User login

Take care to care for the poor

I’m guilty. I feel a sense of entitlement, as many of us do. I have always had access to the best health care available. Even as a child, whenever I had a runny nose, my parents not only knew what to do but could afford whatever it took to make me feel better. And vaccine-preventable illnesses? They didn’t stand a chance at my house. I remember the day when I was a little girl and my father, a general practitioner, figured out my plan to wait him out as he stood patiently outside the bathroom door, vaccine in hand. He eventually got tired of waiting, barged in, oblivious to the fact that I was sitting on the potty (twiddling my fingers), and shot me right in arm. The nerve!

Many of us have no concept of what it is like to be ill. I mean really ill with no one to help, and no way to pay for that help even if we could find it. In the March 6, 2014, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of "Global Supply of Health Professionals" note that there’s a worldwide crisis of severe shortages, as well as maldistribution of health care professionals intensified by three global transitions: redistribution of the disability burden, demographic changes, and epidemiologic shifts. An estimated 25% of physicians in America come from other countries. Naturally, in some cases the countries of origin have their own health care challenges, so the trend to immigrate to America has significant potential to exacerbate an already critical shortage.

Of the estimated 9.2 million doctors worldwide, 8% reside in the United States. Of the 18.1 million nurses, 17% are in here. To put it in perspective, only 4% of the world’s population lives in the United States, yet we command a lion’s share of the global health care workforce, leaving the citizens of many other countries vulnerable to excessive suffering, premature death, and preventable diseases.

With all that America has to offer, I don’t see the pendulum shifting back in the other direction any time soon, but many of us are in a position to provide much needed health care to our brothers and sisters in even the most remote areas of the world.

As squeamish as I am about charting unknown territory, even I went on a medical missions trip to Nicaragua a few years ago and I will never forget it. We had to climb up the side of a mountain to get to a clearing that would hold the makeshift medical clinic. Of course, the locals came out in large numbers to receive much-needed medical care.

On the way back to the hotel I noticed some little boys tossing an object back and forth in the street. It seemed like pleasant fun until we got closer and I saw the object they were tossing was a dead rat. Even what we consider an inexpensive child’s toy is a luxury for many. If you consider salary and benefits, we hospitalists make more, on average, in a single shift than many Nicaraguans make in an entire year.

Every physician should spend some time caring for the poorest of the poor, whether it be in a needy foreign country, Appalachia or rural America, or in the inner city, often just 30 minutes from our homes.

Surely it will help or change the patient’s life. But, too, it just might change your perspective, forever, and renew your passion for what we do – help others.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I’m guilty. I feel a sense of entitlement, as many of us do. I have always had access to the best health care available. Even as a child, whenever I had a runny nose, my parents not only knew what to do but could afford whatever it took to make me feel better. And vaccine-preventable illnesses? They didn’t stand a chance at my house. I remember the day when I was a little girl and my father, a general practitioner, figured out my plan to wait him out as he stood patiently outside the bathroom door, vaccine in hand. He eventually got tired of waiting, barged in, oblivious to the fact that I was sitting on the potty (twiddling my fingers), and shot me right in arm. The nerve!

Many of us have no concept of what it is like to be ill. I mean really ill with no one to help, and no way to pay for that help even if we could find it. In the March 6, 2014, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of "Global Supply of Health Professionals" note that there’s a worldwide crisis of severe shortages, as well as maldistribution of health care professionals intensified by three global transitions: redistribution of the disability burden, demographic changes, and epidemiologic shifts. An estimated 25% of physicians in America come from other countries. Naturally, in some cases the countries of origin have their own health care challenges, so the trend to immigrate to America has significant potential to exacerbate an already critical shortage.

Of the estimated 9.2 million doctors worldwide, 8% reside in the United States. Of the 18.1 million nurses, 17% are in here. To put it in perspective, only 4% of the world’s population lives in the United States, yet we command a lion’s share of the global health care workforce, leaving the citizens of many other countries vulnerable to excessive suffering, premature death, and preventable diseases.

With all that America has to offer, I don’t see the pendulum shifting back in the other direction any time soon, but many of us are in a position to provide much needed health care to our brothers and sisters in even the most remote areas of the world.

As squeamish as I am about charting unknown territory, even I went on a medical missions trip to Nicaragua a few years ago and I will never forget it. We had to climb up the side of a mountain to get to a clearing that would hold the makeshift medical clinic. Of course, the locals came out in large numbers to receive much-needed medical care.

On the way back to the hotel I noticed some little boys tossing an object back and forth in the street. It seemed like pleasant fun until we got closer and I saw the object they were tossing was a dead rat. Even what we consider an inexpensive child’s toy is a luxury for many. If you consider salary and benefits, we hospitalists make more, on average, in a single shift than many Nicaraguans make in an entire year.

Every physician should spend some time caring for the poorest of the poor, whether it be in a needy foreign country, Appalachia or rural America, or in the inner city, often just 30 minutes from our homes.

Surely it will help or change the patient’s life. But, too, it just might change your perspective, forever, and renew your passion for what we do – help others.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I’m guilty. I feel a sense of entitlement, as many of us do. I have always had access to the best health care available. Even as a child, whenever I had a runny nose, my parents not only knew what to do but could afford whatever it took to make me feel better. And vaccine-preventable illnesses? They didn’t stand a chance at my house. I remember the day when I was a little girl and my father, a general practitioner, figured out my plan to wait him out as he stood patiently outside the bathroom door, vaccine in hand. He eventually got tired of waiting, barged in, oblivious to the fact that I was sitting on the potty (twiddling my fingers), and shot me right in arm. The nerve!

Many of us have no concept of what it is like to be ill. I mean really ill with no one to help, and no way to pay for that help even if we could find it. In the March 6, 2014, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, authors of "Global Supply of Health Professionals" note that there’s a worldwide crisis of severe shortages, as well as maldistribution of health care professionals intensified by three global transitions: redistribution of the disability burden, demographic changes, and epidemiologic shifts. An estimated 25% of physicians in America come from other countries. Naturally, in some cases the countries of origin have their own health care challenges, so the trend to immigrate to America has significant potential to exacerbate an already critical shortage.

Of the estimated 9.2 million doctors worldwide, 8% reside in the United States. Of the 18.1 million nurses, 17% are in here. To put it in perspective, only 4% of the world’s population lives in the United States, yet we command a lion’s share of the global health care workforce, leaving the citizens of many other countries vulnerable to excessive suffering, premature death, and preventable diseases.

With all that America has to offer, I don’t see the pendulum shifting back in the other direction any time soon, but many of us are in a position to provide much needed health care to our brothers and sisters in even the most remote areas of the world.

As squeamish as I am about charting unknown territory, even I went on a medical missions trip to Nicaragua a few years ago and I will never forget it. We had to climb up the side of a mountain to get to a clearing that would hold the makeshift medical clinic. Of course, the locals came out in large numbers to receive much-needed medical care.

On the way back to the hotel I noticed some little boys tossing an object back and forth in the street. It seemed like pleasant fun until we got closer and I saw the object they were tossing was a dead rat. Even what we consider an inexpensive child’s toy is a luxury for many. If you consider salary and benefits, we hospitalists make more, on average, in a single shift than many Nicaraguans make in an entire year.

Every physician should spend some time caring for the poorest of the poor, whether it be in a needy foreign country, Appalachia or rural America, or in the inner city, often just 30 minutes from our homes.

Surely it will help or change the patient’s life. But, too, it just might change your perspective, forever, and renew your passion for what we do – help others.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

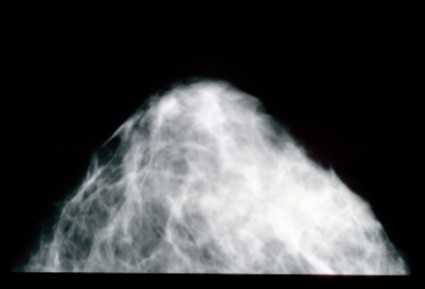

Mammogram data are not to die for

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Adopting a child, aligning with reality

When I was a little girl, I enjoyed watching the Brady Bunch on television. For those of you under the age of 30, who may not be familiar with this hit series, Mrs. Brady, played by Florence Henderson, was a stay-at-home mother with six kids, three of her own and three of her husband’s by a prior marriage. Somehow, the house was always immaculate, the kids were always well kept, and she always managed to be level-headed, warm, and nurturing (but Alice, the housekeeper, helped a lot).

Fast forward a few decades. Now women frequently are the primary breadwinners, often working outside the home and then even more when they return after work, tethered to a computer or with smartphone in hand. This is the new work-life balance equation for many of us.

My husband and I are currently seeking to adopt a little girl in the foster care system. If we are successful in 2014, this will be our second adoption in 5 years. Anyone who has ever added to their family this way can attest to the hurdles, stumbling blocks, and utter frustration the journey can hold. In the last 8 months, I have seen thousands of photos of waiting children and found only one child in our self-defined age group (4 or younger) who does not have major developmental or physical challenges. There are over 15 other families who have also inquired about her.

I used to feel guilty that I flipped through the pictures of special-needs children quickly, but when I think about my reality as a full-time hospitalist and a mother, I know I cannot provide a special-needs child with the attention she needs. If I have a patient in the ER with unstable angina and a child at home in the midst of a seizure, I cannot exactly call into work for "family reasons." How idyllic would it be for a physician to adopt a sick child, bringing her into a home already endowed with medical expertise? On its face, and to outsiders, it would be perfect. But I have to be realistic about what I can and cannot handle, and about what choice is caring and considerate to both patients and my existing family.

While I await that life-changing call from a social worker somewhere, who has seen my family profile and thinks we would be a perfect fit for a child in her caseload, I am working toward the future. I have a glimpse of what it will be like with two small children and a demanding job, and it has the potential to be chaotic, hair-raising, and overwhelming, but it can also be calm, joyous, and well organized. I realized it is okay to say, "I can’t do this by myself." Cooking, shopping, washing, homework, tantrums, beepers, ... oh my!

I have no relatives who can help make life more manageable, but I have figured out a few things I can do. In addition to a housekeeper, I decided to enlist the help of a personal assistant – who happens to also be my hairdresser and friend – whom I can pay by the hour ($25) to do a variety of tasks around the house and run errands here and there. A few hours here and there will make a huge difference in my peace of mind. I cannot yet rule out an au pair or live-in nanny, but we are not quite ready to share our space with anyone outside our family. I am thankful, of course, that this is even an option for my household financially.

Whether you are a soon-to-be mom or dad, you too may want to think out of the box about ways to trade a hectic, disorganized life for one far more peaceful and serene, even if it comes with a price tag. What works for me may not work for you, but there is a potential solution for us all. We may just have to search hard and pay for it.

Thoughts? E-mail me at [email protected].

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

When I was a little girl, I enjoyed watching the Brady Bunch on television. For those of you under the age of 30, who may not be familiar with this hit series, Mrs. Brady, played by Florence Henderson, was a stay-at-home mother with six kids, three of her own and three of her husband’s by a prior marriage. Somehow, the house was always immaculate, the kids were always well kept, and she always managed to be level-headed, warm, and nurturing (but Alice, the housekeeper, helped a lot).

Fast forward a few decades. Now women frequently are the primary breadwinners, often working outside the home and then even more when they return after work, tethered to a computer or with smartphone in hand. This is the new work-life balance equation for many of us.

My husband and I are currently seeking to adopt a little girl in the foster care system. If we are successful in 2014, this will be our second adoption in 5 years. Anyone who has ever added to their family this way can attest to the hurdles, stumbling blocks, and utter frustration the journey can hold. In the last 8 months, I have seen thousands of photos of waiting children and found only one child in our self-defined age group (4 or younger) who does not have major developmental or physical challenges. There are over 15 other families who have also inquired about her.

I used to feel guilty that I flipped through the pictures of special-needs children quickly, but when I think about my reality as a full-time hospitalist and a mother, I know I cannot provide a special-needs child with the attention she needs. If I have a patient in the ER with unstable angina and a child at home in the midst of a seizure, I cannot exactly call into work for "family reasons." How idyllic would it be for a physician to adopt a sick child, bringing her into a home already endowed with medical expertise? On its face, and to outsiders, it would be perfect. But I have to be realistic about what I can and cannot handle, and about what choice is caring and considerate to both patients and my existing family.

While I await that life-changing call from a social worker somewhere, who has seen my family profile and thinks we would be a perfect fit for a child in her caseload, I am working toward the future. I have a glimpse of what it will be like with two small children and a demanding job, and it has the potential to be chaotic, hair-raising, and overwhelming, but it can also be calm, joyous, and well organized. I realized it is okay to say, "I can’t do this by myself." Cooking, shopping, washing, homework, tantrums, beepers, ... oh my!

I have no relatives who can help make life more manageable, but I have figured out a few things I can do. In addition to a housekeeper, I decided to enlist the help of a personal assistant – who happens to also be my hairdresser and friend – whom I can pay by the hour ($25) to do a variety of tasks around the house and run errands here and there. A few hours here and there will make a huge difference in my peace of mind. I cannot yet rule out an au pair or live-in nanny, but we are not quite ready to share our space with anyone outside our family. I am thankful, of course, that this is even an option for my household financially.

Whether you are a soon-to-be mom or dad, you too may want to think out of the box about ways to trade a hectic, disorganized life for one far more peaceful and serene, even if it comes with a price tag. What works for me may not work for you, but there is a potential solution for us all. We may just have to search hard and pay for it.

Thoughts? E-mail me at [email protected].

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

When I was a little girl, I enjoyed watching the Brady Bunch on television. For those of you under the age of 30, who may not be familiar with this hit series, Mrs. Brady, played by Florence Henderson, was a stay-at-home mother with six kids, three of her own and three of her husband’s by a prior marriage. Somehow, the house was always immaculate, the kids were always well kept, and she always managed to be level-headed, warm, and nurturing (but Alice, the housekeeper, helped a lot).

Fast forward a few decades. Now women frequently are the primary breadwinners, often working outside the home and then even more when they return after work, tethered to a computer or with smartphone in hand. This is the new work-life balance equation for many of us.

My husband and I are currently seeking to adopt a little girl in the foster care system. If we are successful in 2014, this will be our second adoption in 5 years. Anyone who has ever added to their family this way can attest to the hurdles, stumbling blocks, and utter frustration the journey can hold. In the last 8 months, I have seen thousands of photos of waiting children and found only one child in our self-defined age group (4 or younger) who does not have major developmental or physical challenges. There are over 15 other families who have also inquired about her.

I used to feel guilty that I flipped through the pictures of special-needs children quickly, but when I think about my reality as a full-time hospitalist and a mother, I know I cannot provide a special-needs child with the attention she needs. If I have a patient in the ER with unstable angina and a child at home in the midst of a seizure, I cannot exactly call into work for "family reasons." How idyllic would it be for a physician to adopt a sick child, bringing her into a home already endowed with medical expertise? On its face, and to outsiders, it would be perfect. But I have to be realistic about what I can and cannot handle, and about what choice is caring and considerate to both patients and my existing family.

While I await that life-changing call from a social worker somewhere, who has seen my family profile and thinks we would be a perfect fit for a child in her caseload, I am working toward the future. I have a glimpse of what it will be like with two small children and a demanding job, and it has the potential to be chaotic, hair-raising, and overwhelming, but it can also be calm, joyous, and well organized. I realized it is okay to say, "I can’t do this by myself." Cooking, shopping, washing, homework, tantrums, beepers, ... oh my!

I have no relatives who can help make life more manageable, but I have figured out a few things I can do. In addition to a housekeeper, I decided to enlist the help of a personal assistant – who happens to also be my hairdresser and friend – whom I can pay by the hour ($25) to do a variety of tasks around the house and run errands here and there. A few hours here and there will make a huge difference in my peace of mind. I cannot yet rule out an au pair or live-in nanny, but we are not quite ready to share our space with anyone outside our family. I am thankful, of course, that this is even an option for my household financially.

Whether you are a soon-to-be mom or dad, you too may want to think out of the box about ways to trade a hectic, disorganized life for one far more peaceful and serene, even if it comes with a price tag. What works for me may not work for you, but there is a potential solution for us all. We may just have to search hard and pay for it.

Thoughts? E-mail me at [email protected].

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Random acts of readiness in unpredictable times

My little girl had outgrown most of her Sunday dresses, so I recently took her to the mall down the street in my quiet, award-winning family-friendly city, just miles outside of Baltimore. She stocked up on a few frilly dresses, then played for a while at the indoor playground. On our way out, we stopped and bought frozen yogurt and greeted friends we knew as they walked by – a typical, uneventful day in Columbia, Md.

Just a few days later, a seemingly ordinary young man entered the mall through the same door I had used, and strolled around unnoticed, lost in a sea of eager shoppers. The rest is history. He entered a store, rifle in hand, and shot and killed two young employees, viciously robbing them, and their loved ones of decades of precious hopes, dreams, and memories. This nightmare occurred right around the time my granddaughter arrived at the Columbia Mall to begin her shift at a children’s clothing store. Fortunately, she was not injured, at least not physically.

The week before, I was saddened to learn that a teaching assistant at my alma mater, Purdue University, ruthlessly slaughtered a fellow student.

Then, I learned that a college student a couple of hours away in Pennsylvania was arrested for possession of weapons of mass destruction.

When will the madness end? It won’t. People seem to be getting more cruel and violent with each passing day.

Whether a mall in the suburbs, a marathon, a movie theater, or a university campus, the number of senseless acts of violence are skyrocketing and, one day, some of us may be called upon to provide emergency care, when we least expect it. Sure, we function well in a hospital environment when the code team, anesthesiologist, and surgeon can be summoned in a matter of seconds, but how many of us are prepared to meet the challenges of a catastrophe in our communities, in our schools, and in our social settings?

If faced with a catastrophic situation, our medical instincts would likely kick in, and we would do whatever is needed to help those in need – stabilize the spine or control the bleeding in trauma victims – but what if we are not sure what to do? What if the 911 operators are overwhelmed by terrified callers fearing for their lives?

The Centers for Disease Control maintains an Emergency Operations Center that can assist health care providers with emergency patient care: 770-488-7100. The CDC’s Clinician Outreach Communication Activity (COCA) works to ensure that clinicians have the up-to-date information they need about emerging health threats. It has posted "Emergency Preparedness: Understanding Physicians’ Concerns and Readiness to Respond," a very informative page full of resources to learn about a variety of scenarios and what we can do. (Some COCA information sessions qualify for continuing education credits.)

Local poison control centers may be of benefit in certain emergency situations as well. The National Capital Poison Center help line – 800-222-1222 – is the telephone number for every poison center in the United States.

This time, the chaos was in my backyard. Next month, God forbid, it may be in yours. No one expects unforeseen emergencies to happen, but knowing where to turn may just make a seemingly impossible situation a little more doable.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

My little girl had outgrown most of her Sunday dresses, so I recently took her to the mall down the street in my quiet, award-winning family-friendly city, just miles outside of Baltimore. She stocked up on a few frilly dresses, then played for a while at the indoor playground. On our way out, we stopped and bought frozen yogurt and greeted friends we knew as they walked by – a typical, uneventful day in Columbia, Md.

Just a few days later, a seemingly ordinary young man entered the mall through the same door I had used, and strolled around unnoticed, lost in a sea of eager shoppers. The rest is history. He entered a store, rifle in hand, and shot and killed two young employees, viciously robbing them, and their loved ones of decades of precious hopes, dreams, and memories. This nightmare occurred right around the time my granddaughter arrived at the Columbia Mall to begin her shift at a children’s clothing store. Fortunately, she was not injured, at least not physically.

The week before, I was saddened to learn that a teaching assistant at my alma mater, Purdue University, ruthlessly slaughtered a fellow student.

Then, I learned that a college student a couple of hours away in Pennsylvania was arrested for possession of weapons of mass destruction.

When will the madness end? It won’t. People seem to be getting more cruel and violent with each passing day.

Whether a mall in the suburbs, a marathon, a movie theater, or a university campus, the number of senseless acts of violence are skyrocketing and, one day, some of us may be called upon to provide emergency care, when we least expect it. Sure, we function well in a hospital environment when the code team, anesthesiologist, and surgeon can be summoned in a matter of seconds, but how many of us are prepared to meet the challenges of a catastrophe in our communities, in our schools, and in our social settings?

If faced with a catastrophic situation, our medical instincts would likely kick in, and we would do whatever is needed to help those in need – stabilize the spine or control the bleeding in trauma victims – but what if we are not sure what to do? What if the 911 operators are overwhelmed by terrified callers fearing for their lives?

The Centers for Disease Control maintains an Emergency Operations Center that can assist health care providers with emergency patient care: 770-488-7100. The CDC’s Clinician Outreach Communication Activity (COCA) works to ensure that clinicians have the up-to-date information they need about emerging health threats. It has posted "Emergency Preparedness: Understanding Physicians’ Concerns and Readiness to Respond," a very informative page full of resources to learn about a variety of scenarios and what we can do. (Some COCA information sessions qualify for continuing education credits.)

Local poison control centers may be of benefit in certain emergency situations as well. The National Capital Poison Center help line – 800-222-1222 – is the telephone number for every poison center in the United States.

This time, the chaos was in my backyard. Next month, God forbid, it may be in yours. No one expects unforeseen emergencies to happen, but knowing where to turn may just make a seemingly impossible situation a little more doable.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

My little girl had outgrown most of her Sunday dresses, so I recently took her to the mall down the street in my quiet, award-winning family-friendly city, just miles outside of Baltimore. She stocked up on a few frilly dresses, then played for a while at the indoor playground. On our way out, we stopped and bought frozen yogurt and greeted friends we knew as they walked by – a typical, uneventful day in Columbia, Md.

Just a few days later, a seemingly ordinary young man entered the mall through the same door I had used, and strolled around unnoticed, lost in a sea of eager shoppers. The rest is history. He entered a store, rifle in hand, and shot and killed two young employees, viciously robbing them, and their loved ones of decades of precious hopes, dreams, and memories. This nightmare occurred right around the time my granddaughter arrived at the Columbia Mall to begin her shift at a children’s clothing store. Fortunately, she was not injured, at least not physically.

The week before, I was saddened to learn that a teaching assistant at my alma mater, Purdue University, ruthlessly slaughtered a fellow student.

Then, I learned that a college student a couple of hours away in Pennsylvania was arrested for possession of weapons of mass destruction.

When will the madness end? It won’t. People seem to be getting more cruel and violent with each passing day.

Whether a mall in the suburbs, a marathon, a movie theater, or a university campus, the number of senseless acts of violence are skyrocketing and, one day, some of us may be called upon to provide emergency care, when we least expect it. Sure, we function well in a hospital environment when the code team, anesthesiologist, and surgeon can be summoned in a matter of seconds, but how many of us are prepared to meet the challenges of a catastrophe in our communities, in our schools, and in our social settings?

If faced with a catastrophic situation, our medical instincts would likely kick in, and we would do whatever is needed to help those in need – stabilize the spine or control the bleeding in trauma victims – but what if we are not sure what to do? What if the 911 operators are overwhelmed by terrified callers fearing for their lives?

The Centers for Disease Control maintains an Emergency Operations Center that can assist health care providers with emergency patient care: 770-488-7100. The CDC’s Clinician Outreach Communication Activity (COCA) works to ensure that clinicians have the up-to-date information they need about emerging health threats. It has posted "Emergency Preparedness: Understanding Physicians’ Concerns and Readiness to Respond," a very informative page full of resources to learn about a variety of scenarios and what we can do. (Some COCA information sessions qualify for continuing education credits.)

Local poison control centers may be of benefit in certain emergency situations as well. The National Capital Poison Center help line – 800-222-1222 – is the telephone number for every poison center in the United States.

This time, the chaos was in my backyard. Next month, God forbid, it may be in yours. No one expects unforeseen emergencies to happen, but knowing where to turn may just make a seemingly impossible situation a little more doable.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Never ‘do nothing’ at end of life

Providing end-of-life care – is one of the toughest, most painful things we are called upon to do. Who among us has not had the gut-wrenching experience of informing a spouse of 50+ years that within a few short days, their life together will come to an abrupt end? No more anniversaries. No more anything.

I don’t think physicians can truly appreciate what patients’ loved ones go through when they are dying, until we become that loved one. I got my revelation when I was the caregiver and hospice physician for a very close relative who ultimately died from cancer in my home. I had asked an oncologist friend of mine to take on her case when she relocated to live with me. To my surprise, my relative found my colleague to be rather cold and unfeeling, just when she needed a compassionate physician the most.

I deeply understand the field of medicine, had care provided by a clinician/friend, and my relative still had a subpar experience, so what must it like for those without a medical background?

I recently spoke with a friend whose elderly aunt had just passed away. In addition to the grief she felt, she had to deal with frustration and anguish about how her aunt was treated in her final days. Her aunt’s DNI (do not intubate) status was mistakenly assumed by some on her health care team to mean "DNT" (do not treat). Basic care, such as intravenous fluids in the face of inadequate oral intake, was even neglected. To add insult to injury, the family – those who actually knew her belief system, feelings, and wishes – was not allowed to partner with the health care team to create the plan for her end-of-life care.

While we often wrestle with how to talk to family, including what we should and should not say, perhaps we should begin by learning a little about the background of the family members so we can tailor our conversations to a level appropriate to their level of understanding – great or small– of health care.

We can learn a lot by talking to friends about the experiences they have when a loved one dies. How were they and their family member treated by physicians and how did they respond to that treatment? What do they wish had happened differently? What made the transition from this life more difficult and what made it easier?

My friend’s words of wisdom for hospitalists center on communication and respect: "Each patient and family should be treated as if they are Kennedys or Annenbergs from the start."

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Providing end-of-life care – is one of the toughest, most painful things we are called upon to do. Who among us has not had the gut-wrenching experience of informing a spouse of 50+ years that within a few short days, their life together will come to an abrupt end? No more anniversaries. No more anything.

I don’t think physicians can truly appreciate what patients’ loved ones go through when they are dying, until we become that loved one. I got my revelation when I was the caregiver and hospice physician for a very close relative who ultimately died from cancer in my home. I had asked an oncologist friend of mine to take on her case when she relocated to live with me. To my surprise, my relative found my colleague to be rather cold and unfeeling, just when she needed a compassionate physician the most.

I deeply understand the field of medicine, had care provided by a clinician/friend, and my relative still had a subpar experience, so what must it like for those without a medical background?

I recently spoke with a friend whose elderly aunt had just passed away. In addition to the grief she felt, she had to deal with frustration and anguish about how her aunt was treated in her final days. Her aunt’s DNI (do not intubate) status was mistakenly assumed by some on her health care team to mean "DNT" (do not treat). Basic care, such as intravenous fluids in the face of inadequate oral intake, was even neglected. To add insult to injury, the family – those who actually knew her belief system, feelings, and wishes – was not allowed to partner with the health care team to create the plan for her end-of-life care.

While we often wrestle with how to talk to family, including what we should and should not say, perhaps we should begin by learning a little about the background of the family members so we can tailor our conversations to a level appropriate to their level of understanding – great or small– of health care.

We can learn a lot by talking to friends about the experiences they have when a loved one dies. How were they and their family member treated by physicians and how did they respond to that treatment? What do they wish had happened differently? What made the transition from this life more difficult and what made it easier?

My friend’s words of wisdom for hospitalists center on communication and respect: "Each patient and family should be treated as if they are Kennedys or Annenbergs from the start."

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Providing end-of-life care – is one of the toughest, most painful things we are called upon to do. Who among us has not had the gut-wrenching experience of informing a spouse of 50+ years that within a few short days, their life together will come to an abrupt end? No more anniversaries. No more anything.

I don’t think physicians can truly appreciate what patients’ loved ones go through when they are dying, until we become that loved one. I got my revelation when I was the caregiver and hospice physician for a very close relative who ultimately died from cancer in my home. I had asked an oncologist friend of mine to take on her case when she relocated to live with me. To my surprise, my relative found my colleague to be rather cold and unfeeling, just when she needed a compassionate physician the most.

I deeply understand the field of medicine, had care provided by a clinician/friend, and my relative still had a subpar experience, so what must it like for those without a medical background?

I recently spoke with a friend whose elderly aunt had just passed away. In addition to the grief she felt, she had to deal with frustration and anguish about how her aunt was treated in her final days. Her aunt’s DNI (do not intubate) status was mistakenly assumed by some on her health care team to mean "DNT" (do not treat). Basic care, such as intravenous fluids in the face of inadequate oral intake, was even neglected. To add insult to injury, the family – those who actually knew her belief system, feelings, and wishes – was not allowed to partner with the health care team to create the plan for her end-of-life care.

While we often wrestle with how to talk to family, including what we should and should not say, perhaps we should begin by learning a little about the background of the family members so we can tailor our conversations to a level appropriate to their level of understanding – great or small– of health care.

We can learn a lot by talking to friends about the experiences they have when a loved one dies. How were they and their family member treated by physicians and how did they respond to that treatment? What do they wish had happened differently? What made the transition from this life more difficult and what made it easier?

My friend’s words of wisdom for hospitalists center on communication and respect: "Each patient and family should be treated as if they are Kennedys or Annenbergs from the start."

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Was that pressure ulcer ‘present on admission?’

Pressure ulcers have been the focus of an increasing amount of attention over the past few years, appearing everyplace from the local evening news to the government’s list of potentially preventable conditions, where they can carry a pretty steep financial penalty. When I was in residency, for some reason, they just did not seem to be such a common or important issue ... or perhaps we just didn’t pay them their due respect.

These days, they command the attention of legislators, hospital administrators, and physicians alike, not just the attention of nurses and patients, as in days past. Not long ago, the July 2, 2013, issue of Annals of Internal Medicine devoted a significant portion of an issue to the topic of pressure ulcers.

While I already knew pressure ulcers are a significant cause of morbidity, and, infrequently, mortality, I was shocked to learn the extent of this condition – an estimated 1.3 to 3 million adults in this country are affected – and that the cost to treat a pressure ulcer ranges between $37,800 and $70,000 – yes, each! The yearly cost to the U.S. health care system may be as high as $11 billion! That’s a figure I would expect to see with diabetes complications or advanced heart disease.

The article, titled "Pressure Ulcer Treatment Strategies: A Systematic Comparative Effectiveness Review," summarized evidence comparing the efficacy and safety of various treatment strategies for adults with pressure ulcers. Researchers found that using air-fluidized beds, protein supplementation, electrical stimulation, and radiant heat dressings had moderate-strength evidence for healing (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 July 2;159:39-50).

Pressure ulcer treatment and prevention are too frequently passed on to nursing staff, probably in part because physicians are busy addressing the primary cause for admission and in part because, quite frankly, the nursing staff treat the ulcers on a day-to-day basis and are more likely to have received an in-service educational session about various treatments, not to mention they are often more up-to-date on the latest formulary alternatives for treating various stages of skin breakdown.

But hospitalists should also have some skin in the game, pardon my pun.

There are simple things we can do to help the surveillance for decubitus ulcers, such as having patients turn on their sides when we listen to their lungs, instead if asking them to sit up in bed or listening anteriorly. That way we can take a quick glance at their bottoms when we auscultate their lungs. We can also reposition some patients ourselves when we see them lying in an awkward position. Asking them or their family members to take part in frequent repositioning is yet another simple task.

With the profound impact pressure ulcers can have on quality of care, risk of complications, medical costs, and even length of stay, hospitalists are in a unique position to positively influence the rate of pressure ulcer formation by having a heightened sense of awareness of our individual patient’s risk and how we can best play a major role in preventing preventable skin breakdown.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Pressure ulcers have been the focus of an increasing amount of attention over the past few years, appearing everyplace from the local evening news to the government’s list of potentially preventable conditions, where they can carry a pretty steep financial penalty. When I was in residency, for some reason, they just did not seem to be such a common or important issue ... or perhaps we just didn’t pay them their due respect.

These days, they command the attention of legislators, hospital administrators, and physicians alike, not just the attention of nurses and patients, as in days past. Not long ago, the July 2, 2013, issue of Annals of Internal Medicine devoted a significant portion of an issue to the topic of pressure ulcers.

While I already knew pressure ulcers are a significant cause of morbidity, and, infrequently, mortality, I was shocked to learn the extent of this condition – an estimated 1.3 to 3 million adults in this country are affected – and that the cost to treat a pressure ulcer ranges between $37,800 and $70,000 – yes, each! The yearly cost to the U.S. health care system may be as high as $11 billion! That’s a figure I would expect to see with diabetes complications or advanced heart disease.

The article, titled "Pressure Ulcer Treatment Strategies: A Systematic Comparative Effectiveness Review," summarized evidence comparing the efficacy and safety of various treatment strategies for adults with pressure ulcers. Researchers found that using air-fluidized beds, protein supplementation, electrical stimulation, and radiant heat dressings had moderate-strength evidence for healing (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 July 2;159:39-50).

Pressure ulcer treatment and prevention are too frequently passed on to nursing staff, probably in part because physicians are busy addressing the primary cause for admission and in part because, quite frankly, the nursing staff treat the ulcers on a day-to-day basis and are more likely to have received an in-service educational session about various treatments, not to mention they are often more up-to-date on the latest formulary alternatives for treating various stages of skin breakdown.

But hospitalists should also have some skin in the game, pardon my pun.

There are simple things we can do to help the surveillance for decubitus ulcers, such as having patients turn on their sides when we listen to their lungs, instead if asking them to sit up in bed or listening anteriorly. That way we can take a quick glance at their bottoms when we auscultate their lungs. We can also reposition some patients ourselves when we see them lying in an awkward position. Asking them or their family members to take part in frequent repositioning is yet another simple task.

With the profound impact pressure ulcers can have on quality of care, risk of complications, medical costs, and even length of stay, hospitalists are in a unique position to positively influence the rate of pressure ulcer formation by having a heightened sense of awareness of our individual patient’s risk and how we can best play a major role in preventing preventable skin breakdown.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Pressure ulcers have been the focus of an increasing amount of attention over the past few years, appearing everyplace from the local evening news to the government’s list of potentially preventable conditions, where they can carry a pretty steep financial penalty. When I was in residency, for some reason, they just did not seem to be such a common or important issue ... or perhaps we just didn’t pay them their due respect.

These days, they command the attention of legislators, hospital administrators, and physicians alike, not just the attention of nurses and patients, as in days past. Not long ago, the July 2, 2013, issue of Annals of Internal Medicine devoted a significant portion of an issue to the topic of pressure ulcers.

While I already knew pressure ulcers are a significant cause of morbidity, and, infrequently, mortality, I was shocked to learn the extent of this condition – an estimated 1.3 to 3 million adults in this country are affected – and that the cost to treat a pressure ulcer ranges between $37,800 and $70,000 – yes, each! The yearly cost to the U.S. health care system may be as high as $11 billion! That’s a figure I would expect to see with diabetes complications or advanced heart disease.

The article, titled "Pressure Ulcer Treatment Strategies: A Systematic Comparative Effectiveness Review," summarized evidence comparing the efficacy and safety of various treatment strategies for adults with pressure ulcers. Researchers found that using air-fluidized beds, protein supplementation, electrical stimulation, and radiant heat dressings had moderate-strength evidence for healing (Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 July 2;159:39-50).

Pressure ulcer treatment and prevention are too frequently passed on to nursing staff, probably in part because physicians are busy addressing the primary cause for admission and in part because, quite frankly, the nursing staff treat the ulcers on a day-to-day basis and are more likely to have received an in-service educational session about various treatments, not to mention they are often more up-to-date on the latest formulary alternatives for treating various stages of skin breakdown.

But hospitalists should also have some skin in the game, pardon my pun.

There are simple things we can do to help the surveillance for decubitus ulcers, such as having patients turn on their sides when we listen to their lungs, instead if asking them to sit up in bed or listening anteriorly. That way we can take a quick glance at their bottoms when we auscultate their lungs. We can also reposition some patients ourselves when we see them lying in an awkward position. Asking them or their family members to take part in frequent repositioning is yet another simple task.

With the profound impact pressure ulcers can have on quality of care, risk of complications, medical costs, and even length of stay, hospitalists are in a unique position to positively influence the rate of pressure ulcer formation by having a heightened sense of awareness of our individual patient’s risk and how we can best play a major role in preventing preventable skin breakdown.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Pay disparities and gender

As we all know, a healthy work-life balance can be very difficult to achieve, let alone maintain. That is why many of us got into hospital medicine in the first place.

When studies show that in America, male hospitalists make more on average than their female counterparts, it is assumed that there is a strong correlation between hours worked and pay. But could there be other factors as well? In Canada, at least, that seems to be the case. A research team at the University of Montreal reviewed the billing information of 870 Quebec practitioners with a focus on procedures in elderly diabetic patients. Male and female practitioners were equally represented. The results: Female doctors were far more compliant with the Canadian Diabetes Association practice guidelines, but males were more productive when it came to procedures.

Specifically, male physicians reported close to 1,000 more procedures annually compared with female physicians. So, the question comes to mind: Who is more profitable for hospitals, physicians who perform more procedures that can be billed at a higher rate, or those who seem to focus more attention on the bread and butter of care, so to speak? After all, if patients understand their condition and get the appropriate care, aren't they less likely to require rehospitalization? No definitive answers yet, but this study does make you want to go, "Hmm."

While the U.S. health care system certainly differs from Canada's, this article does bring up intriguing issues, some which just may be worth considering as we assess and improve the practice styles and compensation models for hospitalists. A 2012 Today's Hospitalist survey cited in an article titled, "Why do women hospitalists make less money?" sheds additional light on the subject. Yes, there is still a gender gap between male and female physicians. There are numerous hypotheses, as well as some hard data to explain some of these differences, though many still believe part of the issue is a persistent gender bias.

The article noted that males work a few more shifts than females, 16.68 vs 15.96, but this is only a 5% difference in work hours. Other data support a compensation difference based on the different payment models. Slightly more men are in a payment model that is 100% productivity-based or a combination of salary and productivity, and these models tend to pay more than do positions that are straight salary. Still, for a variety of reasons, some clear and others obscure, female hospitalists earn an average of $35,000 less than do their male counterparts.

Acknowledging a disparity exists is not enough. The reasons for this disparity should be further evaluated and addressed. Perhaps they are strongly the result of lifestyle choices, types of positions females prefer, and other nongender-related issues, but we owe it ourselves to gain further clarity on this very real issue.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

As we all know, a healthy work-life balance can be very difficult to achieve, let alone maintain. That is why many of us got into hospital medicine in the first place.

When studies show that in America, male hospitalists make more on average than their female counterparts, it is assumed that there is a strong correlation between hours worked and pay. But could there be other factors as well? In Canada, at least, that seems to be the case. A research team at the University of Montreal reviewed the billing information of 870 Quebec practitioners with a focus on procedures in elderly diabetic patients. Male and female practitioners were equally represented. The results: Female doctors were far more compliant with the Canadian Diabetes Association practice guidelines, but males were more productive when it came to procedures.

Specifically, male physicians reported close to 1,000 more procedures annually compared with female physicians. So, the question comes to mind: Who is more profitable for hospitals, physicians who perform more procedures that can be billed at a higher rate, or those who seem to focus more attention on the bread and butter of care, so to speak? After all, if patients understand their condition and get the appropriate care, aren't they less likely to require rehospitalization? No definitive answers yet, but this study does make you want to go, "Hmm."

While the U.S. health care system certainly differs from Canada's, this article does bring up intriguing issues, some which just may be worth considering as we assess and improve the practice styles and compensation models for hospitalists. A 2012 Today's Hospitalist survey cited in an article titled, "Why do women hospitalists make less money?" sheds additional light on the subject. Yes, there is still a gender gap between male and female physicians. There are numerous hypotheses, as well as some hard data to explain some of these differences, though many still believe part of the issue is a persistent gender bias.

The article noted that males work a few more shifts than females, 16.68 vs 15.96, but this is only a 5% difference in work hours. Other data support a compensation difference based on the different payment models. Slightly more men are in a payment model that is 100% productivity-based or a combination of salary and productivity, and these models tend to pay more than do positions that are straight salary. Still, for a variety of reasons, some clear and others obscure, female hospitalists earn an average of $35,000 less than do their male counterparts.

Acknowledging a disparity exists is not enough. The reasons for this disparity should be further evaluated and addressed. Perhaps they are strongly the result of lifestyle choices, types of positions females prefer, and other nongender-related issues, but we owe it ourselves to gain further clarity on this very real issue.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

As we all know, a healthy work-life balance can be very difficult to achieve, let alone maintain. That is why many of us got into hospital medicine in the first place.

When studies show that in America, male hospitalists make more on average than their female counterparts, it is assumed that there is a strong correlation between hours worked and pay. But could there be other factors as well? In Canada, at least, that seems to be the case. A research team at the University of Montreal reviewed the billing information of 870 Quebec practitioners with a focus on procedures in elderly diabetic patients. Male and female practitioners were equally represented. The results: Female doctors were far more compliant with the Canadian Diabetes Association practice guidelines, but males were more productive when it came to procedures.

Specifically, male physicians reported close to 1,000 more procedures annually compared with female physicians. So, the question comes to mind: Who is more profitable for hospitals, physicians who perform more procedures that can be billed at a higher rate, or those who seem to focus more attention on the bread and butter of care, so to speak? After all, if patients understand their condition and get the appropriate care, aren't they less likely to require rehospitalization? No definitive answers yet, but this study does make you want to go, "Hmm."

While the U.S. health care system certainly differs from Canada's, this article does bring up intriguing issues, some which just may be worth considering as we assess and improve the practice styles and compensation models for hospitalists. A 2012 Today's Hospitalist survey cited in an article titled, "Why do women hospitalists make less money?" sheds additional light on the subject. Yes, there is still a gender gap between male and female physicians. There are numerous hypotheses, as well as some hard data to explain some of these differences, though many still believe part of the issue is a persistent gender bias.

The article noted that males work a few more shifts than females, 16.68 vs 15.96, but this is only a 5% difference in work hours. Other data support a compensation difference based on the different payment models. Slightly more men are in a payment model that is 100% productivity-based or a combination of salary and productivity, and these models tend to pay more than do positions that are straight salary. Still, for a variety of reasons, some clear and others obscure, female hospitalists earn an average of $35,000 less than do their male counterparts.

Acknowledging a disparity exists is not enough. The reasons for this disparity should be further evaluated and addressed. Perhaps they are strongly the result of lifestyle choices, types of positions females prefer, and other nongender-related issues, but we owe it ourselves to gain further clarity on this very real issue.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

The RAC man cometh

If you have never heard of the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program, it’s only a matter of time. A little bit of history is in order here. Between 2005 and 2008, a demonstration program that used Recovery Auditors identified Medicare overpayments, as well as underpayments, to both providers and suppliers of health care in random states. The result was that a whopping $900 million in overpayments was returned to the Medicare Trust Fund, while close to $38 million in underpayments was given to health care providers.

Obviously, this program was a tremendous success for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and it has since taken off in all 50 states. And, you guessed it, it remains a great boon for the Medicare Trust Fund.

In fiscal year 2010, $75.4 million in overpayments was collected, and $16.9 million returned, and in fiscal year 2013, $2.2 billion in overpayments was collected, while $370 million was returned. Since the program’s inception, there has been $5.7 billion in total corrections, of which, $5.4 billion was collected from overpayments.

Surprised? I think most of us, and our hospitals, could benefit by hospitalists learning more about the RAC and what we could do to guard against a successful audit and penalty. The Program for Evaluating Payment Patterns Electronic Report (PEPPER) provides provider-specific Medicare data stats for discharges and services that are vulnerable. Pepperresources.org was developed by TMF Health Quality Institute, which was contracted by the CMS.

PEPPER has many uses, but one of the most useful for hospitals is to compare its claims data over time to identify concerning trends, such as significant changes in billing practices, increasing length of stay, and over- or undercoding. In 2013, practicing good medicine just isn’t enough. You have to make sure you are documenting appropriately to justify the codes you bill. Outliers beware!

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

If you have never heard of the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program, it’s only a matter of time. A little bit of history is in order here. Between 2005 and 2008, a demonstration program that used Recovery Auditors identified Medicare overpayments, as well as underpayments, to both providers and suppliers of health care in random states. The result was that a whopping $900 million in overpayments was returned to the Medicare Trust Fund, while close to $38 million in underpayments was given to health care providers.

Obviously, this program was a tremendous success for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and it has since taken off in all 50 states. And, you guessed it, it remains a great boon for the Medicare Trust Fund.

In fiscal year 2010, $75.4 million in overpayments was collected, and $16.9 million returned, and in fiscal year 2013, $2.2 billion in overpayments was collected, while $370 million was returned. Since the program’s inception, there has been $5.7 billion in total corrections, of which, $5.4 billion was collected from overpayments.

Surprised? I think most of us, and our hospitals, could benefit by hospitalists learning more about the RAC and what we could do to guard against a successful audit and penalty. The Program for Evaluating Payment Patterns Electronic Report (PEPPER) provides provider-specific Medicare data stats for discharges and services that are vulnerable. Pepperresources.org was developed by TMF Health Quality Institute, which was contracted by the CMS.

PEPPER has many uses, but one of the most useful for hospitals is to compare its claims data over time to identify concerning trends, such as significant changes in billing practices, increasing length of stay, and over- or undercoding. In 2013, practicing good medicine just isn’t enough. You have to make sure you are documenting appropriately to justify the codes you bill. Outliers beware!

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

If you have never heard of the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program, it’s only a matter of time. A little bit of history is in order here. Between 2005 and 2008, a demonstration program that used Recovery Auditors identified Medicare overpayments, as well as underpayments, to both providers and suppliers of health care in random states. The result was that a whopping $900 million in overpayments was returned to the Medicare Trust Fund, while close to $38 million in underpayments was given to health care providers.

Obviously, this program was a tremendous success for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and it has since taken off in all 50 states. And, you guessed it, it remains a great boon for the Medicare Trust Fund.

In fiscal year 2010, $75.4 million in overpayments was collected, and $16.9 million returned, and in fiscal year 2013, $2.2 billion in overpayments was collected, while $370 million was returned. Since the program’s inception, there has been $5.7 billion in total corrections, of which, $5.4 billion was collected from overpayments.

Surprised? I think most of us, and our hospitals, could benefit by hospitalists learning more about the RAC and what we could do to guard against a successful audit and penalty. The Program for Evaluating Payment Patterns Electronic Report (PEPPER) provides provider-specific Medicare data stats for discharges and services that are vulnerable. Pepperresources.org was developed by TMF Health Quality Institute, which was contracted by the CMS.

PEPPER has many uses, but one of the most useful for hospitals is to compare its claims data over time to identify concerning trends, such as significant changes in billing practices, increasing length of stay, and over- or undercoding. In 2013, practicing good medicine just isn’t enough. You have to make sure you are documenting appropriately to justify the codes you bill. Outliers beware!

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Treating the psych side

Stepping in to prevent future tragedies like the mass shooting at the D.C. Navy Yard

Words could never adequately describe the grief and astonishment most of us feel about the massacre of 12 innocent people that took place in the Navy Yard in Washington on Sept. 16. We can identify with the victims, just ordinary people going about their ordinary routines. They were just like us. This could happen anywhere, anytime.

What makes a person snap and go on a shooting rampage with the intent to slaughter innocent people, and how can these tragedies be prevented in the future? According to news reports, the father of Aaron Alexis said the shooter suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He participated in the search-and-rescue efforts after that tragic event. Subsequent to 9/11 he had his first documented violent outburst when he shot out the tires of a construction worker who he felt had disrespected him.