User login

Managing geriatric bipolar disorder

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

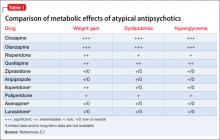

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

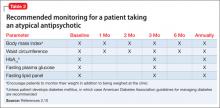

Recommended monitoring

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

Recommended monitoring

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

Recommended monitoring

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.

Eating disorder as an episode heralding in bipolar

The relationship between binge eating disorder and bipolar disorder is underappreciated in psychiatry. In fact, after many years of practice, I would submit that bipolar disorder can present as an episode of eating disorder. Failing to make this possible connection can have serious implications for our patients. If bipolar disorder is actually the diagnosis in these cases, treating them with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can lead to poor outcomes.

Several studies have explored the possible connection between bipolar disorder and eating disorder. One involving 717 patients with bipolar disorder who were participating in the Mayo Clinic Bipolar Biobank found that among patients with bipolar disorder, binge eating disorder and obesity are highly prevalent and correlated. The investigators went on to suggest that bipolar disorder and binge eating disorder "may represent a clinically important sub-phenotype" (J. Affect. Disord. 2013 June 3 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.024]).

Another study of 875 outpatients with DSM-IV bipolar I or II found that more than 14% of them met the criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime eating disorder. The most common was binge eating disorder (J. Affect. Disord. 2011;128:191-8). However, these cases did not make the connection that eating disorder might be an episode heralding in bipolar disorder.

One of my own patients, whom I will call Miss G.,* fits one of those categories.

A complex presentation

I first saw Miss G. in spring 2010. She was aged 16 years and 6 months, stood at 5 feet, 8 inches tall, and was fairly built. She had acne on her face and looked more mature than her age.

The adolescent was an only child and lived with her parents. (Her father drove her to my office for almost all of her appointments.) She was in high school, and worked as a waitress and a cashier at a drugstore. She reported that she had good friends and denied any history of abuse. She had been called "chubby" and "fat," starting at the very early age of 7, but denied feeling sad or crying about being called fat – and never had to defend herself about it.

During the first visit, she described her problem this way: "I get anxious in the middle of the day (and) get hyped up at night." She said she had been diagnosed with eating disorder and had been getting treatment by a therapist for the past 4 years. She reported symptoms of excessive eating, bingeing, and then purging more than 2-10 times a day.

In fifth grade, her crash dieting had begun, which escalated into excessive eating, followed by purging, calorie counting, and excessive use of treadmills and other equipment at a gym in an effort to lose weight. At her lowest weight, she succeeded in getting down to 113 pounds. At her highest, she reached 150.

In her sophomore year, she said that the severity of her illness had led to fainting because of low potassium levels and hypotension requiring frequent visits and treatment in the emergency department to balance her electrolytes. She also reported having panic attacks, which had lessened over the last 2 years. She reported undergoing weekly blood tests for electrolytes and presently was within normal limits. She assured me that the problems leading to her fainting would never happen again. Although Miss G. had been under the treatment of a therapist, she was not under that therapist’s care when she came to see me. It seems that one day, Miss G. walked out of the therapist’s office in anger and was now feeling embarrassed about going back to her.

I continued to explore Miss G.’s symptoms further, which revealed a decreased focus and attention, with a dramatic drop in recent months in school performance, from straight As to Bs, and eventually, to Cs.

In subsequent sessions, the patient admitted to having gone days without sleeping at night and described having excessive energy, "craving for movement," stay(ing) awake, hyper, constant movement, action, happiness, cutting myself." At one point, she said, "I was giddy and buzzing on some weird high and had an impulse to throw up food."

Also during that year, Miss G. said she had "graffitied many parks, shoplifted food, eaten it, and then thrown it up, gotten caught dining and dashing at night." Then there were times when she would just "sit at home and cry – and have no motivation to go out."

In describing her symptoms after many months, she said: "I was depressed before anything started. I hated myself." She denied hearing any voices but admitted to hearing her own voice. "At times, it would start screaming," she said. The patient denied having ever made serious suicidal attempts but had constant thoughts of killing herself by hanging or cutting her wrists 4 months prior to her first visit with me.

Miss G. also had taken an overdose of aspirin, up to 7 grams in 15 hours, and was disappointed to learn that the dose was not lethal. She admitted to using multiple drugs, including alcohol, marijuana, heroin, cocaine, cigarettes, caffeine, and amphetamines to control her moods and behavior in the past. But she had never been treated with psychotropics.

Her family history proved significant. One of her great grandfathers had committed suicide, and a maternal aunt was in treatment with several psychotropics and was on disability.

My initial diagnoses

Initially, I diagnosed this patient with eating disorder, bulimic type; eating disorder not otherwise specified; and polysubstance dependence in early remission with multiple rule-outs, including anxiety disorder NOS; psychotic disorder, NOS; bipolar disorder NOS; and bipolar disorder with psychosis. I explained to her the diagnosis and my concern about the possibility of mood swings and the risk of being on SSRIs or other antidepressants that are commonly prescribed for eating disorders, and that can worsen what I suspected was underlying bipolar disorder, and alter the course and treatment outcome – and the overall clinical outcome. She really did not care about the diagnosis or the treatment and was willing to take any medication that would not cause weight gain. She agreed to take topiramate and adamantly decided against taking anything else.

On subsequent visits, she reported worsening of concentration and anger but insisted on continuing on the topiramate because it had lowered her appetite and her bingeing and purging behavior had become less frequent.

At this point, I confirmed the diagnosis as bipolar disorder and had her agree to take lamotrigine. She continued to experience anger and mood swings, although she was taking 300 mg of lamotrigine. Risperidone had no therapeutic response. Although it proved difficult to persuade her to take sodium valproate she agreed, because she understood the consequences of her anger. Miss G. knew that continuing to behave disrespectfully toward her teachers would jeopardize her education and her future.

To elaborate on the time frames, let me point out that Miss G. started on the topiramate on the first day of her treatment. The lamotrigine was started the following month. The sodium valproate was introduced about 7 months after that with improvement, but she continued to complain of weight gain and appetite, which was not controlled – even with an H-2 blocker. So I had to stop the sodium valproate 4 months after it was introduced. Her concentration continued to either decline or not improve with mood stabilization.

This is the point at which I introduced clonidine. Although Miss G. did experience some side effects, her concentration improved. Her mood remained fairly stable on lamotrigine and clonidine after I discontinued the sodium valproate.

My last session with Miss G. occurred about 1 year and 3.5 months after the first visit. On that day, she was casually but neatly dressed. She told me that she would be graduating from high school and attending college out of state.

When I asked her about some of the behaviors tied to her eating disorder, she said "not at all" but after further exploration she said "once or twice a week; it became a lifestyle and right now, it is not a lifestyle anymore," she said. Miss G. went on to describe her current weight of 145 as "ideal," but said she still struggled to see herself in a healthy way. "By being treated for my bipolar disorder, my eating disorder did not reach such a low point," she said. "I consider myself a recovered eating disorder patient."

Her mood was good and her affect appropriate. She said she had no thoughts of harming herself.

We must get this right

Most prior patients with a diagnosis of eating disorder come to my office on SSRIs with poor functioning and symptom control. Initially, they say, "You are the doctor; whatever you say," but in the end, they either failed to accept the diagnosis of bipolar disorder or to follow my treatment recommendations and left my practice. In each of these cases, I have been concerned that these patients with eating disorder diagnoses might indeed have bipolar disorder.

As I mentioned earlier, some studies have been conducted exploring the connections between eating disorder and bipolar disorder, but more are needed. Specifically, we need to determine the extent to which eating disorder and bipolar disorder are comorbidities – or whether eating disorder is an episode that leads to bipolar disorder. In addition, we must compare the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with SSRIs for eating disorder with the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with mood stabilizers – even if they have started episodes of eating disorder.

Finally, organized psychiatry must establish guidelines and develop tools for the proper diagnosis of bipolar disorder, even if eating disorder episodes are already under way.

*Miss G. enthusiastically gave her permission to publish these details about her treatment and even offered to allow me to use her full name, if doing so might help others get proper diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Khoshnu is a general adult psychiatrist who is mostly in private practice in the West Caldwell and Somerset, N.J., areas. She also is affiliated with Overlook Hospital in Summit, N.J.

The relationship between binge eating disorder and bipolar disorder is underappreciated in psychiatry. In fact, after many years of practice, I would submit that bipolar disorder can present as an episode of eating disorder. Failing to make this possible connection can have serious implications for our patients. If bipolar disorder is actually the diagnosis in these cases, treating them with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can lead to poor outcomes.

Several studies have explored the possible connection between bipolar disorder and eating disorder. One involving 717 patients with bipolar disorder who were participating in the Mayo Clinic Bipolar Biobank found that among patients with bipolar disorder, binge eating disorder and obesity are highly prevalent and correlated. The investigators went on to suggest that bipolar disorder and binge eating disorder "may represent a clinically important sub-phenotype" (J. Affect. Disord. 2013 June 3 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.024]).

Another study of 875 outpatients with DSM-IV bipolar I or II found that more than 14% of them met the criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime eating disorder. The most common was binge eating disorder (J. Affect. Disord. 2011;128:191-8). However, these cases did not make the connection that eating disorder might be an episode heralding in bipolar disorder.

One of my own patients, whom I will call Miss G.,* fits one of those categories.

A complex presentation

I first saw Miss G. in spring 2010. She was aged 16 years and 6 months, stood at 5 feet, 8 inches tall, and was fairly built. She had acne on her face and looked more mature than her age.

The adolescent was an only child and lived with her parents. (Her father drove her to my office for almost all of her appointments.) She was in high school, and worked as a waitress and a cashier at a drugstore. She reported that she had good friends and denied any history of abuse. She had been called "chubby" and "fat," starting at the very early age of 7, but denied feeling sad or crying about being called fat – and never had to defend herself about it.

During the first visit, she described her problem this way: "I get anxious in the middle of the day (and) get hyped up at night." She said she had been diagnosed with eating disorder and had been getting treatment by a therapist for the past 4 years. She reported symptoms of excessive eating, bingeing, and then purging more than 2-10 times a day.

In fifth grade, her crash dieting had begun, which escalated into excessive eating, followed by purging, calorie counting, and excessive use of treadmills and other equipment at a gym in an effort to lose weight. At her lowest weight, she succeeded in getting down to 113 pounds. At her highest, she reached 150.

In her sophomore year, she said that the severity of her illness had led to fainting because of low potassium levels and hypotension requiring frequent visits and treatment in the emergency department to balance her electrolytes. She also reported having panic attacks, which had lessened over the last 2 years. She reported undergoing weekly blood tests for electrolytes and presently was within normal limits. She assured me that the problems leading to her fainting would never happen again. Although Miss G. had been under the treatment of a therapist, she was not under that therapist’s care when she came to see me. It seems that one day, Miss G. walked out of the therapist’s office in anger and was now feeling embarrassed about going back to her.

I continued to explore Miss G.’s symptoms further, which revealed a decreased focus and attention, with a dramatic drop in recent months in school performance, from straight As to Bs, and eventually, to Cs.

In subsequent sessions, the patient admitted to having gone days without sleeping at night and described having excessive energy, "craving for movement," stay(ing) awake, hyper, constant movement, action, happiness, cutting myself." At one point, she said, "I was giddy and buzzing on some weird high and had an impulse to throw up food."

Also during that year, Miss G. said she had "graffitied many parks, shoplifted food, eaten it, and then thrown it up, gotten caught dining and dashing at night." Then there were times when she would just "sit at home and cry – and have no motivation to go out."

In describing her symptoms after many months, she said: "I was depressed before anything started. I hated myself." She denied hearing any voices but admitted to hearing her own voice. "At times, it would start screaming," she said. The patient denied having ever made serious suicidal attempts but had constant thoughts of killing herself by hanging or cutting her wrists 4 months prior to her first visit with me.

Miss G. also had taken an overdose of aspirin, up to 7 grams in 15 hours, and was disappointed to learn that the dose was not lethal. She admitted to using multiple drugs, including alcohol, marijuana, heroin, cocaine, cigarettes, caffeine, and amphetamines to control her moods and behavior in the past. But she had never been treated with psychotropics.

Her family history proved significant. One of her great grandfathers had committed suicide, and a maternal aunt was in treatment with several psychotropics and was on disability.

My initial diagnoses

Initially, I diagnosed this patient with eating disorder, bulimic type; eating disorder not otherwise specified; and polysubstance dependence in early remission with multiple rule-outs, including anxiety disorder NOS; psychotic disorder, NOS; bipolar disorder NOS; and bipolar disorder with psychosis. I explained to her the diagnosis and my concern about the possibility of mood swings and the risk of being on SSRIs or other antidepressants that are commonly prescribed for eating disorders, and that can worsen what I suspected was underlying bipolar disorder, and alter the course and treatment outcome – and the overall clinical outcome. She really did not care about the diagnosis or the treatment and was willing to take any medication that would not cause weight gain. She agreed to take topiramate and adamantly decided against taking anything else.

On subsequent visits, she reported worsening of concentration and anger but insisted on continuing on the topiramate because it had lowered her appetite and her bingeing and purging behavior had become less frequent.

At this point, I confirmed the diagnosis as bipolar disorder and had her agree to take lamotrigine. She continued to experience anger and mood swings, although she was taking 300 mg of lamotrigine. Risperidone had no therapeutic response. Although it proved difficult to persuade her to take sodium valproate she agreed, because she understood the consequences of her anger. Miss G. knew that continuing to behave disrespectfully toward her teachers would jeopardize her education and her future.

To elaborate on the time frames, let me point out that Miss G. started on the topiramate on the first day of her treatment. The lamotrigine was started the following month. The sodium valproate was introduced about 7 months after that with improvement, but she continued to complain of weight gain and appetite, which was not controlled – even with an H-2 blocker. So I had to stop the sodium valproate 4 months after it was introduced. Her concentration continued to either decline or not improve with mood stabilization.

This is the point at which I introduced clonidine. Although Miss G. did experience some side effects, her concentration improved. Her mood remained fairly stable on lamotrigine and clonidine after I discontinued the sodium valproate.

My last session with Miss G. occurred about 1 year and 3.5 months after the first visit. On that day, she was casually but neatly dressed. She told me that she would be graduating from high school and attending college out of state.

When I asked her about some of the behaviors tied to her eating disorder, she said "not at all" but after further exploration she said "once or twice a week; it became a lifestyle and right now, it is not a lifestyle anymore," she said. Miss G. went on to describe her current weight of 145 as "ideal," but said she still struggled to see herself in a healthy way. "By being treated for my bipolar disorder, my eating disorder did not reach such a low point," she said. "I consider myself a recovered eating disorder patient."

Her mood was good and her affect appropriate. She said she had no thoughts of harming herself.

We must get this right

Most prior patients with a diagnosis of eating disorder come to my office on SSRIs with poor functioning and symptom control. Initially, they say, "You are the doctor; whatever you say," but in the end, they either failed to accept the diagnosis of bipolar disorder or to follow my treatment recommendations and left my practice. In each of these cases, I have been concerned that these patients with eating disorder diagnoses might indeed have bipolar disorder.

As I mentioned earlier, some studies have been conducted exploring the connections between eating disorder and bipolar disorder, but more are needed. Specifically, we need to determine the extent to which eating disorder and bipolar disorder are comorbidities – or whether eating disorder is an episode that leads to bipolar disorder. In addition, we must compare the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with SSRIs for eating disorder with the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with mood stabilizers – even if they have started episodes of eating disorder.

Finally, organized psychiatry must establish guidelines and develop tools for the proper diagnosis of bipolar disorder, even if eating disorder episodes are already under way.

*Miss G. enthusiastically gave her permission to publish these details about her treatment and even offered to allow me to use her full name, if doing so might help others get proper diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Khoshnu is a general adult psychiatrist who is mostly in private practice in the West Caldwell and Somerset, N.J., areas. She also is affiliated with Overlook Hospital in Summit, N.J.

The relationship between binge eating disorder and bipolar disorder is underappreciated in psychiatry. In fact, after many years of practice, I would submit that bipolar disorder can present as an episode of eating disorder. Failing to make this possible connection can have serious implications for our patients. If bipolar disorder is actually the diagnosis in these cases, treating them with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can lead to poor outcomes.

Several studies have explored the possible connection between bipolar disorder and eating disorder. One involving 717 patients with bipolar disorder who were participating in the Mayo Clinic Bipolar Biobank found that among patients with bipolar disorder, binge eating disorder and obesity are highly prevalent and correlated. The investigators went on to suggest that bipolar disorder and binge eating disorder "may represent a clinically important sub-phenotype" (J. Affect. Disord. 2013 June 3 [doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.024]).

Another study of 875 outpatients with DSM-IV bipolar I or II found that more than 14% of them met the criteria for at least one comorbid lifetime eating disorder. The most common was binge eating disorder (J. Affect. Disord. 2011;128:191-8). However, these cases did not make the connection that eating disorder might be an episode heralding in bipolar disorder.

One of my own patients, whom I will call Miss G.,* fits one of those categories.

A complex presentation

I first saw Miss G. in spring 2010. She was aged 16 years and 6 months, stood at 5 feet, 8 inches tall, and was fairly built. She had acne on her face and looked more mature than her age.

The adolescent was an only child and lived with her parents. (Her father drove her to my office for almost all of her appointments.) She was in high school, and worked as a waitress and a cashier at a drugstore. She reported that she had good friends and denied any history of abuse. She had been called "chubby" and "fat," starting at the very early age of 7, but denied feeling sad or crying about being called fat – and never had to defend herself about it.

During the first visit, she described her problem this way: "I get anxious in the middle of the day (and) get hyped up at night." She said she had been diagnosed with eating disorder and had been getting treatment by a therapist for the past 4 years. She reported symptoms of excessive eating, bingeing, and then purging more than 2-10 times a day.

In fifth grade, her crash dieting had begun, which escalated into excessive eating, followed by purging, calorie counting, and excessive use of treadmills and other equipment at a gym in an effort to lose weight. At her lowest weight, she succeeded in getting down to 113 pounds. At her highest, she reached 150.

In her sophomore year, she said that the severity of her illness had led to fainting because of low potassium levels and hypotension requiring frequent visits and treatment in the emergency department to balance her electrolytes. She also reported having panic attacks, which had lessened over the last 2 years. She reported undergoing weekly blood tests for electrolytes and presently was within normal limits. She assured me that the problems leading to her fainting would never happen again. Although Miss G. had been under the treatment of a therapist, she was not under that therapist’s care when she came to see me. It seems that one day, Miss G. walked out of the therapist’s office in anger and was now feeling embarrassed about going back to her.

I continued to explore Miss G.’s symptoms further, which revealed a decreased focus and attention, with a dramatic drop in recent months in school performance, from straight As to Bs, and eventually, to Cs.

In subsequent sessions, the patient admitted to having gone days without sleeping at night and described having excessive energy, "craving for movement," stay(ing) awake, hyper, constant movement, action, happiness, cutting myself." At one point, she said, "I was giddy and buzzing on some weird high and had an impulse to throw up food."

Also during that year, Miss G. said she had "graffitied many parks, shoplifted food, eaten it, and then thrown it up, gotten caught dining and dashing at night." Then there were times when she would just "sit at home and cry – and have no motivation to go out."

In describing her symptoms after many months, she said: "I was depressed before anything started. I hated myself." She denied hearing any voices but admitted to hearing her own voice. "At times, it would start screaming," she said. The patient denied having ever made serious suicidal attempts but had constant thoughts of killing herself by hanging or cutting her wrists 4 months prior to her first visit with me.

Miss G. also had taken an overdose of aspirin, up to 7 grams in 15 hours, and was disappointed to learn that the dose was not lethal. She admitted to using multiple drugs, including alcohol, marijuana, heroin, cocaine, cigarettes, caffeine, and amphetamines to control her moods and behavior in the past. But she had never been treated with psychotropics.

Her family history proved significant. One of her great grandfathers had committed suicide, and a maternal aunt was in treatment with several psychotropics and was on disability.

My initial diagnoses

Initially, I diagnosed this patient with eating disorder, bulimic type; eating disorder not otherwise specified; and polysubstance dependence in early remission with multiple rule-outs, including anxiety disorder NOS; psychotic disorder, NOS; bipolar disorder NOS; and bipolar disorder with psychosis. I explained to her the diagnosis and my concern about the possibility of mood swings and the risk of being on SSRIs or other antidepressants that are commonly prescribed for eating disorders, and that can worsen what I suspected was underlying bipolar disorder, and alter the course and treatment outcome – and the overall clinical outcome. She really did not care about the diagnosis or the treatment and was willing to take any medication that would not cause weight gain. She agreed to take topiramate and adamantly decided against taking anything else.

On subsequent visits, she reported worsening of concentration and anger but insisted on continuing on the topiramate because it had lowered her appetite and her bingeing and purging behavior had become less frequent.

At this point, I confirmed the diagnosis as bipolar disorder and had her agree to take lamotrigine. She continued to experience anger and mood swings, although she was taking 300 mg of lamotrigine. Risperidone had no therapeutic response. Although it proved difficult to persuade her to take sodium valproate she agreed, because she understood the consequences of her anger. Miss G. knew that continuing to behave disrespectfully toward her teachers would jeopardize her education and her future.

To elaborate on the time frames, let me point out that Miss G. started on the topiramate on the first day of her treatment. The lamotrigine was started the following month. The sodium valproate was introduced about 7 months after that with improvement, but she continued to complain of weight gain and appetite, which was not controlled – even with an H-2 blocker. So I had to stop the sodium valproate 4 months after it was introduced. Her concentration continued to either decline or not improve with mood stabilization.

This is the point at which I introduced clonidine. Although Miss G. did experience some side effects, her concentration improved. Her mood remained fairly stable on lamotrigine and clonidine after I discontinued the sodium valproate.

My last session with Miss G. occurred about 1 year and 3.5 months after the first visit. On that day, she was casually but neatly dressed. She told me that she would be graduating from high school and attending college out of state.

When I asked her about some of the behaviors tied to her eating disorder, she said "not at all" but after further exploration she said "once or twice a week; it became a lifestyle and right now, it is not a lifestyle anymore," she said. Miss G. went on to describe her current weight of 145 as "ideal," but said she still struggled to see herself in a healthy way. "By being treated for my bipolar disorder, my eating disorder did not reach such a low point," she said. "I consider myself a recovered eating disorder patient."

Her mood was good and her affect appropriate. She said she had no thoughts of harming herself.

We must get this right

Most prior patients with a diagnosis of eating disorder come to my office on SSRIs with poor functioning and symptom control. Initially, they say, "You are the doctor; whatever you say," but in the end, they either failed to accept the diagnosis of bipolar disorder or to follow my treatment recommendations and left my practice. In each of these cases, I have been concerned that these patients with eating disorder diagnoses might indeed have bipolar disorder.

As I mentioned earlier, some studies have been conducted exploring the connections between eating disorder and bipolar disorder, but more are needed. Specifically, we need to determine the extent to which eating disorder and bipolar disorder are comorbidities – or whether eating disorder is an episode that leads to bipolar disorder. In addition, we must compare the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with SSRIs for eating disorder with the treatment outcome and clinical course of patients who are treated with mood stabilizers – even if they have started episodes of eating disorder.

Finally, organized psychiatry must establish guidelines and develop tools for the proper diagnosis of bipolar disorder, even if eating disorder episodes are already under way.

*Miss G. enthusiastically gave her permission to publish these details about her treatment and even offered to allow me to use her full name, if doing so might help others get proper diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Khoshnu is a general adult psychiatrist who is mostly in private practice in the West Caldwell and Somerset, N.J., areas. She also is affiliated with Overlook Hospital in Summit, N.J.

Caregiver support program decreases dementia emergency visits

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – A pilot program that supports the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency admissions for those patients in San Francisco by more than 40% in 6 months, Elizabeth Edgerly, Ph.D., reported at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2013.

The preliminary analysis also found that caregivers reported significant improvements in 7 out of 10 quality of life and quality of care measures, according to Dr. Edgerly, chief program officer of the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada Chapter.

The early results paint an encouraging picture of the future, she said in an interview.

"We are very excited about the emergency utilization data. We’re always confident about our capacity to impact efficacy, but affecting service utilization is a tough nut to crack. The beauty of this is, if we can improve quality of care while reducing utilization costs, it may actually be cost neutral to have this kind of a dementia support program."

The association created its Excellence in Dementia Care program in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the city and county of San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco. The Administration on Aging also provided funding.

San Francisco was the perfect city for the pilot project, Dr. Edgerly said. "It’s the only city in the United States with a strategic plan related to dementia. It also has an elderly, diverse population and many of the residents live alone."

The pilot program is part of the city plan’s goal of partnering with other institutions to improve quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia. It was designed to improve dementia care by both enhancing services and educating caregivers.

"Kaiser hired a full-time social worker for just dementia support and who only worked with the caregivers," Dr. Edgerly said. The social worker conducted initial evaluations and assessments and created an individualized dementia care program that was uploaded into the electronic medical record of each patient, making the individualized program available to everyone on the patient’s care team. The social worker also called caregivers proactively to make sure the caregivers’ needs were being met and that they could access community services.

The Alzheimer’s Association provided dementia care support experts manning a 24-hour help line, a MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return bracelet for the patient, respite grants for day or evening supplemental care to give caregivers a break, and a support group where caregivers could meet to discusses their challenges.

The association also administered the educational portion of the program. The first component provided a primer on Alzheimer’s stage-by-stage effects on thinking, emotions, and behavior, and noted resources that were available for help. Caregivers also were informed about legal and financial planning and ways to keep a positive, safe, and compassionate home environment for as long as the patient could stay at home.

In surveys at baseline and after 6 months, caregivers rated their feelings about their abilities in 10 different areas: handling current patient problems in memory and behavior, handling future patient problems, dealing with their own frustrations, keeping the patient independent, caring for the patient as independently as possible, getting answers to patient problems, finding community organizations that provide answers, finding community organizations that provide services, getting answers to questions about services, independently arranging for services, and paying for services.

Overall, 92 of the 105 patient-caregiver dyads have completed the 6-month assessments, Dr. Edgerly said. The surveys indicated significant improvements on seven of the caregiver measures. Caregivers said they felt better able to handle concerns, to get information, and to obtain and pay for services.

Most importantly, the program led to about a 40% decrease in emergency department visits – a significant change, Dr. Edgerly said. There were also nonsignificant decreases in hospital length of stay, physician visits, and days spent in post–acute or long-term care facilities.

"Even the outcomes that didn’t improve significantly were all going in the right direction," Dr. Edgerly said, adding that she’s hoping for even better results when the data are analyzed in their entirety.

The program’s positive impact on health care resources could be enough to attract the interest of other insurers, she said. "If this intervention reduced expenses associated with hospital or emergency department visits, an insurer might see that as good business sense."

The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2013

Major finding: A program designed to support the caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients decreased emergency room visits by 40% over a 6-month period.

Data source: A program that integrated medical and social care and enrolled 105 caregiver-patient pairs.

Disclosures: The project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the National Institute on Aging.

CRTC1 polymorphisms affect BMI, novel study finds

Polymorphisms of the CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 gene contribute to the genetics of human obesity in psychiatric patients and in the general population, results from a novel study demonstrated.

Specifically, the CRTC1 nonsynonymous polymorphism rs3746266A>G was associated with body mass index in three independent psychiatric samples in which lower BMI values were measured in carriers of the G allele compared with noncarriers, while the protective effect of the T allele of rs6510997C>T (a proxy of rs3746266A>G) against fat accumulation also was observed in a large population-based sample.

"Psychiatric, psychological, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors, as well as heritability, have been shown to influence individual susceptibility to overweight or obesity, both in the general population and in psychiatric patients before and after treatment with potentially weight gain–inducing psychotropic drugs," researchers led by Eva Choong, Pharm.D., Ph.D., reported online Aug. 7 in JAMA Psychiatry. "Genome-wide association studies conducted to date only explain a small fraction of body mass index (BMI) heritability, and more obesity susceptibility genes remain to be discovered."

For the study, which is thought to be the first of its kind, researchers from two university hospitals and a private clinic in Switzerland evaluated the effect of three CRTC1 polymorphisms on BMI and/or fat mass in a cohort of 152 patients taking weight gain–inducing psychotropic drugs (sample 1). The CRTC1 variant that was significantly associated with BMI was then replicated in two independent psychiatric samples, which consisted of 174 patients in sample 2 and 118 patients in sample 3, and in two white population-based samples, which consisted of 5,338 patients in sample 4 and 123,865 patients in sample 5 (JAMA Psychiatry 2013 Aug. 7 [doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.187]).

The researchers found that in the three psychiatric samples, carriers of the CRTC1 rs3746266A>G allele had a lower BMI than did noncarriers (P = .001 in sample 1, P = .05 in sample 2, and P = .0003 in sample 3). In a combined analysis that excluded patients taking other weight gain–inducing drugs, G-allele carriers had a 1.81-kg/m2 lower BMI, compared with noncarriers (P less than .0001). The strongest association was seen in women age 45; in this subset of patients, G-allele carriers had a 3.87-kg/m2 lower BMI, compared with noncarriers (P less than .0001).

In the analysis of population-based samples, the T allele of rs651099C>T, which is a proxy of the G allele, was associated with lower BMI (P = .01 in sample 5) and fat mass (P = .03 in sample 4).

The investigators acknowledged several limitations of their study. For example, most patients were not drug naive and had already developed weight gain because of previous treatments. "It was therefore not possible to determine with certainty whether the strong association of CRTC1 genotypes with BMI and fat mass in psychiatric populations was due to the psychiatric illness and/or to the pharmacological treatment," they wrote. "Extensive hormonal measurements were not available for our samples, so the role of sex hormones on the association of CRTC1 variants with adiposity could not be explored."

In addition, the racial and ethnic makeup of the patients sampled means that the results are not generalizable.

Despite those limitations, Dr. Choong expressed optimism about where these results might lead. "Our results suggest that CRTC1 plays an important role in the high prevalence of overweight and obesity observed in psychiatric patients," she and her colleagues concluded. "Besides, CRTC1 could play a role in the genetics of obesity in the general population, thereby increasing our understanding of the multiple mechanisms influencing obesity.

"Finally, the strong associations of CRTC1 variants with adiposity in women younger than 45 years support further research on the interrelationship between adiposity and the reproductive function."

The study was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation and by the National Center of Competence in Research, which is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Choong had no disclosures; several of her colleagues disclosed that they have received grants or honoraria from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Polymorphisms of the CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 gene contribute to the genetics of human obesity in psychiatric patients and in the general population, results from a novel study demonstrated.

Specifically, the CRTC1 nonsynonymous polymorphism rs3746266A>G was associated with body mass index in three independent psychiatric samples in which lower BMI values were measured in carriers of the G allele compared with noncarriers, while the protective effect of the T allele of rs6510997C>T (a proxy of rs3746266A>G) against fat accumulation also was observed in a large population-based sample.

"Psychiatric, psychological, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors, as well as heritability, have been shown to influence individual susceptibility to overweight or obesity, both in the general population and in psychiatric patients before and after treatment with potentially weight gain–inducing psychotropic drugs," researchers led by Eva Choong, Pharm.D., Ph.D., reported online Aug. 7 in JAMA Psychiatry. "Genome-wide association studies conducted to date only explain a small fraction of body mass index (BMI) heritability, and more obesity susceptibility genes remain to be discovered."

For the study, which is thought to be the first of its kind, researchers from two university hospitals and a private clinic in Switzerland evaluated the effect of three CRTC1 polymorphisms on BMI and/or fat mass in a cohort of 152 patients taking weight gain–inducing psychotropic drugs (sample 1). The CRTC1 variant that was significantly associated with BMI was then replicated in two independent psychiatric samples, which consisted of 174 patients in sample 2 and 118 patients in sample 3, and in two white population-based samples, which consisted of 5,338 patients in sample 4 and 123,865 patients in sample 5 (JAMA Psychiatry 2013 Aug. 7 [doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.187]).