User login

U.S. Task Force Takes on Rising BMIs Among Children

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — a team of independent, volunteer experts in disease prevention who guide doctors’ decisions and influence insurance coverage — issued a draft recommendation statement outlining the interventions that should be taken when a child or teen has a high body mass index.

Nearly 20% of children between 2 and 19 years old have what are considered high BMIs, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. While adults who have a BMI of 30 or higher are considered to have obesity, childhood obesity is determined if a child is at or above the 95th percentile of others their age and gender.

Given the prevalence of the issue, the task force recommends behavioral interventions that include at least 26 hours of supervised physical activity sessions for up to a year. This differs from the task force’s previous recommendations on the topic, which emphasized the importance of screening for high BMIs rather than describing the right ways to intervene.

Some of the most effective interventions are targeted at both parents and their children, whether that be together, separately, or a combination of the two. Additionally, the task force recommends that children attend group sessions about healthy eating habits, how to read food labels, and exercise techniques. Ideally, these would be led and guided by people of various professional backgrounds like pediatricians, physical therapists, dietitians, psychologists, and social workers. Other medical organizations, namely the American Academy of Pediatrics, have recommended medication for some children with obesity; the task force, however, takes a more conservative approach. They noted that although the body of evidence shows weight loss medications and surgery are effective for many, there isn’t enough research to lean on regarding the use of these interventions in children, especially in the long term.

“There are proven ways that clinicians can help the many children and teens who have a high BMI to manage their weight and stay healthy,” said Katrina Donahue, MD, MPH, a member of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Intensive behavioral interventions are effective in helping children achieve a healthy weight while improving quality of life.”

The guidelines are still in the draft stage and are available for public comment until Jan. 16, 2024.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — a team of independent, volunteer experts in disease prevention who guide doctors’ decisions and influence insurance coverage — issued a draft recommendation statement outlining the interventions that should be taken when a child or teen has a high body mass index.

Nearly 20% of children between 2 and 19 years old have what are considered high BMIs, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. While adults who have a BMI of 30 or higher are considered to have obesity, childhood obesity is determined if a child is at or above the 95th percentile of others their age and gender.

Given the prevalence of the issue, the task force recommends behavioral interventions that include at least 26 hours of supervised physical activity sessions for up to a year. This differs from the task force’s previous recommendations on the topic, which emphasized the importance of screening for high BMIs rather than describing the right ways to intervene.

Some of the most effective interventions are targeted at both parents and their children, whether that be together, separately, or a combination of the two. Additionally, the task force recommends that children attend group sessions about healthy eating habits, how to read food labels, and exercise techniques. Ideally, these would be led and guided by people of various professional backgrounds like pediatricians, physical therapists, dietitians, psychologists, and social workers. Other medical organizations, namely the American Academy of Pediatrics, have recommended medication for some children with obesity; the task force, however, takes a more conservative approach. They noted that although the body of evidence shows weight loss medications and surgery are effective for many, there isn’t enough research to lean on regarding the use of these interventions in children, especially in the long term.

“There are proven ways that clinicians can help the many children and teens who have a high BMI to manage their weight and stay healthy,” said Katrina Donahue, MD, MPH, a member of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Intensive behavioral interventions are effective in helping children achieve a healthy weight while improving quality of life.”

The guidelines are still in the draft stage and are available for public comment until Jan. 16, 2024.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — a team of independent, volunteer experts in disease prevention who guide doctors’ decisions and influence insurance coverage — issued a draft recommendation statement outlining the interventions that should be taken when a child or teen has a high body mass index.

Nearly 20% of children between 2 and 19 years old have what are considered high BMIs, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. While adults who have a BMI of 30 or higher are considered to have obesity, childhood obesity is determined if a child is at or above the 95th percentile of others their age and gender.

Given the prevalence of the issue, the task force recommends behavioral interventions that include at least 26 hours of supervised physical activity sessions for up to a year. This differs from the task force’s previous recommendations on the topic, which emphasized the importance of screening for high BMIs rather than describing the right ways to intervene.

Some of the most effective interventions are targeted at both parents and their children, whether that be together, separately, or a combination of the two. Additionally, the task force recommends that children attend group sessions about healthy eating habits, how to read food labels, and exercise techniques. Ideally, these would be led and guided by people of various professional backgrounds like pediatricians, physical therapists, dietitians, psychologists, and social workers. Other medical organizations, namely the American Academy of Pediatrics, have recommended medication for some children with obesity; the task force, however, takes a more conservative approach. They noted that although the body of evidence shows weight loss medications and surgery are effective for many, there isn’t enough research to lean on regarding the use of these interventions in children, especially in the long term.

“There are proven ways that clinicians can help the many children and teens who have a high BMI to manage their weight and stay healthy,” said Katrina Donahue, MD, MPH, a member of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Intensive behavioral interventions are effective in helping children achieve a healthy weight while improving quality of life.”

The guidelines are still in the draft stage and are available for public comment until Jan. 16, 2024.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Slow-to-moderate weight loss better than rapid with antiobesity drugs in OA

TOPLINE:

Individuals with overweight or obesity and knee or hip osteoarthritis (OA) who used antiobesity medications and achieved slow-to-moderate weight loss had a lower risk for all-cause mortality than did those with weight gain or stable weight in a population-based cohort study emulating a randomized controlled trial. Patients who rapidly lost weight had mortality similar to those with weight gain or stable weight.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers used the IQVIA Medical Research Database to identify overweight or obese individuals with knee or hip OA; they conducted a hypothetical trial comparing the effects of slow-to-moderate weight loss (defined as 2%-10% of body weight) and rapid weight loss (defined as 5% or more of body weight) within 1 year of starting antiobesity medications.

- The final analysis included patients with a mean age of 60.9 years who met the criteria for treatment adherence to orlistat (n = 3028), sibutramine (n = 2919), or rimonabant (n = 797).

- The primary outcome was all-cause mortality over a 5-year follow-up period; secondary outcomes included hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism.

TAKEAWAY:

- All-cause mortality at 5 years was 5.3% with weight gain or stable weight, 4.0% with slow to moderate weight loss, and 5.4% with rapid weight loss.

- Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.92) for slow to moderate weight loss and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.67-1.44) for the rapid weight loss group.

- Weight loss was associated with the secondary outcomes of reduced hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism in a dose-dependent manner.

- A slightly increased risk for cardiovascular disease occurred in the rapid weight loss group, compared with the weight gain or stable group, but this difference was not significant.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding that gradual weight loss by antiobesity medications lowers all-cause mortality, if confirmed by future studies, could guide policy-making and improve the well-being of patients with overweight or obesity and knee or hip OA,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author on the study was Jie Wei, MD, of Central South University, Changsha, China. The study was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included the inability to control for factors such as exercise, diet, and disease severity; the inability to assess the risk for cause-specific mortality; and the inability to account for the impact of pain reduction and improved function as a result of weight loss.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Project Program of National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, the Central South University Innovation-Driven Research Programme, and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Individuals with overweight or obesity and knee or hip osteoarthritis (OA) who used antiobesity medications and achieved slow-to-moderate weight loss had a lower risk for all-cause mortality than did those with weight gain or stable weight in a population-based cohort study emulating a randomized controlled trial. Patients who rapidly lost weight had mortality similar to those with weight gain or stable weight.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers used the IQVIA Medical Research Database to identify overweight or obese individuals with knee or hip OA; they conducted a hypothetical trial comparing the effects of slow-to-moderate weight loss (defined as 2%-10% of body weight) and rapid weight loss (defined as 5% or more of body weight) within 1 year of starting antiobesity medications.

- The final analysis included patients with a mean age of 60.9 years who met the criteria for treatment adherence to orlistat (n = 3028), sibutramine (n = 2919), or rimonabant (n = 797).

- The primary outcome was all-cause mortality over a 5-year follow-up period; secondary outcomes included hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism.

TAKEAWAY:

- All-cause mortality at 5 years was 5.3% with weight gain or stable weight, 4.0% with slow to moderate weight loss, and 5.4% with rapid weight loss.

- Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.92) for slow to moderate weight loss and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.67-1.44) for the rapid weight loss group.

- Weight loss was associated with the secondary outcomes of reduced hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism in a dose-dependent manner.

- A slightly increased risk for cardiovascular disease occurred in the rapid weight loss group, compared with the weight gain or stable group, but this difference was not significant.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding that gradual weight loss by antiobesity medications lowers all-cause mortality, if confirmed by future studies, could guide policy-making and improve the well-being of patients with overweight or obesity and knee or hip OA,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author on the study was Jie Wei, MD, of Central South University, Changsha, China. The study was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included the inability to control for factors such as exercise, diet, and disease severity; the inability to assess the risk for cause-specific mortality; and the inability to account for the impact of pain reduction and improved function as a result of weight loss.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Project Program of National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, the Central South University Innovation-Driven Research Programme, and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Individuals with overweight or obesity and knee or hip osteoarthritis (OA) who used antiobesity medications and achieved slow-to-moderate weight loss had a lower risk for all-cause mortality than did those with weight gain or stable weight in a population-based cohort study emulating a randomized controlled trial. Patients who rapidly lost weight had mortality similar to those with weight gain or stable weight.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers used the IQVIA Medical Research Database to identify overweight or obese individuals with knee or hip OA; they conducted a hypothetical trial comparing the effects of slow-to-moderate weight loss (defined as 2%-10% of body weight) and rapid weight loss (defined as 5% or more of body weight) within 1 year of starting antiobesity medications.

- The final analysis included patients with a mean age of 60.9 years who met the criteria for treatment adherence to orlistat (n = 3028), sibutramine (n = 2919), or rimonabant (n = 797).

- The primary outcome was all-cause mortality over a 5-year follow-up period; secondary outcomes included hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism.

TAKEAWAY:

- All-cause mortality at 5 years was 5.3% with weight gain or stable weight, 4.0% with slow to moderate weight loss, and 5.4% with rapid weight loss.

- Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.92) for slow to moderate weight loss and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.67-1.44) for the rapid weight loss group.

- Weight loss was associated with the secondary outcomes of reduced hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and venous thromboembolism in a dose-dependent manner.

- A slightly increased risk for cardiovascular disease occurred in the rapid weight loss group, compared with the weight gain or stable group, but this difference was not significant.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our finding that gradual weight loss by antiobesity medications lowers all-cause mortality, if confirmed by future studies, could guide policy-making and improve the well-being of patients with overweight or obesity and knee or hip OA,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The lead author on the study was Jie Wei, MD, of Central South University, Changsha, China. The study was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included the inability to control for factors such as exercise, diet, and disease severity; the inability to assess the risk for cause-specific mortality; and the inability to account for the impact of pain reduction and improved function as a result of weight loss.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Project Program of National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, the Central South University Innovation-Driven Research Programme, and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What if a single GLP-1 shot could last for months?

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As revolutionary as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) drugs are, they still last for only so long in the body. Patients with diabetes typically must be injected once or twice a day (liraglutide) or once a week (semaglutide). This could hinder proper diabetes management, as adherence tends to go down the more frequent the dose.

But what if a single GLP-1 injection could last for 4 months?

“melts away like a sugar cube dissolving in water, molecule by molecule,” said Eric Appel, PhD, the project’s principal investigator and an associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

So far, the team has tested the new drug delivery system in rats, and they say human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

Mathematical modeling indicated that one shot of liraglutide could maintain exposure in humans for 120 days, or about 4 months, according to their study in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Patient adherence is of critical importance to diabetes care,” said Alex Abramson, PhD, assistant professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at Georgia Tech, who was not involved in the study. “It’s very exciting to have a potential new system that can last 4 months on a single injection.”

Long-Acting Injectables Have Come a Long Way

The first long-acting injectable — Lupron Depot, a monthly treatment for advanced prostate cancer — was approved in 1989. Since then, long-acting injectable depots have revolutionized the treatment and management of conditions ranging from osteoarthritis knee pain to schizophrenia to opioid use disorder. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Apretude — an injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention that needs to be given every 2 months, compared with daily for the pill equivalent. Other new and innovative developments are underway: Researchers at the University of Connecticut are working on a transdermal microneedle patch — with many tiny vaccine-loaded needles — that could provide multiple doses of a vaccine over time, no boosters needed.

At Stanford, Appel’s lab has spent years developing gels for drug delivery. His team uses a class of hydrogel called polymer-nanoparticle (PNP), which features weakly bound polymers and nanoparticles that can dissipate slowly over time.

The goal is to address a longstanding challenge with long-acting formulations: Achieving steady release. Because the hydrogel is “self-healing” — able to repair damages and restore its shape — it’s less likely to burst and release its drug cargo too early.

“Our PNP hydrogels possess a number of really unique characteristics,” Dr. Appel said. They have “excellent” biocompatibility, based on animal studies, and could work with a wide range of drugs. In proof-of-concept mouse studies, Dr. Appel and his team have shown that these hydrogels could also be used to make vaccines last longer, ferry cancer immunotherapies directly to tumors, and deliver antibodies for the prevention of infectious diseases like SARS-CoV-2.

Though the recent study on GLP-1s focused on treating type 2 diabetes, the same formulation could also be used to treat obesity, said Dr. Appel.

The researchers tested the tech using two GLP-1 receptor agonists — semaglutide and liraglutide. In rats, one shot maintained therapeutic serum concentrations of semaglutide or liraglutide over 42 days. With semaglutide, a significant portion was released quickly, followed by controlled release. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was released gradually as the hydrogel dissolved. This suggests the liraglutide hydrogel may be better tolerated, as a sudden peak in drug serum concentration is associated with adverse effects.

The researchers used pharmacokinetic modeling to predict how liraglutide would behave in humans with a larger injection volume, finding that a single dose could maintain therapeutic levels for about 4 months.

“Moving forward, it will be important to determine whether a burst release from the formulation causes any side effects,” Dr. Abramson noted. “Furthermore, it will be important to minimize the injection volumes in humans.”

But first, more studies in larger animals are needed. Next, Dr. Appel and his team plan to test the technology in pigs, whose skin and endocrine systems are most like humans’. If those trials go well, Dr. Appel said, human clinical trials could start within 2 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL REPORTS MEDICINE

How to prescribe Zepbound

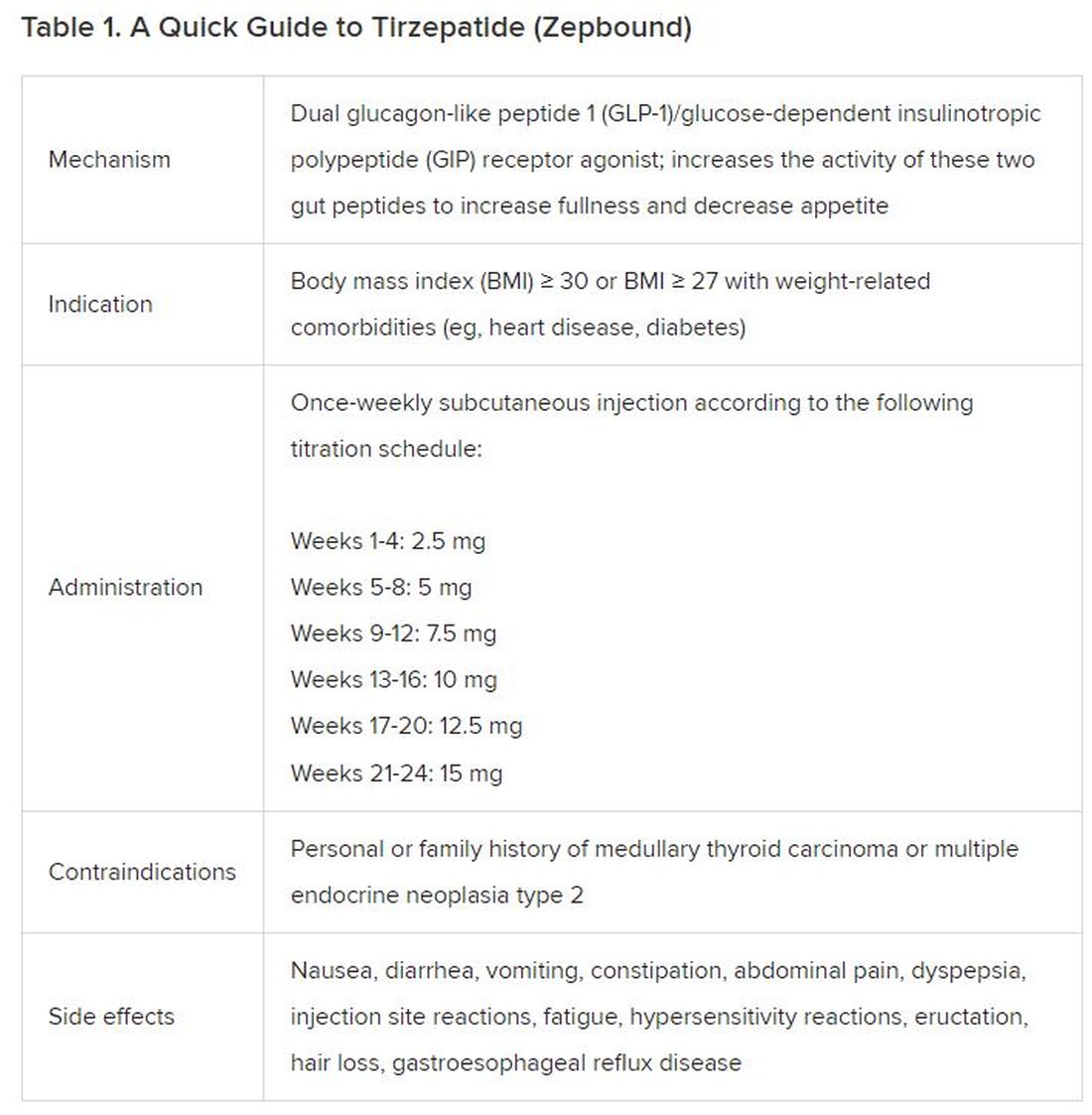

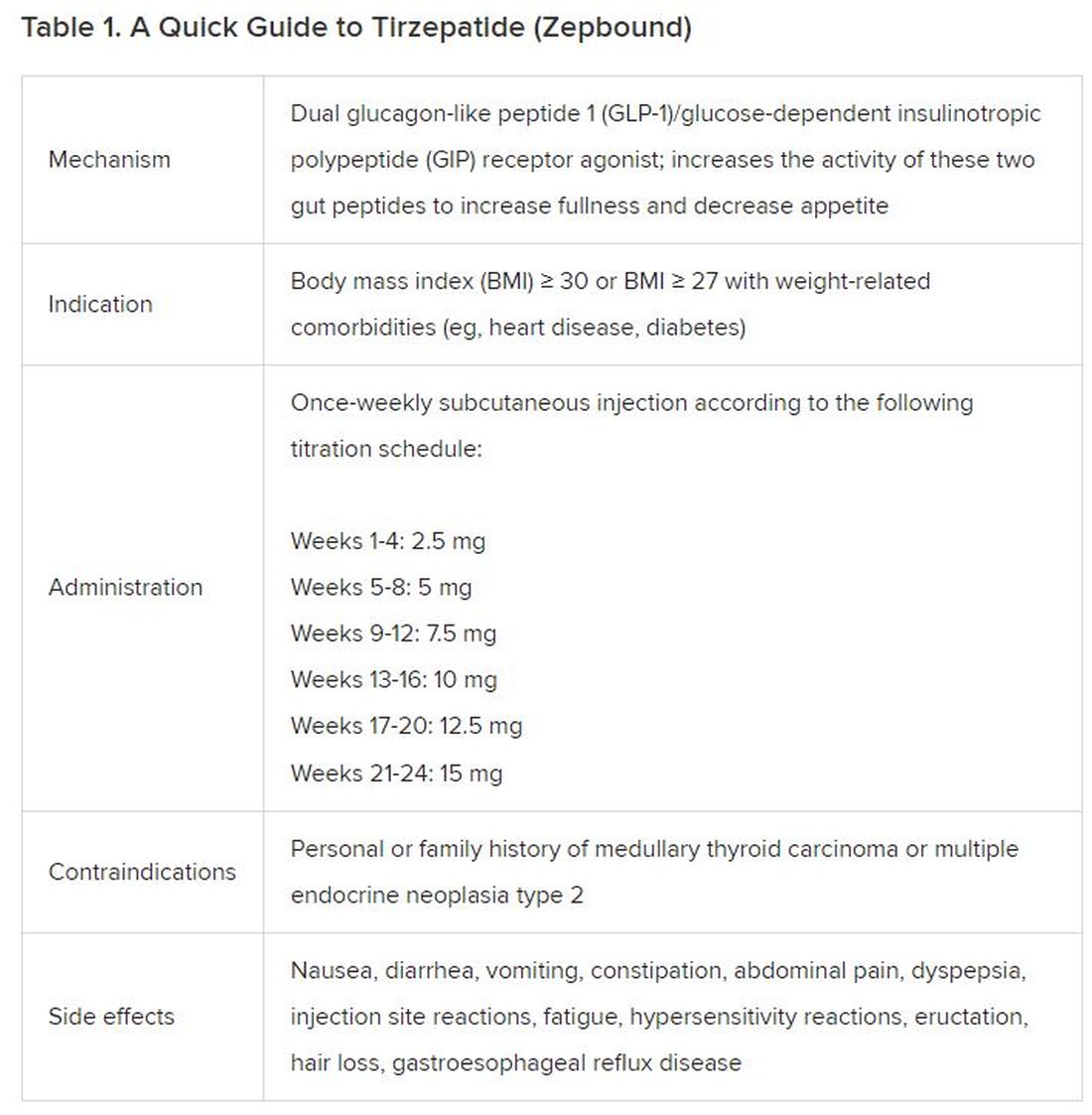

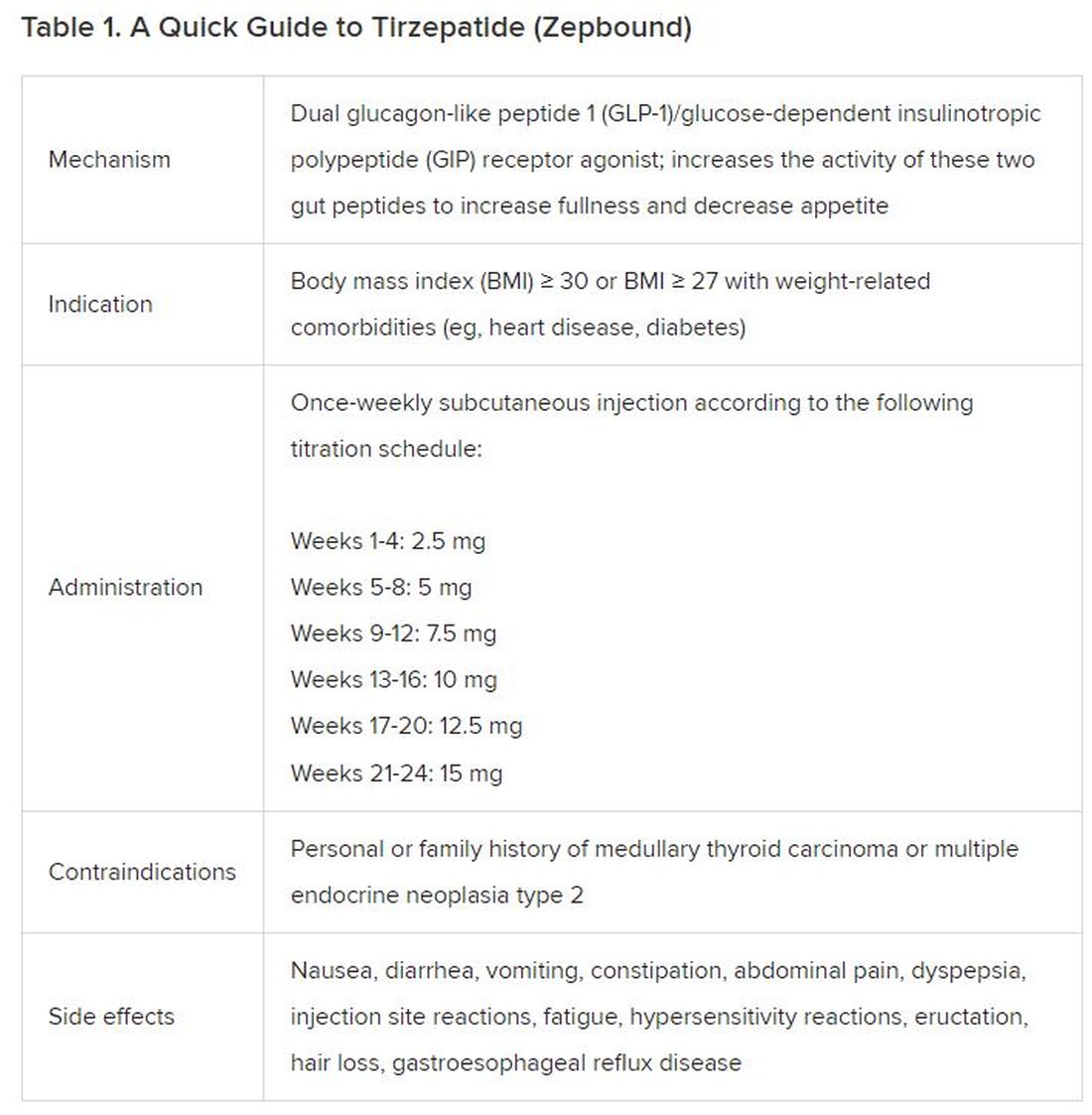

December marks the advent of the approval of tirzepatide (Zepbound) for on-label treatment of obesity. In November 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of obesity in adults.

In May 2022, the FDA approved Mounjaro, which is tirzepatide, for type 2 diabetes. Since then, many physicians, including myself, have prescribed it off-label for obesity. As an endocrinologist treating both obesity and diabetes,

The Expertise

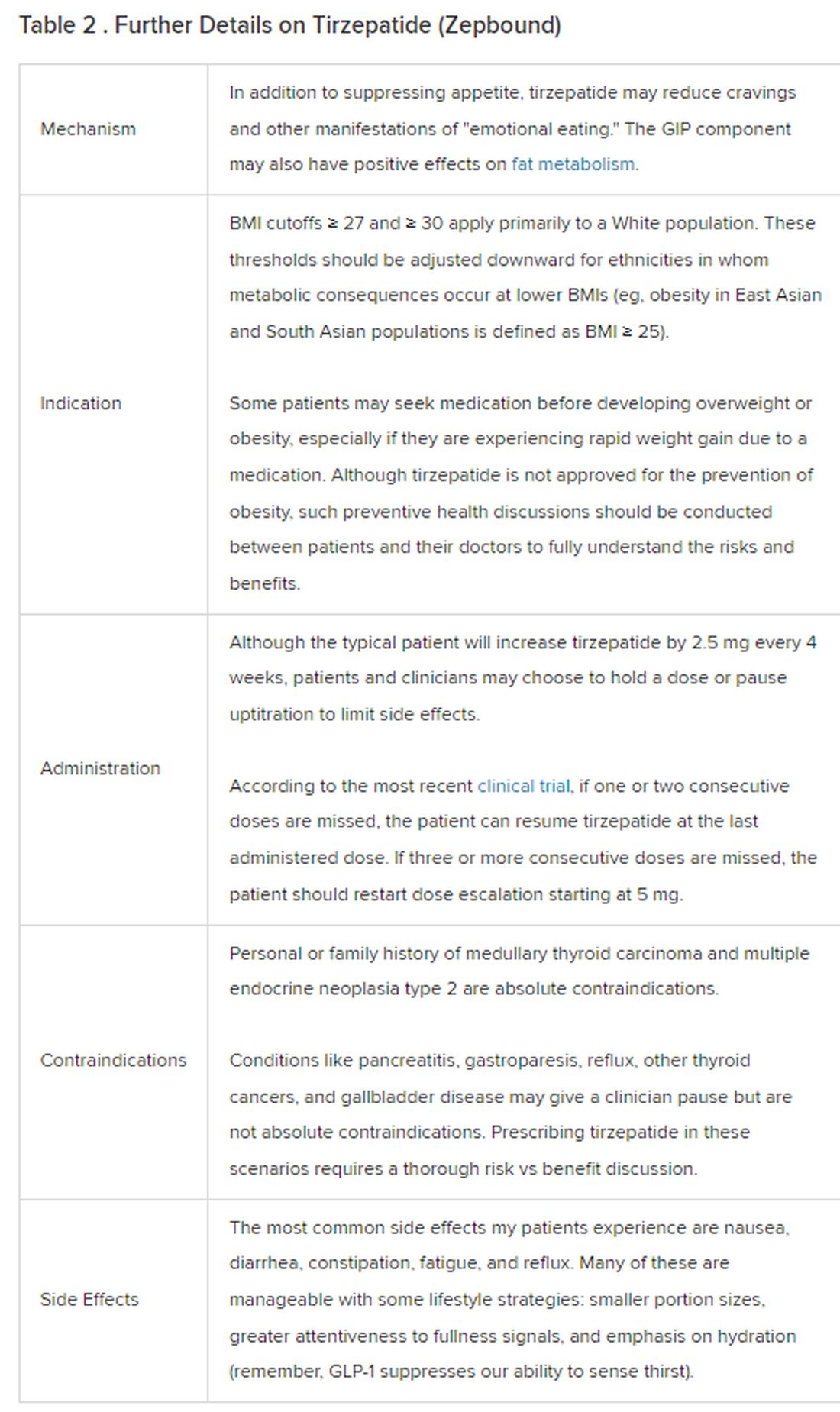

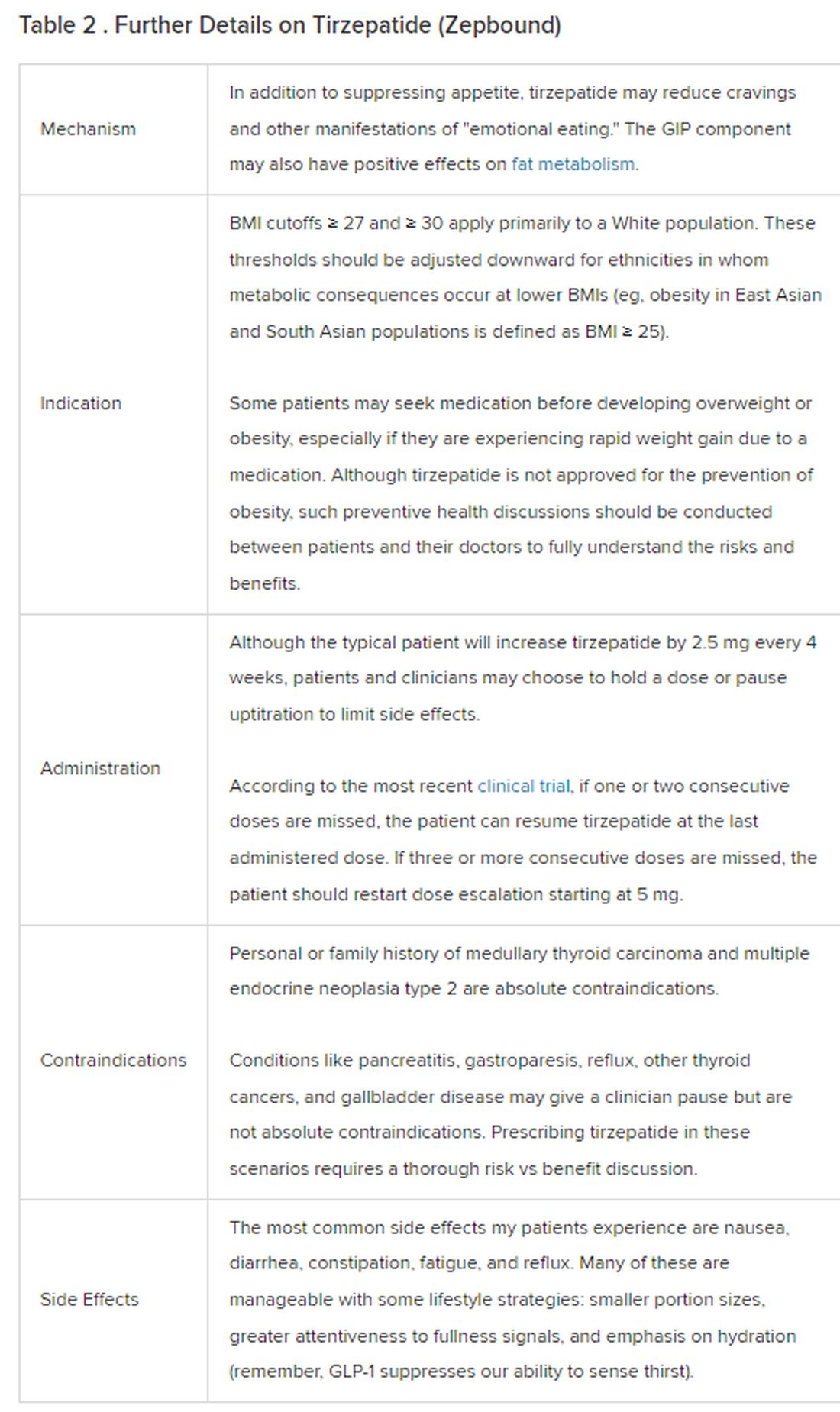

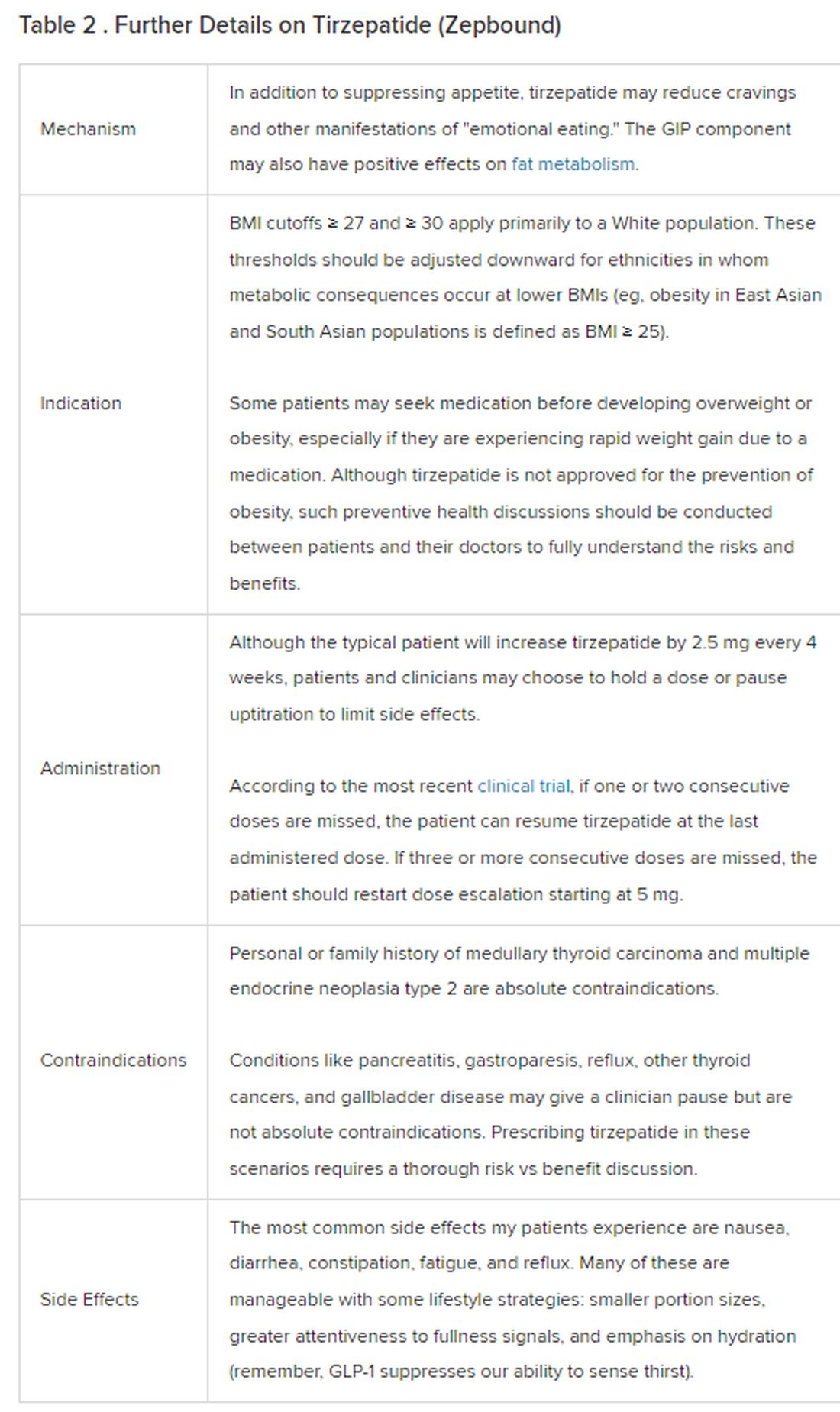

Because GLP-1 receptor agonists have been around since 2005, we’ve had over a decade of clinical experience with these medications. Table 2 provides more nuanced information on tirzepatide (as Zepbound, for obesity) based on our experiences with dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (as Mounjaro).

The Reality

In today’s increasingly complex healthcare system, the reality of providing high-quality obesity care is challenging. When discussing tirzepatide with patients, I use a 4 Cs schematic — comorbidities, cautions, costs, choices — to cover the most frequently asked questions.

Comorbidities

In trials, tirzepatide reduced A1c by about 2%. In one diabetes trial, tirzepatide reduced liver fat content significantly more than the comparator (insulin), and trials of tirzepatide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are ongoing. A prespecified meta-analysis of tirzepatide and cardiovascular disease estimated a 20% reduction in the risk for cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hospitalized unstable angina. Tirzepatide as well as other GLP-1 agonists may be beneficial in alcohol use disorder. Prescribing tirzepatide to patients who have or are at risk of developing such comorbidities is an ideal way to target multiple metabolic diseases with one agent.

Cautions

The first principle of medicine is “do no harm.” Tirzepatide may be a poor option for individuals with a history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Because tirzepatide may interfere with the efficacy of estrogen-containing contraceptives during its uptitration phase, women should speak with their doctors about appropriate birth control options (eg, progestin-only, barrier methods). In clinical trials of tirzepatide, male participants were also advised to use reliable contraception. If patients are family-planning, tirzepatide should be discontinued 2 months (for women) and 4 months (for men) before conception, because its effects on fertility or pregnancy are currently unknown.

Costs

At a retail price of $1279 per month, Zepbound is only slightly more affordable than its main competitor, Wegovy (semaglutide 2.4 mg). Complex pharmacy negotiations may reduce this cost, but even with rebates, coupons, and commercial insurance, these costs still place tirzepatide out of reach for many patients. For patients who cannot access tirzepatide, clinicians should discuss more cost-feasible, evidence-based alternatives: for example, phentermine, phentermine-topiramate, naltrexone-bupropion, metformin, bupropion, or topiramate.

Choices

Patient preference drives much of today’s clinical decision-making. Some patients may be switching from semaglutide to tirzepatide, whether by choice or on the basis of physician recommendation. Although no head-to-head obesity trial exists, data from SURPASS-2 and SUSTAIN-FORTE can inform therapeutic equivalence:

- Semaglutide 1.0 mg to tirzepatide 2.5 mg will be a step-down; 5 mg will be a step-up

- Semaglutide 2.0 or 2.4 mg to tirzepatide 5 mg is probably equivalent

The decision to switch therapeutics may depend on weight loss goals, side effect tolerability, or insurance coverage. As with all medications, the use of tirzepatide should progress with shared decision-making, thorough discussions of risks vs benefits, and individualized regimens tailored to each patient’s needs.

The newly approved Zepbound is a valuable addition to our toolbox of obesity treatments. Patients and providers alike are excited for its potential as a highly effective antiobesity medication that can cause a degree of weight loss necessary to reverse comorbidities. The medical management of obesity with agents like tirzepatide holds great promise in addressing today’s obesity epidemic.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed ties to Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

December marks the advent of the approval of tirzepatide (Zepbound) for on-label treatment of obesity. In November 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of obesity in adults.

In May 2022, the FDA approved Mounjaro, which is tirzepatide, for type 2 diabetes. Since then, many physicians, including myself, have prescribed it off-label for obesity. As an endocrinologist treating both obesity and diabetes,

The Expertise

Because GLP-1 receptor agonists have been around since 2005, we’ve had over a decade of clinical experience with these medications. Table 2 provides more nuanced information on tirzepatide (as Zepbound, for obesity) based on our experiences with dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (as Mounjaro).

The Reality

In today’s increasingly complex healthcare system, the reality of providing high-quality obesity care is challenging. When discussing tirzepatide with patients, I use a 4 Cs schematic — comorbidities, cautions, costs, choices — to cover the most frequently asked questions.

Comorbidities

In trials, tirzepatide reduced A1c by about 2%. In one diabetes trial, tirzepatide reduced liver fat content significantly more than the comparator (insulin), and trials of tirzepatide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are ongoing. A prespecified meta-analysis of tirzepatide and cardiovascular disease estimated a 20% reduction in the risk for cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hospitalized unstable angina. Tirzepatide as well as other GLP-1 agonists may be beneficial in alcohol use disorder. Prescribing tirzepatide to patients who have or are at risk of developing such comorbidities is an ideal way to target multiple metabolic diseases with one agent.

Cautions

The first principle of medicine is “do no harm.” Tirzepatide may be a poor option for individuals with a history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Because tirzepatide may interfere with the efficacy of estrogen-containing contraceptives during its uptitration phase, women should speak with their doctors about appropriate birth control options (eg, progestin-only, barrier methods). In clinical trials of tirzepatide, male participants were also advised to use reliable contraception. If patients are family-planning, tirzepatide should be discontinued 2 months (for women) and 4 months (for men) before conception, because its effects on fertility or pregnancy are currently unknown.

Costs

At a retail price of $1279 per month, Zepbound is only slightly more affordable than its main competitor, Wegovy (semaglutide 2.4 mg). Complex pharmacy negotiations may reduce this cost, but even with rebates, coupons, and commercial insurance, these costs still place tirzepatide out of reach for many patients. For patients who cannot access tirzepatide, clinicians should discuss more cost-feasible, evidence-based alternatives: for example, phentermine, phentermine-topiramate, naltrexone-bupropion, metformin, bupropion, or topiramate.

Choices

Patient preference drives much of today’s clinical decision-making. Some patients may be switching from semaglutide to tirzepatide, whether by choice or on the basis of physician recommendation. Although no head-to-head obesity trial exists, data from SURPASS-2 and SUSTAIN-FORTE can inform therapeutic equivalence:

- Semaglutide 1.0 mg to tirzepatide 2.5 mg will be a step-down; 5 mg will be a step-up

- Semaglutide 2.0 or 2.4 mg to tirzepatide 5 mg is probably equivalent

The decision to switch therapeutics may depend on weight loss goals, side effect tolerability, or insurance coverage. As with all medications, the use of tirzepatide should progress with shared decision-making, thorough discussions of risks vs benefits, and individualized regimens tailored to each patient’s needs.

The newly approved Zepbound is a valuable addition to our toolbox of obesity treatments. Patients and providers alike are excited for its potential as a highly effective antiobesity medication that can cause a degree of weight loss necessary to reverse comorbidities. The medical management of obesity with agents like tirzepatide holds great promise in addressing today’s obesity epidemic.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed ties to Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

December marks the advent of the approval of tirzepatide (Zepbound) for on-label treatment of obesity. In November 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of obesity in adults.

In May 2022, the FDA approved Mounjaro, which is tirzepatide, for type 2 diabetes. Since then, many physicians, including myself, have prescribed it off-label for obesity. As an endocrinologist treating both obesity and diabetes,

The Expertise

Because GLP-1 receptor agonists have been around since 2005, we’ve had over a decade of clinical experience with these medications. Table 2 provides more nuanced information on tirzepatide (as Zepbound, for obesity) based on our experiences with dulaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (as Mounjaro).

The Reality

In today’s increasingly complex healthcare system, the reality of providing high-quality obesity care is challenging. When discussing tirzepatide with patients, I use a 4 Cs schematic — comorbidities, cautions, costs, choices — to cover the most frequently asked questions.

Comorbidities

In trials, tirzepatide reduced A1c by about 2%. In one diabetes trial, tirzepatide reduced liver fat content significantly more than the comparator (insulin), and trials of tirzepatide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are ongoing. A prespecified meta-analysis of tirzepatide and cardiovascular disease estimated a 20% reduction in the risk for cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hospitalized unstable angina. Tirzepatide as well as other GLP-1 agonists may be beneficial in alcohol use disorder. Prescribing tirzepatide to patients who have or are at risk of developing such comorbidities is an ideal way to target multiple metabolic diseases with one agent.

Cautions

The first principle of medicine is “do no harm.” Tirzepatide may be a poor option for individuals with a history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Because tirzepatide may interfere with the efficacy of estrogen-containing contraceptives during its uptitration phase, women should speak with their doctors about appropriate birth control options (eg, progestin-only, barrier methods). In clinical trials of tirzepatide, male participants were also advised to use reliable contraception. If patients are family-planning, tirzepatide should be discontinued 2 months (for women) and 4 months (for men) before conception, because its effects on fertility or pregnancy are currently unknown.

Costs

At a retail price of $1279 per month, Zepbound is only slightly more affordable than its main competitor, Wegovy (semaglutide 2.4 mg). Complex pharmacy negotiations may reduce this cost, but even with rebates, coupons, and commercial insurance, these costs still place tirzepatide out of reach for many patients. For patients who cannot access tirzepatide, clinicians should discuss more cost-feasible, evidence-based alternatives: for example, phentermine, phentermine-topiramate, naltrexone-bupropion, metformin, bupropion, or topiramate.

Choices

Patient preference drives much of today’s clinical decision-making. Some patients may be switching from semaglutide to tirzepatide, whether by choice or on the basis of physician recommendation. Although no head-to-head obesity trial exists, data from SURPASS-2 and SUSTAIN-FORTE can inform therapeutic equivalence:

- Semaglutide 1.0 mg to tirzepatide 2.5 mg will be a step-down; 5 mg will be a step-up

- Semaglutide 2.0 or 2.4 mg to tirzepatide 5 mg is probably equivalent

The decision to switch therapeutics may depend on weight loss goals, side effect tolerability, or insurance coverage. As with all medications, the use of tirzepatide should progress with shared decision-making, thorough discussions of risks vs benefits, and individualized regimens tailored to each patient’s needs.

The newly approved Zepbound is a valuable addition to our toolbox of obesity treatments. Patients and providers alike are excited for its potential as a highly effective antiobesity medication that can cause a degree of weight loss necessary to reverse comorbidities. The medical management of obesity with agents like tirzepatide holds great promise in addressing today’s obesity epidemic.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed ties to Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Children who are overweight at risk for chronic kidney disease

TOPLINE

, with the association, though weaker, still significant among those who do not develop type 2 diabetes or hypertension, in a large cohort study.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included data on 593,660 adolescents aged 16-20, born after January 1, 1975, who had medical assessments as part of mandatory military service in Israel.

- The mean age at study entry was 17.2 and 54.5% were male.

- Early CKD was defined as stage 1 to 2 CKD with moderately or severely increased albuminuria, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or higher.

- The study excluded those with kidney pathology, albuminuria, hypertension, dysglycemia, or missing blood pressure or BMI data.

- Participants were followed up until early CKD onset, death, the last day insured, or August 23, 2020.

TAKEAWAY

- With a mean follow-up of 13.4 years, 1963 adolescents (0.3%) overall developed early chronic kidney disease. Among males, an increased risk of developing CKD was observed with a high-normal BMI in adolescence (hazard ratio [HR], 1.8); with overweight BMI (HR, 4.0); with mild obesity (HR, 6.7); and severe obesity (HR, 9.4).

- Among females, the increased risk was also observed with high-normal BMI (HR 1.4); overweight (HR, 2.3); mild obesity (HR, 2.7); and severe obesity (HR, 4.3).

- In excluding those who developed diabetes or hypertension, the overall rate of early CKD in the cohort was 0.2%.

- For males without diabetes or hypertension, the adjusted HR for early CKD with high-normal weight was 1.2; for overweight, HR 1.6; for mild obesity, HR 2.2; and for severe obesity, HR 2.7.

- For females without diabetes or hypertension, the corresponding increased risk for early CKD was HR 1.2 for high-normal BMI; HR 1.8 for overweight; 1.5 for mild obesity and 2.3 for severe obesity.

IN PRACTICE

“These findings suggest that adolescent obesity is a major risk factor for early CKD in young adulthood; this underscores the importance of mitigating adolescent obesity rates and managing risk factors for kidney disease in adolescents with high BMI,” the authors report.

“The association was evident even in persons with high-normal BMI in adolescence, was more pronounced in men, and appeared before the age of 30 years,” they say.

“Given the increasing obesity rates among adolescents, our findings are a harbinger of the potentially preventable increasing burden of CKD and subsequent cardiovascular disease.”

SOURCE

The study was conducted by first author Avishai M. Tsur, MD, of the Israel Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Tel Hashomer, Ramat Gan, Israel and Department of Military Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel, and colleagues. The study was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS

The study lacked longitudinal data on clinical and lifestyle factors, including stress, diet and physical activity. While adolescents were screened using urine dipstick, a lack of serum creatinine measurements could have missed some adolescents with reduced eGFR at the study entry. The generalizability of the results is limited by the lack of people from West Africa and East Asia in the study population.

DISCLOSURES

Coauthor Josef Coresh, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE

, with the association, though weaker, still significant among those who do not develop type 2 diabetes or hypertension, in a large cohort study.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included data on 593,660 adolescents aged 16-20, born after January 1, 1975, who had medical assessments as part of mandatory military service in Israel.

- The mean age at study entry was 17.2 and 54.5% were male.

- Early CKD was defined as stage 1 to 2 CKD with moderately or severely increased albuminuria, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or higher.

- The study excluded those with kidney pathology, albuminuria, hypertension, dysglycemia, or missing blood pressure or BMI data.

- Participants were followed up until early CKD onset, death, the last day insured, or August 23, 2020.

TAKEAWAY

- With a mean follow-up of 13.4 years, 1963 adolescents (0.3%) overall developed early chronic kidney disease. Among males, an increased risk of developing CKD was observed with a high-normal BMI in adolescence (hazard ratio [HR], 1.8); with overweight BMI (HR, 4.0); with mild obesity (HR, 6.7); and severe obesity (HR, 9.4).

- Among females, the increased risk was also observed with high-normal BMI (HR 1.4); overweight (HR, 2.3); mild obesity (HR, 2.7); and severe obesity (HR, 4.3).

- In excluding those who developed diabetes or hypertension, the overall rate of early CKD in the cohort was 0.2%.

- For males without diabetes or hypertension, the adjusted HR for early CKD with high-normal weight was 1.2; for overweight, HR 1.6; for mild obesity, HR 2.2; and for severe obesity, HR 2.7.

- For females without diabetes or hypertension, the corresponding increased risk for early CKD was HR 1.2 for high-normal BMI; HR 1.8 for overweight; 1.5 for mild obesity and 2.3 for severe obesity.

IN PRACTICE

“These findings suggest that adolescent obesity is a major risk factor for early CKD in young adulthood; this underscores the importance of mitigating adolescent obesity rates and managing risk factors for kidney disease in adolescents with high BMI,” the authors report.

“The association was evident even in persons with high-normal BMI in adolescence, was more pronounced in men, and appeared before the age of 30 years,” they say.

“Given the increasing obesity rates among adolescents, our findings are a harbinger of the potentially preventable increasing burden of CKD and subsequent cardiovascular disease.”

SOURCE

The study was conducted by first author Avishai M. Tsur, MD, of the Israel Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Tel Hashomer, Ramat Gan, Israel and Department of Military Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel, and colleagues. The study was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS

The study lacked longitudinal data on clinical and lifestyle factors, including stress, diet and physical activity. While adolescents were screened using urine dipstick, a lack of serum creatinine measurements could have missed some adolescents with reduced eGFR at the study entry. The generalizability of the results is limited by the lack of people from West Africa and East Asia in the study population.

DISCLOSURES

Coauthor Josef Coresh, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE

, with the association, though weaker, still significant among those who do not develop type 2 diabetes or hypertension, in a large cohort study.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included data on 593,660 adolescents aged 16-20, born after January 1, 1975, who had medical assessments as part of mandatory military service in Israel.

- The mean age at study entry was 17.2 and 54.5% were male.

- Early CKD was defined as stage 1 to 2 CKD with moderately or severely increased albuminuria, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or higher.

- The study excluded those with kidney pathology, albuminuria, hypertension, dysglycemia, or missing blood pressure or BMI data.

- Participants were followed up until early CKD onset, death, the last day insured, or August 23, 2020.

TAKEAWAY

- With a mean follow-up of 13.4 years, 1963 adolescents (0.3%) overall developed early chronic kidney disease. Among males, an increased risk of developing CKD was observed with a high-normal BMI in adolescence (hazard ratio [HR], 1.8); with overweight BMI (HR, 4.0); with mild obesity (HR, 6.7); and severe obesity (HR, 9.4).

- Among females, the increased risk was also observed with high-normal BMI (HR 1.4); overweight (HR, 2.3); mild obesity (HR, 2.7); and severe obesity (HR, 4.3).

- In excluding those who developed diabetes or hypertension, the overall rate of early CKD in the cohort was 0.2%.

- For males without diabetes or hypertension, the adjusted HR for early CKD with high-normal weight was 1.2; for overweight, HR 1.6; for mild obesity, HR 2.2; and for severe obesity, HR 2.7.

- For females without diabetes or hypertension, the corresponding increased risk for early CKD was HR 1.2 for high-normal BMI; HR 1.8 for overweight; 1.5 for mild obesity and 2.3 for severe obesity.

IN PRACTICE

“These findings suggest that adolescent obesity is a major risk factor for early CKD in young adulthood; this underscores the importance of mitigating adolescent obesity rates and managing risk factors for kidney disease in adolescents with high BMI,” the authors report.

“The association was evident even in persons with high-normal BMI in adolescence, was more pronounced in men, and appeared before the age of 30 years,” they say.

“Given the increasing obesity rates among adolescents, our findings are a harbinger of the potentially preventable increasing burden of CKD and subsequent cardiovascular disease.”

SOURCE

The study was conducted by first author Avishai M. Tsur, MD, of the Israel Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Tel Hashomer, Ramat Gan, Israel and Department of Military Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel, and colleagues. The study was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS

The study lacked longitudinal data on clinical and lifestyle factors, including stress, diet and physical activity. While adolescents were screened using urine dipstick, a lack of serum creatinine measurements could have missed some adolescents with reduced eGFR at the study entry. The generalizability of the results is limited by the lack of people from West Africa and East Asia in the study population.

DISCLOSURES

Coauthor Josef Coresh, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ADA issues new screening, obesity management recommendations

for 2024.

“The Standards of Care are essentially the global guidelines for the care of individuals with diabetes and those at risk,” ADA chief scientific and medical officer Robert Gabbay, MD, PhD, said during a briefing announcing the new Standards.

The document was developed via a scientific literature review by the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee. The panel comprises 21 professionals, including physicians from many specialties, nurse practitioners, certified diabetes care and education specialists, dietitians, and pharmacists. The chair is Nuha A. El Sayed, MD, ADA’s senior vice president of healthcare improvement.

Specific sections of the 2024 document have been endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, and the Obesity Society. It was published on December 11, 2023, as a supplement in Diabetes Care.

An introductory section summarizing the changes for 2024 spans six pages. Those addressed during the briefing included the following:

Heart Failure Screening: Two new recommendations have been added to include screening of adults with diabetes for asymptomatic heart failure by measuring natriuretic peptide levels to facilitate the prevention or progression to symptomatic stages of heart failure.

“This is a really important and exciting area. We know that people with type 2 diabetes in particular are at high risk for heart failure,” Dr. Gabbay said, adding that these recommendations “are to really more aggressively screen those at high risk for heart failure with a simple blood test and, based on those values, then be able to move on to further evaluation and echocardiography, for example. The recommendations are really to screen a broad number of individuals with type 2 diabetes because many are at risk, [particularly] those without symptoms.”

PAD Screening: A new strong recommendation is to screen for PAD with ankle-brachial index testing in asymptomatic people with diabetes who are aged ≥ 50 years and have microvascular disease in any location, foot complications, or any end-organ damage from diabetes. The document also advises consideration of PAD screening for all individuals who have had diabetes for ≥ 10 years.

Dr. Gabbay commented, “We know that amputation rates are rising, unlike many other complications. We know that there are incredible health disparities. Blacks are two to four times more likely than Whites to have an amputation.”

Dr. El Sayed added, “Many patients don’t show the common symptoms of peripheral arterial disease. Screening is the most important way to find out if they have it or not because it can be a very devastating disease.”

Type 1 Diabetes Screening: This involves several new recommendations, including a framework for investigating suspected type 1 diabetes in newly diagnosed adults using islet autoantibody tests and diagnostic criteria for preclinical stages based on the recent approval of teplizumab for delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes.

“Screening and capturing disease earlier so that we can intervene is really an important consideration here. That includes screening for type 1 diabetes and thinking about therapeutic options to delay the development of frank type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Screening first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes is a high priority because they’re at an elevated risk, he added.

Obesity Management: New recommendations here include the use of anthropomorphic measurements beyond body mass index to include waist circumference and waist:hip ratio and individual assessment of body fat mass and distribution.

Individualization of obesity management including behavioral, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches is encouraged. The use of a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and GLP-1 receptor agonist with greater weight loss efficacy is preferred for obesity management in people with diabetes.

“Obesity management is one of the biggest changes over this last year,” Dr. Gabbay commented.

Other New Recommendations: Among the many other revisions in the 2024 document are new recommendations about regular evaluation and treatment for bone health, assessment of disability and guidance for referral, and alignment of guidance for liver disease screening and management with those of other professional societies. Regarding the last item, Dr. Gabbay noted, “I don’t think it’s gotten the attention it deserves. Diabetes and obesity are becoming the leading causes of liver disease.”

Clinicians can also download the Standards of Care app on their smartphones. “That can be really helpful when questions come up since you can’t remember everything in there. Here you can look it up in a matter of seconds,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Dr. El Sayed added that asking patients about their priorities is also important. “If they aren’t brought up during the visit, it’s unlikely to be as fruitful as it should be.”

Dr. El Sayed has no disclosures. Dr. Gabbay serves as a consultant and/or advisor for HealthReveal, Lark Technologies, Onduo, StartUp Health, Sweetech, and Vida Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

for 2024.

“The Standards of Care are essentially the global guidelines for the care of individuals with diabetes and those at risk,” ADA chief scientific and medical officer Robert Gabbay, MD, PhD, said during a briefing announcing the new Standards.

The document was developed via a scientific literature review by the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee. The panel comprises 21 professionals, including physicians from many specialties, nurse practitioners, certified diabetes care and education specialists, dietitians, and pharmacists. The chair is Nuha A. El Sayed, MD, ADA’s senior vice president of healthcare improvement.

Specific sections of the 2024 document have been endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, and the Obesity Society. It was published on December 11, 2023, as a supplement in Diabetes Care.

An introductory section summarizing the changes for 2024 spans six pages. Those addressed during the briefing included the following:

Heart Failure Screening: Two new recommendations have been added to include screening of adults with diabetes for asymptomatic heart failure by measuring natriuretic peptide levels to facilitate the prevention or progression to symptomatic stages of heart failure.

“This is a really important and exciting area. We know that people with type 2 diabetes in particular are at high risk for heart failure,” Dr. Gabbay said, adding that these recommendations “are to really more aggressively screen those at high risk for heart failure with a simple blood test and, based on those values, then be able to move on to further evaluation and echocardiography, for example. The recommendations are really to screen a broad number of individuals with type 2 diabetes because many are at risk, [particularly] those without symptoms.”

PAD Screening: A new strong recommendation is to screen for PAD with ankle-brachial index testing in asymptomatic people with diabetes who are aged ≥ 50 years and have microvascular disease in any location, foot complications, or any end-organ damage from diabetes. The document also advises consideration of PAD screening for all individuals who have had diabetes for ≥ 10 years.

Dr. Gabbay commented, “We know that amputation rates are rising, unlike many other complications. We know that there are incredible health disparities. Blacks are two to four times more likely than Whites to have an amputation.”

Dr. El Sayed added, “Many patients don’t show the common symptoms of peripheral arterial disease. Screening is the most important way to find out if they have it or not because it can be a very devastating disease.”

Type 1 Diabetes Screening: This involves several new recommendations, including a framework for investigating suspected type 1 diabetes in newly diagnosed adults using islet autoantibody tests and diagnostic criteria for preclinical stages based on the recent approval of teplizumab for delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes.

“Screening and capturing disease earlier so that we can intervene is really an important consideration here. That includes screening for type 1 diabetes and thinking about therapeutic options to delay the development of frank type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Screening first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes is a high priority because they’re at an elevated risk, he added.

Obesity Management: New recommendations here include the use of anthropomorphic measurements beyond body mass index to include waist circumference and waist:hip ratio and individual assessment of body fat mass and distribution.

Individualization of obesity management including behavioral, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches is encouraged. The use of a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and GLP-1 receptor agonist with greater weight loss efficacy is preferred for obesity management in people with diabetes.

“Obesity management is one of the biggest changes over this last year,” Dr. Gabbay commented.

Other New Recommendations: Among the many other revisions in the 2024 document are new recommendations about regular evaluation and treatment for bone health, assessment of disability and guidance for referral, and alignment of guidance for liver disease screening and management with those of other professional societies. Regarding the last item, Dr. Gabbay noted, “I don’t think it’s gotten the attention it deserves. Diabetes and obesity are becoming the leading causes of liver disease.”

Clinicians can also download the Standards of Care app on their smartphones. “That can be really helpful when questions come up since you can’t remember everything in there. Here you can look it up in a matter of seconds,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Dr. El Sayed added that asking patients about their priorities is also important. “If they aren’t brought up during the visit, it’s unlikely to be as fruitful as it should be.”

Dr. El Sayed has no disclosures. Dr. Gabbay serves as a consultant and/or advisor for HealthReveal, Lark Technologies, Onduo, StartUp Health, Sweetech, and Vida Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

for 2024.

“The Standards of Care are essentially the global guidelines for the care of individuals with diabetes and those at risk,” ADA chief scientific and medical officer Robert Gabbay, MD, PhD, said during a briefing announcing the new Standards.

The document was developed via a scientific literature review by the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee. The panel comprises 21 professionals, including physicians from many specialties, nurse practitioners, certified diabetes care and education specialists, dietitians, and pharmacists. The chair is Nuha A. El Sayed, MD, ADA’s senior vice president of healthcare improvement.

Specific sections of the 2024 document have been endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, and the Obesity Society. It was published on December 11, 2023, as a supplement in Diabetes Care.

An introductory section summarizing the changes for 2024 spans six pages. Those addressed during the briefing included the following:

Heart Failure Screening: Two new recommendations have been added to include screening of adults with diabetes for asymptomatic heart failure by measuring natriuretic peptide levels to facilitate the prevention or progression to symptomatic stages of heart failure.

“This is a really important and exciting area. We know that people with type 2 diabetes in particular are at high risk for heart failure,” Dr. Gabbay said, adding that these recommendations “are to really more aggressively screen those at high risk for heart failure with a simple blood test and, based on those values, then be able to move on to further evaluation and echocardiography, for example. The recommendations are really to screen a broad number of individuals with type 2 diabetes because many are at risk, [particularly] those without symptoms.”

PAD Screening: A new strong recommendation is to screen for PAD with ankle-brachial index testing in asymptomatic people with diabetes who are aged ≥ 50 years and have microvascular disease in any location, foot complications, or any end-organ damage from diabetes. The document also advises consideration of PAD screening for all individuals who have had diabetes for ≥ 10 years.

Dr. Gabbay commented, “We know that amputation rates are rising, unlike many other complications. We know that there are incredible health disparities. Blacks are two to four times more likely than Whites to have an amputation.”

Dr. El Sayed added, “Many patients don’t show the common symptoms of peripheral arterial disease. Screening is the most important way to find out if they have it or not because it can be a very devastating disease.”

Type 1 Diabetes Screening: This involves several new recommendations, including a framework for investigating suspected type 1 diabetes in newly diagnosed adults using islet autoantibody tests and diagnostic criteria for preclinical stages based on the recent approval of teplizumab for delaying the onset of type 1 diabetes.

“Screening and capturing disease earlier so that we can intervene is really an important consideration here. That includes screening for type 1 diabetes and thinking about therapeutic options to delay the development of frank type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Screening first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes is a high priority because they’re at an elevated risk, he added.

Obesity Management: New recommendations here include the use of anthropomorphic measurements beyond body mass index to include waist circumference and waist:hip ratio and individual assessment of body fat mass and distribution.

Individualization of obesity management including behavioral, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches is encouraged. The use of a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and GLP-1 receptor agonist with greater weight loss efficacy is preferred for obesity management in people with diabetes.

“Obesity management is one of the biggest changes over this last year,” Dr. Gabbay commented.

Other New Recommendations: Among the many other revisions in the 2024 document are new recommendations about regular evaluation and treatment for bone health, assessment of disability and guidance for referral, and alignment of guidance for liver disease screening and management with those of other professional societies. Regarding the last item, Dr. Gabbay noted, “I don’t think it’s gotten the attention it deserves. Diabetes and obesity are becoming the leading causes of liver disease.”

Clinicians can also download the Standards of Care app on their smartphones. “That can be really helpful when questions come up since you can’t remember everything in there. Here you can look it up in a matter of seconds,” Dr. Gabbay said.

Dr. El Sayed added that asking patients about their priorities is also important. “If they aren’t brought up during the visit, it’s unlikely to be as fruitful as it should be.”

Dr. El Sayed has no disclosures. Dr. Gabbay serves as a consultant and/or advisor for HealthReveal, Lark Technologies, Onduo, StartUp Health, Sweetech, and Vida Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MASLD often is worse in slim patients

PARIS — Although metabolic liver diseases are mainly seen in patients with obesity or type 2 diabetes, studies have shown that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, recently renamed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), also affects slim patients. Moreover, the condition could be particularly severe in this population.

A recent study carried out using data from the French Constance cohort showed that of the 25,753 patients with MASLD, 16.3% were lean (BMI of less than 25 kg/m²). In addition, 50% of these patients had no metabolic risk factors.

These slim patients with MASLD were most often young patients, for the most part female, and less likely to present with symptoms of metabolic syndrome. Asian patients were overrepresented in this group.

“These patients probably have genetic and/or environmental risk factors,” commented senior author Lawrence Serfaty, MD, PhD, head of the metabolic liver unit at the new Strasbourg public hospital, during a press conference at the Paris NASH meeting.

The disease was more severe in slim subjects. Overall, 3.6% of the slim subjects had advanced fibrosis (Forns index > 6.9) vs 1.7% of patients with overweight or obesity (P < .001), regardless of demographic variables, metabolic risk factors, and lifestyle. They also had higher alanine aminotransferase levels.

In addition, over the course of a mean follow-up of 3.8 years, liver events (eg, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and liver cancer), chronic kidney diseases, and all-cause mortality were much more common in these patients than in patients with overweight or obesity (adjusted hazard ratios of 5.84, 2.49, and 3.01, respectively). It should be noted that these clinical results were linked to fibrosis severity in both slim and overweight subjects with MASLD.

Nonetheless, cardiovascular events remained more common in patients with overweight or obesity, suggesting that obesity itself is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, regardless of MASLD.

“Armed with these results, which confirm those obtained from other studies, we must seek to understand the pathogenesis of the disease in slim patients and study the role of the microbiota, genetics, and diet, as well as determining the effects of alcohol and tobacco, consumption of which was slightly more common in this subpopulation,” said Dr. Serfaty.

According to the study authors, sarcopenia and bile acids could also be involved in the pathogenesis of MASLD in slim patients. The researchers concluded that “due to the relatively low rate of MASLD in slim subjects, screening should target patients presenting with metabolic anomalies and/or unexplained cytolysis.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition.

PARIS — Although metabolic liver diseases are mainly seen in patients with obesity or type 2 diabetes, studies have shown that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, recently renamed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), also affects slim patients. Moreover, the condition could be particularly severe in this population.

A recent study carried out using data from the French Constance cohort showed that of the 25,753 patients with MASLD, 16.3% were lean (BMI of less than 25 kg/m²). In addition, 50% of these patients had no metabolic risk factors.

These slim patients with MASLD were most often young patients, for the most part female, and less likely to present with symptoms of metabolic syndrome. Asian patients were overrepresented in this group.

“These patients probably have genetic and/or environmental risk factors,” commented senior author Lawrence Serfaty, MD, PhD, head of the metabolic liver unit at the new Strasbourg public hospital, during a press conference at the Paris NASH meeting.

The disease was more severe in slim subjects. Overall, 3.6% of the slim subjects had advanced fibrosis (Forns index > 6.9) vs 1.7% of patients with overweight or obesity (P < .001), regardless of demographic variables, metabolic risk factors, and lifestyle. They also had higher alanine aminotransferase levels.

In addition, over the course of a mean follow-up of 3.8 years, liver events (eg, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and liver cancer), chronic kidney diseases, and all-cause mortality were much more common in these patients than in patients with overweight or obesity (adjusted hazard ratios of 5.84, 2.49, and 3.01, respectively). It should be noted that these clinical results were linked to fibrosis severity in both slim and overweight subjects with MASLD.

Nonetheless, cardiovascular events remained more common in patients with overweight or obesity, suggesting that obesity itself is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, regardless of MASLD.

“Armed with these results, which confirm those obtained from other studies, we must seek to understand the pathogenesis of the disease in slim patients and study the role of the microbiota, genetics, and diet, as well as determining the effects of alcohol and tobacco, consumption of which was slightly more common in this subpopulation,” said Dr. Serfaty.

According to the study authors, sarcopenia and bile acids could also be involved in the pathogenesis of MASLD in slim patients. The researchers concluded that “due to the relatively low rate of MASLD in slim subjects, screening should target patients presenting with metabolic anomalies and/or unexplained cytolysis.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition.

PARIS — Although metabolic liver diseases are mainly seen in patients with obesity or type 2 diabetes, studies have shown that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, recently renamed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), also affects slim patients. Moreover, the condition could be particularly severe in this population.

A recent study carried out using data from the French Constance cohort showed that of the 25,753 patients with MASLD, 16.3% were lean (BMI of less than 25 kg/m²). In addition, 50% of these patients had no metabolic risk factors.

These slim patients with MASLD were most often young patients, for the most part female, and less likely to present with symptoms of metabolic syndrome. Asian patients were overrepresented in this group.

“These patients probably have genetic and/or environmental risk factors,” commented senior author Lawrence Serfaty, MD, PhD, head of the metabolic liver unit at the new Strasbourg public hospital, during a press conference at the Paris NASH meeting.

The disease was more severe in slim subjects. Overall, 3.6% of the slim subjects had advanced fibrosis (Forns index > 6.9) vs 1.7% of patients with overweight or obesity (P < .001), regardless of demographic variables, metabolic risk factors, and lifestyle. They also had higher alanine aminotransferase levels.

In addition, over the course of a mean follow-up of 3.8 years, liver events (eg, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, and liver cancer), chronic kidney diseases, and all-cause mortality were much more common in these patients than in patients with overweight or obesity (adjusted hazard ratios of 5.84, 2.49, and 3.01, respectively). It should be noted that these clinical results were linked to fibrosis severity in both slim and overweight subjects with MASLD.

Nonetheless, cardiovascular events remained more common in patients with overweight or obesity, suggesting that obesity itself is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, regardless of MASLD.

“Armed with these results, which confirm those obtained from other studies, we must seek to understand the pathogenesis of the disease in slim patients and study the role of the microbiota, genetics, and diet, as well as determining the effects of alcohol and tobacco, consumption of which was slightly more common in this subpopulation,” said Dr. Serfaty.