User login

New frontline treatments needed for Hodgkin lymphoma

In this editorial, Anna Sureda, MD, PhD, details the need for new frontline treatments for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, including those with advanced stage disease.

Dr Sureda is head of the Hematology Department and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Programme at the Institut Català d'Oncologia, Hospital Duran i Reynals, in Barcelona, Spain. She has received consultancy fees from Takeda/Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Hodgkin lymphoma has traditionally been known as a cancer with generally favorable outcomes. Yet, as with any cancer treatment, there is always room for improvement. For Hodgkin lymphoma specifically, there remains a significant unmet need in the frontline setting for patients with advanced disease (Stage III or Stage IV).

Hodgkin lymphoma most commonly affects young adults as well as adults over the age of 55.1 Both age at diagnosis and stage of the disease are significant factors that must be considered when determining treatment plans, as they can affect a patient’s success in achieving long-term remission.

Though early stage patients have demonstrated 5-year survival rates of approximately 90%, this number drops to 70% in patients with advanced stage disease,2-4 underlining the challenges of treating later stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Additionally, only 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease will experience long-term remission with high-dose chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)5-6— a historically and frequently used treatment regimen.

These facts support the importance of successful frontline treatment and highlight a gap with current treatment regimens.7-10

With current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatments, it can be a challenge for physicians to balance efficacy with safety. While allowing the patient to achieve long-term remission remains the goal, physicians are also considering the impact of treatment-related side effects including endocrine dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, lung toxicity, infertility, and an increased risk of secondary cancers when determining the best possible treatment.8-15

Advanced stage vs early stage Hodgkin lymphoma

Stage of disease at diagnosis has a large influence on outcomes, with advanced stage patients having poorer outcomes than earlier stage patients.7,15-16 Advanced Hodgkin lymphoma patients are more likely to progress or relapse,7,15-16 with nearly one third remaining uncured following standard frontline therapy.7-10

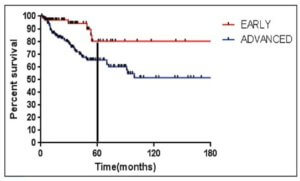

As seen in Figure 1 below, there is a clear difference in progression-free survival for early versus advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma.16

The difference between early stage and advanced stage patients treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) demonstrates the heightened importance of successful frontline treatment for those with advanced stage disease.16

Unmet needs with current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Though current treatments for frontline Hodgkin lymphoma, including ABVD and bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP), have improved outcomes for patients, these standard regimens are more than 20 years old.

ABVD is generally regarded as the treatment of choice based on its efficacy, relative ease of administration, and side effect profile.17

Escalated BEACOPP, on the other hand, was developed to improve outcomes for advanced stage patients but is associated with increased toxicity.8-10,13,18

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans have also been identified as a pathway to help guide further treatment, but patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma may relapse more often, despite a negative interim PET scan, compared to stage II patients.19

Among current treatments, side effects including lung and cardiotoxicity as well as an increased risk of secondary cancers are a concern for both physicians and their patients.8-10,13-15

Similarly, radiation therapy, often used in conjunction with chemotherapy for patients who have a large tumor burden in one part of the body, usually the chest,20 is also associated with an increased risk of secondary cancers and cardiotoxicity.8-10,21

With these complications in mind, stabilizing the effects between improved efficacy and minimizing the toxicities associated with current frontline treatments needs to be a focus as new therapies are developed.

For young patients specifically, minimizing toxicities is crucial, as many will have a lifetime ahead of them after Hodgkin lymphoma and will want to avoid the risks associated with current treatments including lung disease, heart disease and infertility.8-10,12-15,22

Treating elderly patients can also be challenging due to their reduced ability to tolerate aggressive frontline treatment and multi-agent chemotherapy, which causes inferior survival outcomes when compared to younger patients.23-25 These secondary effects can affect a patient’s quality of life8-9,12,14-15,22,26-28 and exacerbate preexisting conditions commonly experienced by those undergoing treatment, including long-term fatigue, chronic medical and psychosocial complications, and general deterioration in physical well-being.22

Studies have shown that most relapses after ASCT typically occur within 2 years.29 After a relapse, the patient may endure a substantial physical and psychological burden due to the need for additional treatment, impacting quality of life for both the patient and their caregiver.22,26,30

Goals of clinical research

Despite its recognition as a highly treatable cancer, newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma remains incurable in up to 30% of patients with advanced disease.7-10 Though current therapies seek to achieve remission and extend the lives of patients, it is often at the cost of treatment-related toxicities and side effects that can significantly reduce quality of life.

Moving forward, it is critical that these gaps in treatment are addressed in new frontline treatments that aim to benefit patients, including those with advanced stage disease, while reducing short-term and long-term toxicities. ![]()

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the W2O Group for their writing support, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

______________________________________________________

1American Cancer Society. What Are the Key Statistics About Hodgkin Disease? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

2Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J (editors). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, NIH Pub. No. 07-6215, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

3American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Hodgkin Disease by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

4Fermé C, et al. New Engl J Med, 2007.357:1916–27.

5Sureda A, et al. Ann Oncol, 2005;16: 625–633.

6Majhail NS, et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2006;12:1065–1072.

7Gordon LI, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:684-691.

8Carde P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2016;34(17):2028-2036.

9Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2009;27(27):4548-4554

10Viviani S, et al. New Engl J Med, 2011;365(3):203-212.

11Sklar C, et al. J Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2000;85(9):3227-3232

12Behringer K, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:231-239.

13Borchmann P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2011;29(32):4234-4242.

14Duggan DB, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(4):607-614.

15Johnson P, McKenzie H. Blood, 2015;125(11):1717-1723.

16Maddi RN, et al. Indian J Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015;36(4):255-260

17Ansell SM. American Journal of Hematology, 2014;89: 771–779.

18Merli F, et al. J Clin Oncol, 34:1175-1181.

19Johnson P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419‑2429

20American Cancer Society. Treating Hodgkin Disease: Radiation Therapy for Hodgkin Disease. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/treating/radiation.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

21Adams MJ, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2004; 22: 3139–48.

22Khimani N, et al. Ann Oncol, 2013;24(1):226-230.

23Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2005;23(22):5052-60.

24Evens AM, et al. Br J Haematol, 2013;161: 76–86.

25Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Br J Haematol, 2005;129:597-606.

26Ganz PA et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(18):3512-3519.

27Daniels LA, et al. Br J Cancer 2014;110:868-874.

28Loge JH, et al. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:71-77.

29Brusamolino E, Carella AM. Haematologica, 2007;92:6-10

30Consolidation Therapy After ASCT in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Why and Who to Treat? Personalized Medicine in Oncology, 2016. http://www.personalizedmedonc.com/article/consolidation-therapy-after-asct-in-hodgkin-lymphoma-why-and-who-to-treat/. Accessed February 16, 2017.

In this editorial, Anna Sureda, MD, PhD, details the need for new frontline treatments for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, including those with advanced stage disease.

Dr Sureda is head of the Hematology Department and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Programme at the Institut Català d'Oncologia, Hospital Duran i Reynals, in Barcelona, Spain. She has received consultancy fees from Takeda/Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Hodgkin lymphoma has traditionally been known as a cancer with generally favorable outcomes. Yet, as with any cancer treatment, there is always room for improvement. For Hodgkin lymphoma specifically, there remains a significant unmet need in the frontline setting for patients with advanced disease (Stage III or Stage IV).

Hodgkin lymphoma most commonly affects young adults as well as adults over the age of 55.1 Both age at diagnosis and stage of the disease are significant factors that must be considered when determining treatment plans, as they can affect a patient’s success in achieving long-term remission.

Though early stage patients have demonstrated 5-year survival rates of approximately 90%, this number drops to 70% in patients with advanced stage disease,2-4 underlining the challenges of treating later stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Additionally, only 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease will experience long-term remission with high-dose chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)5-6— a historically and frequently used treatment regimen.

These facts support the importance of successful frontline treatment and highlight a gap with current treatment regimens.7-10

With current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatments, it can be a challenge for physicians to balance efficacy with safety. While allowing the patient to achieve long-term remission remains the goal, physicians are also considering the impact of treatment-related side effects including endocrine dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, lung toxicity, infertility, and an increased risk of secondary cancers when determining the best possible treatment.8-15

Advanced stage vs early stage Hodgkin lymphoma

Stage of disease at diagnosis has a large influence on outcomes, with advanced stage patients having poorer outcomes than earlier stage patients.7,15-16 Advanced Hodgkin lymphoma patients are more likely to progress or relapse,7,15-16 with nearly one third remaining uncured following standard frontline therapy.7-10

As seen in Figure 1 below, there is a clear difference in progression-free survival for early versus advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma.16

The difference between early stage and advanced stage patients treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) demonstrates the heightened importance of successful frontline treatment for those with advanced stage disease.16

Unmet needs with current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Though current treatments for frontline Hodgkin lymphoma, including ABVD and bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP), have improved outcomes for patients, these standard regimens are more than 20 years old.

ABVD is generally regarded as the treatment of choice based on its efficacy, relative ease of administration, and side effect profile.17

Escalated BEACOPP, on the other hand, was developed to improve outcomes for advanced stage patients but is associated with increased toxicity.8-10,13,18

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans have also been identified as a pathway to help guide further treatment, but patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma may relapse more often, despite a negative interim PET scan, compared to stage II patients.19

Among current treatments, side effects including lung and cardiotoxicity as well as an increased risk of secondary cancers are a concern for both physicians and their patients.8-10,13-15

Similarly, radiation therapy, often used in conjunction with chemotherapy for patients who have a large tumor burden in one part of the body, usually the chest,20 is also associated with an increased risk of secondary cancers and cardiotoxicity.8-10,21

With these complications in mind, stabilizing the effects between improved efficacy and minimizing the toxicities associated with current frontline treatments needs to be a focus as new therapies are developed.

For young patients specifically, minimizing toxicities is crucial, as many will have a lifetime ahead of them after Hodgkin lymphoma and will want to avoid the risks associated with current treatments including lung disease, heart disease and infertility.8-10,12-15,22

Treating elderly patients can also be challenging due to their reduced ability to tolerate aggressive frontline treatment and multi-agent chemotherapy, which causes inferior survival outcomes when compared to younger patients.23-25 These secondary effects can affect a patient’s quality of life8-9,12,14-15,22,26-28 and exacerbate preexisting conditions commonly experienced by those undergoing treatment, including long-term fatigue, chronic medical and psychosocial complications, and general deterioration in physical well-being.22

Studies have shown that most relapses after ASCT typically occur within 2 years.29 After a relapse, the patient may endure a substantial physical and psychological burden due to the need for additional treatment, impacting quality of life for both the patient and their caregiver.22,26,30

Goals of clinical research

Despite its recognition as a highly treatable cancer, newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma remains incurable in up to 30% of patients with advanced disease.7-10 Though current therapies seek to achieve remission and extend the lives of patients, it is often at the cost of treatment-related toxicities and side effects that can significantly reduce quality of life.

Moving forward, it is critical that these gaps in treatment are addressed in new frontline treatments that aim to benefit patients, including those with advanced stage disease, while reducing short-term and long-term toxicities. ![]()

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the W2O Group for their writing support, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

______________________________________________________

1American Cancer Society. What Are the Key Statistics About Hodgkin Disease? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

2Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J (editors). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, NIH Pub. No. 07-6215, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

3American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Hodgkin Disease by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

4Fermé C, et al. New Engl J Med, 2007.357:1916–27.

5Sureda A, et al. Ann Oncol, 2005;16: 625–633.

6Majhail NS, et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2006;12:1065–1072.

7Gordon LI, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:684-691.

8Carde P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2016;34(17):2028-2036.

9Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2009;27(27):4548-4554

10Viviani S, et al. New Engl J Med, 2011;365(3):203-212.

11Sklar C, et al. J Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2000;85(9):3227-3232

12Behringer K, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:231-239.

13Borchmann P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2011;29(32):4234-4242.

14Duggan DB, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(4):607-614.

15Johnson P, McKenzie H. Blood, 2015;125(11):1717-1723.

16Maddi RN, et al. Indian J Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015;36(4):255-260

17Ansell SM. American Journal of Hematology, 2014;89: 771–779.

18Merli F, et al. J Clin Oncol, 34:1175-1181.

19Johnson P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419‑2429

20American Cancer Society. Treating Hodgkin Disease: Radiation Therapy for Hodgkin Disease. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/treating/radiation.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

21Adams MJ, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2004; 22: 3139–48.

22Khimani N, et al. Ann Oncol, 2013;24(1):226-230.

23Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2005;23(22):5052-60.

24Evens AM, et al. Br J Haematol, 2013;161: 76–86.

25Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Br J Haematol, 2005;129:597-606.

26Ganz PA et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(18):3512-3519.

27Daniels LA, et al. Br J Cancer 2014;110:868-874.

28Loge JH, et al. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:71-77.

29Brusamolino E, Carella AM. Haematologica, 2007;92:6-10

30Consolidation Therapy After ASCT in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Why and Who to Treat? Personalized Medicine in Oncology, 2016. http://www.personalizedmedonc.com/article/consolidation-therapy-after-asct-in-hodgkin-lymphoma-why-and-who-to-treat/. Accessed February 16, 2017.

In this editorial, Anna Sureda, MD, PhD, details the need for new frontline treatments for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, including those with advanced stage disease.

Dr Sureda is head of the Hematology Department and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Programme at the Institut Català d'Oncologia, Hospital Duran i Reynals, in Barcelona, Spain. She has received consultancy fees from Takeda/Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Hodgkin lymphoma has traditionally been known as a cancer with generally favorable outcomes. Yet, as with any cancer treatment, there is always room for improvement. For Hodgkin lymphoma specifically, there remains a significant unmet need in the frontline setting for patients with advanced disease (Stage III or Stage IV).

Hodgkin lymphoma most commonly affects young adults as well as adults over the age of 55.1 Both age at diagnosis and stage of the disease are significant factors that must be considered when determining treatment plans, as they can affect a patient’s success in achieving long-term remission.

Though early stage patients have demonstrated 5-year survival rates of approximately 90%, this number drops to 70% in patients with advanced stage disease,2-4 underlining the challenges of treating later stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Additionally, only 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease will experience long-term remission with high-dose chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)5-6— a historically and frequently used treatment regimen.

These facts support the importance of successful frontline treatment and highlight a gap with current treatment regimens.7-10

With current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatments, it can be a challenge for physicians to balance efficacy with safety. While allowing the patient to achieve long-term remission remains the goal, physicians are also considering the impact of treatment-related side effects including endocrine dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, lung toxicity, infertility, and an increased risk of secondary cancers when determining the best possible treatment.8-15

Advanced stage vs early stage Hodgkin lymphoma

Stage of disease at diagnosis has a large influence on outcomes, with advanced stage patients having poorer outcomes than earlier stage patients.7,15-16 Advanced Hodgkin lymphoma patients are more likely to progress or relapse,7,15-16 with nearly one third remaining uncured following standard frontline therapy.7-10

As seen in Figure 1 below, there is a clear difference in progression-free survival for early versus advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma.16

The difference between early stage and advanced stage patients treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) demonstrates the heightened importance of successful frontline treatment for those with advanced stage disease.16

Unmet needs with current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Though current treatments for frontline Hodgkin lymphoma, including ABVD and bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP), have improved outcomes for patients, these standard regimens are more than 20 years old.

ABVD is generally regarded as the treatment of choice based on its efficacy, relative ease of administration, and side effect profile.17

Escalated BEACOPP, on the other hand, was developed to improve outcomes for advanced stage patients but is associated with increased toxicity.8-10,13,18

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans have also been identified as a pathway to help guide further treatment, but patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma may relapse more often, despite a negative interim PET scan, compared to stage II patients.19

Among current treatments, side effects including lung and cardiotoxicity as well as an increased risk of secondary cancers are a concern for both physicians and their patients.8-10,13-15

Similarly, radiation therapy, often used in conjunction with chemotherapy for patients who have a large tumor burden in one part of the body, usually the chest,20 is also associated with an increased risk of secondary cancers and cardiotoxicity.8-10,21

With these complications in mind, stabilizing the effects between improved efficacy and minimizing the toxicities associated with current frontline treatments needs to be a focus as new therapies are developed.

For young patients specifically, minimizing toxicities is crucial, as many will have a lifetime ahead of them after Hodgkin lymphoma and will want to avoid the risks associated with current treatments including lung disease, heart disease and infertility.8-10,12-15,22

Treating elderly patients can also be challenging due to their reduced ability to tolerate aggressive frontline treatment and multi-agent chemotherapy, which causes inferior survival outcomes when compared to younger patients.23-25 These secondary effects can affect a patient’s quality of life8-9,12,14-15,22,26-28 and exacerbate preexisting conditions commonly experienced by those undergoing treatment, including long-term fatigue, chronic medical and psychosocial complications, and general deterioration in physical well-being.22

Studies have shown that most relapses after ASCT typically occur within 2 years.29 After a relapse, the patient may endure a substantial physical and psychological burden due to the need for additional treatment, impacting quality of life for both the patient and their caregiver.22,26,30

Goals of clinical research

Despite its recognition as a highly treatable cancer, newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma remains incurable in up to 30% of patients with advanced disease.7-10 Though current therapies seek to achieve remission and extend the lives of patients, it is often at the cost of treatment-related toxicities and side effects that can significantly reduce quality of life.

Moving forward, it is critical that these gaps in treatment are addressed in new frontline treatments that aim to benefit patients, including those with advanced stage disease, while reducing short-term and long-term toxicities. ![]()

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the W2O Group for their writing support, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

______________________________________________________

1American Cancer Society. What Are the Key Statistics About Hodgkin Disease? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

2Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J (editors). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, NIH Pub. No. 07-6215, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

3American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Hodgkin Disease by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

4Fermé C, et al. New Engl J Med, 2007.357:1916–27.

5Sureda A, et al. Ann Oncol, 2005;16: 625–633.

6Majhail NS, et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2006;12:1065–1072.

7Gordon LI, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:684-691.

8Carde P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2016;34(17):2028-2036.

9Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2009;27(27):4548-4554

10Viviani S, et al. New Engl J Med, 2011;365(3):203-212.

11Sklar C, et al. J Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2000;85(9):3227-3232

12Behringer K, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:231-239.

13Borchmann P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2011;29(32):4234-4242.

14Duggan DB, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(4):607-614.

15Johnson P, McKenzie H. Blood, 2015;125(11):1717-1723.

16Maddi RN, et al. Indian J Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015;36(4):255-260

17Ansell SM. American Journal of Hematology, 2014;89: 771–779.

18Merli F, et al. J Clin Oncol, 34:1175-1181.

19Johnson P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419‑2429

20American Cancer Society. Treating Hodgkin Disease: Radiation Therapy for Hodgkin Disease. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/treating/radiation.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

21Adams MJ, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2004; 22: 3139–48.

22Khimani N, et al. Ann Oncol, 2013;24(1):226-230.

23Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2005;23(22):5052-60.

24Evens AM, et al. Br J Haematol, 2013;161: 76–86.

25Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Br J Haematol, 2005;129:597-606.

26Ganz PA et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(18):3512-3519.

27Daniels LA, et al. Br J Cancer 2014;110:868-874.

28Loge JH, et al. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:71-77.

29Brusamolino E, Carella AM. Haematologica, 2007;92:6-10

30Consolidation Therapy After ASCT in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Why and Who to Treat? Personalized Medicine in Oncology, 2016. http://www.personalizedmedonc.com/article/consolidation-therapy-after-asct-in-hodgkin-lymphoma-why-and-who-to-treat/. Accessed February 16, 2017.

Len plus anti-CD19 Mab MOR208 active against advanced DLBCL

LUGANO, SWITZERLAND – Combining lenalidomide (Revlimid) with an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody labeled MOR208 showed promising activity in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who were ineligible for stem cell transplant and had poor prognosis, early interim results from a clinical study indicate.

Among 34 patients evaluable for response, the preliminary objective response rate (ORR) was 56%, including complete responses in 32% of patients, reported Gilles Salles, MD, PhD, of the University of Lyon, France.

MOR208 is a humanized anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody with the Fc-antibody region enhanced to improve cytotoxicity. Its mechanisms of action include natural killer cell–mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, and direct cytotoxicity.

In a preclinical study, a combination of MOR208 and lenalidomide showed synergistic antileukemic and antilymphoma activity both in vivo and in vitro, Dr. Salles said.

In addition, both lenalidomide and MOR208 have shown significant activity against relapsed, refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

In an ongoing phase II, open-label study, Dr. Salles and his colleagues are enrolling transplant-ineligible patients 18 years and older with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status 0-2, and adequate organ function who had disease progression after 1-3 prior lines of therapy.

Patients with primary refractory DLBCL, double-hit or triple-hit DLBCL (i.e., mutations in Myc, BCL2, and/or BCL6), other NHL histological subtypes, or central nervous system lymphoma involvement are excluded.

Patients receive MOR208 12 mg/kg intravenously on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for cycles 1-3 and on days 1 and 15 of cycles 4-12. Lenalidomide 25 mg orally is delivered on days 1-21 of each cycle. Patients who have stable disease or better at the end of 12 cycles can be maintained on MOR208 at the same dose on days 1 and 15.

As of the data cutoff on March 6, 2017, 44 patients had been enrolled, and 34 were evaluable for response. The median patient age was 73 years (range, 47-82 years).

At the time of the data presentation, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 56%, consisting of 32% complete responses (11 patients), 24% partial responses (8), 12% stable disease (4), and 32% of patients who either had disease progression or had not yet had a postbaseline response assessment.

The median time to response was 1.8 months, with a median time to complete response of 3.4 months. Of 19 responders, 16 continue to have a response, including 10 of 11 patients with complete responses.

The most common grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Nonhematologic toxicities of any grade included rashes in 20% of patients, pyrexia in 16%, diarrhea in 16%, asthenia in 14%, and pneumonia, bronchitis, and nausea in 11% each.

There were no reported infusion-related reactions with the antibody. In all, 27% of patients required a lenalidomide dose reduction – to 20 mg/day in 20% of patients and to 15 mg/day in 7%.

Study accrual, follow-up of patients on therapy, investigations of cell origin, and subgroup analyses are ongoing.

MorphoSys is sponsoring the study. Dr. Salles has received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche/Genentech, and Servier and is an advisor/consultant to many of the same companies.

LUGANO, SWITZERLAND – Combining lenalidomide (Revlimid) with an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody labeled MOR208 showed promising activity in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who were ineligible for stem cell transplant and had poor prognosis, early interim results from a clinical study indicate.

Among 34 patients evaluable for response, the preliminary objective response rate (ORR) was 56%, including complete responses in 32% of patients, reported Gilles Salles, MD, PhD, of the University of Lyon, France.

MOR208 is a humanized anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody with the Fc-antibody region enhanced to improve cytotoxicity. Its mechanisms of action include natural killer cell–mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, and direct cytotoxicity.

In a preclinical study, a combination of MOR208 and lenalidomide showed synergistic antileukemic and antilymphoma activity both in vivo and in vitro, Dr. Salles said.

In addition, both lenalidomide and MOR208 have shown significant activity against relapsed, refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

In an ongoing phase II, open-label study, Dr. Salles and his colleagues are enrolling transplant-ineligible patients 18 years and older with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status 0-2, and adequate organ function who had disease progression after 1-3 prior lines of therapy.

Patients with primary refractory DLBCL, double-hit or triple-hit DLBCL (i.e., mutations in Myc, BCL2, and/or BCL6), other NHL histological subtypes, or central nervous system lymphoma involvement are excluded.

Patients receive MOR208 12 mg/kg intravenously on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for cycles 1-3 and on days 1 and 15 of cycles 4-12. Lenalidomide 25 mg orally is delivered on days 1-21 of each cycle. Patients who have stable disease or better at the end of 12 cycles can be maintained on MOR208 at the same dose on days 1 and 15.

As of the data cutoff on March 6, 2017, 44 patients had been enrolled, and 34 were evaluable for response. The median patient age was 73 years (range, 47-82 years).

At the time of the data presentation, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 56%, consisting of 32% complete responses (11 patients), 24% partial responses (8), 12% stable disease (4), and 32% of patients who either had disease progression or had not yet had a postbaseline response assessment.

The median time to response was 1.8 months, with a median time to complete response of 3.4 months. Of 19 responders, 16 continue to have a response, including 10 of 11 patients with complete responses.

The most common grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Nonhematologic toxicities of any grade included rashes in 20% of patients, pyrexia in 16%, diarrhea in 16%, asthenia in 14%, and pneumonia, bronchitis, and nausea in 11% each.

There were no reported infusion-related reactions with the antibody. In all, 27% of patients required a lenalidomide dose reduction – to 20 mg/day in 20% of patients and to 15 mg/day in 7%.

Study accrual, follow-up of patients on therapy, investigations of cell origin, and subgroup analyses are ongoing.

MorphoSys is sponsoring the study. Dr. Salles has received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche/Genentech, and Servier and is an advisor/consultant to many of the same companies.

LUGANO, SWITZERLAND – Combining lenalidomide (Revlimid) with an anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody labeled MOR208 showed promising activity in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who were ineligible for stem cell transplant and had poor prognosis, early interim results from a clinical study indicate.

Among 34 patients evaluable for response, the preliminary objective response rate (ORR) was 56%, including complete responses in 32% of patients, reported Gilles Salles, MD, PhD, of the University of Lyon, France.

MOR208 is a humanized anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody with the Fc-antibody region enhanced to improve cytotoxicity. Its mechanisms of action include natural killer cell–mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, and direct cytotoxicity.

In a preclinical study, a combination of MOR208 and lenalidomide showed synergistic antileukemic and antilymphoma activity both in vivo and in vitro, Dr. Salles said.

In addition, both lenalidomide and MOR208 have shown significant activity against relapsed, refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

In an ongoing phase II, open-label study, Dr. Salles and his colleagues are enrolling transplant-ineligible patients 18 years and older with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status 0-2, and adequate organ function who had disease progression after 1-3 prior lines of therapy.

Patients with primary refractory DLBCL, double-hit or triple-hit DLBCL (i.e., mutations in Myc, BCL2, and/or BCL6), other NHL histological subtypes, or central nervous system lymphoma involvement are excluded.

Patients receive MOR208 12 mg/kg intravenously on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 for cycles 1-3 and on days 1 and 15 of cycles 4-12. Lenalidomide 25 mg orally is delivered on days 1-21 of each cycle. Patients who have stable disease or better at the end of 12 cycles can be maintained on MOR208 at the same dose on days 1 and 15.

As of the data cutoff on March 6, 2017, 44 patients had been enrolled, and 34 were evaluable for response. The median patient age was 73 years (range, 47-82 years).

At the time of the data presentation, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 56%, consisting of 32% complete responses (11 patients), 24% partial responses (8), 12% stable disease (4), and 32% of patients who either had disease progression or had not yet had a postbaseline response assessment.

The median time to response was 1.8 months, with a median time to complete response of 3.4 months. Of 19 responders, 16 continue to have a response, including 10 of 11 patients with complete responses.

The most common grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Nonhematologic toxicities of any grade included rashes in 20% of patients, pyrexia in 16%, diarrhea in 16%, asthenia in 14%, and pneumonia, bronchitis, and nausea in 11% each.

There were no reported infusion-related reactions with the antibody. In all, 27% of patients required a lenalidomide dose reduction – to 20 mg/day in 20% of patients and to 15 mg/day in 7%.

Study accrual, follow-up of patients on therapy, investigations of cell origin, and subgroup analyses are ongoing.

MorphoSys is sponsoring the study. Dr. Salles has received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche/Genentech, and Servier and is an advisor/consultant to many of the same companies.

AT 14-ICML

Key clinical point: A combination of the anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody MOR208 and the immunomodulator lenalidomide has shown good activity against relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Major finding: The preliminary objective response rate was 56%, including 32% complete responses.

Data source: An ongoing open-label phase II study with 44 patients out of a planned 80 enrolled.

Disclosures: MorphoSys is sponsoring the study. Dr. Salles has received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche/Genentech, and Servier and is an advisor or consultant to many of the same companies.

Biosimilar rituximab approved in Europe

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

CAR T cells plus ibrutinib induce CLL remissions

CHICAGO—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells combined with ibrutinib enhance T-cell function and can induce complete remission (CR) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), researchers report.

Many CLL patients receive ibrutinib treatment, which is well tolerated, but few patients achieve CR.

Immunotherapy with anti-CD19 CAR T cells has induced CR in 25% - 45% of patients with CLL, Saar Gill, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told Hematology Times, and these CRs tend to be durable.

So investigators conducted a pilot trial in 10 patients to test whether combining anti-CD19 CAR T cells with ibrutinib would enhance the CR rate.

Dr Gill reported the findings of the pilot trial at the ASCO 2017 Annual Meeting (abstract 7509).

The patients must have failed at least 1 regimen before ibrutinib, unless they had del(17)(p13.1) or a TP53 mutation.

T cells were lentivirally transduced to express a CAR that included humanized anti-CD19.

Patients were lymphodepleted 1 week before infusion, and ibrutinib was continued throughout the trial.

After a median follow-up of 6 months, 8 of the 9 evaluable patients show absence of CLL in the bone marrow by flow cytometry or minimal residual disease (MRD) negative, and all remain in marrow CR at last follow-up, Dr Gill said.

Radiologic responses are less clear-cut and may require longer follow-up.

“All but 1 patient achieved MRD with deep sequencing. We have deep response in the bone marrow,” Dr Gill said. He also noted that the treatment was well tolerated.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) developed in 9 patients: grade 1 in 2 patients, grade 2 in 6 patients, and grade 3 in 1 patient. One patient developed grade 4 tumor lysis syndrome. Treatment of CRS with the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab was not required.

There was modest residual splenomegaly in 3 of 5 patients, and adenopathy resolved in 4 of 6 patients, with progression in 1 patient.

Ibrutinib reduced CRS apparently by blocking cytokine production by T cells, said Dr Gill, adding, “The combination led to improved efficacy without increased toxicity.”

Ibrutinib may make CAR T-cell therapy more feasible.

Patients who receive ibrutinib for 6 months have a better T-cell response.

“This opens up future discussions of bringing CAR T-cell therapy earlier into CLL treatment,” said Dr Gill.

He envisions patients receiving ibrutinib for 6 months, which would allow time to manufacture T cells, and then have a T-cell infusion.

“Once patients achieve MRD, then we can discuss the possibility of stopping ibrutinib therapy,” he said.

“Most patients remain on ibrutinib, but longer follow-up may show whether remissions are sustained off ibrutinib.”

The researchers have ongoing plans to treat 25 patients with CTL19 plus ibrutinib in a continuation of this trial.

Dr Gill said longer follow-up will reveal the durability of these results “and could support evaluation of a first-line combination approach in an attempt to obviate the need for chronic therapy.” ![]()

CHICAGO—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells combined with ibrutinib enhance T-cell function and can induce complete remission (CR) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), researchers report.

Many CLL patients receive ibrutinib treatment, which is well tolerated, but few patients achieve CR.

Immunotherapy with anti-CD19 CAR T cells has induced CR in 25% - 45% of patients with CLL, Saar Gill, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told Hematology Times, and these CRs tend to be durable.

So investigators conducted a pilot trial in 10 patients to test whether combining anti-CD19 CAR T cells with ibrutinib would enhance the CR rate.

Dr Gill reported the findings of the pilot trial at the ASCO 2017 Annual Meeting (abstract 7509).

The patients must have failed at least 1 regimen before ibrutinib, unless they had del(17)(p13.1) or a TP53 mutation.

T cells were lentivirally transduced to express a CAR that included humanized anti-CD19.

Patients were lymphodepleted 1 week before infusion, and ibrutinib was continued throughout the trial.

After a median follow-up of 6 months, 8 of the 9 evaluable patients show absence of CLL in the bone marrow by flow cytometry or minimal residual disease (MRD) negative, and all remain in marrow CR at last follow-up, Dr Gill said.

Radiologic responses are less clear-cut and may require longer follow-up.

“All but 1 patient achieved MRD with deep sequencing. We have deep response in the bone marrow,” Dr Gill said. He also noted that the treatment was well tolerated.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) developed in 9 patients: grade 1 in 2 patients, grade 2 in 6 patients, and grade 3 in 1 patient. One patient developed grade 4 tumor lysis syndrome. Treatment of CRS with the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab was not required.

There was modest residual splenomegaly in 3 of 5 patients, and adenopathy resolved in 4 of 6 patients, with progression in 1 patient.

Ibrutinib reduced CRS apparently by blocking cytokine production by T cells, said Dr Gill, adding, “The combination led to improved efficacy without increased toxicity.”

Ibrutinib may make CAR T-cell therapy more feasible.

Patients who receive ibrutinib for 6 months have a better T-cell response.

“This opens up future discussions of bringing CAR T-cell therapy earlier into CLL treatment,” said Dr Gill.

He envisions patients receiving ibrutinib for 6 months, which would allow time to manufacture T cells, and then have a T-cell infusion.

“Once patients achieve MRD, then we can discuss the possibility of stopping ibrutinib therapy,” he said.

“Most patients remain on ibrutinib, but longer follow-up may show whether remissions are sustained off ibrutinib.”

The researchers have ongoing plans to treat 25 patients with CTL19 plus ibrutinib in a continuation of this trial.

Dr Gill said longer follow-up will reveal the durability of these results “and could support evaluation of a first-line combination approach in an attempt to obviate the need for chronic therapy.” ![]()

CHICAGO—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells combined with ibrutinib enhance T-cell function and can induce complete remission (CR) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), researchers report.

Many CLL patients receive ibrutinib treatment, which is well tolerated, but few patients achieve CR.

Immunotherapy with anti-CD19 CAR T cells has induced CR in 25% - 45% of patients with CLL, Saar Gill, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, told Hematology Times, and these CRs tend to be durable.

So investigators conducted a pilot trial in 10 patients to test whether combining anti-CD19 CAR T cells with ibrutinib would enhance the CR rate.

Dr Gill reported the findings of the pilot trial at the ASCO 2017 Annual Meeting (abstract 7509).

The patients must have failed at least 1 regimen before ibrutinib, unless they had del(17)(p13.1) or a TP53 mutation.

T cells were lentivirally transduced to express a CAR that included humanized anti-CD19.

Patients were lymphodepleted 1 week before infusion, and ibrutinib was continued throughout the trial.

After a median follow-up of 6 months, 8 of the 9 evaluable patients show absence of CLL in the bone marrow by flow cytometry or minimal residual disease (MRD) negative, and all remain in marrow CR at last follow-up, Dr Gill said.

Radiologic responses are less clear-cut and may require longer follow-up.

“All but 1 patient achieved MRD with deep sequencing. We have deep response in the bone marrow,” Dr Gill said. He also noted that the treatment was well tolerated.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) developed in 9 patients: grade 1 in 2 patients, grade 2 in 6 patients, and grade 3 in 1 patient. One patient developed grade 4 tumor lysis syndrome. Treatment of CRS with the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab was not required.

There was modest residual splenomegaly in 3 of 5 patients, and adenopathy resolved in 4 of 6 patients, with progression in 1 patient.

Ibrutinib reduced CRS apparently by blocking cytokine production by T cells, said Dr Gill, adding, “The combination led to improved efficacy without increased toxicity.”

Ibrutinib may make CAR T-cell therapy more feasible.

Patients who receive ibrutinib for 6 months have a better T-cell response.

“This opens up future discussions of bringing CAR T-cell therapy earlier into CLL treatment,” said Dr Gill.

He envisions patients receiving ibrutinib for 6 months, which would allow time to manufacture T cells, and then have a T-cell infusion.

“Once patients achieve MRD, then we can discuss the possibility of stopping ibrutinib therapy,” he said.

“Most patients remain on ibrutinib, but longer follow-up may show whether remissions are sustained off ibrutinib.”

The researchers have ongoing plans to treat 25 patients with CTL19 plus ibrutinib in a continuation of this trial.

Dr Gill said longer follow-up will reveal the durability of these results “and could support evaluation of a first-line combination approach in an attempt to obviate the need for chronic therapy.” ![]()

Two SNPs linked to survival in R-CHOP–treated DLBCL

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

Two variations of the BCL2 gene are linked with the survival prospects of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are treated with the R-CHOP regimen, based on a study published in Haematologica.

In the population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma across the British Columbia province, Morteza Bashash, PhD, of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, Toronto, and researchers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency analyzed 217 germline DLBCL samples, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, specifically looking at nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Patients receiving R-CHOP who had the AA genotype at rs7226979 had a risk of death that was four times higher than that of those with a G allele, researchers said (P less than .01). The same pattern was seen for PFS, with AA carriers having twice the risk of an event, compared with the other genotypes (P less than .05).

For those with rs4456611, patients with the GG genotype had a risk of death that was 3 times greater than that of those with an A allele (P less than .01), but there was no association with PFS for that SNP.

In an analysis of an independent cohort, only the associations that were seen with rs7226979 – and not those with rs4456611 – were able to be replicated.

The researchers noted that, while most predictive markers that are used to guide clinical treatment are drawn from actual tumor material, host-related factors could also be important.

“Compared to genetic analysis of the tumor, the patient’s constitutional genetic profile is relatively easy to obtain and can be assessed before treatment is started,” they wrote. “Our result has the potential to be useful as a complementary tool to predict the outcome of patients treated with R-CHOP and enhance clinical decision-making after confirmation by further studies.”

FROM HAEMATOLOGICA

Key clinical point: Two SNPs were found to be linked to survival prospects in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who receive primary R-CHOP therapy.

Major finding: For the rs7226979 SNP, those with the AA genotype had a four times higher risk of death than those with a G allele.

Data source: A population-based, case-control study of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in British Columbia, with DNA samples analyzed for 9nine SNPs among the DLBCL patients, excluding those with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma.

Disclosures: Some of the study authors reported institutional research funding from Roche; honoraria from Roche/Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; and/or consultant or advisory roles with Roche/Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, and NanoString Technologies.

Addition of ublituximab to ibrutinib improves response in r/r CLL

Ibrutinib, the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, has transformed the treatment landscape for patients with relapsed or refractory (r/r) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Yet for patients with high-risk molecular features, such as 11q deletion, 17p deletion, or TP53 mutation, relapse remains problematic.

Investigators evaluated whether the addition of ublituximab to ibrutinib would improve the outcome of patients with genetically high-risk CLL in the GENUINE (UTX-IB-301) phase 3 study.

Jeff P. Sharman, MD, of Willamette Valley Cancer Institute and Research Center in Springfield, Oregon, reported the results at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7504).*

Ublituximab is a glycoengineered, anti-CD20 type 1 monoclonal antibody that maintains complement-dependent cytotoxicity and enhances antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In a phase 2 study in combination with ibrutinib, it achieved an ORR of approximately 88%.

Protocol design

Originally, the study had co-primary endpoints of overall response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS). To adequately power for both endpoints, the target enrollment was 330 patients.

Dr Sharman explained that after 22 months of open enrollment, the trial sponsor determined that the original enrollment goal could not be met in a timely manner and elected to redesign the protocol.

In the modified protocol, ORR became the primary response rate and PFS a secondary endpoint. This allowed for a reduced target enrollment of 120. However, the study was no longer powered to detect a change in PFS.

Investigators stratified the patients by lines of prior therapy and then randomized them to receive ibrutinib or ublituximab plus ibrutinib.

The ibrutinib dose was 420 mg daily in both arms. Ublituximab dose was 900 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1, day 1 of cycles 2 through 6 and every third cycle thereafter.

The primary endpoint was ORR as assessed by Independent Central Review (IRC) using the iwCLL 2008 criteria.

Secondary endpoints included PFS, the complete response (CR) rate and depth of response (minimal residual disease [MRD] negativity), and safety.

The investigators assessed patients for response on weeks 8, 16, 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The primary endpoint was evaluated when all enrolled patients had at least 2 efficacy evaluations.

The median follow-up was 11.4 months.

Patient characteristics

Patients with relapsed or refractory high-risk CLL had their disease centrally confirmed for the presence of deletion 17p, deletion 11q, and/or TP53 mutation.

They had measurable disease, ECOG performance status of 2 or less, no history of transformation of CLL, and no prior BTK inhibitor therapy.

The investigators randomized 126 patients, and 117 received any dose of therapy.

“The dropout was because in part ibrutinib was via commercial supply and not every patient could get access,” Dr Sharman noted.

Fifty-nine patients were treated in the combination arm and 58 in the monotherapy arm.

All patients had at least one of the specified mutations, which were relatively balanced between the 2 arms.

Patients were a mean age of 67 (range, 43 – 87), had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 – 8), and more than 70% were male.

Patient characteristics were similar in each arm except for bulky disease, with 45% in the combination arm having bulky disease of 5 cm or more at baseline, compared with 26% in the monotherapy arm.

Twenty percent of the patients were considered refractory to rituximab.

Safety

Infusion reactions occurred in 54% of patients in the combination arm and 5% had grade 3/4 reactions. None occurred in the ibrutinib arm, since the latter is an orally bioavailable drug.

Other adverse events of all grades occurring in 10% of patients or more for the combination and monotherapy arms, respectively, were: diarrhea (42% and 40%), fatigue (27% and 33%), insomnia (24% and 10%), nausea (22% and 21%), headache (20% and 28%), arthralgia (19% and 17%), cough (19% and 24%), abdominal pain (15% and 9%), stomatitis (15% and 9%), upper respiratory infection (15% and 12%), dizziness (15% and 22%), contusion (15% and 29%), anemia (14% and 17%), and peripheral edema (10% and 21%).

Neutropenia was higher in the experimental arm, 22% any grade, compared with 12% in the ibrutinib arm, although grade 3 or higher neutropenia was similar in the 2 arms. Other laboratory abnormalities were similar between the arms.

Efficacy

The best ORR in the combination arm was 78%, with 7% achieving CR compared with 45% in the monotherapy arm with no CRs (P<0.001).

Nineteen percent of the combination arm achieved MRD negativity in peripheral blood compared with 2% of the monotherapy arm (P<0.01).

The reduction in lymph node size was similar between the arms.

In contrast, lymphocytosis was very different between the arms.

“As has been reported multiple times with targeted B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors,” Dr Sharman said, “patients treated with ibrutinib experienced rapid increase in their lymphocytes, returning approximately to baseline by 3 months and decreasing thereafter.”

“By contrast,” he continued, “those patients treated with the additional antibody had much more rapid resolution of their lymphocytosis. This was true whether patients were considered rituximab refractory or not.”

The investigators performed an additional analysis of ORR, this time including patients who achieved partial response with lymphocytosis (PR-L). These patients were not included in the primary endpoint because the iwCLL 2008 criteria had not yet been updated to include PR-L.

The best overall response including active PR-L patients was 83% in the experimental arm and 59% in the ibrutinib monotherapy arm (P<0.01).

PFS showed a trend toward improvement in the patients treated with the combination, with a hazard ratio of 0.559, which was not of statistical significance at the time of analysis.

The investigators concluded that the study met its primary endpoint, with a greater response rate and a greater depth of response than ibrutinib alone.

And the addition of ublituximab did not alter the safety profile of ibrutinib monotherapy.

TG Therapeutics, Inc, funded the study. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the meeting presentation.

Ibrutinib, the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, has transformed the treatment landscape for patients with relapsed or refractory (r/r) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Yet for patients with high-risk molecular features, such as 11q deletion, 17p deletion, or TP53 mutation, relapse remains problematic.

Investigators evaluated whether the addition of ublituximab to ibrutinib would improve the outcome of patients with genetically high-risk CLL in the GENUINE (UTX-IB-301) phase 3 study.

Jeff P. Sharman, MD, of Willamette Valley Cancer Institute and Research Center in Springfield, Oregon, reported the results at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7504).*

Ublituximab is a glycoengineered, anti-CD20 type 1 monoclonal antibody that maintains complement-dependent cytotoxicity and enhances antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In a phase 2 study in combination with ibrutinib, it achieved an ORR of approximately 88%.

Protocol design

Originally, the study had co-primary endpoints of overall response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS). To adequately power for both endpoints, the target enrollment was 330 patients.

Dr Sharman explained that after 22 months of open enrollment, the trial sponsor determined that the original enrollment goal could not be met in a timely manner and elected to redesign the protocol.

In the modified protocol, ORR became the primary response rate and PFS a secondary endpoint. This allowed for a reduced target enrollment of 120. However, the study was no longer powered to detect a change in PFS.

Investigators stratified the patients by lines of prior therapy and then randomized them to receive ibrutinib or ublituximab plus ibrutinib.

The ibrutinib dose was 420 mg daily in both arms. Ublituximab dose was 900 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1, day 1 of cycles 2 through 6 and every third cycle thereafter.

The primary endpoint was ORR as assessed by Independent Central Review (IRC) using the iwCLL 2008 criteria.

Secondary endpoints included PFS, the complete response (CR) rate and depth of response (minimal residual disease [MRD] negativity), and safety.

The investigators assessed patients for response on weeks 8, 16, 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The primary endpoint was evaluated when all enrolled patients had at least 2 efficacy evaluations.

The median follow-up was 11.4 months.

Patient characteristics

Patients with relapsed or refractory high-risk CLL had their disease centrally confirmed for the presence of deletion 17p, deletion 11q, and/or TP53 mutation.

They had measurable disease, ECOG performance status of 2 or less, no history of transformation of CLL, and no prior BTK inhibitor therapy.

The investigators randomized 126 patients, and 117 received any dose of therapy.

“The dropout was because in part ibrutinib was via commercial supply and not every patient could get access,” Dr Sharman noted.

Fifty-nine patients were treated in the combination arm and 58 in the monotherapy arm.

All patients had at least one of the specified mutations, which were relatively balanced between the 2 arms.

Patients were a mean age of 67 (range, 43 – 87), had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 – 8), and more than 70% were male.

Patient characteristics were similar in each arm except for bulky disease, with 45% in the combination arm having bulky disease of 5 cm or more at baseline, compared with 26% in the monotherapy arm.

Twenty percent of the patients were considered refractory to rituximab.

Safety

Infusion reactions occurred in 54% of patients in the combination arm and 5% had grade 3/4 reactions. None occurred in the ibrutinib arm, since the latter is an orally bioavailable drug.

Other adverse events of all grades occurring in 10% of patients or more for the combination and monotherapy arms, respectively, were: diarrhea (42% and 40%), fatigue (27% and 33%), insomnia (24% and 10%), nausea (22% and 21%), headache (20% and 28%), arthralgia (19% and 17%), cough (19% and 24%), abdominal pain (15% and 9%), stomatitis (15% and 9%), upper respiratory infection (15% and 12%), dizziness (15% and 22%), contusion (15% and 29%), anemia (14% and 17%), and peripheral edema (10% and 21%).

Neutropenia was higher in the experimental arm, 22% any grade, compared with 12% in the ibrutinib arm, although grade 3 or higher neutropenia was similar in the 2 arms. Other laboratory abnormalities were similar between the arms.

Efficacy

The best ORR in the combination arm was 78%, with 7% achieving CR compared with 45% in the monotherapy arm with no CRs (P<0.001).

Nineteen percent of the combination arm achieved MRD negativity in peripheral blood compared with 2% of the monotherapy arm (P<0.01).

The reduction in lymph node size was similar between the arms.

In contrast, lymphocytosis was very different between the arms.

“As has been reported multiple times with targeted B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors,” Dr Sharman said, “patients treated with ibrutinib experienced rapid increase in their lymphocytes, returning approximately to baseline by 3 months and decreasing thereafter.”

“By contrast,” he continued, “those patients treated with the additional antibody had much more rapid resolution of their lymphocytosis. This was true whether patients were considered rituximab refractory or not.”

The investigators performed an additional analysis of ORR, this time including patients who achieved partial response with lymphocytosis (PR-L). These patients were not included in the primary endpoint because the iwCLL 2008 criteria had not yet been updated to include PR-L.

The best overall response including active PR-L patients was 83% in the experimental arm and 59% in the ibrutinib monotherapy arm (P<0.01).

PFS showed a trend toward improvement in the patients treated with the combination, with a hazard ratio of 0.559, which was not of statistical significance at the time of analysis.

The investigators concluded that the study met its primary endpoint, with a greater response rate and a greater depth of response than ibrutinib alone.

And the addition of ublituximab did not alter the safety profile of ibrutinib monotherapy.

TG Therapeutics, Inc, funded the study. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the meeting presentation.

Ibrutinib, the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, has transformed the treatment landscape for patients with relapsed or refractory (r/r) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Yet for patients with high-risk molecular features, such as 11q deletion, 17p deletion, or TP53 mutation, relapse remains problematic.

Investigators evaluated whether the addition of ublituximab to ibrutinib would improve the outcome of patients with genetically high-risk CLL in the GENUINE (UTX-IB-301) phase 3 study.

Jeff P. Sharman, MD, of Willamette Valley Cancer Institute and Research Center in Springfield, Oregon, reported the results at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7504).*

Ublituximab is a glycoengineered, anti-CD20 type 1 monoclonal antibody that maintains complement-dependent cytotoxicity and enhances antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In a phase 2 study in combination with ibrutinib, it achieved an ORR of approximately 88%.

Protocol design

Originally, the study had co-primary endpoints of overall response rate (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS). To adequately power for both endpoints, the target enrollment was 330 patients.

Dr Sharman explained that after 22 months of open enrollment, the trial sponsor determined that the original enrollment goal could not be met in a timely manner and elected to redesign the protocol.

In the modified protocol, ORR became the primary response rate and PFS a secondary endpoint. This allowed for a reduced target enrollment of 120. However, the study was no longer powered to detect a change in PFS.

Investigators stratified the patients by lines of prior therapy and then randomized them to receive ibrutinib or ublituximab plus ibrutinib.

The ibrutinib dose was 420 mg daily in both arms. Ublituximab dose was 900 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1, day 1 of cycles 2 through 6 and every third cycle thereafter.

The primary endpoint was ORR as assessed by Independent Central Review (IRC) using the iwCLL 2008 criteria.

Secondary endpoints included PFS, the complete response (CR) rate and depth of response (minimal residual disease [MRD] negativity), and safety.

The investigators assessed patients for response on weeks 8, 16, 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

The primary endpoint was evaluated when all enrolled patients had at least 2 efficacy evaluations.

The median follow-up was 11.4 months.

Patient characteristics

Patients with relapsed or refractory high-risk CLL had their disease centrally confirmed for the presence of deletion 17p, deletion 11q, and/or TP53 mutation.

They had measurable disease, ECOG performance status of 2 or less, no history of transformation of CLL, and no prior BTK inhibitor therapy.

The investigators randomized 126 patients, and 117 received any dose of therapy.

“The dropout was because in part ibrutinib was via commercial supply and not every patient could get access,” Dr Sharman noted.

Fifty-nine patients were treated in the combination arm and 58 in the monotherapy arm.

All patients had at least one of the specified mutations, which were relatively balanced between the 2 arms.

Patients were a mean age of 67 (range, 43 – 87), had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 – 8), and more than 70% were male.

Patient characteristics were similar in each arm except for bulky disease, with 45% in the combination arm having bulky disease of 5 cm or more at baseline, compared with 26% in the monotherapy arm.

Twenty percent of the patients were considered refractory to rituximab.

Safety

Infusion reactions occurred in 54% of patients in the combination arm and 5% had grade 3/4 reactions. None occurred in the ibrutinib arm, since the latter is an orally bioavailable drug.

Other adverse events of all grades occurring in 10% of patients or more for the combination and monotherapy arms, respectively, were: diarrhea (42% and 40%), fatigue (27% and 33%), insomnia (24% and 10%), nausea (22% and 21%), headache (20% and 28%), arthralgia (19% and 17%), cough (19% and 24%), abdominal pain (15% and 9%), stomatitis (15% and 9%), upper respiratory infection (15% and 12%), dizziness (15% and 22%), contusion (15% and 29%), anemia (14% and 17%), and peripheral edema (10% and 21%).

Neutropenia was higher in the experimental arm, 22% any grade, compared with 12% in the ibrutinib arm, although grade 3 or higher neutropenia was similar in the 2 arms. Other laboratory abnormalities were similar between the arms.

Efficacy

The best ORR in the combination arm was 78%, with 7% achieving CR compared with 45% in the monotherapy arm with no CRs (P<0.001).

Nineteen percent of the combination arm achieved MRD negativity in peripheral blood compared with 2% of the monotherapy arm (P<0.01).

The reduction in lymph node size was similar between the arms.

In contrast, lymphocytosis was very different between the arms.

“As has been reported multiple times with targeted B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors,” Dr Sharman said, “patients treated with ibrutinib experienced rapid increase in their lymphocytes, returning approximately to baseline by 3 months and decreasing thereafter.”

“By contrast,” he continued, “those patients treated with the additional antibody had much more rapid resolution of their lymphocytosis. This was true whether patients were considered rituximab refractory or not.”