User login

Germline mutations linked to hematologic malignancies

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

A new study suggests mutations in the gene DDX41 occur in families where hematologic malignancies are common.

Previous research showed that both germline and acquired DDX41 mutations occur in families with multiple cases of late-onset myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The new study, published in Blood, has linked germline mutations in DDX41 to chronic myeloid leukemia and lymphomas as well.

“This is the first gene identified in families with lymphoma and represents a major breakthrough for the field,” said study author Hamish Scott, PhD, of the University of Adelaide in South Australia.

“Researchers are recognizing now that genetic predisposition to blood cancer is more common than previously thought, and our study shows the importance of taking a thorough family history at diagnosis.”

To conduct this study, Dr Scott and his colleagues screened 2 cohorts of families with a range of hematologic disorders (malignant and non-malignant). One cohort included 240 individuals from 93 families in Australia. The other included 246 individuals from 198 families in the US.

In all, 9 of the families (3%) had germline DDX41 mutations.

Three families carried the recurrent p.D140Gfs*2 mutation, which was linked to AML.

One family carried a germline mutation—p.R525H, c.1574G.A—that was previously described only as a somatic mutation at the time of progression to MDS or AML. In the current study, the mutation was again linked to MDS and AML.

Five families carried novel DDX41 mutations.

One of these mutations was a germline substitution—c.435-2_435-1delAGinsCA—that was linked to MDS in 1 family.

Two families had a missense start-loss substitution—c.3G.A, p.M1I—that was linked to MDS, AML, chronic myeloid leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

One family had a DDX41 missense variant—c.490C.T, p.R164W. This was linked to Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including 3 cases of follicular lymphoma). There was a possible link to multiple myeloma as well, but the diagnosis could not be confirmed.

And 1 family had a missense mutation in the helicase domain—p.G530D—that was linked to AML.

“DDX41 is a new type of cancer predisposition gene, and we are still investigating its function,” Dr Scott noted.

“But it appears to have dual roles in regulating the correct expression of genes in the cell and also enabling the immune system to respond to threats such as bacteria and viruses, as well as the development of cancer cells. Immunotherapy is a promising approach for cancer treatment, and our research to understand the function of DDX41 will help design better therapies.” ![]()

Study results support screening of childhood HL survivors

A new study indicates that early screening can reduce the risk of death from breast cancer among female survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received chest radiation.

Researchers found evidence to suggest that starting mammograms at age 25 can reduce the risk of breast cancer death among these patients, but using MRI can reduce the risk further.

Unfortunately, both methods come with a risk of false-positive results.

David Hodgson, MD, of the University of Toronto in Canada, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Dr Hodgson estimates there are thousands of HL survivors in North America treated throughout the 1990s and later who received chest radiation and are unaware they are at risk of breast cancer and eligible for early screening.

“Many of these are women who received radiotherapy to more normal tissue or at higher doses than are used currently,” he said. “But even for more recently treated patients, screening should reduce the risk of breast cancer death.”

For this study, Dr Hodgson and his colleagues gathered published information from dozens of studies about the risk of developing breast cancer in childhood HL survivors, the accuracy of different forms of breast cancer screening, and the rates at which women agree to be screened when asked.

Using mathematical models, the researchers used these data to quantify the effectiveness of starting screening early—at age 25.

The team found that, using mammography, about 260 survivors of childhood HL would need to be invited to have early breast cancer screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death.

However, the use of MRI for screening improved the effectiveness considerably. It reduced the number of women needing screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death to less than 80.

For HL survivors treated at age 15, the absolute risk of breast cancer mortality by age 75 was predicted to decrease from 16.65% with no early screening to 16.28% with annual mammography, 15.40% with annual MRI, 15.38% with same-day annual mammography and MRI, and 15.37% with alternating mammography and MRI every 6 months.

Dr Hodgson cautioned that there is a risk of false-positive screening results, particuarly with MRI, given that the method can detect many changes in breast tissue, most of which are not cancer.

The data suggested that, from age 25 to 75, at least one false-positive result would occur in 48% of women screened with mammography, 74% screened with MRI alone, and 79% screened with both methods.

The number of false-positives per 1000 screens would be 29.98 with mammography, 71.71 with MRI, and 99.52 with either same-day mammography and MRI or alternating mammography and MRI.

“So this is important for patients to know and for physicians to counsel patients about because it’s stressful for a patient to be called back about suspicious findings,” Dr Hodgson said. ![]()

A new study indicates that early screening can reduce the risk of death from breast cancer among female survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received chest radiation.

Researchers found evidence to suggest that starting mammograms at age 25 can reduce the risk of breast cancer death among these patients, but using MRI can reduce the risk further.

Unfortunately, both methods come with a risk of false-positive results.

David Hodgson, MD, of the University of Toronto in Canada, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Dr Hodgson estimates there are thousands of HL survivors in North America treated throughout the 1990s and later who received chest radiation and are unaware they are at risk of breast cancer and eligible for early screening.

“Many of these are women who received radiotherapy to more normal tissue or at higher doses than are used currently,” he said. “But even for more recently treated patients, screening should reduce the risk of breast cancer death.”

For this study, Dr Hodgson and his colleagues gathered published information from dozens of studies about the risk of developing breast cancer in childhood HL survivors, the accuracy of different forms of breast cancer screening, and the rates at which women agree to be screened when asked.

Using mathematical models, the researchers used these data to quantify the effectiveness of starting screening early—at age 25.

The team found that, using mammography, about 260 survivors of childhood HL would need to be invited to have early breast cancer screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death.

However, the use of MRI for screening improved the effectiveness considerably. It reduced the number of women needing screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death to less than 80.

For HL survivors treated at age 15, the absolute risk of breast cancer mortality by age 75 was predicted to decrease from 16.65% with no early screening to 16.28% with annual mammography, 15.40% with annual MRI, 15.38% with same-day annual mammography and MRI, and 15.37% with alternating mammography and MRI every 6 months.

Dr Hodgson cautioned that there is a risk of false-positive screening results, particuarly with MRI, given that the method can detect many changes in breast tissue, most of which are not cancer.

The data suggested that, from age 25 to 75, at least one false-positive result would occur in 48% of women screened with mammography, 74% screened with MRI alone, and 79% screened with both methods.

The number of false-positives per 1000 screens would be 29.98 with mammography, 71.71 with MRI, and 99.52 with either same-day mammography and MRI or alternating mammography and MRI.

“So this is important for patients to know and for physicians to counsel patients about because it’s stressful for a patient to be called back about suspicious findings,” Dr Hodgson said. ![]()

A new study indicates that early screening can reduce the risk of death from breast cancer among female survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received chest radiation.

Researchers found evidence to suggest that starting mammograms at age 25 can reduce the risk of breast cancer death among these patients, but using MRI can reduce the risk further.

Unfortunately, both methods come with a risk of false-positive results.

David Hodgson, MD, of the University of Toronto in Canada, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Dr Hodgson estimates there are thousands of HL survivors in North America treated throughout the 1990s and later who received chest radiation and are unaware they are at risk of breast cancer and eligible for early screening.

“Many of these are women who received radiotherapy to more normal tissue or at higher doses than are used currently,” he said. “But even for more recently treated patients, screening should reduce the risk of breast cancer death.”

For this study, Dr Hodgson and his colleagues gathered published information from dozens of studies about the risk of developing breast cancer in childhood HL survivors, the accuracy of different forms of breast cancer screening, and the rates at which women agree to be screened when asked.

Using mathematical models, the researchers used these data to quantify the effectiveness of starting screening early—at age 25.

The team found that, using mammography, about 260 survivors of childhood HL would need to be invited to have early breast cancer screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death.

However, the use of MRI for screening improved the effectiveness considerably. It reduced the number of women needing screening to prevent 1 breast cancer death to less than 80.

For HL survivors treated at age 15, the absolute risk of breast cancer mortality by age 75 was predicted to decrease from 16.65% with no early screening to 16.28% with annual mammography, 15.40% with annual MRI, 15.38% with same-day annual mammography and MRI, and 15.37% with alternating mammography and MRI every 6 months.

Dr Hodgson cautioned that there is a risk of false-positive screening results, particuarly with MRI, given that the method can detect many changes in breast tissue, most of which are not cancer.

The data suggested that, from age 25 to 75, at least one false-positive result would occur in 48% of women screened with mammography, 74% screened with MRI alone, and 79% screened with both methods.

The number of false-positives per 1000 screens would be 29.98 with mammography, 71.71 with MRI, and 99.52 with either same-day mammography and MRI or alternating mammography and MRI.

“So this is important for patients to know and for physicians to counsel patients about because it’s stressful for a patient to be called back about suspicious findings,” Dr Hodgson said. ![]()

AAs have lower rate of most blood cancers than NHWs

receiving treatment

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new report suggests African Americans (AAs) have significantly lower rates of most hematologic malignancies than non-Hispanic white (NHW) individuals in the US.

AAs of both sexes had significantly lower rates of leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) than NHWs, but the rate of myeloma was significantly higher among AAs.

The death rates for these malignancies followed the same patterns, with the exception of HL. There was no significant difference in HL mortality between AAs and NHWs of either sex.

These findings can be found in the report, “Cancer Statistics for African Americans, 2016,” appearing in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

To compile this report, the researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries.

Incidence

For part of the report, the researchers compared the incidence of cancers between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

Among females, the incidence of leukemia was 8.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 10.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). Among males, the incidence was 13.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 17.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of HL in females was 2.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of HL in males was 3.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 3.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of NHL in females was 12.0 per 100,000 in AAs and 16.6 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of NHL in males was 17.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 24.1 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of myeloma in females was 11.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of myeloma in males was 14.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 7.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

Mortality

The researchers also compared cancer mortality between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

The death rate for female leukemia patients was 4.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male leukemia patients was 8.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 9.9 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female HL patients was 0.3 per 100,000 for both AAs and NHWs. The death rate for male HL patients was 0.4 per 100,000 for AAs and 0.5 per 100,000 in NHWs (not significant).

The death rate for female NHL patients was 3.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male NHL patients was 5.9 per 100,000 in AAs and 8.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female myeloma patients was 5.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male myeloma patients was 7.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The researchers noted that the reasons for the higher rates of myeloma and myeloma death among AAs are, at present, unknown. ![]()

receiving treatment

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new report suggests African Americans (AAs) have significantly lower rates of most hematologic malignancies than non-Hispanic white (NHW) individuals in the US.

AAs of both sexes had significantly lower rates of leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) than NHWs, but the rate of myeloma was significantly higher among AAs.

The death rates for these malignancies followed the same patterns, with the exception of HL. There was no significant difference in HL mortality between AAs and NHWs of either sex.

These findings can be found in the report, “Cancer Statistics for African Americans, 2016,” appearing in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

To compile this report, the researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries.

Incidence

For part of the report, the researchers compared the incidence of cancers between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

Among females, the incidence of leukemia was 8.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 10.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). Among males, the incidence was 13.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 17.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of HL in females was 2.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of HL in males was 3.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 3.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of NHL in females was 12.0 per 100,000 in AAs and 16.6 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of NHL in males was 17.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 24.1 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of myeloma in females was 11.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of myeloma in males was 14.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 7.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

Mortality

The researchers also compared cancer mortality between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

The death rate for female leukemia patients was 4.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male leukemia patients was 8.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 9.9 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female HL patients was 0.3 per 100,000 for both AAs and NHWs. The death rate for male HL patients was 0.4 per 100,000 for AAs and 0.5 per 100,000 in NHWs (not significant).

The death rate for female NHL patients was 3.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male NHL patients was 5.9 per 100,000 in AAs and 8.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female myeloma patients was 5.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male myeloma patients was 7.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The researchers noted that the reasons for the higher rates of myeloma and myeloma death among AAs are, at present, unknown. ![]()

receiving treatment

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new report suggests African Americans (AAs) have significantly lower rates of most hematologic malignancies than non-Hispanic white (NHW) individuals in the US.

AAs of both sexes had significantly lower rates of leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) than NHWs, but the rate of myeloma was significantly higher among AAs.

The death rates for these malignancies followed the same patterns, with the exception of HL. There was no significant difference in HL mortality between AAs and NHWs of either sex.

These findings can be found in the report, “Cancer Statistics for African Americans, 2016,” appearing in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

To compile this report, the researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries.

Incidence

For part of the report, the researchers compared the incidence of cancers between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

Among females, the incidence of leukemia was 8.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 10.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). Among males, the incidence was 13.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 17.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of HL in females was 2.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.7 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of HL in males was 3.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 3.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of NHL in females was 12.0 per 100,000 in AAs and 16.6 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of NHL in males was 17.2 per 100,000 in AAs and 24.1 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The incidence of myeloma in females was 11.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The incidence of myeloma in males was 14.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 7.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

Mortality

The researchers also compared cancer mortality between AAs and NHWs (divided by gender) for the period from 2008 to 2012.

The death rate for female leukemia patients was 4.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male leukemia patients was 8.1 per 100,000 in AAs and 9.9 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female HL patients was 0.3 per 100,000 for both AAs and NHWs. The death rate for male HL patients was 0.4 per 100,000 for AAs and 0.5 per 100,000 in NHWs (not significant).

The death rate for female NHL patients was 3.6 per 100,000 in AAs and 5.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male NHL patients was 5.9 per 100,000 in AAs and 8.3 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The death rate for female myeloma patients was 5.4 per 100,000 in AAs and 2.4 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05). The death rate for male myeloma patients was 7.8 per 100,000 in AAs and 4.0 per 100,000 in NHWs (P<0.05).

The researchers noted that the reasons for the higher rates of myeloma and myeloma death among AAs are, at present, unknown. ![]()

Study reveals subgroups of AYAs more likely to die of HL

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that race, insurance status, and socioeconomic status (SES) impact survival in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that patients diagnosed with HL between the ages of 15 and 39 are less likely to survive the disease if they are black, Hispanic, have no insurance or public health insurance, or live in a neighborhood with low SES.

Theresa H.M. Keegan, PhD, MS, of the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center in Sacramento, California, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Dr Keegan and her colleagues studied data from 9353 patients in the California Cancer Registry who were between 15 and 39 years old when they were diagnosed with HL between 1988 and 2011.

The team examined the impact of race/ethnicity, neighborhood SES, and health insurance on mortality.

The researchers found that AYAs diagnosed with early stage HL were twice as likely to die if they resided in a lower SES neighborhood.

Subjects were also twice as likely to die from HL if they had public health insurance or were uninsured, regardless of whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

Black AYA patients were 68% more likely to die of HL than non-Hispanic white patients, whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

And Hispanic AYA patients diagnosed at a late stage were 58% more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to die of HL, but there was no significant disparity for Hispanic patients diagnosed at an early stage.

“Identifying and reducing barriers to recommended treatment and surveillance in these AYAs at much higher risk of mortality is essential to ameliorating these survival disparities,” Dr Keegan said.

However, she and her colleagues noted that this study had limitations. The researchers were able to identify the first course of treatment but did not have specific details on the treatment that followed the initial period.

In addition, health insurance status at the time of diagnosis was not available for patients who were diagnosed before 2001, and the researchers did not have information on changes in patients’ insurance status that may have occurred after their initial treatment. ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that race, insurance status, and socioeconomic status (SES) impact survival in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that patients diagnosed with HL between the ages of 15 and 39 are less likely to survive the disease if they are black, Hispanic, have no insurance or public health insurance, or live in a neighborhood with low SES.

Theresa H.M. Keegan, PhD, MS, of the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center in Sacramento, California, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Dr Keegan and her colleagues studied data from 9353 patients in the California Cancer Registry who were between 15 and 39 years old when they were diagnosed with HL between 1988 and 2011.

The team examined the impact of race/ethnicity, neighborhood SES, and health insurance on mortality.

The researchers found that AYAs diagnosed with early stage HL were twice as likely to die if they resided in a lower SES neighborhood.

Subjects were also twice as likely to die from HL if they had public health insurance or were uninsured, regardless of whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

Black AYA patients were 68% more likely to die of HL than non-Hispanic white patients, whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

And Hispanic AYA patients diagnosed at a late stage were 58% more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to die of HL, but there was no significant disparity for Hispanic patients diagnosed at an early stage.

“Identifying and reducing barriers to recommended treatment and surveillance in these AYAs at much higher risk of mortality is essential to ameliorating these survival disparities,” Dr Keegan said.

However, she and her colleagues noted that this study had limitations. The researchers were able to identify the first course of treatment but did not have specific details on the treatment that followed the initial period.

In addition, health insurance status at the time of diagnosis was not available for patients who were diagnosed before 2001, and the researchers did not have information on changes in patients’ insurance status that may have occurred after their initial treatment. ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that race, insurance status, and socioeconomic status (SES) impact survival in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that patients diagnosed with HL between the ages of 15 and 39 are less likely to survive the disease if they are black, Hispanic, have no insurance or public health insurance, or live in a neighborhood with low SES.

Theresa H.M. Keegan, PhD, MS, of the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center in Sacramento, California, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Dr Keegan and her colleagues studied data from 9353 patients in the California Cancer Registry who were between 15 and 39 years old when they were diagnosed with HL between 1988 and 2011.

The team examined the impact of race/ethnicity, neighborhood SES, and health insurance on mortality.

The researchers found that AYAs diagnosed with early stage HL were twice as likely to die if they resided in a lower SES neighborhood.

Subjects were also twice as likely to die from HL if they had public health insurance or were uninsured, regardless of whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

Black AYA patients were 68% more likely to die of HL than non-Hispanic white patients, whether they were diagnosed at an early stage or a late stage.

And Hispanic AYA patients diagnosed at a late stage were 58% more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to die of HL, but there was no significant disparity for Hispanic patients diagnosed at an early stage.

“Identifying and reducing barriers to recommended treatment and surveillance in these AYAs at much higher risk of mortality is essential to ameliorating these survival disparities,” Dr Keegan said.

However, she and her colleagues noted that this study had limitations. The researchers were able to identify the first course of treatment but did not have specific details on the treatment that followed the initial period.

In addition, health insurance status at the time of diagnosis was not available for patients who were diagnosed before 2001, and the researchers did not have information on changes in patients’ insurance status that may have occurred after their initial treatment. ![]()

Appalachia has higher cancer incidence than rest of US

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that people living in the Appalachian region of the US are more likely to develop cancer than people in the rest of the country.

The study showed that Appalachians had a significantly higher incidence of cancer overall and higher rates of many solid tumor malignancies.

However, lymphoma rates were similar between Appalachians and non-Appalachians, and Appalachians had a significantly lower rate of myeloma.

This research was published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“The Appalachian region, which extends from parts of New York to Mississippi, spans 420 counties in 13 US states, and about 25 million people reside in this area,” said study author Reda Wilson, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia.

“This region is primarily made up of rural areas, with persistent poverty levels that are at least 20%, which is higher than the national average.”

In 2007, the CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) published a comprehensive evaluation of cancer incidence rates in Appalachia between 2001 and 2003.

The data showed higher cancer rates in Appalachia than in the rest of the US. However, this publication had some shortcomings, including data that were not available for analysis.

“The current analyses reported here were performed to update the earlier evaluation by expanding the diagnosis years from 2004 to 2011 and including data on 100% of the Appalachian and non-Appalachian populations,” Wilson said.

For this study, Wilson and her colleagues used data from the NPCR and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Together, NPCR and SEER cover 100% of the US population.

The researchers analyzed the Appalachian population by region (north, central, and south Appalachia), gender, race (black and white only), and Appalachian Regional Commission-designated economic status (distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, and attainment). And the team compared these data with data on the non-Appalachian population.

The results showed that cancer incidence rates (IRs) were elevated among Appalachians regardless of how they were categorized. The IRs were per 100,000 people, age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.

The IR for all cancers was 565.8 for males in Appalachia and 543.0 for non-Appalachian males (P<0.05). And the cancer IRs for females were 428.7 in Appalachia and 418.2 outside the region (P<0.05).

There was no significant difference between the regions in IRs for lymphomas. The Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 3.1 in Appalachian males, 3.2 in non-Appalachian males, and 2.5 for females in both regions.

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 23.3 in Appalachian males, 23.4 in non-Appalachian males, 16.4 in Appalachian females, and 16.3 in non-Appalachian females.

Myeloma IRs were significantly lower in Appalachia (P<0.05). The myeloma IRs were 7.3 in Appalachian males, 7.5 in non-Appalachian males, 4.7 in Appalachian females, and 4.9 in non-Appalachian females.

There was no significant difference in leukemia IRs among males, but females in Appalachia had a significantly higher leukemia IR (P<0.05). The leukemia IRs were 16.9 in Appalachian males, 16.7 in non-Appalachian males, 10.4 in Appalachian females, and 10.2 in non-Appalachian females.

“Appalachia continues to have higher cancer incidence rates than the rest of the country,” Wilson said. “But a promising finding is that we’re seeing the gap narrow in the incidence rates between Appalachia and non-Appalachia since the 2007 analysis, with the exception of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx, larynx, lung and bronchus, and thyroid.”

“This study helps identify types of cancer in the Appalachian region that could be reduced through more evidence-based screening and detection. Our study also emphasizes the importance of lifestyle changes needed to prevent and reduce cancer burden.”

The researchers noted that this study did not differentiate urban versus rural areas within each county, and data on screening and risk factors were based on self-reported responses.

Furthermore, cancer IRs were calculated for all ages combined and were not evaluated by age groups. Future analyses will be targeted toward capturing these finer details, Wilson said. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that people living in the Appalachian region of the US are more likely to develop cancer than people in the rest of the country.

The study showed that Appalachians had a significantly higher incidence of cancer overall and higher rates of many solid tumor malignancies.

However, lymphoma rates were similar between Appalachians and non-Appalachians, and Appalachians had a significantly lower rate of myeloma.

This research was published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“The Appalachian region, which extends from parts of New York to Mississippi, spans 420 counties in 13 US states, and about 25 million people reside in this area,” said study author Reda Wilson, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia.

“This region is primarily made up of rural areas, with persistent poverty levels that are at least 20%, which is higher than the national average.”

In 2007, the CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) published a comprehensive evaluation of cancer incidence rates in Appalachia between 2001 and 2003.

The data showed higher cancer rates in Appalachia than in the rest of the US. However, this publication had some shortcomings, including data that were not available for analysis.

“The current analyses reported here were performed to update the earlier evaluation by expanding the diagnosis years from 2004 to 2011 and including data on 100% of the Appalachian and non-Appalachian populations,” Wilson said.

For this study, Wilson and her colleagues used data from the NPCR and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Together, NPCR and SEER cover 100% of the US population.

The researchers analyzed the Appalachian population by region (north, central, and south Appalachia), gender, race (black and white only), and Appalachian Regional Commission-designated economic status (distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, and attainment). And the team compared these data with data on the non-Appalachian population.

The results showed that cancer incidence rates (IRs) were elevated among Appalachians regardless of how they were categorized. The IRs were per 100,000 people, age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.

The IR for all cancers was 565.8 for males in Appalachia and 543.0 for non-Appalachian males (P<0.05). And the cancer IRs for females were 428.7 in Appalachia and 418.2 outside the region (P<0.05).

There was no significant difference between the regions in IRs for lymphomas. The Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 3.1 in Appalachian males, 3.2 in non-Appalachian males, and 2.5 for females in both regions.

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 23.3 in Appalachian males, 23.4 in non-Appalachian males, 16.4 in Appalachian females, and 16.3 in non-Appalachian females.

Myeloma IRs were significantly lower in Appalachia (P<0.05). The myeloma IRs were 7.3 in Appalachian males, 7.5 in non-Appalachian males, 4.7 in Appalachian females, and 4.9 in non-Appalachian females.

There was no significant difference in leukemia IRs among males, but females in Appalachia had a significantly higher leukemia IR (P<0.05). The leukemia IRs were 16.9 in Appalachian males, 16.7 in non-Appalachian males, 10.4 in Appalachian females, and 10.2 in non-Appalachian females.

“Appalachia continues to have higher cancer incidence rates than the rest of the country,” Wilson said. “But a promising finding is that we’re seeing the gap narrow in the incidence rates between Appalachia and non-Appalachia since the 2007 analysis, with the exception of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx, larynx, lung and bronchus, and thyroid.”

“This study helps identify types of cancer in the Appalachian region that could be reduced through more evidence-based screening and detection. Our study also emphasizes the importance of lifestyle changes needed to prevent and reduce cancer burden.”

The researchers noted that this study did not differentiate urban versus rural areas within each county, and data on screening and risk factors were based on self-reported responses.

Furthermore, cancer IRs were calculated for all ages combined and were not evaluated by age groups. Future analyses will be targeted toward capturing these finer details, Wilson said. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

New research suggests that people living in the Appalachian region of the US are more likely to develop cancer than people in the rest of the country.

The study showed that Appalachians had a significantly higher incidence of cancer overall and higher rates of many solid tumor malignancies.

However, lymphoma rates were similar between Appalachians and non-Appalachians, and Appalachians had a significantly lower rate of myeloma.

This research was published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

“The Appalachian region, which extends from parts of New York to Mississippi, spans 420 counties in 13 US states, and about 25 million people reside in this area,” said study author Reda Wilson, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia.

“This region is primarily made up of rural areas, with persistent poverty levels that are at least 20%, which is higher than the national average.”

In 2007, the CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) published a comprehensive evaluation of cancer incidence rates in Appalachia between 2001 and 2003.

The data showed higher cancer rates in Appalachia than in the rest of the US. However, this publication had some shortcomings, including data that were not available for analysis.

“The current analyses reported here were performed to update the earlier evaluation by expanding the diagnosis years from 2004 to 2011 and including data on 100% of the Appalachian and non-Appalachian populations,” Wilson said.

For this study, Wilson and her colleagues used data from the NPCR and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Together, NPCR and SEER cover 100% of the US population.

The researchers analyzed the Appalachian population by region (north, central, and south Appalachia), gender, race (black and white only), and Appalachian Regional Commission-designated economic status (distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive, and attainment). And the team compared these data with data on the non-Appalachian population.

The results showed that cancer incidence rates (IRs) were elevated among Appalachians regardless of how they were categorized. The IRs were per 100,000 people, age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.

The IR for all cancers was 565.8 for males in Appalachia and 543.0 for non-Appalachian males (P<0.05). And the cancer IRs for females were 428.7 in Appalachia and 418.2 outside the region (P<0.05).

There was no significant difference between the regions in IRs for lymphomas. The Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 3.1 in Appalachian males, 3.2 in non-Appalachian males, and 2.5 for females in both regions.

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma IRs were 23.3 in Appalachian males, 23.4 in non-Appalachian males, 16.4 in Appalachian females, and 16.3 in non-Appalachian females.

Myeloma IRs were significantly lower in Appalachia (P<0.05). The myeloma IRs were 7.3 in Appalachian males, 7.5 in non-Appalachian males, 4.7 in Appalachian females, and 4.9 in non-Appalachian females.

There was no significant difference in leukemia IRs among males, but females in Appalachia had a significantly higher leukemia IR (P<0.05). The leukemia IRs were 16.9 in Appalachian males, 16.7 in non-Appalachian males, 10.4 in Appalachian females, and 10.2 in non-Appalachian females.

“Appalachia continues to have higher cancer incidence rates than the rest of the country,” Wilson said. “But a promising finding is that we’re seeing the gap narrow in the incidence rates between Appalachia and non-Appalachia since the 2007 analysis, with the exception of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx, larynx, lung and bronchus, and thyroid.”

“This study helps identify types of cancer in the Appalachian region that could be reduced through more evidence-based screening and detection. Our study also emphasizes the importance of lifestyle changes needed to prevent and reduce cancer burden.”

The researchers noted that this study did not differentiate urban versus rural areas within each county, and data on screening and risk factors were based on self-reported responses.

Furthermore, cancer IRs were calculated for all ages combined and were not evaluated by age groups. Future analyses will be targeted toward capturing these finer details, Wilson said. ![]()

Race plays role in Hodgkin lymphoma outcomes in kids

Photo courtesy of Sylvester

Comprehensive Cancer Center

In a retrospective study, young African American patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) had inferior long-term overall survival when compared to their Hispanic and white peers.

Hispanic and white patients had similar rates of overall survival, but Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.

The study, published in Pediatric Blood & Cancer, is the largest yet on racial and ethnic disparity in the pediatric HL population in the US.

“Little was known about the association between race, ethnicity, and survival in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population,” said Joseph Panoff, MD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida.

“Our study showed that African American children and teenagers had worse overall survival than whites and Hispanics at 25 years after diagnosis. We also found that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.”

Dr Panoff and his colleagues analyzed data from more than 7800 patients listed in the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS) and the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).

The patients were 0.1 to 21 years of age (average, 17 years) and were diagnosed with HL from 1981 to 2010.

In the FCDS cohort, which was significantly smaller than the SEER cohort (1778 vs 6027), African Americans had a 33% overall survival rate at 25 years, compared to 44.7% for Hispanics and 49.2% for whites (P=0.0005).

In a multivariate analysis, African American race was associated with inferior overall survival. The hazard ratio was 1.81 (P=0.0003).

Patients in the FCDS cohort had worse overall survival than patients in the SEER cohort, indicating that patients treated in Florida have worse outcomes when compared to the rest of the nation.

In the SEER cohort, the overall survival rate at 25 years was 74.2% for African Americans and 82% for both Hispanic and white patients (P=0.0005). Disease-specific survival rates at 25 years were 85.7% for African Americans, 88.1% for Hispanics, and 90.8% for whites (P=0.0002).

The researchers noted that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival when compared to white males—84.8% and 90.6%, respectively (P=0.0478).

And Hispanic race was a predictor of inferior disease-specific survival in multivariate analysis. The hazard ratio was 1.238 (P<0.0001).

“Clearly, racial and ethnic disparities persist in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population, despite modern treatment, particularly in Florida,” Dr Panoff noted. “The underlying causes of these disparities are complex and need further explanation.”

As a next step, Dr Panoff suggests identifying flaws in the diagnostic and treatment process with regard to African American and Hispanic patients.

“It is important to identify sociocultural factors and health behaviors that negatively affect overall survival in African American patients and disease-free survival in Hispanic males,” he said. “The fact that the entire Florida cohort seems to have worse overall survival than patients in the rest of the country is a new finding that requires further research.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of Sylvester

Comprehensive Cancer Center

In a retrospective study, young African American patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) had inferior long-term overall survival when compared to their Hispanic and white peers.

Hispanic and white patients had similar rates of overall survival, but Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.

The study, published in Pediatric Blood & Cancer, is the largest yet on racial and ethnic disparity in the pediatric HL population in the US.

“Little was known about the association between race, ethnicity, and survival in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population,” said Joseph Panoff, MD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida.

“Our study showed that African American children and teenagers had worse overall survival than whites and Hispanics at 25 years after diagnosis. We also found that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.”

Dr Panoff and his colleagues analyzed data from more than 7800 patients listed in the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS) and the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).

The patients were 0.1 to 21 years of age (average, 17 years) and were diagnosed with HL from 1981 to 2010.

In the FCDS cohort, which was significantly smaller than the SEER cohort (1778 vs 6027), African Americans had a 33% overall survival rate at 25 years, compared to 44.7% for Hispanics and 49.2% for whites (P=0.0005).

In a multivariate analysis, African American race was associated with inferior overall survival. The hazard ratio was 1.81 (P=0.0003).

Patients in the FCDS cohort had worse overall survival than patients in the SEER cohort, indicating that patients treated in Florida have worse outcomes when compared to the rest of the nation.

In the SEER cohort, the overall survival rate at 25 years was 74.2% for African Americans and 82% for both Hispanic and white patients (P=0.0005). Disease-specific survival rates at 25 years were 85.7% for African Americans, 88.1% for Hispanics, and 90.8% for whites (P=0.0002).

The researchers noted that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival when compared to white males—84.8% and 90.6%, respectively (P=0.0478).

And Hispanic race was a predictor of inferior disease-specific survival in multivariate analysis. The hazard ratio was 1.238 (P<0.0001).

“Clearly, racial and ethnic disparities persist in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population, despite modern treatment, particularly in Florida,” Dr Panoff noted. “The underlying causes of these disparities are complex and need further explanation.”

As a next step, Dr Panoff suggests identifying flaws in the diagnostic and treatment process with regard to African American and Hispanic patients.

“It is important to identify sociocultural factors and health behaviors that negatively affect overall survival in African American patients and disease-free survival in Hispanic males,” he said. “The fact that the entire Florida cohort seems to have worse overall survival than patients in the rest of the country is a new finding that requires further research.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of Sylvester

Comprehensive Cancer Center

In a retrospective study, young African American patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) had inferior long-term overall survival when compared to their Hispanic and white peers.

Hispanic and white patients had similar rates of overall survival, but Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.

The study, published in Pediatric Blood & Cancer, is the largest yet on racial and ethnic disparity in the pediatric HL population in the US.

“Little was known about the association between race, ethnicity, and survival in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population,” said Joseph Panoff, MD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida.

“Our study showed that African American children and teenagers had worse overall survival than whites and Hispanics at 25 years after diagnosis. We also found that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival compared to white males.”

Dr Panoff and his colleagues analyzed data from more than 7800 patients listed in the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS) and the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).

The patients were 0.1 to 21 years of age (average, 17 years) and were diagnosed with HL from 1981 to 2010.

In the FCDS cohort, which was significantly smaller than the SEER cohort (1778 vs 6027), African Americans had a 33% overall survival rate at 25 years, compared to 44.7% for Hispanics and 49.2% for whites (P=0.0005).

In a multivariate analysis, African American race was associated with inferior overall survival. The hazard ratio was 1.81 (P=0.0003).

Patients in the FCDS cohort had worse overall survival than patients in the SEER cohort, indicating that patients treated in Florida have worse outcomes when compared to the rest of the nation.

In the SEER cohort, the overall survival rate at 25 years was 74.2% for African Americans and 82% for both Hispanic and white patients (P=0.0005). Disease-specific survival rates at 25 years were 85.7% for African Americans, 88.1% for Hispanics, and 90.8% for whites (P=0.0002).

The researchers noted that Hispanic males had inferior disease-specific survival when compared to white males—84.8% and 90.6%, respectively (P=0.0478).

And Hispanic race was a predictor of inferior disease-specific survival in multivariate analysis. The hazard ratio was 1.238 (P<0.0001).

“Clearly, racial and ethnic disparities persist in the pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma population, despite modern treatment, particularly in Florida,” Dr Panoff noted. “The underlying causes of these disparities are complex and need further explanation.”

As a next step, Dr Panoff suggests identifying flaws in the diagnostic and treatment process with regard to African American and Hispanic patients.

“It is important to identify sociocultural factors and health behaviors that negatively affect overall survival in African American patients and disease-free survival in Hispanic males,” he said. “The fact that the entire Florida cohort seems to have worse overall survival than patients in the rest of the country is a new finding that requires further research.” ![]()

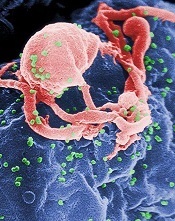

Concerning number of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma patients go untreated

Lower 5-year survival among HIV-positive vs. HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients is largely attributable to a high rate of non-treatment among those who are HIV positive, a review of cases from the National Cancer Data Base suggests.

Of 2,090 HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2012 and included in the database, 81% received chemotherapy, and 13% received radiation therapy, but 16% received no treatment. Survival was 66% compared with 80% survival among HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients, reported Dr. Adam J. Olszewski of Brown University, Providence, R.I. and Dr. Jorge J. Castillo of Harvard Medical School, Boston (AIDS. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000986).

Another factor that contributed to the disparity was poor prognosis in patients with undetermined histologic subtype.

Among patients who received chemotherapy, HIV-positive status was not significantly associated with increased mortality in those with classical histologic subtypes, the authors said.

For example, the hazard ratios for mortality were 1.08 for nodular sclerosis and 1.06 for mixed cellularity. Those with undetermined histology had a significantly worse prognosis (hazard ratio, 1.56), and particular attention should be paid to these patients given their worse prognosis and high risk of nontreatment, the authors said.

Factors found on logistic regression analysis to be associated with higher risk of nontreatment among all patients were advanced age, male sex, nonwhite race, poor socioeconomic status, and undetermined histologic subtype. In 2012, the majority of HIV-positive patients were of nonwhite race; nearly half (49%) were black – an increase from 31% in 2004, and 15% were Hispanic, which raises additional concerns about the disparity in treatment delivery between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, they noted.

Dr. Olszewski is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award. Both authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Lower 5-year survival among HIV-positive vs. HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients is largely attributable to a high rate of non-treatment among those who are HIV positive, a review of cases from the National Cancer Data Base suggests.

Of 2,090 HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2012 and included in the database, 81% received chemotherapy, and 13% received radiation therapy, but 16% received no treatment. Survival was 66% compared with 80% survival among HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients, reported Dr. Adam J. Olszewski of Brown University, Providence, R.I. and Dr. Jorge J. Castillo of Harvard Medical School, Boston (AIDS. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000986).

Another factor that contributed to the disparity was poor prognosis in patients with undetermined histologic subtype.

Among patients who received chemotherapy, HIV-positive status was not significantly associated with increased mortality in those with classical histologic subtypes, the authors said.

For example, the hazard ratios for mortality were 1.08 for nodular sclerosis and 1.06 for mixed cellularity. Those with undetermined histology had a significantly worse prognosis (hazard ratio, 1.56), and particular attention should be paid to these patients given their worse prognosis and high risk of nontreatment, the authors said.

Factors found on logistic regression analysis to be associated with higher risk of nontreatment among all patients were advanced age, male sex, nonwhite race, poor socioeconomic status, and undetermined histologic subtype. In 2012, the majority of HIV-positive patients were of nonwhite race; nearly half (49%) were black – an increase from 31% in 2004, and 15% were Hispanic, which raises additional concerns about the disparity in treatment delivery between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, they noted.

Dr. Olszewski is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award. Both authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Lower 5-year survival among HIV-positive vs. HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients is largely attributable to a high rate of non-treatment among those who are HIV positive, a review of cases from the National Cancer Data Base suggests.

Of 2,090 HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2012 and included in the database, 81% received chemotherapy, and 13% received radiation therapy, but 16% received no treatment. Survival was 66% compared with 80% survival among HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients, reported Dr. Adam J. Olszewski of Brown University, Providence, R.I. and Dr. Jorge J. Castillo of Harvard Medical School, Boston (AIDS. 2016 Jan 4. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000986).

Another factor that contributed to the disparity was poor prognosis in patients with undetermined histologic subtype.

Among patients who received chemotherapy, HIV-positive status was not significantly associated with increased mortality in those with classical histologic subtypes, the authors said.

For example, the hazard ratios for mortality were 1.08 for nodular sclerosis and 1.06 for mixed cellularity. Those with undetermined histology had a significantly worse prognosis (hazard ratio, 1.56), and particular attention should be paid to these patients given their worse prognosis and high risk of nontreatment, the authors said.

Factors found on logistic regression analysis to be associated with higher risk of nontreatment among all patients were advanced age, male sex, nonwhite race, poor socioeconomic status, and undetermined histologic subtype. In 2012, the majority of HIV-positive patients were of nonwhite race; nearly half (49%) were black – an increase from 31% in 2004, and 15% were Hispanic, which raises additional concerns about the disparity in treatment delivery between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, they noted.

Dr. Olszewski is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award. Both authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM AIDS

Key clinical point: Lower 5-year survival among HIV-positive vs. HIV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma patients is largely attributable to a high rate of nontreatment among those who are HIV positive, a review of cases from the National Cancer Data Base suggests.

Major finding: Sixteen percent of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma patients were untreated.

Data source: A review of 2,090 cases from the National Cancer Data Base.

Disclosures: Dr. Olszewski is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award. Both authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Cancer survival tied to reduction in treatment

Photo by Bill Branson

Results of a large study suggest that long-term survivors of childhood cancer are living longer, partly due to a reduction in the use of certain treatments.

The 15-year death rate among the more than 34,000 childhood cancer survivors studied decreased steadily from 1970 onward.

And this decline coincided with changes in pediatric cancer therapy, including reductions in the use and dose of radiation therapy and anthracyclines.

These therapies are known to put cancer survivors at increased risk for developing second malignancies, heart failure, and other serious health problems.

“This study is the first to show that younger survivors from more recent treatment eras are less likely to die from the late effects of cancer treatment and more likely to enjoy longer lives,” said study author Greg Armstrong, MD, of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

He and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 34,033 subjects who had been diagnosed with cancer and received treatment between 1970 and 1999 when they were age 20 or younger. All patients lived at least 5 years after their cancers were discovered and were considered long-term survivors.

Changes in mortality

At a median follow-up of 21 years (range, 5 to 38), there were 3958 deaths. Forty-one percent of deaths (n=1618) were considered health-related. This included 746 deaths from subsequent neoplasms, 241 from cardiac causes, 137 from pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

The 15-year death rate (death from any cause) fell from 12.4% in the early 1970s to 6% in the 1990s (P<0.001). During the same period, the rate of death from health-related causes fell from 3.5% to 2.1% (P<0.001).

The researchers said there were significant reductions across treatment eras in the rates of death from any health-related cause among patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma, but not among patients with other cancers.

The rate of health-related death among ALL patients fell from 3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s (P<0.001). The rate fell from 5.3% to 2.6% (P=0.006) for HL patients, from 2.6% to 0.4% (P=0.005) for Wilms’ tumor patients, and from 4.7% to 1.8% (P=0.02) for astrocytoma patients.

The researchers said these reductions in mortality were attributable to decreases in the rates of death from subsequent neoplasm (P<0.001), cardiac causes (P<0.001), and pulmonary causes (P=0.04).

Treatment changes

The overall use of anthracyclines fell from 73% in the 1970s to 42% in the 1990s. And the use of any radiation decreased from 77% to 41%.

The use of cranial radiotherapy for ALL fell from 85% to 19%. The use of abdominal radiotherapy for Wilms’ tumor decreased from 78% to 43%. And the use of chest radiotherapy for HL fell from 87% to 61%.

The researchers noted that temporal reductions in 15-year rates of death from health-related causes followed temporal reductions in therapeutic exposure for patients with ALL, HL, Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma.

However, when the team adjusted their analysis for therapy (eg, anthracycline dose), the effect of the treatment era on the relative rate of death from health-related causes was attenuated in ALL (unadjusted relative rate=0.88, adjusted relative rate=1.02) and Wilms’ tumor (0.68 and 0.80, respectively) but not in HL (0.79 in both models) and astrocytoma (0.81 and 0.82, respectively).

Still, the researchers said the results of this study suggest the strategy of lowering therapeutic exposure has contributed to the decline in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Results of a large study suggest that long-term survivors of childhood cancer are living longer, partly due to a reduction in the use of certain treatments.

The 15-year death rate among the more than 34,000 childhood cancer survivors studied decreased steadily from 1970 onward.

And this decline coincided with changes in pediatric cancer therapy, including reductions in the use and dose of radiation therapy and anthracyclines.

These therapies are known to put cancer survivors at increased risk for developing second malignancies, heart failure, and other serious health problems.

“This study is the first to show that younger survivors from more recent treatment eras are less likely to die from the late effects of cancer treatment and more likely to enjoy longer lives,” said study author Greg Armstrong, MD, of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

He and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 34,033 subjects who had been diagnosed with cancer and received treatment between 1970 and 1999 when they were age 20 or younger. All patients lived at least 5 years after their cancers were discovered and were considered long-term survivors.

Changes in mortality

At a median follow-up of 21 years (range, 5 to 38), there were 3958 deaths. Forty-one percent of deaths (n=1618) were considered health-related. This included 746 deaths from subsequent neoplasms, 241 from cardiac causes, 137 from pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

The 15-year death rate (death from any cause) fell from 12.4% in the early 1970s to 6% in the 1990s (P<0.001). During the same period, the rate of death from health-related causes fell from 3.5% to 2.1% (P<0.001).

The researchers said there were significant reductions across treatment eras in the rates of death from any health-related cause among patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma, but not among patients with other cancers.

The rate of health-related death among ALL patients fell from 3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s (P<0.001). The rate fell from 5.3% to 2.6% (P=0.006) for HL patients, from 2.6% to 0.4% (P=0.005) for Wilms’ tumor patients, and from 4.7% to 1.8% (P=0.02) for astrocytoma patients.

The researchers said these reductions in mortality were attributable to decreases in the rates of death from subsequent neoplasm (P<0.001), cardiac causes (P<0.001), and pulmonary causes (P=0.04).

Treatment changes

The overall use of anthracyclines fell from 73% in the 1970s to 42% in the 1990s. And the use of any radiation decreased from 77% to 41%.

The use of cranial radiotherapy for ALL fell from 85% to 19%. The use of abdominal radiotherapy for Wilms’ tumor decreased from 78% to 43%. And the use of chest radiotherapy for HL fell from 87% to 61%.

The researchers noted that temporal reductions in 15-year rates of death from health-related causes followed temporal reductions in therapeutic exposure for patients with ALL, HL, Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma.

However, when the team adjusted their analysis for therapy (eg, anthracycline dose), the effect of the treatment era on the relative rate of death from health-related causes was attenuated in ALL (unadjusted relative rate=0.88, adjusted relative rate=1.02) and Wilms’ tumor (0.68 and 0.80, respectively) but not in HL (0.79 in both models) and astrocytoma (0.81 and 0.82, respectively).

Still, the researchers said the results of this study suggest the strategy of lowering therapeutic exposure has contributed to the decline in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Results of a large study suggest that long-term survivors of childhood cancer are living longer, partly due to a reduction in the use of certain treatments.

The 15-year death rate among the more than 34,000 childhood cancer survivors studied decreased steadily from 1970 onward.

And this decline coincided with changes in pediatric cancer therapy, including reductions in the use and dose of radiation therapy and anthracyclines.

These therapies are known to put cancer survivors at increased risk for developing second malignancies, heart failure, and other serious health problems.

“This study is the first to show that younger survivors from more recent treatment eras are less likely to die from the late effects of cancer treatment and more likely to enjoy longer lives,” said study author Greg Armstrong, MD, of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

He and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 34,033 subjects who had been diagnosed with cancer and received treatment between 1970 and 1999 when they were age 20 or younger. All patients lived at least 5 years after their cancers were discovered and were considered long-term survivors.

Changes in mortality

At a median follow-up of 21 years (range, 5 to 38), there were 3958 deaths. Forty-one percent of deaths (n=1618) were considered health-related. This included 746 deaths from subsequent neoplasms, 241 from cardiac causes, 137 from pulmonary causes, and 494 from other causes.

The 15-year death rate (death from any cause) fell from 12.4% in the early 1970s to 6% in the 1990s (P<0.001). During the same period, the rate of death from health-related causes fell from 3.5% to 2.1% (P<0.001).

The researchers said there were significant reductions across treatment eras in the rates of death from any health-related cause among patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma, but not among patients with other cancers.

The rate of health-related death among ALL patients fell from 3.2% in the early 1970s to 2.1% in the 1990s (P<0.001). The rate fell from 5.3% to 2.6% (P=0.006) for HL patients, from 2.6% to 0.4% (P=0.005) for Wilms’ tumor patients, and from 4.7% to 1.8% (P=0.02) for astrocytoma patients.

The researchers said these reductions in mortality were attributable to decreases in the rates of death from subsequent neoplasm (P<0.001), cardiac causes (P<0.001), and pulmonary causes (P=0.04).

Treatment changes

The overall use of anthracyclines fell from 73% in the 1970s to 42% in the 1990s. And the use of any radiation decreased from 77% to 41%.

The use of cranial radiotherapy for ALL fell from 85% to 19%. The use of abdominal radiotherapy for Wilms’ tumor decreased from 78% to 43%. And the use of chest radiotherapy for HL fell from 87% to 61%.

The researchers noted that temporal reductions in 15-year rates of death from health-related causes followed temporal reductions in therapeutic exposure for patients with ALL, HL, Wilms’ tumor, and astrocytoma.

However, when the team adjusted their analysis for therapy (eg, anthracycline dose), the effect of the treatment era on the relative rate of death from health-related causes was attenuated in ALL (unadjusted relative rate=0.88, adjusted relative rate=1.02) and Wilms’ tumor (0.68 and 0.80, respectively) but not in HL (0.79 in both models) and astrocytoma (0.81 and 0.82, respectively).

Still, the researchers said the results of this study suggest the strategy of lowering therapeutic exposure has contributed to the decline in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer.

Hodgkin lymphoma going untreated in patients with HIV

cultured lymphocyte

Image courtesy of the CDC

Patients with HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma may not be getting potentially curative treatment, according to a study published in the journal AIDS.

The study showed that 16% of HIV-positive patients did not receive treatment for their lymphoma, compared to 9% of Hodgkin lymphoma patients who were HIV-negative.

“Hodgkin lymphoma is generally believed to be highly curable,” said study author Adam Olszewski, MD, of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

“We have an expectation to cure over 90% of early stage patients and even 70% to 80% of quite advanced cases.”

It hasn’t been clear whether HIV-positive patients with Hodgkin lymphoma survive the cancer as well as people who are HIV-negative. While some small studies, particularly in Europe, have shown that HIV status makes no difference to survival, observations in the US population suggest that being HIV-positive makes survival less likely.

The new study, which is the largest of its kind to date, may reconcile that conflict. It suggests that, in the US, the reason people with HIV seem to fare worse with the cancer is because they are less likely to be treated for it.

The study included 2090 cases of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma recorded in the National Cancer Data Base between 2004 and 2012, as well as 41,846 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma in patients who were HIV-negative.

The unadjusted 5-year overall survival was 66% for HIV-positive patients and 80% for the HIV-negative population.

Among the HIV-positive patients, 81% received chemotherapy (12% in combination with radiation), 13% received any radiation therapy, and 16% received no treatment for their lymphoma. The corresponding numbers for HIV-negative patients were 87%, 31%, and 9%, respectively (P<0.00001 for all comparisons).

The researchers assessed patient- and disease-related factors associated with the risk of not receiving chemotherapy in the HIV-positive population.

And they found the risk was significantly higher for patients who were older than 40, male, “nonwhite” (black, Hispanic, or Asian/”other”), did not have health insurance, lived in areas with the lowest median income, and had early stage Hodgkin lymphoma or an undetermined histology.

Dr Olszewski said the lack of treatment among HIV-positive patients could be due to a lingering assumption that they won’t tolerate the treatment well. Or some patients may be declining treatment, either for HIV (thereby making them seem more vulnerable) or for the lymphoma itself.

He noted, however, that lymphoma treatment can be effective for and tolerated by HIV-positive patients, especially when the lymphoma subtype is known.

Among the patients who received chemotherapy in this study, there was no significant difference in the hazard of death between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients who had one of the defined classical histologic subtypes: nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte-rich, or lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma. However, mortality was significantly higher for HIV-positive patients with an undetermined histologic subtype.

cultured lymphocyte

Image courtesy of the CDC

Patients with HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma may not be getting potentially curative treatment, according to a study published in the journal AIDS.

The study showed that 16% of HIV-positive patients did not receive treatment for their lymphoma, compared to 9% of Hodgkin lymphoma patients who were HIV-negative.

“Hodgkin lymphoma is generally believed to be highly curable,” said study author Adam Olszewski, MD, of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

“We have an expectation to cure over 90% of early stage patients and even 70% to 80% of quite advanced cases.”