User login

ZFNs can correct sickle cell mutation

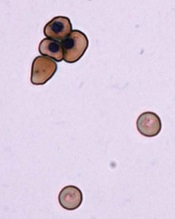

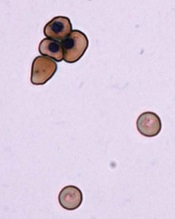

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

Gene editing via zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) shows early promise for treating sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

Investigators used ZFNs to correct the SCD mutation in CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients.

And these modified cells were able to produce normal red blood cells in vitro.

“This is a very exciting result,” said study author Donald Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“It suggests the future direction for treating genetic diseases will be by correcting the specific mutation in a patient’s genetic code.”

For this research, Dr Kohn and his colleagues took ZFNs designed to flank the SCD mutation and delivered them with a homologous donor template (either an integrase-defective lentiviral vector [IDLV] or a DNA oligonucleotide).

The investigators first tested this gene-editing system in CD34+ HSPCs derived from healthy donors and observed “high levels” of gene modification at the beta-globin locus. They also discovered off-target cleavage in the delta-globin gene but noted that this gene is “functionally dispensable.”

Additional experiments revealed that the modified CD34+ HSPCs could differentiate into erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cell types in vitro and in NSG mice.

So the investigators tested ZFN messenger RNA and the IDLV donor in CD34+ cells derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients. The team cultured cells in erythroid expansion medium and, after expansion but before enucleation, harvested the cells.

Genomic analysis revealed correction of the SCD mutation in 18.4±6.7% of the reads, and with that came the production of wild-type hemoglobin.

The investigators said these results show that ZFNs can provide site-specific gene correction and lay the groundwork for a potential therapy to treat SCD. The next steps will be to make the gene correction process more efficient and conduct additional research to determine if the method is effective and safe enough to move to clinical trials.

“This is a promising first step in showing that gene correction has the potential to help patients with sickle cell disease,” said Megan Hoban, a graduate student at UCLA. “The study data provide the foundational evidence that the method is viable.”

Another research group has reported similarly promising early results using induced pluripotent stem cells and CRISPR/Cas9 to correct the SCD mutation. ![]()

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

Gene editing via zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) shows early promise for treating sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

Investigators used ZFNs to correct the SCD mutation in CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients.

And these modified cells were able to produce normal red blood cells in vitro.

“This is a very exciting result,” said study author Donald Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“It suggests the future direction for treating genetic diseases will be by correcting the specific mutation in a patient’s genetic code.”

For this research, Dr Kohn and his colleagues took ZFNs designed to flank the SCD mutation and delivered them with a homologous donor template (either an integrase-defective lentiviral vector [IDLV] or a DNA oligonucleotide).

The investigators first tested this gene-editing system in CD34+ HSPCs derived from healthy donors and observed “high levels” of gene modification at the beta-globin locus. They also discovered off-target cleavage in the delta-globin gene but noted that this gene is “functionally dispensable.”

Additional experiments revealed that the modified CD34+ HSPCs could differentiate into erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cell types in vitro and in NSG mice.

So the investigators tested ZFN messenger RNA and the IDLV donor in CD34+ cells derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients. The team cultured cells in erythroid expansion medium and, after expansion but before enucleation, harvested the cells.

Genomic analysis revealed correction of the SCD mutation in 18.4±6.7% of the reads, and with that came the production of wild-type hemoglobin.

The investigators said these results show that ZFNs can provide site-specific gene correction and lay the groundwork for a potential therapy to treat SCD. The next steps will be to make the gene correction process more efficient and conduct additional research to determine if the method is effective and safe enough to move to clinical trials.

“This is a promising first step in showing that gene correction has the potential to help patients with sickle cell disease,” said Megan Hoban, a graduate student at UCLA. “The study data provide the foundational evidence that the method is viable.”

Another research group has reported similarly promising early results using induced pluripotent stem cells and CRISPR/Cas9 to correct the SCD mutation. ![]()

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

Gene editing via zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) shows early promise for treating sickle cell disease (SCD), according to preclinical research published in Blood.

Investigators used ZFNs to correct the SCD mutation in CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients.

And these modified cells were able to produce normal red blood cells in vitro.

“This is a very exciting result,” said study author Donald Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“It suggests the future direction for treating genetic diseases will be by correcting the specific mutation in a patient’s genetic code.”

For this research, Dr Kohn and his colleagues took ZFNs designed to flank the SCD mutation and delivered them with a homologous donor template (either an integrase-defective lentiviral vector [IDLV] or a DNA oligonucleotide).

The investigators first tested this gene-editing system in CD34+ HSPCs derived from healthy donors and observed “high levels” of gene modification at the beta-globin locus. They also discovered off-target cleavage in the delta-globin gene but noted that this gene is “functionally dispensable.”

Additional experiments revealed that the modified CD34+ HSPCs could differentiate into erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cell types in vitro and in NSG mice.

So the investigators tested ZFN messenger RNA and the IDLV donor in CD34+ cells derived from the bone marrow of SCD patients. The team cultured cells in erythroid expansion medium and, after expansion but before enucleation, harvested the cells.

Genomic analysis revealed correction of the SCD mutation in 18.4±6.7% of the reads, and with that came the production of wild-type hemoglobin.

The investigators said these results show that ZFNs can provide site-specific gene correction and lay the groundwork for a potential therapy to treat SCD. The next steps will be to make the gene correction process more efficient and conduct additional research to determine if the method is effective and safe enough to move to clinical trials.

“This is a promising first step in showing that gene correction has the potential to help patients with sickle cell disease,” said Megan Hoban, a graduate student at UCLA. “The study data provide the foundational evidence that the method is viable.”

Another research group has reported similarly promising early results using induced pluripotent stem cells and CRISPR/Cas9 to correct the SCD mutation. ![]()

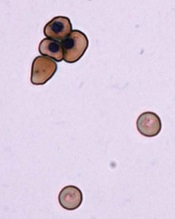

Researchers generate RBCs to treat SCD

Image by Ying Wang–

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Researchers say they have devised a technique for generating normal, mature red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team hopes that, ultimately, the RBCs could be transfused back into the patients from which they are derived and eliminate the need for donor transfusion in SCD.

Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues described the technique in Stem Cells.

Dr Cheng noted that SCD patients often require RBC transfusions, but over time, their bodies may begin to mount an immune response against the foreign blood.

“Their bodies quickly kill off the blood cells,” Dr Cheng said. “So they have to get transfusions more and more frequently.”

A solution, Dr Cheng and his colleagues thought, would be to generate RBCs for transfusion using a patient’s own cells.

To do this, the researchers first took hematopoietic cells from an SCD patient and generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Then, the team used the gene-editing technique CRISPR/Cas9 to target the homozygous SCD mutation (nt. 69A>T) in the HBB gene and ensure the RBCs they generated would not be sickled.

Finally, they coaxed the iPSCs into mature RBCs that expressed the corrected HBB gene. The edited iPSCs generated RBCs just as efficiently as iPSCs that hadn’t been subjected to CRISPR/Cas9.

And the level of HBB protein expression in the RBCs derived from edited iPSCs was similar to that of RBCs generated from unedited iPSCs.

Dr Cheng noted that, to become medically useful, this method will have to be made more efficient and scaled up significantly. And the cells would need to be tested for safety.

“[Nevertheless,] this study shows it may be possible in the not-too-distant future to provide patients with sickle cell disease with an exciting new treatment option,” Dr Cheng said.

He and his colleagues believe this method of RBC generation may also be applicable for other blood disorders. And they think it might be possible to edit cells from healthy individuals so they can resist malaria and other infectious agents.

Another research group has reported the ability to correct the SCD mutation using zinc-finger nucleases. ![]()

Image by Ying Wang–

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Researchers say they have devised a technique for generating normal, mature red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team hopes that, ultimately, the RBCs could be transfused back into the patients from which they are derived and eliminate the need for donor transfusion in SCD.

Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues described the technique in Stem Cells.

Dr Cheng noted that SCD patients often require RBC transfusions, but over time, their bodies may begin to mount an immune response against the foreign blood.

“Their bodies quickly kill off the blood cells,” Dr Cheng said. “So they have to get transfusions more and more frequently.”

A solution, Dr Cheng and his colleagues thought, would be to generate RBCs for transfusion using a patient’s own cells.

To do this, the researchers first took hematopoietic cells from an SCD patient and generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Then, the team used the gene-editing technique CRISPR/Cas9 to target the homozygous SCD mutation (nt. 69A>T) in the HBB gene and ensure the RBCs they generated would not be sickled.

Finally, they coaxed the iPSCs into mature RBCs that expressed the corrected HBB gene. The edited iPSCs generated RBCs just as efficiently as iPSCs that hadn’t been subjected to CRISPR/Cas9.

And the level of HBB protein expression in the RBCs derived from edited iPSCs was similar to that of RBCs generated from unedited iPSCs.

Dr Cheng noted that, to become medically useful, this method will have to be made more efficient and scaled up significantly. And the cells would need to be tested for safety.

“[Nevertheless,] this study shows it may be possible in the not-too-distant future to provide patients with sickle cell disease with an exciting new treatment option,” Dr Cheng said.

He and his colleagues believe this method of RBC generation may also be applicable for other blood disorders. And they think it might be possible to edit cells from healthy individuals so they can resist malaria and other infectious agents.

Another research group has reported the ability to correct the SCD mutation using zinc-finger nucleases. ![]()

Image by Ying Wang–

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Researchers say they have devised a technique for generating normal, mature red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team hopes that, ultimately, the RBCs could be transfused back into the patients from which they are derived and eliminate the need for donor transfusion in SCD.

Linzhao Cheng, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues described the technique in Stem Cells.

Dr Cheng noted that SCD patients often require RBC transfusions, but over time, their bodies may begin to mount an immune response against the foreign blood.

“Their bodies quickly kill off the blood cells,” Dr Cheng said. “So they have to get transfusions more and more frequently.”

A solution, Dr Cheng and his colleagues thought, would be to generate RBCs for transfusion using a patient’s own cells.

To do this, the researchers first took hematopoietic cells from an SCD patient and generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Then, the team used the gene-editing technique CRISPR/Cas9 to target the homozygous SCD mutation (nt. 69A>T) in the HBB gene and ensure the RBCs they generated would not be sickled.

Finally, they coaxed the iPSCs into mature RBCs that expressed the corrected HBB gene. The edited iPSCs generated RBCs just as efficiently as iPSCs that hadn’t been subjected to CRISPR/Cas9.

And the level of HBB protein expression in the RBCs derived from edited iPSCs was similar to that of RBCs generated from unedited iPSCs.

Dr Cheng noted that, to become medically useful, this method will have to be made more efficient and scaled up significantly. And the cells would need to be tested for safety.

“[Nevertheless,] this study shows it may be possible in the not-too-distant future to provide patients with sickle cell disease with an exciting new treatment option,” Dr Cheng said.

He and his colleagues believe this method of RBC generation may also be applicable for other blood disorders. And they think it might be possible to edit cells from healthy individuals so they can resist malaria and other infectious agents.

Another research group has reported the ability to correct the SCD mutation using zinc-finger nucleases. ![]()

ASH advocates use of systems-based hematologists

Photo courtesy of CDC

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) has released a report proposing a new role for hematologists specializing in non-malignant blood disorders.

ASH partnered with the healthcare consulting firm The Lewin Group to identify emerging career opportunities for health system- and hospital-based hematologists and to provide guidance on pursuing those opportunities.

The resulting report, published in Blood, outlines a few models for a systems-based clinical hematologist.

The report’s authors noted that demand for hematology expertise remains high nationwide. However, ASH and its members are concerned that changes to academic training will hinder both the recruitment of new talent to the field and the retention of seasoned experts.

The authors said that today’s hematology trainees are unlikely to receive the same non-malignant training as many “classic” hematologists trained in prior decades. And training shortfalls are further compounded by the fact that primary care physicians do not have the expertise to manage common blood disorders, which increases referrals to hematologists.

This results in higher demand for a smaller pool of hematologists entering the field with adequate training to effectively and efficiently manage non-malignant disorders.

“Given the rapid evolution and complexity of the field, the time is appropriate to identify career pathways that attract and enable physicians to practice non-malignant hematology in a sustainable manner,” said author Janis L. Abkowitz, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

She and her colleagues noted that, in response to these challenges, US hematologists are defining new paths and assuming more centralized positions in large and small healthcare systems.

These systems-based hematologists are specialty-trained physicians—employed by a hospital, medical center, or health system—who optimize individual patient care as well as the overall system of healthcare delivery for patients with blood disorders.

For example, a systems-based hematologist could work closely with surgeons to minimize perioperative bleeding and could manage care pathways for patients with chronic blood diseases.

The report offered 4 examples where the involvement of a systems-based hematologist would lead to cost-effective decision-making. These were based upon interviews with 14 early adoptors of the systems-based approach to hematology.

The first example was heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). A systems-based hematologist could implement care pathways that focus on HIT by working to reduce unnecessary heparin exposure, optimizing laboratory testing for suspected HIT, and reducing unnecessary procedures in patients.

The second example was thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). A systems-based hematologist could optimize testing for TTP, which may reduce system-wide plasma use.

The third example was a medical director for hemostasis and thrombosis. A systems-based hematologist could foster appropriate and safe practices, including the implementation of and adherence to preventive care for thrombotic events and the optimal use of anticoagulant medications.

The fourth example was non-malignant hematology consultation in an accountable care organization (ACO) environment. The authors noted that ACOs have enabled more patients to be served by a health system, but there are fewer incentives for physicians to manage common hematology-related issues. A funded systems-based hematologist could ensure that patients have more timely access to hematology consultations.

“A systems-based hematologist position presents a unique opportunity for hematologists to design new models for care delivery and demonstrate their ability to improve clinical outcomes while maintaining or reducing costs,” Dr Abkowitz said. “Just as blood must flow throughout the body, the expertise of hematology must flow throughout the healthcare system.”

As a next step, ASH has invited its members to share practice models they have developed and examples of how they have collaborated with others to improve healthcare outcomes, reduce complications, and eliminate unnecessary spending. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) has released a report proposing a new role for hematologists specializing in non-malignant blood disorders.

ASH partnered with the healthcare consulting firm The Lewin Group to identify emerging career opportunities for health system- and hospital-based hematologists and to provide guidance on pursuing those opportunities.

The resulting report, published in Blood, outlines a few models for a systems-based clinical hematologist.

The report’s authors noted that demand for hematology expertise remains high nationwide. However, ASH and its members are concerned that changes to academic training will hinder both the recruitment of new talent to the field and the retention of seasoned experts.

The authors said that today’s hematology trainees are unlikely to receive the same non-malignant training as many “classic” hematologists trained in prior decades. And training shortfalls are further compounded by the fact that primary care physicians do not have the expertise to manage common blood disorders, which increases referrals to hematologists.

This results in higher demand for a smaller pool of hematologists entering the field with adequate training to effectively and efficiently manage non-malignant disorders.

“Given the rapid evolution and complexity of the field, the time is appropriate to identify career pathways that attract and enable physicians to practice non-malignant hematology in a sustainable manner,” said author Janis L. Abkowitz, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

She and her colleagues noted that, in response to these challenges, US hematologists are defining new paths and assuming more centralized positions in large and small healthcare systems.

These systems-based hematologists are specialty-trained physicians—employed by a hospital, medical center, or health system—who optimize individual patient care as well as the overall system of healthcare delivery for patients with blood disorders.

For example, a systems-based hematologist could work closely with surgeons to minimize perioperative bleeding and could manage care pathways for patients with chronic blood diseases.

The report offered 4 examples where the involvement of a systems-based hematologist would lead to cost-effective decision-making. These were based upon interviews with 14 early adoptors of the systems-based approach to hematology.

The first example was heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). A systems-based hematologist could implement care pathways that focus on HIT by working to reduce unnecessary heparin exposure, optimizing laboratory testing for suspected HIT, and reducing unnecessary procedures in patients.

The second example was thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). A systems-based hematologist could optimize testing for TTP, which may reduce system-wide plasma use.

The third example was a medical director for hemostasis and thrombosis. A systems-based hematologist could foster appropriate and safe practices, including the implementation of and adherence to preventive care for thrombotic events and the optimal use of anticoagulant medications.

The fourth example was non-malignant hematology consultation in an accountable care organization (ACO) environment. The authors noted that ACOs have enabled more patients to be served by a health system, but there are fewer incentives for physicians to manage common hematology-related issues. A funded systems-based hematologist could ensure that patients have more timely access to hematology consultations.

“A systems-based hematologist position presents a unique opportunity for hematologists to design new models for care delivery and demonstrate their ability to improve clinical outcomes while maintaining or reducing costs,” Dr Abkowitz said. “Just as blood must flow throughout the body, the expertise of hematology must flow throughout the healthcare system.”

As a next step, ASH has invited its members to share practice models they have developed and examples of how they have collaborated with others to improve healthcare outcomes, reduce complications, and eliminate unnecessary spending. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) has released a report proposing a new role for hematologists specializing in non-malignant blood disorders.

ASH partnered with the healthcare consulting firm The Lewin Group to identify emerging career opportunities for health system- and hospital-based hematologists and to provide guidance on pursuing those opportunities.

The resulting report, published in Blood, outlines a few models for a systems-based clinical hematologist.

The report’s authors noted that demand for hematology expertise remains high nationwide. However, ASH and its members are concerned that changes to academic training will hinder both the recruitment of new talent to the field and the retention of seasoned experts.

The authors said that today’s hematology trainees are unlikely to receive the same non-malignant training as many “classic” hematologists trained in prior decades. And training shortfalls are further compounded by the fact that primary care physicians do not have the expertise to manage common blood disorders, which increases referrals to hematologists.

This results in higher demand for a smaller pool of hematologists entering the field with adequate training to effectively and efficiently manage non-malignant disorders.

“Given the rapid evolution and complexity of the field, the time is appropriate to identify career pathways that attract and enable physicians to practice non-malignant hematology in a sustainable manner,” said author Janis L. Abkowitz, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

She and her colleagues noted that, in response to these challenges, US hematologists are defining new paths and assuming more centralized positions in large and small healthcare systems.

These systems-based hematologists are specialty-trained physicians—employed by a hospital, medical center, or health system—who optimize individual patient care as well as the overall system of healthcare delivery for patients with blood disorders.

For example, a systems-based hematologist could work closely with surgeons to minimize perioperative bleeding and could manage care pathways for patients with chronic blood diseases.

The report offered 4 examples where the involvement of a systems-based hematologist would lead to cost-effective decision-making. These were based upon interviews with 14 early adoptors of the systems-based approach to hematology.

The first example was heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). A systems-based hematologist could implement care pathways that focus on HIT by working to reduce unnecessary heparin exposure, optimizing laboratory testing for suspected HIT, and reducing unnecessary procedures in patients.

The second example was thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). A systems-based hematologist could optimize testing for TTP, which may reduce system-wide plasma use.

The third example was a medical director for hemostasis and thrombosis. A systems-based hematologist could foster appropriate and safe practices, including the implementation of and adherence to preventive care for thrombotic events and the optimal use of anticoagulant medications.

The fourth example was non-malignant hematology consultation in an accountable care organization (ACO) environment. The authors noted that ACOs have enabled more patients to be served by a health system, but there are fewer incentives for physicians to manage common hematology-related issues. A funded systems-based hematologist could ensure that patients have more timely access to hematology consultations.

“A systems-based hematologist position presents a unique opportunity for hematologists to design new models for care delivery and demonstrate their ability to improve clinical outcomes while maintaining or reducing costs,” Dr Abkowitz said. “Just as blood must flow throughout the body, the expertise of hematology must flow throughout the healthcare system.”

As a next step, ASH has invited its members to share practice models they have developed and examples of how they have collaborated with others to improve healthcare outcomes, reduce complications, and eliminate unnecessary spending. ![]()

FDA approves first biosimilar product

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), the first biosimilar product to be approved in the US.

A biosimilar product is approved based on data showing that it is highly similar to an already-approved biological product.

Sandoz Inc’s Zarxio is biosimilar to Amgen Inc’s Neupogen (filgrastim), which was originally licensed in 1991. Zarxio is now approved for the same indications as Neupogen.

Zarxio can be prescribed for:

- patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy

- patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy

- patients with cancer undergoing bone marrow transplant

- patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection and therapy

- patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

Zarxio is marketed as Zarzio outside the US. The biosimilar is available in more than 60 countries worldwide.

“Biosimilars will provide access to important therapies for patients who need them,” said FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg, MD.

“Patients and the healthcare community can be confident that biosimilar products approved by the FDA meet the agency’s rigorous safety, efficacy, and quality standards.”

Zarxio data

The FDA’s approval of Zarxio is based on a review of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, in vivo data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data that demonstrates Zarxio is biosimilar to Neupogen.

The PIONEER study was the final piece of data the FDA used to approve Zarxio as biosimilar to Neupogen. The data was sufficient to allow extrapolation of the use of Zarxio to all indications of Neupogen.

In the PIONEER study, Zarxio and Neupogen both produced the expected reduction in the duration of severe neutropenia in cancer patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy—1.17 and 1.20 days, respectively.

The mean time to absolute neutrophil count recovery in cycle 1 was also similar—1.8 ± 0.97 days in the Zarxio arm and 1.7 ± 0.81 days in the Neupogen arm. No immunogenicity or antibodies against rhG-CSF were detected throughout the study.

The most common side effects of Zarxio are aching in the bones or muscles and redness, swelling, or itching at the injection site. Serious side effects may include spleen rupture; serious allergic reactions that may cause rash, shortness of breath, wheezing and/or swelling around the mouth and eyes; fast pulse and sweating; and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

About biosimilar approval

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act) was passed as part of the Affordable Care Act that President Barack Obama signed into law in March 2010. The BPCI Act created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products shown to be “biosimilar” to or “interchangeable” with an FDA-licensed biological product, known as the reference product.

This abbreviated licensure pathway under section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act permits reliance on certain existing scientific knowledge about the safety and effectiveness of the reference product, and it enables a biosimilar biological product to be licensed based on less than a full complement of product-specific preclinical and clinical data.

A biosimilar product can only be approved by the FDA if it has the same mechanism(s) of action, route(s) of administration, dosage form(s) and strength(s) as the reference product, and only for the indication(s) and condition(s) of use that have been approved for the reference product. The facilities where biosimilars are manufactured must also meet the FDA’s standards.

There must be no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product in terms of safety and effectiveness. Only minor differences in clinically inactive components are allowable.

Zarxio has been approved as a biosimilar, not an interchangeable product. Under the BPCI Act, a biological product that has been approved as “interchangeable” may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the healthcare provider who prescribed the reference product.

For Zarxio’s approval, the FDA has designated a placeholder nonproprietary name for this product as “filgrastim-sndz.” The provision of a placeholder nonproprietary name should not be viewed as reflective of the agency’s decision on a comprehensive naming policy for biosimilars and other biological products.

While the FDA has not yet issued draft guidance on how current and future biological products marketed in the US should be named, the agency intends to do so in the near future.

For more details on Zarxio, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), the first biosimilar product to be approved in the US.

A biosimilar product is approved based on data showing that it is highly similar to an already-approved biological product.

Sandoz Inc’s Zarxio is biosimilar to Amgen Inc’s Neupogen (filgrastim), which was originally licensed in 1991. Zarxio is now approved for the same indications as Neupogen.

Zarxio can be prescribed for:

- patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy

- patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy

- patients with cancer undergoing bone marrow transplant

- patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection and therapy

- patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

Zarxio is marketed as Zarzio outside the US. The biosimilar is available in more than 60 countries worldwide.

“Biosimilars will provide access to important therapies for patients who need them,” said FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg, MD.

“Patients and the healthcare community can be confident that biosimilar products approved by the FDA meet the agency’s rigorous safety, efficacy, and quality standards.”

Zarxio data

The FDA’s approval of Zarxio is based on a review of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, in vivo data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data that demonstrates Zarxio is biosimilar to Neupogen.

The PIONEER study was the final piece of data the FDA used to approve Zarxio as biosimilar to Neupogen. The data was sufficient to allow extrapolation of the use of Zarxio to all indications of Neupogen.

In the PIONEER study, Zarxio and Neupogen both produced the expected reduction in the duration of severe neutropenia in cancer patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy—1.17 and 1.20 days, respectively.

The mean time to absolute neutrophil count recovery in cycle 1 was also similar—1.8 ± 0.97 days in the Zarxio arm and 1.7 ± 0.81 days in the Neupogen arm. No immunogenicity or antibodies against rhG-CSF were detected throughout the study.

The most common side effects of Zarxio are aching in the bones or muscles and redness, swelling, or itching at the injection site. Serious side effects may include spleen rupture; serious allergic reactions that may cause rash, shortness of breath, wheezing and/or swelling around the mouth and eyes; fast pulse and sweating; and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

About biosimilar approval

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act) was passed as part of the Affordable Care Act that President Barack Obama signed into law in March 2010. The BPCI Act created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products shown to be “biosimilar” to or “interchangeable” with an FDA-licensed biological product, known as the reference product.

This abbreviated licensure pathway under section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act permits reliance on certain existing scientific knowledge about the safety and effectiveness of the reference product, and it enables a biosimilar biological product to be licensed based on less than a full complement of product-specific preclinical and clinical data.

A biosimilar product can only be approved by the FDA if it has the same mechanism(s) of action, route(s) of administration, dosage form(s) and strength(s) as the reference product, and only for the indication(s) and condition(s) of use that have been approved for the reference product. The facilities where biosimilars are manufactured must also meet the FDA’s standards.

There must be no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product in terms of safety and effectiveness. Only minor differences in clinically inactive components are allowable.

Zarxio has been approved as a biosimilar, not an interchangeable product. Under the BPCI Act, a biological product that has been approved as “interchangeable” may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the healthcare provider who prescribed the reference product.

For Zarxio’s approval, the FDA has designated a placeholder nonproprietary name for this product as “filgrastim-sndz.” The provision of a placeholder nonproprietary name should not be viewed as reflective of the agency’s decision on a comprehensive naming policy for biosimilars and other biological products.

While the FDA has not yet issued draft guidance on how current and future biological products marketed in the US should be named, the agency intends to do so in the near future.

For more details on Zarxio, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), the first biosimilar product to be approved in the US.

A biosimilar product is approved based on data showing that it is highly similar to an already-approved biological product.

Sandoz Inc’s Zarxio is biosimilar to Amgen Inc’s Neupogen (filgrastim), which was originally licensed in 1991. Zarxio is now approved for the same indications as Neupogen.

Zarxio can be prescribed for:

- patients with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy

- patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy

- patients with cancer undergoing bone marrow transplant

- patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection and therapy

- patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

Zarxio is marketed as Zarzio outside the US. The biosimilar is available in more than 60 countries worldwide.

“Biosimilars will provide access to important therapies for patients who need them,” said FDA Commissioner Margaret A. Hamburg, MD.

“Patients and the healthcare community can be confident that biosimilar products approved by the FDA meet the agency’s rigorous safety, efficacy, and quality standards.”

Zarxio data

The FDA’s approval of Zarxio is based on a review of evidence that included structural and functional characterization, in vivo data, human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data, clinical immunogenicity data, and other clinical safety and effectiveness data that demonstrates Zarxio is biosimilar to Neupogen.

The PIONEER study was the final piece of data the FDA used to approve Zarxio as biosimilar to Neupogen. The data was sufficient to allow extrapolation of the use of Zarxio to all indications of Neupogen.

In the PIONEER study, Zarxio and Neupogen both produced the expected reduction in the duration of severe neutropenia in cancer patients undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy—1.17 and 1.20 days, respectively.

The mean time to absolute neutrophil count recovery in cycle 1 was also similar—1.8 ± 0.97 days in the Zarxio arm and 1.7 ± 0.81 days in the Neupogen arm. No immunogenicity or antibodies against rhG-CSF were detected throughout the study.

The most common side effects of Zarxio are aching in the bones or muscles and redness, swelling, or itching at the injection site. Serious side effects may include spleen rupture; serious allergic reactions that may cause rash, shortness of breath, wheezing and/or swelling around the mouth and eyes; fast pulse and sweating; and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

About biosimilar approval

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act) was passed as part of the Affordable Care Act that President Barack Obama signed into law in March 2010. The BPCI Act created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products shown to be “biosimilar” to or “interchangeable” with an FDA-licensed biological product, known as the reference product.

This abbreviated licensure pathway under section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act permits reliance on certain existing scientific knowledge about the safety and effectiveness of the reference product, and it enables a biosimilar biological product to be licensed based on less than a full complement of product-specific preclinical and clinical data.

A biosimilar product can only be approved by the FDA if it has the same mechanism(s) of action, route(s) of administration, dosage form(s) and strength(s) as the reference product, and only for the indication(s) and condition(s) of use that have been approved for the reference product. The facilities where biosimilars are manufactured must also meet the FDA’s standards.

There must be no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product in terms of safety and effectiveness. Only minor differences in clinically inactive components are allowable.

Zarxio has been approved as a biosimilar, not an interchangeable product. Under the BPCI Act, a biological product that has been approved as “interchangeable” may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the healthcare provider who prescribed the reference product.

For Zarxio’s approval, the FDA has designated a placeholder nonproprietary name for this product as “filgrastim-sndz.” The provision of a placeholder nonproprietary name should not be viewed as reflective of the agency’s decision on a comprehensive naming policy for biosimilars and other biological products.

While the FDA has not yet issued draft guidance on how current and future biological products marketed in the US should be named, the agency intends to do so in the near future.

For more details on Zarxio, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Agent decreases use of pain meds in SCD patients

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

An investigational agent may be able to treat vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to research published in Blood.

The drug, rivipansel (formerly GMI-1070), is designed to prevent cells from sticking together to improve blood flow.

In a phase 2 study, SCD patients who received rivipansel used significantly less pain medication than those who received placebo.

However, rivipansel did not significantly reduce the time to resolution of VOC.

Researchers said the study’s small size, as well as the wide variability in the length of time that all patients suffered painful vascular obstruction, may explain the lack of statistical significance. A larger, international study is set to begin later this year to provide greater clarity.

“We have not had good therapies for people with [sickle cell] disease,” said study author Marilyn J. Telen, MD, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“But this approach shows more promise than anything else I’ve seen in 34 years of treating sickle cell disease.”

She and her colleagues analyzed 76 SCD patients from 17 sites in the US. The patients were randomized to receive placebo or rivipansel. All patients also received the standard treatment for pain and symptom management.

For patients who received rivipansel, the effects tended to begin within 24 hours, and their painful crises passed sooner than those receiving only treatment for pain, but the statistical difference was not significant.

The least-squares mean time to resolution of VOC was 103.64 hours in the rivipansel arm and 144.60 hours in the placebo arm (P=0.192). The median times were 69.6 hours and 132.9 hours, respectively (P=0.187).

The researchers said the improvements seen in the amount of time to resolution would likely be clinically meaningful if they were verified in a larger trial.

The team also said the findings demonstrating lower use of pain medication among patients was a critical step forward. The team assessed cumulative parenteral opioid use, and the least-squares mean dose was 9.62 mg/kg in the rivipansel arm and 55.59 mg/kg in the placebo arm (P=0.010).

“The difference in pain medication use was statistically significant, and it occurred in the first 24 hours, which implies that the therapy may be interfering with the mechanism of the vaso-occlusion,” Dr Telen said. “For these patients, having less pain is very important.”

In addition, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to adverse events.

Dr Telen said the larger study of rivipansel is set to begin later this year, with a goal of enrolling more than 300 patients.

The company developing rivipansel, GlycoMimetics, Inc., funded the current study. And Dr Telen has received consulting fees from the company. ![]()

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

An investigational agent may be able to treat vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to research published in Blood.

The drug, rivipansel (formerly GMI-1070), is designed to prevent cells from sticking together to improve blood flow.

In a phase 2 study, SCD patients who received rivipansel used significantly less pain medication than those who received placebo.

However, rivipansel did not significantly reduce the time to resolution of VOC.

Researchers said the study’s small size, as well as the wide variability in the length of time that all patients suffered painful vascular obstruction, may explain the lack of statistical significance. A larger, international study is set to begin later this year to provide greater clarity.

“We have not had good therapies for people with [sickle cell] disease,” said study author Marilyn J. Telen, MD, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“But this approach shows more promise than anything else I’ve seen in 34 years of treating sickle cell disease.”

She and her colleagues analyzed 76 SCD patients from 17 sites in the US. The patients were randomized to receive placebo or rivipansel. All patients also received the standard treatment for pain and symptom management.

For patients who received rivipansel, the effects tended to begin within 24 hours, and their painful crises passed sooner than those receiving only treatment for pain, but the statistical difference was not significant.

The least-squares mean time to resolution of VOC was 103.64 hours in the rivipansel arm and 144.60 hours in the placebo arm (P=0.192). The median times were 69.6 hours and 132.9 hours, respectively (P=0.187).

The researchers said the improvements seen in the amount of time to resolution would likely be clinically meaningful if they were verified in a larger trial.

The team also said the findings demonstrating lower use of pain medication among patients was a critical step forward. The team assessed cumulative parenteral opioid use, and the least-squares mean dose was 9.62 mg/kg in the rivipansel arm and 55.59 mg/kg in the placebo arm (P=0.010).

“The difference in pain medication use was statistically significant, and it occurred in the first 24 hours, which implies that the therapy may be interfering with the mechanism of the vaso-occlusion,” Dr Telen said. “For these patients, having less pain is very important.”

In addition, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to adverse events.

Dr Telen said the larger study of rivipansel is set to begin later this year, with a goal of enrolling more than 300 patients.

The company developing rivipansel, GlycoMimetics, Inc., funded the current study. And Dr Telen has received consulting fees from the company. ![]()

and a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

An investigational agent may be able to treat vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to research published in Blood.

The drug, rivipansel (formerly GMI-1070), is designed to prevent cells from sticking together to improve blood flow.

In a phase 2 study, SCD patients who received rivipansel used significantly less pain medication than those who received placebo.

However, rivipansel did not significantly reduce the time to resolution of VOC.

Researchers said the study’s small size, as well as the wide variability in the length of time that all patients suffered painful vascular obstruction, may explain the lack of statistical significance. A larger, international study is set to begin later this year to provide greater clarity.

“We have not had good therapies for people with [sickle cell] disease,” said study author Marilyn J. Telen, MD, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“But this approach shows more promise than anything else I’ve seen in 34 years of treating sickle cell disease.”

She and her colleagues analyzed 76 SCD patients from 17 sites in the US. The patients were randomized to receive placebo or rivipansel. All patients also received the standard treatment for pain and symptom management.

For patients who received rivipansel, the effects tended to begin within 24 hours, and their painful crises passed sooner than those receiving only treatment for pain, but the statistical difference was not significant.

The least-squares mean time to resolution of VOC was 103.64 hours in the rivipansel arm and 144.60 hours in the placebo arm (P=0.192). The median times were 69.6 hours and 132.9 hours, respectively (P=0.187).

The researchers said the improvements seen in the amount of time to resolution would likely be clinically meaningful if they were verified in a larger trial.

The team also said the findings demonstrating lower use of pain medication among patients was a critical step forward. The team assessed cumulative parenteral opioid use, and the least-squares mean dose was 9.62 mg/kg in the rivipansel arm and 55.59 mg/kg in the placebo arm (P=0.010).

“The difference in pain medication use was statistically significant, and it occurred in the first 24 hours, which implies that the therapy may be interfering with the mechanism of the vaso-occlusion,” Dr Telen said. “For these patients, having less pain is very important.”

In addition, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to adverse events.

Dr Telen said the larger study of rivipansel is set to begin later this year, with a goal of enrolling more than 300 patients.

The company developing rivipansel, GlycoMimetics, Inc., funded the current study. And Dr Telen has received consulting fees from the company. ![]()

Too many blood tests can lead to anemia, transfusions

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A single-center study has shown that laboratory testing among patients undergoing cardiac surgery can lead to excessive bloodletting.

This can increase the risk of hospital-acquired anemia and, therefore, the need for blood transfusions.

Among cardiac surgery patients, transfusions have been associated with an increased risk of infection, more time spent on a ventilator, and a higher likelihood of death, said Colleen G. Koch, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

She and her colleagues conducted this research and published their findings in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

The researchers recorded every laboratory test performed on 1894 patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Cleveland Clinic from January to June 2012.

The team evaluated the number and type of blood tests performed from the time patients met their surgeons until hospital discharge, tallying up the total amount of blood taken from each patient.

‘Astonishing’ amount of blood drawn

There were 221,498 laboratory tests performed during the study period, or an average of 115 tests per patient. The most common tests were blood gas analyses (n=88,068), coagulation tests (n=39,535), complete blood counts (n=30,421), and metabolic panels (n=29,374).

The cumulative median phlebotomy volume for the entire hospital stay was 454 mL per patient. Patients tended to have more blood drawn if they were in the intensive care unit as compared to other hospital floors, with median phlebotomy volumes of 332 mL and 118 mL, respectively.

“We were astonished by the amount of blood taken from our patients for laboratory testing,” Dr Koch said. “Total phlebotomy volumes approached 1 to 2 units of red blood cells, which is roughly equivalent to 1 to 2 cans of soda.”

More complex procedures were associated with higher overall phlebotomy volume. Patients undergoing combined coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (CABG) and valve procedures had the highest median cumulative phlebotomy volume. The median volume was 653 mL for CABG-valve procedures, 448 mL for CABG alone, and 338 mL for valve procedures alone.

Transfusion need

The researchers also found that an increase in cumulative phlebotomy volume was linked to an increased need for blood products. Similarly, the longer a patient was hospitalized, the more blood was taken, which increased the subsequent need for a transfusion.

Overall, 49% of patients received red blood cells (RBCs), 25% fresh-frozen plasma (FFP), 33% platelets, and 15% cryoprecipitate.

Patients in the lowest phlebotomy volume quartile (0%-25th%) were much less likely to receive transfusions than patients in the highest quartile (75th% to 100th%).

In the lowest quartile, 2% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 3% FFP, 7% platelets, and 12% RBCs. In the highest quartile, 31% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 54% FFP, 61% platelets, and 87% RBCs.

So to reduce the use of transfusions, we must curb the use of blood tests, Dr Koch said, noting that patients can help.

“Patients should feel empowered to ask their doctors whether a specific test is necessary—’What is the indication for the test?,’ ‘Will it change my care?,’ and ‘If so, do you need to do it every day?,’” Dr Koch said.

“They should inquire whether smaller-volume test tubes could be used for the tests that are deemed necessary. Every attempt should be made to conserve the patient’s own blood. Every drop of blood counts.”

In an invited commentary, Milo Engoren, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, emphasized the importance of reducing blood loss to decrease possible complications during surgery.

“We make efforts to minimize intraoperative blood loss,” he noted. “Now, we need to make similar efforts postoperatively. While some may argue that transfusion itself is not harmful, but only a marker of a sicker patient, most would agree that avoiding anemia and transfusion is the best course for patients.” ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A single-center study has shown that laboratory testing among patients undergoing cardiac surgery can lead to excessive bloodletting.

This can increase the risk of hospital-acquired anemia and, therefore, the need for blood transfusions.

Among cardiac surgery patients, transfusions have been associated with an increased risk of infection, more time spent on a ventilator, and a higher likelihood of death, said Colleen G. Koch, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

She and her colleagues conducted this research and published their findings in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

The researchers recorded every laboratory test performed on 1894 patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Cleveland Clinic from January to June 2012.

The team evaluated the number and type of blood tests performed from the time patients met their surgeons until hospital discharge, tallying up the total amount of blood taken from each patient.

‘Astonishing’ amount of blood drawn

There were 221,498 laboratory tests performed during the study period, or an average of 115 tests per patient. The most common tests were blood gas analyses (n=88,068), coagulation tests (n=39,535), complete blood counts (n=30,421), and metabolic panels (n=29,374).

The cumulative median phlebotomy volume for the entire hospital stay was 454 mL per patient. Patients tended to have more blood drawn if they were in the intensive care unit as compared to other hospital floors, with median phlebotomy volumes of 332 mL and 118 mL, respectively.

“We were astonished by the amount of blood taken from our patients for laboratory testing,” Dr Koch said. “Total phlebotomy volumes approached 1 to 2 units of red blood cells, which is roughly equivalent to 1 to 2 cans of soda.”

More complex procedures were associated with higher overall phlebotomy volume. Patients undergoing combined coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (CABG) and valve procedures had the highest median cumulative phlebotomy volume. The median volume was 653 mL for CABG-valve procedures, 448 mL for CABG alone, and 338 mL for valve procedures alone.

Transfusion need

The researchers also found that an increase in cumulative phlebotomy volume was linked to an increased need for blood products. Similarly, the longer a patient was hospitalized, the more blood was taken, which increased the subsequent need for a transfusion.

Overall, 49% of patients received red blood cells (RBCs), 25% fresh-frozen plasma (FFP), 33% platelets, and 15% cryoprecipitate.

Patients in the lowest phlebotomy volume quartile (0%-25th%) were much less likely to receive transfusions than patients in the highest quartile (75th% to 100th%).

In the lowest quartile, 2% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 3% FFP, 7% platelets, and 12% RBCs. In the highest quartile, 31% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 54% FFP, 61% platelets, and 87% RBCs.

So to reduce the use of transfusions, we must curb the use of blood tests, Dr Koch said, noting that patients can help.

“Patients should feel empowered to ask their doctors whether a specific test is necessary—’What is the indication for the test?,’ ‘Will it change my care?,’ and ‘If so, do you need to do it every day?,’” Dr Koch said.

“They should inquire whether smaller-volume test tubes could be used for the tests that are deemed necessary. Every attempt should be made to conserve the patient’s own blood. Every drop of blood counts.”

In an invited commentary, Milo Engoren, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, emphasized the importance of reducing blood loss to decrease possible complications during surgery.

“We make efforts to minimize intraoperative blood loss,” he noted. “Now, we need to make similar efforts postoperatively. While some may argue that transfusion itself is not harmful, but only a marker of a sicker patient, most would agree that avoiding anemia and transfusion is the best course for patients.” ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A single-center study has shown that laboratory testing among patients undergoing cardiac surgery can lead to excessive bloodletting.

This can increase the risk of hospital-acquired anemia and, therefore, the need for blood transfusions.

Among cardiac surgery patients, transfusions have been associated with an increased risk of infection, more time spent on a ventilator, and a higher likelihood of death, said Colleen G. Koch, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

She and her colleagues conducted this research and published their findings in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.

The researchers recorded every laboratory test performed on 1894 patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Cleveland Clinic from January to June 2012.

The team evaluated the number and type of blood tests performed from the time patients met their surgeons until hospital discharge, tallying up the total amount of blood taken from each patient.

‘Astonishing’ amount of blood drawn

There were 221,498 laboratory tests performed during the study period, or an average of 115 tests per patient. The most common tests were blood gas analyses (n=88,068), coagulation tests (n=39,535), complete blood counts (n=30,421), and metabolic panels (n=29,374).

The cumulative median phlebotomy volume for the entire hospital stay was 454 mL per patient. Patients tended to have more blood drawn if they were in the intensive care unit as compared to other hospital floors, with median phlebotomy volumes of 332 mL and 118 mL, respectively.

“We were astonished by the amount of blood taken from our patients for laboratory testing,” Dr Koch said. “Total phlebotomy volumes approached 1 to 2 units of red blood cells, which is roughly equivalent to 1 to 2 cans of soda.”

More complex procedures were associated with higher overall phlebotomy volume. Patients undergoing combined coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (CABG) and valve procedures had the highest median cumulative phlebotomy volume. The median volume was 653 mL for CABG-valve procedures, 448 mL for CABG alone, and 338 mL for valve procedures alone.

Transfusion need

The researchers also found that an increase in cumulative phlebotomy volume was linked to an increased need for blood products. Similarly, the longer a patient was hospitalized, the more blood was taken, which increased the subsequent need for a transfusion.

Overall, 49% of patients received red blood cells (RBCs), 25% fresh-frozen plasma (FFP), 33% platelets, and 15% cryoprecipitate.

Patients in the lowest phlebotomy volume quartile (0%-25th%) were much less likely to receive transfusions than patients in the highest quartile (75th% to 100th%).

In the lowest quartile, 2% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 3% FFP, 7% platelets, and 12% RBCs. In the highest quartile, 31% of patients received cryoprecipitate, 54% FFP, 61% platelets, and 87% RBCs.

So to reduce the use of transfusions, we must curb the use of blood tests, Dr Koch said, noting that patients can help.

“Patients should feel empowered to ask their doctors whether a specific test is necessary—’What is the indication for the test?,’ ‘Will it change my care?,’ and ‘If so, do you need to do it every day?,’” Dr Koch said.

“They should inquire whether smaller-volume test tubes could be used for the tests that are deemed necessary. Every attempt should be made to conserve the patient’s own blood. Every drop of blood counts.”

In an invited commentary, Milo Engoren, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, emphasized the importance of reducing blood loss to decrease possible complications during surgery.

“We make efforts to minimize intraoperative blood loss,” he noted. “Now, we need to make similar efforts postoperatively. While some may argue that transfusion itself is not harmful, but only a marker of a sicker patient, most would agree that avoiding anemia and transfusion is the best course for patients.” ![]()

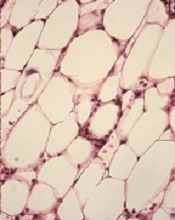

Cancer-Related Anemia

Anemia occurs in more than half of patients with cancer and is associated with worse performance status, quality of life, and survival. Anemia is often attributed to the effects of chemotherapy; however, a 2004 European Cancer Anemia Survey reported that 39% of patients with cancer were anemic prior to starting chemotherapy and the incidence of anemia may be as high as 90% in patients on chemotherapy. The pathogenesis of cancer-related anemia is multifactorial; it can be a direct result of cancer invading the bone marrow, or result from the effects of radiation, chemotherapy-induced anemia, chronic renal disease, and cancer-related inflammation leading to functional iron deficiency anemia.

To read the full article in PDF:

Anemia occurs in more than half of patients with cancer and is associated with worse performance status, quality of life, and survival. Anemia is often attributed to the effects of chemotherapy; however, a 2004 European Cancer Anemia Survey reported that 39% of patients with cancer were anemic prior to starting chemotherapy and the incidence of anemia may be as high as 90% in patients on chemotherapy. The pathogenesis of cancer-related anemia is multifactorial; it can be a direct result of cancer invading the bone marrow, or result from the effects of radiation, chemotherapy-induced anemia, chronic renal disease, and cancer-related inflammation leading to functional iron deficiency anemia.

To read the full article in PDF:

Anemia occurs in more than half of patients with cancer and is associated with worse performance status, quality of life, and survival. Anemia is often attributed to the effects of chemotherapy; however, a 2004 European Cancer Anemia Survey reported that 39% of patients with cancer were anemic prior to starting chemotherapy and the incidence of anemia may be as high as 90% in patients on chemotherapy. The pathogenesis of cancer-related anemia is multifactorial; it can be a direct result of cancer invading the bone marrow, or result from the effects of radiation, chemotherapy-induced anemia, chronic renal disease, and cancer-related inflammation leading to functional iron deficiency anemia.

To read the full article in PDF:

Quick antibiotic delivery reduces intensive care needs

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Time is of the essence when delivering antibiotics to pediatric cancer patients who present with fever and neutropenia, a new study suggests.

Patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes of hospital admission were significantly less likely to require intensive care than patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour.

Children who received antibiotics faster also had a lower mortality rate, but the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant.

Joanne Hilden, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, and her colleagues detailed these results in Pediatric Blood & Cancer.

Dr Hilden noted that administering antibiotics within 60 minutes of a patient’s admission can be difficult, but she and her colleagues were able to adopt policies that sped up the process at their institution.

“We’re talking about kids who have gone home after chemotherapy and then a parent calls the hospital reporting a fever,” Dr Hilden said. “The question is, can we get the patient back to the hospital, then get a white cell count, and get antibiotics on board when needed all within an hour of their arrival?”

“It’s a huge challenge. This study shows that it’s important we make it happen. There’s less intensive care and fewer fatalities for kids who get antibiotics sooner.”

To determine the impact of timely antibiotic administration, Dr Hilden and her colleagues initially analyzed 116 children with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies who developed fever and neutropenia.

But the team found no significant differences in outcomes whether patients received antibiotics within or outside of the 60-minute window.

So the researchers extended the time period of their study and expanded the cohort to 220 patients.

This time, only the need for intensive care unit (ICU)-level care was significantly different between the 2 groups, with 12.6% of patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes requiring ICU-level care, compared to 29.9% of patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour (P=0.003).

The researchers also found differences between the 2 groups with regard to the mean length of hospital stay (6.9 days vs 5.7 days), the mean duration of fever (3 days vs 2 days), the need for imaging workup (5.2% vs 9.1%), the incidence of bacteremia (13% vs 15.4%), and mortality rate (3.9% vs 0.7%). But none of these differences were statistically significant.

Still, Dr Hilden and her colleagues said it was important to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery at their institution, which took an average of 150 minutes when this study began. By instituting new policies, the team found they could deliver antibiotics in less than 60 minutes nearly 100% of the time.

To do this, hospital staff began prescribing antibiotics upon a pediatric cancer patient’s arrival, holding that order, and then allowing antibiotics to be delivered immediately after learning the results of neutrophil count testing. This eliminated the need to find a prescriber once the patient’s white blood cell count was known.

The researchers also found they could cut the time needed to determine a patient’s neutrophil count. Traditionally, determining neutropenia requires a full white blood cell count, followed by a differential by a human technician. But human verification reverses the machine results in less than 0.5% of cases.

The team discovered that the benefit of speed obtained by eliminating human verification outweighed the risk of administering unneeded antibiotics in very few cases. Depending on preliminary rather than technician-verified results of white cell counts reduced the time of testing from 45 minutes to 20.

The researchers also instituted changes to clinic flow procedures, such as notifying the full care team as soon as a family was advised to come into the hospital.

“Another thing we show is that just increasing the awareness of how important it is to get antibiotics on board quickly in these cases speeds delivery,” Dr Hilden said.

This knowledge and the aforementioned interventions allowed the researchers to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery to a median of 46 minutes.

“Only 11% of pediatric cancer patients with fever and neutropenia have serious complications,” Dr Hilden noted. “That’s low, but we can make it 0%, and this study shows that getting antibiotics onboard quickly goes a long way toward that goal.” ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Time is of the essence when delivering antibiotics to pediatric cancer patients who present with fever and neutropenia, a new study suggests.

Patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes of hospital admission were significantly less likely to require intensive care than patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour.

Children who received antibiotics faster also had a lower mortality rate, but the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant.

Joanne Hilden, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, and her colleagues detailed these results in Pediatric Blood & Cancer.

Dr Hilden noted that administering antibiotics within 60 minutes of a patient’s admission can be difficult, but she and her colleagues were able to adopt policies that sped up the process at their institution.

“We’re talking about kids who have gone home after chemotherapy and then a parent calls the hospital reporting a fever,” Dr Hilden said. “The question is, can we get the patient back to the hospital, then get a white cell count, and get antibiotics on board when needed all within an hour of their arrival?”

“It’s a huge challenge. This study shows that it’s important we make it happen. There’s less intensive care and fewer fatalities for kids who get antibiotics sooner.”

To determine the impact of timely antibiotic administration, Dr Hilden and her colleagues initially analyzed 116 children with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies who developed fever and neutropenia.

But the team found no significant differences in outcomes whether patients received antibiotics within or outside of the 60-minute window.

So the researchers extended the time period of their study and expanded the cohort to 220 patients.

This time, only the need for intensive care unit (ICU)-level care was significantly different between the 2 groups, with 12.6% of patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes requiring ICU-level care, compared to 29.9% of patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour (P=0.003).

The researchers also found differences between the 2 groups with regard to the mean length of hospital stay (6.9 days vs 5.7 days), the mean duration of fever (3 days vs 2 days), the need for imaging workup (5.2% vs 9.1%), the incidence of bacteremia (13% vs 15.4%), and mortality rate (3.9% vs 0.7%). But none of these differences were statistically significant.

Still, Dr Hilden and her colleagues said it was important to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery at their institution, which took an average of 150 minutes when this study began. By instituting new policies, the team found they could deliver antibiotics in less than 60 minutes nearly 100% of the time.

To do this, hospital staff began prescribing antibiotics upon a pediatric cancer patient’s arrival, holding that order, and then allowing antibiotics to be delivered immediately after learning the results of neutrophil count testing. This eliminated the need to find a prescriber once the patient’s white blood cell count was known.

The researchers also found they could cut the time needed to determine a patient’s neutrophil count. Traditionally, determining neutropenia requires a full white blood cell count, followed by a differential by a human technician. But human verification reverses the machine results in less than 0.5% of cases.

The team discovered that the benefit of speed obtained by eliminating human verification outweighed the risk of administering unneeded antibiotics in very few cases. Depending on preliminary rather than technician-verified results of white cell counts reduced the time of testing from 45 minutes to 20.

The researchers also instituted changes to clinic flow procedures, such as notifying the full care team as soon as a family was advised to come into the hospital.

“Another thing we show is that just increasing the awareness of how important it is to get antibiotics on board quickly in these cases speeds delivery,” Dr Hilden said.

This knowledge and the aforementioned interventions allowed the researchers to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery to a median of 46 minutes.

“Only 11% of pediatric cancer patients with fever and neutropenia have serious complications,” Dr Hilden noted. “That’s low, but we can make it 0%, and this study shows that getting antibiotics onboard quickly goes a long way toward that goal.” ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Time is of the essence when delivering antibiotics to pediatric cancer patients who present with fever and neutropenia, a new study suggests.

Patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes of hospital admission were significantly less likely to require intensive care than patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour.

Children who received antibiotics faster also had a lower mortality rate, but the difference between the 2 groups was not statistically significant.

Joanne Hilden, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, and her colleagues detailed these results in Pediatric Blood & Cancer.

Dr Hilden noted that administering antibiotics within 60 minutes of a patient’s admission can be difficult, but she and her colleagues were able to adopt policies that sped up the process at their institution.

“We’re talking about kids who have gone home after chemotherapy and then a parent calls the hospital reporting a fever,” Dr Hilden said. “The question is, can we get the patient back to the hospital, then get a white cell count, and get antibiotics on board when needed all within an hour of their arrival?”

“It’s a huge challenge. This study shows that it’s important we make it happen. There’s less intensive care and fewer fatalities for kids who get antibiotics sooner.”

To determine the impact of timely antibiotic administration, Dr Hilden and her colleagues initially analyzed 116 children with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies who developed fever and neutropenia.

But the team found no significant differences in outcomes whether patients received antibiotics within or outside of the 60-minute window.

So the researchers extended the time period of their study and expanded the cohort to 220 patients.

This time, only the need for intensive care unit (ICU)-level care was significantly different between the 2 groups, with 12.6% of patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes requiring ICU-level care, compared to 29.9% of patients who received antibiotics outside of an hour (P=0.003).

The researchers also found differences between the 2 groups with regard to the mean length of hospital stay (6.9 days vs 5.7 days), the mean duration of fever (3 days vs 2 days), the need for imaging workup (5.2% vs 9.1%), the incidence of bacteremia (13% vs 15.4%), and mortality rate (3.9% vs 0.7%). But none of these differences were statistically significant.

Still, Dr Hilden and her colleagues said it was important to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery at their institution, which took an average of 150 minutes when this study began. By instituting new policies, the team found they could deliver antibiotics in less than 60 minutes nearly 100% of the time.

To do this, hospital staff began prescribing antibiotics upon a pediatric cancer patient’s arrival, holding that order, and then allowing antibiotics to be delivered immediately after learning the results of neutrophil count testing. This eliminated the need to find a prescriber once the patient’s white blood cell count was known.

The researchers also found they could cut the time needed to determine a patient’s neutrophil count. Traditionally, determining neutropenia requires a full white blood cell count, followed by a differential by a human technician. But human verification reverses the machine results in less than 0.5% of cases.

The team discovered that the benefit of speed obtained by eliminating human verification outweighed the risk of administering unneeded antibiotics in very few cases. Depending on preliminary rather than technician-verified results of white cell counts reduced the time of testing from 45 minutes to 20.

The researchers also instituted changes to clinic flow procedures, such as notifying the full care team as soon as a family was advised to come into the hospital.

“Another thing we show is that just increasing the awareness of how important it is to get antibiotics on board quickly in these cases speeds delivery,” Dr Hilden said.

This knowledge and the aforementioned interventions allowed the researchers to reduce the time to antibiotic delivery to a median of 46 minutes.

“Only 11% of pediatric cancer patients with fever and neutropenia have serious complications,” Dr Hilden noted. “That’s low, but we can make it 0%, and this study shows that getting antibiotics onboard quickly goes a long way toward that goal.”

Study provides new insights regarding HSCs, FA

with Fanconi anemia

Image by Michael Milsom

Environmental stress is a major factor driving DNA damage in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), according to research published in Nature.