User login

SecA inhibitors show in vitro efficacy against MRSA

A promising approach to treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections may lie in small molecules that target SecA, an indispensable ATPase of the general protein translocation machinery present in bacteria, according to Jinshan Jin, Ph.D.

Dr. Jin and his coinvestigators at Georgia State University developed small molecule analogs of Rose Bengal that target SecA. In in vitro studies, the analogs had potent antimicrobial activities, reduced the secretion of toxins, and overcame the effect of efflux pumps, which are responsible for multi-drug resistance. The ability to inhibit virulence factor secretion is something most currently available and commonly prescribed antibiotics are unable to do, making small molecule treatments an attractive option if such treatments are proven effective in vivo. The small molecule inhibitors reduced the secretion of three toxins from S. aureus and exerted potent bacteriostatic effects against three MRSA strains, the researchers reported (Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Vol. 23; 2015, 7061–68). “Our best inhibitor SCA-50 showed potent concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against MRSA Mu50 strain and very importantly, 2–60 fold more potent inhibitory effect on MRSA Mu50 than all the commonly used antibiotics including vancomycin, which is considered the last resort option in treating MRSA-related infections.”

“The results obtained demonstrated an important proof of concept [that] targeting SecA could achieve antimicrobial effect through three mechanisms, which are not seen with any single class of antimicrobial agents,” Dr. Jin and his coauthors wrote.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Georgia State University. Dr. Jin is now with the National Center of Toxicological Research, in Jefferson, Ariz.

A promising approach to treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections may lie in small molecules that target SecA, an indispensable ATPase of the general protein translocation machinery present in bacteria, according to Jinshan Jin, Ph.D.

Dr. Jin and his coinvestigators at Georgia State University developed small molecule analogs of Rose Bengal that target SecA. In in vitro studies, the analogs had potent antimicrobial activities, reduced the secretion of toxins, and overcame the effect of efflux pumps, which are responsible for multi-drug resistance. The ability to inhibit virulence factor secretion is something most currently available and commonly prescribed antibiotics are unable to do, making small molecule treatments an attractive option if such treatments are proven effective in vivo. The small molecule inhibitors reduced the secretion of three toxins from S. aureus and exerted potent bacteriostatic effects against three MRSA strains, the researchers reported (Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Vol. 23; 2015, 7061–68). “Our best inhibitor SCA-50 showed potent concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against MRSA Mu50 strain and very importantly, 2–60 fold more potent inhibitory effect on MRSA Mu50 than all the commonly used antibiotics including vancomycin, which is considered the last resort option in treating MRSA-related infections.”

“The results obtained demonstrated an important proof of concept [that] targeting SecA could achieve antimicrobial effect through three mechanisms, which are not seen with any single class of antimicrobial agents,” Dr. Jin and his coauthors wrote.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Georgia State University. Dr. Jin is now with the National Center of Toxicological Research, in Jefferson, Ariz.

A promising approach to treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections may lie in small molecules that target SecA, an indispensable ATPase of the general protein translocation machinery present in bacteria, according to Jinshan Jin, Ph.D.

Dr. Jin and his coinvestigators at Georgia State University developed small molecule analogs of Rose Bengal that target SecA. In in vitro studies, the analogs had potent antimicrobial activities, reduced the secretion of toxins, and overcame the effect of efflux pumps, which are responsible for multi-drug resistance. The ability to inhibit virulence factor secretion is something most currently available and commonly prescribed antibiotics are unable to do, making small molecule treatments an attractive option if such treatments are proven effective in vivo. The small molecule inhibitors reduced the secretion of three toxins from S. aureus and exerted potent bacteriostatic effects against three MRSA strains, the researchers reported (Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Vol. 23; 2015, 7061–68). “Our best inhibitor SCA-50 showed potent concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against MRSA Mu50 strain and very importantly, 2–60 fold more potent inhibitory effect on MRSA Mu50 than all the commonly used antibiotics including vancomycin, which is considered the last resort option in treating MRSA-related infections.”

“The results obtained demonstrated an important proof of concept [that] targeting SecA could achieve antimicrobial effect through three mechanisms, which are not seen with any single class of antimicrobial agents,” Dr. Jin and his coauthors wrote.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and by Georgia State University. Dr. Jin is now with the National Center of Toxicological Research, in Jefferson, Ariz.

FROM BIOORGANIC & MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY

Patients may safely self-administer long-term IV antibiotics

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Uninsured patients can be trained to safely and efficiently self-administer long-term intravenous antibiotics, according to a 4-year outcomes study published in PLOS Medicine.

Between 2010 and 2013, 994 uninsured patients at Parkland Hospital in Dallas were enrolled in a self-administered outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (S-OPAT) program, and 224 insured patients were discharged to a health care–administered OPAT program. Patients in the S-OPAT group were trained to self-administer intravenous antimicrobials, tested for their ability to treat themselves before discharge, and then monitored by weekly visits to the S-OPAT outpatient clinic. The 224 insured patients in the H-OPAT program had antibiotics administered by a health care worker.

A research team led by Dr. Kavita Bhavan of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, estimated the effect of S-OPAT versus H-OPAT on 30-day all-cause readmission and 1-year all-cause mortality after controlling for selection bias with a propensity score developed using baseline clinical and sociodemographic information collected from the patients.

The 30-day readmission rate was 47% lower in the S-OPAT group than in the H-OPAT group, and the 1-year mortality rate did not differ significantly between the two groups. Because the S-OPAT program resulted in patients spending fewer days having inpatient infusions, 27,666 inpatient days were avoided over the study period.

Thus, S-OPAT was associated with similar or better outcomes than H-OPAT, meaning S-OPAT may be an acceptable model of treatment for uninsured, medically stable patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antimicrobials at home.

Read the full study online at PLOS Medicine (PLoS Med. 2015 Dec 15;12[12]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001922).

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Delayed response predicts need for extended antibiotics for inpatients with low-risk, gram-negative bacteremias

Antibiotic therapy for 7 days or less may be just as effective as longer courses of antibiotics for select inpatients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia from urinary infections, based on a retrospective, single-center analysis by researchers at Maimonides Medical Center in New York.

Hospitalized patients whose temperatures returned to levels below 100.4º F within 72 hours of starting therapy appeared to do well on short-course (7 days or less) antibiotic therapy, Siddharth Swamy, Pharm.D., and his colleagues reported in a study in Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice posted online Dec. 30, 2015. However, increased clinical failures were noted in patients with a delayed response to therapy, indicating that duration of therapy needs to be individualized for each patient.

The researchers reviewed 178 eligible cases of gram-negative bacteremia. The most common source of bacteremia was the urinary tract (53%), followed by catheters (14%), and unknown sources (14%).

Patients were treated with antibiotics for either 7 days or less (42 patients), 8-14 days (100 patients), or more than 14 days (36 patients). The patients in the study were comparable, with the exception of a higher percentage of patients in the short-course antibiotic group who no longer had temperatures above 100.4º F within 72 hours of initiating therapy. The respective percentage of patients who had defervesced in 72 hours or less was 79% for 7 days or less of therapy, 69% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 36% for more than 14 days of therapy (P = .0002). Overall clinical response rates were 79% for 7 days or less of antibiotics, 89% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 81% for more than 14 days of therapy. Microbiologic cure rates were 83%, 89, and 92%, respectively; the differences were nonsignificant.

However, persisting fever predicted clinical response: Among patients who defervesced after 72 hours, the short-course treatment group had a significantly decreased clinical response rate, compared with intermediate- and long-course treatment groups (11%, 65%, 70%, respectively; P = .03).

The most common infectious pathogens were Escherichia coli (46%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22%); most cases were low-inocula bacteremias and were related to urinary tract infections in 53% of the cases. Thus, the findings “are not necessarily applicable to high-inocula bacteremias, nonlactose-fermenting gram-negative organisms, or multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms,” the researchers wrote.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Antibiotic therapy for 7 days or less may be just as effective as longer courses of antibiotics for select inpatients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia from urinary infections, based on a retrospective, single-center analysis by researchers at Maimonides Medical Center in New York.

Hospitalized patients whose temperatures returned to levels below 100.4º F within 72 hours of starting therapy appeared to do well on short-course (7 days or less) antibiotic therapy, Siddharth Swamy, Pharm.D., and his colleagues reported in a study in Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice posted online Dec. 30, 2015. However, increased clinical failures were noted in patients with a delayed response to therapy, indicating that duration of therapy needs to be individualized for each patient.

The researchers reviewed 178 eligible cases of gram-negative bacteremia. The most common source of bacteremia was the urinary tract (53%), followed by catheters (14%), and unknown sources (14%).

Patients were treated with antibiotics for either 7 days or less (42 patients), 8-14 days (100 patients), or more than 14 days (36 patients). The patients in the study were comparable, with the exception of a higher percentage of patients in the short-course antibiotic group who no longer had temperatures above 100.4º F within 72 hours of initiating therapy. The respective percentage of patients who had defervesced in 72 hours or less was 79% for 7 days or less of therapy, 69% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 36% for more than 14 days of therapy (P = .0002). Overall clinical response rates were 79% for 7 days or less of antibiotics, 89% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 81% for more than 14 days of therapy. Microbiologic cure rates were 83%, 89, and 92%, respectively; the differences were nonsignificant.

However, persisting fever predicted clinical response: Among patients who defervesced after 72 hours, the short-course treatment group had a significantly decreased clinical response rate, compared with intermediate- and long-course treatment groups (11%, 65%, 70%, respectively; P = .03).

The most common infectious pathogens were Escherichia coli (46%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22%); most cases were low-inocula bacteremias and were related to urinary tract infections in 53% of the cases. Thus, the findings “are not necessarily applicable to high-inocula bacteremias, nonlactose-fermenting gram-negative organisms, or multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms,” the researchers wrote.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Antibiotic therapy for 7 days or less may be just as effective as longer courses of antibiotics for select inpatients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia from urinary infections, based on a retrospective, single-center analysis by researchers at Maimonides Medical Center in New York.

Hospitalized patients whose temperatures returned to levels below 100.4º F within 72 hours of starting therapy appeared to do well on short-course (7 days or less) antibiotic therapy, Siddharth Swamy, Pharm.D., and his colleagues reported in a study in Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice posted online Dec. 30, 2015. However, increased clinical failures were noted in patients with a delayed response to therapy, indicating that duration of therapy needs to be individualized for each patient.

The researchers reviewed 178 eligible cases of gram-negative bacteremia. The most common source of bacteremia was the urinary tract (53%), followed by catheters (14%), and unknown sources (14%).

Patients were treated with antibiotics for either 7 days or less (42 patients), 8-14 days (100 patients), or more than 14 days (36 patients). The patients in the study were comparable, with the exception of a higher percentage of patients in the short-course antibiotic group who no longer had temperatures above 100.4º F within 72 hours of initiating therapy. The respective percentage of patients who had defervesced in 72 hours or less was 79% for 7 days or less of therapy, 69% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 36% for more than 14 days of therapy (P = .0002). Overall clinical response rates were 79% for 7 days or less of antibiotics, 89% for 8-14 days of therapy, and 81% for more than 14 days of therapy. Microbiologic cure rates were 83%, 89, and 92%, respectively; the differences were nonsignificant.

However, persisting fever predicted clinical response: Among patients who defervesced after 72 hours, the short-course treatment group had a significantly decreased clinical response rate, compared with intermediate- and long-course treatment groups (11%, 65%, 70%, respectively; P = .03).

The most common infectious pathogens were Escherichia coli (46%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22%); most cases were low-inocula bacteremias and were related to urinary tract infections in 53% of the cases. Thus, the findings “are not necessarily applicable to high-inocula bacteremias, nonlactose-fermenting gram-negative organisms, or multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms,” the researchers wrote.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM INFECTIOUS DISEASES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Antibiotic therapy for 7 days or less may be just as effective as longer courses of antibiotics for select inpatients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia due to urinary infections.

Major finding: Among inpatients who defervesced after 72 hours, the short-course treatment group had a significantly decreased clinical response rate compared with intermediate- and long-course treatment groups (11%, 65%, 70%, respectively, P = 0.03).

Data source: Single-center, retrospective, case-cohort review of 178 cases.

Disclosures: The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

White House launches new plan to combat multidrug-resistant TB

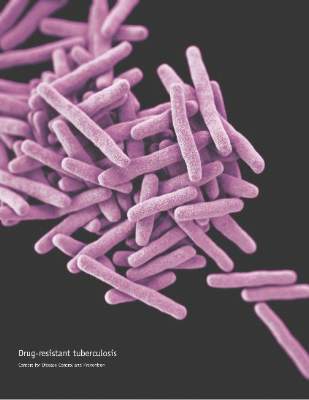

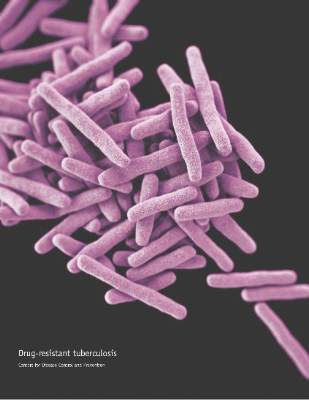

The Obama administration has announced a new action plan to combat the rise of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

The plan, published Dec. 22, outlines three primary goals to accomplish between 2016 and 2020: strengthening domestic capacity to treat the disease, improving international ability and collaboration, and accelerating research and treatment of MDR-TB.

To strengthen state and local capacity to prevent transmission of TB, the action plan proposes improving surge capacity for rapid response to individual patients, patient clusters, and larger outbreaks of drug-resistant TB, as well as advancing the treatment of latent TB infection and disease among vulnerable populations.

Disease surveillance will be upgraded to “gather, store, analyze, and report electronic data on drug-resistant TB.” As part of the effort, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will increase its capacity to use “whole-genome sequencing to elucidate paths of transmission, identify recent transmission, and identify emerging patterns of resistance,” according to the action plan.

Taken with other preventive activities, the measures are estimated to result in a 15% reduction in newly diagnosed MDR-TB cases by 2020, as specified in the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.

Additionally, the U.S. government will work with partners including the World Health Organization and the Stop TB Partnership to support countries in developing new approaches to MDR-TB. The focus is expected to initiate treatment for an additional 200,000 people with MDR-TB during 2015-2019; an estimated 360,000 people are currently treated under the U.S. government’s Global TB Strategy. The action plan also aims to improve access to patient-centered diagnostic and treatment services in countries with limited health care resources.

Developing a TB vaccine is a key initiative. The plan details that the National Institutes of Health and the CDC will focus on expanding the dialogue among basic scientists, funders, and vaccine developers to identify strategies for vaccine development and preventive drugs.

The plan also urges focused research into the discovery of biological markers that indicate early response to therapy or protection against TB.

Pulmonologist Daniel R. Ouellette of Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said “the three goals are certainly worthy,” but the plan does not address the budgetary measures to be taken to increase domestic capacity to combat TB nor does it explain where resources will be found to encourage the development of new medications.

“How much money are we willing to spend in addition to what we spend now in treating general TB? he asked in an interview. “How are we going to incentivize industry to develop new drugs? It all sounds really good, but all of this is going to cost money. Where are the dollars that go with that?” said Dr. Ouellette, who is chair of the Guideline Oversight Committee for CHEST (the American College of Chest Physicians).

The national action plan states that all activities noted will be subject to budgetary constraints and other approvals, including the “weighing of priorities and available resources by the administration in formulating its annual budget and by Congress in legislating appropriations.”

TB causes the deaths of more than 1.5 million people worldwide annually, according to White House data. Nearly one-third of the world’s population is thought to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; each year, more than 9.5 million develop active TB and about 480,000 people develop MDR-TB. Fewer than 20% with MDR-TB receive appropriate therapy, and less than half are effectively treated.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Obama administration has announced a new action plan to combat the rise of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

The plan, published Dec. 22, outlines three primary goals to accomplish between 2016 and 2020: strengthening domestic capacity to treat the disease, improving international ability and collaboration, and accelerating research and treatment of MDR-TB.

To strengthen state and local capacity to prevent transmission of TB, the action plan proposes improving surge capacity for rapid response to individual patients, patient clusters, and larger outbreaks of drug-resistant TB, as well as advancing the treatment of latent TB infection and disease among vulnerable populations.

Disease surveillance will be upgraded to “gather, store, analyze, and report electronic data on drug-resistant TB.” As part of the effort, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will increase its capacity to use “whole-genome sequencing to elucidate paths of transmission, identify recent transmission, and identify emerging patterns of resistance,” according to the action plan.

Taken with other preventive activities, the measures are estimated to result in a 15% reduction in newly diagnosed MDR-TB cases by 2020, as specified in the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.

Additionally, the U.S. government will work with partners including the World Health Organization and the Stop TB Partnership to support countries in developing new approaches to MDR-TB. The focus is expected to initiate treatment for an additional 200,000 people with MDR-TB during 2015-2019; an estimated 360,000 people are currently treated under the U.S. government’s Global TB Strategy. The action plan also aims to improve access to patient-centered diagnostic and treatment services in countries with limited health care resources.

Developing a TB vaccine is a key initiative. The plan details that the National Institutes of Health and the CDC will focus on expanding the dialogue among basic scientists, funders, and vaccine developers to identify strategies for vaccine development and preventive drugs.

The plan also urges focused research into the discovery of biological markers that indicate early response to therapy or protection against TB.

Pulmonologist Daniel R. Ouellette of Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said “the three goals are certainly worthy,” but the plan does not address the budgetary measures to be taken to increase domestic capacity to combat TB nor does it explain where resources will be found to encourage the development of new medications.

“How much money are we willing to spend in addition to what we spend now in treating general TB? he asked in an interview. “How are we going to incentivize industry to develop new drugs? It all sounds really good, but all of this is going to cost money. Where are the dollars that go with that?” said Dr. Ouellette, who is chair of the Guideline Oversight Committee for CHEST (the American College of Chest Physicians).

The national action plan states that all activities noted will be subject to budgetary constraints and other approvals, including the “weighing of priorities and available resources by the administration in formulating its annual budget and by Congress in legislating appropriations.”

TB causes the deaths of more than 1.5 million people worldwide annually, according to White House data. Nearly one-third of the world’s population is thought to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; each year, more than 9.5 million develop active TB and about 480,000 people develop MDR-TB. Fewer than 20% with MDR-TB receive appropriate therapy, and less than half are effectively treated.

On Twitter @legal_med

The Obama administration has announced a new action plan to combat the rise of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

The plan, published Dec. 22, outlines three primary goals to accomplish between 2016 and 2020: strengthening domestic capacity to treat the disease, improving international ability and collaboration, and accelerating research and treatment of MDR-TB.

To strengthen state and local capacity to prevent transmission of TB, the action plan proposes improving surge capacity for rapid response to individual patients, patient clusters, and larger outbreaks of drug-resistant TB, as well as advancing the treatment of latent TB infection and disease among vulnerable populations.

Disease surveillance will be upgraded to “gather, store, analyze, and report electronic data on drug-resistant TB.” As part of the effort, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will increase its capacity to use “whole-genome sequencing to elucidate paths of transmission, identify recent transmission, and identify emerging patterns of resistance,” according to the action plan.

Taken with other preventive activities, the measures are estimated to result in a 15% reduction in newly diagnosed MDR-TB cases by 2020, as specified in the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.

Additionally, the U.S. government will work with partners including the World Health Organization and the Stop TB Partnership to support countries in developing new approaches to MDR-TB. The focus is expected to initiate treatment for an additional 200,000 people with MDR-TB during 2015-2019; an estimated 360,000 people are currently treated under the U.S. government’s Global TB Strategy. The action plan also aims to improve access to patient-centered diagnostic and treatment services in countries with limited health care resources.

Developing a TB vaccine is a key initiative. The plan details that the National Institutes of Health and the CDC will focus on expanding the dialogue among basic scientists, funders, and vaccine developers to identify strategies for vaccine development and preventive drugs.

The plan also urges focused research into the discovery of biological markers that indicate early response to therapy or protection against TB.

Pulmonologist Daniel R. Ouellette of Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, said “the three goals are certainly worthy,” but the plan does not address the budgetary measures to be taken to increase domestic capacity to combat TB nor does it explain where resources will be found to encourage the development of new medications.

“How much money are we willing to spend in addition to what we spend now in treating general TB? he asked in an interview. “How are we going to incentivize industry to develop new drugs? It all sounds really good, but all of this is going to cost money. Where are the dollars that go with that?” said Dr. Ouellette, who is chair of the Guideline Oversight Committee for CHEST (the American College of Chest Physicians).

The national action plan states that all activities noted will be subject to budgetary constraints and other approvals, including the “weighing of priorities and available resources by the administration in formulating its annual budget and by Congress in legislating appropriations.”

TB causes the deaths of more than 1.5 million people worldwide annually, according to White House data. Nearly one-third of the world’s population is thought to be infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; each year, more than 9.5 million develop active TB and about 480,000 people develop MDR-TB. Fewer than 20% with MDR-TB receive appropriate therapy, and less than half are effectively treated.

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point: A new action plan to combat the rise of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis focuses on strengthening the domestic capacity to treat the MDR-TB, improving international capacity and collaboration to combat the disease, and accelerating research and treatment developments.

Multidrug-resistant TB response boosted by six-drug therapy

Using more than five agents to treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis markedly increases the cure rate by as much as 65%, according to a report published online Dec. 29 in PLOS Medicine.

At present, the World Health Organization recommends a regimen of pyrazinamide plus at least four second-line drugs that are likely to be effective, based on the patient’s previous exposure, background resistance levels in the community, and any drug susceptibility testing results from known cases in contact with the patient. But recent evidence suggested that including even more drugs in the regimen might improve clinical outcomes, said Courtney M. Yuen, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates.

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of data for 1,137 participants in the Preserving Effective Tuberculosis Treatment Study (PETTS), an international prospective cohort study of patients with multidrug-resistant pulmonary TB. These patients were followed for a median of 20 months, undergoing sputum cultures for TB every month. The researchers used time to sputum culture conversion as the indicator of treatment effectiveness.

Receiving at least six potentially effective drugs per day raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 36%, compared with using the recommended five drugs. In addition, for patients receiving at least one untested drug – any antituberculosis agent given empirically, without susceptibility testing – in their five-drug regimen, adding an extra potentially effective drug raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 65%. Even adding an extra untested drug to a five-drug regimen improved the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 33%, Dr. Yuen and her associates said (PLOS Med. 2015 Dec 29. doi:10.1371/pmed.1001932).

“We observed a benefit to receiving a greater number of potentially effective drugs ... as well as an interaction in which the presence of more effective drugs enhanced the benefit of untested drugs. Both of these results add to existing evidence that increasing the number of drugs in multidrug-resistant TB regimens is advantageous,” they noted.

The WHO initially recommended a regimen of four drugs for these patients in 2006, then raised that number to five in 2011. “Our results suggest that treatment might be further fortified by adding additional potentially effective drugs,” the investigators said.

Using more than five agents to treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis markedly increases the cure rate by as much as 65%, according to a report published online Dec. 29 in PLOS Medicine.

At present, the World Health Organization recommends a regimen of pyrazinamide plus at least four second-line drugs that are likely to be effective, based on the patient’s previous exposure, background resistance levels in the community, and any drug susceptibility testing results from known cases in contact with the patient. But recent evidence suggested that including even more drugs in the regimen might improve clinical outcomes, said Courtney M. Yuen, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates.

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of data for 1,137 participants in the Preserving Effective Tuberculosis Treatment Study (PETTS), an international prospective cohort study of patients with multidrug-resistant pulmonary TB. These patients were followed for a median of 20 months, undergoing sputum cultures for TB every month. The researchers used time to sputum culture conversion as the indicator of treatment effectiveness.

Receiving at least six potentially effective drugs per day raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 36%, compared with using the recommended five drugs. In addition, for patients receiving at least one untested drug – any antituberculosis agent given empirically, without susceptibility testing – in their five-drug regimen, adding an extra potentially effective drug raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 65%. Even adding an extra untested drug to a five-drug regimen improved the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 33%, Dr. Yuen and her associates said (PLOS Med. 2015 Dec 29. doi:10.1371/pmed.1001932).

“We observed a benefit to receiving a greater number of potentially effective drugs ... as well as an interaction in which the presence of more effective drugs enhanced the benefit of untested drugs. Both of these results add to existing evidence that increasing the number of drugs in multidrug-resistant TB regimens is advantageous,” they noted.

The WHO initially recommended a regimen of four drugs for these patients in 2006, then raised that number to five in 2011. “Our results suggest that treatment might be further fortified by adding additional potentially effective drugs,” the investigators said.

Using more than five agents to treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis markedly increases the cure rate by as much as 65%, according to a report published online Dec. 29 in PLOS Medicine.

At present, the World Health Organization recommends a regimen of pyrazinamide plus at least four second-line drugs that are likely to be effective, based on the patient’s previous exposure, background resistance levels in the community, and any drug susceptibility testing results from known cases in contact with the patient. But recent evidence suggested that including even more drugs in the regimen might improve clinical outcomes, said Courtney M. Yuen, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates.

The researchers performed a secondary analysis of data for 1,137 participants in the Preserving Effective Tuberculosis Treatment Study (PETTS), an international prospective cohort study of patients with multidrug-resistant pulmonary TB. These patients were followed for a median of 20 months, undergoing sputum cultures for TB every month. The researchers used time to sputum culture conversion as the indicator of treatment effectiveness.

Receiving at least six potentially effective drugs per day raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 36%, compared with using the recommended five drugs. In addition, for patients receiving at least one untested drug – any antituberculosis agent given empirically, without susceptibility testing – in their five-drug regimen, adding an extra potentially effective drug raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 65%. Even adding an extra untested drug to a five-drug regimen improved the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 33%, Dr. Yuen and her associates said (PLOS Med. 2015 Dec 29. doi:10.1371/pmed.1001932).

“We observed a benefit to receiving a greater number of potentially effective drugs ... as well as an interaction in which the presence of more effective drugs enhanced the benefit of untested drugs. Both of these results add to existing evidence that increasing the number of drugs in multidrug-resistant TB regimens is advantageous,” they noted.

The WHO initially recommended a regimen of four drugs for these patients in 2006, then raised that number to five in 2011. “Our results suggest that treatment might be further fortified by adding additional potentially effective drugs,” the investigators said.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Using more than the recommended five drugs to treat multidrug-resistant TB increased the cure rate by as much as 65%.

Major finding: Receiving at least six potentially effective drugs per day raised the likelihood of sputum culture conversion by 36%, compared with using the recommended five drugs.

Data source: A secondary analysis of data regarding 1,137 participants in an international prospective cohort study.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the CDC, the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dr. Yuen and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Tricks for treating C. diff in IBD

ORLANDO – You can confidently treat mild to severe Clostridium difficile infection in persons with inflammatory bowel disease, without disrupting their immunosuppression or other treatments, according to an expert.

“If your patient with IBD needs a fecal transplant for C. diff., you should not be concerned about withholding it,” Dr. Alan C. Moss said during a basic science presentation at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Moss is an associate professor of medicine and the director of translational research at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The first step, after you’ve determined that your patient has a true C. diff. infection, as opposed to having only been colonized by the bacteria, is choosing the best antibiotic. “Unfortunately, almost all IBD patients are excluded from controlled trials of antibiotics in C. diff. infection, so all we really have to go on are retrospective cohort data,” said Dr. Moss.

One such study, uncontrolled for disease severity, showed that a third of 114 inpatients with IBD who had a co-occurring C. diff. infection had higher 30-day readmission rates when treated first with metronidazole, per current standards of care, compared with the remaining two-thirds of patients who were treated first with vancomycin. The metronidazole group also averaged double the length of stays of the vancomycin group (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Sep;58:5054-9 [doi: 10.1128/AAC.02606-13]).

“This suggests that in IBD patients, especially for those who meet criteria for a severe C. diff. infection, vancomycin is the way to go,” Dr. Moss said, noting a trend of metronidazole for mild infections in this cohort having ever less efficacy.

Beyond mild infection, Dr. Moss said the first line of treatment should be vancomycin 125 mg four times daily, or 500 mg four times daily if it is complicated disease.

If your patient has recurrent C. diff. infection, Dr. Moss recommended a prolonged taper of vancomycin, but to be vigilant about it being truly an infection and not a flare-up of colonized bacteria.

“My bar for doing fecal transplant in these patients has dropped considerably in the last few years, because if you really want to squeeze out the niche that C. diff. occupies in the microbiome, fecal transplant is really the most effective way we have of doing that,” Dr. Moss said.

While there is a division in the field over whether to continue immunosuppression during antibiotic treatment, Dr. Moss cited a small study indicating that if a patient were on two or more immunosuppressants, they had a higher risk of death, megacolon, or shock during C. diff. treatment. “I think it’s hard to draw many conclusions from that,” Dr. Moss said. “It may just be a surrogate marker of severity of disease rather than infection, per se.”

The standard of care for recurrent and refractory C. diff. infection is now fecal transplant, according to Dr. Moss. A recent study of fecal transplantation showed an 89% cure rate of C. diff. infection after a single fecal transplant in IBD patients. Of the 36 IBD patients in the study, half of whom were on biologic and immunosuppressive therapies, four experienced disease flare-ups (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;109:1065-71 [doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133]. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368:474-5 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1214816]).

As for determining if there is an actual infection rather than colonization of C. diff., Dr. Moss said switching from using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) testing to PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing instead was helpful in first-time infections because the latter is more sensitive for determining actual infection; however, if a patient has recurrent infection, the higher clinical specificity of PCR makes it harder to tell if a positive result is infection or simply colonization.

Some institutions have dropped ELISA testing altogether, Dr. Moss said, although he thinks the use of single molecule array testing is, with its exponential sensitivity, a “good half-way step” between ELISA and PCR, and is useful for determining who is colonized vs. who is actually producing the toxin, even at a very low level.

Dr. Moss disclosed he has consulted for Janssen, Theravance, and Seres, and has received research support from the National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease, and Helmsley.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – You can confidently treat mild to severe Clostridium difficile infection in persons with inflammatory bowel disease, without disrupting their immunosuppression or other treatments, according to an expert.

“If your patient with IBD needs a fecal transplant for C. diff., you should not be concerned about withholding it,” Dr. Alan C. Moss said during a basic science presentation at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Moss is an associate professor of medicine and the director of translational research at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The first step, after you’ve determined that your patient has a true C. diff. infection, as opposed to having only been colonized by the bacteria, is choosing the best antibiotic. “Unfortunately, almost all IBD patients are excluded from controlled trials of antibiotics in C. diff. infection, so all we really have to go on are retrospective cohort data,” said Dr. Moss.

One such study, uncontrolled for disease severity, showed that a third of 114 inpatients with IBD who had a co-occurring C. diff. infection had higher 30-day readmission rates when treated first with metronidazole, per current standards of care, compared with the remaining two-thirds of patients who were treated first with vancomycin. The metronidazole group also averaged double the length of stays of the vancomycin group (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Sep;58:5054-9 [doi: 10.1128/AAC.02606-13]).

“This suggests that in IBD patients, especially for those who meet criteria for a severe C. diff. infection, vancomycin is the way to go,” Dr. Moss said, noting a trend of metronidazole for mild infections in this cohort having ever less efficacy.

Beyond mild infection, Dr. Moss said the first line of treatment should be vancomycin 125 mg four times daily, or 500 mg four times daily if it is complicated disease.

If your patient has recurrent C. diff. infection, Dr. Moss recommended a prolonged taper of vancomycin, but to be vigilant about it being truly an infection and not a flare-up of colonized bacteria.

“My bar for doing fecal transplant in these patients has dropped considerably in the last few years, because if you really want to squeeze out the niche that C. diff. occupies in the microbiome, fecal transplant is really the most effective way we have of doing that,” Dr. Moss said.

While there is a division in the field over whether to continue immunosuppression during antibiotic treatment, Dr. Moss cited a small study indicating that if a patient were on two or more immunosuppressants, they had a higher risk of death, megacolon, or shock during C. diff. treatment. “I think it’s hard to draw many conclusions from that,” Dr. Moss said. “It may just be a surrogate marker of severity of disease rather than infection, per se.”

The standard of care for recurrent and refractory C. diff. infection is now fecal transplant, according to Dr. Moss. A recent study of fecal transplantation showed an 89% cure rate of C. diff. infection after a single fecal transplant in IBD patients. Of the 36 IBD patients in the study, half of whom were on biologic and immunosuppressive therapies, four experienced disease flare-ups (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;109:1065-71 [doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133]. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368:474-5 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1214816]).

As for determining if there is an actual infection rather than colonization of C. diff., Dr. Moss said switching from using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) testing to PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing instead was helpful in first-time infections because the latter is more sensitive for determining actual infection; however, if a patient has recurrent infection, the higher clinical specificity of PCR makes it harder to tell if a positive result is infection or simply colonization.

Some institutions have dropped ELISA testing altogether, Dr. Moss said, although he thinks the use of single molecule array testing is, with its exponential sensitivity, a “good half-way step” between ELISA and PCR, and is useful for determining who is colonized vs. who is actually producing the toxin, even at a very low level.

Dr. Moss disclosed he has consulted for Janssen, Theravance, and Seres, and has received research support from the National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease, and Helmsley.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ORLANDO – You can confidently treat mild to severe Clostridium difficile infection in persons with inflammatory bowel disease, without disrupting their immunosuppression or other treatments, according to an expert.

“If your patient with IBD needs a fecal transplant for C. diff., you should not be concerned about withholding it,” Dr. Alan C. Moss said during a basic science presentation at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), sponsored by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Moss is an associate professor of medicine and the director of translational research at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The first step, after you’ve determined that your patient has a true C. diff. infection, as opposed to having only been colonized by the bacteria, is choosing the best antibiotic. “Unfortunately, almost all IBD patients are excluded from controlled trials of antibiotics in C. diff. infection, so all we really have to go on are retrospective cohort data,” said Dr. Moss.

One such study, uncontrolled for disease severity, showed that a third of 114 inpatients with IBD who had a co-occurring C. diff. infection had higher 30-day readmission rates when treated first with metronidazole, per current standards of care, compared with the remaining two-thirds of patients who were treated first with vancomycin. The metronidazole group also averaged double the length of stays of the vancomycin group (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Sep;58:5054-9 [doi: 10.1128/AAC.02606-13]).

“This suggests that in IBD patients, especially for those who meet criteria for a severe C. diff. infection, vancomycin is the way to go,” Dr. Moss said, noting a trend of metronidazole for mild infections in this cohort having ever less efficacy.

Beyond mild infection, Dr. Moss said the first line of treatment should be vancomycin 125 mg four times daily, or 500 mg four times daily if it is complicated disease.

If your patient has recurrent C. diff. infection, Dr. Moss recommended a prolonged taper of vancomycin, but to be vigilant about it being truly an infection and not a flare-up of colonized bacteria.

“My bar for doing fecal transplant in these patients has dropped considerably in the last few years, because if you really want to squeeze out the niche that C. diff. occupies in the microbiome, fecal transplant is really the most effective way we have of doing that,” Dr. Moss said.

While there is a division in the field over whether to continue immunosuppression during antibiotic treatment, Dr. Moss cited a small study indicating that if a patient were on two or more immunosuppressants, they had a higher risk of death, megacolon, or shock during C. diff. treatment. “I think it’s hard to draw many conclusions from that,” Dr. Moss said. “It may just be a surrogate marker of severity of disease rather than infection, per se.”

The standard of care for recurrent and refractory C. diff. infection is now fecal transplant, according to Dr. Moss. A recent study of fecal transplantation showed an 89% cure rate of C. diff. infection after a single fecal transplant in IBD patients. Of the 36 IBD patients in the study, half of whom were on biologic and immunosuppressive therapies, four experienced disease flare-ups (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;109:1065-71 [doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.133]. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368:474-5 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1214816]).

As for determining if there is an actual infection rather than colonization of C. diff., Dr. Moss said switching from using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) testing to PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing instead was helpful in first-time infections because the latter is more sensitive for determining actual infection; however, if a patient has recurrent infection, the higher clinical specificity of PCR makes it harder to tell if a positive result is infection or simply colonization.

Some institutions have dropped ELISA testing altogether, Dr. Moss said, although he thinks the use of single molecule array testing is, with its exponential sensitivity, a “good half-way step” between ELISA and PCR, and is useful for determining who is colonized vs. who is actually producing the toxin, even at a very low level.

Dr. Moss disclosed he has consulted for Janssen, Theravance, and Seres, and has received research support from the National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease, and Helmsley.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2015 ADVANCES IN IBD

Hospitalists Can Lend Expertise, Join SHM's Campaign to Improve Antibiotic Stewardship

Many antimicrobial stewards, such as infection prevention specialists, hospital epidemiologists, pharmacists, nurses, and hospitalists, are at the center of quality improvement and seek to achieve optimal clinical outcomes related to antimicrobial use.4 These antimicrobial stewards often strive to minimize harms and other adverse events, reduce the costs of healthcare for infections, and decrease the threat of antimicrobial resistance.3

Hospitalists play a critical role in quality improvement and directly influence inpatient outcomes daily. It’s essential that hospitalists continue to make patient safety and quality care a priority while employing a multidisciplinary approach in implementing antimicrobial stewardship best practices. Although antimicrobial stewardship programs have typically been led by infectious disease physicians and pharmacists, SHM recognizes the significant value of hospitalist leadership and/or participation.5 Although most hospitalists are familiar with the adverse effects of overprescribing antibiotics, their insight and collaboration with other hospital clinicians is necessary in order to Fight the Resistance.

Fight the Resistance, a new behavior change campaign from SHM and our Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, is intended to encourage appropriate prescribing and use of antibiotics in the hospital. The campaign’s primary objective is to change prescribing behaviors among hospitalists and other hospital clinicians and facilitate behavior change related to antibiotic prescribing.

The campaign officially launched on Nov. 10, 2015, with a kickoff webinar presented by Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, and Melhim Bou Alwan, MD. Dr. Flanders discussed the importance of hospitalist involvement in antimicrobial stewardship and the significance of working in multidisciplinary teams in order to reduce overprescribing and the threat of antibiotic resistance.

Dr. Bou Alwan explained SHM’s efforts to fight antimicrobial resistance and informed the audience of SHM’s commitment to antibiotic stewardship. The webinar launch was a huge success, and SHM is excited to continue fighting the resistance with physicians across the country.

In order to Fight the Resistance, SHM is asking hospitalists to commit to the following actions:

- Work with your team. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, and infectious disease experts need to work together to ensure that antibiotics are used appropriately. Consider the patients part of your team, too, by discussing with them why antibiotics may not be the best choice of treatment.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns, and identify mechanisms that can be used to educate providers about overprescribing in your hospital.

- Rethink your antibiotic treatment time course. Be sure to adhere to your hospital’s antibiotic treatment guidelines, track use of antibiotics, and set a stop date from when you first prescribe them.

SHM believes changing antibiotic prescription behaviors is a team effort and encourages hospitalists to get involved by visiting www.fighttheresistance.org. There you can find Fight the Resistance themed posters, resources, and educational materials to encourage enhanced stewardship and teamwork in your hospital. TH

Mobola Owolabi is senior project manager for The Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement

References

- The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. FACT SHEET: Obama Administration releases national action plan to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. March 27, 2015. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/03/27/fact-sheet-obama-administration-releases-national-action-plan-combat-ant. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Federal engagement in antimicrobial resistance. June 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/federal-engagement-in-ar/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Promoting antimicrobial stewardship in human medicine. 2015. Available at: http://www.idsociety.org/Stewardship_Policy/. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, Rosenberg DJ. Role of the hospitalist in antimicrobial stewardship: a review of work completed and description of a multisite collaborative. Clin Ther. 2013; 35(6):751-757.

Many antimicrobial stewards, such as infection prevention specialists, hospital epidemiologists, pharmacists, nurses, and hospitalists, are at the center of quality improvement and seek to achieve optimal clinical outcomes related to antimicrobial use.4 These antimicrobial stewards often strive to minimize harms and other adverse events, reduce the costs of healthcare for infections, and decrease the threat of antimicrobial resistance.3

Hospitalists play a critical role in quality improvement and directly influence inpatient outcomes daily. It’s essential that hospitalists continue to make patient safety and quality care a priority while employing a multidisciplinary approach in implementing antimicrobial stewardship best practices. Although antimicrobial stewardship programs have typically been led by infectious disease physicians and pharmacists, SHM recognizes the significant value of hospitalist leadership and/or participation.5 Although most hospitalists are familiar with the adverse effects of overprescribing antibiotics, their insight and collaboration with other hospital clinicians is necessary in order to Fight the Resistance.

Fight the Resistance, a new behavior change campaign from SHM and our Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, is intended to encourage appropriate prescribing and use of antibiotics in the hospital. The campaign’s primary objective is to change prescribing behaviors among hospitalists and other hospital clinicians and facilitate behavior change related to antibiotic prescribing.

The campaign officially launched on Nov. 10, 2015, with a kickoff webinar presented by Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, and Melhim Bou Alwan, MD. Dr. Flanders discussed the importance of hospitalist involvement in antimicrobial stewardship and the significance of working in multidisciplinary teams in order to reduce overprescribing and the threat of antibiotic resistance.

Dr. Bou Alwan explained SHM’s efforts to fight antimicrobial resistance and informed the audience of SHM’s commitment to antibiotic stewardship. The webinar launch was a huge success, and SHM is excited to continue fighting the resistance with physicians across the country.

In order to Fight the Resistance, SHM is asking hospitalists to commit to the following actions:

- Work with your team. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, and infectious disease experts need to work together to ensure that antibiotics are used appropriately. Consider the patients part of your team, too, by discussing with them why antibiotics may not be the best choice of treatment.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns, and identify mechanisms that can be used to educate providers about overprescribing in your hospital.

- Rethink your antibiotic treatment time course. Be sure to adhere to your hospital’s antibiotic treatment guidelines, track use of antibiotics, and set a stop date from when you first prescribe them.

SHM believes changing antibiotic prescription behaviors is a team effort and encourages hospitalists to get involved by visiting www.fighttheresistance.org. There you can find Fight the Resistance themed posters, resources, and educational materials to encourage enhanced stewardship and teamwork in your hospital. TH

Mobola Owolabi is senior project manager for The Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement

References

- The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. FACT SHEET: Obama Administration releases national action plan to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. March 27, 2015. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/03/27/fact-sheet-obama-administration-releases-national-action-plan-combat-ant. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Federal engagement in antimicrobial resistance. June 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/federal-engagement-in-ar/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Promoting antimicrobial stewardship in human medicine. 2015. Available at: http://www.idsociety.org/Stewardship_Policy/. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, Rosenberg DJ. Role of the hospitalist in antimicrobial stewardship: a review of work completed and description of a multisite collaborative. Clin Ther. 2013; 35(6):751-757.

Many antimicrobial stewards, such as infection prevention specialists, hospital epidemiologists, pharmacists, nurses, and hospitalists, are at the center of quality improvement and seek to achieve optimal clinical outcomes related to antimicrobial use.4 These antimicrobial stewards often strive to minimize harms and other adverse events, reduce the costs of healthcare for infections, and decrease the threat of antimicrobial resistance.3

Hospitalists play a critical role in quality improvement and directly influence inpatient outcomes daily. It’s essential that hospitalists continue to make patient safety and quality care a priority while employing a multidisciplinary approach in implementing antimicrobial stewardship best practices. Although antimicrobial stewardship programs have typically been led by infectious disease physicians and pharmacists, SHM recognizes the significant value of hospitalist leadership and/or participation.5 Although most hospitalists are familiar with the adverse effects of overprescribing antibiotics, their insight and collaboration with other hospital clinicians is necessary in order to Fight the Resistance.

Fight the Resistance, a new behavior change campaign from SHM and our Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, is intended to encourage appropriate prescribing and use of antibiotics in the hospital. The campaign’s primary objective is to change prescribing behaviors among hospitalists and other hospital clinicians and facilitate behavior change related to antibiotic prescribing.

The campaign officially launched on Nov. 10, 2015, with a kickoff webinar presented by Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, and Melhim Bou Alwan, MD. Dr. Flanders discussed the importance of hospitalist involvement in antimicrobial stewardship and the significance of working in multidisciplinary teams in order to reduce overprescribing and the threat of antibiotic resistance.

Dr. Bou Alwan explained SHM’s efforts to fight antimicrobial resistance and informed the audience of SHM’s commitment to antibiotic stewardship. The webinar launch was a huge success, and SHM is excited to continue fighting the resistance with physicians across the country.

In order to Fight the Resistance, SHM is asking hospitalists to commit to the following actions:

- Work with your team. Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, and infectious disease experts need to work together to ensure that antibiotics are used appropriately. Consider the patients part of your team, too, by discussing with them why antibiotics may not be the best choice of treatment.

- Pay attention to appropriate antibiotic choice and resistance patterns, and identify mechanisms that can be used to educate providers about overprescribing in your hospital.

- Rethink your antibiotic treatment time course. Be sure to adhere to your hospital’s antibiotic treatment guidelines, track use of antibiotics, and set a stop date from when you first prescribe them.

SHM believes changing antibiotic prescription behaviors is a team effort and encourages hospitalists to get involved by visiting www.fighttheresistance.org. There you can find Fight the Resistance themed posters, resources, and educational materials to encourage enhanced stewardship and teamwork in your hospital. TH

Mobola Owolabi is senior project manager for The Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement

References

- The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. FACT SHEET: Obama Administration releases national action plan to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. March 27, 2015. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/03/27/fact-sheet-obama-administration-releases-national-action-plan-combat-ant. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Federal engagement in antimicrobial resistance. June 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/federal-engagement-in-ar/index.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Promoting antimicrobial stewardship in human medicine. 2015. Available at: http://www.idsociety.org/Stewardship_Policy/. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- CDC. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, Rosenberg DJ. Role of the hospitalist in antimicrobial stewardship: a review of work completed and description of a multisite collaborative. Clin Ther. 2013; 35(6):751-757.

Why 10 days of antibiotics for infections is not magic

In the United States, we treat almost all infections for 10 days. Why? In France, most infections are treated for 8 days. In the U.K., most infections are treated for 5 days. In many other countries, infections are treated until symptomatic improvement occurs. Can everyone outside the United States be wrong? What is the evidence base for the various recommended durations? Moreover, what is the harm in treating for longer than necessary?

The U.S. tradition of 10 days’ treatment for infections arose from the 1940 trials of injectable penicillin for prevention of acute rheumatic fever in military recruits who had group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Injections of penicillin G mixed in peanut oil produced therapeutic levels of penicillin for about 3 days. Soldiers who received three sequential injections had the lowest occurrence of rheumatic fever; two injections were not as good and four injections did not add to the prevention rate. So three injections meant 9 days’ treatment; 9 days was rounded up to 10 days, and there you have it.

We have come a long way since the 1940s. For strep throat, we now have three approved antibiotics for 5 days’ treatment: cefdinir, cefpodoxime proxetil, and azithromycin, all evidence based and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved. One large study was done in the 1980s with cefadroxil for 5 days, and that duration was as effective in strep eradication as was 10 days, but the company never pursued the 5-day indication.

The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment is generally considered to be 10 days in the United States, however, there is scant evidence base for that recommendation. The recent American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Family Physicians guidelines endorse 10 days of treatment duration as the standard for most acute otitis media (AOM) (Pediatrics 2013;131[3]:e964-99), but acknowledge that shorter treatment regimens may be as effective. Specifically, the guideline states: “A 7-day course of oral antibiotic appears to be equally effective in children 2- to 5 years of age with mild to moderate AOM. For children 6 years and older with mild to moderate AOM symptoms, a 5- to 7-day course is adequate treatment.” A systematic analysis and a meta-analysis have concluded that 5 days’ duration of antibiotics is as effective as 10 days’ treatment for all children over age 2 years and only marginally inferior to 10 days for children under the age of 2 years old (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;[9]:CD001095).

Thirty years ago, our group and others began to do studies involving “double tympanocentesis,” where an ear tap was done at time of diagnosis and again 3-5 days later to prove bacterial cure for various antibiotics that were in trials. We learned that if the organism was sensitive to the antibiotic chosen, then it was dead by days 3-5. Most of the failures were due to resistant bacteria. So treating longer was not going to help. It was time to change the antibiotic if clinical improvement had not occurred. Our group published a study 15 years ago of 2,172 children comparing 5-, 7-, and 10-days’ treatment of AOM, and concluded that 5 days’ treatment was equivalent to 7- and 10-days of treatment for all ages unless the child had a perforated tympanic membrane or the child had been treated for AOM within the preceding month since recently treated AOM was associated with more frequent causation of AOM by resistant bacteria and with a continued inflamed middle ear mucosa (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124[4]:381-7). Since then we have treated all children with ear infections for 5 days, including amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate as well as various cephalosporins unless the eardrum had perforated or the child had a recurrent AOM within the prior 30 days. That is a lot of patients in 15 years, and the results have been just as good as when we used 10 days as standard.

Acute sinusitis is another interesting story. The AAP guideline states: “The optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for patients with acute bacterial sinusitis has not received systematic study. Recommendations based on clinical observation varied widely, from 1- to 28 days (Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132[1]:e262-80). The prior AAP guideline endorsed “antibiotic therapy be continued for 7 days after the patient becomes free of symptoms and signs (Pediatrics. 2001 Sep;108[3]:798-808). Our group reasoned that the etiology and pathogenesis of sinusitis and AOM are identical, involving ascension of a bacterial inoculum from the nasopharynx via the osteomeatal complex to the sinuses just like ascension of infection via the eustachian tube to the middle ear. Therefore, beginning 25 years ago, we began to treat all children with sinus infections for 5 days, including amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, as well as various cephalosporins. Again, that is a lot of patients, and the results have been just as good as when we used 10 days as standard.

What about community-acquired pneumonia? The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guideline states: “Treatment courses of 10 days [of antibiotics] have been best studied, although shorter courses may be just as effective, particularly for mild disease managed on an outpatient basis” (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30). Our group reasoned that antibiotics reach higher levels in the lungs than they do in the closed space of the middle ear or sinuses. Therefore, beginning 25 years ago, we began to treat all children with bronchopneumonia and lobar pneumonia for 5 days, including amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate as well as various cephalosporins and azithromycin. That is a lot of patients, and the results have been just as good as when we used 10 days as standard.

What about skin and soft tissue infections? The IDSA guideline states that the duration of treatment for impetigo is 7 days, for cellulitis is 5 days, and for furuncles and carbuncles no duration is stated, but they allow no antibiotics be used at all if the patient is not febrile and white blood cell count is not elevated after incision and drainage (Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Jul 15;59[2]:e10-52).

So what is the harm to longer courses of antibiotics? As I have written in this column recently, we have learned a lot about the importance of our gut microbiome. The resident flora of our gut modulates our immune system favorably. Disturbing our gut flora with antibiotics is potentially harmful because the antibiotics often kill many species of healthy gut flora and cause disequilibrium of the flora, resulting in diminished innate immunity responses. Shorter treatment courses with antibiotics cause less disturbance of the healthy gut flora.

The rest of the world cannot all be wrong and the United States all right regarding the duration of antibiotic treatment for common infections. Moreover, in an era of evidence-based medicine, it is necessary to make changes from tradition. The evidence is there to recommend that 5 days’ treatment become the standard for treatment with selected cephalosporins as approved by the FDA – for AOM, for sinusitis, for community-acquired pneumonia, and for skin and soft tissue infections.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said that he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In the United States, we treat almost all infections for 10 days. Why? In France, most infections are treated for 8 days. In the U.K., most infections are treated for 5 days. In many other countries, infections are treated until symptomatic improvement occurs. Can everyone outside the United States be wrong? What is the evidence base for the various recommended durations? Moreover, what is the harm in treating for longer than necessary?

The U.S. tradition of 10 days’ treatment for infections arose from the 1940 trials of injectable penicillin for prevention of acute rheumatic fever in military recruits who had group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Injections of penicillin G mixed in peanut oil produced therapeutic levels of penicillin for about 3 days. Soldiers who received three sequential injections had the lowest occurrence of rheumatic fever; two injections were not as good and four injections did not add to the prevention rate. So three injections meant 9 days’ treatment; 9 days was rounded up to 10 days, and there you have it.

We have come a long way since the 1940s. For strep throat, we now have three approved antibiotics for 5 days’ treatment: cefdinir, cefpodoxime proxetil, and azithromycin, all evidence based and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved. One large study was done in the 1980s with cefadroxil for 5 days, and that duration was as effective in strep eradication as was 10 days, but the company never pursued the 5-day indication.

The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment is generally considered to be 10 days in the United States, however, there is scant evidence base for that recommendation. The recent American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Family Physicians guidelines endorse 10 days of treatment duration as the standard for most acute otitis media (AOM) (Pediatrics 2013;131[3]:e964-99), but acknowledge that shorter treatment regimens may be as effective. Specifically, the guideline states: “A 7-day course of oral antibiotic appears to be equally effective in children 2- to 5 years of age with mild to moderate AOM. For children 6 years and older with mild to moderate AOM symptoms, a 5- to 7-day course is adequate treatment.” A systematic analysis and a meta-analysis have concluded that 5 days’ duration of antibiotics is as effective as 10 days’ treatment for all children over age 2 years and only marginally inferior to 10 days for children under the age of 2 years old (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;[9]:CD001095).

Thirty years ago, our group and others began to do studies involving “double tympanocentesis,” where an ear tap was done at time of diagnosis and again 3-5 days later to prove bacterial cure for various antibiotics that were in trials. We learned that if the organism was sensitive to the antibiotic chosen, then it was dead by days 3-5. Most of the failures were due to resistant bacteria. So treating longer was not going to help. It was time to change the antibiotic if clinical improvement had not occurred. Our group published a study 15 years ago of 2,172 children comparing 5-, 7-, and 10-days’ treatment of AOM, and concluded that 5 days’ treatment was equivalent to 7- and 10-days of treatment for all ages unless the child had a perforated tympanic membrane or the child had been treated for AOM within the preceding month since recently treated AOM was associated with more frequent causation of AOM by resistant bacteria and with a continued inflamed middle ear mucosa (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124[4]:381-7). Since then we have treated all children with ear infections for 5 days, including amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate as well as various cephalosporins unless the eardrum had perforated or the child had a recurrent AOM within the prior 30 days. That is a lot of patients in 15 years, and the results have been just as good as when we used 10 days as standard.

Acute sinusitis is another interesting story. The AAP guideline states: “The optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for patients with acute bacterial sinusitis has not received systematic study. Recommendations based on clinical observation varied widely, from 1- to 28 days (Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132[1]:e262-80). The prior AAP guideline endorsed “antibiotic therapy be continued for 7 days after the patient becomes free of symptoms and signs (Pediatrics. 2001 Sep;108[3]:798-808). Our group reasoned that the etiology and pathogenesis of sinusitis and AOM are identical, involving ascension of a bacterial inoculum from the nasopharynx via the osteomeatal complex to the sinuses just like ascension of infection via the eustachian tube to the middle ear. Therefore, beginning 25 years ago, we began to treat all children with sinus infections for 5 days, including amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, as well as various cephalosporins. Again, that is a lot of patients, and the results have been just as good as when we used 10 days as standard.