User login

Difficult fetal extraction at cesarean delivery: What should you do?

Do you have a clinical pearl for delivering a deflexed, deeply impacted fetal head at cesarean delivery?

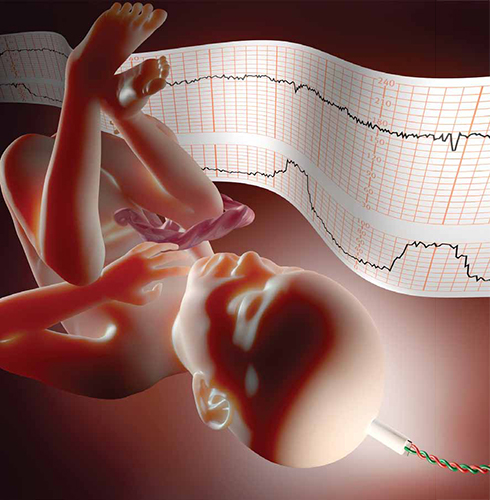

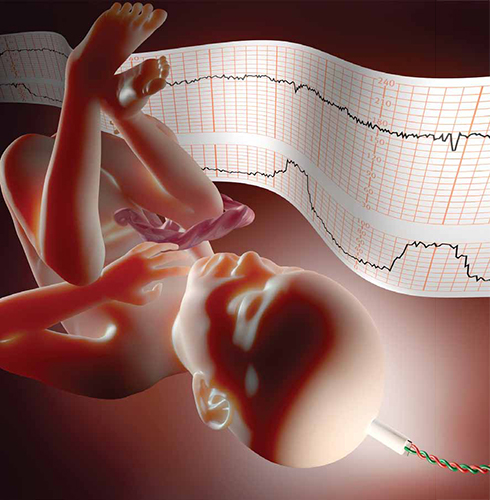

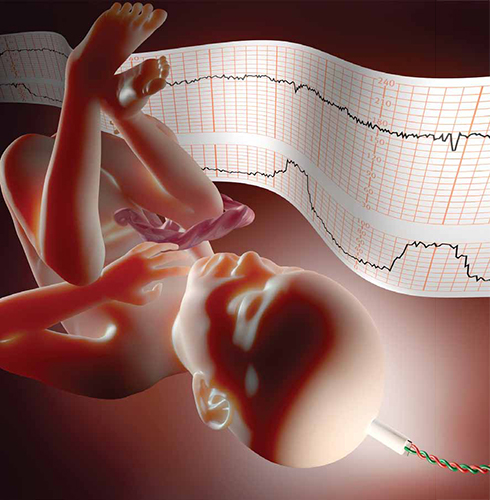

CASE At 2 Am, the director of nursing pages you, asking you to attend to a 26-year-old gravida 1 para 0 who has just been brought by ambulance to labor and delivery after attempting home birth.

The midwife caring for the patient reports that she has been fully dilated for 7 hours and has been pushing for 4 hours. You confirm that the patient is fully dilated, with the presenting part at +1 station; significant caput succedaneum; and molding of the fetal head.

Estimated fetal weight is 3,600 g. The fetal heart-rate tracing is Category II.

You recommend a cesarean delivery. The exhausted patient agrees, reluctantly.

But when you attempt to deliver the fetal head, you realize that it is deflexed and stuck deep in the pelvis. It’s going to be very difficult to deliver the head without trauma to the lower uterine segment, upper vagina and, possibly, the bladder.

What should you do now?

Experienced clinicians often recognize, instinctively, a looming catastrophe before it happens because we have seen a similar situation earlier in our career.1 After we identify the potential for trouble, we attempt to avert disaster by taking preventive action.

One very good occasion to use that “clinical sixth sense”

Consider the situation in which labor has been complicated by a long second stage, with a large fetus—a disaster waiting to happen. In such a case, cesarean delivery, if it is necessary, can be difficult to perform because the fetal head is stuck deep in the pelvis. Attempting to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, using standard delivery maneuvers, may cause extensive trauma to the lower uterine segment, vagina, and bladder, and fetal injury. In turn, ureteral injury or postpartum hemorrhage may occur during your repair of damage to the lower uterine segment, vagina, or bladder.

In the scenario described a moment ago, the fact that the patient was in the second stage of labor for 7 hours, at home, without anesthesia, and with failure to progress to vaginal delivery increases the likelihood that the fetal head is impacted deep in the pelvis. Before you perform cesarean delivery, you might find it helpful to perform a vaginal examination to answer two questions:

- On vaginal examination, between contractions, can the fetal head be gently moved out of the pelvis? Or is it deeply impacted?

- Is there sufficient space between the fetal head and symphysis pubis to permit delivery with standard cesarean maneuvers?

If the head is impacted deep in the pelvis, I encourage you to consider alternative approaches to cesarean delivery, including reverse breech extraction (FIGURE 1) or an assist from a vaginal hand (FIGURE 2) to facilitate delivery.

FIGURE 1 Reverse breech extraction—the “pull technique”

Once the uterus has been opened, reach immediately into the upper segment for a fetal leg. Apply gentle traction on the leg until the other leg appears. With two legs held together, deliver (pull) the body of the fetus out of the uterus.

The “pull technique”: Reverse breech extraction

One randomized trial and one retrospective study have evaluated the use of reverse breech extraction (the pull technique) in comparison to pushing up with a vaginal hand from below (the push technique) for managing a difficult cesarean delivery after obstructed labor.

Results of a clinical trial. 108 Nigerian women who had obstructed labor were randomly assigned to a pull technique (reverse breech extraction) or a push technique (assist from a vaginal hand).2

The push technique in this study was reportedly performed with a “finger” in the vagina pushing up on the fetal head while the surgeon attempted to deliver the head in a standard fashion.

The pull technique was performed by opening the uterus, immediately reaching into the upper uterus for a fetal leg, and applying gentle traction on the leg until the second leg appeared. Then, with two legs held together, the body of the fetus was delivered (pulled) out of the uterus. The delivery was then completed using a technique similar to that used for a breech delivery. Standard breech delivery maneuvers were used to assist with the delivery of the fetal shoulders and fetal head.

Comparing the push technique with the pull technique, the push technique was associated with longer operative time (89 minutes compared with 56 minutes [p <.001]); greater blood loss (1,257 mL and 899 mL [p <.001]); and more extensions involving the uterus (30% and 11% [p <.05]) and vagina (17% and 4% [p <.05]) that required surgical repair. The rate of fetal injury was similar using either technique: 6% (push) and 7% (pull).

Results of a retrospective review. A study of 48 difficult cesarean deliveries reported that the push technique resulted in a higher rate of extensions of the uterine incision (50%) than the pull technique (15%).3

A third retrospective study is relevant. Investigators compared reverse breech extraction and standard direct delivery of the impacted fetal head, without assistance from a vaginal hand. In 182 laboring women in whom the fetal head was deeply impacted, reverse breech extraction was associated with a lower rate of extension of the uterine incision (2%) than the conventional approach of direct delivery of the impacted fetal head (23%).4

My recommendation. When you intend to use a reverse breech delivery technique to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, I recommend a low vertical uterine incision so that you are able to extend the incision superiorly in case there is difficulty delivering the breech. Many clinicians report, however, that it is relatively easy to perform a reverse breech extraction through a transverse uterine incision.5 If you have made a transverse hysterotomy incision and it becomes difficult to deliver the breech, consider making a J or T incision in the uterus to provide additional room to deliver the breech.

FIGURE 2 Assist from a vaginal hand: The “push technique”

When pushing the head up from the vagina, try to flex the fetal head. If possible, use three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

The “push technique”: An assist from a vaginal hand

Using a hand in the vagina to push the head up toward the uterine incision can be performed by an assistant or the primary surgeon.6 If the need for assistance with a hand from below is recognized before the cesarean is undertaken, the mother’s legs can be placed in a supine frog-leg or modified lithotomy position.7

The assistant pushing the head up from the vagina should try to flex the fetal head. If possible, three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—should be used to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

Caution: Using only one or two fingers for this technique, with the pushing focused on one small area of the head, may increase the risk of fetal skull fracture.

Using the obstetrical spoon

Some clinicians who routinely use a Coyne spoon to deliver the fetal head at the time of cesarean delivery prefer to use the spoon to deliver the deeply impacted fetal head. Using two fingers (not the entire hand), the spoon is gently placed through the uterine incision to a position below the fetal head. The spoon is then used to help release and elevate the head from the pelvis, and the fetus is delivered in the usual manner with the spoon.

Caution: After an excessively prolonged labor, it may be difficult to place the spoon below the fetal head without damaging the lower uterine segment.

Other techniques to consider

When a transverse uterine incision is performed after prolonged labor, a fetal shoulder often appears in the hysterotomy as soon as the incision is made. This so-called shoulder sign is another indication that the fetal head is deeply impacted. Clinicians have reported that it can be helpful to have an assistant gently push the shoulder cephalad, while the surgeon attempts the direct extraction of the fetal head in the classical manner.

A more formal method of using the shoulder that presents in the hysterotomy incision to facilitate delivery has been reported8:

- The shoulder presenting in the hysterotomy is delivered

- The opposite shoulder is delivered

- The fetal body is delivered

- The fetal head is delivered last.

There are risks and consequences to extending the second stage

Trends in OB practice have resulted in more instances of labor in which the second stage extends past 3 hours. Prolonged labor markedly increases the likelihood that an obstetrician will encounter cases in which the fetal head is deflexed and deeply impacted in the pelvis, making extraction of the fetal head very difficult. Prolonged labor also increases the likelihood that the lower uterine segment and upper vagina will be edematous and very thin, increasing the likelihood of trauma to these, and adjacent, organs.

One approach to reduce the risk of difficult fetal extraction is to limit the second stage of labor to 3 hours or less in most situations. If you are asked to perform a cesarean delivery on a patient whose provider has allowed the second stage to extend well beyond 3 hours, be prepared to perform a reverse breech extraction!

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- What can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

1. Stuebe AM. Level IV evidence—adverse anecdote and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):8-9.

2. Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji O, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375-378.

3. Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;121(1):24-26.

4. Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan. 2009;88(10):1163-1166.

5. Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183-184.

6. Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the mid cavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59-60.

7. Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707-710.

8. Khosla AH, Dahiya K, Sangwan K. Cesarean section in a wedged head. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:187-191.

Do you have a clinical pearl for delivering a deflexed, deeply impacted fetal head at cesarean delivery?

CASE At 2 Am, the director of nursing pages you, asking you to attend to a 26-year-old gravida 1 para 0 who has just been brought by ambulance to labor and delivery after attempting home birth.

The midwife caring for the patient reports that she has been fully dilated for 7 hours and has been pushing for 4 hours. You confirm that the patient is fully dilated, with the presenting part at +1 station; significant caput succedaneum; and molding of the fetal head.

Estimated fetal weight is 3,600 g. The fetal heart-rate tracing is Category II.

You recommend a cesarean delivery. The exhausted patient agrees, reluctantly.

But when you attempt to deliver the fetal head, you realize that it is deflexed and stuck deep in the pelvis. It’s going to be very difficult to deliver the head without trauma to the lower uterine segment, upper vagina and, possibly, the bladder.

What should you do now?

Experienced clinicians often recognize, instinctively, a looming catastrophe before it happens because we have seen a similar situation earlier in our career.1 After we identify the potential for trouble, we attempt to avert disaster by taking preventive action.

One very good occasion to use that “clinical sixth sense”

Consider the situation in which labor has been complicated by a long second stage, with a large fetus—a disaster waiting to happen. In such a case, cesarean delivery, if it is necessary, can be difficult to perform because the fetal head is stuck deep in the pelvis. Attempting to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, using standard delivery maneuvers, may cause extensive trauma to the lower uterine segment, vagina, and bladder, and fetal injury. In turn, ureteral injury or postpartum hemorrhage may occur during your repair of damage to the lower uterine segment, vagina, or bladder.

In the scenario described a moment ago, the fact that the patient was in the second stage of labor for 7 hours, at home, without anesthesia, and with failure to progress to vaginal delivery increases the likelihood that the fetal head is impacted deep in the pelvis. Before you perform cesarean delivery, you might find it helpful to perform a vaginal examination to answer two questions:

- On vaginal examination, between contractions, can the fetal head be gently moved out of the pelvis? Or is it deeply impacted?

- Is there sufficient space between the fetal head and symphysis pubis to permit delivery with standard cesarean maneuvers?

If the head is impacted deep in the pelvis, I encourage you to consider alternative approaches to cesarean delivery, including reverse breech extraction (FIGURE 1) or an assist from a vaginal hand (FIGURE 2) to facilitate delivery.

FIGURE 1 Reverse breech extraction—the “pull technique”

Once the uterus has been opened, reach immediately into the upper segment for a fetal leg. Apply gentle traction on the leg until the other leg appears. With two legs held together, deliver (pull) the body of the fetus out of the uterus.

The “pull technique”: Reverse breech extraction

One randomized trial and one retrospective study have evaluated the use of reverse breech extraction (the pull technique) in comparison to pushing up with a vaginal hand from below (the push technique) for managing a difficult cesarean delivery after obstructed labor.

Results of a clinical trial. 108 Nigerian women who had obstructed labor were randomly assigned to a pull technique (reverse breech extraction) or a push technique (assist from a vaginal hand).2

The push technique in this study was reportedly performed with a “finger” in the vagina pushing up on the fetal head while the surgeon attempted to deliver the head in a standard fashion.

The pull technique was performed by opening the uterus, immediately reaching into the upper uterus for a fetal leg, and applying gentle traction on the leg until the second leg appeared. Then, with two legs held together, the body of the fetus was delivered (pulled) out of the uterus. The delivery was then completed using a technique similar to that used for a breech delivery. Standard breech delivery maneuvers were used to assist with the delivery of the fetal shoulders and fetal head.

Comparing the push technique with the pull technique, the push technique was associated with longer operative time (89 minutes compared with 56 minutes [p <.001]); greater blood loss (1,257 mL and 899 mL [p <.001]); and more extensions involving the uterus (30% and 11% [p <.05]) and vagina (17% and 4% [p <.05]) that required surgical repair. The rate of fetal injury was similar using either technique: 6% (push) and 7% (pull).

Results of a retrospective review. A study of 48 difficult cesarean deliveries reported that the push technique resulted in a higher rate of extensions of the uterine incision (50%) than the pull technique (15%).3

A third retrospective study is relevant. Investigators compared reverse breech extraction and standard direct delivery of the impacted fetal head, without assistance from a vaginal hand. In 182 laboring women in whom the fetal head was deeply impacted, reverse breech extraction was associated with a lower rate of extension of the uterine incision (2%) than the conventional approach of direct delivery of the impacted fetal head (23%).4

My recommendation. When you intend to use a reverse breech delivery technique to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, I recommend a low vertical uterine incision so that you are able to extend the incision superiorly in case there is difficulty delivering the breech. Many clinicians report, however, that it is relatively easy to perform a reverse breech extraction through a transverse uterine incision.5 If you have made a transverse hysterotomy incision and it becomes difficult to deliver the breech, consider making a J or T incision in the uterus to provide additional room to deliver the breech.

FIGURE 2 Assist from a vaginal hand: The “push technique”

When pushing the head up from the vagina, try to flex the fetal head. If possible, use three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

The “push technique”: An assist from a vaginal hand

Using a hand in the vagina to push the head up toward the uterine incision can be performed by an assistant or the primary surgeon.6 If the need for assistance with a hand from below is recognized before the cesarean is undertaken, the mother’s legs can be placed in a supine frog-leg or modified lithotomy position.7

The assistant pushing the head up from the vagina should try to flex the fetal head. If possible, three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—should be used to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

Caution: Using only one or two fingers for this technique, with the pushing focused on one small area of the head, may increase the risk of fetal skull fracture.

Using the obstetrical spoon

Some clinicians who routinely use a Coyne spoon to deliver the fetal head at the time of cesarean delivery prefer to use the spoon to deliver the deeply impacted fetal head. Using two fingers (not the entire hand), the spoon is gently placed through the uterine incision to a position below the fetal head. The spoon is then used to help release and elevate the head from the pelvis, and the fetus is delivered in the usual manner with the spoon.

Caution: After an excessively prolonged labor, it may be difficult to place the spoon below the fetal head without damaging the lower uterine segment.

Other techniques to consider

When a transverse uterine incision is performed after prolonged labor, a fetal shoulder often appears in the hysterotomy as soon as the incision is made. This so-called shoulder sign is another indication that the fetal head is deeply impacted. Clinicians have reported that it can be helpful to have an assistant gently push the shoulder cephalad, while the surgeon attempts the direct extraction of the fetal head in the classical manner.

A more formal method of using the shoulder that presents in the hysterotomy incision to facilitate delivery has been reported8:

- The shoulder presenting in the hysterotomy is delivered

- The opposite shoulder is delivered

- The fetal body is delivered

- The fetal head is delivered last.

There are risks and consequences to extending the second stage

Trends in OB practice have resulted in more instances of labor in which the second stage extends past 3 hours. Prolonged labor markedly increases the likelihood that an obstetrician will encounter cases in which the fetal head is deflexed and deeply impacted in the pelvis, making extraction of the fetal head very difficult. Prolonged labor also increases the likelihood that the lower uterine segment and upper vagina will be edematous and very thin, increasing the likelihood of trauma to these, and adjacent, organs.

One approach to reduce the risk of difficult fetal extraction is to limit the second stage of labor to 3 hours or less in most situations. If you are asked to perform a cesarean delivery on a patient whose provider has allowed the second stage to extend well beyond 3 hours, be prepared to perform a reverse breech extraction!

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- What can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

Do you have a clinical pearl for delivering a deflexed, deeply impacted fetal head at cesarean delivery?

CASE At 2 Am, the director of nursing pages you, asking you to attend to a 26-year-old gravida 1 para 0 who has just been brought by ambulance to labor and delivery after attempting home birth.

The midwife caring for the patient reports that she has been fully dilated for 7 hours and has been pushing for 4 hours. You confirm that the patient is fully dilated, with the presenting part at +1 station; significant caput succedaneum; and molding of the fetal head.

Estimated fetal weight is 3,600 g. The fetal heart-rate tracing is Category II.

You recommend a cesarean delivery. The exhausted patient agrees, reluctantly.

But when you attempt to deliver the fetal head, you realize that it is deflexed and stuck deep in the pelvis. It’s going to be very difficult to deliver the head without trauma to the lower uterine segment, upper vagina and, possibly, the bladder.

What should you do now?

Experienced clinicians often recognize, instinctively, a looming catastrophe before it happens because we have seen a similar situation earlier in our career.1 After we identify the potential for trouble, we attempt to avert disaster by taking preventive action.

One very good occasion to use that “clinical sixth sense”

Consider the situation in which labor has been complicated by a long second stage, with a large fetus—a disaster waiting to happen. In such a case, cesarean delivery, if it is necessary, can be difficult to perform because the fetal head is stuck deep in the pelvis. Attempting to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, using standard delivery maneuvers, may cause extensive trauma to the lower uterine segment, vagina, and bladder, and fetal injury. In turn, ureteral injury or postpartum hemorrhage may occur during your repair of damage to the lower uterine segment, vagina, or bladder.

In the scenario described a moment ago, the fact that the patient was in the second stage of labor for 7 hours, at home, without anesthesia, and with failure to progress to vaginal delivery increases the likelihood that the fetal head is impacted deep in the pelvis. Before you perform cesarean delivery, you might find it helpful to perform a vaginal examination to answer two questions:

- On vaginal examination, between contractions, can the fetal head be gently moved out of the pelvis? Or is it deeply impacted?

- Is there sufficient space between the fetal head and symphysis pubis to permit delivery with standard cesarean maneuvers?

If the head is impacted deep in the pelvis, I encourage you to consider alternative approaches to cesarean delivery, including reverse breech extraction (FIGURE 1) or an assist from a vaginal hand (FIGURE 2) to facilitate delivery.

FIGURE 1 Reverse breech extraction—the “pull technique”

Once the uterus has been opened, reach immediately into the upper segment for a fetal leg. Apply gentle traction on the leg until the other leg appears. With two legs held together, deliver (pull) the body of the fetus out of the uterus.

The “pull technique”: Reverse breech extraction

One randomized trial and one retrospective study have evaluated the use of reverse breech extraction (the pull technique) in comparison to pushing up with a vaginal hand from below (the push technique) for managing a difficult cesarean delivery after obstructed labor.

Results of a clinical trial. 108 Nigerian women who had obstructed labor were randomly assigned to a pull technique (reverse breech extraction) or a push technique (assist from a vaginal hand).2

The push technique in this study was reportedly performed with a “finger” in the vagina pushing up on the fetal head while the surgeon attempted to deliver the head in a standard fashion.

The pull technique was performed by opening the uterus, immediately reaching into the upper uterus for a fetal leg, and applying gentle traction on the leg until the second leg appeared. Then, with two legs held together, the body of the fetus was delivered (pulled) out of the uterus. The delivery was then completed using a technique similar to that used for a breech delivery. Standard breech delivery maneuvers were used to assist with the delivery of the fetal shoulders and fetal head.

Comparing the push technique with the pull technique, the push technique was associated with longer operative time (89 minutes compared with 56 minutes [p <.001]); greater blood loss (1,257 mL and 899 mL [p <.001]); and more extensions involving the uterus (30% and 11% [p <.05]) and vagina (17% and 4% [p <.05]) that required surgical repair. The rate of fetal injury was similar using either technique: 6% (push) and 7% (pull).

Results of a retrospective review. A study of 48 difficult cesarean deliveries reported that the push technique resulted in a higher rate of extensions of the uterine incision (50%) than the pull technique (15%).3

A third retrospective study is relevant. Investigators compared reverse breech extraction and standard direct delivery of the impacted fetal head, without assistance from a vaginal hand. In 182 laboring women in whom the fetal head was deeply impacted, reverse breech extraction was associated with a lower rate of extension of the uterine incision (2%) than the conventional approach of direct delivery of the impacted fetal head (23%).4

My recommendation. When you intend to use a reverse breech delivery technique to deliver a deeply impacted fetal head, I recommend a low vertical uterine incision so that you are able to extend the incision superiorly in case there is difficulty delivering the breech. Many clinicians report, however, that it is relatively easy to perform a reverse breech extraction through a transverse uterine incision.5 If you have made a transverse hysterotomy incision and it becomes difficult to deliver the breech, consider making a J or T incision in the uterus to provide additional room to deliver the breech.

FIGURE 2 Assist from a vaginal hand: The “push technique”

When pushing the head up from the vagina, try to flex the fetal head. If possible, use three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

The “push technique”: An assist from a vaginal hand

Using a hand in the vagina to push the head up toward the uterine incision can be performed by an assistant or the primary surgeon.6 If the need for assistance with a hand from below is recognized before the cesarean is undertaken, the mother’s legs can be placed in a supine frog-leg or modified lithotomy position.7

The assistant pushing the head up from the vagina should try to flex the fetal head. If possible, three or four fingers—or a cupped hand or the palm of the hand—should be used to apply force spread widely across the presenting part.

Caution: Using only one or two fingers for this technique, with the pushing focused on one small area of the head, may increase the risk of fetal skull fracture.

Using the obstetrical spoon

Some clinicians who routinely use a Coyne spoon to deliver the fetal head at the time of cesarean delivery prefer to use the spoon to deliver the deeply impacted fetal head. Using two fingers (not the entire hand), the spoon is gently placed through the uterine incision to a position below the fetal head. The spoon is then used to help release and elevate the head from the pelvis, and the fetus is delivered in the usual manner with the spoon.

Caution: After an excessively prolonged labor, it may be difficult to place the spoon below the fetal head without damaging the lower uterine segment.

Other techniques to consider

When a transverse uterine incision is performed after prolonged labor, a fetal shoulder often appears in the hysterotomy as soon as the incision is made. This so-called shoulder sign is another indication that the fetal head is deeply impacted. Clinicians have reported that it can be helpful to have an assistant gently push the shoulder cephalad, while the surgeon attempts the direct extraction of the fetal head in the classical manner.

A more formal method of using the shoulder that presents in the hysterotomy incision to facilitate delivery has been reported8:

- The shoulder presenting in the hysterotomy is delivered

- The opposite shoulder is delivered

- The fetal body is delivered

- The fetal head is delivered last.

There are risks and consequences to extending the second stage

Trends in OB practice have resulted in more instances of labor in which the second stage extends past 3 hours. Prolonged labor markedly increases the likelihood that an obstetrician will encounter cases in which the fetal head is deflexed and deeply impacted in the pelvis, making extraction of the fetal head very difficult. Prolonged labor also increases the likelihood that the lower uterine segment and upper vagina will be edematous and very thin, increasing the likelihood of trauma to these, and adjacent, organs.

One approach to reduce the risk of difficult fetal extraction is to limit the second stage of labor to 3 hours or less in most situations. If you are asked to perform a cesarean delivery on a patient whose provider has allowed the second stage to extend well beyond 3 hours, be prepared to perform a reverse breech extraction!

in his memorable 2011 Editorials

- Consider denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis (January)

- What can “meaningful use” of an EHR mean for your bottom line? (February)

- Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other? (March)

- Stop staring at that Category-II fetal heart-rate tracing … (April)

- Big step forward and downward: An OC with 10 μg of estrogen (May)

- OB and neonatal medicine practices are evolving—in ways that might surprise you (June)

- Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? (July)

- Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum (September)

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander (October)

- Insomnia is a troubling and under-treated problem (November)

- How to repair bladder injury at the time of cesarean delivery (December)

1. Stuebe AM. Level IV evidence—adverse anecdote and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):8-9.

2. Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji O, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375-378.

3. Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;121(1):24-26.

4. Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan. 2009;88(10):1163-1166.

5. Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183-184.

6. Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the mid cavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59-60.

7. Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707-710.

8. Khosla AH, Dahiya K, Sangwan K. Cesarean section in a wedged head. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:187-191.

1. Stuebe AM. Level IV evidence—adverse anecdote and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):8-9.

2. Fasubaa OB, Ezechi OC, Orji O, et al. Delivery of the impacted head of the fetus at caesarean section after prolonged obstructed labour: a randomised comparative study of two methods. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(4):375-378.

3. Levy R, Chernomoretz T, Appelman Z, Levin D, Or Y, Hagay ZJ. Head pushing versus reverse breech extraction in cases of impacted fetal head during Cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;121(1):24-26.

4. Chopra S, Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Jain V, Kalra J, Suri V. Disengagement of the deeply engaged fetal head during cesarean section in advanced labor: conventional method versus reverse breech extraction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan. 2009;88(10):1163-1166.

5. Fong YF, Arulkumaran S. Breech extraction—an alternative method of delivering a deeply engaged head at cesarean section. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;56(2):183-184.

6. Lippert TH. Bimanual delivery of the fetal head at cesarean section with the fetal head in the mid cavity. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234(1):59-60.

7. Landesman R, Graber EA. Abdominovaginal delivery: modification of the cesarean section operation to facilitate delivery of the impacted head. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(6):707-710.

8. Khosla AH, Dahiya K, Sangwan K. Cesarean section in a wedged head. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:187-191.

Overweight and Obese Women Deliver Fewer IVF Live Births

ORLANDO – Obesity significantly lowers a woman's chance of delivering a live birth after in vitro fertilization, according to a retrospective study of more than 4,500 women.

Up to a 68% lower chance for a live birth was the major finding when researchers compared overweight and obese women to those with a normal body mass index (BMI). Women with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m

The live birth rate declined as BMI increased, Dr. Stephanie Jones said. Compared with women with a normal BMI (18.50-24.99), the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for a live birth was 0.96 among overweight women (25-29.99); 0.63 for obesity class I (30-34.99); 0.39 for obesity class II (35-39.99); and 0.32 for those in obesity class III (BMI of 40 kg/m

The clinical message is to counsel patients that even “a modest amount of weight loss might improve IVF success rates,” Dr. Jones said at the meeting.

Dr. Jones and her associates examined outcomes after the first, fresh, autologous procedure for 4,609 women treated at Boston IVF in Brookline, Mass. from 2006 to 2010. Patients were aged 20-45 years.

A secondary outcome, the likelihood of implantation, was significantly different by BMI, compared with those with a normal BMI. Chances dropped for underweight women (BMI less than 18 kg/m

The likelihood of clinical pregnancy dropped only slightly for underweight women (adjusted OR, 0.98). However, it decreased significantly for overweight women (0.90) and for women in obesity class I (0.70), class II (0.41), and class III (0.43).

Interestingly, the miscarriage rate did not differ significantly according to maternal BMI, said Dr. Jones, a third-year resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

The normal-weight reference group included 2,605 patients with a BMI of 18.5-24.99 kg/m

In addition to its large sample size, the single institution design of the study is an advantage, Dr. Jones said. Previous researchers reported an association between increasing obesity and lower IVF success, but most of these studies were small, unadjusted, and focused on pregnancy rates.

“The live birth rate is the outcome most significant to our patients,” she said.

A systematic literature review found a decreased chance of IVF pregnancy (OR, 0.71) for overweight or obese women compared with normal weight women (Hum. Reprod. Update 2007;13:433-44). “But they only compared women in two groups – those with a BMI of 25 or less versus 25 plus,” Dr. Jones said.

In another study reported at the 2009 ASRM meeting, researchers found a lower clinical pregnancy rate and lower birth weights as maternal BMI increased (Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:245-52). This report was multicenter “and they did not necessarily control for differences in provider factors,” she said.

Dr. Jones and her associates also controlled for multiple potential confounders, including maternal age, paternal age, baseline follicle stimulating hormone levels, duration of stimulation, mean daily gonadotropin dose, peak estradiol, number of oocytes retrieved, use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection, embryo quality and number, transfer day, and number of embryos transferred.

ORLANDO – Obesity significantly lowers a woman's chance of delivering a live birth after in vitro fertilization, according to a retrospective study of more than 4,500 women.

Up to a 68% lower chance for a live birth was the major finding when researchers compared overweight and obese women to those with a normal body mass index (BMI). Women with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m

The live birth rate declined as BMI increased, Dr. Stephanie Jones said. Compared with women with a normal BMI (18.50-24.99), the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for a live birth was 0.96 among overweight women (25-29.99); 0.63 for obesity class I (30-34.99); 0.39 for obesity class II (35-39.99); and 0.32 for those in obesity class III (BMI of 40 kg/m

The clinical message is to counsel patients that even “a modest amount of weight loss might improve IVF success rates,” Dr. Jones said at the meeting.

Dr. Jones and her associates examined outcomes after the first, fresh, autologous procedure for 4,609 women treated at Boston IVF in Brookline, Mass. from 2006 to 2010. Patients were aged 20-45 years.

A secondary outcome, the likelihood of implantation, was significantly different by BMI, compared with those with a normal BMI. Chances dropped for underweight women (BMI less than 18 kg/m

The likelihood of clinical pregnancy dropped only slightly for underweight women (adjusted OR, 0.98). However, it decreased significantly for overweight women (0.90) and for women in obesity class I (0.70), class II (0.41), and class III (0.43).

Interestingly, the miscarriage rate did not differ significantly according to maternal BMI, said Dr. Jones, a third-year resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

The normal-weight reference group included 2,605 patients with a BMI of 18.5-24.99 kg/m

In addition to its large sample size, the single institution design of the study is an advantage, Dr. Jones said. Previous researchers reported an association between increasing obesity and lower IVF success, but most of these studies were small, unadjusted, and focused on pregnancy rates.

“The live birth rate is the outcome most significant to our patients,” she said.

A systematic literature review found a decreased chance of IVF pregnancy (OR, 0.71) for overweight or obese women compared with normal weight women (Hum. Reprod. Update 2007;13:433-44). “But they only compared women in two groups – those with a BMI of 25 or less versus 25 plus,” Dr. Jones said.

In another study reported at the 2009 ASRM meeting, researchers found a lower clinical pregnancy rate and lower birth weights as maternal BMI increased (Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:245-52). This report was multicenter “and they did not necessarily control for differences in provider factors,” she said.

Dr. Jones and her associates also controlled for multiple potential confounders, including maternal age, paternal age, baseline follicle stimulating hormone levels, duration of stimulation, mean daily gonadotropin dose, peak estradiol, number of oocytes retrieved, use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection, embryo quality and number, transfer day, and number of embryos transferred.

ORLANDO – Obesity significantly lowers a woman's chance of delivering a live birth after in vitro fertilization, according to a retrospective study of more than 4,500 women.

Up to a 68% lower chance for a live birth was the major finding when researchers compared overweight and obese women to those with a normal body mass index (BMI). Women with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m

The live birth rate declined as BMI increased, Dr. Stephanie Jones said. Compared with women with a normal BMI (18.50-24.99), the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for a live birth was 0.96 among overweight women (25-29.99); 0.63 for obesity class I (30-34.99); 0.39 for obesity class II (35-39.99); and 0.32 for those in obesity class III (BMI of 40 kg/m

The clinical message is to counsel patients that even “a modest amount of weight loss might improve IVF success rates,” Dr. Jones said at the meeting.

Dr. Jones and her associates examined outcomes after the first, fresh, autologous procedure for 4,609 women treated at Boston IVF in Brookline, Mass. from 2006 to 2010. Patients were aged 20-45 years.

A secondary outcome, the likelihood of implantation, was significantly different by BMI, compared with those with a normal BMI. Chances dropped for underweight women (BMI less than 18 kg/m

The likelihood of clinical pregnancy dropped only slightly for underweight women (adjusted OR, 0.98). However, it decreased significantly for overweight women (0.90) and for women in obesity class I (0.70), class II (0.41), and class III (0.43).

Interestingly, the miscarriage rate did not differ significantly according to maternal BMI, said Dr. Jones, a third-year resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

The normal-weight reference group included 2,605 patients with a BMI of 18.5-24.99 kg/m

In addition to its large sample size, the single institution design of the study is an advantage, Dr. Jones said. Previous researchers reported an association between increasing obesity and lower IVF success, but most of these studies were small, unadjusted, and focused on pregnancy rates.

“The live birth rate is the outcome most significant to our patients,” she said.

A systematic literature review found a decreased chance of IVF pregnancy (OR, 0.71) for overweight or obese women compared with normal weight women (Hum. Reprod. Update 2007;13:433-44). “But they only compared women in two groups – those with a BMI of 25 or less versus 25 plus,” Dr. Jones said.

In another study reported at the 2009 ASRM meeting, researchers found a lower clinical pregnancy rate and lower birth weights as maternal BMI increased (Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:245-52). This report was multicenter “and they did not necessarily control for differences in provider factors,” she said.

Dr. Jones and her associates also controlled for multiple potential confounders, including maternal age, paternal age, baseline follicle stimulating hormone levels, duration of stimulation, mean daily gonadotropin dose, peak estradiol, number of oocytes retrieved, use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection, embryo quality and number, transfer day, and number of embryos transferred.

From the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine

FDA: Appropriate SSRI Use OK in Pregnancy

Pregnant women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression may continue to do so, despite a 2006 warning that the drugs may predispose infants to persistent pulmonary hypertension, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

That earlier warning was based on a single study indicating that infants exposed to the drug in utero after the 20th week of pregnancy were six times more likely to develop persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) than nonexposed infants (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:579-87).

“Since then, there have been conflicting findings from new studies evaluating this potential risk, making it unclear whether use of SSRIs during pregnancy can cause persistent pulmonary hypertension,” the FDA said in a press statement.

The agency will update the drugs' warning labels to reflect data from new studies, which have produced conflicting results about the risk SSRIs may pose to an unborn child. Those studies include a large retrospective database study in 2009 that found no association between SSRI use and PPHN (Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:246-52), and a 2011 case-control study of 11,923 births that showed PPHN was associated with cesarean delivery but not with SSRI use in the second half of pregnancy (Am. J. Perinatol. 2011;28:19-24).

FDA officials concluded that the evidence is not sufficient to withhold SSRI treatment from pregnant women or take them off the antidepressants. “At present, FDA … recommends that health care providers treat depression during pregnancy as clinically appropriate,” according to the agency's statement.

Dr. Gideon Koren, professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto, commented in an interview, “I support FDA's hesitation in confirming causation of SSRIs in causing PPHN. The available studies are split in their ability to show an association between SSRIs taken in late pregnancy.

“Critically, several studies have shown that depression itself is also associated with increased risk of PPHN. Hence it is quite possible that depression and not its treatment cause this rare risk ('confounding by indication').” Dr. Koren also heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program.

Physicians and their patients should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of any antidepressant use in pregnancy, the FDA added, given that there are “substantial risks associated with undertreatment or no treatment of depression during pregnancy.” Risks of untreated maternal depression can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, lower Apgar scores, poor prenatal care, failure to recognize or report impending labor, and increased risks of fetal abuse, neonaticide or maternal suicide, the FDA warned.

Both the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend monitoring pregnant women for depression and treating them appropriately.

Physicians should continue to report any possible adverse effects to the FDA's MedWatch program, www.fda.gov/MedWatch/report.htm

Reporting forms can also be requested by calling 800-332-1088.

Dr. Koren said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

View on the News

Cautious Treatment Makes Sense

Even at the time of the first publication regarding the link between SSRIs and PPHN in 2006, the conclusion of the authors was that if the link is causal, the absolute risk for PPHN following late pregnancy exposure to SSRIs is very low. Thus, the recommendation that clinicians treat pregnant women appropriately for their symptoms was consistent with the initial findings, and continues to be so.

Since the initial publication, three others have appeared in full manuscript form and one in abstract form (now in press). The two published U.S. studies were either underpowered, or had limitations in classifying the outcomes, whereas the two Scandinavian studies confirmed the initial findings in large cohort or linked database studies. Importantly, the European studies that confirmed the association also came to the conclusion that SSRIs pose a small increased risk for a very rare outcome of pregnancy. Thus, the recommendation to treat only if needed, but not to avoid necessary treatment because of concern for PPHN continues to make sense.

CHRISTINA CHAMBERS, Ph.D., M.P.H., is associate professor of pediatrics and family and preventive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of the California Teratogen Information Service and Clinical Research Program. Dr. Chambers is a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists and past president of the Teratology Society. She said she currently receives grant funding for two studies unrelated to SSRIs from GlaxoSmithKline and GlaxoSmithKline Bio.

Pregnant women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression may continue to do so, despite a 2006 warning that the drugs may predispose infants to persistent pulmonary hypertension, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

That earlier warning was based on a single study indicating that infants exposed to the drug in utero after the 20th week of pregnancy were six times more likely to develop persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) than nonexposed infants (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:579-87).

“Since then, there have been conflicting findings from new studies evaluating this potential risk, making it unclear whether use of SSRIs during pregnancy can cause persistent pulmonary hypertension,” the FDA said in a press statement.

The agency will update the drugs' warning labels to reflect data from new studies, which have produced conflicting results about the risk SSRIs may pose to an unborn child. Those studies include a large retrospective database study in 2009 that found no association between SSRI use and PPHN (Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:246-52), and a 2011 case-control study of 11,923 births that showed PPHN was associated with cesarean delivery but not with SSRI use in the second half of pregnancy (Am. J. Perinatol. 2011;28:19-24).

FDA officials concluded that the evidence is not sufficient to withhold SSRI treatment from pregnant women or take them off the antidepressants. “At present, FDA … recommends that health care providers treat depression during pregnancy as clinically appropriate,” according to the agency's statement.

Dr. Gideon Koren, professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto, commented in an interview, “I support FDA's hesitation in confirming causation of SSRIs in causing PPHN. The available studies are split in their ability to show an association between SSRIs taken in late pregnancy.

“Critically, several studies have shown that depression itself is also associated with increased risk of PPHN. Hence it is quite possible that depression and not its treatment cause this rare risk ('confounding by indication').” Dr. Koren also heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program.

Physicians and their patients should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of any antidepressant use in pregnancy, the FDA added, given that there are “substantial risks associated with undertreatment or no treatment of depression during pregnancy.” Risks of untreated maternal depression can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, lower Apgar scores, poor prenatal care, failure to recognize or report impending labor, and increased risks of fetal abuse, neonaticide or maternal suicide, the FDA warned.

Both the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend monitoring pregnant women for depression and treating them appropriately.

Physicians should continue to report any possible adverse effects to the FDA's MedWatch program, www.fda.gov/MedWatch/report.htm

Reporting forms can also be requested by calling 800-332-1088.

Dr. Koren said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

View on the News

Cautious Treatment Makes Sense

Even at the time of the first publication regarding the link between SSRIs and PPHN in 2006, the conclusion of the authors was that if the link is causal, the absolute risk for PPHN following late pregnancy exposure to SSRIs is very low. Thus, the recommendation that clinicians treat pregnant women appropriately for their symptoms was consistent with the initial findings, and continues to be so.

Since the initial publication, three others have appeared in full manuscript form and one in abstract form (now in press). The two published U.S. studies were either underpowered, or had limitations in classifying the outcomes, whereas the two Scandinavian studies confirmed the initial findings in large cohort or linked database studies. Importantly, the European studies that confirmed the association also came to the conclusion that SSRIs pose a small increased risk for a very rare outcome of pregnancy. Thus, the recommendation to treat only if needed, but not to avoid necessary treatment because of concern for PPHN continues to make sense.

CHRISTINA CHAMBERS, Ph.D., M.P.H., is associate professor of pediatrics and family and preventive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of the California Teratogen Information Service and Clinical Research Program. Dr. Chambers is a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists and past president of the Teratology Society. She said she currently receives grant funding for two studies unrelated to SSRIs from GlaxoSmithKline and GlaxoSmithKline Bio.

Pregnant women taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression may continue to do so, despite a 2006 warning that the drugs may predispose infants to persistent pulmonary hypertension, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

That earlier warning was based on a single study indicating that infants exposed to the drug in utero after the 20th week of pregnancy were six times more likely to develop persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) than nonexposed infants (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:579-87).

“Since then, there have been conflicting findings from new studies evaluating this potential risk, making it unclear whether use of SSRIs during pregnancy can cause persistent pulmonary hypertension,” the FDA said in a press statement.

The agency will update the drugs' warning labels to reflect data from new studies, which have produced conflicting results about the risk SSRIs may pose to an unborn child. Those studies include a large retrospective database study in 2009 that found no association between SSRI use and PPHN (Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:246-52), and a 2011 case-control study of 11,923 births that showed PPHN was associated with cesarean delivery but not with SSRI use in the second half of pregnancy (Am. J. Perinatol. 2011;28:19-24).

FDA officials concluded that the evidence is not sufficient to withhold SSRI treatment from pregnant women or take them off the antidepressants. “At present, FDA … recommends that health care providers treat depression during pregnancy as clinically appropriate,” according to the agency's statement.

Dr. Gideon Koren, professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto, commented in an interview, “I support FDA's hesitation in confirming causation of SSRIs in causing PPHN. The available studies are split in their ability to show an association between SSRIs taken in late pregnancy.

“Critically, several studies have shown that depression itself is also associated with increased risk of PPHN. Hence it is quite possible that depression and not its treatment cause this rare risk ('confounding by indication').” Dr. Koren also heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program.

Physicians and their patients should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of any antidepressant use in pregnancy, the FDA added, given that there are “substantial risks associated with undertreatment or no treatment of depression during pregnancy.” Risks of untreated maternal depression can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, lower Apgar scores, poor prenatal care, failure to recognize or report impending labor, and increased risks of fetal abuse, neonaticide or maternal suicide, the FDA warned.

Both the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend monitoring pregnant women for depression and treating them appropriately.

Physicians should continue to report any possible adverse effects to the FDA's MedWatch program, www.fda.gov/MedWatch/report.htm

Reporting forms can also be requested by calling 800-332-1088.

Dr. Koren said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

View on the News

Cautious Treatment Makes Sense

Even at the time of the first publication regarding the link between SSRIs and PPHN in 2006, the conclusion of the authors was that if the link is causal, the absolute risk for PPHN following late pregnancy exposure to SSRIs is very low. Thus, the recommendation that clinicians treat pregnant women appropriately for their symptoms was consistent with the initial findings, and continues to be so.

Since the initial publication, three others have appeared in full manuscript form and one in abstract form (now in press). The two published U.S. studies were either underpowered, or had limitations in classifying the outcomes, whereas the two Scandinavian studies confirmed the initial findings in large cohort or linked database studies. Importantly, the European studies that confirmed the association also came to the conclusion that SSRIs pose a small increased risk for a very rare outcome of pregnancy. Thus, the recommendation to treat only if needed, but not to avoid necessary treatment because of concern for PPHN continues to make sense.

CHRISTINA CHAMBERS, Ph.D., M.P.H., is associate professor of pediatrics and family and preventive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of the California Teratogen Information Service and Clinical Research Program. Dr. Chambers is a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists and past president of the Teratology Society. She said she currently receives grant funding for two studies unrelated to SSRIs from GlaxoSmithKline and GlaxoSmithKline Bio.

No Chemo if hCG Falls After Molar Pregnancy

Women with raised but falling human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations 6 months after a molar pregnancy do not need chemotherapy, as almost all of them will spontaneously remit, the results of a large retrospective cohort study have shown.

The findings, published online in the Lancet (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61265-8]), challenge current international clinical guidelines (Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2002;77:285-7) that consider chemotherapy to be indicated when hCG concentrations are high for 6 months or more following evacuation of a hydatidiform mole.

The new findings argue that an elevated hCG level at 6 months is not an indicator of malignancy when values are falling, and that instead of initiating chemotherapy, women with raised but falling hCG can undergo surveillance of their hCG levels, with testing until they return to normal.

Chemotherapy is needed only if hCG levels are still rising at 6 months, have plateaued, or are greater than 345 IU/L, or if there is radiologic evidence of neoplasia.

If the surveillance approach were to become standard, more women could avoid exposure to toxic chemotherapy drugs and could safely conceive sooner after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, said the authors of the study led by Dr. Roshan Agarwal of Imperial College London.

Current U.K. guidelines advise women not to become pregnant until 12 months following chemotherapy, whereas they would have to wait only 6 months after a spontaneous return to normal hCG.

For their research, Dr. Agarwal and colleagues retrospectively identified 13,960 women registered at London's Charing Cross Hospital between January 1993 and May 2008 who had undergone evacuation of a complete or partial hydatidiform mole. Of these, 974 (7%) required chemotherapy within 6 months, and hCG normalized spontaneously in 12,910 (92%) within 6 months.

The remaining 76 women still had high hCG concentrations (more than 5 IU/L) 6 months after evacuation of the molar pregnancy. Sixty-six patients underwent surveillance, in which blood and urine samples were collected and evaluated every 2 weeks until normal hCG was achieved, followed by monthly urine samples for 6 months. Ten patients underwent chemotherapy.

In the surveillance group, 98% of patients (n = 65) saw hCG values return to normal without chemotherapy (in all but 6 of them within a year), and the remaining patient, who had chronic renal failure, remained healthy despite having elevated hCG, Dr. Agarwal and colleagues reported.

Among the 10 patients who received chemotherapy, 6 had complete responses, and 4 had partial or no responses but remained well, even though hCG concentrations in 2 patients continued to be elevated. There was no significant difference in time to normalization between the groups and no deaths had occurred in either group after a median 2 years' follow-up.

The investigators acknowledged that a weakness of their study is retrospective design, the use of a single study site, and the small number of patients with raised hCG at 6 months.

However, they said, the findings “directly challenge the present clinical dogma” to show that the surveillance model is clinically acceptable. The results “will change international practice and spare women unnecessary exposure to chemotherapy,” they wrote in their analysis.

In a case study linked to Dr. Agarwal and colleagues' article, Rosemary A. Fisher, also of Imperial College London, described a woman who had a miscarriage and three consecutive molar pregnancies, yet was able to achieve a normal pregnancy with use of a donor egg.

“To the best of our knowledge, this report establishes for the first time that oocyte donation can enable women with familial recurrent hydatidiform moles due to NLRP7 mutations to achieve a normal pregnancy,” Ms. Fisher and colleagues wrote, adding that this finding offered “hope to other women with this condition.”

The study also shows “that the major role of NLRP7 in pregnancy is in the developing oocyte,” they said.

I think this study is

interesting. The number of patients who were treated with chemotherapy

was very small (10 of 76 patients). Therefore, comparison of the

patients who received chemotherapy versus surveillance is difficult due

to the size of the study, the retrospective nature of the study, as well

as the fact that the patients who received chemotherapy had higher

median hCG levels than those under surveillance (157 vs. 13). HCG levels

also were not well correlated with remission (r = 0.233; p = 0.049).

Patients

with low hCG levels at 6 months can probably be offered surveillance as

an alternative to chemotherapy in select circumstances. However, due to

the aforementioned concerns, before these findings are applied

wholesale in clinical practice, additional studies including a

prospective study are necessary.

E. ALBERT REECE, M.D., Ph.D, M.B.A., is

vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland,

Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished

Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant

financial disclosures.

Treatment Still a Bit of a Conundrum

The data from Dr.

Agarwal and colleagues' study are reassuring. However, 13% of the cohort

received chemotherapy, and how these individuals would have progressed

if no treatment were given is unknown. Hence, the key question remains:

When and to whom should chemotherapy be given? The investigators propose

a cutoff hCG concentration of 345 IU/L at 6 months, which was the

median hCG value in patients who responded to chemotherapy in their

cohort.

Meanwhile, investigators in an earlier study (Gynecol.

Oncol. 2010;116:3-9) proposed that chemotherapy should be started only

when total hCG begins to rise and is greater than 3,000 IU/L, because

chemotherapy would probably be ineffective below this value. Direct

comparison between the two cohorts is inappropriate because the group in

the earlier study was heterogeneous (patients had been given various

previous treatments), whereas Dr. Agarwal and colleagues' group was

unique in its homogeneity (all patients had persistently raised but

falling hCG levels after a molar pregnancy). Centers treating this

condition and using a particular protocol should report their findings

so recommendations can be updated for improved treatment of these

patients.

ANNIE N.Y. Cheung, M.D., and KAREN K.L. CHAN, M.D., are

both with the University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong.

They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. They wrote an

editorial accompanying the Agarwal article (Lancet 2011

[doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61518-3]).

I think this study is

interesting. The number of patients who were treated with chemotherapy

was very small (10 of 76 patients). Therefore, comparison of the

patients who received chemotherapy versus surveillance is difficult due

to the size of the study, the retrospective nature of the study, as well

as the fact that the patients who received chemotherapy had higher

median hCG levels than those under surveillance (157 vs. 13). HCG levels

also were not well correlated with remission (r = 0.233; p = 0.049).

Patients

with low hCG levels at 6 months can probably be offered surveillance as

an alternative to chemotherapy in select circumstances. However, due to

the aforementioned concerns, before these findings are applied

wholesale in clinical practice, additional studies including a

prospective study are necessary.

E. ALBERT REECE, M.D., Ph.D, M.B.A., is

vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland,

Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished

Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant

financial disclosures.

Treatment Still a Bit of a Conundrum

The data from Dr.

Agarwal and colleagues' study are reassuring. However, 13% of the cohort

received chemotherapy, and how these individuals would have progressed

if no treatment were given is unknown. Hence, the key question remains:

When and to whom should chemotherapy be given? The investigators propose

a cutoff hCG concentration of 345 IU/L at 6 months, which was the

median hCG value in patients who responded to chemotherapy in their

cohort.

Meanwhile, investigators in an earlier study (Gynecol.

Oncol. 2010;116:3-9) proposed that chemotherapy should be started only

when total hCG begins to rise and is greater than 3,000 IU/L, because

chemotherapy would probably be ineffective below this value. Direct

comparison between the two cohorts is inappropriate because the group in

the earlier study was heterogeneous (patients had been given various

previous treatments), whereas Dr. Agarwal and colleagues' group was

unique in its homogeneity (all patients had persistently raised but

falling hCG levels after a molar pregnancy). Centers treating this

condition and using a particular protocol should report their findings

so recommendations can be updated for improved treatment of these

patients.

ANNIE N.Y. Cheung, M.D., and KAREN K.L. CHAN, M.D., are

both with the University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong.

They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. They wrote an

editorial accompanying the Agarwal article (Lancet 2011

[doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61518-3]).

I think this study is

interesting. The number of patients who were treated with chemotherapy

was very small (10 of 76 patients). Therefore, comparison of the

patients who received chemotherapy versus surveillance is difficult due

to the size of the study, the retrospective nature of the study, as well

as the fact that the patients who received chemotherapy had higher

median hCG levels than those under surveillance (157 vs. 13). HCG levels

also were not well correlated with remission (r = 0.233; p = 0.049).

Patients

with low hCG levels at 6 months can probably be offered surveillance as

an alternative to chemotherapy in select circumstances. However, due to

the aforementioned concerns, before these findings are applied

wholesale in clinical practice, additional studies including a

prospective study are necessary.

E. ALBERT REECE, M.D., Ph.D, M.B.A., is

vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland,

Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished

Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant

financial disclosures.

Treatment Still a Bit of a Conundrum

The data from Dr.

Agarwal and colleagues' study are reassuring. However, 13% of the cohort

received chemotherapy, and how these individuals would have progressed

if no treatment were given is unknown. Hence, the key question remains:

When and to whom should chemotherapy be given? The investigators propose

a cutoff hCG concentration of 345 IU/L at 6 months, which was the

median hCG value in patients who responded to chemotherapy in their

cohort.

Meanwhile, investigators in an earlier study (Gynecol.

Oncol. 2010;116:3-9) proposed that chemotherapy should be started only

when total hCG begins to rise and is greater than 3,000 IU/L, because

chemotherapy would probably be ineffective below this value. Direct

comparison between the two cohorts is inappropriate because the group in

the earlier study was heterogeneous (patients had been given various

previous treatments), whereas Dr. Agarwal and colleagues' group was

unique in its homogeneity (all patients had persistently raised but

falling hCG levels after a molar pregnancy). Centers treating this

condition and using a particular protocol should report their findings

so recommendations can be updated for improved treatment of these

patients.

ANNIE N.Y. Cheung, M.D., and KAREN K.L. CHAN, M.D., are

both with the University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong.

They said they had no relevant financial disclosures. They wrote an

editorial accompanying the Agarwal article (Lancet 2011

[doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61518-3]).

Women with raised but falling human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations 6 months after a molar pregnancy do not need chemotherapy, as almost all of them will spontaneously remit, the results of a large retrospective cohort study have shown.

The findings, published online in the Lancet (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61265-8]), challenge current international clinical guidelines (Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2002;77:285-7) that consider chemotherapy to be indicated when hCG concentrations are high for 6 months or more following evacuation of a hydatidiform mole.

The new findings argue that an elevated hCG level at 6 months is not an indicator of malignancy when values are falling, and that instead of initiating chemotherapy, women with raised but falling hCG can undergo surveillance of their hCG levels, with testing until they return to normal.

Chemotherapy is needed only if hCG levels are still rising at 6 months, have plateaued, or are greater than 345 IU/L, or if there is radiologic evidence of neoplasia.

If the surveillance approach were to become standard, more women could avoid exposure to toxic chemotherapy drugs and could safely conceive sooner after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, said the authors of the study led by Dr. Roshan Agarwal of Imperial College London.

Current U.K. guidelines advise women not to become pregnant until 12 months following chemotherapy, whereas they would have to wait only 6 months after a spontaneous return to normal hCG.

For their research, Dr. Agarwal and colleagues retrospectively identified 13,960 women registered at London's Charing Cross Hospital between January 1993 and May 2008 who had undergone evacuation of a complete or partial hydatidiform mole. Of these, 974 (7%) required chemotherapy within 6 months, and hCG normalized spontaneously in 12,910 (92%) within 6 months.

The remaining 76 women still had high hCG concentrations (more than 5 IU/L) 6 months after evacuation of the molar pregnancy. Sixty-six patients underwent surveillance, in which blood and urine samples were collected and evaluated every 2 weeks until normal hCG was achieved, followed by monthly urine samples for 6 months. Ten patients underwent chemotherapy.

In the surveillance group, 98% of patients (n = 65) saw hCG values return to normal without chemotherapy (in all but 6 of them within a year), and the remaining patient, who had chronic renal failure, remained healthy despite having elevated hCG, Dr. Agarwal and colleagues reported.

Among the 10 patients who received chemotherapy, 6 had complete responses, and 4 had partial or no responses but remained well, even though hCG concentrations in 2 patients continued to be elevated. There was no significant difference in time to normalization between the groups and no deaths had occurred in either group after a median 2 years' follow-up.

The investigators acknowledged that a weakness of their study is retrospective design, the use of a single study site, and the small number of patients with raised hCG at 6 months.

However, they said, the findings “directly challenge the present clinical dogma” to show that the surveillance model is clinically acceptable. The results “will change international practice and spare women unnecessary exposure to chemotherapy,” they wrote in their analysis.

In a case study linked to Dr. Agarwal and colleagues' article, Rosemary A. Fisher, also of Imperial College London, described a woman who had a miscarriage and three consecutive molar pregnancies, yet was able to achieve a normal pregnancy with use of a donor egg.

“To the best of our knowledge, this report establishes for the first time that oocyte donation can enable women with familial recurrent hydatidiform moles due to NLRP7 mutations to achieve a normal pregnancy,” Ms. Fisher and colleagues wrote, adding that this finding offered “hope to other women with this condition.”

The study also shows “that the major role of NLRP7 in pregnancy is in the developing oocyte,” they said.

Women with raised but falling human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations 6 months after a molar pregnancy do not need chemotherapy, as almost all of them will spontaneously remit, the results of a large retrospective cohort study have shown.

The findings, published online in the Lancet (Lancet 2011 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61265-8]), challenge current international clinical guidelines (Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2002;77:285-7) that consider chemotherapy to be indicated when hCG concentrations are high for 6 months or more following evacuation of a hydatidiform mole.

The new findings argue that an elevated hCG level at 6 months is not an indicator of malignancy when values are falling, and that instead of initiating chemotherapy, women with raised but falling hCG can undergo surveillance of their hCG levels, with testing until they return to normal.

Chemotherapy is needed only if hCG levels are still rising at 6 months, have plateaued, or are greater than 345 IU/L, or if there is radiologic evidence of neoplasia.

If the surveillance approach were to become standard, more women could avoid exposure to toxic chemotherapy drugs and could safely conceive sooner after evacuation of a molar pregnancy, said the authors of the study led by Dr. Roshan Agarwal of Imperial College London.

Current U.K. guidelines advise women not to become pregnant until 12 months following chemotherapy, whereas they would have to wait only 6 months after a spontaneous return to normal hCG.

For their research, Dr. Agarwal and colleagues retrospectively identified 13,960 women registered at London's Charing Cross Hospital between January 1993 and May 2008 who had undergone evacuation of a complete or partial hydatidiform mole. Of these, 974 (7%) required chemotherapy within 6 months, and hCG normalized spontaneously in 12,910 (92%) within 6 months.

The remaining 76 women still had high hCG concentrations (more than 5 IU/L) 6 months after evacuation of the molar pregnancy. Sixty-six patients underwent surveillance, in which blood and urine samples were collected and evaluated every 2 weeks until normal hCG was achieved, followed by monthly urine samples for 6 months. Ten patients underwent chemotherapy.