User login

Model recapitulates cancer susceptibility in DBA

Researchers say they’ve created the first animal model that recapitulates the predisposition to cancer observed in patients with Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA).

DBA is caused by mutations in ribosomal genes such as RPL11, so the researchers set out to determine the effects of manipulating RPL11 in mice.

The team found that RPL11-deficient mice

developed anemia, but they also had impaired p53 responses, elevated cMYC levels, and increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Manuel Serrano, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell Reports.

Previous observational studies suggested that around 20% of patients with DBA develop cancers, particularly lymphomas. Other research groups have developed animal models that recapitulate certain characteristics of DBA but not the predisposition to cancer.

In an attempt to change that, Dr Serrano and his colleagues focused their work on RPL11.

“Cells need the ribosomes to function properly in order to proliferate and grow,” Dr Serrano explained. “We knew that when something goes wrong in these organelles, RPL11 operates as a switch that activates the p53 gene to stop the cells from proliferating and forming tumors. This mechanism is called ribosomal stress.”

“P53 is one of the main tumor suppressor genes identified to date, to the extent that its relevance in preventing cancer has led to it being named the ‘guardian of the genome.’ This important function made us think that the protein could play a crucial role in the cancer predisposition observed in patients with DBA. If RPL11 is mutated, it loses the ability to activate p53 to prevent tumors caused by cellular damage.”

In fact, the researchers found that total or partial deletion of RPL11 impairs the normal function of p53 and increases levels of cMYC, which can promote tumor development.

“We believe that, in DBA, both factors combined contribute to induce the development of cancer,” said Lucía Morgado-Palacín, also of CNIO.

The researchers’ experiments supported this idea, as mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion exhibited increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion also developed anemia that was associated with decreased erythroid

progenitors and defective erythroid maturation.

Homozygous deletion of RPL11, on the other hand, led to bone marrow aplasia

and intestinal atrophy in adult mice. And these mice died within a few weeks. ![]()

Researchers say they’ve created the first animal model that recapitulates the predisposition to cancer observed in patients with Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA).

DBA is caused by mutations in ribosomal genes such as RPL11, so the researchers set out to determine the effects of manipulating RPL11 in mice.

The team found that RPL11-deficient mice

developed anemia, but they also had impaired p53 responses, elevated cMYC levels, and increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Manuel Serrano, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell Reports.

Previous observational studies suggested that around 20% of patients with DBA develop cancers, particularly lymphomas. Other research groups have developed animal models that recapitulate certain characteristics of DBA but not the predisposition to cancer.

In an attempt to change that, Dr Serrano and his colleagues focused their work on RPL11.

“Cells need the ribosomes to function properly in order to proliferate and grow,” Dr Serrano explained. “We knew that when something goes wrong in these organelles, RPL11 operates as a switch that activates the p53 gene to stop the cells from proliferating and forming tumors. This mechanism is called ribosomal stress.”

“P53 is one of the main tumor suppressor genes identified to date, to the extent that its relevance in preventing cancer has led to it being named the ‘guardian of the genome.’ This important function made us think that the protein could play a crucial role in the cancer predisposition observed in patients with DBA. If RPL11 is mutated, it loses the ability to activate p53 to prevent tumors caused by cellular damage.”

In fact, the researchers found that total or partial deletion of RPL11 impairs the normal function of p53 and increases levels of cMYC, which can promote tumor development.

“We believe that, in DBA, both factors combined contribute to induce the development of cancer,” said Lucía Morgado-Palacín, also of CNIO.

The researchers’ experiments supported this idea, as mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion exhibited increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion also developed anemia that was associated with decreased erythroid

progenitors and defective erythroid maturation.

Homozygous deletion of RPL11, on the other hand, led to bone marrow aplasia

and intestinal atrophy in adult mice. And these mice died within a few weeks. ![]()

Researchers say they’ve created the first animal model that recapitulates the predisposition to cancer observed in patients with Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA).

DBA is caused by mutations in ribosomal genes such as RPL11, so the researchers set out to determine the effects of manipulating RPL11 in mice.

The team found that RPL11-deficient mice

developed anemia, but they also had impaired p53 responses, elevated cMYC levels, and increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Manuel Serrano, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell Reports.

Previous observational studies suggested that around 20% of patients with DBA develop cancers, particularly lymphomas. Other research groups have developed animal models that recapitulate certain characteristics of DBA but not the predisposition to cancer.

In an attempt to change that, Dr Serrano and his colleagues focused their work on RPL11.

“Cells need the ribosomes to function properly in order to proliferate and grow,” Dr Serrano explained. “We knew that when something goes wrong in these organelles, RPL11 operates as a switch that activates the p53 gene to stop the cells from proliferating and forming tumors. This mechanism is called ribosomal stress.”

“P53 is one of the main tumor suppressor genes identified to date, to the extent that its relevance in preventing cancer has led to it being named the ‘guardian of the genome.’ This important function made us think that the protein could play a crucial role in the cancer predisposition observed in patients with DBA. If RPL11 is mutated, it loses the ability to activate p53 to prevent tumors caused by cellular damage.”

In fact, the researchers found that total or partial deletion of RPL11 impairs the normal function of p53 and increases levels of cMYC, which can promote tumor development.

“We believe that, in DBA, both factors combined contribute to induce the development of cancer,” said Lucía Morgado-Palacín, also of CNIO.

The researchers’ experiments supported this idea, as mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion exhibited increased susceptibility to radiation-induced lymphomagenesis.

Mice with heterozygous RPL11 deletion also developed anemia that was associated with decreased erythroid

progenitors and defective erythroid maturation.

Homozygous deletion of RPL11, on the other hand, led to bone marrow aplasia

and intestinal atrophy in adult mice. And these mice died within a few weeks. ![]()

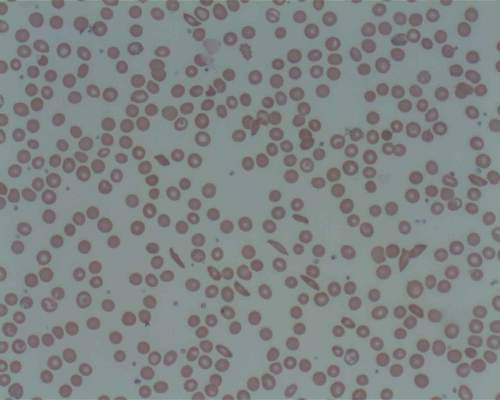

Antibiotics to reduce microbiota may improve treatment of sickle-cell disease

The human body’s microbiota regulates the aging of circulating neutrophils, and aged neutrophils, which are excessively active and adherent, promote tissue injury in inflammatory diseases. These two discoveries appear to point the way toward a simple, effective antibiotic treatment for sickle-cell disease, and may eventually lead to similar therapies for other disorders that induce inflammation-related organ damage, such as septic shock, according to a Research Letter published online Sept. 16 in Nature.

“To our knowledge, this is the first therapy shown to alleviate the chronic tissue damage induced by sickle-cell disease,” said Dachuan Zhang of the Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Research and the department of cell biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and his associates. “Our results raise the possibility that manipulation of the microbiome may have sustained implications in disease outcome that should be further studied in clinical trials.”

In a series of in vitro and in vivo studies, the researchers demonstrated that aging neutrophils differ from others in that they are overactive and extra-adherent. Adherent neutrophils are already known to precipitate the acute vaso-occlusion that characterizes sickle-cell disease. Aging neutrophils also displayed other traits suggesting that exogenous inflammatory mediators may contribute to their excessive activity and adherence.

Dr. Zhang and his colleagues suspected that molecules in the microbiota – the ecologic community of all microorganisms residing in the body – may be involved, as they are known to cross the intestinal barrier to affect multiple systemic immune-cell populations, and a recent study suggested that the microbiota may regulate neutrophil production and function. To test this hypothesis they treated mice with broad-spectrum antibiotics, which caused dramatic depletion of microbiota volume and composition in the gut. This in turn significantly reduced aged neutrophils in the circulation, which immediately rebounded when the antibiotics were counteracted.

Further mouse studies revealed that neutrophil aging is delayed in a bacterially depleted environment, and that microbiota-derived molecules actually induce neutrophil aging. In a subsequent study of an in vivo model of septic shock, mice that were given antibiotics were protected from neutrophil-mediated damage in the vasculature and showed markedly prolonged survival, compared with untreated mice, the investigators noted (Nature. 2015 Sep 24;525[7570]. doi: 10.1038/nature15367 ).

In an in vivo model of sickle-cell disease, untreated mice with the disease showed markedly increased neutrophil activity and adhesion while affected mice given antibiotics showed marked microbiota depletion; enhanced blood flow; significantly reduced splenomegaly; and marked alleviation of liver necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Survival was significantly improved in the treated mice. Finally, a laboratory-induced replenishment of aging neutrophils in the circulation resulted in acute vaso-occlusive crises and death within 10-30 hours in all affected mice.

“Together, these data suggest that the microbiota regulates aged neutrophil numbers, thereby affecting both acute vaso-occlusive crisis and the ensuing chronic tissue damage in sickle-cell disease,” Dr. Zhang and his associates said.

To assess how their findings applied to human beings, the investigators next studied 23 patients with sickle-cell disease who were not taking antibiotics, 11 patients with sickle-cell disease who were taking penicillin to prevent life-threatening infections, and 9 healthy control subjects. Compared with controls, only the patients who weren’t taking antibiotics showed a dramatic increase in circulating aged neutrophils. This protective effect of antibiotics was consistent across all ages, both genders, and regardless of hydroxyurea intake. Now, a prospective study involving age-matched participants is needed to confirm that antibiotics, by reducing the gut microbiota, decrease aged neutrophils in the circulation and thereby improve vaso-occlusive disease, the researchers said.

The American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the New York State Stem Cell Science Program funded the study. Dr. Zhang and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

The human body’s microbiota regulates the aging of circulating neutrophils, and aged neutrophils, which are excessively active and adherent, promote tissue injury in inflammatory diseases. These two discoveries appear to point the way toward a simple, effective antibiotic treatment for sickle-cell disease, and may eventually lead to similar therapies for other disorders that induce inflammation-related organ damage, such as septic shock, according to a Research Letter published online Sept. 16 in Nature.

“To our knowledge, this is the first therapy shown to alleviate the chronic tissue damage induced by sickle-cell disease,” said Dachuan Zhang of the Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Research and the department of cell biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and his associates. “Our results raise the possibility that manipulation of the microbiome may have sustained implications in disease outcome that should be further studied in clinical trials.”

In a series of in vitro and in vivo studies, the researchers demonstrated that aging neutrophils differ from others in that they are overactive and extra-adherent. Adherent neutrophils are already known to precipitate the acute vaso-occlusion that characterizes sickle-cell disease. Aging neutrophils also displayed other traits suggesting that exogenous inflammatory mediators may contribute to their excessive activity and adherence.

Dr. Zhang and his colleagues suspected that molecules in the microbiota – the ecologic community of all microorganisms residing in the body – may be involved, as they are known to cross the intestinal barrier to affect multiple systemic immune-cell populations, and a recent study suggested that the microbiota may regulate neutrophil production and function. To test this hypothesis they treated mice with broad-spectrum antibiotics, which caused dramatic depletion of microbiota volume and composition in the gut. This in turn significantly reduced aged neutrophils in the circulation, which immediately rebounded when the antibiotics were counteracted.

Further mouse studies revealed that neutrophil aging is delayed in a bacterially depleted environment, and that microbiota-derived molecules actually induce neutrophil aging. In a subsequent study of an in vivo model of septic shock, mice that were given antibiotics were protected from neutrophil-mediated damage in the vasculature and showed markedly prolonged survival, compared with untreated mice, the investigators noted (Nature. 2015 Sep 24;525[7570]. doi: 10.1038/nature15367 ).

In an in vivo model of sickle-cell disease, untreated mice with the disease showed markedly increased neutrophil activity and adhesion while affected mice given antibiotics showed marked microbiota depletion; enhanced blood flow; significantly reduced splenomegaly; and marked alleviation of liver necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Survival was significantly improved in the treated mice. Finally, a laboratory-induced replenishment of aging neutrophils in the circulation resulted in acute vaso-occlusive crises and death within 10-30 hours in all affected mice.

“Together, these data suggest that the microbiota regulates aged neutrophil numbers, thereby affecting both acute vaso-occlusive crisis and the ensuing chronic tissue damage in sickle-cell disease,” Dr. Zhang and his associates said.

To assess how their findings applied to human beings, the investigators next studied 23 patients with sickle-cell disease who were not taking antibiotics, 11 patients with sickle-cell disease who were taking penicillin to prevent life-threatening infections, and 9 healthy control subjects. Compared with controls, only the patients who weren’t taking antibiotics showed a dramatic increase in circulating aged neutrophils. This protective effect of antibiotics was consistent across all ages, both genders, and regardless of hydroxyurea intake. Now, a prospective study involving age-matched participants is needed to confirm that antibiotics, by reducing the gut microbiota, decrease aged neutrophils in the circulation and thereby improve vaso-occlusive disease, the researchers said.

The American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the New York State Stem Cell Science Program funded the study. Dr. Zhang and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

The human body’s microbiota regulates the aging of circulating neutrophils, and aged neutrophils, which are excessively active and adherent, promote tissue injury in inflammatory diseases. These two discoveries appear to point the way toward a simple, effective antibiotic treatment for sickle-cell disease, and may eventually lead to similar therapies for other disorders that induce inflammation-related organ damage, such as septic shock, according to a Research Letter published online Sept. 16 in Nature.

“To our knowledge, this is the first therapy shown to alleviate the chronic tissue damage induced by sickle-cell disease,” said Dachuan Zhang of the Gottesman Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Research and the department of cell biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and his associates. “Our results raise the possibility that manipulation of the microbiome may have sustained implications in disease outcome that should be further studied in clinical trials.”

In a series of in vitro and in vivo studies, the researchers demonstrated that aging neutrophils differ from others in that they are overactive and extra-adherent. Adherent neutrophils are already known to precipitate the acute vaso-occlusion that characterizes sickle-cell disease. Aging neutrophils also displayed other traits suggesting that exogenous inflammatory mediators may contribute to their excessive activity and adherence.

Dr. Zhang and his colleagues suspected that molecules in the microbiota – the ecologic community of all microorganisms residing in the body – may be involved, as they are known to cross the intestinal barrier to affect multiple systemic immune-cell populations, and a recent study suggested that the microbiota may regulate neutrophil production and function. To test this hypothesis they treated mice with broad-spectrum antibiotics, which caused dramatic depletion of microbiota volume and composition in the gut. This in turn significantly reduced aged neutrophils in the circulation, which immediately rebounded when the antibiotics were counteracted.

Further mouse studies revealed that neutrophil aging is delayed in a bacterially depleted environment, and that microbiota-derived molecules actually induce neutrophil aging. In a subsequent study of an in vivo model of septic shock, mice that were given antibiotics were protected from neutrophil-mediated damage in the vasculature and showed markedly prolonged survival, compared with untreated mice, the investigators noted (Nature. 2015 Sep 24;525[7570]. doi: 10.1038/nature15367 ).

In an in vivo model of sickle-cell disease, untreated mice with the disease showed markedly increased neutrophil activity and adhesion while affected mice given antibiotics showed marked microbiota depletion; enhanced blood flow; significantly reduced splenomegaly; and marked alleviation of liver necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Survival was significantly improved in the treated mice. Finally, a laboratory-induced replenishment of aging neutrophils in the circulation resulted in acute vaso-occlusive crises and death within 10-30 hours in all affected mice.

“Together, these data suggest that the microbiota regulates aged neutrophil numbers, thereby affecting both acute vaso-occlusive crisis and the ensuing chronic tissue damage in sickle-cell disease,” Dr. Zhang and his associates said.

To assess how their findings applied to human beings, the investigators next studied 23 patients with sickle-cell disease who were not taking antibiotics, 11 patients with sickle-cell disease who were taking penicillin to prevent life-threatening infections, and 9 healthy control subjects. Compared with controls, only the patients who weren’t taking antibiotics showed a dramatic increase in circulating aged neutrophils. This protective effect of antibiotics was consistent across all ages, both genders, and regardless of hydroxyurea intake. Now, a prospective study involving age-matched participants is needed to confirm that antibiotics, by reducing the gut microbiota, decrease aged neutrophils in the circulation and thereby improve vaso-occlusive disease, the researchers said.

The American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the New York State Stem Cell Science Program funded the study. Dr. Zhang and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

FROM NATURE

Key clinical point: The body’s microbiota was found to regulate the aging of circulating neutrophils, a discovery that points the way to easily and markedly improve the chronic tissue damage induced by sickle-cell and perhaps other diseases.

Major finding: In an in vivo mouse model of sickle-cell disease, mice given antibiotics showed marked microbiota depletion; enhanced blood flow; significantly reduced splenomegaly; marked alleviation of liver necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation; and significantly improved survival.

Data source: A series of in vitro, in vivo, and human studies, the latter involving 23 patients with SCD, 11 with SCD taking prophylactic antibiotics, and 9 healthy control subjects.

Disclosures: The American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health, and the New York State Stem Cell Science Program funded the study. Dr. Zhang and his associates reported having no relevant disclosures.

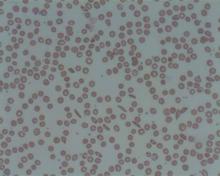

Explaining treatment-related anemia

Research conducted in mice suggests that genomic screening might reveal cancer patients who are likely to develop treatment-related anemia.

The study showed that mice lacking Pten and Shp2—enzymes targeted by certain anticancer therapies—can’t produce and sustain enough red blood cells.

Investigators said this helps explain why anemia is a common side effect of anticancer drugs that target enzymes involved in tumor growth.

“Based on this unexpected finding, we might want to think about screening cancer patients’ genetic backgrounds for loss of Pten or Pten-regulated signals before prescribing anticancer drugs that might do more harm than good,” said Gen-Sheng Feng, PhD, of the University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

Dr Feng and his colleagues described their research in PNAS.

First, the team genetically engineered mice to lack Pten, Shp2, or both enzymes. The Pten-deficient mice had elevated white blood cells counts, consistent with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The Shp2-deficient mice experienced the opposite—lower white blood cell counts. And mice lacking both Pten and Shp2 had relatively normal white blood cell counts, suggesting that loss of Shp2 suppresses MPNs induced by Pten loss.

However, the investigators also discovered that mice lacking both enzymes had shorter lifespans than wild-type mice or mice lacking 1 of the enzymes.

This was because the combined deficiency of Shp2 and Pten induced lethal anemia. And this anemia was a result of 2 factors: red blood cells failed to develop properly and those that did form had a shortened lifespan.

To build upon these findings, the investigators treated Pten-deficient mice with the Shp2 inhibitor 11a-1 or with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. (MEK belongs to the same cellular communication network as Shp2.)

As with genetic deletion of Shp2, pharmacologic inhibition of Shp2 suppressed MPN induced by Pten loss and induced severe anemia in the mice.

Trametinib treatment had a similar effect, inducing anemia in Pten-deficient mice but not wild-type mice.

“What we’ve learned is that even if we know a lot about how individual molecules function in a cell, designing effective therapeutics that target them will require a more comprehensive understanding of the cross-talk between molecules in a particular cell type and in the context of disease,” Dr Feng concluded. ![]()

Research conducted in mice suggests that genomic screening might reveal cancer patients who are likely to develop treatment-related anemia.

The study showed that mice lacking Pten and Shp2—enzymes targeted by certain anticancer therapies—can’t produce and sustain enough red blood cells.

Investigators said this helps explain why anemia is a common side effect of anticancer drugs that target enzymes involved in tumor growth.

“Based on this unexpected finding, we might want to think about screening cancer patients’ genetic backgrounds for loss of Pten or Pten-regulated signals before prescribing anticancer drugs that might do more harm than good,” said Gen-Sheng Feng, PhD, of the University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

Dr Feng and his colleagues described their research in PNAS.

First, the team genetically engineered mice to lack Pten, Shp2, or both enzymes. The Pten-deficient mice had elevated white blood cells counts, consistent with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The Shp2-deficient mice experienced the opposite—lower white blood cell counts. And mice lacking both Pten and Shp2 had relatively normal white blood cell counts, suggesting that loss of Shp2 suppresses MPNs induced by Pten loss.

However, the investigators also discovered that mice lacking both enzymes had shorter lifespans than wild-type mice or mice lacking 1 of the enzymes.

This was because the combined deficiency of Shp2 and Pten induced lethal anemia. And this anemia was a result of 2 factors: red blood cells failed to develop properly and those that did form had a shortened lifespan.

To build upon these findings, the investigators treated Pten-deficient mice with the Shp2 inhibitor 11a-1 or with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. (MEK belongs to the same cellular communication network as Shp2.)

As with genetic deletion of Shp2, pharmacologic inhibition of Shp2 suppressed MPN induced by Pten loss and induced severe anemia in the mice.

Trametinib treatment had a similar effect, inducing anemia in Pten-deficient mice but not wild-type mice.

“What we’ve learned is that even if we know a lot about how individual molecules function in a cell, designing effective therapeutics that target them will require a more comprehensive understanding of the cross-talk between molecules in a particular cell type and in the context of disease,” Dr Feng concluded. ![]()

Research conducted in mice suggests that genomic screening might reveal cancer patients who are likely to develop treatment-related anemia.

The study showed that mice lacking Pten and Shp2—enzymes targeted by certain anticancer therapies—can’t produce and sustain enough red blood cells.

Investigators said this helps explain why anemia is a common side effect of anticancer drugs that target enzymes involved in tumor growth.

“Based on this unexpected finding, we might want to think about screening cancer patients’ genetic backgrounds for loss of Pten or Pten-regulated signals before prescribing anticancer drugs that might do more harm than good,” said Gen-Sheng Feng, PhD, of the University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

Dr Feng and his colleagues described their research in PNAS.

First, the team genetically engineered mice to lack Pten, Shp2, or both enzymes. The Pten-deficient mice had elevated white blood cells counts, consistent with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The Shp2-deficient mice experienced the opposite—lower white blood cell counts. And mice lacking both Pten and Shp2 had relatively normal white blood cell counts, suggesting that loss of Shp2 suppresses MPNs induced by Pten loss.

However, the investigators also discovered that mice lacking both enzymes had shorter lifespans than wild-type mice or mice lacking 1 of the enzymes.

This was because the combined deficiency of Shp2 and Pten induced lethal anemia. And this anemia was a result of 2 factors: red blood cells failed to develop properly and those that did form had a shortened lifespan.

To build upon these findings, the investigators treated Pten-deficient mice with the Shp2 inhibitor 11a-1 or with the MEK inhibitor trametinib. (MEK belongs to the same cellular communication network as Shp2.)

As with genetic deletion of Shp2, pharmacologic inhibition of Shp2 suppressed MPN induced by Pten loss and induced severe anemia in the mice.

Trametinib treatment had a similar effect, inducing anemia in Pten-deficient mice but not wild-type mice.

“What we’ve learned is that even if we know a lot about how individual molecules function in a cell, designing effective therapeutics that target them will require a more comprehensive understanding of the cross-talk between molecules in a particular cell type and in the context of disease,” Dr Feng concluded. ![]()

Eltrombopag can benefit kids with chronic ITP

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of 2 studies suggest eltrombopag can be safe and effective in children of all ages affected by chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

In both trials, patients who received eltrombopag were significantly more likely to achieve stable platelet counts than patients who received placebo.

And eltrombopag did not increase the rate of serious adverse events (AEs).

These studies are the phase 2 PETIT trial, which was published in The Lancet Haematology, and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial, which was published in The Lancet.

“The studies, funded by GlaxoSmithKline, provide clinicians with much-needed evidence to help decide when eltrombopag would benefit pediatric patients and provide dosage regimens suitable for pediatric patients,” said investigator John Grainger, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK.

Phase 2 trial

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients who were stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years) and randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The most common AEs (in the eltrombopag and placebo groups, respectively) were headache (30% vs 43%), upper respiratory tract infection (25% vs 10%), and diarrhea (16% vs 5%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 11% of patients receiving eltrombopag and 19% of patients receiving placebo. Serious AEs occurred in 9% and 10%, respectively. There were no thrombotic events or malignancies in either group.

Phase 3 trial

The PETIT2 trial included 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%, compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

AEs that occurred more frequently with eltrombopag than with placebo included nasopharyngitis (17%), rhinitis (16%), upper respiratory tract infection (11%), and cough (11%).

Serious AEs occurred in 8% of patients who received eltrombopag and 14% who received placebo. There were no deaths, malignancies, or thromboses during this trial.

It was based on these studies that eltrombopag was approved for use in US children older than 1 year of age. The drug is currently under review for this indication in the European Union. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of 2 studies suggest eltrombopag can be safe and effective in children of all ages affected by chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

In both trials, patients who received eltrombopag were significantly more likely to achieve stable platelet counts than patients who received placebo.

And eltrombopag did not increase the rate of serious adverse events (AEs).

These studies are the phase 2 PETIT trial, which was published in The Lancet Haematology, and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial, which was published in The Lancet.

“The studies, funded by GlaxoSmithKline, provide clinicians with much-needed evidence to help decide when eltrombopag would benefit pediatric patients and provide dosage regimens suitable for pediatric patients,” said investigator John Grainger, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK.

Phase 2 trial

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients who were stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years) and randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The most common AEs (in the eltrombopag and placebo groups, respectively) were headache (30% vs 43%), upper respiratory tract infection (25% vs 10%), and diarrhea (16% vs 5%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 11% of patients receiving eltrombopag and 19% of patients receiving placebo. Serious AEs occurred in 9% and 10%, respectively. There were no thrombotic events or malignancies in either group.

Phase 3 trial

The PETIT2 trial included 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%, compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

AEs that occurred more frequently with eltrombopag than with placebo included nasopharyngitis (17%), rhinitis (16%), upper respiratory tract infection (11%), and cough (11%).

Serious AEs occurred in 8% of patients who received eltrombopag and 14% who received placebo. There were no deaths, malignancies, or thromboses during this trial.

It was based on these studies that eltrombopag was approved for use in US children older than 1 year of age. The drug is currently under review for this indication in the European Union. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Results of 2 studies suggest eltrombopag can be safe and effective in children of all ages affected by chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

In both trials, patients who received eltrombopag were significantly more likely to achieve stable platelet counts than patients who received placebo.

And eltrombopag did not increase the rate of serious adverse events (AEs).

These studies are the phase 2 PETIT trial, which was published in The Lancet Haematology, and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial, which was published in The Lancet.

“The studies, funded by GlaxoSmithKline, provide clinicians with much-needed evidence to help decide when eltrombopag would benefit pediatric patients and provide dosage regimens suitable for pediatric patients,” said investigator John Grainger, PhD, of The University of Manchester in the UK.

Phase 2 trial

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients who were stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years) and randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The most common AEs (in the eltrombopag and placebo groups, respectively) were headache (30% vs 43%), upper respiratory tract infection (25% vs 10%), and diarrhea (16% vs 5%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 11% of patients receiving eltrombopag and 19% of patients receiving placebo. Serious AEs occurred in 9% and 10%, respectively. There were no thrombotic events or malignancies in either group.

Phase 3 trial

The PETIT2 trial included 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%, compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

AEs that occurred more frequently with eltrombopag than with placebo included nasopharyngitis (17%), rhinitis (16%), upper respiratory tract infection (11%), and cough (11%).

Serious AEs occurred in 8% of patients who received eltrombopag and 14% who received placebo. There were no deaths, malignancies, or thromboses during this trial.

It was based on these studies that eltrombopag was approved for use in US children older than 1 year of age. The drug is currently under review for this indication in the European Union. ![]()

Haplo-HSCT appears comparable to fully matched HSCT

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A retrospective study suggests that, for patients with hematologic disorders, a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)

can be roughly as safe and effective as a fully matched HSCT.

The study showed that, when patients received an identical conditioning regimen, graft T-cell dose, and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, haploidentical and fully matched HSCTs produced comparable results.

Patients had similar rates of overall and progression-free survival, relapse, non-relapse mortality, and chronic GVHD.

However, patients who received haploidentical transplants had higher rates of grade 2-4 acute GVHD and cytomegalovirus reactivation.

Researchers reported these results in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“This is the first study to compare the gold standard to a half-match using an identical protocol,” said Neal Flomenberg, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“The field has debated whether the differences in outcomes between full and partial matches were caused by the quality of the match or by all the procedures the patient goes through before and after the donor cells are administered. We haven’t had a clear answer.”

With that in mind, Dr Flomenberg and his colleagues compared 3-year outcome data from patients who received haploidentical HSCTs (n=50) or fully matched HSCTs (n=27), when both groups of patients were treated with a 2-step protocol.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (n=38), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=20), myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=11), and aplastic anemia (n=1).

The 2-step protocol

All patients received a myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of 12 Gy of total body irradiation administered in 8 fractions over 4 days. After the last fraction, they received a fixed T-cell dose (2 x 108 cells/kg), which was followed, 2 days later, by cyclophosphamide at 60 mg/kg/day for 2 days.

Twenty-four hours after they completed cyclophosphamide, patients received CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cells from a half-matched or fully matched donor.

On day -1, patients began taking tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as GVHD prophylaxis. They also received growth factor support (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor at 250 μg/m2) starting on day +1.

In the absence of GVHD, mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued on day 28 and tacrolimus was tapered, starting on day +60 after HSCT.

Results

The researchers said that early immune recovery was comparable between the patient groups in nearly all assessed T-cell subsets. The exception was the median CD3/CD8 cell count, which was significantly higher at day 28 in the fully matched group than the haploidentical group (P=0.029).

Survival rates were comparable between the groups. The estimated 3-year overall survival was 70% in the haploidentical group and 71% in the fully matched group (P=0.81). The 3-year progression-free survival was 68% and 70%, respectively (P=0.97).

The 3-year cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality was 10% in the haploidentical group and 4% in the fully matched group (P=0.34). The 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 21% and 27%, respectively (P=0.93).

The 100-day cumulative incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—40% and 8%, respectively (P<0.001). But there was no significant difference in the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD—6% and 4%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2 years was not significantly different between the haploidentical and fully matched groups—19% and 12%, respectively (P=0.47). The same was true for severe chronic GVHD—4% and 8%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—68% and 19%, respectively (P<0.001).

There were no deaths from infections or GVHD in either group.

“The results of the current study are certainly encouraging and suggest that outcomes from a half-matched, related donor are similar to fully matched donors,” said study author Sameh Gaballa, MD, also of Thomas Jefferson University.

“It might be time to reassess whether half-matched, related transplants can be considered the best alternative donor source for patients lacking a fully matched family member donor. For that, we’ll need more evidence from a randomly controlled, prospective trial, rather than studies that look at patient data retrospectively, to help solidify our findings here.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A retrospective study suggests that, for patients with hematologic disorders, a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)

can be roughly as safe and effective as a fully matched HSCT.

The study showed that, when patients received an identical conditioning regimen, graft T-cell dose, and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, haploidentical and fully matched HSCTs produced comparable results.

Patients had similar rates of overall and progression-free survival, relapse, non-relapse mortality, and chronic GVHD.

However, patients who received haploidentical transplants had higher rates of grade 2-4 acute GVHD and cytomegalovirus reactivation.

Researchers reported these results in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“This is the first study to compare the gold standard to a half-match using an identical protocol,” said Neal Flomenberg, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“The field has debated whether the differences in outcomes between full and partial matches were caused by the quality of the match or by all the procedures the patient goes through before and after the donor cells are administered. We haven’t had a clear answer.”

With that in mind, Dr Flomenberg and his colleagues compared 3-year outcome data from patients who received haploidentical HSCTs (n=50) or fully matched HSCTs (n=27), when both groups of patients were treated with a 2-step protocol.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (n=38), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=20), myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=11), and aplastic anemia (n=1).

The 2-step protocol

All patients received a myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of 12 Gy of total body irradiation administered in 8 fractions over 4 days. After the last fraction, they received a fixed T-cell dose (2 x 108 cells/kg), which was followed, 2 days later, by cyclophosphamide at 60 mg/kg/day for 2 days.

Twenty-four hours after they completed cyclophosphamide, patients received CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cells from a half-matched or fully matched donor.

On day -1, patients began taking tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as GVHD prophylaxis. They also received growth factor support (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor at 250 μg/m2) starting on day +1.

In the absence of GVHD, mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued on day 28 and tacrolimus was tapered, starting on day +60 after HSCT.

Results

The researchers said that early immune recovery was comparable between the patient groups in nearly all assessed T-cell subsets. The exception was the median CD3/CD8 cell count, which was significantly higher at day 28 in the fully matched group than the haploidentical group (P=0.029).

Survival rates were comparable between the groups. The estimated 3-year overall survival was 70% in the haploidentical group and 71% in the fully matched group (P=0.81). The 3-year progression-free survival was 68% and 70%, respectively (P=0.97).

The 3-year cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality was 10% in the haploidentical group and 4% in the fully matched group (P=0.34). The 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 21% and 27%, respectively (P=0.93).

The 100-day cumulative incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—40% and 8%, respectively (P<0.001). But there was no significant difference in the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD—6% and 4%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2 years was not significantly different between the haploidentical and fully matched groups—19% and 12%, respectively (P=0.47). The same was true for severe chronic GVHD—4% and 8%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—68% and 19%, respectively (P<0.001).

There were no deaths from infections or GVHD in either group.

“The results of the current study are certainly encouraging and suggest that outcomes from a half-matched, related donor are similar to fully matched donors,” said study author Sameh Gaballa, MD, also of Thomas Jefferson University.

“It might be time to reassess whether half-matched, related transplants can be considered the best alternative donor source for patients lacking a fully matched family member donor. For that, we’ll need more evidence from a randomly controlled, prospective trial, rather than studies that look at patient data retrospectively, to help solidify our findings here.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A retrospective study suggests that, for patients with hematologic disorders, a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)

can be roughly as safe and effective as a fully matched HSCT.

The study showed that, when patients received an identical conditioning regimen, graft T-cell dose, and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, haploidentical and fully matched HSCTs produced comparable results.

Patients had similar rates of overall and progression-free survival, relapse, non-relapse mortality, and chronic GVHD.

However, patients who received haploidentical transplants had higher rates of grade 2-4 acute GVHD and cytomegalovirus reactivation.

Researchers reported these results in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“This is the first study to compare the gold standard to a half-match using an identical protocol,” said Neal Flomenberg, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“The field has debated whether the differences in outcomes between full and partial matches were caused by the quality of the match or by all the procedures the patient goes through before and after the donor cells are administered. We haven’t had a clear answer.”

With that in mind, Dr Flomenberg and his colleagues compared 3-year outcome data from patients who received haploidentical HSCTs (n=50) or fully matched HSCTs (n=27), when both groups of patients were treated with a 2-step protocol.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (n=38), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=20), myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=11), and aplastic anemia (n=1).

The 2-step protocol

All patients received a myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of 12 Gy of total body irradiation administered in 8 fractions over 4 days. After the last fraction, they received a fixed T-cell dose (2 x 108 cells/kg), which was followed, 2 days later, by cyclophosphamide at 60 mg/kg/day for 2 days.

Twenty-four hours after they completed cyclophosphamide, patients received CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cells from a half-matched or fully matched donor.

On day -1, patients began taking tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as GVHD prophylaxis. They also received growth factor support (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor at 250 μg/m2) starting on day +1.

In the absence of GVHD, mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued on day 28 and tacrolimus was tapered, starting on day +60 after HSCT.

Results

The researchers said that early immune recovery was comparable between the patient groups in nearly all assessed T-cell subsets. The exception was the median CD3/CD8 cell count, which was significantly higher at day 28 in the fully matched group than the haploidentical group (P=0.029).

Survival rates were comparable between the groups. The estimated 3-year overall survival was 70% in the haploidentical group and 71% in the fully matched group (P=0.81). The 3-year progression-free survival was 68% and 70%, respectively (P=0.97).

The 3-year cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality was 10% in the haploidentical group and 4% in the fully matched group (P=0.34). The 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 21% and 27%, respectively (P=0.93).

The 100-day cumulative incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—40% and 8%, respectively (P<0.001). But there was no significant difference in the incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD—6% and 4%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2 years was not significantly different between the haploidentical and fully matched groups—19% and 12%, respectively (P=0.47). The same was true for severe chronic GVHD—4% and 8%, respectively (P=0.49).

The cumulative incidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation was significantly higher in the haploidentical group than the fully matched group—68% and 19%, respectively (P<0.001).

There were no deaths from infections or GVHD in either group.

“The results of the current study are certainly encouraging and suggest that outcomes from a half-matched, related donor are similar to fully matched donors,” said study author Sameh Gaballa, MD, also of Thomas Jefferson University.

“It might be time to reassess whether half-matched, related transplants can be considered the best alternative donor source for patients lacking a fully matched family member donor. For that, we’ll need more evidence from a randomly controlled, prospective trial, rather than studies that look at patient data retrospectively, to help solidify our findings here.” ![]()

Team identifies therapeutic target for HIT

Researchers believe they have identified a therapeutic target for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

The team noted that HIT is caused by antibodies to complexes that form between platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released from activated platelets, and heparin or cellular glycosaminoglycans.

The researchers elucidated the crystal structure of 3 PF4 complexes and found evidence suggesting that tetramerization of PF4 is targetable.

Zheng Cai, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

Previously, the researchers identified KKO, a murine monoclonal antibody to PF4/heparin complexes that causes HIT in a murine model. The team said human HIT antibodies compete with KKO for binding to PF4/heparin, and KKO augments the formation of pathogenic immune complexes.

The researchers also identified RTO, an isotype-matched, anti-PF4 antibody that binds to PF4 but does not generate pathogenic complexes.

For the current study, the team described and compared the crystal structures of PF4 in complex with Fabs derived from KKO and RTO to the structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux.

The researchers noted that PF4 molecules can exist singly as monomers, doubly as dimers, and as a 4-part complex called a tetramer, which have an “open” end and a “closed” end.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux showed that fondaparinux binds to the “closed” end of the PF4 tetramer, which stabilizes the tetramer.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with KKO showed that KKO binds to the “open” end of the stabilized tetramer, making contact with 3 of 4 monomers in the tetramer.

The researchers said this helps explain the requirement for heparin as a backbone for the complex. They also said this finding provides new insight into how a normal host protein such as PF4 can be converted into a target of the host immune system, which leads to an autoimmune disorder.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with RTO showed that RTO binds to PF4 monomers rather than tetramers. And RTO binds to the monomers in a way that prevents them from combining into tetramers.

Via cell experiments, the researchers confirmed that RTO prevents the formation of antigenic complexes, as well as the activation of platelets by KKO and human HIT antibodies. RTO also prevented clot formation caused by KKO in a mouse model of HIT.

These results suggest that binding of RTO to PF4 monomers prevents the formation of pathogenic complexes that are central to the pathology of HIT. So the researchers believe RTO can provide the basis for new diagnostics and may pave the way for a therapy to stop HIT early in its progression. ![]()

Researchers believe they have identified a therapeutic target for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

The team noted that HIT is caused by antibodies to complexes that form between platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released from activated platelets, and heparin or cellular glycosaminoglycans.

The researchers elucidated the crystal structure of 3 PF4 complexes and found evidence suggesting that tetramerization of PF4 is targetable.

Zheng Cai, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

Previously, the researchers identified KKO, a murine monoclonal antibody to PF4/heparin complexes that causes HIT in a murine model. The team said human HIT antibodies compete with KKO for binding to PF4/heparin, and KKO augments the formation of pathogenic immune complexes.

The researchers also identified RTO, an isotype-matched, anti-PF4 antibody that binds to PF4 but does not generate pathogenic complexes.

For the current study, the team described and compared the crystal structures of PF4 in complex with Fabs derived from KKO and RTO to the structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux.

The researchers noted that PF4 molecules can exist singly as monomers, doubly as dimers, and as a 4-part complex called a tetramer, which have an “open” end and a “closed” end.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux showed that fondaparinux binds to the “closed” end of the PF4 tetramer, which stabilizes the tetramer.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with KKO showed that KKO binds to the “open” end of the stabilized tetramer, making contact with 3 of 4 monomers in the tetramer.

The researchers said this helps explain the requirement for heparin as a backbone for the complex. They also said this finding provides new insight into how a normal host protein such as PF4 can be converted into a target of the host immune system, which leads to an autoimmune disorder.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with RTO showed that RTO binds to PF4 monomers rather than tetramers. And RTO binds to the monomers in a way that prevents them from combining into tetramers.

Via cell experiments, the researchers confirmed that RTO prevents the formation of antigenic complexes, as well as the activation of platelets by KKO and human HIT antibodies. RTO also prevented clot formation caused by KKO in a mouse model of HIT.

These results suggest that binding of RTO to PF4 monomers prevents the formation of pathogenic complexes that are central to the pathology of HIT. So the researchers believe RTO can provide the basis for new diagnostics and may pave the way for a therapy to stop HIT early in its progression. ![]()

Researchers believe they have identified a therapeutic target for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

The team noted that HIT is caused by antibodies to complexes that form between platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released from activated platelets, and heparin or cellular glycosaminoglycans.

The researchers elucidated the crystal structure of 3 PF4 complexes and found evidence suggesting that tetramerization of PF4 is targetable.

Zheng Cai, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

Previously, the researchers identified KKO, a murine monoclonal antibody to PF4/heparin complexes that causes HIT in a murine model. The team said human HIT antibodies compete with KKO for binding to PF4/heparin, and KKO augments the formation of pathogenic immune complexes.

The researchers also identified RTO, an isotype-matched, anti-PF4 antibody that binds to PF4 but does not generate pathogenic complexes.

For the current study, the team described and compared the crystal structures of PF4 in complex with Fabs derived from KKO and RTO to the structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux.

The researchers noted that PF4 molecules can exist singly as monomers, doubly as dimers, and as a 4-part complex called a tetramer, which have an “open” end and a “closed” end.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with fondaparinux showed that fondaparinux binds to the “closed” end of the PF4 tetramer, which stabilizes the tetramer.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with KKO showed that KKO binds to the “open” end of the stabilized tetramer, making contact with 3 of 4 monomers in the tetramer.

The researchers said this helps explain the requirement for heparin as a backbone for the complex. They also said this finding provides new insight into how a normal host protein such as PF4 can be converted into a target of the host immune system, which leads to an autoimmune disorder.

The crystal structure of PF4 in complex with RTO showed that RTO binds to PF4 monomers rather than tetramers. And RTO binds to the monomers in a way that prevents them from combining into tetramers.

Via cell experiments, the researchers confirmed that RTO prevents the formation of antigenic complexes, as well as the activation of platelets by KKO and human HIT antibodies. RTO also prevented clot formation caused by KKO in a mouse model of HIT.

These results suggest that binding of RTO to PF4 monomers prevents the formation of pathogenic complexes that are central to the pathology of HIT. So the researchers believe RTO can provide the basis for new diagnostics and may pave the way for a therapy to stop HIT early in its progression. ![]()

Reducing SCD patients’ wait time for pain meds

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()

Chemo-free transplant can cure SCD, team says

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Chemotherapy-free allogeneic transplant can cure sickle cell disease (SCD) in adults, according to researchers.

In a phase 1/2 trial, the treatment normalized hemoglobin concentrations, reduced SCD-related complications, and improved cardiopulmonary function in 12 of 13 patients.

The single graft failure was due to noncompliance with post-transplant treatment.

There were no deaths and no cases of graft-vs-host disease. However, most patients did experience some form of transplant-related toxicity.

These transplants were performed at the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System in Chicago. But the chemotherapy-free transplant regimen was developed—and initially tested—at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Physicians there have treated 30 patients with the regimen. An account of that work was published in JAMA last year.

The current study has been published in Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation.

“Adults with sickle cell disease can be cured without chemotherapy—the main barrier that has stood in the way for them for so long,” said study author Damiano Rondelli, MD, of the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System.

“Our data provide more support that this therapy is safe and effective and prevents patients from living shortened lives, condemned to pain and progressive complications.”

Treatment and outcome

The study included 13 patients, ages 17 to 40, who were transplanted between November 2011 and June 2014. Prior to transplant, patients received alemtuzumab and total-body irradiation (300 cGy).

They then received peripheral blood stem cells from matched related donors. All donors were a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen match, but 2 donors had different blood types than the recipients. After transplant, the patients received sirolimus.

All 13 patients initially engrafted, but 1 patient experienced secondary graft failure due to noncompliance with sirolimus.

At a median follow-up of 22 months (range, 12-44), all 13 patients are alive, and 12 have maintained a stable mixed donor/recipient chimerism.

At 1 year after transplant, the 12 patients with stable donor chimerism had significant improvements from baseline in hemoglobin, reticulocyte percentage, lactate dehydrogenase concentration, and cardiopulmonary function.

One of these patients required readmission to the hospital for vaso-occlusive crisis. Before transplant, this patient experienced about 12 crises a year.

No other SCD-related complications have occurred. And 4 patients have been able to stop taking sirolimus without transplant rejection or other complications.

Nine of the engrafted patients completed quality of life assessments before transplant and at 1 year after the procedure. They reported improvements in pain, general health, vitality, and social functioning.

“[W]ith this chemotherapy-free transplant, we are curing adults with sickle cell disease, and we see that their quality of life improves vastly within just 1 month of the transplant,” Dr Rondelli said. “They are able to go back to school, go back to work, and can experience life without pain.”

Toxicity

Four patients did not experience any transplant-related toxicity. And there were no cases of acute or chronic graft-vs-host disease.

One patient developed gram-negative rods in her hip prosthesis after transplant, 1 patient experienced delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction after exchange transfusion, 1 patient developed viral pharyngitis, and 1 patient developed Coxsackie B.

One patient developed a urinary tract infection due to extended spectrum beta-lactamase, Clostridium difficile colitis, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Two patients had grade 2 mucositis, one of whom also developed line-associated deep vein thrombosis and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation. Two other patients had CMV reactivation as well, one of whom also had methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia.

All 3 patients with CMV reactivation were successfully treated with valgancyclovir and did not develop CMV disease.

Six patients had arthralgias attributed to sirolimus, and 2 of them required dose reductions.

One patient developed chest pain and a decline in carbon monoxide diffusion capacity by 30% that was attributed to sirolimus. The patient was switched to cyclosporine but developed posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and was then put on mycophenolate mofetil.

The patient has since maintained stable donor chimerism, and the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity has increased to near-baseline value. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Chemotherapy-free allogeneic transplant can cure sickle cell disease (SCD) in adults, according to researchers.

In a phase 1/2 trial, the treatment normalized hemoglobin concentrations, reduced SCD-related complications, and improved cardiopulmonary function in 12 of 13 patients.

The single graft failure was due to noncompliance with post-transplant treatment.

There were no deaths and no cases of graft-vs-host disease. However, most patients did experience some form of transplant-related toxicity.

These transplants were performed at the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System in Chicago. But the chemotherapy-free transplant regimen was developed—and initially tested—at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Physicians there have treated 30 patients with the regimen. An account of that work was published in JAMA last year.

The current study has been published in Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation.

“Adults with sickle cell disease can be cured without chemotherapy—the main barrier that has stood in the way for them for so long,” said study author Damiano Rondelli, MD, of the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System.

“Our data provide more support that this therapy is safe and effective and prevents patients from living shortened lives, condemned to pain and progressive complications.”

Treatment and outcome

The study included 13 patients, ages 17 to 40, who were transplanted between November 2011 and June 2014. Prior to transplant, patients received alemtuzumab and total-body irradiation (300 cGy).

They then received peripheral blood stem cells from matched related donors. All donors were a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen match, but 2 donors had different blood types than the recipients. After transplant, the patients received sirolimus.

All 13 patients initially engrafted, but 1 patient experienced secondary graft failure due to noncompliance with sirolimus.