User login

FDA strengthens warnings for anemia drug

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has strengthened an existing warning that serious, potentially fatal, allergic reactions can occur with the anemia drug Feraheme (ferumoxytol).

The FDA changed the drug’s prescribing information and approved a boxed warning detailing this risk.

The agency also added a new contraindication, which advises against the use of Feraheme in patients who have had an allergic reaction to any intravenous (IV) iron replacement product.

The FDA said it is continuing to monitor and evaluate the risk of serious allergic reactions with all IV iron products, and the agency will update the public as new information becomes available.

About Feraheme

Feraheme is an IV iron replacement product used to treat iron-deficiency anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Like other IV iron products, Feraheme may only be given where emergency personnel and equipment are immediately available to treat the potentially life-threatening allergic reactions that can occur with treatment.

All IV iron products carry a risk of potentially life-threatening allergic reactions. At the time of Feraheme’s approval in 2009, this risk was described in the “Warnings and Precautions” section of the drug label.

Since then, serious reactions, including deaths, have occurred, despite the proper use of therapies to treat these reactions and emergency resuscitation measures.

Serious reactions reported

In the initial clinical trials of Feraheme, conducted predominantly in patients with chronic kidney disease, serious hypersensitivity reactions were reported in 0.2% (3/1726) of patients receiving Feraheme.

Other adverse reactions potentially associated with hypersensitivity (eg, pruritus, rash, urticaria, or wheezing) were reported in 3.7% (63/1726) of these patients.

In other trials that did not include patients with chronic kidney disease, moderate to severe hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, were reported in 2.6% (26/1014) of patients treated with Feraheme.

Since the approval of Feraheme on June 30, 2009, cases of serious hypersensitivity reactions, including death, have occurred.

A search of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database revealed 79 cases of anaphylactic reactions associated with Feraheme administration, reported from the time of approval to June 30, 2014. Of the 79 cases, 18 were fatal, despite immediate medical intervention and emergency resuscitation attempts.

The 79 patients ranged in age from 19 to 96 years. In nearly half of all cases, the anaphylactic reactions occurred with the first dose of Feraheme. For approximately 75% (60/79) of the cases, the reaction began during the infusion or within 5 minutes after administration was complete.

Frequently reported symptoms included cardiac arrest, hypotension, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and flushing. Of the 79 patients, 43% (34/79) had a medical history of drug allergy, and 24% had a history of multiple drug allergies.

Recommendations for administering Feraheme

Initial symptoms of fatal and serious hypersensitivity reactions associated with Feraheme may include hypotension, syncope, unresponsiveness, and cardiac/cardiorespiratory arrest, with or without signs of rash.

All IV iron products carry a risk of anaphylaxis, so these products should be administered only in patients who require IV iron therapy.

Feraheme is only approved for use in adults with iron-deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic kidney disease. The drug is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to Feraheme or any other IV iron product.

Only administer Feraheme and other IV iron products when personnel and therapies are immediately available for the treatment of anaphylaxis and other hypersensitivity reactions.

Patients with a history of multiple drug allergies may have a greater risk of anaphylaxis with parenteral iron products. Carefully consider the potential risks and benefits before administering Feraheme to these patients.

Feraheme should only be administered as an IV infusion in 50-200 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose over a minimum period of 15 minutes following dilution. Do not administer Feraheme by undiluted IV injection.

Closely monitor patients for signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions, including monitoring blood pressure and pulse during administration and for at least 30 minutes following each infusion of Feraheme.

Elderly patients 65 years of age and older with multiple or serious comorbidities who experience hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both following administration of Feraheme may have more severe outcomes.

Advise patients to immediately report any signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity that may develop during and following Feraheme administration, such as respiratory distress, hypotension, dizziness or lightheadedness, edema, rash, or itching. Advise patients to seek immediate medical attention if these signs and symptoms occur.

Allow at least 30 minutes between administration of Feraheme and administration of other medications that could potentially cause serious hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both, such as chemotherapeutic agents or monoclonal antibodies.

Report adverse events involving Feraheme to the FDA’s MedWatch Program. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has strengthened an existing warning that serious, potentially fatal, allergic reactions can occur with the anemia drug Feraheme (ferumoxytol).

The FDA changed the drug’s prescribing information and approved a boxed warning detailing this risk.

The agency also added a new contraindication, which advises against the use of Feraheme in patients who have had an allergic reaction to any intravenous (IV) iron replacement product.

The FDA said it is continuing to monitor and evaluate the risk of serious allergic reactions with all IV iron products, and the agency will update the public as new information becomes available.

About Feraheme

Feraheme is an IV iron replacement product used to treat iron-deficiency anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Like other IV iron products, Feraheme may only be given where emergency personnel and equipment are immediately available to treat the potentially life-threatening allergic reactions that can occur with treatment.

All IV iron products carry a risk of potentially life-threatening allergic reactions. At the time of Feraheme’s approval in 2009, this risk was described in the “Warnings and Precautions” section of the drug label.

Since then, serious reactions, including deaths, have occurred, despite the proper use of therapies to treat these reactions and emergency resuscitation measures.

Serious reactions reported

In the initial clinical trials of Feraheme, conducted predominantly in patients with chronic kidney disease, serious hypersensitivity reactions were reported in 0.2% (3/1726) of patients receiving Feraheme.

Other adverse reactions potentially associated with hypersensitivity (eg, pruritus, rash, urticaria, or wheezing) were reported in 3.7% (63/1726) of these patients.

In other trials that did not include patients with chronic kidney disease, moderate to severe hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, were reported in 2.6% (26/1014) of patients treated with Feraheme.

Since the approval of Feraheme on June 30, 2009, cases of serious hypersensitivity reactions, including death, have occurred.

A search of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database revealed 79 cases of anaphylactic reactions associated with Feraheme administration, reported from the time of approval to June 30, 2014. Of the 79 cases, 18 were fatal, despite immediate medical intervention and emergency resuscitation attempts.

The 79 patients ranged in age from 19 to 96 years. In nearly half of all cases, the anaphylactic reactions occurred with the first dose of Feraheme. For approximately 75% (60/79) of the cases, the reaction began during the infusion or within 5 minutes after administration was complete.

Frequently reported symptoms included cardiac arrest, hypotension, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and flushing. Of the 79 patients, 43% (34/79) had a medical history of drug allergy, and 24% had a history of multiple drug allergies.

Recommendations for administering Feraheme

Initial symptoms of fatal and serious hypersensitivity reactions associated with Feraheme may include hypotension, syncope, unresponsiveness, and cardiac/cardiorespiratory arrest, with or without signs of rash.

All IV iron products carry a risk of anaphylaxis, so these products should be administered only in patients who require IV iron therapy.

Feraheme is only approved for use in adults with iron-deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic kidney disease. The drug is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to Feraheme or any other IV iron product.

Only administer Feraheme and other IV iron products when personnel and therapies are immediately available for the treatment of anaphylaxis and other hypersensitivity reactions.

Patients with a history of multiple drug allergies may have a greater risk of anaphylaxis with parenteral iron products. Carefully consider the potential risks and benefits before administering Feraheme to these patients.

Feraheme should only be administered as an IV infusion in 50-200 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose over a minimum period of 15 minutes following dilution. Do not administer Feraheme by undiluted IV injection.

Closely monitor patients for signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions, including monitoring blood pressure and pulse during administration and for at least 30 minutes following each infusion of Feraheme.

Elderly patients 65 years of age and older with multiple or serious comorbidities who experience hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both following administration of Feraheme may have more severe outcomes.

Advise patients to immediately report any signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity that may develop during and following Feraheme administration, such as respiratory distress, hypotension, dizziness or lightheadedness, edema, rash, or itching. Advise patients to seek immediate medical attention if these signs and symptoms occur.

Allow at least 30 minutes between administration of Feraheme and administration of other medications that could potentially cause serious hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both, such as chemotherapeutic agents or monoclonal antibodies.

Report adverse events involving Feraheme to the FDA’s MedWatch Program. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has strengthened an existing warning that serious, potentially fatal, allergic reactions can occur with the anemia drug Feraheme (ferumoxytol).

The FDA changed the drug’s prescribing information and approved a boxed warning detailing this risk.

The agency also added a new contraindication, which advises against the use of Feraheme in patients who have had an allergic reaction to any intravenous (IV) iron replacement product.

The FDA said it is continuing to monitor and evaluate the risk of serious allergic reactions with all IV iron products, and the agency will update the public as new information becomes available.

About Feraheme

Feraheme is an IV iron replacement product used to treat iron-deficiency anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Like other IV iron products, Feraheme may only be given where emergency personnel and equipment are immediately available to treat the potentially life-threatening allergic reactions that can occur with treatment.

All IV iron products carry a risk of potentially life-threatening allergic reactions. At the time of Feraheme’s approval in 2009, this risk was described in the “Warnings and Precautions” section of the drug label.

Since then, serious reactions, including deaths, have occurred, despite the proper use of therapies to treat these reactions and emergency resuscitation measures.

Serious reactions reported

In the initial clinical trials of Feraheme, conducted predominantly in patients with chronic kidney disease, serious hypersensitivity reactions were reported in 0.2% (3/1726) of patients receiving Feraheme.

Other adverse reactions potentially associated with hypersensitivity (eg, pruritus, rash, urticaria, or wheezing) were reported in 3.7% (63/1726) of these patients.

In other trials that did not include patients with chronic kidney disease, moderate to severe hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, were reported in 2.6% (26/1014) of patients treated with Feraheme.

Since the approval of Feraheme on June 30, 2009, cases of serious hypersensitivity reactions, including death, have occurred.

A search of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database revealed 79 cases of anaphylactic reactions associated with Feraheme administration, reported from the time of approval to June 30, 2014. Of the 79 cases, 18 were fatal, despite immediate medical intervention and emergency resuscitation attempts.

The 79 patients ranged in age from 19 to 96 years. In nearly half of all cases, the anaphylactic reactions occurred with the first dose of Feraheme. For approximately 75% (60/79) of the cases, the reaction began during the infusion or within 5 minutes after administration was complete.

Frequently reported symptoms included cardiac arrest, hypotension, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and flushing. Of the 79 patients, 43% (34/79) had a medical history of drug allergy, and 24% had a history of multiple drug allergies.

Recommendations for administering Feraheme

Initial symptoms of fatal and serious hypersensitivity reactions associated with Feraheme may include hypotension, syncope, unresponsiveness, and cardiac/cardiorespiratory arrest, with or without signs of rash.

All IV iron products carry a risk of anaphylaxis, so these products should be administered only in patients who require IV iron therapy.

Feraheme is only approved for use in adults with iron-deficiency anemia in the setting of chronic kidney disease. The drug is contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to Feraheme or any other IV iron product.

Only administer Feraheme and other IV iron products when personnel and therapies are immediately available for the treatment of anaphylaxis and other hypersensitivity reactions.

Patients with a history of multiple drug allergies may have a greater risk of anaphylaxis with parenteral iron products. Carefully consider the potential risks and benefits before administering Feraheme to these patients.

Feraheme should only be administered as an IV infusion in 50-200 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose over a minimum period of 15 minutes following dilution. Do not administer Feraheme by undiluted IV injection.

Closely monitor patients for signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions, including monitoring blood pressure and pulse during administration and for at least 30 minutes following each infusion of Feraheme.

Elderly patients 65 years of age and older with multiple or serious comorbidities who experience hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both following administration of Feraheme may have more severe outcomes.

Advise patients to immediately report any signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity that may develop during and following Feraheme administration, such as respiratory distress, hypotension, dizziness or lightheadedness, edema, rash, or itching. Advise patients to seek immediate medical attention if these signs and symptoms occur.

Allow at least 30 minutes between administration of Feraheme and administration of other medications that could potentially cause serious hypersensitivity reactions, hypotension, or both, such as chemotherapeutic agents or monoclonal antibodies.

Report adverse events involving Feraheme to the FDA’s MedWatch Program. ![]()

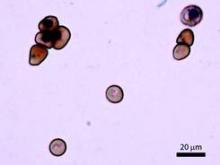

FDA grants drug orphan status to treat PKD

Image courtesy of NHLBI

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to AG-348 for the treatment of pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD), a rare form of hemolytic anemia.

AG-348 is a small molecule allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase-R enzymes that directly targets the underlying metabolic defect in PKD.

The orphan designation will provide Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing AG-348, with certain benefits. These include market exclusivity upon regulatory approval and exemption from FDA application fees and tax credits for qualified clinical trials.

According to Agios, AG-348 exhibited favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in a pair of phase 1 studies conducted in healthy volunteers.

Study investigators also observed dose-dependent changes in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 2,3-DPG blood levels, which are consistent with increased activity of the glycolytic pathway, the expected pharmacodynamic effect of AG-348.

Results from both studies were presented in a poster at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 4007*). One of the studies was a single ascending dose (SAD) study, and the other was a multiple ascending dose (MAD) study.

SAD study

In this study, healthy volunteers were randomized to receive AG-348 (n=36) or placebo (n=12). Patients were divided into 6 dosing cohorts: 30 mg, 120 mg, 360 mg, 700 mg, 1400 mg, and 2500 mg.

The maximum-tolerated dose of AG-348 was not reached, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) or early withdrawals among AG-348-treated subjects. Overall, the rate of AEs was 33.3% in the placebo arm and 44.4% in the AG-348 arm.

The rate of AEs that were considered possibly treatment-related was 16.7% in the placebo arm and 30.6% in the AG-348 arm. The most common treatment-related AEs were headache (occurring in 16.7% and 11.1% of patients, respectively), nausea (0% and 13.9%, respectively), and vomiting (0% and 5.6%, respectively).

Exposure to AG-348, as measured by area under the concentration × time curve (AUC), increased in a dose-proportional manner after a single dose. And absorption was rapid (median Tmax ranged from 0.77 to 4.07 hours), although Tmax increased and there was a less-than-proportional increase in Cmax at higher doses.

When AG-348 was administered from 30 mg to 360 mg, there was a dose-dependent decrease in blood 2,3-DPG levels over 24 hours—up to a 49% mean decrease. Increasing the dose beyond 360 mg did not result in additional decreases in 2,3-DPG levels. And levels returned to placebo levels after about 72 hours.

There were minimal increases in blood ATP levels after AG-348 treatment at any dose.

MAD study

At the time of the presentation, 2 cohorts of 8 subjects each (6 receiving AG-348 and 2 receiving placebo) had completed treatment in the MAD study. One cohort received drug or placebo at 120 mg BID, and the other received 360 mg BID.

The pharmacokinetic results for day 1 of this study were consistent with those of the SAD study. However, the Cmax and AUC0-Ʈ were lower on day 14 than day 1. Investigators said this suggests that multiple doses of AG-348 increase the rate of its own metabolism.

They also said the decrease in exposure observed on day 14 is consistent with preclinical data that suggest AG-348 is a moderate inducer of CYP3A4, which is the major route of the oxidative metabolism of AG-348.

As in the SAD study, the investigators observed decreases in 2,3-DPG blood levels after the first dose in cohorts 1 and 2—up to a 48% mean decrease from baseline for both doses. Concentrations returned to placebo levels between 48 and 72 hours after the last dose.

Unlike in the SAD study, patients in this study had increases in ATP—up to a 52% mean increase from baseline in both dosing cohorts. ATP levels remained elevated through 72 hours after the last dose.

The investigators said the results of these 2 studies have informed dose selection for the planned phase 2 study of AG-348 in PKD patients, which is expected to begin soon. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Image courtesy of NHLBI

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to AG-348 for the treatment of pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD), a rare form of hemolytic anemia.

AG-348 is a small molecule allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase-R enzymes that directly targets the underlying metabolic defect in PKD.

The orphan designation will provide Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing AG-348, with certain benefits. These include market exclusivity upon regulatory approval and exemption from FDA application fees and tax credits for qualified clinical trials.

According to Agios, AG-348 exhibited favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in a pair of phase 1 studies conducted in healthy volunteers.

Study investigators also observed dose-dependent changes in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 2,3-DPG blood levels, which are consistent with increased activity of the glycolytic pathway, the expected pharmacodynamic effect of AG-348.

Results from both studies were presented in a poster at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 4007*). One of the studies was a single ascending dose (SAD) study, and the other was a multiple ascending dose (MAD) study.

SAD study

In this study, healthy volunteers were randomized to receive AG-348 (n=36) or placebo (n=12). Patients were divided into 6 dosing cohorts: 30 mg, 120 mg, 360 mg, 700 mg, 1400 mg, and 2500 mg.

The maximum-tolerated dose of AG-348 was not reached, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) or early withdrawals among AG-348-treated subjects. Overall, the rate of AEs was 33.3% in the placebo arm and 44.4% in the AG-348 arm.

The rate of AEs that were considered possibly treatment-related was 16.7% in the placebo arm and 30.6% in the AG-348 arm. The most common treatment-related AEs were headache (occurring in 16.7% and 11.1% of patients, respectively), nausea (0% and 13.9%, respectively), and vomiting (0% and 5.6%, respectively).

Exposure to AG-348, as measured by area under the concentration × time curve (AUC), increased in a dose-proportional manner after a single dose. And absorption was rapid (median Tmax ranged from 0.77 to 4.07 hours), although Tmax increased and there was a less-than-proportional increase in Cmax at higher doses.

When AG-348 was administered from 30 mg to 360 mg, there was a dose-dependent decrease in blood 2,3-DPG levels over 24 hours—up to a 49% mean decrease. Increasing the dose beyond 360 mg did not result in additional decreases in 2,3-DPG levels. And levels returned to placebo levels after about 72 hours.

There were minimal increases in blood ATP levels after AG-348 treatment at any dose.

MAD study

At the time of the presentation, 2 cohorts of 8 subjects each (6 receiving AG-348 and 2 receiving placebo) had completed treatment in the MAD study. One cohort received drug or placebo at 120 mg BID, and the other received 360 mg BID.

The pharmacokinetic results for day 1 of this study were consistent with those of the SAD study. However, the Cmax and AUC0-Ʈ were lower on day 14 than day 1. Investigators said this suggests that multiple doses of AG-348 increase the rate of its own metabolism.

They also said the decrease in exposure observed on day 14 is consistent with preclinical data that suggest AG-348 is a moderate inducer of CYP3A4, which is the major route of the oxidative metabolism of AG-348.

As in the SAD study, the investigators observed decreases in 2,3-DPG blood levels after the first dose in cohorts 1 and 2—up to a 48% mean decrease from baseline for both doses. Concentrations returned to placebo levels between 48 and 72 hours after the last dose.

Unlike in the SAD study, patients in this study had increases in ATP—up to a 52% mean increase from baseline in both dosing cohorts. ATP levels remained elevated through 72 hours after the last dose.

The investigators said the results of these 2 studies have informed dose selection for the planned phase 2 study of AG-348 in PKD patients, which is expected to begin soon. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Image courtesy of NHLBI

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to AG-348 for the treatment of pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD), a rare form of hemolytic anemia.

AG-348 is a small molecule allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase-R enzymes that directly targets the underlying metabolic defect in PKD.

The orphan designation will provide Agios Pharmaceuticals, the company developing AG-348, with certain benefits. These include market exclusivity upon regulatory approval and exemption from FDA application fees and tax credits for qualified clinical trials.

According to Agios, AG-348 exhibited favorable safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in a pair of phase 1 studies conducted in healthy volunteers.

Study investigators also observed dose-dependent changes in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 2,3-DPG blood levels, which are consistent with increased activity of the glycolytic pathway, the expected pharmacodynamic effect of AG-348.

Results from both studies were presented in a poster at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 4007*). One of the studies was a single ascending dose (SAD) study, and the other was a multiple ascending dose (MAD) study.

SAD study

In this study, healthy volunteers were randomized to receive AG-348 (n=36) or placebo (n=12). Patients were divided into 6 dosing cohorts: 30 mg, 120 mg, 360 mg, 700 mg, 1400 mg, and 2500 mg.

The maximum-tolerated dose of AG-348 was not reached, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs) or early withdrawals among AG-348-treated subjects. Overall, the rate of AEs was 33.3% in the placebo arm and 44.4% in the AG-348 arm.

The rate of AEs that were considered possibly treatment-related was 16.7% in the placebo arm and 30.6% in the AG-348 arm. The most common treatment-related AEs were headache (occurring in 16.7% and 11.1% of patients, respectively), nausea (0% and 13.9%, respectively), and vomiting (0% and 5.6%, respectively).

Exposure to AG-348, as measured by area under the concentration × time curve (AUC), increased in a dose-proportional manner after a single dose. And absorption was rapid (median Tmax ranged from 0.77 to 4.07 hours), although Tmax increased and there was a less-than-proportional increase in Cmax at higher doses.

When AG-348 was administered from 30 mg to 360 mg, there was a dose-dependent decrease in blood 2,3-DPG levels over 24 hours—up to a 49% mean decrease. Increasing the dose beyond 360 mg did not result in additional decreases in 2,3-DPG levels. And levels returned to placebo levels after about 72 hours.

There were minimal increases in blood ATP levels after AG-348 treatment at any dose.

MAD study

At the time of the presentation, 2 cohorts of 8 subjects each (6 receiving AG-348 and 2 receiving placebo) had completed treatment in the MAD study. One cohort received drug or placebo at 120 mg BID, and the other received 360 mg BID.

The pharmacokinetic results for day 1 of this study were consistent with those of the SAD study. However, the Cmax and AUC0-Ʈ were lower on day 14 than day 1. Investigators said this suggests that multiple doses of AG-348 increase the rate of its own metabolism.

They also said the decrease in exposure observed on day 14 is consistent with preclinical data that suggest AG-348 is a moderate inducer of CYP3A4, which is the major route of the oxidative metabolism of AG-348.

As in the SAD study, the investigators observed decreases in 2,3-DPG blood levels after the first dose in cohorts 1 and 2—up to a 48% mean decrease from baseline for both doses. Concentrations returned to placebo levels between 48 and 72 hours after the last dose.

Unlike in the SAD study, patients in this study had increases in ATP—up to a 52% mean increase from baseline in both dosing cohorts. ATP levels remained elevated through 72 hours after the last dose.

The investigators said the results of these 2 studies have informed dose selection for the planned phase 2 study of AG-348 in PKD patients, which is expected to begin soon. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Prevalence of SDB in SCD may be high

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Germline mutations linked to ALL

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that heritable mutations in the gene ETV6 can predispose people to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Somatic mutations in ETV6 have previously been implicated in the development of ALL and other hematologic malignancies.

The new study, published in Nature Genetics, has shown that germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red blood cell (RBC) macrocytosis, and predisposition to ALL.

The research began with a family (family 1) that had autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia (67,000-132,000 platelets/μL), high RBC mean corpuscular volume (MCV, 92.5-101.5 fl), and 2 cases of B-cell-precursor ALL.

“All of them had big red blood cells, low platelet counts, and propensity to bleed,” said study author Christopher Porter, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

This familial link to abnormal blood dynamics and predisposition to ALL implied a common genetic denominator. To find it, the researchers performed whole-exome sequencing and found a heterozygous single-nucleotide change in ETV6, c.641C>T, encoding a p.Pro214Leu substitution in the central domain.

The researchers then screened 23 other families with similar phenotypes as the first and identified 2 families with ETV6 mutations.

One family (family 2) had members with platelet counts ranging from 44,000 to 115,000 platelets/μL, RBC MCVs ranging from 88 to 97 fl, and a member with ALL. All affected family members had a c.641C>T mutation identical to the one identified in family 1.

Another family (family 3) had members with platelet counts ranging from 99,000 to 101,000 platelets/μL and RBC MCVs ranging from 93 to 98 fl but no malignancies. Members of this family had a c.1252A>G transition producing a p.Arg418Gly substitution in the DNA-binding domain, with alternative splicing and exon skipping.

The researchers said these mutations partially disrupt ETV6 transcriptional repression in vitro and cause aberrant cytoplasmic localization of both mutant and endogenous ETV6, suggesting a dominant-negative effect. The mutations also impair megakaryocyte development and proplatelet formation in culture.

Dr Porter and his colleagues noted that another team of researchers recently discovered germline missense mutations in ETV6 in 3 unrelated families. Dr Porter’s group hopes future work will show the prevalence of germline mutations in ETV6.

“It’s not common in a general population, but we think it might be much more common in people who develop ALL,” Dr Porter said. “[Our] paper highlights this gene in the development of leukemia. By studying this mutation, we should be able to gather a better understanding of how leukemia develops.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that heritable mutations in the gene ETV6 can predispose people to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Somatic mutations in ETV6 have previously been implicated in the development of ALL and other hematologic malignancies.

The new study, published in Nature Genetics, has shown that germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red blood cell (RBC) macrocytosis, and predisposition to ALL.

The research began with a family (family 1) that had autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia (67,000-132,000 platelets/μL), high RBC mean corpuscular volume (MCV, 92.5-101.5 fl), and 2 cases of B-cell-precursor ALL.

“All of them had big red blood cells, low platelet counts, and propensity to bleed,” said study author Christopher Porter, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

This familial link to abnormal blood dynamics and predisposition to ALL implied a common genetic denominator. To find it, the researchers performed whole-exome sequencing and found a heterozygous single-nucleotide change in ETV6, c.641C>T, encoding a p.Pro214Leu substitution in the central domain.

The researchers then screened 23 other families with similar phenotypes as the first and identified 2 families with ETV6 mutations.

One family (family 2) had members with platelet counts ranging from 44,000 to 115,000 platelets/μL, RBC MCVs ranging from 88 to 97 fl, and a member with ALL. All affected family members had a c.641C>T mutation identical to the one identified in family 1.

Another family (family 3) had members with platelet counts ranging from 99,000 to 101,000 platelets/μL and RBC MCVs ranging from 93 to 98 fl but no malignancies. Members of this family had a c.1252A>G transition producing a p.Arg418Gly substitution in the DNA-binding domain, with alternative splicing and exon skipping.

The researchers said these mutations partially disrupt ETV6 transcriptional repression in vitro and cause aberrant cytoplasmic localization of both mutant and endogenous ETV6, suggesting a dominant-negative effect. The mutations also impair megakaryocyte development and proplatelet formation in culture.

Dr Porter and his colleagues noted that another team of researchers recently discovered germline missense mutations in ETV6 in 3 unrelated families. Dr Porter’s group hopes future work will show the prevalence of germline mutations in ETV6.

“It’s not common in a general population, but we think it might be much more common in people who develop ALL,” Dr Porter said. “[Our] paper highlights this gene in the development of leukemia. By studying this mutation, we should be able to gather a better understanding of how leukemia develops.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that heritable mutations in the gene ETV6 can predispose people to acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Somatic mutations in ETV6 have previously been implicated in the development of ALL and other hematologic malignancies.

The new study, published in Nature Genetics, has shown that germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red blood cell (RBC) macrocytosis, and predisposition to ALL.

The research began with a family (family 1) that had autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia (67,000-132,000 platelets/μL), high RBC mean corpuscular volume (MCV, 92.5-101.5 fl), and 2 cases of B-cell-precursor ALL.

“All of them had big red blood cells, low platelet counts, and propensity to bleed,” said study author Christopher Porter, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

This familial link to abnormal blood dynamics and predisposition to ALL implied a common genetic denominator. To find it, the researchers performed whole-exome sequencing and found a heterozygous single-nucleotide change in ETV6, c.641C>T, encoding a p.Pro214Leu substitution in the central domain.

The researchers then screened 23 other families with similar phenotypes as the first and identified 2 families with ETV6 mutations.

One family (family 2) had members with platelet counts ranging from 44,000 to 115,000 platelets/μL, RBC MCVs ranging from 88 to 97 fl, and a member with ALL. All affected family members had a c.641C>T mutation identical to the one identified in family 1.

Another family (family 3) had members with platelet counts ranging from 99,000 to 101,000 platelets/μL and RBC MCVs ranging from 93 to 98 fl but no malignancies. Members of this family had a c.1252A>G transition producing a p.Arg418Gly substitution in the DNA-binding domain, with alternative splicing and exon skipping.

The researchers said these mutations partially disrupt ETV6 transcriptional repression in vitro and cause aberrant cytoplasmic localization of both mutant and endogenous ETV6, suggesting a dominant-negative effect. The mutations also impair megakaryocyte development and proplatelet formation in culture.

Dr Porter and his colleagues noted that another team of researchers recently discovered germline missense mutations in ETV6 in 3 unrelated families. Dr Porter’s group hopes future work will show the prevalence of germline mutations in ETV6.

“It’s not common in a general population, but we think it might be much more common in people who develop ALL,” Dr Porter said. “[Our] paper highlights this gene in the development of leukemia. By studying this mutation, we should be able to gather a better understanding of how leukemia develops.” ![]()

Understanding the role of del(7q) in MDS

Image by James Thomson

A new study has improved researchers’ understanding of a genetic defect associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and the team hopes this will ultimately help us correct the defect in patients.

The researchers used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study del(7q), a chromosomal abnormality found in patients with MDS.

This provided the team with new insight into how the deletion contributes to MDS development.

Steven D. Nimer, MD, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

To determine how del(7q) contributes to MDS development, the researchers isolated hematopoietic cells from a patient with del(7q) and reprogrammed them into iPSCs. These iPSCs recapitulated MDS-associated phenotypes, including impaired hematopoietic differentiation.

The researchers also showed that, by engineering heterozygous chromosome 7q loss, they could recapitulate in normal iPSCs the characteristics they observed in the del(7q) iPSCs.

So the team was not surprised to find that disease phenotypes were rescued when del(7q) iPSC lines acquired a duplicate copy of chromosome 7q material.

The researchers also found that hemizygosity of chromosome 7q reduced the expression of many genes in the chromosome7q-deleted region. But gene expression was restored upon chromosome 7q dosage correction.

“[W]e were able to pinpoint a region on chromosome 7 that is critical and were able to identify candidate genes residing there that may cause this disease,” said study author Eirini Papapetrou, MD, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York.

Focusing on hits residing in this region, 7q32.3–7q36.1, the researchers found 10 genes that were enriched (by >1.5-fold) recurrently.

Further investigation confirmed that 4 of these genes—HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, LUC7L2, and EZH2—could partially rescue the emergence of CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors when overexpressed in del(7q) iPSCs.

The researchers conducted additional experiments focusing on EZH2 alone and found that haploinsufficiency of EZH2 decreases cells’ hematopoietic potential.

But it seems the hematopoietic defects caused by chromosome 7q hemizygosity are mediated through the haploinsufficiency of EZH2 in combination with 1 or more additional genes, which might include LUC7L2, HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, and/or other genes. ![]()

Image by James Thomson

A new study has improved researchers’ understanding of a genetic defect associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and the team hopes this will ultimately help us correct the defect in patients.

The researchers used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study del(7q), a chromosomal abnormality found in patients with MDS.

This provided the team with new insight into how the deletion contributes to MDS development.

Steven D. Nimer, MD, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

To determine how del(7q) contributes to MDS development, the researchers isolated hematopoietic cells from a patient with del(7q) and reprogrammed them into iPSCs. These iPSCs recapitulated MDS-associated phenotypes, including impaired hematopoietic differentiation.

The researchers also showed that, by engineering heterozygous chromosome 7q loss, they could recapitulate in normal iPSCs the characteristics they observed in the del(7q) iPSCs.

So the team was not surprised to find that disease phenotypes were rescued when del(7q) iPSC lines acquired a duplicate copy of chromosome 7q material.

The researchers also found that hemizygosity of chromosome 7q reduced the expression of many genes in the chromosome7q-deleted region. But gene expression was restored upon chromosome 7q dosage correction.

“[W]e were able to pinpoint a region on chromosome 7 that is critical and were able to identify candidate genes residing there that may cause this disease,” said study author Eirini Papapetrou, MD, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York.

Focusing on hits residing in this region, 7q32.3–7q36.1, the researchers found 10 genes that were enriched (by >1.5-fold) recurrently.

Further investigation confirmed that 4 of these genes—HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, LUC7L2, and EZH2—could partially rescue the emergence of CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors when overexpressed in del(7q) iPSCs.

The researchers conducted additional experiments focusing on EZH2 alone and found that haploinsufficiency of EZH2 decreases cells’ hematopoietic potential.

But it seems the hematopoietic defects caused by chromosome 7q hemizygosity are mediated through the haploinsufficiency of EZH2 in combination with 1 or more additional genes, which might include LUC7L2, HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, and/or other genes. ![]()

Image by James Thomson

A new study has improved researchers’ understanding of a genetic defect associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and the team hopes this will ultimately help us correct the defect in patients.

The researchers used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study del(7q), a chromosomal abnormality found in patients with MDS.

This provided the team with new insight into how the deletion contributes to MDS development.

Steven D. Nimer, MD, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

To determine how del(7q) contributes to MDS development, the researchers isolated hematopoietic cells from a patient with del(7q) and reprogrammed them into iPSCs. These iPSCs recapitulated MDS-associated phenotypes, including impaired hematopoietic differentiation.

The researchers also showed that, by engineering heterozygous chromosome 7q loss, they could recapitulate in normal iPSCs the characteristics they observed in the del(7q) iPSCs.

So the team was not surprised to find that disease phenotypes were rescued when del(7q) iPSC lines acquired a duplicate copy of chromosome 7q material.

The researchers also found that hemizygosity of chromosome 7q reduced the expression of many genes in the chromosome7q-deleted region. But gene expression was restored upon chromosome 7q dosage correction.

“[W]e were able to pinpoint a region on chromosome 7 that is critical and were able to identify candidate genes residing there that may cause this disease,” said study author Eirini Papapetrou, MD, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York.

Focusing on hits residing in this region, 7q32.3–7q36.1, the researchers found 10 genes that were enriched (by >1.5-fold) recurrently.

Further investigation confirmed that 4 of these genes—HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, LUC7L2, and EZH2—could partially rescue the emergence of CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors when overexpressed in del(7q) iPSCs.

The researchers conducted additional experiments focusing on EZH2 alone and found that haploinsufficiency of EZH2 decreases cells’ hematopoietic potential.

But it seems the hematopoietic defects caused by chromosome 7q hemizygosity are mediated through the haploinsufficiency of EZH2 in combination with 1 or more additional genes, which might include LUC7L2, HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, and/or other genes. ![]()

Enzyme keeps HSCs functional to prevent anemia

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests an enzyme found in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is key to maintaining periods of inactivity, thereby decreasing the odds that HSCs will divide too often and acquire mutations or cell damage.

Experiments showed that animals lacking this enzyme, inositol trisphosphate 3-kinase B (Itpkb), experience dangerous HSC activation and ultimately succumb to lethal anemia.

“These HSCs remain active too long and then disappear,” said Karsten Sauer, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“As a consequence, the mice lose their red blood cells and die.”

With this new understanding of Itpkb, Dr Sauer and his colleagues believe they are closer to improving therapies for diseases such as bone marrow failure syndrome, anemia, leukemia, and lymphoma.

The team described their research in Blood.

The group set out to investigate the mechanisms that activate and deactivate HSCs. They focused on Itpkb because it is produced in HSCs, and the enzyme is known to dampen activating signaling in other cells.

“We hypothesized that Itpkb might do the same in HSCs to keep them at rest,” Dr Sauer said. “Moreover, Itpkb is an enzyme whose function can be controlled by small molecules. This might facilitate drug development if our hypothesis were true.”

The researchers started with a strain of mice that lacked the gene to produce Itpkb. As expected, these mice developed hyperactive HSCs. Eventually, the mutant HSCs exhausted themselves and stopped producing progenitor cells, so the mice developed severe anemia and died.

Dr Sauer and his colleagues linked the abnormal behavior of the mutant HSCs to a chain of events at the molecular level.

Itpkb’s job is to attach phosphates to molecules called inositols, which then send messages to other parts of the cell. The researchers found that Itpkb can turn one inositol, IP3, into another inositol known as IP4.

This is significant because IP4 controls cell proliferation, cellular metabolism, and aspects of the immune system. The study showed that IP4 also protects HSCs by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

To confirm this finding, the researchers treated the animals with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. The drug halted the abnormal signaling process and prevented the excessive division of HSCs lacking Itpkb. This supported the notion that Itpkb maintains HSCs’ quiescence by dampening PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling.

Dr Sauer said future research in his lab will focus on studying whether Itpkb has a similar function in human HSCs.

“A major question is whether we can translate our findings into innovative therapies,” he said. “If we can show that Itpkb also keeps human HSCs healthy, this could open avenues to target Itpkb to improve HSC function in bone marrow failure syndromes and immunodeficiencies or to increase the success rates of HSC transplantation therapies for leukemias and lymphomas.” ![]()

Predicting pregnancy complications in SCD patients

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded. ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a new analysis may help physicians predict the likelihood of complications in pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The research showed that pregnant women with SCD had an increased risk of stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, having infants who were born small for their gestational age, and other adverse outcomes.

Women with severe SCD, but not those with milder SCD, had a substantially higher risk of mortality than their healthy peers.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“While we know that women with sickle cell disease will have high-risk pregnancies, we have lacked the evidence that would allow us to confidently tell these patients how likely they are to experience one complication over another,” said study author Eugene Oteng-Ntim, MD, of the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, England.

“This reality makes it difficult for us as care providers to properly counsel our sickle cell patients considering pregnancy.”

To better estimate pregnancy-related complications in women with SCD, Dr Oteng-Ntim and his colleagues examined 21 published observational studies.

The team analyzed data on 26,349 pregnant women with SCD and 26,151,746 pregnant women who shared attributes with the SCD population, such as ethnicity or location, but were otherwise healthy.

The researchers classified the SCD population based on genotype, including 1276 women with the classic form (HbSS genotype), 279 with a milder form (HbSC genotype), and 24,794 whose disease genotype was unreported (non-specified SCD).

Thirteen of the studies originated from high-income countries ($30,000 income per capita or greater), and the remaining were from low- to median-income countries.

Compared to women without SCD, patients with HbSS genotype had an increased risk of death, with a risk ratio (RR) of 5.98. Women with non-specified SCD had an increased risk of death as well, with an RR of 18.51. There was only 1 death among women who were known to have HbSC SCD.

There was an increased risk of stillbirth among women with SCD, compared to those without the disease. The RRs were 3.94 for HbSS disease, 1.78 for HbSC disease, and 3.49 for non-specified SCD.

The researchers found a significantly lower risk of maternal mortality (odds ratio [OR]=0.15) and stillbirth (OR=0.28) in SCD patients from countries with a gross national income of $30,000 or greater. But income had no significant impact on pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, or infants being small for their gestational age.

Women with all types of SCD had an increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, compared to healthy women. The RRs were 2.43 for HbSS disease, 2.03 for HbSC disease, and 2.06 for non-specified SCD.

Women with SCD also had an increased risk of preterm delivery. The RRs were 2.21 for HbSS disease, 1.45 for HbSC disease, and 1.59 for non-specified SCD.

And women with SCD were more likely to have infants who were born small for their gestational age. The RRs were 3.72 for HbSS disease, 1.98 for HbSC disease, and 2.23 for non-specified SCD.

Analyses revealed that genotype (HbSS vs HbSC) had a significant impact on stillbirth, preterm delivery, and small infants, but it did not appear to impact the risk of pre-eclampsia.

The researchers said this study provides useful estimates of the morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in pregnancy.

“By improving care providers’ ability to more accurately predict adverse outcomes, this analysis is a first step toward improving universal care for all who suffer from this disease,” Dr Oteng-Ntim concluded.

Team advocates liver MRI to measure iron

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be the gold standard for measuring liver iron concentration (LIC) in patients receiving ongoing transfusion therapy, according to a group of researchers.

The team found evidence suggesting that liver MRI is more accurate than liver biopsy in determining total body iron balance in patients with sickle cell disease and other disorders requiring regular blood transfusions.

The findings have been published in Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

“Measuring total body iron using MRI is safer and less painful than biopsy,” said study author John Wood, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“In this study, we’ve demonstrated that it is also more accurate. MRI should be recognized as the new gold standard for determining iron accumulation in the body.”

Dr Wood and his colleagues came to this conclusion after analyzing data from 49 patients who were undergoing treatment with deferitazole, an experimental chelating agent.

The team looked at the amount of iron the patients were receiving by transfusion and the amount of chelating agent they consumed, providing insights into the expected changes in iron levels at 12, 24, and 48 weeks after the start of deferitazole.

To compare MRI and liver biopsy, the researchers used serial estimates of iron chelation efficiency (ICE) calculated by R2 and R2* MRI LIC estimates as well as by simulated liver biopsy (over all physically reasonable sampling variability).

The estimates suggested that MRI liver iron measurements (R2 and R2*) are more accurate than a physically realizable liver biopsy (which has a sampling error of 10% or higher).