User login

SHM’s Twitter Contest Encourages Appropriate Antibiotic Prescribing

- Identify opportunities to engage with all hospital-based clinicians to improve antibiotic stewardship in your hospital.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns and identify mechanisms to educate providers on overprescribing in your hospital.

- Consider the following:

Adhere to antibiotic treatment guidelines.

Track the day.

Set a stop date.

Reevaluate therapy.

Streamline therapy.

Avoid automatic time courses.

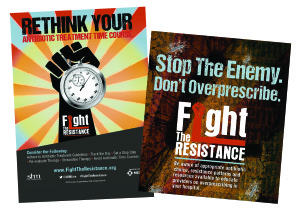

Not only did participants receive recognition for their efforts hanging up the posters and engaging their teams, the posters’ presence in various hospitals and offices around the country created thousands of impressions among hospital-based staff and others directly responsible for proper antibiotic prescribing.

Although the contest is over, you can still help facilitate culture change related to appropriate antibiotic prescribing. Follow SHM on Twitter @SHMLive, and continue to visit FightTheResistance.org for the latest updates on the campaign and new tools to promote antibiotic stewardship. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

- Identify opportunities to engage with all hospital-based clinicians to improve antibiotic stewardship in your hospital.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns and identify mechanisms to educate providers on overprescribing in your hospital.

- Consider the following:

Adhere to antibiotic treatment guidelines.

Track the day.

Set a stop date.

Reevaluate therapy.

Streamline therapy.

Avoid automatic time courses.

Not only did participants receive recognition for their efforts hanging up the posters and engaging their teams, the posters’ presence in various hospitals and offices around the country created thousands of impressions among hospital-based staff and others directly responsible for proper antibiotic prescribing.

Although the contest is over, you can still help facilitate culture change related to appropriate antibiotic prescribing. Follow SHM on Twitter @SHMLive, and continue to visit FightTheResistance.org for the latest updates on the campaign and new tools to promote antibiotic stewardship. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

- Identify opportunities to engage with all hospital-based clinicians to improve antibiotic stewardship in your hospital.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns and identify mechanisms to educate providers on overprescribing in your hospital.

- Consider the following:

Adhere to antibiotic treatment guidelines.

Track the day.

Set a stop date.

Reevaluate therapy.

Streamline therapy.

Avoid automatic time courses.

Not only did participants receive recognition for their efforts hanging up the posters and engaging their teams, the posters’ presence in various hospitals and offices around the country created thousands of impressions among hospital-based staff and others directly responsible for proper antibiotic prescribing.

Although the contest is over, you can still help facilitate culture change related to appropriate antibiotic prescribing. Follow SHM on Twitter @SHMLive, and continue to visit FightTheResistance.org for the latest updates on the campaign and new tools to promote antibiotic stewardship. TH

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Antibiotic-resistant infections remain a persistent threat

One in every seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In long-term acute care hospitals, that number increased to one in four.

Those are key findings from a study published March 3 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that is the first to combine national data on antibiotic-resistant (AR) bacteria threats with progress on health care–associated infections (HAIs).

“Antibiotic resistance threatens to return us to a time when a simple infection could kill,” CDC Director Thomas Frieden said during a March 3 telebriefing. “The more people who get infected with resistant bacteria, the more people who suffer complications, the more who, tragically, may die from preventable infections. On any given day about one in 25 hospitalized patients has at least one health care–associated infection that they didn’t come in with. No one should get sick when they’re trying to get well.”

For the study, researchers led by Dr. Clifford McDonald of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, collected data on specific infections that were reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2014 by approximately 4,000 short-term acute care hospitals, 501 long-term acute care hospitals, and 1,135 inpatient rehabilitation facilities in all 50 states (MMWR. 2016 Mar 3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509e1er). Next, they determined the proportions of AR pathogens and HAIs caused by any of six resistant bacteria highlighted by the CDC in 2013 as urgent or serious threats: CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (extended-spectrum beta-lactamases), VRE (vancomycin-resistant enterococci), multidrug-resistant pseudomonas, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter.

The researchers found that, compared with historical data from 5-8 years earlier, central line–associated bloodstream infections decreased by 50% and surgical site infections (SSIs) by 17% in 2014.

“There is encouraging news here,” Dr. Frieden said. “Doctors, nurses, hospitals, health care systems and other partners have made progress preventing some health care–associated infections.” However, the study found that one in six remaining central line-associated bloodstream infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria, while one in seven remaining surgical site infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

While catheter-associated urinary tract infections appear unchanged from baseline, there have been recent decreases, according to the study. In addition, C. difficile infections in hospitals decreased 8% between 2011 and 2014.

Dr. McDonald and his associates determined that in 2014, one in seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by one of the six antibiotic-resistance threat bacteria, “which is deeply concerning,” Dr. Frieden said. That number increased to one in four infections in long-term acute care hospitals, a proportion that he characterized as “chilling.”

The CDC recommends three strategies that doctors, nurses, and other health care providers should take with every patient, to prevent HAIs and stop the spread of antibiotic resistance:

• Prevent the spread of bacteria between patients. Dr. Peter Pronovost, who participated in the telebriefing, said that he and his associates at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore “do this by practicing good hand hygiene techniques by wearing sterile equipment when inserting lines.”

• Prevent surgery-related infections and/or placement of a catheter. “Check catheters frequently and remove them when you no longer need them,” advised Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins. “Ask if you actually need them before you even place them.”

• Improve antibiotic use through stewardship. This means using “the right antibiotics for the right duration,” Dr. Pronovost said. “Antibiotics could be lifesaving and are necessary for critically ill patients, especially those with septic shock. But these antibiotics need to be adjusted based on lab results and new information about the organisms that are causing these infections. Forty-eight hours after antibiotics are initiated, take a ‘time out.’ Perform a brief but focused assessment to determine if antibiotic therapy is still needed, or if it should be refined. A common mistake we make is to continue vancomycin when there is no presence of MRSA. We often tell our staff at Johns Hopkins, ‘if it doesn’t grow, let it go.’ ”

Dr. Frieden concluded his remarks by noting that physicians and other clinicians on the front lines “need support of their facility leadership,” to prevent HAIs. “Health care facilities, CEOs, and administrators are a major part of the solution. It’s important that they make a priority of infection prevention, sepsis prevention, and antibiotic stewardship. Know your facility’s data and target prevention efforts to ensure improvements in patient safety.”

One in every seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In long-term acute care hospitals, that number increased to one in four.

Those are key findings from a study published March 3 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that is the first to combine national data on antibiotic-resistant (AR) bacteria threats with progress on health care–associated infections (HAIs).

“Antibiotic resistance threatens to return us to a time when a simple infection could kill,” CDC Director Thomas Frieden said during a March 3 telebriefing. “The more people who get infected with resistant bacteria, the more people who suffer complications, the more who, tragically, may die from preventable infections. On any given day about one in 25 hospitalized patients has at least one health care–associated infection that they didn’t come in with. No one should get sick when they’re trying to get well.”

For the study, researchers led by Dr. Clifford McDonald of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, collected data on specific infections that were reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2014 by approximately 4,000 short-term acute care hospitals, 501 long-term acute care hospitals, and 1,135 inpatient rehabilitation facilities in all 50 states (MMWR. 2016 Mar 3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509e1er). Next, they determined the proportions of AR pathogens and HAIs caused by any of six resistant bacteria highlighted by the CDC in 2013 as urgent or serious threats: CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (extended-spectrum beta-lactamases), VRE (vancomycin-resistant enterococci), multidrug-resistant pseudomonas, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter.

The researchers found that, compared with historical data from 5-8 years earlier, central line–associated bloodstream infections decreased by 50% and surgical site infections (SSIs) by 17% in 2014.

“There is encouraging news here,” Dr. Frieden said. “Doctors, nurses, hospitals, health care systems and other partners have made progress preventing some health care–associated infections.” However, the study found that one in six remaining central line-associated bloodstream infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria, while one in seven remaining surgical site infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

While catheter-associated urinary tract infections appear unchanged from baseline, there have been recent decreases, according to the study. In addition, C. difficile infections in hospitals decreased 8% between 2011 and 2014.

Dr. McDonald and his associates determined that in 2014, one in seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by one of the six antibiotic-resistance threat bacteria, “which is deeply concerning,” Dr. Frieden said. That number increased to one in four infections in long-term acute care hospitals, a proportion that he characterized as “chilling.”

The CDC recommends three strategies that doctors, nurses, and other health care providers should take with every patient, to prevent HAIs and stop the spread of antibiotic resistance:

• Prevent the spread of bacteria between patients. Dr. Peter Pronovost, who participated in the telebriefing, said that he and his associates at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore “do this by practicing good hand hygiene techniques by wearing sterile equipment when inserting lines.”

• Prevent surgery-related infections and/or placement of a catheter. “Check catheters frequently and remove them when you no longer need them,” advised Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins. “Ask if you actually need them before you even place them.”

• Improve antibiotic use through stewardship. This means using “the right antibiotics for the right duration,” Dr. Pronovost said. “Antibiotics could be lifesaving and are necessary for critically ill patients, especially those with septic shock. But these antibiotics need to be adjusted based on lab results and new information about the organisms that are causing these infections. Forty-eight hours after antibiotics are initiated, take a ‘time out.’ Perform a brief but focused assessment to determine if antibiotic therapy is still needed, or if it should be refined. A common mistake we make is to continue vancomycin when there is no presence of MRSA. We often tell our staff at Johns Hopkins, ‘if it doesn’t grow, let it go.’ ”

Dr. Frieden concluded his remarks by noting that physicians and other clinicians on the front lines “need support of their facility leadership,” to prevent HAIs. “Health care facilities, CEOs, and administrators are a major part of the solution. It’s important that they make a priority of infection prevention, sepsis prevention, and antibiotic stewardship. Know your facility’s data and target prevention efforts to ensure improvements in patient safety.”

One in every seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In long-term acute care hospitals, that number increased to one in four.

Those are key findings from a study published March 3 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that is the first to combine national data on antibiotic-resistant (AR) bacteria threats with progress on health care–associated infections (HAIs).

“Antibiotic resistance threatens to return us to a time when a simple infection could kill,” CDC Director Thomas Frieden said during a March 3 telebriefing. “The more people who get infected with resistant bacteria, the more people who suffer complications, the more who, tragically, may die from preventable infections. On any given day about one in 25 hospitalized patients has at least one health care–associated infection that they didn’t come in with. No one should get sick when they’re trying to get well.”

For the study, researchers led by Dr. Clifford McDonald of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, collected data on specific infections that were reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2014 by approximately 4,000 short-term acute care hospitals, 501 long-term acute care hospitals, and 1,135 inpatient rehabilitation facilities in all 50 states (MMWR. 2016 Mar 3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6509e1er). Next, they determined the proportions of AR pathogens and HAIs caused by any of six resistant bacteria highlighted by the CDC in 2013 as urgent or serious threats: CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (extended-spectrum beta-lactamases), VRE (vancomycin-resistant enterococci), multidrug-resistant pseudomonas, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter.

The researchers found that, compared with historical data from 5-8 years earlier, central line–associated bloodstream infections decreased by 50% and surgical site infections (SSIs) by 17% in 2014.

“There is encouraging news here,” Dr. Frieden said. “Doctors, nurses, hospitals, health care systems and other partners have made progress preventing some health care–associated infections.” However, the study found that one in six remaining central line-associated bloodstream infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria, while one in seven remaining surgical site infections were caused by urgent or serious antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

While catheter-associated urinary tract infections appear unchanged from baseline, there have been recent decreases, according to the study. In addition, C. difficile infections in hospitals decreased 8% between 2011 and 2014.

Dr. McDonald and his associates determined that in 2014, one in seven infections in acute care hospitals related to catheters and surgeries was caused by one of the six antibiotic-resistance threat bacteria, “which is deeply concerning,” Dr. Frieden said. That number increased to one in four infections in long-term acute care hospitals, a proportion that he characterized as “chilling.”

The CDC recommends three strategies that doctors, nurses, and other health care providers should take with every patient, to prevent HAIs and stop the spread of antibiotic resistance:

• Prevent the spread of bacteria between patients. Dr. Peter Pronovost, who participated in the telebriefing, said that he and his associates at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore “do this by practicing good hand hygiene techniques by wearing sterile equipment when inserting lines.”

• Prevent surgery-related infections and/or placement of a catheter. “Check catheters frequently and remove them when you no longer need them,” advised Dr. Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality at Johns Hopkins. “Ask if you actually need them before you even place them.”

• Improve antibiotic use through stewardship. This means using “the right antibiotics for the right duration,” Dr. Pronovost said. “Antibiotics could be lifesaving and are necessary for critically ill patients, especially those with septic shock. But these antibiotics need to be adjusted based on lab results and new information about the organisms that are causing these infections. Forty-eight hours after antibiotics are initiated, take a ‘time out.’ Perform a brief but focused assessment to determine if antibiotic therapy is still needed, or if it should be refined. A common mistake we make is to continue vancomycin when there is no presence of MRSA. We often tell our staff at Johns Hopkins, ‘if it doesn’t grow, let it go.’ ”

Dr. Frieden concluded his remarks by noting that physicians and other clinicians on the front lines “need support of their facility leadership,” to prevent HAIs. “Health care facilities, CEOs, and administrators are a major part of the solution. It’s important that they make a priority of infection prevention, sepsis prevention, and antibiotic stewardship. Know your facility’s data and target prevention efforts to ensure improvements in patient safety.”

FROM MMWR

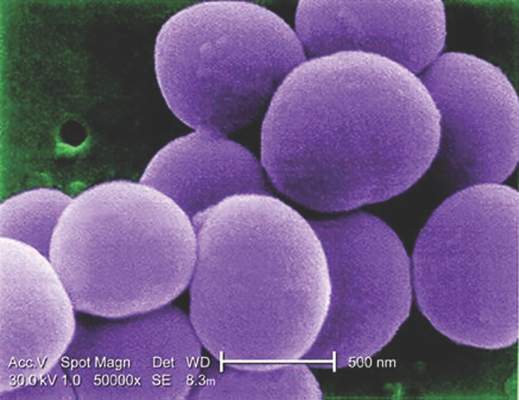

MRSA incidence decreased in children as clindamycin resistance increased

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections has decreased in children in recent years while resistance to clindamycin has increased.

Major finding: MRSA susceptibility to oxacillin increased to 68.4% in 2014, and susceptibility dropped to 86% for clindamycin.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 41,745 S. aureus isolates from 39,209 patients under age 18 years in the U.S. Military Health System between 2005 and 2014.

Disclosures: The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Fecal microbiota transplants achieved C. difficile resolution

An open-label study of fecal microbiota transfer in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection has achieved clinical resolution in 96.7% of patients, according to a paper published online Feb. 8 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Researchers treated 30 patients with two different dosing regimens of fractionated and encapsulated stool specimens from healthy donors, given after antibiotic therapy for a current episode of C. difficile infection.

At 8 weeks after dosing, 26 patients (86.7%) had had no C. difficile–positive diarrhea, and of the 4 who did have symptoms, 3 had early self-limiting diarrhea but tested negative for C. difficile carriage at 8 weeks, meaning that overall, 29 of the 30 patients achieved clinical resolution.

Patients also showed significant increases in microbial diversity from day 4 after treatment, and by week 8, the engrafted spore-forming bacteria made up around one-third of the total gut microbial carriage, with no serious adverse events related to the treatment (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb. 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv766).

“Although our study is limited by the lack of a placebo arm, the single clinical recurrence of C. difficile diarrhea in this study contrasts starkly with the recurrence rates documented in the placebo arms of three randomized, controlled trials involving patients with similar demographic characteristics and histories of recurrent episodes of [C. difficile infection],” wrote Dr. Sahil Khanna of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and coauthors.

The study was sponsored by Seres Therapeutics. One author reported a consultancy with Seres Therapeutics, and eight authors were employees of and held equity positions in Seres Therapeutics.

The development of SER-109 represents another major step toward fully engineered microbiota transfer, but we are still only halfway there.

Long-term safety databases are likely to play an important role in documenting currently unknown safety aspects of fecal microbiota transfer, and input from basic and clinical research is crucial to the identification of new indications.

Dr. Maria J.G.T. Vehreschild and Dr. Oliver A. Cornely are from the department of internal medicine at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany). These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv768). The authors declared speakers bureau positions, lecture honoraria, research funding, and consultancies from a range of pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Cornely disclosed a consultancy with Seres.

The development of SER-109 represents another major step toward fully engineered microbiota transfer, but we are still only halfway there.

Long-term safety databases are likely to play an important role in documenting currently unknown safety aspects of fecal microbiota transfer, and input from basic and clinical research is crucial to the identification of new indications.

Dr. Maria J.G.T. Vehreschild and Dr. Oliver A. Cornely are from the department of internal medicine at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany). These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv768). The authors declared speakers bureau positions, lecture honoraria, research funding, and consultancies from a range of pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Cornely disclosed a consultancy with Seres.

The development of SER-109 represents another major step toward fully engineered microbiota transfer, but we are still only halfway there.

Long-term safety databases are likely to play an important role in documenting currently unknown safety aspects of fecal microbiota transfer, and input from basic and clinical research is crucial to the identification of new indications.

Dr. Maria J.G.T. Vehreschild and Dr. Oliver A. Cornely are from the department of internal medicine at the University Hospital Cologne (Germany). These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv768). The authors declared speakers bureau positions, lecture honoraria, research funding, and consultancies from a range of pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Cornely disclosed a consultancy with Seres.

An open-label study of fecal microbiota transfer in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection has achieved clinical resolution in 96.7% of patients, according to a paper published online Feb. 8 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Researchers treated 30 patients with two different dosing regimens of fractionated and encapsulated stool specimens from healthy donors, given after antibiotic therapy for a current episode of C. difficile infection.

At 8 weeks after dosing, 26 patients (86.7%) had had no C. difficile–positive diarrhea, and of the 4 who did have symptoms, 3 had early self-limiting diarrhea but tested negative for C. difficile carriage at 8 weeks, meaning that overall, 29 of the 30 patients achieved clinical resolution.

Patients also showed significant increases in microbial diversity from day 4 after treatment, and by week 8, the engrafted spore-forming bacteria made up around one-third of the total gut microbial carriage, with no serious adverse events related to the treatment (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb. 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv766).

“Although our study is limited by the lack of a placebo arm, the single clinical recurrence of C. difficile diarrhea in this study contrasts starkly with the recurrence rates documented in the placebo arms of three randomized, controlled trials involving patients with similar demographic characteristics and histories of recurrent episodes of [C. difficile infection],” wrote Dr. Sahil Khanna of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and coauthors.

The study was sponsored by Seres Therapeutics. One author reported a consultancy with Seres Therapeutics, and eight authors were employees of and held equity positions in Seres Therapeutics.

An open-label study of fecal microbiota transfer in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection has achieved clinical resolution in 96.7% of patients, according to a paper published online Feb. 8 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Researchers treated 30 patients with two different dosing regimens of fractionated and encapsulated stool specimens from healthy donors, given after antibiotic therapy for a current episode of C. difficile infection.

At 8 weeks after dosing, 26 patients (86.7%) had had no C. difficile–positive diarrhea, and of the 4 who did have symptoms, 3 had early self-limiting diarrhea but tested negative for C. difficile carriage at 8 weeks, meaning that overall, 29 of the 30 patients achieved clinical resolution.

Patients also showed significant increases in microbial diversity from day 4 after treatment, and by week 8, the engrafted spore-forming bacteria made up around one-third of the total gut microbial carriage, with no serious adverse events related to the treatment (J Infect Diseases. 2016 Feb. 8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv766).

“Although our study is limited by the lack of a placebo arm, the single clinical recurrence of C. difficile diarrhea in this study contrasts starkly with the recurrence rates documented in the placebo arms of three randomized, controlled trials involving patients with similar demographic characteristics and histories of recurrent episodes of [C. difficile infection],” wrote Dr. Sahil Khanna of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and coauthors.

The study was sponsored by Seres Therapeutics. One author reported a consultancy with Seres Therapeutics, and eight authors were employees of and held equity positions in Seres Therapeutics.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Fecal microbiota transplants were highly efficacious in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in a study of 30 patients.

Major finding: Fecal microbiota transplants achieved clinical resolution of C. difficile infection in 96.7% of patients by 8 weeks.

Data source: An open-label study in 30 patients with recurrent C. difficile infection.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Seres Therapeutics. One author reported a consultancy with Seres Therapeutics, and eight authors were employees of and held equity positions in Seres Therapeutics.

Infection control is everyone’s responsibility

Big things come in small packages, very small – so small they may even be invisible to the naked eye. Take for instance a huge infection causing multiorgan system failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, even septic shock refractory to high-dose pressors. This catastrophe may be the end result of exposure to tiny pathogenic microbes that can take down an otherwise healthy 300-pound man, tout suite!

Microorganisms are everywhere. We can’t live without them, but we can’t live with certain ones either. Unless you live in a bubble you are going to be exposed to countless bacteria each and every day. They are in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the beds we sleep in. While it is a given that we all will be continuously exposed to bacteria, having a well-considered strategy to curtail the spread of disease can dramatically decrease the risk that we, our families, and our patients are needlessly exposed to potentially life-threatening organisms.

We all know we are to wash our hands on the way in, and out, of patients’ rooms. This practice is our front line of defense against the spread of numerous potentially lethal diseases. Yet, many clinicians, as well as ancillary hospital personnel, repeatedly fail to abide by this rule, thinking that ‘this one time won’t hurt anything.’ Whether it’s the nurse who rushes into a patient’s room to stop a beeping IV pole or the doctor who eyes a family member in the room and makes a beeline to discuss the discharge plan, all of us have been guilty of entering or leaving a patient’s room without following appropriate infection control standards.

Or, how many times have you followed the protocol meticulously, at least initially, and removed your gown and gloves and washed your hands on your way out the door when the patient remembers another question, or asks you to hand him something that leads to more contact with him or his surroundings? You already washed your hands once, so must you really do it again? After all, what is the likelihood that you pick up (or pass along) any germs anyway? Sometimes, more than we realize. Something as simple as handing a patient his nurses’ call button can expose us to enough C. difficile spores to cause infection in us or others we come into contact with unwittingly. So wash those hands, and wash them again if you touch anything in a patient’s room, even if it is not the patient himself.

Direct observation (AKA “Secret Santas”) can provide invaluable information about adherence to hand hygiene among health care workers and providing feedback is key. This can be unit based, group based, and even provider based. Once collected, this information should be used to drive changes in behavior, which could be punitive or positive; each hospital should decide how to best use its data.

Visitor contact is another important issue and not everyone agrees on how to enforce, or whether to even try to enforce, infection control procedures. The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) has several helpful pocket guidelines to address this and other infection control issues. For instance, the society recommends that hospitals consider adopting guidelines to minimize horizontal transmission by visitors, though these guidelines should be feasible to enforce. Factors such as the specific organism and its potential to cause harm are important to consider when developing these guidelines. For instance, the spouse of a patient admitted with influenza has likely already been exposed, and postexposure prophylaxis may be more feasible to her than wearing an uncomfortable mask during an 8-hour hospital visit.

A pharmacy stewardship program is another invaluable infection control tool. With this model, a group of pharmacists, under the direction of an infectious disease specialist, reviews culture results daily and makes recommendations to the physician regarding narrowing antibiotic coverage. I greatly appreciate receiving calls to notify me that the final culture results are in long before I would have actually seen them myself. This allows me to adjust antibiotics in a timely fashion, thus reducing the emergence of drug-resistant organisms or precipitating an unnecessary case of C. difficile.

In addition, written guidelines should be established for indwelling catheters, both urinary and venous. The indication for continued use should be reassessed daily; a computer alert that requires a response is very helpful, as is a call from the friendly floor nurse asking, “Does this patient really still need his catheter?”

Infection control is everyone’s responsibility and we all need to work together toward this common goal.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Big things come in small packages, very small – so small they may even be invisible to the naked eye. Take for instance a huge infection causing multiorgan system failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, even septic shock refractory to high-dose pressors. This catastrophe may be the end result of exposure to tiny pathogenic microbes that can take down an otherwise healthy 300-pound man, tout suite!

Microorganisms are everywhere. We can’t live without them, but we can’t live with certain ones either. Unless you live in a bubble you are going to be exposed to countless bacteria each and every day. They are in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the beds we sleep in. While it is a given that we all will be continuously exposed to bacteria, having a well-considered strategy to curtail the spread of disease can dramatically decrease the risk that we, our families, and our patients are needlessly exposed to potentially life-threatening organisms.

We all know we are to wash our hands on the way in, and out, of patients’ rooms. This practice is our front line of defense against the spread of numerous potentially lethal diseases. Yet, many clinicians, as well as ancillary hospital personnel, repeatedly fail to abide by this rule, thinking that ‘this one time won’t hurt anything.’ Whether it’s the nurse who rushes into a patient’s room to stop a beeping IV pole or the doctor who eyes a family member in the room and makes a beeline to discuss the discharge plan, all of us have been guilty of entering or leaving a patient’s room without following appropriate infection control standards.

Or, how many times have you followed the protocol meticulously, at least initially, and removed your gown and gloves and washed your hands on your way out the door when the patient remembers another question, or asks you to hand him something that leads to more contact with him or his surroundings? You already washed your hands once, so must you really do it again? After all, what is the likelihood that you pick up (or pass along) any germs anyway? Sometimes, more than we realize. Something as simple as handing a patient his nurses’ call button can expose us to enough C. difficile spores to cause infection in us or others we come into contact with unwittingly. So wash those hands, and wash them again if you touch anything in a patient’s room, even if it is not the patient himself.

Direct observation (AKA “Secret Santas”) can provide invaluable information about adherence to hand hygiene among health care workers and providing feedback is key. This can be unit based, group based, and even provider based. Once collected, this information should be used to drive changes in behavior, which could be punitive or positive; each hospital should decide how to best use its data.

Visitor contact is another important issue and not everyone agrees on how to enforce, or whether to even try to enforce, infection control procedures. The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) has several helpful pocket guidelines to address this and other infection control issues. For instance, the society recommends that hospitals consider adopting guidelines to minimize horizontal transmission by visitors, though these guidelines should be feasible to enforce. Factors such as the specific organism and its potential to cause harm are important to consider when developing these guidelines. For instance, the spouse of a patient admitted with influenza has likely already been exposed, and postexposure prophylaxis may be more feasible to her than wearing an uncomfortable mask during an 8-hour hospital visit.

A pharmacy stewardship program is another invaluable infection control tool. With this model, a group of pharmacists, under the direction of an infectious disease specialist, reviews culture results daily and makes recommendations to the physician regarding narrowing antibiotic coverage. I greatly appreciate receiving calls to notify me that the final culture results are in long before I would have actually seen them myself. This allows me to adjust antibiotics in a timely fashion, thus reducing the emergence of drug-resistant organisms or precipitating an unnecessary case of C. difficile.

In addition, written guidelines should be established for indwelling catheters, both urinary and venous. The indication for continued use should be reassessed daily; a computer alert that requires a response is very helpful, as is a call from the friendly floor nurse asking, “Does this patient really still need his catheter?”

Infection control is everyone’s responsibility and we all need to work together toward this common goal.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Big things come in small packages, very small – so small they may even be invisible to the naked eye. Take for instance a huge infection causing multiorgan system failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, even septic shock refractory to high-dose pressors. This catastrophe may be the end result of exposure to tiny pathogenic microbes that can take down an otherwise healthy 300-pound man, tout suite!

Microorganisms are everywhere. We can’t live without them, but we can’t live with certain ones either. Unless you live in a bubble you are going to be exposed to countless bacteria each and every day. They are in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the beds we sleep in. While it is a given that we all will be continuously exposed to bacteria, having a well-considered strategy to curtail the spread of disease can dramatically decrease the risk that we, our families, and our patients are needlessly exposed to potentially life-threatening organisms.

We all know we are to wash our hands on the way in, and out, of patients’ rooms. This practice is our front line of defense against the spread of numerous potentially lethal diseases. Yet, many clinicians, as well as ancillary hospital personnel, repeatedly fail to abide by this rule, thinking that ‘this one time won’t hurt anything.’ Whether it’s the nurse who rushes into a patient’s room to stop a beeping IV pole or the doctor who eyes a family member in the room and makes a beeline to discuss the discharge plan, all of us have been guilty of entering or leaving a patient’s room without following appropriate infection control standards.

Or, how many times have you followed the protocol meticulously, at least initially, and removed your gown and gloves and washed your hands on your way out the door when the patient remembers another question, or asks you to hand him something that leads to more contact with him or his surroundings? You already washed your hands once, so must you really do it again? After all, what is the likelihood that you pick up (or pass along) any germs anyway? Sometimes, more than we realize. Something as simple as handing a patient his nurses’ call button can expose us to enough C. difficile spores to cause infection in us or others we come into contact with unwittingly. So wash those hands, and wash them again if you touch anything in a patient’s room, even if it is not the patient himself.

Direct observation (AKA “Secret Santas”) can provide invaluable information about adherence to hand hygiene among health care workers and providing feedback is key. This can be unit based, group based, and even provider based. Once collected, this information should be used to drive changes in behavior, which could be punitive or positive; each hospital should decide how to best use its data.

Visitor contact is another important issue and not everyone agrees on how to enforce, or whether to even try to enforce, infection control procedures. The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) has several helpful pocket guidelines to address this and other infection control issues. For instance, the society recommends that hospitals consider adopting guidelines to minimize horizontal transmission by visitors, though these guidelines should be feasible to enforce. Factors such as the specific organism and its potential to cause harm are important to consider when developing these guidelines. For instance, the spouse of a patient admitted with influenza has likely already been exposed, and postexposure prophylaxis may be more feasible to her than wearing an uncomfortable mask during an 8-hour hospital visit.

A pharmacy stewardship program is another invaluable infection control tool. With this model, a group of pharmacists, under the direction of an infectious disease specialist, reviews culture results daily and makes recommendations to the physician regarding narrowing antibiotic coverage. I greatly appreciate receiving calls to notify me that the final culture results are in long before I would have actually seen them myself. This allows me to adjust antibiotics in a timely fashion, thus reducing the emergence of drug-resistant organisms or precipitating an unnecessary case of C. difficile.

In addition, written guidelines should be established for indwelling catheters, both urinary and venous. The indication for continued use should be reassessed daily; a computer alert that requires a response is very helpful, as is a call from the friendly floor nurse asking, “Does this patient really still need his catheter?”

Infection control is everyone’s responsibility and we all need to work together toward this common goal.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

Manufacturer issues new reprocessing instructions for ED-3490TK video duodenoscope

PENTAX, the manufacturer of the ED-3490TK video duodenoscope, has issued updated validated manual reprocessing instructions to replace those provided in the original device labeling in response to a Food and Drug Administration Safety Communication released last February concerning the design of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) duodenoscopes and the risk of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

The FDA has reviewed these updated reprocessing instructions and recommends that staff be trained to implement them as soon as possible. Several changes have been made to the protocol for precleaning, manual cleaning, and high-level disinfection that the FDA found to be adequate.

Olympus, the manufacturer of the TJF-Q180V duodenoscope has also issued updated manual reprocessing instructions.

In February 2015, the FDA first announced that the agency had received reports of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP with duodenoscopes that had been cleaned and disinfected properly (according to manufacturer instructions) and determined that the “complex design of ERCP endoscopes (also called duodenoscopes) may impede effective reprocessing.”

Since then, the FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers to revise their manual reprocessing instructions to devise standard procedures to eliminate the risk of spreading infection between patients and better survey any contamination of the duodenoscopes.

The American Gastroenterological Association's Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with the FDA and device manufacturers to develop a path forward with zero device-associated infections.

Adverse events associated with duodenoscopes should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch.

PENTAX, the manufacturer of the ED-3490TK video duodenoscope, has issued updated validated manual reprocessing instructions to replace those provided in the original device labeling in response to a Food and Drug Administration Safety Communication released last February concerning the design of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) duodenoscopes and the risk of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

The FDA has reviewed these updated reprocessing instructions and recommends that staff be trained to implement them as soon as possible. Several changes have been made to the protocol for precleaning, manual cleaning, and high-level disinfection that the FDA found to be adequate.

Olympus, the manufacturer of the TJF-Q180V duodenoscope has also issued updated manual reprocessing instructions.

In February 2015, the FDA first announced that the agency had received reports of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP with duodenoscopes that had been cleaned and disinfected properly (according to manufacturer instructions) and determined that the “complex design of ERCP endoscopes (also called duodenoscopes) may impede effective reprocessing.”

Since then, the FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers to revise their manual reprocessing instructions to devise standard procedures to eliminate the risk of spreading infection between patients and better survey any contamination of the duodenoscopes.

The American Gastroenterological Association's Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with the FDA and device manufacturers to develop a path forward with zero device-associated infections.

Adverse events associated with duodenoscopes should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch.

PENTAX, the manufacturer of the ED-3490TK video duodenoscope, has issued updated validated manual reprocessing instructions to replace those provided in the original device labeling in response to a Food and Drug Administration Safety Communication released last February concerning the design of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) duodenoscopes and the risk of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

The FDA has reviewed these updated reprocessing instructions and recommends that staff be trained to implement them as soon as possible. Several changes have been made to the protocol for precleaning, manual cleaning, and high-level disinfection that the FDA found to be adequate.

Olympus, the manufacturer of the TJF-Q180V duodenoscope has also issued updated manual reprocessing instructions.

In February 2015, the FDA first announced that the agency had received reports of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients who had undergone ERCP with duodenoscopes that had been cleaned and disinfected properly (according to manufacturer instructions) and determined that the “complex design of ERCP endoscopes (also called duodenoscopes) may impede effective reprocessing.”

Since then, the FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers to revise their manual reprocessing instructions to devise standard procedures to eliminate the risk of spreading infection between patients and better survey any contamination of the duodenoscopes.

The American Gastroenterological Association's Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with the FDA and device manufacturers to develop a path forward with zero device-associated infections.

Adverse events associated with duodenoscopes should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch.

Behavioral interventions cut inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

Two behavioral interventions for primary care clinicians cut the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections significantly, according to a report published online Feb. 9 in JAMA.

Compared with a control condition that included clinician education, the two interventions reduced inappropriate prescribing by 5.2% and 7.0%, respectively.

“We believe these effect sizes are clinically significant, especially when measured against control clinicians who were motivated to join a trial, knew they were being monitored, and who had relatively low antibiotic prescribing rates at baseline,” said Daniella Meeker, Ph.D., of the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates.

In a cluster-randomized trial involving 248 clinicians at 47 primary care practices in Boston and Los Angeles, the investigators designed three interventions and tested various combinations of them against a control condition during an 18-month period. The number of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions given during this intervention period was then compared with that during a baseline period, the 18 months preceding the intervention.

The analysis included 14,753 patient visits for acute respiratory tract infections during the baseline period and 16,959 visits during the intervention period.

The first behavioral intervention, termed “accountable justification,” used an alert each time a clinician prescribed an antibiotic in a patient’s electronic health record – a prompt asking for an explicit justification for doing so. That approach was based on the hope that to preserve their reputations, clinicians would tailor their behavior to fall in line with norms followed by their peers and recommended in clinical guidelines.

The second intervention, “peer comparison,” used monthly e-mails to inform clinicians whether or not they were “top performers” (within the lowest decile) for inappropriate prescribing in their geographical region. The emails included the number and proportion of antibiotic prescriptions they wrote inappropriately for acute upper respiratory tract infections, compared with the proportion written by top performers.

The mean rate of antibiotic prescribing decreased during the intervention in all the study groups, including the control group, which showed an absolute decrease of 11% (from 24.1% to 13.1%). The absolute decrease was significantly greater, at 18.1%, in the accountable justification group (from 23.2% to 5.2%) and at 16.3% in the peer comparison group (from 19.9% to 3.7%), Dr. Meeker and her associates said (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70). The rate of return visits for possible bacterial infections within 30 days of the index visit was used as a measure of safety for withholding antibiotic prescriptions. This rate was 0.4% in the control group. The only intervention group that showed a “modestly higher” rate of return visits was the one that used both the accountable justification and the peer comparison interventions together, for which the rate of return visits was 1.4%.

The study was supported by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Aging, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the University of Southern California’s Medical Information Network for Experimental Research, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Meeker and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Even though the reductions in inappropriate prescribing in this study might be considered modest, they were real, important, and potentially sustainable.

Baseline levels of inappropriate prescribing were already low to start with among the study participants, which suggests that they already were judicious prescribers in relation to national averages. In addition, the control group participants knew their antibiotic prescribing was being monitored and may have decreased it, consciously or unconsciously. Both of these factors may have blunted the potential effectiveness of the interventions.

Dr. Jeffrey S. Gerber is in the division of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gerber made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Meeker’s report (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:558-9).

Even though the reductions in inappropriate prescribing in this study might be considered modest, they were real, important, and potentially sustainable.

Baseline levels of inappropriate prescribing were already low to start with among the study participants, which suggests that they already were judicious prescribers in relation to national averages. In addition, the control group participants knew their antibiotic prescribing was being monitored and may have decreased it, consciously or unconsciously. Both of these factors may have blunted the potential effectiveness of the interventions.

Dr. Jeffrey S. Gerber is in the division of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gerber made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Meeker’s report (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:558-9).

Even though the reductions in inappropriate prescribing in this study might be considered modest, they were real, important, and potentially sustainable.

Baseline levels of inappropriate prescribing were already low to start with among the study participants, which suggests that they already were judicious prescribers in relation to national averages. In addition, the control group participants knew their antibiotic prescribing was being monitored and may have decreased it, consciously or unconsciously. Both of these factors may have blunted the potential effectiveness of the interventions.

Dr. Jeffrey S. Gerber is in the division of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and in the department of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gerber made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Meeker’s report (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:558-9).

Two behavioral interventions for primary care clinicians cut the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections significantly, according to a report published online Feb. 9 in JAMA.

Compared with a control condition that included clinician education, the two interventions reduced inappropriate prescribing by 5.2% and 7.0%, respectively.

“We believe these effect sizes are clinically significant, especially when measured against control clinicians who were motivated to join a trial, knew they were being monitored, and who had relatively low antibiotic prescribing rates at baseline,” said Daniella Meeker, Ph.D., of the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates.

In a cluster-randomized trial involving 248 clinicians at 47 primary care practices in Boston and Los Angeles, the investigators designed three interventions and tested various combinations of them against a control condition during an 18-month period. The number of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions given during this intervention period was then compared with that during a baseline period, the 18 months preceding the intervention.

The analysis included 14,753 patient visits for acute respiratory tract infections during the baseline period and 16,959 visits during the intervention period.

The first behavioral intervention, termed “accountable justification,” used an alert each time a clinician prescribed an antibiotic in a patient’s electronic health record – a prompt asking for an explicit justification for doing so. That approach was based on the hope that to preserve their reputations, clinicians would tailor their behavior to fall in line with norms followed by their peers and recommended in clinical guidelines.

The second intervention, “peer comparison,” used monthly e-mails to inform clinicians whether or not they were “top performers” (within the lowest decile) for inappropriate prescribing in their geographical region. The emails included the number and proportion of antibiotic prescriptions they wrote inappropriately for acute upper respiratory tract infections, compared with the proportion written by top performers.

The mean rate of antibiotic prescribing decreased during the intervention in all the study groups, including the control group, which showed an absolute decrease of 11% (from 24.1% to 13.1%). The absolute decrease was significantly greater, at 18.1%, in the accountable justification group (from 23.2% to 5.2%) and at 16.3% in the peer comparison group (from 19.9% to 3.7%), Dr. Meeker and her associates said (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70). The rate of return visits for possible bacterial infections within 30 days of the index visit was used as a measure of safety for withholding antibiotic prescriptions. This rate was 0.4% in the control group. The only intervention group that showed a “modestly higher” rate of return visits was the one that used both the accountable justification and the peer comparison interventions together, for which the rate of return visits was 1.4%.

The study was supported by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Aging, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the University of Southern California’s Medical Information Network for Experimental Research, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Meeker and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Two behavioral interventions for primary care clinicians cut the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections significantly, according to a report published online Feb. 9 in JAMA.

Compared with a control condition that included clinician education, the two interventions reduced inappropriate prescribing by 5.2% and 7.0%, respectively.

“We believe these effect sizes are clinically significant, especially when measured against control clinicians who were motivated to join a trial, knew they were being monitored, and who had relatively low antibiotic prescribing rates at baseline,” said Daniella Meeker, Ph.D., of the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and her associates.

In a cluster-randomized trial involving 248 clinicians at 47 primary care practices in Boston and Los Angeles, the investigators designed three interventions and tested various combinations of them against a control condition during an 18-month period. The number of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions given during this intervention period was then compared with that during a baseline period, the 18 months preceding the intervention.

The analysis included 14,753 patient visits for acute respiratory tract infections during the baseline period and 16,959 visits during the intervention period.

The first behavioral intervention, termed “accountable justification,” used an alert each time a clinician prescribed an antibiotic in a patient’s electronic health record – a prompt asking for an explicit justification for doing so. That approach was based on the hope that to preserve their reputations, clinicians would tailor their behavior to fall in line with norms followed by their peers and recommended in clinical guidelines.

The second intervention, “peer comparison,” used monthly e-mails to inform clinicians whether or not they were “top performers” (within the lowest decile) for inappropriate prescribing in their geographical region. The emails included the number and proportion of antibiotic prescriptions they wrote inappropriately for acute upper respiratory tract infections, compared with the proportion written by top performers.