User login

FDA approves Doptelet for liver disease patients undergoing procedures

Doptelet (avatrombopag) is the first drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for thrombocytopenia in adults with chronic liver disease who are scheduled to undergo a medical or dental procedure, the FDA announced in a statement.

“Patients with chronic liver disease who have low platelet counts and require a procedure are at increased risk of bleeding,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Doptelet was demonstrated to safely increase the platelet count. This drug may decrease or eliminate the need for platelet transfusions, which are associated with risk of infection and other adverse reactions.”

The safety and efficacy of two different doses of Doptelet administered orally over 5 days, as compared with placebo, was studied in the ADAPT trials (ADAPT-1 and ADAPT-2) involving 435 patients with chronic liver disease and severe thrombocytopenia who were scheduled to undergo a procedure that would typically require platelet transfusion. At both dose levels of Doptelet, a higher proportion of patients had increased platelet counts and did not require platelet transfusion or any rescue therapy on the day of the procedure and up to 7 days following the procedure as compared with those treated with placebo.

The most common side effects reported by clinical trial participants who received Doptelet were fever, stomach (abdominal) pain, nausea, headache, fatigue and edema in the hands or feet. People with chronic liver disease and people with certain blood clotting conditions may have an increased risk of developing blood clots when taking Doptelet, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The FDA granted the Doptelet approval to AkaRx.

Doptelet (avatrombopag) is the first drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for thrombocytopenia in adults with chronic liver disease who are scheduled to undergo a medical or dental procedure, the FDA announced in a statement.

“Patients with chronic liver disease who have low platelet counts and require a procedure are at increased risk of bleeding,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Doptelet was demonstrated to safely increase the platelet count. This drug may decrease or eliminate the need for platelet transfusions, which are associated with risk of infection and other adverse reactions.”

The safety and efficacy of two different doses of Doptelet administered orally over 5 days, as compared with placebo, was studied in the ADAPT trials (ADAPT-1 and ADAPT-2) involving 435 patients with chronic liver disease and severe thrombocytopenia who were scheduled to undergo a procedure that would typically require platelet transfusion. At both dose levels of Doptelet, a higher proportion of patients had increased platelet counts and did not require platelet transfusion or any rescue therapy on the day of the procedure and up to 7 days following the procedure as compared with those treated with placebo.

The most common side effects reported by clinical trial participants who received Doptelet were fever, stomach (abdominal) pain, nausea, headache, fatigue and edema in the hands or feet. People with chronic liver disease and people with certain blood clotting conditions may have an increased risk of developing blood clots when taking Doptelet, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The FDA granted the Doptelet approval to AkaRx.

Doptelet (avatrombopag) is the first drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for thrombocytopenia in adults with chronic liver disease who are scheduled to undergo a medical or dental procedure, the FDA announced in a statement.

“Patients with chronic liver disease who have low platelet counts and require a procedure are at increased risk of bleeding,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Doptelet was demonstrated to safely increase the platelet count. This drug may decrease or eliminate the need for platelet transfusions, which are associated with risk of infection and other adverse reactions.”

The safety and efficacy of two different doses of Doptelet administered orally over 5 days, as compared with placebo, was studied in the ADAPT trials (ADAPT-1 and ADAPT-2) involving 435 patients with chronic liver disease and severe thrombocytopenia who were scheduled to undergo a procedure that would typically require platelet transfusion. At both dose levels of Doptelet, a higher proportion of patients had increased platelet counts and did not require platelet transfusion or any rescue therapy on the day of the procedure and up to 7 days following the procedure as compared with those treated with placebo.

The most common side effects reported by clinical trial participants who received Doptelet were fever, stomach (abdominal) pain, nausea, headache, fatigue and edema in the hands or feet. People with chronic liver disease and people with certain blood clotting conditions may have an increased risk of developing blood clots when taking Doptelet, the FDA said in a press release announcing the approval.

The FDA granted the Doptelet approval to AkaRx.

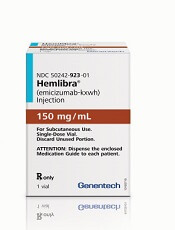

Emicizumab reduces bleeding in hemophilia A

GLASGOW—Final results from the HAVEN 3 study suggest emicizumab prophylaxis can reduce bleeding in hemophilia A patients without factor VIII inhibitors.

Compared to patients who did not receive prophylaxis, those who received emicizumab prophylaxis had a 96% to 97% reduction in treated bleeds and a 94% to 95% reduction in all bleeds.

An intra-patient comparison showed a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with once-weekly emicizumab, compared to prior factor VIII prophylaxis.

“[Emicizumab] is the first medicine to show superior efficacy to prior factor VIII prophylaxis, the current standard of care therapy, as demonstrated by a statistically significant reduction in treated bleeds in the HAVEN 3 study intra-patient comparison,” said Johnny Mahlangu, MB BCh, of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dr Mahlangu presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday. HAVEN 3 was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab in patients with hemophilia A without factor VIII inhibitors. The study included 152 patients who were 12 years of age or older and were previously treated with factor VIII therapy on-demand or as prophylaxis.

Patients previously treated with on-demand factor VIII were randomized in a 2:2:1 fashion to receive:

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm A, n=36)

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 3 mg/kg/2wks for at least 24 weeks (arm B, n=35)

- No prophylaxis, only episodic/on-demand factor VIII treatment (arm C, n=18).

Patients previously treated with factor VIII prophylaxis received emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm D, n=63).

Episodic treatment of breakthrough bleeds with factor VIII therapy was allowed per protocol.

Emicizumab vs no prophylaxis

The model-based (negative binomial regression model) annualized bleeding rate (ABR) for treated bleeds was 1.5 in arm A, 1.3 in arm B, and 38.2 in arm C. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 0 in arms A and B and 40.4 in arm C.

Compared to patients in arm C, those in arm A had a 96% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds, and those in arm B had a 97% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds.

None of the patients in arm C had 0 treated bleeds, compared to 55.6% of patients in arm A and 60% of patients in arm B.

The model-based ABR for all bleeds was 2.5 in arm A, 2.6 in arm B, and 47.6 in arm C.

Patients in arm A had a 95% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), and patients in arm B had a 94% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), compared to patients in arm C.

Fifty percent of patients in arm A had 0 total bleeds, as did 40% of patients in arm B and 0% of patients in arm C.

Intra-patient comparison

The researchers compared previous prophylaxis to once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis in 48 patients from arm D.

The model-based ABR for treated bleeds was 4.8 with prior prophylaxis and 1.5 with emicizumab. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 1.8 and 0.0, respectively.

Patients had a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with emicizumab (P<0.0001).

With prior prophylaxis, 39.6% of patients had 0 treated bleeds. With emicizumab, 54.2% of patients had 0 treated bleeds.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events (AEs) related to emicizumab, no anti-drug antibodies detected, and none of the patients on emicizumab developed de novo factor VIII inhibitors.

Injection-site reactions occurred in 25.3% of all patients (38/150), 25% of patients in arm A (9/36), 20% in arm B (7/35), 12.5% in arm C (2/16), and 31.7% in arm D (20/63).

An additional patient in arm D (who was included in the total) reported an “injection-site erythema,” not an “injection-site reaction.”

Upper respiratory tract infections occurred in 10.7% of all patients (n=16), 11.1% (n=4) of those in arm A, 11.4% (n=4) of those in arm B, 0% of those in arm C, and 12.7% (n=8) of those in arm D.

Other AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients were arthralgia (19%), nasopharyngitis (12%), headache (11%), and influenza (6%).

One patient in arm B discontinued emicizumab due to multiple mild AEs—insomnia, hair loss, nightmare, lethargy, depressed mood, headache, and pruritus.

Two patients were lost to follow-up—1 in arm A and 1 in arm C.

GLASGOW—Final results from the HAVEN 3 study suggest emicizumab prophylaxis can reduce bleeding in hemophilia A patients without factor VIII inhibitors.

Compared to patients who did not receive prophylaxis, those who received emicizumab prophylaxis had a 96% to 97% reduction in treated bleeds and a 94% to 95% reduction in all bleeds.

An intra-patient comparison showed a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with once-weekly emicizumab, compared to prior factor VIII prophylaxis.

“[Emicizumab] is the first medicine to show superior efficacy to prior factor VIII prophylaxis, the current standard of care therapy, as demonstrated by a statistically significant reduction in treated bleeds in the HAVEN 3 study intra-patient comparison,” said Johnny Mahlangu, MB BCh, of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dr Mahlangu presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday. HAVEN 3 was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab in patients with hemophilia A without factor VIII inhibitors. The study included 152 patients who were 12 years of age or older and were previously treated with factor VIII therapy on-demand or as prophylaxis.

Patients previously treated with on-demand factor VIII were randomized in a 2:2:1 fashion to receive:

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm A, n=36)

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 3 mg/kg/2wks for at least 24 weeks (arm B, n=35)

- No prophylaxis, only episodic/on-demand factor VIII treatment (arm C, n=18).

Patients previously treated with factor VIII prophylaxis received emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm D, n=63).

Episodic treatment of breakthrough bleeds with factor VIII therapy was allowed per protocol.

Emicizumab vs no prophylaxis

The model-based (negative binomial regression model) annualized bleeding rate (ABR) for treated bleeds was 1.5 in arm A, 1.3 in arm B, and 38.2 in arm C. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 0 in arms A and B and 40.4 in arm C.

Compared to patients in arm C, those in arm A had a 96% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds, and those in arm B had a 97% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds.

None of the patients in arm C had 0 treated bleeds, compared to 55.6% of patients in arm A and 60% of patients in arm B.

The model-based ABR for all bleeds was 2.5 in arm A, 2.6 in arm B, and 47.6 in arm C.

Patients in arm A had a 95% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), and patients in arm B had a 94% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), compared to patients in arm C.

Fifty percent of patients in arm A had 0 total bleeds, as did 40% of patients in arm B and 0% of patients in arm C.

Intra-patient comparison

The researchers compared previous prophylaxis to once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis in 48 patients from arm D.

The model-based ABR for treated bleeds was 4.8 with prior prophylaxis and 1.5 with emicizumab. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 1.8 and 0.0, respectively.

Patients had a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with emicizumab (P<0.0001).

With prior prophylaxis, 39.6% of patients had 0 treated bleeds. With emicizumab, 54.2% of patients had 0 treated bleeds.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events (AEs) related to emicizumab, no anti-drug antibodies detected, and none of the patients on emicizumab developed de novo factor VIII inhibitors.

Injection-site reactions occurred in 25.3% of all patients (38/150), 25% of patients in arm A (9/36), 20% in arm B (7/35), 12.5% in arm C (2/16), and 31.7% in arm D (20/63).

An additional patient in arm D (who was included in the total) reported an “injection-site erythema,” not an “injection-site reaction.”

Upper respiratory tract infections occurred in 10.7% of all patients (n=16), 11.1% (n=4) of those in arm A, 11.4% (n=4) of those in arm B, 0% of those in arm C, and 12.7% (n=8) of those in arm D.

Other AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients were arthralgia (19%), nasopharyngitis (12%), headache (11%), and influenza (6%).

One patient in arm B discontinued emicizumab due to multiple mild AEs—insomnia, hair loss, nightmare, lethargy, depressed mood, headache, and pruritus.

Two patients were lost to follow-up—1 in arm A and 1 in arm C.

GLASGOW—Final results from the HAVEN 3 study suggest emicizumab prophylaxis can reduce bleeding in hemophilia A patients without factor VIII inhibitors.

Compared to patients who did not receive prophylaxis, those who received emicizumab prophylaxis had a 96% to 97% reduction in treated bleeds and a 94% to 95% reduction in all bleeds.

An intra-patient comparison showed a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with once-weekly emicizumab, compared to prior factor VIII prophylaxis.

“[Emicizumab] is the first medicine to show superior efficacy to prior factor VIII prophylaxis, the current standard of care therapy, as demonstrated by a statistically significant reduction in treated bleeds in the HAVEN 3 study intra-patient comparison,” said Johnny Mahlangu, MB BCh, of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dr Mahlangu presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday. HAVEN 3 was sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab in patients with hemophilia A without factor VIII inhibitors. The study included 152 patients who were 12 years of age or older and were previously treated with factor VIII therapy on-demand or as prophylaxis.

Patients previously treated with on-demand factor VIII were randomized in a 2:2:1 fashion to receive:

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm A, n=36)

- Emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 3 mg/kg/2wks for at least 24 weeks (arm B, n=35)

- No prophylaxis, only episodic/on-demand factor VIII treatment (arm C, n=18).

Patients previously treated with factor VIII prophylaxis received emicizumab prophylaxis at 3 mg/kg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by 1.5 mg/kg/wk until the end of study (arm D, n=63).

Episodic treatment of breakthrough bleeds with factor VIII therapy was allowed per protocol.

Emicizumab vs no prophylaxis

The model-based (negative binomial regression model) annualized bleeding rate (ABR) for treated bleeds was 1.5 in arm A, 1.3 in arm B, and 38.2 in arm C. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 0 in arms A and B and 40.4 in arm C.

Compared to patients in arm C, those in arm A had a 96% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds, and those in arm B had a 97% (P<0.0001) reduction in treated bleeds.

None of the patients in arm C had 0 treated bleeds, compared to 55.6% of patients in arm A and 60% of patients in arm B.

The model-based ABR for all bleeds was 2.5 in arm A, 2.6 in arm B, and 47.6 in arm C.

Patients in arm A had a 95% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), and patients in arm B had a 94% reduction in all bleeds (P<0.0001), compared to patients in arm C.

Fifty percent of patients in arm A had 0 total bleeds, as did 40% of patients in arm B and 0% of patients in arm C.

Intra-patient comparison

The researchers compared previous prophylaxis to once-weekly emicizumab prophylaxis in 48 patients from arm D.

The model-based ABR for treated bleeds was 4.8 with prior prophylaxis and 1.5 with emicizumab. The median ABR for treated bleeds was 1.8 and 0.0, respectively.

Patients had a 68% reduction in treated bleeds with emicizumab (P<0.0001).

With prior prophylaxis, 39.6% of patients had 0 treated bleeds. With emicizumab, 54.2% of patients had 0 treated bleeds.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events (AEs) related to emicizumab, no anti-drug antibodies detected, and none of the patients on emicizumab developed de novo factor VIII inhibitors.

Injection-site reactions occurred in 25.3% of all patients (38/150), 25% of patients in arm A (9/36), 20% in arm B (7/35), 12.5% in arm C (2/16), and 31.7% in arm D (20/63).

An additional patient in arm D (who was included in the total) reported an “injection-site erythema,” not an “injection-site reaction.”

Upper respiratory tract infections occurred in 10.7% of all patients (n=16), 11.1% (n=4) of those in arm A, 11.4% (n=4) of those in arm B, 0% of those in arm C, and 12.7% (n=8) of those in arm D.

Other AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients were arthralgia (19%), nasopharyngitis (12%), headache (11%), and influenza (6%).

One patient in arm B discontinued emicizumab due to multiple mild AEs—insomnia, hair loss, nightmare, lethargy, depressed mood, headache, and pruritus.

Two patients were lost to follow-up—1 in arm A and 1 in arm C.

Structured PPH management cuts severe hemorrhage

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Key clinical point: Indicators of maternal morbidity decreased after a postpartum hemorrhage checklist was implemented.

Major finding: Severe postpartum hemorrhage rates fell from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

Study details: A prospective pre/post implementation study of 297 women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

Hydroxyurea in infancy yields better SCD outcomes

PITTSBURGH – Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) who were started on hydroxyurea in infancy had significantly better outcomes than do children started on the drug as toddlers, researchers report.

Among 65 children with SCD, those who started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year had significantly fewer hospitalizations, pain crises, and transfusions in the first 2 years of life, compared with patients started on the drug during 1-2 years of age or after age 2 years, found Sarah B. Schuchard, PharmD, from the SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis and her colleagues.

At the Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Dr. Schuchard recently completed her training and conducted the research, the goal is to initiate all infants with sickle cell anemia and sickle-beta0-thalassemia on hydroxyurea within this first year of life.

To evaluate outcomes associated with this practice, the investigators conducted a retrospective review of all children with SCD who began hydroxyurea therapy at their center during 2008-2016.

They divided the population into three cohorts. Patients in cohort 1 were started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year (35 patients; mean age, 7.2 months), those in cohort 2 started between 1 and 2 years of age (13 patients; mean age, 19.5 months) and those in cohort 3 were started after 2 years of age (three patients; mean age, 35.5 months).

All patients had been diagnosed with either sickle cell anemia or sickle-beta0-thalassemia, and all had at least two laboratory assessments at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, or 24 months of age.

For the coprimary endpoint of laboratory data, the investigators found that patients in cohort 1, the early starters, had significantly higher hemoglobin (P = .0003), lower absolute reticulocyte counts (P = .0304), and mean corpuscular volume (P = .0199) than did the patients in cohort 3.

Infants in cohort 1 had significantly lower white blood cell counts than did the patients in either cohorts 2 or 3 (P = .0007 and P less than .0001, respectively) and lower absolute neutrophil counts (P = .0364 and .0025, respectively), although no patients required hydroxyurea therapy to be held because of low ANC.

Clinical events, the other coprimary endpoint, were also significantly better among patients in cohort 1, who had significantly fewer hospitalizations (P = .0025), a trend toward fewer painful events (P = .0618), and significantly fewer transfusions (P = .0426) than did patients in the other two cohorts.

“Early hydroxyurea also appears to contribute to fewer pain crises requiring admission,” the investigators noted.

They noted that in their study, the hematologic response was greater than that seen in the BABY HUG study, which studied the protective effects of hydroxyurea in children aged 9-18 months. The mean age of hydroxyurea initiation was 13.6 months in that study, compared with 7.2 months in the study by Dr. Schuchard and her colleagues.

“It would be interesting to see if the splenic and renal function (the unmet primary endpoints of BABY HUG) are preserved in patients starting hydroxyurea at this younger age,” they wrote.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Schuchard reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schuchard S et al. ASPHO 2018, Poster 342.

PITTSBURGH – Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) who were started on hydroxyurea in infancy had significantly better outcomes than do children started on the drug as toddlers, researchers report.

Among 65 children with SCD, those who started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year had significantly fewer hospitalizations, pain crises, and transfusions in the first 2 years of life, compared with patients started on the drug during 1-2 years of age or after age 2 years, found Sarah B. Schuchard, PharmD, from the SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis and her colleagues.

At the Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Dr. Schuchard recently completed her training and conducted the research, the goal is to initiate all infants with sickle cell anemia and sickle-beta0-thalassemia on hydroxyurea within this first year of life.

To evaluate outcomes associated with this practice, the investigators conducted a retrospective review of all children with SCD who began hydroxyurea therapy at their center during 2008-2016.

They divided the population into three cohorts. Patients in cohort 1 were started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year (35 patients; mean age, 7.2 months), those in cohort 2 started between 1 and 2 years of age (13 patients; mean age, 19.5 months) and those in cohort 3 were started after 2 years of age (three patients; mean age, 35.5 months).

All patients had been diagnosed with either sickle cell anemia or sickle-beta0-thalassemia, and all had at least two laboratory assessments at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, or 24 months of age.

For the coprimary endpoint of laboratory data, the investigators found that patients in cohort 1, the early starters, had significantly higher hemoglobin (P = .0003), lower absolute reticulocyte counts (P = .0304), and mean corpuscular volume (P = .0199) than did the patients in cohort 3.

Infants in cohort 1 had significantly lower white blood cell counts than did the patients in either cohorts 2 or 3 (P = .0007 and P less than .0001, respectively) and lower absolute neutrophil counts (P = .0364 and .0025, respectively), although no patients required hydroxyurea therapy to be held because of low ANC.

Clinical events, the other coprimary endpoint, were also significantly better among patients in cohort 1, who had significantly fewer hospitalizations (P = .0025), a trend toward fewer painful events (P = .0618), and significantly fewer transfusions (P = .0426) than did patients in the other two cohorts.

“Early hydroxyurea also appears to contribute to fewer pain crises requiring admission,” the investigators noted.

They noted that in their study, the hematologic response was greater than that seen in the BABY HUG study, which studied the protective effects of hydroxyurea in children aged 9-18 months. The mean age of hydroxyurea initiation was 13.6 months in that study, compared with 7.2 months in the study by Dr. Schuchard and her colleagues.

“It would be interesting to see if the splenic and renal function (the unmet primary endpoints of BABY HUG) are preserved in patients starting hydroxyurea at this younger age,” they wrote.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Schuchard reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schuchard S et al. ASPHO 2018, Poster 342.

PITTSBURGH – Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) who were started on hydroxyurea in infancy had significantly better outcomes than do children started on the drug as toddlers, researchers report.

Among 65 children with SCD, those who started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year had significantly fewer hospitalizations, pain crises, and transfusions in the first 2 years of life, compared with patients started on the drug during 1-2 years of age or after age 2 years, found Sarah B. Schuchard, PharmD, from the SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis and her colleagues.

At the Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Dr. Schuchard recently completed her training and conducted the research, the goal is to initiate all infants with sickle cell anemia and sickle-beta0-thalassemia on hydroxyurea within this first year of life.

To evaluate outcomes associated with this practice, the investigators conducted a retrospective review of all children with SCD who began hydroxyurea therapy at their center during 2008-2016.

They divided the population into three cohorts. Patients in cohort 1 were started on hydroxyurea before age 1 year (35 patients; mean age, 7.2 months), those in cohort 2 started between 1 and 2 years of age (13 patients; mean age, 19.5 months) and those in cohort 3 were started after 2 years of age (three patients; mean age, 35.5 months).

All patients had been diagnosed with either sickle cell anemia or sickle-beta0-thalassemia, and all had at least two laboratory assessments at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, or 24 months of age.

For the coprimary endpoint of laboratory data, the investigators found that patients in cohort 1, the early starters, had significantly higher hemoglobin (P = .0003), lower absolute reticulocyte counts (P = .0304), and mean corpuscular volume (P = .0199) than did the patients in cohort 3.

Infants in cohort 1 had significantly lower white blood cell counts than did the patients in either cohorts 2 or 3 (P = .0007 and P less than .0001, respectively) and lower absolute neutrophil counts (P = .0364 and .0025, respectively), although no patients required hydroxyurea therapy to be held because of low ANC.

Clinical events, the other coprimary endpoint, were also significantly better among patients in cohort 1, who had significantly fewer hospitalizations (P = .0025), a trend toward fewer painful events (P = .0618), and significantly fewer transfusions (P = .0426) than did patients in the other two cohorts.

“Early hydroxyurea also appears to contribute to fewer pain crises requiring admission,” the investigators noted.

They noted that in their study, the hematologic response was greater than that seen in the BABY HUG study, which studied the protective effects of hydroxyurea in children aged 9-18 months. The mean age of hydroxyurea initiation was 13.6 months in that study, compared with 7.2 months in the study by Dr. Schuchard and her colleagues.

“It would be interesting to see if the splenic and renal function (the unmet primary endpoints of BABY HUG) are preserved in patients starting hydroxyurea at this younger age,” they wrote.

The study was internally funded. Dr. Schuchard reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schuchard S et al. ASPHO 2018, Poster 342.

REPORTING FROM ASPHO 2018

Key clinical point: Early initiation of hydroxyurea is associated with better SCD outcomes.

Major finding: Patients started on hydroxyurea at a mean of 7.2 months had significantly fewer admissions, pain crises, and transfusions than did patients started after age 1 year.

Study details: Retrospective review of data on 65 children with SCD in a single center.

Disclosures: The study was internally funded. Dr. Schuchard reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Schuchard S et al. ASPHO 2018, Poster 342.

Adding vasopressin in distributive shock may cut AF risk

In patients with distributive shock, the risk of atrial fibrillation may be lower when vasopressin is administered along with catecholamine vasopressors, results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

The relative risk of atrial fibrillation was reduced for the combination of vasopressin and catecholamines versus the current standard of care, which is catecholamines alone, according to study results published in JAMA.

Beyond atrial fibrillation, however, findings of the meta-analysis were consistent with regard to other endpoints, including mortality, according to William F. McIntyre, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and his coinvestigators.

Mortality was lower with the combination approach when all studies were analyzed together. Yet, when the analysis was limited to the studies with the lowest risk of bias, the difference in mortality versus catecholamines alone was not statistically significant, investigators said.

Nevertheless, the meta-analysis does suggest that vasopressin may offer a clinical advantage regarding prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with distributive shock, a frequently fatal condition most often seen in patients with sepsis.

Vasopressin is an endogenous peptide hormone that decreases stimulation of certain myocardial receptors associated with cardiac arrhythmia, the authors noted.

“This, among other mechanisms, may translate into a reduction in adverse events, including atrial fibrillation, injury to other organs, and death,” they said in their report.

Dr. McIntyre and his colleagues included 23 trials that had enrolled a total of 3,088 patients with distributive shock, a condition in which widespread vasodilation lowers vascular resistances and mean arterial pressure. Sepsis is its most common cause. The current study is one of the first to directly compare the combination of vasopressin and catecholamine to catecholamines alone, which is the current standard of care, the investigators wrote.

They found that the administration of vasopressin was associated with a significant 23% reduction in risk of atrial fibrillation.

“The absolute effect is that 68 fewer people per 1,000 patients will experience atrial fibrillation when vasopressin is added to catecholaminergic vasopressors,” Dr. McIntyre and his coauthors said of the results.

The atrial fibrillation finding was judged to be high-quality evidence, they said, noting that two separate sensitivity analyses confirmed the benefit.

Mortality data were less consistent, they said.

Pooled data showed administration of vasopressin along with catecholamines was associated an 11% relative reduction in mortality. In absolute terms, 45 lives would be saved for every 1,000 patients receiving vasopressin, they noted.

However, the mortality findings were different when the analysis was limited to the two studies with low risk of bias. That analysis yielded a relative risk of 0.96 and was not statistically significant.

Studies show patients with distributive shock have a relative vasopressin deficiency, providing a theoretical basis for vasopressin administration as part of care, investigators said.

The current Surviving Sepsis guidelines suggest either adding vasopressin to norepinephrine to help raise mean arterial pressure to target or adding vasopressin to decrease the dosage of norepinephrine. Those are considered weak recommendations based on moderate quality of evidence, Dr. McIntyre and colleagues noted in their report.

Authors of the study reported disclosures related to Tenax Therapeutics, Orion Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among other entities.

SOURCE: McIntyre WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1889-900.

In patients with distributive shock, the risk of atrial fibrillation may be lower when vasopressin is administered along with catecholamine vasopressors, results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

The relative risk of atrial fibrillation was reduced for the combination of vasopressin and catecholamines versus the current standard of care, which is catecholamines alone, according to study results published in JAMA.

Beyond atrial fibrillation, however, findings of the meta-analysis were consistent with regard to other endpoints, including mortality, according to William F. McIntyre, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and his coinvestigators.

Mortality was lower with the combination approach when all studies were analyzed together. Yet, when the analysis was limited to the studies with the lowest risk of bias, the difference in mortality versus catecholamines alone was not statistically significant, investigators said.

Nevertheless, the meta-analysis does suggest that vasopressin may offer a clinical advantage regarding prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with distributive shock, a frequently fatal condition most often seen in patients with sepsis.

Vasopressin is an endogenous peptide hormone that decreases stimulation of certain myocardial receptors associated with cardiac arrhythmia, the authors noted.

“This, among other mechanisms, may translate into a reduction in adverse events, including atrial fibrillation, injury to other organs, and death,” they said in their report.

Dr. McIntyre and his colleagues included 23 trials that had enrolled a total of 3,088 patients with distributive shock, a condition in which widespread vasodilation lowers vascular resistances and mean arterial pressure. Sepsis is its most common cause. The current study is one of the first to directly compare the combination of vasopressin and catecholamine to catecholamines alone, which is the current standard of care, the investigators wrote.

They found that the administration of vasopressin was associated with a significant 23% reduction in risk of atrial fibrillation.

“The absolute effect is that 68 fewer people per 1,000 patients will experience atrial fibrillation when vasopressin is added to catecholaminergic vasopressors,” Dr. McIntyre and his coauthors said of the results.

The atrial fibrillation finding was judged to be high-quality evidence, they said, noting that two separate sensitivity analyses confirmed the benefit.

Mortality data were less consistent, they said.

Pooled data showed administration of vasopressin along with catecholamines was associated an 11% relative reduction in mortality. In absolute terms, 45 lives would be saved for every 1,000 patients receiving vasopressin, they noted.

However, the mortality findings were different when the analysis was limited to the two studies with low risk of bias. That analysis yielded a relative risk of 0.96 and was not statistically significant.

Studies show patients with distributive shock have a relative vasopressin deficiency, providing a theoretical basis for vasopressin administration as part of care, investigators said.

The current Surviving Sepsis guidelines suggest either adding vasopressin to norepinephrine to help raise mean arterial pressure to target or adding vasopressin to decrease the dosage of norepinephrine. Those are considered weak recommendations based on moderate quality of evidence, Dr. McIntyre and colleagues noted in their report.

Authors of the study reported disclosures related to Tenax Therapeutics, Orion Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among other entities.

SOURCE: McIntyre WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1889-900.

In patients with distributive shock, the risk of atrial fibrillation may be lower when vasopressin is administered along with catecholamine vasopressors, results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggest.

The relative risk of atrial fibrillation was reduced for the combination of vasopressin and catecholamines versus the current standard of care, which is catecholamines alone, according to study results published in JAMA.

Beyond atrial fibrillation, however, findings of the meta-analysis were consistent with regard to other endpoints, including mortality, according to William F. McIntyre, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and his coinvestigators.

Mortality was lower with the combination approach when all studies were analyzed together. Yet, when the analysis was limited to the studies with the lowest risk of bias, the difference in mortality versus catecholamines alone was not statistically significant, investigators said.

Nevertheless, the meta-analysis does suggest that vasopressin may offer a clinical advantage regarding prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with distributive shock, a frequently fatal condition most often seen in patients with sepsis.

Vasopressin is an endogenous peptide hormone that decreases stimulation of certain myocardial receptors associated with cardiac arrhythmia, the authors noted.

“This, among other mechanisms, may translate into a reduction in adverse events, including atrial fibrillation, injury to other organs, and death,” they said in their report.

Dr. McIntyre and his colleagues included 23 trials that had enrolled a total of 3,088 patients with distributive shock, a condition in which widespread vasodilation lowers vascular resistances and mean arterial pressure. Sepsis is its most common cause. The current study is one of the first to directly compare the combination of vasopressin and catecholamine to catecholamines alone, which is the current standard of care, the investigators wrote.

They found that the administration of vasopressin was associated with a significant 23% reduction in risk of atrial fibrillation.

“The absolute effect is that 68 fewer people per 1,000 patients will experience atrial fibrillation when vasopressin is added to catecholaminergic vasopressors,” Dr. McIntyre and his coauthors said of the results.

The atrial fibrillation finding was judged to be high-quality evidence, they said, noting that two separate sensitivity analyses confirmed the benefit.

Mortality data were less consistent, they said.

Pooled data showed administration of vasopressin along with catecholamines was associated an 11% relative reduction in mortality. In absolute terms, 45 lives would be saved for every 1,000 patients receiving vasopressin, they noted.

However, the mortality findings were different when the analysis was limited to the two studies with low risk of bias. That analysis yielded a relative risk of 0.96 and was not statistically significant.

Studies show patients with distributive shock have a relative vasopressin deficiency, providing a theoretical basis for vasopressin administration as part of care, investigators said.

The current Surviving Sepsis guidelines suggest either adding vasopressin to norepinephrine to help raise mean arterial pressure to target or adding vasopressin to decrease the dosage of norepinephrine. Those are considered weak recommendations based on moderate quality of evidence, Dr. McIntyre and colleagues noted in their report.

Authors of the study reported disclosures related to Tenax Therapeutics, Orion Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among other entities.

SOURCE: McIntyre WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1889-900.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: For patients with distributive shock, the addition of vasopressin to catecholamine vasopressors may reduce atrial fibrillation risk, compared with catecholamines alone.

Major finding: Vasopressin was associated with a 23% lower risk of atrial fibrillation.

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis including 23 randomized clinical trials enrolling a total of 3,088 patients.

Disclosures: Authors reported disclosures related to Tenax Therapeutics, Orion Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among other entities.

Source: McIntyre WF et al. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1889-900.

NHLBI seeks to accelerate hemostasis/thrombosis research

SAN DIEGO – The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is looking to jump-start research into hemostasis and thrombosis. Donna DiMichele, MD, offered two reasons for the research push.

“The first is to stimulate research in areas that are undersubscribed through investigator-initiated research,” Dr. DiMichele, deputy director of the NHLBI’s Division of Blood Diseases and Resources, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “We also do it sometimes to steer research in directions that are not developing organically through investigator-initiated efforts. In hemostasis and thrombosis, 50% of the investigator-led research is basic in nature. Nonetheless, there were several basic research initiatives that NHLBI released in the last few years that stimulated the field in a new direction.”

The centers will be required to look beyond current active science disciplines in this field, to include emerging sciences and technologies not currently being exploited in this research area. The initiative is also intended to cross-train the next generation of physicians/scientists with interdisciplinary skill sets. “The research teams with successful applications are going to begin their work by the summer of 2018, and hopefully we’ll soon gain some new insights into Factor VIII immunogenicity,” Dr. DiMichele said.

One novel scientific area that successful applicants will be able to take advantage of is the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Program (TOPMed). Launched in 2014, this program facilitates whole-genome sequencing across cohorts in heart, lung, blood, and sleep science. TOPMed now includes more than 120,000 whole genomes, with more than 5,000 of those in hemophilia.

In basic science, two NHLBI-funded initiatives aim to improve the understanding of thrombosis.

One, Sex Hormone Induced Thromboembolism in Premenopausal Women (R61/R33), is meant to elucidate the mechanisms by which female sex hormones and sex hormone-based therapies can increase the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism in premenopausal women. The other initiative, Consortium Linking Oncology with Thrombosis (U01), is aimed at encouraging studies in individual cancer types that expand investigation into the intersection between cancer and thrombotic pathways. It also aims to help researchers identify and develop biomarkers of thrombotic risk or cancer progression, and new strategies for preventing or treating the deleterious interplay between cancer, cancer therapy, and hemostasis/thrombosis.

In the translational research arena, the NHLBI released an initiative on Perinatal Stroke (R01) in 2017. It solicits applications that propose basic and/or translational research studies related to the developing neurovascular unit, perinatal injury/repair response, and/or stroke-related etiologies and risk factors. The purpose is to stimulate research that will identify therapeutic targets in perinatal stroke.

Other NHLBI-sponsored efforts include the Trans-Agency Research Consortium for Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC), as well as the Translational Research Centers in Thrombotic and Hemostatic Disorders program, which set out to enhance the translation of basic research discoveries that could lead to improved prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for thrombotic and hemostatic disorders. This program ended but it led to the development of several projects that are moving into the commercialization phase.

Finally, to further stimulate research in FVIII immunogenicity, on May 15-16, 2018, the NHBLI will host a free workshop entitled “Factor VIII Inhibitors: Generating a Blueprint for Future Research.” For information, visit https://factorviiinhibitors.eventbrite.com.

Dr. DiMichele reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is looking to jump-start research into hemostasis and thrombosis. Donna DiMichele, MD, offered two reasons for the research push.

“The first is to stimulate research in areas that are undersubscribed through investigator-initiated research,” Dr. DiMichele, deputy director of the NHLBI’s Division of Blood Diseases and Resources, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “We also do it sometimes to steer research in directions that are not developing organically through investigator-initiated efforts. In hemostasis and thrombosis, 50% of the investigator-led research is basic in nature. Nonetheless, there were several basic research initiatives that NHLBI released in the last few years that stimulated the field in a new direction.”

The centers will be required to look beyond current active science disciplines in this field, to include emerging sciences and technologies not currently being exploited in this research area. The initiative is also intended to cross-train the next generation of physicians/scientists with interdisciplinary skill sets. “The research teams with successful applications are going to begin their work by the summer of 2018, and hopefully we’ll soon gain some new insights into Factor VIII immunogenicity,” Dr. DiMichele said.

One novel scientific area that successful applicants will be able to take advantage of is the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Program (TOPMed). Launched in 2014, this program facilitates whole-genome sequencing across cohorts in heart, lung, blood, and sleep science. TOPMed now includes more than 120,000 whole genomes, with more than 5,000 of those in hemophilia.

In basic science, two NHLBI-funded initiatives aim to improve the understanding of thrombosis.

One, Sex Hormone Induced Thromboembolism in Premenopausal Women (R61/R33), is meant to elucidate the mechanisms by which female sex hormones and sex hormone-based therapies can increase the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism in premenopausal women. The other initiative, Consortium Linking Oncology with Thrombosis (U01), is aimed at encouraging studies in individual cancer types that expand investigation into the intersection between cancer and thrombotic pathways. It also aims to help researchers identify and develop biomarkers of thrombotic risk or cancer progression, and new strategies for preventing or treating the deleterious interplay between cancer, cancer therapy, and hemostasis/thrombosis.

In the translational research arena, the NHLBI released an initiative on Perinatal Stroke (R01) in 2017. It solicits applications that propose basic and/or translational research studies related to the developing neurovascular unit, perinatal injury/repair response, and/or stroke-related etiologies and risk factors. The purpose is to stimulate research that will identify therapeutic targets in perinatal stroke.

Other NHLBI-sponsored efforts include the Trans-Agency Research Consortium for Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC), as well as the Translational Research Centers in Thrombotic and Hemostatic Disorders program, which set out to enhance the translation of basic research discoveries that could lead to improved prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for thrombotic and hemostatic disorders. This program ended but it led to the development of several projects that are moving into the commercialization phase.

Finally, to further stimulate research in FVIII immunogenicity, on May 15-16, 2018, the NHBLI will host a free workshop entitled “Factor VIII Inhibitors: Generating a Blueprint for Future Research.” For information, visit https://factorviiinhibitors.eventbrite.com.

Dr. DiMichele reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is looking to jump-start research into hemostasis and thrombosis. Donna DiMichele, MD, offered two reasons for the research push.

“The first is to stimulate research in areas that are undersubscribed through investigator-initiated research,” Dr. DiMichele, deputy director of the NHLBI’s Division of Blood Diseases and Resources, said at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “We also do it sometimes to steer research in directions that are not developing organically through investigator-initiated efforts. In hemostasis and thrombosis, 50% of the investigator-led research is basic in nature. Nonetheless, there were several basic research initiatives that NHLBI released in the last few years that stimulated the field in a new direction.”

The centers will be required to look beyond current active science disciplines in this field, to include emerging sciences and technologies not currently being exploited in this research area. The initiative is also intended to cross-train the next generation of physicians/scientists with interdisciplinary skill sets. “The research teams with successful applications are going to begin their work by the summer of 2018, and hopefully we’ll soon gain some new insights into Factor VIII immunogenicity,” Dr. DiMichele said.

One novel scientific area that successful applicants will be able to take advantage of is the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Program (TOPMed). Launched in 2014, this program facilitates whole-genome sequencing across cohorts in heart, lung, blood, and sleep science. TOPMed now includes more than 120,000 whole genomes, with more than 5,000 of those in hemophilia.

In basic science, two NHLBI-funded initiatives aim to improve the understanding of thrombosis.

One, Sex Hormone Induced Thromboembolism in Premenopausal Women (R61/R33), is meant to elucidate the mechanisms by which female sex hormones and sex hormone-based therapies can increase the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism in premenopausal women. The other initiative, Consortium Linking Oncology with Thrombosis (U01), is aimed at encouraging studies in individual cancer types that expand investigation into the intersection between cancer and thrombotic pathways. It also aims to help researchers identify and develop biomarkers of thrombotic risk or cancer progression, and new strategies for preventing or treating the deleterious interplay between cancer, cancer therapy, and hemostasis/thrombosis.

In the translational research arena, the NHLBI released an initiative on Perinatal Stroke (R01) in 2017. It solicits applications that propose basic and/or translational research studies related to the developing neurovascular unit, perinatal injury/repair response, and/or stroke-related etiologies and risk factors. The purpose is to stimulate research that will identify therapeutic targets in perinatal stroke.

Other NHLBI-sponsored efforts include the Trans-Agency Research Consortium for Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC), as well as the Translational Research Centers in Thrombotic and Hemostatic Disorders program, which set out to enhance the translation of basic research discoveries that could lead to improved prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for thrombotic and hemostatic disorders. This program ended but it led to the development of several projects that are moving into the commercialization phase.

Finally, to further stimulate research in FVIII immunogenicity, on May 15-16, 2018, the NHBLI will host a free workshop entitled “Factor VIII Inhibitors: Generating a Blueprint for Future Research.” For information, visit https://factorviiinhibitors.eventbrite.com.

Dr. DiMichele reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THSNA 2018

Single injection could treat hemophilia B long-term

Cell therapy could produce lasting effects in hemophilia B, according to a group of researchers.

They genetically modified induced pluripotent cells (iPSCs) derived from patients with hemophilia B and converted those iPSCs into hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs).

When transplanted into mouse models of hemophilia B, the HLCs remained functional for months, increasing levels of factor IX (FIX) and clotting efficiency.

However, the HLCs were substantially less effective than cryopreserved human hepatocytes (hHeps), which were able to correct clotting defects in mice long-term.

“The appeal of a cell-based approach is that you minimize the number of treatments that a patient needs,” explained Suvasini Ramaswamy, PhD, of The Boston Consulting Group in Massachusetts.

“Rather than constant injections, you can do this in one shot.”

Dr Ramaswamy and her colleagues described their results with this approach in Cell Reports. Study authors include employees of Shire Therapeutics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Thermo Fisher Scientific.

The researchers first developed a quadruple knockout mouse model of hemophilia B that allows for the engraftment and expansion of hHeps. The team crossed transgenic FIX-/--deficient mice with Rag2-/- IL2rg -/- Fah-/- mice to create this model.

The researchers transplanted cryopreserved hHeps into the mice and observed a sustained increase in circulating levels of human albumin, human FIX, and clusters of FIX- or Fah-positive cells in the liver.

The team said the hHeps were able to restore clotting function to wild-type levels in the mice—at least 10-fold higher than levels needed for a significant improvement in hemophilia B.

The hHeps remained functional for up to a year, and the researchers believe the cells could persist even longer. The team noted that there was no difference in the efficacy of hHeps from different donors or vendors.

The researchers then tested the cell therapy they developed using iPSCs. They collected blood samples from 2 patients with severe hemophilia B, reprogrammed peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells into iPSCs, and used CRISPR/Cas9 to repair the mutations in each patient’s FIX gene.

The team coaxed those repaired cells into HLCs and tested the HLCs in the mouse model of hemophilia B. The HLCs were transplanted through the spleen so the cells were distributed uniformly in the liver.

The researchers said the HLCs were present and functional in the liver for up to a year, but they were less effective than hHeps. Mice that received HLCs experienced “modest” increases in clotting efficiency, from less than 10% to about 25% of wild-type activity.

The researchers believe this work demonstrates the value of combining stem cell reprogramming and gene-modifying approaches to treat genetic diseases. However, more work is needed to optimize this approach for hemophilia B.

Cell therapy could produce lasting effects in hemophilia B, according to a group of researchers.

They genetically modified induced pluripotent cells (iPSCs) derived from patients with hemophilia B and converted those iPSCs into hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs).

When transplanted into mouse models of hemophilia B, the HLCs remained functional for months, increasing levels of factor IX (FIX) and clotting efficiency.

However, the HLCs were substantially less effective than cryopreserved human hepatocytes (hHeps), which were able to correct clotting defects in mice long-term.

“The appeal of a cell-based approach is that you minimize the number of treatments that a patient needs,” explained Suvasini Ramaswamy, PhD, of The Boston Consulting Group in Massachusetts.

“Rather than constant injections, you can do this in one shot.”

Dr Ramaswamy and her colleagues described their results with this approach in Cell Reports. Study authors include employees of Shire Therapeutics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Thermo Fisher Scientific.

The researchers first developed a quadruple knockout mouse model of hemophilia B that allows for the engraftment and expansion of hHeps. The team crossed transgenic FIX-/--deficient mice with Rag2-/- IL2rg -/- Fah-/- mice to create this model.

The researchers transplanted cryopreserved hHeps into the mice and observed a sustained increase in circulating levels of human albumin, human FIX, and clusters of FIX- or Fah-positive cells in the liver.

The team said the hHeps were able to restore clotting function to wild-type levels in the mice—at least 10-fold higher than levels needed for a significant improvement in hemophilia B.

The hHeps remained functional for up to a year, and the researchers believe the cells could persist even longer. The team noted that there was no difference in the efficacy of hHeps from different donors or vendors.

The researchers then tested the cell therapy they developed using iPSCs. They collected blood samples from 2 patients with severe hemophilia B, reprogrammed peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells into iPSCs, and used CRISPR/Cas9 to repair the mutations in each patient’s FIX gene.

The team coaxed those repaired cells into HLCs and tested the HLCs in the mouse model of hemophilia B. The HLCs were transplanted through the spleen so the cells were distributed uniformly in the liver.

The researchers said the HLCs were present and functional in the liver for up to a year, but they were less effective than hHeps. Mice that received HLCs experienced “modest” increases in clotting efficiency, from less than 10% to about 25% of wild-type activity.

The researchers believe this work demonstrates the value of combining stem cell reprogramming and gene-modifying approaches to treat genetic diseases. However, more work is needed to optimize this approach for hemophilia B.

Cell therapy could produce lasting effects in hemophilia B, according to a group of researchers.

They genetically modified induced pluripotent cells (iPSCs) derived from patients with hemophilia B and converted those iPSCs into hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs).

When transplanted into mouse models of hemophilia B, the HLCs remained functional for months, increasing levels of factor IX (FIX) and clotting efficiency.

However, the HLCs were substantially less effective than cryopreserved human hepatocytes (hHeps), which were able to correct clotting defects in mice long-term.

“The appeal of a cell-based approach is that you minimize the number of treatments that a patient needs,” explained Suvasini Ramaswamy, PhD, of The Boston Consulting Group in Massachusetts.

“Rather than constant injections, you can do this in one shot.”

Dr Ramaswamy and her colleagues described their results with this approach in Cell Reports. Study authors include employees of Shire Therapeutics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Thermo Fisher Scientific.

The researchers first developed a quadruple knockout mouse model of hemophilia B that allows for the engraftment and expansion of hHeps. The team crossed transgenic FIX-/--deficient mice with Rag2-/- IL2rg -/- Fah-/- mice to create this model.

The researchers transplanted cryopreserved hHeps into the mice and observed a sustained increase in circulating levels of human albumin, human FIX, and clusters of FIX- or Fah-positive cells in the liver.

The team said the hHeps were able to restore clotting function to wild-type levels in the mice—at least 10-fold higher than levels needed for a significant improvement in hemophilia B.

The hHeps remained functional for up to a year, and the researchers believe the cells could persist even longer. The team noted that there was no difference in the efficacy of hHeps from different donors or vendors.

The researchers then tested the cell therapy they developed using iPSCs. They collected blood samples from 2 patients with severe hemophilia B, reprogrammed peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells into iPSCs, and used CRISPR/Cas9 to repair the mutations in each patient’s FIX gene.

The team coaxed those repaired cells into HLCs and tested the HLCs in the mouse model of hemophilia B. The HLCs were transplanted through the spleen so the cells were distributed uniformly in the liver.

The researchers said the HLCs were present and functional in the liver for up to a year, but they were less effective than hHeps. Mice that received HLCs experienced “modest” increases in clotting efficiency, from less than 10% to about 25% of wild-type activity.

The researchers believe this work demonstrates the value of combining stem cell reprogramming and gene-modifying approaches to treat genetic diseases. However, more work is needed to optimize this approach for hemophilia B.

PI3K inhibitors could treat HHT

Preclinical research suggests PI3K inhibitors could treat hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that loss of ALK1 function induces vascular hyperplasia and increases activity of the PI3K pathway.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K was able to eliminate vascular hyperplasia in mouse models.

Francesc Viñals, PhD, of Institut Catala d’Oncologia in Barcelona, Spain, and his colleagues described this research in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology.

“Our group has been working with endothelial cells for a long time, focusing on how they are affected by changes in the TGF-beta signaling pathway from a basic research perspective,” Dr Viñals noted.

The group was especially interested in ALK1, a receptor for the TGF-beta factor BMP9 that is expressed by endothelial cells. Mutations in ALK1 have been associated with HHT.