User login

Prepare for ‘the coming tsunami’ of NAFLD

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

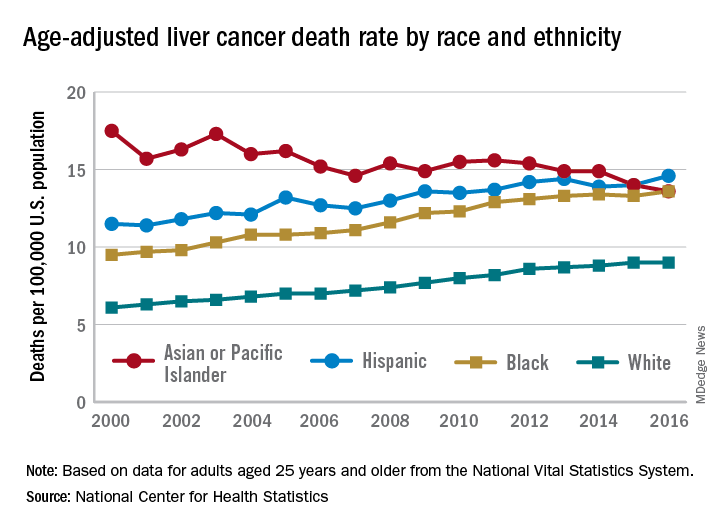

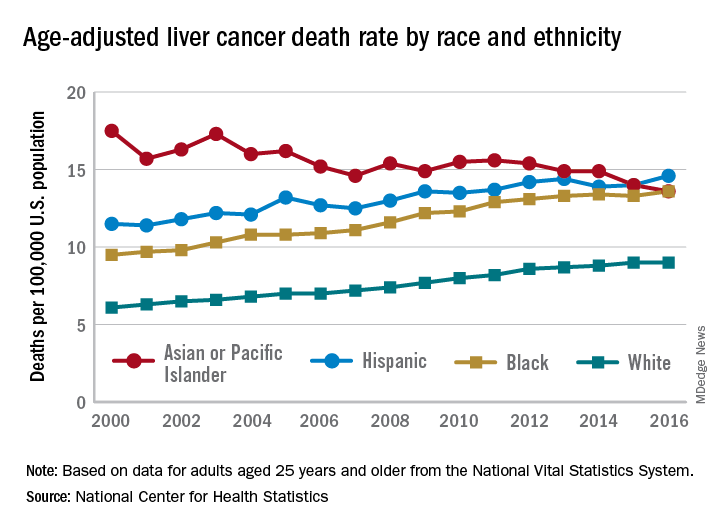

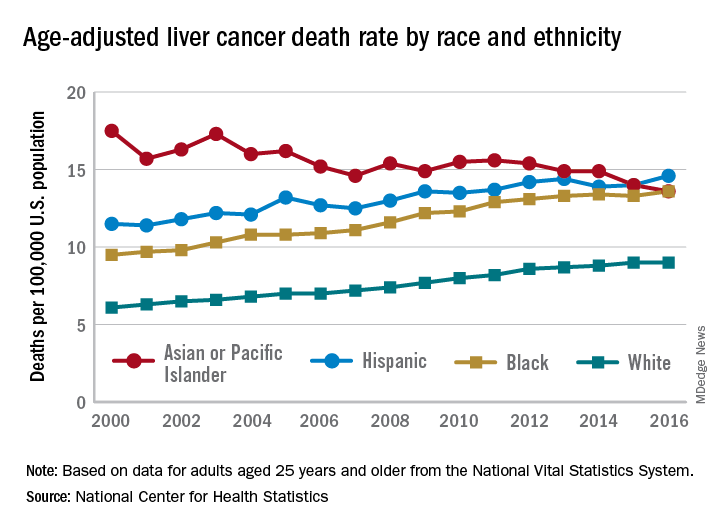

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Weight gain linked to progression of fibrosis in NAFLD patients

according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Researchers evaluated 40,700 Korean adults (minimum age, 18 years) with NAFLD who underwent health screenings during 2002-2016 with a median 6-year follow-up. Patients were categorized and placed into weight quintiles based on whether they lost weight (quintile 1, 2.3-kg or greater weight loss; quintile 2, 2.2-kg to 0.6-kg weight loss), gained weight (quintile 4, 0.7- to 2.1-kg weight gain; quintile 5, at least 2.2-kg or greater weight gain) or whether their weight remained stable (quintile 3, 0.5-kg weight loss to 0.6-kg weight gain). Researchers followed patients from baseline to fibrosis progression or last visit, calculated as person-years, and used the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) to measure outcomes. They defined body mass index based on criteria specific to Asian populations, with underweight categorized as less than 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight as 18.5-23 kg/m2, overweight as 23-25 kg/m2, and obese as at least 25 kg/m2.

“Our findings from mostly asymptomatic, relatively young individuals with ultrasonographically detected steatosis, possibly reflecting low-risk NAFLD patients, are less likely to be affected by survivor bias and biases related to comorbidities, compared with previous findings from cohorts of high-risk groups that underwent liver biopsy,” Seungho Ryu, MD, PhD, from Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in the study.

There were 5,454 participants who progressed from a low APRI to an intermediate or high APRI within 275,451.5 person-years, researchers said. Compared with the stable-weight group, hazard ratios for APRI progression in the first weight-change quintile were 0.68 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.74) and 0.86 in the second weight-change quintile (95% CI, 0.78-0.94). In the weight-gain groups, an increase in weight was associated with APRI progression in the fourth quintile (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07-1.28) and fifth quintile (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.58-1.85) groups.

After multivariable adjustment, there was an increase in APRI progression among patients with BMIs between 23 and 24.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.26), between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.28-1.55), and greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.86-2.36) compared with patients with a BMI between 18.5 and 22.9 kg/m2,.

Limitations of the study included the use of ultrasonography in place of liver biopsy for diagnosing NAFLD and the use of APRI to predict fibrosis in individuals with NAFLD, researchers said.

“APRI has demonstrated a reasonable utility as a noninvasive method for the prediction of histologically confirmed advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Ryu and colleagues wrote. “Nonetheless, we acknowledge that there is no currently available longitudinal data to support the use of worsening noninvasive fibrosis markers as an indicator of histological progression of fibrosis stage over time.”

Other limitations included the study’s retrospective design, lack of availability of medication use and dietary intake, and lack of generalization based on a young, healthy population of mostly Korean employees who were employed by companies or local government. However, researchers said clinicians should encourage their patients with NAFLD to maintain a healthy weight to avoid progression of fibrosis.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.006.

according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Researchers evaluated 40,700 Korean adults (minimum age, 18 years) with NAFLD who underwent health screenings during 2002-2016 with a median 6-year follow-up. Patients were categorized and placed into weight quintiles based on whether they lost weight (quintile 1, 2.3-kg or greater weight loss; quintile 2, 2.2-kg to 0.6-kg weight loss), gained weight (quintile 4, 0.7- to 2.1-kg weight gain; quintile 5, at least 2.2-kg or greater weight gain) or whether their weight remained stable (quintile 3, 0.5-kg weight loss to 0.6-kg weight gain). Researchers followed patients from baseline to fibrosis progression or last visit, calculated as person-years, and used the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) to measure outcomes. They defined body mass index based on criteria specific to Asian populations, with underweight categorized as less than 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight as 18.5-23 kg/m2, overweight as 23-25 kg/m2, and obese as at least 25 kg/m2.

“Our findings from mostly asymptomatic, relatively young individuals with ultrasonographically detected steatosis, possibly reflecting low-risk NAFLD patients, are less likely to be affected by survivor bias and biases related to comorbidities, compared with previous findings from cohorts of high-risk groups that underwent liver biopsy,” Seungho Ryu, MD, PhD, from Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in the study.

There were 5,454 participants who progressed from a low APRI to an intermediate or high APRI within 275,451.5 person-years, researchers said. Compared with the stable-weight group, hazard ratios for APRI progression in the first weight-change quintile were 0.68 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.74) and 0.86 in the second weight-change quintile (95% CI, 0.78-0.94). In the weight-gain groups, an increase in weight was associated with APRI progression in the fourth quintile (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07-1.28) and fifth quintile (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.58-1.85) groups.

After multivariable adjustment, there was an increase in APRI progression among patients with BMIs between 23 and 24.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.26), between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.28-1.55), and greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.86-2.36) compared with patients with a BMI between 18.5 and 22.9 kg/m2,.

Limitations of the study included the use of ultrasonography in place of liver biopsy for diagnosing NAFLD and the use of APRI to predict fibrosis in individuals with NAFLD, researchers said.

“APRI has demonstrated a reasonable utility as a noninvasive method for the prediction of histologically confirmed advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Ryu and colleagues wrote. “Nonetheless, we acknowledge that there is no currently available longitudinal data to support the use of worsening noninvasive fibrosis markers as an indicator of histological progression of fibrosis stage over time.”

Other limitations included the study’s retrospective design, lack of availability of medication use and dietary intake, and lack of generalization based on a young, healthy population of mostly Korean employees who were employed by companies or local government. However, researchers said clinicians should encourage their patients with NAFLD to maintain a healthy weight to avoid progression of fibrosis.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.006.

according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Researchers evaluated 40,700 Korean adults (minimum age, 18 years) with NAFLD who underwent health screenings during 2002-2016 with a median 6-year follow-up. Patients were categorized and placed into weight quintiles based on whether they lost weight (quintile 1, 2.3-kg or greater weight loss; quintile 2, 2.2-kg to 0.6-kg weight loss), gained weight (quintile 4, 0.7- to 2.1-kg weight gain; quintile 5, at least 2.2-kg or greater weight gain) or whether their weight remained stable (quintile 3, 0.5-kg weight loss to 0.6-kg weight gain). Researchers followed patients from baseline to fibrosis progression or last visit, calculated as person-years, and used the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) to measure outcomes. They defined body mass index based on criteria specific to Asian populations, with underweight categorized as less than 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight as 18.5-23 kg/m2, overweight as 23-25 kg/m2, and obese as at least 25 kg/m2.

“Our findings from mostly asymptomatic, relatively young individuals with ultrasonographically detected steatosis, possibly reflecting low-risk NAFLD patients, are less likely to be affected by survivor bias and biases related to comorbidities, compared with previous findings from cohorts of high-risk groups that underwent liver biopsy,” Seungho Ryu, MD, PhD, from Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in the study.

There were 5,454 participants who progressed from a low APRI to an intermediate or high APRI within 275,451.5 person-years, researchers said. Compared with the stable-weight group, hazard ratios for APRI progression in the first weight-change quintile were 0.68 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.74) and 0.86 in the second weight-change quintile (95% CI, 0.78-0.94). In the weight-gain groups, an increase in weight was associated with APRI progression in the fourth quintile (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07-1.28) and fifth quintile (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.58-1.85) groups.

After multivariable adjustment, there was an increase in APRI progression among patients with BMIs between 23 and 24.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.26), between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.28-1.55), and greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2 (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.86-2.36) compared with patients with a BMI between 18.5 and 22.9 kg/m2,.

Limitations of the study included the use of ultrasonography in place of liver biopsy for diagnosing NAFLD and the use of APRI to predict fibrosis in individuals with NAFLD, researchers said.

“APRI has demonstrated a reasonable utility as a noninvasive method for the prediction of histologically confirmed advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Ryu and colleagues wrote. “Nonetheless, we acknowledge that there is no currently available longitudinal data to support the use of worsening noninvasive fibrosis markers as an indicator of histological progression of fibrosis stage over time.”

Other limitations included the study’s retrospective design, lack of availability of medication use and dietary intake, and lack of generalization based on a young, healthy population of mostly Korean employees who were employed by companies or local government. However, researchers said clinicians should encourage their patients with NAFLD to maintain a healthy weight to avoid progression of fibrosis.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.006.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Obesity and weight gain were linked to progression of fibrosis in adults with NAFLD.

Major finding: Degree of weight change was associated with risk of fibrosis progression; patients who gained weight in quintile 4 and quintile 5 had hazard ratios of 1.17 and 1.71, respectively, when compared with the quintile of patients whose weight remained stable.

Data source: A retrospective study of 40,700 Korean adults with NAFLD who underwent health screenings during 2002-2016 with a median 6-year follow-up.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Kim Y et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.006.

Liver enzymes: No trivial elevations, even if asymptomatic

Elevated levels of circulating enzymes that are frequently of hepatic origin (aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase) and bilirubin in the absence of symptoms are common in clinical practice. A dogmatic but true statement holds that there are no trivial elevations in these substances. All persistent elevations of liver enzymes need a methodical evaluation and an appropriate working diagnosis.1

Here, we outline a framework for the workup and treatment of common causes of liver enzyme elevations.

PATTERN OF ELEVATION: CHOLESTATIC OR HEPATOCELLULAR

Based on the pattern of elevation, causes of elevated liver enzymes can be sorted into disorders of cholestasis and disorders of hepatocellular injury (Table 1).1

Cholestatic disorders tend to cause elevations in alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT).

Hepatocellular injury raises levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

HOW SHOULD ABNORMAL RESULTS BE EVALUATED?

When approaching liver enzyme elevations, the clinician should develop a working differential diagnosis based on the medical and social history and physical examination.

Think about alcohol, drugs, and fat

The most common causes of liver enzyme elevation are alcohol toxicity, medication overdose, and fatty liver disease.

Alcohol intake should be ascertained. “Significant” consumption is defined as more than 21 drinks per week in men or more than 14 drinks per week in women, over a period of at least 2 years.2

The exact pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis is incompletely understood, but alcohol is primarily metabolized by the liver, and damage likely occurs during metabolism of the ingested alcohol. AST elevations tend to be higher than ALT elevations; the reason is ascribed to hepatic deficiency of pyridoxal 5´-phosphate, a cofactor of the enzymatic activity of ALT, which leads to a lesser increase in ALT than in AST.

Alcoholic liver disease can be difficult to diagnose, as many people are initially reluctant to fully disclose how much they drink, but it should be suspected when the ratio of AST to ALT is 2 or greater.

In a classic study, a ratio greater than 2 was found in 70% of patients with alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, compared with 26% of patients with postnecrotic cirrhosis, 8% with chronic hepatitis, 4% with viral hepatitis, and none with obstructive jaundice.3 Importantly, the disorder is often correctable if the patient is able to remain abstinent from alcohol over time.

A detailed medication history is important and should focus especially on recently added medications, dosage changes, medication overuse, and use of nonprescription drugs and herbal supplements. Common medications that affect liver enzyme levels include statins, which cause hepatic dysfunction primarily during the first 3 months of therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptic drugs, antibiotics, anabolic steroids, and acetaminophen (Table 2).1 Use of illicit drugs and herbal remedies should be discussed, as they may cause toxin-mediated hepatitis.

Although inflammation from drug toxicity will resolve if the offending agent is discontinued, complete recovery may take weeks to months.4

A pertinent social history includes exposure to environmental hepatotoxins such as amatoxin (contained in some wild mushrooms) and occupational hazards (eg, vinyl chloride). Risk factors for viral hepatitis should be evaluated, including intravenous drug use, blood transfusions, unprotected sexual contact, organ transplant, perinatal transmission, and a history of work in healthcare facilities or travel to regions in which hepatitis A or E is endemic.

The medical and family history should include details of associated conditions, such as:

- Right heart failure (a cause of congestive hepatopathy)

- Metabolic syndrome (associated with fatty liver disease)

- Inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Early-onset emphysema and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

The physical examination should be thorough, with emphasis on the abdomen, and search for stigmata of advanced liver disease such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, edema, spider angiomata, jaundice, and asterixis. Any patient with evidence of chronic liver disease should be referred to a subspecialist for further evaluation.

Further diagnostic workup

Abnormal liver enzyme findings or physical examination findings should direct the subsequent diagnostic workup with laboratory testing and imaging.5

For cholestasis. If laboratory data are consistent with cholestasis or abnormal bile flow, it should be further characterized as extrahepatic or intrahepatic. Common causes of extrahepatic cholestasis include biliary tree obstruction due to stones or malignancy, often visualized as intraductal biliary dilation on ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant. Common causes of intrahepatic cholestasis include viral and alcoholic hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, certain drugs and toxins such as alkylated steroids and herbal medications, infiltrative diseases such as amyloid, sarcoid, lymphoma, and tuberculosis, and primary biliary cholangitis.

Abnormal findings on ultrasonography should be further pursued with advanced imaging, ie, computed tomography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The confirmation of a lesion on imaging is often followed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in an attempt to obtain biopsy samples, remove obstructions, and place therapeutic stents. In instances when endoscopic attempts fail to relieve the obstruction, surgical referral may be appropriate.

For nonhepatobiliary problems. Depending on clinical presentation, it may also be important to consider nonhepatobiliary causes of elevated liver enzymes.

Alkaline phosphatase is found in many other tissue types, including bone, kidney, and the placenta, and can be elevated during pregnancy, adolescence, and even after fatty meals due to intestinal release.6 After screening for the aforementioned physiologic conditions, isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase should be further evaluated by obtaining GGT or 5-nucleotidase levels, which are more specifically of hepatic origin. If these levels are within normal limits, further evaluation for conditions of bone growth and cellular turnover such as Paget disease, hyperparathyroidism, and malignancy should be considered. Specifically, Stauffer syndrome should be considered when there is a paraneoplastic rise in the alkaline phosphatase level in the setting of renal cell carcinoma without liver metastases.

AST and ALT levels may also be elevated in clinical situations and syndromes unrelated to liver disease. Rhabdomyolysis, for instance, may be associated with elevations of AST in more than 90% of cases, and ALT in more than 75%.7 Markers of muscle injury including serum creatine kinase should be obtained in the setting of heat stroke, muscle weakness, strenuous activity, or seizures, as related elevations in AST and ALT may not always be clinically indicative of liver injury.

Given the many conditions that may cause elevated liver enzymes, evaluation and treatment should focus on identifying and removing offending agents and targeting the underlying process with appropriate medical therapy.

FATTY LIVER

With rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes on the rise in the general population, identifying and treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) require increased awareness and close coordination between primary care providers and subspecialists.

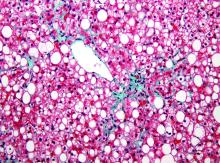

According to current estimates, up to one-third of the US population (100 million people) may have NAFLD, and 1% to 3% of the population (4–6 million people) likely have NASH, defined as steatosis with inflammation. Development of NASH places patients at a significantly higher risk of fibrosis, hepatocellular injury, and cancer.8

NAFLD is more common in men than in women. It is present in around 80% to 90% of obese adults, two-thirds of adults with type 2 diabetes, and many people with hyperlipidemia. It is also becoming more common in children, with 40% to 70% of obese children likely having some element of NAFLD.

Diagnosis of fatty liver

Although liver enzymes are more likely to be abnormal in individuals with NAFLD, many individuals with underlying NAFLD may have normal laboratory evaluations. ALT may be elevated in only up to 20% of cases and does not likely correlate with the level of underlying liver damage, although increasing GGT may serve as a marker of fibrosis over time.9–11 In contrast to alcohol injury, however, the AST-ALT ratio is usually less than 1.0.

Noninvasive tools for diagnosing NAFLD include the NAFLD fibrosis score, which incorporates age, hyperglycemia, body mass index, platelet count, albumin level, and AST-ALT ratio. This and related scoring algorithms may be useful in differentiating patients with minimal fibrosis from those with advanced fibrosis.12,13

Ultrasonography is a first-line diagnostic test for steatosis, although it may demonstrate fatty infiltration only around 60% of the time. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive, but costlier. Transient elastography (FibroScan; Echosens, Paris, France) has become more popular and has been shown to correlate with findings on liver biopsy in diagnosing or excluding advanced liver fibrosis.14,15

The gold standard for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH is identifying fat-laden hepatocytes or portal inflammation on biopsy; however, biopsy is generally reserved for cases in which the diagnosis remains uncertain.

Behavioral treatment

The primary treatment for NAFLD consists of behavioral modification including weight loss, exercise, and adherence to a low-fat diet, in addition to tight glycemic control and treatment of any underlying lipid abnormalities. Studies have shown that a reduction of 7% to 10% of body weight is associated with a decrease in the inflammation of NAFLD, though no strict guidelines have been established.16

Given the prevalence of NAFLD and the need for longitudinal treatment, primary care physicians will play a significant role in long-term monitoring and management of patients with fatty liver disease.

OTHER DISORDERS OF LIVER FUNCTION

Hereditary hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common inherited liver disorder in adults of European descent,17 and can be effectively treated if discovered early. But its clinical diagnosis can be challenging, as many patients have no symptoms at presentation despite abnormal liver enzyme levels. Early symptoms may include severe fatigue, arthralgias, and, in men, impotence, before the appearance of the classic triad of “bronze diabetes” with cirrhosis, diabetes, and darkening of the skin.18

If hemochromatosis is suspected, laboratory tests should include a calculation of percent transferrin saturation, with saturation greater than 45% warranting serum ferritin measurement to evaluate for iron overload (ferritin > 200–300 ng/mL in men, > 150–200 ng/mL in women).19 If iron overload is confirmed, referral to a gastroenterologist is recommended.

Genetic evaluation is often pursued, but patients may ultimately require liver biopsy regardless of the findings, as some patients homozygous for the HFE mutation C282Y may not have clinical hemochromatosis, whereas others with hereditary hemochromatosis may not have the HFE mutation.

Therapeutic phlebotomy is the treatment of choice, and most patients tolerate it well.

Chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are common in the United States, with HBV affecting more than 1 million people and HCV affecting an estimated 3.5 million.

Chronic HCV infection. Direct-acting antiviral drugs have revolutionized HCV treatment and have led to a sustained viral response and presumed cure at 12 weeks in more than 95% of cases across all HCV genotypes.20 Given the recent development of effective and well-tolerated treatments, primary care physicians have assumed a pivotal role in screening for HCV.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America21 recommend screening for HCV in people who have risk factors for it, ie:

- HCV exposure

- HIV infection

- Behavioral or environmental risks for contracting the virus such as intravenous drug use or incarceration

- Birth between 1945 and 1965 (one-time testing).

If HCV antibody screening is positive, HCV RNA should be obtained to quantify the viral load and confirm active infection, and genotype testing should be performed to guide treatment. Among the 6 most common HCV genotypes, genotype 1 is the most common in North America, accounting for over 70% of cases in the United States.

Although recommendations and therapies are constantly evolving, the selection of a treatment regimen and the duration of therapy are determined by viral genotype, history of prior treatment, stage of liver fibrosis, potential drug interactions, and frequently, medication cost and insurance coverage.

HBV infection. The treatment for acute HBV infection is generally supportive, though viral suppression with tenofovir or entecavir may be required for those who develop coagulopathy, bilirubinemia, or liver failure. Treatment of chronic HBV infection may not be required and is generally considered for those with elevated ALT, high viral load, or evidence of liver fibrosis on noninvasive measurements such as transient elastography.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune causes of liver enzyme elevations should also be considered during initial screening. Positive antinuclear antibody and positive antismooth muscle antibody tests are common in cases of autoimmune hepatitis.22 Autoimmune hepatitis affects women more often than men, with a ratio of 4:1. The peaks of incidence occur during adolescence and between ages 30 and 45.23

Primary biliary cholangitis

Additionally, an elevated alkaline phosphatase level should raise concern for underlying primary biliary cholangitis (formerly called primary biliary cirrhosis), an autoimmune disorder that affects the small and medium intrahepatic bile ducts. Diagnosis of primary biliary cholangitis can be assisted by a positive test for antimitochondrial antibody, present in almost 90% of patients.24

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Elevated alkaline phosphatase is also the hallmark of primary sclerosing cholangitis, which is associated with inflammatory bowel disease.25 Primary sclerosing cholangitis is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, which are visualized on MRCP and confirmed by biopsy if needed.

REFERRAL

Subspecialty referral should be considered if the cause remains ambiguous or unknown, if there is concern for a rare hepatic disorder such as an autoimmune condition, Wilson disease, or alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, or if there is evidence of advanced or chronic liver disease.

Primary care physicians are at the forefront of detecting and diagnosing liver disease, and close coordination with subspecialists will remain crucial in delivering patient care.

- Aragon G, Younossi ZM. When and how to evaluate mildly elevated liver enzymes in apparently healthy patients. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77(3):195–204. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.09064

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al; American Gastroenterological Association; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(7):1592–1609. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.001

- Cohen JA, Kaplan MM. The SGOT/SGPT ratio—an indicator of alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci 1979; 24(11):835–838. pmid:520102

- Kaplan MM. Alanine aminotransferase levels: what’s normal? Ann Intern Med 2002; 137(1):49-51. pmid:12093245

- Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(17):1266–1271. doi:10.1056/NEJM200004273421707

- Sharma U, Pal D, Prasad R. Alkaline phosphatase: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem 2014; 29(3):269–278. doi:10.1007/s12291-013-0408-y

- Weibrecht K, Dayno M, Darling C, Bird SB. Liver aminotransferases are elevated with rhabdomyolysis in the absence of significant liver injury. J Med Toxicol 2010; 6(3):294–300. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0075-9

- Bellentani S, Scaglioni F, Marino M, Bedogni G. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis 2010; 28(1):155–161. doi:10.1159/000282080

- Adams LA, Feldstein AE. Non-invasive diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Dig Dis 2011; 12(1):10–16. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00471.x

- Fracanzani AL, Valenti L, Bugianesi E, et al. Risk of severe liver disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with normal aminotransferase levels: a role for insulin resistance and diabetes. Hepatology 2008; 48(3):792–798. doi:10.1002/hep.22429

- Tahan V, Canbakan B, Balci H, et al. Serum gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase distinguishes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease at high risk. Hepatogastroenterolgoy 2008; 55(85):1433-1438. pmid:18795706

- McPherson S, Stewart S, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2010; 59(9):1265–1269. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.216077

- Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007; 45(4):846–854. doi:10.1002/hep.21496

- Petta S, Vanni E, Bugianesi E, et al. The combination of liver stiffness measurement and NAFLD fibrosis score improves the noninvasive diagnostic accuracy for severe liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2015; 35(5):1566–1573. doi:10.1111/liv.12584

- Hashemi SA, Alavian SM, Gholami-Fesharaki M. Assessment of transient elastography (FibroScan) for diagnosis of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caspian J Intern Med 2016; 7(4):242–252. pmid:27999641

- Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51(1):121–129. doi:10.1002/hep.23276

- Adams PH, Reboussin DM, Barton JC, et al. Hemochromatosis and iron-overload screening in a racially diverse population. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(17):1769-1778. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041534

- Brissot P, de Bels F. Current approaches to the management of hemochromatosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006; 2006(1):36–41. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.36

- Bacon BR, Adams PC, Kowdley KV, Powell LW, Tavill AS; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of hemochromatosis: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2011; 54(1):328–343. doi:10.1002/hep.24330

- Weiler N, Zeuzem S, Welker MW. Concise review: interferon-free treatment of hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis and liver graft infection. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(41):9044–9056. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9044

- American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2010; 51(6):2193–2213. doi:10.1002/hep.23584

- Liberal R, Krawitt EL, Vierling JM, Manns MP, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Cutting edge issues in autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun 2016; 75:6–19. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2016.07.005

- Mousa HS, Carbone M, Malinverno F, Ronca V, Gershwin ME, Invernizzi P. Novel therapeutics for primary biliary cholangitis: Toward a disease-stage-based approach. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15(9):870–876. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.003

- de Vries AB, Janse M, Blokzijl H, Weersma RK. Distinctive inflammatory bowel disease phenotype in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(6):1956–1971. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1956

Elevated levels of circulating enzymes that are frequently of hepatic origin (aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase) and bilirubin in the absence of symptoms are common in clinical practice. A dogmatic but true statement holds that there are no trivial elevations in these substances. All persistent elevations of liver enzymes need a methodical evaluation and an appropriate working diagnosis.1

Here, we outline a framework for the workup and treatment of common causes of liver enzyme elevations.

PATTERN OF ELEVATION: CHOLESTATIC OR HEPATOCELLULAR

Based on the pattern of elevation, causes of elevated liver enzymes can be sorted into disorders of cholestasis and disorders of hepatocellular injury (Table 1).1

Cholestatic disorders tend to cause elevations in alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT).

Hepatocellular injury raises levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

HOW SHOULD ABNORMAL RESULTS BE EVALUATED?

When approaching liver enzyme elevations, the clinician should develop a working differential diagnosis based on the medical and social history and physical examination.

Think about alcohol, drugs, and fat

The most common causes of liver enzyme elevation are alcohol toxicity, medication overdose, and fatty liver disease.

Alcohol intake should be ascertained. “Significant” consumption is defined as more than 21 drinks per week in men or more than 14 drinks per week in women, over a period of at least 2 years.2

The exact pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis is incompletely understood, but alcohol is primarily metabolized by the liver, and damage likely occurs during metabolism of the ingested alcohol. AST elevations tend to be higher than ALT elevations; the reason is ascribed to hepatic deficiency of pyridoxal 5´-phosphate, a cofactor of the enzymatic activity of ALT, which leads to a lesser increase in ALT than in AST.

Alcoholic liver disease can be difficult to diagnose, as many people are initially reluctant to fully disclose how much they drink, but it should be suspected when the ratio of AST to ALT is 2 or greater.

In a classic study, a ratio greater than 2 was found in 70% of patients with alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, compared with 26% of patients with postnecrotic cirrhosis, 8% with chronic hepatitis, 4% with viral hepatitis, and none with obstructive jaundice.3 Importantly, the disorder is often correctable if the patient is able to remain abstinent from alcohol over time.

A detailed medication history is important and should focus especially on recently added medications, dosage changes, medication overuse, and use of nonprescription drugs and herbal supplements. Common medications that affect liver enzyme levels include statins, which cause hepatic dysfunction primarily during the first 3 months of therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptic drugs, antibiotics, anabolic steroids, and acetaminophen (Table 2).1 Use of illicit drugs and herbal remedies should be discussed, as they may cause toxin-mediated hepatitis.

Although inflammation from drug toxicity will resolve if the offending agent is discontinued, complete recovery may take weeks to months.4

A pertinent social history includes exposure to environmental hepatotoxins such as amatoxin (contained in some wild mushrooms) and occupational hazards (eg, vinyl chloride). Risk factors for viral hepatitis should be evaluated, including intravenous drug use, blood transfusions, unprotected sexual contact, organ transplant, perinatal transmission, and a history of work in healthcare facilities or travel to regions in which hepatitis A or E is endemic.

The medical and family history should include details of associated conditions, such as:

- Right heart failure (a cause of congestive hepatopathy)

- Metabolic syndrome (associated with fatty liver disease)

- Inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Early-onset emphysema and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

The physical examination should be thorough, with emphasis on the abdomen, and search for stigmata of advanced liver disease such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, edema, spider angiomata, jaundice, and asterixis. Any patient with evidence of chronic liver disease should be referred to a subspecialist for further evaluation.

Further diagnostic workup

Abnormal liver enzyme findings or physical examination findings should direct the subsequent diagnostic workup with laboratory testing and imaging.5

For cholestasis. If laboratory data are consistent with cholestasis or abnormal bile flow, it should be further characterized as extrahepatic or intrahepatic. Common causes of extrahepatic cholestasis include biliary tree obstruction due to stones or malignancy, often visualized as intraductal biliary dilation on ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant. Common causes of intrahepatic cholestasis include viral and alcoholic hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, certain drugs and toxins such as alkylated steroids and herbal medications, infiltrative diseases such as amyloid, sarcoid, lymphoma, and tuberculosis, and primary biliary cholangitis.

Abnormal findings on ultrasonography should be further pursued with advanced imaging, ie, computed tomography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The confirmation of a lesion on imaging is often followed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in an attempt to obtain biopsy samples, remove obstructions, and place therapeutic stents. In instances when endoscopic attempts fail to relieve the obstruction, surgical referral may be appropriate.

For nonhepatobiliary problems. Depending on clinical presentation, it may also be important to consider nonhepatobiliary causes of elevated liver enzymes.

Alkaline phosphatase is found in many other tissue types, including bone, kidney, and the placenta, and can be elevated during pregnancy, adolescence, and even after fatty meals due to intestinal release.6 After screening for the aforementioned physiologic conditions, isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase should be further evaluated by obtaining GGT or 5-nucleotidase levels, which are more specifically of hepatic origin. If these levels are within normal limits, further evaluation for conditions of bone growth and cellular turnover such as Paget disease, hyperparathyroidism, and malignancy should be considered. Specifically, Stauffer syndrome should be considered when there is a paraneoplastic rise in the alkaline phosphatase level in the setting of renal cell carcinoma without liver metastases.

AST and ALT levels may also be elevated in clinical situations and syndromes unrelated to liver disease. Rhabdomyolysis, for instance, may be associated with elevations of AST in more than 90% of cases, and ALT in more than 75%.7 Markers of muscle injury including serum creatine kinase should be obtained in the setting of heat stroke, muscle weakness, strenuous activity, or seizures, as related elevations in AST and ALT may not always be clinically indicative of liver injury.

Given the many conditions that may cause elevated liver enzymes, evaluation and treatment should focus on identifying and removing offending agents and targeting the underlying process with appropriate medical therapy.

FATTY LIVER

With rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes on the rise in the general population, identifying and treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) require increased awareness and close coordination between primary care providers and subspecialists.

According to current estimates, up to one-third of the US population (100 million people) may have NAFLD, and 1% to 3% of the population (4–6 million people) likely have NASH, defined as steatosis with inflammation. Development of NASH places patients at a significantly higher risk of fibrosis, hepatocellular injury, and cancer.8

NAFLD is more common in men than in women. It is present in around 80% to 90% of obese adults, two-thirds of adults with type 2 diabetes, and many people with hyperlipidemia. It is also becoming more common in children, with 40% to 70% of obese children likely having some element of NAFLD.

Diagnosis of fatty liver

Although liver enzymes are more likely to be abnormal in individuals with NAFLD, many individuals with underlying NAFLD may have normal laboratory evaluations. ALT may be elevated in only up to 20% of cases and does not likely correlate with the level of underlying liver damage, although increasing GGT may serve as a marker of fibrosis over time.9–11 In contrast to alcohol injury, however, the AST-ALT ratio is usually less than 1.0.

Noninvasive tools for diagnosing NAFLD include the NAFLD fibrosis score, which incorporates age, hyperglycemia, body mass index, platelet count, albumin level, and AST-ALT ratio. This and related scoring algorithms may be useful in differentiating patients with minimal fibrosis from those with advanced fibrosis.12,13

Ultrasonography is a first-line diagnostic test for steatosis, although it may demonstrate fatty infiltration only around 60% of the time. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive, but costlier. Transient elastography (FibroScan; Echosens, Paris, France) has become more popular and has been shown to correlate with findings on liver biopsy in diagnosing or excluding advanced liver fibrosis.14,15

The gold standard for diagnosing NAFLD and NASH is identifying fat-laden hepatocytes or portal inflammation on biopsy; however, biopsy is generally reserved for cases in which the diagnosis remains uncertain.

Behavioral treatment

The primary treatment for NAFLD consists of behavioral modification including weight loss, exercise, and adherence to a low-fat diet, in addition to tight glycemic control and treatment of any underlying lipid abnormalities. Studies have shown that a reduction of 7% to 10% of body weight is associated with a decrease in the inflammation of NAFLD, though no strict guidelines have been established.16

Given the prevalence of NAFLD and the need for longitudinal treatment, primary care physicians will play a significant role in long-term monitoring and management of patients with fatty liver disease.

OTHER DISORDERS OF LIVER FUNCTION

Hereditary hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common inherited liver disorder in adults of European descent,17 and can be effectively treated if discovered early. But its clinical diagnosis can be challenging, as many patients have no symptoms at presentation despite abnormal liver enzyme levels. Early symptoms may include severe fatigue, arthralgias, and, in men, impotence, before the appearance of the classic triad of “bronze diabetes” with cirrhosis, diabetes, and darkening of the skin.18

If hemochromatosis is suspected, laboratory tests should include a calculation of percent transferrin saturation, with saturation greater than 45% warranting serum ferritin measurement to evaluate for iron overload (ferritin > 200–300 ng/mL in men, > 150–200 ng/mL in women).19 If iron overload is confirmed, referral to a gastroenterologist is recommended.

Genetic evaluation is often pursued, but patients may ultimately require liver biopsy regardless of the findings, as some patients homozygous for the HFE mutation C282Y may not have clinical hemochromatosis, whereas others with hereditary hemochromatosis may not have the HFE mutation.

Therapeutic phlebotomy is the treatment of choice, and most patients tolerate it well.

Chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are common in the United States, with HBV affecting more than 1 million people and HCV affecting an estimated 3.5 million.

Chronic HCV infection. Direct-acting antiviral drugs have revolutionized HCV treatment and have led to a sustained viral response and presumed cure at 12 weeks in more than 95% of cases across all HCV genotypes.20 Given the recent development of effective and well-tolerated treatments, primary care physicians have assumed a pivotal role in screening for HCV.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America21 recommend screening for HCV in people who have risk factors for it, ie:

- HCV exposure

- HIV infection

- Behavioral or environmental risks for contracting the virus such as intravenous drug use or incarceration

- Birth between 1945 and 1965 (one-time testing).

If HCV antibody screening is positive, HCV RNA should be obtained to quantify the viral load and confirm active infection, and genotype testing should be performed to guide treatment. Among the 6 most common HCV genotypes, genotype 1 is the most common in North America, accounting for over 70% of cases in the United States.

Although recommendations and therapies are constantly evolving, the selection of a treatment regimen and the duration of therapy are determined by viral genotype, history of prior treatment, stage of liver fibrosis, potential drug interactions, and frequently, medication cost and insurance coverage.

HBV infection. The treatment for acute HBV infection is generally supportive, though viral suppression with tenofovir or entecavir may be required for those who develop coagulopathy, bilirubinemia, or liver failure. Treatment of chronic HBV infection may not be required and is generally considered for those with elevated ALT, high viral load, or evidence of liver fibrosis on noninvasive measurements such as transient elastography.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune causes of liver enzyme elevations should also be considered during initial screening. Positive antinuclear antibody and positive antismooth muscle antibody tests are common in cases of autoimmune hepatitis.22 Autoimmune hepatitis affects women more often than men, with a ratio of 4:1. The peaks of incidence occur during adolescence and between ages 30 and 45.23

Primary biliary cholangitis

Additionally, an elevated alkaline phosphatase level should raise concern for underlying primary biliary cholangitis (formerly called primary biliary cirrhosis), an autoimmune disorder that affects the small and medium intrahepatic bile ducts. Diagnosis of primary biliary cholangitis can be assisted by a positive test for antimitochondrial antibody, present in almost 90% of patients.24

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Elevated alkaline phosphatase is also the hallmark of primary sclerosing cholangitis, which is associated with inflammatory bowel disease.25 Primary sclerosing cholangitis is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, which are visualized on MRCP and confirmed by biopsy if needed.

REFERRAL

Subspecialty referral should be considered if the cause remains ambiguous or unknown, if there is concern for a rare hepatic disorder such as an autoimmune condition, Wilson disease, or alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, or if there is evidence of advanced or chronic liver disease.

Primary care physicians are at the forefront of detecting and diagnosing liver disease, and close coordination with subspecialists will remain crucial in delivering patient care.

Elevated levels of circulating enzymes that are frequently of hepatic origin (aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase) and bilirubin in the absence of symptoms are common in clinical practice. A dogmatic but true statement holds that there are no trivial elevations in these substances. All persistent elevations of liver enzymes need a methodical evaluation and an appropriate working diagnosis.1

Here, we outline a framework for the workup and treatment of common causes of liver enzyme elevations.

PATTERN OF ELEVATION: CHOLESTATIC OR HEPATOCELLULAR

Based on the pattern of elevation, causes of elevated liver enzymes can be sorted into disorders of cholestasis and disorders of hepatocellular injury (Table 1).1

Cholestatic disorders tend to cause elevations in alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT).

Hepatocellular injury raises levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

HOW SHOULD ABNORMAL RESULTS BE EVALUATED?

When approaching liver enzyme elevations, the clinician should develop a working differential diagnosis based on the medical and social history and physical examination.

Think about alcohol, drugs, and fat

The most common causes of liver enzyme elevation are alcohol toxicity, medication overdose, and fatty liver disease.

Alcohol intake should be ascertained. “Significant” consumption is defined as more than 21 drinks per week in men or more than 14 drinks per week in women, over a period of at least 2 years.2

The exact pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis is incompletely understood, but alcohol is primarily metabolized by the liver, and damage likely occurs during metabolism of the ingested alcohol. AST elevations tend to be higher than ALT elevations; the reason is ascribed to hepatic deficiency of pyridoxal 5´-phosphate, a cofactor of the enzymatic activity of ALT, which leads to a lesser increase in ALT than in AST.

Alcoholic liver disease can be difficult to diagnose, as many people are initially reluctant to fully disclose how much they drink, but it should be suspected when the ratio of AST to ALT is 2 or greater.

In a classic study, a ratio greater than 2 was found in 70% of patients with alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, compared with 26% of patients with postnecrotic cirrhosis, 8% with chronic hepatitis, 4% with viral hepatitis, and none with obstructive jaundice.3 Importantly, the disorder is often correctable if the patient is able to remain abstinent from alcohol over time.

A detailed medication history is important and should focus especially on recently added medications, dosage changes, medication overuse, and use of nonprescription drugs and herbal supplements. Common medications that affect liver enzyme levels include statins, which cause hepatic dysfunction primarily during the first 3 months of therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiepileptic drugs, antibiotics, anabolic steroids, and acetaminophen (Table 2).1 Use of illicit drugs and herbal remedies should be discussed, as they may cause toxin-mediated hepatitis.

Although inflammation from drug toxicity will resolve if the offending agent is discontinued, complete recovery may take weeks to months.4

A pertinent social history includes exposure to environmental hepatotoxins such as amatoxin (contained in some wild mushrooms) and occupational hazards (eg, vinyl chloride). Risk factors for viral hepatitis should be evaluated, including intravenous drug use, blood transfusions, unprotected sexual contact, organ transplant, perinatal transmission, and a history of work in healthcare facilities or travel to regions in which hepatitis A or E is endemic.

The medical and family history should include details of associated conditions, such as:

- Right heart failure (a cause of congestive hepatopathy)

- Metabolic syndrome (associated with fatty liver disease)

- Inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Early-onset emphysema and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

The physical examination should be thorough, with emphasis on the abdomen, and search for stigmata of advanced liver disease such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, edema, spider angiomata, jaundice, and asterixis. Any patient with evidence of chronic liver disease should be referred to a subspecialist for further evaluation.

Further diagnostic workup

Abnormal liver enzyme findings or physical examination findings should direct the subsequent diagnostic workup with laboratory testing and imaging.5

For cholestasis. If laboratory data are consistent with cholestasis or abnormal bile flow, it should be further characterized as extrahepatic or intrahepatic. Common causes of extrahepatic cholestasis include biliary tree obstruction due to stones or malignancy, often visualized as intraductal biliary dilation on ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant. Common causes of intrahepatic cholestasis include viral and alcoholic hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, certain drugs and toxins such as alkylated steroids and herbal medications, infiltrative diseases such as amyloid, sarcoid, lymphoma, and tuberculosis, and primary biliary cholangitis.

Abnormal findings on ultrasonography should be further pursued with advanced imaging, ie, computed tomography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The confirmation of a lesion on imaging is often followed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in an attempt to obtain biopsy samples, remove obstructions, and place therapeutic stents. In instances when endoscopic attempts fail to relieve the obstruction, surgical referral may be appropriate.

For nonhepatobiliary problems. Depending on clinical presentation, it may also be important to consider nonhepatobiliary causes of elevated liver enzymes.