User login

Study reveals ‘substantial’ malaria burden in US

Malaria imposes a substantial disease burden in the US, according to researchers.

Their study indicates that malaria hospitalizations and deaths in the US are more common than generally appreciated, as a steady stream of travelers return home with the disease.

In fact, malaria hospitalizations and deaths exceeded hospitalizations and deaths from other travel-related illnesses and generated about half a billion dollars in healthcare costs over a 15-year period.

These findings were published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

“It appears more and more Americans are traveling to areas where malaria is common, and many of them are not taking preventive measures, such as using antimalarial preventive medications and mosquito repellents, even though they are very effective at preventing infections,” said study author Diana Khuu, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

For this study, Dr Khuu and her colleagues looked for malaria patients in a database maintained by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that tracks hospital admissions nationwide.

The researchers found that, between 2000 and 2014, 22,029 people were admitted to US hospitals due to complications from malaria, 4823 patients were diagnosed with severe malaria, and 182 of these patients died.

Most of the deaths and severe disease were linked to infections with the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. However, in almost half of the malaria-related hospitalizations, there was no indication of parasite type.

The majority of malaria hospitalizations occurred in the eastern US in states along the Atlantic seaboard, and men accounted for 60% of the malaria-related hospital admissions.

Malaria hospitalizations were more common in the US than hospitalizations for many other travel-associated diseases. For example, between 2000 and 2014, dengue fever generated an average of 259 hospitalizations a year (compared with 1489 for malaria).

The average cost of treating a malaria patient was $25,789, and the total bill for treating malaria patients in the US from 2000 to 2014 was about $555 million.

The researchers estimated that, each year, there are about 2100 people in the US suffering from malaria, since about 69% require hospital treatment.

That case count would exceed the high end of the official estimate from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of 1500 to 2000 cases per year.

Dr Khuu attributed the difference to the fact that the CDC’s malaria count is based on reports submitted to the agency by hospitals or physicians, and hospital admission records that were used in the current study may capture additional cases that have not been reported to CDC.

While those admissions records did not include travel history, the researchers believe the malaria infections they documented most likely were acquired during travel to parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where malaria is still common.

However, Dr Khuu noted that mosquitoes capable of carrying malaria are common in many parts of the US. So increases in the number of travelers coming home with the disease increases the risk of malaria re-establishing itself in the US. ![]()

Malaria imposes a substantial disease burden in the US, according to researchers.

Their study indicates that malaria hospitalizations and deaths in the US are more common than generally appreciated, as a steady stream of travelers return home with the disease.

In fact, malaria hospitalizations and deaths exceeded hospitalizations and deaths from other travel-related illnesses and generated about half a billion dollars in healthcare costs over a 15-year period.

These findings were published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

“It appears more and more Americans are traveling to areas where malaria is common, and many of them are not taking preventive measures, such as using antimalarial preventive medications and mosquito repellents, even though they are very effective at preventing infections,” said study author Diana Khuu, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

For this study, Dr Khuu and her colleagues looked for malaria patients in a database maintained by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that tracks hospital admissions nationwide.

The researchers found that, between 2000 and 2014, 22,029 people were admitted to US hospitals due to complications from malaria, 4823 patients were diagnosed with severe malaria, and 182 of these patients died.

Most of the deaths and severe disease were linked to infections with the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. However, in almost half of the malaria-related hospitalizations, there was no indication of parasite type.

The majority of malaria hospitalizations occurred in the eastern US in states along the Atlantic seaboard, and men accounted for 60% of the malaria-related hospital admissions.

Malaria hospitalizations were more common in the US than hospitalizations for many other travel-associated diseases. For example, between 2000 and 2014, dengue fever generated an average of 259 hospitalizations a year (compared with 1489 for malaria).

The average cost of treating a malaria patient was $25,789, and the total bill for treating malaria patients in the US from 2000 to 2014 was about $555 million.

The researchers estimated that, each year, there are about 2100 people in the US suffering from malaria, since about 69% require hospital treatment.

That case count would exceed the high end of the official estimate from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of 1500 to 2000 cases per year.

Dr Khuu attributed the difference to the fact that the CDC’s malaria count is based on reports submitted to the agency by hospitals or physicians, and hospital admission records that were used in the current study may capture additional cases that have not been reported to CDC.

While those admissions records did not include travel history, the researchers believe the malaria infections they documented most likely were acquired during travel to parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where malaria is still common.

However, Dr Khuu noted that mosquitoes capable of carrying malaria are common in many parts of the US. So increases in the number of travelers coming home with the disease increases the risk of malaria re-establishing itself in the US. ![]()

Malaria imposes a substantial disease burden in the US, according to researchers.

Their study indicates that malaria hospitalizations and deaths in the US are more common than generally appreciated, as a steady stream of travelers return home with the disease.

In fact, malaria hospitalizations and deaths exceeded hospitalizations and deaths from other travel-related illnesses and generated about half a billion dollars in healthcare costs over a 15-year period.

These findings were published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

“It appears more and more Americans are traveling to areas where malaria is common, and many of them are not taking preventive measures, such as using antimalarial preventive medications and mosquito repellents, even though they are very effective at preventing infections,” said study author Diana Khuu, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

For this study, Dr Khuu and her colleagues looked for malaria patients in a database maintained by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that tracks hospital admissions nationwide.

The researchers found that, between 2000 and 2014, 22,029 people were admitted to US hospitals due to complications from malaria, 4823 patients were diagnosed with severe malaria, and 182 of these patients died.

Most of the deaths and severe disease were linked to infections with the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. However, in almost half of the malaria-related hospitalizations, there was no indication of parasite type.

The majority of malaria hospitalizations occurred in the eastern US in states along the Atlantic seaboard, and men accounted for 60% of the malaria-related hospital admissions.

Malaria hospitalizations were more common in the US than hospitalizations for many other travel-associated diseases. For example, between 2000 and 2014, dengue fever generated an average of 259 hospitalizations a year (compared with 1489 for malaria).

The average cost of treating a malaria patient was $25,789, and the total bill for treating malaria patients in the US from 2000 to 2014 was about $555 million.

The researchers estimated that, each year, there are about 2100 people in the US suffering from malaria, since about 69% require hospital treatment.

That case count would exceed the high end of the official estimate from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of 1500 to 2000 cases per year.

Dr Khuu attributed the difference to the fact that the CDC’s malaria count is based on reports submitted to the agency by hospitals or physicians, and hospital admission records that were used in the current study may capture additional cases that have not been reported to CDC.

While those admissions records did not include travel history, the researchers believe the malaria infections they documented most likely were acquired during travel to parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where malaria is still common.

However, Dr Khuu noted that mosquitoes capable of carrying malaria are common in many parts of the US. So increases in the number of travelers coming home with the disease increases the risk of malaria re-establishing itself in the US. ![]()

Price transparency doesn’t impact ordering of lab tests

Seeing the cost of lab tests in patients’ health records doesn’t deter doctors from ordering the tests, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Results of a large study showed that displaying Medicare allowable fees for inpatient lab tests did not have an overall impact on how clinicians ordered tests.

“Price transparency is increasingly being considered by hospitals and other healthcare organizations as a way to nudge doctors and patients toward higher-value care, but the best way to design these types of interventions has not been well-tested,” said study author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

“Our findings indicate that price transparency alone was not enough to change clinician behavior and that future price transparency interventions may need to be better targeted, framed, or combined with other approaches to be more successful.”

In the new study—the largest of its kind—researchers randomly assigned 60 groups of inpatient lab tests to either display Medicare allowable fees in the patient’s electronic health record (intervention arm) or not (control arm).

The trial was conducted at 3 hospitals within the University of Pennsylvania Health System over a 1-year period. Researchers compared changes in the number of tests ordered per patient per day, and associated fees, for 98,529 patients (totaling 142,921 hospital admissions).

In the year prior to the study, when cost information was not displayed, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day was 2.31 tests, totaling $27.77, in the control group and 3.93 tests, totaling $37.84, in the intervention group.

After the intervention, when cost information was displayed for the intervention group, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day did not change significantly. It was 2.34 tests, totaling $27.59, in the control group, and 4.01 tests, totaling $38.85, in the intervention group.

Though the study showed no overall effect, the researchers noted findings in specific patient groups that have implications for how to improve price transparency in the future.

For example, there was a slight decrease in test ordering for patients admitted to the intensive care unit—an environment in which doctors are making rapid decisions and may be more exposed to the price transparency intervention.

The researchers also found the most expensive tests were ordered less often, and the cheaper tests were ordered more often.

“Electronic health records are constantly being changed, from how choices are offered to the way information is framed,” said study author C. William Hanson, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

“By systematically testing these approaches through real-world experiments, health systems can leverage this new evidence to continue to improve the way care is delivered for our patients.”

“Price transparency continues to be an important initiative,” Dr Patel added, “but the results of this clinical trial indicate that these approaches need to be better designed to effectively change behavior.” ![]()

Seeing the cost of lab tests in patients’ health records doesn’t deter doctors from ordering the tests, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Results of a large study showed that displaying Medicare allowable fees for inpatient lab tests did not have an overall impact on how clinicians ordered tests.

“Price transparency is increasingly being considered by hospitals and other healthcare organizations as a way to nudge doctors and patients toward higher-value care, but the best way to design these types of interventions has not been well-tested,” said study author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

“Our findings indicate that price transparency alone was not enough to change clinician behavior and that future price transparency interventions may need to be better targeted, framed, or combined with other approaches to be more successful.”

In the new study—the largest of its kind—researchers randomly assigned 60 groups of inpatient lab tests to either display Medicare allowable fees in the patient’s electronic health record (intervention arm) or not (control arm).

The trial was conducted at 3 hospitals within the University of Pennsylvania Health System over a 1-year period. Researchers compared changes in the number of tests ordered per patient per day, and associated fees, for 98,529 patients (totaling 142,921 hospital admissions).

In the year prior to the study, when cost information was not displayed, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day was 2.31 tests, totaling $27.77, in the control group and 3.93 tests, totaling $37.84, in the intervention group.

After the intervention, when cost information was displayed for the intervention group, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day did not change significantly. It was 2.34 tests, totaling $27.59, in the control group, and 4.01 tests, totaling $38.85, in the intervention group.

Though the study showed no overall effect, the researchers noted findings in specific patient groups that have implications for how to improve price transparency in the future.

For example, there was a slight decrease in test ordering for patients admitted to the intensive care unit—an environment in which doctors are making rapid decisions and may be more exposed to the price transparency intervention.

The researchers also found the most expensive tests were ordered less often, and the cheaper tests were ordered more often.

“Electronic health records are constantly being changed, from how choices are offered to the way information is framed,” said study author C. William Hanson, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

“By systematically testing these approaches through real-world experiments, health systems can leverage this new evidence to continue to improve the way care is delivered for our patients.”

“Price transparency continues to be an important initiative,” Dr Patel added, “but the results of this clinical trial indicate that these approaches need to be better designed to effectively change behavior.” ![]()

Seeing the cost of lab tests in patients’ health records doesn’t deter doctors from ordering the tests, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Results of a large study showed that displaying Medicare allowable fees for inpatient lab tests did not have an overall impact on how clinicians ordered tests.

“Price transparency is increasingly being considered by hospitals and other healthcare organizations as a way to nudge doctors and patients toward higher-value care, but the best way to design these types of interventions has not been well-tested,” said study author Mitesh S. Patel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

“Our findings indicate that price transparency alone was not enough to change clinician behavior and that future price transparency interventions may need to be better targeted, framed, or combined with other approaches to be more successful.”

In the new study—the largest of its kind—researchers randomly assigned 60 groups of inpatient lab tests to either display Medicare allowable fees in the patient’s electronic health record (intervention arm) or not (control arm).

The trial was conducted at 3 hospitals within the University of Pennsylvania Health System over a 1-year period. Researchers compared changes in the number of tests ordered per patient per day, and associated fees, for 98,529 patients (totaling 142,921 hospital admissions).

In the year prior to the study, when cost information was not displayed, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day was 2.31 tests, totaling $27.77, in the control group and 3.93 tests, totaling $37.84, in the intervention group.

After the intervention, when cost information was displayed for the intervention group, the average number of tests and associated fees ordered per patient per day did not change significantly. It was 2.34 tests, totaling $27.59, in the control group, and 4.01 tests, totaling $38.85, in the intervention group.

Though the study showed no overall effect, the researchers noted findings in specific patient groups that have implications for how to improve price transparency in the future.

For example, there was a slight decrease in test ordering for patients admitted to the intensive care unit—an environment in which doctors are making rapid decisions and may be more exposed to the price transparency intervention.

The researchers also found the most expensive tests were ordered less often, and the cheaper tests were ordered more often.

“Electronic health records are constantly being changed, from how choices are offered to the way information is framed,” said study author C. William Hanson, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

“By systematically testing these approaches through real-world experiments, health systems can leverage this new evidence to continue to improve the way care is delivered for our patients.”

“Price transparency continues to be an important initiative,” Dr Patel added, “but the results of this clinical trial indicate that these approaches need to be better designed to effectively change behavior.” ![]()

How malaria parasites weaken RBCs’ defenses

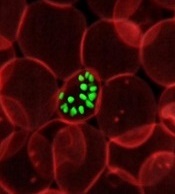

Malaria parasites change the properties of red blood cells (RBCs) in a way that helps the parasites achieve cell entry, according to research published in PNAS.

Researchers found that Plasmodium parasites, upon binding to the surface of RBCs, cause the cell membranes to become more pliable, making it easier for the parasites to push inside the cells.

This suggests that differences in RBC stiffness, due to age or increased cholesterol content, could influence the parasites’ ability to invade.

“We have discovered that red cell entry is not just down to the ability of the parasite itself but that parasite-initiated changes to the red blood cells appear to contribute to the process of invasion,” said study author Marion Koch, a PhD student at Imperial College London in the UK.

“This could also mean that naturally more flexible cells would be easier for parasites to invade, which raises some interesting questions. Are parasites choosy about which cells to invade, picking the most deformable? Is susceptibility to malaria modified by fat or cholesterol content, or the age of circulating red blood cells?”

In the PNAS paper, the researchers noted that erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (EBA175), a protein that’s required for entry in most parasite strains, binds to glycophorin A (GPA) on the RBC surface. However, the function of this binding interaction was unknown.

The team took a closer look at the interaction using real-time deformability cytometry and flicker spectroscopy.

They filmed 1000 RBCs per second passing through a narrow channel. Using this approach, the researchers were able to determine cell deformability by measuring how elongated the cells became during transit through the channel.

The team then measured where this deformation came from. They measured how much the RBCs deviate from their normally circular shape as their membranes naturally fluctuate or flicker.

The researchers found that EBA175 binding to GPA leads to an increase in the cytoskeletal tension of the RBC and a reduction in the bending modulus of the cell’s membrane. (The bending modulus is a measure of how much energy it takes to bend the cell membrane.)

The team then showed that the reduction in the bending modulus was “directly correlated with parasite invasion efficiency.”

The researchers said these results suggest the parasite primes the RBC surface through its binding antigens, altering the cell and reducing a barrier to invasion.

“This suggests we should be investigating not just parasite biology, but also how the body’s own red blood cells respond,” said study author Jake Baum, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“There are therapies developed for diseases like HIV that strengthen the body’s responses in addition to tackling the ‘invader.’ It’s not impossible to imagine something similar for malaria; for example, looking at a host-directed drug target and not just the parasite.” ![]()

Malaria parasites change the properties of red blood cells (RBCs) in a way that helps the parasites achieve cell entry, according to research published in PNAS.

Researchers found that Plasmodium parasites, upon binding to the surface of RBCs, cause the cell membranes to become more pliable, making it easier for the parasites to push inside the cells.

This suggests that differences in RBC stiffness, due to age or increased cholesterol content, could influence the parasites’ ability to invade.

“We have discovered that red cell entry is not just down to the ability of the parasite itself but that parasite-initiated changes to the red blood cells appear to contribute to the process of invasion,” said study author Marion Koch, a PhD student at Imperial College London in the UK.

“This could also mean that naturally more flexible cells would be easier for parasites to invade, which raises some interesting questions. Are parasites choosy about which cells to invade, picking the most deformable? Is susceptibility to malaria modified by fat or cholesterol content, or the age of circulating red blood cells?”

In the PNAS paper, the researchers noted that erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (EBA175), a protein that’s required for entry in most parasite strains, binds to glycophorin A (GPA) on the RBC surface. However, the function of this binding interaction was unknown.

The team took a closer look at the interaction using real-time deformability cytometry and flicker spectroscopy.

They filmed 1000 RBCs per second passing through a narrow channel. Using this approach, the researchers were able to determine cell deformability by measuring how elongated the cells became during transit through the channel.

The team then measured where this deformation came from. They measured how much the RBCs deviate from their normally circular shape as their membranes naturally fluctuate or flicker.

The researchers found that EBA175 binding to GPA leads to an increase in the cytoskeletal tension of the RBC and a reduction in the bending modulus of the cell’s membrane. (The bending modulus is a measure of how much energy it takes to bend the cell membrane.)

The team then showed that the reduction in the bending modulus was “directly correlated with parasite invasion efficiency.”

The researchers said these results suggest the parasite primes the RBC surface through its binding antigens, altering the cell and reducing a barrier to invasion.

“This suggests we should be investigating not just parasite biology, but also how the body’s own red blood cells respond,” said study author Jake Baum, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“There are therapies developed for diseases like HIV that strengthen the body’s responses in addition to tackling the ‘invader.’ It’s not impossible to imagine something similar for malaria; for example, looking at a host-directed drug target and not just the parasite.” ![]()

Malaria parasites change the properties of red blood cells (RBCs) in a way that helps the parasites achieve cell entry, according to research published in PNAS.

Researchers found that Plasmodium parasites, upon binding to the surface of RBCs, cause the cell membranes to become more pliable, making it easier for the parasites to push inside the cells.

This suggests that differences in RBC stiffness, due to age or increased cholesterol content, could influence the parasites’ ability to invade.

“We have discovered that red cell entry is not just down to the ability of the parasite itself but that parasite-initiated changes to the red blood cells appear to contribute to the process of invasion,” said study author Marion Koch, a PhD student at Imperial College London in the UK.

“This could also mean that naturally more flexible cells would be easier for parasites to invade, which raises some interesting questions. Are parasites choosy about which cells to invade, picking the most deformable? Is susceptibility to malaria modified by fat or cholesterol content, or the age of circulating red blood cells?”

In the PNAS paper, the researchers noted that erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (EBA175), a protein that’s required for entry in most parasite strains, binds to glycophorin A (GPA) on the RBC surface. However, the function of this binding interaction was unknown.

The team took a closer look at the interaction using real-time deformability cytometry and flicker spectroscopy.

They filmed 1000 RBCs per second passing through a narrow channel. Using this approach, the researchers were able to determine cell deformability by measuring how elongated the cells became during transit through the channel.

The team then measured where this deformation came from. They measured how much the RBCs deviate from their normally circular shape as their membranes naturally fluctuate or flicker.

The researchers found that EBA175 binding to GPA leads to an increase in the cytoskeletal tension of the RBC and a reduction in the bending modulus of the cell’s membrane. (The bending modulus is a measure of how much energy it takes to bend the cell membrane.)

The team then showed that the reduction in the bending modulus was “directly correlated with parasite invasion efficiency.”

The researchers said these results suggest the parasite primes the RBC surface through its binding antigens, altering the cell and reducing a barrier to invasion.

“This suggests we should be investigating not just parasite biology, but also how the body’s own red blood cells respond,” said study author Jake Baum, PhD, of Imperial College London.

“There are therapies developed for diseases like HIV that strengthen the body’s responses in addition to tackling the ‘invader.’ It’s not impossible to imagine something similar for malaria; for example, looking at a host-directed drug target and not just the parasite.” ![]()

Analysis reveals common sources of bias in scientific research

A recent study suggested that bias in research varies across scientific disciplines, but there are some common factors the different fields share.

The data consistently showed that small studies, early studies, and highly cited studies overestimated effect size.

In addition, a scientist’s early career status, isolation from other researchers, and involvement in misconduct appeared to be risk factors for unreliable results.

John P. A. Ioannidis, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California, and his colleagues reported these findings in PNAS.

The team reviewed more than 3000 meta-analyses that included nearly 50,000 individual studies across 22 scientific fields.

“I think that this is a mapping exercise,” Dr Ioannidis said. “It maps all the main biases that have been proposed across all 22 scientific disciplines. Now, we have a map for each scientific discipline, which biases are important, and which have a bigger impact, and, therefore, scientists can think about where do they want to go next with their field.”

Types of bias

The researchers examined several hypothesized kinds of scientific bias, including:

- Small-study effect: When studies with small sample sizes report large effect sizes.

- Gray literature bias: The tendency of smaller or statistically insignificant effects to be reported in PhD theses, conference proceedings, or personal communications rather than in peer-reviewed literature.

- Early extremes effect: When extreme or controversial findings are published early just because they are astonishing.

- Decline effect: When reports of extreme effects are followed by subsequent reports of reduced effects.

- Citation bias: The larger the effect size, the more likely the study will be cited.

- United States effect: When US researchers overestimate effect sizes.

- Industry bias: When industry sponsorship and affiliation affect the direction and size of reported effects.

Dr Ioannidis and his colleagues also looked at other factors that might potentially affect the risk of bias, such as size and types of collaborations, the gender of the researchers, and pressure to publish.

Results

Small studies, highly cited studies, and those published in peer-reviewed journals seemed more likely to overestimate effects. US studies and early studies seemed to report more extreme effects.

Early career researchers and researchers working in small or long-distance collaborations were more likely to overestimate effect sizes. And researchers with a history of misconduct tended to overestimate effect sizes.

On the other hand, studies by highly cited authors who published frequently were not more affected by bias than average. And there was no difference in bias according to gender.

In addition, scientists in countries with strong incentives to publish were not more affected by bias than scientists from countries where there was less pressure to publish.

Dr Ioannidis said that, in the data he and his colleagues examined, the influence of different kinds of bias changed over time and seemed to depend on the individual scientist.

“We show that some of the patterns and risk factors seem to be getting worse in intensity over time,” he said. “This is particularly driven by the social sciences . . . . It seems that the social sciences are seeing the more prominent worsening of these biases over time.”

Another finding of this study is that the kinds and amounts of bias were irregularly distributed across the literature.

“Although bias may be worryingly high in specific research areas, it is nonexistent in many others,” said study author Daniele Fanelli, PhD, of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University in Palo Alto. “So bias does not undermine the scientific enterprise as a whole.”

Yet another finding is that the relative magnitude of biases closely reflects the level of attention they receive in the literature. That is, the kinds of biases researchers are most concerned about are, in fact, the ones they should be concerned about.

“Our understanding of bias is improving, and our priorities are set on the right targets,” Dr Fanelli said, though he noted that researchers should not become complacent when it comes to bias.

“We perhaps understand bias better, but we are far from having rid science of it. Indeed, our results suggest that the challenge might be greater than many think because interventions might need to be tailored to the needs and problems of individual disciplines of fields. One-size-fits all solutions are unlikely to work.” ![]()

A recent study suggested that bias in research varies across scientific disciplines, but there are some common factors the different fields share.

The data consistently showed that small studies, early studies, and highly cited studies overestimated effect size.

In addition, a scientist’s early career status, isolation from other researchers, and involvement in misconduct appeared to be risk factors for unreliable results.

John P. A. Ioannidis, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California, and his colleagues reported these findings in PNAS.

The team reviewed more than 3000 meta-analyses that included nearly 50,000 individual studies across 22 scientific fields.

“I think that this is a mapping exercise,” Dr Ioannidis said. “It maps all the main biases that have been proposed across all 22 scientific disciplines. Now, we have a map for each scientific discipline, which biases are important, and which have a bigger impact, and, therefore, scientists can think about where do they want to go next with their field.”

Types of bias

The researchers examined several hypothesized kinds of scientific bias, including:

- Small-study effect: When studies with small sample sizes report large effect sizes.

- Gray literature bias: The tendency of smaller or statistically insignificant effects to be reported in PhD theses, conference proceedings, or personal communications rather than in peer-reviewed literature.

- Early extremes effect: When extreme or controversial findings are published early just because they are astonishing.

- Decline effect: When reports of extreme effects are followed by subsequent reports of reduced effects.

- Citation bias: The larger the effect size, the more likely the study will be cited.

- United States effect: When US researchers overestimate effect sizes.

- Industry bias: When industry sponsorship and affiliation affect the direction and size of reported effects.

Dr Ioannidis and his colleagues also looked at other factors that might potentially affect the risk of bias, such as size and types of collaborations, the gender of the researchers, and pressure to publish.

Results

Small studies, highly cited studies, and those published in peer-reviewed journals seemed more likely to overestimate effects. US studies and early studies seemed to report more extreme effects.

Early career researchers and researchers working in small or long-distance collaborations were more likely to overestimate effect sizes. And researchers with a history of misconduct tended to overestimate effect sizes.

On the other hand, studies by highly cited authors who published frequently were not more affected by bias than average. And there was no difference in bias according to gender.

In addition, scientists in countries with strong incentives to publish were not more affected by bias than scientists from countries where there was less pressure to publish.

Dr Ioannidis said that, in the data he and his colleagues examined, the influence of different kinds of bias changed over time and seemed to depend on the individual scientist.

“We show that some of the patterns and risk factors seem to be getting worse in intensity over time,” he said. “This is particularly driven by the social sciences . . . . It seems that the social sciences are seeing the more prominent worsening of these biases over time.”

Another finding of this study is that the kinds and amounts of bias were irregularly distributed across the literature.

“Although bias may be worryingly high in specific research areas, it is nonexistent in many others,” said study author Daniele Fanelli, PhD, of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University in Palo Alto. “So bias does not undermine the scientific enterprise as a whole.”

Yet another finding is that the relative magnitude of biases closely reflects the level of attention they receive in the literature. That is, the kinds of biases researchers are most concerned about are, in fact, the ones they should be concerned about.

“Our understanding of bias is improving, and our priorities are set on the right targets,” Dr Fanelli said, though he noted that researchers should not become complacent when it comes to bias.

“We perhaps understand bias better, but we are far from having rid science of it. Indeed, our results suggest that the challenge might be greater than many think because interventions might need to be tailored to the needs and problems of individual disciplines of fields. One-size-fits all solutions are unlikely to work.” ![]()

A recent study suggested that bias in research varies across scientific disciplines, but there are some common factors the different fields share.

The data consistently showed that small studies, early studies, and highly cited studies overestimated effect size.

In addition, a scientist’s early career status, isolation from other researchers, and involvement in misconduct appeared to be risk factors for unreliable results.

John P. A. Ioannidis, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California, and his colleagues reported these findings in PNAS.

The team reviewed more than 3000 meta-analyses that included nearly 50,000 individual studies across 22 scientific fields.

“I think that this is a mapping exercise,” Dr Ioannidis said. “It maps all the main biases that have been proposed across all 22 scientific disciplines. Now, we have a map for each scientific discipline, which biases are important, and which have a bigger impact, and, therefore, scientists can think about where do they want to go next with their field.”

Types of bias

The researchers examined several hypothesized kinds of scientific bias, including:

- Small-study effect: When studies with small sample sizes report large effect sizes.

- Gray literature bias: The tendency of smaller or statistically insignificant effects to be reported in PhD theses, conference proceedings, or personal communications rather than in peer-reviewed literature.

- Early extremes effect: When extreme or controversial findings are published early just because they are astonishing.

- Decline effect: When reports of extreme effects are followed by subsequent reports of reduced effects.

- Citation bias: The larger the effect size, the more likely the study will be cited.

- United States effect: When US researchers overestimate effect sizes.

- Industry bias: When industry sponsorship and affiliation affect the direction and size of reported effects.

Dr Ioannidis and his colleagues also looked at other factors that might potentially affect the risk of bias, such as size and types of collaborations, the gender of the researchers, and pressure to publish.

Results

Small studies, highly cited studies, and those published in peer-reviewed journals seemed more likely to overestimate effects. US studies and early studies seemed to report more extreme effects.

Early career researchers and researchers working in small or long-distance collaborations were more likely to overestimate effect sizes. And researchers with a history of misconduct tended to overestimate effect sizes.

On the other hand, studies by highly cited authors who published frequently were not more affected by bias than average. And there was no difference in bias according to gender.

In addition, scientists in countries with strong incentives to publish were not more affected by bias than scientists from countries where there was less pressure to publish.

Dr Ioannidis said that, in the data he and his colleagues examined, the influence of different kinds of bias changed over time and seemed to depend on the individual scientist.

“We show that some of the patterns and risk factors seem to be getting worse in intensity over time,” he said. “This is particularly driven by the social sciences . . . . It seems that the social sciences are seeing the more prominent worsening of these biases over time.”

Another finding of this study is that the kinds and amounts of bias were irregularly distributed across the literature.

“Although bias may be worryingly high in specific research areas, it is nonexistent in many others,” said study author Daniele Fanelli, PhD, of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University in Palo Alto. “So bias does not undermine the scientific enterprise as a whole.”

Yet another finding is that the relative magnitude of biases closely reflects the level of attention they receive in the literature. That is, the kinds of biases researchers are most concerned about are, in fact, the ones they should be concerned about.

“Our understanding of bias is improving, and our priorities are set on the right targets,” Dr Fanelli said, though he noted that researchers should not become complacent when it comes to bias.

“We perhaps understand bias better, but we are far from having rid science of it. Indeed, our results suggest that the challenge might be greater than many think because interventions might need to be tailored to the needs and problems of individual disciplines of fields. One-size-fits all solutions are unlikely to work.” ![]()

FDA issues EUA for test to detect Zika virus RNA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Nanobiosym Diagnostics Inc.’s Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus in human serum.

The test should be used on serum samples collected from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) criteria for Zika virus testing.

This includes clinical criteria—such as a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection—and/or epidemiological criteria—such as a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is intended for use in US laboratories that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, to perform high-complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories, pursuant to section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3).

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test should be performed according to the CDC’s algorithm for Zika testing (see http://www.cdc.gov/zika/laboratories/lab-guidance.html).

According to the CDC, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum up to 13 days post-symptom onset in non-pregnant patients, up to 62 days post-symptom onset in pregnant patients, and up to 53 days after the last known possible exposure in an asymptomatic pregnant woman.

About the EUA

The EUA does not mean the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency.

The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

More information on the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Nanobiosym Diagnostics Inc.’s Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus in human serum.

The test should be used on serum samples collected from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) criteria for Zika virus testing.

This includes clinical criteria—such as a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection—and/or epidemiological criteria—such as a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is intended for use in US laboratories that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, to perform high-complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories, pursuant to section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3).

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test should be performed according to the CDC’s algorithm for Zika testing (see http://www.cdc.gov/zika/laboratories/lab-guidance.html).

According to the CDC, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum up to 13 days post-symptom onset in non-pregnant patients, up to 62 days post-symptom onset in pregnant patients, and up to 53 days after the last known possible exposure in an asymptomatic pregnant woman.

About the EUA

The EUA does not mean the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency.

The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

More information on the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Nanobiosym Diagnostics Inc.’s Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus in human serum.

The test should be used on serum samples collected from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) criteria for Zika virus testing.

This includes clinical criteria—such as a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection—and/or epidemiological criteria—such as a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission.

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is intended for use in US laboratories that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, to perform high-complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories, pursuant to section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3).

The Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test should be performed according to the CDC’s algorithm for Zika testing (see http://www.cdc.gov/zika/laboratories/lab-guidance.html).

According to the CDC, Zika virus RNA has been detected in serum up to 13 days post-symptom onset in non-pregnant patients, up to 62 days post-symptom onset in pregnant patients, and up to 53 days after the last known possible exposure in an asymptomatic pregnant woman.

About the EUA

The EUA does not mean the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency.

The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

More information on the Gene-RADAR® Zika Virus Test and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

How stress controls hemoglobin levels in blood

Researchers say they have discovered a new mechanism through which globin genes are expressed.

Their discovery, described in Cell Research, indicates that cellular stress is needed for the production of hemoglobin.

“Surprisingly, we have revealed an entirely new mechanism through which hemoglobin gene expression is regulated by stress,” said study author Raymond Kaempfer, PhD, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

“An intracellular signal, essential for coping with stress, is absolutely necessary to allow for hemoglobin production. That stress signal is activated by the hemoglobin gene itself. Although we have long known that this signal strongly inhibits protein synthesis in general, during hemoglobin gene expression, it first plays its indispensable, positive role before being turned off promptly to allow for massive hemoglobin formation needed for breathing.”

To produce a globin protein molecule, the DNA of the globin gene is first transcribed into a long RNA molecule from which internal segments must be spliced out to generate the RNA template for protein synthesis in the red cell.

The researchers found that, for each of the adult and fetal globin genes, the splicing of its RNA is strictly controlled by an intracellular stress signal.

The signal, which has been known for a long time, involves an enzyme called PKR. This enzyme remains silent unless it is activated by a specific RNA structure thought to occur only in RNA made by viruses.

What the researchers discovered is that the long RNAs transcribed from the globin genes each contain a short intrinsic RNA element that is capable of strongly activating PKR.

Unless the PKR enzyme is activated in this manner, the long RNA cannot be spliced to form the mature RNA template for globin protein synthesis.

Once activated, PKR will place a phosphate onto a key initiation factor needed for the synthesis of all proteins, called eIF2-alpha. That, in turn, leads to inactivation of eIF2-alpha, resulting in a block in protein synthesis. This process is essential for coping with stress.

The researchers discovered that, once activated, PKR must phosphorylate eIF2-alpha, and that phosphorylated eIF2-alpha is essential to form the machinery needed to splice globin RNA.

In the splicing process, removal of an internal RNA segment causes the mature RNA product to refold such that it no longer will activate PKR. This allows for unimpeded synthesis on this RNA of the essential globin protein chains at maximal rates, which allows for effective oxygen breathing.

In other words, the ability to activate PKR remains transient, serving solely to enable splicing.

Thus, the researchers have demonstrated a novel, positive role for PKR activation and eIF2-alpha phosphorylation in human globin RNA splicing, in contrast to the long-standing negative role of this intracellular stress response in protein synthesis.

The realization that stress is essential may have implications for how we understand hemoglobin expression.

“What this boils down to is that, even at the cellular level, stress and the ability to mount a stress response are essential to our survival,” Dr Kaempfer said. “We have long known this in relation to other biological processes, and now we see that it is at play even for the tiny molecules that carry oxygen in our blood.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a new mechanism through which globin genes are expressed.

Their discovery, described in Cell Research, indicates that cellular stress is needed for the production of hemoglobin.

“Surprisingly, we have revealed an entirely new mechanism through which hemoglobin gene expression is regulated by stress,” said study author Raymond Kaempfer, PhD, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

“An intracellular signal, essential for coping with stress, is absolutely necessary to allow for hemoglobin production. That stress signal is activated by the hemoglobin gene itself. Although we have long known that this signal strongly inhibits protein synthesis in general, during hemoglobin gene expression, it first plays its indispensable, positive role before being turned off promptly to allow for massive hemoglobin formation needed for breathing.”

To produce a globin protein molecule, the DNA of the globin gene is first transcribed into a long RNA molecule from which internal segments must be spliced out to generate the RNA template for protein synthesis in the red cell.

The researchers found that, for each of the adult and fetal globin genes, the splicing of its RNA is strictly controlled by an intracellular stress signal.

The signal, which has been known for a long time, involves an enzyme called PKR. This enzyme remains silent unless it is activated by a specific RNA structure thought to occur only in RNA made by viruses.

What the researchers discovered is that the long RNAs transcribed from the globin genes each contain a short intrinsic RNA element that is capable of strongly activating PKR.

Unless the PKR enzyme is activated in this manner, the long RNA cannot be spliced to form the mature RNA template for globin protein synthesis.

Once activated, PKR will place a phosphate onto a key initiation factor needed for the synthesis of all proteins, called eIF2-alpha. That, in turn, leads to inactivation of eIF2-alpha, resulting in a block in protein synthesis. This process is essential for coping with stress.

The researchers discovered that, once activated, PKR must phosphorylate eIF2-alpha, and that phosphorylated eIF2-alpha is essential to form the machinery needed to splice globin RNA.

In the splicing process, removal of an internal RNA segment causes the mature RNA product to refold such that it no longer will activate PKR. This allows for unimpeded synthesis on this RNA of the essential globin protein chains at maximal rates, which allows for effective oxygen breathing.

In other words, the ability to activate PKR remains transient, serving solely to enable splicing.

Thus, the researchers have demonstrated a novel, positive role for PKR activation and eIF2-alpha phosphorylation in human globin RNA splicing, in contrast to the long-standing negative role of this intracellular stress response in protein synthesis.

The realization that stress is essential may have implications for how we understand hemoglobin expression.

“What this boils down to is that, even at the cellular level, stress and the ability to mount a stress response are essential to our survival,” Dr Kaempfer said. “We have long known this in relation to other biological processes, and now we see that it is at play even for the tiny molecules that carry oxygen in our blood.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a new mechanism through which globin genes are expressed.

Their discovery, described in Cell Research, indicates that cellular stress is needed for the production of hemoglobin.

“Surprisingly, we have revealed an entirely new mechanism through which hemoglobin gene expression is regulated by stress,” said study author Raymond Kaempfer, PhD, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

“An intracellular signal, essential for coping with stress, is absolutely necessary to allow for hemoglobin production. That stress signal is activated by the hemoglobin gene itself. Although we have long known that this signal strongly inhibits protein synthesis in general, during hemoglobin gene expression, it first plays its indispensable, positive role before being turned off promptly to allow for massive hemoglobin formation needed for breathing.”

To produce a globin protein molecule, the DNA of the globin gene is first transcribed into a long RNA molecule from which internal segments must be spliced out to generate the RNA template for protein synthesis in the red cell.

The researchers found that, for each of the adult and fetal globin genes, the splicing of its RNA is strictly controlled by an intracellular stress signal.

The signal, which has been known for a long time, involves an enzyme called PKR. This enzyme remains silent unless it is activated by a specific RNA structure thought to occur only in RNA made by viruses.

What the researchers discovered is that the long RNAs transcribed from the globin genes each contain a short intrinsic RNA element that is capable of strongly activating PKR.

Unless the PKR enzyme is activated in this manner, the long RNA cannot be spliced to form the mature RNA template for globin protein synthesis.

Once activated, PKR will place a phosphate onto a key initiation factor needed for the synthesis of all proteins, called eIF2-alpha. That, in turn, leads to inactivation of eIF2-alpha, resulting in a block in protein synthesis. This process is essential for coping with stress.

The researchers discovered that, once activated, PKR must phosphorylate eIF2-alpha, and that phosphorylated eIF2-alpha is essential to form the machinery needed to splice globin RNA.

In the splicing process, removal of an internal RNA segment causes the mature RNA product to refold such that it no longer will activate PKR. This allows for unimpeded synthesis on this RNA of the essential globin protein chains at maximal rates, which allows for effective oxygen breathing.

In other words, the ability to activate PKR remains transient, serving solely to enable splicing.

Thus, the researchers have demonstrated a novel, positive role for PKR activation and eIF2-alpha phosphorylation in human globin RNA splicing, in contrast to the long-standing negative role of this intracellular stress response in protein synthesis.

The realization that stress is essential may have implications for how we understand hemoglobin expression.

“What this boils down to is that, even at the cellular level, stress and the ability to mount a stress response are essential to our survival,” Dr Kaempfer said. “We have long known this in relation to other biological processes, and now we see that it is at play even for the tiny molecules that carry oxygen in our blood.” ![]()

FDA approves drugs more quickly than EMA

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews and approves new medicines in a shorter timeframe than the European Medicines Agency (EMA), according to an analysis published in NEJM.

The FDA has faced pressure from the public, politicians, and industry to accelerate review and approval of new medicines.

The FDA’s review process is currently being considered and reexamined as part of negotiations to reauthorize the law that directs funds to the agency—the Prescription Drug User Fee Act—which is due for reauthorization by October 2017.

To inform this debate, a group of researchers compared review times for new drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA between 2011 and 2015.

The results showed that the FDA approved more new drugs than the EMA—170 versus 144—during this time period.

The median review time was 306 days for FDA-approved drugs and 383 days for EMA-approved drugs (P<0.001).

Over the study period, the FDA approved 53 drugs intended to treat cancer/hematologic diseases, and the EMA approved 50. The median review times were 206 days and 379 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The FDA approved 74 orphan drugs, and the EMA approved 36. The median review times were 294 days and 403 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The current analysis is an update to a prior analysis, published in 2012, which showed the FDA approved new medicines more quickly than the EMA and Health Canada.

“The gap we had identified, where the FDA was 2 to 3 months faster, now it’s about 3 to 4 months faster,” said Joseph Ross, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, an author of both studies.

“This is more information that should inform upcoming debates. The FDA is already making decisions quickly, and increasing its regulatory speed shouldn’t be our number-one priority.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews and approves new medicines in a shorter timeframe than the European Medicines Agency (EMA), according to an analysis published in NEJM.

The FDA has faced pressure from the public, politicians, and industry to accelerate review and approval of new medicines.

The FDA’s review process is currently being considered and reexamined as part of negotiations to reauthorize the law that directs funds to the agency—the Prescription Drug User Fee Act—which is due for reauthorization by October 2017.

To inform this debate, a group of researchers compared review times for new drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA between 2011 and 2015.

The results showed that the FDA approved more new drugs than the EMA—170 versus 144—during this time period.

The median review time was 306 days for FDA-approved drugs and 383 days for EMA-approved drugs (P<0.001).

Over the study period, the FDA approved 53 drugs intended to treat cancer/hematologic diseases, and the EMA approved 50. The median review times were 206 days and 379 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The FDA approved 74 orphan drugs, and the EMA approved 36. The median review times were 294 days and 403 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The current analysis is an update to a prior analysis, published in 2012, which showed the FDA approved new medicines more quickly than the EMA and Health Canada.

“The gap we had identified, where the FDA was 2 to 3 months faster, now it’s about 3 to 4 months faster,” said Joseph Ross, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, an author of both studies.

“This is more information that should inform upcoming debates. The FDA is already making decisions quickly, and increasing its regulatory speed shouldn’t be our number-one priority.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews and approves new medicines in a shorter timeframe than the European Medicines Agency (EMA), according to an analysis published in NEJM.

The FDA has faced pressure from the public, politicians, and industry to accelerate review and approval of new medicines.

The FDA’s review process is currently being considered and reexamined as part of negotiations to reauthorize the law that directs funds to the agency—the Prescription Drug User Fee Act—which is due for reauthorization by October 2017.

To inform this debate, a group of researchers compared review times for new drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA between 2011 and 2015.

The results showed that the FDA approved more new drugs than the EMA—170 versus 144—during this time period.

The median review time was 306 days for FDA-approved drugs and 383 days for EMA-approved drugs (P<0.001).

Over the study period, the FDA approved 53 drugs intended to treat cancer/hematologic diseases, and the EMA approved 50. The median review times were 206 days and 379 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The FDA approved 74 orphan drugs, and the EMA approved 36. The median review times were 294 days and 403 days, respectively (P<0.001).

The current analysis is an update to a prior analysis, published in 2012, which showed the FDA approved new medicines more quickly than the EMA and Health Canada.

“The gap we had identified, where the FDA was 2 to 3 months faster, now it’s about 3 to 4 months faster,” said Joseph Ross, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, an author of both studies.

“This is more information that should inform upcoming debates. The FDA is already making decisions quickly, and increasing its regulatory speed shouldn’t be our number-one priority.”

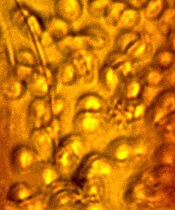

First fossilized mammalian RBCs, Babesia-type pathogens found

An amber specimen found in the Dominican Republic contained the first fossilized mammalian red blood cells (RBCs) and intraerythrocytic hemoparasites, according to an article published in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

The fossil contained an engorged tick and RBCs infected with parasites that resemble existing members of the Babesiidae and Theileriidae families of the order Piroplasmida.

It appears that 2 small holes in the back of the tick allowed blood to ooze out just as the tick became stuck in tree sap that later fossilized into amber.

“These 2 tiny holes indicate that something picked a tick off the mammal it was feeding on, puncturing it in the process and dropping it immediately into tree sap,” said study author George Poinar, Jr, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“This would be consistent with the grooming behavior of monkeys that we know lived at that time in this region. The fossilized blood cells, infected with these parasites, are simply amazing in their detail. This discovery provides the only known fossils of Babesia-type pathogens.”

Dr Poinar said the amber specimen came from mines located in the Cordillera Septentrional of the Dominican Republic. It may have originated anywhere from 15 to 45 million years ago.

The fossil contained an engorged nymphal tick of the genus Ambylomma. The parasites found in the RBCs were also found in the gut epithelial cells and body cavity of the tick.

“The life forms we find in amber can reveal so much about the history and evolution of diseases we still struggle with today,” Dr Poinar said. “This parasite, for instance, was clearly around millions of years before humans and appears to have evolved alongside primates, among other hosts.”

Part of what makes this fossil unique, Dr Poinar said, is the way in which the parasites and RBCs were preserved, almost as if they had been stained and otherwise treated in a lab.

The parasites were different enough in texture and density to stand out clearly within the RBCs during the natural embalming process for which amber is famous.

An amber specimen found in the Dominican Republic contained the first fossilized mammalian red blood cells (RBCs) and intraerythrocytic hemoparasites, according to an article published in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

The fossil contained an engorged tick and RBCs infected with parasites that resemble existing members of the Babesiidae and Theileriidae families of the order Piroplasmida.

It appears that 2 small holes in the back of the tick allowed blood to ooze out just as the tick became stuck in tree sap that later fossilized into amber.

“These 2 tiny holes indicate that something picked a tick off the mammal it was feeding on, puncturing it in the process and dropping it immediately into tree sap,” said study author George Poinar, Jr, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“This would be consistent with the grooming behavior of monkeys that we know lived at that time in this region. The fossilized blood cells, infected with these parasites, are simply amazing in their detail. This discovery provides the only known fossils of Babesia-type pathogens.”

Dr Poinar said the amber specimen came from mines located in the Cordillera Septentrional of the Dominican Republic. It may have originated anywhere from 15 to 45 million years ago.

The fossil contained an engorged nymphal tick of the genus Ambylomma. The parasites found in the RBCs were also found in the gut epithelial cells and body cavity of the tick.

“The life forms we find in amber can reveal so much about the history and evolution of diseases we still struggle with today,” Dr Poinar said. “This parasite, for instance, was clearly around millions of years before humans and appears to have evolved alongside primates, among other hosts.”

Part of what makes this fossil unique, Dr Poinar said, is the way in which the parasites and RBCs were preserved, almost as if they had been stained and otherwise treated in a lab.

The parasites were different enough in texture and density to stand out clearly within the RBCs during the natural embalming process for which amber is famous.

An amber specimen found in the Dominican Republic contained the first fossilized mammalian red blood cells (RBCs) and intraerythrocytic hemoparasites, according to an article published in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

The fossil contained an engorged tick and RBCs infected with parasites that resemble existing members of the Babesiidae and Theileriidae families of the order Piroplasmida.

It appears that 2 small holes in the back of the tick allowed blood to ooze out just as the tick became stuck in tree sap that later fossilized into amber.

“These 2 tiny holes indicate that something picked a tick off the mammal it was feeding on, puncturing it in the process and dropping it immediately into tree sap,” said study author George Poinar, Jr, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“This would be consistent with the grooming behavior of monkeys that we know lived at that time in this region. The fossilized blood cells, infected with these parasites, are simply amazing in their detail. This discovery provides the only known fossils of Babesia-type pathogens.”

Dr Poinar said the amber specimen came from mines located in the Cordillera Septentrional of the Dominican Republic. It may have originated anywhere from 15 to 45 million years ago.

The fossil contained an engorged nymphal tick of the genus Ambylomma. The parasites found in the RBCs were also found in the gut epithelial cells and body cavity of the tick.

“The life forms we find in amber can reveal so much about the history and evolution of diseases we still struggle with today,” Dr Poinar said. “This parasite, for instance, was clearly around millions of years before humans and appears to have evolved alongside primates, among other hosts.”

Part of what makes this fossil unique, Dr Poinar said, is the way in which the parasites and RBCs were preserved, almost as if they had been stained and otherwise treated in a lab.

The parasites were different enough in texture and density to stand out clearly within the RBCs during the natural embalming process for which amber is famous.

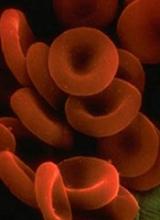

Study provides new insight into RBC resilience

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.

“There is a great deal of evidence that relates certain diseases, including sepsis and malaria, to a decrease in the deformability of red blood cells,” Dr Ito said.

“Such a stiffening can lead to a disturbance in microcirculation, and our ‘catch-load-launch’ platform has the potential to be applied to the mechanical diagnosis of these diseased blood cells.”

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.

“There is a great deal of evidence that relates certain diseases, including sepsis and malaria, to a decrease in the deformability of red blood cells,” Dr Ito said.

“Such a stiffening can lead to a disturbance in microcirculation, and our ‘catch-load-launch’ platform has the potential to be applied to the mechanical diagnosis of these diseased blood cells.”

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.