User login

Tularemia outbreak in four U.S. states

One hundred cases of tularemia have been reported in 2015 among residents of Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, according to a report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents a substantial increase in the annual mean number of cases (2 to 7) reported in each of these states during the past decade.

Although the cause for the increase in cases is unclear, Dr. Caitlin Pedati of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service and colleagues wrote in the Dec. 4 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that possible factors include increased rainfall promoting vegetation growth, pathogen survival, increased rodent and rabbit populations, and increased disease awareness (MMWR. 2015 Dec 4;64[47]:1317-8).

The infected patients ranged in age from 10 months to 89 years, and most commonly presented with the pneumonic form of respiratory disease, skin lesions with lymphadenopathy, and a general febrile illness without localizing signs. A total of 48 people were hospitalized and one died. Possible exposure routes included animal contact, environmental aerosolizing activities, and arthropod bites.

Clinical disease signs of tularemia could include fever and chills with muscle and joint pain, cough or difficulty breathing, swollen lymph nodes with or without skin lesions, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, or abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea, the authors noted. Case fatality rates range from <2% to 24%, depending on the strain. Streptomycin is considered the drug of choice for treatment.

“Health care providers should be aware of the elevated risk for tularemia within these states and consider a diagnosis of tularemia in any person nationwide with compatible signs and symptoms,” wrote Dr. Pedati and colleagues.

Read the full article in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

One hundred cases of tularemia have been reported in 2015 among residents of Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, according to a report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents a substantial increase in the annual mean number of cases (2 to 7) reported in each of these states during the past decade.

Although the cause for the increase in cases is unclear, Dr. Caitlin Pedati of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service and colleagues wrote in the Dec. 4 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that possible factors include increased rainfall promoting vegetation growth, pathogen survival, increased rodent and rabbit populations, and increased disease awareness (MMWR. 2015 Dec 4;64[47]:1317-8).

The infected patients ranged in age from 10 months to 89 years, and most commonly presented with the pneumonic form of respiratory disease, skin lesions with lymphadenopathy, and a general febrile illness without localizing signs. A total of 48 people were hospitalized and one died. Possible exposure routes included animal contact, environmental aerosolizing activities, and arthropod bites.

Clinical disease signs of tularemia could include fever and chills with muscle and joint pain, cough or difficulty breathing, swollen lymph nodes with or without skin lesions, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, or abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea, the authors noted. Case fatality rates range from <2% to 24%, depending on the strain. Streptomycin is considered the drug of choice for treatment.

“Health care providers should be aware of the elevated risk for tularemia within these states and consider a diagnosis of tularemia in any person nationwide with compatible signs and symptoms,” wrote Dr. Pedati and colleagues.

Read the full article in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

One hundred cases of tularemia have been reported in 2015 among residents of Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, according to a report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This represents a substantial increase in the annual mean number of cases (2 to 7) reported in each of these states during the past decade.

Although the cause for the increase in cases is unclear, Dr. Caitlin Pedati of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service and colleagues wrote in the Dec. 4 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that possible factors include increased rainfall promoting vegetation growth, pathogen survival, increased rodent and rabbit populations, and increased disease awareness (MMWR. 2015 Dec 4;64[47]:1317-8).

The infected patients ranged in age from 10 months to 89 years, and most commonly presented with the pneumonic form of respiratory disease, skin lesions with lymphadenopathy, and a general febrile illness without localizing signs. A total of 48 people were hospitalized and one died. Possible exposure routes included animal contact, environmental aerosolizing activities, and arthropod bites.

Clinical disease signs of tularemia could include fever and chills with muscle and joint pain, cough or difficulty breathing, swollen lymph nodes with or without skin lesions, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, or abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea, the authors noted. Case fatality rates range from <2% to 24%, depending on the strain. Streptomycin is considered the drug of choice for treatment.

“Health care providers should be aware of the elevated risk for tularemia within these states and consider a diagnosis of tularemia in any person nationwide with compatible signs and symptoms,” wrote Dr. Pedati and colleagues.

Read the full article in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Dengue disease is here and U.S. physicians need to get to know it

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – With dengue disease now knocking on the door of the United States, it’s a good time for American physicians to get up to speed regarding the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world.

That’s a particularly sound idea if they – or their patients – plan to visit anywhere in the Caribbean, Central America, Brazil, East Asia, or large swathes of Africa, where the disease is a major and rapidly growing public health problem. The World Health Organization estimates 3.6 billion people worldwide are at risk for dengue disease, with up to 100 million symptomatic infections occurring annually, 250,000-500,000 cases of severe dengue, and 21,000 deaths due to the disease. There have been recent outbreaks in South Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, Dr. Federico Narvaez noted at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The most important thing for clinicians to know about dengue disease is how to identify the subset of up to 10% of symptomatic dengue patients who – absent appropriate intervention – will progress to severe disease marked by pronounced plasma leakage leading to shock, respiratory failure, severe hemorrhage, and/or organ failure, he stressed. This is a disease that can cause death within the space of 24-48 hours in a person who was healthy just a few days before. And there are a handful of warning signs that predictably occur on day 3 or 4 of the illness, when the initial high fever comes down, before things take a dramatic turn for the worse.

“Timely diagnosis improves prognosis. If properly managed, the case fatality rate of severe dengue is less than 1%,” said Dr. Narvaez of the National Pediatric Reference Hospital and the Nicaragua Ministry of Health in Managua.

The traditional WHO classification for dengue into self-limited dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, and dengue shock syndrome was replaced in 2009 by a system that Dr. Narvaez and other experts consider a big step forward in guiding clinical management. Under the revised WHO classification, dengue disease is divided into dengue without warning signs, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

In a study of 544 laboratory-confirmed cases of pediatric dengue in Managua, Dr. Narvaez and coinvestigators compared the former and revised WHO classifications and demonstrated that the 2009 revised system boosted the positive predictive value for need for inpatient care from 43% to 67% (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Nov;5[11]:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. Epub 2011 Nov 8).

Some key points about dengue disease: It has two distinct mosquito vectors, Aedis aegypti and A. albonictus. There are four cocirculating serotypes; infection with one doesn’t protect against infection with the others. Three-quarters of infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections follow a three-stage course: the febrile, critical, and recovery phases. And the primary pathophysiology of dengue disease is plasma leakage.

The febrile phase is marked by abrupt onset of high fever plus various combinations of severe headache, facial flushing, a transient macular or maculopapular rash, retro-orbital pain, and/or the intense arthralgias/myalgias which have led to dengue being known as ‘breakbone fever.’

The critical phase begins around the time of defervescence. This is when clinically significant plasma leakage can occur, with resultant compensated or decompensated shock and other severe complications. The critical phase is the time for vigilance regarding the appearance of the 2009 WHO warning signs of increased risk for shock: abdominal pain, an abrupt rise in hematocrit concurrent with a rapid drop in platelets, mucosal bleeding, development of ascites or other clinically apparent fluid accumulation, liver enlargement of more than 2 cm, persistent vomiting, and restlessness/lethargy.

In a soon-to-be-published study of 812 Nicaraguan dengue patients, 220 of whom developed shock, Dr. Narvaez and coworkers found that the presence of any of the warning signs except persistent vomiting was associated with significantly increased likelihood of subsequent shock, with the magnitude of increased risk ranging from 1.31 to 2.3. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that by acting upon these warning signs by means of cautious administration of intravenous fluids and other supportive measures, the risk of developing shock is reduced.

The WHO warning signs are particularly valuable in the often resource-poor countries where dengue is most common. In such settings most front-line primary care physicians lack ready access to ultrasound imaging of the gallbladder looking for evidence of wall thickening. A thickened gallbladder wall is an expression of subclinical plasma leakage, which has been shown in multiple studies to be even better at identifying patients at risk for severe dengue than the WHO warning signs.

For example, a prospective hospital-based study in which Dutch and Indonesian investigators utilized serial daily bedside ultrasonography with a hand-held imaging device found that gallbladder wall edema at enrollment had a 35% positive predictive value and a 90% negative predictive value for subsequent severe dengue (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Jun 13;7[6]:e2277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002277).

The critical phase typically lasts from day 3 or 4 through day 6 of the illness. This is followed by the recovery phase, marked by reabsorption of extravasated fluid over the course of 48-72 hours, increased diuresis, and stabilization of hemodynamic status. The appearance of a highly pruritic and erythematous rash with small islands of normal skin is another common finding that indicates the patient’s condition will continue to improve. A temporary bradycardia is also quite common during the recovery phase, according to Dr. Narvaez.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICAAC 2015

Promising nonvaccine approaches to controlling dengue

SAN DIEGO – In the aftermath of the latest somewhat disappointing report on the effort to develop a dengue vaccine, novel nonvaccine approaches aimed at curbing this rapidly growing public health problem are drawing renewed attention, Eva Harris, Ph.D., declared at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

These promising nonvaccine tools fall into several categories: vector control using genetically modified mosquitoes, development of new and better insecticides, and communitywide nonpesticide-based source reduction programs, explained Dr. Harris, professor of infectious diseases and vaccinology and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

Many dengue experts, Dr. Harris among them, were disappointed in the recently reported long-term results of several large clinical trials of the candidate dengue vaccine furthest along in the developmental pipeline. The Sanofi Pasteur vaccine, known as CYD-TDV, is due for review and potential registration by the World Health Organization next year. The latest results show favorable safety but suboptimal efficacy. On the plus side, the data showed that children aged 9-16 years continued to benefit 3-4 years after vaccination. There was, however, a disturbing finding: children younger than 9 years of age at vaccination had an increased risk of hospitalization for dengue when they were naturally infected in the third year following vaccination (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1195-206).

In an accompanying editorial titled “A Candidate Dengue Vaccine Walks a Tightrope,” Dr. Cameron P. Simmons called the latter finding “a particularly unwelcome outcome” that, if not due to chance, raises the possibility that immunization of young children elicits only transient antibody-mediated immunity. As their antibody titers wane over time, these vaccinated children may, through sensitization, be predisposed to clinical dengue infections that are sufficiently serious to warrant hospitalization. It’s possible, but unproved, that booster doses of the vaccine might circumvent this problem, he added.

“The bumpy road to a vaccine-based solution for dengue continues,” observed Dr. Simmons of the University of Melbourne (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1263-4).

Dr. Harris noted that two other vaccines, one sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the other by Takeda, are due to start large, long-term phase-III clinical trials in the next few months. And Merck and GlaxoSmithKline have next-generation vaccines in phase-I studies. But possible consideration of any of these vaccines for regulatory approval is a long ways off, and her focus at ICAAC 2015 was on nonvaccine solutions.

She and her coinvestigators recently published positive results of their landmark randomized controlled trial of a pesticide-free, community-based mobilization program for dengue prevention known as the Camino Verde, or Green Way (BMJ. 2015;351:h3267).

The impetus for this program was recognition of the shortcomings of current dengue control efforts, which rely heavily upon massive use of the organophosphate pesticide temephos (Abate) in household water containers where the mosquito vectors breed. The pesticide program hasn’t prevented ongoing rapid growth of the dengue pandemic. Moreover, the associated human toxicity and negative environmental effects are a mounting concern.

Camino Verde is a nonchemical alternative approach in which facilitators run intervention design groups in neighborhoods to inform community leaders and other residents about the scope of their local dengue mosquito problem based upon entomologic survey results and then help develop consensus regarding community-specific programs for chemical-free prevention of mosquito reproduction. Popular options included introduction of fish into water storage containers, cleanup campaigns targeting abandoned tires and other standing-water sources, and scrubbing and covering water tanks. Allowing each participating site to select its own interventions encouraged strong community support, Dr. Harris explained.

The prospective Camino Verde study involved nearly 19,000 households with more than 85,000 residents in Nicaragua and Mexico. Clusters of households were randomized to continuation of the temephos-based, government-run dengue control program with or without adding on the Camino Verde intervention.

Among the key findings: There was a 30% lower risk of serologic infection with dengue virus among children from intervention sites, as well as a 25% reduction in dengue illness among people of all ages. The numbers needed to treat were 30 for a reduced risk of infection in children and 71 for a lower risk of illness. Investigators also documented a 44% reduction in houses containing Aedes aegypti larvae or pupae in Camino Verde–participating sites, compared with control communities.

This study provides the first-ever solid serologic evidence that a pesticide-free community mobilization effort has a positive impact on dengue infection. The logical next step is for governments in dengue-endemic countries to adopt such an approach, she said.

At least three different strategies of genetic modification of dengue-vector mosquitoes are being pursued in an effort to reduce dengue transmission. All show promise as partial solutions, in Dr. Harris’ view.

Release of sterile transgenic A. aegypti males over the course of a year in a Brazilian suburb resulted in a 95% reduction in the size of the local A. aegypti population, compared with an adjacent control area (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9[7]:e0003864). Investigators at Colorado State University in Fort Collins have developed a transgenic strain of A. aegypti males carrying a dominant lethal gene resulting in next-generation flightless females that can’t mate or avoid predators (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108[12]:4772-5).

In another approach, an international collaborative group has performed field-release trials of A. aegypti mosquitoes deliberately infected with a strain of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which renders the insects resistant to dengue virus infection. The group’s mathematical modeling suggested widespread adoption of this approach would reduce dengue virus transmission by 66%-75%. The investigators predicted this would be sufficient to eliminate dengue in low- or moderate-transmission areas but probably wouldn’t accomplish complete control in the highest-risk areas (Sci Transl Med. 2015;7[279]:279ra37).

Dr. Harris reported that the Camino Verde trial was funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – In the aftermath of the latest somewhat disappointing report on the effort to develop a dengue vaccine, novel nonvaccine approaches aimed at curbing this rapidly growing public health problem are drawing renewed attention, Eva Harris, Ph.D., declared at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

These promising nonvaccine tools fall into several categories: vector control using genetically modified mosquitoes, development of new and better insecticides, and communitywide nonpesticide-based source reduction programs, explained Dr. Harris, professor of infectious diseases and vaccinology and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

Many dengue experts, Dr. Harris among them, were disappointed in the recently reported long-term results of several large clinical trials of the candidate dengue vaccine furthest along in the developmental pipeline. The Sanofi Pasteur vaccine, known as CYD-TDV, is due for review and potential registration by the World Health Organization next year. The latest results show favorable safety but suboptimal efficacy. On the plus side, the data showed that children aged 9-16 years continued to benefit 3-4 years after vaccination. There was, however, a disturbing finding: children younger than 9 years of age at vaccination had an increased risk of hospitalization for dengue when they were naturally infected in the third year following vaccination (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1195-206).

In an accompanying editorial titled “A Candidate Dengue Vaccine Walks a Tightrope,” Dr. Cameron P. Simmons called the latter finding “a particularly unwelcome outcome” that, if not due to chance, raises the possibility that immunization of young children elicits only transient antibody-mediated immunity. As their antibody titers wane over time, these vaccinated children may, through sensitization, be predisposed to clinical dengue infections that are sufficiently serious to warrant hospitalization. It’s possible, but unproved, that booster doses of the vaccine might circumvent this problem, he added.

“The bumpy road to a vaccine-based solution for dengue continues,” observed Dr. Simmons of the University of Melbourne (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1263-4).

Dr. Harris noted that two other vaccines, one sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the other by Takeda, are due to start large, long-term phase-III clinical trials in the next few months. And Merck and GlaxoSmithKline have next-generation vaccines in phase-I studies. But possible consideration of any of these vaccines for regulatory approval is a long ways off, and her focus at ICAAC 2015 was on nonvaccine solutions.

She and her coinvestigators recently published positive results of their landmark randomized controlled trial of a pesticide-free, community-based mobilization program for dengue prevention known as the Camino Verde, or Green Way (BMJ. 2015;351:h3267).

The impetus for this program was recognition of the shortcomings of current dengue control efforts, which rely heavily upon massive use of the organophosphate pesticide temephos (Abate) in household water containers where the mosquito vectors breed. The pesticide program hasn’t prevented ongoing rapid growth of the dengue pandemic. Moreover, the associated human toxicity and negative environmental effects are a mounting concern.

Camino Verde is a nonchemical alternative approach in which facilitators run intervention design groups in neighborhoods to inform community leaders and other residents about the scope of their local dengue mosquito problem based upon entomologic survey results and then help develop consensus regarding community-specific programs for chemical-free prevention of mosquito reproduction. Popular options included introduction of fish into water storage containers, cleanup campaigns targeting abandoned tires and other standing-water sources, and scrubbing and covering water tanks. Allowing each participating site to select its own interventions encouraged strong community support, Dr. Harris explained.

The prospective Camino Verde study involved nearly 19,000 households with more than 85,000 residents in Nicaragua and Mexico. Clusters of households were randomized to continuation of the temephos-based, government-run dengue control program with or without adding on the Camino Verde intervention.

Among the key findings: There was a 30% lower risk of serologic infection with dengue virus among children from intervention sites, as well as a 25% reduction in dengue illness among people of all ages. The numbers needed to treat were 30 for a reduced risk of infection in children and 71 for a lower risk of illness. Investigators also documented a 44% reduction in houses containing Aedes aegypti larvae or pupae in Camino Verde–participating sites, compared with control communities.

This study provides the first-ever solid serologic evidence that a pesticide-free community mobilization effort has a positive impact on dengue infection. The logical next step is for governments in dengue-endemic countries to adopt such an approach, she said.

At least three different strategies of genetic modification of dengue-vector mosquitoes are being pursued in an effort to reduce dengue transmission. All show promise as partial solutions, in Dr. Harris’ view.

Release of sterile transgenic A. aegypti males over the course of a year in a Brazilian suburb resulted in a 95% reduction in the size of the local A. aegypti population, compared with an adjacent control area (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9[7]:e0003864). Investigators at Colorado State University in Fort Collins have developed a transgenic strain of A. aegypti males carrying a dominant lethal gene resulting in next-generation flightless females that can’t mate or avoid predators (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108[12]:4772-5).

In another approach, an international collaborative group has performed field-release trials of A. aegypti mosquitoes deliberately infected with a strain of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which renders the insects resistant to dengue virus infection. The group’s mathematical modeling suggested widespread adoption of this approach would reduce dengue virus transmission by 66%-75%. The investigators predicted this would be sufficient to eliminate dengue in low- or moderate-transmission areas but probably wouldn’t accomplish complete control in the highest-risk areas (Sci Transl Med. 2015;7[279]:279ra37).

Dr. Harris reported that the Camino Verde trial was funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – In the aftermath of the latest somewhat disappointing report on the effort to develop a dengue vaccine, novel nonvaccine approaches aimed at curbing this rapidly growing public health problem are drawing renewed attention, Eva Harris, Ph.D., declared at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

These promising nonvaccine tools fall into several categories: vector control using genetically modified mosquitoes, development of new and better insecticides, and communitywide nonpesticide-based source reduction programs, explained Dr. Harris, professor of infectious diseases and vaccinology and director of the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

Many dengue experts, Dr. Harris among them, were disappointed in the recently reported long-term results of several large clinical trials of the candidate dengue vaccine furthest along in the developmental pipeline. The Sanofi Pasteur vaccine, known as CYD-TDV, is due for review and potential registration by the World Health Organization next year. The latest results show favorable safety but suboptimal efficacy. On the plus side, the data showed that children aged 9-16 years continued to benefit 3-4 years after vaccination. There was, however, a disturbing finding: children younger than 9 years of age at vaccination had an increased risk of hospitalization for dengue when they were naturally infected in the third year following vaccination (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1195-206).

In an accompanying editorial titled “A Candidate Dengue Vaccine Walks a Tightrope,” Dr. Cameron P. Simmons called the latter finding “a particularly unwelcome outcome” that, if not due to chance, raises the possibility that immunization of young children elicits only transient antibody-mediated immunity. As their antibody titers wane over time, these vaccinated children may, through sensitization, be predisposed to clinical dengue infections that are sufficiently serious to warrant hospitalization. It’s possible, but unproved, that booster doses of the vaccine might circumvent this problem, he added.

“The bumpy road to a vaccine-based solution for dengue continues,” observed Dr. Simmons of the University of Melbourne (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1263-4).

Dr. Harris noted that two other vaccines, one sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the other by Takeda, are due to start large, long-term phase-III clinical trials in the next few months. And Merck and GlaxoSmithKline have next-generation vaccines in phase-I studies. But possible consideration of any of these vaccines for regulatory approval is a long ways off, and her focus at ICAAC 2015 was on nonvaccine solutions.

She and her coinvestigators recently published positive results of their landmark randomized controlled trial of a pesticide-free, community-based mobilization program for dengue prevention known as the Camino Verde, or Green Way (BMJ. 2015;351:h3267).

The impetus for this program was recognition of the shortcomings of current dengue control efforts, which rely heavily upon massive use of the organophosphate pesticide temephos (Abate) in household water containers where the mosquito vectors breed. The pesticide program hasn’t prevented ongoing rapid growth of the dengue pandemic. Moreover, the associated human toxicity and negative environmental effects are a mounting concern.

Camino Verde is a nonchemical alternative approach in which facilitators run intervention design groups in neighborhoods to inform community leaders and other residents about the scope of their local dengue mosquito problem based upon entomologic survey results and then help develop consensus regarding community-specific programs for chemical-free prevention of mosquito reproduction. Popular options included introduction of fish into water storage containers, cleanup campaigns targeting abandoned tires and other standing-water sources, and scrubbing and covering water tanks. Allowing each participating site to select its own interventions encouraged strong community support, Dr. Harris explained.

The prospective Camino Verde study involved nearly 19,000 households with more than 85,000 residents in Nicaragua and Mexico. Clusters of households were randomized to continuation of the temephos-based, government-run dengue control program with or without adding on the Camino Verde intervention.

Among the key findings: There was a 30% lower risk of serologic infection with dengue virus among children from intervention sites, as well as a 25% reduction in dengue illness among people of all ages. The numbers needed to treat were 30 for a reduced risk of infection in children and 71 for a lower risk of illness. Investigators also documented a 44% reduction in houses containing Aedes aegypti larvae or pupae in Camino Verde–participating sites, compared with control communities.

This study provides the first-ever solid serologic evidence that a pesticide-free community mobilization effort has a positive impact on dengue infection. The logical next step is for governments in dengue-endemic countries to adopt such an approach, she said.

At least three different strategies of genetic modification of dengue-vector mosquitoes are being pursued in an effort to reduce dengue transmission. All show promise as partial solutions, in Dr. Harris’ view.

Release of sterile transgenic A. aegypti males over the course of a year in a Brazilian suburb resulted in a 95% reduction in the size of the local A. aegypti population, compared with an adjacent control area (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9[7]:e0003864). Investigators at Colorado State University in Fort Collins have developed a transgenic strain of A. aegypti males carrying a dominant lethal gene resulting in next-generation flightless females that can’t mate or avoid predators (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108[12]:4772-5).

In another approach, an international collaborative group has performed field-release trials of A. aegypti mosquitoes deliberately infected with a strain of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which renders the insects resistant to dengue virus infection. The group’s mathematical modeling suggested widespread adoption of this approach would reduce dengue virus transmission by 66%-75%. The investigators predicted this would be sufficient to eliminate dengue in low- or moderate-transmission areas but probably wouldn’t accomplish complete control in the highest-risk areas (Sci Transl Med. 2015;7[279]:279ra37).

Dr. Harris reported that the Camino Verde trial was funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICAAC 2015

Zika virus adds to dengue and chikungunya threat in Brazil

Clusters of acute exanthematous illness in Brazil have been linked since 2014 to the Zika virus, but research also suggests the concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors, a new report reveals.

Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus that causes a denguelike illness characterized by exanthema, low-grade fever, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia. In a letter to the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases published online, Dr. Cristiane W. Cardoso of the Municipality of Health in Salvador, Brazil, and her coauthors describe the challenges Brazilian public health authorities faced in clinically differentiating Zika virus infections from dengue and chikungunya viruses, also circulating in Brazil from February 2015 to June 2015 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.151167).

All three viruses are etiologic agents of acute exanthematous illness, which suggests that the three Aedes mosquito−transmitted viruses were co-circulating in the state of Salvador. The research highlights the challenge in clinically differentiating the infections during outbreaks. The researchers were not able to determine the specific incidence of each virus but write that the low frequency of fever and arthralgia, which are indicators of dengue and chikungunya, point to Zika virus as the probable cause of several reported cases in 2015.

Dr. Cardoso says the spread of Zika virus represents a challenge for public health systems because of the risk for concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes – which are abundant throughout tropical and subtropical regions. The authors also suggest that an increase in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome during the outbreak deserves further investigation to determine whether the syndrome is associated with Zika infection.

To read the entire letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

Clusters of acute exanthematous illness in Brazil have been linked since 2014 to the Zika virus, but research also suggests the concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors, a new report reveals.

Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus that causes a denguelike illness characterized by exanthema, low-grade fever, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia. In a letter to the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases published online, Dr. Cristiane W. Cardoso of the Municipality of Health in Salvador, Brazil, and her coauthors describe the challenges Brazilian public health authorities faced in clinically differentiating Zika virus infections from dengue and chikungunya viruses, also circulating in Brazil from February 2015 to June 2015 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.151167).

All three viruses are etiologic agents of acute exanthematous illness, which suggests that the three Aedes mosquito−transmitted viruses were co-circulating in the state of Salvador. The research highlights the challenge in clinically differentiating the infections during outbreaks. The researchers were not able to determine the specific incidence of each virus but write that the low frequency of fever and arthralgia, which are indicators of dengue and chikungunya, point to Zika virus as the probable cause of several reported cases in 2015.

Dr. Cardoso says the spread of Zika virus represents a challenge for public health systems because of the risk for concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes – which are abundant throughout tropical and subtropical regions. The authors also suggest that an increase in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome during the outbreak deserves further investigation to determine whether the syndrome is associated with Zika infection.

To read the entire letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

Clusters of acute exanthematous illness in Brazil have been linked since 2014 to the Zika virus, but research also suggests the concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors, a new report reveals.

Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus that causes a denguelike illness characterized by exanthema, low-grade fever, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia. In a letter to the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases published online, Dr. Cristiane W. Cardoso of the Municipality of Health in Salvador, Brazil, and her coauthors describe the challenges Brazilian public health authorities faced in clinically differentiating Zika virus infections from dengue and chikungunya viruses, also circulating in Brazil from February 2015 to June 2015 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.151167).

All three viruses are etiologic agents of acute exanthematous illness, which suggests that the three Aedes mosquito−transmitted viruses were co-circulating in the state of Salvador. The research highlights the challenge in clinically differentiating the infections during outbreaks. The researchers were not able to determine the specific incidence of each virus but write that the low frequency of fever and arthralgia, which are indicators of dengue and chikungunya, point to Zika virus as the probable cause of several reported cases in 2015.

Dr. Cardoso says the spread of Zika virus represents a challenge for public health systems because of the risk for concurrent transmission of dengue and chikungunya by the same vectors – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes – which are abundant throughout tropical and subtropical regions. The authors also suggest that an increase in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome during the outbreak deserves further investigation to determine whether the syndrome is associated with Zika infection.

To read the entire letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Louse-borne relapsing fever appears again in Europe

The reemergence of an early-20th-century fever is an example of how increased migration from war-torn and resource-poor countries has created new routes for the spread of vectorborne diseases.

Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) caused by the bacterium Borrelia recurrentis was a major public health problem in Eastern Europe and Northern Africa during World Wars I and II. A new study published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases reveals that several cases of LBRF have been reported in multiple European nations among asylum seekers from Eritrea (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jan. 22[1]. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151580).

Poor living conditions, famine, war, and refugee camps are major risk factors for epidemics of LBRF, writes Dr. Alessandra Ciervo of the department of infectious, parasitic and immune-mediated diseases at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome. Indeed, recent cases of LBRF in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany occurred in asylum seekers who had been in refugee camps in Libya or Italy. Dr. Ciervo and her coauthors report on three sample LBRF cases among patients in Italy who migrated from Somalia after traveling in several countries in Africa and crossing the Mediterranean.

The researchers conclude that, because the cases suggest that more migrants and refugees are infected, LBRF should be considered an emerging disease among migrants and refugees, and diagnostic suspicion of LBRF should lead to early diagnosis among refugees from the Horn of Africa and in persons in migrant camps.

To read the entire research letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The reemergence of an early-20th-century fever is an example of how increased migration from war-torn and resource-poor countries has created new routes for the spread of vectorborne diseases.

Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) caused by the bacterium Borrelia recurrentis was a major public health problem in Eastern Europe and Northern Africa during World Wars I and II. A new study published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases reveals that several cases of LBRF have been reported in multiple European nations among asylum seekers from Eritrea (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jan. 22[1]. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151580).

Poor living conditions, famine, war, and refugee camps are major risk factors for epidemics of LBRF, writes Dr. Alessandra Ciervo of the department of infectious, parasitic and immune-mediated diseases at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome. Indeed, recent cases of LBRF in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany occurred in asylum seekers who had been in refugee camps in Libya or Italy. Dr. Ciervo and her coauthors report on three sample LBRF cases among patients in Italy who migrated from Somalia after traveling in several countries in Africa and crossing the Mediterranean.

The researchers conclude that, because the cases suggest that more migrants and refugees are infected, LBRF should be considered an emerging disease among migrants and refugees, and diagnostic suspicion of LBRF should lead to early diagnosis among refugees from the Horn of Africa and in persons in migrant camps.

To read the entire research letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The reemergence of an early-20th-century fever is an example of how increased migration from war-torn and resource-poor countries has created new routes for the spread of vectorborne diseases.

Louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) caused by the bacterium Borrelia recurrentis was a major public health problem in Eastern Europe and Northern Africa during World Wars I and II. A new study published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases reveals that several cases of LBRF have been reported in multiple European nations among asylum seekers from Eritrea (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jan. 22[1]. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151580).

Poor living conditions, famine, war, and refugee camps are major risk factors for epidemics of LBRF, writes Dr. Alessandra Ciervo of the department of infectious, parasitic and immune-mediated diseases at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità in Rome. Indeed, recent cases of LBRF in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany occurred in asylum seekers who had been in refugee camps in Libya or Italy. Dr. Ciervo and her coauthors report on three sample LBRF cases among patients in Italy who migrated from Somalia after traveling in several countries in Africa and crossing the Mediterranean.

The researchers conclude that, because the cases suggest that more migrants and refugees are infected, LBRF should be considered an emerging disease among migrants and refugees, and diagnostic suspicion of LBRF should lead to early diagnosis among refugees from the Horn of Africa and in persons in migrant camps.

To read the entire research letter, click here.

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

IOM report outlines viral outbreak preparedness

Developing medical countermeasures (MCMs) before an emerging infectious disease hits is a ‘national security imperative,’ according to an Institute of Medicine Workshop Summary, and global health security strategies that effectively utilize public-private partnerships should be a top priority for health professionals and governments.

The IOM and several of its partner organizations coconvened a workshop panel on “Rapid Medical Countermeasure Response to Infectious Diseases: Enabling Sustainable Capabilities through Ongoing Public- and Private-Sector Partnerships,” in Washington on March 26-27, 2015. Meeting minutes are available online at the IOM website. The organization recently released a summary report on the panel’s discussions.

Although the panelist’s discussions do not officially reflect the conclusions of the IOM, participants at the workshop discussed the nation’s capacity to provide rapid access to MCMs when infectious disease outbreaks occur. Other topics discussed included preparedness gaps, the sustainability of public-private partnerships, case studies of past incidents of emerging threats such as influenza and coronaviruses, and lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak of 2014.

“Between events such as H1N1 influenza outbreaks, mission capabilities need to be sustained so capacity is not lost when the next event emerges. Additionally, many regulations and policies have been developed in response to past events, instead of looking forward to potential future needs and creating capabilities and partnerships in a systematic matter,” the report summary noted.

To read the full summary report, click here.

Developing medical countermeasures (MCMs) before an emerging infectious disease hits is a ‘national security imperative,’ according to an Institute of Medicine Workshop Summary, and global health security strategies that effectively utilize public-private partnerships should be a top priority for health professionals and governments.

The IOM and several of its partner organizations coconvened a workshop panel on “Rapid Medical Countermeasure Response to Infectious Diseases: Enabling Sustainable Capabilities through Ongoing Public- and Private-Sector Partnerships,” in Washington on March 26-27, 2015. Meeting minutes are available online at the IOM website. The organization recently released a summary report on the panel’s discussions.

Although the panelist’s discussions do not officially reflect the conclusions of the IOM, participants at the workshop discussed the nation’s capacity to provide rapid access to MCMs when infectious disease outbreaks occur. Other topics discussed included preparedness gaps, the sustainability of public-private partnerships, case studies of past incidents of emerging threats such as influenza and coronaviruses, and lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak of 2014.

“Between events such as H1N1 influenza outbreaks, mission capabilities need to be sustained so capacity is not lost when the next event emerges. Additionally, many regulations and policies have been developed in response to past events, instead of looking forward to potential future needs and creating capabilities and partnerships in a systematic matter,” the report summary noted.

To read the full summary report, click here.

Developing medical countermeasures (MCMs) before an emerging infectious disease hits is a ‘national security imperative,’ according to an Institute of Medicine Workshop Summary, and global health security strategies that effectively utilize public-private partnerships should be a top priority for health professionals and governments.

The IOM and several of its partner organizations coconvened a workshop panel on “Rapid Medical Countermeasure Response to Infectious Diseases: Enabling Sustainable Capabilities through Ongoing Public- and Private-Sector Partnerships,” in Washington on March 26-27, 2015. Meeting minutes are available online at the IOM website. The organization recently released a summary report on the panel’s discussions.

Although the panelist’s discussions do not officially reflect the conclusions of the IOM, participants at the workshop discussed the nation’s capacity to provide rapid access to MCMs when infectious disease outbreaks occur. Other topics discussed included preparedness gaps, the sustainability of public-private partnerships, case studies of past incidents of emerging threats such as influenza and coronaviruses, and lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak of 2014.

“Between events such as H1N1 influenza outbreaks, mission capabilities need to be sustained so capacity is not lost when the next event emerges. Additionally, many regulations and policies have been developed in response to past events, instead of looking forward to potential future needs and creating capabilities and partnerships in a systematic matter,” the report summary noted.

To read the full summary report, click here.

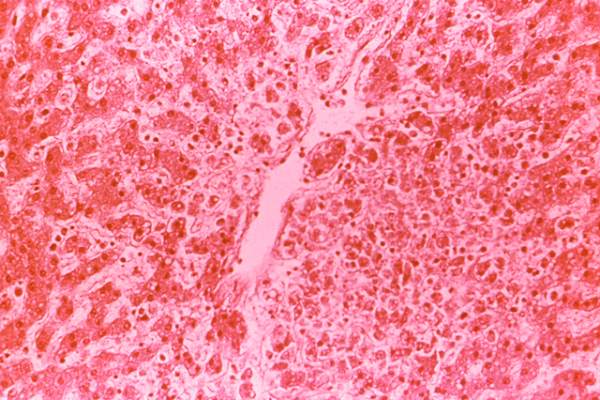

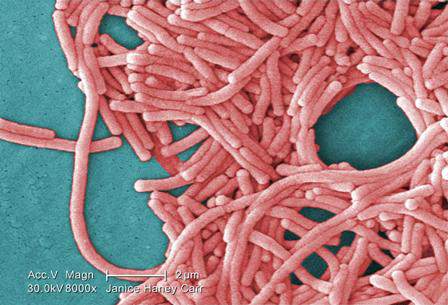

Legionellosis cases continue to increase nationwide

Data from the first 3 years of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program on legionellosis confirm that incidences of disease caused by the bacteria are increasing across the United States, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2015 Oct 30;64[42]:1190-1193).

The ABCs program, which launched in 2011, identified 1,426 cases of legionellosis over the 3-year time span, and incidence rates of 1.3 (2011), 1.1 (2012), and 1.4 (2013) cases per 100,000 individuals in the general population. This corroborates similar findings made by the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) between 2000 and 2011, which reported an increase in the crude incidence rate of legionellosis nationwide from 0.39 to 1.36 cases per 100,000 individuals.

The two main clinical syndromes associated with legionellosis are Legionnaires’ disease, which is a severe form of pneumonia; and Pontiac fever, a milder illness without pneumonia.

“During 2000-2011, passive surveillance for legionellosis in the United States demonstrated a 249% increase in crude incidence, although little was known about the clinical course and method of diagnosis,” says the report, led by Dr. Kathleen I. Dooling of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The report also states that “ABCs data during 2011-2013 showed that approximately 44% of patients with legionellosis required intensive care, and 9% died.” Furthermore, incidence increased with age among the ABCs program cohort. Those younger than 50 years of age had a 0.4 incidence rate per 100,000 individuals; patients between 50 and 64 years old had a 2.5 per 100,000 incidence rate; those who were 65-79 years old had a 3.6 per 100,000 incidence rate; and individuals 80 years and older had an incidence rate of 4.7 per 100,000 individuals.

“Among cases identified during 2011-2013, 79% occurred in persons aged >50 years, 65% were in males, and 72% of patients were white,” says the report, adding that “1,300 (91%) received a diagnosis of legionellosis on the basis of urine antigen testing, which only detects Lp1 species.”

The ABCs program defined a confirmed case of legionellosis as “the isolation of Legionella from respiratory culture, detection of Legionella antigen in urine, or seroconversion (a more than fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent sera) to Lp1.” Unlike NNDSS, ABCs recorded clinical and race data for each patient found to have legionellosis, finding that incidence rates among blacks were higher than among whites per 100,000 individuals: 1.0 vs. 1.5, respectively.

The report concludes by calling for further research into the disparities in legionellosis cases based on race, age, and geography, as well as the need for “more sensitive laboratory tests for legionellosis because proper diagnosis is needed for treatment and public health action.”

This study was supported by the CDC.

Data from the first 3 years of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program on legionellosis confirm that incidences of disease caused by the bacteria are increasing across the United States, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2015 Oct 30;64[42]:1190-1193).

The ABCs program, which launched in 2011, identified 1,426 cases of legionellosis over the 3-year time span, and incidence rates of 1.3 (2011), 1.1 (2012), and 1.4 (2013) cases per 100,000 individuals in the general population. This corroborates similar findings made by the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) between 2000 and 2011, which reported an increase in the crude incidence rate of legionellosis nationwide from 0.39 to 1.36 cases per 100,000 individuals.

The two main clinical syndromes associated with legionellosis are Legionnaires’ disease, which is a severe form of pneumonia; and Pontiac fever, a milder illness without pneumonia.

“During 2000-2011, passive surveillance for legionellosis in the United States demonstrated a 249% increase in crude incidence, although little was known about the clinical course and method of diagnosis,” says the report, led by Dr. Kathleen I. Dooling of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The report also states that “ABCs data during 2011-2013 showed that approximately 44% of patients with legionellosis required intensive care, and 9% died.” Furthermore, incidence increased with age among the ABCs program cohort. Those younger than 50 years of age had a 0.4 incidence rate per 100,000 individuals; patients between 50 and 64 years old had a 2.5 per 100,000 incidence rate; those who were 65-79 years old had a 3.6 per 100,000 incidence rate; and individuals 80 years and older had an incidence rate of 4.7 per 100,000 individuals.

“Among cases identified during 2011-2013, 79% occurred in persons aged >50 years, 65% were in males, and 72% of patients were white,” says the report, adding that “1,300 (91%) received a diagnosis of legionellosis on the basis of urine antigen testing, which only detects Lp1 species.”

The ABCs program defined a confirmed case of legionellosis as “the isolation of Legionella from respiratory culture, detection of Legionella antigen in urine, or seroconversion (a more than fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent sera) to Lp1.” Unlike NNDSS, ABCs recorded clinical and race data for each patient found to have legionellosis, finding that incidence rates among blacks were higher than among whites per 100,000 individuals: 1.0 vs. 1.5, respectively.

The report concludes by calling for further research into the disparities in legionellosis cases based on race, age, and geography, as well as the need for “more sensitive laboratory tests for legionellosis because proper diagnosis is needed for treatment and public health action.”

This study was supported by the CDC.

Data from the first 3 years of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program on legionellosis confirm that incidences of disease caused by the bacteria are increasing across the United States, according to the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2015 Oct 30;64[42]:1190-1193).

The ABCs program, which launched in 2011, identified 1,426 cases of legionellosis over the 3-year time span, and incidence rates of 1.3 (2011), 1.1 (2012), and 1.4 (2013) cases per 100,000 individuals in the general population. This corroborates similar findings made by the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) between 2000 and 2011, which reported an increase in the crude incidence rate of legionellosis nationwide from 0.39 to 1.36 cases per 100,000 individuals.

The two main clinical syndromes associated with legionellosis are Legionnaires’ disease, which is a severe form of pneumonia; and Pontiac fever, a milder illness without pneumonia.

“During 2000-2011, passive surveillance for legionellosis in the United States demonstrated a 249% increase in crude incidence, although little was known about the clinical course and method of diagnosis,” says the report, led by Dr. Kathleen I. Dooling of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

The report also states that “ABCs data during 2011-2013 showed that approximately 44% of patients with legionellosis required intensive care, and 9% died.” Furthermore, incidence increased with age among the ABCs program cohort. Those younger than 50 years of age had a 0.4 incidence rate per 100,000 individuals; patients between 50 and 64 years old had a 2.5 per 100,000 incidence rate; those who were 65-79 years old had a 3.6 per 100,000 incidence rate; and individuals 80 years and older had an incidence rate of 4.7 per 100,000 individuals.

“Among cases identified during 2011-2013, 79% occurred in persons aged >50 years, 65% were in males, and 72% of patients were white,” says the report, adding that “1,300 (91%) received a diagnosis of legionellosis on the basis of urine antigen testing, which only detects Lp1 species.”

The ABCs program defined a confirmed case of legionellosis as “the isolation of Legionella from respiratory culture, detection of Legionella antigen in urine, or seroconversion (a more than fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent sera) to Lp1.” Unlike NNDSS, ABCs recorded clinical and race data for each patient found to have legionellosis, finding that incidence rates among blacks were higher than among whites per 100,000 individuals: 1.0 vs. 1.5, respectively.

The report concludes by calling for further research into the disparities in legionellosis cases based on race, age, and geography, as well as the need for “more sensitive laboratory tests for legionellosis because proper diagnosis is needed for treatment and public health action.”

This study was supported by the CDC.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point: Data from the first 3 years of the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance program provides evidence confirming that legionellosis rates across the United States are steadily rising.

Major finding: ABCs identified 1,426 legionellosis cases during 2011-2013, for an incidence of 1.3 cases per 100,000 population over the 3 years.

Data source: Analysis of 1,426 legionellosis cases from 2011-2013 collected by the CDC’s ABCs program.

Disclosures: Study supported by the CDC.

Ebola virus may persist in semen 9 months after symptom onset

Male survivors of Ebola virus disease (EVD) may still have the virus present in their semen as long as 9 months after the onset of symptoms, according to a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study – led by Dr. Gibrilla Deen of Connaught Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone – enrolled 100 male survivors of EVD in Sierra Leone, of whom 93 provided a semen specimen at some time after the onset of symptoms, which was analyzed for Ebola virus RNA. Specimens were analyzed via a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay.

Results indicated that 46 of the 93 men (49%) who provided the initial semen sample tested positive for Ebola virus RNA. All 9 (100%) of the men whose specimens were analyzed 2-3 months after the onset of symptoms tested positive. Of the 40 whose specimens were received 4-6 months after symptom onset, 26 (65%) tested positive. Eleven of the 43 (26%) whose specimens were obtained 7-9 months after symptom onset were positive, as well.

“Ebola survivors face an increasing number of recognized health complications,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a statement, adding that “this study provides important new information about the persistence of Ebola virus in semen and helps us make recommendations to survivors and their loved ones to help them stay healthy.”

All participants were aged 18-58 years, with a mean of 30 years. While 63% of subjects had at least 6 years of formal education, 22% had less than that, and 15% had no formal education of any kind. Only 10% of subjects reported a monthly income of moe than $1,000, while 43% reported not knowing their income at all. None of the participants reported a history of HIV, tuberculosis, or diabetes diagnoses.

“Because semen-testing programs are not yet universally available, outreach activities are needed to provide education regarding recommendations and risks to survivor communities and sexual partners of survivors in a way that does not further stigmatize [the] survivors of EVD,” according to the study.

The authors of the study acknowledge that their findings are potentially limited by the size of their sample, as well as the lack of data on the risk of trasmission via sexual intercourse or other sex acts from men with Ebola virus RNA in their semen. Follow-up analysis of the current findings is underway.

Dr. Deen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Male survivors of Ebola virus disease (EVD) may still have the virus present in their semen as long as 9 months after the onset of symptoms, according to a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study – led by Dr. Gibrilla Deen of Connaught Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone – enrolled 100 male survivors of EVD in Sierra Leone, of whom 93 provided a semen specimen at some time after the onset of symptoms, which was analyzed for Ebola virus RNA. Specimens were analyzed via a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay.

Results indicated that 46 of the 93 men (49%) who provided the initial semen sample tested positive for Ebola virus RNA. All 9 (100%) of the men whose specimens were analyzed 2-3 months after the onset of symptoms tested positive. Of the 40 whose specimens were received 4-6 months after symptom onset, 26 (65%) tested positive. Eleven of the 43 (26%) whose specimens were obtained 7-9 months after symptom onset were positive, as well.

“Ebola survivors face an increasing number of recognized health complications,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a statement, adding that “this study provides important new information about the persistence of Ebola virus in semen and helps us make recommendations to survivors and their loved ones to help them stay healthy.”

All participants were aged 18-58 years, with a mean of 30 years. While 63% of subjects had at least 6 years of formal education, 22% had less than that, and 15% had no formal education of any kind. Only 10% of subjects reported a monthly income of moe than $1,000, while 43% reported not knowing their income at all. None of the participants reported a history of HIV, tuberculosis, or diabetes diagnoses.

“Because semen-testing programs are not yet universally available, outreach activities are needed to provide education regarding recommendations and risks to survivor communities and sexual partners of survivors in a way that does not further stigmatize [the] survivors of EVD,” according to the study.

The authors of the study acknowledge that their findings are potentially limited by the size of their sample, as well as the lack of data on the risk of trasmission via sexual intercourse or other sex acts from men with Ebola virus RNA in their semen. Follow-up analysis of the current findings is underway.

Dr. Deen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Male survivors of Ebola virus disease (EVD) may still have the virus present in their semen as long as 9 months after the onset of symptoms, according to a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study – led by Dr. Gibrilla Deen of Connaught Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone – enrolled 100 male survivors of EVD in Sierra Leone, of whom 93 provided a semen specimen at some time after the onset of symptoms, which was analyzed for Ebola virus RNA. Specimens were analyzed via a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay.

Results indicated that 46 of the 93 men (49%) who provided the initial semen sample tested positive for Ebola virus RNA. All 9 (100%) of the men whose specimens were analyzed 2-3 months after the onset of symptoms tested positive. Of the 40 whose specimens were received 4-6 months after symptom onset, 26 (65%) tested positive. Eleven of the 43 (26%) whose specimens were obtained 7-9 months after symptom onset were positive, as well.

“Ebola survivors face an increasing number of recognized health complications,” said Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a statement, adding that “this study provides important new information about the persistence of Ebola virus in semen and helps us make recommendations to survivors and their loved ones to help them stay healthy.”

All participants were aged 18-58 years, with a mean of 30 years. While 63% of subjects had at least 6 years of formal education, 22% had less than that, and 15% had no formal education of any kind. Only 10% of subjects reported a monthly income of moe than $1,000, while 43% reported not knowing their income at all. None of the participants reported a history of HIV, tuberculosis, or diabetes diagnoses.

“Because semen-testing programs are not yet universally available, outreach activities are needed to provide education regarding recommendations and risks to survivor communities and sexual partners of survivors in a way that does not further stigmatize [the] survivors of EVD,” according to the study.

The authors of the study acknowledge that their findings are potentially limited by the size of their sample, as well as the lack of data on the risk of trasmission via sexual intercourse or other sex acts from men with Ebola virus RNA in their semen. Follow-up analysis of the current findings is underway.

Dr. Deen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM NEJM

Key clinical point: Men who have survived Ebola virus disease can have the virus present in their semen for 9 months after onset of symptoms.

Major finding: Forty-six of the 93 men (49%) who provided semen specimens tested positive for Ebola virus RNA. The subjects tested positive at intervals of 2-8 months post onset of symptoms.

Data source: Cohort study of 100 male EVD survivors.

Disclosures: Dr. Deen did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Carbapenem resistance on the rise in children

The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in children is low but has increased significantly since 1999, particularly among isolates from intensive care units and from blood and lower respiratory tract cultures, new data suggest.

Analysis of 316,253 Enterobacteriaceae isolates reported to 300 U.S. laboratories participating in the Surveillance Network-USA database between 1999 and 2012 showed 0.08% of isolates were carbapenem resistant, with the most common resistant isolates being Enterobacter species isolated from urinary sources and from the inpatient non-ICU setting.

“Unlike for adults, where increases were greater than for children, we did not find that the increase in CRE in children appeared to be related to residence in long-term care facilities, because only 0.1% of CRE isolates came from this setting,” wrote Dr. Latania K. Logan, director of pediatric infectious diseases at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and her coauthors.

The study, published Oct. 14 in Emerging Infectious Diseases, showed a significant overall increase from 0% to 0.47% in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae over the 12-year study period; among ICU isolates, the prevalence increased from 0% to 4.5% over the same period.

Many of the carbapenem-resistant isolates also were resistant to other antimicrobial drugs, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin, and nearly half (48.3%) were resistant to more than three antimicrobial drug classes (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150548).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Children’s Foundation, the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. No conflicts of interest were declared.