User login

New Paradigms in Lymphoma Treatment

Emerging concepts, a growing knowledge base, and new targets are changing the way mantle cell lymphoma is treated and managed, according to Mark Roschewski, MD, of the Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

"With more understanding of the biology about what makes this lymphoma different than others, we see changes," Roschewski said. "We have seen a lot of changes in this particular disease even in the last year. I think this bodes well for the future of how we are going to manage patients."

Emerging concepts, a growing knowledge base, and new targets are changing the way mantle cell lymphoma is treated and managed, according to Mark Roschewski, MD, of the Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

"With more understanding of the biology about what makes this lymphoma different than others, we see changes," Roschewski said. "We have seen a lot of changes in this particular disease even in the last year. I think this bodes well for the future of how we are going to manage patients."

Emerging concepts, a growing knowledge base, and new targets are changing the way mantle cell lymphoma is treated and managed, according to Mark Roschewski, MD, of the Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

"With more understanding of the biology about what makes this lymphoma different than others, we see changes," Roschewski said. "We have seen a lot of changes in this particular disease even in the last year. I think this bodes well for the future of how we are going to manage patients."

Bone Metastasis: Concise Overview

Bone metastasis is a relatively common complication of cancer, often developing as they advance, especially in prostate cancer and breast cancer. Bone metastasis can profoundly affect patients’ daily activities and quality of life (QOL) due to severe pain and associated major complications. Prompt palliative therapy is required for symptomatic pain relief and prevention of the devastating complications of bone metastasis.

Epidemiology

Bone is the most common and preferred site for metastatic involvement of cancer. Advanced cancers frequently develop metastases to the bone during the later phases of cancer progression. At least 100,000 patients develop bone metastases every year, although the exact number of bone metastases is not known.1 Multiple myeloma (MM), breast cancer, and prostate cancer are responsible for up to 70% of bone metastases cases.2 Gastrointestinal cancers contribute least to bone metastases: < 15% of all cases.2

Related: Effective Treatment Options for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

The prognosis of bone metastases is generally poor, although it partly depends on the primary site of the original cancer and on the presence of any additional metastases to visceral organs. For example, it is known that survival times are longer for patients with primary prostate or breast cancer than for patients with lung cancer primary tumors.3,4

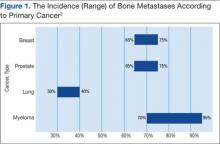

Prostate and breast cancers are the most common primary cancers of bone metastases. At postmortem studies, patients who died of prostate cancer or breast cancer revealed evidence of bone metastases in up to 75% of cases (Figure 1). Regardless of their survival expectancy, however, most patients with bone metastasis need immediate medical attention and active palliative therapy to prevent devastating complications related to bone metastasis, such as pathologic bone fractures and severe bone pain.

Clinical Features

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is the second most common hematologic malignancy and is caused by an abnormal accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow. Characteristic clinical manifestations include bony destruction and related features of bone pain, anemia (80% of cases), hypocalcemia, and renal dysfunction. Pathologic fractures, renal failure, or hyperviscosity syndrome often develops. More than 20,000 new patients are diagnosed with MM and about 11,000 patients in the U.S. die of MM every year. Multiple myeloma and is twice as likely to develop in men as it is in women. A large number of MM cases are under the care of VAMCs (about 10%-12% of all MM cases).7,8

Abnormal laboratory tests show an elevated total protein level in the blood and/or urine (Bence Jones proteinuria). Serum electrophoresis detects M-protein in about 80% to 90% of patients. Patients may also present with renal failure. The differential diagnosis includes other malignancies, such as metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, leukemia, and monoclonal gammopathy.

Pathophysiology

Normal bone tissue is made up of 2 different types of cells: osteoblasts and osteoclasts. New bone is constantly being produced while old bone is broken down. When tumor cells invade bone, the cancer cells produce 1 of 2 distinct substances; as a result, either osteoclasts or osteoblasts are stimulated, depending on tumor type metastasized to the bone. The activated osteoclasts then dissolve the bone, weakening the bone (osteolytic phenomenon), and the osteoblasts stimulate bone formation, hardening the bone (osteoblastic or sclerotic process).

Diagnosis and Evaluation

The most important first step in evaluating bone metastasis in a patient is to take a thorough, careful medical history and perform a physical examination. The examination not only helps locate suspected sites of bone metastases, but also helps determine necessary diagnostic studies.

The radiographic appearance of bone metastasis can be classified into 4 groups: osteolytic, osteoblastic, osteoporotic, and mixed. Imaging characteristics of osteolytic lesions include the destruction/thinning of bone, whereas osteoblastic (osteosclerotic) lesions appear with excess deposition of new bones. In contrast to malignant osteolytic lesions, osteoporotic lesions look like faded bone without cortical destruction or increased density.

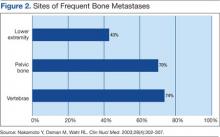

The main choice of imaging study for screening suspected bone metastases is usually the bone scan (Figure 3). Plain radiographs are not useful in the early detection of bone metastases, because bone lesions do not show up on plain films until 30% to 50% of the bone mineral is lost.5,9 Although most metastatic bone lesions represent a mixture of osteoblastic and -lytic processes, metastatic lesions of lung cancer and breast cancer are predominantly osteolytic in contrast to mainly osteoblastic lesions of prostate cancer metastases.10

The osteoblastic process of bone metastases is best demonstrated on a bone scan; however, a positive bone scan does not necessarily indicate bone metastases, because it is not highly specific of metastatic disease. Several benign bone lesions (such as osteoarthritis, traumatic injury, and Paget disease) also show positive readings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not useful in screening for bone metastases, but it is better in assessing bone metastases compared with a bone scan, because it is more sensitive, especially for spinal lesions. The reported sensitivity of MRI is 91% to 100%, whereas bone scan sensitivity is only 62% to 85%.11,12

Even though the bone scan has been assumed to be the best imaging study for bone metastases, positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be more useful in detecting osteolytic bone metastases, as they can light up areas of increased metabolic activity. Positron emission tomography scans, however, are less sensitive for osteoblastic metastases. An additional advantage of PET scans is that they can be used for whole-body scanning/surveillance to rule out visceral involvement.

Published studies indicate that bone scans better detect sclerotic bone metastases and PET scans are superior in revealing osteolytic metastases.13-15 Furthermore, in contrast to bone scans, PET scans can identify additional lesions in addition to bone lesion. According to recent reports, PET provides higher sensitivity and specificity in demonstrating lytic and sclerotic metastases compared with that of the bone scan.16

Breast Cancer

The role of PET for breast cancer is controversial. A study by Lonneux and colleagues found that PET is highly sensitive in confirming distant metastasis from breast cancer, whereas researchers reported a similar sensitivity but higher specificity.17 Ohta and colleagues reported that PET and bone scan had identical sensitivity (77.7%), but PET was more specific than the bone scan (97.6% vs 80.9%, respectively).14 The study conclusion by Cook and colleagues was that PET is superior to bone scan in the detection of metastatic osteolytic bone lesions from breast cancer, whereas osteoblastic metastatic bone lesions from breast cancer are less likely to be demonstrated on a PET scan.18

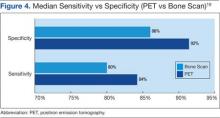

Houssami and Costelloe conducted a systematic review of 16 reported studies that comparatively tested the accuracy of imaging modalities for bone metastases in breast cancer.19 Sensitivity was generally similar between PET and bone scans in most studies reviewed. Four studies reported similar sensitivity but higher specificity for PET; the median specificity for PET and bone scan was 92% vs 85.5%, respectively (Figure 4).

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is now established as the “classic” cancer for false-negative results on PET. Positron emission tomography does not perform well in the identification of osteoblastic skeletal metastases from prostate cancer. Yeh and colleagues reported only 18% positivity with PET.20 Interestingly, however, progressive metastatic prostate cancer showed a higher yield of 77% sensitivity with PET, perhaps because active osseous disease can be better picked up by PET scans.21

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Lung Cancer

For non-small cell lung cancer, both bone scan and PET showed a similar sensitivity for bone metastases detection, but the PET scan was more specific than the bone scan. Lung cancer often metastasizes to bone: up to 36% of patients at postmortem study. Lung cancer with bone metastases has a poor prognosis with median survival time typically measured in months. Most patients with bone metastases develop complications, such as severe pain, bone fracture, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression. Bone-targeted therapies play a greater role in the management of lung cancer patients, aiming for delaying disease progression and preserving QOL.22,23

Therapeutic Strategy and Management

Major morbidities associated with bone metastases include severe pain, hypercalcemia, bone fractures, spinal compression fractures, and cord or nerve root compression. This section reviews appropriate management techniques reported in the literature, particularly external beam radiation therapy.

Radiation Therapy

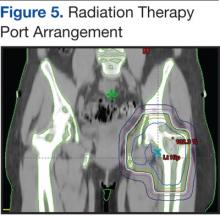

Pain is the most serious complication of bone metastases. Radiation therapy has been established as standard therapy and an effective pain palliation modality. Up to 80% of patients achieve partial pain relief, and > 33% of patients experience complete pain relief after radiation (Figure 5).24,25 Although a 3,000 cGy given over a 2-week period has been commonly used, a standard dose-fraction radiation treatment regimen has not been established.

The RTOG study was a randomized clinical study comparing various radiation schedules; 1,500 cGyin 1 week; vs 2,000 cGy in 1 week; vs 2,500 cGy in 1 week; vs 3,000 cGy in 2 weeks; or 4,050 cGy in 3 weeks. The conclusion was that local radiotherapy was an effective therapy for symptomatic and palliative therapy of bone metastases. Furthermore, low-dose radiotherapy was as good as various higher dose protracted courses of radiation treatments in terms of overall response rates (ORRs).24

Nearly 96% of patients eventually reported minimal pain relief to their palliative course of radiotherapy and experienced at least some pain relief within 4 weeks of radiation therapy. Complete pain relief was attained in 54% of patients regardless of the radiation dose-fraction schedules used. The median duration of complete pain response was about 12 weeks; > 70% of patients did not experience relapse of pain.26

Hartsell and colleagues investigated the efficacy of 800 cGy in a single fraction compared with 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions as part of a phase 3 randomized study of symptomatic therapy for pain palliation.27 The results showed 66% ORRs with similar complete and partial response rates (RRs) for both radiation groups. The complete RRs were 15% in the 800 cGy single-fraction arm vs 18% in the 3,000 cGy therapy arm, whereas partial RRs were 50% and 48% in the single vs the 3,000 cGy arms, respectively. However, there was a higher rate of retreatment for patients treated with the 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy. The 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy program seems rather popular in Canada and in European countries but is currently not widely used in the U.S.

Surgical Therapy

The surgical indications for managing bone metastases can vary, depending on disease location, surgeon’s preference, and patient’s overall disease status and related morbidities. Pain relief of fractured long bones (humerus, femur, or tibia) is crucial. The main goals of surgical intervention in these cases include the restoration of stability and functional mobility, pain control, and improving QOL. Weight-bearing bones (humerus/tibia) are especially at risk of bone fracture, and compromise of these is an indication of surgery. Postoperative external-beam radiation is recommended in most cases to eradicate residual microscopic disease or tumor progression.28

Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

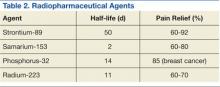

Bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals are effective and have been widely used for pain palliation. The usual indications for radiopharmaceutical therapy include diffuse osteoblastic skeletal metastases demonstrated on bone scan, painful bone metastases not responding well to analgesics, and hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. At present, strontium-89 (Sr-89), samarium-153 (Sm-153), phosphorus-32 (P-32), and radium 223 dichloride are radionuclides currently accepted as attractive therapeutic modalities for pain management (Table 2).

The clinical response is not immediate, and the average time to response is 1 to 2 weeks, but sometimes much longer. The main adverse reaction of systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy is myelotoxicity, such as thrombocytopenia and/or leukopenia. Occasionally, a so-called flare phenomenon of a transient pain increase may develop as well.29,30

Systemic Pharmacotherapy

Bisphosphonates are drugs commonly used to treat bone metastases. The benefits of bisphosphonate therapy are bone pain relief, the reduction of bone destruction, and the prevention of hypercalcemia and bone fractures. Bisphosphonates are typically more effective in osteolytic metastases and easily bind to bone, inhibiting bone resorption and increasing mineralization.31,32 Also, recent clinical studies suggest that bisphosphonates may inhibit tumor progression of bone metastases.

Related: Cancer Drugs Increase Rate of Preventable Hospital Admissions

Zoledronic acid is currently one of the most potent bisphosphonates and is effective in most types of metastatic bone lesions.33 Denosumab, another drug, diminishes osteoclast activity, leading to decreased bone resorption and increased bone mass.34,35 Denosumab is useful in preventing complications as a result of bone metastases from solid tumors and has been recently approved by the FDA for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and the prevention of skeletal-related events (SREs) in cancer patients with bone metastases.

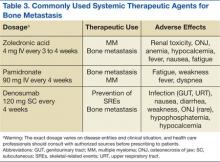

Adverse Effects

Zoledronate and bisphosphonates in general are not recommended for patients with kidney disease, including hypocalcaemia and severe renal impairment. A rare but well-known complication of bisphosphonate administration is osteonecrosis of the jaw, which is somewhat more common in MM, especially after dental extractions. General nonspecific adverse effects include fatigue, anemia, muscle aches, fever, and/or edema in the feet or legs. Flulike symptoms and generalized bone discomfort can also be seen shortly after the first infusion (Table 3).

Breast Cancer

Bisphosphonates have been shown to effectively prevent SREs in breast cancer patients with bone metastases.36 For example, zoledronic acid is the most effective bisphosphonate and has been demonstrated to significantly delay the time to development of a first SRE, reducing the overall SRE rate by 43%.37

Lung Cancer

According to Rosen and colleagues, lung cancer patients with bone metastases who received zoledronic acid (4 mg every 3 weeks) experienced a 9% reduction in SREs, a relative delay in median time to a first SRE, and a significantly reduced incidence of SREs.37

Prostate Cancer

Zoledronic acid is the only bisphosphonate that proved effective in the treatment of prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. Zoledronic acid significantly reduced the risk of SREs (36%) and bone pain as well as delayed the median time to first SRE (nearly 6 months).38,39

Multiple Myeloma

Bisphosphonates are recommended for bone metastases to prevent new bone lesions. Studies have shown pamidronate (90 mg every 4 weeks) resulted in a 41% reduction in SREs at 9 months and a 25% reduction at 21 months.40,41 Oral clodronate, another agent, also significantly reduced SREs and pain in patients with MM.42

Conclusion

Metastatic cancer with bone metastases occurs as cancer advances and spreads to the bone from the primary site of the original solid cancer. Nearly 70% of patients with prostate and breast cancers and about 30% to 40% of patients with lung cancer develop bone metastases. In addition, up to 95% of MMs involve bone. The most frequent and important symptom of bone metastasis is pain. In addition, bone metastasis causes bone fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord and nerve compression. Imaging studies, such as bone scans and PET studies, are useful tools in diagnosing bone metastases.

Therapeutic management of bone metastases is expanding and rapidly evolving. For better therapy outcomes, treatment should be both individualized and coordinated among the care team, including a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, surgeon, and radiologist. Available therapeutic modalities include radiation therapy, radiopharmaceutical therapy, surgery, and systemic pharmacotherapy (zoledronate, pamidronate, and denosumab).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225-249.

2. Cooleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-1763.

3. Hirabayashi H, Ebara S, Kinoshita T, et al. Clinical outcome and survival after palliative surgery for spinal metastases. Cancer. 2003;97(2):476-84.

4. van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SPDS, Vonk EJA, Marijnen CA, Leer JW; Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group. Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column. Cancer. 2005;103(2):320-328.

5. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243S-6249S.

6. Body JJ. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical and therapeutic aspects. Bone. 1992;13(suppl 1):S57-S62.

7. Siegel RS, Ma J, Zou Z, Jermal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9-29.

8. National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Myeloma. National Cancer Institute Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

9. Lentle BC, McGowan DG, Dierich H. Technetium-99M polyphosphate bone scanning in carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1974;46(5):543-548.

10. Söderlund V. Radiological diagnosis of skeletal metastases. Eur Radiol. 1996;6(5):587-595.

11. Flickinger FW, Sanal SM. Bone marrow MRI: Techniques and accuracy for detecting breast cancer metastases. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12(6):829-35.

12. Hamaoka T, Madewell JE, Podoloff DA, Hortobagyi GN, Ueno NT. Bone imaging in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2942-2953.

13. Daldrup-Link HE, Franzius C, Link TM et al. Whole-body MR imaging for detection of bone metastases in children and young adults: Comparison with skeletal scintigraphy and FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(1):229-236.

14. Ohta M, Tokuda Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Whole body PET for the evaluation of bony metastases in patients with breast cancer: Comparison with 99Tcm-MDP bone scintigraphy. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(8):875-879.

15. Koolen BB, Vegt E, Rutgers EJ, et al. FDG-avid sclerotic bone metastases in breast cancer patients: A PET/CT case series. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(1):86-91.

16. Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Flusser G, et al. Assessment of malignant skeletal disease: Initial experience with 18F-fluoride PET/CT and comparison between 18F-fluoride PET and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(2):272-278.

17. Lonneux M, Borbath II, Berlière M, Kirkove C, Pauwels S. The place of whole-body PET FDG for the diagnosis of distant recurrence of breast cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 2000;3(2):45-49.

18. Cook GJ, Houston S, Rubens R, Maisey MN, Fogelman I. Detection of bone metastases in breast cancer by 18FDG PET: Differing metabolic activity in osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3375-3379.

19. Houssami N, Costelloe CM. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: Evidence on comparative test accuracy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):834-843.

20. Yeh SD, Imbriaco M, Larson SM, et al. Detection of bony metastases of androgen-independent prostate cancer by PET-FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23(6):693-697.

21. Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I, et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59(6):913-918.

22. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, et al. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial—the Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3150-3157.

23. Hillner BE, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychology. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4042-4057.

24. Chow E, Harris K, Fan G, Tsao M, Size WM. Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1423-1436.

25. Wu JS, Wong R, Johnston M, Bezjak A, Whelan T; Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Supportive Care Group. Meta-analysis of dose-fractionation radiotherapy trials for the palliation of painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(3):594-605.

26. Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases. Final results of the study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893-899.

27. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

28. Frassica DA. General principles of external beam radiation therapy for skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415(suppl):S158-S164.

29. Silberstein EB. Systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy of painful osteoblastic metastases. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2000;10(3):240-249.

30. Neville-Webbe HL, Gnant M, Coleman RE. Potential anticancer properties of bisphosphonates. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S53-S65.

31. Loftus LS, Edwards-Bennett S, Sokol GH. Systemic therapy for bone metastases. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2):145-153.

32. Rosen L, Harland SJ, Oosterlinck W. Broad clinical activity of zoledronic acid in osteolytic to osteoblastic bone lesions in patients with a broad range of solid tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25(6)(suppl 1):S19-S24.

33. Fornier MN. Denosumab: Second chapter in controlling bone metastases or a new book? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5127-5131.

34. Mortimer JE, Pal SK. Safety considerations for use of bone-targeted agents in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S66-S72.

35. Pavlakis N, Schmidt R, Stockler M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD003474.

36. Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3314-3321.

37. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian NS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: A randomized, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2004;100(12):2613-2621.

38. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(11):879-882.

39. Saad F, Eastham J. Zoledronic acid improves clinical outcomes when administered before onset of bone pain in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2010;76(5):1175-1181.

40. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

41. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Long-term pamidronate treatment of advanced multiple myeloma patients reduces skeletal events. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):593-602.

42. Lahtinen R, Laakso M, Palva I, Virkkunen P, Elomaa I. Randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Finnish Leukaemia Group. Lancet. 1992;340(8827):1049-1052.

Bone metastasis is a relatively common complication of cancer, often developing as they advance, especially in prostate cancer and breast cancer. Bone metastasis can profoundly affect patients’ daily activities and quality of life (QOL) due to severe pain and associated major complications. Prompt palliative therapy is required for symptomatic pain relief and prevention of the devastating complications of bone metastasis.

Epidemiology

Bone is the most common and preferred site for metastatic involvement of cancer. Advanced cancers frequently develop metastases to the bone during the later phases of cancer progression. At least 100,000 patients develop bone metastases every year, although the exact number of bone metastases is not known.1 Multiple myeloma (MM), breast cancer, and prostate cancer are responsible for up to 70% of bone metastases cases.2 Gastrointestinal cancers contribute least to bone metastases: < 15% of all cases.2

Related: Effective Treatment Options for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

The prognosis of bone metastases is generally poor, although it partly depends on the primary site of the original cancer and on the presence of any additional metastases to visceral organs. For example, it is known that survival times are longer for patients with primary prostate or breast cancer than for patients with lung cancer primary tumors.3,4

Prostate and breast cancers are the most common primary cancers of bone metastases. At postmortem studies, patients who died of prostate cancer or breast cancer revealed evidence of bone metastases in up to 75% of cases (Figure 1). Regardless of their survival expectancy, however, most patients with bone metastasis need immediate medical attention and active palliative therapy to prevent devastating complications related to bone metastasis, such as pathologic bone fractures and severe bone pain.

Clinical Features

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is the second most common hematologic malignancy and is caused by an abnormal accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow. Characteristic clinical manifestations include bony destruction and related features of bone pain, anemia (80% of cases), hypocalcemia, and renal dysfunction. Pathologic fractures, renal failure, or hyperviscosity syndrome often develops. More than 20,000 new patients are diagnosed with MM and about 11,000 patients in the U.S. die of MM every year. Multiple myeloma and is twice as likely to develop in men as it is in women. A large number of MM cases are under the care of VAMCs (about 10%-12% of all MM cases).7,8

Abnormal laboratory tests show an elevated total protein level in the blood and/or urine (Bence Jones proteinuria). Serum electrophoresis detects M-protein in about 80% to 90% of patients. Patients may also present with renal failure. The differential diagnosis includes other malignancies, such as metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, leukemia, and monoclonal gammopathy.

Pathophysiology

Normal bone tissue is made up of 2 different types of cells: osteoblasts and osteoclasts. New bone is constantly being produced while old bone is broken down. When tumor cells invade bone, the cancer cells produce 1 of 2 distinct substances; as a result, either osteoclasts or osteoblasts are stimulated, depending on tumor type metastasized to the bone. The activated osteoclasts then dissolve the bone, weakening the bone (osteolytic phenomenon), and the osteoblasts stimulate bone formation, hardening the bone (osteoblastic or sclerotic process).

Diagnosis and Evaluation

The most important first step in evaluating bone metastasis in a patient is to take a thorough, careful medical history and perform a physical examination. The examination not only helps locate suspected sites of bone metastases, but also helps determine necessary diagnostic studies.

The radiographic appearance of bone metastasis can be classified into 4 groups: osteolytic, osteoblastic, osteoporotic, and mixed. Imaging characteristics of osteolytic lesions include the destruction/thinning of bone, whereas osteoblastic (osteosclerotic) lesions appear with excess deposition of new bones. In contrast to malignant osteolytic lesions, osteoporotic lesions look like faded bone without cortical destruction or increased density.

The main choice of imaging study for screening suspected bone metastases is usually the bone scan (Figure 3). Plain radiographs are not useful in the early detection of bone metastases, because bone lesions do not show up on plain films until 30% to 50% of the bone mineral is lost.5,9 Although most metastatic bone lesions represent a mixture of osteoblastic and -lytic processes, metastatic lesions of lung cancer and breast cancer are predominantly osteolytic in contrast to mainly osteoblastic lesions of prostate cancer metastases.10

The osteoblastic process of bone metastases is best demonstrated on a bone scan; however, a positive bone scan does not necessarily indicate bone metastases, because it is not highly specific of metastatic disease. Several benign bone lesions (such as osteoarthritis, traumatic injury, and Paget disease) also show positive readings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not useful in screening for bone metastases, but it is better in assessing bone metastases compared with a bone scan, because it is more sensitive, especially for spinal lesions. The reported sensitivity of MRI is 91% to 100%, whereas bone scan sensitivity is only 62% to 85%.11,12

Even though the bone scan has been assumed to be the best imaging study for bone metastases, positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be more useful in detecting osteolytic bone metastases, as they can light up areas of increased metabolic activity. Positron emission tomography scans, however, are less sensitive for osteoblastic metastases. An additional advantage of PET scans is that they can be used for whole-body scanning/surveillance to rule out visceral involvement.

Published studies indicate that bone scans better detect sclerotic bone metastases and PET scans are superior in revealing osteolytic metastases.13-15 Furthermore, in contrast to bone scans, PET scans can identify additional lesions in addition to bone lesion. According to recent reports, PET provides higher sensitivity and specificity in demonstrating lytic and sclerotic metastases compared with that of the bone scan.16

Breast Cancer

The role of PET for breast cancer is controversial. A study by Lonneux and colleagues found that PET is highly sensitive in confirming distant metastasis from breast cancer, whereas researchers reported a similar sensitivity but higher specificity.17 Ohta and colleagues reported that PET and bone scan had identical sensitivity (77.7%), but PET was more specific than the bone scan (97.6% vs 80.9%, respectively).14 The study conclusion by Cook and colleagues was that PET is superior to bone scan in the detection of metastatic osteolytic bone lesions from breast cancer, whereas osteoblastic metastatic bone lesions from breast cancer are less likely to be demonstrated on a PET scan.18

Houssami and Costelloe conducted a systematic review of 16 reported studies that comparatively tested the accuracy of imaging modalities for bone metastases in breast cancer.19 Sensitivity was generally similar between PET and bone scans in most studies reviewed. Four studies reported similar sensitivity but higher specificity for PET; the median specificity for PET and bone scan was 92% vs 85.5%, respectively (Figure 4).

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is now established as the “classic” cancer for false-negative results on PET. Positron emission tomography does not perform well in the identification of osteoblastic skeletal metastases from prostate cancer. Yeh and colleagues reported only 18% positivity with PET.20 Interestingly, however, progressive metastatic prostate cancer showed a higher yield of 77% sensitivity with PET, perhaps because active osseous disease can be better picked up by PET scans.21

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Lung Cancer

For non-small cell lung cancer, both bone scan and PET showed a similar sensitivity for bone metastases detection, but the PET scan was more specific than the bone scan. Lung cancer often metastasizes to bone: up to 36% of patients at postmortem study. Lung cancer with bone metastases has a poor prognosis with median survival time typically measured in months. Most patients with bone metastases develop complications, such as severe pain, bone fracture, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression. Bone-targeted therapies play a greater role in the management of lung cancer patients, aiming for delaying disease progression and preserving QOL.22,23

Therapeutic Strategy and Management

Major morbidities associated with bone metastases include severe pain, hypercalcemia, bone fractures, spinal compression fractures, and cord or nerve root compression. This section reviews appropriate management techniques reported in the literature, particularly external beam radiation therapy.

Radiation Therapy

Pain is the most serious complication of bone metastases. Radiation therapy has been established as standard therapy and an effective pain palliation modality. Up to 80% of patients achieve partial pain relief, and > 33% of patients experience complete pain relief after radiation (Figure 5).24,25 Although a 3,000 cGy given over a 2-week period has been commonly used, a standard dose-fraction radiation treatment regimen has not been established.

The RTOG study was a randomized clinical study comparing various radiation schedules; 1,500 cGyin 1 week; vs 2,000 cGy in 1 week; vs 2,500 cGy in 1 week; vs 3,000 cGy in 2 weeks; or 4,050 cGy in 3 weeks. The conclusion was that local radiotherapy was an effective therapy for symptomatic and palliative therapy of bone metastases. Furthermore, low-dose radiotherapy was as good as various higher dose protracted courses of radiation treatments in terms of overall response rates (ORRs).24

Nearly 96% of patients eventually reported minimal pain relief to their palliative course of radiotherapy and experienced at least some pain relief within 4 weeks of radiation therapy. Complete pain relief was attained in 54% of patients regardless of the radiation dose-fraction schedules used. The median duration of complete pain response was about 12 weeks; > 70% of patients did not experience relapse of pain.26

Hartsell and colleagues investigated the efficacy of 800 cGy in a single fraction compared with 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions as part of a phase 3 randomized study of symptomatic therapy for pain palliation.27 The results showed 66% ORRs with similar complete and partial response rates (RRs) for both radiation groups. The complete RRs were 15% in the 800 cGy single-fraction arm vs 18% in the 3,000 cGy therapy arm, whereas partial RRs were 50% and 48% in the single vs the 3,000 cGy arms, respectively. However, there was a higher rate of retreatment for patients treated with the 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy. The 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy program seems rather popular in Canada and in European countries but is currently not widely used in the U.S.

Surgical Therapy

The surgical indications for managing bone metastases can vary, depending on disease location, surgeon’s preference, and patient’s overall disease status and related morbidities. Pain relief of fractured long bones (humerus, femur, or tibia) is crucial. The main goals of surgical intervention in these cases include the restoration of stability and functional mobility, pain control, and improving QOL. Weight-bearing bones (humerus/tibia) are especially at risk of bone fracture, and compromise of these is an indication of surgery. Postoperative external-beam radiation is recommended in most cases to eradicate residual microscopic disease or tumor progression.28

Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

Bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals are effective and have been widely used for pain palliation. The usual indications for radiopharmaceutical therapy include diffuse osteoblastic skeletal metastases demonstrated on bone scan, painful bone metastases not responding well to analgesics, and hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. At present, strontium-89 (Sr-89), samarium-153 (Sm-153), phosphorus-32 (P-32), and radium 223 dichloride are radionuclides currently accepted as attractive therapeutic modalities for pain management (Table 2).

The clinical response is not immediate, and the average time to response is 1 to 2 weeks, but sometimes much longer. The main adverse reaction of systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy is myelotoxicity, such as thrombocytopenia and/or leukopenia. Occasionally, a so-called flare phenomenon of a transient pain increase may develop as well.29,30

Systemic Pharmacotherapy

Bisphosphonates are drugs commonly used to treat bone metastases. The benefits of bisphosphonate therapy are bone pain relief, the reduction of bone destruction, and the prevention of hypercalcemia and bone fractures. Bisphosphonates are typically more effective in osteolytic metastases and easily bind to bone, inhibiting bone resorption and increasing mineralization.31,32 Also, recent clinical studies suggest that bisphosphonates may inhibit tumor progression of bone metastases.

Related: Cancer Drugs Increase Rate of Preventable Hospital Admissions

Zoledronic acid is currently one of the most potent bisphosphonates and is effective in most types of metastatic bone lesions.33 Denosumab, another drug, diminishes osteoclast activity, leading to decreased bone resorption and increased bone mass.34,35 Denosumab is useful in preventing complications as a result of bone metastases from solid tumors and has been recently approved by the FDA for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and the prevention of skeletal-related events (SREs) in cancer patients with bone metastases.

Adverse Effects

Zoledronate and bisphosphonates in general are not recommended for patients with kidney disease, including hypocalcaemia and severe renal impairment. A rare but well-known complication of bisphosphonate administration is osteonecrosis of the jaw, which is somewhat more common in MM, especially after dental extractions. General nonspecific adverse effects include fatigue, anemia, muscle aches, fever, and/or edema in the feet or legs. Flulike symptoms and generalized bone discomfort can also be seen shortly after the first infusion (Table 3).

Breast Cancer

Bisphosphonates have been shown to effectively prevent SREs in breast cancer patients with bone metastases.36 For example, zoledronic acid is the most effective bisphosphonate and has been demonstrated to significantly delay the time to development of a first SRE, reducing the overall SRE rate by 43%.37

Lung Cancer

According to Rosen and colleagues, lung cancer patients with bone metastases who received zoledronic acid (4 mg every 3 weeks) experienced a 9% reduction in SREs, a relative delay in median time to a first SRE, and a significantly reduced incidence of SREs.37

Prostate Cancer

Zoledronic acid is the only bisphosphonate that proved effective in the treatment of prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. Zoledronic acid significantly reduced the risk of SREs (36%) and bone pain as well as delayed the median time to first SRE (nearly 6 months).38,39

Multiple Myeloma

Bisphosphonates are recommended for bone metastases to prevent new bone lesions. Studies have shown pamidronate (90 mg every 4 weeks) resulted in a 41% reduction in SREs at 9 months and a 25% reduction at 21 months.40,41 Oral clodronate, another agent, also significantly reduced SREs and pain in patients with MM.42

Conclusion

Metastatic cancer with bone metastases occurs as cancer advances and spreads to the bone from the primary site of the original solid cancer. Nearly 70% of patients with prostate and breast cancers and about 30% to 40% of patients with lung cancer develop bone metastases. In addition, up to 95% of MMs involve bone. The most frequent and important symptom of bone metastasis is pain. In addition, bone metastasis causes bone fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord and nerve compression. Imaging studies, such as bone scans and PET studies, are useful tools in diagnosing bone metastases.

Therapeutic management of bone metastases is expanding and rapidly evolving. For better therapy outcomes, treatment should be both individualized and coordinated among the care team, including a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, surgeon, and radiologist. Available therapeutic modalities include radiation therapy, radiopharmaceutical therapy, surgery, and systemic pharmacotherapy (zoledronate, pamidronate, and denosumab).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Bone metastasis is a relatively common complication of cancer, often developing as they advance, especially in prostate cancer and breast cancer. Bone metastasis can profoundly affect patients’ daily activities and quality of life (QOL) due to severe pain and associated major complications. Prompt palliative therapy is required for symptomatic pain relief and prevention of the devastating complications of bone metastasis.

Epidemiology

Bone is the most common and preferred site for metastatic involvement of cancer. Advanced cancers frequently develop metastases to the bone during the later phases of cancer progression. At least 100,000 patients develop bone metastases every year, although the exact number of bone metastases is not known.1 Multiple myeloma (MM), breast cancer, and prostate cancer are responsible for up to 70% of bone metastases cases.2 Gastrointestinal cancers contribute least to bone metastases: < 15% of all cases.2

Related: Effective Treatment Options for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

The prognosis of bone metastases is generally poor, although it partly depends on the primary site of the original cancer and on the presence of any additional metastases to visceral organs. For example, it is known that survival times are longer for patients with primary prostate or breast cancer than for patients with lung cancer primary tumors.3,4

Prostate and breast cancers are the most common primary cancers of bone metastases. At postmortem studies, patients who died of prostate cancer or breast cancer revealed evidence of bone metastases in up to 75% of cases (Figure 1). Regardless of their survival expectancy, however, most patients with bone metastasis need immediate medical attention and active palliative therapy to prevent devastating complications related to bone metastasis, such as pathologic bone fractures and severe bone pain.

Clinical Features

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is the second most common hematologic malignancy and is caused by an abnormal accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow. Characteristic clinical manifestations include bony destruction and related features of bone pain, anemia (80% of cases), hypocalcemia, and renal dysfunction. Pathologic fractures, renal failure, or hyperviscosity syndrome often develops. More than 20,000 new patients are diagnosed with MM and about 11,000 patients in the U.S. die of MM every year. Multiple myeloma and is twice as likely to develop in men as it is in women. A large number of MM cases are under the care of VAMCs (about 10%-12% of all MM cases).7,8

Abnormal laboratory tests show an elevated total protein level in the blood and/or urine (Bence Jones proteinuria). Serum electrophoresis detects M-protein in about 80% to 90% of patients. Patients may also present with renal failure. The differential diagnosis includes other malignancies, such as metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, leukemia, and monoclonal gammopathy.

Pathophysiology

Normal bone tissue is made up of 2 different types of cells: osteoblasts and osteoclasts. New bone is constantly being produced while old bone is broken down. When tumor cells invade bone, the cancer cells produce 1 of 2 distinct substances; as a result, either osteoclasts or osteoblasts are stimulated, depending on tumor type metastasized to the bone. The activated osteoclasts then dissolve the bone, weakening the bone (osteolytic phenomenon), and the osteoblasts stimulate bone formation, hardening the bone (osteoblastic or sclerotic process).

Diagnosis and Evaluation

The most important first step in evaluating bone metastasis in a patient is to take a thorough, careful medical history and perform a physical examination. The examination not only helps locate suspected sites of bone metastases, but also helps determine necessary diagnostic studies.

The radiographic appearance of bone metastasis can be classified into 4 groups: osteolytic, osteoblastic, osteoporotic, and mixed. Imaging characteristics of osteolytic lesions include the destruction/thinning of bone, whereas osteoblastic (osteosclerotic) lesions appear with excess deposition of new bones. In contrast to malignant osteolytic lesions, osteoporotic lesions look like faded bone without cortical destruction or increased density.

The main choice of imaging study for screening suspected bone metastases is usually the bone scan (Figure 3). Plain radiographs are not useful in the early detection of bone metastases, because bone lesions do not show up on plain films until 30% to 50% of the bone mineral is lost.5,9 Although most metastatic bone lesions represent a mixture of osteoblastic and -lytic processes, metastatic lesions of lung cancer and breast cancer are predominantly osteolytic in contrast to mainly osteoblastic lesions of prostate cancer metastases.10

The osteoblastic process of bone metastases is best demonstrated on a bone scan; however, a positive bone scan does not necessarily indicate bone metastases, because it is not highly specific of metastatic disease. Several benign bone lesions (such as osteoarthritis, traumatic injury, and Paget disease) also show positive readings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not useful in screening for bone metastases, but it is better in assessing bone metastases compared with a bone scan, because it is more sensitive, especially for spinal lesions. The reported sensitivity of MRI is 91% to 100%, whereas bone scan sensitivity is only 62% to 85%.11,12

Even though the bone scan has been assumed to be the best imaging study for bone metastases, positron emission tomography (PET) scans can be more useful in detecting osteolytic bone metastases, as they can light up areas of increased metabolic activity. Positron emission tomography scans, however, are less sensitive for osteoblastic metastases. An additional advantage of PET scans is that they can be used for whole-body scanning/surveillance to rule out visceral involvement.

Published studies indicate that bone scans better detect sclerotic bone metastases and PET scans are superior in revealing osteolytic metastases.13-15 Furthermore, in contrast to bone scans, PET scans can identify additional lesions in addition to bone lesion. According to recent reports, PET provides higher sensitivity and specificity in demonstrating lytic and sclerotic metastases compared with that of the bone scan.16

Breast Cancer

The role of PET for breast cancer is controversial. A study by Lonneux and colleagues found that PET is highly sensitive in confirming distant metastasis from breast cancer, whereas researchers reported a similar sensitivity but higher specificity.17 Ohta and colleagues reported that PET and bone scan had identical sensitivity (77.7%), but PET was more specific than the bone scan (97.6% vs 80.9%, respectively).14 The study conclusion by Cook and colleagues was that PET is superior to bone scan in the detection of metastatic osteolytic bone lesions from breast cancer, whereas osteoblastic metastatic bone lesions from breast cancer are less likely to be demonstrated on a PET scan.18

Houssami and Costelloe conducted a systematic review of 16 reported studies that comparatively tested the accuracy of imaging modalities for bone metastases in breast cancer.19 Sensitivity was generally similar between PET and bone scans in most studies reviewed. Four studies reported similar sensitivity but higher specificity for PET; the median specificity for PET and bone scan was 92% vs 85.5%, respectively (Figure 4).

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is now established as the “classic” cancer for false-negative results on PET. Positron emission tomography does not perform well in the identification of osteoblastic skeletal metastases from prostate cancer. Yeh and colleagues reported only 18% positivity with PET.20 Interestingly, however, progressive metastatic prostate cancer showed a higher yield of 77% sensitivity with PET, perhaps because active osseous disease can be better picked up by PET scans.21

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Lung Cancer

For non-small cell lung cancer, both bone scan and PET showed a similar sensitivity for bone metastases detection, but the PET scan was more specific than the bone scan. Lung cancer often metastasizes to bone: up to 36% of patients at postmortem study. Lung cancer with bone metastases has a poor prognosis with median survival time typically measured in months. Most patients with bone metastases develop complications, such as severe pain, bone fracture, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression. Bone-targeted therapies play a greater role in the management of lung cancer patients, aiming for delaying disease progression and preserving QOL.22,23

Therapeutic Strategy and Management

Major morbidities associated with bone metastases include severe pain, hypercalcemia, bone fractures, spinal compression fractures, and cord or nerve root compression. This section reviews appropriate management techniques reported in the literature, particularly external beam radiation therapy.

Radiation Therapy

Pain is the most serious complication of bone metastases. Radiation therapy has been established as standard therapy and an effective pain palliation modality. Up to 80% of patients achieve partial pain relief, and > 33% of patients experience complete pain relief after radiation (Figure 5).24,25 Although a 3,000 cGy given over a 2-week period has been commonly used, a standard dose-fraction radiation treatment regimen has not been established.

The RTOG study was a randomized clinical study comparing various radiation schedules; 1,500 cGyin 1 week; vs 2,000 cGy in 1 week; vs 2,500 cGy in 1 week; vs 3,000 cGy in 2 weeks; or 4,050 cGy in 3 weeks. The conclusion was that local radiotherapy was an effective therapy for symptomatic and palliative therapy of bone metastases. Furthermore, low-dose radiotherapy was as good as various higher dose protracted courses of radiation treatments in terms of overall response rates (ORRs).24

Nearly 96% of patients eventually reported minimal pain relief to their palliative course of radiotherapy and experienced at least some pain relief within 4 weeks of radiation therapy. Complete pain relief was attained in 54% of patients regardless of the radiation dose-fraction schedules used. The median duration of complete pain response was about 12 weeks; > 70% of patients did not experience relapse of pain.26

Hartsell and colleagues investigated the efficacy of 800 cGy in a single fraction compared with 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions as part of a phase 3 randomized study of symptomatic therapy for pain palliation.27 The results showed 66% ORRs with similar complete and partial response rates (RRs) for both radiation groups. The complete RRs were 15% in the 800 cGy single-fraction arm vs 18% in the 3,000 cGy therapy arm, whereas partial RRs were 50% and 48% in the single vs the 3,000 cGy arms, respectively. However, there was a higher rate of retreatment for patients treated with the 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy. The 800 cGy single-fraction radiotherapy program seems rather popular in Canada and in European countries but is currently not widely used in the U.S.

Surgical Therapy

The surgical indications for managing bone metastases can vary, depending on disease location, surgeon’s preference, and patient’s overall disease status and related morbidities. Pain relief of fractured long bones (humerus, femur, or tibia) is crucial. The main goals of surgical intervention in these cases include the restoration of stability and functional mobility, pain control, and improving QOL. Weight-bearing bones (humerus/tibia) are especially at risk of bone fracture, and compromise of these is an indication of surgery. Postoperative external-beam radiation is recommended in most cases to eradicate residual microscopic disease or tumor progression.28

Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

Bone-seeking radiopharmaceuticals are effective and have been widely used for pain palliation. The usual indications for radiopharmaceutical therapy include diffuse osteoblastic skeletal metastases demonstrated on bone scan, painful bone metastases not responding well to analgesics, and hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. At present, strontium-89 (Sr-89), samarium-153 (Sm-153), phosphorus-32 (P-32), and radium 223 dichloride are radionuclides currently accepted as attractive therapeutic modalities for pain management (Table 2).

The clinical response is not immediate, and the average time to response is 1 to 2 weeks, but sometimes much longer. The main adverse reaction of systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy is myelotoxicity, such as thrombocytopenia and/or leukopenia. Occasionally, a so-called flare phenomenon of a transient pain increase may develop as well.29,30

Systemic Pharmacotherapy

Bisphosphonates are drugs commonly used to treat bone metastases. The benefits of bisphosphonate therapy are bone pain relief, the reduction of bone destruction, and the prevention of hypercalcemia and bone fractures. Bisphosphonates are typically more effective in osteolytic metastases and easily bind to bone, inhibiting bone resorption and increasing mineralization.31,32 Also, recent clinical studies suggest that bisphosphonates may inhibit tumor progression of bone metastases.

Related: Cancer Drugs Increase Rate of Preventable Hospital Admissions

Zoledronic acid is currently one of the most potent bisphosphonates and is effective in most types of metastatic bone lesions.33 Denosumab, another drug, diminishes osteoclast activity, leading to decreased bone resorption and increased bone mass.34,35 Denosumab is useful in preventing complications as a result of bone metastases from solid tumors and has been recently approved by the FDA for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and the prevention of skeletal-related events (SREs) in cancer patients with bone metastases.

Adverse Effects

Zoledronate and bisphosphonates in general are not recommended for patients with kidney disease, including hypocalcaemia and severe renal impairment. A rare but well-known complication of bisphosphonate administration is osteonecrosis of the jaw, which is somewhat more common in MM, especially after dental extractions. General nonspecific adverse effects include fatigue, anemia, muscle aches, fever, and/or edema in the feet or legs. Flulike symptoms and generalized bone discomfort can also be seen shortly after the first infusion (Table 3).

Breast Cancer

Bisphosphonates have been shown to effectively prevent SREs in breast cancer patients with bone metastases.36 For example, zoledronic acid is the most effective bisphosphonate and has been demonstrated to significantly delay the time to development of a first SRE, reducing the overall SRE rate by 43%.37

Lung Cancer

According to Rosen and colleagues, lung cancer patients with bone metastases who received zoledronic acid (4 mg every 3 weeks) experienced a 9% reduction in SREs, a relative delay in median time to a first SRE, and a significantly reduced incidence of SREs.37

Prostate Cancer

Zoledronic acid is the only bisphosphonate that proved effective in the treatment of prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. Zoledronic acid significantly reduced the risk of SREs (36%) and bone pain as well as delayed the median time to first SRE (nearly 6 months).38,39

Multiple Myeloma

Bisphosphonates are recommended for bone metastases to prevent new bone lesions. Studies have shown pamidronate (90 mg every 4 weeks) resulted in a 41% reduction in SREs at 9 months and a 25% reduction at 21 months.40,41 Oral clodronate, another agent, also significantly reduced SREs and pain in patients with MM.42

Conclusion

Metastatic cancer with bone metastases occurs as cancer advances and spreads to the bone from the primary site of the original solid cancer. Nearly 70% of patients with prostate and breast cancers and about 30% to 40% of patients with lung cancer develop bone metastases. In addition, up to 95% of MMs involve bone. The most frequent and important symptom of bone metastasis is pain. In addition, bone metastasis causes bone fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord and nerve compression. Imaging studies, such as bone scans and PET studies, are useful tools in diagnosing bone metastases.

Therapeutic management of bone metastases is expanding and rapidly evolving. For better therapy outcomes, treatment should be both individualized and coordinated among the care team, including a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, surgeon, and radiologist. Available therapeutic modalities include radiation therapy, radiopharmaceutical therapy, surgery, and systemic pharmacotherapy (zoledronate, pamidronate, and denosumab).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225-249.

2. Cooleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-1763.

3. Hirabayashi H, Ebara S, Kinoshita T, et al. Clinical outcome and survival after palliative surgery for spinal metastases. Cancer. 2003;97(2):476-84.

4. van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SPDS, Vonk EJA, Marijnen CA, Leer JW; Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group. Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column. Cancer. 2005;103(2):320-328.

5. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243S-6249S.

6. Body JJ. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical and therapeutic aspects. Bone. 1992;13(suppl 1):S57-S62.

7. Siegel RS, Ma J, Zou Z, Jermal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9-29.

8. National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Myeloma. National Cancer Institute Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

9. Lentle BC, McGowan DG, Dierich H. Technetium-99M polyphosphate bone scanning in carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1974;46(5):543-548.

10. Söderlund V. Radiological diagnosis of skeletal metastases. Eur Radiol. 1996;6(5):587-595.

11. Flickinger FW, Sanal SM. Bone marrow MRI: Techniques and accuracy for detecting breast cancer metastases. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12(6):829-35.

12. Hamaoka T, Madewell JE, Podoloff DA, Hortobagyi GN, Ueno NT. Bone imaging in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2942-2953.

13. Daldrup-Link HE, Franzius C, Link TM et al. Whole-body MR imaging for detection of bone metastases in children and young adults: Comparison with skeletal scintigraphy and FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(1):229-236.

14. Ohta M, Tokuda Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Whole body PET for the evaluation of bony metastases in patients with breast cancer: Comparison with 99Tcm-MDP bone scintigraphy. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(8):875-879.

15. Koolen BB, Vegt E, Rutgers EJ, et al. FDG-avid sclerotic bone metastases in breast cancer patients: A PET/CT case series. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(1):86-91.

16. Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Flusser G, et al. Assessment of malignant skeletal disease: Initial experience with 18F-fluoride PET/CT and comparison between 18F-fluoride PET and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(2):272-278.

17. Lonneux M, Borbath II, Berlière M, Kirkove C, Pauwels S. The place of whole-body PET FDG for the diagnosis of distant recurrence of breast cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 2000;3(2):45-49.

18. Cook GJ, Houston S, Rubens R, Maisey MN, Fogelman I. Detection of bone metastases in breast cancer by 18FDG PET: Differing metabolic activity in osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3375-3379.

19. Houssami N, Costelloe CM. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: Evidence on comparative test accuracy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):834-843.

20. Yeh SD, Imbriaco M, Larson SM, et al. Detection of bony metastases of androgen-independent prostate cancer by PET-FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23(6):693-697.

21. Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I, et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59(6):913-918.

22. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, et al. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial—the Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3150-3157.

23. Hillner BE, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychology. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4042-4057.

24. Chow E, Harris K, Fan G, Tsao M, Size WM. Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1423-1436.

25. Wu JS, Wong R, Johnston M, Bezjak A, Whelan T; Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Supportive Care Group. Meta-analysis of dose-fractionation radiotherapy trials for the palliation of painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(3):594-605.

26. Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases. Final results of the study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893-899.

27. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

28. Frassica DA. General principles of external beam radiation therapy for skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415(suppl):S158-S164.

29. Silberstein EB. Systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy of painful osteoblastic metastases. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2000;10(3):240-249.

30. Neville-Webbe HL, Gnant M, Coleman RE. Potential anticancer properties of bisphosphonates. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S53-S65.

31. Loftus LS, Edwards-Bennett S, Sokol GH. Systemic therapy for bone metastases. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2):145-153.

32. Rosen L, Harland SJ, Oosterlinck W. Broad clinical activity of zoledronic acid in osteolytic to osteoblastic bone lesions in patients with a broad range of solid tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25(6)(suppl 1):S19-S24.

33. Fornier MN. Denosumab: Second chapter in controlling bone metastases or a new book? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5127-5131.

34. Mortimer JE, Pal SK. Safety considerations for use of bone-targeted agents in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S66-S72.

35. Pavlakis N, Schmidt R, Stockler M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD003474.

36. Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3314-3321.

37. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian NS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: A randomized, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2004;100(12):2613-2621.

38. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(11):879-882.

39. Saad F, Eastham J. Zoledronic acid improves clinical outcomes when administered before onset of bone pain in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2010;76(5):1175-1181.

40. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

41. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Long-term pamidronate treatment of advanced multiple myeloma patients reduces skeletal events. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):593-602.

42. Lahtinen R, Laakso M, Palva I, Virkkunen P, Elomaa I. Randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Finnish Leukaemia Group. Lancet. 1992;340(8827):1049-1052.

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225-249.

2. Cooleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27(3):165-1763.

3. Hirabayashi H, Ebara S, Kinoshita T, et al. Clinical outcome and survival after palliative surgery for spinal metastases. Cancer. 2003;97(2):476-84.

4. van der Linden YM, Dijkstra SPDS, Vonk EJA, Marijnen CA, Leer JW; Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group. Prediction of survival in patients with metastases in the spinal column. Cancer. 2005;103(2):320-328.

5. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243S-6249S.

6. Body JJ. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical and therapeutic aspects. Bone. 1992;13(suppl 1):S57-S62.

7. Siegel RS, Ma J, Zou Z, Jermal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9-29.

8. National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: Myeloma. National Cancer Institute Website. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

9. Lentle BC, McGowan DG, Dierich H. Technetium-99M polyphosphate bone scanning in carcinoma of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1974;46(5):543-548.

10. Söderlund V. Radiological diagnosis of skeletal metastases. Eur Radiol. 1996;6(5):587-595.

11. Flickinger FW, Sanal SM. Bone marrow MRI: Techniques and accuracy for detecting breast cancer metastases. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12(6):829-35.

12. Hamaoka T, Madewell JE, Podoloff DA, Hortobagyi GN, Ueno NT. Bone imaging in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2942-2953.

13. Daldrup-Link HE, Franzius C, Link TM et al. Whole-body MR imaging for detection of bone metastases in children and young adults: Comparison with skeletal scintigraphy and FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(1):229-236.

14. Ohta M, Tokuda Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Whole body PET for the evaluation of bony metastases in patients with breast cancer: Comparison with 99Tcm-MDP bone scintigraphy. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(8):875-879.

15. Koolen BB, Vegt E, Rutgers EJ, et al. FDG-avid sclerotic bone metastases in breast cancer patients: A PET/CT case series. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(1):86-91.

16. Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Flusser G, et al. Assessment of malignant skeletal disease: Initial experience with 18F-fluoride PET/CT and comparison between 18F-fluoride PET and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(2):272-278.

17. Lonneux M, Borbath II, Berlière M, Kirkove C, Pauwels S. The place of whole-body PET FDG for the diagnosis of distant recurrence of breast cancer. Clin Positron Imaging. 2000;3(2):45-49.

18. Cook GJ, Houston S, Rubens R, Maisey MN, Fogelman I. Detection of bone metastases in breast cancer by 18FDG PET: Differing metabolic activity in osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3375-3379.

19. Houssami N, Costelloe CM. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: Evidence on comparative test accuracy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):834-843.

20. Yeh SD, Imbriaco M, Larson SM, et al. Detection of bony metastases of androgen-independent prostate cancer by PET-FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23(6):693-697.

21. Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I, et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59(6):913-918.

22. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, et al. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial—the Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3150-3157.

23. Hillner BE, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychology. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(21):4042-4057.

24. Chow E, Harris K, Fan G, Tsao M, Size WM. Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1423-1436.

25. Wu JS, Wong R, Johnston M, Bezjak A, Whelan T; Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Supportive Care Group. Meta-analysis of dose-fractionation radiotherapy trials for the palliation of painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(3):594-605.

26. Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases. Final results of the study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893-899.

27. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

28. Frassica DA. General principles of external beam radiation therapy for skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415(suppl):S158-S164.

29. Silberstein EB. Systemic radiopharmaceutical therapy of painful osteoblastic metastases. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2000;10(3):240-249.

30. Neville-Webbe HL, Gnant M, Coleman RE. Potential anticancer properties of bisphosphonates. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S53-S65.

31. Loftus LS, Edwards-Bennett S, Sokol GH. Systemic therapy for bone metastases. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2):145-153.

32. Rosen L, Harland SJ, Oosterlinck W. Broad clinical activity of zoledronic acid in osteolytic to osteoblastic bone lesions in patients with a broad range of solid tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25(6)(suppl 1):S19-S24.

33. Fornier MN. Denosumab: Second chapter in controlling bone metastases or a new book? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5127-5131.

34. Mortimer JE, Pal SK. Safety considerations for use of bone-targeted agents in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(suppl 1):S66-S72.

35. Pavlakis N, Schmidt R, Stockler M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD003474.

36. Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3314-3321.

37. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian NS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: A randomized, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer. 2004;100(12):2613-2621.

38. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(11):879-882.

39. Saad F, Eastham J. Zoledronic acid improves clinical outcomes when administered before onset of bone pain in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2010;76(5):1175-1181.

40. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal events in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):488-493.

41. Berenson JR, Lichtenstein A, Porter L, et al. Long-term pamidronate treatment of advanced multiple myeloma patients reduces skeletal events. Myeloma Aredia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):593-602.

42. Lahtinen R, Laakso M, Palva I, Virkkunen P, Elomaa I. Randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial of clodronate in multiple myeloma. Finnish Leukaemia Group. Lancet. 1992;340(8827):1049-1052.

Targeted Therapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

This presentation by Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, from the 2014 AVAHO Meeting in Portland, Oregon, provides an overview of new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of CLL, how to interpret molecular targets during treatment, and the advantages and disadvantages of these treatment options for patients.

"The standard of care today is really chemo-immunotherapy," Wiestner said. "Ideally, we would like to have a more disease-directed therapy that is tolerable and active."

Treating Hodgkin Lymphoma

Christopher Flowers, MD, discusses current management strategies for newly diagnosed and relapsed patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL). He also discusses emerging opportunities for the use of novel approaches to treat HL and surveillance of patients with this type of cancer.