and when—they wanted, to sit up in bed, and to receive family visitors at all hours.

“I started the project years ago, when I noticed that patients on hospice care at home often seemed more comfortable, while if I brought them into the hospital, they sometimes got worse,” says lead author F. Amos Bailey, MD. “We went out to the home to observe what the hospice nurses were doing and then came back to the hospital to write order sets to reflect that practice.”

Key quality endpoints included:

- Rates of orders for opioid pain medications;

- Anti-psychotic medications and scopolamine for death rattle;

- Completion of advance directives; and

- Consultations for palliative care and pastoral care.

Patients were more likely to have their pain relieved and symptoms addressed, according to chart reviews of 6,066 patients who died before or after the intervention was launched.

“All of the processes we measured moved in the direction of increased comfort,” Dr. Bailey says.

This is the first study to show that palliative care techniques developed in the home setting can have an impact on end-of-life care. That’s important, he adds, because most patients die in hospitals or nursing homes.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

New research from the Birmingham, Ala., Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Alabama-Birmingham, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, finds that clinical techniques and care processes imported from home-based hospice professionals improved outcomes for hospitalized patients approaching the end of their lives.1

The project, conducted in six VA medical centers, employed a multi-modal strategy for improving end-of-life care processes, with staff training for all hospital providers in how to identify actively dying patients and then communicate this information to their families. Best clinical practices, supported by electronic order sets and paper-based educational materials, were implemented. Patients also were encouraged to eat what—and when—they wanted, to sit up in bed, and to receive family visitors at all hours.

“I started the project years ago, when I noticed that patients on hospice care at home often seemed more comfortable, while if I brought them into the hospital, they sometimes got worse,” says lead author F. Amos Bailey, MD. “We went out to the home to observe what the hospice nurses were doing and then came back to the hospital to write order sets to reflect that practice.”

Key quality endpoints included:

- Rates of orders for opioid pain medications;

- Anti-psychotic medications and scopolamine for death rattle;

- Completion of advance directives; and

- Consultations for palliative care and pastoral care.

Patients were more likely to have their pain relieved and symptoms addressed, according to chart reviews of 6,066 patients who died before or after the intervention was launched.

“All of the processes we measured moved in the direction of increased comfort,” Dr. Bailey says.

This is the first study to show that palliative care techniques developed in the home setting can have an impact on end-of-life care. That’s important, he adds, because most patients die in hospitals or nursing homes.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Bailey FA, Williams BR, Woodby LL, et al. Intervention to improve care at life's end in inpatient settings: The BEACON trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):836-843.

- Burling S. Yogurt a solution to hospital infection? Philadelphia Inquirer website. December 10, 2013. Available at: http://articles.philly.com/2013-12-10/news/44946926_1_holy-redeemer-probiotics-yogurt. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Landelle C, Verachten M, Legrand P, Girou E, Barbut F, Buisson CB. Contamination of healthcare workers’ hands with Clostridium difficile spores after caring for patients with C. difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):10-15.

- Lewis K, Walker C. Development and application of information technology solutions to improve the quality and availability of discharge summaries. Journal of Hospital Medicine RIV abstracts website. Available at: http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract.asp?MeetingID=793&id=104276&meeting=JHM201305. Published May 2013. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement. American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

- American Hospital Association: Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet. January 2014. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Three Ways to Improve Quality of Patient Care in Your Hospital

Improving the quality of care in your hospital isn’t just good for your hospital medicine group or your hospital; it’s good for the community. Each year, SHM leads some of the best quality improvement programs in healthcare, and you can get involved.

SHM is now accepting applications for the Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. An informational webinar about the program will be available on Aug. 14. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

There is still time to apply for the Project BOOST fall cohort. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Are you implementing Choosing Wisely in your hospital? You could win SHM’s Choosing Wisely competition and share your expertise with thousands of other hospitalists.

Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely to learn more.

Improving the quality of care in your hospital isn’t just good for your hospital medicine group or your hospital; it’s good for the community. Each year, SHM leads some of the best quality improvement programs in healthcare, and you can get involved.

SHM is now accepting applications for the Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. An informational webinar about the program will be available on Aug. 14. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

There is still time to apply for the Project BOOST fall cohort. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Are you implementing Choosing Wisely in your hospital? You could win SHM’s Choosing Wisely competition and share your expertise with thousands of other hospitalists.

Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely to learn more.

Improving the quality of care in your hospital isn’t just good for your hospital medicine group or your hospital; it’s good for the community. Each year, SHM leads some of the best quality improvement programs in healthcare, and you can get involved.

SHM is now accepting applications for the Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation Program. An informational webinar about the program will be available on Aug. 14. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

There is still time to apply for the Project BOOST fall cohort. For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Are you implementing Choosing Wisely in your hospital? You could win SHM’s Choosing Wisely competition and share your expertise with thousands of other hospitalists.

Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely to learn more.

Why Hospitalists Should Heed Choosing Wisely Recommendations

By now, most hospitalists are at least familiar with the Choosing Wisely campaign, which has been widely published and embraced by numerous medical societies, including the Society of Hospital Medicine.1 This campaign was conceived in 2009 by the National Physicians Alliance, which developed simple lists for three primary care specialties—internal medicine, pediatrics, and family medicine—to help them become more effective in utilizing specific resources.

The effort was first published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2011 by the “Good Stewardship Working Group,” which outlined the five most overutilized types of care by the three groups, including items such as routinely ordering complete blood counts or electrocardiograms, prescribing brand name versus generic statin drugs, and prescribing antibiotics for pediatric pharyngitis. From this small list alone, they found incredible variability among primary care practices, with utilization of these services ranging from 1% to 56% and resulting in an estimated annual cost of $6.8 billion. Although this first pilot found simple reductions in utilization can have a powerful impact on cost, the group estimated that this overutilization in primary care is only a very small fraction of overutilization cost in the U.S. As such, they called upon other specialties outside of primary care to identify their own sets of targets to reduce unnecessary utilization of low-value services.

Many specialty groups heeded this call to action, which resulted in the Choosing Wisely campaign, launched in April 2012. In just two short years, this simple effort has expanded to published recommendations about resource use in more than 60 specialty societies.2 Like the original primary care list, most recommendations have focused on overutilization of diagnostic testing (imaging, cardiac testing, labs, pathology) and medication use. Later this year, the campaign will expand to include non-physician provider organizations, including the American Dental Association, the American Physical Therapy Association, and the American Academy of Nursing.

The Next Phase

The program has evolved from asking specialty groups to develop consensus and abide by their lists to targeting patients and their families so that they can understand and abide by those same lists. In fact, one of the major aims of the campaign is empowering patients to insist on care that is evidence based, necessary, not duplicative, and more beneficial than harmful. To do this, Consumer Reports has partnered up with the Choosing Wisely campaign to develop patient-friendly educational materials and with multiple consumer groups to help these materials reach their target audience. Major funding for the project has been provided by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). So far, they have awarded 21 projects.

These grants have been awarded to medical societies (see “SHM Choosing Wisely Case Study Competition,” p. 4), regional health organizations, and consumer advocate groups. Many of the tactics will include educational campaigns to teach practitioners about the content of the recommendations, programs aimed to enhance physician communication skills geared toward practicing physicians, other educational campaigns geared toward patients and families, and the establishment of a learning network to assist practices in quickly and effectively learning from one another how to implement the various recommendations.3

The three major assets of the Choosing Wisely campaign are:

- It attacks a core issue within the medical industry: Healthcare costs are higher here than in any other industrialized nation in the world, without clear evidence of higher quality to justify that cost;

- The lists are created by those who are responsible for most of the spending; and

- The campaign is spending resources to get information to the patients and their families so that there will be bilateral exchange and acceptance of the recommendations.

Without widespread patient education, overutilization will likely continue; a recent survey sponsored by the Choosing Wisely campaign found about half of physicians admitted they would order a test they know is unnecessary if the patient is insistent.4

Variable Outcomes

While there are many reasons to celebrate the success of the campaign, there is some concern that the Choosing Wisely campaign may have unintended consequences. Although a major driver in the success of the program is the fact that the lists have been created and endorsed by physician societies, a sort of “self-governance,” with no influence or impact from payers, critics of the program note the variability that each list has on the actual practice or revenue of the physician groups enacting the lists.

For example, a recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) essay notes that the list produced by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons does not include procedures that are high volume and variably valuable (such as knee arthoplasty) but does include over-the-counter medication use and low-volume procedures (such as needle lavage for knee osteoarthritis).5 Some societies list specialty services that need to be curbed but neglect to mention their own.

And, although the campaign specifically states on its website that the “recommendations should not be used to establish coverage decisions or exclusions,” some are legitimately concerned that these Choosing Wisely lists might very well be used by payers and/or quality reporting bodies to determine payments. This is undeniably tempting: How can practitioners argue against public display and reimbursement schemes being tightly tethered to their performance on metrics that they themselves have deemed unnecessary? As the NEJM editorial summarizes, these efforts should be embraced as long as there is thoughtful discussion about inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and measurement beforehand.5

In Sum

Despite concerns, the impact of the Choosing Wisely campaign has been widespread and impressive. The full extent to which this will have an impact on utilization and healthcare cost remains to be seen, but this yeoman’s attempt to reduce waste by providers is long overdue. Whether the program will be used for unintended purposes, such as public reporting, financial penalties, or incentives for performance, is still unknown, but physician groups should be paying close attention to the lists that we can impact, and we should pledge to be good stewards of the finite healthcare resources available to our patients.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Choosing Wisely Campaign. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed May 11, 2014.

- Choosing Wisely Consumer Partners. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/partners. Access May 11, 2014.

- Choosing Wisely Grantees. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/grantees. Accessed May 11, 2014.

- Choosing Wisely & Consumer Reports. Available at: http://consumerhealthchoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ChoosingWiselyAndConsumerHealthChoices.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2014.

- Morden ME, Colla CH, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB. Choosing Wisely—the politics and economics of labeling low-value services. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1314965. Accessed May 11, 2014.

By now, most hospitalists are at least familiar with the Choosing Wisely campaign, which has been widely published and embraced by numerous medical societies, including the Society of Hospital Medicine.1 This campaign was conceived in 2009 by the National Physicians Alliance, which developed simple lists for three primary care specialties—internal medicine, pediatrics, and family medicine—to help them become more effective in utilizing specific resources.

The effort was first published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2011 by the “Good Stewardship Working Group,” which outlined the five most overutilized types of care by the three groups, including items such as routinely ordering complete blood counts or electrocardiograms, prescribing brand name versus generic statin drugs, and prescribing antibiotics for pediatric pharyngitis. From this small list alone, they found incredible variability among primary care practices, with utilization of these services ranging from 1% to 56% and resulting in an estimated annual cost of $6.8 billion. Although this first pilot found simple reductions in utilization can have a powerful impact on cost, the group estimated that this overutilization in primary care is only a very small fraction of overutilization cost in the U.S. As such, they called upon other specialties outside of primary care to identify their own sets of targets to reduce unnecessary utilization of low-value services.

Many specialty groups heeded this call to action, which resulted in the Choosing Wisely campaign, launched in April 2012. In just two short years, this simple effort has expanded to published recommendations about resource use in more than 60 specialty societies.2 Like the original primary care list, most recommendations have focused on overutilization of diagnostic testing (imaging, cardiac testing, labs, pathology) and medication use. Later this year, the campaign will expand to include non-physician provider organizations, including the American Dental Association, the American Physical Therapy Association, and the American Academy of Nursing.

The Next Phase

The program has evolved from asking specialty groups to develop consensus and abide by their lists to targeting patients and their families so that they can understand and abide by those same lists. In fact, one of the major aims of the campaign is empowering patients to insist on care that is evidence based, necessary, not duplicative, and more beneficial than harmful. To do this, Consumer Reports has partnered up with the Choosing Wisely campaign to develop patient-friendly educational materials and with multiple consumer groups to help these materials reach their target audience. Major funding for the project has been provided by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). So far, they have awarded 21 projects.