User login

Center of Excellence site

FDA panel backs atezolizumab for mTNBC – at least for now

On the first day of a historic 3-day meeting about drugs that were granted an accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration for cancer indications, the first approval to come under discussion is staying in place, at least for now.

Members of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 in favor of keeping in place the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for use in a certain form of breast cancer. At the same time, the committee urged the manufacturer, Genentech, to do the research needed to prove the medicine works for these patients.

The specific indication is for atezolizumab as part of a combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) whose tumors are PD-L1 positive.

The FDA granted accelerated approval in 2019 for this use of atezolizumab, expecting Genentech to produce more extensive evidence of this benefit. But so far, Genentech has not produced the data proving to the FDA that atezolizumab provides the expected benefit.

The drug was already available for use in bladder cancer, having been granted a full approval for this indication in 2016.

Other accelerated approvals withdrawn

This week’s 3-day ODAC meeting is part of the FDA’s broader reconsideration of what it has described as “dangling accelerated approvals.”

Earlier discussions between the FDA and drugmakers have already triggered four voluntary withdrawals of cancer indications with these accelerated approvals, noted Julia A. Beaver, MD, and Richard Pazdur, MD, two of the FDA’s top regulators of oncology medicine, in an April 21 perspective article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The small percentage of drugs whose clinical benefit is ultimately not confirmed should be viewed not as a failure of accelerated approval but rather as an expected trade-off in expediting drug development that benefits patients with severe or life-threatening diseases,” Dr. Beaver and Dr. Pazdur wrote.

But making these calls can be tough. On the first day of the meeting, even ODAC panelists who backed Genentech’s bid to maintain an mTNBC indication for atezolizumab expressed discomfort with this choice.

The FDA granted the accelerated approval for use of this drug in March 2019 based on improved progression-free survival from the IMpassion130 trial. But the drug fell short in subsequent efforts to confirm the results seen in that study. The confirmatory IMpassion131 trial failed to meet the primary endpoint, the FDA staff noted in briefing materials for the ODAC meeting.

ODAC panelist Stan Lipkowitz, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, said he expected this vote had been a tough one for all members serving on ODAC that day.

“In some ways, the purist in me said I should have voted no. But when I looked at the data, there are a couple of things that struck me,” said Dr. Lipkowitz, who is the chief of the Women’s Malignancies Branch at NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. “First of all, the landscape hasn’t changed. There’s really no therapy in the first line for triple-negative metastatic that is shown to improve survival.”

Dr. Lipkowitz emphasized that Genentech needs to continue to try to prove atezolizumab works in this setting.

“There needs to be confirmatory study,” Dr. Lipkowitz concluded.

ODAC panelist Matthew Ellis, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said he also understood the difficult outlook for women fighting this cancer, but he voted against maintaining the approval.

“It’s not that I don’t feel the tragedy of these women,” said Dr. Ellis, citing his own decades of clinical experience.

“I just think that the data are the data,” Dr. Ellis said, adding that, in his view, “the only correct interpretation” of the evidence supported a vote against allowing the indication to stay.

The FDA considers the recommendations of its advisory committees but is not bound by them.

In a statement issued after the vote, Genentech said it intends to work with the FDA to determine the next steps for this indication of atezolizumab because “the clinically meaningful benefit demonstrated in the IMpassion130 study remains.”

The ODAC meeting continues for 2 more days, and will consider five more cancer indications that have been granted an accelerated approval.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On the first day of a historic 3-day meeting about drugs that were granted an accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration for cancer indications, the first approval to come under discussion is staying in place, at least for now.

Members of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 in favor of keeping in place the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for use in a certain form of breast cancer. At the same time, the committee urged the manufacturer, Genentech, to do the research needed to prove the medicine works for these patients.

The specific indication is for atezolizumab as part of a combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) whose tumors are PD-L1 positive.

The FDA granted accelerated approval in 2019 for this use of atezolizumab, expecting Genentech to produce more extensive evidence of this benefit. But so far, Genentech has not produced the data proving to the FDA that atezolizumab provides the expected benefit.

The drug was already available for use in bladder cancer, having been granted a full approval for this indication in 2016.

Other accelerated approvals withdrawn

This week’s 3-day ODAC meeting is part of the FDA’s broader reconsideration of what it has described as “dangling accelerated approvals.”

Earlier discussions between the FDA and drugmakers have already triggered four voluntary withdrawals of cancer indications with these accelerated approvals, noted Julia A. Beaver, MD, and Richard Pazdur, MD, two of the FDA’s top regulators of oncology medicine, in an April 21 perspective article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The small percentage of drugs whose clinical benefit is ultimately not confirmed should be viewed not as a failure of accelerated approval but rather as an expected trade-off in expediting drug development that benefits patients with severe or life-threatening diseases,” Dr. Beaver and Dr. Pazdur wrote.

But making these calls can be tough. On the first day of the meeting, even ODAC panelists who backed Genentech’s bid to maintain an mTNBC indication for atezolizumab expressed discomfort with this choice.

The FDA granted the accelerated approval for use of this drug in March 2019 based on improved progression-free survival from the IMpassion130 trial. But the drug fell short in subsequent efforts to confirm the results seen in that study. The confirmatory IMpassion131 trial failed to meet the primary endpoint, the FDA staff noted in briefing materials for the ODAC meeting.

ODAC panelist Stan Lipkowitz, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, said he expected this vote had been a tough one for all members serving on ODAC that day.

“In some ways, the purist in me said I should have voted no. But when I looked at the data, there are a couple of things that struck me,” said Dr. Lipkowitz, who is the chief of the Women’s Malignancies Branch at NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. “First of all, the landscape hasn’t changed. There’s really no therapy in the first line for triple-negative metastatic that is shown to improve survival.”

Dr. Lipkowitz emphasized that Genentech needs to continue to try to prove atezolizumab works in this setting.

“There needs to be confirmatory study,” Dr. Lipkowitz concluded.

ODAC panelist Matthew Ellis, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said he also understood the difficult outlook for women fighting this cancer, but he voted against maintaining the approval.

“It’s not that I don’t feel the tragedy of these women,” said Dr. Ellis, citing his own decades of clinical experience.

“I just think that the data are the data,” Dr. Ellis said, adding that, in his view, “the only correct interpretation” of the evidence supported a vote against allowing the indication to stay.

The FDA considers the recommendations of its advisory committees but is not bound by them.

In a statement issued after the vote, Genentech said it intends to work with the FDA to determine the next steps for this indication of atezolizumab because “the clinically meaningful benefit demonstrated in the IMpassion130 study remains.”

The ODAC meeting continues for 2 more days, and will consider five more cancer indications that have been granted an accelerated approval.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On the first day of a historic 3-day meeting about drugs that were granted an accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration for cancer indications, the first approval to come under discussion is staying in place, at least for now.

Members of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 in favor of keeping in place the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for use in a certain form of breast cancer. At the same time, the committee urged the manufacturer, Genentech, to do the research needed to prove the medicine works for these patients.

The specific indication is for atezolizumab as part of a combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) whose tumors are PD-L1 positive.

The FDA granted accelerated approval in 2019 for this use of atezolizumab, expecting Genentech to produce more extensive evidence of this benefit. But so far, Genentech has not produced the data proving to the FDA that atezolizumab provides the expected benefit.

The drug was already available for use in bladder cancer, having been granted a full approval for this indication in 2016.

Other accelerated approvals withdrawn

This week’s 3-day ODAC meeting is part of the FDA’s broader reconsideration of what it has described as “dangling accelerated approvals.”

Earlier discussions between the FDA and drugmakers have already triggered four voluntary withdrawals of cancer indications with these accelerated approvals, noted Julia A. Beaver, MD, and Richard Pazdur, MD, two of the FDA’s top regulators of oncology medicine, in an April 21 perspective article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The small percentage of drugs whose clinical benefit is ultimately not confirmed should be viewed not as a failure of accelerated approval but rather as an expected trade-off in expediting drug development that benefits patients with severe or life-threatening diseases,” Dr. Beaver and Dr. Pazdur wrote.

But making these calls can be tough. On the first day of the meeting, even ODAC panelists who backed Genentech’s bid to maintain an mTNBC indication for atezolizumab expressed discomfort with this choice.

The FDA granted the accelerated approval for use of this drug in March 2019 based on improved progression-free survival from the IMpassion130 trial. But the drug fell short in subsequent efforts to confirm the results seen in that study. The confirmatory IMpassion131 trial failed to meet the primary endpoint, the FDA staff noted in briefing materials for the ODAC meeting.

ODAC panelist Stan Lipkowitz, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, said he expected this vote had been a tough one for all members serving on ODAC that day.

“In some ways, the purist in me said I should have voted no. But when I looked at the data, there are a couple of things that struck me,” said Dr. Lipkowitz, who is the chief of the Women’s Malignancies Branch at NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. “First of all, the landscape hasn’t changed. There’s really no therapy in the first line for triple-negative metastatic that is shown to improve survival.”

Dr. Lipkowitz emphasized that Genentech needs to continue to try to prove atezolizumab works in this setting.

“There needs to be confirmatory study,” Dr. Lipkowitz concluded.

ODAC panelist Matthew Ellis, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said he also understood the difficult outlook for women fighting this cancer, but he voted against maintaining the approval.

“It’s not that I don’t feel the tragedy of these women,” said Dr. Ellis, citing his own decades of clinical experience.

“I just think that the data are the data,” Dr. Ellis said, adding that, in his view, “the only correct interpretation” of the evidence supported a vote against allowing the indication to stay.

The FDA considers the recommendations of its advisory committees but is not bound by them.

In a statement issued after the vote, Genentech said it intends to work with the FDA to determine the next steps for this indication of atezolizumab because “the clinically meaningful benefit demonstrated in the IMpassion130 study remains.”

The ODAC meeting continues for 2 more days, and will consider five more cancer indications that have been granted an accelerated approval.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pleural Effusion and an Axillary Mass in a Woman With Hypertension

Editor's Note:

The Case Challenge series includes difficult-to-diagnose conditions, some of which are not frequently encountered by most clinicians but are nonetheless important to accurately recognize. Test your diagnostic and treatment skills using the following patient scenario and corresponding questions. If you have a case that you would like to suggest for a future Case Challenge, please contact us .

Background

A 58-year-old woman seeks medical attention after she discovered a new mass in her left axilla during a routine monthly breast self-examination while showering. She has not noted any changes in either of her breasts. The mass in her left axilla is not tender, and she has not felt any other abnormal masses, including in her right axilla. She reports no other symptoms and specifically has no pain anywhere in her body. She also does not have shortness of breath, fever, night sweats, fatigue, rash, or abdominal discomfort or bloating.

Fifteen years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with high-grade, stage 1 cervical cancer and underwent surgery and chemoradiation. She has been closely monitored since that time with physical examinations and abdominal CT, with no evidence of recurrent disease. The patient has not had any other surgical procedure, except for removal of two basal cell carcinomas on her neck 4 years ago. She has had yearly routine mammograms for at least the past 15 years.

The patient has hypertension, which has been well controlled with the same medications for the past 10 years. She also has a 25-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is currently managed with diet alone. She had a "silent myocardial infarction" sometime within the past 5 years but has had no cardiac symptoms and is not taking any cardiac medications. She smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes a day for less than 2 years when she was "in her teens" but has not had any tobacco products since that time.

Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in the patient's father at age 49 years, and breast cancer was diagnosed in her aunt on her father's side at age 67 years. Her paternal grandmother is reported to have died in her 60s after diagnosis of a "cancer in her stomach." No further information is available regarding either the actual diagnosis or the medical care provided to this individual.

To the best of the patient's knowledge, her mother's side of the family and her two brothers have no history of cancer. She has no sisters. Her mother is in her 80s and has mild dementia. The patient is not aware of any member of her family having undergone genetic testing.

Physical Examination and Workup

The patient appears well and is in no acute distress. The patient is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and a pulse of 72 beats/min. Her weight is 148 lb (67 kg), and she has no reported recent weight loss.

Examination of the skin reveals no suspicious lesions. Scars from the previous removal of the basal cell carcinomas are noted, but no evidence suggests recurrence.

Results of the head and neck examination are unremarkable; specifically, no abnormal cervical lymphadenopathy is detected. The cardiac and chest examination results are normal. The lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation. The breast examination reveals no abnormal masses. The right axilla is unremarkable; however, a single 3 × 2 cm, nontender, firm, movable but partially fixed mass is noted in the left axilla.

The abdomen appears normal, with no ascites or enlargement of the liver. The pelvic examination reveals evidence of previous surgery and local radiation but no signs of recurrence of cervical cancer. The lymph nodes appear normal, except for the findings noted above. Results of the neurologic examination are unremarkable.

Complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte levels, renal function tests, and urinalysis are all normal. Liver function tests are normal except for a mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. The fecal occult blood test result is negative.

Chest radiography reveals a suspicious small left-sided pleural effusion. No other abnormalities are observed, and no prior chest radiographs are available to compare with the current findings.

Chest CT confirms the presence of a possible small pleural effusion, with no other abnormalities noted. The radiologist suggests it will not be possible to obtain fluid safely through an interventional procedure, owing to the limited (if any) amount of fluid present. Furthermore, the radiologist recommends PET/CT to look for other evidence of metastatic cancer in the lungs or elsewhere.

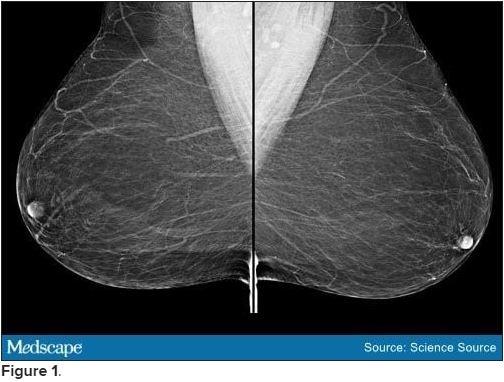

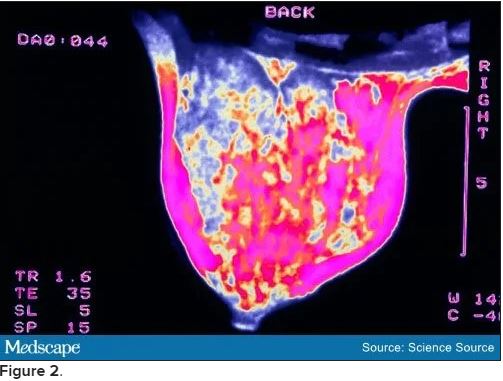

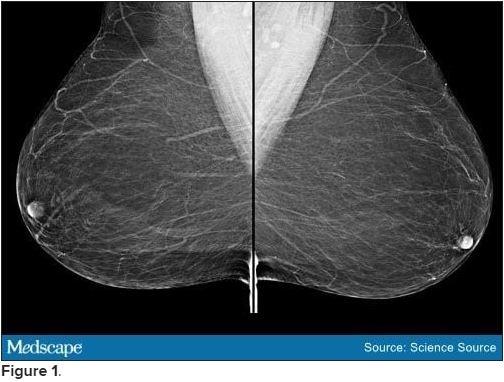

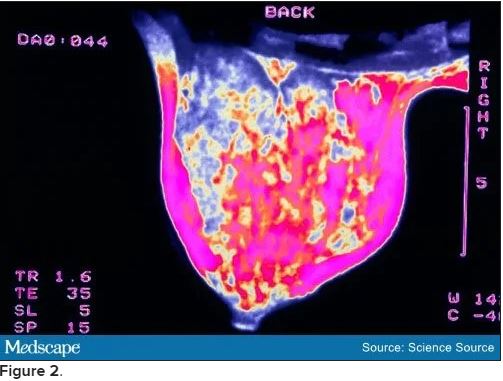

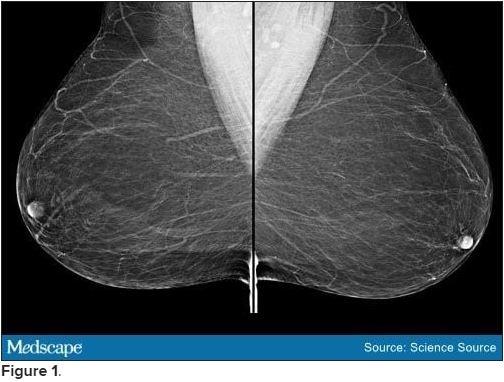

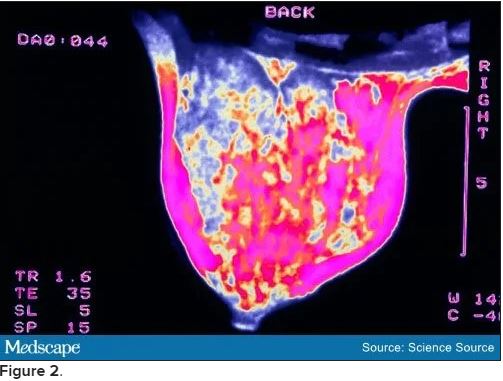

Bilateral mammograms reveal no suspicious abnormalities, and the results are unchanged from a previous examination 11 months earlier. Figure 1 shows a similar bilateral mammogram in another patient. Breast MRI shows no evidence of cancer. Figure 2 shows similar breast MRI findings in another patient.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals no changes compared with a scan obtained 2 years earlier for follow-up of the previous diagnosis of cervical cancer. Specifically, no evidence suggests ascites or any pelvic masses.

An incisional biopsy sample is obtained from the left axillary mass. Light microscopy reveals a moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Immunostaining shows the cancer to be cytokeratin (CK) 7 positive and CK 20 negative (CK 7+/CK 20-, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) negative, thyroglobulin negative, napsin A negative, and mammaglobin positive. The tumor is estrogen receptor positive (2% staining), progesterone receptor negative, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative.

[polldaddy:10837180]

Discussion

The correct answer: Breast.

This case is a classic example of cancer of unknown primary site or origin (CUP). CUP represents approximately 5% of cancers diagnosed in the United States (50,000 to 60,000 cases each year), with various series reporting that the site of origin is not diagnosed in between 2% and 6% of all cancer cases.[1] Worldwide, the incidence of CUP is even higher, resulting from the limited availability of sophisticated (and expensive) diagnostic technology in many regions. The median age at diagnosis of CUP is 60 years, and men and women are equally likely to be affected.

A cancer is considered a CUP if, after routine clinical assessment, physical and laboratory examination, standard imaging studies, and routine pathologic evaluation (biopsy or surgical removal of a metastatic mass lesion), a site of origin cannot be defined. With the availability of more sophisticated imaging technologies (eg, MRI), the overall percentage of cancers that are defined as a CUP has been reduced. However, even at autopsy, the site of origin of such cancer is often unable to be determined if the location was unknown before the patient's death.

Several theories have been proposed for why a metastatic lesion becomes clinically evident despite the site of origin of the cancer remaining obscure. These include (1) very slow growth of the primary cancer compared with that of the metastasis; (2) spontaneous regression of the primary cancer; (3) a prominent vascular component of the cancer, which enhances the rate of spread; and (4) unique molecular events associated with the cancer, which result in rapid progression and the growth of metastatic lesions.

Approximately 60% of CUPs are adenocarcinomas (well or moderately well differentiated); 25%-30% are poorly differentiated (including poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas); 5% are completely undifferentiated, with no defining histologic features; 5% are squamous cell cancers; and approximately 1% are carcinomas, with evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.[1]

Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy material can be helpful in narrowing the possible anatomical sites of origin. The results are particularly relevant in the selection of therapeutic strategies and in ensuring that a rare, potentially highly curable cancer is not missed (eg, lymphoma, germ cell tumor).[2]

A critical initial test is examination of several CK subtypes that are more likely to be expressed in certain carcinomas than in others. For example, the CK 7+/CK 20- staining seen in this patient is characteristic of breast and lung cancers (among others), whereas CK 7+/CK 20+ staining would be expected in pancreatic, gastric, and urothelial cancers. A CK 7-/CK 20+ finding would be more suggestive of colon or mucinous ovarian cancer. Furthermore, approximately 70% of lung adenocarcinomas are TTF-1 positive and 60%-80% are napsin A positive. The negative findings in this patient's case make the diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer less likely.

Examination for the presence (or absence) of well-established biomarkers for breast cancer can potentially be helpful in suggesting the site of origin or in helping to define subsequent therapy. These markers include estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 overexpression. An additional biomarker, mammaglobin, has been reported to be expressed in 48% of breast cancers but is absent in cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, ovary, and head and neck region.[2]

Of note, mammaglobin was found to be expressed in this patient. Although only 2% of the cells were reported to stain for the estrogen receptor, this finding is still considered positive and supports breast cancer as the correct diagnosis.

Recognized relevant prognostic factors in CUP include baseline performance status, the number and location of metastatic lesions, and the response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, the overall prognosis associated with a diagnosis of CUP is poor, with median survival in various series reported to be less than 6 months. However, important exceptions to this outcome include women who present with an isolated metastatic axillary mass, as described in this case.

Previous reports of axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer in women revealed that the majority had evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4] As a result, in the absence of other indications found during routine workup (eg, a single pulmonary lesion suggestive of a primary lung cancer, pathologic findings inconsistent with breast cancer), an isolated adenocarcinoma in the breast (with no evidence of metastatic cancer elsewhere) should be treated as either stage II or stage III breast cancer. Note that this recommendation specifically relates to female patients. If a male patient has CUP with an isolated axillary mass, it is generally assumed that the lung is the origin of the malignancy.

In a female patient with negative mammographic findings, breast MRI can be helpful. In one series, 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram were found to have a breast abnormality on MRI.[5] Of note, and of considerable relevance to subsequent disease management, five of the 12 women with negative findings in this series underwent surgery, and in four of the cases no cancer was found. Although the number of participants in this series is limited, the absence of an MRI abnormality in the patient in this case can reasonably be considered in her future treatment plans.

Specifically, it might be suggested in this case that treatment include surgical removal of the axillary mass (if possible) followed by radiation to this area and the breast (rather than performing a mastectomy). Alternatively, treatment might begin with chemotherapy (a neoadjuvant approach) followed by surgery to remove any residual axillary mass and local/regional radiation or local/regional radiation alone. Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy would then be administered.

The presence of a possible small pleural effusion is a concern because it potentially indicates more widespread metastatic disease, as does the mild elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level (eg, suggesting metastatic disease in bone or the liver). In the absence of other evidence of tumor spread, PET would not be unreasonable. A negative scan for evidence of metastatic disease would support a "curative" approach to the management of local disease in the axilla and presumably the breast, whereas a finding of other metastatic sites would lead to the conclusion that treatment should probably be delivered with more palliative intent.

The family history of cancer (father, paternal aunt with breast cancer, paternal grandmother with possible ovarian cancer) is intriguing and would suggest a role for genetic counseling and possibly genetic testing (eg, for BRCA mutation).

The patient in this case underwent PET. The only abnormality observed was in the left axilla. The axillary mass was subsequently resected. This was followed by curative radiation to both the axilla and left breast, adjuvant chemotherapy, and 5 years of hormonal therapy. The patient has showed no evidence of recurrence 2 years after completion of the hormonal treatment.

[polldaddy:10841207]

Discussion

The correct answer: Lung

The lungs are generally assumed to be the site of origin of the cancer in a male patient who has CUP with an isolated axillary mass. In contrast, the majority of women with axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer were found to have evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4]

[polldaddy:10837187]

Discussion

The correct answer: MRI

Breast MRI can be helpful in a female patient with negative mammographic findings. In one series, MRI detected a breast abnormality in 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram.[5]

Editor's Note:

The Case Challenge series includes difficult-to-diagnose conditions, some of which are not frequently encountered by most clinicians but are nonetheless important to accurately recognize. Test your diagnostic and treatment skills using the following patient scenario and corresponding questions. If you have a case that you would like to suggest for a future Case Challenge, please contact us .

Background

A 58-year-old woman seeks medical attention after she discovered a new mass in her left axilla during a routine monthly breast self-examination while showering. She has not noted any changes in either of her breasts. The mass in her left axilla is not tender, and she has not felt any other abnormal masses, including in her right axilla. She reports no other symptoms and specifically has no pain anywhere in her body. She also does not have shortness of breath, fever, night sweats, fatigue, rash, or abdominal discomfort or bloating.

Fifteen years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with high-grade, stage 1 cervical cancer and underwent surgery and chemoradiation. She has been closely monitored since that time with physical examinations and abdominal CT, with no evidence of recurrent disease. The patient has not had any other surgical procedure, except for removal of two basal cell carcinomas on her neck 4 years ago. She has had yearly routine mammograms for at least the past 15 years.

The patient has hypertension, which has been well controlled with the same medications for the past 10 years. She also has a 25-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is currently managed with diet alone. She had a "silent myocardial infarction" sometime within the past 5 years but has had no cardiac symptoms and is not taking any cardiac medications. She smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes a day for less than 2 years when she was "in her teens" but has not had any tobacco products since that time.

Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in the patient's father at age 49 years, and breast cancer was diagnosed in her aunt on her father's side at age 67 years. Her paternal grandmother is reported to have died in her 60s after diagnosis of a "cancer in her stomach." No further information is available regarding either the actual diagnosis or the medical care provided to this individual.

To the best of the patient's knowledge, her mother's side of the family and her two brothers have no history of cancer. She has no sisters. Her mother is in her 80s and has mild dementia. The patient is not aware of any member of her family having undergone genetic testing.

Physical Examination and Workup

The patient appears well and is in no acute distress. The patient is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and a pulse of 72 beats/min. Her weight is 148 lb (67 kg), and she has no reported recent weight loss.

Examination of the skin reveals no suspicious lesions. Scars from the previous removal of the basal cell carcinomas are noted, but no evidence suggests recurrence.

Results of the head and neck examination are unremarkable; specifically, no abnormal cervical lymphadenopathy is detected. The cardiac and chest examination results are normal. The lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation. The breast examination reveals no abnormal masses. The right axilla is unremarkable; however, a single 3 × 2 cm, nontender, firm, movable but partially fixed mass is noted in the left axilla.

The abdomen appears normal, with no ascites or enlargement of the liver. The pelvic examination reveals evidence of previous surgery and local radiation but no signs of recurrence of cervical cancer. The lymph nodes appear normal, except for the findings noted above. Results of the neurologic examination are unremarkable.

Complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte levels, renal function tests, and urinalysis are all normal. Liver function tests are normal except for a mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. The fecal occult blood test result is negative.

Chest radiography reveals a suspicious small left-sided pleural effusion. No other abnormalities are observed, and no prior chest radiographs are available to compare with the current findings.

Chest CT confirms the presence of a possible small pleural effusion, with no other abnormalities noted. The radiologist suggests it will not be possible to obtain fluid safely through an interventional procedure, owing to the limited (if any) amount of fluid present. Furthermore, the radiologist recommends PET/CT to look for other evidence of metastatic cancer in the lungs or elsewhere.

Bilateral mammograms reveal no suspicious abnormalities, and the results are unchanged from a previous examination 11 months earlier. Figure 1 shows a similar bilateral mammogram in another patient. Breast MRI shows no evidence of cancer. Figure 2 shows similar breast MRI findings in another patient.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals no changes compared with a scan obtained 2 years earlier for follow-up of the previous diagnosis of cervical cancer. Specifically, no evidence suggests ascites or any pelvic masses.

An incisional biopsy sample is obtained from the left axillary mass. Light microscopy reveals a moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Immunostaining shows the cancer to be cytokeratin (CK) 7 positive and CK 20 negative (CK 7+/CK 20-, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) negative, thyroglobulin negative, napsin A negative, and mammaglobin positive. The tumor is estrogen receptor positive (2% staining), progesterone receptor negative, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative.

[polldaddy:10837180]

Discussion

The correct answer: Breast.

This case is a classic example of cancer of unknown primary site or origin (CUP). CUP represents approximately 5% of cancers diagnosed in the United States (50,000 to 60,000 cases each year), with various series reporting that the site of origin is not diagnosed in between 2% and 6% of all cancer cases.[1] Worldwide, the incidence of CUP is even higher, resulting from the limited availability of sophisticated (and expensive) diagnostic technology in many regions. The median age at diagnosis of CUP is 60 years, and men and women are equally likely to be affected.

A cancer is considered a CUP if, after routine clinical assessment, physical and laboratory examination, standard imaging studies, and routine pathologic evaluation (biopsy or surgical removal of a metastatic mass lesion), a site of origin cannot be defined. With the availability of more sophisticated imaging technologies (eg, MRI), the overall percentage of cancers that are defined as a CUP has been reduced. However, even at autopsy, the site of origin of such cancer is often unable to be determined if the location was unknown before the patient's death.

Several theories have been proposed for why a metastatic lesion becomes clinically evident despite the site of origin of the cancer remaining obscure. These include (1) very slow growth of the primary cancer compared with that of the metastasis; (2) spontaneous regression of the primary cancer; (3) a prominent vascular component of the cancer, which enhances the rate of spread; and (4) unique molecular events associated with the cancer, which result in rapid progression and the growth of metastatic lesions.

Approximately 60% of CUPs are adenocarcinomas (well or moderately well differentiated); 25%-30% are poorly differentiated (including poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas); 5% are completely undifferentiated, with no defining histologic features; 5% are squamous cell cancers; and approximately 1% are carcinomas, with evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.[1]

Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy material can be helpful in narrowing the possible anatomical sites of origin. The results are particularly relevant in the selection of therapeutic strategies and in ensuring that a rare, potentially highly curable cancer is not missed (eg, lymphoma, germ cell tumor).[2]

A critical initial test is examination of several CK subtypes that are more likely to be expressed in certain carcinomas than in others. For example, the CK 7+/CK 20- staining seen in this patient is characteristic of breast and lung cancers (among others), whereas CK 7+/CK 20+ staining would be expected in pancreatic, gastric, and urothelial cancers. A CK 7-/CK 20+ finding would be more suggestive of colon or mucinous ovarian cancer. Furthermore, approximately 70% of lung adenocarcinomas are TTF-1 positive and 60%-80% are napsin A positive. The negative findings in this patient's case make the diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer less likely.

Examination for the presence (or absence) of well-established biomarkers for breast cancer can potentially be helpful in suggesting the site of origin or in helping to define subsequent therapy. These markers include estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 overexpression. An additional biomarker, mammaglobin, has been reported to be expressed in 48% of breast cancers but is absent in cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, ovary, and head and neck region.[2]

Of note, mammaglobin was found to be expressed in this patient. Although only 2% of the cells were reported to stain for the estrogen receptor, this finding is still considered positive and supports breast cancer as the correct diagnosis.

Recognized relevant prognostic factors in CUP include baseline performance status, the number and location of metastatic lesions, and the response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, the overall prognosis associated with a diagnosis of CUP is poor, with median survival in various series reported to be less than 6 months. However, important exceptions to this outcome include women who present with an isolated metastatic axillary mass, as described in this case.

Previous reports of axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer in women revealed that the majority had evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4] As a result, in the absence of other indications found during routine workup (eg, a single pulmonary lesion suggestive of a primary lung cancer, pathologic findings inconsistent with breast cancer), an isolated adenocarcinoma in the breast (with no evidence of metastatic cancer elsewhere) should be treated as either stage II or stage III breast cancer. Note that this recommendation specifically relates to female patients. If a male patient has CUP with an isolated axillary mass, it is generally assumed that the lung is the origin of the malignancy.

In a female patient with negative mammographic findings, breast MRI can be helpful. In one series, 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram were found to have a breast abnormality on MRI.[5] Of note, and of considerable relevance to subsequent disease management, five of the 12 women with negative findings in this series underwent surgery, and in four of the cases no cancer was found. Although the number of participants in this series is limited, the absence of an MRI abnormality in the patient in this case can reasonably be considered in her future treatment plans.

Specifically, it might be suggested in this case that treatment include surgical removal of the axillary mass (if possible) followed by radiation to this area and the breast (rather than performing a mastectomy). Alternatively, treatment might begin with chemotherapy (a neoadjuvant approach) followed by surgery to remove any residual axillary mass and local/regional radiation or local/regional radiation alone. Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy would then be administered.

The presence of a possible small pleural effusion is a concern because it potentially indicates more widespread metastatic disease, as does the mild elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level (eg, suggesting metastatic disease in bone or the liver). In the absence of other evidence of tumor spread, PET would not be unreasonable. A negative scan for evidence of metastatic disease would support a "curative" approach to the management of local disease in the axilla and presumably the breast, whereas a finding of other metastatic sites would lead to the conclusion that treatment should probably be delivered with more palliative intent.

The family history of cancer (father, paternal aunt with breast cancer, paternal grandmother with possible ovarian cancer) is intriguing and would suggest a role for genetic counseling and possibly genetic testing (eg, for BRCA mutation).

The patient in this case underwent PET. The only abnormality observed was in the left axilla. The axillary mass was subsequently resected. This was followed by curative radiation to both the axilla and left breast, adjuvant chemotherapy, and 5 years of hormonal therapy. The patient has showed no evidence of recurrence 2 years after completion of the hormonal treatment.

[polldaddy:10841207]

Discussion

The correct answer: Lung

The lungs are generally assumed to be the site of origin of the cancer in a male patient who has CUP with an isolated axillary mass. In contrast, the majority of women with axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer were found to have evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4]

[polldaddy:10837187]

Discussion

The correct answer: MRI

Breast MRI can be helpful in a female patient with negative mammographic findings. In one series, MRI detected a breast abnormality in 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram.[5]

Editor's Note:

The Case Challenge series includes difficult-to-diagnose conditions, some of which are not frequently encountered by most clinicians but are nonetheless important to accurately recognize. Test your diagnostic and treatment skills using the following patient scenario and corresponding questions. If you have a case that you would like to suggest for a future Case Challenge, please contact us .

Background

A 58-year-old woman seeks medical attention after she discovered a new mass in her left axilla during a routine monthly breast self-examination while showering. She has not noted any changes in either of her breasts. The mass in her left axilla is not tender, and she has not felt any other abnormal masses, including in her right axilla. She reports no other symptoms and specifically has no pain anywhere in her body. She also does not have shortness of breath, fever, night sweats, fatigue, rash, or abdominal discomfort or bloating.

Fifteen years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with high-grade, stage 1 cervical cancer and underwent surgery and chemoradiation. She has been closely monitored since that time with physical examinations and abdominal CT, with no evidence of recurrent disease. The patient has not had any other surgical procedure, except for removal of two basal cell carcinomas on her neck 4 years ago. She has had yearly routine mammograms for at least the past 15 years.

The patient has hypertension, which has been well controlled with the same medications for the past 10 years. She also has a 25-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is currently managed with diet alone. She had a "silent myocardial infarction" sometime within the past 5 years but has had no cardiac symptoms and is not taking any cardiac medications. She smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes a day for less than 2 years when she was "in her teens" but has not had any tobacco products since that time.

Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in the patient's father at age 49 years, and breast cancer was diagnosed in her aunt on her father's side at age 67 years. Her paternal grandmother is reported to have died in her 60s after diagnosis of a "cancer in her stomach." No further information is available regarding either the actual diagnosis or the medical care provided to this individual.

To the best of the patient's knowledge, her mother's side of the family and her two brothers have no history of cancer. She has no sisters. Her mother is in her 80s and has mild dementia. The patient is not aware of any member of her family having undergone genetic testing.

Physical Examination and Workup

The patient appears well and is in no acute distress. The patient is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and a pulse of 72 beats/min. Her weight is 148 lb (67 kg), and she has no reported recent weight loss.

Examination of the skin reveals no suspicious lesions. Scars from the previous removal of the basal cell carcinomas are noted, but no evidence suggests recurrence.

Results of the head and neck examination are unremarkable; specifically, no abnormal cervical lymphadenopathy is detected. The cardiac and chest examination results are normal. The lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation. The breast examination reveals no abnormal masses. The right axilla is unremarkable; however, a single 3 × 2 cm, nontender, firm, movable but partially fixed mass is noted in the left axilla.

The abdomen appears normal, with no ascites or enlargement of the liver. The pelvic examination reveals evidence of previous surgery and local radiation but no signs of recurrence of cervical cancer. The lymph nodes appear normal, except for the findings noted above. Results of the neurologic examination are unremarkable.

Complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte levels, renal function tests, and urinalysis are all normal. Liver function tests are normal except for a mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. The fecal occult blood test result is negative.

Chest radiography reveals a suspicious small left-sided pleural effusion. No other abnormalities are observed, and no prior chest radiographs are available to compare with the current findings.

Chest CT confirms the presence of a possible small pleural effusion, with no other abnormalities noted. The radiologist suggests it will not be possible to obtain fluid safely through an interventional procedure, owing to the limited (if any) amount of fluid present. Furthermore, the radiologist recommends PET/CT to look for other evidence of metastatic cancer in the lungs or elsewhere.

Bilateral mammograms reveal no suspicious abnormalities, and the results are unchanged from a previous examination 11 months earlier. Figure 1 shows a similar bilateral mammogram in another patient. Breast MRI shows no evidence of cancer. Figure 2 shows similar breast MRI findings in another patient.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals no changes compared with a scan obtained 2 years earlier for follow-up of the previous diagnosis of cervical cancer. Specifically, no evidence suggests ascites or any pelvic masses.

An incisional biopsy sample is obtained from the left axillary mass. Light microscopy reveals a moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Immunostaining shows the cancer to be cytokeratin (CK) 7 positive and CK 20 negative (CK 7+/CK 20-, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) negative, thyroglobulin negative, napsin A negative, and mammaglobin positive. The tumor is estrogen receptor positive (2% staining), progesterone receptor negative, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative.

[polldaddy:10837180]

Discussion

The correct answer: Breast.

This case is a classic example of cancer of unknown primary site or origin (CUP). CUP represents approximately 5% of cancers diagnosed in the United States (50,000 to 60,000 cases each year), with various series reporting that the site of origin is not diagnosed in between 2% and 6% of all cancer cases.[1] Worldwide, the incidence of CUP is even higher, resulting from the limited availability of sophisticated (and expensive) diagnostic technology in many regions. The median age at diagnosis of CUP is 60 years, and men and women are equally likely to be affected.

A cancer is considered a CUP if, after routine clinical assessment, physical and laboratory examination, standard imaging studies, and routine pathologic evaluation (biopsy or surgical removal of a metastatic mass lesion), a site of origin cannot be defined. With the availability of more sophisticated imaging technologies (eg, MRI), the overall percentage of cancers that are defined as a CUP has been reduced. However, even at autopsy, the site of origin of such cancer is often unable to be determined if the location was unknown before the patient's death.

Several theories have been proposed for why a metastatic lesion becomes clinically evident despite the site of origin of the cancer remaining obscure. These include (1) very slow growth of the primary cancer compared with that of the metastasis; (2) spontaneous regression of the primary cancer; (3) a prominent vascular component of the cancer, which enhances the rate of spread; and (4) unique molecular events associated with the cancer, which result in rapid progression and the growth of metastatic lesions.

Approximately 60% of CUPs are adenocarcinomas (well or moderately well differentiated); 25%-30% are poorly differentiated (including poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas); 5% are completely undifferentiated, with no defining histologic features; 5% are squamous cell cancers; and approximately 1% are carcinomas, with evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.[1]

Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy material can be helpful in narrowing the possible anatomical sites of origin. The results are particularly relevant in the selection of therapeutic strategies and in ensuring that a rare, potentially highly curable cancer is not missed (eg, lymphoma, germ cell tumor).[2]

A critical initial test is examination of several CK subtypes that are more likely to be expressed in certain carcinomas than in others. For example, the CK 7+/CK 20- staining seen in this patient is characteristic of breast and lung cancers (among others), whereas CK 7+/CK 20+ staining would be expected in pancreatic, gastric, and urothelial cancers. A CK 7-/CK 20+ finding would be more suggestive of colon or mucinous ovarian cancer. Furthermore, approximately 70% of lung adenocarcinomas are TTF-1 positive and 60%-80% are napsin A positive. The negative findings in this patient's case make the diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer less likely.

Examination for the presence (or absence) of well-established biomarkers for breast cancer can potentially be helpful in suggesting the site of origin or in helping to define subsequent therapy. These markers include estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 overexpression. An additional biomarker, mammaglobin, has been reported to be expressed in 48% of breast cancers but is absent in cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, ovary, and head and neck region.[2]

Of note, mammaglobin was found to be expressed in this patient. Although only 2% of the cells were reported to stain for the estrogen receptor, this finding is still considered positive and supports breast cancer as the correct diagnosis.

Recognized relevant prognostic factors in CUP include baseline performance status, the number and location of metastatic lesions, and the response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, the overall prognosis associated with a diagnosis of CUP is poor, with median survival in various series reported to be less than 6 months. However, important exceptions to this outcome include women who present with an isolated metastatic axillary mass, as described in this case.

Previous reports of axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer in women revealed that the majority had evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4] As a result, in the absence of other indications found during routine workup (eg, a single pulmonary lesion suggestive of a primary lung cancer, pathologic findings inconsistent with breast cancer), an isolated adenocarcinoma in the breast (with no evidence of metastatic cancer elsewhere) should be treated as either stage II or stage III breast cancer. Note that this recommendation specifically relates to female patients. If a male patient has CUP with an isolated axillary mass, it is generally assumed that the lung is the origin of the malignancy.

In a female patient with negative mammographic findings, breast MRI can be helpful. In one series, 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram were found to have a breast abnormality on MRI.[5] Of note, and of considerable relevance to subsequent disease management, five of the 12 women with negative findings in this series underwent surgery, and in four of the cases no cancer was found. Although the number of participants in this series is limited, the absence of an MRI abnormality in the patient in this case can reasonably be considered in her future treatment plans.

Specifically, it might be suggested in this case that treatment include surgical removal of the axillary mass (if possible) followed by radiation to this area and the breast (rather than performing a mastectomy). Alternatively, treatment might begin with chemotherapy (a neoadjuvant approach) followed by surgery to remove any residual axillary mass and local/regional radiation or local/regional radiation alone. Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy would then be administered.

The presence of a possible small pleural effusion is a concern because it potentially indicates more widespread metastatic disease, as does the mild elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level (eg, suggesting metastatic disease in bone or the liver). In the absence of other evidence of tumor spread, PET would not be unreasonable. A negative scan for evidence of metastatic disease would support a "curative" approach to the management of local disease in the axilla and presumably the breast, whereas a finding of other metastatic sites would lead to the conclusion that treatment should probably be delivered with more palliative intent.

The family history of cancer (father, paternal aunt with breast cancer, paternal grandmother with possible ovarian cancer) is intriguing and would suggest a role for genetic counseling and possibly genetic testing (eg, for BRCA mutation).

The patient in this case underwent PET. The only abnormality observed was in the left axilla. The axillary mass was subsequently resected. This was followed by curative radiation to both the axilla and left breast, adjuvant chemotherapy, and 5 years of hormonal therapy. The patient has showed no evidence of recurrence 2 years after completion of the hormonal treatment.

[polldaddy:10841207]

Discussion

The correct answer: Lung

The lungs are generally assumed to be the site of origin of the cancer in a male patient who has CUP with an isolated axillary mass. In contrast, the majority of women with axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer were found to have evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4]

[polldaddy:10837187]

Discussion

The correct answer: MRI

Breast MRI can be helpful in a female patient with negative mammographic findings. In one series, MRI detected a breast abnormality in 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram.[5]

Cell-free DNA improves response prediction in breast cancer

When the two techniques were in agreement, the accuracy of response prediction was 92.6% in the study, with a predictive value for complete response of 87.5% and a predictive value for absence of complete response of 94.7%, which was substantially better than either method alone.

“Our work identifies a new parameter that is easily combinable with MRI for a more accurate prediction of response following neoadjuvant treatment, with possible implications for current protocols for the evaluation of nodal residual disease,” researcher Francesco Ravera, MD, PhD, of the University of Genoa (Italy), said in a press release.

Dr. Ravera and colleagues presented their research in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract LB063).

Accurate response prediction is important because it guides subsequent surgical management, Dr. Ravera and colleagues noted. Pathological complete responders – generally about 25% of patients after neoadjuvant therapy – typically undergo a sentinel lymph node biopsy to ensure cancer hasn’t spread, while incomplete responders often have a complete axillary lymph node dissection.

Response is currently assessed by MRI, but accuracy is suboptimal, the researchers noted. A more accurate method might “allow the omission of sentinel lymph node biopsy in complete responders, which could be replaced by longitudinal radiologic monitoring. This would represent substantial progress in the pursuit of an effective, minimally invasive treatment,” Dr. Ravera said.

He and his colleagues turned to plasma cfDNA because it has shown potential for providing useful diagnostic, recurrence, and treatment response information in neoplastic patients.

When healthy cells die, they release similarly sized DNA fragments into the blood, but cancer cells release fragments of varying sizes. The heart of the research was using electrophoresis to assess the degree of fragmentation – called cfDNA integrity – in plasma samples from 38 patients after anthracycline/taxane-based regimens.

The researchers compared how well cfDNA, preoperative MRI, and the combination of the two methods predicted response according to surgical histology.

A total of 11 patients had pathological complete responses to neoadjuvant therapy.

The ratio of large 321-1,000 base pair sized fragments to smaller 150-220 base pair sized fragments, which the team dubbed the “cfDNA integrity index,” best predicted response. At a cutoff above 2.71, the index was 81.6% accurate in predicting pathological complete response, with a sensitivity of 81.8% and specificity of 81.5%.

The predictive power wasn’t much better than MRI, which was 77.1% accurate, with a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 81.5%.

The two techniques were concordant in their prediction in over two-thirds of patients. When the techniques agreed, accuracy was over 90%.

Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the cfDNA integrity index in combination with MRI, the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the University of Genoa and others. Dr. Ravera disclosed no conflicts of interest.

When the two techniques were in agreement, the accuracy of response prediction was 92.6% in the study, with a predictive value for complete response of 87.5% and a predictive value for absence of complete response of 94.7%, which was substantially better than either method alone.

“Our work identifies a new parameter that is easily combinable with MRI for a more accurate prediction of response following neoadjuvant treatment, with possible implications for current protocols for the evaluation of nodal residual disease,” researcher Francesco Ravera, MD, PhD, of the University of Genoa (Italy), said in a press release.

Dr. Ravera and colleagues presented their research in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract LB063).

Accurate response prediction is important because it guides subsequent surgical management, Dr. Ravera and colleagues noted. Pathological complete responders – generally about 25% of patients after neoadjuvant therapy – typically undergo a sentinel lymph node biopsy to ensure cancer hasn’t spread, while incomplete responders often have a complete axillary lymph node dissection.

Response is currently assessed by MRI, but accuracy is suboptimal, the researchers noted. A more accurate method might “allow the omission of sentinel lymph node biopsy in complete responders, which could be replaced by longitudinal radiologic monitoring. This would represent substantial progress in the pursuit of an effective, minimally invasive treatment,” Dr. Ravera said.

He and his colleagues turned to plasma cfDNA because it has shown potential for providing useful diagnostic, recurrence, and treatment response information in neoplastic patients.

When healthy cells die, they release similarly sized DNA fragments into the blood, but cancer cells release fragments of varying sizes. The heart of the research was using electrophoresis to assess the degree of fragmentation – called cfDNA integrity – in plasma samples from 38 patients after anthracycline/taxane-based regimens.

The researchers compared how well cfDNA, preoperative MRI, and the combination of the two methods predicted response according to surgical histology.

A total of 11 patients had pathological complete responses to neoadjuvant therapy.

The ratio of large 321-1,000 base pair sized fragments to smaller 150-220 base pair sized fragments, which the team dubbed the “cfDNA integrity index,” best predicted response. At a cutoff above 2.71, the index was 81.6% accurate in predicting pathological complete response, with a sensitivity of 81.8% and specificity of 81.5%.

The predictive power wasn’t much better than MRI, which was 77.1% accurate, with a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 81.5%.

The two techniques were concordant in their prediction in over two-thirds of patients. When the techniques agreed, accuracy was over 90%.

Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the cfDNA integrity index in combination with MRI, the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the University of Genoa and others. Dr. Ravera disclosed no conflicts of interest.

When the two techniques were in agreement, the accuracy of response prediction was 92.6% in the study, with a predictive value for complete response of 87.5% and a predictive value for absence of complete response of 94.7%, which was substantially better than either method alone.

“Our work identifies a new parameter that is easily combinable with MRI for a more accurate prediction of response following neoadjuvant treatment, with possible implications for current protocols for the evaluation of nodal residual disease,” researcher Francesco Ravera, MD, PhD, of the University of Genoa (Italy), said in a press release.

Dr. Ravera and colleagues presented their research in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract LB063).

Accurate response prediction is important because it guides subsequent surgical management, Dr. Ravera and colleagues noted. Pathological complete responders – generally about 25% of patients after neoadjuvant therapy – typically undergo a sentinel lymph node biopsy to ensure cancer hasn’t spread, while incomplete responders often have a complete axillary lymph node dissection.

Response is currently assessed by MRI, but accuracy is suboptimal, the researchers noted. A more accurate method might “allow the omission of sentinel lymph node biopsy in complete responders, which could be replaced by longitudinal radiologic monitoring. This would represent substantial progress in the pursuit of an effective, minimally invasive treatment,” Dr. Ravera said.

He and his colleagues turned to plasma cfDNA because it has shown potential for providing useful diagnostic, recurrence, and treatment response information in neoplastic patients.

When healthy cells die, they release similarly sized DNA fragments into the blood, but cancer cells release fragments of varying sizes. The heart of the research was using electrophoresis to assess the degree of fragmentation – called cfDNA integrity – in plasma samples from 38 patients after anthracycline/taxane-based regimens.

The researchers compared how well cfDNA, preoperative MRI, and the combination of the two methods predicted response according to surgical histology.

A total of 11 patients had pathological complete responses to neoadjuvant therapy.

The ratio of large 321-1,000 base pair sized fragments to smaller 150-220 base pair sized fragments, which the team dubbed the “cfDNA integrity index,” best predicted response. At a cutoff above 2.71, the index was 81.6% accurate in predicting pathological complete response, with a sensitivity of 81.8% and specificity of 81.5%.

The predictive power wasn’t much better than MRI, which was 77.1% accurate, with a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 81.5%.

The two techniques were concordant in their prediction in over two-thirds of patients. When the techniques agreed, accuracy was over 90%.

Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the cfDNA integrity index in combination with MRI, the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the University of Genoa and others. Dr. Ravera disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM AACR 2021

Treating metastatic TNBC: Where are we now?

Treating triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), one of the more lethal breast cancer subtypes, remains a challenge. By definition, TNBC lacks the three telltale molecular signatures known to spur tumor growth: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). A growing amount of literature shows that these frequently aggressive tumors harbor a rich array of molecular characteristics but no clear oncogenic driver.

“TNBC is incredibly heterogeneous, which makes it challenging to treat,” said Rita Nanda, MD, director of the breast oncology program and associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. “We have subsets of TNBC that don’t respond to currently available therapies and, as of yet, have no identifiable therapeutic targets.”

Overall, about 40% of patients with TNBC show a pathologic complete response after first-line neoadjuvant chemotherapy – typically anthracycline and taxane-based agents. But for 50% of patients, chemotherapy leaves behind substantial residual cancer tissue. These patients subsequently face a 40%-80% risk for recurrence and progression to advanced disease.

When triple-negative disease metastasizes, survival rates plummet. The most recent data from the National Cancer Institute, which tracked patients by stage of diagnosis between 2010 and 2016, showed steep declines in 5-year survival as TNBC progressed from local (91.2%) to regional (65%) to advanced-stage disease (11.5%).

Experts have started to make headway identifying and targeting different molecular features of advanced TNBC. These approaches often focus on three key areas: targeting cell surface proteins or oncogenes, stimulating an anticancer immune response, or inhibiting an overactive signaling pathway.

“For a patient with metastatic breast cancer, finding a molecular target or an oncogenic driver is essential,” said Kelly McCann, MD, PhD, a hematologist/oncologist in the department of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Because TNBC encompasses many different molecular subsets of breast cancer, the development of effective new therapeutics is going to depend on subdividing TNBC into categories with more clear targets.”

A targeted strategy

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of sacituzumab govitecan, the first antibody-drug conjugate to treat metastatic TNBC, marked an important addition to the TNBC drug armamentarium. “Sacituzumab govitecan is one of the most exciting drugs available for the treatment of metastatic disease,” Dr. Nanda said.

Sacituzumab govitecan, approved as third-line therapy for metastatic TNBC, works by targeting the cell surface protein TROP2, expressed in about 88% of TNBC tumors but rarely in healthy cells.

In the phase 1/2 ASCENT trial, the median progression-free survival was 5.5 months and overall survival was 13.0 months in 108 patients with metastatic TNBC who had received at least two therapies prior to sacituzumab govitecan.

A subsequent phase 3 trial showed progression-free survival of 5.6 months with sacituzumab govitecan and 1.7 months with physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median overall survival was 12.1 months and 6.7 months, respectively.

But, according to the analysis, TROP2 expression did not necessarily predict who would benefit from sacituzumab govitecan. A biomarker study revealed that although patients with moderate to high TROP2 expression exhibited the strongest treatment response, those with low TROP2 expression also survived longer when given sacituzumab govitecan, compared with chemotherapy alone.

In other words, “patients did better on sacituzumab govitecan regardless of TROP2 expression, which suggests we do not have a good biomarker for identifying who will benefit,” Dr. Nanda said.

Two other investigational antibody-drug conjugates, trastuzumab deruxtecan and ladiratuzumab vedotin, show promise in the metastatic space as well. For instance, the recent phase 2 trial evaluating trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer reported treatment response in 44% of patients with HER2-low tumors.

Given that about 36.6% of TNBC tumors exhibit low levels of HER2 expression, “trastuzumab deruxtecan represents potential in treating HER2-low TNBC,” said Yuan Yuan, MD, PhD, medical oncologist at City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer center in Los Angeles County.

Early results from a phase 1b study showed that trastuzumab deruxtecan produced a response rate of 37% in patients with HER2-low breast cancer.

Investigators are now recruiting for an open-label phase 3 trial to determine whether trastuzumab deruxtecan extends survival in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancers.

Immunotherapy advances

Immune checkpoint inhibitors represent another promising treatment avenue for metastatic TNBC. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, recently approved by the FDA, show moderate progression-free and overall survival benefits in patients with metastatic TNBC expressing PD-L1. Estimates of PD-L1 immune cells present in TNBC tumors vary widely, from about 20% to 65%.

Yet, data on which patients will benefit are not so clear-cut. “These drugs give us more choices and represent the fast-evolving therapeutic landscape in TNBC, but they also leave a lot of unanswered questions about PD-L1 as a biomarker,” Dr. Yuan said.

Take two recent phase 3 trials evaluating atezolizumab: IMpassion130 and IMpassion131. In IMpassion130, patients with PDL1–positive tumors exhibited significantly longer median overall survival on atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel (25.0 months) compared with nab-paclitaxel alone (15.5 months). As with the trend observed in the TROP2 data for sacituzumab govitecan, all patients survived longer on atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel regardless of PD-L1 status: 21.3 months vs. 17.6 months with nab-paclitaxel alone.

However, in IMpassion131, neither progression-free survival nor overall survival significantly improved in the PD-L1–positive group receiving atezolizumab plus paclitaxel compared with paclitaxel alone: Progression-free survival was 5.7 months vs. 6 months, respectively, and overall survival was 28.3 months vs. 22.1 months.

“It is unclear why this study failed to demonstrate a significant improvement in progression-free survival with the addition of atezolizumab to paclitaxel,” Dr. Nanda said. “Perhaps the negative finding has to do with how the trial was conducted, or perhaps the PD-L1 assay used is an unreliable biomarker of immunotherapy benefit.”

Continued efforts to understand TNBC

Given the diversity of metastatic TNBC and the absence of clear molecular targets, researchers are exploring a host of therapeutic strategies in addition to antibody-drug conjugates and immunotherapies.

On the oncogene front, researchers are investigating common mutations in TNBC. About 11% of TNBC tumors, for instance, carry germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. These tumors may be more likely to respond to platinum agents and PARP inhibitors, such as FDA-approved olaparib. In a phase 3 trial, patients with metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation who received olaparib exhibited a 2.8-month longer median progression-free survival and a 42% reduced risk for disease progression or death compared with those on standard chemotherapy.

When considering signaling pathways, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been the target of numerous clinical trials. Dysregulation of signaling through the PI3K and AKT signaling pathway occurs in 25%-30% of patients with advanced TNBC, and AKT inhibitors have been shown to extend survival in these patients. Data show, for instance, that adding capivasertib to first-line paclitaxel therapy in patients with metastatic TNBC led to longer overall survival – 19.1 months vs. 12.6 with placebo plus paclitaxel – with better survival results in patients with PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN altered tumors.

But there’s more to learn about treating metastatic TNBC. “Relapses tend to occur early in TNBC, and some tumors are inherently resistant to chemotherapy from the get-go,” said Charles Shapiro, MD, medical oncologist, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Understanding the causes of drug response and resistance in patients with metastatic TNBC represents the holy grail.”

Dr. Nanda agreed, noting that advancing treatments for TNBC will hinge on identifying the key factors driving metastasis. “For TNBC, we are still trying to elucidate the best molecular targets, while at the same time trying to identify robust biomarkers to predict benefit from therapies we already have available,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), one of the more lethal breast cancer subtypes, remains a challenge. By definition, TNBC lacks the three telltale molecular signatures known to spur tumor growth: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). A growing amount of literature shows that these frequently aggressive tumors harbor a rich array of molecular characteristics but no clear oncogenic driver.

“TNBC is incredibly heterogeneous, which makes it challenging to treat,” said Rita Nanda, MD, director of the breast oncology program and associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. “We have subsets of TNBC that don’t respond to currently available therapies and, as of yet, have no identifiable therapeutic targets.”

Overall, about 40% of patients with TNBC show a pathologic complete response after first-line neoadjuvant chemotherapy – typically anthracycline and taxane-based agents. But for 50% of patients, chemotherapy leaves behind substantial residual cancer tissue. These patients subsequently face a 40%-80% risk for recurrence and progression to advanced disease.

When triple-negative disease metastasizes, survival rates plummet. The most recent data from the National Cancer Institute, which tracked patients by stage of diagnosis between 2010 and 2016, showed steep declines in 5-year survival as TNBC progressed from local (91.2%) to regional (65%) to advanced-stage disease (11.5%).

Experts have started to make headway identifying and targeting different molecular features of advanced TNBC. These approaches often focus on three key areas: targeting cell surface proteins or oncogenes, stimulating an anticancer immune response, or inhibiting an overactive signaling pathway.

“For a patient with metastatic breast cancer, finding a molecular target or an oncogenic driver is essential,” said Kelly McCann, MD, PhD, a hematologist/oncologist in the department of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Because TNBC encompasses many different molecular subsets of breast cancer, the development of effective new therapeutics is going to depend on subdividing TNBC into categories with more clear targets.”

A targeted strategy

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of sacituzumab govitecan, the first antibody-drug conjugate to treat metastatic TNBC, marked an important addition to the TNBC drug armamentarium. “Sacituzumab govitecan is one of the most exciting drugs available for the treatment of metastatic disease,” Dr. Nanda said.

Sacituzumab govitecan, approved as third-line therapy for metastatic TNBC, works by targeting the cell surface protein TROP2, expressed in about 88% of TNBC tumors but rarely in healthy cells.

In the phase 1/2 ASCENT trial, the median progression-free survival was 5.5 months and overall survival was 13.0 months in 108 patients with metastatic TNBC who had received at least two therapies prior to sacituzumab govitecan.

A subsequent phase 3 trial showed progression-free survival of 5.6 months with sacituzumab govitecan and 1.7 months with physician’s choice of chemotherapy. The median overall survival was 12.1 months and 6.7 months, respectively.

But, according to the analysis, TROP2 expression did not necessarily predict who would benefit from sacituzumab govitecan. A biomarker study revealed that although patients with moderate to high TROP2 expression exhibited the strongest treatment response, those with low TROP2 expression also survived longer when given sacituzumab govitecan, compared with chemotherapy alone.

In other words, “patients did better on sacituzumab govitecan regardless of TROP2 expression, which suggests we do not have a good biomarker for identifying who will benefit,” Dr. Nanda said.

Two other investigational antibody-drug conjugates, trastuzumab deruxtecan and ladiratuzumab vedotin, show promise in the metastatic space as well. For instance, the recent phase 2 trial evaluating trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer reported treatment response in 44% of patients with HER2-low tumors.

Given that about 36.6% of TNBC tumors exhibit low levels of HER2 expression, “trastuzumab deruxtecan represents potential in treating HER2-low TNBC,” said Yuan Yuan, MD, PhD, medical oncologist at City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer center in Los Angeles County.

Early results from a phase 1b study showed that trastuzumab deruxtecan produced a response rate of 37% in patients with HER2-low breast cancer.

Investigators are now recruiting for an open-label phase 3 trial to determine whether trastuzumab deruxtecan extends survival in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancers.

Immunotherapy advances

Immune checkpoint inhibitors represent another promising treatment avenue for metastatic TNBC. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, recently approved by the FDA, show moderate progression-free and overall survival benefits in patients with metastatic TNBC expressing PD-L1. Estimates of PD-L1 immune cells present in TNBC tumors vary widely, from about 20% to 65%.

Yet, data on which patients will benefit are not so clear-cut. “These drugs give us more choices and represent the fast-evolving therapeutic landscape in TNBC, but they also leave a lot of unanswered questions about PD-L1 as a biomarker,” Dr. Yuan said.

Take two recent phase 3 trials evaluating atezolizumab: IMpassion130 and IMpassion131. In IMpassion130, patients with PDL1–positive tumors exhibited significantly longer median overall survival on atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel (25.0 months) compared with nab-paclitaxel alone (15.5 months). As with the trend observed in the TROP2 data for sacituzumab govitecan, all patients survived longer on atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel regardless of PD-L1 status: 21.3 months vs. 17.6 months with nab-paclitaxel alone.