User login

Defending access to reproductive health care

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

The 1973 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in Roe v Wade was a landmark ruling,1 establishing that the United States Constitution provides a fundamental “right to privacy,” protecting pregnant people’s freedom to access all available reproductive health care options. Recognizing that the right to abortion was not absolute, the majority of justices supported a trimester system. In the first trimester, decisions about abortion care are fully controlled by patients and clinicians, and no government could place restrictions on access to abortion. In the second trimester, SCOTUS ruled that states may choose to regulate abortion to protect maternal health. (As an example of such state restrictions, in Massachusetts, for many years, but no longer, the state required that abortions occur in a hospital when the patient was between 18 and 24 weeks’ gestation in order to facilitate comprehensive emergency care for complications.) Beginning in the third trimester, a point at which a fetus could be viable, the Court ruled that a government could prohibit abortion except when an abortion was necessary to protect the life or health of the pregnant person. In 1992, the SCOTUS decision in Planned Parenthood v Casey2 rejected the trimester system, reaffirming the right to an abortion before fetal viability, and adopting a new standard that states may not create an undue burden on a person seeking an abortion b

If, as anticipated, the 2022 SCOTUS decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization3 overturns the precedents set in Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v Casey, decisions on abortion law will be relegated to elected legislators and state courts.4 It is expected that at least 26 state legislatures and governors will enact stringent new restrictions on access to abortion. This cataclysmic reversal of judicial opinion creates a historic challenge to obstetrician-gynecologists and their patients and could threaten access to other vital reproductive services beyond abortion, like contraception. We will be fighting, state by state, for people’s right to access all available reproductive health procedures. This will also significantly affect the ability for providers in women’s reproductive health to obtain appropriate and necessary education and training in a critical skills. If access to safe abortion is restricted, we fear patients may be forced to consider unsafe abortion, raising the specter of a return to the 1960s, when an epidemic of unsafe abortion caused countless injuries and deaths.5,6

How do we best prepare for these challenges?

- We will need to be flexible and continually evolve our clinical practices to be adherent with state and local legislation and regulation.

- To reduce unintended pregnancies, we need to strengthen our efforts to ensure that every patient has ready access to all available contraceptive options with no out-of-pocket cost.

- When a contraceptive is desired, we will focus on educating people about effectiveness, and offering them highly reliable contraception, such as the implant or intrauterine devices.

- We need to ensure timely access to abortion if state-based laws permit abortion before 6 or 7 weeks’ gestation. Providing medication abortion without an in-person visit using a telehealth option would be one option to expand rapid access to early first trimester abortion.

- Clinicians in states with access to abortion services will need to collaborate with colleagues in states with restrictions on abortion services to improve patient access across state borders.

On a national level, advancing our effective advocacy in Congress may lead to national legislation passed and signed by the President. This could supersede most state laws prohibiting access to comprehensive women’s reproductive health and create a unified, national approach to abortion care, allowing for the appropriate training of all obstetrician-gynecologists. We will also need to develop teams in every state capable of advocating for laws that ensure access to all reproductive health care options. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has leaders trained and tasked with legislative advocacy in every state.7 This network will be a foundation upon which to build additional advocacy efforts.

As women’s health care professionals, our responsibility to our patients, is to work to ensure universal access to safe and effective comprehensive reproductive options, and to ensure that our workforce is prepared to meet the needs of our patients by defending the patient-clinician relationship. Abortion care saves lives of pregnant patients and reduces maternal morbidity.8 Access to safe abortion care as part of comprehensive reproductive services is an important component of health care. ●

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

- Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- Planned Parenthood v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 19-1392. https://www.supremecourt.gov/search .aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html /public/19-1392.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Gerstein J, Ward A. Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows. Politico. May 5, 2022. Updated May 3, 2022.

- Gold RB. Lessons from before Roe: will past be prologue? Guttmacher Institute. March 1, 2003. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03 /lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Edelin KC. Broken Justice: A True Story of Race, Sex and Revenge in a Boston Courtroom. Pond View Press; 2007.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Get involved in your state. ACOG web site. https://www.acog.org/advocacy /get-involved/get-involved-in-your-state. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving Birth Outcomes. Bale JR, Stoll BJ, Lucas AO, eds. Reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Improving Birth Outcomes: Meeting the Challenge in the Developing World. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003.

Myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid in a patient desiring future fertility

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

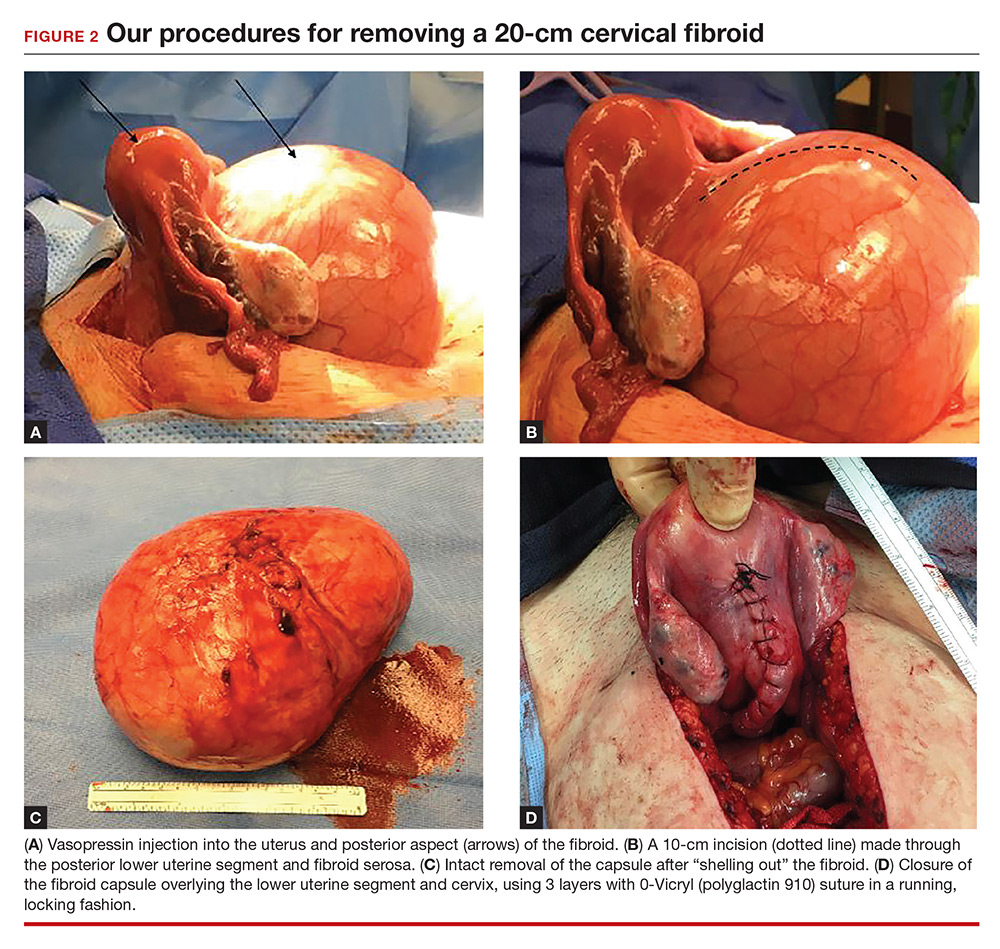

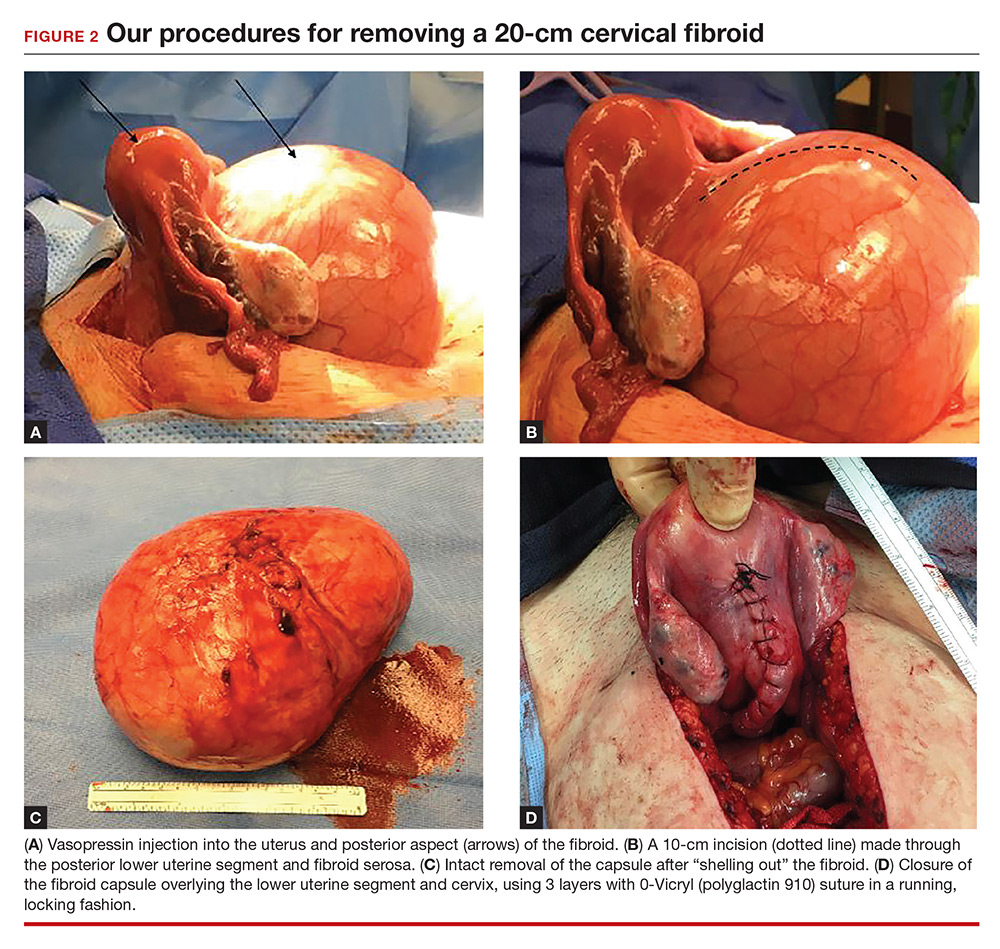

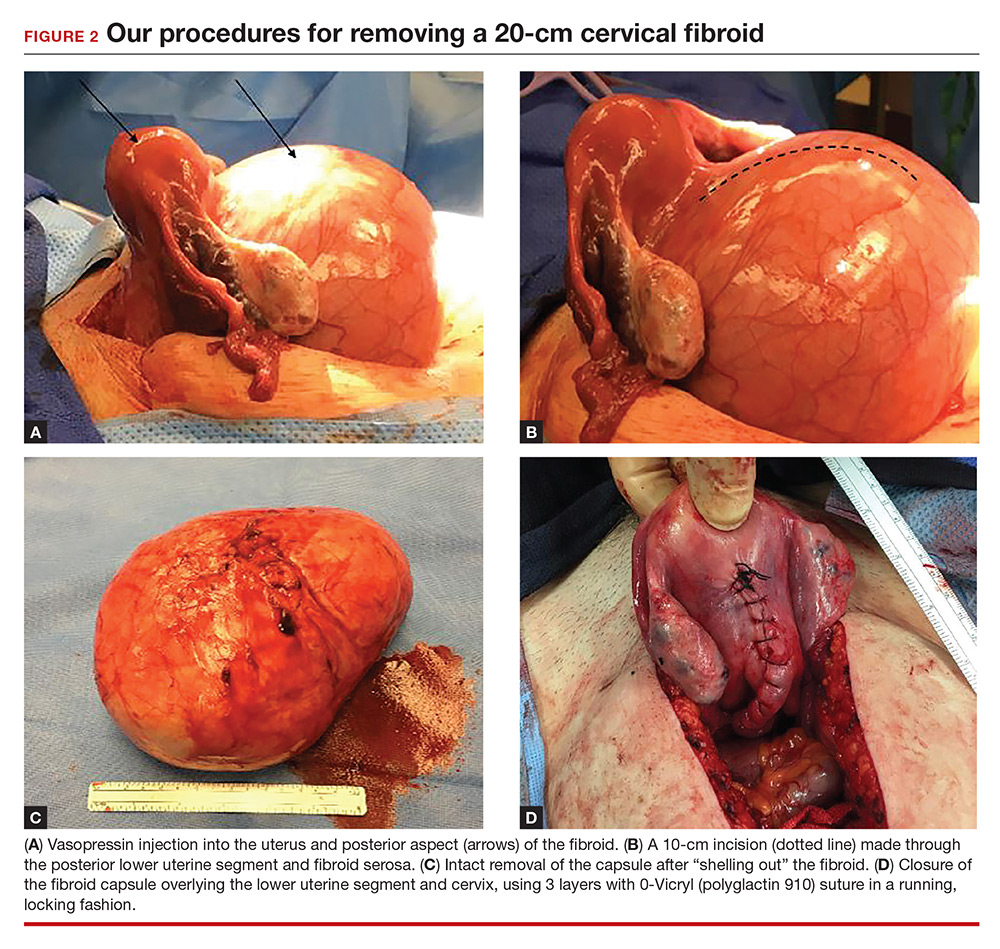

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Reinventing the role of the gynecologist

The time is now to change office gynecologic care.

Scientific advances in cervical surveillance enable women to be screened later in life, less frequently, and more efficiently than ever before. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that screening start at age 21, then continue at 3-year intervals until age 30, if the results are normal. At age 30, cotesting for human papillomavirus enables the screening interval to be extended to 5 years, if the results are normal. Screening endpoints may be reached upon removal of the cervix (if there is no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] II or greater) or by age 65 (if there is adequate negative screening and no history of CIN II or greater in the past 20 years).

In November 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released the statement that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of the clinical breast exam beyond those of the screening mammogram.

The ACOG Committee Opinion #534, entitled "The Well-Women Visit," was published in August 2012. This document states: "An annual pelvic examination seems logical, but also lacks data to support a specific time frame of frequency of such examinations. The decision whether or not to perform a complete pelvic examination at the time of the periodic health examination for the asymptomatic patient should be a shared decision after a discussion between the patient and her health care provider."

The recent recommendation for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans state that with a normal result, the testing interval may be extended to 15 years.

The traditional "annual exam" must change or office gynecology may run the risk of becoming obsolete.

Epidemiologic data from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention show that the most common cause of death in women is cardiovascular disease (23.5%), followed by cancer (22.6%). Obesity continues to plague the United States, and is more common in women than in men, and most common in African American women.

In the past, gynecologists have significantly impacted public health through our vigilant use of the Pap smear. Today, we have the opportunity to lead the charge in cardiovascular disease prevention, genetics screenings for cancer risk, lifestyle intervention to begin the fight against obesity, and fulfillment of the mandate to educate reproductive age women about the benefits of long-acting reversible contraception.

Certainly ob.gyns. are adept in the art of obtaining a family history. With the ever-changing opportunities in the expanding world of genetic testing, it is incumbent upon ob.gyns. to guide our at-risk patients to a genetic counselor. Positive outcomes will lead to more vigilant testing, and at best cancer prevention, or at the least, a diagnosis prior to advanced stages. Negative results will limit unnecessary testing and relieve patient anxiety.

We must find novel and effective tools to help our patients begin to wage war on obesity. We may start by listing the body mass index for every patient in every chart, and discussing weight as a health concern, which is no different from how we address hypertension.

Recent data reveal that prematurity, preeclampsia, placental abruption, and gestational diabetes are harbingers of cardiovascular risk. In addition, the Dallas Heart Study found that "women who have two to three live births have a lower rate of subclinical atherosclerosis when compared to women that have either never delivered a live baby or those that have delivered four or more children." These obstetrically derived data place the ob.gyn. in a unique position to identify possible cardiovascular risk potentially years before there is clinical disease. Our patients also should be queried about familial cardiac risk factors such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and early cardiac death (defined as cardiac death in a first-degree male relative younger than 55 years of age or in a first-degree female relative younger than 65 years of age).

We propose that ob.gyns. adopt a hybrid ob.gyn. approach to the algorithm accepted by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Global Cardiovascular Risk Calculator (which can be found in the Apple app store). The calculation is based on race, age, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and current use of blood pressure medication. If your patient is 40 years of age or older and her global score is 7.5% or greater for a cardiovascular event in 10 years, your patient should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification. If the score is less than 7.5% with a family history of cardiovascular disease in the same patient, additional testing should be considered to further risk stratify the patient.

In addition, if the risk assessment shows the score is less than 7.5% and your patient has a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, she should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Although the 10-year risk assessment cannot be calculated for women less than 40 years of age, a lifetime cardiovascular risk can be calculated using the app. Thus for women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk of greater than 45%, we recommend aggressive risk factor modification. For women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk that does not exceed 45%, with a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, aggressive risk factor modification should be considered in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Once we assess risk and fully understand the metabolism of our patients, we can educate them about the pathophysiology of vascular disease and its prevention, with a focus on stress management, nutritional prudence, and appropriate exercise.

It is critical that patients understand that they are at risk for a future cardiovascular event and that their risk is real and quantifiable. This represents a paradigm shift not only in gynecologic care but also cardiac care. Too often patients adjust their behavior with their first cardiac event, be that angina or a myocardial infarction. We now have the opportunity to provide our patients the opportunity to modify their lives in their reproductive years, and thus significantly reduce their chance of ever experiencing a cardiac event.

As providers of women’s health, we must evolve to meet the needs of our patients. We have the opportunity to provide early intervention to reduce the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among our patients.

Dr. Jaspan is chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Shipon is cofounder of the Heart Center of Philadelphia at Jefferson and director of cardiovascular rehabilitation at Jefferson University Hospitals and Methodist Hospital in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Shipon said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

The time is now to change office gynecologic care.

Scientific advances in cervical surveillance enable women to be screened later in life, less frequently, and more efficiently than ever before. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that screening start at age 21, then continue at 3-year intervals until age 30, if the results are normal. At age 30, cotesting for human papillomavirus enables the screening interval to be extended to 5 years, if the results are normal. Screening endpoints may be reached upon removal of the cervix (if there is no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] II or greater) or by age 65 (if there is adequate negative screening and no history of CIN II or greater in the past 20 years).

In November 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released the statement that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of the clinical breast exam beyond those of the screening mammogram.

The ACOG Committee Opinion #534, entitled "The Well-Women Visit," was published in August 2012. This document states: "An annual pelvic examination seems logical, but also lacks data to support a specific time frame of frequency of such examinations. The decision whether or not to perform a complete pelvic examination at the time of the periodic health examination for the asymptomatic patient should be a shared decision after a discussion between the patient and her health care provider."

The recent recommendation for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans state that with a normal result, the testing interval may be extended to 15 years.

The traditional "annual exam" must change or office gynecology may run the risk of becoming obsolete.

Epidemiologic data from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention show that the most common cause of death in women is cardiovascular disease (23.5%), followed by cancer (22.6%). Obesity continues to plague the United States, and is more common in women than in men, and most common in African American women.

In the past, gynecologists have significantly impacted public health through our vigilant use of the Pap smear. Today, we have the opportunity to lead the charge in cardiovascular disease prevention, genetics screenings for cancer risk, lifestyle intervention to begin the fight against obesity, and fulfillment of the mandate to educate reproductive age women about the benefits of long-acting reversible contraception.

Certainly ob.gyns. are adept in the art of obtaining a family history. With the ever-changing opportunities in the expanding world of genetic testing, it is incumbent upon ob.gyns. to guide our at-risk patients to a genetic counselor. Positive outcomes will lead to more vigilant testing, and at best cancer prevention, or at the least, a diagnosis prior to advanced stages. Negative results will limit unnecessary testing and relieve patient anxiety.

We must find novel and effective tools to help our patients begin to wage war on obesity. We may start by listing the body mass index for every patient in every chart, and discussing weight as a health concern, which is no different from how we address hypertension.

Recent data reveal that prematurity, preeclampsia, placental abruption, and gestational diabetes are harbingers of cardiovascular risk. In addition, the Dallas Heart Study found that "women who have two to three live births have a lower rate of subclinical atherosclerosis when compared to women that have either never delivered a live baby or those that have delivered four or more children." These obstetrically derived data place the ob.gyn. in a unique position to identify possible cardiovascular risk potentially years before there is clinical disease. Our patients also should be queried about familial cardiac risk factors such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and early cardiac death (defined as cardiac death in a first-degree male relative younger than 55 years of age or in a first-degree female relative younger than 65 years of age).

We propose that ob.gyns. adopt a hybrid ob.gyn. approach to the algorithm accepted by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Global Cardiovascular Risk Calculator (which can be found in the Apple app store). The calculation is based on race, age, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and current use of blood pressure medication. If your patient is 40 years of age or older and her global score is 7.5% or greater for a cardiovascular event in 10 years, your patient should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification. If the score is less than 7.5% with a family history of cardiovascular disease in the same patient, additional testing should be considered to further risk stratify the patient.

In addition, if the risk assessment shows the score is less than 7.5% and your patient has a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, she should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Although the 10-year risk assessment cannot be calculated for women less than 40 years of age, a lifetime cardiovascular risk can be calculated using the app. Thus for women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk of greater than 45%, we recommend aggressive risk factor modification. For women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk that does not exceed 45%, with a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, aggressive risk factor modification should be considered in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Once we assess risk and fully understand the metabolism of our patients, we can educate them about the pathophysiology of vascular disease and its prevention, with a focus on stress management, nutritional prudence, and appropriate exercise.

It is critical that patients understand that they are at risk for a future cardiovascular event and that their risk is real and quantifiable. This represents a paradigm shift not only in gynecologic care but also cardiac care. Too often patients adjust their behavior with their first cardiac event, be that angina or a myocardial infarction. We now have the opportunity to provide our patients the opportunity to modify their lives in their reproductive years, and thus significantly reduce their chance of ever experiencing a cardiac event.

As providers of women’s health, we must evolve to meet the needs of our patients. We have the opportunity to provide early intervention to reduce the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among our patients.

Dr. Jaspan is chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Shipon is cofounder of the Heart Center of Philadelphia at Jefferson and director of cardiovascular rehabilitation at Jefferson University Hospitals and Methodist Hospital in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Shipon said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

The time is now to change office gynecologic care.

Scientific advances in cervical surveillance enable women to be screened later in life, less frequently, and more efficiently than ever before. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that screening start at age 21, then continue at 3-year intervals until age 30, if the results are normal. At age 30, cotesting for human papillomavirus enables the screening interval to be extended to 5 years, if the results are normal. Screening endpoints may be reached upon removal of the cervix (if there is no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] II or greater) or by age 65 (if there is adequate negative screening and no history of CIN II or greater in the past 20 years).

In November 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released the statement that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of the clinical breast exam beyond those of the screening mammogram.

The ACOG Committee Opinion #534, entitled "The Well-Women Visit," was published in August 2012. This document states: "An annual pelvic examination seems logical, but also lacks data to support a specific time frame of frequency of such examinations. The decision whether or not to perform a complete pelvic examination at the time of the periodic health examination for the asymptomatic patient should be a shared decision after a discussion between the patient and her health care provider."

The recent recommendation for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans state that with a normal result, the testing interval may be extended to 15 years.

The traditional "annual exam" must change or office gynecology may run the risk of becoming obsolete.

Epidemiologic data from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention show that the most common cause of death in women is cardiovascular disease (23.5%), followed by cancer (22.6%). Obesity continues to plague the United States, and is more common in women than in men, and most common in African American women.

In the past, gynecologists have significantly impacted public health through our vigilant use of the Pap smear. Today, we have the opportunity to lead the charge in cardiovascular disease prevention, genetics screenings for cancer risk, lifestyle intervention to begin the fight against obesity, and fulfillment of the mandate to educate reproductive age women about the benefits of long-acting reversible contraception.

Certainly ob.gyns. are adept in the art of obtaining a family history. With the ever-changing opportunities in the expanding world of genetic testing, it is incumbent upon ob.gyns. to guide our at-risk patients to a genetic counselor. Positive outcomes will lead to more vigilant testing, and at best cancer prevention, or at the least, a diagnosis prior to advanced stages. Negative results will limit unnecessary testing and relieve patient anxiety.

We must find novel and effective tools to help our patients begin to wage war on obesity. We may start by listing the body mass index for every patient in every chart, and discussing weight as a health concern, which is no different from how we address hypertension.

Recent data reveal that prematurity, preeclampsia, placental abruption, and gestational diabetes are harbingers of cardiovascular risk. In addition, the Dallas Heart Study found that "women who have two to three live births have a lower rate of subclinical atherosclerosis when compared to women that have either never delivered a live baby or those that have delivered four or more children." These obstetrically derived data place the ob.gyn. in a unique position to identify possible cardiovascular risk potentially years before there is clinical disease. Our patients also should be queried about familial cardiac risk factors such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and early cardiac death (defined as cardiac death in a first-degree male relative younger than 55 years of age or in a first-degree female relative younger than 65 years of age).

We propose that ob.gyns. adopt a hybrid ob.gyn. approach to the algorithm accepted by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Global Cardiovascular Risk Calculator (which can be found in the Apple app store). The calculation is based on race, age, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and current use of blood pressure medication. If your patient is 40 years of age or older and her global score is 7.5% or greater for a cardiovascular event in 10 years, your patient should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification. If the score is less than 7.5% with a family history of cardiovascular disease in the same patient, additional testing should be considered to further risk stratify the patient.

In addition, if the risk assessment shows the score is less than 7.5% and your patient has a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, she should be considered for aggressive risk factor modification in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Although the 10-year risk assessment cannot be calculated for women less than 40 years of age, a lifetime cardiovascular risk can be calculated using the app. Thus for women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk of greater than 45%, we recommend aggressive risk factor modification. For women less than 40 years of age with a lifetime cardiovascular risk that does not exceed 45%, with a personal history of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, placental abruption, gestational diabetes mellitus, polycystic ovarian syndrome, or metabolic syndrome, or a family history of early cardiac death, aggressive risk factor modification should be considered in conjunction with management by a medical provider with expertise in cardiovascular disease prevention.

Once we assess risk and fully understand the metabolism of our patients, we can educate them about the pathophysiology of vascular disease and its prevention, with a focus on stress management, nutritional prudence, and appropriate exercise.

It is critical that patients understand that they are at risk for a future cardiovascular event and that their risk is real and quantifiable. This represents a paradigm shift not only in gynecologic care but also cardiac care. Too often patients adjust their behavior with their first cardiac event, be that angina or a myocardial infarction. We now have the opportunity to provide our patients the opportunity to modify their lives in their reproductive years, and thus significantly reduce their chance of ever experiencing a cardiac event.

As providers of women’s health, we must evolve to meet the needs of our patients. We have the opportunity to provide early intervention to reduce the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among our patients.

Dr. Jaspan is chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Shipon is cofounder of the Heart Center of Philadelphia at Jefferson and director of cardiovascular rehabilitation at Jefferson University Hospitals and Methodist Hospital in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan and Dr. Shipon said they had no relevant financial disclosures.