User login

6 Tips for Community Hospitalists Initiating QI Projects

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

Hot Topics in Practice Management; HM15 Session Analysis

HM15 Presenters: Roy Sittig MD SFHM, Jeffrey Frank MD MBA, Jodi Braun

Summation: Speakers covered timely topics regarding the Accountable Care Act, namely Medicaid Expansion and Bundled Payment arrangements; and reviewed the seminal paper on “Key Principals and Characteristics of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group” and lessons learned in implementing those 10 Key Principles.

Medicaid Expansion: EDs serving the 29 Medicaid expansion states are reporting higher volumes, likely due to 11.4million new lives now insured under the ACA. While the ACA does provide for higher Medicaid payment rates thus far, only 34% of providers accept Medicaid, a 21% drop since the ACA went into effect.

Bundled Payment Arrangements:

- Bundled Payment Care Initiative (BPCI) lexicon:

- Model 2-Episode Anchor (anchor admission) AND 90days post d/c; Medicare pays 98% of usual cost

- Model 3-90days post d/c AFTER anchor admission; Medicare pays 97% of usual cost

- Convener-entity that brings providers together and enters into CMS agreement to bear risk for bundles

- Awardee (entity having agreement with Medicare to assume risk and receive payment via BPCI) and Convener own the Bundle

- Episode initiator (EI) triggers “bundle period”

- Bundles based on DRG

10-Key Principles of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group:

- Effective Leadership

- Engaged Hospitalists

- Adequate Resources

- Planning and Management Infrastructure

- Alignment with Hospital/Health System

- Care Coordination Across Settings

- Leadership in Key Clinical Issues in the Hospital/Health System

- Thoughtful Approach to Scope of Activity

- Patient/Family-Centered, Team-Based Care; Effective Communication

- Recruiting/Retaining Qualified Clinicians

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

Medicaid Expansion- many of the 11.4M newly insured lives under the ACA have moved into Medicaid. Only about 1/3 of providers now accept Medicaid- 1 in 5 covered persons now have Medicaid, nearly 20% increase since 2013.

Bundled Payments- Majority of savings opportunity lies in Post-Acute Care. Awardee and Convener make profit is total cost is less than 98% of Target Price. In gainsharing agreements individuals can be reimbursed up to 150% usual Medicare rate. Pay occurs in usual Medicare fashion but is reconciled 60-90 days after end of bundle. For more information: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

Effective HM Groups- Three important areas for focus when beginning to address group performance are: engaged hospitalists, planning and management infrastructure, care coordination across settings. These three topics have broad reaching implications into the hospitalist practice and patient care. [Cawley P, et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2014; 9(2):123-128]

HM15 Presenters: Roy Sittig MD SFHM, Jeffrey Frank MD MBA, Jodi Braun

Summation: Speakers covered timely topics regarding the Accountable Care Act, namely Medicaid Expansion and Bundled Payment arrangements; and reviewed the seminal paper on “Key Principals and Characteristics of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group” and lessons learned in implementing those 10 Key Principles.

Medicaid Expansion: EDs serving the 29 Medicaid expansion states are reporting higher volumes, likely due to 11.4million new lives now insured under the ACA. While the ACA does provide for higher Medicaid payment rates thus far, only 34% of providers accept Medicaid, a 21% drop since the ACA went into effect.

Bundled Payment Arrangements:

- Bundled Payment Care Initiative (BPCI) lexicon:

- Model 2-Episode Anchor (anchor admission) AND 90days post d/c; Medicare pays 98% of usual cost

- Model 3-90days post d/c AFTER anchor admission; Medicare pays 97% of usual cost

- Convener-entity that brings providers together and enters into CMS agreement to bear risk for bundles

- Awardee (entity having agreement with Medicare to assume risk and receive payment via BPCI) and Convener own the Bundle

- Episode initiator (EI) triggers “bundle period”

- Bundles based on DRG

10-Key Principles of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group:

- Effective Leadership

- Engaged Hospitalists

- Adequate Resources

- Planning and Management Infrastructure

- Alignment with Hospital/Health System

- Care Coordination Across Settings

- Leadership in Key Clinical Issues in the Hospital/Health System

- Thoughtful Approach to Scope of Activity

- Patient/Family-Centered, Team-Based Care; Effective Communication

- Recruiting/Retaining Qualified Clinicians

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

Medicaid Expansion- many of the 11.4M newly insured lives under the ACA have moved into Medicaid. Only about 1/3 of providers now accept Medicaid- 1 in 5 covered persons now have Medicaid, nearly 20% increase since 2013.

Bundled Payments- Majority of savings opportunity lies in Post-Acute Care. Awardee and Convener make profit is total cost is less than 98% of Target Price. In gainsharing agreements individuals can be reimbursed up to 150% usual Medicare rate. Pay occurs in usual Medicare fashion but is reconciled 60-90 days after end of bundle. For more information: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

Effective HM Groups- Three important areas for focus when beginning to address group performance are: engaged hospitalists, planning and management infrastructure, care coordination across settings. These three topics have broad reaching implications into the hospitalist practice and patient care. [Cawley P, et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2014; 9(2):123-128]

HM15 Presenters: Roy Sittig MD SFHM, Jeffrey Frank MD MBA, Jodi Braun

Summation: Speakers covered timely topics regarding the Accountable Care Act, namely Medicaid Expansion and Bundled Payment arrangements; and reviewed the seminal paper on “Key Principals and Characteristics of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group” and lessons learned in implementing those 10 Key Principles.

Medicaid Expansion: EDs serving the 29 Medicaid expansion states are reporting higher volumes, likely due to 11.4million new lives now insured under the ACA. While the ACA does provide for higher Medicaid payment rates thus far, only 34% of providers accept Medicaid, a 21% drop since the ACA went into effect.

Bundled Payment Arrangements:

- Bundled Payment Care Initiative (BPCI) lexicon:

- Model 2-Episode Anchor (anchor admission) AND 90days post d/c; Medicare pays 98% of usual cost

- Model 3-90days post d/c AFTER anchor admission; Medicare pays 97% of usual cost

- Convener-entity that brings providers together and enters into CMS agreement to bear risk for bundles

- Awardee (entity having agreement with Medicare to assume risk and receive payment via BPCI) and Convener own the Bundle

- Episode initiator (EI) triggers “bundle period”

- Bundles based on DRG

10-Key Principles of an Effective Hospitalist Medicine Group:

- Effective Leadership

- Engaged Hospitalists

- Adequate Resources

- Planning and Management Infrastructure

- Alignment with Hospital/Health System

- Care Coordination Across Settings

- Leadership in Key Clinical Issues in the Hospital/Health System

- Thoughtful Approach to Scope of Activity

- Patient/Family-Centered, Team-Based Care; Effective Communication

- Recruiting/Retaining Qualified Clinicians

Key Points/HM Takeaways:

Medicaid Expansion- many of the 11.4M newly insured lives under the ACA have moved into Medicaid. Only about 1/3 of providers now accept Medicaid- 1 in 5 covered persons now have Medicaid, nearly 20% increase since 2013.

Bundled Payments- Majority of savings opportunity lies in Post-Acute Care. Awardee and Convener make profit is total cost is less than 98% of Target Price. In gainsharing agreements individuals can be reimbursed up to 150% usual Medicare rate. Pay occurs in usual Medicare fashion but is reconciled 60-90 days after end of bundle. For more information: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

Effective HM Groups- Three important areas for focus when beginning to address group performance are: engaged hospitalists, planning and management infrastructure, care coordination across settings. These three topics have broad reaching implications into the hospitalist practice and patient care. [Cawley P, et al. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2014; 9(2):123-128]

Choosing Wisely in Hospital Medicine: Accomplishments and What the Future Holds

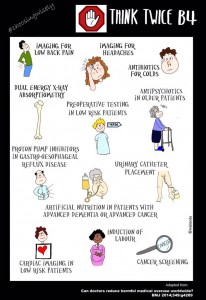

John Bulger, DO, MBA reviewed the components of the Choosing Wisely campaign and SHM’s recommendations in an era where providing high value cost-conscious care is key to optimizing the health of our patients. Choosing Wisely is an initiative of the ABIM foundation to foster communication between physicians and patients about common tests and procedures that may fail to provide value or enhance patient outcomes. It’s a partnership with 70-plus medical societies including an innovative partnership with Consumer Reports. SHM’s evidence-based recommendations are:

- Don’t leave urinary catheters in place for convenience or monitoring of output for non-critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe stress ulcer prophylaxis to hospitalized patients unless they are at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusion of PRBC for arbitrary hemoglobin in the absence of CAD, CHF or CVA.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without a protocol.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in a clinically stable patient.

Dr. Bulger highlighted that the Choosing Wisely campaign is designed to encourage conversations to

Dr.Bulger concluded that while tradition is hard to change, it is of paramount importance to think differently to find innovative solutions to common problems in healthcare. Join the conversation using #ChoosingWisely or #LessIsMore on twitter.

Key Takeaways

- Choosing Wisely is an ABIM campaign developed to address and promote conversations about common tests and procedures that are of low-value.

- SHM’s recommendations were implemented in institutions with positive results as evidenced by the Choosing Wisely case competition at #HospMed15.

- Look for a summary of these efforts to be published in the spring of 2015.

- Use these guidelines to educate, provoke dialogue and achieve optimal patient outcomes in your institution.

- Join the conversation on twitter using #ChoosingWisely and #LessIsMore.

John Bulger, DO, MBA reviewed the components of the Choosing Wisely campaign and SHM’s recommendations in an era where providing high value cost-conscious care is key to optimizing the health of our patients. Choosing Wisely is an initiative of the ABIM foundation to foster communication between physicians and patients about common tests and procedures that may fail to provide value or enhance patient outcomes. It’s a partnership with 70-plus medical societies including an innovative partnership with Consumer Reports. SHM’s evidence-based recommendations are:

- Don’t leave urinary catheters in place for convenience or monitoring of output for non-critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe stress ulcer prophylaxis to hospitalized patients unless they are at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusion of PRBC for arbitrary hemoglobin in the absence of CAD, CHF or CVA.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without a protocol.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in a clinically stable patient.

Dr. Bulger highlighted that the Choosing Wisely campaign is designed to encourage conversations to

Dr.Bulger concluded that while tradition is hard to change, it is of paramount importance to think differently to find innovative solutions to common problems in healthcare. Join the conversation using #ChoosingWisely or #LessIsMore on twitter.

Key Takeaways

- Choosing Wisely is an ABIM campaign developed to address and promote conversations about common tests and procedures that are of low-value.

- SHM’s recommendations were implemented in institutions with positive results as evidenced by the Choosing Wisely case competition at #HospMed15.

- Look for a summary of these efforts to be published in the spring of 2015.

- Use these guidelines to educate, provoke dialogue and achieve optimal patient outcomes in your institution.

- Join the conversation on twitter using #ChoosingWisely and #LessIsMore.

John Bulger, DO, MBA reviewed the components of the Choosing Wisely campaign and SHM’s recommendations in an era where providing high value cost-conscious care is key to optimizing the health of our patients. Choosing Wisely is an initiative of the ABIM foundation to foster communication between physicians and patients about common tests and procedures that may fail to provide value or enhance patient outcomes. It’s a partnership with 70-plus medical societies including an innovative partnership with Consumer Reports. SHM’s evidence-based recommendations are:

- Don’t leave urinary catheters in place for convenience or monitoring of output for non-critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe stress ulcer prophylaxis to hospitalized patients unless they are at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusion of PRBC for arbitrary hemoglobin in the absence of CAD, CHF or CVA.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without a protocol.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in a clinically stable patient.

Dr. Bulger highlighted that the Choosing Wisely campaign is designed to encourage conversations to

Dr.Bulger concluded that while tradition is hard to change, it is of paramount importance to think differently to find innovative solutions to common problems in healthcare. Join the conversation using #ChoosingWisely or #LessIsMore on twitter.

Key Takeaways

- Choosing Wisely is an ABIM campaign developed to address and promote conversations about common tests and procedures that are of low-value.

- SHM’s recommendations were implemented in institutions with positive results as evidenced by the Choosing Wisely case competition at #HospMed15.

- Look for a summary of these efforts to be published in the spring of 2015.

- Use these guidelines to educate, provoke dialogue and achieve optimal patient outcomes in your institution.

- Join the conversation on twitter using #ChoosingWisely and #LessIsMore.

Educational Opportunities for Hospitalists Beyond HM15

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Whether you’re packing your bags for HM15 or following from afar, there are plenty of other opportunities to get the most up to date clinical, management, and quality improvement information in the specialty:

- Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Get the managerial confidence you need to take your hospital medicine career to the next level. All three Leadership Academy courses will be offered in what’s now called the “Live Music Capital of the World.” www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

- Quality and Safety Educators Academy

May 7-9

Tempe, Ariz.

Medical students and residents are turning to hospitalists to learn about quality improvement and patient safety. The Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA) is a great way to stay up to speed on the latest knowledge and tools to teach quality improvement. www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea

- Project BOOST

Ongoing Applications

Have you thought about enrolling your hospital in SHM’s award-winning Project BOOST only to find that you missed the enrollment deadline? SHM has now made Project BOOST’s application process more flexible by accepting rolling applications throughout the year. www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost

- ABIM Maintenance of Certification

Deadline is August 1

Now is the time to start planning to enroll in the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Maintenance of Certification program. The enrollment deadline for the Fall 2015 exam is August 1, but don’t wait until the end of July to get started! http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/moc

Society of Hospital Medicine's Quality Improvement Module Approved for ABIM Maintenance of Certification

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

If you’re among the many physicians enrolled in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program, you have to earn a combined 100 points in medical knowledge and practice improvement throughout your 10-year certificate period. SHM wants to help you with this process.

SHM is pleased to announce that the ABIM has approved SHM’s Hospital Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module for credit in the ABIM MOC program.

Take the QI and Patient Safety Medical Knowledge Module and many other online courses—free for members—at www.shmlearningportal.org.

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine EVP Explains Hospitalists' Important Role in End-of-Life Planning

Click here for excerpts of our interview with Porter Storey, MD, executive vice president of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Click here for excerpts of our interview with Porter Storey, MD, executive vice president of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Click here for excerpts of our interview with Porter Storey, MD, executive vice president of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

SHM’s Online Community Easy to Access, Use

HMX in 3 Minutes or Less

More than 2,500 hospitalists have logged into HMX to share their experiences and ask questions on a wide variety of topics, from HM group practice management to clinical details about glycemic control.

New communities are being added regularly, so be sure to set up your account, sign up for customizable e-mail notifications, and check back regularly to follow your favorite discussions.

Have a question or idea for other hospitalists? Share it today.

Here’s how to get started. All you need are your SHM login credentials.

- Go to www.hmxchange.org.

- In the top right-hand corner, click the link that reads, “Login to see members only content.”

- Enter your SHM login credentials and click login.

- Now you’re logged in. On the right-hand side, you will find a box with a list of the various communities. Click on the community you would like to view and/or post in.

- Click the “Discussions” tab and, on the right, click the square button that says “+ Post New Message.”

- Compose your message with subject and body (and you can include an attachment if you want).

- Click “Send.”

Hospitalists can now follow their favorite discussions on the go with the Member Centric app for HMX.

- Go to your preferred app store and download “MemberCentric.”

- Search for “Society of Hospital Medicine” in the list of organizations.

- Log in with your SHM/HMX username and password.

- Get access to your discussions, contacts, private message inbox, and events calendar.

HMX in 3 Minutes or Less

More than 2,500 hospitalists have logged into HMX to share their experiences and ask questions on a wide variety of topics, from HM group practice management to clinical details about glycemic control.

New communities are being added regularly, so be sure to set up your account, sign up for customizable e-mail notifications, and check back regularly to follow your favorite discussions.

Have a question or idea for other hospitalists? Share it today.

Here’s how to get started. All you need are your SHM login credentials.

- Go to www.hmxchange.org.

- In the top right-hand corner, click the link that reads, “Login to see members only content.”

- Enter your SHM login credentials and click login.

- Now you’re logged in. On the right-hand side, you will find a box with a list of the various communities. Click on the community you would like to view and/or post in.

- Click the “Discussions” tab and, on the right, click the square button that says “+ Post New Message.”

- Compose your message with subject and body (and you can include an attachment if you want).

- Click “Send.”

Hospitalists can now follow their favorite discussions on the go with the Member Centric app for HMX.

- Go to your preferred app store and download “MemberCentric.”

- Search for “Society of Hospital Medicine” in the list of organizations.

- Log in with your SHM/HMX username and password.

- Get access to your discussions, contacts, private message inbox, and events calendar.

HMX in 3 Minutes or Less

More than 2,500 hospitalists have logged into HMX to share their experiences and ask questions on a wide variety of topics, from HM group practice management to clinical details about glycemic control.

New communities are being added regularly, so be sure to set up your account, sign up for customizable e-mail notifications, and check back regularly to follow your favorite discussions.

Have a question or idea for other hospitalists? Share it today.

Here’s how to get started. All you need are your SHM login credentials.

- Go to www.hmxchange.org.

- In the top right-hand corner, click the link that reads, “Login to see members only content.”

- Enter your SHM login credentials and click login.

- Now you’re logged in. On the right-hand side, you will find a box with a list of the various communities. Click on the community you would like to view and/or post in.

- Click the “Discussions” tab and, on the right, click the square button that says “+ Post New Message.”

- Compose your message with subject and body (and you can include an attachment if you want).

- Click “Send.”

Hospitalists can now follow their favorite discussions on the go with the Member Centric app for HMX.

- Go to your preferred app store and download “MemberCentric.”

- Search for “Society of Hospital Medicine” in the list of organizations.

- Log in with your SHM/HMX username and password.

- Get access to your discussions, contacts, private message inbox, and events calendar.

Hospitalists Outline Quality of Care Initiative for Inpatients with Atrial Fibrillation

SHM asked leaders of the Hospital-Based Quality Improvement in Stroke Prevention for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Project, Hiren Shah, MD, MBA, SFHM, and Andrew Masica, MD, SFHM, to provide an overview of the program.

“AF is a disease state that is highly prevalent, and the numbers are rising yearly. We also know that it is one of the most common inpatient diagnoses,” Dr. Shah says. “However, when you look at the quality of care provided to our AF patients, it is quite variable and has implications for other hospital performance metrics such as 30-day readmission rates. This makes AF a high-impact target for inpatient quality improvement initiatives.”

Dr. Shah is assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. Dr. Masica is vice president of clinical effectiveness at Baylor Health Care System in Dallas.

The implementation guide for SHM’s AF project will be available later in December at www.hospitalmedicine.org/afib.

Question: What is the scope of your project?

Dr. Masica: That is a question we wrestled with. Numerous care processes related to AF are amenable to inpatient quality improvement. We chose to focus our efforts on stroke prevention in AF and the development of a toolkit to help hospital-based practitioners to assess stroke and bleeding risk consistently and, if indicated, to initiate antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Shah: Along those lines, we know that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care; however, current data indicate that only 50% to 60% of patients with AF who are eligible to receive antithrombotic therapy are on active stroke prophylaxis.

Q: Why do you think there are such large gaps in stroke prophylaxis for AF patients?

Dr. Masica: The prophylaxis decision requires the clinician to do an anticoagulation net-benefit and risk assessment, and although there are validated tools to do this type of assessment, use of these tools hasn’t yet become hardwired into daily hospital practice. Empiric clinical assessments often overestimate the bleed risk and underestimate stroke risk, so the ultimate result can be underuse of antithrombotic therapy.

–Dr. Shah

Dr. Shah: Another barrier is that in many hospitals, there are not reminders in place in our workflow for this assessment to happen at all. Hospitalists may think that the anticoagulation decision is an outpatient issue, better addressed by their primary care doctor, so it is sometimes even intentionally bypassed. Another barrier is that it takes time to discuss a patient’s values and preferences in the anticoagulation decision.

Q: But isn’t stroke prevention in AF more of an outpatient issue?

Dr. Shah: We think the hospital is a great place to start this evaluation and to make the anticoagulation decision. Of course, we should discuss these issues with the primary care doctor. Ideally, we would like to start anticoagulation during the hospital stay or on discharge, if indicated, but even if we clearly communicate a patient’s stroke and bleed risk to the PCP on discharge, we can help ensure that this issue will be addressed on outpatient follow-up.

Q: What specific tools for stroke and bleed risk are you referring to?

Dr. Shah: The CHADS2 scoring system is a well-validated tool for estimating the risk of stroke in AF patients, one that most clinicians may be aware of. The CHA2DS2-VASc is a slightly more refined scoring system. When it comes to bleeding, however, fewer clinicians are aware of the HAS-BLED bleeding risk assessment method.

Dr. Masica: The scoring systems represent a consistent, reproducible approach by which to evaluate inpatients with AF. Of course, there is some discretion for other patient-specific factors (e.g. fall risk) that are not captured in the scoring systems, but they are good starting points in the decision-making process. Finally and most importantly, although it is often overlooked, shared decision-making should take place with the patients, because their values in facing the risk of stroke versus bleeding often tip the balance one way or the other.

Q: How will the project help hospitals in this process?

Dr. Shah: We have written a QI Implementation Guide for hospitals with tools intended to improve the care of patients with AF in the hospital setting. This book will be similar to SHM’s VTE Prevention Implementation Guide, published a few years ago. We also will have an upcoming AF QI resource room within the SHM website. Additionally, similar to VTE, there are likely to be future mentored implementation projects where we will be working directly with hospitals and coaching them in this initiative.

Dr. Masica: We also have given a recent SHM-sponsored webinar that outlines some content of the guide. It can be accessed on the SHM website. This webinar reviews how to start a QI project in AF, assess your current state of care, build an interdisciplinary team, use validated tools, and deploy interventions to help make the stroke risk assessment and prophylaxis decision. I would note that the intended audience for these tools is broad and includes frontline hospitalists, QI directors, CMOs, and COOs, as well as nursing leadership, NPs, PAs, pharmacists, and other care providers.

Q: Does healthcare reform impact your efforts in this area?

Dr. Shah: Value-based purchasing, preventing readmissions, accountable care organizations, and bundled payments are all aspects of reform that will involve this therapeutic area, as their scope will impact the quality of care we deliver, how our cost structures are, and how we improve fragmentation of care across care transitions.

Dr. Masica: In addition, market forces, healthcare legislation, conceptual shifts regarding the need for systematic approaches to healthcare improvement, and new rules that may impact hospital reimbursement will continue to make AF an important healthcare quality issue. Thus, we think the discussion around delivering patient-centered care in AF is really just beginning.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

SHM asked leaders of the Hospital-Based Quality Improvement in Stroke Prevention for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Project, Hiren Shah, MD, MBA, SFHM, and Andrew Masica, MD, SFHM, to provide an overview of the program.

“AF is a disease state that is highly prevalent, and the numbers are rising yearly. We also know that it is one of the most common inpatient diagnoses,” Dr. Shah says. “However, when you look at the quality of care provided to our AF patients, it is quite variable and has implications for other hospital performance metrics such as 30-day readmission rates. This makes AF a high-impact target for inpatient quality improvement initiatives.”

Dr. Shah is assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. Dr. Masica is vice president of clinical effectiveness at Baylor Health Care System in Dallas.

The implementation guide for SHM’s AF project will be available later in December at www.hospitalmedicine.org/afib.

Question: What is the scope of your project?

Dr. Masica: That is a question we wrestled with. Numerous care processes related to AF are amenable to inpatient quality improvement. We chose to focus our efforts on stroke prevention in AF and the development of a toolkit to help hospital-based practitioners to assess stroke and bleeding risk consistently and, if indicated, to initiate antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Shah: Along those lines, we know that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care; however, current data indicate that only 50% to 60% of patients with AF who are eligible to receive antithrombotic therapy are on active stroke prophylaxis.

Q: Why do you think there are such large gaps in stroke prophylaxis for AF patients?

Dr. Masica: The prophylaxis decision requires the clinician to do an anticoagulation net-benefit and risk assessment, and although there are validated tools to do this type of assessment, use of these tools hasn’t yet become hardwired into daily hospital practice. Empiric clinical assessments often overestimate the bleed risk and underestimate stroke risk, so the ultimate result can be underuse of antithrombotic therapy.

–Dr. Shah

Dr. Shah: Another barrier is that in many hospitals, there are not reminders in place in our workflow for this assessment to happen at all. Hospitalists may think that the anticoagulation decision is an outpatient issue, better addressed by their primary care doctor, so it is sometimes even intentionally bypassed. Another barrier is that it takes time to discuss a patient’s values and preferences in the anticoagulation decision.

Q: But isn’t stroke prevention in AF more of an outpatient issue?

Dr. Shah: We think the hospital is a great place to start this evaluation and to make the anticoagulation decision. Of course, we should discuss these issues with the primary care doctor. Ideally, we would like to start anticoagulation during the hospital stay or on discharge, if indicated, but even if we clearly communicate a patient’s stroke and bleed risk to the PCP on discharge, we can help ensure that this issue will be addressed on outpatient follow-up.

Q: What specific tools for stroke and bleed risk are you referring to?

Dr. Shah: The CHADS2 scoring system is a well-validated tool for estimating the risk of stroke in AF patients, one that most clinicians may be aware of. The CHA2DS2-VASc is a slightly more refined scoring system. When it comes to bleeding, however, fewer clinicians are aware of the HAS-BLED bleeding risk assessment method.

Dr. Masica: The scoring systems represent a consistent, reproducible approach by which to evaluate inpatients with AF. Of course, there is some discretion for other patient-specific factors (e.g. fall risk) that are not captured in the scoring systems, but they are good starting points in the decision-making process. Finally and most importantly, although it is often overlooked, shared decision-making should take place with the patients, because their values in facing the risk of stroke versus bleeding often tip the balance one way or the other.

Q: How will the project help hospitals in this process?

Dr. Shah: We have written a QI Implementation Guide for hospitals with tools intended to improve the care of patients with AF in the hospital setting. This book will be similar to SHM’s VTE Prevention Implementation Guide, published a few years ago. We also will have an upcoming AF QI resource room within the SHM website. Additionally, similar to VTE, there are likely to be future mentored implementation projects where we will be working directly with hospitals and coaching them in this initiative.

Dr. Masica: We also have given a recent SHM-sponsored webinar that outlines some content of the guide. It can be accessed on the SHM website. This webinar reviews how to start a QI project in AF, assess your current state of care, build an interdisciplinary team, use validated tools, and deploy interventions to help make the stroke risk assessment and prophylaxis decision. I would note that the intended audience for these tools is broad and includes frontline hospitalists, QI directors, CMOs, and COOs, as well as nursing leadership, NPs, PAs, pharmacists, and other care providers.

Q: Does healthcare reform impact your efforts in this area?

Dr. Shah: Value-based purchasing, preventing readmissions, accountable care organizations, and bundled payments are all aspects of reform that will involve this therapeutic area, as their scope will impact the quality of care we deliver, how our cost structures are, and how we improve fragmentation of care across care transitions.

Dr. Masica: In addition, market forces, healthcare legislation, conceptual shifts regarding the need for systematic approaches to healthcare improvement, and new rules that may impact hospital reimbursement will continue to make AF an important healthcare quality issue. Thus, we think the discussion around delivering patient-centered care in AF is really just beginning.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

SHM asked leaders of the Hospital-Based Quality Improvement in Stroke Prevention for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Project, Hiren Shah, MD, MBA, SFHM, and Andrew Masica, MD, SFHM, to provide an overview of the program.

“AF is a disease state that is highly prevalent, and the numbers are rising yearly. We also know that it is one of the most common inpatient diagnoses,” Dr. Shah says. “However, when you look at the quality of care provided to our AF patients, it is quite variable and has implications for other hospital performance metrics such as 30-day readmission rates. This makes AF a high-impact target for inpatient quality improvement initiatives.”

Dr. Shah is assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and medical director at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. Dr. Masica is vice president of clinical effectiveness at Baylor Health Care System in Dallas.

The implementation guide for SHM’s AF project will be available later in December at www.hospitalmedicine.org/afib.

Question: What is the scope of your project?

Dr. Masica: That is a question we wrestled with. Numerous care processes related to AF are amenable to inpatient quality improvement. We chose to focus our efforts on stroke prevention in AF and the development of a toolkit to help hospital-based practitioners to assess stroke and bleeding risk consistently and, if indicated, to initiate antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Shah: Along those lines, we know that at least 25% of AF-related strokes are potentially preventable with adherence to evidence-based care; however, current data indicate that only 50% to 60% of patients with AF who are eligible to receive antithrombotic therapy are on active stroke prophylaxis.

Q: Why do you think there are such large gaps in stroke prophylaxis for AF patients?

Dr. Masica: The prophylaxis decision requires the clinician to do an anticoagulation net-benefit and risk assessment, and although there are validated tools to do this type of assessment, use of these tools hasn’t yet become hardwired into daily hospital practice. Empiric clinical assessments often overestimate the bleed risk and underestimate stroke risk, so the ultimate result can be underuse of antithrombotic therapy.

–Dr. Shah

Dr. Shah: Another barrier is that in many hospitals, there are not reminders in place in our workflow for this assessment to happen at all. Hospitalists may think that the anticoagulation decision is an outpatient issue, better addressed by their primary care doctor, so it is sometimes even intentionally bypassed. Another barrier is that it takes time to discuss a patient’s values and preferences in the anticoagulation decision.

Q: But isn’t stroke prevention in AF more of an outpatient issue?

Dr. Shah: We think the hospital is a great place to start this evaluation and to make the anticoagulation decision. Of course, we should discuss these issues with the primary care doctor. Ideally, we would like to start anticoagulation during the hospital stay or on discharge, if indicated, but even if we clearly communicate a patient’s stroke and bleed risk to the PCP on discharge, we can help ensure that this issue will be addressed on outpatient follow-up.

Q: What specific tools for stroke and bleed risk are you referring to?

Dr. Shah: The CHADS2 scoring system is a well-validated tool for estimating the risk of stroke in AF patients, one that most clinicians may be aware of. The CHA2DS2-VASc is a slightly more refined scoring system. When it comes to bleeding, however, fewer clinicians are aware of the HAS-BLED bleeding risk assessment method.

Dr. Masica: The scoring systems represent a consistent, reproducible approach by which to evaluate inpatients with AF. Of course, there is some discretion for other patient-specific factors (e.g. fall risk) that are not captured in the scoring systems, but they are good starting points in the decision-making process. Finally and most importantly, although it is often overlooked, shared decision-making should take place with the patients, because their values in facing the risk of stroke versus bleeding often tip the balance one way or the other.

Q: How will the project help hospitals in this process?

Dr. Shah: We have written a QI Implementation Guide for hospitals with tools intended to improve the care of patients with AF in the hospital setting. This book will be similar to SHM’s VTE Prevention Implementation Guide, published a few years ago. We also will have an upcoming AF QI resource room within the SHM website. Additionally, similar to VTE, there are likely to be future mentored implementation projects where we will be working directly with hospitals and coaching them in this initiative.