User login

MELD 3.0 Reduces Sex-Based Liver Transplant Disparities

SAN DIEGO — , according to new research.

In particular, women are now more likely to be added to the waitlist for a liver transplant, more likely to receive a transplant, and less likely to fall off the waitlist because of death.

“MELD 3.0 improved access to transplantation for women, and now waitlist mortality and transplant rates for women more closely approximate the rates for men,” said lead author Allison Kwong, MD, assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford Medicine in California.

“Overall transplant outcomes have also improved year over year,” said Kwong, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Changes in MELD and Transplant Numbers

MELD, which estimates liver failure severity and short-term survival in patients with chronic liver disease, has been used since 2002 to determine organ allocation priority for patients in the United States awaiting liver transplantation. Originally, the score incorporated three variables: creatinine, bilirubin, and the international normalized ratio (INR). MELDNa1, or MELD 2.0, was adopted in 2016 to add sodium.

“Under this system, however, there have been sex-based disparities” with women receiving lower priority scores despite similar disease severity, said Kwong.

“This has been attributed to several factors, such as the creatinine term in the MELD score underestimating renal dysfunction in women, height and body size differences, and differences in disease etiology, and how we’ve assigned exception points historically,” she reported.

Men have had a lower pretransplant mortality rate and higher deceased donor transplant rates, she added.

MELD 3.0 was developed to address these gender differences and other determinants of waitlist outcomes. The updated equation added 1.33 points for women, as well as adding other variables, such as albumin, interactions between bilirubin and sodium, and interactions between albumin and creatinine, to increase prediction accuracy.

To observe the effects of the new system, Kwong and colleagues analyzed OPTN data for patients aged 12 years or older, focusing on the records of more than 20,300 newly registered liver transplant candidates, and about 18,700 transplant recipients, during the 12 months before and 12 months after MELD 3.0 was implemented.

After the switch, 43.7% of newly registered liver transplant candidates were women, compared with 40.4% before the switch. At registration, the median age was 55, both before and after the change in policy, and the median MELD score changed from 23 to 22 after implementation.

In addition, 42.1% of transplants occurred among women after MELD 3.0 implementation, as compared with 37.3% before. Overall, deceased donor transplant rates were similar for men and women after MELD 3.0 implementation.

The 90-day waitlist dropout rate — patients who died or became too sick to receive a transplant — decreased from 13.5% to 9.1% among women, which may be partially attributable to MELD 3.0, said Kwong.

However, waitlist dropout rates also decreased among men, from 9.8% to 7.4%, probably because of improvements in technology, such as machine perfusion, which have increased the number of available livers, she added.

Disparities Continue to Exist

Some disparities still exist. Although the total median MELD score at transplant decreased from 29 to 27, women still had a higher median score of 29 at transplant, compared with a median score of 27 among men.

“This indicates that there may still be differences in transplant access between the sexes,” Kwong said. “There are still body size differences that can affect the probability of transplant, and this would not be addressed by MELD 3.0.”

Additional transplant disparities exist related to other patient characteristics, such as age, race, and ethnicity.

Future versions of MELD could potentially consider these factors, said session moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, PhD, MBA, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and secretary general of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2023-2025.

“There are infinite versions of MELD that can be made,” Kwong said. “It’s still early to see how MELD 3.0 will serve the system, but so far, so good.”

In a comment, Tamar Taddei, MD, professor of medicine in digestive diseases at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, who comoderated the session, noted the importance of using a MELD score that considers sex-based differences.

This study brings MELD 3.0 to its fruition by reducing the disparities experienced by women who were underserved by the previous scoring systems, she said.

It was lovely to see that MELD 3.0 reduced the disparities with transplants, and also that the waitlist dropout was reduced — for both men and women,” Taddei said. “This change is a no-brainer.”

Kwong, Krag, and Taddei reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , according to new research.

In particular, women are now more likely to be added to the waitlist for a liver transplant, more likely to receive a transplant, and less likely to fall off the waitlist because of death.

“MELD 3.0 improved access to transplantation for women, and now waitlist mortality and transplant rates for women more closely approximate the rates for men,” said lead author Allison Kwong, MD, assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford Medicine in California.

“Overall transplant outcomes have also improved year over year,” said Kwong, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Changes in MELD and Transplant Numbers

MELD, which estimates liver failure severity and short-term survival in patients with chronic liver disease, has been used since 2002 to determine organ allocation priority for patients in the United States awaiting liver transplantation. Originally, the score incorporated three variables: creatinine, bilirubin, and the international normalized ratio (INR). MELDNa1, or MELD 2.0, was adopted in 2016 to add sodium.

“Under this system, however, there have been sex-based disparities” with women receiving lower priority scores despite similar disease severity, said Kwong.

“This has been attributed to several factors, such as the creatinine term in the MELD score underestimating renal dysfunction in women, height and body size differences, and differences in disease etiology, and how we’ve assigned exception points historically,” she reported.

Men have had a lower pretransplant mortality rate and higher deceased donor transplant rates, she added.

MELD 3.0 was developed to address these gender differences and other determinants of waitlist outcomes. The updated equation added 1.33 points for women, as well as adding other variables, such as albumin, interactions between bilirubin and sodium, and interactions between albumin and creatinine, to increase prediction accuracy.

To observe the effects of the new system, Kwong and colleagues analyzed OPTN data for patients aged 12 years or older, focusing on the records of more than 20,300 newly registered liver transplant candidates, and about 18,700 transplant recipients, during the 12 months before and 12 months after MELD 3.0 was implemented.

After the switch, 43.7% of newly registered liver transplant candidates were women, compared with 40.4% before the switch. At registration, the median age was 55, both before and after the change in policy, and the median MELD score changed from 23 to 22 after implementation.

In addition, 42.1% of transplants occurred among women after MELD 3.0 implementation, as compared with 37.3% before. Overall, deceased donor transplant rates were similar for men and women after MELD 3.0 implementation.

The 90-day waitlist dropout rate — patients who died or became too sick to receive a transplant — decreased from 13.5% to 9.1% among women, which may be partially attributable to MELD 3.0, said Kwong.

However, waitlist dropout rates also decreased among men, from 9.8% to 7.4%, probably because of improvements in technology, such as machine perfusion, which have increased the number of available livers, she added.

Disparities Continue to Exist

Some disparities still exist. Although the total median MELD score at transplant decreased from 29 to 27, women still had a higher median score of 29 at transplant, compared with a median score of 27 among men.

“This indicates that there may still be differences in transplant access between the sexes,” Kwong said. “There are still body size differences that can affect the probability of transplant, and this would not be addressed by MELD 3.0.”

Additional transplant disparities exist related to other patient characteristics, such as age, race, and ethnicity.

Future versions of MELD could potentially consider these factors, said session moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, PhD, MBA, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and secretary general of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2023-2025.

“There are infinite versions of MELD that can be made,” Kwong said. “It’s still early to see how MELD 3.0 will serve the system, but so far, so good.”

In a comment, Tamar Taddei, MD, professor of medicine in digestive diseases at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, who comoderated the session, noted the importance of using a MELD score that considers sex-based differences.

This study brings MELD 3.0 to its fruition by reducing the disparities experienced by women who were underserved by the previous scoring systems, she said.

It was lovely to see that MELD 3.0 reduced the disparities with transplants, and also that the waitlist dropout was reduced — for both men and women,” Taddei said. “This change is a no-brainer.”

Kwong, Krag, and Taddei reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , according to new research.

In particular, women are now more likely to be added to the waitlist for a liver transplant, more likely to receive a transplant, and less likely to fall off the waitlist because of death.

“MELD 3.0 improved access to transplantation for women, and now waitlist mortality and transplant rates for women more closely approximate the rates for men,” said lead author Allison Kwong, MD, assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford Medicine in California.

“Overall transplant outcomes have also improved year over year,” said Kwong, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Changes in MELD and Transplant Numbers

MELD, which estimates liver failure severity and short-term survival in patients with chronic liver disease, has been used since 2002 to determine organ allocation priority for patients in the United States awaiting liver transplantation. Originally, the score incorporated three variables: creatinine, bilirubin, and the international normalized ratio (INR). MELDNa1, or MELD 2.0, was adopted in 2016 to add sodium.

“Under this system, however, there have been sex-based disparities” with women receiving lower priority scores despite similar disease severity, said Kwong.

“This has been attributed to several factors, such as the creatinine term in the MELD score underestimating renal dysfunction in women, height and body size differences, and differences in disease etiology, and how we’ve assigned exception points historically,” she reported.

Men have had a lower pretransplant mortality rate and higher deceased donor transplant rates, she added.

MELD 3.0 was developed to address these gender differences and other determinants of waitlist outcomes. The updated equation added 1.33 points for women, as well as adding other variables, such as albumin, interactions between bilirubin and sodium, and interactions between albumin and creatinine, to increase prediction accuracy.

To observe the effects of the new system, Kwong and colleagues analyzed OPTN data for patients aged 12 years or older, focusing on the records of more than 20,300 newly registered liver transplant candidates, and about 18,700 transplant recipients, during the 12 months before and 12 months after MELD 3.0 was implemented.

After the switch, 43.7% of newly registered liver transplant candidates were women, compared with 40.4% before the switch. At registration, the median age was 55, both before and after the change in policy, and the median MELD score changed from 23 to 22 after implementation.

In addition, 42.1% of transplants occurred among women after MELD 3.0 implementation, as compared with 37.3% before. Overall, deceased donor transplant rates were similar for men and women after MELD 3.0 implementation.

The 90-day waitlist dropout rate — patients who died or became too sick to receive a transplant — decreased from 13.5% to 9.1% among women, which may be partially attributable to MELD 3.0, said Kwong.

However, waitlist dropout rates also decreased among men, from 9.8% to 7.4%, probably because of improvements in technology, such as machine perfusion, which have increased the number of available livers, she added.

Disparities Continue to Exist

Some disparities still exist. Although the total median MELD score at transplant decreased from 29 to 27, women still had a higher median score of 29 at transplant, compared with a median score of 27 among men.

“This indicates that there may still be differences in transplant access between the sexes,” Kwong said. “There are still body size differences that can affect the probability of transplant, and this would not be addressed by MELD 3.0.”

Additional transplant disparities exist related to other patient characteristics, such as age, race, and ethnicity.

Future versions of MELD could potentially consider these factors, said session moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, PhD, MBA, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and secretary general of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2023-2025.

“There are infinite versions of MELD that can be made,” Kwong said. “It’s still early to see how MELD 3.0 will serve the system, but so far, so good.”

In a comment, Tamar Taddei, MD, professor of medicine in digestive diseases at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, who comoderated the session, noted the importance of using a MELD score that considers sex-based differences.

This study brings MELD 3.0 to its fruition by reducing the disparities experienced by women who were underserved by the previous scoring systems, she said.

It was lovely to see that MELD 3.0 reduced the disparities with transplants, and also that the waitlist dropout was reduced — for both men and women,” Taddei said. “This change is a no-brainer.”

Kwong, Krag, and Taddei reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AASLD 24

‘Watershed Moment’: Semaglutide Shown to Be Effective in MASH

SAN DIEGO — according to interim results from a phase 3 trial.

At 72 weeks, a 2.4-mg once-weekly subcutaneous dose of semaglutide demonstrated superiority, compared with placebo, for the two primary endpoints: Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis and improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis.

“It’s been a long journey. I’ve been working with GLP-1s for 16 years, and it’s great to be able to report the first GLP-1 receptor agonist to demonstrate efficacy in a phase 3 trial for MASH,” said lead author Philip Newsome, MD, PhD, director of the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College London in England.

“There were also improvements in a slew of other noninvasive markers,” said Newsome, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Although already seen in a broader context, “it’s nice to see a demonstration of the cardiometabolic benefits in the context of MASH and a reassuring safety profile,” he added.

Interim ESSENCE Trial Analysis

ESSENCE (NCT04822181) is an ongoing multicenter, phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outcome trial studying semaglutide for the potential treatment of MASH.

The trial includes 1200 participants with biopsy-defined MASH and fibrosis, stages F2 and F3, who were randomized 2:1 to a once-weekly subcutaneous injection of 2.4 mg of semaglutide or placebo for 240 weeks. After initiation, the semaglutide dosage was increased every 4 weeks up to 16 weeks when the full dose (2.4 mg) was reached.

In a planned interim analysis, the trial investigators evaluated the primary endpoints at week 72 for the first 800 participants, with biopsies taken at weeks 1 and 72.

A total of 534 people were randomized to the semaglutide group, including 169 with F2 fibrosis and 365 with F3 fibrosis. Among the 266 participants randomized to placebo, 81 had F2 fibrosis and 185 had F3 fibrosis.

At baseline, the patient characteristics were similar between the groups (mean age, 56 years; body mass index, 34.6). A majority of participants also were White (67.5%), women (57.1%), had type 2 diabetes (55.9%), F3 fibrosis (68.8%), and enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) scores around 10 (55.5%).

For the first primary endpoint, 62.9% of those in the semaglutide group and 34.1% of those in the placebo group reached resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis. This represented an estimated difference in responder proportions (EDP) of 28.9%.

In addition, 37% of those in the semaglutide group and 22.5% of those in the placebo group met the second primary endpoint of improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis (EDP, 14.4%).

Among the secondary endpoints, combined resolution of steatohepatitis with a one-stage improvement in liver fibrosis occurred in 32.8% of the semaglutide group and 16.2% of the placebo group (EDP, 16.6%).

In additional analyses, Newsome and colleagues found 20%-40% improvements in liver enzymes and noninvasive fibrosis markers, such as ELF and vibration-controlled transient elastography liver stiffness.

Weight loss was also significant, with a 10.5% reduction in the semaglutide group compared with a 2% reduction in the placebo group.

Cardiometabolic risk factors improved as well, with changes in blood pressure measurements, hemoglobin A1c scores, and cholesterol values.

Although not considered statistically significant, patients in the semaglutide group also reported greater reductions in body pain.

In a safety analysis of 1195 participants at 96 weeks, adverse events, severe adverse events, and discontinuations were similar in both groups. Not surprisingly, gastrointestinal side effects were more commonly reported in the semaglutide group, Newsome said.

Highly Anticipated Results

After Newsome’s presentation, attendees applauded.

Rohit Loomba, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, called the results the “highlight of the meeting.”

This sentiment was echoed by Naga Chalasani, MD, AGAF, a gastroenterologist at Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis, who called the results a “watershed moment in the MASH field” with “terrific data.”

Based on questions after the presentation, Newsome indicated that future ESSENCE reports would look at certain aspects of the results, such as the 10% weight loss among those in the semaglutide group, as well as the mechanisms of histological and fibrosis improvement.

“We know from other GLP-1 trials that more weight loss occurs in those who don’t have type 2 diabetes, and we’re still running those analyses,” he said. “Weight loss is clearly a major contributor to MASH improvement, but there seem to be some weight-independent effects here, which are likely linked to insulin sensitivity or inflammation. We look forward to presenting those analyses in due course.”

In a comment, Kimberly Ann Brown, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, AASLD Foundation chair, and comoderator of the late-breaking abstract session, spoke about the highly anticipated presentation.

“This study was really the pinnacle of this meeting. We’ve all been waiting for this data, in large part because many of our patients are already using these medications,” Brown said. “Seeing the benefit for the liver, as well as lipids and other cardiovascular measures, is so important. Having this confirmatory study will hopefully lead to the availability of the medication for this indication among our patients.”

Newsome reported numerous disclosures, including consultant relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Loomba has research grant relationships with numerous companies, including Hanmi, Gilead, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Galectin Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Chalasani has consultant relationships with Ipsen, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, GSK, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, and Zydus. Brown reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — according to interim results from a phase 3 trial.

At 72 weeks, a 2.4-mg once-weekly subcutaneous dose of semaglutide demonstrated superiority, compared with placebo, for the two primary endpoints: Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis and improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis.

“It’s been a long journey. I’ve been working with GLP-1s for 16 years, and it’s great to be able to report the first GLP-1 receptor agonist to demonstrate efficacy in a phase 3 trial for MASH,” said lead author Philip Newsome, MD, PhD, director of the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College London in England.

“There were also improvements in a slew of other noninvasive markers,” said Newsome, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Although already seen in a broader context, “it’s nice to see a demonstration of the cardiometabolic benefits in the context of MASH and a reassuring safety profile,” he added.

Interim ESSENCE Trial Analysis

ESSENCE (NCT04822181) is an ongoing multicenter, phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outcome trial studying semaglutide for the potential treatment of MASH.

The trial includes 1200 participants with biopsy-defined MASH and fibrosis, stages F2 and F3, who were randomized 2:1 to a once-weekly subcutaneous injection of 2.4 mg of semaglutide or placebo for 240 weeks. After initiation, the semaglutide dosage was increased every 4 weeks up to 16 weeks when the full dose (2.4 mg) was reached.

In a planned interim analysis, the trial investigators evaluated the primary endpoints at week 72 for the first 800 participants, with biopsies taken at weeks 1 and 72.

A total of 534 people were randomized to the semaglutide group, including 169 with F2 fibrosis and 365 with F3 fibrosis. Among the 266 participants randomized to placebo, 81 had F2 fibrosis and 185 had F3 fibrosis.

At baseline, the patient characteristics were similar between the groups (mean age, 56 years; body mass index, 34.6). A majority of participants also were White (67.5%), women (57.1%), had type 2 diabetes (55.9%), F3 fibrosis (68.8%), and enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) scores around 10 (55.5%).

For the first primary endpoint, 62.9% of those in the semaglutide group and 34.1% of those in the placebo group reached resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis. This represented an estimated difference in responder proportions (EDP) of 28.9%.

In addition, 37% of those in the semaglutide group and 22.5% of those in the placebo group met the second primary endpoint of improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis (EDP, 14.4%).

Among the secondary endpoints, combined resolution of steatohepatitis with a one-stage improvement in liver fibrosis occurred in 32.8% of the semaglutide group and 16.2% of the placebo group (EDP, 16.6%).

In additional analyses, Newsome and colleagues found 20%-40% improvements in liver enzymes and noninvasive fibrosis markers, such as ELF and vibration-controlled transient elastography liver stiffness.

Weight loss was also significant, with a 10.5% reduction in the semaglutide group compared with a 2% reduction in the placebo group.

Cardiometabolic risk factors improved as well, with changes in blood pressure measurements, hemoglobin A1c scores, and cholesterol values.

Although not considered statistically significant, patients in the semaglutide group also reported greater reductions in body pain.

In a safety analysis of 1195 participants at 96 weeks, adverse events, severe adverse events, and discontinuations were similar in both groups. Not surprisingly, gastrointestinal side effects were more commonly reported in the semaglutide group, Newsome said.

Highly Anticipated Results

After Newsome’s presentation, attendees applauded.

Rohit Loomba, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, called the results the “highlight of the meeting.”

This sentiment was echoed by Naga Chalasani, MD, AGAF, a gastroenterologist at Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis, who called the results a “watershed moment in the MASH field” with “terrific data.”

Based on questions after the presentation, Newsome indicated that future ESSENCE reports would look at certain aspects of the results, such as the 10% weight loss among those in the semaglutide group, as well as the mechanisms of histological and fibrosis improvement.

“We know from other GLP-1 trials that more weight loss occurs in those who don’t have type 2 diabetes, and we’re still running those analyses,” he said. “Weight loss is clearly a major contributor to MASH improvement, but there seem to be some weight-independent effects here, which are likely linked to insulin sensitivity or inflammation. We look forward to presenting those analyses in due course.”

In a comment, Kimberly Ann Brown, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, AASLD Foundation chair, and comoderator of the late-breaking abstract session, spoke about the highly anticipated presentation.

“This study was really the pinnacle of this meeting. We’ve all been waiting for this data, in large part because many of our patients are already using these medications,” Brown said. “Seeing the benefit for the liver, as well as lipids and other cardiovascular measures, is so important. Having this confirmatory study will hopefully lead to the availability of the medication for this indication among our patients.”

Newsome reported numerous disclosures, including consultant relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Loomba has research grant relationships with numerous companies, including Hanmi, Gilead, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Galectin Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Chalasani has consultant relationships with Ipsen, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, GSK, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, and Zydus. Brown reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — according to interim results from a phase 3 trial.

At 72 weeks, a 2.4-mg once-weekly subcutaneous dose of semaglutide demonstrated superiority, compared with placebo, for the two primary endpoints: Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis and improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis.

“It’s been a long journey. I’ve been working with GLP-1s for 16 years, and it’s great to be able to report the first GLP-1 receptor agonist to demonstrate efficacy in a phase 3 trial for MASH,” said lead author Philip Newsome, MD, PhD, director of the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies at King’s College London in England.

“There were also improvements in a slew of other noninvasive markers,” said Newsome, who presented the findings at The Liver Meeting 2024: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Although already seen in a broader context, “it’s nice to see a demonstration of the cardiometabolic benefits in the context of MASH and a reassuring safety profile,” he added.

Interim ESSENCE Trial Analysis

ESSENCE (NCT04822181) is an ongoing multicenter, phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outcome trial studying semaglutide for the potential treatment of MASH.

The trial includes 1200 participants with biopsy-defined MASH and fibrosis, stages F2 and F3, who were randomized 2:1 to a once-weekly subcutaneous injection of 2.4 mg of semaglutide or placebo for 240 weeks. After initiation, the semaglutide dosage was increased every 4 weeks up to 16 weeks when the full dose (2.4 mg) was reached.

In a planned interim analysis, the trial investigators evaluated the primary endpoints at week 72 for the first 800 participants, with biopsies taken at weeks 1 and 72.

A total of 534 people were randomized to the semaglutide group, including 169 with F2 fibrosis and 365 with F3 fibrosis. Among the 266 participants randomized to placebo, 81 had F2 fibrosis and 185 had F3 fibrosis.

At baseline, the patient characteristics were similar between the groups (mean age, 56 years; body mass index, 34.6). A majority of participants also were White (67.5%), women (57.1%), had type 2 diabetes (55.9%), F3 fibrosis (68.8%), and enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) scores around 10 (55.5%).

For the first primary endpoint, 62.9% of those in the semaglutide group and 34.1% of those in the placebo group reached resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis. This represented an estimated difference in responder proportions (EDP) of 28.9%.

In addition, 37% of those in the semaglutide group and 22.5% of those in the placebo group met the second primary endpoint of improvement in liver fibrosis with no worsening of steatohepatitis (EDP, 14.4%).

Among the secondary endpoints, combined resolution of steatohepatitis with a one-stage improvement in liver fibrosis occurred in 32.8% of the semaglutide group and 16.2% of the placebo group (EDP, 16.6%).

In additional analyses, Newsome and colleagues found 20%-40% improvements in liver enzymes and noninvasive fibrosis markers, such as ELF and vibration-controlled transient elastography liver stiffness.

Weight loss was also significant, with a 10.5% reduction in the semaglutide group compared with a 2% reduction in the placebo group.

Cardiometabolic risk factors improved as well, with changes in blood pressure measurements, hemoglobin A1c scores, and cholesterol values.

Although not considered statistically significant, patients in the semaglutide group also reported greater reductions in body pain.

In a safety analysis of 1195 participants at 96 weeks, adverse events, severe adverse events, and discontinuations were similar in both groups. Not surprisingly, gastrointestinal side effects were more commonly reported in the semaglutide group, Newsome said.

Highly Anticipated Results

After Newsome’s presentation, attendees applauded.

Rohit Loomba, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, called the results the “highlight of the meeting.”

This sentiment was echoed by Naga Chalasani, MD, AGAF, a gastroenterologist at Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis, who called the results a “watershed moment in the MASH field” with “terrific data.”

Based on questions after the presentation, Newsome indicated that future ESSENCE reports would look at certain aspects of the results, such as the 10% weight loss among those in the semaglutide group, as well as the mechanisms of histological and fibrosis improvement.

“We know from other GLP-1 trials that more weight loss occurs in those who don’t have type 2 diabetes, and we’re still running those analyses,” he said. “Weight loss is clearly a major contributor to MASH improvement, but there seem to be some weight-independent effects here, which are likely linked to insulin sensitivity or inflammation. We look forward to presenting those analyses in due course.”

In a comment, Kimberly Ann Brown, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, AASLD Foundation chair, and comoderator of the late-breaking abstract session, spoke about the highly anticipated presentation.

“This study was really the pinnacle of this meeting. We’ve all been waiting for this data, in large part because many of our patients are already using these medications,” Brown said. “Seeing the benefit for the liver, as well as lipids and other cardiovascular measures, is so important. Having this confirmatory study will hopefully lead to the availability of the medication for this indication among our patients.”

Newsome reported numerous disclosures, including consultant relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Loomba has research grant relationships with numerous companies, including Hanmi, Gilead, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Galectin Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Chalasani has consultant relationships with Ipsen, Pfizer, Merck, Altimmune, GSK, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, and Zydus. Brown reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AASLD 24

How to Discuss Lifestyle Modifications in MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

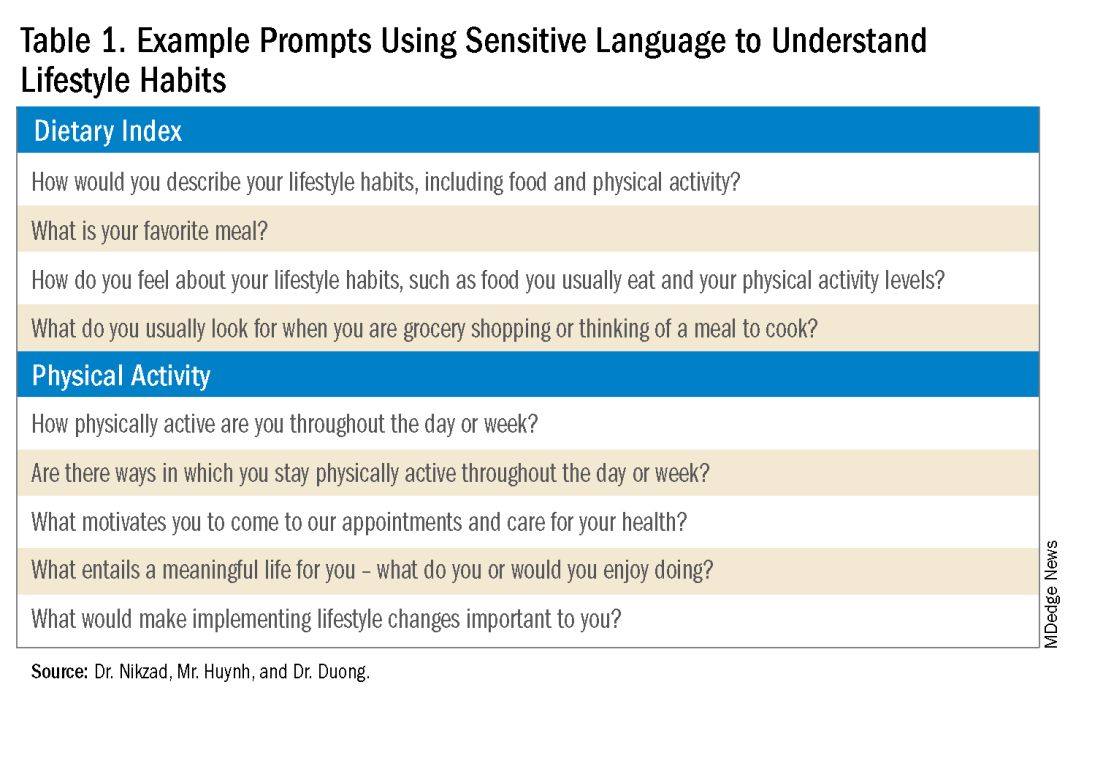

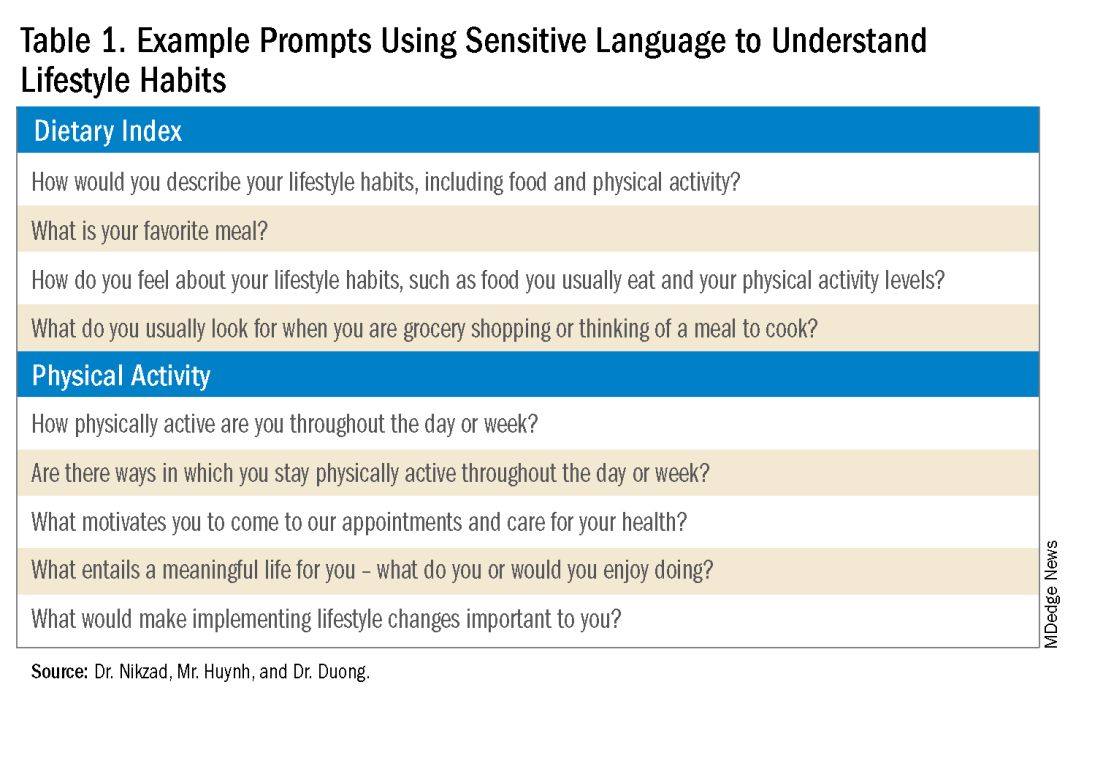

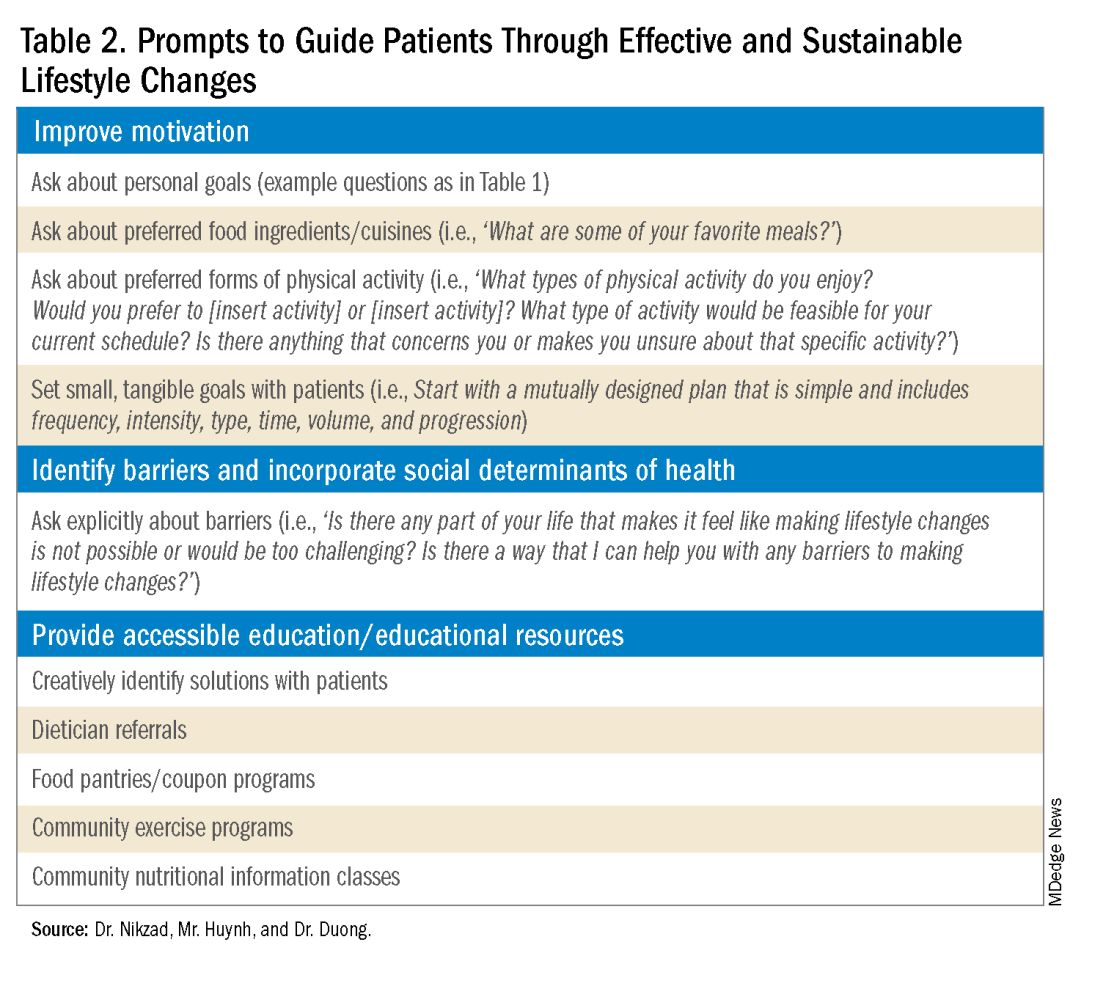

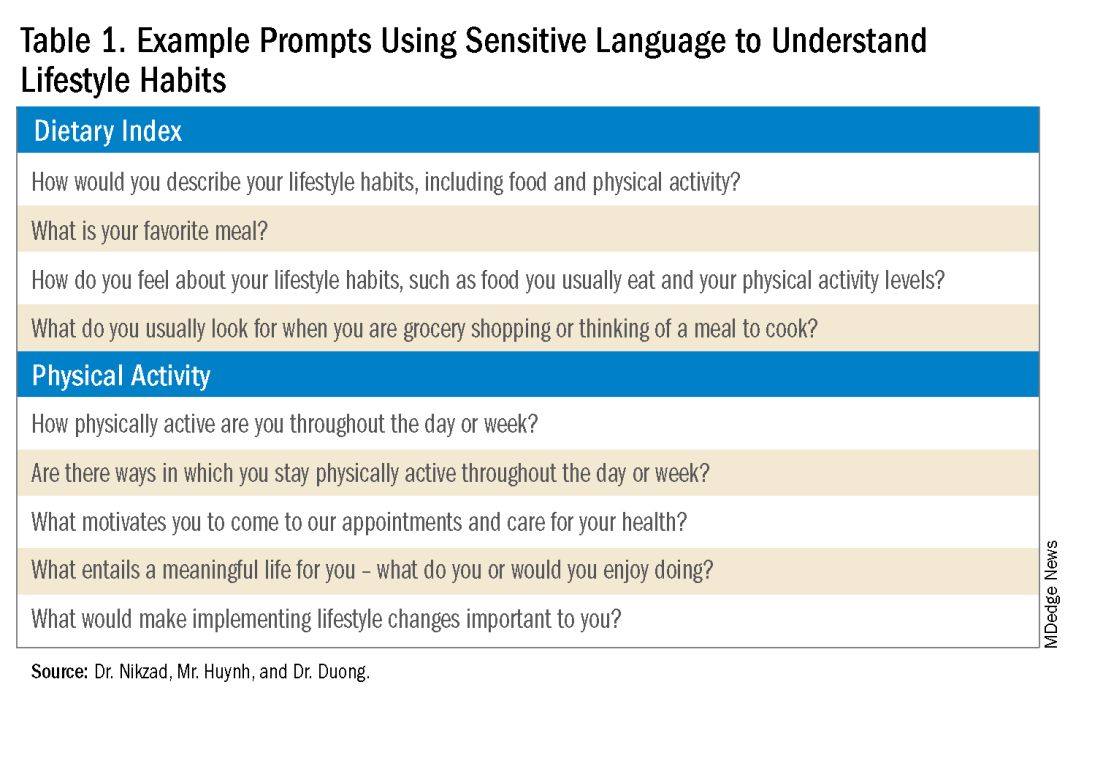

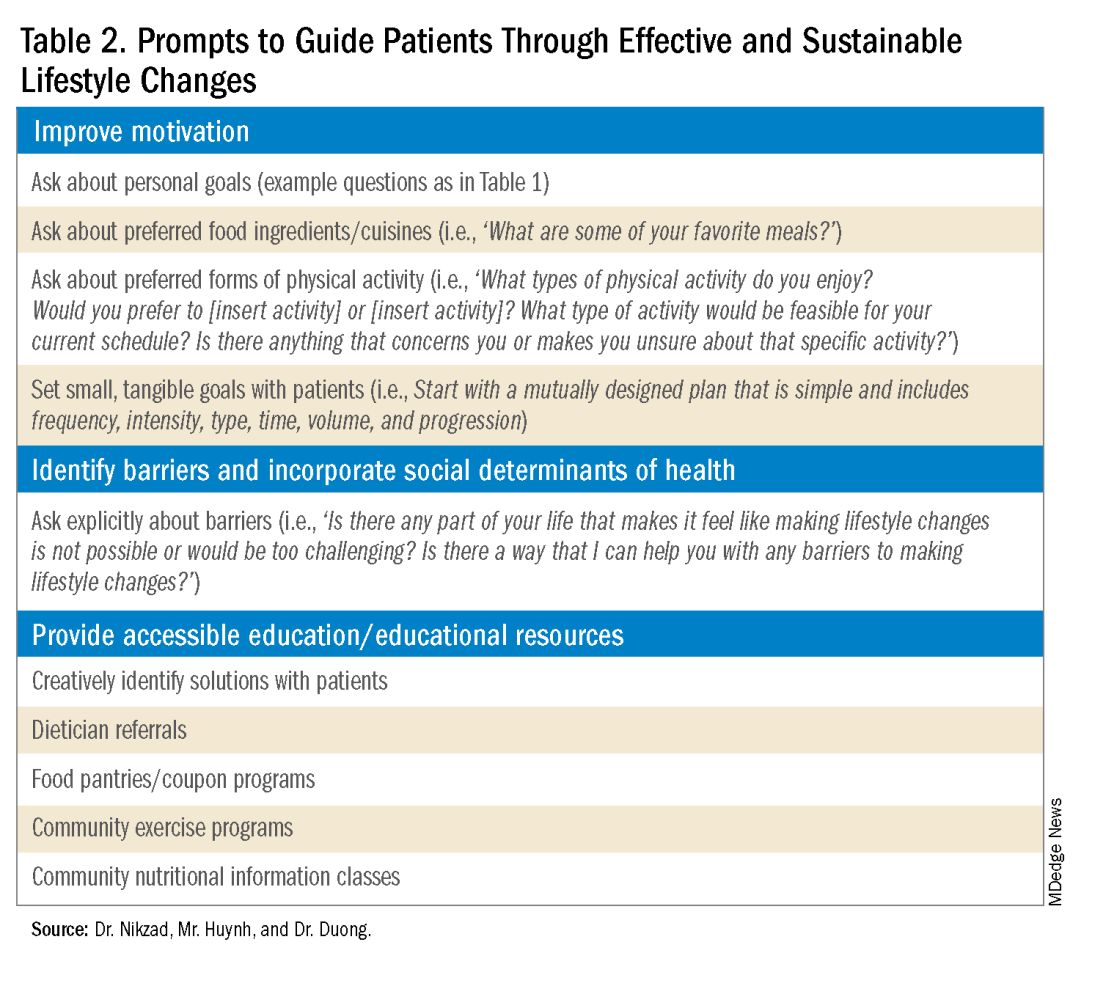

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

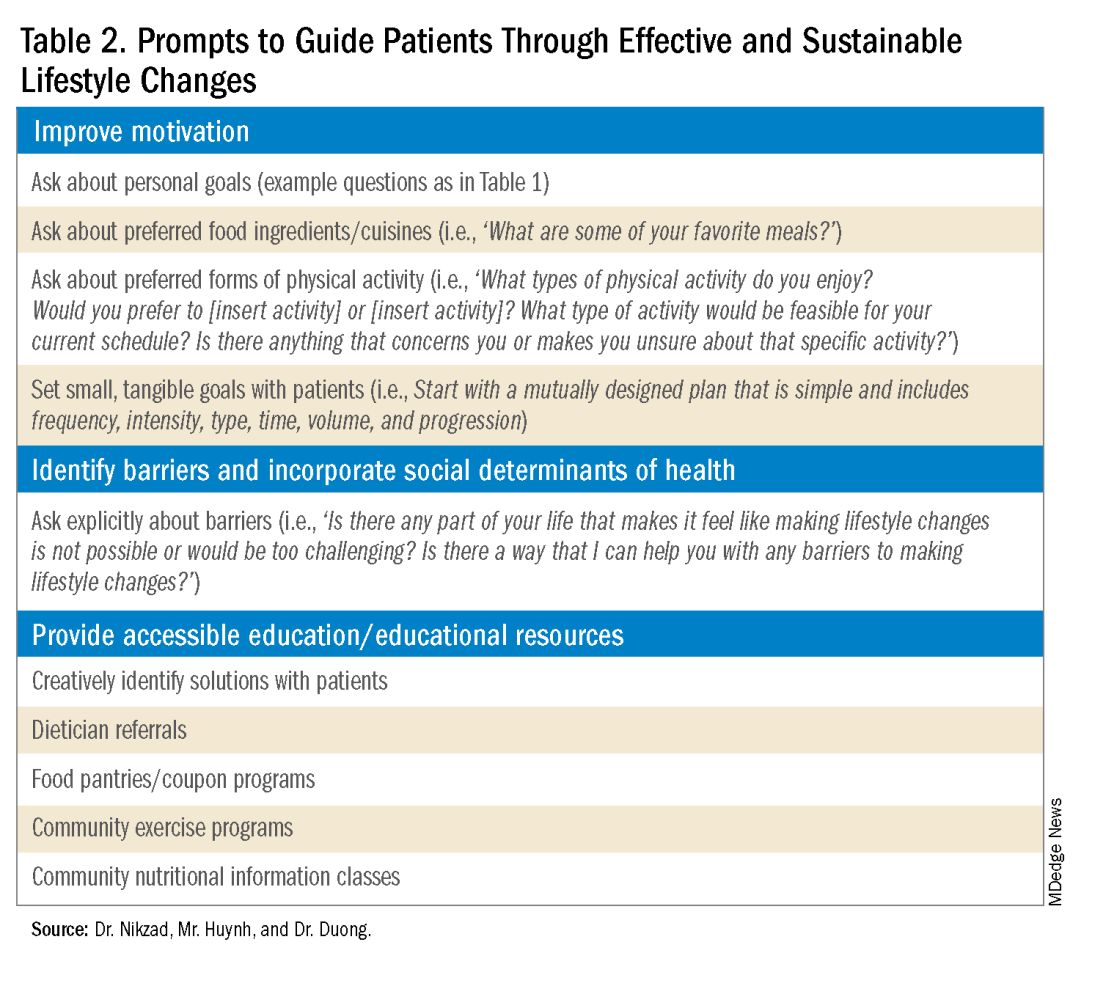

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Journal Highlights: Sept.-Oct. 2024

Upper GI

Levinthal DJ et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.031.

Geeratragool T et al. Comparison of Vonoprazan Versus Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitor for Prevention of High-Risk Peptic Ulcers Rebleeding After Successful Endoscopic Hemostasis: A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.03.036.

Goodoory VC et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010.

Kurlander JE et al; Gastrointestinal Bleeding Working Group. Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors for Prevention of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in US Outpatient Visits. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.047.

Oliva S et al. Crafting a Therapeutic Pyramid for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the Age of Biologics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.020.

Lower GI

Redd WD et al. Follow-Up Colonoscopy for Detection of Missed Colorectal Cancer After Diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.036.

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Upadacitinib Achieves Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Regardless of Prior Biologic Exposure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.02.026.

Chang PW et al. ChatGPT4 Outperforms Endoscopists for Determination of Postcolonoscopy Rescreening and Surveillance Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.022.

Liver

Wang L et al. Association of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Incidence and Hepatic Decompensation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.04.029.

Bajaj JS et al. Serum Ammonia Levels Do Not Correlate With Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy Severity in Hospitalized Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.02.015.

Endoscopy

Steinbrück I, et al. Cold Versus Hot Snare Endoscopic Resection of Large Nonpedunculated Colorectal Polyps: Randomized Controlled German CHRONICLE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.013.

Misc.

Kothari S et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Pregnancy-Related Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.06.014.

Chavannes M et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Intestinal Ultrasound in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.039.

Dr. Trieu is assistant professor of medicine, interventional endoscopy, in the Division of Gastroenterology at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Missouri.

Upper GI

Levinthal DJ et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.031.

Geeratragool T et al. Comparison of Vonoprazan Versus Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitor for Prevention of High-Risk Peptic Ulcers Rebleeding After Successful Endoscopic Hemostasis: A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.03.036.

Goodoory VC et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010.

Kurlander JE et al; Gastrointestinal Bleeding Working Group. Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors for Prevention of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in US Outpatient Visits. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.047.

Oliva S et al. Crafting a Therapeutic Pyramid for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the Age of Biologics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.020.

Lower GI

Redd WD et al. Follow-Up Colonoscopy for Detection of Missed Colorectal Cancer After Diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.036.

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Upadacitinib Achieves Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Regardless of Prior Biologic Exposure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.02.026.

Chang PW et al. ChatGPT4 Outperforms Endoscopists for Determination of Postcolonoscopy Rescreening and Surveillance Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.022.

Liver

Wang L et al. Association of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Incidence and Hepatic Decompensation in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.04.029.

Bajaj JS et al. Serum Ammonia Levels Do Not Correlate With Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy Severity in Hospitalized Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.02.015.

Endoscopy

Steinbrück I, et al. Cold Versus Hot Snare Endoscopic Resection of Large Nonpedunculated Colorectal Polyps: Randomized Controlled German CHRONICLE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.013.

Misc.

Kothari S et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Pregnancy-Related Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.06.014.

Chavannes M et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Intestinal Ultrasound in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.039.

Dr. Trieu is assistant professor of medicine, interventional endoscopy, in the Division of Gastroenterology at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Missouri.

Upper GI

Levinthal DJ et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.031.

Geeratragool T et al. Comparison of Vonoprazan Versus Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitor for Prevention of High-Risk Peptic Ulcers Rebleeding After Successful Endoscopic Hemostasis: A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.03.036.

Goodoory VC et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010.

Kurlander JE et al; Gastrointestinal Bleeding Working Group. Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors for Prevention of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in US Outpatient Visits. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.047.

Oliva S et al. Crafting a Therapeutic Pyramid for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the Age of Biologics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.020.

Lower GI

Redd WD et al. Follow-Up Colonoscopy for Detection of Missed Colorectal Cancer After Diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.036.

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Upadacitinib Achieves Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Regardless of Prior Biologic Exposure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.02.026.

Chang PW et al. ChatGPT4 Outperforms Endoscopists for Determination of Postcolonoscopy Rescreening and Surveillance Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.022.

Liver