User login

FDA grants drug orphan designation for ITP

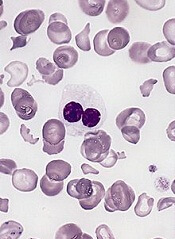

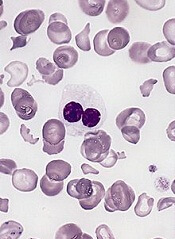

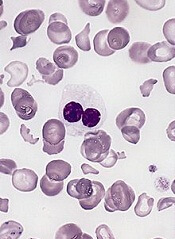

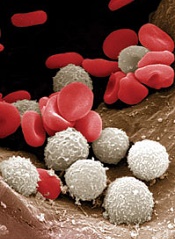

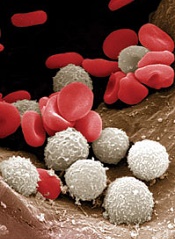

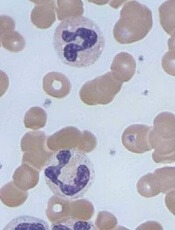

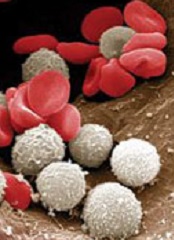

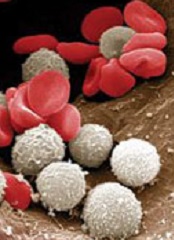

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to veltuzumab for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Veltuzumab is a 2nd-generation, humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD20. The drug is being developed by Immunomedics as a treatment for ITP, other autoimmune diseases, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Veltuzumab was considered active and well-tolerated in a phase 1 study of adults with ITP. The drug produced responses in about half of patients, with some responses lasting more than 4 years.

The study included 50 patients with primary ITP who had failed 1 or more types of standard therapy, had platelet levels of 30,000/μL or less, and did not have major bleeding. The patients’ median age was 54, and most were female (n=31). Eight patients had undergone splenectomy.

Patients were a median of 2 years from diagnosis. Fourteen had been diagnosed with ITP for a year or less and had received corticosteroids and/or immunoglobulins.

Thirty-six patients had chronic ITP and had received azathioprine or danazol (n=15), thrombopoietin-receptor agonists (n=10), rituximab (n=7), platelets (n=5), and/or chemotherapy (n=4).

The 34 patients assigned to cohort 1 received 2 doses of subcutaneous veltuzumab at 80 mg, 160 mg, or 320 mg, 2 weeks apart (total doses of 160 mg, 320 mg, and 640 mg, respectively). The 18 patients in cohort 2 (which included 2 rollovers) received once-weekly doses at 320 mg for 4 weeks (total dose of 1280 mg).

The researchers said veltuzumab was well tolerated. The only adverse events were grade 1-2, transient injection reactions.

Forty-seven patients were evaluable for response. Forty-seven percent (n=22) had objective responses (ORs), and 28% (n=13) had complete responses (CRs).

Responses did not differ much according to disease duration. Patients with chronic ITP had an OR rate of 42% and a CR rate of 27%. Patients who had ITP for a year or less had an OR rate of 51% and a CR rate of 29%.

The median time to relapse (TTR) did not differ much between patients with CRs and those with partial responses, but there was a sizable difference between patients with chronic ITP and those with newly diagnosed ITP.

The median TTR was 7.9 months for patients with a CR and 7.6 months for patients with a partial response. The median TTR was 6.9 months for patients with chronic ITP and 14.4 months for patients who had ITP for a year or less.

The phase 2 expansion trial of veltuzumab in ITP has completed accrual, and patients are being followed for up to 5 years.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US. Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives.

The orphan designation for veltuzumab provides Immunomedics with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to veltuzumab for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Veltuzumab is a 2nd-generation, humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD20. The drug is being developed by Immunomedics as a treatment for ITP, other autoimmune diseases, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Veltuzumab was considered active and well-tolerated in a phase 1 study of adults with ITP. The drug produced responses in about half of patients, with some responses lasting more than 4 years.

The study included 50 patients with primary ITP who had failed 1 or more types of standard therapy, had platelet levels of 30,000/μL or less, and did not have major bleeding. The patients’ median age was 54, and most were female (n=31). Eight patients had undergone splenectomy.

Patients were a median of 2 years from diagnosis. Fourteen had been diagnosed with ITP for a year or less and had received corticosteroids and/or immunoglobulins.

Thirty-six patients had chronic ITP and had received azathioprine or danazol (n=15), thrombopoietin-receptor agonists (n=10), rituximab (n=7), platelets (n=5), and/or chemotherapy (n=4).

The 34 patients assigned to cohort 1 received 2 doses of subcutaneous veltuzumab at 80 mg, 160 mg, or 320 mg, 2 weeks apart (total doses of 160 mg, 320 mg, and 640 mg, respectively). The 18 patients in cohort 2 (which included 2 rollovers) received once-weekly doses at 320 mg for 4 weeks (total dose of 1280 mg).

The researchers said veltuzumab was well tolerated. The only adverse events were grade 1-2, transient injection reactions.

Forty-seven patients were evaluable for response. Forty-seven percent (n=22) had objective responses (ORs), and 28% (n=13) had complete responses (CRs).

Responses did not differ much according to disease duration. Patients with chronic ITP had an OR rate of 42% and a CR rate of 27%. Patients who had ITP for a year or less had an OR rate of 51% and a CR rate of 29%.

The median time to relapse (TTR) did not differ much between patients with CRs and those with partial responses, but there was a sizable difference between patients with chronic ITP and those with newly diagnosed ITP.

The median TTR was 7.9 months for patients with a CR and 7.6 months for patients with a partial response. The median TTR was 6.9 months for patients with chronic ITP and 14.4 months for patients who had ITP for a year or less.

The phase 2 expansion trial of veltuzumab in ITP has completed accrual, and patients are being followed for up to 5 years.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US. Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives.

The orphan designation for veltuzumab provides Immunomedics with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to veltuzumab for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Veltuzumab is a 2nd-generation, humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD20. The drug is being developed by Immunomedics as a treatment for ITP, other autoimmune diseases, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Veltuzumab was considered active and well-tolerated in a phase 1 study of adults with ITP. The drug produced responses in about half of patients, with some responses lasting more than 4 years.

The study included 50 patients with primary ITP who had failed 1 or more types of standard therapy, had platelet levels of 30,000/μL or less, and did not have major bleeding. The patients’ median age was 54, and most were female (n=31). Eight patients had undergone splenectomy.

Patients were a median of 2 years from diagnosis. Fourteen had been diagnosed with ITP for a year or less and had received corticosteroids and/or immunoglobulins.

Thirty-six patients had chronic ITP and had received azathioprine or danazol (n=15), thrombopoietin-receptor agonists (n=10), rituximab (n=7), platelets (n=5), and/or chemotherapy (n=4).

The 34 patients assigned to cohort 1 received 2 doses of subcutaneous veltuzumab at 80 mg, 160 mg, or 320 mg, 2 weeks apart (total doses of 160 mg, 320 mg, and 640 mg, respectively). The 18 patients in cohort 2 (which included 2 rollovers) received once-weekly doses at 320 mg for 4 weeks (total dose of 1280 mg).

The researchers said veltuzumab was well tolerated. The only adverse events were grade 1-2, transient injection reactions.

Forty-seven patients were evaluable for response. Forty-seven percent (n=22) had objective responses (ORs), and 28% (n=13) had complete responses (CRs).

Responses did not differ much according to disease duration. Patients with chronic ITP had an OR rate of 42% and a CR rate of 27%. Patients who had ITP for a year or less had an OR rate of 51% and a CR rate of 29%.

The median time to relapse (TTR) did not differ much between patients with CRs and those with partial responses, but there was a sizable difference between patients with chronic ITP and those with newly diagnosed ITP.

The median TTR was 7.9 months for patients with a CR and 7.6 months for patients with a partial response. The median TTR was 6.9 months for patients with chronic ITP and 14.4 months for patients who had ITP for a year or less.

The phase 2 expansion trial of veltuzumab in ITP has completed accrual, and patients are being followed for up to 5 years.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US. Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives.

The orphan designation for veltuzumab provides Immunomedics with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Lenalidomide can treat pulmonary sarcoidosis in MDS

Treatment with lenalidomide can have a significant effect on pulmonary sarcoidosis in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), according to a case study.

The case was a 71-year-old woman with newly diagnosed 5q-MDS and a long-standing history of refractory pulmonary sarcoidosis.

After 2 cycles of treatment with lenalidomide, the patient had substantial improvements in lung function, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life.

This case is the first of its kind to show the potential effects of lenalidomide as a therapeutic option in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Ali Bazargan, MD, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described this case in CHEST.

The patient had a 12-year history of stage IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with no extrapulmonary organ involvement. She had never smoked but had a history of hypertension that was managed with perindopril.

The patient presented with refractory and worsening dyspnea, despite receiving long-term therapy with methotrexate and inhaled and systemic corticosteroids. Before she began receiving lenalidomide, the patient was taking 15 mg of prednisolone and 400 mg of inhaled budesonide daily.

Blood tests revealed the patient had macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 81 g/L; mean corpuscular volume, 114 fL).

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed hypocellular marrow with trilineage dysplasia consistent with 5q-MDS but no evidence of noncaseating granulomas. So the patient began receiving lenalidomide at 10 mg daily.

While the researchers were trying to establish her diagnosis of 5q-MDS, the patient became transfusion-dependent and experienced severe dyspnea, fatigue, and a considerable decline in quality of life.

A chest CT scan revealed irregular masses in her lung, with bibasal alveolar infiltrates that had developed within a 12-month period.

However, after 2 cycles of lenalidomide, the patient had significant improvements in dyspnea, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life. Lung function testing showed an increase in vital capacity from 1.73 L to 1.93 L.

And a chest CT scan performed 4 months after the patient began taking lenalidomide showed that the bibasal alveolar infiltrates had completely cleared.

During this period, the patient’s dose of prednisolone was reduced from 15 mg daily to 5 mg on alternate days, but she continues to receive the same dose of lenalidomide. ![]()

Treatment with lenalidomide can have a significant effect on pulmonary sarcoidosis in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), according to a case study.

The case was a 71-year-old woman with newly diagnosed 5q-MDS and a long-standing history of refractory pulmonary sarcoidosis.

After 2 cycles of treatment with lenalidomide, the patient had substantial improvements in lung function, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life.

This case is the first of its kind to show the potential effects of lenalidomide as a therapeutic option in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Ali Bazargan, MD, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described this case in CHEST.

The patient had a 12-year history of stage IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with no extrapulmonary organ involvement. She had never smoked but had a history of hypertension that was managed with perindopril.

The patient presented with refractory and worsening dyspnea, despite receiving long-term therapy with methotrexate and inhaled and systemic corticosteroids. Before she began receiving lenalidomide, the patient was taking 15 mg of prednisolone and 400 mg of inhaled budesonide daily.

Blood tests revealed the patient had macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 81 g/L; mean corpuscular volume, 114 fL).

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed hypocellular marrow with trilineage dysplasia consistent with 5q-MDS but no evidence of noncaseating granulomas. So the patient began receiving lenalidomide at 10 mg daily.

While the researchers were trying to establish her diagnosis of 5q-MDS, the patient became transfusion-dependent and experienced severe dyspnea, fatigue, and a considerable decline in quality of life.

A chest CT scan revealed irregular masses in her lung, with bibasal alveolar infiltrates that had developed within a 12-month period.

However, after 2 cycles of lenalidomide, the patient had significant improvements in dyspnea, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life. Lung function testing showed an increase in vital capacity from 1.73 L to 1.93 L.

And a chest CT scan performed 4 months after the patient began taking lenalidomide showed that the bibasal alveolar infiltrates had completely cleared.

During this period, the patient’s dose of prednisolone was reduced from 15 mg daily to 5 mg on alternate days, but she continues to receive the same dose of lenalidomide. ![]()

Treatment with lenalidomide can have a significant effect on pulmonary sarcoidosis in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), according to a case study.

The case was a 71-year-old woman with newly diagnosed 5q-MDS and a long-standing history of refractory pulmonary sarcoidosis.

After 2 cycles of treatment with lenalidomide, the patient had substantial improvements in lung function, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life.

This case is the first of its kind to show the potential effects of lenalidomide as a therapeutic option in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Ali Bazargan, MD, of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described this case in CHEST.

The patient had a 12-year history of stage IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with no extrapulmonary organ involvement. She had never smoked but had a history of hypertension that was managed with perindopril.

The patient presented with refractory and worsening dyspnea, despite receiving long-term therapy with methotrexate and inhaled and systemic corticosteroids. Before she began receiving lenalidomide, the patient was taking 15 mg of prednisolone and 400 mg of inhaled budesonide daily.

Blood tests revealed the patient had macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 81 g/L; mean corpuscular volume, 114 fL).

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed hypocellular marrow with trilineage dysplasia consistent with 5q-MDS but no evidence of noncaseating granulomas. So the patient began receiving lenalidomide at 10 mg daily.

While the researchers were trying to establish her diagnosis of 5q-MDS, the patient became transfusion-dependent and experienced severe dyspnea, fatigue, and a considerable decline in quality of life.

A chest CT scan revealed irregular masses in her lung, with bibasal alveolar infiltrates that had developed within a 12-month period.

However, after 2 cycles of lenalidomide, the patient had significant improvements in dyspnea, fatigue, daily activity, and quality of life. Lung function testing showed an increase in vital capacity from 1.73 L to 1.93 L.

And a chest CT scan performed 4 months after the patient began taking lenalidomide showed that the bibasal alveolar infiltrates had completely cleared.

During this period, the patient’s dose of prednisolone was reduced from 15 mg daily to 5 mg on alternate days, but she continues to receive the same dose of lenalidomide. ![]()

Inhibitor could treat range of hematologic disorders

A small molecule that targets the sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway has advanced to phase 2 trials in a range of hematologic disorders.

In a phase 1 study, the inhibitor, PF-04449913, exhibited activity in adults with leukemias, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and myelofibrosis (MF).

Sixty percent of the patients studied experienced treatment-related adverse events (AEs), but there were no treatment-related deaths. Most deaths were disease-related.

Researchers detailed the results of this trial in The Lancet Haematology. The study was funded by Pfizer, the company developing PF-04449913, as well as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and European Leukemia Net.

Preclinical research showed that PF-04449913 forces dormant cancer stem cells in the bone marrow to begin differentiating and exit into the blood stream where they can be destroyed by chemotherapy agents targeting dividing cells.

“This drug gets that unwanted house guests to leave and never come back,” said Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“It’s a significant step forward in treating people with refractory or resistant myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and myelofibrosis. It’s a bonus that the drug can be administered as easily as an aspirin, in a single, daily, oral tablet.”

For the first-in-human study, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues evaluated PF-04449913 in 47 adult patients. Twenty-eight of them had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 6 had MDS, 5 had chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), 1 had chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), and 7 had MF.

Eighty-five percent of patients (n=40) had an ECOG performance status of 0-1. Eighty-one percent (n=38) had received previous systemic treatment, and 47% (n=22) had received 3 or more previous treatment regimens.

Patients received escalating daily doses of PF-04449913 in 28-day cycles. Treatment cycles were repeated until a patient experienced unacceptable AEs without evidence of clinical improvement. Patients who showed clinical activity without experiencing serious AEs received additional treatment cycles.

Dosing and AEs

Patients received PF-04449913 once daily at 5 mg (n=3), 10 mg (n=3), 20 mg (n=4), 40 mg (n=4), 80 mg (n=8), 120 mg (n=3), 180 mg (n=3), 270 mg (n=5), 400 mg (n=9), or 600 mg (n=5).

The researchers found the maximum-tolerated dose to be 400 mg once daily. The mean half-life was 23.9 hours in this dose group, and pharmacokinetics seemed to be dose-proportional.

Two patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities, 1 in the 80 mg group (grade 3 hypoxia and grade 3 pleural effusion), and 1 in the 600 mg group (grade 3 peripheral edema).

In all, 60% of patients (n=28) experienced treatment-related AEs. The most common were dysgeusia (28%), decreased appetite (19%), and alopecia (15%). There were 3 grade 4 AEs—1 case of neutropenia and 2 cases of thrombocytopenia.

There were 15 deaths, none of which were treatment-related. Eleven deaths were disease-related, and the remaining 4 were related to infection.

Clinical activity

The researchers said there was “some suggestion of clinical activity” in 23 patients (49%).

Of the 5 patients with CML (2 chronic phase and 3 blast phase), 1 patient with blast phase CML had a partial cytogenetic response to PF-04449913.

Of the 6 patients with MDS and 1 with CMML, 4 had stable disease after treatment. Two of these patients had hematologic improvement.

Two of the 7 patients with MF had clinical improvement.

Of the 28 patients with AML, 16 showed evidence of possible biological activity. One patient had a complete response and 4 had a partial response with incomplete hematologic recovery. Four AML patients had minor responses, and 7 had stable disease.

Given these results, PF-04449913 is now being investigated in 5 phase 2 trials of hematologic disorders, 4 of which are recruiting participants.

“Our hope is that this drug will enable more effective treatment to begin earlier and that, with earlier intervention, we can alter the course of disease and remove the need for, or improve the chances of success with, bone marrow transplantation,” Dr Jamieson said. “It’s all about reducing the burden of disease by intervening early.” ![]()

A small molecule that targets the sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway has advanced to phase 2 trials in a range of hematologic disorders.

In a phase 1 study, the inhibitor, PF-04449913, exhibited activity in adults with leukemias, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and myelofibrosis (MF).

Sixty percent of the patients studied experienced treatment-related adverse events (AEs), but there were no treatment-related deaths. Most deaths were disease-related.

Researchers detailed the results of this trial in The Lancet Haematology. The study was funded by Pfizer, the company developing PF-04449913, as well as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and European Leukemia Net.

Preclinical research showed that PF-04449913 forces dormant cancer stem cells in the bone marrow to begin differentiating and exit into the blood stream where they can be destroyed by chemotherapy agents targeting dividing cells.

“This drug gets that unwanted house guests to leave and never come back,” said Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“It’s a significant step forward in treating people with refractory or resistant myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and myelofibrosis. It’s a bonus that the drug can be administered as easily as an aspirin, in a single, daily, oral tablet.”

For the first-in-human study, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues evaluated PF-04449913 in 47 adult patients. Twenty-eight of them had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 6 had MDS, 5 had chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), 1 had chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), and 7 had MF.

Eighty-five percent of patients (n=40) had an ECOG performance status of 0-1. Eighty-one percent (n=38) had received previous systemic treatment, and 47% (n=22) had received 3 or more previous treatment regimens.

Patients received escalating daily doses of PF-04449913 in 28-day cycles. Treatment cycles were repeated until a patient experienced unacceptable AEs without evidence of clinical improvement. Patients who showed clinical activity without experiencing serious AEs received additional treatment cycles.

Dosing and AEs

Patients received PF-04449913 once daily at 5 mg (n=3), 10 mg (n=3), 20 mg (n=4), 40 mg (n=4), 80 mg (n=8), 120 mg (n=3), 180 mg (n=3), 270 mg (n=5), 400 mg (n=9), or 600 mg (n=5).

The researchers found the maximum-tolerated dose to be 400 mg once daily. The mean half-life was 23.9 hours in this dose group, and pharmacokinetics seemed to be dose-proportional.

Two patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities, 1 in the 80 mg group (grade 3 hypoxia and grade 3 pleural effusion), and 1 in the 600 mg group (grade 3 peripheral edema).

In all, 60% of patients (n=28) experienced treatment-related AEs. The most common were dysgeusia (28%), decreased appetite (19%), and alopecia (15%). There were 3 grade 4 AEs—1 case of neutropenia and 2 cases of thrombocytopenia.

There were 15 deaths, none of which were treatment-related. Eleven deaths were disease-related, and the remaining 4 were related to infection.

Clinical activity

The researchers said there was “some suggestion of clinical activity” in 23 patients (49%).

Of the 5 patients with CML (2 chronic phase and 3 blast phase), 1 patient with blast phase CML had a partial cytogenetic response to PF-04449913.

Of the 6 patients with MDS and 1 with CMML, 4 had stable disease after treatment. Two of these patients had hematologic improvement.

Two of the 7 patients with MF had clinical improvement.

Of the 28 patients with AML, 16 showed evidence of possible biological activity. One patient had a complete response and 4 had a partial response with incomplete hematologic recovery. Four AML patients had minor responses, and 7 had stable disease.

Given these results, PF-04449913 is now being investigated in 5 phase 2 trials of hematologic disorders, 4 of which are recruiting participants.

“Our hope is that this drug will enable more effective treatment to begin earlier and that, with earlier intervention, we can alter the course of disease and remove the need for, or improve the chances of success with, bone marrow transplantation,” Dr Jamieson said. “It’s all about reducing the burden of disease by intervening early.” ![]()

A small molecule that targets the sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway has advanced to phase 2 trials in a range of hematologic disorders.

In a phase 1 study, the inhibitor, PF-04449913, exhibited activity in adults with leukemias, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and myelofibrosis (MF).

Sixty percent of the patients studied experienced treatment-related adverse events (AEs), but there were no treatment-related deaths. Most deaths were disease-related.

Researchers detailed the results of this trial in The Lancet Haematology. The study was funded by Pfizer, the company developing PF-04449913, as well as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and European Leukemia Net.

Preclinical research showed that PF-04449913 forces dormant cancer stem cells in the bone marrow to begin differentiating and exit into the blood stream where they can be destroyed by chemotherapy agents targeting dividing cells.

“This drug gets that unwanted house guests to leave and never come back,” said Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“It’s a significant step forward in treating people with refractory or resistant myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and myelofibrosis. It’s a bonus that the drug can be administered as easily as an aspirin, in a single, daily, oral tablet.”

For the first-in-human study, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues evaluated PF-04449913 in 47 adult patients. Twenty-eight of them had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 6 had MDS, 5 had chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), 1 had chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), and 7 had MF.

Eighty-five percent of patients (n=40) had an ECOG performance status of 0-1. Eighty-one percent (n=38) had received previous systemic treatment, and 47% (n=22) had received 3 or more previous treatment regimens.

Patients received escalating daily doses of PF-04449913 in 28-day cycles. Treatment cycles were repeated until a patient experienced unacceptable AEs without evidence of clinical improvement. Patients who showed clinical activity without experiencing serious AEs received additional treatment cycles.

Dosing and AEs

Patients received PF-04449913 once daily at 5 mg (n=3), 10 mg (n=3), 20 mg (n=4), 40 mg (n=4), 80 mg (n=8), 120 mg (n=3), 180 mg (n=3), 270 mg (n=5), 400 mg (n=9), or 600 mg (n=5).

The researchers found the maximum-tolerated dose to be 400 mg once daily. The mean half-life was 23.9 hours in this dose group, and pharmacokinetics seemed to be dose-proportional.

Two patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities, 1 in the 80 mg group (grade 3 hypoxia and grade 3 pleural effusion), and 1 in the 600 mg group (grade 3 peripheral edema).

In all, 60% of patients (n=28) experienced treatment-related AEs. The most common were dysgeusia (28%), decreased appetite (19%), and alopecia (15%). There were 3 grade 4 AEs—1 case of neutropenia and 2 cases of thrombocytopenia.

There were 15 deaths, none of which were treatment-related. Eleven deaths were disease-related, and the remaining 4 were related to infection.

Clinical activity

The researchers said there was “some suggestion of clinical activity” in 23 patients (49%).

Of the 5 patients with CML (2 chronic phase and 3 blast phase), 1 patient with blast phase CML had a partial cytogenetic response to PF-04449913.

Of the 6 patients with MDS and 1 with CMML, 4 had stable disease after treatment. Two of these patients had hematologic improvement.

Two of the 7 patients with MF had clinical improvement.

Of the 28 patients with AML, 16 showed evidence of possible biological activity. One patient had a complete response and 4 had a partial response with incomplete hematologic recovery. Four AML patients had minor responses, and 7 had stable disease.

Given these results, PF-04449913 is now being investigated in 5 phase 2 trials of hematologic disorders, 4 of which are recruiting participants.

“Our hope is that this drug will enable more effective treatment to begin earlier and that, with earlier intervention, we can alter the course of disease and remove the need for, or improve the chances of success with, bone marrow transplantation,” Dr Jamieson said. “It’s all about reducing the burden of disease by intervening early.” ![]()

CHMP recommends eltrombopag for SAA

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for eltrombopag (Revolade) as a treatment for adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who have had an insufficient response to immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and are not eligible to receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

If approved by the European Commission, eltrombopag would be the first treatment option in its class for these patients.

The European Commission will review the CHMP recommendation and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The decision will be applicable to all 28 European Union member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Phase 2 trial of eltrombopag in SAA

The CHMP’s positive opinion of eltrombopag is mainly based on results of a phase 2 trial (NCT00922883). Results from this ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013.

The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least one prior IST and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) received at least 2 prior ISTs.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least one lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 6 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments. The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for eltrombopag (Revolade) as a treatment for adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who have had an insufficient response to immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and are not eligible to receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

If approved by the European Commission, eltrombopag would be the first treatment option in its class for these patients.

The European Commission will review the CHMP recommendation and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The decision will be applicable to all 28 European Union member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Phase 2 trial of eltrombopag in SAA

The CHMP’s positive opinion of eltrombopag is mainly based on results of a phase 2 trial (NCT00922883). Results from this ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013.

The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least one prior IST and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) received at least 2 prior ISTs.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least one lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 6 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments. The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended approval for eltrombopag (Revolade) as a treatment for adults with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) who have had an insufficient response to immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and are not eligible to receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

If approved by the European Commission, eltrombopag would be the first treatment option in its class for these patients.

The European Commission will review the CHMP recommendation and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The decision will be applicable to all 28 European Union member states plus Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

Phase 2 trial of eltrombopag in SAA

The CHMP’s positive opinion of eltrombopag is mainly based on results of a phase 2 trial (NCT00922883). Results from this ongoing study were published in NEJM in 2012 and Blood in 2013.

The trial has enrolled 43 patients with SAA who had an insufficient response to at least one prior IST and who had a platelet count of 30 x 109/L or less.

At baseline, the median platelet count was 20 x 109/L, hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL, the absolute neutrophil count was 0.58 x 109/L, and absolute reticulocyte count was 24.3 x 109/L.

Patients had a median age of 45 (range, 17 to 77), and 56% were male. The majority of patients (84%) received at least 2 prior ISTs.

Patients received eltrombopag at an initial dose of 50 mg once daily for 2 weeks. The dose increased over 2-week periods to a maximum of 150 mg once daily.

The study’s primary endpoint was hematologic response, which was initially assessed after 12 weeks of treatment. Treatment was discontinued after 16 weeks in patients who did not exhibit a hematologic response.

Forty percent of patients (n=17) experienced a hematologic response in at least one lineage—platelets, red blood cells (RBCs), or white blood cells—after week 12.

In the extension phase of the study, 8 patients achieved a multilineage response. Four of these patients subsequently tapered off treatment and maintained the response. The median follow up was 8.1 months (range, 7.2 to 10.6 months).

Ninety-one percent of patients were platelet-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require platelet transfusions for a median of 200 days (range, 8 to 1096 days).

Eighty-six percent of patients were RBC-transfusion-dependent at baseline. Patients who responded to eltrombopag did not require RBC transfusions for a median of 208 days (range, 15 to 1082 days).

The most common adverse events (≥20%) associated with eltrombopag were nausea (33%), fatigue (28%), cough (23%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (21%).

Patients were also evaluated for cytogenetic abnormalities. Eight patients had a new cytogenetic abnormality after treatment, including 5 patients who had complex changes in chromosome 7.

Patients who develop new cytogenetic abnormalities while on eltrombopag may need to be taken off treatment.

About eltrombopag

Eltrombopag is already approved to treat SAA in the US and Canada. The drug recently gained approval in the US to treat children age 6 and older who have chronic immune thrombocytopenia and have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

Eltrombopag is approved in more than 100 countries to treat adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of other treatments. The drug is approved in more than 45 countries for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic hepatitis C to allow them to initiate and maintain interferon-based therapy.

Eltrombopag is marketed under the brand name Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more details on the drug, see the European Medicines Agency’s Summary of Product Characteristics. ![]()

Team discovers ‘new avenue’ for TTP treatment

Image by Erhabor Osaro

Researchers say they have uncovered a new avenue for therapeutic intervention in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

The team discovered how autoimmune antibodies in a TTP patient recognize and bind to ADAMTS13.

They believe this knowledge could help them alter ADAMTS13 to produce a therapeutic enzyme that can elude recognition by autoimmune antibodies yet still retain its ability to cleave von Willebrand factor.

Such an enzyme could be given to TTP patients in the hospital to speed recovery and cut the cost of treatment.

Long Zheng, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers found that 5 small loops in ADAMTS13’s amino acid sequence are necessary for autoantibodies to bind to ADAMTS13.

Cutting or substituting several amino acids out of any of the 5 loops prevented binding. Small deletions in a loop also left the enzyme unable to cleave von Willebrand factor.

“This was really surprising,” Dr Zheng said. “It’s like a table with 5 legs. If you take 1 away, it should still stand, but, somehow, it collapsed. This suggests that you need the coordinated activity of all 5.”

Thus, it appears that the autoimmune antibodies in TTP patients inhibit the enzyme by physically blocking the recognition site of ADAMTS13 for von Willebrand factor.

Analyses of autoantibodies from 23 more TTP patients revealed that most use the same binding site. This suggests modifying the ADAMTS13 enzyme by protein engineering may be able to help a wide range of TTP patients.

Details of the research

Dr Zheng and his colleagues first isolated messenger RNAs that code single chains of variable regions of monoclonal antibodies from B cells collected from patients with acquired TTP.

The team used phage display to select the messenger RNAs that code specific antibodies that bind and inhibit ADAMTS13. These monoclonal antibodies were then expressed in E coli cells, purified, and biochemically characterized.

Three inhibitory monoclonal antibodies were selected for further study by hydrogen-deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry. This technology uses amine hydrogen exchange with deuterium on each amino acid residue except proline.

After the reaction was stopped, the protein was cut into small pieces (or peptide fragments) and run through high-performance liquid chromatography for separation and mass spectrometry for identification.

Antibody binding sites were detected by their ability to block the hydrogen and deuterium exchange, as compared with ADAMTS13 that was unbound.

One of the 3 high-affinity probes selected by phage display was used for the competition experiments against polyclonal autoimmune antibodies from 23 TTP patients.

The results show that this particular binding epitope is common among patients with acquired autoimmune TTP. ![]()

Image by Erhabor Osaro

Researchers say they have uncovered a new avenue for therapeutic intervention in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

The team discovered how autoimmune antibodies in a TTP patient recognize and bind to ADAMTS13.

They believe this knowledge could help them alter ADAMTS13 to produce a therapeutic enzyme that can elude recognition by autoimmune antibodies yet still retain its ability to cleave von Willebrand factor.

Such an enzyme could be given to TTP patients in the hospital to speed recovery and cut the cost of treatment.

Long Zheng, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers found that 5 small loops in ADAMTS13’s amino acid sequence are necessary for autoantibodies to bind to ADAMTS13.

Cutting or substituting several amino acids out of any of the 5 loops prevented binding. Small deletions in a loop also left the enzyme unable to cleave von Willebrand factor.

“This was really surprising,” Dr Zheng said. “It’s like a table with 5 legs. If you take 1 away, it should still stand, but, somehow, it collapsed. This suggests that you need the coordinated activity of all 5.”

Thus, it appears that the autoimmune antibodies in TTP patients inhibit the enzyme by physically blocking the recognition site of ADAMTS13 for von Willebrand factor.

Analyses of autoantibodies from 23 more TTP patients revealed that most use the same binding site. This suggests modifying the ADAMTS13 enzyme by protein engineering may be able to help a wide range of TTP patients.

Details of the research

Dr Zheng and his colleagues first isolated messenger RNAs that code single chains of variable regions of monoclonal antibodies from B cells collected from patients with acquired TTP.

The team used phage display to select the messenger RNAs that code specific antibodies that bind and inhibit ADAMTS13. These monoclonal antibodies were then expressed in E coli cells, purified, and biochemically characterized.

Three inhibitory monoclonal antibodies were selected for further study by hydrogen-deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry. This technology uses amine hydrogen exchange with deuterium on each amino acid residue except proline.

After the reaction was stopped, the protein was cut into small pieces (or peptide fragments) and run through high-performance liquid chromatography for separation and mass spectrometry for identification.

Antibody binding sites were detected by their ability to block the hydrogen and deuterium exchange, as compared with ADAMTS13 that was unbound.

One of the 3 high-affinity probes selected by phage display was used for the competition experiments against polyclonal autoimmune antibodies from 23 TTP patients.

The results show that this particular binding epitope is common among patients with acquired autoimmune TTP. ![]()

Image by Erhabor Osaro

Researchers say they have uncovered a new avenue for therapeutic intervention in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

The team discovered how autoimmune antibodies in a TTP patient recognize and bind to ADAMTS13.

They believe this knowledge could help them alter ADAMTS13 to produce a therapeutic enzyme that can elude recognition by autoimmune antibodies yet still retain its ability to cleave von Willebrand factor.

Such an enzyme could be given to TTP patients in the hospital to speed recovery and cut the cost of treatment.

Long Zheng, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers found that 5 small loops in ADAMTS13’s amino acid sequence are necessary for autoantibodies to bind to ADAMTS13.

Cutting or substituting several amino acids out of any of the 5 loops prevented binding. Small deletions in a loop also left the enzyme unable to cleave von Willebrand factor.

“This was really surprising,” Dr Zheng said. “It’s like a table with 5 legs. If you take 1 away, it should still stand, but, somehow, it collapsed. This suggests that you need the coordinated activity of all 5.”

Thus, it appears that the autoimmune antibodies in TTP patients inhibit the enzyme by physically blocking the recognition site of ADAMTS13 for von Willebrand factor.

Analyses of autoantibodies from 23 more TTP patients revealed that most use the same binding site. This suggests modifying the ADAMTS13 enzyme by protein engineering may be able to help a wide range of TTP patients.

Details of the research

Dr Zheng and his colleagues first isolated messenger RNAs that code single chains of variable regions of monoclonal antibodies from B cells collected from patients with acquired TTP.

The team used phage display to select the messenger RNAs that code specific antibodies that bind and inhibit ADAMTS13. These monoclonal antibodies were then expressed in E coli cells, purified, and biochemically characterized.

Three inhibitory monoclonal antibodies were selected for further study by hydrogen-deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry. This technology uses amine hydrogen exchange with deuterium on each amino acid residue except proline.

After the reaction was stopped, the protein was cut into small pieces (or peptide fragments) and run through high-performance liquid chromatography for separation and mass spectrometry for identification.

Antibody binding sites were detected by their ability to block the hydrogen and deuterium exchange, as compared with ADAMTS13 that was unbound.

One of the 3 high-affinity probes selected by phage display was used for the competition experiments against polyclonal autoimmune antibodies from 23 TTP patients.

The results show that this particular binding epitope is common among patients with acquired autoimmune TTP. ![]()

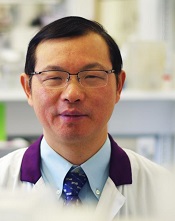

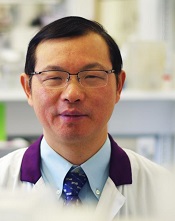

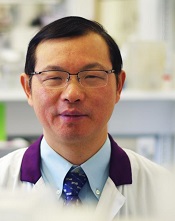

A new way to treat ITP?

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

St. Michael’s Hospital

New research appears to explain why symptoms and treatment responses vary in patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). The work has also revealed a new potential treatment option.

Researchers previously thought that all ITP antibodies lead platelets to the spleen for destruction.

But the new study, published in Nature Communications, has shown that some ITP antibodies destroy platelets in the liver.

“Every existing treatment for ITP has been dedicated to stopping antibodies from destroying platelets in the spleen, but we’ve discovered that some antibodies actually destroy platelets in the liver,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The discovery was made by analyzing mice treated with two monoclonal antibodies, each targeting a different protein on the surface of platelets—GPIb or GPIIbIIIa.

The researchers found that antibodies targeting GPIb lead to platelet destruction in the liver, and those targeting GPIIbIIIa cause platelet destruction in the spleen.

“By detecting the specific antibodies present in someone with ITP, we may be able to detect where and how the immune system will attack,” Dr Ni said. “And because we now know the liver’s immune response destroys platelets covered with GPIb, we may be able to design new therapies to stop this type of platelet destruction.”

Dr Ni noted that sialidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu) may be able to inhibit the liver’s immune response to the platelets. In fact, he and his colleagues used human blood samples to test whether Tamiflu might inhibit antibodies targeting GPIb.

“Using healthy blood samples and ITP antibodies in a test tube, we showed that Tamiflu may impede platelet destruction for those with antibodies that target GPIb,” Dr Ni said.

Based on an early abstract of this research, some ITP patients around the world have been treated with oseltamivir phosphate. These patients were extremely resistant to existing treatments targeting the spleen, and their ITP was considered life-threatening.

Although these instances of experimental treatment have been successful, Dr Ni said more research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of this approach. ![]()

Arginine plays role in thalassemia complication

Low bioavailability of the amino acid arginine may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

Via previous work, the team found that arginine deficiency is a major factor in acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease.

With the current study, they discovered that arginase activity and concentration correlate with echocardiographic and cardiac-MRI measurements of cardiopulmonary function.

Claudia R. Morris, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues described this research in the British Journal of Haematology.

“We are finding that arginine dysregulation is an important hematologic mechanism beyond sickle cell disease,” Dr Morris said. “This new study shows that it plays a role in thalassemia patients as well and may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Interventions aimed at restoring arginine bioavailability could be a promising area of focus for new therapeutics.”

Dr Morris and her colleagues noted that pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common problem in patients with thalassemia. An elevated tricuspid-regurgitant jet-velocity (TRV) of 2.5 m/s or greater on Doppler echocardiography can identify patients with an increased risk of PH. But a right heart catheterization is required to confirm the condition.

The researchers wanted to provide a comprehensive description of the cardiopulmonary and biological profile of thalassemia patients at risk of developing PH. So they analyzed 27 patients with β-thalassemia.

Fourteen patients had an elevated TRV (≥ 2.5 m/s). According to echocardiography, these patients had a significantly larger right atrial size (P=0.03), left atrial size (P=0.002), left ventricular (LV) mass (P=0.03), and left septal-wall thickness (P=0.03) than patients with a TRV below 2.5 m/s.

According to MRI, patients with elevated TRV had significantly higher left atrial volume than patients with a TRV < 2.5 m/s (P=0.008).

Patients with an elevated TRV also had elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (P=0.03) and biomarkers of abnormal coagulation, including thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04) and monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.02).

Patients with a TRV ≥ 2.5 m/s had significantly lower plasma arginine concentration (P<0.001) and biomarkers of global arginine bioavailability, including plasma arginine/ornithine ratio (P=0.01) and mean plasma global arginine bioavailability ratio (arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratio, P=0.04).

These patients also had significantly higher arginase concentration and activity than patients with TRV below 2.5 m/s (P=0.02).

These findings prompted the researchers to evaluate the relationship between arginase activity/concentration and clinical and laboratory markers of disease severity.

They found that arginase concentration was significantly correlated with several parameters of cardiovascular function, including left atrial volume (echo and MRI), right atrial volume (MRI), LV end systolic volume (echo and MRI), LV end diastolic volume (echo and MRI), LV mass (echo and MRI), and cardiac index (echo).

Arginase concentration was also significantly correlated with white blood cell count (P=0.03), plasma arginine (P=0.0002), arginine/ornithine (P=0.01) and arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratios (P=0.05), and hemoglobin (P=0.02), bilirubin (P=0.02), and LDH levels (P=0.001).

In multiple regression analysis, only cardiac index, bilirubin, and plasma arginine/ornithine ratio remained significantly associated with arginase concentration (P<0.05 for all).

Arginase activity was significantly correlated with several biomarkers of coagulation, including monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.04), thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04), and tissue factor concentration (P=0.02).

Considering these results together, the researchers said it seems low arginine bioavailability contributes to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia. ![]()

Low bioavailability of the amino acid arginine may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

Via previous work, the team found that arginine deficiency is a major factor in acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease.

With the current study, they discovered that arginase activity and concentration correlate with echocardiographic and cardiac-MRI measurements of cardiopulmonary function.

Claudia R. Morris, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues described this research in the British Journal of Haematology.

“We are finding that arginine dysregulation is an important hematologic mechanism beyond sickle cell disease,” Dr Morris said. “This new study shows that it plays a role in thalassemia patients as well and may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Interventions aimed at restoring arginine bioavailability could be a promising area of focus for new therapeutics.”

Dr Morris and her colleagues noted that pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common problem in patients with thalassemia. An elevated tricuspid-regurgitant jet-velocity (TRV) of 2.5 m/s or greater on Doppler echocardiography can identify patients with an increased risk of PH. But a right heart catheterization is required to confirm the condition.

The researchers wanted to provide a comprehensive description of the cardiopulmonary and biological profile of thalassemia patients at risk of developing PH. So they analyzed 27 patients with β-thalassemia.

Fourteen patients had an elevated TRV (≥ 2.5 m/s). According to echocardiography, these patients had a significantly larger right atrial size (P=0.03), left atrial size (P=0.002), left ventricular (LV) mass (P=0.03), and left septal-wall thickness (P=0.03) than patients with a TRV below 2.5 m/s.

According to MRI, patients with elevated TRV had significantly higher left atrial volume than patients with a TRV < 2.5 m/s (P=0.008).

Patients with an elevated TRV also had elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (P=0.03) and biomarkers of abnormal coagulation, including thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04) and monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.02).

Patients with a TRV ≥ 2.5 m/s had significantly lower plasma arginine concentration (P<0.001) and biomarkers of global arginine bioavailability, including plasma arginine/ornithine ratio (P=0.01) and mean plasma global arginine bioavailability ratio (arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratio, P=0.04).

These patients also had significantly higher arginase concentration and activity than patients with TRV below 2.5 m/s (P=0.02).

These findings prompted the researchers to evaluate the relationship between arginase activity/concentration and clinical and laboratory markers of disease severity.

They found that arginase concentration was significantly correlated with several parameters of cardiovascular function, including left atrial volume (echo and MRI), right atrial volume (MRI), LV end systolic volume (echo and MRI), LV end diastolic volume (echo and MRI), LV mass (echo and MRI), and cardiac index (echo).

Arginase concentration was also significantly correlated with white blood cell count (P=0.03), plasma arginine (P=0.0002), arginine/ornithine (P=0.01) and arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratios (P=0.05), and hemoglobin (P=0.02), bilirubin (P=0.02), and LDH levels (P=0.001).

In multiple regression analysis, only cardiac index, bilirubin, and plasma arginine/ornithine ratio remained significantly associated with arginase concentration (P<0.05 for all).

Arginase activity was significantly correlated with several biomarkers of coagulation, including monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.04), thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04), and tissue factor concentration (P=0.02).

Considering these results together, the researchers said it seems low arginine bioavailability contributes to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia. ![]()

Low bioavailability of the amino acid arginine may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

Via previous work, the team found that arginine deficiency is a major factor in acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease.

With the current study, they discovered that arginase activity and concentration correlate with echocardiographic and cardiac-MRI measurements of cardiopulmonary function.

Claudia R. Morris, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues described this research in the British Journal of Haematology.

“We are finding that arginine dysregulation is an important hematologic mechanism beyond sickle cell disease,” Dr Morris said. “This new study shows that it plays a role in thalassemia patients as well and may contribute to cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Interventions aimed at restoring arginine bioavailability could be a promising area of focus for new therapeutics.”

Dr Morris and her colleagues noted that pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common problem in patients with thalassemia. An elevated tricuspid-regurgitant jet-velocity (TRV) of 2.5 m/s or greater on Doppler echocardiography can identify patients with an increased risk of PH. But a right heart catheterization is required to confirm the condition.

The researchers wanted to provide a comprehensive description of the cardiopulmonary and biological profile of thalassemia patients at risk of developing PH. So they analyzed 27 patients with β-thalassemia.

Fourteen patients had an elevated TRV (≥ 2.5 m/s). According to echocardiography, these patients had a significantly larger right atrial size (P=0.03), left atrial size (P=0.002), left ventricular (LV) mass (P=0.03), and left septal-wall thickness (P=0.03) than patients with a TRV below 2.5 m/s.

According to MRI, patients with elevated TRV had significantly higher left atrial volume than patients with a TRV < 2.5 m/s (P=0.008).

Patients with an elevated TRV also had elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (P=0.03) and biomarkers of abnormal coagulation, including thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04) and monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.02).

Patients with a TRV ≥ 2.5 m/s had significantly lower plasma arginine concentration (P<0.001) and biomarkers of global arginine bioavailability, including plasma arginine/ornithine ratio (P=0.01) and mean plasma global arginine bioavailability ratio (arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratio, P=0.04).

These patients also had significantly higher arginase concentration and activity than patients with TRV below 2.5 m/s (P=0.02).

These findings prompted the researchers to evaluate the relationship between arginase activity/concentration and clinical and laboratory markers of disease severity.

They found that arginase concentration was significantly correlated with several parameters of cardiovascular function, including left atrial volume (echo and MRI), right atrial volume (MRI), LV end systolic volume (echo and MRI), LV end diastolic volume (echo and MRI), LV mass (echo and MRI), and cardiac index (echo).

Arginase concentration was also significantly correlated with white blood cell count (P=0.03), plasma arginine (P=0.0002), arginine/ornithine (P=0.01) and arginine/ornithine + citrulline ratios (P=0.05), and hemoglobin (P=0.02), bilirubin (P=0.02), and LDH levels (P=0.001).

In multiple regression analysis, only cardiac index, bilirubin, and plasma arginine/ornithine ratio remained significantly associated with arginase concentration (P<0.05 for all).

Arginase activity was significantly correlated with several biomarkers of coagulation, including monoclonal prothrombin fragment 1.2 (P=0.04), thrombin-antithrombin complex (P=0.04), and tissue factor concentration (P=0.02).

Considering these results together, the researchers said it seems low arginine bioavailability contributes to cardiopulmonary dysfunction in patients with β-thalassemia.

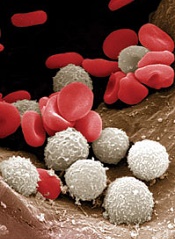

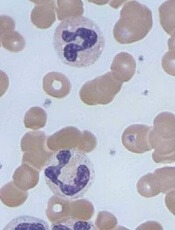

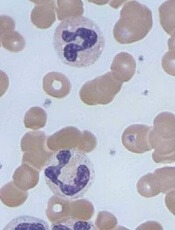

Neutrophils cause hemorrhage in thrombocytopenia

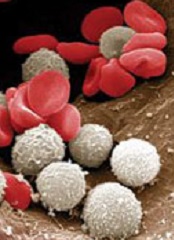

Image by Volker Brinkmann

Researchers have found that hemorrhage occurs in the context of thrombocytopenia when neutrophils cross the endothelial barrier.

The team also identified ways to inhibit this diapedesis and prevent hemorrhage in mouse models.

If these results can be replicated in humans, such interventions could prevent bleeding in patients with immune thrombocytopenia and certain patients receiving chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Carina Hillgruber, PhD, of the University of Munster in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Previous studies showed that an absence of platelets alone was not sufficient to cause hemorrhage. Inflammation was required. But the exact cause of bleeding complications in thrombocytopenia was unknown.

With their research, Dr Hillgruber and her colleagues found that neutrophils are recruited to inflammatory sites to induce thrombocytopenic tissue hemorrhage. The process consists of Gαi2-mediated neutrophil transmigratory activity and opening of the endothelial barrier via VE-cadherin.

So the researchers speculated that preventing neutrophil diapedesis by either tightening the endothelial barrier or targeting neutrophil transmigratory activity would prevent hemorrhage.

The team showed they could inhibit the interaction between neutrophils and the endothelium by interfering with P-selectin, β2integrin-mediated adhesion, and chemokine signaling. This led to reduced inflammatory bleeding in thrombocytopenic mice.

The researchers also found they could interfere with Gαi signaling in neutrophils (which is critical for the cells’ transmigration) via treatment with pertussis toxin or gene ablation. And this protected thrombocytopenic mice from cutaneous hemorrhage.

Finally, the team showed that mice harboring the VE-cadherin mutation Y731F were protected from hemorrhage despite having low platelet counts and immune complex-mediated vasculitis.

The researchers said these findings suggest therapeutically targeting neutrophil diapedesis through the endothelial barrier could potentially prevent hemorrhage in patients with thrombocytopenia.

The team noted that platelets must seal the damage induced by neutrophil diapedesis, but they could only speculate as to how that occurs.

Image by Volker Brinkmann

Researchers have found that hemorrhage occurs in the context of thrombocytopenia when neutrophils cross the endothelial barrier.

The team also identified ways to inhibit this diapedesis and prevent hemorrhage in mouse models.

If these results can be replicated in humans, such interventions could prevent bleeding in patients with immune thrombocytopenia and certain patients receiving chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Carina Hillgruber, PhD, of the University of Munster in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Previous studies showed that an absence of platelets alone was not sufficient to cause hemorrhage. Inflammation was required. But the exact cause of bleeding complications in thrombocytopenia was unknown.

With their research, Dr Hillgruber and her colleagues found that neutrophils are recruited to inflammatory sites to induce thrombocytopenic tissue hemorrhage. The process consists of Gαi2-mediated neutrophil transmigratory activity and opening of the endothelial barrier via VE-cadherin.

So the researchers speculated that preventing neutrophil diapedesis by either tightening the endothelial barrier or targeting neutrophil transmigratory activity would prevent hemorrhage.

The team showed they could inhibit the interaction between neutrophils and the endothelium by interfering with P-selectin, β2integrin-mediated adhesion, and chemokine signaling. This led to reduced inflammatory bleeding in thrombocytopenic mice.

The researchers also found they could interfere with Gαi signaling in neutrophils (which is critical for the cells’ transmigration) via treatment with pertussis toxin or gene ablation. And this protected thrombocytopenic mice from cutaneous hemorrhage.

Finally, the team showed that mice harboring the VE-cadherin mutation Y731F were protected from hemorrhage despite having low platelet counts and immune complex-mediated vasculitis.

The researchers said these findings suggest therapeutically targeting neutrophil diapedesis through the endothelial barrier could potentially prevent hemorrhage in patients with thrombocytopenia.

The team noted that platelets must seal the damage induced by neutrophil diapedesis, but they could only speculate as to how that occurs.

Image by Volker Brinkmann

Researchers have found that hemorrhage occurs in the context of thrombocytopenia when neutrophils cross the endothelial barrier.

The team also identified ways to inhibit this diapedesis and prevent hemorrhage in mouse models.

If these results can be replicated in humans, such interventions could prevent bleeding in patients with immune thrombocytopenia and certain patients receiving chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Carina Hillgruber, PhD, of the University of Munster in Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research and detailed the results in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Previous studies showed that an absence of platelets alone was not sufficient to cause hemorrhage. Inflammation was required. But the exact cause of bleeding complications in thrombocytopenia was unknown.

With their research, Dr Hillgruber and her colleagues found that neutrophils are recruited to inflammatory sites to induce thrombocytopenic tissue hemorrhage. The process consists of Gαi2-mediated neutrophil transmigratory activity and opening of the endothelial barrier via VE-cadherin.

So the researchers speculated that preventing neutrophil diapedesis by either tightening the endothelial barrier or targeting neutrophil transmigratory activity would prevent hemorrhage.

The team showed they could inhibit the interaction between neutrophils and the endothelium by interfering with P-selectin, β2integrin-mediated adhesion, and chemokine signaling. This led to reduced inflammatory bleeding in thrombocytopenic mice.

The researchers also found they could interfere with Gαi signaling in neutrophils (which is critical for the cells’ transmigration) via treatment with pertussis toxin or gene ablation. And this protected thrombocytopenic mice from cutaneous hemorrhage.

Finally, the team showed that mice harboring the VE-cadherin mutation Y731F were protected from hemorrhage despite having low platelet counts and immune complex-mediated vasculitis.

The researchers said these findings suggest therapeutically targeting neutrophil diapedesis through the endothelial barrier could potentially prevent hemorrhage in patients with thrombocytopenia.

The team noted that platelets must seal the damage induced by neutrophil diapedesis, but they could only speculate as to how that occurs.

ASCO updates guideline on CSFs

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has updated its clinical practice guideline on hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors (CSFs).

The guideline includes recommendations on the use of CSFs in the context of lymphoma, solid tumor malignancies, pediatric leukemia, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

There are no recommendations pertaining to adults with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

ASCO’s previous guideline on CSFs was issued in 2006. For the update, an ASCO expert panel conducted a formal systematic review of relevant articles from the medical literature published from October 2005 through September 2014.

Key recommendations from the resulting guideline are as follows.

Pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz (and other biosimilars, as they become available) can be used for the prevention of treatment-related febrile neutropenia.

For patients with lymphomas or solid tumors, primary prophylaxis with a CSF should be given during all cycles of chemotherapy in patients who have an approximately 20% or higher risk for febrile neutropenia on the basis of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors.

However, clinicians should also consider using chemotherapy regimens that do not require CSF administration but are as effective as regimens that do require a CSF.

Patients with lymphomas or solid tumors should receive secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis with a CSF if they experienced a neutropenic complication from a previous cycle of chemotherapy (for which they did not receive primary prophylaxis) when a reduced dose or treatment delay may compromise disease-free survival, overall survival, or treatment outcome.

However, the guideline also says that, in many clinical situations, dose reductions or delays may be a reasonable alternative.

CSFs should not be routinely used for patients with neutropenia who are afebrile or as adjunctive treatment with antibiotic therapy for patients with fever and neutropenia.