User login

Have you made best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH?

- Read a related case in July’s Medical Verdicts

- “10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage”

Baha M. Sibai, MD (June 2011) - “Postpartum hemorrhage: 11 critical questions, answered by an expert”

Q&A with Haywood L. Brown, MD (January 2011) - “What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice”

Eric J. Bieber, MD; Linda Scott, RN; Corinna Muller, DO; Nancy Nuss, RN; and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010) - “Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; August 2009) - “Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage”

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008)

Obstetricians know that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) must be treated decisively and swiftly.1 To review:

Active management of the third stage after vaginal delivery, with a uterotonic such as oxytocin, helps to reduce the frequency of PPH2; in a recent randomized trial involving vaginal delivery, the rate of PPH was 10% in women who received postpartum oxytocin and 17% in those who did not (P<.001).3

When hemorrhage occurs despite oxytocin, having been given postpartum, the standard treatment algorithm (see the TABLE) calls for:

- uterine massage

- additional uterotonics

- identification and repair of vaginal and cervical lacerations

- removal of any retained products of conception.

Sequential interventions for managing postpartum hemorrhage

| This sequence of steps applies 1) after vaginal delivery (including the left hand-side interventions) and 2) after cesarean delivery, with the abdominal incision still open (including the right hand-side interventions). | |

| Hemorrhage after vaginal birth | Hemorrhage after cesarean delivery |

| Administer oxytocin | |

| Perform uterine massage | |

| Administer additional uterotonics (methergine, misoprostol, carboprost [Hemabate]) | |

| Bring 2 units of packed RBCs and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to point of care Transfuse based on the clinical condition Consider transfusing RBCs and FFP at a 1:1 ratio until clotting parameters are evaluated Obtain Stat clotting studies Start an additional intravenous line | |

| Move the patient to the operating room |

|

| Repair any tears |

|

| Place uterine compression suture(s), such as a B-Lynch suture |

| Place an intrauterine balloon | Consider bilateral ligation of the internal iliac artery |

| If indicated, call for additional specialists: second anesthesiologist, gyn surgeon, interventional radiologist, blood bank director | |

| Selective embolization by interventional radiology | Hysterectomy |

| Exploratory laparotomy—follow steps (along the right-hand side of this table) for treating hemorrhage after cesarean delivery | Pelvic packing |

| Adapted from: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (www.CMQCC.org). | |

Placing an intrauterine balloon, such as the Bakri Postpartum Balloon (Cook Medical) or the BT-Cath (Utah Medical Products), is strongly recommended if these steps do not control bleeding.

In this Editorial, I review tips and tricks for using the Bakri balloon, building on my earlier OBG Management Editorial (February 2009), in which I outlined a basic approach to intrauterine balloon tamponade.4

TIP: Place the Bakri balloon early in the PPH treatment algorithm

For postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery, typical initial steps include, as noted, fundal massage, administration of uterotonics, and curettage to remove retained products of conception. If these steps are ineffective, don’t wait: Immediately consider placing a Bakri balloon. Time is precious, and wasting time with less effective interventions results in excessive blood loss and consumption of clotting factors and increases the risk of a coagulopathy.

I’ve found that clinicians often spend too much time trying to determine whether postpartum bleeding originates in the uterus or from a cervical or vaginal laceration. But heavy bleeding can obscure anatomic structures, making it difficult to identify the site of bleeding with precision. Fruitlessly perseverating to differentiate uterine, cervical, and upper vaginal sources of bleeding can waste valuable time and lead to unnecessary blood loss.

By placing a Bakri balloon and inflating it early in the PPH treatment algorithm, you will significantly reduce uterine bleeding. You will also be able to assess the cervix and upper vagina more effectively for lacerations.

My recommendation. Place the Bakri balloon as soon as it is apparent that bleeding is so heavy that you are going to have difficulty assessing the cervix and upper vagina for lacerations. Note that this stands in contrast to the usual recommendation that you assess the cervix and vagina for lacerations before you place the Bakri balloon.

TIP: Have 3 clinicians place the balloon

Teamwork is a key to success here: The Bakri balloon is most quickly and elegantly inserted and inflated when three clinicians team up, as follows:

Clinician#1 scans the uterus, assessing for retained products of conception and providing real-time imaging as the balloon is placed and inflated. This team member provides feedback to the others about correct placement and filling of the balloon.

Clinician#2 inserts the balloon into the uterus by placing her hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position. (Most often, clinician#2 is the delivering clinician.) This technique is performed in a manner similar to how one places an intrauterine pressure catheter.5

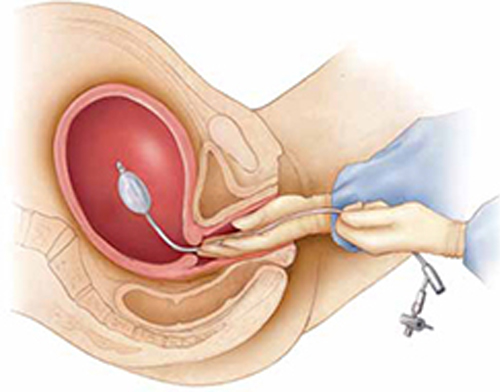

Clinician #2 stabilizes the balloon in position by maintaining her hand in the vagina. She ensures that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled (FIGURE).

Manual insertion of a Bakri balloon

Insert the balloon into the uterus by 1) placing your hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position (similar to the manner in which an intrauterine pressure catheter is placed),5 2) stabilizing the balloon in position by maintaining the hand in the vagina, and 3) ensuring that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled.Clinician #3 simultaneously begins to instill sterile fluid into the balloon. This team member can be a nurse, medical assistant, or surgical technician.

My recommendation. Consider using simulation training to practice the team approach to placing the Bakri balloon. This is an effective method of improving team coordination.

TIP: Instill at least 150 mL of fluid

In short, use more fluid, not less. Although one study showed that most clinicians fill the balloon to a median volume of 300 mL,6 I’ve observed that some timidly instill the balloon with 80 to 120 mL of fluid. I think this is too little to maximize the effectiveness of the balloon for a postpartum patient who has massive hemorrhage.

Studies have shown that filling the balloon to at least 150 mL noticeably increases tamponade pressure.7

TIP: Place a pack in the upper vagina to stabilize the balloon in position

It usually takes only a few minutes after the Bakri balloon is filled to determine whether it is going to control uterine bleeding—what is called a tamponade test. If the balloon does control bleeding, you can place a vaginal pack of ribbon gauze to help ensure that the balloon does not slip down through the dilated postpartum cervix.

To avoid obscuring continued bleeding, however, do not place vaginal packing until you have obtained a positive tamponade test.

TIP: Check the hemoglobin concentration, platelet count, and coagulation status

The trauma literature demonstrates that optimal patient outcomes are realized when the following targets are maintained during resuscitation of patients who have massive hemorrhage8:

- hematocrit, ≥21%

- platelet count, ≥50 × 103/μL

- fibrinogen ≥100 mg/dL

- International Normalized Ratio (INR) ≤1.5.

These targets are achieved by appropriate transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and purified recombinant fibrinogen concentrate (RiaSTAP). Many trauma specialists recommend transfusion of a 1:1 ratio of RBCs and fresh frozen plasma in cases of major hemorrhage until coagulation status is normalized.

My recommendation. Often, it takes as long as 1 hour (sometimes, longer) to get results of Stat coagulation tests from the lab. While you are waiting, obtain clinical evidence of clotting function by filling a red-top tube with the patient’s blood. Adequate function is signaled by formation of a stable clot within 10 minutes.

TIP: Practice your team’s response to PPH with simulation

Last, I urge clinicians in every birthing unit to use simulation exercises to improve all facets of their response to severe postpartum hemorrhage.9

Summing up

Death following PPH remains a major cause of maternal mortality in developed and developing countries. The appropriateness of your response within 10 minutes of the onset of PPH is critical to ensuring a successful outcome and minimizing adverse events.10 To help, use the Bakri Postpartum Balloon often, and use it early.

What are your tips and tricks for effective use of intra-uterine balloon tamponade in postpartum hemorrhage?

To enter your response, click here or send your pearl to [email protected], with your name and location of practice.

We’ll publish a sampling of bylined contributions in an upcoming issue of OBG Management, with appreciation.

1. Sibai BM. 10 practical evidence-based recommendations for managing severe postpartum hemorrhage. OBG Manage. 2011;23(6):44-48.

2. Barbieri RL. Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor. OBG Manage. 2007;19(05):6-13.

3. Jangsten E, Mattsson LA, Lyckestam I, Hellstrom AL, Berg M. A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2011;118(3):362-369.

4. Barbieri RL. You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatment for OB bleeds. OBG Manage. 2009;21(2):6-10.

5. Dabelea V, Schultze PM, McDuffie RS, Jr. Intrauterine balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24(6):359-364.

6. Vitthala S, Tsoumpou I, Anjum ZK, Aziz NA. Use of Bakri balloon in post-partum hemorrhage: a series of 15 cases. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;49(2):191-194.

7. Georgiou C. Intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of a positive “tamponade test” in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. BJOG. 2010;117(3):295-303.

8. Barbieri RL. Control of massive hemorrhage: Lessons from Iraq reach the US labor and delivery suite. OBG Manage. 2007;19(7):8-16.

9. Skupski DW, Lowenwirt IP, Weinbaum FI, Brodsky D, Danek M, Eglinton GS. Improving hospital systems for the care of women with major obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):977-983.

10. Driessen M, Bouvier-Colle MH, Dupont C, et al. Pithagore6 Group Postpartum hemorrhage resulting from uterine atony after vaginal delivery: factors associated with severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):21-31.

- Read a related case in July’s Medical Verdicts

- “10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage”

Baha M. Sibai, MD (June 2011) - “Postpartum hemorrhage: 11 critical questions, answered by an expert”

Q&A with Haywood L. Brown, MD (January 2011) - “What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice”

Eric J. Bieber, MD; Linda Scott, RN; Corinna Muller, DO; Nancy Nuss, RN; and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010) - “Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; August 2009) - “Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage”

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008)

Obstetricians know that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) must be treated decisively and swiftly.1 To review:

Active management of the third stage after vaginal delivery, with a uterotonic such as oxytocin, helps to reduce the frequency of PPH2; in a recent randomized trial involving vaginal delivery, the rate of PPH was 10% in women who received postpartum oxytocin and 17% in those who did not (P<.001).3

When hemorrhage occurs despite oxytocin, having been given postpartum, the standard treatment algorithm (see the TABLE) calls for:

- uterine massage

- additional uterotonics

- identification and repair of vaginal and cervical lacerations

- removal of any retained products of conception.

Sequential interventions for managing postpartum hemorrhage

| This sequence of steps applies 1) after vaginal delivery (including the left hand-side interventions) and 2) after cesarean delivery, with the abdominal incision still open (including the right hand-side interventions). | |

| Hemorrhage after vaginal birth | Hemorrhage after cesarean delivery |

| Administer oxytocin | |

| Perform uterine massage | |

| Administer additional uterotonics (methergine, misoprostol, carboprost [Hemabate]) | |

| Bring 2 units of packed RBCs and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to point of care Transfuse based on the clinical condition Consider transfusing RBCs and FFP at a 1:1 ratio until clotting parameters are evaluated Obtain Stat clotting studies Start an additional intravenous line | |

| Move the patient to the operating room |

|

| Repair any tears |

|

| Place uterine compression suture(s), such as a B-Lynch suture |

| Place an intrauterine balloon | Consider bilateral ligation of the internal iliac artery |

| If indicated, call for additional specialists: second anesthesiologist, gyn surgeon, interventional radiologist, blood bank director | |

| Selective embolization by interventional radiology | Hysterectomy |

| Exploratory laparotomy—follow steps (along the right-hand side of this table) for treating hemorrhage after cesarean delivery | Pelvic packing |

| Adapted from: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (www.CMQCC.org). | |

Placing an intrauterine balloon, such as the Bakri Postpartum Balloon (Cook Medical) or the BT-Cath (Utah Medical Products), is strongly recommended if these steps do not control bleeding.

In this Editorial, I review tips and tricks for using the Bakri balloon, building on my earlier OBG Management Editorial (February 2009), in which I outlined a basic approach to intrauterine balloon tamponade.4

TIP: Place the Bakri balloon early in the PPH treatment algorithm

For postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery, typical initial steps include, as noted, fundal massage, administration of uterotonics, and curettage to remove retained products of conception. If these steps are ineffective, don’t wait: Immediately consider placing a Bakri balloon. Time is precious, and wasting time with less effective interventions results in excessive blood loss and consumption of clotting factors and increases the risk of a coagulopathy.

I’ve found that clinicians often spend too much time trying to determine whether postpartum bleeding originates in the uterus or from a cervical or vaginal laceration. But heavy bleeding can obscure anatomic structures, making it difficult to identify the site of bleeding with precision. Fruitlessly perseverating to differentiate uterine, cervical, and upper vaginal sources of bleeding can waste valuable time and lead to unnecessary blood loss.

By placing a Bakri balloon and inflating it early in the PPH treatment algorithm, you will significantly reduce uterine bleeding. You will also be able to assess the cervix and upper vagina more effectively for lacerations.

My recommendation. Place the Bakri balloon as soon as it is apparent that bleeding is so heavy that you are going to have difficulty assessing the cervix and upper vagina for lacerations. Note that this stands in contrast to the usual recommendation that you assess the cervix and vagina for lacerations before you place the Bakri balloon.

TIP: Have 3 clinicians place the balloon

Teamwork is a key to success here: The Bakri balloon is most quickly and elegantly inserted and inflated when three clinicians team up, as follows:

Clinician#1 scans the uterus, assessing for retained products of conception and providing real-time imaging as the balloon is placed and inflated. This team member provides feedback to the others about correct placement and filling of the balloon.

Clinician#2 inserts the balloon into the uterus by placing her hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position. (Most often, clinician#2 is the delivering clinician.) This technique is performed in a manner similar to how one places an intrauterine pressure catheter.5

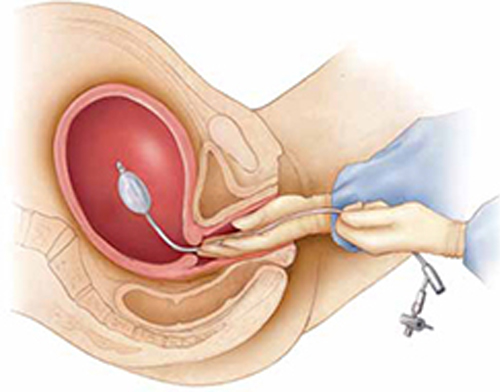

Clinician #2 stabilizes the balloon in position by maintaining her hand in the vagina. She ensures that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled (FIGURE).

Manual insertion of a Bakri balloon

Insert the balloon into the uterus by 1) placing your hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position (similar to the manner in which an intrauterine pressure catheter is placed),5 2) stabilizing the balloon in position by maintaining the hand in the vagina, and 3) ensuring that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled.Clinician #3 simultaneously begins to instill sterile fluid into the balloon. This team member can be a nurse, medical assistant, or surgical technician.

My recommendation. Consider using simulation training to practice the team approach to placing the Bakri balloon. This is an effective method of improving team coordination.

TIP: Instill at least 150 mL of fluid

In short, use more fluid, not less. Although one study showed that most clinicians fill the balloon to a median volume of 300 mL,6 I’ve observed that some timidly instill the balloon with 80 to 120 mL of fluid. I think this is too little to maximize the effectiveness of the balloon for a postpartum patient who has massive hemorrhage.

Studies have shown that filling the balloon to at least 150 mL noticeably increases tamponade pressure.7

TIP: Place a pack in the upper vagina to stabilize the balloon in position

It usually takes only a few minutes after the Bakri balloon is filled to determine whether it is going to control uterine bleeding—what is called a tamponade test. If the balloon does control bleeding, you can place a vaginal pack of ribbon gauze to help ensure that the balloon does not slip down through the dilated postpartum cervix.

To avoid obscuring continued bleeding, however, do not place vaginal packing until you have obtained a positive tamponade test.

TIP: Check the hemoglobin concentration, platelet count, and coagulation status

The trauma literature demonstrates that optimal patient outcomes are realized when the following targets are maintained during resuscitation of patients who have massive hemorrhage8:

- hematocrit, ≥21%

- platelet count, ≥50 × 103/μL

- fibrinogen ≥100 mg/dL

- International Normalized Ratio (INR) ≤1.5.

These targets are achieved by appropriate transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and purified recombinant fibrinogen concentrate (RiaSTAP). Many trauma specialists recommend transfusion of a 1:1 ratio of RBCs and fresh frozen plasma in cases of major hemorrhage until coagulation status is normalized.

My recommendation. Often, it takes as long as 1 hour (sometimes, longer) to get results of Stat coagulation tests from the lab. While you are waiting, obtain clinical evidence of clotting function by filling a red-top tube with the patient’s blood. Adequate function is signaled by formation of a stable clot within 10 minutes.

TIP: Practice your team’s response to PPH with simulation

Last, I urge clinicians in every birthing unit to use simulation exercises to improve all facets of their response to severe postpartum hemorrhage.9

Summing up

Death following PPH remains a major cause of maternal mortality in developed and developing countries. The appropriateness of your response within 10 minutes of the onset of PPH is critical to ensuring a successful outcome and minimizing adverse events.10 To help, use the Bakri Postpartum Balloon often, and use it early.

What are your tips and tricks for effective use of intra-uterine balloon tamponade in postpartum hemorrhage?

To enter your response, click here or send your pearl to [email protected], with your name and location of practice.

We’ll publish a sampling of bylined contributions in an upcoming issue of OBG Management, with appreciation.

- Read a related case in July’s Medical Verdicts

- “10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage”

Baha M. Sibai, MD (June 2011) - “Postpartum hemorrhage: 11 critical questions, answered by an expert”

Q&A with Haywood L. Brown, MD (January 2011) - “What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice”

Eric J. Bieber, MD; Linda Scott, RN; Corinna Muller, DO; Nancy Nuss, RN; and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010) - “Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; August 2009) - “Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage”

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008)

Obstetricians know that postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) must be treated decisively and swiftly.1 To review:

Active management of the third stage after vaginal delivery, with a uterotonic such as oxytocin, helps to reduce the frequency of PPH2; in a recent randomized trial involving vaginal delivery, the rate of PPH was 10% in women who received postpartum oxytocin and 17% in those who did not (P<.001).3

When hemorrhage occurs despite oxytocin, having been given postpartum, the standard treatment algorithm (see the TABLE) calls for:

- uterine massage

- additional uterotonics

- identification and repair of vaginal and cervical lacerations

- removal of any retained products of conception.

Sequential interventions for managing postpartum hemorrhage

| This sequence of steps applies 1) after vaginal delivery (including the left hand-side interventions) and 2) after cesarean delivery, with the abdominal incision still open (including the right hand-side interventions). | |

| Hemorrhage after vaginal birth | Hemorrhage after cesarean delivery |

| Administer oxytocin | |

| Perform uterine massage | |

| Administer additional uterotonics (methergine, misoprostol, carboprost [Hemabate]) | |

| Bring 2 units of packed RBCs and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) to point of care Transfuse based on the clinical condition Consider transfusing RBCs and FFP at a 1:1 ratio until clotting parameters are evaluated Obtain Stat clotting studies Start an additional intravenous line | |

| Move the patient to the operating room |

|

| Repair any tears |

|

| Place uterine compression suture(s), such as a B-Lynch suture |

| Place an intrauterine balloon | Consider bilateral ligation of the internal iliac artery |

| If indicated, call for additional specialists: second anesthesiologist, gyn surgeon, interventional radiologist, blood bank director | |

| Selective embolization by interventional radiology | Hysterectomy |

| Exploratory laparotomy—follow steps (along the right-hand side of this table) for treating hemorrhage after cesarean delivery | Pelvic packing |

| Adapted from: California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (www.CMQCC.org). | |

Placing an intrauterine balloon, such as the Bakri Postpartum Balloon (Cook Medical) or the BT-Cath (Utah Medical Products), is strongly recommended if these steps do not control bleeding.

In this Editorial, I review tips and tricks for using the Bakri balloon, building on my earlier OBG Management Editorial (February 2009), in which I outlined a basic approach to intrauterine balloon tamponade.4

TIP: Place the Bakri balloon early in the PPH treatment algorithm

For postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery, typical initial steps include, as noted, fundal massage, administration of uterotonics, and curettage to remove retained products of conception. If these steps are ineffective, don’t wait: Immediately consider placing a Bakri balloon. Time is precious, and wasting time with less effective interventions results in excessive blood loss and consumption of clotting factors and increases the risk of a coagulopathy.

I’ve found that clinicians often spend too much time trying to determine whether postpartum bleeding originates in the uterus or from a cervical or vaginal laceration. But heavy bleeding can obscure anatomic structures, making it difficult to identify the site of bleeding with precision. Fruitlessly perseverating to differentiate uterine, cervical, and upper vaginal sources of bleeding can waste valuable time and lead to unnecessary blood loss.

By placing a Bakri balloon and inflating it early in the PPH treatment algorithm, you will significantly reduce uterine bleeding. You will also be able to assess the cervix and upper vagina more effectively for lacerations.

My recommendation. Place the Bakri balloon as soon as it is apparent that bleeding is so heavy that you are going to have difficulty assessing the cervix and upper vagina for lacerations. Note that this stands in contrast to the usual recommendation that you assess the cervix and vagina for lacerations before you place the Bakri balloon.

TIP: Have 3 clinicians place the balloon

Teamwork is a key to success here: The Bakri balloon is most quickly and elegantly inserted and inflated when three clinicians team up, as follows:

Clinician#1 scans the uterus, assessing for retained products of conception and providing real-time imaging as the balloon is placed and inflated. This team member provides feedback to the others about correct placement and filling of the balloon.

Clinician#2 inserts the balloon into the uterus by placing her hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position. (Most often, clinician#2 is the delivering clinician.) This technique is performed in a manner similar to how one places an intrauterine pressure catheter.5

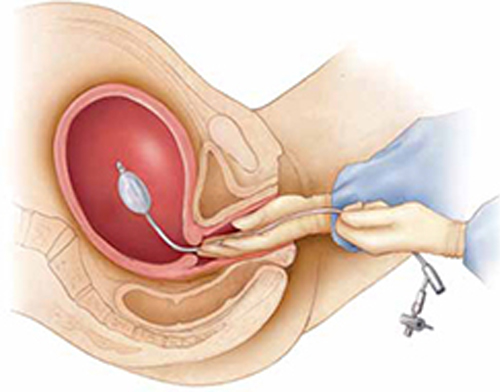

Clinician #2 stabilizes the balloon in position by maintaining her hand in the vagina. She ensures that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled (FIGURE).

Manual insertion of a Bakri balloon

Insert the balloon into the uterus by 1) placing your hand into the vagina and guiding the balloon into the proper intrauterine position (similar to the manner in which an intrauterine pressure catheter is placed),5 2) stabilizing the balloon in position by maintaining the hand in the vagina, and 3) ensuring that the balloon does not “pop” out of the lower uterus as the balloon is filled.Clinician #3 simultaneously begins to instill sterile fluid into the balloon. This team member can be a nurse, medical assistant, or surgical technician.

My recommendation. Consider using simulation training to practice the team approach to placing the Bakri balloon. This is an effective method of improving team coordination.

TIP: Instill at least 150 mL of fluid

In short, use more fluid, not less. Although one study showed that most clinicians fill the balloon to a median volume of 300 mL,6 I’ve observed that some timidly instill the balloon with 80 to 120 mL of fluid. I think this is too little to maximize the effectiveness of the balloon for a postpartum patient who has massive hemorrhage.

Studies have shown that filling the balloon to at least 150 mL noticeably increases tamponade pressure.7

TIP: Place a pack in the upper vagina to stabilize the balloon in position

It usually takes only a few minutes after the Bakri balloon is filled to determine whether it is going to control uterine bleeding—what is called a tamponade test. If the balloon does control bleeding, you can place a vaginal pack of ribbon gauze to help ensure that the balloon does not slip down through the dilated postpartum cervix.

To avoid obscuring continued bleeding, however, do not place vaginal packing until you have obtained a positive tamponade test.

TIP: Check the hemoglobin concentration, platelet count, and coagulation status

The trauma literature demonstrates that optimal patient outcomes are realized when the following targets are maintained during resuscitation of patients who have massive hemorrhage8:

- hematocrit, ≥21%

- platelet count, ≥50 × 103/μL

- fibrinogen ≥100 mg/dL

- International Normalized Ratio (INR) ≤1.5.

These targets are achieved by appropriate transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and purified recombinant fibrinogen concentrate (RiaSTAP). Many trauma specialists recommend transfusion of a 1:1 ratio of RBCs and fresh frozen plasma in cases of major hemorrhage until coagulation status is normalized.

My recommendation. Often, it takes as long as 1 hour (sometimes, longer) to get results of Stat coagulation tests from the lab. While you are waiting, obtain clinical evidence of clotting function by filling a red-top tube with the patient’s blood. Adequate function is signaled by formation of a stable clot within 10 minutes.

TIP: Practice your team’s response to PPH with simulation

Last, I urge clinicians in every birthing unit to use simulation exercises to improve all facets of their response to severe postpartum hemorrhage.9

Summing up

Death following PPH remains a major cause of maternal mortality in developed and developing countries. The appropriateness of your response within 10 minutes of the onset of PPH is critical to ensuring a successful outcome and minimizing adverse events.10 To help, use the Bakri Postpartum Balloon often, and use it early.

What are your tips and tricks for effective use of intra-uterine balloon tamponade in postpartum hemorrhage?

To enter your response, click here or send your pearl to [email protected], with your name and location of practice.

We’ll publish a sampling of bylined contributions in an upcoming issue of OBG Management, with appreciation.

1. Sibai BM. 10 practical evidence-based recommendations for managing severe postpartum hemorrhage. OBG Manage. 2011;23(6):44-48.

2. Barbieri RL. Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor. OBG Manage. 2007;19(05):6-13.

3. Jangsten E, Mattsson LA, Lyckestam I, Hellstrom AL, Berg M. A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2011;118(3):362-369.

4. Barbieri RL. You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatment for OB bleeds. OBG Manage. 2009;21(2):6-10.

5. Dabelea V, Schultze PM, McDuffie RS, Jr. Intrauterine balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24(6):359-364.

6. Vitthala S, Tsoumpou I, Anjum ZK, Aziz NA. Use of Bakri balloon in post-partum hemorrhage: a series of 15 cases. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;49(2):191-194.

7. Georgiou C. Intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of a positive “tamponade test” in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. BJOG. 2010;117(3):295-303.

8. Barbieri RL. Control of massive hemorrhage: Lessons from Iraq reach the US labor and delivery suite. OBG Manage. 2007;19(7):8-16.

9. Skupski DW, Lowenwirt IP, Weinbaum FI, Brodsky D, Danek M, Eglinton GS. Improving hospital systems for the care of women with major obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):977-983.

10. Driessen M, Bouvier-Colle MH, Dupont C, et al. Pithagore6 Group Postpartum hemorrhage resulting from uterine atony after vaginal delivery: factors associated with severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):21-31.

1. Sibai BM. 10 practical evidence-based recommendations for managing severe postpartum hemorrhage. OBG Manage. 2011;23(6):44-48.

2. Barbieri RL. Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor. OBG Manage. 2007;19(05):6-13.

3. Jangsten E, Mattsson LA, Lyckestam I, Hellstrom AL, Berg M. A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2011;118(3):362-369.

4. Barbieri RL. You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatment for OB bleeds. OBG Manage. 2009;21(2):6-10.

5. Dabelea V, Schultze PM, McDuffie RS, Jr. Intrauterine balloon tamponade in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24(6):359-364.

6. Vitthala S, Tsoumpou I, Anjum ZK, Aziz NA. Use of Bakri balloon in post-partum hemorrhage: a series of 15 cases. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;49(2):191-194.

7. Georgiou C. Intraluminal pressure readings during the establishment of a positive “tamponade test” in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. BJOG. 2010;117(3):295-303.

8. Barbieri RL. Control of massive hemorrhage: Lessons from Iraq reach the US labor and delivery suite. OBG Manage. 2007;19(7):8-16.

9. Skupski DW, Lowenwirt IP, Weinbaum FI, Brodsky D, Danek M, Eglinton GS. Improving hospital systems for the care of women with major obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):977-983.

10. Driessen M, Bouvier-Colle MH, Dupont C, et al. Pithagore6 Group Postpartum hemorrhage resulting from uterine atony after vaginal delivery: factors associated with severity. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):21-31.

ACPA-Negative RA Up in First Postpartum Year

Major Finding: During the year following giving birth, women had a statistically significant, 2.4-fold increased risk of incident ACPA-negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women.

Data Source: Case-control study of 1,205 Swedish women enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis study during 1996–2006.

Disclosures: Dr. Bengtsson said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Women who give birth to a child face a twofold increased risk of incident anticitrullinated peptide antibody–negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women, but they have no increased risk for developing ACPA-positive disease, based on results from a Swedish epidemiologic study.

The finding is consistent with a report last year from a Norwegian study that women face about a twofold increased risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during the first 2 years after giving birth to a child, compared with their RA risk 2–4 years post partum (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:332–6). The reason why the new analysis, which included more than 1,200 cases and controls, showed a different relationship between partum and the onset of ACPA-positive RA and ACPA-negative RA remains unclear, according to Camilla Bengtsson, Ph.D.

“Why there is only an association with ACPA-negative disease, and which biological mechanisms are involved remains to be elucidated,” said Dr. Bengtsson, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. The way in which this finding might apply to practice also remains unclear, she added.

Dr. Bengtsson's analysis failed to show an increased incidence of any form of RA in women who were more than a year out from their delivery.

The study used data and blood specimens from Swedish women aged 18–50 years who were enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of RA (EIRA) study during 1996–2006. Among the women with incident RA enrolled in EIRA, 547 (95%) agreed to participate and provide blood specimens, and among the control women in the study, 658 (81%) provided blood. The analysis divided the cases and controls into subgroups based on their partum status. The 547 women with new-onset RA included 360 who had given birth and 187 who had not. The parous women included 226 with ACPA-positive RA and 134 with the ACPA-negative form. Among the nulliparous women with RA, 127 had the ACPA-positive form and 60 were ACPA negative.

Among the controls with no RA, 431 had given birth and 227 had never given birth.

The case-control analysis showed that among all women with incident RA, birth status during the year preceding a new RA diagnosis had no statistically significant relationship with RA onset. However, among women who developed ACPA-negative RA, their risk spiked by a statistically significant, 2.4-fold rate during the year following partum, compared with nulliparous women. In contrast, the incidence of ACPA-positive RA showed no significant relationship to partum status during the preceding year.

Further analysis examined the timing between delivery and onset of ACPA-negative RA more closely. Again, the analysis showed that, during the year following giving birth, women faced a statistically significant, 2.4-fold elevated risk for incident ACPA-negative RA, compared with nulliparous women. During the 2–10 years following giving birth, the rate of incident ACPA-negative RA dropped to a 50% higher risk, compared with nulliparous women, but this difference was not considered statistically significant. And women more than 10 years out from their most recent delivery had a risk for incident ACPA-negative RA identical to the nulliparous women, Dr. Bengtsson reported.

Major Finding: During the year following giving birth, women had a statistically significant, 2.4-fold increased risk of incident ACPA-negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women.

Data Source: Case-control study of 1,205 Swedish women enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis study during 1996–2006.

Disclosures: Dr. Bengtsson said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Women who give birth to a child face a twofold increased risk of incident anticitrullinated peptide antibody–negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women, but they have no increased risk for developing ACPA-positive disease, based on results from a Swedish epidemiologic study.

The finding is consistent with a report last year from a Norwegian study that women face about a twofold increased risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during the first 2 years after giving birth to a child, compared with their RA risk 2–4 years post partum (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:332–6). The reason why the new analysis, which included more than 1,200 cases and controls, showed a different relationship between partum and the onset of ACPA-positive RA and ACPA-negative RA remains unclear, according to Camilla Bengtsson, Ph.D.

“Why there is only an association with ACPA-negative disease, and which biological mechanisms are involved remains to be elucidated,” said Dr. Bengtsson, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. The way in which this finding might apply to practice also remains unclear, she added.

Dr. Bengtsson's analysis failed to show an increased incidence of any form of RA in women who were more than a year out from their delivery.

The study used data and blood specimens from Swedish women aged 18–50 years who were enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of RA (EIRA) study during 1996–2006. Among the women with incident RA enrolled in EIRA, 547 (95%) agreed to participate and provide blood specimens, and among the control women in the study, 658 (81%) provided blood. The analysis divided the cases and controls into subgroups based on their partum status. The 547 women with new-onset RA included 360 who had given birth and 187 who had not. The parous women included 226 with ACPA-positive RA and 134 with the ACPA-negative form. Among the nulliparous women with RA, 127 had the ACPA-positive form and 60 were ACPA negative.

Among the controls with no RA, 431 had given birth and 227 had never given birth.

The case-control analysis showed that among all women with incident RA, birth status during the year preceding a new RA diagnosis had no statistically significant relationship with RA onset. However, among women who developed ACPA-negative RA, their risk spiked by a statistically significant, 2.4-fold rate during the year following partum, compared with nulliparous women. In contrast, the incidence of ACPA-positive RA showed no significant relationship to partum status during the preceding year.

Further analysis examined the timing between delivery and onset of ACPA-negative RA more closely. Again, the analysis showed that, during the year following giving birth, women faced a statistically significant, 2.4-fold elevated risk for incident ACPA-negative RA, compared with nulliparous women. During the 2–10 years following giving birth, the rate of incident ACPA-negative RA dropped to a 50% higher risk, compared with nulliparous women, but this difference was not considered statistically significant. And women more than 10 years out from their most recent delivery had a risk for incident ACPA-negative RA identical to the nulliparous women, Dr. Bengtsson reported.

Major Finding: During the year following giving birth, women had a statistically significant, 2.4-fold increased risk of incident ACPA-negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women.

Data Source: Case-control study of 1,205 Swedish women enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis study during 1996–2006.

Disclosures: Dr. Bengtsson said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Women who give birth to a child face a twofold increased risk of incident anticitrullinated peptide antibody–negative rheumatoid arthritis, compared with nulliparous women, but they have no increased risk for developing ACPA-positive disease, based on results from a Swedish epidemiologic study.

The finding is consistent with a report last year from a Norwegian study that women face about a twofold increased risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during the first 2 years after giving birth to a child, compared with their RA risk 2–4 years post partum (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:332–6). The reason why the new analysis, which included more than 1,200 cases and controls, showed a different relationship between partum and the onset of ACPA-positive RA and ACPA-negative RA remains unclear, according to Camilla Bengtsson, Ph.D.

“Why there is only an association with ACPA-negative disease, and which biological mechanisms are involved remains to be elucidated,” said Dr. Bengtsson, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. The way in which this finding might apply to practice also remains unclear, she added.

Dr. Bengtsson's analysis failed to show an increased incidence of any form of RA in women who were more than a year out from their delivery.

The study used data and blood specimens from Swedish women aged 18–50 years who were enrolled in the Epidemiological Investigation of RA (EIRA) study during 1996–2006. Among the women with incident RA enrolled in EIRA, 547 (95%) agreed to participate and provide blood specimens, and among the control women in the study, 658 (81%) provided blood. The analysis divided the cases and controls into subgroups based on their partum status. The 547 women with new-onset RA included 360 who had given birth and 187 who had not. The parous women included 226 with ACPA-positive RA and 134 with the ACPA-negative form. Among the nulliparous women with RA, 127 had the ACPA-positive form and 60 were ACPA negative.

Among the controls with no RA, 431 had given birth and 227 had never given birth.

The case-control analysis showed that among all women with incident RA, birth status during the year preceding a new RA diagnosis had no statistically significant relationship with RA onset. However, among women who developed ACPA-negative RA, their risk spiked by a statistically significant, 2.4-fold rate during the year following partum, compared with nulliparous women. In contrast, the incidence of ACPA-positive RA showed no significant relationship to partum status during the preceding year.

Further analysis examined the timing between delivery and onset of ACPA-negative RA more closely. Again, the analysis showed that, during the year following giving birth, women faced a statistically significant, 2.4-fold elevated risk for incident ACPA-negative RA, compared with nulliparous women. During the 2–10 years following giving birth, the rate of incident ACPA-negative RA dropped to a 50% higher risk, compared with nulliparous women, but this difference was not considered statistically significant. And women more than 10 years out from their most recent delivery had a risk for incident ACPA-negative RA identical to the nulliparous women, Dr. Bengtsson reported.

From the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology

Unintended Pregnancies Carry Big Price Tag

Taxpayers spend more than $11 billion each year as a result of unintended pregnancies, according to new data from two separate studies.

The estimates are based on public insurance costs for pregnancies and infant care in the first year. Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute used state-level data from 2006 to come up with a national estimate of $11.1 billion in public spending on unintended pregnancies. In a separate study, researchers at the Brookings Institution came up with their figures by using 2001 national data on publicly financed unintended pregnancies, resulting in average spending of $11.3 billion annually. Both studies were published in the June issue of Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health.

Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute found that public programs such as Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program bear the brunt of the nation's costs for unintended pregnancies (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:94–102 [doi:10.1363/4309411]). While 38% of U.S. births result from unintended pregnancies, births from unintended pregnancies make up about half of publicly funded births. But reducing unintended pregnancies also will require major new public investments, the Guttmacher researchers wrote, including increasing access to family planning services and comprehensive sex education. The Affordable Care Act may help, too, they said, by expanding insurance coverage and giving new authority to states to expand Medicaid eligibility for family planning services.

While preventing unintended pregnancies would require an up-front investment, the researchers at the Brookings Institution said it would be more than offset by potential savings. They estimated that if unintended pregnancies could be prevented altogether, with some being delayed until the women were ready to be pregnant, it could save taxpayers about $5.6 billion annually (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:88–93 [doi: 10.1363/4308811]).

Taxpayers spend more than $11 billion each year as a result of unintended pregnancies, according to new data from two separate studies.

The estimates are based on public insurance costs for pregnancies and infant care in the first year. Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute used state-level data from 2006 to come up with a national estimate of $11.1 billion in public spending on unintended pregnancies. In a separate study, researchers at the Brookings Institution came up with their figures by using 2001 national data on publicly financed unintended pregnancies, resulting in average spending of $11.3 billion annually. Both studies were published in the June issue of Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health.

Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute found that public programs such as Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program bear the brunt of the nation's costs for unintended pregnancies (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:94–102 [doi:10.1363/4309411]). While 38% of U.S. births result from unintended pregnancies, births from unintended pregnancies make up about half of publicly funded births. But reducing unintended pregnancies also will require major new public investments, the Guttmacher researchers wrote, including increasing access to family planning services and comprehensive sex education. The Affordable Care Act may help, too, they said, by expanding insurance coverage and giving new authority to states to expand Medicaid eligibility for family planning services.

While preventing unintended pregnancies would require an up-front investment, the researchers at the Brookings Institution said it would be more than offset by potential savings. They estimated that if unintended pregnancies could be prevented altogether, with some being delayed until the women were ready to be pregnant, it could save taxpayers about $5.6 billion annually (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:88–93 [doi: 10.1363/4308811]).

Taxpayers spend more than $11 billion each year as a result of unintended pregnancies, according to new data from two separate studies.

The estimates are based on public insurance costs for pregnancies and infant care in the first year. Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute used state-level data from 2006 to come up with a national estimate of $11.1 billion in public spending on unintended pregnancies. In a separate study, researchers at the Brookings Institution came up with their figures by using 2001 national data on publicly financed unintended pregnancies, resulting in average spending of $11.3 billion annually. Both studies were published in the June issue of Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health.

Researchers from the Guttmacher Institute found that public programs such as Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program bear the brunt of the nation's costs for unintended pregnancies (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:94–102 [doi:10.1363/4309411]). While 38% of U.S. births result from unintended pregnancies, births from unintended pregnancies make up about half of publicly funded births. But reducing unintended pregnancies also will require major new public investments, the Guttmacher researchers wrote, including increasing access to family planning services and comprehensive sex education. The Affordable Care Act may help, too, they said, by expanding insurance coverage and giving new authority to states to expand Medicaid eligibility for family planning services.

While preventing unintended pregnancies would require an up-front investment, the researchers at the Brookings Institution said it would be more than offset by potential savings. They estimated that if unintended pregnancies could be prevented altogether, with some being delayed until the women were ready to be pregnant, it could save taxpayers about $5.6 billion annually (Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2011;43:88–93 [doi: 10.1363/4308811]).

Shoulder Dystocia Protocol Reduces Injuries : The rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury fell by nearly three-fourths in this study.

Major Finding: The rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury in cases of shoulder dystocia fell from 40% before implementation of the Code D protocol to 14% afterward (P less than .01).

Data Source: A retrospective cohort study of 11,862 vaginal deliveries of singleton, live born infants.

Disclosures: Dr. Inglis did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A simple, standardized protocol for managing shoulder dystocia, called Code D, reduced the incidence of obstetric brachial plexus injury, according to a study reported at the meeting.

Investigators retrospectively assessed the impact of the protocol – which entails mobilization of experienced staff, a hands-off pause for assessment, and varied maneuvers – in a cohort of nearly 12,000 vaginal deliveries.

Study results showed that with use of the protocol, the rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury (Erb's palsy) among cases of shoulder dystocia fell by nearly three-fourths, from 40% before the protocol's implementation to 14% afterward.

“A standardized and simple protocol to manage shoulder dystocia appears to reduce the risk of Erb's palsy,” said lead investigator Dr. Steven R. Inglis.

“We were unable to tell which part of the protocol really was helping us,” he added, so further research is needed to determine the responsible components and maneuvers.

Rates of both shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury appear to be on the rise, in part because of increasing maternal obesity and diabetes, as well as increasing fetal macrosomia, according to Dr. Inglis, chairman of the department of ob.gyn. at the Jamaica (N.Y.) Hospital Medical Center.

These complications not only can be associated with long-term morbidity, but also account for a substantial share of obstetricians' liability payouts, according to Dr. Inglis.

Many strategies for managing shoulder dystocia have been introduced, but few of them have been studied to assess their impact on important neonatal outcomes, he said.

Dr. Inglis and his colleagues determined the rate of brachial plexus injury at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center before and after implementation of the Code D shoulder dystocia protocol. The protocol emphasized a stepwise team approach to management, conducted in a calm and relaxed environment.

Code D training was provided to all labor and delivery staff including attending and resident physicians, midwives, and nurses. “I don't think anybody else has really included nurses,” he commented. “I think they were a key part of it.”

Training included didactic presentations followed by hands-on practice with a manikin. “Everybody had to go through shoulder dystocia once or twice and get it done right according to our protocol,” Dr. Inglis explained.

When the staff diagnosed dystocia (tight or difficult shoulders, or the so-called turtle sign requiring additional maneuvers to achieve delivery), they activated the Code D protocol, which summoned to the room the most experienced available obstetrician, and also an anesthesiologist, a neonatologist, and a nurse.

Staff were taught, first, to assess – using a hands-off pause during which there was no maternal pushing, application of fundal pressure, or head traction – the orientation of the infant's back and shoulders, and to announce it to the delivery team.

This hands-off period lasted just a few seconds, according to Dr. Inglis. “You basically want to stop, take a deep breath, collect yourself, make sure you are following the protocol, and then go on.”

Staff then began one of several maneuvers performed in an order of their choice, including rotating the shoulders to the oblique position, changing maternal position, implementing the corkscrew maneuver, and delivering the posterior arm.

“Each should last no longer than 30 seconds, and you could go back to a maneuver if it didn't work the first time,” Dr. Inglis said. Suprapubic pressure also could be used.

To assess the impact of the Code D protocol, the investigators retrospectively reviewed medical records for mothers and their singleton, live born, nonbreech infants delivered vaginally between August 2003 and December 2009. Analyses were based on 6,269 deliveries in the pretraining period before September 2006, and 5,593 deliveries in the posttraining period.

Study results showed that the rate of shoulder dystocia did not differ significantly between periods: This complication occurred in 83 or 1.32% of deliveries in the former period, and in 75 or 1.34% of deliveries in the latter period. However, the percentage of cases of shoulder dystocia that resulted in brachial plexus injury was 40% in the pretraining period, compared with just 14% in the posttraining period.

Among the cases of shoulder dystocia, those in the pretraining period had a higher maternal body mass index (33.4 vs. 30.3 kg/m

But in a logistic regression analysis, use of the shoulder dystocia protocol was still associated with a reduced risk of obstetric brachial plexus injury.

The interval between delivery of the infant's head and body in cases of shoulder dystocia was longer in the posttraining period than in the pretraining period (2.0 minutes vs. 1.5 minutes).

“We wanted everyone to go slowly, so we were actually happy to see that the head-body interval went up,” commented Dr. Inglis. “That certainly didn't seem to worsen the risk of Erb's palsy.”

Study results also showed that staff were more likely to use the Rubin maneuver and posterior arm delivery in the posttraining vs. pretraining period, and were less likely to use the McRoberts maneuver.

Major Finding: The rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury in cases of shoulder dystocia fell from 40% before implementation of the Code D protocol to 14% afterward (P less than .01).

Data Source: A retrospective cohort study of 11,862 vaginal deliveries of singleton, live born infants.

Disclosures: Dr. Inglis did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A simple, standardized protocol for managing shoulder dystocia, called Code D, reduced the incidence of obstetric brachial plexus injury, according to a study reported at the meeting.

Investigators retrospectively assessed the impact of the protocol – which entails mobilization of experienced staff, a hands-off pause for assessment, and varied maneuvers – in a cohort of nearly 12,000 vaginal deliveries.

Study results showed that with use of the protocol, the rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury (Erb's palsy) among cases of shoulder dystocia fell by nearly three-fourths, from 40% before the protocol's implementation to 14% afterward.

“A standardized and simple protocol to manage shoulder dystocia appears to reduce the risk of Erb's palsy,” said lead investigator Dr. Steven R. Inglis.

“We were unable to tell which part of the protocol really was helping us,” he added, so further research is needed to determine the responsible components and maneuvers.

Rates of both shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury appear to be on the rise, in part because of increasing maternal obesity and diabetes, as well as increasing fetal macrosomia, according to Dr. Inglis, chairman of the department of ob.gyn. at the Jamaica (N.Y.) Hospital Medical Center.

These complications not only can be associated with long-term morbidity, but also account for a substantial share of obstetricians' liability payouts, according to Dr. Inglis.

Many strategies for managing shoulder dystocia have been introduced, but few of them have been studied to assess their impact on important neonatal outcomes, he said.

Dr. Inglis and his colleagues determined the rate of brachial plexus injury at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center before and after implementation of the Code D shoulder dystocia protocol. The protocol emphasized a stepwise team approach to management, conducted in a calm and relaxed environment.

Code D training was provided to all labor and delivery staff including attending and resident physicians, midwives, and nurses. “I don't think anybody else has really included nurses,” he commented. “I think they were a key part of it.”

Training included didactic presentations followed by hands-on practice with a manikin. “Everybody had to go through shoulder dystocia once or twice and get it done right according to our protocol,” Dr. Inglis explained.

When the staff diagnosed dystocia (tight or difficult shoulders, or the so-called turtle sign requiring additional maneuvers to achieve delivery), they activated the Code D protocol, which summoned to the room the most experienced available obstetrician, and also an anesthesiologist, a neonatologist, and a nurse.

Staff were taught, first, to assess – using a hands-off pause during which there was no maternal pushing, application of fundal pressure, or head traction – the orientation of the infant's back and shoulders, and to announce it to the delivery team.

This hands-off period lasted just a few seconds, according to Dr. Inglis. “You basically want to stop, take a deep breath, collect yourself, make sure you are following the protocol, and then go on.”

Staff then began one of several maneuvers performed in an order of their choice, including rotating the shoulders to the oblique position, changing maternal position, implementing the corkscrew maneuver, and delivering the posterior arm.

“Each should last no longer than 30 seconds, and you could go back to a maneuver if it didn't work the first time,” Dr. Inglis said. Suprapubic pressure also could be used.

To assess the impact of the Code D protocol, the investigators retrospectively reviewed medical records for mothers and their singleton, live born, nonbreech infants delivered vaginally between August 2003 and December 2009. Analyses were based on 6,269 deliveries in the pretraining period before September 2006, and 5,593 deliveries in the posttraining period.

Study results showed that the rate of shoulder dystocia did not differ significantly between periods: This complication occurred in 83 or 1.32% of deliveries in the former period, and in 75 or 1.34% of deliveries in the latter period. However, the percentage of cases of shoulder dystocia that resulted in brachial plexus injury was 40% in the pretraining period, compared with just 14% in the posttraining period.

Among the cases of shoulder dystocia, those in the pretraining period had a higher maternal body mass index (33.4 vs. 30.3 kg/m

But in a logistic regression analysis, use of the shoulder dystocia protocol was still associated with a reduced risk of obstetric brachial plexus injury.

The interval between delivery of the infant's head and body in cases of shoulder dystocia was longer in the posttraining period than in the pretraining period (2.0 minutes vs. 1.5 minutes).

“We wanted everyone to go slowly, so we were actually happy to see that the head-body interval went up,” commented Dr. Inglis. “That certainly didn't seem to worsen the risk of Erb's palsy.”

Study results also showed that staff were more likely to use the Rubin maneuver and posterior arm delivery in the posttraining vs. pretraining period, and were less likely to use the McRoberts maneuver.

Major Finding: The rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury in cases of shoulder dystocia fell from 40% before implementation of the Code D protocol to 14% afterward (P less than .01).

Data Source: A retrospective cohort study of 11,862 vaginal deliveries of singleton, live born infants.

Disclosures: Dr. Inglis did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A simple, standardized protocol for managing shoulder dystocia, called Code D, reduced the incidence of obstetric brachial plexus injury, according to a study reported at the meeting.

Investigators retrospectively assessed the impact of the protocol – which entails mobilization of experienced staff, a hands-off pause for assessment, and varied maneuvers – in a cohort of nearly 12,000 vaginal deliveries.

Study results showed that with use of the protocol, the rate of obstetric brachial plexus injury (Erb's palsy) among cases of shoulder dystocia fell by nearly three-fourths, from 40% before the protocol's implementation to 14% afterward.

“A standardized and simple protocol to manage shoulder dystocia appears to reduce the risk of Erb's palsy,” said lead investigator Dr. Steven R. Inglis.

“We were unable to tell which part of the protocol really was helping us,” he added, so further research is needed to determine the responsible components and maneuvers.

Rates of both shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury appear to be on the rise, in part because of increasing maternal obesity and diabetes, as well as increasing fetal macrosomia, according to Dr. Inglis, chairman of the department of ob.gyn. at the Jamaica (N.Y.) Hospital Medical Center.

These complications not only can be associated with long-term morbidity, but also account for a substantial share of obstetricians' liability payouts, according to Dr. Inglis.

Many strategies for managing shoulder dystocia have been introduced, but few of them have been studied to assess their impact on important neonatal outcomes, he said.

Dr. Inglis and his colleagues determined the rate of brachial plexus injury at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center before and after implementation of the Code D shoulder dystocia protocol. The protocol emphasized a stepwise team approach to management, conducted in a calm and relaxed environment.

Code D training was provided to all labor and delivery staff including attending and resident physicians, midwives, and nurses. “I don't think anybody else has really included nurses,” he commented. “I think they were a key part of it.”

Training included didactic presentations followed by hands-on practice with a manikin. “Everybody had to go through shoulder dystocia once or twice and get it done right according to our protocol,” Dr. Inglis explained.

When the staff diagnosed dystocia (tight or difficult shoulders, or the so-called turtle sign requiring additional maneuvers to achieve delivery), they activated the Code D protocol, which summoned to the room the most experienced available obstetrician, and also an anesthesiologist, a neonatologist, and a nurse.

Staff were taught, first, to assess – using a hands-off pause during which there was no maternal pushing, application of fundal pressure, or head traction – the orientation of the infant's back and shoulders, and to announce it to the delivery team.

This hands-off period lasted just a few seconds, according to Dr. Inglis. “You basically want to stop, take a deep breath, collect yourself, make sure you are following the protocol, and then go on.”

Staff then began one of several maneuvers performed in an order of their choice, including rotating the shoulders to the oblique position, changing maternal position, implementing the corkscrew maneuver, and delivering the posterior arm.

“Each should last no longer than 30 seconds, and you could go back to a maneuver if it didn't work the first time,” Dr. Inglis said. Suprapubic pressure also could be used.

To assess the impact of the Code D protocol, the investigators retrospectively reviewed medical records for mothers and their singleton, live born, nonbreech infants delivered vaginally between August 2003 and December 2009. Analyses were based on 6,269 deliveries in the pretraining period before September 2006, and 5,593 deliveries in the posttraining period.

Study results showed that the rate of shoulder dystocia did not differ significantly between periods: This complication occurred in 83 or 1.32% of deliveries in the former period, and in 75 or 1.34% of deliveries in the latter period. However, the percentage of cases of shoulder dystocia that resulted in brachial plexus injury was 40% in the pretraining period, compared with just 14% in the posttraining period.

Among the cases of shoulder dystocia, those in the pretraining period had a higher maternal body mass index (33.4 vs. 30.3 kg/m

But in a logistic regression analysis, use of the shoulder dystocia protocol was still associated with a reduced risk of obstetric brachial plexus injury.

The interval between delivery of the infant's head and body in cases of shoulder dystocia was longer in the posttraining period than in the pretraining period (2.0 minutes vs. 1.5 minutes).

“We wanted everyone to go slowly, so we were actually happy to see that the head-body interval went up,” commented Dr. Inglis. “That certainly didn't seem to worsen the risk of Erb's palsy.”

Study results also showed that staff were more likely to use the Rubin maneuver and posterior arm delivery in the posttraining vs. pretraining period, and were less likely to use the McRoberts maneuver.

From the Annual Meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine

Try Vaginal-Perianal GBS Cultures

Major Finding: More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

Data Source: A study of 200 women at least 18 years of age with an average gestational age of 35.9 weeks.

Disclosures: Dr. Trappe reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Vaginal-perianal cultures for group B streptococcus may be a more comfortable option for pregnant women and have comparable accuracy to vaginal-anal cultures, a study of 200 women has shown.

“Vaginal-perianal cultures may be a reasonable, patient-preferred alternative for the recommended vaginal-rectal cultures of GBS during pregnancy,” said Dr. Karen L. Trappe of Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

It's estimated that 10%–30% of pregnant women are colonized with GBS, which is an established cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised universal prenatal screening and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion outlining the collection of GBS cultures between 35 and 37 weeks' gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:1405–12). GBS cultures are to be obtained by a swab of the lower vagina (vaginal introitus) followed by the rectum (insert swab through anal sphincter). This collection method was based on a 1977 study suggesting that the GI tract was the primary site of GBS colonization. However, vaginal-anal cultures are uncomfortable for patients.

Dr. Trappe and her coinvestigators studied whether vaginal-perianal cultures were equally effective in identifying GBS and were more comfortable for patients. They included women in the study if they were at least 18 years old, were to undergo routine GBS culture, and spoke English, Spanish, or Somali. The researchers collected data from 200 patients. The average maternal age was 26 years, and the average gestational age was 35.9 weeks. In terms of ethnicity, half (49%) of patients where white, followed by black (23%), Hispanic (14%), Asian (1%), and other (13%). Although inclusion criteria were for 35–37 weeks' gestation, seven women outside of this range were enrolled – three at 34 weeks', three at 38 weeks', and one at 39 weeks' gestation.

The vaginal-perianal specimen was collected first, followed by the recommended vaginal-rectal specimen. Women were asked to rate pain on a 0–10 scale for each collection method. They also were asked if one method was more uncomfortable than the other. The overall agreement rate between the two collection methods was 96.5%. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

“Patients also reported statistically greater pain and discomfort with the vaginal-rectal culture collection, with over two-thirds of patients reporting less discomfort with the vaginal-perianal method,” Dr. Trappe said at the meeting. More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. “Patients indicated a preference for the vaginal-perianal collection method based on pain and discomfort surveys,” she noted.

Major Finding: More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

Data Source: A study of 200 women at least 18 years of age with an average gestational age of 35.9 weeks.

Disclosures: Dr. Trappe reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Vaginal-perianal cultures for group B streptococcus may be a more comfortable option for pregnant women and have comparable accuracy to vaginal-anal cultures, a study of 200 women has shown.

“Vaginal-perianal cultures may be a reasonable, patient-preferred alternative for the recommended vaginal-rectal cultures of GBS during pregnancy,” said Dr. Karen L. Trappe of Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

It's estimated that 10%–30% of pregnant women are colonized with GBS, which is an established cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised universal prenatal screening and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion outlining the collection of GBS cultures between 35 and 37 weeks' gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:1405–12). GBS cultures are to be obtained by a swab of the lower vagina (vaginal introitus) followed by the rectum (insert swab through anal sphincter). This collection method was based on a 1977 study suggesting that the GI tract was the primary site of GBS colonization. However, vaginal-anal cultures are uncomfortable for patients.

Dr. Trappe and her coinvestigators studied whether vaginal-perianal cultures were equally effective in identifying GBS and were more comfortable for patients. They included women in the study if they were at least 18 years old, were to undergo routine GBS culture, and spoke English, Spanish, or Somali. The researchers collected data from 200 patients. The average maternal age was 26 years, and the average gestational age was 35.9 weeks. In terms of ethnicity, half (49%) of patients where white, followed by black (23%), Hispanic (14%), Asian (1%), and other (13%). Although inclusion criteria were for 35–37 weeks' gestation, seven women outside of this range were enrolled – three at 34 weeks', three at 38 weeks', and one at 39 weeks' gestation.

The vaginal-perianal specimen was collected first, followed by the recommended vaginal-rectal specimen. Women were asked to rate pain on a 0–10 scale for each collection method. They also were asked if one method was more uncomfortable than the other. The overall agreement rate between the two collection methods was 96.5%. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

“Patients also reported statistically greater pain and discomfort with the vaginal-rectal culture collection, with over two-thirds of patients reporting less discomfort with the vaginal-perianal method,” Dr. Trappe said at the meeting. More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. “Patients indicated a preference for the vaginal-perianal collection method based on pain and discomfort surveys,” she noted.

Major Finding: More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

Data Source: A study of 200 women at least 18 years of age with an average gestational age of 35.9 weeks.

Disclosures: Dr. Trappe reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Vaginal-perianal cultures for group B streptococcus may be a more comfortable option for pregnant women and have comparable accuracy to vaginal-anal cultures, a study of 200 women has shown.

“Vaginal-perianal cultures may be a reasonable, patient-preferred alternative for the recommended vaginal-rectal cultures of GBS during pregnancy,” said Dr. Karen L. Trappe of Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

It's estimated that 10%–30% of pregnant women are colonized with GBS, which is an established cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised universal prenatal screening and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a committee opinion outlining the collection of GBS cultures between 35 and 37 weeks' gestation (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:1405–12). GBS cultures are to be obtained by a swab of the lower vagina (vaginal introitus) followed by the rectum (insert swab through anal sphincter). This collection method was based on a 1977 study suggesting that the GI tract was the primary site of GBS colonization. However, vaginal-anal cultures are uncomfortable for patients.

Dr. Trappe and her coinvestigators studied whether vaginal-perianal cultures were equally effective in identifying GBS and were more comfortable for patients. They included women in the study if they were at least 18 years old, were to undergo routine GBS culture, and spoke English, Spanish, or Somali. The researchers collected data from 200 patients. The average maternal age was 26 years, and the average gestational age was 35.9 weeks. In terms of ethnicity, half (49%) of patients where white, followed by black (23%), Hispanic (14%), Asian (1%), and other (13%). Although inclusion criteria were for 35–37 weeks' gestation, seven women outside of this range were enrolled – three at 34 weeks', three at 38 weeks', and one at 39 weeks' gestation.

The vaginal-perianal specimen was collected first, followed by the recommended vaginal-rectal specimen. Women were asked to rate pain on a 0–10 scale for each collection method. They also were asked if one method was more uncomfortable than the other. The overall agreement rate between the two collection methods was 96.5%. The sensitivity and specificity of the vaginal-perianal method were 91% and 99%.

“Patients also reported statistically greater pain and discomfort with the vaginal-rectal culture collection, with over two-thirds of patients reporting less discomfort with the vaginal-perianal method,” Dr. Trappe said at the meeting. More than half (60%) of women reported no pain with the vaginal-perianal method, compared with 18% with the vaginal-rectal method. “Patients indicated a preference for the vaginal-perianal collection method based on pain and discomfort surveys,” she noted.

From the Annual Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Type 2, Gestational Diabetes Are Genetically Linked

WASHINGTON – Most of the gene variations identified thus far as risk factors for type 2 diabetes also appear to increase risk for gestational diabetes – a trend that reaffirms the importance of taking family histories in obstetrical practice, Dr. Alan R. Shuldiner said.

Hundreds of candidate genes for type 2 diabetes have been analyzed in association studies over the past several years, and more recently, whole genome approaches have identified close to 40 genes with variations that increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, he explained at the meeting. Moreover, “most of these genetic variants that have also been looked at in [studies of] gestational diabetes all seem to increase risk there as well.”