User login

Systemic trauma in the Black community: My perspective as an Asian American

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

Being a physician gives me great privilege. However, this privilege did not start the moment I donned the white coat, but when I was born Asian American, to parents who hold advanced education degrees. It grew when our family moved to a White neighborhood and I was accepted into an elite college. For medical school and residency, I chose an academic program embedded in an urban setting that serves underprivileged minority communities. I entered psychiatry to facilitate healing. Yet as I read the headlines about people of color who had died at the hands of law enforcement, I found myself feeling overwhelmingly hopeless and numb.

In these individuals, I saw people who looked and lived just like the patients I chose to serve. But during this time, I did not see myself as the healer, but part of the system that brought pain and distress. As an Asian American, I identified with Tou Thao—the Asian American police officer involved in George Floyd’s death. In the medical community with which I identified, I found that ever-rising cases of COVID-19 were disproportionately affecting lower-income minority communities. In a polarizing world, I felt my Asian American identity prevented me from experiencing the pain and suffering Black communities faced. This was not my fight, and if it was, I was more immersed in the side that brought trauma to my patients. From a purely rational perspective, I had no right to feel sad. Intellectually, I felt unqualified to share in their pain, yet here I was, crying in my room.

An evolving transformation

As much as I wanted to take a break, training did not stop. A transformation occurred from an emerging awareness of the unique environment within which I was training and the intersection of who I knew myself to be. Serving in an urban program, I was given the opportunity for candid conversations with health professionals of color. I was humbled when Black colleagues proactively reached out to educate me about the historical context of these events and help me process them. I asked hard questions of my fellow residents who were Black, and listened to their answers and personal stories, which was difficult.

With my patients, I began to listen more intently and think about the systemic issues I had previously written off. One patient missed their appointment because public transportation was closed due to COVID-19. Another patient who was homeless was helped immensely by assistance with housing when he could no longer sleep at his place of residence. Really listening to him revealed that his street had become a common route for protests. With my therapy patient who experienced panic attacks listening to the news, I simply sat and grieved with them. I chose these interactions not because I was uniquely qualified, intelligent, or had any ability to change the trajectory of our country, but because they grew from me simply working in the context I chose and seeking the relationships I naturally sought.

How I define myself

As doctors, we accept the burden of caring for society’s ailments with the ultimate hope of celebrating triumph over the adversity of psychiatric illness. However, superseding our profession is the social system in which we live. I am part of a system that has historically caused trauma to some while benefitting others. Thus, between the calling of my practice and the country I practice in, I found a divergence. Once I accepted the truth of this system and the very personal way it affects me, my colleagues, and patients I serve, I was able to internally reconcile and rediscover hope. While I cannot change my experiences, advantages, or privilege, these facts do not change the reality that I am a citizen of the globe and human first. This realization is the silver lining of these perilous times; training among people of color who graciously included me in their experiences, and my willingness to listen and self-reflect. I now choose to define myself by what makes me similar to my patients instead of what isolates me from them. The tangible results of this deliberate step toward authenticity are renewed inspiration and joy.

For those of you who may have found yourself with no “ethnic home team” (or a desire for a new one), I leave you with this simple charge: Let your emotional reactions guide you to truth, and challenge yourself to process them with someone who doesn’t look like you. Leave your title at the door and embrace humility. You might be pleasantly surprised at the human you find when you look in the mirror.

More than just 3 dogs: Is burnout getting in the way of knowing our patients?

Do you ever leave work thinking “Why do I always feel so tired after my shift?” “How can I overcome this fatigue?” “Is this what I expected?” “How can I get over the dread of so much administrative work when I want more time for my patients?” As clinicians, we face these and many other questions every day. These questions are the result of feeling entrapped in a health care system that has forgotten that clinicians need enough time to get to know and connect with their patients. Burnout is real, and relying on wellness activities is not sufficient to overcome it. Instead, taking the time for some introspection and self-reflection can help to overcome these difficulties.

A valuable lesson

Ten months into my intern year as a psychiatry resident, while on a busy night shift at the psychiatry emergency unit, an 86-year-old man arrived alone, hopeless, and with persistent death wishes. He needed to be heard and comforted by someone. Although he understood the nonnegotiable need to be hospitalized, he was extremely hesitant. But why? After all, he expressed wanting to get better and feared going back home alone, yet he was unwilling to be admitted to the hospital for acute care.

I knew I had to address the reason behind my patient’s ambivalence by further exploring his history. Nonetheless, my physician-in-training mind was battling feelings of stress secondary to what at the time seemed to be a never-ending to-do list full of nurses’ requests and patient-related tasks. Despite an unconscious temptation to rush through the history to please my go, go, go! trainee mind, I do not regret having taken the time to ask and address the often-feared “why.” Why was my patient reluctant to accept my recommendation?

To my surprise, it turned out to be an important matter. He said, “I have 3 dogs back home I don’t want to leave alone. They are the only living memory of my wife, who passed away 5 months ago. They help me stay alive.” I was struck by a feeling of empathy, but also guilt for having almost rushed through the history and not being thorough enough to ask why.

Take time to explore ‘why’

Do we really recognize the importance of being inquisitive in our history-taking? What might seem a simple matter to us (in my patient’s case, his 3 dogs were his main support system) can be a significant cause of a patient’s distress. A patients’ hesitancy to accept our recommendations can be secondary to reasons that unfortunately at times we only partially explore, or do not explore at all. Asking why can open Pandora’s box. It can uncover feelings and emotions such as frustration, anger, anxiety, and sorrow. It can also reveal uncertainties regarding topics such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and religion. We should be driven by humble curiosity, and tailor the interview by purposefully asking questions with the goal of learning and understanding our patients’ concerns. This practice serves to cultivate honest and trustworthy physician-patient relationships founded on empathy and respect.

If we know that obtaining an in-depth history is crucial for formulating a patient’s treatment plan, why do we sometimes fall in the trap of obtaining superficial ones, at times limiting ourselves to checklists? Reasons for not delving into our patients’ histories include (but are not limited to) an overload of patients, time constraints, a physician’s personal style, unconscious bias, suboptimal mentoring, and burnout. Of all these reasons, I worry the most about burnout. Physicians face insurmountable academic, institutional, and administrative demands. These constraints inarguably contribute to feeling rushed, and eventually possibly burned out.

Using self-reflection to prevent burnout

Physician burnout—as well as attempts to define, identify, target, and prevent it—has been on the rise in the past decades. If burnout affects the physician-patient relationship, we should make efforts to mitigate it. One should try to rely on internal, rather than external, influences to positively influence our delivery of care. One way to do this is by really getting to know the patient in front of us: a father, mother, brother, sister, member of the community, etc. Understanding our patient’s needs and concerns promotes empathy and connectedness. Another way is to exercise self-reflection by asking ourselves: How do I feel about the care I delivered today? Did I make an effort to fully understand my patients’ concerns? Did I make each patient feel understood? Was I rushing through the day, or was I mindful of the person in front of me? Did I deliver the care I wish I had received?

Although there are innumerable ways to target physician burnout, these self-reflections are quick, simple exercises that easily can be woven into a clinician’s busy schedule. The goal is to be mindful of improving the quality of our interactions with patients to ultimately cultivate our own well-being by potentiating a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction with our profession. I encourage clinicians to always go after the “why.” After all, why not? Thankfully, after some persuasion, my patient accepted voluntary admission, and arranged with neighbors to take care of his 3 dogs.

Do you ever leave work thinking “Why do I always feel so tired after my shift?” “How can I overcome this fatigue?” “Is this what I expected?” “How can I get over the dread of so much administrative work when I want more time for my patients?” As clinicians, we face these and many other questions every day. These questions are the result of feeling entrapped in a health care system that has forgotten that clinicians need enough time to get to know and connect with their patients. Burnout is real, and relying on wellness activities is not sufficient to overcome it. Instead, taking the time for some introspection and self-reflection can help to overcome these difficulties.

A valuable lesson

Ten months into my intern year as a psychiatry resident, while on a busy night shift at the psychiatry emergency unit, an 86-year-old man arrived alone, hopeless, and with persistent death wishes. He needed to be heard and comforted by someone. Although he understood the nonnegotiable need to be hospitalized, he was extremely hesitant. But why? After all, he expressed wanting to get better and feared going back home alone, yet he was unwilling to be admitted to the hospital for acute care.

I knew I had to address the reason behind my patient’s ambivalence by further exploring his history. Nonetheless, my physician-in-training mind was battling feelings of stress secondary to what at the time seemed to be a never-ending to-do list full of nurses’ requests and patient-related tasks. Despite an unconscious temptation to rush through the history to please my go, go, go! trainee mind, I do not regret having taken the time to ask and address the often-feared “why.” Why was my patient reluctant to accept my recommendation?

To my surprise, it turned out to be an important matter. He said, “I have 3 dogs back home I don’t want to leave alone. They are the only living memory of my wife, who passed away 5 months ago. They help me stay alive.” I was struck by a feeling of empathy, but also guilt for having almost rushed through the history and not being thorough enough to ask why.

Take time to explore ‘why’

Do we really recognize the importance of being inquisitive in our history-taking? What might seem a simple matter to us (in my patient’s case, his 3 dogs were his main support system) can be a significant cause of a patient’s distress. A patients’ hesitancy to accept our recommendations can be secondary to reasons that unfortunately at times we only partially explore, or do not explore at all. Asking why can open Pandora’s box. It can uncover feelings and emotions such as frustration, anger, anxiety, and sorrow. It can also reveal uncertainties regarding topics such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and religion. We should be driven by humble curiosity, and tailor the interview by purposefully asking questions with the goal of learning and understanding our patients’ concerns. This practice serves to cultivate honest and trustworthy physician-patient relationships founded on empathy and respect.

If we know that obtaining an in-depth history is crucial for formulating a patient’s treatment plan, why do we sometimes fall in the trap of obtaining superficial ones, at times limiting ourselves to checklists? Reasons for not delving into our patients’ histories include (but are not limited to) an overload of patients, time constraints, a physician’s personal style, unconscious bias, suboptimal mentoring, and burnout. Of all these reasons, I worry the most about burnout. Physicians face insurmountable academic, institutional, and administrative demands. These constraints inarguably contribute to feeling rushed, and eventually possibly burned out.

Using self-reflection to prevent burnout

Physician burnout—as well as attempts to define, identify, target, and prevent it—has been on the rise in the past decades. If burnout affects the physician-patient relationship, we should make efforts to mitigate it. One should try to rely on internal, rather than external, influences to positively influence our delivery of care. One way to do this is by really getting to know the patient in front of us: a father, mother, brother, sister, member of the community, etc. Understanding our patient’s needs and concerns promotes empathy and connectedness. Another way is to exercise self-reflection by asking ourselves: How do I feel about the care I delivered today? Did I make an effort to fully understand my patients’ concerns? Did I make each patient feel understood? Was I rushing through the day, or was I mindful of the person in front of me? Did I deliver the care I wish I had received?

Although there are innumerable ways to target physician burnout, these self-reflections are quick, simple exercises that easily can be woven into a clinician’s busy schedule. The goal is to be mindful of improving the quality of our interactions with patients to ultimately cultivate our own well-being by potentiating a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction with our profession. I encourage clinicians to always go after the “why.” After all, why not? Thankfully, after some persuasion, my patient accepted voluntary admission, and arranged with neighbors to take care of his 3 dogs.

Do you ever leave work thinking “Why do I always feel so tired after my shift?” “How can I overcome this fatigue?” “Is this what I expected?” “How can I get over the dread of so much administrative work when I want more time for my patients?” As clinicians, we face these and many other questions every day. These questions are the result of feeling entrapped in a health care system that has forgotten that clinicians need enough time to get to know and connect with their patients. Burnout is real, and relying on wellness activities is not sufficient to overcome it. Instead, taking the time for some introspection and self-reflection can help to overcome these difficulties.

A valuable lesson

Ten months into my intern year as a psychiatry resident, while on a busy night shift at the psychiatry emergency unit, an 86-year-old man arrived alone, hopeless, and with persistent death wishes. He needed to be heard and comforted by someone. Although he understood the nonnegotiable need to be hospitalized, he was extremely hesitant. But why? After all, he expressed wanting to get better and feared going back home alone, yet he was unwilling to be admitted to the hospital for acute care.

I knew I had to address the reason behind my patient’s ambivalence by further exploring his history. Nonetheless, my physician-in-training mind was battling feelings of stress secondary to what at the time seemed to be a never-ending to-do list full of nurses’ requests and patient-related tasks. Despite an unconscious temptation to rush through the history to please my go, go, go! trainee mind, I do not regret having taken the time to ask and address the often-feared “why.” Why was my patient reluctant to accept my recommendation?

To my surprise, it turned out to be an important matter. He said, “I have 3 dogs back home I don’t want to leave alone. They are the only living memory of my wife, who passed away 5 months ago. They help me stay alive.” I was struck by a feeling of empathy, but also guilt for having almost rushed through the history and not being thorough enough to ask why.

Take time to explore ‘why’

Do we really recognize the importance of being inquisitive in our history-taking? What might seem a simple matter to us (in my patient’s case, his 3 dogs were his main support system) can be a significant cause of a patient’s distress. A patients’ hesitancy to accept our recommendations can be secondary to reasons that unfortunately at times we only partially explore, or do not explore at all. Asking why can open Pandora’s box. It can uncover feelings and emotions such as frustration, anger, anxiety, and sorrow. It can also reveal uncertainties regarding topics such as race, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and religion. We should be driven by humble curiosity, and tailor the interview by purposefully asking questions with the goal of learning and understanding our patients’ concerns. This practice serves to cultivate honest and trustworthy physician-patient relationships founded on empathy and respect.

If we know that obtaining an in-depth history is crucial for formulating a patient’s treatment plan, why do we sometimes fall in the trap of obtaining superficial ones, at times limiting ourselves to checklists? Reasons for not delving into our patients’ histories include (but are not limited to) an overload of patients, time constraints, a physician’s personal style, unconscious bias, suboptimal mentoring, and burnout. Of all these reasons, I worry the most about burnout. Physicians face insurmountable academic, institutional, and administrative demands. These constraints inarguably contribute to feeling rushed, and eventually possibly burned out.

Using self-reflection to prevent burnout

Physician burnout—as well as attempts to define, identify, target, and prevent it—has been on the rise in the past decades. If burnout affects the physician-patient relationship, we should make efforts to mitigate it. One should try to rely on internal, rather than external, influences to positively influence our delivery of care. One way to do this is by really getting to know the patient in front of us: a father, mother, brother, sister, member of the community, etc. Understanding our patient’s needs and concerns promotes empathy and connectedness. Another way is to exercise self-reflection by asking ourselves: How do I feel about the care I delivered today? Did I make an effort to fully understand my patients’ concerns? Did I make each patient feel understood? Was I rushing through the day, or was I mindful of the person in front of me? Did I deliver the care I wish I had received?

Although there are innumerable ways to target physician burnout, these self-reflections are quick, simple exercises that easily can be woven into a clinician’s busy schedule. The goal is to be mindful of improving the quality of our interactions with patients to ultimately cultivate our own well-being by potentiating a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction with our profession. I encourage clinicians to always go after the “why.” After all, why not? Thankfully, after some persuasion, my patient accepted voluntary admission, and arranged with neighbors to take care of his 3 dogs.

A resident’s guide to lithium

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

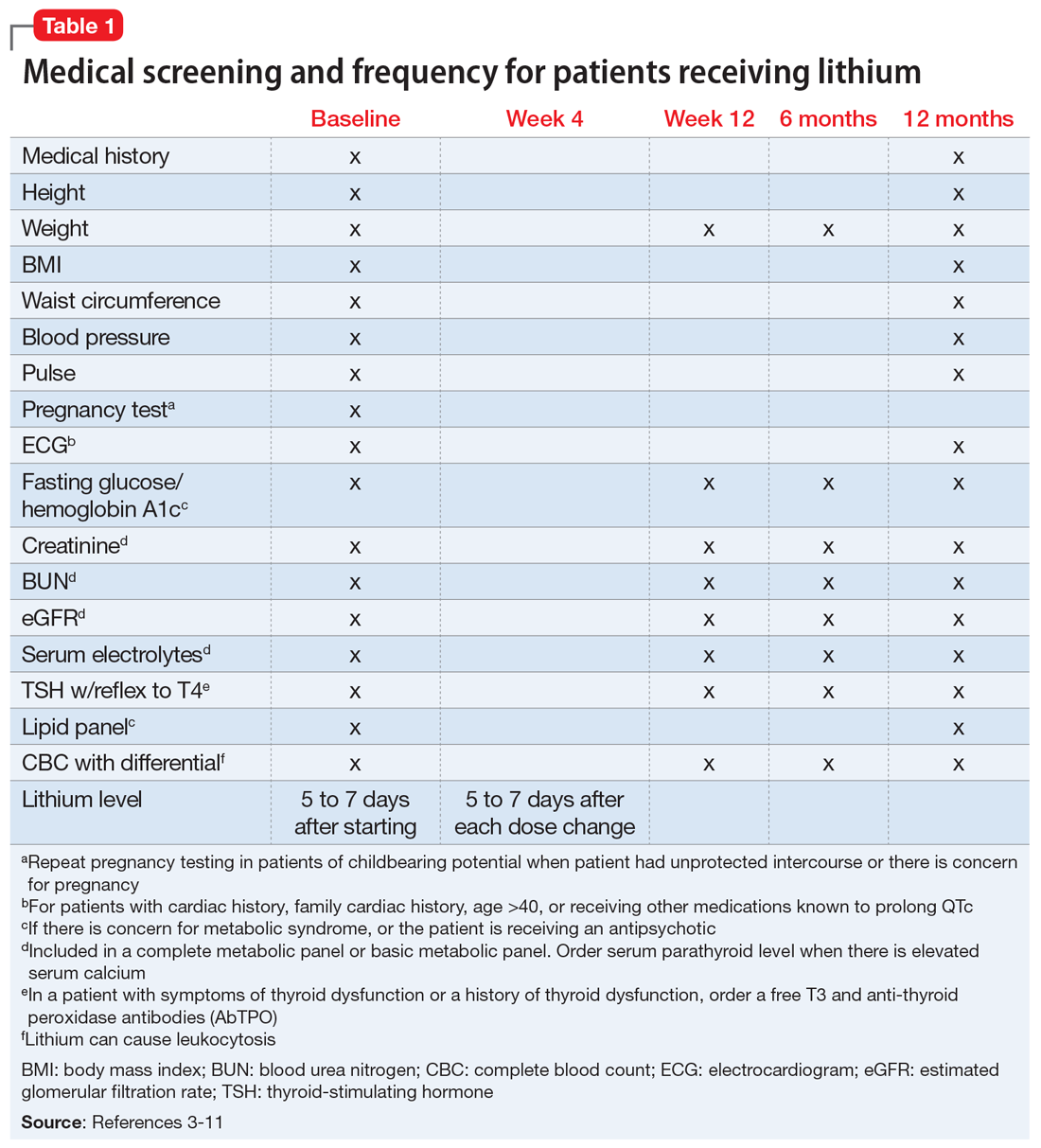

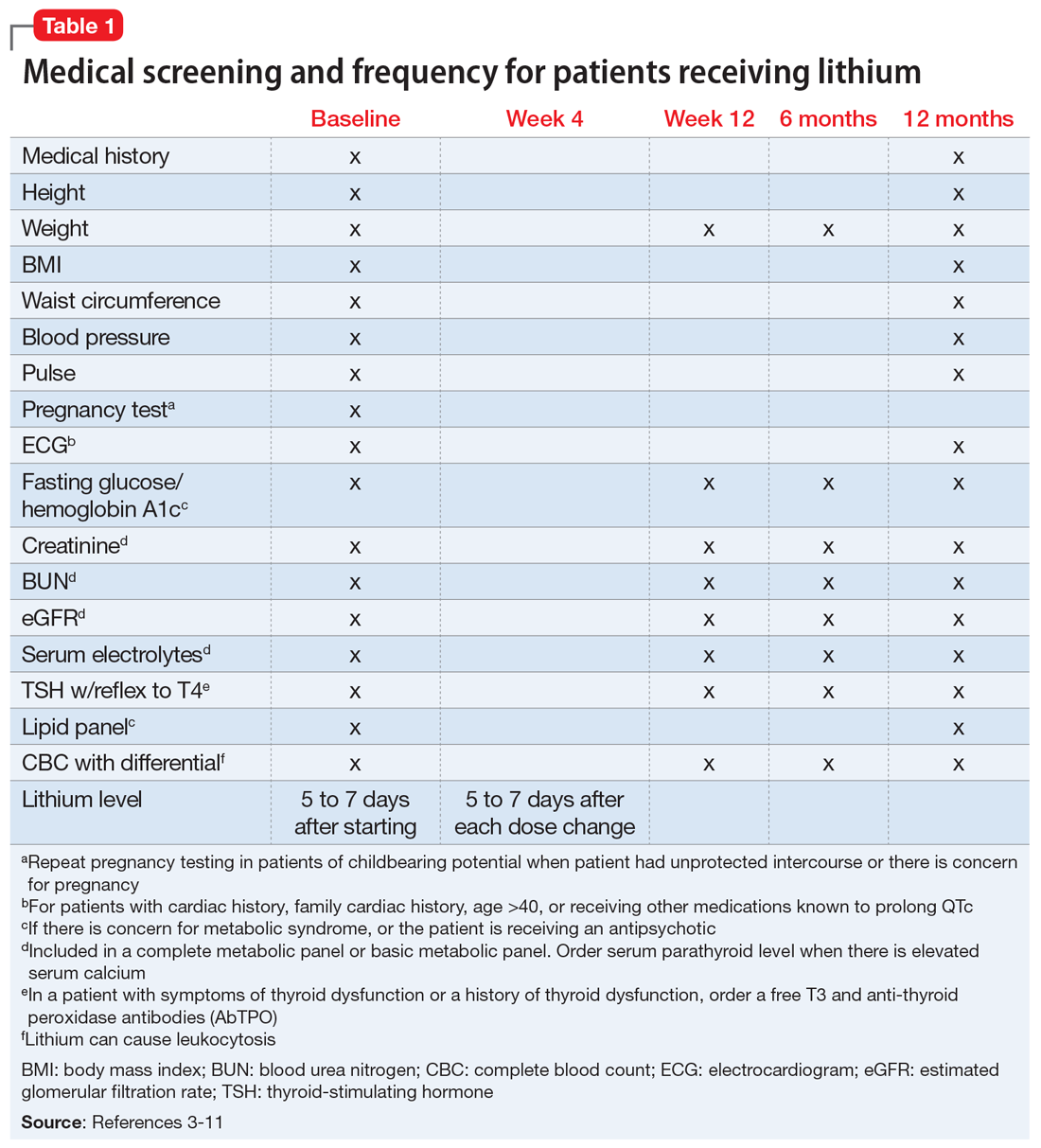

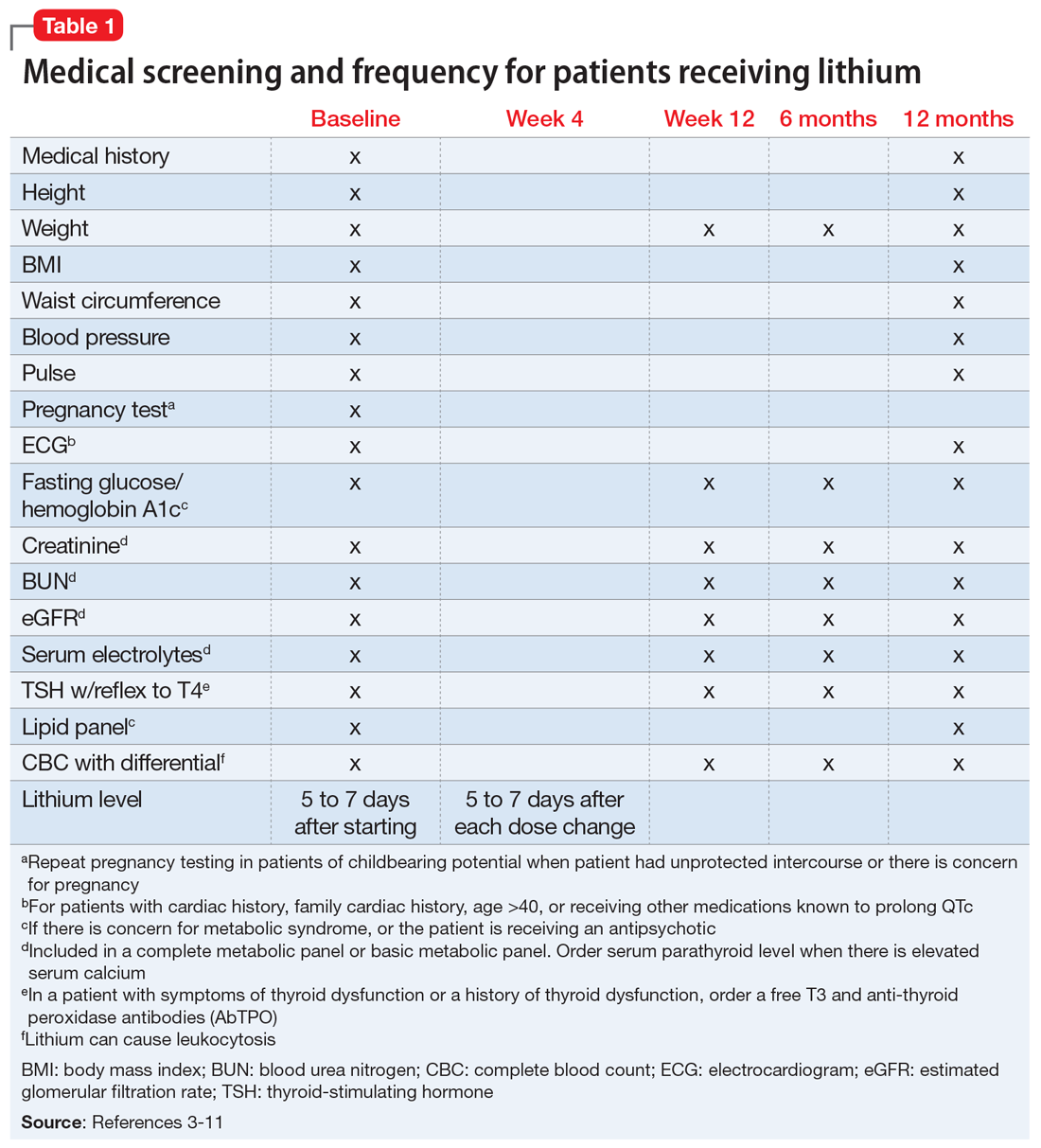

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Virtual supervision during the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has fundamentally changed our way of life. It has affected everything from how we go to the grocery store, attend school, worship, and spend time with our loved ones. As vaccinations are becoming available, there’s hope for a time when we can all enjoy a mask-free life again. Despite this, many of us are beginning to sense that the precautions and technology employed in response to COVID-19, and some of the lessons learned as a result, are likely to stay in place long after the virus has been controlled.

Working remotely through audio and visual synchronous communication is now becoming the norm throughout the American workplace and educational system. Hospitals and graduate medical education programs are not exempt from this trend. For at least the foreseeable future, gone are the days of “unsocially distanced” bedside rounds in which 5 to 10 residents and medical students gather around with their attending as a case is presented in front of an agreeable patient.

My experience with ‘virtual’ supervision

Telemedicine has played a key role in the practice of health care during this pandemic, but little has been written about “telesupervision” of residents in the hospital setting. An unprecedented virtual approach to supervising emergency medicine residents was trialed at the University of Alabama a few months prior to my experience with it. This was found to be quite effective and well-received by all involved parties.1

I am a PGY-2 psychiatry resident at ChristianaCare, a large multisite hospital system with more than 1,200 beds that serves the health care needs of Delaware and the surrounding areas. I recently had a novel educational experience working on a busy addiction medicine consult service. On the first day of this rotation, I met with my attending, Dr. Terry Horton, to discuss how the month would proceed. Together we developed a strategy for him to supervise me virtually.

Our arrangement was efficient and simple: I began each day by donning my surgical mask and protective eyewear and reviewing patients that had been placed on the consult list. Dr. Horton and I would have a conversation via telephone early in the morning to discuss the tasks that needed to be completed for the day. I would see and evaluate patients in the standard face-to-face way. After developing a treatment strategy, I contacted Dr. Horton on the phone, presented the patient, shared my plan, and gained information from his experienced perspective.

Then we saw the patient “together.” We used an iPad and Microsoft Teams video conferencing software. The information shared was protected using Microsoft Teams accounts, which were secured with profiles created by our institutional accounts. The iPad was placed on a rolling tripod, and the patient was able to converse with Dr. Horton as though he was physically in the room. I was there to facilitate the call, address any technical issues, and conduct any aspects of a physical exam that could only be done in person. After discussing any other changes to the treatment plan, I placed all medication orders, shared relevant details with nursing staff and other clinicians, wrote my progress note, and rolled my “attending on a stick” over to the next patient. Meanwhile, Dr. Horton was free to respond to pages or any other issues while I worked.

This description of my workflow is not very different from life before the virus. Based on informal feedback gathered from patients, the experience was overall positive. A physician is present; patients feel well cared for, and they look forward to visits and a virtual presence. This virtual approach not only spared unnecessary physical contact, reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure, it also promoted efficiency.

Continue to: Fortunately, our hospital...

Fortunately, our hospital is surrounded by a solid telecommunications infrastructure. This experience would be limited in more remote areas of the country. At times, sound quality was an issue, which can be especially problematic for certain patients.

Certain psychosocial implications of the pandemic, including (but not limited to)social isolation and financial hardship, are often associated with increased substance use, and early data support the hypothesis that substance use has increased during this period.2 Delaware seems to be included in the national trend. As such, our already-busy service is being stretched even further. Dr. Horton receives calls and is providing critical recommendations continuously throughout the day for multiple hospitals as well as for his outpatient practice. He used to spend a great deal of time traveling between different sites. With increasing need for his expertise, this model became increasingly difficult to practice. Our new model of attending supervision is welcomed in some settings because the attending can virtually be in multiple places at the same time.

For me, this experience has been positive. For a physician in training, virtual rounding can provide a critical balance of autonomy and support. I felt free on the rotation to make my own decisions, but I also did not feel like I was left to care for complicated cases on my own. Furthermore, my education did not suffer. In actuality, the experience enabled me to excel in my training. An attending physician was there for the important steps of plan formulation, but solo problem-solving opportunities were more readily available without his physical presence.

Aside from the medical lessons learned, I believe the participation has given me a glimpse of the future of medical training, health care delivery, and life in the increasingly digital post−COVID-19 world.

Hopefully, my experience will be helpful for other hospital systems as they continue to provide high-quality care to patients and education/training to their resident physicians in the face of the pandemic and the changing landscape of health care.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Mustafa Mufti, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Program Director; Rachel Bronsther, MD, ChristianaCare Psychiatry Residency Associate Program Director; and Terry Horton, MD, ChristianaCare Addiction Medicine, for their assistance with this article.

1. Schrading WA, Pigott D, Thompson L. Virtual remote attending supervision in an academic emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):266-269.

2. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has fundamentally changed our way of life. It has affected everything from how we go to the grocery store, attend school, worship, and spend time with our loved ones. As vaccinations are becoming available, there’s hope for a time when we can all enjoy a mask-free life again. Despite this, many of us are beginning to sense that the precautions and technology employed in response to COVID-19, and some of the lessons learned as a result, are likely to stay in place long after the virus has been controlled.

Working remotely through audio and visual synchronous communication is now becoming the norm throughout the American workplace and educational system. Hospitals and graduate medical education programs are not exempt from this trend. For at least the foreseeable future, gone are the days of “unsocially distanced” bedside rounds in which 5 to 10 residents and medical students gather around with their attending as a case is presented in front of an agreeable patient.

My experience with ‘virtual’ supervision

Telemedicine has played a key role in the practice of health care during this pandemic, but little has been written about “telesupervision” of residents in the hospital setting. An unprecedented virtual approach to supervising emergency medicine residents was trialed at the University of Alabama a few months prior to my experience with it. This was found to be quite effective and well-received by all involved parties.1