User login

Global bronchial thermoplasty registry for asthma documents benefits

PARIS – A global registry to track the safety and efficacy of shows benefits comparable to those previously reported in randomized trials, according to 1-year results presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Bronchothermoplasty has been Food and Drug Administration approved since 2010, but joint 2014 guidelines from the ERS and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recommended that this procedure be restricted to patients participating in a registry, making these findings an important part of an ongoing assessment, according to Alfons Torrego Fernández, MD, of the pulmonology service at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona.

The BT Global Registry (BTGR), created at the end of 2014, involves 18 centers in Europe, South Africa, and Australia. Dr. Fernandez provided data on 123 of the 157 patients enrolled by the end of 2016. All had at least 1 year of follow-up.

Compared with the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, the proportion of patients with severe exacerbations in the year following this procedure fell from 90.3% to 59.6%, a 34% reduction (P less than .001). The proportion of patients requiring oral corticosteroids fell from 47.8% to 23.5%, a reduction of more than 50%.

Relative to the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, “there was also a reduction in emergency room visits [21.1% vs. 54.6%] and hospitalizations [20.2% vs. 43%] as well as a reduction in the need for asthma maintenance medications,” Dr. Fernandez reported.

On the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), quality of life (QOL) was improved on average by 1.2 points from the prior year (4.48 vs. 3.26; P less than .05), according to Dr. Fernandez. The proportion of patients who achieved at least a 0.5-point increase in the ACQ, a level that Dr. Fernandez said is considered clinically relevant, was 67.1%.

However, when lung function measures such as forced expiratory volume in one second and fractional exhaled nitric oxide taken 1 year after bronchothermoplasty were compared with the same measures taken prior to this treatment, there was no significant improvement, according to Dr. Fernandez.

Bronchial thermoplasty involves the use of thermal energy delivered through a bronchoscope to reduce airway smooth muscle mass, thereby eliminating a source of airway restriction. Although nearly 70% of severe asthma patients in this BTGR derived an improvement in quality of life, 30% did not. Asked if the registry has provided any insight about who does or does not respond, Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that this is “the key question,” but added that “no specific profile or biomarker” has yet been identified.

“These are early results, but a 2-year follow-up is planned,” he said.

Although the technical aspects of bronchial thermoplasty “are quite well standardized,” Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that there might be a learning curve that favors experienced operators. He reported that outcomes between high- and low-volume centers in BTGR have not yet been compared. However, he maintained that “these results in real-life patients confirm that severe asthma patients can benefit” from this therapy as shown previously in sham-controlled trials.

Dr. Fernandez reported having no conflicts of interest. The registry is funded by Boston Scientific.

PARIS – A global registry to track the safety and efficacy of shows benefits comparable to those previously reported in randomized trials, according to 1-year results presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Bronchothermoplasty has been Food and Drug Administration approved since 2010, but joint 2014 guidelines from the ERS and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recommended that this procedure be restricted to patients participating in a registry, making these findings an important part of an ongoing assessment, according to Alfons Torrego Fernández, MD, of the pulmonology service at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona.

The BT Global Registry (BTGR), created at the end of 2014, involves 18 centers in Europe, South Africa, and Australia. Dr. Fernandez provided data on 123 of the 157 patients enrolled by the end of 2016. All had at least 1 year of follow-up.

Compared with the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, the proportion of patients with severe exacerbations in the year following this procedure fell from 90.3% to 59.6%, a 34% reduction (P less than .001). The proportion of patients requiring oral corticosteroids fell from 47.8% to 23.5%, a reduction of more than 50%.

Relative to the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, “there was also a reduction in emergency room visits [21.1% vs. 54.6%] and hospitalizations [20.2% vs. 43%] as well as a reduction in the need for asthma maintenance medications,” Dr. Fernandez reported.

On the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), quality of life (QOL) was improved on average by 1.2 points from the prior year (4.48 vs. 3.26; P less than .05), according to Dr. Fernandez. The proportion of patients who achieved at least a 0.5-point increase in the ACQ, a level that Dr. Fernandez said is considered clinically relevant, was 67.1%.

However, when lung function measures such as forced expiratory volume in one second and fractional exhaled nitric oxide taken 1 year after bronchothermoplasty were compared with the same measures taken prior to this treatment, there was no significant improvement, according to Dr. Fernandez.

Bronchial thermoplasty involves the use of thermal energy delivered through a bronchoscope to reduce airway smooth muscle mass, thereby eliminating a source of airway restriction. Although nearly 70% of severe asthma patients in this BTGR derived an improvement in quality of life, 30% did not. Asked if the registry has provided any insight about who does or does not respond, Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that this is “the key question,” but added that “no specific profile or biomarker” has yet been identified.

“These are early results, but a 2-year follow-up is planned,” he said.

Although the technical aspects of bronchial thermoplasty “are quite well standardized,” Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that there might be a learning curve that favors experienced operators. He reported that outcomes between high- and low-volume centers in BTGR have not yet been compared. However, he maintained that “these results in real-life patients confirm that severe asthma patients can benefit” from this therapy as shown previously in sham-controlled trials.

Dr. Fernandez reported having no conflicts of interest. The registry is funded by Boston Scientific.

PARIS – A global registry to track the safety and efficacy of shows benefits comparable to those previously reported in randomized trials, according to 1-year results presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Bronchothermoplasty has been Food and Drug Administration approved since 2010, but joint 2014 guidelines from the ERS and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recommended that this procedure be restricted to patients participating in a registry, making these findings an important part of an ongoing assessment, according to Alfons Torrego Fernández, MD, of the pulmonology service at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona.

The BT Global Registry (BTGR), created at the end of 2014, involves 18 centers in Europe, South Africa, and Australia. Dr. Fernandez provided data on 123 of the 157 patients enrolled by the end of 2016. All had at least 1 year of follow-up.

Compared with the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, the proportion of patients with severe exacerbations in the year following this procedure fell from 90.3% to 59.6%, a 34% reduction (P less than .001). The proportion of patients requiring oral corticosteroids fell from 47.8% to 23.5%, a reduction of more than 50%.

Relative to the year prior to bronchial thermoplasty, “there was also a reduction in emergency room visits [21.1% vs. 54.6%] and hospitalizations [20.2% vs. 43%] as well as a reduction in the need for asthma maintenance medications,” Dr. Fernandez reported.

On the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), quality of life (QOL) was improved on average by 1.2 points from the prior year (4.48 vs. 3.26; P less than .05), according to Dr. Fernandez. The proportion of patients who achieved at least a 0.5-point increase in the ACQ, a level that Dr. Fernandez said is considered clinically relevant, was 67.1%.

However, when lung function measures such as forced expiratory volume in one second and fractional exhaled nitric oxide taken 1 year after bronchothermoplasty were compared with the same measures taken prior to this treatment, there was no significant improvement, according to Dr. Fernandez.

Bronchial thermoplasty involves the use of thermal energy delivered through a bronchoscope to reduce airway smooth muscle mass, thereby eliminating a source of airway restriction. Although nearly 70% of severe asthma patients in this BTGR derived an improvement in quality of life, 30% did not. Asked if the registry has provided any insight about who does or does not respond, Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that this is “the key question,” but added that “no specific profile or biomarker” has yet been identified.

“These are early results, but a 2-year follow-up is planned,” he said.

Although the technical aspects of bronchial thermoplasty “are quite well standardized,” Dr. Fernandez acknowledged that there might be a learning curve that favors experienced operators. He reported that outcomes between high- and low-volume centers in BTGR have not yet been compared. However, he maintained that “these results in real-life patients confirm that severe asthma patients can benefit” from this therapy as shown previously in sham-controlled trials.

Dr. Fernandez reported having no conflicts of interest. The registry is funded by Boston Scientific.

REPORTING FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: In a global registry, bronchothermoplasty provided improvement in real-world severe asthma consistent with clinical trials.

Major finding: At 1 year, severe asthma exacerbations were reduced 34% (P less than .001) relative to the year before treatment.

Study details: Open-label observational study.

Disclosures: Dr. Fernandez reported having no conflicts of interest. The registry is funded by Boston Scientific.

Dupilumab efficacy extends to chronic rhinosinusitis/nasal polyposis

PARIS – Severe asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), nasal polyposis (NP), or both derive more protection from severe exacerbations with the monoclonal antibody dupilumab than do those who do not have these comorbidities, according to a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“Dupilumab reduced rates of severe exacerbations and improved FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] in patients in asthma patients with or without CRS/NP. In those with CRS/NP, dupilumab reduced symptoms associated with these comorbidities,” reported Ian Pavord, MBBS, statutory chair in respiratory medicine at University of Oxford (England).

The data were drawn from the phase 3 Liberty Asthma Quest trial, which was published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2486-96). In that study, both the 200-mg and 300-mg dose of dupilumab (Dupixent) administered every 2 weeks was associated with about a 50% reduction in the annualized rate of severe exacerbations relative to placebo (P less than .001 for both doses).

In this new post hoc analysis, response in the 382 patients who entered the study with a history of CRS/NP was compared with the 1,520 without CRS/NP. In the CRS/NP patients, the reductions relative to placebo in the rates of severe exacerbations, defined as 3 or more days of systemic glucocorticoids or visit to an emergency department leading to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, were 63% and 61% for the 200-mg and 300-mg doses of dupilumab, respectively (both P less than .001).

In the non-CRS/NP arms, the reductions relative to placebo were 42% and 40%, respectively (both P less than .001). The greater relative reductions in the CRS/NP patients were achieved even though they were older (mean age approximately 52 vs. 47 years for non-CRS/NP patients), had a significantly greater number of exacerbations in the past year (P = .027), and had higher baseline fractional exhaled nitric oxide and eosinophil levels (both P less than .001), Dr. Pavord reported.

“The greater asthma severity in the CRS/NP patients in this trial is consistent with that reported previously by others,” Dr. Pavord said.

Although the greater asthma severity may have provided a larger margin for benefit, Dr. Pavord also reported that there were improvements in CRS/NP-specific symptoms as measured with the 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22). By week 12, the total score reduction in SNOT-22 was approximately 15 points (P less than .05) from baseline for both the 200-mg and 300-mg dupilumab doses. This was significantly greater (P less than .05) relative to modest SNOT-22 reductions in the placebo arms (P less than .05). After 52 weeks, the reduction In SNOT-22 scores were sustained, providing an even greater statistical advantage over placebo (P less than .001).

In addition to greater protection against severe exacerbations and CRS/NP-specific symptoms, dupilumab may offer specific improvements on CRS/NP pathology, according to Dr. Pavord. Although imaging was not part of this study, he noted in particular that previous studies with dupilumab as well as other biologics have shown shrinkage of nasal polyps with treatment.

Dupilumab was similarly well tolerated in those with and without CRS/NP. The most common adverse event was injection site reactions in both groups, Dr. Pavord said.

Calling CRS and NP “important comorbidities” in severe asthma patients, Dr. Pavord said that this analysis should be reassuring for those who with CRS/NP who are being considered for dupilumab. Already approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, dupilumab, which binds to interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 receptors, is currently under review for the treatment of moderate to severe asthma.

Dr. Pavord has financial relationships with Aerocrine, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Knapp, Merck Sharpe, Novartis, Knapp Teva, RespiVert, and Schering-Plough.

PARIS – Severe asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), nasal polyposis (NP), or both derive more protection from severe exacerbations with the monoclonal antibody dupilumab than do those who do not have these comorbidities, according to a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“Dupilumab reduced rates of severe exacerbations and improved FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] in patients in asthma patients with or without CRS/NP. In those with CRS/NP, dupilumab reduced symptoms associated with these comorbidities,” reported Ian Pavord, MBBS, statutory chair in respiratory medicine at University of Oxford (England).

The data were drawn from the phase 3 Liberty Asthma Quest trial, which was published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2486-96). In that study, both the 200-mg and 300-mg dose of dupilumab (Dupixent) administered every 2 weeks was associated with about a 50% reduction in the annualized rate of severe exacerbations relative to placebo (P less than .001 for both doses).

In this new post hoc analysis, response in the 382 patients who entered the study with a history of CRS/NP was compared with the 1,520 without CRS/NP. In the CRS/NP patients, the reductions relative to placebo in the rates of severe exacerbations, defined as 3 or more days of systemic glucocorticoids or visit to an emergency department leading to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, were 63% and 61% for the 200-mg and 300-mg doses of dupilumab, respectively (both P less than .001).

In the non-CRS/NP arms, the reductions relative to placebo were 42% and 40%, respectively (both P less than .001). The greater relative reductions in the CRS/NP patients were achieved even though they were older (mean age approximately 52 vs. 47 years for non-CRS/NP patients), had a significantly greater number of exacerbations in the past year (P = .027), and had higher baseline fractional exhaled nitric oxide and eosinophil levels (both P less than .001), Dr. Pavord reported.

“The greater asthma severity in the CRS/NP patients in this trial is consistent with that reported previously by others,” Dr. Pavord said.

Although the greater asthma severity may have provided a larger margin for benefit, Dr. Pavord also reported that there were improvements in CRS/NP-specific symptoms as measured with the 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22). By week 12, the total score reduction in SNOT-22 was approximately 15 points (P less than .05) from baseline for both the 200-mg and 300-mg dupilumab doses. This was significantly greater (P less than .05) relative to modest SNOT-22 reductions in the placebo arms (P less than .05). After 52 weeks, the reduction In SNOT-22 scores were sustained, providing an even greater statistical advantage over placebo (P less than .001).

In addition to greater protection against severe exacerbations and CRS/NP-specific symptoms, dupilumab may offer specific improvements on CRS/NP pathology, according to Dr. Pavord. Although imaging was not part of this study, he noted in particular that previous studies with dupilumab as well as other biologics have shown shrinkage of nasal polyps with treatment.

Dupilumab was similarly well tolerated in those with and without CRS/NP. The most common adverse event was injection site reactions in both groups, Dr. Pavord said.

Calling CRS and NP “important comorbidities” in severe asthma patients, Dr. Pavord said that this analysis should be reassuring for those who with CRS/NP who are being considered for dupilumab. Already approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, dupilumab, which binds to interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 receptors, is currently under review for the treatment of moderate to severe asthma.

Dr. Pavord has financial relationships with Aerocrine, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Knapp, Merck Sharpe, Novartis, Knapp Teva, RespiVert, and Schering-Plough.

PARIS – Severe asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), nasal polyposis (NP), or both derive more protection from severe exacerbations with the monoclonal antibody dupilumab than do those who do not have these comorbidities, according to a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“Dupilumab reduced rates of severe exacerbations and improved FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] in patients in asthma patients with or without CRS/NP. In those with CRS/NP, dupilumab reduced symptoms associated with these comorbidities,” reported Ian Pavord, MBBS, statutory chair in respiratory medicine at University of Oxford (England).

The data were drawn from the phase 3 Liberty Asthma Quest trial, which was published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018;378:2486-96). In that study, both the 200-mg and 300-mg dose of dupilumab (Dupixent) administered every 2 weeks was associated with about a 50% reduction in the annualized rate of severe exacerbations relative to placebo (P less than .001 for both doses).

In this new post hoc analysis, response in the 382 patients who entered the study with a history of CRS/NP was compared with the 1,520 without CRS/NP. In the CRS/NP patients, the reductions relative to placebo in the rates of severe exacerbations, defined as 3 or more days of systemic glucocorticoids or visit to an emergency department leading to treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, were 63% and 61% for the 200-mg and 300-mg doses of dupilumab, respectively (both P less than .001).

In the non-CRS/NP arms, the reductions relative to placebo were 42% and 40%, respectively (both P less than .001). The greater relative reductions in the CRS/NP patients were achieved even though they were older (mean age approximately 52 vs. 47 years for non-CRS/NP patients), had a significantly greater number of exacerbations in the past year (P = .027), and had higher baseline fractional exhaled nitric oxide and eosinophil levels (both P less than .001), Dr. Pavord reported.

“The greater asthma severity in the CRS/NP patients in this trial is consistent with that reported previously by others,” Dr. Pavord said.

Although the greater asthma severity may have provided a larger margin for benefit, Dr. Pavord also reported that there were improvements in CRS/NP-specific symptoms as measured with the 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22). By week 12, the total score reduction in SNOT-22 was approximately 15 points (P less than .05) from baseline for both the 200-mg and 300-mg dupilumab doses. This was significantly greater (P less than .05) relative to modest SNOT-22 reductions in the placebo arms (P less than .05). After 52 weeks, the reduction In SNOT-22 scores were sustained, providing an even greater statistical advantage over placebo (P less than .001).

In addition to greater protection against severe exacerbations and CRS/NP-specific symptoms, dupilumab may offer specific improvements on CRS/NP pathology, according to Dr. Pavord. Although imaging was not part of this study, he noted in particular that previous studies with dupilumab as well as other biologics have shown shrinkage of nasal polyps with treatment.

Dupilumab was similarly well tolerated in those with and without CRS/NP. The most common adverse event was injection site reactions in both groups, Dr. Pavord said.

Calling CRS and NP “important comorbidities” in severe asthma patients, Dr. Pavord said that this analysis should be reassuring for those who with CRS/NP who are being considered for dupilumab. Already approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, dupilumab, which binds to interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 receptors, is currently under review for the treatment of moderate to severe asthma.

Dr. Pavord has financial relationships with Aerocrine, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Knapp, Merck Sharpe, Novartis, Knapp Teva, RespiVert, and Schering-Plough.

REPORTING FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: In asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and/or nasal polyposis (CRS/NP), dupilumab reduces exacerbations.

Major finding: At 52 weeks, severe exacerbations were reduced 61% in CRS/NP patients and 40% in non-CRS/NP patients (both P less than .001).

Study details: Post hoc analysis of phase 3 trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Pavord has financial relationships with Aerocrine, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Knapp, Merck Sharpe, Novartis, Knapp Teva, RespiVert, and Schering-Plough.

Recommendations to Improve Asthma Outcomes: Work Group Call to Action

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

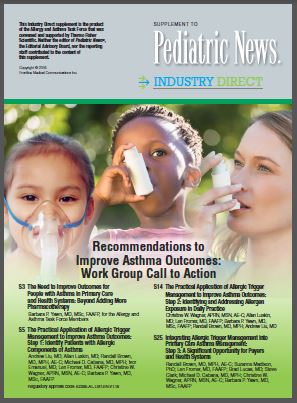

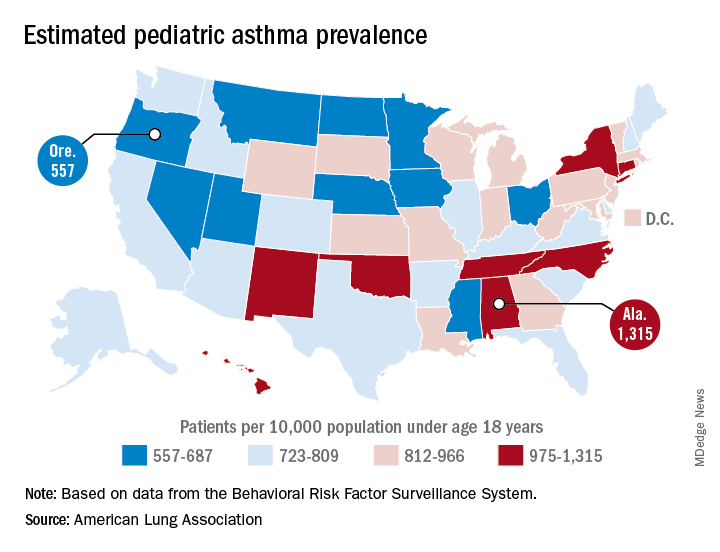

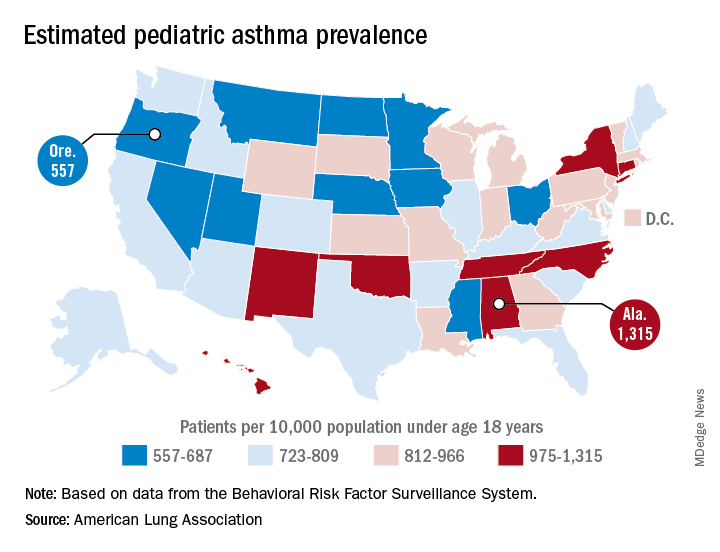

Alabama, Oregon, and pediatric asthma

according to estimates from the American Lung Association.

Oregon’s rate comes in at 557 per 10,000 population under the age of 18 years, just ahead of Montana at 574 per 10,000 and Iowa at 577. The prevalence of pediatric asthma in Alabama is 1,315 per 10,000, with North Carolina (1,149), Connecticut (1,107), Hawaii (1,026), and New York (1,005) joining it as members of the over-1,000 club. (MDedge News used the ALA’s estimates for persons under age 18 years with asthma in each state and Census Bureau estimates for population to calculate an unadjusted rate for each state.)

The ALA analysis was based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Behavioral System surveys for 2016 (31 states), 2015 (District of Columbia, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Texas), 2014 (Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia), 2012 (North Dakota and Wyoming), and 2011 (Iowa). National data were used for eight states (Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia) that had no data available.

according to estimates from the American Lung Association.

Oregon’s rate comes in at 557 per 10,000 population under the age of 18 years, just ahead of Montana at 574 per 10,000 and Iowa at 577. The prevalence of pediatric asthma in Alabama is 1,315 per 10,000, with North Carolina (1,149), Connecticut (1,107), Hawaii (1,026), and New York (1,005) joining it as members of the over-1,000 club. (MDedge News used the ALA’s estimates for persons under age 18 years with asthma in each state and Census Bureau estimates for population to calculate an unadjusted rate for each state.)

The ALA analysis was based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Behavioral System surveys for 2016 (31 states), 2015 (District of Columbia, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Texas), 2014 (Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia), 2012 (North Dakota and Wyoming), and 2011 (Iowa). National data were used for eight states (Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia) that had no data available.

according to estimates from the American Lung Association.

Oregon’s rate comes in at 557 per 10,000 population under the age of 18 years, just ahead of Montana at 574 per 10,000 and Iowa at 577. The prevalence of pediatric asthma in Alabama is 1,315 per 10,000, with North Carolina (1,149), Connecticut (1,107), Hawaii (1,026), and New York (1,005) joining it as members of the over-1,000 club. (MDedge News used the ALA’s estimates for persons under age 18 years with asthma in each state and Census Bureau estimates for population to calculate an unadjusted rate for each state.)

The ALA analysis was based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Behavioral System surveys for 2016 (31 states), 2015 (District of Columbia, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Texas), 2014 (Alabama, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia), 2012 (North Dakota and Wyoming), and 2011 (Iowa). National data were used for eight states (Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia) that had no data available.

Recommendations to Improve Asthma Outcomes: Work Group Call to Action

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

Click here to read the supplement.

What can be done to address the burden of asthma beyond pharmacotherapy? A panel of experts discuss steps for addressing sensitization to allergens that trigger increased asthma burden.

Topics Include:

- Identifying Patients with Allergic Components of Asthma

- Identifying and Addressing Allergen Exposure in Daily Practice

- The Opportunity for Payers and Health Systems for Supporting Trigger Avoidance Education

Click here to read the supplement.

Community-based therapy improved asthma outcomes in African American teens

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) significantly improved outcomes in African American adolescents with moderate to severe asthma.

Major finding: Patients randomly assigned to MST-HC treatment had greater improvement in FEV1 over time, compared with controls (beta = 0.097; t(164.27) = 2.52; P = .01).

Study details: A study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, randomly assigned to either MST-HC or FS.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate multisystemic therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

ED key to reducing pediatric asthma x-rays

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – but accomplishing this goal takes more than a new clinical practice guideline, according to a quality improvement team at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The team eventually reduced the chest x-ray rate for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day all-cause readmissions, but it took some sleuthing in the ED and good relations with staff. “We were way out in left field when we started this. Working in silos is never ideal,” said senior project member David Johnson, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt.

It’s been known for a while that chest x-rays are almost always a waste of time and money for asthma exacerbations, and national guidelines recommend against them. X-rays don’t improve outcomes and needlessly expose children to radiation.

In 2014, some of the providers at Vanderbilt, which has about 1,700 asthma encounters a year, realized that the institution’s 30% x-ray rate was a problem. The quality improvement team hoped a new guideline would address the issue, but that didn’t happen. “We roll out clinical practice guidelines” from on high, “and think people will magically change their behavior,” but they don’t, Dr. Johnson said at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The guideline was not being fully implemented. So the team asked the ED what was the standard procedure for a child presenting with asthma exacerbation. It turned out that the ED had a dyspnea order set that the team ”had no idea existed.” Chest x-rays were at the top of the list; next came blood gases, ventilation-perfusion scans, and leg Dopplers, he said.

The investigators tried to get rid of the whole order set but were unsuccessful. The ED department did, however, let the team eliminate chest x-rays in the default order set in July 2015. That helped, but more changes were needed.

The next conversation was to figure out why x-rays were being ordered in the first place. ED staff said they were worried about missing something, especially pneumonia. They also thought they were helping hospitalists by getting x-rays before sending kids to the ward even though, in reality, it didn’t matter whether x-rays were done a few hours later on the floor. ED providers also said that ill-appearing children often got better after a few hours but were kept back from discharge because x-ray results were still pending and that sometimes these results revealed problems at 3 a.m. that had nothing to do with why the patients were in the ED but still required a work-up.

This discussion opened a door. The ED staff didn’t want to order unnecessary x-rays, either. That led to talks about letting kids declare themselves a bit before x-rays were ordered. ED staff liked the idea, so the guidelines were updated in early 2016 to say that chest x-rays should only be ordered if there is persistent severe respiratory distress with hypoxia, there are focal findings that don’t improve after 12 hours of treatment, or there were concerns for pneumomediastinum or collapsed lung. The updated guidelines were posted in work areas and brought home by resident education. A reminder was added to the electronic medical record system that popped up when someone tried to order a chest x-ray for an child with asthma.

It worked. Chest x-ray rates in asthma fell to 15%, and have remained there since.

“We gave them permission to take their foot off the throttle and wait a little bit, and we don’t have more kids bouncing back from reduced x-rays.” The approach is “probably generalizable everywhere,” Dr. Johnson said.

It was essential that an ED fellow, Caroline Watnick, MD, led the effort and eventually bridged the gap between hospitalists and ED providers. In the end, “the change wasn’t something from the outside,” Dr. Johnson said.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Johnson didn’t have any disclosures. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point: Reduction of chest x-rays for routine pediatric asthma exacerbations in the ED can be accomplished with a team effort.

Major finding: A team project reduced x-rays for pediatric asthma exacerbations from 30% to 15% without increasing 3-day, all-cause readmissions.

Study details: Pre/post quality improvement analysis of asthma encounters in the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Nashville, Tenn., starting in 2014.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding, and the presenter didn’t have any disclosures.

Asthma medication ratio identifies high-risk pediatric patients

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point: The asthma medication ratio is useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

Major finding: About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5, meaning they were at high risk for acute exacerbations.

Study details: Review of more than 200,000 pediatric asthma patients on Medicaid

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. The study lead had no disclosures.

New guidance offered for managing poorly controlled asthma in children

published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

“Although many children with asthma achieve symptom control with appropriate management, a substantial subset does not,” Bradley E. Chipps, MD, from the Capital Allergy & Respiratory Disease Center in Sacramento, Calif., and his colleagues wrote in the recommendations sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “These children should undergo a step-up in care, but when and how to do that is not always straightforward. The Pediatric Asthma Yardstick is a practical resource for starting or adjusting controller therapy based on the options that are currently available for children, from infants to 18 years of age.”

In their recommendations, the authors grouped patients into age ranges of adolescent (12-18 years), school aged (6-11 years), and young children (5 years and under) as well as severity classifications.

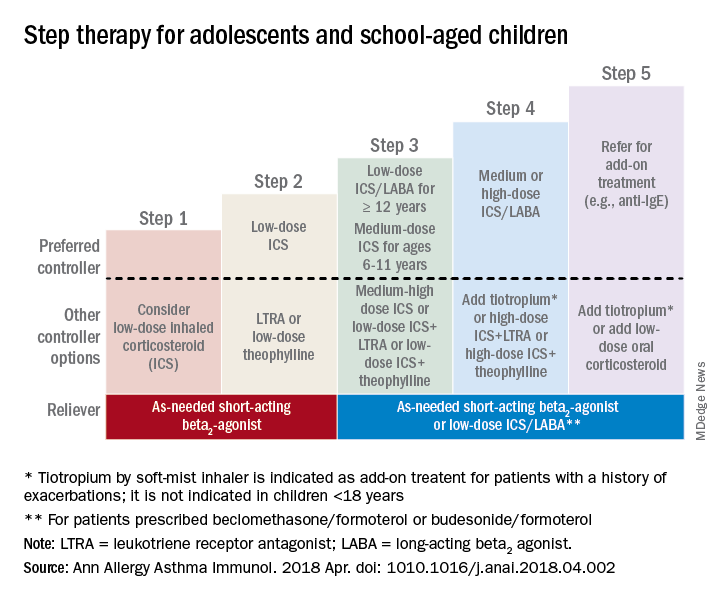

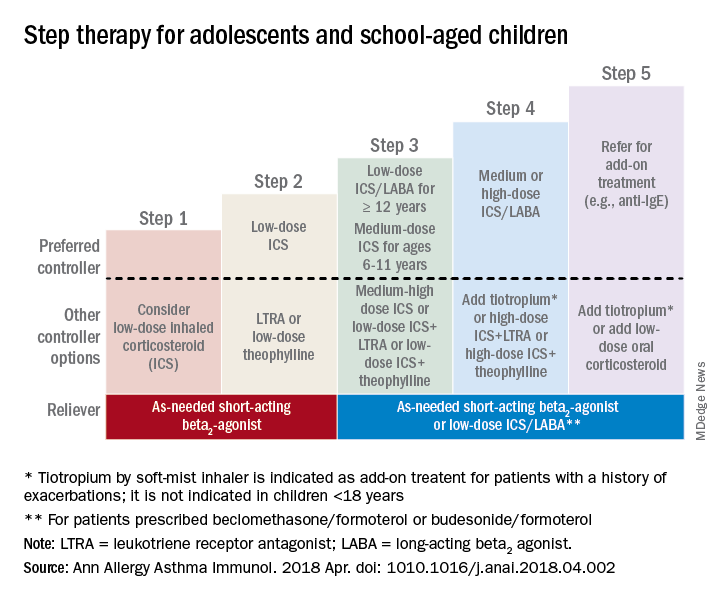

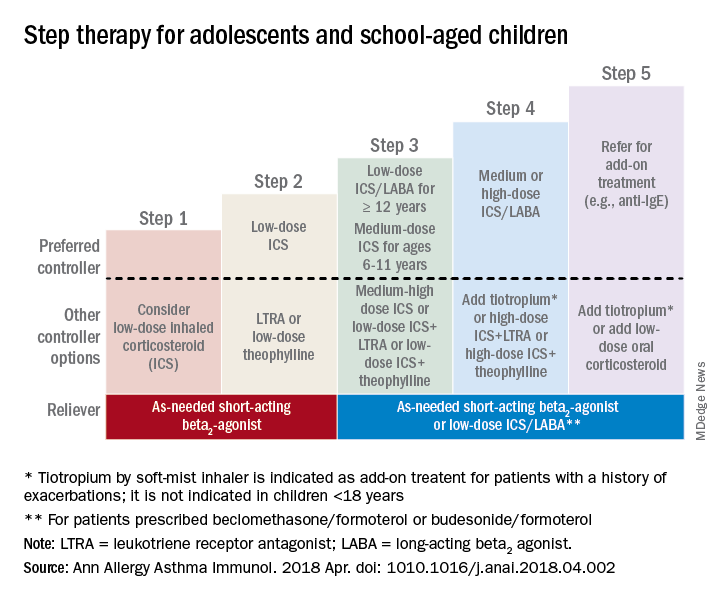

Adolescents and school-aged children

For adolescents and school-aged children, step 1 was classified as intermittent asthma that can be controlled with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) for as-needed relief. Children considered for stepping up to the next therapy should show symptoms of mild persistent asthma that the authors recommended controlling with low-dose ICS, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or low-dose theophylline with as-needed SABA.

In children 12-18 years with moderate persistent asthma (step 3), the authors recommended a combination of low-dose ICA and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA), while children 6-11 years should receive a medium dose of ICS; other considerations for school-aged children include a medium-high dose of ICS, a low-dose combination of ICS and LTRA, or low-dose ICS together with theophylline.

Adolescent or school-aged children with severe persistent asthma (step 4) should take a medium or high dose of ICS together with LABA, with the authors recommending adding tiotropium to a soft mist inhaler, combination high-dose ICS and LTRA, or a combination high-dose ICS and theophylline.

Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended children stepping up therapy beyond severe persistent asthma (step 5) should add on treatment such as low-dose oral corticosteroids, anti-immunoglobulin E therapy, and adding tiotropium to a soft-mist inhaler.

For adolescent and school-aged children going to steps 3-5, Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended prescribing as needed a short-acting beta2 agonist or low-dose ICS/LABA.

Children 5 years and younger

In children 5 years and younger, intermittent asthma (step 1) should be considered if the child has infrequent or viral wheezing but few or no symptoms in the interim that can be controlled with as-needed SABA. These young children who show symptoms of mild persistent asthma (step 2) can be treated with daily low-dose ICS, with other controller options of LTRA or intermittent ICS.

Stepping up therapy from mild to moderate persistent asthma (step 3), young children should receive double the daily dose of low-dose ICS from the previous step or use the low-dose ICS together with LTRA; if children show symptoms of severe persistent asthma (step 4), they should continue their daily controller and be referred to a specialist; other considerations for controllers at this step included adding LTRA, adding intermittent ICS, or increasing ICS frequency.

Other factors to consider

Inconsistencies in response to medication can occur because of comorbid conditions such as obesity, rhinosinusitis, respiratory infection or gastroesophageal reflux; suboptimal inhaled drug delivery; or failure to comply with treatment because of not wanting to take medication (common in adolescents), belief that even controller medicine can be taken intermittently, family stress, cost including lack of insurance or medication not covered by insurance. “Before adjusting therapy, it is important to ensure that the child’s change in symptoms is due to asthma and not to any of these factors that need to be addressed,” Dr. Chipps and his colleagues wrote.

Collaboration among children, their parents, and clinicians is needed to achieve good asthma control because of the “variable presentation within individuals and within the population of children affected” with asthma, they wrote.

The article summarizing the guidelines was sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Most of the authors report various financial relationships with companies including AstraZeneca, Aerocrine, Aviragen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Circassia, Commense, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Greer, Meda, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Patara, Regeneron, Sanofi, TEVA, Theravance, and Vectura Group. Dr. Farrar and Dr. Szefler had no financial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Chipps BE et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Apr. doi: 1010.1016/j.anai.2018.04.002.

published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

“Although many children with asthma achieve symptom control with appropriate management, a substantial subset does not,” Bradley E. Chipps, MD, from the Capital Allergy & Respiratory Disease Center in Sacramento, Calif., and his colleagues wrote in the recommendations sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “These children should undergo a step-up in care, but when and how to do that is not always straightforward. The Pediatric Asthma Yardstick is a practical resource for starting or adjusting controller therapy based on the options that are currently available for children, from infants to 18 years of age.”

In their recommendations, the authors grouped patients into age ranges of adolescent (12-18 years), school aged (6-11 years), and young children (5 years and under) as well as severity classifications.

Adolescents and school-aged children

For adolescents and school-aged children, step 1 was classified as intermittent asthma that can be controlled with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) for as-needed relief. Children considered for stepping up to the next therapy should show symptoms of mild persistent asthma that the authors recommended controlling with low-dose ICS, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or low-dose theophylline with as-needed SABA.

In children 12-18 years with moderate persistent asthma (step 3), the authors recommended a combination of low-dose ICA and a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA), while children 6-11 years should receive a medium dose of ICS; other considerations for school-aged children include a medium-high dose of ICS, a low-dose combination of ICS and LTRA, or low-dose ICS together with theophylline.

Adolescent or school-aged children with severe persistent asthma (step 4) should take a medium or high dose of ICS together with LABA, with the authors recommending adding tiotropium to a soft mist inhaler, combination high-dose ICS and LTRA, or a combination high-dose ICS and theophylline.

Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended children stepping up therapy beyond severe persistent asthma (step 5) should add on treatment such as low-dose oral corticosteroids, anti-immunoglobulin E therapy, and adding tiotropium to a soft-mist inhaler.

For adolescent and school-aged children going to steps 3-5, Dr. Chipps and his coauthors recommended prescribing as needed a short-acting beta2 agonist or low-dose ICS/LABA.

Children 5 years and younger

In children 5 years and younger, intermittent asthma (step 1) should be considered if the child has infrequent or viral wheezing but few or no symptoms in the interim that can be controlled with as-needed SABA. These young children who show symptoms of mild persistent asthma (step 2) can be treated with daily low-dose ICS, with other controller options of LTRA or intermittent ICS.

Stepping up therapy from mild to moderate persistent asthma (step 3), young children should receive double the daily dose of low-dose ICS from the previous step or use the low-dose ICS together with LTRA; if children show symptoms of severe persistent asthma (step 4), they should continue their daily controller and be referred to a specialist; other considerations for controllers at this step included adding LTRA, adding intermittent ICS, or increasing ICS frequency.

Other factors to consider

Inconsistencies in response to medication can occur because of comorbid conditions such as obesity, rhinosinusitis, respiratory infection or gastroesophageal reflux; suboptimal inhaled drug delivery; or failure to comply with treatment because of not wanting to take medication (common in adolescents), belief that even controller medicine can be taken intermittently, family stress, cost including lack of insurance or medication not covered by insurance. “Before adjusting therapy, it is important to ensure that the child’s change in symptoms is due to asthma and not to any of these factors that need to be addressed,” Dr. Chipps and his colleagues wrote.

Collaboration among children, their parents, and clinicians is needed to achieve good asthma control because of the “variable presentation within individuals and within the population of children affected” with asthma, they wrote.

The article summarizing the guidelines was sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Most of the authors report various financial relationships with companies including AstraZeneca, Aerocrine, Aviragen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Circassia, Commense, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Greer, Meda, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Patara, Regeneron, Sanofi, TEVA, Theravance, and Vectura Group. Dr. Farrar and Dr. Szefler had no financial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Chipps BE et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Apr. doi: 1010.1016/j.anai.2018.04.002.

published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

“Although many children with asthma achieve symptom control with appropriate management, a substantial subset does not,” Bradley E. Chipps, MD, from the Capital Allergy & Respiratory Disease Center in Sacramento, Calif., and his colleagues wrote in the recommendations sponsored by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “These children should undergo a step-up in care, but when and how to do that is not always straightforward. The Pediatric Asthma Yardstick is a practical resource for starting or adjusting controller therapy based on the options that are currently available for children, from infants to 18 years of age.”

In their recommendations, the authors grouped patients into age ranges of adolescent (12-18 years), school aged (6-11 years), and young children (5 years and under) as well as severity classifications.