User login

Would you prescribe antenatal steroids to a pregnant patient at high risk for delivering at 22 weeks’ gestation?

For many decades, the limit of newborn viability was at approximately 24 weeks’ gestation. Recent advances in pregnancy and neonatal care suggest that the new limit of viability is 22 (22 weeks and 0 days to 22 weeks and 6 days) or 23 (23 weeks and 0 days to 23 weeks and 6 days) weeks of gestation. In addition, data from observational cohort studies indicate that for infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, survival is dependent on a course of antenatal steroids administered prior to birth plus intensive respiratory and cardiovascular support at delivery and in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Antenatal steroids: Critical for survival at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation

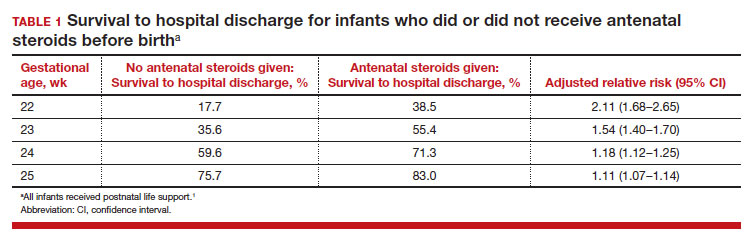

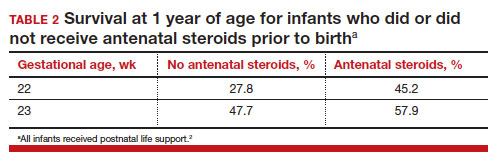

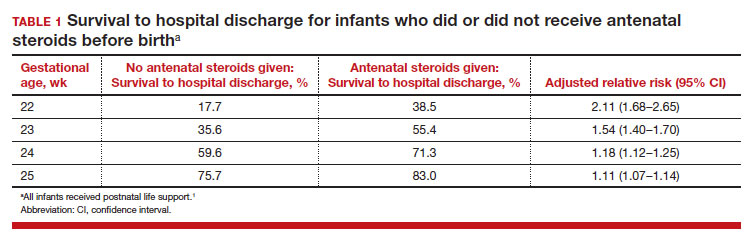

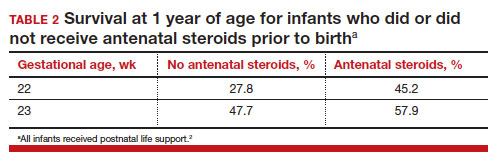

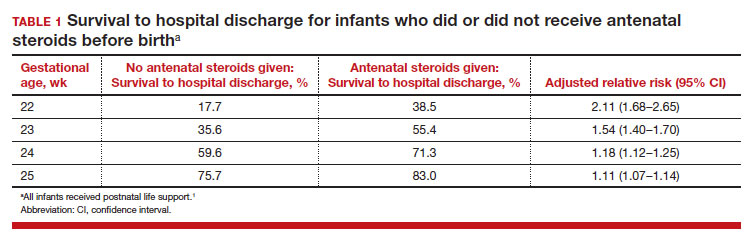

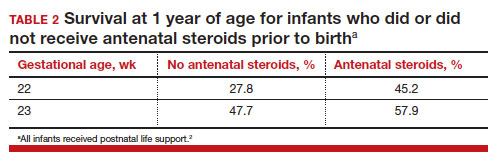

Most studies of birth outcomes at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation rely on observational cohorts where unmeasured differences among the maternal-fetal dyads that received or did not receive a specific treatment confounds the interpretation of the data. However, data from multiple large observational cohorts suggest that between 22 and 24 weeks of gestation, completion of a course of antenatal steroids will optimize infant outcomes. Particularly noteworthy was the observation that the incremental survival benefit of antenatal steroids was greatest at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation (TABLE 1).1 Similar results have been reported by Rossi and colleagues (TABLE 2).2

The importance of a completed course of antenatal steroids before birth was confirmed in another cohort study of 431 infants born in 2016 to 2019 at 22 weeks and 0 days’ to 23 weeks and 6 days’ gestation.3 Survival to discharge occurred in 53.9% of infants who received a full course of antenatal steroids before birth and 35.5% among those who did not receive antenatal steroids..3 Survival to discharge without major neonatal morbidities was 26.9% in those who received a full course of antenatal steroids and 10% among those who did not. In this cohort, major neonatal morbidities included severe intracranial hemorrhage, cystic periventricular leukomalacia, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, surgical necrotizing enterocolitis, or severe retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against antenatal steroids prior to 22 weeks and 0 days gestation.4 However, some neonatologists might recommend that antenatal steroids be given starting at 21 weeks and 5 days of gestation if birth is anticipated in the 22nd week of gestation and the patient prefers aggressive treatment of the newborn.

Active respiratory and cardiovascular support improves newborn outcomes

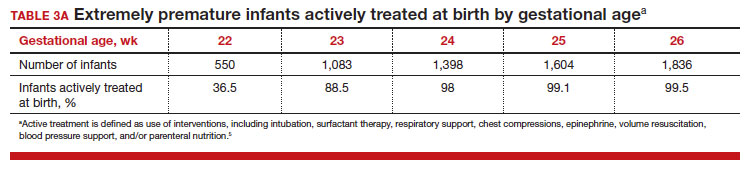

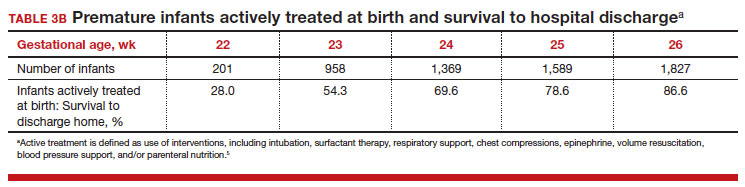

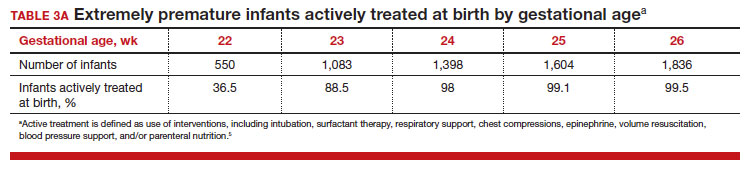

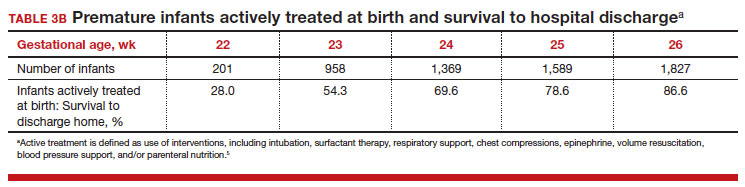

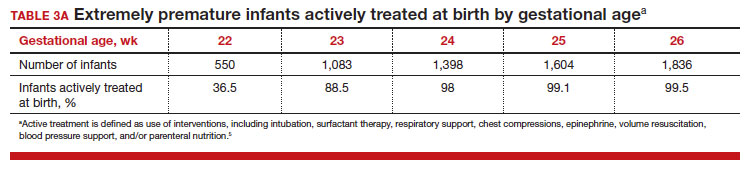

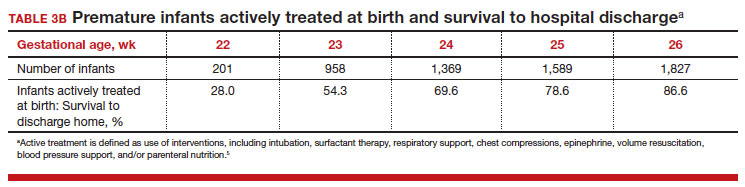

To maximize survival, infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation always require intensive active treatment at birth and in the following days in the NICU. Active treatment may include respiratory support, surfactant treatment, pressors, closure of a patent ductus arteriosus, transfusion of red blood cells, and parenteral nutrition. In one observational cohort study, active treatment at birth was not routinely provided at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation but was routinely provided at later gestational ages (TABLE 3A).5 Not surprisingly, active treatment, especially at early gestational ages, is associated with improved survival to discharge. For example, at 22 weeks’ gestation, survival to discharge in infants who received or did not receive intensive active treatment was 28% and 0%, respectively.5 However, specific clinical characteristics of the pregnant patient and newborn may have influenced which infants were actively treated, confounding interpretation of the observation. In this cohort of extremely premature newborns, survival to hospital discharge increased substantially between 22 weeks and 26 weeks of gestational age (TABLE 3B).5

Many of the surviving infants needed chronic support treatment. Among surviving infants born at 22 weeks and 26 weeks, chronic support treatments were being used by 22.6% and 10.6% of infants, respectively, 2 years after birth.5 For surviving infants born at 22 weeks, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrostomy or feeding tube (19.4%), oxygen (9.7%), pulse oximeter (9.7%), and/or tracheostomy (3.2%). For surviving infants born at 26 weeks’ gestation, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrotomy or feeding tube (8.5%), pulse oximeter (4.4%), oxygen (3.2%), tracheostomy (2.3%), an apnea monitor (1.5%), and/or ventilator or continuous positive airway pressure (1.1%).5

Continue to: Evolving improvement in infant outcomes...

Evolving improvement in infant outcomes

In 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy went into preterm labor at 34 weeks of gestation and delivered her son Patrick at a community facility. Due to severe respiratory distress syndrome, Patrick was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital, and he died shortly thereafter.6 Sixty years later, due to advances in obstetric and neonatal care, death from respiratory distress syndrome at 34 weeks of gestation is uncommon in the United States.

Infant outcomes following birth at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation continue to improve. An observational cohort study from Sweden reported that at 22 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 10% and 30%, respectively.7 Similarly, at 23 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 52% and 61%, respectively.7 However, most of the surviving infants in this cohort had one or more major neonatal morbidities, including intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4; periventricular leukomalacia; necrotizing enterocolitis; retinopathy of prematurity grade 3, 4, or 5; or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia.7

In a cohort of infants born in Japan at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, there was a notable decrease in major neurodisability at 3 years of age for births occurring in 2 epochs, 2003 to 2007 and 2008 to 2012.8 When comparing outcomes in 2003 to 2007 versus 2008 to 2012, the change in rate of various major complications included the following: cerebral palsy (15.9% vs 9.5%), visual impairment (13.6% vs 4.4%), blindness (4.8% vs 1.3%), and hearing impairment (2.6% vs 1.0%). In contrast, the rate of cognitive impairment, defined as less than 70% of standard test performance for chronological age, was similar in the 2 time periods (36.5% and 37.9%, respectively).8 Based on data reported between 2000 and 2020, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Backes and colleagues concluded that there has been substantial improvement in the survival of infants born at 22 weeks of gestation.9

The small baby unit

A feature of modern medicine is the relentless evolution of new clinical subspecialties and sub-subspecialties. NICUs evolved from newborn nurseries to serve the needs of the most severely ill newborns, with care provided by a cadre of highly trained subspecialized neonatologists and neonatal nurses. A new era is dawning, with some NICUs developing a sub-subspecialized small baby unit to care for infants born between 22 and 26 weeks of gestation. These units often are staffed by clinicians with a specific interest in optimizing the care of extremely preterm infants, providing continuity of care over a long hospitalization.10 The benefits of a small baby unit may include:

- relentless standardization and adherence to the best intensive care practices

- daily use of checklists

- strict adherence to central line care

- timely extubation and transition to continuous positive airway pressure

- adherence to breastfeeding guidelines

- limiting the number of clinicians responsible for the patient

- promotion of kangaroo care

- avoidance of noxious stimuli.10,11

Continue to: Ethical and clinical issues...

Ethical and clinical issues

Providing clinical care to infants born at the edge of viability is challenging and raises many ethical and clinical concerns.12,13 For an infant born at the edge of viability, clinicians and parents do not want to initiate a care process that improves survival but results in an extremely poor quality of life. At the same time, clinicians and parents do not want to withhold care that could help an extremely premature newborn survive and thrive. Consequently, the counseling process is complex and requires coordination between the obstetrical and neonatology disciplines, involving physicians and nurses from both. A primary consideration in deciding to institute active treatment at birth is the preference of the pregnant patient and the patient’s trusted family members. A thorough discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of this editorial. ACOG provides detailed advice about the approach to counseling patients who face the possibility of a periviable birth.14

To help standardize the counseling process, institutions may find it helpful to recommend that clinicians consistently use a calculator to provide newborn outcome data to patients. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Extremely Preterm Birth Outcomes calculator uses the following inputs:

- gestational age

- estimated birth weight

- sex

- singleton/multiple gestation

- antenatal steroid treatment.

It also provides the following outputs as percentages:

- survival with active treatment at birth

- survival without active treatment at birth

- profound neurodevelopmental impairment

- moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment

- blindness

- deafness

- moderate to severe cerebral palsy

- cognitive developmental delay.15

A full assessment of all known clinical factors should influence the interpretation of the output from the clinical calculator. An alternativeis to use data from the Vermont Oxford Network. NICUs with sufficient clinical volume may prefer to use their own outcome data in the counseling process.

Institutions and clinical teams may improve the consistency of the counseling process by identifying criteria for 3 main treatment options:

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is not generally offered (eg, <22 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is almost always routinely provided (eg, >25 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where patient preferences are especially important in guiding the use of active treatment.

Most institutions do not routinely offer active treatment of the newborn at a gestational age of less than 22 weeks and 0 days. Instead, comfort care often is provided for these newborns. Most institutions routinely provide active treatment at birth beginning at 24 or 25 weeks’ gestation unless unique risk factors or comorbidities warrant not providing active treatment (TABLE 3A). Some professional societies recommend setting a threshold for recommending active treatment at birth. For example, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine recommends that if there is 50% or higher probability of survival without severe disability, active treatment at birth should be considered because it is in the best interest of the newborn.16 In the hours and days following birth, the clinical course of the newborn greatly influences the treatment plan and care goals. After the initial resuscitation, if the clinical condition of an extremely preterm infant worsens and the prognosis is grim, a pivot to palliative care may be considered.

Final thoughts

Periviability is the earliest stage of fetal development where there is a reasonable chance, but not a high likelihood, of survival outside the womb. For decades, the threshold for periviability was approximately 24 weeks of gestation. With current obstetrical and neonatal practice, the new threshold for periviability is 22 to 23 weeks of gestation, but death prior to hospital discharge occurs in approximately half of these newborns. For the survivors, lifelong neurodevelopmental complications and pulmonary disease are common. Obstetricians play a key role in counseling patients who are at risk of giving birth before 24 weeks of gestation. Given the challenges faced by an infant born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, pregnant patients and trusted family members should approach the decision to actively resuscitate the newborn with caution. However, if the clinical team, patient, and trusted family members agree to pursue active treatment, completion of a course of antenatal steroids and appropriate respiratory and cardiovascular support at birth are key to improving long-term outcomes. ●

- Ehret DEY, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure with survival among infants receiving postnatal life support at 22 to 25 weeks gestation. JAMA Network Open. 2018;E183235.

- Rossi RM, DeFranco EA, Hall ES. Association of antenatal corticosteroid exposure and infant survival at 22 and 23 weeks [published online November 28, 2021]. Am J Perinatol. doi:10.1055/s-004-1740062

- Chawla S, Wyckoff MH, Rysavy MA, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure at 21 to 22 weeks of gestation with neonatal survival and survival without morbidities. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:E2233331.

- Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation. ACOG website. Published September 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.acog .org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal -corticosteroids-at-22-weeks-of-gestation

- Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, et al. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022;327:248-263.

- The tragic death of Patrick, JFK and Jackie’s newborn son, in 1963. Irish Central website. Published November 6, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history /tragic-death-patrick-kennedy-jfk-jackie

- Norman M, Hallberg B, Abrahamsson T, et al. Association between year of birth and 1-year survival among extremely preterm infants in Sweden during 2004-2007 and 2014-2016. JAMA. 2019;32:1188-1199.

- Kono Y, Yonemoto N, Nakanishi H, et al. Changes in survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born at <25 weeks gestation: a retrospective observational study in tertiary centres in Japan. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2018;2:E000211.

- Backes CH, Rivera BK, Pavlek L, et al. Proactive neonatal treatment at 22 weeks of gestation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:158-174.

- Morris M, Cleary JP, Soliman A. Small baby unit improves quality and outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1007-E1015.

- Fathi O, Nelin LD, Shephard EG, et al. Development of a small baby unit to improve outcomes for the extremely premature infant. J Perinatology. 2002;42:157-164.

- Lantos JD. Ethical issues in treatment of babies born at 22 weeks of gestation. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:1155-1157.

- Shinwell ES. Ethics of birth at the limit of viability: the risky business of prediction. Neonatology. 2015;107:317-320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No 6. periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;E187-E199.

- Extremely preterm birth outcomes tool. NICHD website. Updated March 2, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research /supported/EPBO/use#

- Mactier H, Bates SE, Johnston T, et al. Perinatal management of extreme preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation: a framework for practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020;105:F232-F239.

For many decades, the limit of newborn viability was at approximately 24 weeks’ gestation. Recent advances in pregnancy and neonatal care suggest that the new limit of viability is 22 (22 weeks and 0 days to 22 weeks and 6 days) or 23 (23 weeks and 0 days to 23 weeks and 6 days) weeks of gestation. In addition, data from observational cohort studies indicate that for infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, survival is dependent on a course of antenatal steroids administered prior to birth plus intensive respiratory and cardiovascular support at delivery and in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Antenatal steroids: Critical for survival at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation

Most studies of birth outcomes at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation rely on observational cohorts where unmeasured differences among the maternal-fetal dyads that received or did not receive a specific treatment confounds the interpretation of the data. However, data from multiple large observational cohorts suggest that between 22 and 24 weeks of gestation, completion of a course of antenatal steroids will optimize infant outcomes. Particularly noteworthy was the observation that the incremental survival benefit of antenatal steroids was greatest at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation (TABLE 1).1 Similar results have been reported by Rossi and colleagues (TABLE 2).2

The importance of a completed course of antenatal steroids before birth was confirmed in another cohort study of 431 infants born in 2016 to 2019 at 22 weeks and 0 days’ to 23 weeks and 6 days’ gestation.3 Survival to discharge occurred in 53.9% of infants who received a full course of antenatal steroids before birth and 35.5% among those who did not receive antenatal steroids..3 Survival to discharge without major neonatal morbidities was 26.9% in those who received a full course of antenatal steroids and 10% among those who did not. In this cohort, major neonatal morbidities included severe intracranial hemorrhage, cystic periventricular leukomalacia, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, surgical necrotizing enterocolitis, or severe retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against antenatal steroids prior to 22 weeks and 0 days gestation.4 However, some neonatologists might recommend that antenatal steroids be given starting at 21 weeks and 5 days of gestation if birth is anticipated in the 22nd week of gestation and the patient prefers aggressive treatment of the newborn.

Active respiratory and cardiovascular support improves newborn outcomes

To maximize survival, infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation always require intensive active treatment at birth and in the following days in the NICU. Active treatment may include respiratory support, surfactant treatment, pressors, closure of a patent ductus arteriosus, transfusion of red blood cells, and parenteral nutrition. In one observational cohort study, active treatment at birth was not routinely provided at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation but was routinely provided at later gestational ages (TABLE 3A).5 Not surprisingly, active treatment, especially at early gestational ages, is associated with improved survival to discharge. For example, at 22 weeks’ gestation, survival to discharge in infants who received or did not receive intensive active treatment was 28% and 0%, respectively.5 However, specific clinical characteristics of the pregnant patient and newborn may have influenced which infants were actively treated, confounding interpretation of the observation. In this cohort of extremely premature newborns, survival to hospital discharge increased substantially between 22 weeks and 26 weeks of gestational age (TABLE 3B).5

Many of the surviving infants needed chronic support treatment. Among surviving infants born at 22 weeks and 26 weeks, chronic support treatments were being used by 22.6% and 10.6% of infants, respectively, 2 years after birth.5 For surviving infants born at 22 weeks, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrostomy or feeding tube (19.4%), oxygen (9.7%), pulse oximeter (9.7%), and/or tracheostomy (3.2%). For surviving infants born at 26 weeks’ gestation, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrotomy or feeding tube (8.5%), pulse oximeter (4.4%), oxygen (3.2%), tracheostomy (2.3%), an apnea monitor (1.5%), and/or ventilator or continuous positive airway pressure (1.1%).5

Continue to: Evolving improvement in infant outcomes...

Evolving improvement in infant outcomes

In 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy went into preterm labor at 34 weeks of gestation and delivered her son Patrick at a community facility. Due to severe respiratory distress syndrome, Patrick was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital, and he died shortly thereafter.6 Sixty years later, due to advances in obstetric and neonatal care, death from respiratory distress syndrome at 34 weeks of gestation is uncommon in the United States.

Infant outcomes following birth at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation continue to improve. An observational cohort study from Sweden reported that at 22 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 10% and 30%, respectively.7 Similarly, at 23 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 52% and 61%, respectively.7 However, most of the surviving infants in this cohort had one or more major neonatal morbidities, including intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4; periventricular leukomalacia; necrotizing enterocolitis; retinopathy of prematurity grade 3, 4, or 5; or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia.7

In a cohort of infants born in Japan at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, there was a notable decrease in major neurodisability at 3 years of age for births occurring in 2 epochs, 2003 to 2007 and 2008 to 2012.8 When comparing outcomes in 2003 to 2007 versus 2008 to 2012, the change in rate of various major complications included the following: cerebral palsy (15.9% vs 9.5%), visual impairment (13.6% vs 4.4%), blindness (4.8% vs 1.3%), and hearing impairment (2.6% vs 1.0%). In contrast, the rate of cognitive impairment, defined as less than 70% of standard test performance for chronological age, was similar in the 2 time periods (36.5% and 37.9%, respectively).8 Based on data reported between 2000 and 2020, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Backes and colleagues concluded that there has been substantial improvement in the survival of infants born at 22 weeks of gestation.9

The small baby unit

A feature of modern medicine is the relentless evolution of new clinical subspecialties and sub-subspecialties. NICUs evolved from newborn nurseries to serve the needs of the most severely ill newborns, with care provided by a cadre of highly trained subspecialized neonatologists and neonatal nurses. A new era is dawning, with some NICUs developing a sub-subspecialized small baby unit to care for infants born between 22 and 26 weeks of gestation. These units often are staffed by clinicians with a specific interest in optimizing the care of extremely preterm infants, providing continuity of care over a long hospitalization.10 The benefits of a small baby unit may include:

- relentless standardization and adherence to the best intensive care practices

- daily use of checklists

- strict adherence to central line care

- timely extubation and transition to continuous positive airway pressure

- adherence to breastfeeding guidelines

- limiting the number of clinicians responsible for the patient

- promotion of kangaroo care

- avoidance of noxious stimuli.10,11

Continue to: Ethical and clinical issues...

Ethical and clinical issues

Providing clinical care to infants born at the edge of viability is challenging and raises many ethical and clinical concerns.12,13 For an infant born at the edge of viability, clinicians and parents do not want to initiate a care process that improves survival but results in an extremely poor quality of life. At the same time, clinicians and parents do not want to withhold care that could help an extremely premature newborn survive and thrive. Consequently, the counseling process is complex and requires coordination between the obstetrical and neonatology disciplines, involving physicians and nurses from both. A primary consideration in deciding to institute active treatment at birth is the preference of the pregnant patient and the patient’s trusted family members. A thorough discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of this editorial. ACOG provides detailed advice about the approach to counseling patients who face the possibility of a periviable birth.14

To help standardize the counseling process, institutions may find it helpful to recommend that clinicians consistently use a calculator to provide newborn outcome data to patients. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Extremely Preterm Birth Outcomes calculator uses the following inputs:

- gestational age

- estimated birth weight

- sex

- singleton/multiple gestation

- antenatal steroid treatment.

It also provides the following outputs as percentages:

- survival with active treatment at birth

- survival without active treatment at birth

- profound neurodevelopmental impairment

- moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment

- blindness

- deafness

- moderate to severe cerebral palsy

- cognitive developmental delay.15

A full assessment of all known clinical factors should influence the interpretation of the output from the clinical calculator. An alternativeis to use data from the Vermont Oxford Network. NICUs with sufficient clinical volume may prefer to use their own outcome data in the counseling process.

Institutions and clinical teams may improve the consistency of the counseling process by identifying criteria for 3 main treatment options:

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is not generally offered (eg, <22 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is almost always routinely provided (eg, >25 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where patient preferences are especially important in guiding the use of active treatment.

Most institutions do not routinely offer active treatment of the newborn at a gestational age of less than 22 weeks and 0 days. Instead, comfort care often is provided for these newborns. Most institutions routinely provide active treatment at birth beginning at 24 or 25 weeks’ gestation unless unique risk factors or comorbidities warrant not providing active treatment (TABLE 3A). Some professional societies recommend setting a threshold for recommending active treatment at birth. For example, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine recommends that if there is 50% or higher probability of survival without severe disability, active treatment at birth should be considered because it is in the best interest of the newborn.16 In the hours and days following birth, the clinical course of the newborn greatly influences the treatment plan and care goals. After the initial resuscitation, if the clinical condition of an extremely preterm infant worsens and the prognosis is grim, a pivot to palliative care may be considered.

Final thoughts

Periviability is the earliest stage of fetal development where there is a reasonable chance, but not a high likelihood, of survival outside the womb. For decades, the threshold for periviability was approximately 24 weeks of gestation. With current obstetrical and neonatal practice, the new threshold for periviability is 22 to 23 weeks of gestation, but death prior to hospital discharge occurs in approximately half of these newborns. For the survivors, lifelong neurodevelopmental complications and pulmonary disease are common. Obstetricians play a key role in counseling patients who are at risk of giving birth before 24 weeks of gestation. Given the challenges faced by an infant born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, pregnant patients and trusted family members should approach the decision to actively resuscitate the newborn with caution. However, if the clinical team, patient, and trusted family members agree to pursue active treatment, completion of a course of antenatal steroids and appropriate respiratory and cardiovascular support at birth are key to improving long-term outcomes. ●

For many decades, the limit of newborn viability was at approximately 24 weeks’ gestation. Recent advances in pregnancy and neonatal care suggest that the new limit of viability is 22 (22 weeks and 0 days to 22 weeks and 6 days) or 23 (23 weeks and 0 days to 23 weeks and 6 days) weeks of gestation. In addition, data from observational cohort studies indicate that for infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, survival is dependent on a course of antenatal steroids administered prior to birth plus intensive respiratory and cardiovascular support at delivery and in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Antenatal steroids: Critical for survival at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation

Most studies of birth outcomes at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation rely on observational cohorts where unmeasured differences among the maternal-fetal dyads that received or did not receive a specific treatment confounds the interpretation of the data. However, data from multiple large observational cohorts suggest that between 22 and 24 weeks of gestation, completion of a course of antenatal steroids will optimize infant outcomes. Particularly noteworthy was the observation that the incremental survival benefit of antenatal steroids was greatest at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation (TABLE 1).1 Similar results have been reported by Rossi and colleagues (TABLE 2).2

The importance of a completed course of antenatal steroids before birth was confirmed in another cohort study of 431 infants born in 2016 to 2019 at 22 weeks and 0 days’ to 23 weeks and 6 days’ gestation.3 Survival to discharge occurred in 53.9% of infants who received a full course of antenatal steroids before birth and 35.5% among those who did not receive antenatal steroids..3 Survival to discharge without major neonatal morbidities was 26.9% in those who received a full course of antenatal steroids and 10% among those who did not. In this cohort, major neonatal morbidities included severe intracranial hemorrhage, cystic periventricular leukomalacia, severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, surgical necrotizing enterocolitis, or severe retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against antenatal steroids prior to 22 weeks and 0 days gestation.4 However, some neonatologists might recommend that antenatal steroids be given starting at 21 weeks and 5 days of gestation if birth is anticipated in the 22nd week of gestation and the patient prefers aggressive treatment of the newborn.

Active respiratory and cardiovascular support improves newborn outcomes

To maximize survival, infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation always require intensive active treatment at birth and in the following days in the NICU. Active treatment may include respiratory support, surfactant treatment, pressors, closure of a patent ductus arteriosus, transfusion of red blood cells, and parenteral nutrition. In one observational cohort study, active treatment at birth was not routinely provided at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation but was routinely provided at later gestational ages (TABLE 3A).5 Not surprisingly, active treatment, especially at early gestational ages, is associated with improved survival to discharge. For example, at 22 weeks’ gestation, survival to discharge in infants who received or did not receive intensive active treatment was 28% and 0%, respectively.5 However, specific clinical characteristics of the pregnant patient and newborn may have influenced which infants were actively treated, confounding interpretation of the observation. In this cohort of extremely premature newborns, survival to hospital discharge increased substantially between 22 weeks and 26 weeks of gestational age (TABLE 3B).5

Many of the surviving infants needed chronic support treatment. Among surviving infants born at 22 weeks and 26 weeks, chronic support treatments were being used by 22.6% and 10.6% of infants, respectively, 2 years after birth.5 For surviving infants born at 22 weeks, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrostomy or feeding tube (19.4%), oxygen (9.7%), pulse oximeter (9.7%), and/or tracheostomy (3.2%). For surviving infants born at 26 weeks’ gestation, the specific chronic support treatments included gastrotomy or feeding tube (8.5%), pulse oximeter (4.4%), oxygen (3.2%), tracheostomy (2.3%), an apnea monitor (1.5%), and/or ventilator or continuous positive airway pressure (1.1%).5

Continue to: Evolving improvement in infant outcomes...

Evolving improvement in infant outcomes

In 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy went into preterm labor at 34 weeks of gestation and delivered her son Patrick at a community facility. Due to severe respiratory distress syndrome, Patrick was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital, and he died shortly thereafter.6 Sixty years later, due to advances in obstetric and neonatal care, death from respiratory distress syndrome at 34 weeks of gestation is uncommon in the United States.

Infant outcomes following birth at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation continue to improve. An observational cohort study from Sweden reported that at 22 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 10% and 30%, respectively.7 Similarly, at 23 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of live-born infants who survived to 1-year post birth in 2004 to 2007 and 2014 to 2016 was 52% and 61%, respectively.7 However, most of the surviving infants in this cohort had one or more major neonatal morbidities, including intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4; periventricular leukomalacia; necrotizing enterocolitis; retinopathy of prematurity grade 3, 4, or 5; or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia.7

In a cohort of infants born in Japan at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, there was a notable decrease in major neurodisability at 3 years of age for births occurring in 2 epochs, 2003 to 2007 and 2008 to 2012.8 When comparing outcomes in 2003 to 2007 versus 2008 to 2012, the change in rate of various major complications included the following: cerebral palsy (15.9% vs 9.5%), visual impairment (13.6% vs 4.4%), blindness (4.8% vs 1.3%), and hearing impairment (2.6% vs 1.0%). In contrast, the rate of cognitive impairment, defined as less than 70% of standard test performance for chronological age, was similar in the 2 time periods (36.5% and 37.9%, respectively).8 Based on data reported between 2000 and 2020, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Backes and colleagues concluded that there has been substantial improvement in the survival of infants born at 22 weeks of gestation.9

The small baby unit

A feature of modern medicine is the relentless evolution of new clinical subspecialties and sub-subspecialties. NICUs evolved from newborn nurseries to serve the needs of the most severely ill newborns, with care provided by a cadre of highly trained subspecialized neonatologists and neonatal nurses. A new era is dawning, with some NICUs developing a sub-subspecialized small baby unit to care for infants born between 22 and 26 weeks of gestation. These units often are staffed by clinicians with a specific interest in optimizing the care of extremely preterm infants, providing continuity of care over a long hospitalization.10 The benefits of a small baby unit may include:

- relentless standardization and adherence to the best intensive care practices

- daily use of checklists

- strict adherence to central line care

- timely extubation and transition to continuous positive airway pressure

- adherence to breastfeeding guidelines

- limiting the number of clinicians responsible for the patient

- promotion of kangaroo care

- avoidance of noxious stimuli.10,11

Continue to: Ethical and clinical issues...

Ethical and clinical issues

Providing clinical care to infants born at the edge of viability is challenging and raises many ethical and clinical concerns.12,13 For an infant born at the edge of viability, clinicians and parents do not want to initiate a care process that improves survival but results in an extremely poor quality of life. At the same time, clinicians and parents do not want to withhold care that could help an extremely premature newborn survive and thrive. Consequently, the counseling process is complex and requires coordination between the obstetrical and neonatology disciplines, involving physicians and nurses from both. A primary consideration in deciding to institute active treatment at birth is the preference of the pregnant patient and the patient’s trusted family members. A thorough discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of this editorial. ACOG provides detailed advice about the approach to counseling patients who face the possibility of a periviable birth.14

To help standardize the counseling process, institutions may find it helpful to recommend that clinicians consistently use a calculator to provide newborn outcome data to patients. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Extremely Preterm Birth Outcomes calculator uses the following inputs:

- gestational age

- estimated birth weight

- sex

- singleton/multiple gestation

- antenatal steroid treatment.

It also provides the following outputs as percentages:

- survival with active treatment at birth

- survival without active treatment at birth

- profound neurodevelopmental impairment

- moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment

- blindness

- deafness

- moderate to severe cerebral palsy

- cognitive developmental delay.15

A full assessment of all known clinical factors should influence the interpretation of the output from the clinical calculator. An alternativeis to use data from the Vermont Oxford Network. NICUs with sufficient clinical volume may prefer to use their own outcome data in the counseling process.

Institutions and clinical teams may improve the consistency of the counseling process by identifying criteria for 3 main treatment options:

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is not generally offered (eg, <22 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where active treatment at birth is almost always routinely provided (eg, >25 weeks’ gestation)

- clinical situations where patient preferences are especially important in guiding the use of active treatment.

Most institutions do not routinely offer active treatment of the newborn at a gestational age of less than 22 weeks and 0 days. Instead, comfort care often is provided for these newborns. Most institutions routinely provide active treatment at birth beginning at 24 or 25 weeks’ gestation unless unique risk factors or comorbidities warrant not providing active treatment (TABLE 3A). Some professional societies recommend setting a threshold for recommending active treatment at birth. For example, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine recommends that if there is 50% or higher probability of survival without severe disability, active treatment at birth should be considered because it is in the best interest of the newborn.16 In the hours and days following birth, the clinical course of the newborn greatly influences the treatment plan and care goals. After the initial resuscitation, if the clinical condition of an extremely preterm infant worsens and the prognosis is grim, a pivot to palliative care may be considered.

Final thoughts

Periviability is the earliest stage of fetal development where there is a reasonable chance, but not a high likelihood, of survival outside the womb. For decades, the threshold for periviability was approximately 24 weeks of gestation. With current obstetrical and neonatal practice, the new threshold for periviability is 22 to 23 weeks of gestation, but death prior to hospital discharge occurs in approximately half of these newborns. For the survivors, lifelong neurodevelopmental complications and pulmonary disease are common. Obstetricians play a key role in counseling patients who are at risk of giving birth before 24 weeks of gestation. Given the challenges faced by an infant born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, pregnant patients and trusted family members should approach the decision to actively resuscitate the newborn with caution. However, if the clinical team, patient, and trusted family members agree to pursue active treatment, completion of a course of antenatal steroids and appropriate respiratory and cardiovascular support at birth are key to improving long-term outcomes. ●

- Ehret DEY, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure with survival among infants receiving postnatal life support at 22 to 25 weeks gestation. JAMA Network Open. 2018;E183235.

- Rossi RM, DeFranco EA, Hall ES. Association of antenatal corticosteroid exposure and infant survival at 22 and 23 weeks [published online November 28, 2021]. Am J Perinatol. doi:10.1055/s-004-1740062

- Chawla S, Wyckoff MH, Rysavy MA, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure at 21 to 22 weeks of gestation with neonatal survival and survival without morbidities. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:E2233331.

- Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation. ACOG website. Published September 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.acog .org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal -corticosteroids-at-22-weeks-of-gestation

- Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, et al. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022;327:248-263.

- The tragic death of Patrick, JFK and Jackie’s newborn son, in 1963. Irish Central website. Published November 6, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history /tragic-death-patrick-kennedy-jfk-jackie

- Norman M, Hallberg B, Abrahamsson T, et al. Association between year of birth and 1-year survival among extremely preterm infants in Sweden during 2004-2007 and 2014-2016. JAMA. 2019;32:1188-1199.

- Kono Y, Yonemoto N, Nakanishi H, et al. Changes in survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born at <25 weeks gestation: a retrospective observational study in tertiary centres in Japan. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2018;2:E000211.

- Backes CH, Rivera BK, Pavlek L, et al. Proactive neonatal treatment at 22 weeks of gestation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:158-174.

- Morris M, Cleary JP, Soliman A. Small baby unit improves quality and outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1007-E1015.

- Fathi O, Nelin LD, Shephard EG, et al. Development of a small baby unit to improve outcomes for the extremely premature infant. J Perinatology. 2002;42:157-164.

- Lantos JD. Ethical issues in treatment of babies born at 22 weeks of gestation. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:1155-1157.

- Shinwell ES. Ethics of birth at the limit of viability: the risky business of prediction. Neonatology. 2015;107:317-320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No 6. periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;E187-E199.

- Extremely preterm birth outcomes tool. NICHD website. Updated March 2, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research /supported/EPBO/use#

- Mactier H, Bates SE, Johnston T, et al. Perinatal management of extreme preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation: a framework for practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020;105:F232-F239.

- Ehret DEY, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure with survival among infants receiving postnatal life support at 22 to 25 weeks gestation. JAMA Network Open. 2018;E183235.

- Rossi RM, DeFranco EA, Hall ES. Association of antenatal corticosteroid exposure and infant survival at 22 and 23 weeks [published online November 28, 2021]. Am J Perinatol. doi:10.1055/s-004-1740062

- Chawla S, Wyckoff MH, Rysavy MA, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure at 21 to 22 weeks of gestation with neonatal survival and survival without morbidities. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5:E2233331.

- Use of antenatal corticosteroids at 22 weeks of gestation. ACOG website. Published September 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.acog .org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice -advisory/articles/2021/09/use-of-antenatal -corticosteroids-at-22-weeks-of-gestation

- Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, et al. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022;327:248-263.

- The tragic death of Patrick, JFK and Jackie’s newborn son, in 1963. Irish Central website. Published November 6, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history /tragic-death-patrick-kennedy-jfk-jackie

- Norman M, Hallberg B, Abrahamsson T, et al. Association between year of birth and 1-year survival among extremely preterm infants in Sweden during 2004-2007 and 2014-2016. JAMA. 2019;32:1188-1199.

- Kono Y, Yonemoto N, Nakanishi H, et al. Changes in survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born at <25 weeks gestation: a retrospective observational study in tertiary centres in Japan. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2018;2:E000211.

- Backes CH, Rivera BK, Pavlek L, et al. Proactive neonatal treatment at 22 weeks of gestation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:158-174.

- Morris M, Cleary JP, Soliman A. Small baby unit improves quality and outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1007-E1015.

- Fathi O, Nelin LD, Shephard EG, et al. Development of a small baby unit to improve outcomes for the extremely premature infant. J Perinatology. 2002;42:157-164.

- Lantos JD. Ethical issues in treatment of babies born at 22 weeks of gestation. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:1155-1157.

- Shinwell ES. Ethics of birth at the limit of viability: the risky business of prediction. Neonatology. 2015;107:317-320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No 6. periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;E187-E199.

- Extremely preterm birth outcomes tool. NICHD website. Updated March 2, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research /supported/EPBO/use#

- Mactier H, Bates SE, Johnston T, et al. Perinatal management of extreme preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation: a framework for practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020;105:F232-F239.

News & Perspectives from Ob.Gyn. News

DRUGS, PREGNANCY, AND LACTATION

Canadian Task Force recommendation on screening for postpartum depression misses the mark

Director, Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Postpartum/perinatal depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, with a prevalence of 10%-15% based on multiple studies over the last 2 decades. Over those same 2 decades, there has been growing interest and motivation across the country—from small community hospitals to major academic centers—to promote screening. Such screening is integrated into obstetrical practices, typically using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the most widely used validated screen for PPD globally.

As mentioned in previous columns, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for PPD in 2016, which includes screening women at highest risk, and both acutely treating and preventing PPD.

Since then, screening women for a common clinical problem like PPD has been widely adopted by clinicians representing a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary care. Providers who are engaged in the treatment of postpartum women—obstetricians, psychiatrists, doulas, lactation consultants, facilitators of postpartum support groups, and advocacy groups among others—are included.

An open question and one of great concern recently to our group and others has been what happens after screening. It is clear that identification of PPD per se is not necessarily a challenge, and we have multiple effective treatments from antidepressants to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to cognitive-behavioral interventions. There is also a growing number of digital applications aimed at mitigation of depressive symptoms in women with postpartum major depressive disorder. One unanswered question is how to engage women after identification of PPD and how to facilitate access to care in a way that maximizes the likelihood that women who actually are suffering from PPD get adequate treatment.

The “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression. This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians—how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well?

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/drugs-pregnancy-lactation

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Caring for the aging transgender patient

Ob.Gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pennsylvania.

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues. Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life. Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

Continue to: LATEST NEWS...

LATEST NEWS

Study: Prenatal supplements fail to meet nutrient needs

Although drugstore shelves might suggest otherwise,affordable dietary supplements that provide critical nutrients in appropriate doses for pregnant women are virtually nonexistent, researchers have found.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, investigators observed what many physicians have long suspected: Most prenatal vitamins and other supplements do not adequately make up the difference of what food-based intake of nutrients leave lacking. Despite patients believing they are getting everything they need with their product purchase, they fall short of guideline-recommended requirements.

“There is no magic pill,” said Katherine A. Sauder, PhD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, and lead author of the study. “There is no easy answer here.”

The researchers analyzed 24-hour dietary intake data from 2,450 study participants across five states from 2007 to 2019. Dr. Sauder and colleagues focused on six of the more than 20 key nutrients recommended for pregnant people and determined the target dose for vitamin A, vitamin D, folate, calcium, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids.

The researchers tested more than 20,500 dietary supplements, of which 421 were prenatal products. Only 69 products—three prenatal—included all six nutrients. Just seven products —two prenatal—contained target doses for five nutrients. Only one product, which was not marketed as prenatal, contained target doses for all six nutrients but required seven tablets a serving and cost patients approximately $200 a month.

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

Researchers have found for the first time that COVID infection has crossed the placenta and caused brain damage in two newborns, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics.

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD,with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Perinatal HIV nearly eradicated in U.S.

Rates of perinatal HIV have dropped so much that the disease is effectively eliminated in the United States, with less than 1 baby for every 100,000 live births having the virus, a new study released by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finds.

The report marks significant progress on the U.S. government’s goal to eradicate perinatal HIV, an immune-weakening and potentially deadly virus that is passed from mother to baby during pregnancy. Just 32 children in the country were diagnosed in 2019, compared with twice as many in 2010, according to the CDC.

Mothers who are HIV positive can prevent transmission of the infection by receiving antiretroviral therapy, according to Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco’s division of HIV, infectious disease and global medicine.

Dr. Gandhi said she could recall only one case of perinatal HIV in the San Francisco area over the last decade.

DRUGS, PREGNANCY, AND LACTATION

Canadian Task Force recommendation on screening for postpartum depression misses the mark

Director, Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Postpartum/perinatal depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, with a prevalence of 10%-15% based on multiple studies over the last 2 decades. Over those same 2 decades, there has been growing interest and motivation across the country—from small community hospitals to major academic centers—to promote screening. Such screening is integrated into obstetrical practices, typically using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the most widely used validated screen for PPD globally.

As mentioned in previous columns, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for PPD in 2016, which includes screening women at highest risk, and both acutely treating and preventing PPD.

Since then, screening women for a common clinical problem like PPD has been widely adopted by clinicians representing a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary care. Providers who are engaged in the treatment of postpartum women—obstetricians, psychiatrists, doulas, lactation consultants, facilitators of postpartum support groups, and advocacy groups among others—are included.

An open question and one of great concern recently to our group and others has been what happens after screening. It is clear that identification of PPD per se is not necessarily a challenge, and we have multiple effective treatments from antidepressants to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to cognitive-behavioral interventions. There is also a growing number of digital applications aimed at mitigation of depressive symptoms in women with postpartum major depressive disorder. One unanswered question is how to engage women after identification of PPD and how to facilitate access to care in a way that maximizes the likelihood that women who actually are suffering from PPD get adequate treatment.

The “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression. This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians—how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well?

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/drugs-pregnancy-lactation

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Caring for the aging transgender patient

Ob.Gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pennsylvania.

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues. Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life. Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

Continue to: LATEST NEWS...

LATEST NEWS

Study: Prenatal supplements fail to meet nutrient needs

Although drugstore shelves might suggest otherwise,affordable dietary supplements that provide critical nutrients in appropriate doses for pregnant women are virtually nonexistent, researchers have found.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, investigators observed what many physicians have long suspected: Most prenatal vitamins and other supplements do not adequately make up the difference of what food-based intake of nutrients leave lacking. Despite patients believing they are getting everything they need with their product purchase, they fall short of guideline-recommended requirements.

“There is no magic pill,” said Katherine A. Sauder, PhD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, and lead author of the study. “There is no easy answer here.”

The researchers analyzed 24-hour dietary intake data from 2,450 study participants across five states from 2007 to 2019. Dr. Sauder and colleagues focused on six of the more than 20 key nutrients recommended for pregnant people and determined the target dose for vitamin A, vitamin D, folate, calcium, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids.

The researchers tested more than 20,500 dietary supplements, of which 421 were prenatal products. Only 69 products—three prenatal—included all six nutrients. Just seven products —two prenatal—contained target doses for five nutrients. Only one product, which was not marketed as prenatal, contained target doses for all six nutrients but required seven tablets a serving and cost patients approximately $200 a month.

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

Researchers have found for the first time that COVID infection has crossed the placenta and caused brain damage in two newborns, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics.

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD,with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Perinatal HIV nearly eradicated in U.S.

Rates of perinatal HIV have dropped so much that the disease is effectively eliminated in the United States, with less than 1 baby for every 100,000 live births having the virus, a new study released by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finds.

The report marks significant progress on the U.S. government’s goal to eradicate perinatal HIV, an immune-weakening and potentially deadly virus that is passed from mother to baby during pregnancy. Just 32 children in the country were diagnosed in 2019, compared with twice as many in 2010, according to the CDC.

Mothers who are HIV positive can prevent transmission of the infection by receiving antiretroviral therapy, according to Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco’s division of HIV, infectious disease and global medicine.

Dr. Gandhi said she could recall only one case of perinatal HIV in the San Francisco area over the last decade.

DRUGS, PREGNANCY, AND LACTATION

Canadian Task Force recommendation on screening for postpartum depression misses the mark

Director, Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Postpartum/perinatal depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, with a prevalence of 10%-15% based on multiple studies over the last 2 decades. Over those same 2 decades, there has been growing interest and motivation across the country—from small community hospitals to major academic centers—to promote screening. Such screening is integrated into obstetrical practices, typically using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the most widely used validated screen for PPD globally.

As mentioned in previous columns, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for PPD in 2016, which includes screening women at highest risk, and both acutely treating and preventing PPD.

Since then, screening women for a common clinical problem like PPD has been widely adopted by clinicians representing a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary care. Providers who are engaged in the treatment of postpartum women—obstetricians, psychiatrists, doulas, lactation consultants, facilitators of postpartum support groups, and advocacy groups among others—are included.

An open question and one of great concern recently to our group and others has been what happens after screening. It is clear that identification of PPD per se is not necessarily a challenge, and we have multiple effective treatments from antidepressants to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to cognitive-behavioral interventions. There is also a growing number of digital applications aimed at mitigation of depressive symptoms in women with postpartum major depressive disorder. One unanswered question is how to engage women after identification of PPD and how to facilitate access to care in a way that maximizes the likelihood that women who actually are suffering from PPD get adequate treatment.

The “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression. This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians—how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well?

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/drugs-pregnancy-lactation

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Caring for the aging transgender patient

Ob.Gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pennsylvania.

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues. Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life. Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

Continue to: LATEST NEWS...

LATEST NEWS

Study: Prenatal supplements fail to meet nutrient needs

Although drugstore shelves might suggest otherwise,affordable dietary supplements that provide critical nutrients in appropriate doses for pregnant women are virtually nonexistent, researchers have found.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, investigators observed what many physicians have long suspected: Most prenatal vitamins and other supplements do not adequately make up the difference of what food-based intake of nutrients leave lacking. Despite patients believing they are getting everything they need with their product purchase, they fall short of guideline-recommended requirements.

“There is no magic pill,” said Katherine A. Sauder, PhD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, and lead author of the study. “There is no easy answer here.”

The researchers analyzed 24-hour dietary intake data from 2,450 study participants across five states from 2007 to 2019. Dr. Sauder and colleagues focused on six of the more than 20 key nutrients recommended for pregnant people and determined the target dose for vitamin A, vitamin D, folate, calcium, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids.

The researchers tested more than 20,500 dietary supplements, of which 421 were prenatal products. Only 69 products—three prenatal—included all six nutrients. Just seven products —two prenatal—contained target doses for five nutrients. Only one product, which was not marketed as prenatal, contained target doses for all six nutrients but required seven tablets a serving and cost patients approximately $200 a month.

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

Researchers have found for the first time that COVID infection has crossed the placenta and caused brain damage in two newborns, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics.

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD,with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Perinatal HIV nearly eradicated in U.S.

Rates of perinatal HIV have dropped so much that the disease is effectively eliminated in the United States, with less than 1 baby for every 100,000 live births having the virus, a new study released by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finds.

The report marks significant progress on the U.S. government’s goal to eradicate perinatal HIV, an immune-weakening and potentially deadly virus that is passed from mother to baby during pregnancy. Just 32 children in the country were diagnosed in 2019, compared with twice as many in 2010, according to the CDC.

Mothers who are HIV positive can prevent transmission of the infection by receiving antiretroviral therapy, according to Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco’s division of HIV, infectious disease and global medicine.

Dr. Gandhi said she could recall only one case of perinatal HIV in the San Francisco area over the last decade.

Gestational HTN, preeclampsia worsen long-term risk for ischemic, nonischemic heart failure

, an observational study suggests.

The risks were most pronounced, jumping more than sixfold in the case of ischemic HF, during the first 6 years after the pregnancy. They then receded to plateau at a lower, still significantly elevated level of risk that persisted even years later, in the analysis of women in a Swedish medical birth registry.

The case-matching study compared women with no history of cardiovascular (CV) disease and a first successful pregnancy during which they either developed or did not experience gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

It’s among the first studies to explore the impact of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disease on subsequent HF risk separately for both ischemic and nonischemic HF and to find that the severity of such risk differs for the two HF etiologies, according to a report published in JACC: Heart Failure.

The adjusted risk for any HF during a median of 13 years after the pregnancy rose 70% for those who had developed gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Their risk of nonischemic HF went up 60%, and their risk of ischemic HF more than doubled.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy “are so much more than short-term disorders confined to the pregnancy period. They have long-term implications throughout a lifetime,” lead author Ängla Mantel, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Obstetric history doesn’t figure into any formal HF risk scoring systems, observed Dr. Mantel of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. Still, women who develop gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or other pregnancy complications “should be considered a high-risk population even after the pregnancy and monitored for cardiovascular risk factors regularly throughout life.”

In many studies, she said, “knowledge of women-specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease is poor among both clinicians and patients.” The current findings should help raise awareness about such obstetric risk factors for HF, “especially” in patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which isn’t closely related to a number of traditional CV risk factors.

Even though pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia don’t feature in risk calculators, “they are actually risk enhancers per the 2019 primary prevention guidelines,” Natalie A. Bello, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview.

“We’re working to educate physicians and cardiovascular team members to take a pregnancy history” for risk stratification of women in primary prevention,” said Dr. Bello, director of hypertension research at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The current study, she said, “is an important step” for its finding that hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are associated separately with both ischemic and nonischemic HF.

She pointed out, however, that because the study excluded women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a form of nonischemic HF, it may “underestimate the impact of hypertensive disorders on the short-term risk of nonischemic heart failure.” Women who had peripartum cardiomyopathy were excluded to avoid misclassification of other HF outcomes, the authors stated.

Also, Dr. Bello said, the study’s inclusion of patients with either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia may complicate its interpretation. Compared with the former condition, she said, preeclampsia “involves more inflammation and more endothelial dysfunction. It may cause a different impact on the heart and the vasculature.”

In the analysis, about 79,000 women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were identified among more than 1.4 million primiparous women who entered the Swedish Medical Birth Register over a period of about 30 years. They were matched with about 396,000 women in the registry who had normotensive pregnancies.

Excluded, besides women with peripartum cardiomyopathy, were women with a prepregnancy history of HF, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, or valvular heart disease.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for HF, ischemic HF, and nonischemic HF were significantly elevated over among the women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia compared to those with normotensive pregnancies:

- Any HF: HR, 1.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51-1.91)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.60 (95% CI, 1.40-1.83)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 2.28 (95% CI, 1.74-2.98)

The analyses were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, year of delivery, prepregnancy comorbidities, maternal education level, smoking status, and body mass index.

Sharper risk increases were seen among women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia who delivered prior to gestational week 34:

- Any HF: HR, 2.46 (95% CI, 1.82-3.32)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 2.33 (95% CI, 1.65-3.31)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 3.64 (95% CI, 1.97-6.74)

Risks for HF developing within 6 years of pregnancy characterized by gestational hypertension or preeclampsia were far more pronounced for ischemic HF than for nonischemic HF:

- Any HF: HR, 2.09 (95% CI, 1.52-2.89)

- Nonischemic HF: HR, 1.86 (95% CI, 1.32-2.61)

- Ischemic HF: HR, 6.52 (95% CI, 2.00-12.34).

The study couldn’t directly explore potential mechanisms for the associations between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and different forms of HF, but it may have provided clues, Dr. Mantel said.

The hypertensive disorders and ischemic HF appear to share risk factors that could lead to both conditions, she noted. Also, hypertension itself is a risk factor for ischemic heart disease.

In contrast, “the risk of nonischemic heart failure might be driven by other factors, such as the inflammatory profile, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling induced by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.”

Those disorders, moreover, are associated with cardiac structural changes that are also seen in HFpEF, Dr. Mantel said. And both HFpEF and preeclampsia are characterized by systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

“These pathophysiological similarities,” she proposed, “might explain the link between pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorder and HFpEF.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bello has received grants from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an observational study suggests.

The risks were most pronounced, jumping more than sixfold in the case of ischemic HF, during the first 6 years after the pregnancy. They then receded to plateau at a lower, still significantly elevated level of risk that persisted even years later, in the analysis of women in a Swedish medical birth registry.

The case-matching study compared women with no history of cardiovascular (CV) disease and a first successful pregnancy during which they either developed or did not experience gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.