User login

Postsurgical antibiotics cut infection in obese women after C-section

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41).

Data source: The randomized, placebo-controlled study comprised 403 women.

Disclosures: The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the study. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

VA cohort study: Individualize SSI prophylaxis based on patient factors

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

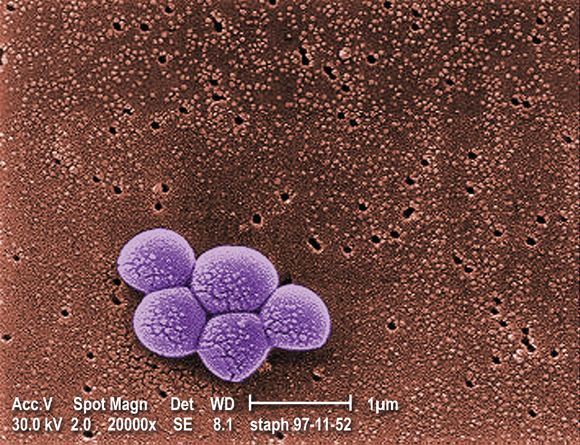

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

The combined use of vancomycin and a beta-lactam antibiotic for prophylaxis against surgical site infections is associated with both benefits and harms, according to findings from a national propensity-score–adjusted retrospective cohort study.

For example, the combination treatment reduced surgical site infections (SSIs) 30 days after cardiac surgical procedures but increased the risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) in some patients, Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, of the VA Boston Healthcare System and her colleagues reported online July 10 in PLOS Medicine.

Among cardiac surgery patients, the incidence of surgical site infections was significantly lower for the 6,953 patients treated with both drugs vs. the 12,834 treated with a single agent (0.95% vs. 1.48%), the investigators found (PLOS Med. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002340).

SSI benefit with combination therapy

“After controlling for age, diabetes, ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] score, mupirocin administration, current smoking status, and preoperative MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] colonization status, receipt of combination antimicrobial prophylaxis was associated with reduced SSI risk following cardiac surgical procedures (adjusted risk ratio, 0.61),” they wrote, noting that, when combination therapy was compared with either of the agents alone, the associations were similar and that no association between SSI reduction and the combination regimen was seen for the other types of surgical procedures assessed.

Secondary analyses showed that, among the cardiac patients, differences in the rates of SSIs were seen based on MRSA status in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Among MRSA-colonized patients, SSIs occurred in 8 of 346 patients (2.3%) who received combination prophylaxis vs. 4 of 100 patients (4%) who received vancomycin alone (aRR, 0.53), and, among MRSA-negative and MRSA-unknown cardiac surgery patients, SSIs occurred in 58 of 6,607 patients (0.88%) receiving combination prophylaxis and 146 of 10,215 patients (1.4%) receiving a beta-lactam alone (aRR, 0.60).

“Among MRSA-colonized patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the associated absolute risk reduction for SSI was approximately triple that of the absolute risk reduction in MRSA-negative or -unknown patients, with a [number needed to treat] to prevent 1 SSI of 53 for the MRSA-colonized group, compared with 176 for the MRSA-negative or -unknown groups,” they wrote.

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was similar in both exposure groups (0.72% and 0.81% with combination and single agent prophylaxis, respectively).

Higher AKI risk with combination therapy

“In contrast, combination versus single prophylaxis was associated with higher relative risk of AKI in the 7-day postoperative period after adjusting for prophylaxis regimen duration, age, diabetes, ASA score, and smoking,” they said.

The rate of AKI was 23.75% among patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% among those receiving vancomycin alone and a beta-lactam alone, respectively.

Significant associations between absolute risk of AKI and receipt of combination regimens were seen across all types of procedures, the investigators said.

“Overall, the NNH [number needed to harm] to cause one episode of AKI in cardiac surgery patients receiving combination therapy was 22, and, for stage 3 AKI, 167. The NNH associated with one additional episode of any postoperative AKI after receipt of combination therapy was 76 following orthopedic procedures and 25 following vascular surgical procedures,” they said.

The optimal approach for preventing SSIs is unclear. Although the multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery recommend single agent prophylaxis most often, with a beta-lactam antibiotic, for most surgical procedures, the use of vancomycin alone is a consideration in MRSA-colonized patients and in centers with a high MRSA incidence, and combination prophylaxis with a beta-lactam plus vancomycin is increasing. However, the relative risks and benefit of this strategy have not been carefully studied, the investigators said.

Thus, the investigators used a propensity-adjusted, log-binomial regression model stratified by type of surgical procedure among the cases identified in the Veterans Affairs cohort to assess the association between SSIs and receipt of combination prophylaxis versus single agent prophylaxis.

Though limited by the observational study design and by factors such as a predominantly male and slightly older and more rural population, the findings suggest that “clinicians may need to individualize prophylaxis strategy based on patient-specific factors that influence the risk-versus-benefit equation,” they said, concluding that “future studies are needed to evaluate the utility of MRSA screening protocols for optimizing and individualizing surgical prophylaxis regimen.”

This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated Grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The SSI incidence was 0.95% vs. 1.48% with combination vs. single agent–therapy in cardiac surgery patients. Acute kidney injuries occurred in 23.75% of all surgery patients receiving combination prophylaxis, compared with 20.79% and 13.93% with vancomycin or a beta-lactam, respectively.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of more than 70,000 surgical procedures.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Branch-Elliman reported having no disclosures. One other author, Eli Perencevich, MD, received an investigator initiated grant from Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2013.

VIDEO: Dual antibiotic prophylaxis cuts cesarean SSIs

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

LAS VEGAS – Two days of prophylaxis with two oral antibiotics cut the surgical site infection rate by more than half in a randomized trial with more than 400 obese women who had cesarean deliveries.

The protective effect from combined treatment with cephalexin and metronidazole was especially powerful in the most at-risk patients, women with ruptured membranes before cesarean surgery. In this subgroup prophylaxis with the two antibiotics for 2 days cut surgical site infections (SSIs) during the 30 days after surgery, from a rate of 33% in control women who received placebo to a 10% rate, a 77% relative risk reduction that was statistically significant, Carri R. Warshak, MD, said at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine.

“I am very excited that we found a way to help the kinds of women in the study, very-high-risk women, with an effective way to reduce their risk of infection,” Dr. Warshak of the University of Cincinnati said in a video interview. The obese women enrolled in the study, especially those with ruptured membranes, “have a very high risk of morbidity, so it’s very exciting that we found a way to help prevent” SSIs.

“Our study is the first to target postpartum interventions to reduce SSIs specifically in this high-risk population” of obese mothers, said Amy M. Valent, DO, a maternal fetal medicine clinician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who ran the trial with Dr. Warshak.

The trial randomized women with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2 who underwent a planned or unplanned cesarean delivery at the University of Cincinnati during 2010-2015. Following standard management during cesarean delivery, the women received either 500 mg oral cephalexin and 500 mg oral metronidazole or placebo every 8 hours for 48 hours following delivery. The primary outcome was the incidence of SSIs, and randomization was stratified so that similar numbers of women with ruptured membranes got into each treatment arm. The enrolled women averaged 28 years of age, and average BMI was about 40 kg/m2. Nearly a third of the women had ruptured membranes at the time of surgery, more than a quarter of the enrolled women used tobacco, and more than a fifth had preeclampsia.

Additional analyses reported at the meeting by Dr. Valent showed that other risk factors that significantly boosted the rate of SSIs were labor prior to delivery, use of internal monitoring, and operative time of more than 90 minutes. Antibiotic prophylaxis was able to significantly reduce SSI rates in women with any of these additional risk factors, compared with placebo. A cost effectiveness analysis she ran estimated that if the antibiotic prophylaxis tested in the study were used on the roughly 460,000 obese U.S. women having cesarean deliveries annually, it would be cost saving as long as the antibiotic regimen cost no more than $357 a person. Factoring in the SSIs and long-term morbidity that prophylaxis would prevent, and the quality-adjusted life-years it would add, showed that prophylaxis would be cost-effective up to a cost of $33,557 per woman.

The prophylaxis carries a “relatively low cost and is easy to use,” Dr. Valent said.

Safety of the antibiotic combination was a question raised by Laura E. Riley, MD, director of ob.gyn. infectious disease and labor and delivery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “My biggest concern is 48 hours of these antibiotics,” and whether prophylaxis could be achieved with fewer doses, she said in an interview. “I’d want to minimize the dosage, and also try other, nondrug approaches to minimizing SSI risk in obese women.”

“I wouldn’t say that universally, every obstetrical program should do this, but clinicians should look at the comorbidities their mothers have and their SSI rates. There are populations out there at lower risk, but there are also populations like ours, with a SSI rate of 10%-20%,” Dr. Warshak said.

She also acknowledged that even her own obstetrical group in Cincinnati needs to now reach a consensus on an appropriate strategy for expanded cesarean-delivery prophylaxis. That’s because a 2016 report from a large, randomized trial documented another successful strategy for limiting infections following cesarean delivery: a preoperative intravenous dose of azithromycin as a supplement to standard cefazolin. The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial, done in women with any BMI but specifically nonelective cesarean deliveries, showed a significant reduction in the combined rate of SSIs, endometritis, or any other infection during 6 weeks of follow-up among women who received azithromycin on top of standard prophylaxis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 29;375[13]:1231-41).

“The bottom line is that, a couple of grams of cefazolin [administered before the incision] isn’t enough, especially for women with risk factors for infection. We see infection rates of more than 10% because cefazolin alone is simply inadequate. The results from both our study and the 2016 study show we can do better to reduce morbidity,” said Dr. Warshak.

“In high-risk women, such as those who are obese, we probably need to expand the spectrum and duration of prophylaxis,” agreed Dr. Main. “Obesity is one high-risk group, but there are others.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Surgical site infections occurred in 7% of women who received oral prophylaxis and 16% of controls during 30-day follow-up.

Data source: A single-center randomized trial with 382 evaluable women.

Disclosures: Dr. Warshak had no relevant disclosures.