User login

Study finds COVID-19 boosters don’t increase miscarriage risk

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Abortion restrictions linked to less evidence-based care for miscarriages

BALTIMORE – , according to a cross-sectional study presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The results revealed that “abortion restrictions have far-reaching effects on early pregnancy loss care and on resident education,” the researchers concluded.

“Abortion restrictions don’t just affect people seeking abortions; they affect people also suffering from early pregnancy loss,” Aurora Phillips, MD, an ob.gyn. resident at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview. “It’s harder to make that diagnosis and to be able to offer interventions, and these institutions that had restrictions also were less likely to have mifepristone or office based human aspiration, which are the most efficient and cost-effective interventions that we have.”

For example, less than half the programs surveyed offered mifepristone to help manage a miscarriage, “with availability varying inversely with abortion restrictions,” they found. After considering all characteristics of residency programs, “institutional abortion restrictions and bans were more important than state policies or religious affiliation in determining whether evidence-based early pregnancy loss treatments were available,” the researchers found, though their findings predated the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade. “Training institutions with a commitment to evidence-based family planning care and education are able to ensure access to the most evidence-based, cost-effective, and timely treatments for pregnancy loss even in the face of state abortion restrictions, thereby preserving patient safety, physician competency, and health care system sustainability,” they wrote.

Reduced access leads to higher risk interventions

An estimated 10%-20% of pregnancies result in early miscarriage, totaling more than one million cases in the U.S. each year. But since treatments for miscarriage often overlap with those for abortion, the researchers wondered whether differences existed in how providers managed miscarriages in states or institutions with strict abortion restrictions versus management in hospitals without restrictions.

They also looked at how closely the management strategies adhered to ACOG’s recommendations, which advise that providers consider both ultrasound imaging and other factors, including clinical reasoning and patient preferences, before diagnosing early pregnancy loss and considering possible interventions.

For imaging guidelines, ACOG endorses the criteria established for ultrasound diagnosis of first trimester pregnancy loss from the Society of Radiologists in 2012. But, the authors note, these guidelines are very conservative, exceeding previous measurements that had a 99%-100% predictive value for pregnancy loss, in the interest of “[prioritizing preservation of] fetal potential over facilitating expeditious care.” Hence the reason ACOG advises providers to include clinical judgment and patient preferences in their approach to care.

”In places where abortion is heavily regulated, clinicians managing miscarriages may cautiously rely on the strictest criteria to differentiate early pregnancy loss from potentially viable pregnancy and may not offer certain treatments commonly associated with abortion,” the authors noted. ACOG recommends surgical aspiration and medical treatment with both mifepristone and misoprostol as the safest and most effective options in managing miscarriages.

“Treating early pregnancy loss without the use of mifepristone is more likely to fail, is more likely to require an unscheduled procedure, and people who choose medication management for their miscarriages are usually trying to avoid a procedure, so that is the downside of not using mifepristone,” coauthor Rachel M. Flink-Bochacki, MD, an associate professor at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Office-based uterine aspiration has the same safety profile as uterine aspiration in the operating room minus the risks of anesthesia and also helps patients get in faster because they don’t need to wait for OR time,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki explained. “So again, for a patient who wants an aspiration and does not want to pass the pregnancy at home, not having access to office-based aspiration could lead them to miscarry at home, which has higher risks and is not what they wanted.”

Reduced access to miscarriage care options in ‘hostile’ states

Among all 296 U.S. ob.gyn. residency programs that were contacted between November 2021 and January 2022, half (50.3%) responded to the researchers’ survey about their institutional practices around miscarriage, including location of diagnosis, use of ultrasound diagnostic guidelines, treatment options offered by their institution, and institutional restrictions on abortions based on indication.

The survey also collected characteristics of each program, including its state, setting, religious affiliation, and affiliation with the Ryan Training Program in Abortion and Family Planning. The responding sample had similar geographic distribution and state abortion policies as those who did not respond, but the responding programs were slightly more likely to be academic programs and to be affiliated with the Ryan program.

At the time of the study, prior to the Dobbs ruling, more than half the U.S. states had legislation restricting abortion care, and 57% of national teaching hospitals had internal restrictions that limited care based on gestational age and indication, particularly if the indication was elective, the authors reported. The researchers relied on designations from the Guttmacher Institute in December 2020 to categorize states as “hostile” to abortion (very hostile, hostile, and leans hostile) or non-hostile (neutral, leans supportive, supportive, and very supportive).

Most of the programs (80%) had no religious affiliation, but 11% had a Catholic affiliation and 5% had a different Christian affiliation. Institutional policies either had no restrictions on abortion care (38%), had restrictions (39%) based on certain maternal or fetal indications, or completely banned abortion services unless the mother’s life was threatened (23%). Among the Christian-affiliated programs, 60% had bans and 40% had restrictions.

Half (49.7%) of the responding programs relied rigidly on ultrasound criteria before offering any intervention for suspected early pregnancy loss, regardless of patient preferences. The other half (50.3%) incorporated ultrasound criteria and other factors, including clinical judgment and patient preferences, into a holistic determination of what options to present to the patient.

Before accounting for other factors, the researchers found that only a third (33%) of programs in states with severe abortion restrictions considered additional factors besides imaging when offering patients options for miscarriage management. In states without such abortion restrictions, 79% of programs considered both imaging and other factors (P < .001).

In states with “hostile abortion legislation,” only 32% of the programs used mifepristone for miscarriage management, compared with 75% of the programs in states without onerous abortion restrictions (P < .001). The results were similar for use of office-based suction aspiration: Just under half the programs (48%) in states with severe abortion restrictions included this technique as part of standard miscarriage management, compared with 68% of programs in states without such restrictions (P = .014).

Those findings match up with the experience of Cara Heuser, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist from Salt Lake City, who was not involved in this study.

“We had a lot of restrictions even before Roe fell,” including heavy regulation of mifepristone, Dr. Heuser said in an interview. “In non-restricted states, it’s pretty easy to get, but even before Roe in our state, it was very, very difficult to get institutions and individual doctor’s offices to carry mifepristone to treat miscarriages. They were still treating miscarriages in a way that was known to be less effective.” Adding mifepristone to misoprostol reduces the risk of needing an evacuation surgery procedure, she explained, “so adding the mifepristone makes it safer.”

Institutional policies had the strongest impact

Before accounting for the state a hospital was in, 27% of institutions with restrictive abortion policies looked at more than imaging in determining how to proceed, compared with 88% of institutions without abortion restrictions that included clinical judgment and patient preferences in their management.

After controlling for state policies and affiliation with a family planning training program or a religious entity, the odds of an institution relying solely on imaging guidelines were over 12 times greater for institutions with abortion restrictions or bans (odds ratio, 12.3; 95% confidence interval, 3.2-47.9). Specifically, the odds were 9 times greater for institutions with restrictions and 27 times greater for institutions with bans.

Only 12% of the institutions without restrictions relied solely on ultrasound criteria, compared with 67% of the institutions with restrictions and 82% of the institutions that banned all abortions except to save the life of the pregnant individual (P < .001).

Only one in four (25%) of the programs with institutional abortion restrictions used mifepristone, compared with 86% of unrestricted programs (P < .001), and 40% of programs with institutional abortion restrictions used office-based aspiration, compared with 81% of unrestricted programs (P < .001).

Without access to all evidence-based treatments, doctors are often forced to choose expectant management for miscarriages. “So you’re kind of forced to have them to pass the pregnancy at home, which can be traumatic for patients” if that’s not what they wanted, Dr. Phillips said.

Dr. Flink-Bochacki further noted that this patient population is already particularly vulnerable.

“Especially for patients with early pregnancy loss, it’s such a feeling of powerlessness already, so the mental state that many of these patients are in is already quite fraught,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “Then to not even have power to choose the interventions that you want or to be able to access interventions in a timely fashion because you’re being held to some arbitrary guideline further takes away the power and further exacerbates the trauma of the experience.”

The biggest factor likely driving the reduced access to those interventions is the fear that the care could be confused with providing an abortion instead of simply managing a miscarriage, Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “I think that’s why a lot of these programs don’t have mifepristone and don’t offer outpatient uterine aspiration,” she said. “Because those are so widely used in abortion and the connotation is with abortion, they’re just kind of steering clear of it, but meanwhile, patients with pregnancy loss are suffering because they’re being unnecessarily restrictive.”

The research did not use any external funding, and the authors and Dr. Heuser had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – , according to a cross-sectional study presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The results revealed that “abortion restrictions have far-reaching effects on early pregnancy loss care and on resident education,” the researchers concluded.

“Abortion restrictions don’t just affect people seeking abortions; they affect people also suffering from early pregnancy loss,” Aurora Phillips, MD, an ob.gyn. resident at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview. “It’s harder to make that diagnosis and to be able to offer interventions, and these institutions that had restrictions also were less likely to have mifepristone or office based human aspiration, which are the most efficient and cost-effective interventions that we have.”

For example, less than half the programs surveyed offered mifepristone to help manage a miscarriage, “with availability varying inversely with abortion restrictions,” they found. After considering all characteristics of residency programs, “institutional abortion restrictions and bans were more important than state policies or religious affiliation in determining whether evidence-based early pregnancy loss treatments were available,” the researchers found, though their findings predated the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade. “Training institutions with a commitment to evidence-based family planning care and education are able to ensure access to the most evidence-based, cost-effective, and timely treatments for pregnancy loss even in the face of state abortion restrictions, thereby preserving patient safety, physician competency, and health care system sustainability,” they wrote.

Reduced access leads to higher risk interventions

An estimated 10%-20% of pregnancies result in early miscarriage, totaling more than one million cases in the U.S. each year. But since treatments for miscarriage often overlap with those for abortion, the researchers wondered whether differences existed in how providers managed miscarriages in states or institutions with strict abortion restrictions versus management in hospitals without restrictions.

They also looked at how closely the management strategies adhered to ACOG’s recommendations, which advise that providers consider both ultrasound imaging and other factors, including clinical reasoning and patient preferences, before diagnosing early pregnancy loss and considering possible interventions.

For imaging guidelines, ACOG endorses the criteria established for ultrasound diagnosis of first trimester pregnancy loss from the Society of Radiologists in 2012. But, the authors note, these guidelines are very conservative, exceeding previous measurements that had a 99%-100% predictive value for pregnancy loss, in the interest of “[prioritizing preservation of] fetal potential over facilitating expeditious care.” Hence the reason ACOG advises providers to include clinical judgment and patient preferences in their approach to care.

”In places where abortion is heavily regulated, clinicians managing miscarriages may cautiously rely on the strictest criteria to differentiate early pregnancy loss from potentially viable pregnancy and may not offer certain treatments commonly associated with abortion,” the authors noted. ACOG recommends surgical aspiration and medical treatment with both mifepristone and misoprostol as the safest and most effective options in managing miscarriages.

“Treating early pregnancy loss without the use of mifepristone is more likely to fail, is more likely to require an unscheduled procedure, and people who choose medication management for their miscarriages are usually trying to avoid a procedure, so that is the downside of not using mifepristone,” coauthor Rachel M. Flink-Bochacki, MD, an associate professor at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Office-based uterine aspiration has the same safety profile as uterine aspiration in the operating room minus the risks of anesthesia and also helps patients get in faster because they don’t need to wait for OR time,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki explained. “So again, for a patient who wants an aspiration and does not want to pass the pregnancy at home, not having access to office-based aspiration could lead them to miscarry at home, which has higher risks and is not what they wanted.”

Reduced access to miscarriage care options in ‘hostile’ states

Among all 296 U.S. ob.gyn. residency programs that were contacted between November 2021 and January 2022, half (50.3%) responded to the researchers’ survey about their institutional practices around miscarriage, including location of diagnosis, use of ultrasound diagnostic guidelines, treatment options offered by their institution, and institutional restrictions on abortions based on indication.

The survey also collected characteristics of each program, including its state, setting, religious affiliation, and affiliation with the Ryan Training Program in Abortion and Family Planning. The responding sample had similar geographic distribution and state abortion policies as those who did not respond, but the responding programs were slightly more likely to be academic programs and to be affiliated with the Ryan program.

At the time of the study, prior to the Dobbs ruling, more than half the U.S. states had legislation restricting abortion care, and 57% of national teaching hospitals had internal restrictions that limited care based on gestational age and indication, particularly if the indication was elective, the authors reported. The researchers relied on designations from the Guttmacher Institute in December 2020 to categorize states as “hostile” to abortion (very hostile, hostile, and leans hostile) or non-hostile (neutral, leans supportive, supportive, and very supportive).

Most of the programs (80%) had no religious affiliation, but 11% had a Catholic affiliation and 5% had a different Christian affiliation. Institutional policies either had no restrictions on abortion care (38%), had restrictions (39%) based on certain maternal or fetal indications, or completely banned abortion services unless the mother’s life was threatened (23%). Among the Christian-affiliated programs, 60% had bans and 40% had restrictions.

Half (49.7%) of the responding programs relied rigidly on ultrasound criteria before offering any intervention for suspected early pregnancy loss, regardless of patient preferences. The other half (50.3%) incorporated ultrasound criteria and other factors, including clinical judgment and patient preferences, into a holistic determination of what options to present to the patient.

Before accounting for other factors, the researchers found that only a third (33%) of programs in states with severe abortion restrictions considered additional factors besides imaging when offering patients options for miscarriage management. In states without such abortion restrictions, 79% of programs considered both imaging and other factors (P < .001).

In states with “hostile abortion legislation,” only 32% of the programs used mifepristone for miscarriage management, compared with 75% of the programs in states without onerous abortion restrictions (P < .001). The results were similar for use of office-based suction aspiration: Just under half the programs (48%) in states with severe abortion restrictions included this technique as part of standard miscarriage management, compared with 68% of programs in states without such restrictions (P = .014).

Those findings match up with the experience of Cara Heuser, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist from Salt Lake City, who was not involved in this study.

“We had a lot of restrictions even before Roe fell,” including heavy regulation of mifepristone, Dr. Heuser said in an interview. “In non-restricted states, it’s pretty easy to get, but even before Roe in our state, it was very, very difficult to get institutions and individual doctor’s offices to carry mifepristone to treat miscarriages. They were still treating miscarriages in a way that was known to be less effective.” Adding mifepristone to misoprostol reduces the risk of needing an evacuation surgery procedure, she explained, “so adding the mifepristone makes it safer.”

Institutional policies had the strongest impact

Before accounting for the state a hospital was in, 27% of institutions with restrictive abortion policies looked at more than imaging in determining how to proceed, compared with 88% of institutions without abortion restrictions that included clinical judgment and patient preferences in their management.

After controlling for state policies and affiliation with a family planning training program or a religious entity, the odds of an institution relying solely on imaging guidelines were over 12 times greater for institutions with abortion restrictions or bans (odds ratio, 12.3; 95% confidence interval, 3.2-47.9). Specifically, the odds were 9 times greater for institutions with restrictions and 27 times greater for institutions with bans.

Only 12% of the institutions without restrictions relied solely on ultrasound criteria, compared with 67% of the institutions with restrictions and 82% of the institutions that banned all abortions except to save the life of the pregnant individual (P < .001).

Only one in four (25%) of the programs with institutional abortion restrictions used mifepristone, compared with 86% of unrestricted programs (P < .001), and 40% of programs with institutional abortion restrictions used office-based aspiration, compared with 81% of unrestricted programs (P < .001).

Without access to all evidence-based treatments, doctors are often forced to choose expectant management for miscarriages. “So you’re kind of forced to have them to pass the pregnancy at home, which can be traumatic for patients” if that’s not what they wanted, Dr. Phillips said.

Dr. Flink-Bochacki further noted that this patient population is already particularly vulnerable.

“Especially for patients with early pregnancy loss, it’s such a feeling of powerlessness already, so the mental state that many of these patients are in is already quite fraught,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “Then to not even have power to choose the interventions that you want or to be able to access interventions in a timely fashion because you’re being held to some arbitrary guideline further takes away the power and further exacerbates the trauma of the experience.”

The biggest factor likely driving the reduced access to those interventions is the fear that the care could be confused with providing an abortion instead of simply managing a miscarriage, Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “I think that’s why a lot of these programs don’t have mifepristone and don’t offer outpatient uterine aspiration,” she said. “Because those are so widely used in abortion and the connotation is with abortion, they’re just kind of steering clear of it, but meanwhile, patients with pregnancy loss are suffering because they’re being unnecessarily restrictive.”

The research did not use any external funding, and the authors and Dr. Heuser had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – , according to a cross-sectional study presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The results revealed that “abortion restrictions have far-reaching effects on early pregnancy loss care and on resident education,” the researchers concluded.

“Abortion restrictions don’t just affect people seeking abortions; they affect people also suffering from early pregnancy loss,” Aurora Phillips, MD, an ob.gyn. resident at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview. “It’s harder to make that diagnosis and to be able to offer interventions, and these institutions that had restrictions also were less likely to have mifepristone or office based human aspiration, which are the most efficient and cost-effective interventions that we have.”

For example, less than half the programs surveyed offered mifepristone to help manage a miscarriage, “with availability varying inversely with abortion restrictions,” they found. After considering all characteristics of residency programs, “institutional abortion restrictions and bans were more important than state policies or religious affiliation in determining whether evidence-based early pregnancy loss treatments were available,” the researchers found, though their findings predated the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade. “Training institutions with a commitment to evidence-based family planning care and education are able to ensure access to the most evidence-based, cost-effective, and timely treatments for pregnancy loss even in the face of state abortion restrictions, thereby preserving patient safety, physician competency, and health care system sustainability,” they wrote.

Reduced access leads to higher risk interventions

An estimated 10%-20% of pregnancies result in early miscarriage, totaling more than one million cases in the U.S. each year. But since treatments for miscarriage often overlap with those for abortion, the researchers wondered whether differences existed in how providers managed miscarriages in states or institutions with strict abortion restrictions versus management in hospitals without restrictions.

They also looked at how closely the management strategies adhered to ACOG’s recommendations, which advise that providers consider both ultrasound imaging and other factors, including clinical reasoning and patient preferences, before diagnosing early pregnancy loss and considering possible interventions.

For imaging guidelines, ACOG endorses the criteria established for ultrasound diagnosis of first trimester pregnancy loss from the Society of Radiologists in 2012. But, the authors note, these guidelines are very conservative, exceeding previous measurements that had a 99%-100% predictive value for pregnancy loss, in the interest of “[prioritizing preservation of] fetal potential over facilitating expeditious care.” Hence the reason ACOG advises providers to include clinical judgment and patient preferences in their approach to care.

”In places where abortion is heavily regulated, clinicians managing miscarriages may cautiously rely on the strictest criteria to differentiate early pregnancy loss from potentially viable pregnancy and may not offer certain treatments commonly associated with abortion,” the authors noted. ACOG recommends surgical aspiration and medical treatment with both mifepristone and misoprostol as the safest and most effective options in managing miscarriages.

“Treating early pregnancy loss without the use of mifepristone is more likely to fail, is more likely to require an unscheduled procedure, and people who choose medication management for their miscarriages are usually trying to avoid a procedure, so that is the downside of not using mifepristone,” coauthor Rachel M. Flink-Bochacki, MD, an associate professor at Albany (N.Y.) Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Office-based uterine aspiration has the same safety profile as uterine aspiration in the operating room minus the risks of anesthesia and also helps patients get in faster because they don’t need to wait for OR time,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki explained. “So again, for a patient who wants an aspiration and does not want to pass the pregnancy at home, not having access to office-based aspiration could lead them to miscarry at home, which has higher risks and is not what they wanted.”

Reduced access to miscarriage care options in ‘hostile’ states

Among all 296 U.S. ob.gyn. residency programs that were contacted between November 2021 and January 2022, half (50.3%) responded to the researchers’ survey about their institutional practices around miscarriage, including location of diagnosis, use of ultrasound diagnostic guidelines, treatment options offered by their institution, and institutional restrictions on abortions based on indication.

The survey also collected characteristics of each program, including its state, setting, religious affiliation, and affiliation with the Ryan Training Program in Abortion and Family Planning. The responding sample had similar geographic distribution and state abortion policies as those who did not respond, but the responding programs were slightly more likely to be academic programs and to be affiliated with the Ryan program.

At the time of the study, prior to the Dobbs ruling, more than half the U.S. states had legislation restricting abortion care, and 57% of national teaching hospitals had internal restrictions that limited care based on gestational age and indication, particularly if the indication was elective, the authors reported. The researchers relied on designations from the Guttmacher Institute in December 2020 to categorize states as “hostile” to abortion (very hostile, hostile, and leans hostile) or non-hostile (neutral, leans supportive, supportive, and very supportive).

Most of the programs (80%) had no religious affiliation, but 11% had a Catholic affiliation and 5% had a different Christian affiliation. Institutional policies either had no restrictions on abortion care (38%), had restrictions (39%) based on certain maternal or fetal indications, or completely banned abortion services unless the mother’s life was threatened (23%). Among the Christian-affiliated programs, 60% had bans and 40% had restrictions.

Half (49.7%) of the responding programs relied rigidly on ultrasound criteria before offering any intervention for suspected early pregnancy loss, regardless of patient preferences. The other half (50.3%) incorporated ultrasound criteria and other factors, including clinical judgment and patient preferences, into a holistic determination of what options to present to the patient.

Before accounting for other factors, the researchers found that only a third (33%) of programs in states with severe abortion restrictions considered additional factors besides imaging when offering patients options for miscarriage management. In states without such abortion restrictions, 79% of programs considered both imaging and other factors (P < .001).

In states with “hostile abortion legislation,” only 32% of the programs used mifepristone for miscarriage management, compared with 75% of the programs in states without onerous abortion restrictions (P < .001). The results were similar for use of office-based suction aspiration: Just under half the programs (48%) in states with severe abortion restrictions included this technique as part of standard miscarriage management, compared with 68% of programs in states without such restrictions (P = .014).

Those findings match up with the experience of Cara Heuser, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist from Salt Lake City, who was not involved in this study.

“We had a lot of restrictions even before Roe fell,” including heavy regulation of mifepristone, Dr. Heuser said in an interview. “In non-restricted states, it’s pretty easy to get, but even before Roe in our state, it was very, very difficult to get institutions and individual doctor’s offices to carry mifepristone to treat miscarriages. They were still treating miscarriages in a way that was known to be less effective.” Adding mifepristone to misoprostol reduces the risk of needing an evacuation surgery procedure, she explained, “so adding the mifepristone makes it safer.”

Institutional policies had the strongest impact

Before accounting for the state a hospital was in, 27% of institutions with restrictive abortion policies looked at more than imaging in determining how to proceed, compared with 88% of institutions without abortion restrictions that included clinical judgment and patient preferences in their management.

After controlling for state policies and affiliation with a family planning training program or a religious entity, the odds of an institution relying solely on imaging guidelines were over 12 times greater for institutions with abortion restrictions or bans (odds ratio, 12.3; 95% confidence interval, 3.2-47.9). Specifically, the odds were 9 times greater for institutions with restrictions and 27 times greater for institutions with bans.

Only 12% of the institutions without restrictions relied solely on ultrasound criteria, compared with 67% of the institutions with restrictions and 82% of the institutions that banned all abortions except to save the life of the pregnant individual (P < .001).

Only one in four (25%) of the programs with institutional abortion restrictions used mifepristone, compared with 86% of unrestricted programs (P < .001), and 40% of programs with institutional abortion restrictions used office-based aspiration, compared with 81% of unrestricted programs (P < .001).

Without access to all evidence-based treatments, doctors are often forced to choose expectant management for miscarriages. “So you’re kind of forced to have them to pass the pregnancy at home, which can be traumatic for patients” if that’s not what they wanted, Dr. Phillips said.

Dr. Flink-Bochacki further noted that this patient population is already particularly vulnerable.

“Especially for patients with early pregnancy loss, it’s such a feeling of powerlessness already, so the mental state that many of these patients are in is already quite fraught,” Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “Then to not even have power to choose the interventions that you want or to be able to access interventions in a timely fashion because you’re being held to some arbitrary guideline further takes away the power and further exacerbates the trauma of the experience.”

The biggest factor likely driving the reduced access to those interventions is the fear that the care could be confused with providing an abortion instead of simply managing a miscarriage, Dr. Flink-Bochacki said. “I think that’s why a lot of these programs don’t have mifepristone and don’t offer outpatient uterine aspiration,” she said. “Because those are so widely used in abortion and the connotation is with abortion, they’re just kind of steering clear of it, but meanwhile, patients with pregnancy loss are suffering because they’re being unnecessarily restrictive.”

The research did not use any external funding, and the authors and Dr. Heuser had no disclosures.

AT ACOG 2023

First prospective study finds pregnancies with Sjögren’s to be largely safe

Women with Sjögren’s syndrome have pregnancy outcomes similar to those of the general population, according to the first study to prospectively track pregnancy outcomes among people with the autoimmune condition.

“Most early studies of pregnancy in rheumatic disease patients were retrospective and included only small numbers, making it difficult to know how generalizable the reported results were,” said Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a rheumatologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, in an email interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the research.

Most of these previous studies suggested an increased risk of adverse outcomes, such as miscarriages, preterm deliveries, and small-for-gestational-age birth weight. But in addition to small patient numbers, retrospective studies “are subject to greater reporting bias, which may predispose patients with negative outcomes being more likely to be included because they were followed more closely,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“This prospective study has several advantages over the earlier retrospective reports: The same data were collected in the same way for all the patients, the patients were recruited at similar time points, and – due to the multicenter nature of the cohort – numbers are larger than in prior studies. All these factors make the results stronger and more generalizable to the Sjögren’s patients we see in our practices,” she added.

In the study, published May 8 in The Lancet Rheumatology, first author Grégoire Martin de Frémont, MD, of the rheumatology service at Bicêtre Hospital, Paris-Saclay University and colleagues used the GR2 registry, an observational database of pregnancies of women with systemic autoimmune diseases managed at 76 participating centers in France, to identify pregnant women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. To avoid bias, only women who entered the database before 18 weeks’ gestation were included. The final cohort included 106 pregnancies in 96 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and 420 control pregnancies that were matched from the general population.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery (< 37 weeks of gestation), intrauterine growth retardation, and low birth weight occurred in nine pregnancies (9%) in the Sjögren’s syndrome group and in 28 pregnancies in the control group (7%). Adverse pregnancy outcomes were not significantly associated with Sjögren’s syndrome (P = .52). Researchers found that there were more adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with Sjögren’s syndrome with antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies. Negative outcomes also increased among those with anti-RNP antibodies, but this association was not statistically significant.

“The main message – based on strong data from a well-designed study – is that patients with Sjögren’s overall do as well as the general population in terms of standard adverse pregnancy outcomes. The rate of flare of Sjögren’s disease was relatively low during the second and third trimesters, also reassuring,” Dr. Sammaritano said. She noted that the association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and aPL antibodies was not unexpected, given that they are a known risk factor.

The study authors recommend that patients with Sjögren’s syndrome be screened for aPL and anti-RNP antibodies prior to conception because of the potential increased risk for complications and that patients with positive screens be closely monitored during their pregnancy.

Dr. Sammaritano noted that there are other health problems to keep in mind. “It is important to remember that Sjögren’s patients – more than any other rheumatic disease patients – have the additional risk for neonatal lupus and complete heart block in their infant, since about two-thirds of Sjögren’s patients are positive for anti-Ro/SSA antibody,” she said. “This is a distinct issue related to the presence of this antibody alone and not specifically related to the underlying diagnosis. In clinical practice, positive anti-Ro/SSA antibody is often the main reason for counseling, monitoring, and even recommending therapy (hydroxychloroquine) in these patients.”

The study received funding from Lupus France, the France Association of Scleroderma, and the Association Gougerot Sjögren, among others. Dr. Sammaritano reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with Sjögren’s syndrome have pregnancy outcomes similar to those of the general population, according to the first study to prospectively track pregnancy outcomes among people with the autoimmune condition.

“Most early studies of pregnancy in rheumatic disease patients were retrospective and included only small numbers, making it difficult to know how generalizable the reported results were,” said Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a rheumatologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, in an email interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the research.

Most of these previous studies suggested an increased risk of adverse outcomes, such as miscarriages, preterm deliveries, and small-for-gestational-age birth weight. But in addition to small patient numbers, retrospective studies “are subject to greater reporting bias, which may predispose patients with negative outcomes being more likely to be included because they were followed more closely,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“This prospective study has several advantages over the earlier retrospective reports: The same data were collected in the same way for all the patients, the patients were recruited at similar time points, and – due to the multicenter nature of the cohort – numbers are larger than in prior studies. All these factors make the results stronger and more generalizable to the Sjögren’s patients we see in our practices,” she added.

In the study, published May 8 in The Lancet Rheumatology, first author Grégoire Martin de Frémont, MD, of the rheumatology service at Bicêtre Hospital, Paris-Saclay University and colleagues used the GR2 registry, an observational database of pregnancies of women with systemic autoimmune diseases managed at 76 participating centers in France, to identify pregnant women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. To avoid bias, only women who entered the database before 18 weeks’ gestation were included. The final cohort included 106 pregnancies in 96 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and 420 control pregnancies that were matched from the general population.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery (< 37 weeks of gestation), intrauterine growth retardation, and low birth weight occurred in nine pregnancies (9%) in the Sjögren’s syndrome group and in 28 pregnancies in the control group (7%). Adverse pregnancy outcomes were not significantly associated with Sjögren’s syndrome (P = .52). Researchers found that there were more adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with Sjögren’s syndrome with antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies. Negative outcomes also increased among those with anti-RNP antibodies, but this association was not statistically significant.

“The main message – based on strong data from a well-designed study – is that patients with Sjögren’s overall do as well as the general population in terms of standard adverse pregnancy outcomes. The rate of flare of Sjögren’s disease was relatively low during the second and third trimesters, also reassuring,” Dr. Sammaritano said. She noted that the association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and aPL antibodies was not unexpected, given that they are a known risk factor.

The study authors recommend that patients with Sjögren’s syndrome be screened for aPL and anti-RNP antibodies prior to conception because of the potential increased risk for complications and that patients with positive screens be closely monitored during their pregnancy.

Dr. Sammaritano noted that there are other health problems to keep in mind. “It is important to remember that Sjögren’s patients – more than any other rheumatic disease patients – have the additional risk for neonatal lupus and complete heart block in their infant, since about two-thirds of Sjögren’s patients are positive for anti-Ro/SSA antibody,” she said. “This is a distinct issue related to the presence of this antibody alone and not specifically related to the underlying diagnosis. In clinical practice, positive anti-Ro/SSA antibody is often the main reason for counseling, monitoring, and even recommending therapy (hydroxychloroquine) in these patients.”

The study received funding from Lupus France, the France Association of Scleroderma, and the Association Gougerot Sjögren, among others. Dr. Sammaritano reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with Sjögren’s syndrome have pregnancy outcomes similar to those of the general population, according to the first study to prospectively track pregnancy outcomes among people with the autoimmune condition.

“Most early studies of pregnancy in rheumatic disease patients were retrospective and included only small numbers, making it difficult to know how generalizable the reported results were,” said Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a rheumatologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, in an email interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the research.

Most of these previous studies suggested an increased risk of adverse outcomes, such as miscarriages, preterm deliveries, and small-for-gestational-age birth weight. But in addition to small patient numbers, retrospective studies “are subject to greater reporting bias, which may predispose patients with negative outcomes being more likely to be included because they were followed more closely,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“This prospective study has several advantages over the earlier retrospective reports: The same data were collected in the same way for all the patients, the patients were recruited at similar time points, and – due to the multicenter nature of the cohort – numbers are larger than in prior studies. All these factors make the results stronger and more generalizable to the Sjögren’s patients we see in our practices,” she added.

In the study, published May 8 in The Lancet Rheumatology, first author Grégoire Martin de Frémont, MD, of the rheumatology service at Bicêtre Hospital, Paris-Saclay University and colleagues used the GR2 registry, an observational database of pregnancies of women with systemic autoimmune diseases managed at 76 participating centers in France, to identify pregnant women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. To avoid bias, only women who entered the database before 18 weeks’ gestation were included. The final cohort included 106 pregnancies in 96 women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and 420 control pregnancies that were matched from the general population.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery (< 37 weeks of gestation), intrauterine growth retardation, and low birth weight occurred in nine pregnancies (9%) in the Sjögren’s syndrome group and in 28 pregnancies in the control group (7%). Adverse pregnancy outcomes were not significantly associated with Sjögren’s syndrome (P = .52). Researchers found that there were more adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with Sjögren’s syndrome with antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies. Negative outcomes also increased among those with anti-RNP antibodies, but this association was not statistically significant.

“The main message – based on strong data from a well-designed study – is that patients with Sjögren’s overall do as well as the general population in terms of standard adverse pregnancy outcomes. The rate of flare of Sjögren’s disease was relatively low during the second and third trimesters, also reassuring,” Dr. Sammaritano said. She noted that the association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and aPL antibodies was not unexpected, given that they are a known risk factor.

The study authors recommend that patients with Sjögren’s syndrome be screened for aPL and anti-RNP antibodies prior to conception because of the potential increased risk for complications and that patients with positive screens be closely monitored during their pregnancy.

Dr. Sammaritano noted that there are other health problems to keep in mind. “It is important to remember that Sjögren’s patients – more than any other rheumatic disease patients – have the additional risk for neonatal lupus and complete heart block in their infant, since about two-thirds of Sjögren’s patients are positive for anti-Ro/SSA antibody,” she said. “This is a distinct issue related to the presence of this antibody alone and not specifically related to the underlying diagnosis. In clinical practice, positive anti-Ro/SSA antibody is often the main reason for counseling, monitoring, and even recommending therapy (hydroxychloroquine) in these patients.”

The study received funding from Lupus France, the France Association of Scleroderma, and the Association Gougerot Sjögren, among others. Dr. Sammaritano reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

2023 Update on genetics in fetal growth

Whole exome sequencing’s role in diagnosing genetic causes of FGR with and without associated anomalies

Mone F, Mellis R, Gabriel H, et al. Should we offer prenatal exome sequencing for intrauterine growth restriction or short long bones? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online October 7, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.09.045

Multiple factors can play a role in FGR, including inherent maternal, placental, or fetal factors; the environment; and/or nutrition. However, prenatal diagnosis is an important consideration when exploring the underlying etiology for a growth-restricted fetus, especially in severe or early-onset cases. Many genetic conditions do not result in structural anomalies but can disrupt overall growth. Additionally, phenotyping in the prenatal period is limited and can miss more subtle physical differences that could point to a genetic cause.

When compared with karyotype, chromosomal microarray (CMA) has been shown to increase the diagnostic yield in cases of isolated early FGR by 5%,1,2 and the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities has been reported to be as high as 19% in this population. Let’s explore the data on exome sequencing for prenatal diagnosis in cases of isolated FGR.

Meta-analysis details

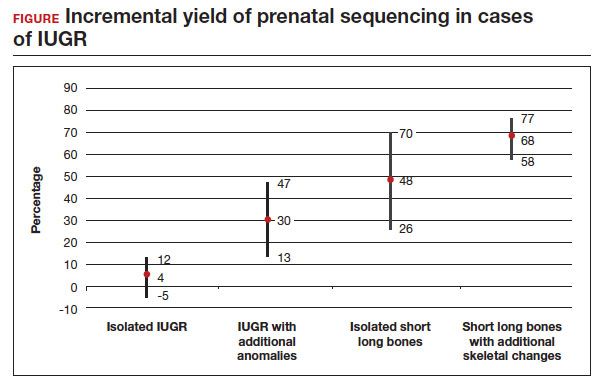

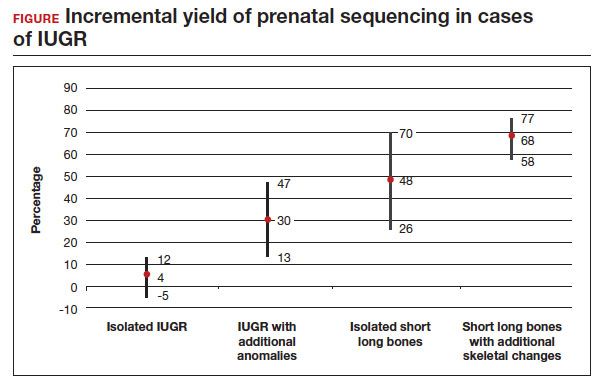

In this meta-analysis, the authors reviewed 19 cohort studies or case series that investigated the yield of prenatal sequencing in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or short long bones, both in association with and without additional anomalies. All cases had nondiagnostic cytogenetic results. Fetal DNA in most cases was obtained through amniocentesis. Variants classified as likely pathogenic and pathogenic were considered diagnostic. The authors then calculated the incremental yield of prenatal sequencing over cytogenetic studies as a pooled value, comparing the following groups:

- isolated FGR

- growth restriction with associated anomalies

- isolated short long bones

- short long bones with additional skeletal features.

Study outcomes

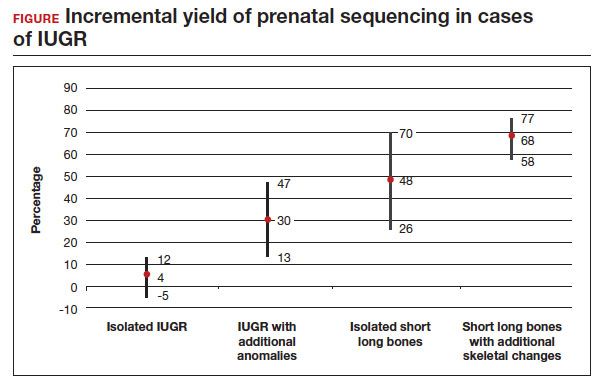

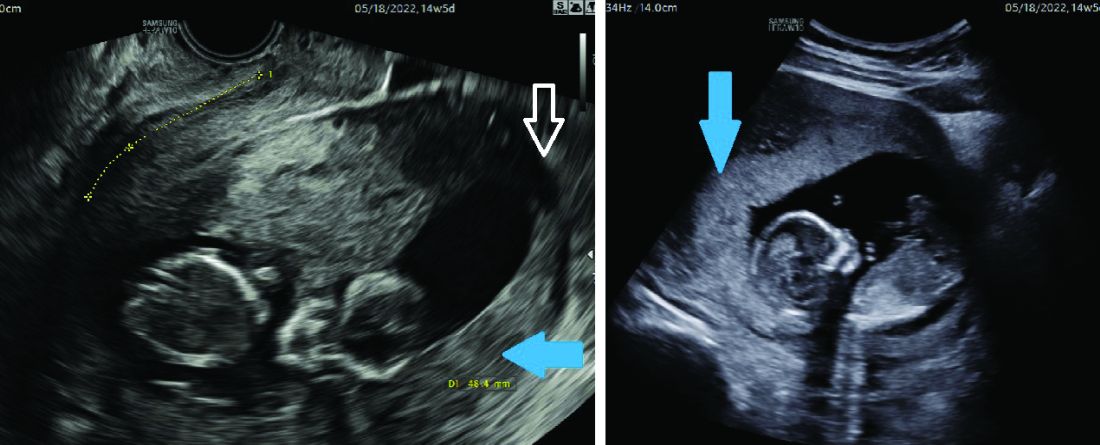

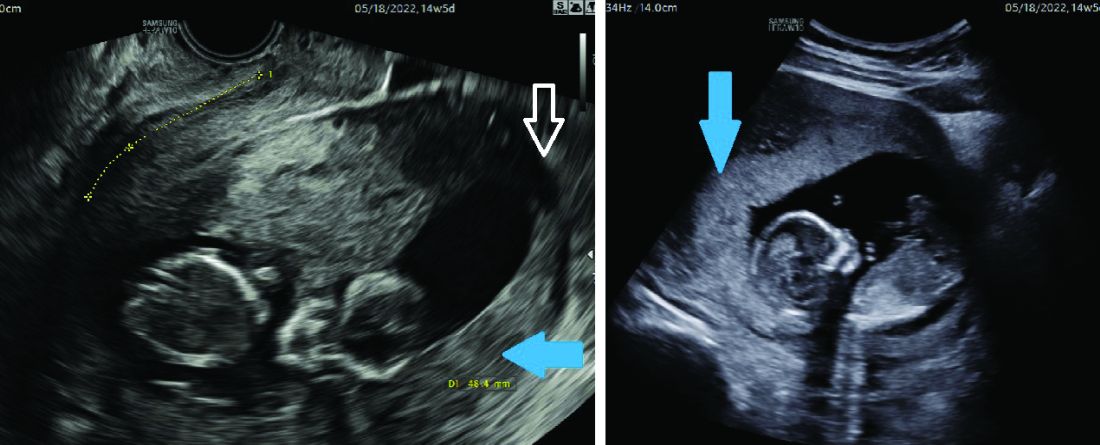

The total number of cases were as follows: isolated IUGR (n = 71), IUGR associated with additional anomalies (n = 45), isolated short long bones (n = 84), and short long bones associated with additional skeletal findings (n = 252). Causative pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 224 (50%) cases. Apparent incremental yields with prenatal sequencing were as follows for the 4 groups (as illustrated in the FIGURE):

- 4% in isolated IUGR (95% confidence interval [CI], -5%–12%)

- 30% in IUGR with additional anomalies (95% CI, 13%–47%)

- 48% in isolated short long bones (95% CI, 26%–70%)

- 68% in short long bones with additional skeletal changes (95% CI, 58%–77%).

Overall, the authors concluded that prenatal sequencing does not improve prenatal diagnosis in cases of isolated IUGR. The majority of these cases were thought to be related to placental insufficiency.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation of this study with regard to our discussion is the small study populationof isolated growth restriction. The authors indicate that the number of cases of isolated IUGR were too small to draw firm conclusions. Another limitation was the heterogeneity of the isolated FGR population, which was not limited to severe or early-onset cases. However, the authors did demonstrate that growth restriction in association with fetal anomalies has very high genetic yield rates with prenatal sequencing.

Not surprisingly, there is a high yield of diagnosing genetic conditions in pregnancies complicated by isolated or nonisolated short long bones or in cases of growth restriction with multisystem abnormalities. Based on the results of this study, the authors advise against sending for exome sequencing in cases of isolated growth restriction with coexisting evidence of placental insufficiency.

Continue to: Can whole exome sequencing diagnose genetic causes in cases of severe isolated FGR?...

Can whole exome sequencing diagnose genetic causes in cases of severe isolated FGR?

Zhou H, Fu F, Wang Y, et al. Genetic causes of isolated and severe fetal growth restriction in normal chromosomal microarray analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. Published online December 10, 2022. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14620

Severe FGR is diagnosed based on an estimated fetal weight (EFW) or abdominal circumference (AC) below the third percentile. As we discussed in the above study by Mone and colleagues, it does not appear that prenatal sequencing significantly improves the diagnostic yield in all isolated FGR cases. However, this has not been previously explored in isolated severe FGR or cases of early-onset FGR (<32 weeks’ gestation). We know that several monogenic conditions are associated with severe and early-onset isolated fetal growth impairment, including but not limited to Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, and Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Often, these syndromes can present in the prenatal period without other phenotypic findings. Therefore, this study explored the possibility that prenatal sequencing plays an important role for severe cases of FGR with nondiagnostic CMA and/or karyotype.

Retrospective study details

Zhou and colleagues retrospectively analyzed 51 cases of severe (EFW or AC below the third percentile) isolated FGR with negative CMA who underwent trio whole exome sequencing, which includes submitting fetal cells as well as both parental samples for testing. Patients with abnormal toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus (TORCH) tests; structural anomalies; and multiple gestation were excluded from the analysis. As in the study by Mone et al, variants classified as likely pathogenic and pathogenic were categorized as diagnostic.

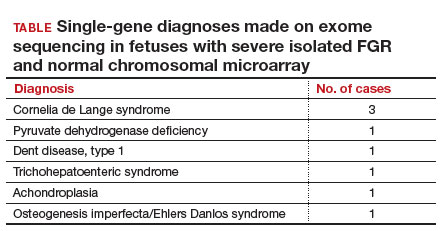

Results

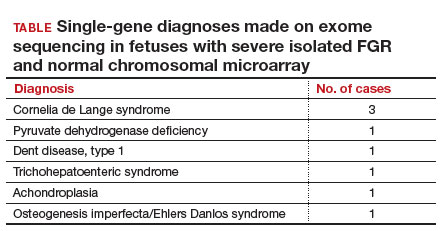

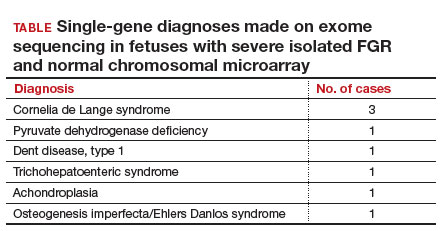

Eight of 51 cases (15.7%) with severe isolated FGR had diagnostic findings on trio whole exome sequencing as shown in the TABLE. Another 8 cases (15.7%) were found to have variants of unknown significance, of which 2 were later determined to be novel pathogenic variants. Genetic conditions uncovered in this cohort include Cornelia de Lange syndrome, pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency, Dent disease, trichohepaticenteric syndrome, achondroplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, Pendred syndrome, and both autosomal dominant type 3A and autosomal recessive type 1A deafness. All 10 cases with diagnostic whole exome sequencing or identified novel pathogenic variants were affected by early-onset FGR (<32 weeks’ gestation). Of these 10 cases, 7 patients underwent pregnancy termination.

To summarize, a total of 10 cases (19.6%) of severe isolated early-onset FGR with negative cytogenetic studies were subsequently diagnosed with an underlying genetic condition using prenatal trio whole exome sequencing.

Strengths and limitations

This study is retrospective and has a small sample size (n = 51) that was mostly limited to early-onset isolated severe FGR. However, the diagnostic yield (19.6%) of whole exome sequencing after negative CMA testing was noteworthy and shows that monogenic conditions are an important consideration in the evaluation of severe early-onset FGR, even in the absence of structural abnormalities.

As indications for exome sequencing during pregnancy continue to evolve, severe isolated FGR is emerging as a high-yield condition in which a subset of patients may benefit from the described testing strategy. We learned from our look at the prior study (Mone et al) that unselected isolated growth restriction with evident placental insufficiency may not benefit from exome sequencing, but this study differs in its selection of early-onset, severe cases—defined by diagnosis before 32 weeks’ gestation and an EFW or AC below the third percentile. Almost 20% of cases who met the aforementioned criteria received a genetic diagnosis from exome sequencing. We should remember to offer genetic counseling and diagnostic testing to our patients with severe growth restriction, even in the absence of additional structural anomalies.

Could epigenetic mechanisms of placental dysregulation explain low birthweight and future cardiometabolic disease?

Tekola-Ayele F, Zeng X, Chatterjee S, et al. Placental multi-omics integration identifies candidate functional genes for birthweight. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2384.

FGR has been linked to greater mortality in childhood and increased risk for cardiometabolic disease in adulthood. While genomewide associations studies (GWAS) have defined areas of interest linking genetic variants to low birthweight, their relationship to epigenetic changes in the placenta as well as biologic and functional mechanisms are not yet well understood.

Multiomics used to identify candidate functional genes for birthweight

This study analyzed the methylation and gene expression patterns of 291 placental samples, integrating findings into pathways of previously defined GWAS variants. Patient samples were obtained from participants in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies–Singleton cohort. The cohort is ethnically diverse, with 97 Hispanic, 74 White, 71 Black, and 49 Asian participants. Of 286 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) found to be associated with birthweight, 273 were analyzed as part of the authors’ data set. These were found to have 7,901 unique protein-coding mRNAs (expression quantitative trait loci [eQTL]) and more than 100,000 nearby (within 1 Mb) CpG islands thought to be involved in changes in DNA methylation (methylation quantitative trait loci [mQTL]). Each functionally connected GWAS-eQTL-mQTL association is referred to as a triplet.

The next arm of the study investigatedthe connections and pathways within each triplet. Three possible scenarios were explored for birthweight GWAS SNPs using a causal interference test (CIT):

- the SNP alters placental DNA methylation, which then influences gene expression

- the SNP first alters placental DNA expression, which then influences methylation

- the SNP influences placental DNA expression and methylation independently, with no notable crossover between their pathways.

Triplets were investigated using the Mendelian randomization (MR) Steiger directionality test to validate the directionality of the pathways found by CIT. Lastly, the possibility of linkage disequilibrium was also studied using the moloc test.

Results

Using CIT, a causal relationship was predicted in 88 of 197 triplets, in which 84 (95.5%) indicated DNA methylation influences gene expression, and 4 (4.5%) indicated gene expression influences DNA methylation. The authors also used the MR Steiger test to investigate triplets to identify possible causal pathways. Using the MR Steiger test, only 3 of 45 (7%) triplets were found to have independent gene expression and methylation pathways. Thirty-eight of 45 (84%) triplets indicated that gene expression influences DNA methylation, and 7 (15%)triplets demonstrated that DNA methylation influences gene expression. Consistent predictions between CIT and the MR Steiger test revealed 3 triplets in which DNA methylation influences gene expression for the following genes: WNT3A, CTDNEP1, and RANBP2. Additionally, a strong colocalization signal was found among birthweight, DNA methylation, and gene expression for the following genes: PLEKHA1, FES, PRMT7, and CTDNEP1. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed as well and found that low birthweight is associated in substantial upregulation of genes associated with oxidative stress, immune response, adipogenesis, myogenesis, and the production of pancreatic ß cells.

Study strengths and limitations

The study is one of the first to identify regulatory targets for placental DNA methylation and gene expression in previously identified GWAS loci associated with low birthweight. For example, DNA methylation was found to influence gene expression of WNT3A, CTDNEP1, and RANBP2, which have previously been shown in animal studies to impact the vascularization and development of the placenta, embryogenesis, and fetal growth. The study also identified 4 genes (PLEKHA1, FES, PRMT7, and CTDNEP1) thought to have direct regulatory influence on placental DNA methylation and gene expression.

A limitation of the study is that it could not distinguish between whether the epigenetic changes we outlined have a maternal or fetal origin. Another limitation is that tissue used by the authors for analysis was a small placental biopsy, which does not accurately reflect the genetic heterogeneity of the placenta. Finally, this study does not establish causality between the identified epigenetic pathways and low birthweight. ●

We know that the placenta is critical to in utero development. This study begins to explore the genetic changes and programming in the placenta that may have profound effects on health and well-being both early and later in life.

- Li LS, Li DZ. A genetic approach to the etiologic investigation of isolated intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:695-696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021 .07.021.

- Borrell A, Grande M, Pauta M, et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis in fetuses with growth restriction and normal karyotype: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2018;44:1-9. doi: 10.1159/000479506.

Whole exome sequencing’s role in diagnosing genetic causes of FGR with and without associated anomalies

Mone F, Mellis R, Gabriel H, et al. Should we offer prenatal exome sequencing for intrauterine growth restriction or short long bones? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online October 7, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.09.045

Multiple factors can play a role in FGR, including inherent maternal, placental, or fetal factors; the environment; and/or nutrition. However, prenatal diagnosis is an important consideration when exploring the underlying etiology for a growth-restricted fetus, especially in severe or early-onset cases. Many genetic conditions do not result in structural anomalies but can disrupt overall growth. Additionally, phenotyping in the prenatal period is limited and can miss more subtle physical differences that could point to a genetic cause.

When compared with karyotype, chromosomal microarray (CMA) has been shown to increase the diagnostic yield in cases of isolated early FGR by 5%,1,2 and the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities has been reported to be as high as 19% in this population. Let’s explore the data on exome sequencing for prenatal diagnosis in cases of isolated FGR.

Meta-analysis details

In this meta-analysis, the authors reviewed 19 cohort studies or case series that investigated the yield of prenatal sequencing in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) or short long bones, both in association with and without additional anomalies. All cases had nondiagnostic cytogenetic results. Fetal DNA in most cases was obtained through amniocentesis. Variants classified as likely pathogenic and pathogenic were considered diagnostic. The authors then calculated the incremental yield of prenatal sequencing over cytogenetic studies as a pooled value, comparing the following groups:

- isolated FGR

- growth restriction with associated anomalies

- isolated short long bones

- short long bones with additional skeletal features.

Study outcomes

The total number of cases were as follows: isolated IUGR (n = 71), IUGR associated with additional anomalies (n = 45), isolated short long bones (n = 84), and short long bones associated with additional skeletal findings (n = 252). Causative pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 224 (50%) cases. Apparent incremental yields with prenatal sequencing were as follows for the 4 groups (as illustrated in the FIGURE):

- 4% in isolated IUGR (95% confidence interval [CI], -5%–12%)

- 30% in IUGR with additional anomalies (95% CI, 13%–47%)

- 48% in isolated short long bones (95% CI, 26%–70%)

- 68% in short long bones with additional skeletal changes (95% CI, 58%–77%).

Overall, the authors concluded that prenatal sequencing does not improve prenatal diagnosis in cases of isolated IUGR. The majority of these cases were thought to be related to placental insufficiency.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation of this study with regard to our discussion is the small study populationof isolated growth restriction. The authors indicate that the number of cases of isolated IUGR were too small to draw firm conclusions. Another limitation was the heterogeneity of the isolated FGR population, which was not limited to severe or early-onset cases. However, the authors did demonstrate that growth restriction in association with fetal anomalies has very high genetic yield rates with prenatal sequencing.

Not surprisingly, there is a high yield of diagnosing genetic conditions in pregnancies complicated by isolated or nonisolated short long bones or in cases of growth restriction with multisystem abnormalities. Based on the results of this study, the authors advise against sending for exome sequencing in cases of isolated growth restriction with coexisting evidence of placental insufficiency.

Continue to: Can whole exome sequencing diagnose genetic causes in cases of severe isolated FGR?...

Can whole exome sequencing diagnose genetic causes in cases of severe isolated FGR?

Zhou H, Fu F, Wang Y, et al. Genetic causes of isolated and severe fetal growth restriction in normal chromosomal microarray analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. Published online December 10, 2022. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14620

Severe FGR is diagnosed based on an estimated fetal weight (EFW) or abdominal circumference (AC) below the third percentile. As we discussed in the above study by Mone and colleagues, it does not appear that prenatal sequencing significantly improves the diagnostic yield in all isolated FGR cases. However, this has not been previously explored in isolated severe FGR or cases of early-onset FGR (<32 weeks’ gestation). We know that several monogenic conditions are associated with severe and early-onset isolated fetal growth impairment, including but not limited to Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, and Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Often, these syndromes can present in the prenatal period without other phenotypic findings. Therefore, this study explored the possibility that prenatal sequencing plays an important role for severe cases of FGR with nondiagnostic CMA and/or karyotype.

Retrospective study details

Zhou and colleagues retrospectively analyzed 51 cases of severe (EFW or AC below the third percentile) isolated FGR with negative CMA who underwent trio whole exome sequencing, which includes submitting fetal cells as well as both parental samples for testing. Patients with abnormal toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus (TORCH) tests; structural anomalies; and multiple gestation were excluded from the analysis. As in the study by Mone et al, variants classified as likely pathogenic and pathogenic were categorized as diagnostic.

Results

Eight of 51 cases (15.7%) with severe isolated FGR had diagnostic findings on trio whole exome sequencing as shown in the TABLE. Another 8 cases (15.7%) were found to have variants of unknown significance, of which 2 were later determined to be novel pathogenic variants. Genetic conditions uncovered in this cohort include Cornelia de Lange syndrome, pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency, Dent disease, trichohepaticenteric syndrome, achondroplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, Pendred syndrome, and both autosomal dominant type 3A and autosomal recessive type 1A deafness. All 10 cases with diagnostic whole exome sequencing or identified novel pathogenic variants were affected by early-onset FGR (<32 weeks’ gestation). Of these 10 cases, 7 patients underwent pregnancy termination.

To summarize, a total of 10 cases (19.6%) of severe isolated early-onset FGR with negative cytogenetic studies were subsequently diagnosed with an underlying genetic condition using prenatal trio whole exome sequencing.

Strengths and limitations

This study is retrospective and has a small sample size (n = 51) that was mostly limited to early-onset isolated severe FGR. However, the diagnostic yield (19.6%) of whole exome sequencing after negative CMA testing was noteworthy and shows that monogenic conditions are an important consideration in the evaluation of severe early-onset FGR, even in the absence of structural abnormalities.

As indications for exome sequencing during pregnancy continue to evolve, severe isolated FGR is emerging as a high-yield condition in which a subset of patients may benefit from the described testing strategy. We learned from our look at the prior study (Mone et al) that unselected isolated growth restriction with evident placental insufficiency may not benefit from exome sequencing, but this study differs in its selection of early-onset, severe cases—defined by diagnosis before 32 weeks’ gestation and an EFW or AC below the third percentile. Almost 20% of cases who met the aforementioned criteria received a genetic diagnosis from exome sequencing. We should remember to offer genetic counseling and diagnostic testing to our patients with severe growth restriction, even in the absence of additional structural anomalies.

Could epigenetic mechanisms of placental dysregulation explain low birthweight and future cardiometabolic disease?

Tekola-Ayele F, Zeng X, Chatterjee S, et al. Placental multi-omics integration identifies candidate functional genes for birthweight. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2384.

FGR has been linked to greater mortality in childhood and increased risk for cardiometabolic disease in adulthood. While genomewide associations studies (GWAS) have defined areas of interest linking genetic variants to low birthweight, their relationship to epigenetic changes in the placenta as well as biologic and functional mechanisms are not yet well understood.

Multiomics used to identify candidate functional genes for birthweight

This study analyzed the methylation and gene expression patterns of 291 placental samples, integrating findings into pathways of previously defined GWAS variants. Patient samples were obtained from participants in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies–Singleton cohort. The cohort is ethnically diverse, with 97 Hispanic, 74 White, 71 Black, and 49 Asian participants. Of 286 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) found to be associated with birthweight, 273 were analyzed as part of the authors’ data set. These were found to have 7,901 unique protein-coding mRNAs (expression quantitative trait loci [eQTL]) and more than 100,000 nearby (within 1 Mb) CpG islands thought to be involved in changes in DNA methylation (methylation quantitative trait loci [mQTL]). Each functionally connected GWAS-eQTL-mQTL association is referred to as a triplet.

The next arm of the study investigatedthe connections and pathways within each triplet. Three possible scenarios were explored for birthweight GWAS SNPs using a causal interference test (CIT):

- the SNP alters placental DNA methylation, which then influences gene expression

- the SNP first alters placental DNA expression, which then influences methylation

- the SNP influences placental DNA expression and methylation independently, with no notable crossover between their pathways.

Triplets were investigated using the Mendelian randomization (MR) Steiger directionality test to validate the directionality of the pathways found by CIT. Lastly, the possibility of linkage disequilibrium was also studied using the moloc test.

Results

Using CIT, a causal relationship was predicted in 88 of 197 triplets, in which 84 (95.5%) indicated DNA methylation influences gene expression, and 4 (4.5%) indicated gene expression influences DNA methylation. The authors also used the MR Steiger test to investigate triplets to identify possible causal pathways. Using the MR Steiger test, only 3 of 45 (7%) triplets were found to have independent gene expression and methylation pathways. Thirty-eight of 45 (84%) triplets indicated that gene expression influences DNA methylation, and 7 (15%)triplets demonstrated that DNA methylation influences gene expression. Consistent predictions between CIT and the MR Steiger test revealed 3 triplets in which DNA methylation influences gene expression for the following genes: WNT3A, CTDNEP1, and RANBP2. Additionally, a strong colocalization signal was found among birthweight, DNA methylation, and gene expression for the following genes: PLEKHA1, FES, PRMT7, and CTDNEP1. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed as well and found that low birthweight is associated in substantial upregulation of genes associated with oxidative stress, immune response, adipogenesis, myogenesis, and the production of pancreatic ß cells.

Study strengths and limitations

The study is one of the first to identify regulatory targets for placental DNA methylation and gene expression in previously identified GWAS loci associated with low birthweight. For example, DNA methylation was found to influence gene expression of WNT3A, CTDNEP1, and RANBP2, which have previously been shown in animal studies to impact the vascularization and development of the placenta, embryogenesis, and fetal growth. The study also identified 4 genes (PLEKHA1, FES, PRMT7, and CTDNEP1) thought to have direct regulatory influence on placental DNA methylation and gene expression.

A limitation of the study is that it could not distinguish between whether the epigenetic changes we outlined have a maternal or fetal origin. Another limitation is that tissue used by the authors for analysis was a small placental biopsy, which does not accurately reflect the genetic heterogeneity of the placenta. Finally, this study does not establish causality between the identified epigenetic pathways and low birthweight. ●

We know that the placenta is critical to in utero development. This study begins to explore the genetic changes and programming in the placenta that may have profound effects on health and well-being both early and later in life.

Whole exome sequencing’s role in diagnosing genetic causes of FGR with and without associated anomalies

Mone F, Mellis R, Gabriel H, et al. Should we offer prenatal exome sequencing for intrauterine growth restriction or short long bones? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online October 7, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.09.045