User login

Cost-conscious minimally invasive hysterectomy: A case illustration

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

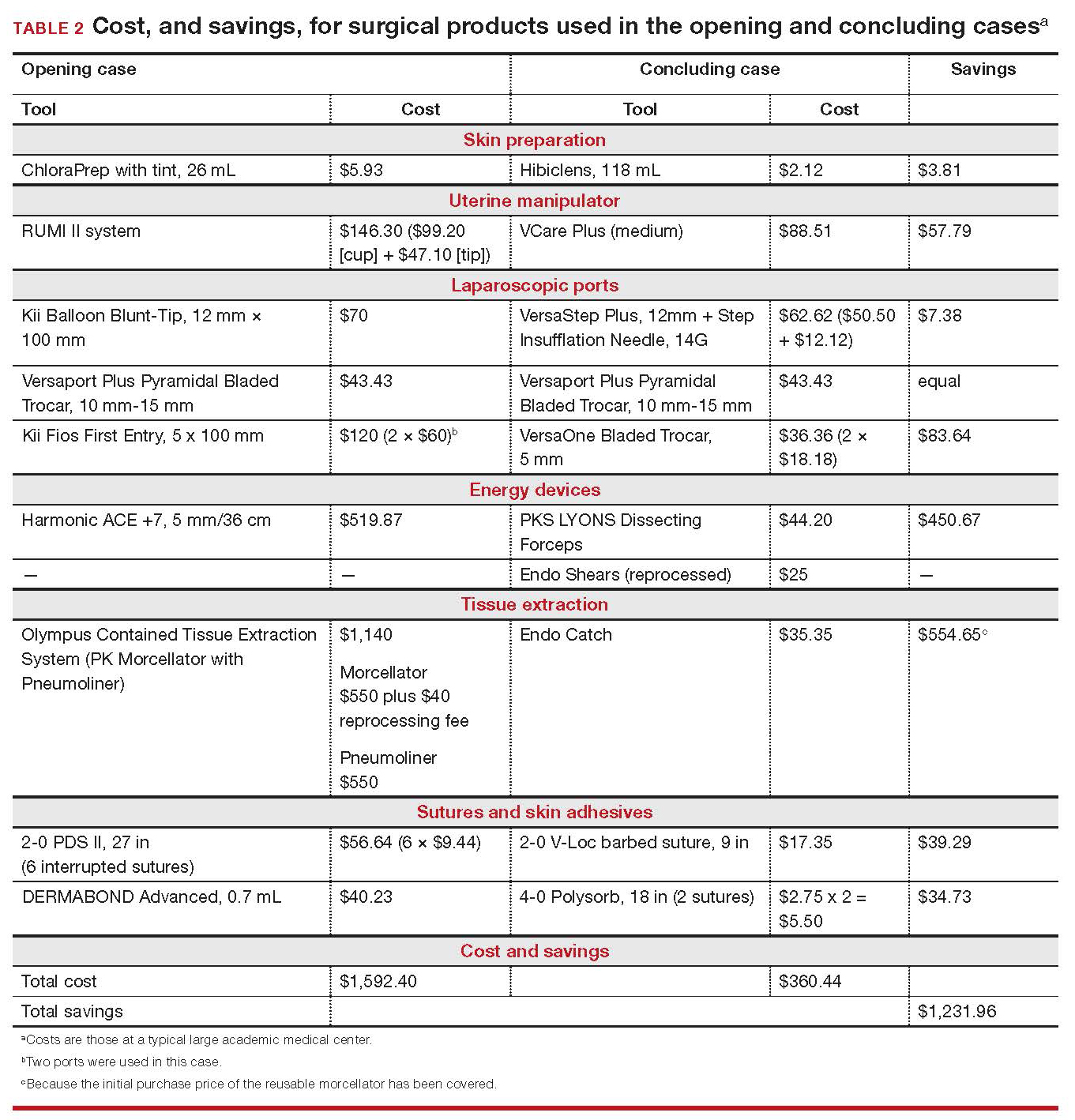

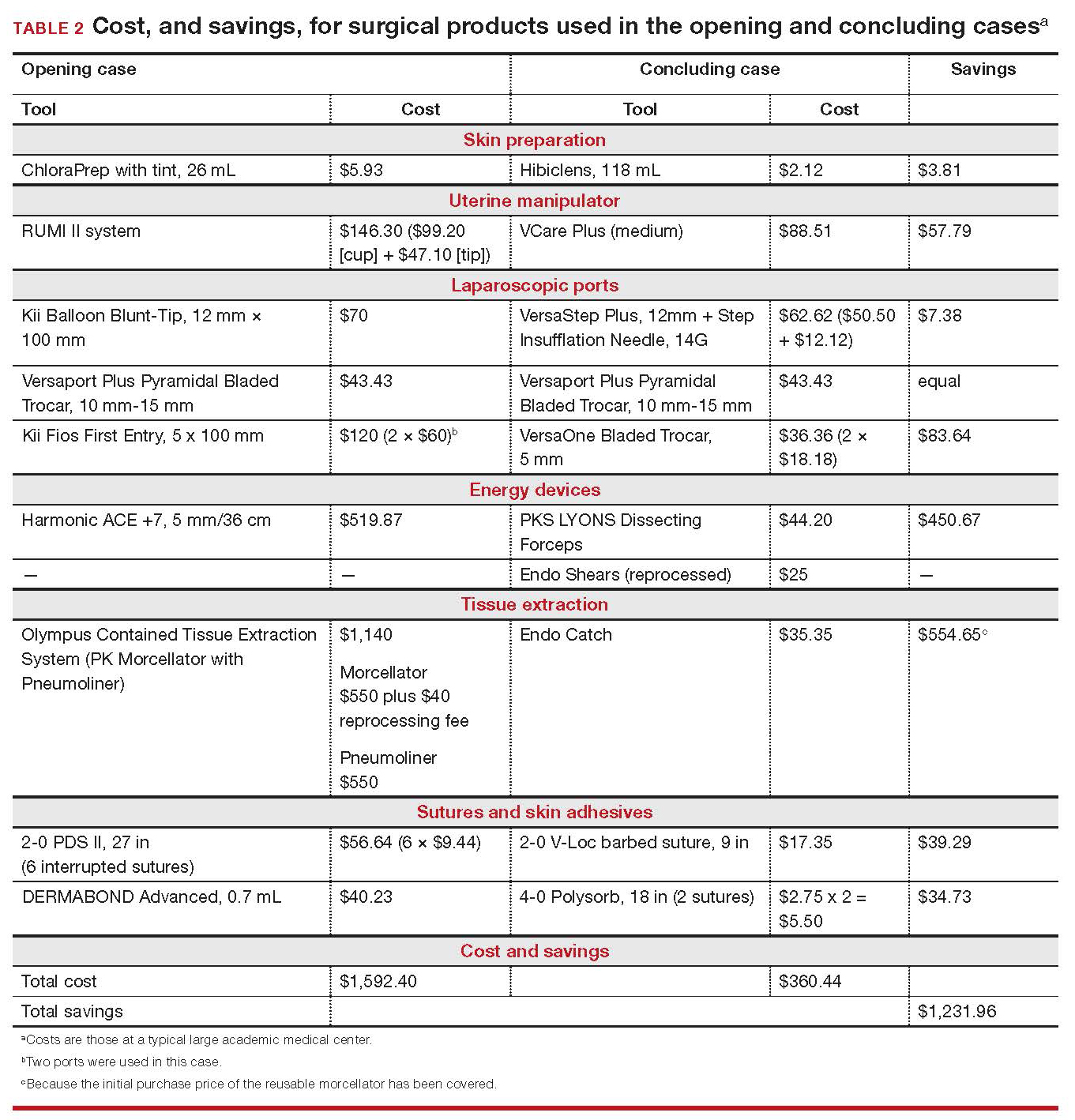

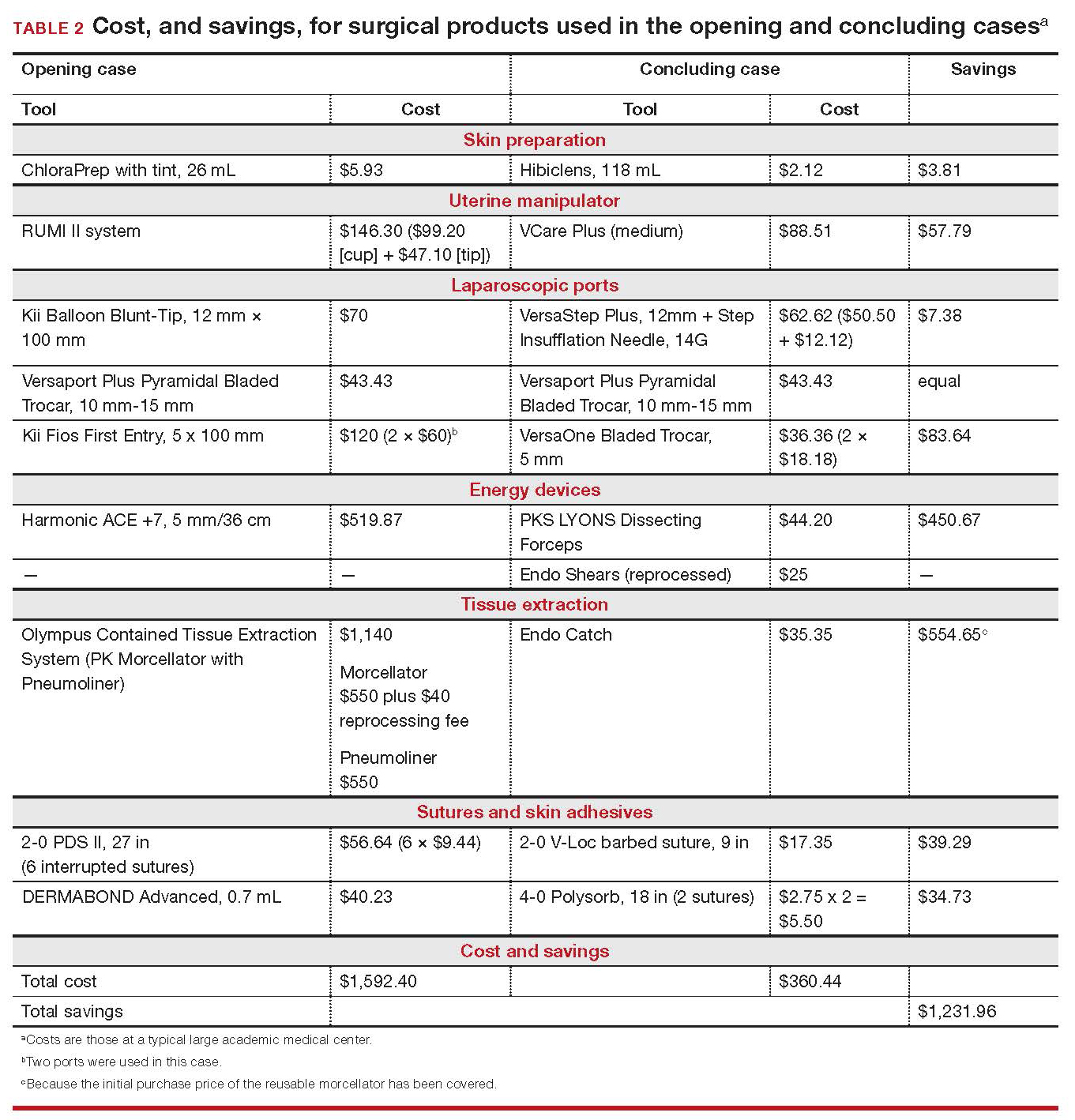

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

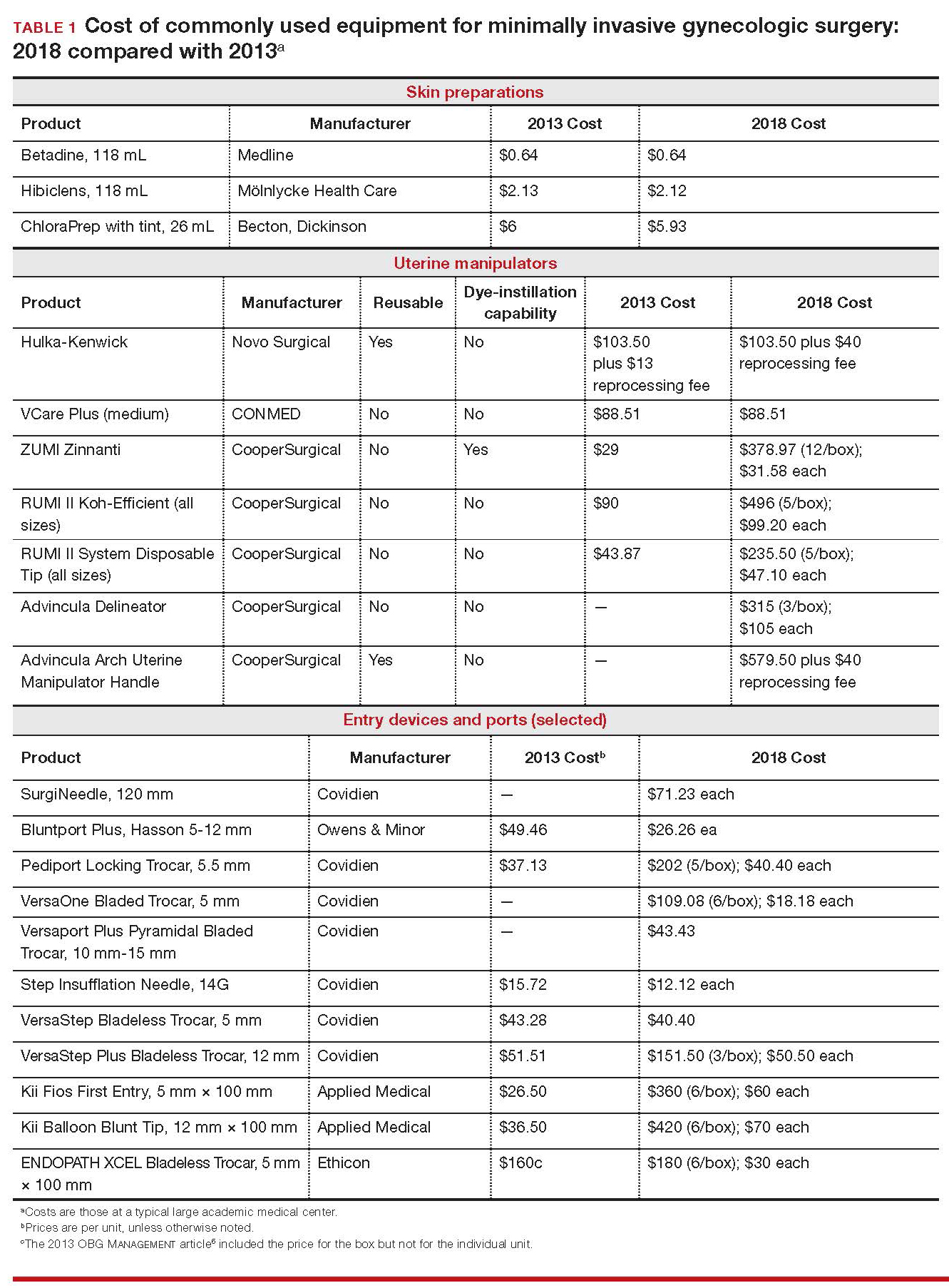

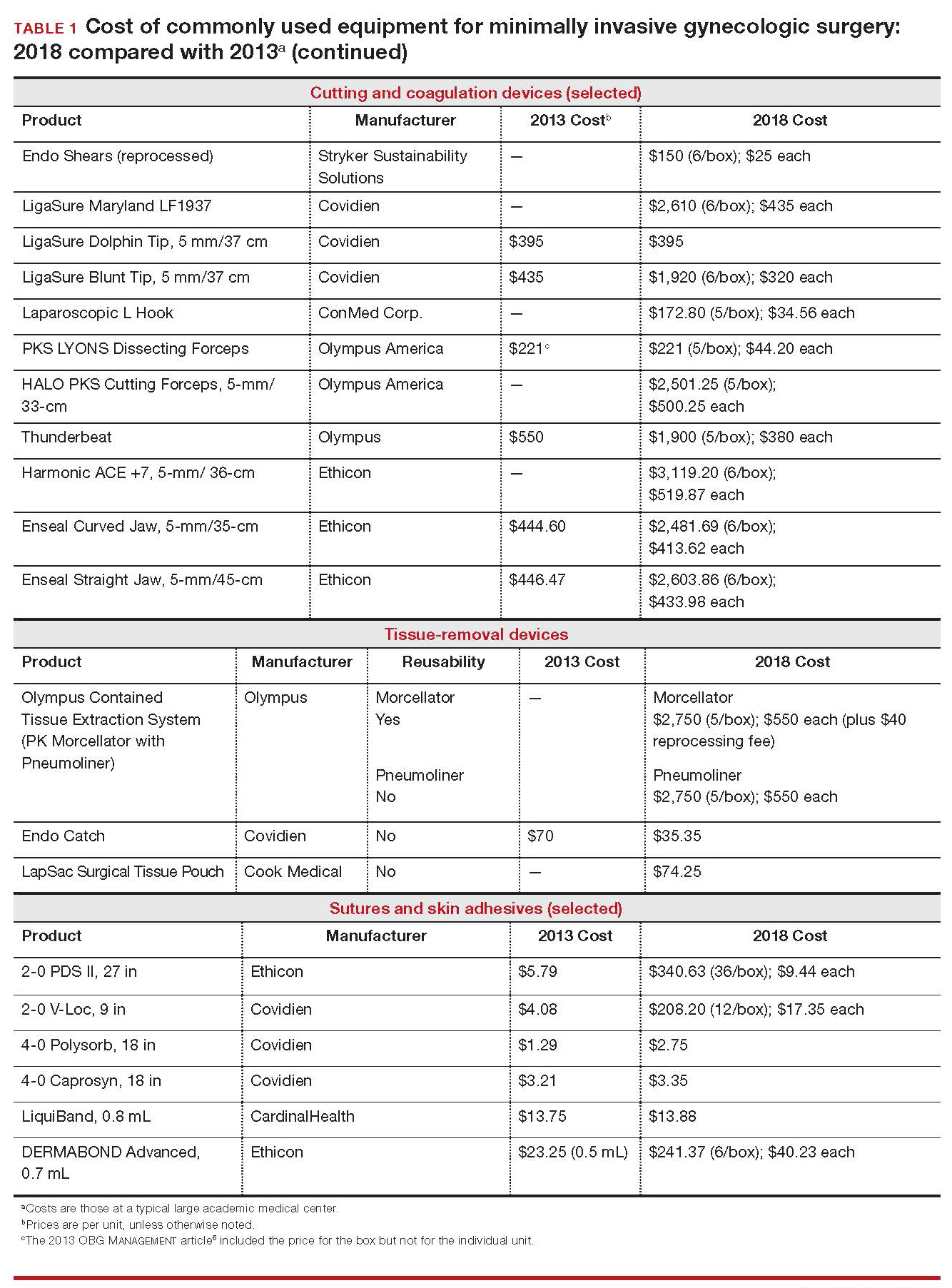

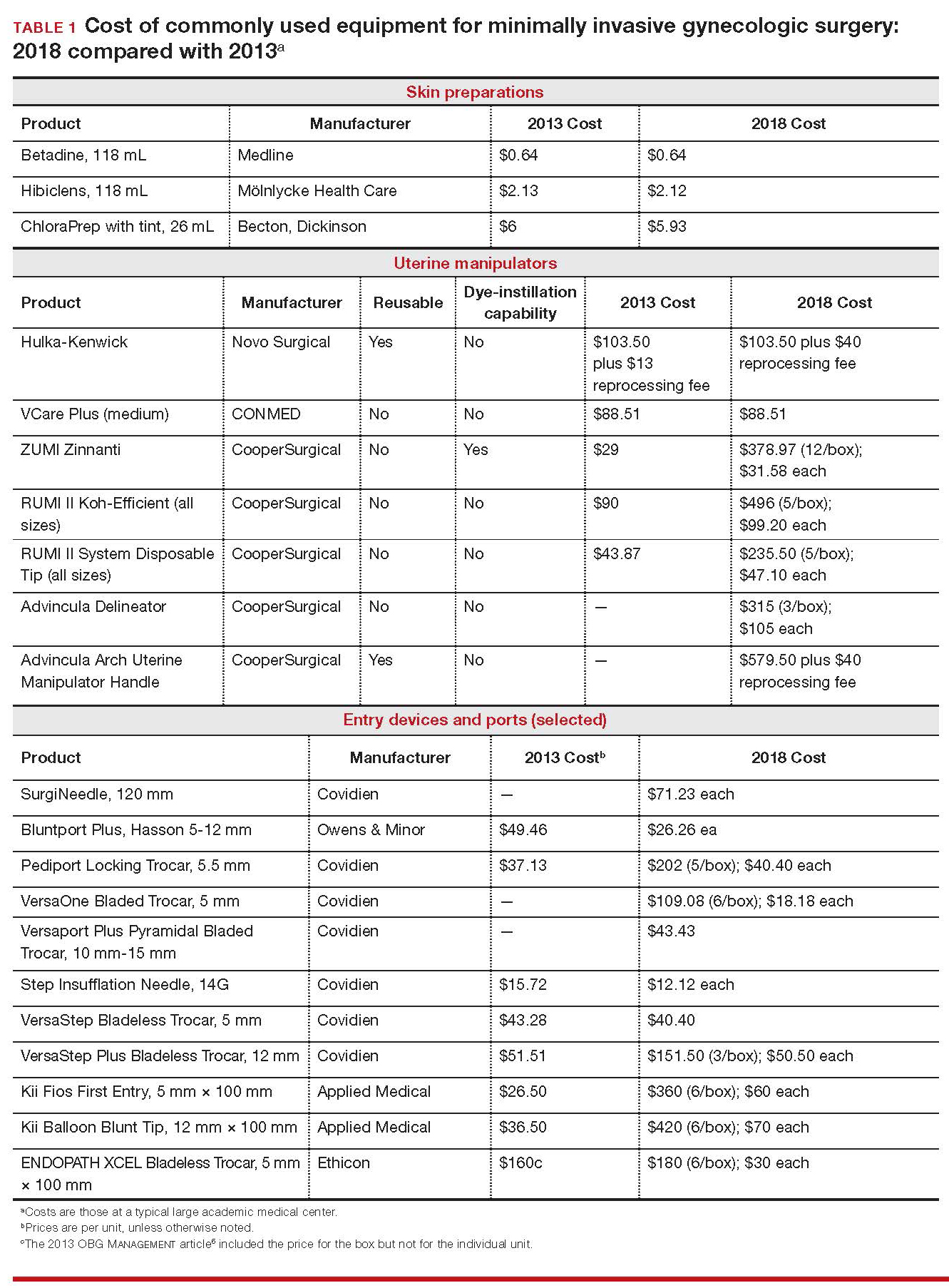

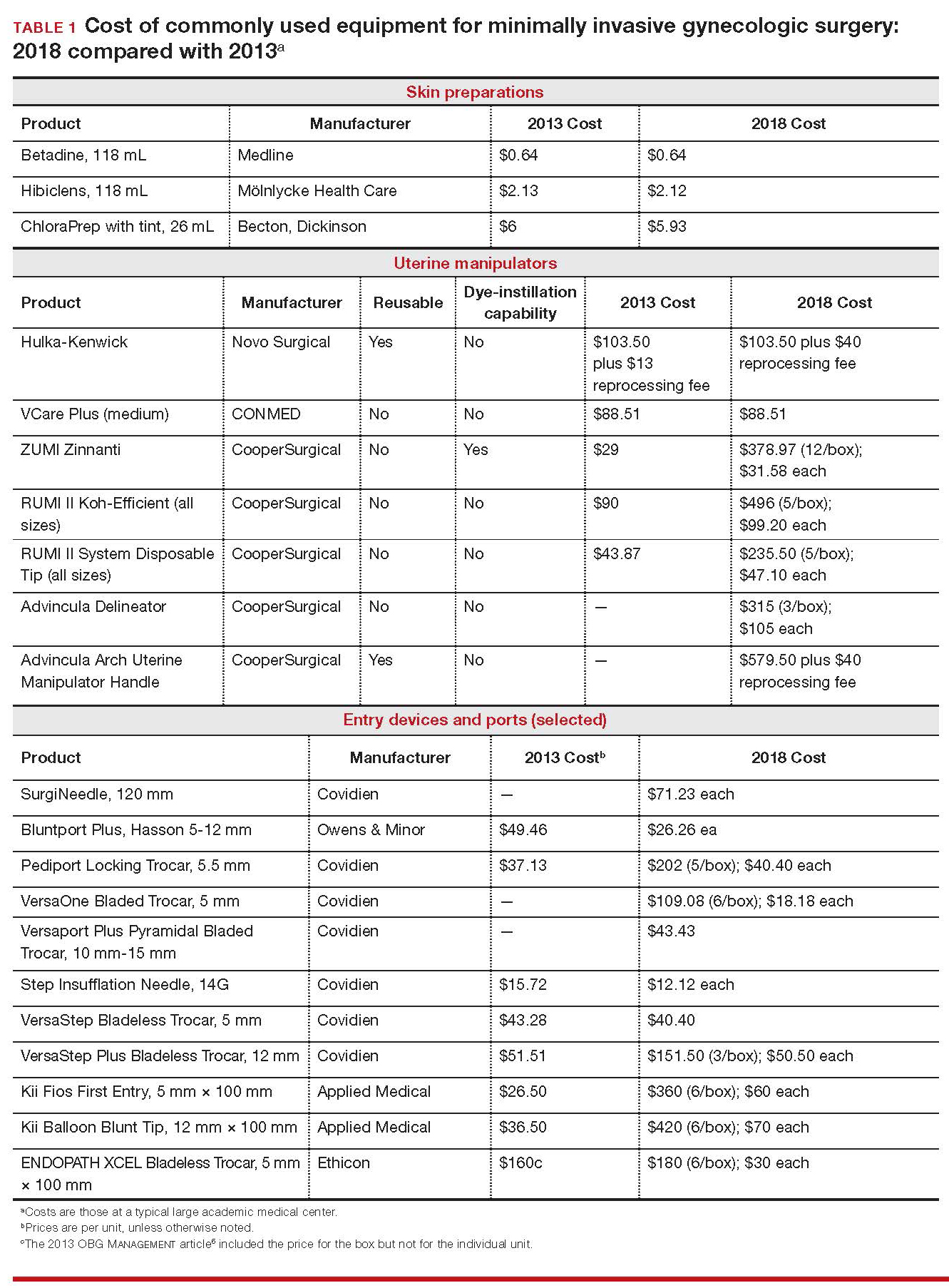

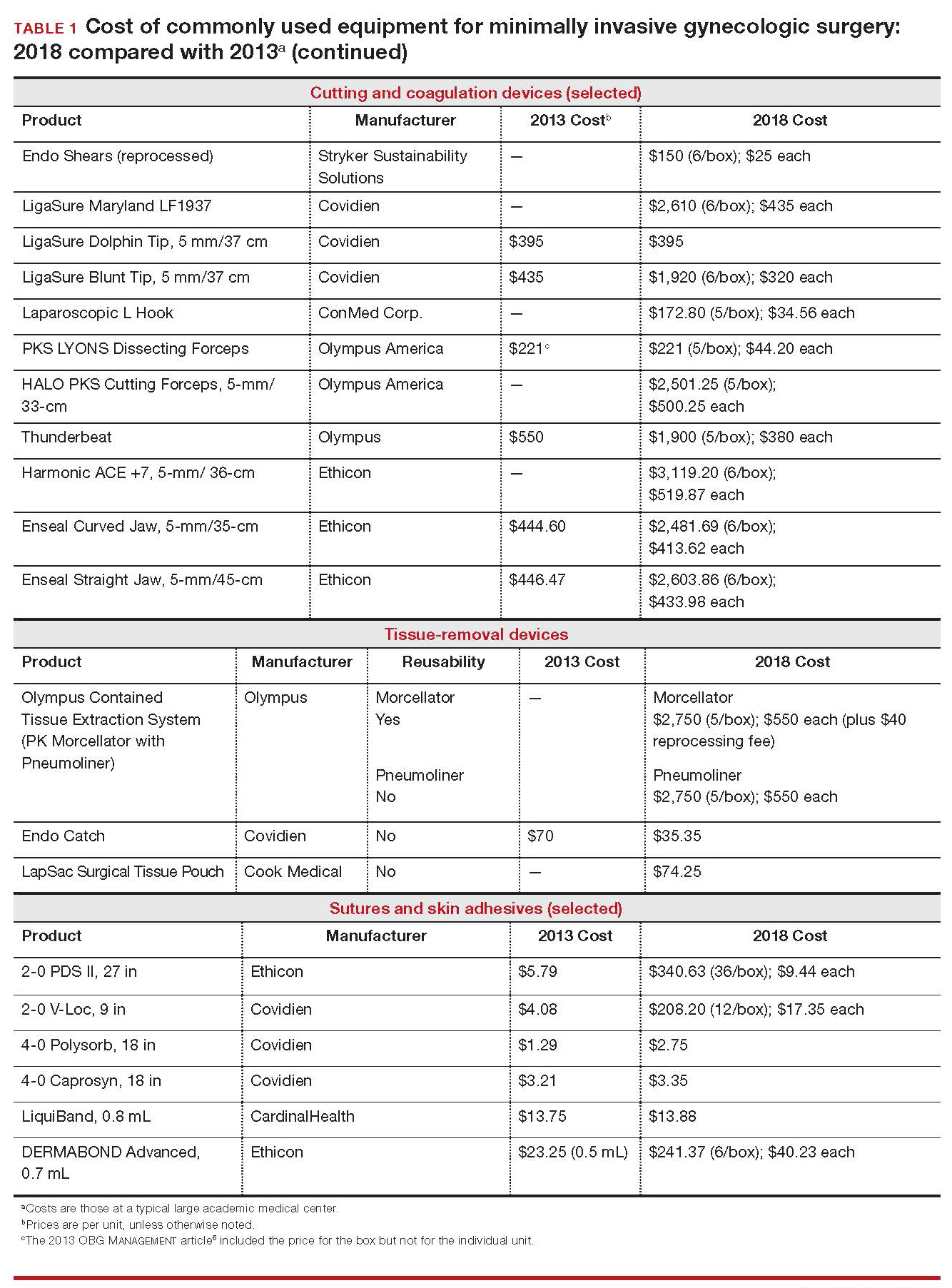

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

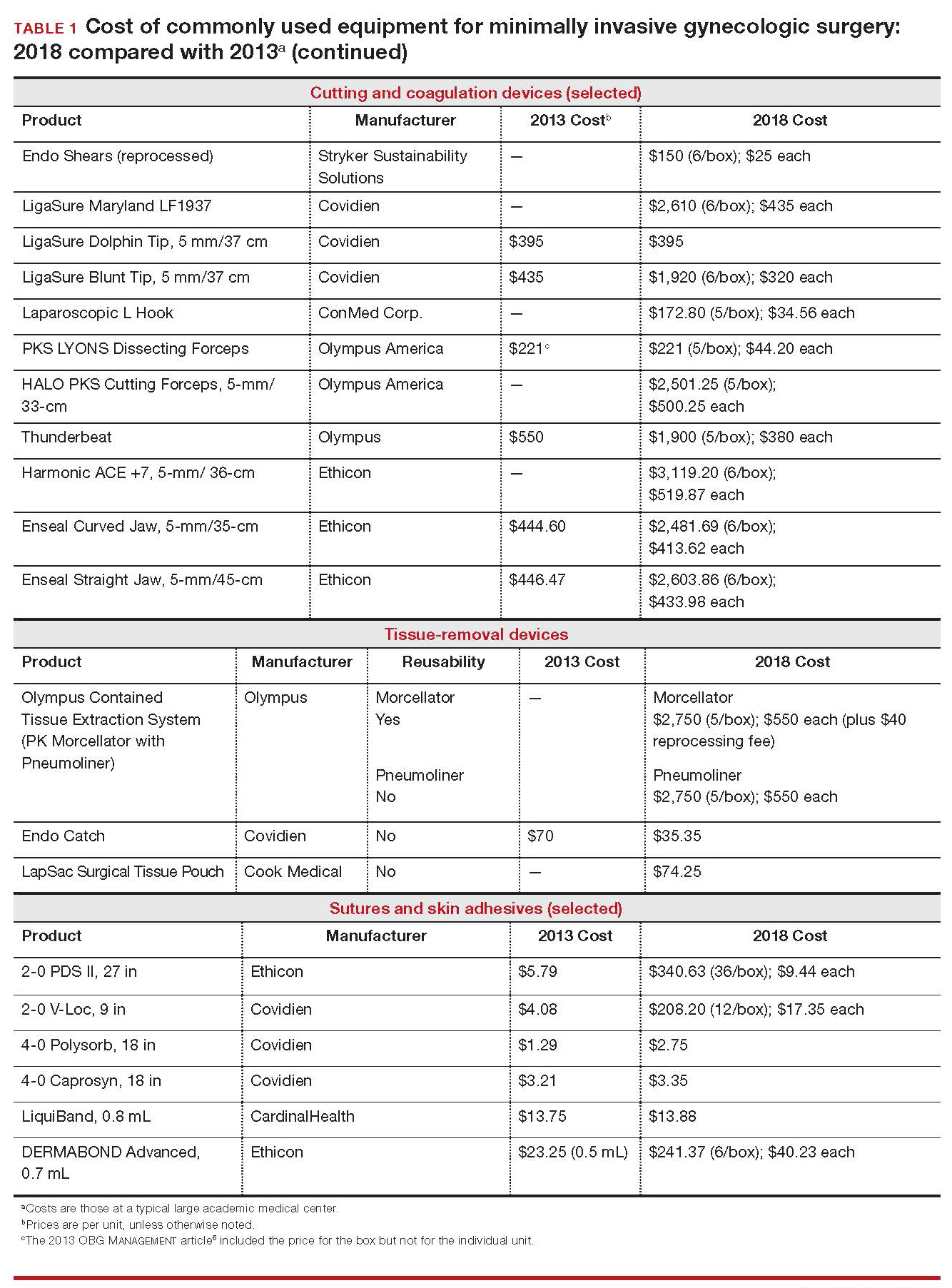

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep Bladeless Trocars are introduced after a Step Insufflation Needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 1).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (the LigaSure line of devices, Enseal). Ultrasonic devices, such as the Harmonic ACE, also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Suture material

Suture material

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Synthetic and delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently. The barbed suture also has gained popularity because it anchors to tissue without the need for intracorporeal or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 1).

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can contain or prevent spillage outside the bag.

A large uterus that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be manually morcellated. Appropriate candidates can undergo power morcellation using an FDA-approved device. (TABLE 1), allowing for the removal of smaller pieces through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy.

Issues surrounding morcellation continue to require that gynecologic surgeons understand FDA recommendations. In 2014, the FDA issued a safety communication that morcellation is “contraindicated in gynecologic surgery if tissue is known or suspected to be malignant; it is contraindicated for uterine tissue removal with presumed benign fibroids in perimenopausal women.”12 A black-box warning was issued that uterine tissue might contain unsuspected cancer.

A task force created by AAGL addressed key issues in this controversy.

AAGL then provided guidelines related to morcellation13:

- Do not use morcellate in the setting of known malignancy.

- Provide appropriate preoperative evaluation with up-to-date Pap smear screening and image analysis.

- Increasing age significantly increases the risk of leiomyosarcoma, especially in a postmenopausal woman.

- Fibroid growth is not a reliable sign of malignancy.

- Do not use a morcellator if the patient is at high risk for malignancy.

- If leiomyosarcoma is the presumed pathology, await the final pathology report before proceeding with hysterectomy.

- Concomitant use of a bag might mitigate the risk of tissue spread.

- Obtain informed consent before proceeding with morcellation.

Continue to: Skin closure

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures can be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (Polysorb).

Skin adhesive closes incisions quickly, avoids inflammation related to foreign bodies, and can ease patients’ concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 1).

The impact of physician experience

Physician experience has been shown to reduce cost while maintaining quality of care.14 That was the conclusion of researchers who undertook a retrospective study, addressing cost and clinical outcomes, of senior and junior attending physicians who performed laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy on 120 patients. Studies such as these often lead to clinical pathways to facilitate cost-effective quality care.

--

CASE Same outcome at lower cost

The hypothetical 43-year-old patient in the opening case undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. In this scenario, however, the surgeon makes the following product choices:

- The patient is prepped with Hibiclens.

- A VCare Plus uterine manipulator is placed.

- Laparoscopic ports include a VersaStep Plus Bladeless Trocar with Step Insufflation Needle; Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar; and 2 VersaOne Bladed trocars.

- The surgeon uses the PKS LYONS Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed Endo Shears to perform the hysterectomy.

- The uterus is enclosed in an Endo Catch bag and removed through the minilaparotomy site.

- The vaginal cuff is closed using 2-0 V-Loc barbed suture. Skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid absorbable suture.

The cost of this set of products? $360.44 or, roughly, $1,231.96 less than the set-up described in the case at the beginning of this article (TABLE 2).

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

Here are key points to take away from this analysis and discussion:

- As third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures from surgeon to surgeon, reimbursement might be stratified—thereby favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost containment.

- There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little or no impact on the quality of outcome.

- Surgeons who are familiar with surgical instruments and models available at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions. (See “Caregivers should keep cost in mind: Here’s why,” in the Web version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.)

- Cost is not the only indicator of value: The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

- Last, it makes sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays. However, we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meredith Snook, MD, who was coauthor of the original 2013 article6 and Kathleen Riordan, BSN, RN, for assistance in gathering specific cost-related information for this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure projections 2017-2026: Forecast summary. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems /Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299-303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundor P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomised trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139-1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

- Benezra V, Verma U, Whitted RW. Comparison of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical treatment of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(1): 20-21.

- Sanfilippo JS, Snook ML. Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. OBG Manag. 2013;25(11):40-41,44,46-48,72.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886-887.

- Ott J, Jaeger-Lansky A, Poschalko G, et al. Entry techniques in gynecologic laparoscopy—a review. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9(2):139-146.

- Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, et al. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763-766.

- Schäfer M, Lauper M, Krähenbühl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275- 280.

- Immediately in effect guidance document: product labeling for laparoscopic power morcellators. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health; November 25, 2014. www.fda.gov/downloads /MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance /GuidanceDocuments/UCM424123.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- Tissue Extraction Task Force Members. Morcellation during uterine tissue extraction: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(4):543-550.

- Chang WC, Li TC, Lin CC. The effect of physician experience on costs and clinical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a multivariate analysis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(3):356-359.

Robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis following sterilization

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

Myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid in a patient desiring future fertility

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

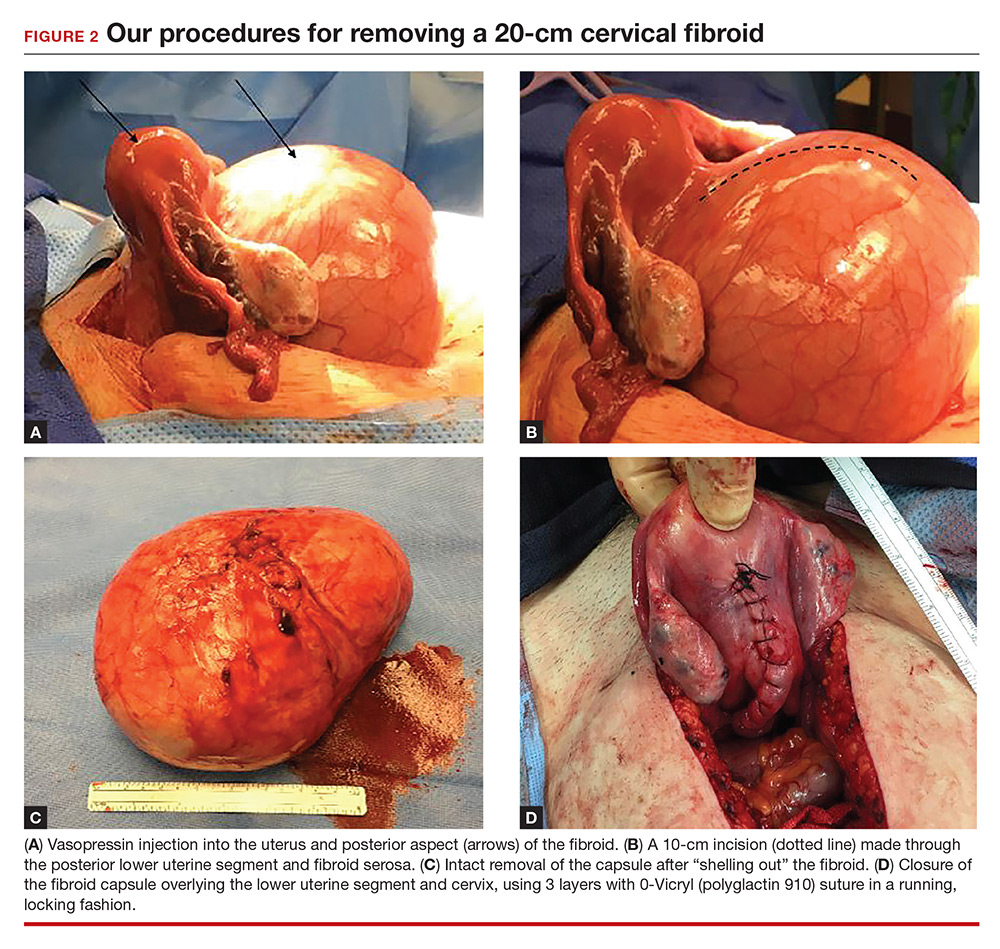

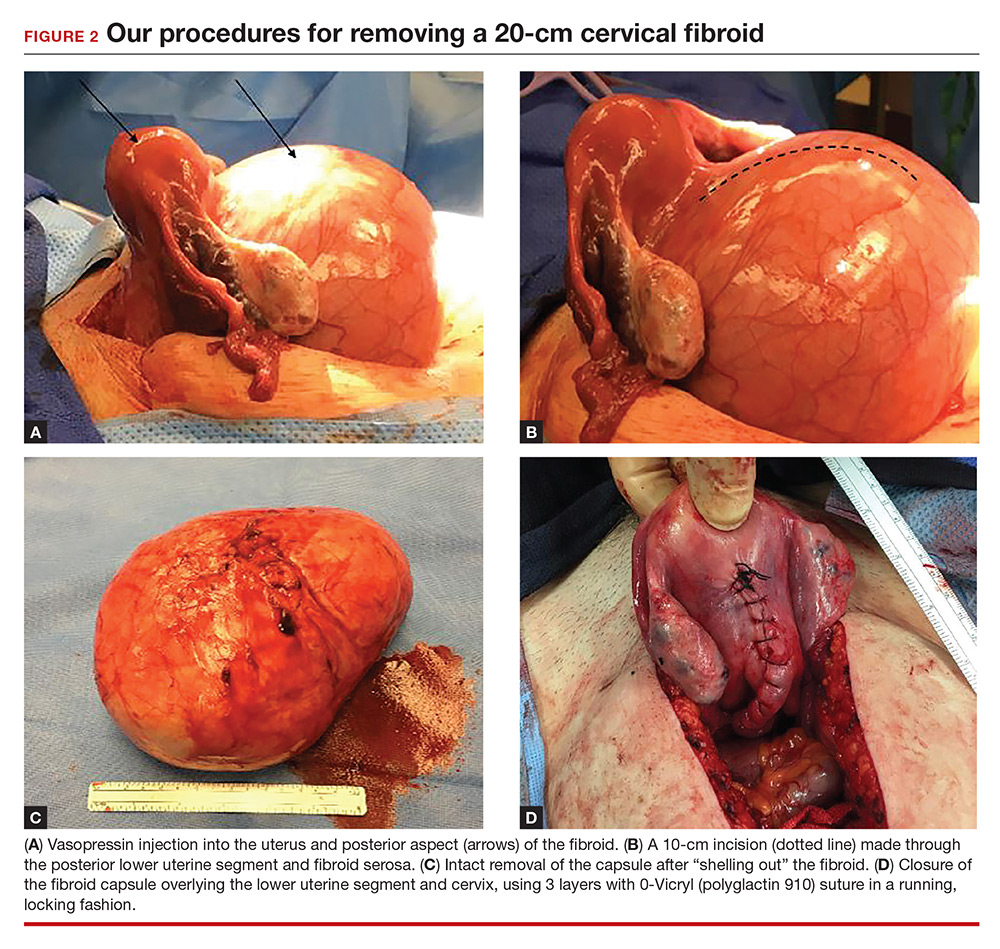

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

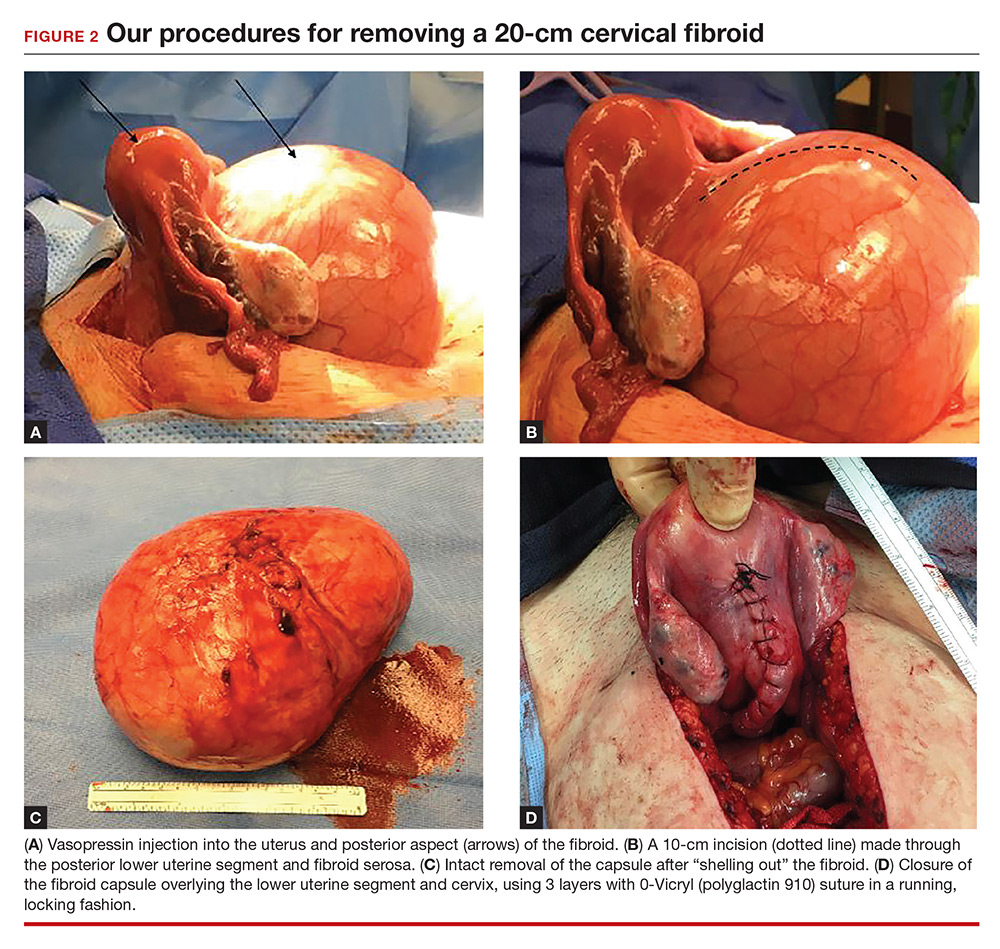

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.