User login

What is the significance of the head-to-body delivery interval in shoulder dystocia?

- Does the use of multiple maneuvers in the management of shoulder dystocia increase the risk of neonatal injury?

Robert B. Gherman, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2011)

Shoulder dystocia is a well-described obstetric complication that occurs in approximately 1% of deliveries.1 It has been associated with adverse maternal outcomes as well as adverse perinatal outcomes, including fracture, nerve palsy, and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy.

Although multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia have been described, experts have not yet been able to combine them into an accurate, discriminating, clinically useful shoulder dystocia prediction model; therefore, shoulder dystocia remains an unpredictable event.2 We also lack a strategy to prevent shoulder dystocia. Because we cannot predict or prevent it, a provider’s response to shoulder dystocia, once it occurs, is seminal, in terms of management.

Details of the study

As Lerner and colleagues concisely state, when shoulder dystocia occurs, there is a need for caution in the application of force during maneuvers and a “countervailing need to achieve delivery.” It is in a provider’s interest, then, to have knowledge of whether there is a time at which that countervailing need to achieve delivery takes on greater relative significance.

In an effort to address this issue, the authors examined the relationship between the duration of shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression (defined as the need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation; a pH level below 7.0; an Apgar score below 6 at 5 minutes; or death).

In their study, 127 births involving uncomplicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., no evidence of neonatal trauma or depression) from a single institution were compared with 55 births involving complicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., the occurrence of brachial plexus palsy with or without neonatal depression).

Lerner and colleagues found a correlation between the duration of shoulder dystocia and the extent of neonatal complications. For example, the median interval from head-to-body delivery for uncomplicated births was 1.0 minute; for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy alone, it was 2.0 minutes; and for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy and neonatal depression, the interval was 5.3 minutes (P <.001). There was no single cutoff, however, that was completely discriminating with regard to whether neonatal depression would occur.

Strengths and weaknesses of the trial

As the authors note, one limitation of their study is a lack of precision in the recorded duration of shoulder dystocia cases, given that “it appears that clinicians often rounded” the stated times.

Other types of bias that may have affected the findings include:

- Selection bias. In an observational study such as this, it is typically ideal to draw the cases and controls from the same underlying population in an effort to limit the occurrence of other potentially confounding factors, both known and unknown. In this study, however, the uncomplicated cases came from one institution over 10 years, whereas the complicated cases came from a medicolegal database one author had accumulated over 15 years. Because these clearly are very different populations, the reported association between head-to-body delivery interval and brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression may be related to characteristics other than, or in addition to, duration of the dystocia. For example, there may have been complicated cases that did not result in legal action. If the duration of the dystocia is in any way related to the chance that medicolegal action occurs, the relationship between duration and the presence of complication will be affected.

- Ascertainment bias. Because this study lacked a standard approach to the recording of duration, ascertainment bias may have affected the results. It is possible, for example, that the knowledge that a complication did or did not occur could have affected whether the duration was recorded or how much time was documented.

Complications of shoulder dystocia are rare

Ultimately, the primary question posed in this article is difficult to answer. Although shoulder dystocia occurs in approximately 1% of births, major adverse perinatal outcomes occur in only a fraction of these cases. That fact means that an event such as permanent brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression, let alone actual hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, occurs only in the context of thousands of births.

The data published to date,3,4 including this study, should offer some reassurance to obstetric care providers. Long-term adverse outcomes are uncommon in shoulder dystocia. Even intermediate outcomes such as neonatal depression, when they do occur, appear to be uncommon when the shoulder dystocia is of relatively short duration.

When shoulder dystocia does occur, however, providers should maintain situational awareness, being cognizant of the time that elapses, so that the continuation of appropriate and coordinated maneuvers can be ensured.

WILLIAM A. GROBMAN, MD, MBA

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: an evidence-based evaluation of the obstetric nightmare. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45(2):345-362.

2. Grobman WA, Stamilio DM. Methods of clinical prediction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):888-894.

3. Allen RH, Rosenbaum TC, Ghidini A, Poggi SH, Spong CY. Correlating head-to-body delivery intervals with neonatal depression in vaginal births that result in permanent brachial plexus injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):839-842.

4. Leung TY, Stuart O, Sahota DS, Suen SS, Lau TK, Lao TT. Head-to-body interval and risk of fetal acidosis and hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in shoulder dystocia: a retrospective review. BJOG. 2011;118(4):474-479.

- Does the use of multiple maneuvers in the management of shoulder dystocia increase the risk of neonatal injury?

Robert B. Gherman, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2011)

Shoulder dystocia is a well-described obstetric complication that occurs in approximately 1% of deliveries.1 It has been associated with adverse maternal outcomes as well as adverse perinatal outcomes, including fracture, nerve palsy, and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy.

Although multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia have been described, experts have not yet been able to combine them into an accurate, discriminating, clinically useful shoulder dystocia prediction model; therefore, shoulder dystocia remains an unpredictable event.2 We also lack a strategy to prevent shoulder dystocia. Because we cannot predict or prevent it, a provider’s response to shoulder dystocia, once it occurs, is seminal, in terms of management.

Details of the study

As Lerner and colleagues concisely state, when shoulder dystocia occurs, there is a need for caution in the application of force during maneuvers and a “countervailing need to achieve delivery.” It is in a provider’s interest, then, to have knowledge of whether there is a time at which that countervailing need to achieve delivery takes on greater relative significance.

In an effort to address this issue, the authors examined the relationship between the duration of shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression (defined as the need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation; a pH level below 7.0; an Apgar score below 6 at 5 minutes; or death).

In their study, 127 births involving uncomplicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., no evidence of neonatal trauma or depression) from a single institution were compared with 55 births involving complicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., the occurrence of brachial plexus palsy with or without neonatal depression).

Lerner and colleagues found a correlation between the duration of shoulder dystocia and the extent of neonatal complications. For example, the median interval from head-to-body delivery for uncomplicated births was 1.0 minute; for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy alone, it was 2.0 minutes; and for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy and neonatal depression, the interval was 5.3 minutes (P <.001). There was no single cutoff, however, that was completely discriminating with regard to whether neonatal depression would occur.

Strengths and weaknesses of the trial

As the authors note, one limitation of their study is a lack of precision in the recorded duration of shoulder dystocia cases, given that “it appears that clinicians often rounded” the stated times.

Other types of bias that may have affected the findings include:

- Selection bias. In an observational study such as this, it is typically ideal to draw the cases and controls from the same underlying population in an effort to limit the occurrence of other potentially confounding factors, both known and unknown. In this study, however, the uncomplicated cases came from one institution over 10 years, whereas the complicated cases came from a medicolegal database one author had accumulated over 15 years. Because these clearly are very different populations, the reported association between head-to-body delivery interval and brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression may be related to characteristics other than, or in addition to, duration of the dystocia. For example, there may have been complicated cases that did not result in legal action. If the duration of the dystocia is in any way related to the chance that medicolegal action occurs, the relationship between duration and the presence of complication will be affected.

- Ascertainment bias. Because this study lacked a standard approach to the recording of duration, ascertainment bias may have affected the results. It is possible, for example, that the knowledge that a complication did or did not occur could have affected whether the duration was recorded or how much time was documented.

Complications of shoulder dystocia are rare

Ultimately, the primary question posed in this article is difficult to answer. Although shoulder dystocia occurs in approximately 1% of births, major adverse perinatal outcomes occur in only a fraction of these cases. That fact means that an event such as permanent brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression, let alone actual hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, occurs only in the context of thousands of births.

The data published to date,3,4 including this study, should offer some reassurance to obstetric care providers. Long-term adverse outcomes are uncommon in shoulder dystocia. Even intermediate outcomes such as neonatal depression, when they do occur, appear to be uncommon when the shoulder dystocia is of relatively short duration.

When shoulder dystocia does occur, however, providers should maintain situational awareness, being cognizant of the time that elapses, so that the continuation of appropriate and coordinated maneuvers can be ensured.

WILLIAM A. GROBMAN, MD, MBA

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Does the use of multiple maneuvers in the management of shoulder dystocia increase the risk of neonatal injury?

Robert B. Gherman, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2011)

Shoulder dystocia is a well-described obstetric complication that occurs in approximately 1% of deliveries.1 It has been associated with adverse maternal outcomes as well as adverse perinatal outcomes, including fracture, nerve palsy, and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy.

Although multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia have been described, experts have not yet been able to combine them into an accurate, discriminating, clinically useful shoulder dystocia prediction model; therefore, shoulder dystocia remains an unpredictable event.2 We also lack a strategy to prevent shoulder dystocia. Because we cannot predict or prevent it, a provider’s response to shoulder dystocia, once it occurs, is seminal, in terms of management.

Details of the study

As Lerner and colleagues concisely state, when shoulder dystocia occurs, there is a need for caution in the application of force during maneuvers and a “countervailing need to achieve delivery.” It is in a provider’s interest, then, to have knowledge of whether there is a time at which that countervailing need to achieve delivery takes on greater relative significance.

In an effort to address this issue, the authors examined the relationship between the duration of shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression (defined as the need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation; a pH level below 7.0; an Apgar score below 6 at 5 minutes; or death).

In their study, 127 births involving uncomplicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., no evidence of neonatal trauma or depression) from a single institution were compared with 55 births involving complicated shoulder dystocia (i.e., the occurrence of brachial plexus palsy with or without neonatal depression).

Lerner and colleagues found a correlation between the duration of shoulder dystocia and the extent of neonatal complications. For example, the median interval from head-to-body delivery for uncomplicated births was 1.0 minute; for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy alone, it was 2.0 minutes; and for births complicated by brachial plexus palsy and neonatal depression, the interval was 5.3 minutes (P <.001). There was no single cutoff, however, that was completely discriminating with regard to whether neonatal depression would occur.

Strengths and weaknesses of the trial

As the authors note, one limitation of their study is a lack of precision in the recorded duration of shoulder dystocia cases, given that “it appears that clinicians often rounded” the stated times.

Other types of bias that may have affected the findings include:

- Selection bias. In an observational study such as this, it is typically ideal to draw the cases and controls from the same underlying population in an effort to limit the occurrence of other potentially confounding factors, both known and unknown. In this study, however, the uncomplicated cases came from one institution over 10 years, whereas the complicated cases came from a medicolegal database one author had accumulated over 15 years. Because these clearly are very different populations, the reported association between head-to-body delivery interval and brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression may be related to characteristics other than, or in addition to, duration of the dystocia. For example, there may have been complicated cases that did not result in legal action. If the duration of the dystocia is in any way related to the chance that medicolegal action occurs, the relationship between duration and the presence of complication will be affected.

- Ascertainment bias. Because this study lacked a standard approach to the recording of duration, ascertainment bias may have affected the results. It is possible, for example, that the knowledge that a complication did or did not occur could have affected whether the duration was recorded or how much time was documented.

Complications of shoulder dystocia are rare

Ultimately, the primary question posed in this article is difficult to answer. Although shoulder dystocia occurs in approximately 1% of births, major adverse perinatal outcomes occur in only a fraction of these cases. That fact means that an event such as permanent brachial plexus palsy or neonatal depression, let alone actual hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, occurs only in the context of thousands of births.

The data published to date,3,4 including this study, should offer some reassurance to obstetric care providers. Long-term adverse outcomes are uncommon in shoulder dystocia. Even intermediate outcomes such as neonatal depression, when they do occur, appear to be uncommon when the shoulder dystocia is of relatively short duration.

When shoulder dystocia does occur, however, providers should maintain situational awareness, being cognizant of the time that elapses, so that the continuation of appropriate and coordinated maneuvers can be ensured.

WILLIAM A. GROBMAN, MD, MBA

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: an evidence-based evaluation of the obstetric nightmare. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45(2):345-362.

2. Grobman WA, Stamilio DM. Methods of clinical prediction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):888-894.

3. Allen RH, Rosenbaum TC, Ghidini A, Poggi SH, Spong CY. Correlating head-to-body delivery intervals with neonatal depression in vaginal births that result in permanent brachial plexus injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):839-842.

4. Leung TY, Stuart O, Sahota DS, Suen SS, Lau TK, Lao TT. Head-to-body interval and risk of fetal acidosis and hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in shoulder dystocia: a retrospective review. BJOG. 2011;118(4):474-479.

1. Gherman RB. Shoulder dystocia: an evidence-based evaluation of the obstetric nightmare. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45(2):345-362.

2. Grobman WA, Stamilio DM. Methods of clinical prediction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):888-894.

3. Allen RH, Rosenbaum TC, Ghidini A, Poggi SH, Spong CY. Correlating head-to-body delivery intervals with neonatal depression in vaginal births that result in permanent brachial plexus injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):839-842.

4. Leung TY, Stuart O, Sahota DS, Suen SS, Lau TK, Lao TT. Head-to-body interval and risk of fetal acidosis and hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in shoulder dystocia: a retrospective review. BJOG. 2011;118(4):474-479.

How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery

You are performing the fourth cesarean delivery on your patient, a 30-year-old G4P3. The abdominal and uterine incisions go well, and delivery is uneventful. As you prepare to close the uterus, you notice that there is a hole in the bladder 5 cm long. You realize that the injury likely occurred before you made the uterine incision, at the time you mobilized the bladder from the lower uterine segment.

Now, how will you repair the injury to the bladder?

Injury to the bladder or ureter occurs in about 0.3% of cesarean deliveries and about 1% of gynecologic surgical procedures. Bladder injury is more common than injury to the ureter.1,2

Intraoperative recognition of the injury usually permits prompt and successful repair. Delayed recognition of the injury—in the postoperative period—is associated with serious complications, however.

Preoperative planning—that ounce of prevention

Risk factors for cesarean-related bladder injury include:

- repeat delivery

- emergency delivery

- delivery after a protracted second stage of labor.

Bladder injury has been reported to occur in about 0.2% of primary cesarean deliveries and in 0.6% of repeat cesarean deliveries.3

During repeat cesarean delivery, two surgical challenges are often encountered: The bladder 1) is densely adherent to the underlying lower uterine segment and 2) might have healed in a position much higher on the uterus, thereby blocking access to the lower uterine segment.

During emergency cesarean delivery for placental abruption or fetal bradycardia, bladder injury might occur because visualization and dissection of each surgical plane is less than optimal.

In cesarean delivery after a protracted second stage, the vagina—rather than the lower uterine segment—might be incised because of difficulty identifying the interface between uterus and vagina, resulting in an increased risk of bladder injury.

Tips. You can reduce the risk of injury to the bladder as follows:

- Enter the peritoneal cavity at the most superior segment of the abdominal incision; use sharp, rather than blunt, dissection to separate a densely adherent bladder from the uterus.

- When your patient is carrying a large fetus and experiencing a prolonged second stage of labor—and requires cesarean delivery—consider performing a low vertical uterine incision to reduce the risk of extensions into the broad ligament.

Repairing injury to the dome

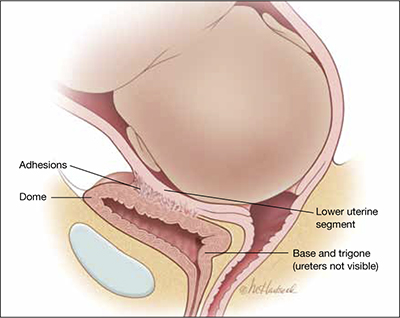

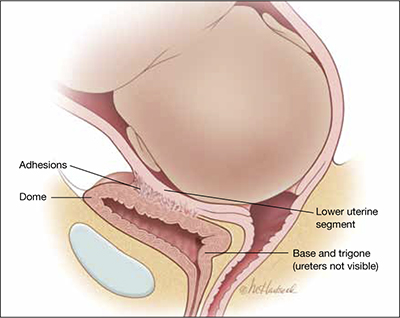

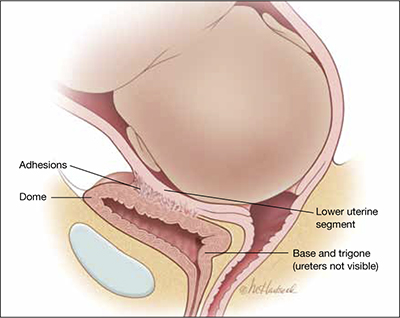

The bladder comprises the dome superiorly and the base inferiorly. The base of the bladder contains the trigone, which includes the ureters that enter posteriorly and the urethra that exits at the most inferior portion of the bladder (see the FIGURE).

The bladder at delivery: Position and parts

During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone.During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone. You can demonstrate this by trying to feel the tip of the Foley catheter bulb through a bladder injury that occurs during cesarean delivery: The trigone is, typically, more than 6 cm—and often more than 10 cm—distant from injury in the dome.

ObGyns are highly qualified to repair an injury in the dome. The surgical steps often used to repair cystotomy in the dome of the bladder include:

- Identify the extent of injury; ensure that it is limited to the dome (that is, does not involve the trigone or is not a large one that extends deep into the posterior bladder).

- Repair the cystotomy in two layers, using absorbable suture. Never use non-absorbable suture because it might act as a nidus for bladder calculi to form. Close the first layer with simple running 3-0 absorbable suture. Close the second layer using running imbricating 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture.

- To ensure integrity of the repair and to detect the presence of any other bladder injuries, backfill the bladder with a sterile milk or indigo carmine dye through the Foley catheter.

- The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days.

Repairing injury to the trigone or ureters

In most cases, an urologist or urogynecologist should be called in to repair an injury to the trigone or ureter. A possible exception: When it is clear that a stitch has kinked one of the ureters, and removing that stitch resolves the problem.

If you detect a large injury to the bladder—one that involves the posterior wall—consider that the trigone might be injured. Repair of the bladder should then be delayed until a ureteral dye test can be performed.

Ureteral dye test. Inject 5 mL of indigo carmine dye intravenously, and directly observe the flow of dye-stained urine from both ureteral orifices. If you see that dye is flowing from both ureteral orifices and you do not see dye in the retroperitoneal and intra-abdominal spaces, ureteral integrity is likely and you can proceed to repair the injury to the dome.

An alternative test. Urologists often place ureteral catheters under direct visualization, using the injury in the dome to obtain access to the ureteral orifices.4 If a ureteral catheter cannot be advanced to the renal pelvis, a kink or occlusion of the ureter is a possibility. The ureteral catheters not only aid in diagnosing injury but help maintain ureteral patency and prevent ureteral obstruction caused by postoperative swelling.

Ureteral injuries that occur during cesarean delivery often go undetected intraoperatively5; most occur when a transverse uterine incision extends into the broad ligament or vagina. If you suspect ureteral injury and have determined that the bladder is intact, you can take either of two approaches to assessing ureteral patency: 1) perform cystoscopy and insert ureteral catheters in a retrograde manner or 2) incise the dome and insert ureteral catheters under direct visualization.6

After a complex bladder injury has been repaired, intraperitoneal drains may be placed to monitor for extravasation of urine into the peritoneal cavity and to actively drain fluid that might accumulate there.

Postop care The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days after the repair. Most experts recommend that a voiding cystogram be performed before the Foley catheter is discontinued; some, however, note that complete healing after repair of a bladder injury at cesarean delivery is to be expected, making a cystogram unnecessary.

Late detection. Postoperative events that might alert you to undetected ureteral injury include pain at the costovertebral angle, oliguria, hematuria, watery vaginal discharge, persistent fever, and abdominal distention.

“I need help!” Sorry—it may not be on the way.

According to the American College of Surgeons, the median age of urologists is older than 50 years7; in many communities, increasing numbers of senior urologists are reluctant to take night and weekend call for emergencies that occur on their hospital’s OB service. Consequently, you and your colleagues might find yourselves compelled to care for a greater number of the urinary tract injuries that occur during cesarean delivery without the immediately available aid of an urologist. But, as I noted, ObGyns are well-trained to take primary responsibility for the repair of most of these injuries.

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- hat can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

1. Gilmour DT, Das S, Flowerdew G. Rates of urinary tract injury from gynecologic surgery and the role of intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1366-1372.

2. Phipps MG, Watabe B, Clemons JL, Weitzen S, Myers DL. Risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):156-160.

3. Eisenkop SM, Richman R, Platt LD, Paul RH. Urinary tract injury during cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60(5):591-596.

4. Yossepowitch O, Baniel J, Livne PM. Urological injuries during cesarean section: intraoperative diagnosis and management. J Urol. 2004;172(1):196-199.

5. Rajasekar D, Hall M. Urinary tract injuries during obstetric intervention. Br J Obstet Gyneaecol. 1997;104(6):731-734.

6. Mendez LE. Iatrogenic injuries in gynecologic cancer surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(4):897-923.

7. Walker E, Poley S, Ricketts T. The Aging Surgeon Population. Chapel Hill, NC: American College of Surgeons Health Policy Research Institute; May 2010. http://operationpatientaccess.facs.org/userfiles/file/ACS%20HPRI%20 %20The%20Aging%20Surgeon%20Population%20-%20May%202010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

You are performing the fourth cesarean delivery on your patient, a 30-year-old G4P3. The abdominal and uterine incisions go well, and delivery is uneventful. As you prepare to close the uterus, you notice that there is a hole in the bladder 5 cm long. You realize that the injury likely occurred before you made the uterine incision, at the time you mobilized the bladder from the lower uterine segment.

Now, how will you repair the injury to the bladder?

Injury to the bladder or ureter occurs in about 0.3% of cesarean deliveries and about 1% of gynecologic surgical procedures. Bladder injury is more common than injury to the ureter.1,2

Intraoperative recognition of the injury usually permits prompt and successful repair. Delayed recognition of the injury—in the postoperative period—is associated with serious complications, however.

Preoperative planning—that ounce of prevention

Risk factors for cesarean-related bladder injury include:

- repeat delivery

- emergency delivery

- delivery after a protracted second stage of labor.

Bladder injury has been reported to occur in about 0.2% of primary cesarean deliveries and in 0.6% of repeat cesarean deliveries.3

During repeat cesarean delivery, two surgical challenges are often encountered: The bladder 1) is densely adherent to the underlying lower uterine segment and 2) might have healed in a position much higher on the uterus, thereby blocking access to the lower uterine segment.

During emergency cesarean delivery for placental abruption or fetal bradycardia, bladder injury might occur because visualization and dissection of each surgical plane is less than optimal.

In cesarean delivery after a protracted second stage, the vagina—rather than the lower uterine segment—might be incised because of difficulty identifying the interface between uterus and vagina, resulting in an increased risk of bladder injury.

Tips. You can reduce the risk of injury to the bladder as follows:

- Enter the peritoneal cavity at the most superior segment of the abdominal incision; use sharp, rather than blunt, dissection to separate a densely adherent bladder from the uterus.

- When your patient is carrying a large fetus and experiencing a prolonged second stage of labor—and requires cesarean delivery—consider performing a low vertical uterine incision to reduce the risk of extensions into the broad ligament.

Repairing injury to the dome

The bladder comprises the dome superiorly and the base inferiorly. The base of the bladder contains the trigone, which includes the ureters that enter posteriorly and the urethra that exits at the most inferior portion of the bladder (see the FIGURE).

The bladder at delivery: Position and parts

During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone.During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone. You can demonstrate this by trying to feel the tip of the Foley catheter bulb through a bladder injury that occurs during cesarean delivery: The trigone is, typically, more than 6 cm—and often more than 10 cm—distant from injury in the dome.

ObGyns are highly qualified to repair an injury in the dome. The surgical steps often used to repair cystotomy in the dome of the bladder include:

- Identify the extent of injury; ensure that it is limited to the dome (that is, does not involve the trigone or is not a large one that extends deep into the posterior bladder).

- Repair the cystotomy in two layers, using absorbable suture. Never use non-absorbable suture because it might act as a nidus for bladder calculi to form. Close the first layer with simple running 3-0 absorbable suture. Close the second layer using running imbricating 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture.

- To ensure integrity of the repair and to detect the presence of any other bladder injuries, backfill the bladder with a sterile milk or indigo carmine dye through the Foley catheter.

- The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days.

Repairing injury to the trigone or ureters

In most cases, an urologist or urogynecologist should be called in to repair an injury to the trigone or ureter. A possible exception: When it is clear that a stitch has kinked one of the ureters, and removing that stitch resolves the problem.

If you detect a large injury to the bladder—one that involves the posterior wall—consider that the trigone might be injured. Repair of the bladder should then be delayed until a ureteral dye test can be performed.

Ureteral dye test. Inject 5 mL of indigo carmine dye intravenously, and directly observe the flow of dye-stained urine from both ureteral orifices. If you see that dye is flowing from both ureteral orifices and you do not see dye in the retroperitoneal and intra-abdominal spaces, ureteral integrity is likely and you can proceed to repair the injury to the dome.

An alternative test. Urologists often place ureteral catheters under direct visualization, using the injury in the dome to obtain access to the ureteral orifices.4 If a ureteral catheter cannot be advanced to the renal pelvis, a kink or occlusion of the ureter is a possibility. The ureteral catheters not only aid in diagnosing injury but help maintain ureteral patency and prevent ureteral obstruction caused by postoperative swelling.

Ureteral injuries that occur during cesarean delivery often go undetected intraoperatively5; most occur when a transverse uterine incision extends into the broad ligament or vagina. If you suspect ureteral injury and have determined that the bladder is intact, you can take either of two approaches to assessing ureteral patency: 1) perform cystoscopy and insert ureteral catheters in a retrograde manner or 2) incise the dome and insert ureteral catheters under direct visualization.6

After a complex bladder injury has been repaired, intraperitoneal drains may be placed to monitor for extravasation of urine into the peritoneal cavity and to actively drain fluid that might accumulate there.

Postop care The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days after the repair. Most experts recommend that a voiding cystogram be performed before the Foley catheter is discontinued; some, however, note that complete healing after repair of a bladder injury at cesarean delivery is to be expected, making a cystogram unnecessary.

Late detection. Postoperative events that might alert you to undetected ureteral injury include pain at the costovertebral angle, oliguria, hematuria, watery vaginal discharge, persistent fever, and abdominal distention.

“I need help!” Sorry—it may not be on the way.

According to the American College of Surgeons, the median age of urologists is older than 50 years7; in many communities, increasing numbers of senior urologists are reluctant to take night and weekend call for emergencies that occur on their hospital’s OB service. Consequently, you and your colleagues might find yourselves compelled to care for a greater number of the urinary tract injuries that occur during cesarean delivery without the immediately available aid of an urologist. But, as I noted, ObGyns are well-trained to take primary responsibility for the repair of most of these injuries.

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- hat can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

You are performing the fourth cesarean delivery on your patient, a 30-year-old G4P3. The abdominal and uterine incisions go well, and delivery is uneventful. As you prepare to close the uterus, you notice that there is a hole in the bladder 5 cm long. You realize that the injury likely occurred before you made the uterine incision, at the time you mobilized the bladder from the lower uterine segment.

Now, how will you repair the injury to the bladder?

Injury to the bladder or ureter occurs in about 0.3% of cesarean deliveries and about 1% of gynecologic surgical procedures. Bladder injury is more common than injury to the ureter.1,2

Intraoperative recognition of the injury usually permits prompt and successful repair. Delayed recognition of the injury—in the postoperative period—is associated with serious complications, however.

Preoperative planning—that ounce of prevention

Risk factors for cesarean-related bladder injury include:

- repeat delivery

- emergency delivery

- delivery after a protracted second stage of labor.

Bladder injury has been reported to occur in about 0.2% of primary cesarean deliveries and in 0.6% of repeat cesarean deliveries.3

During repeat cesarean delivery, two surgical challenges are often encountered: The bladder 1) is densely adherent to the underlying lower uterine segment and 2) might have healed in a position much higher on the uterus, thereby blocking access to the lower uterine segment.

During emergency cesarean delivery for placental abruption or fetal bradycardia, bladder injury might occur because visualization and dissection of each surgical plane is less than optimal.

In cesarean delivery after a protracted second stage, the vagina—rather than the lower uterine segment—might be incised because of difficulty identifying the interface between uterus and vagina, resulting in an increased risk of bladder injury.

Tips. You can reduce the risk of injury to the bladder as follows:

- Enter the peritoneal cavity at the most superior segment of the abdominal incision; use sharp, rather than blunt, dissection to separate a densely adherent bladder from the uterus.

- When your patient is carrying a large fetus and experiencing a prolonged second stage of labor—and requires cesarean delivery—consider performing a low vertical uterine incision to reduce the risk of extensions into the broad ligament.

Repairing injury to the dome

The bladder comprises the dome superiorly and the base inferiorly. The base of the bladder contains the trigone, which includes the ureters that enter posteriorly and the urethra that exits at the most inferior portion of the bladder (see the FIGURE).

The bladder at delivery: Position and parts

During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone.During cesarean delivery, most injuries to the bladder occur in the dome, far from the trigone. You can demonstrate this by trying to feel the tip of the Foley catheter bulb through a bladder injury that occurs during cesarean delivery: The trigone is, typically, more than 6 cm—and often more than 10 cm—distant from injury in the dome.

ObGyns are highly qualified to repair an injury in the dome. The surgical steps often used to repair cystotomy in the dome of the bladder include:

- Identify the extent of injury; ensure that it is limited to the dome (that is, does not involve the trigone or is not a large one that extends deep into the posterior bladder).

- Repair the cystotomy in two layers, using absorbable suture. Never use non-absorbable suture because it might act as a nidus for bladder calculi to form. Close the first layer with simple running 3-0 absorbable suture. Close the second layer using running imbricating 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable suture.

- To ensure integrity of the repair and to detect the presence of any other bladder injuries, backfill the bladder with a sterile milk or indigo carmine dye through the Foley catheter.

- The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days.

Repairing injury to the trigone or ureters

In most cases, an urologist or urogynecologist should be called in to repair an injury to the trigone or ureter. A possible exception: When it is clear that a stitch has kinked one of the ureters, and removing that stitch resolves the problem.

If you detect a large injury to the bladder—one that involves the posterior wall—consider that the trigone might be injured. Repair of the bladder should then be delayed until a ureteral dye test can be performed.

Ureteral dye test. Inject 5 mL of indigo carmine dye intravenously, and directly observe the flow of dye-stained urine from both ureteral orifices. If you see that dye is flowing from both ureteral orifices and you do not see dye in the retroperitoneal and intra-abdominal spaces, ureteral integrity is likely and you can proceed to repair the injury to the dome.

An alternative test. Urologists often place ureteral catheters under direct visualization, using the injury in the dome to obtain access to the ureteral orifices.4 If a ureteral catheter cannot be advanced to the renal pelvis, a kink or occlusion of the ureter is a possibility. The ureteral catheters not only aid in diagnosing injury but help maintain ureteral patency and prevent ureteral obstruction caused by postoperative swelling.

Ureteral injuries that occur during cesarean delivery often go undetected intraoperatively5; most occur when a transverse uterine incision extends into the broad ligament or vagina. If you suspect ureteral injury and have determined that the bladder is intact, you can take either of two approaches to assessing ureteral patency: 1) perform cystoscopy and insert ureteral catheters in a retrograde manner or 2) incise the dome and insert ureteral catheters under direct visualization.6

After a complex bladder injury has been repaired, intraperitoneal drains may be placed to monitor for extravasation of urine into the peritoneal cavity and to actively drain fluid that might accumulate there.

Postop care The bladder should be drained by Foley catheter for approximately 7 days after the repair. Most experts recommend that a voiding cystogram be performed before the Foley catheter is discontinued; some, however, note that complete healing after repair of a bladder injury at cesarean delivery is to be expected, making a cystogram unnecessary.

Late detection. Postoperative events that might alert you to undetected ureteral injury include pain at the costovertebral angle, oliguria, hematuria, watery vaginal discharge, persistent fever, and abdominal distention.

“I need help!” Sorry—it may not be on the way.

According to the American College of Surgeons, the median age of urologists is older than 50 years7; in many communities, increasing numbers of senior urologists are reluctant to take night and weekend call for emergencies that occur on their hospital’s OB service. Consequently, you and your colleagues might find yourselves compelled to care for a greater number of the urinary tract injuries that occur during cesarean delivery without the immediately available aid of an urologist. But, as I noted, ObGyns are well-trained to take primary responsibility for the repair of most of these injuries.

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- hat can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

1. Gilmour DT, Das S, Flowerdew G. Rates of urinary tract injury from gynecologic surgery and the role of intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1366-1372.

2. Phipps MG, Watabe B, Clemons JL, Weitzen S, Myers DL. Risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):156-160.

3. Eisenkop SM, Richman R, Platt LD, Paul RH. Urinary tract injury during cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60(5):591-596.

4. Yossepowitch O, Baniel J, Livne PM. Urological injuries during cesarean section: intraoperative diagnosis and management. J Urol. 2004;172(1):196-199.

5. Rajasekar D, Hall M. Urinary tract injuries during obstetric intervention. Br J Obstet Gyneaecol. 1997;104(6):731-734.

6. Mendez LE. Iatrogenic injuries in gynecologic cancer surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(4):897-923.

7. Walker E, Poley S, Ricketts T. The Aging Surgeon Population. Chapel Hill, NC: American College of Surgeons Health Policy Research Institute; May 2010. http://operationpatientaccess.facs.org/userfiles/file/ACS%20HPRI%20 %20The%20Aging%20Surgeon%20Population%20-%20May%202010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

1. Gilmour DT, Das S, Flowerdew G. Rates of urinary tract injury from gynecologic surgery and the role of intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1366-1372.

2. Phipps MG, Watabe B, Clemons JL, Weitzen S, Myers DL. Risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):156-160.

3. Eisenkop SM, Richman R, Platt LD, Paul RH. Urinary tract injury during cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60(5):591-596.

4. Yossepowitch O, Baniel J, Livne PM. Urological injuries during cesarean section: intraoperative diagnosis and management. J Urol. 2004;172(1):196-199.

5. Rajasekar D, Hall M. Urinary tract injuries during obstetric intervention. Br J Obstet Gyneaecol. 1997;104(6):731-734.

6. Mendez LE. Iatrogenic injuries in gynecologic cancer surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(4):897-923.

7. Walker E, Poley S, Ricketts T. The Aging Surgeon Population. Chapel Hill, NC: American College of Surgeons Health Policy Research Institute; May 2010. http://operationpatientaccess.facs.org/userfiles/file/ACS%20HPRI%20 %20The%20Aging%20Surgeon%20Population%20-%20May%202010.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2011.

Purity of Compounded 17P Is Questioned

The Food and Drug Administration is reviewing the results of tests conducted by the manufacturer of Makena, the approved version of a compounded product for preventing preterm births, which the company said has identified some problems with other compounded versions.

Makena, a compounded formulation of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P), was approved by the FDA in February 2011, providing for the first time an approved version of product that had previously been compounded in local pharmacies and used to reduce the risk of certain preterm births in patients who had already experienced a prior preterm birth.

The Nov. 8 FDA statement says that Makena manufacturer K-V Pharmaceutical provided information about tests that identified “variability” in the purity and potency of bulk hydroxyprogesterone caproate and compounded products that use it as the active ingredient. The FDA “has not validated or otherwise confirmed” these results, but “has carefully reviewed the data and will conduct an onsite review of the laboratory analyses.” In addition, the FDA has begun “its own sampling and analysis of compounded hydroxyprogesterone caproate products and the bulk [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used to make them,” a process that is ongoing, according to the statement.

“In the meantime, we remind physicians and patients that before approving the Makena new drug application, FDA reviewed manufacturing information, such as the source of the [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used by its manufacturer, proposed manufacturing processes, and the firm's adherence to current good manufacturing practice,” the statement said, adding: “Therefore, as with other approved drugs, greater assurance of safety and effectiveness is generally provided by the approved product than by a compounded product.”

Soon after Makena was approved, the initial enthusiasm over the availability of a more reliable product was tempered once it became clear that Makena would cost much more than the previously available products, eliciting concerns that this would affect access to the product among poor women, who are considered at greatest risk of preterm labor.

Despite the availability of an approved product, the FDA released a statement in March that said, “in order to support access to this important drug,” the agency had no plans to take enforcement actions against pharmacies when there was a valid prescription for hydroxyprogesterone caproate for an individual patient, unless there were problems with the quality or safety of the product, or they were not being compounded in accordance with the appropriate standards for compounding sterile products. The FDA issued that statement after learning that the company had sent letters to pharmacists saying that the agency would no longer exercise such discretion, according to the current statement.

The Food and Drug Administration is reviewing the results of tests conducted by the manufacturer of Makena, the approved version of a compounded product for preventing preterm births, which the company said has identified some problems with other compounded versions.

Makena, a compounded formulation of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P), was approved by the FDA in February 2011, providing for the first time an approved version of product that had previously been compounded in local pharmacies and used to reduce the risk of certain preterm births in patients who had already experienced a prior preterm birth.

The Nov. 8 FDA statement says that Makena manufacturer K-V Pharmaceutical provided information about tests that identified “variability” in the purity and potency of bulk hydroxyprogesterone caproate and compounded products that use it as the active ingredient. The FDA “has not validated or otherwise confirmed” these results, but “has carefully reviewed the data and will conduct an onsite review of the laboratory analyses.” In addition, the FDA has begun “its own sampling and analysis of compounded hydroxyprogesterone caproate products and the bulk [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used to make them,” a process that is ongoing, according to the statement.

“In the meantime, we remind physicians and patients that before approving the Makena new drug application, FDA reviewed manufacturing information, such as the source of the [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used by its manufacturer, proposed manufacturing processes, and the firm's adherence to current good manufacturing practice,” the statement said, adding: “Therefore, as with other approved drugs, greater assurance of safety and effectiveness is generally provided by the approved product than by a compounded product.”

Soon after Makena was approved, the initial enthusiasm over the availability of a more reliable product was tempered once it became clear that Makena would cost much more than the previously available products, eliciting concerns that this would affect access to the product among poor women, who are considered at greatest risk of preterm labor.

Despite the availability of an approved product, the FDA released a statement in March that said, “in order to support access to this important drug,” the agency had no plans to take enforcement actions against pharmacies when there was a valid prescription for hydroxyprogesterone caproate for an individual patient, unless there were problems with the quality or safety of the product, or they were not being compounded in accordance with the appropriate standards for compounding sterile products. The FDA issued that statement after learning that the company had sent letters to pharmacists saying that the agency would no longer exercise such discretion, according to the current statement.

The Food and Drug Administration is reviewing the results of tests conducted by the manufacturer of Makena, the approved version of a compounded product for preventing preterm births, which the company said has identified some problems with other compounded versions.

Makena, a compounded formulation of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P), was approved by the FDA in February 2011, providing for the first time an approved version of product that had previously been compounded in local pharmacies and used to reduce the risk of certain preterm births in patients who had already experienced a prior preterm birth.

The Nov. 8 FDA statement says that Makena manufacturer K-V Pharmaceutical provided information about tests that identified “variability” in the purity and potency of bulk hydroxyprogesterone caproate and compounded products that use it as the active ingredient. The FDA “has not validated or otherwise confirmed” these results, but “has carefully reviewed the data and will conduct an onsite review of the laboratory analyses.” In addition, the FDA has begun “its own sampling and analysis of compounded hydroxyprogesterone caproate products and the bulk [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used to make them,” a process that is ongoing, according to the statement.

“In the meantime, we remind physicians and patients that before approving the Makena new drug application, FDA reviewed manufacturing information, such as the source of the [active pharmaceutical ingredients] used by its manufacturer, proposed manufacturing processes, and the firm's adherence to current good manufacturing practice,” the statement said, adding: “Therefore, as with other approved drugs, greater assurance of safety and effectiveness is generally provided by the approved product than by a compounded product.”

Soon after Makena was approved, the initial enthusiasm over the availability of a more reliable product was tempered once it became clear that Makena would cost much more than the previously available products, eliciting concerns that this would affect access to the product among poor women, who are considered at greatest risk of preterm labor.

Despite the availability of an approved product, the FDA released a statement in March that said, “in order to support access to this important drug,” the agency had no plans to take enforcement actions against pharmacies when there was a valid prescription for hydroxyprogesterone caproate for an individual patient, unless there were problems with the quality or safety of the product, or they were not being compounded in accordance with the appropriate standards for compounding sterile products. The FDA issued that statement after learning that the company had sent letters to pharmacists saying that the agency would no longer exercise such discretion, according to the current statement.

From the Food and Drug Administration

Foley Catheter Bests Prostaglandin E2 Gel

Use of a Foley catheter for labor induction in women with an unfavorable cervix at term resulted in a similar cesarean section rate to use of prostaglandin E2 gel for labor induction, but with fewer maternal and neonatal side effects, according to findings from an open-label randomized controlled trial involving more than 800 women.

Cesarean section, most often done for failure to progress during the first stage of labor, was performed in 23% of 411 women induced using a Foley catheter, and in 20% of 408 women induced using vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (relative risk, 1.13), Dr. Marta Jozwiak of Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, the Netherlands, and her colleagues from the PROBAAT Study Group reported.

The frequency of vaginal instrumental deliveries was similar in the two groups as well (11% and 13% in the Foley catheter and prostaglandin E2 groups, respectively), the investigators said (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0]).

Two serious maternal adverse events occurred, both in the prostaglandin group. These included one uterine perforation after insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during oxytocin augmentation, they said, noting that both neonates were born in good clinical condition, but were admitted to the neonatal ward with suspected infection.

Four minor maternal adverse events occurred, including three allergic reactions (in one woman in the Foley catheter group and in two women in the prostaglandin E2 group), and blood loss on a second insertion of the catheter in one woman. Also, the rate of suspected intrapartum infection was significantly lower in the Foley catheter group (1% vs. 3%).

As for neonatal adverse events, the rate of admissions to the neonatal ward was significantly higher in the prostaglandin E2 group (12% vs. 20%), Dr. Jozwiak and her associates said.

Patients in the PROBAAT trial included women beyond 37 weeks' gestation with a singleton pregnancy in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix as defined by a Bishop score less than 6. The women were enrolled at 12 centers throughout the Netherlands between Feb. 10, 2009, and May 17, 2010, and all had an indication for labor induction, and had no prior cesarean sections.

The findings in regard to cesarean section rates when labor induction is performed using a Foley catheter vs. prostaglandin E2 were confirmed by a meta-analysis that included data from this study. The meta-analysis also demonstrated that Foley catheter induction was associated with reduced rates of hyperstimulation (odds ratio, 0.44) and postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 0.60), the investigators reported, noting that although the use of a Foley catheter for labor induction did not increase the vaginal delivery rate when compared with use of prostaglandin E2 as they had hypothesized, the findings nonetheless support the use of Foley catheters.

“After induction with a Foley catheter, the overall number of operative deliveries for suspected fetal distress was lower, fewer mothers were treated with intrapartum antibiotics, and significantly fewer neonates were admitted to the neonatal ward,” they said, adding: “We therefore think that a Foley catheter should be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

Also, in light of the low cost and easy storage of Foley catheters, their use could be suitable for developing countries and low-resource settings, Dr. Jozwiak and her associates noted.

Future studies should compare the use of Foley catheters with other prostaglandin preparations such as prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) which is becoming increasingly popular worldwide, and should evaluate the use of Foley catheters in women with a prior cesarean section, they suggested.

Dr. Jane E.

Norman and Dr. Sarah Stock note that the findings that intracervical

placement of a Foley catheter induces cervical ripening without inducing

uterine contractions and is as successful as prostaglandin for inducing

labor, could have important implications for women with a prior

cesarean section.

In these women, induction with prostaglandins is

associated with uterine rupture, they noted, explaining that

prostaglandins affect both cervical ripening and contractions

simultaneously, whereas the ideal strategy for induction is likely

administration of a cervical ripening agent before stimulation of

contractions. This, they argue, would decrease the need for fetal

monitoring during ripening and reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

“Although

women with a previous cesarean section were excluded from Jozwiak and

colleagues' study, a Foley catheter could be the ideal induction agent

in this situation and should be assessed further in randomized trials,”

they said, adding that if such trials are done, avoidance of maternal

and neonatal mortality and morbidity should be included as primary

outcome measures, as they are “arguably as important as speed and

avoidance of cesarean section.”

DR. NORMAN and DR. STOCK are

with the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health and the Queen's Medical

Research Center at the University of Edinburgh. Their comments were

taken from an editorial accompanying the article by Dr. Jozwiak and

colleagues (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X]). Dr. Norman

reported receiving fees for acting as a consultant for Preglem and is

an unpaid member of an advisory board for Hologic. Dr. Stock had no

relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Jane E.

Norman and Dr. Sarah Stock note that the findings that intracervical

placement of a Foley catheter induces cervical ripening without inducing

uterine contractions and is as successful as prostaglandin for inducing

labor, could have important implications for women with a prior

cesarean section.

In these women, induction with prostaglandins is

associated with uterine rupture, they noted, explaining that

prostaglandins affect both cervical ripening and contractions

simultaneously, whereas the ideal strategy for induction is likely

administration of a cervical ripening agent before stimulation of

contractions. This, they argue, would decrease the need for fetal

monitoring during ripening and reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

“Although

women with a previous cesarean section were excluded from Jozwiak and

colleagues' study, a Foley catheter could be the ideal induction agent

in this situation and should be assessed further in randomized trials,”

they said, adding that if such trials are done, avoidance of maternal

and neonatal mortality and morbidity should be included as primary

outcome measures, as they are “arguably as important as speed and

avoidance of cesarean section.”

DR. NORMAN and DR. STOCK are

with the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health and the Queen's Medical

Research Center at the University of Edinburgh. Their comments were

taken from an editorial accompanying the article by Dr. Jozwiak and

colleagues (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X]). Dr. Norman

reported receiving fees for acting as a consultant for Preglem and is

an unpaid member of an advisory board for Hologic. Dr. Stock had no

relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Jane E.

Norman and Dr. Sarah Stock note that the findings that intracervical

placement of a Foley catheter induces cervical ripening without inducing

uterine contractions and is as successful as prostaglandin for inducing

labor, could have important implications for women with a prior

cesarean section.

In these women, induction with prostaglandins is

associated with uterine rupture, they noted, explaining that

prostaglandins affect both cervical ripening and contractions

simultaneously, whereas the ideal strategy for induction is likely

administration of a cervical ripening agent before stimulation of

contractions. This, they argue, would decrease the need for fetal

monitoring during ripening and reduce the risk of uterine rupture.

“Although

women with a previous cesarean section were excluded from Jozwiak and

colleagues' study, a Foley catheter could be the ideal induction agent

in this situation and should be assessed further in randomized trials,”

they said, adding that if such trials are done, avoidance of maternal

and neonatal mortality and morbidity should be included as primary

outcome measures, as they are “arguably as important as speed and

avoidance of cesarean section.”

DR. NORMAN and DR. STOCK are

with the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health and the Queen's Medical

Research Center at the University of Edinburgh. Their comments were

taken from an editorial accompanying the article by Dr. Jozwiak and

colleagues (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61581-X]). Dr. Norman

reported receiving fees for acting as a consultant for Preglem and is

an unpaid member of an advisory board for Hologic. Dr. Stock had no

relevant financial disclosures.

Use of a Foley catheter for labor induction in women with an unfavorable cervix at term resulted in a similar cesarean section rate to use of prostaglandin E2 gel for labor induction, but with fewer maternal and neonatal side effects, according to findings from an open-label randomized controlled trial involving more than 800 women.

Cesarean section, most often done for failure to progress during the first stage of labor, was performed in 23% of 411 women induced using a Foley catheter, and in 20% of 408 women induced using vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (relative risk, 1.13), Dr. Marta Jozwiak of Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, the Netherlands, and her colleagues from the PROBAAT Study Group reported.

The frequency of vaginal instrumental deliveries was similar in the two groups as well (11% and 13% in the Foley catheter and prostaglandin E2 groups, respectively), the investigators said (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0]).

Two serious maternal adverse events occurred, both in the prostaglandin group. These included one uterine perforation after insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during oxytocin augmentation, they said, noting that both neonates were born in good clinical condition, but were admitted to the neonatal ward with suspected infection.

Four minor maternal adverse events occurred, including three allergic reactions (in one woman in the Foley catheter group and in two women in the prostaglandin E2 group), and blood loss on a second insertion of the catheter in one woman. Also, the rate of suspected intrapartum infection was significantly lower in the Foley catheter group (1% vs. 3%).

As for neonatal adverse events, the rate of admissions to the neonatal ward was significantly higher in the prostaglandin E2 group (12% vs. 20%), Dr. Jozwiak and her associates said.

Patients in the PROBAAT trial included women beyond 37 weeks' gestation with a singleton pregnancy in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix as defined by a Bishop score less than 6. The women were enrolled at 12 centers throughout the Netherlands between Feb. 10, 2009, and May 17, 2010, and all had an indication for labor induction, and had no prior cesarean sections.

The findings in regard to cesarean section rates when labor induction is performed using a Foley catheter vs. prostaglandin E2 were confirmed by a meta-analysis that included data from this study. The meta-analysis also demonstrated that Foley catheter induction was associated with reduced rates of hyperstimulation (odds ratio, 0.44) and postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 0.60), the investigators reported, noting that although the use of a Foley catheter for labor induction did not increase the vaginal delivery rate when compared with use of prostaglandin E2 as they had hypothesized, the findings nonetheless support the use of Foley catheters.

“After induction with a Foley catheter, the overall number of operative deliveries for suspected fetal distress was lower, fewer mothers were treated with intrapartum antibiotics, and significantly fewer neonates were admitted to the neonatal ward,” they said, adding: “We therefore think that a Foley catheter should be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

Also, in light of the low cost and easy storage of Foley catheters, their use could be suitable for developing countries and low-resource settings, Dr. Jozwiak and her associates noted.

Future studies should compare the use of Foley catheters with other prostaglandin preparations such as prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) which is becoming increasingly popular worldwide, and should evaluate the use of Foley catheters in women with a prior cesarean section, they suggested.

Use of a Foley catheter for labor induction in women with an unfavorable cervix at term resulted in a similar cesarean section rate to use of prostaglandin E2 gel for labor induction, but with fewer maternal and neonatal side effects, according to findings from an open-label randomized controlled trial involving more than 800 women.

Cesarean section, most often done for failure to progress during the first stage of labor, was performed in 23% of 411 women induced using a Foley catheter, and in 20% of 408 women induced using vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel (relative risk, 1.13), Dr. Marta Jozwiak of Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, the Netherlands, and her colleagues from the PROBAAT Study Group reported.

The frequency of vaginal instrumental deliveries was similar in the two groups as well (11% and 13% in the Foley catheter and prostaglandin E2 groups, respectively), the investigators said (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0]).

Two serious maternal adverse events occurred, both in the prostaglandin group. These included one uterine perforation after insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter and one uterine rupture during oxytocin augmentation, they said, noting that both neonates were born in good clinical condition, but were admitted to the neonatal ward with suspected infection.

Four minor maternal adverse events occurred, including three allergic reactions (in one woman in the Foley catheter group and in two women in the prostaglandin E2 group), and blood loss on a second insertion of the catheter in one woman. Also, the rate of suspected intrapartum infection was significantly lower in the Foley catheter group (1% vs. 3%).

As for neonatal adverse events, the rate of admissions to the neonatal ward was significantly higher in the prostaglandin E2 group (12% vs. 20%), Dr. Jozwiak and her associates said.

Patients in the PROBAAT trial included women beyond 37 weeks' gestation with a singleton pregnancy in cephalic presentation, with intact membranes and an unfavorable cervix as defined by a Bishop score less than 6. The women were enrolled at 12 centers throughout the Netherlands between Feb. 10, 2009, and May 17, 2010, and all had an indication for labor induction, and had no prior cesarean sections.

The findings in regard to cesarean section rates when labor induction is performed using a Foley catheter vs. prostaglandin E2 were confirmed by a meta-analysis that included data from this study. The meta-analysis also demonstrated that Foley catheter induction was associated with reduced rates of hyperstimulation (odds ratio, 0.44) and postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 0.60), the investigators reported, noting that although the use of a Foley catheter for labor induction did not increase the vaginal delivery rate when compared with use of prostaglandin E2 as they had hypothesized, the findings nonetheless support the use of Foley catheters.

“After induction with a Foley catheter, the overall number of operative deliveries for suspected fetal distress was lower, fewer mothers were treated with intrapartum antibiotics, and significantly fewer neonates were admitted to the neonatal ward,” they said, adding: “We therefore think that a Foley catheter should be considered for induction of labor in women with an unfavorable cervix at term.”

Also, in light of the low cost and easy storage of Foley catheters, their use could be suitable for developing countries and low-resource settings, Dr. Jozwiak and her associates noted.

Future studies should compare the use of Foley catheters with other prostaglandin preparations such as prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) which is becoming increasingly popular worldwide, and should evaluate the use of Foley catheters in women with a prior cesarean section, they suggested.

From the Lancet

Fibroids Foretell Worse Maternal and Fetal Outcomes

ORLANDO – Uterine fibroids are bad for pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, and a new study shows just how bad.

Women diagnosed with fibroids on their first obstetric ultrasound examination, for example, were significantly more likely to experience preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of the membranes (pPROM). Also, significantly more deliver before 37 weeks' gestation or via cesarean section, compared with a group of women without these noncancerous growths of the uterus.

Dr. Radwan Asaad and his colleagues compared 152 women with fibroids to another 165 matched controls in a retrospective cohort analysis conducted at Wayne State University, Detroit. They also found fibroids weren't good news for the baby either.

“Uterine fibroids complicate the pregnancy course as evidenced by a considerable impact on the obstetrical and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Asaad said at the meeting.

In terms of the significantly different maternal numbers, women with fibroids were more likely to experience preterm labor (16.4% vs. 2.4% of controls), and pPROM (15.8% vs. 3.6%), and to deliver preterm (33.3% vs. 10.1%).

Fetal malpresentation also was significantly more likely in the fibroid group (22% vs. 6% in controls). Cesarean delivery occurred in 54.3% of the fibroid group vs. 28.0% of the control group, another significant difference.

Gestational age at delivery was significantly less when the mother had fibroids (mean 35.3 weeks) vs. without (38.6 weeks).

Children born to women in the fibroid group had a mean birth weight of 2,634 g, compared with 3,181 g for those born to control group women. Apgar scores at 1 minute were a mean 6.7 vs. 7.8 in the control group and at 5 minutes were a mean 7.9 vs. 8.8.

Pregnancy loss was higher in the fibroid group during the first trimester (7.9% vs. 3.6% in controls) and during the second trimester (5.9% vs. 1.2%), but these differences were not statistically significant to the P less than .001 level. A trend toward more arrested dilation in the fibroid group likewise did not reach significance.

“Uterine myomas are the most common pelvic tumor in reproductive-age women,” said Dr. Asaad, a laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgeon in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Hutzel Women's Hospital and Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center. Prevalence in published studies varies from 2% to 11%, depending on the trimester in which they are measured and the size threshold chosen by researchers.

A meeting attendee asked for information on the size and anatomic location of the fibroids. Dr. Asaad replied that he was only able to categorize women dichotomously as yes/no for presence of fibroids in this retrospective study.

Dr. Asaad and his associates reviewed all department ultrasounds from 1998 to 2006 at their tertiary care center. Women with complete records in the fibroid group were matched to controls for age, gravidity, parity, and year of delivery.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Uterine fibroids are bad for pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, and a new study shows just how bad.

Women diagnosed with fibroids on their first obstetric ultrasound examination, for example, were significantly more likely to experience preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of the membranes (pPROM). Also, significantly more deliver before 37 weeks' gestation or via cesarean section, compared with a group of women without these noncancerous growths of the uterus.

Dr. Radwan Asaad and his colleagues compared 152 women with fibroids to another 165 matched controls in a retrospective cohort analysis conducted at Wayne State University, Detroit. They also found fibroids weren't good news for the baby either.

“Uterine fibroids complicate the pregnancy course as evidenced by a considerable impact on the obstetrical and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Asaad said at the meeting.

In terms of the significantly different maternal numbers, women with fibroids were more likely to experience preterm labor (16.4% vs. 2.4% of controls), and pPROM (15.8% vs. 3.6%), and to deliver preterm (33.3% vs. 10.1%).

Fetal malpresentation also was significantly more likely in the fibroid group (22% vs. 6% in controls). Cesarean delivery occurred in 54.3% of the fibroid group vs. 28.0% of the control group, another significant difference.

Gestational age at delivery was significantly less when the mother had fibroids (mean 35.3 weeks) vs. without (38.6 weeks).

Children born to women in the fibroid group had a mean birth weight of 2,634 g, compared with 3,181 g for those born to control group women. Apgar scores at 1 minute were a mean 6.7 vs. 7.8 in the control group and at 5 minutes were a mean 7.9 vs. 8.8.

Pregnancy loss was higher in the fibroid group during the first trimester (7.9% vs. 3.6% in controls) and during the second trimester (5.9% vs. 1.2%), but these differences were not statistically significant to the P less than .001 level. A trend toward more arrested dilation in the fibroid group likewise did not reach significance.

“Uterine myomas are the most common pelvic tumor in reproductive-age women,” said Dr. Asaad, a laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgeon in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Hutzel Women's Hospital and Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center. Prevalence in published studies varies from 2% to 11%, depending on the trimester in which they are measured and the size threshold chosen by researchers.

A meeting attendee asked for information on the size and anatomic location of the fibroids. Dr. Asaad replied that he was only able to categorize women dichotomously as yes/no for presence of fibroids in this retrospective study.

Dr. Asaad and his associates reviewed all department ultrasounds from 1998 to 2006 at their tertiary care center. Women with complete records in the fibroid group were matched to controls for age, gravidity, parity, and year of delivery.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Uterine fibroids are bad for pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, and a new study shows just how bad.

Women diagnosed with fibroids on their first obstetric ultrasound examination, for example, were significantly more likely to experience preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of the membranes (pPROM). Also, significantly more deliver before 37 weeks' gestation or via cesarean section, compared with a group of women without these noncancerous growths of the uterus.

Dr. Radwan Asaad and his colleagues compared 152 women with fibroids to another 165 matched controls in a retrospective cohort analysis conducted at Wayne State University, Detroit. They also found fibroids weren't good news for the baby either.

“Uterine fibroids complicate the pregnancy course as evidenced by a considerable impact on the obstetrical and neonatal outcomes,” Dr. Asaad said at the meeting.

In terms of the significantly different maternal numbers, women with fibroids were more likely to experience preterm labor (16.4% vs. 2.4% of controls), and pPROM (15.8% vs. 3.6%), and to deliver preterm (33.3% vs. 10.1%).