User login

The ‘Three Rs’ of email effectiveness

Resist, Reorganize, and Respond

PING – you look down at your phone and the words “URGENT – Meeting Today” stare back at you. The elevator door opens, and you step inside – 1 minute, the seemingly perfect amount of time for a quick inbox check.

As a hospitalist, chances are you have experienced this scenario, likely more than once. Email has become a double-edged sword, both a valuable communication tool and a source of stress and frustration.1 A 2012 McKinsey analysis found that the average professional spends 28% of the day reading and answering emails.2 Smartphone technology with email alerts and push notifications constantly diverts hospitalists’ attention away from important and nonurgent responsibilities such as manuscript writing, family time, and personal well-being.3

How can we break this cycle of compulsive connectivity? To keep email from controlling your life, we suggest the “Three Rs” (Resist, Reorganize, and Respond) of email effectiveness.

RESIST

The first key to take control of your inbox is to resist the urge to impulsively check and respond to emails. Consider these three solutions to bolster your ability to resist.

- Disable email push notifications. This will reduce the urge to continuously refresh your inbox on the wards.4 Excessively checking email can waste as much as 21 minutes per day.2

- Set an email budget.5 Schedule one to two appointments each day to handle email.6 Consider blocking 30 minutes after rounds and 30 minutes at the end of each day to address emails.

- Correspond at a computer. Limit email correspondence to your laptop or desktop. Access to a full keyboard and larger screen will maximize the efficiency of each email appointment.

REORGANIZE

After implementing these strategies to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox with the following two-pronged approach.

- Focus your inbox: There are many options for reducing the volume of emails that flood your inbox. Try collaborative tools like Google Docs, Dropbox, Doodle polls, and Slack to shift communication away from email onto platforms optimized to your project’s specific needs. Additionally, email management tools like SaneBox and OtherInbox triage less important messages directly to folders, leaving only must-read-now messages in your inbox.2 Lastly, activate spam filters and unsubscribe from mailing lists to eliminate email clutter.

- Commit to concise filing and finding: Archiving emails into a complex array of folders wastes as much as 14 minutes each day. Instead, limit your filing system to two folders: “Action” for email requiring further action and “Reading” for messages to reference at a later date.2 Activating “Communication View” on Microsoft Outlook allows rapid review of messages that share the same subject heading.

RESPOND

Finally, once your inbox is reorganized, use the Four Ds for Decision Making model to optimize the way you respond to email.6 When you sit down for an email appointment, use the Four Ds, detailed below to avoid reading the same message repeatedly without taking action.

- Delete: Quickly delete any emails that do not directly require your attention or follow-up. Many emails can be immediately deleted without further thought.

- Do: If a task or response to an email will take less than 2 minutes, do it immediately. It will take at least the same amount to retrieve and reread an email as it will to handle it in real time.7 Often, this can be accomplished with a quick phone call or email reply.

- Defer: If an email response will take more than 2 minutes, use a system to take action at a later time. Move actionable items from your inbox to a to-do list or calendar appointment and file appropriate emails into the Action or Reading folders, detailed above. This method allows completion of important tasks in a timely manner outside of your fixed email budget. Delaying an email reply can also be advantageous by letting a problem mature, given that some of these issues will resolve without your specific intervention.

- Delegate: This can be difficult for many hospitalists who are accustomed to finishing each task themselves. If someone else can do the task as good as or better than you can, it is wise to delegate whenever possible.

Over the next few weeks, challenge yourself to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox, and methodically respond to emails. This practice will help structure your day, maximize your efficiency, manage colleagues’ expectations, and create new time windows throughout your on-service weeks.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans. Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

References

1. MacKinnon R. How you manage your emails may be bad for your health. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/160104081249.htm. Published Jan 4, 2016.

2. Plummer M. How to spend way less time on email every day. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/how-to-spend-way-less-time-on-email-every-day. 2019 Jan 22.

3. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York: Free Press, 2004.

4. Ericson C. 5 Ways to Take Control of Your Email Inbox. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/learnvest/2014/03/17/5-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email-inbox/#3711f5946342. 2014 Mar 17.

5. Limit the time you spend on email. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/02/limit-the-time-you-spend-on-email. 2014 Feb 6.

6. McGhee S. Empty your inbox: 4 ways to take control of your email. Internet and Telephone Blog. https://www.itllc.net/it-support-ma/empty-your-inbox-4-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email/.

7. Allen D. Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. New York: Penguin Books, 2015.

Resist, Reorganize, and Respond

Resist, Reorganize, and Respond

PING – you look down at your phone and the words “URGENT – Meeting Today” stare back at you. The elevator door opens, and you step inside – 1 minute, the seemingly perfect amount of time for a quick inbox check.

As a hospitalist, chances are you have experienced this scenario, likely more than once. Email has become a double-edged sword, both a valuable communication tool and a source of stress and frustration.1 A 2012 McKinsey analysis found that the average professional spends 28% of the day reading and answering emails.2 Smartphone technology with email alerts and push notifications constantly diverts hospitalists’ attention away from important and nonurgent responsibilities such as manuscript writing, family time, and personal well-being.3

How can we break this cycle of compulsive connectivity? To keep email from controlling your life, we suggest the “Three Rs” (Resist, Reorganize, and Respond) of email effectiveness.

RESIST

The first key to take control of your inbox is to resist the urge to impulsively check and respond to emails. Consider these three solutions to bolster your ability to resist.

- Disable email push notifications. This will reduce the urge to continuously refresh your inbox on the wards.4 Excessively checking email can waste as much as 21 minutes per day.2

- Set an email budget.5 Schedule one to two appointments each day to handle email.6 Consider blocking 30 minutes after rounds and 30 minutes at the end of each day to address emails.

- Correspond at a computer. Limit email correspondence to your laptop or desktop. Access to a full keyboard and larger screen will maximize the efficiency of each email appointment.

REORGANIZE

After implementing these strategies to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox with the following two-pronged approach.

- Focus your inbox: There are many options for reducing the volume of emails that flood your inbox. Try collaborative tools like Google Docs, Dropbox, Doodle polls, and Slack to shift communication away from email onto platforms optimized to your project’s specific needs. Additionally, email management tools like SaneBox and OtherInbox triage less important messages directly to folders, leaving only must-read-now messages in your inbox.2 Lastly, activate spam filters and unsubscribe from mailing lists to eliminate email clutter.

- Commit to concise filing and finding: Archiving emails into a complex array of folders wastes as much as 14 minutes each day. Instead, limit your filing system to two folders: “Action” for email requiring further action and “Reading” for messages to reference at a later date.2 Activating “Communication View” on Microsoft Outlook allows rapid review of messages that share the same subject heading.

RESPOND

Finally, once your inbox is reorganized, use the Four Ds for Decision Making model to optimize the way you respond to email.6 When you sit down for an email appointment, use the Four Ds, detailed below to avoid reading the same message repeatedly without taking action.

- Delete: Quickly delete any emails that do not directly require your attention or follow-up. Many emails can be immediately deleted without further thought.

- Do: If a task or response to an email will take less than 2 minutes, do it immediately. It will take at least the same amount to retrieve and reread an email as it will to handle it in real time.7 Often, this can be accomplished with a quick phone call or email reply.

- Defer: If an email response will take more than 2 minutes, use a system to take action at a later time. Move actionable items from your inbox to a to-do list or calendar appointment and file appropriate emails into the Action or Reading folders, detailed above. This method allows completion of important tasks in a timely manner outside of your fixed email budget. Delaying an email reply can also be advantageous by letting a problem mature, given that some of these issues will resolve without your specific intervention.

- Delegate: This can be difficult for many hospitalists who are accustomed to finishing each task themselves. If someone else can do the task as good as or better than you can, it is wise to delegate whenever possible.

Over the next few weeks, challenge yourself to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox, and methodically respond to emails. This practice will help structure your day, maximize your efficiency, manage colleagues’ expectations, and create new time windows throughout your on-service weeks.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans. Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

References

1. MacKinnon R. How you manage your emails may be bad for your health. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/160104081249.htm. Published Jan 4, 2016.

2. Plummer M. How to spend way less time on email every day. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/how-to-spend-way-less-time-on-email-every-day. 2019 Jan 22.

3. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York: Free Press, 2004.

4. Ericson C. 5 Ways to Take Control of Your Email Inbox. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/learnvest/2014/03/17/5-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email-inbox/#3711f5946342. 2014 Mar 17.

5. Limit the time you spend on email. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/02/limit-the-time-you-spend-on-email. 2014 Feb 6.

6. McGhee S. Empty your inbox: 4 ways to take control of your email. Internet and Telephone Blog. https://www.itllc.net/it-support-ma/empty-your-inbox-4-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email/.

7. Allen D. Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. New York: Penguin Books, 2015.

PING – you look down at your phone and the words “URGENT – Meeting Today” stare back at you. The elevator door opens, and you step inside – 1 minute, the seemingly perfect amount of time for a quick inbox check.

As a hospitalist, chances are you have experienced this scenario, likely more than once. Email has become a double-edged sword, both a valuable communication tool and a source of stress and frustration.1 A 2012 McKinsey analysis found that the average professional spends 28% of the day reading and answering emails.2 Smartphone technology with email alerts and push notifications constantly diverts hospitalists’ attention away from important and nonurgent responsibilities such as manuscript writing, family time, and personal well-being.3

How can we break this cycle of compulsive connectivity? To keep email from controlling your life, we suggest the “Three Rs” (Resist, Reorganize, and Respond) of email effectiveness.

RESIST

The first key to take control of your inbox is to resist the urge to impulsively check and respond to emails. Consider these three solutions to bolster your ability to resist.

- Disable email push notifications. This will reduce the urge to continuously refresh your inbox on the wards.4 Excessively checking email can waste as much as 21 minutes per day.2

- Set an email budget.5 Schedule one to two appointments each day to handle email.6 Consider blocking 30 minutes after rounds and 30 minutes at the end of each day to address emails.

- Correspond at a computer. Limit email correspondence to your laptop or desktop. Access to a full keyboard and larger screen will maximize the efficiency of each email appointment.

REORGANIZE

After implementing these strategies to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox with the following two-pronged approach.

- Focus your inbox: There are many options for reducing the volume of emails that flood your inbox. Try collaborative tools like Google Docs, Dropbox, Doodle polls, and Slack to shift communication away from email onto platforms optimized to your project’s specific needs. Additionally, email management tools like SaneBox and OtherInbox triage less important messages directly to folders, leaving only must-read-now messages in your inbox.2 Lastly, activate spam filters and unsubscribe from mailing lists to eliminate email clutter.

- Commit to concise filing and finding: Archiving emails into a complex array of folders wastes as much as 14 minutes each day. Instead, limit your filing system to two folders: “Action” for email requiring further action and “Reading” for messages to reference at a later date.2 Activating “Communication View” on Microsoft Outlook allows rapid review of messages that share the same subject heading.

RESPOND

Finally, once your inbox is reorganized, use the Four Ds for Decision Making model to optimize the way you respond to email.6 When you sit down for an email appointment, use the Four Ds, detailed below to avoid reading the same message repeatedly without taking action.

- Delete: Quickly delete any emails that do not directly require your attention or follow-up. Many emails can be immediately deleted without further thought.

- Do: If a task or response to an email will take less than 2 minutes, do it immediately. It will take at least the same amount to retrieve and reread an email as it will to handle it in real time.7 Often, this can be accomplished with a quick phone call or email reply.

- Defer: If an email response will take more than 2 minutes, use a system to take action at a later time. Move actionable items from your inbox to a to-do list or calendar appointment and file appropriate emails into the Action or Reading folders, detailed above. This method allows completion of important tasks in a timely manner outside of your fixed email budget. Delaying an email reply can also be advantageous by letting a problem mature, given that some of these issues will resolve without your specific intervention.

- Delegate: This can be difficult for many hospitalists who are accustomed to finishing each task themselves. If someone else can do the task as good as or better than you can, it is wise to delegate whenever possible.

Over the next few weeks, challenge yourself to resist email temptations, reorganize your inbox, and methodically respond to emails. This practice will help structure your day, maximize your efficiency, manage colleagues’ expectations, and create new time windows throughout your on-service weeks.

Dr. Nelson is a hospitalist at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans. Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

References

1. MacKinnon R. How you manage your emails may be bad for your health. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/160104081249.htm. Published Jan 4, 2016.

2. Plummer M. How to spend way less time on email every day. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/01/how-to-spend-way-less-time-on-email-every-day. 2019 Jan 22.

3. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York: Free Press, 2004.

4. Ericson C. 5 Ways to Take Control of Your Email Inbox. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/learnvest/2014/03/17/5-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email-inbox/#3711f5946342. 2014 Mar 17.

5. Limit the time you spend on email. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/02/limit-the-time-you-spend-on-email. 2014 Feb 6.

6. McGhee S. Empty your inbox: 4 ways to take control of your email. Internet and Telephone Blog. https://www.itllc.net/it-support-ma/empty-your-inbox-4-ways-to-take-control-of-your-email/.

7. Allen D. Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. New York: Penguin Books, 2015.

The branching tree of hospital medicine

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

Diversity of training backgrounds

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

In Reference to “Improving the Safety of Opioid Use for Acute Noncancer Pain in Hospitalized Adults: A Consensus Statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine”

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

We read with great interest the consensus statement on improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain by Herzig et al.1 We strongly support the recommendations outlined in the document.

However, we would like to advocate for an additional recommendation that was considered but not included by the authors. Given the proven benefit—with minimal risk—in providing naloxone to patients and family members, we encourage naloxone prescriptions at discharge for all patients at risk for opioid overdose independent of therapy duration.2 Even opioid-naive patients who are prescribed opioids at hospital discharge have a significantly higher risk for chronic opioid use.3

We support extrapolating recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to prescribe naloxone to all patients at discharge who are at risk for an opioid overdose, including those with a history of overdose or substance use disorder as well as those receiving a prescription of ≥50 mg morphine equivalents per day or who use opioids and benzodiazepines.4,5

Given the current barriers to healthcare access, prescribing naloxone at discharge may be a rare opportunity to provide a potential life-saving intervention to prevent a fatal opioid overdose.

Disclosures

We have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a third party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. We have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4);263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction 2016;111(7):1177-1187. doi: 10.1111/add.13326. PubMed

3. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4. PubMed

4. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. PubMed

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63, Full Document. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18- 5063FULLDOC. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA18-5063FULLDOC/SMA18-5063FULLDOC.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2018.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Things We Do For No Reason: The Default Use of Hypotonic Maintenance Intravenous Fluids in Pediatrics

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 12-month-old female is admitted for acute bronchiolitis with increased work of breathing and decreased oral intake. She is mildly dehydrated upon exam with a sodium level of 139 mEq/L and is given a 20 mL/kg bolus of 0.9% saline. Given the patient’s poor oral intake, the admitting intern orders maintenance intravenous (IV) fluids and asks her senior resident which IV fluid should be used. The medical student on the team wonders if a different IV fluid would be selected for a 2-week-old with a similar presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance IV fluids are continuously infused to preserve extracellular volume and electrolyte balance when fluids cannot be taken orally. In contrast, resuscitation IV fluids are given as a bolus to patients in states of hypoperfusion to restore extracellular volume. The given IV fluid concentration can be categorized as approximately equal to (isotonic) or less than (hypotonic) the plasma sodium concentration. Refer to Table 1 for the electrolyte composition of commonly used IV fluids. Dextrose is rapidly metabolized upon infusion and does not affect tonicity.

Why You Might Think Hypotonic Maintenance IV Fluids Are The Right Choice

A 1957 publication by Holliday and Segar laid the foundation for maintenance IV fluid and electrolyte requirements in children and was the initial catalyst for the use of hypotonic maintenance IV fluids.1 This manuscript contended that hypotonic IV fluids could supply the water and sodium needed to meet maintenance dietary requirements. This claim led to the predominant use of hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in children. By contrast, isotonic IV fluids have been avoided given the apprehension over electrolytes exceeding maintenance needs.

Concerns about the unintended consequences of fluid overload – edema, hypernatremia, and hypertension secondary to increased sodium load – have led some to avoid isotonic IV fluids.2 When presented with common clinical scenarios of patients at risk for excess antidiuretic hormone (ADH; also known as arginine vasopressin), pediatric residents chose hypotonic (instead of isotonic) IV fluids 78% of the time.3

Why Isotonic Maintenance IV Fluids Are Usually The Right Choice For Children

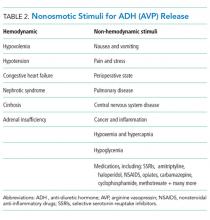

General recommendations for hypotonic IV fluids are primarily based on theoretical calculations from the fluid and electrolyte requirements of healthy individuals, and studies have not validated the use of hypotonic IV fluids in clinical practice.1 Acutely ill patients are at risk for excessive levels of ADH from numerous causes (see Table 2).2 As a result, nearly every hospitalized patient is at risk for excess ADH release, thus making them vulnerable to the development of hyponatremia. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH (SIADH) occurs when nonosmotic/nonhemodynamic stimuli trigger ADH release, which leads to excessive free-water retention and resultant hyponatremia. Schwartz and Bartter reported the first two cases of SIADH in 1957 when hyponatremia developed in the setting of bronchogenic carcinoma.4 Although the publication by Holliday and Seger did acknowledge the potential for water intoxication, it was written before this report and before the effects of ADH on the sodium levels of hospitalized patients were clearly understood.2 SIADH is now recognized as one of the most common causes of hyponatremia in hospitalized patients.5, 6

Numerous studies have demonstrated that patients who receive hypotonic IV fluids have a significantly higher risk of developing hyponatremia than patients who receive isotonic IV fluids.7,8 An infrequent, yet serious, complication of iatrogenic hyponatremia is hyponatremic encephalopathy, which carries a high rate of morbidity or mortality.9 The prevention of hyponatremia is essential as the early symptoms of hyponatremic encephalopathy are nonspecific and can be easily missed.2

More than 15 prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 2,000 children have demonstrated that isotonic IV fluids are more effective in preventing hospital-acquired hyponatremia than hypotonic IV fluids and are not associated with the development of fluid overload or hypernatremia. A 2014 metaanalysis comprising 10 RCTs and involving over 800 children found that when compared with isotonic IV fluids, hypotonic IV fluids present a relative risk of 2.37 for sodium levels to drop below 135 mEq/L and a relative risk of 6.1 for levels to drop below 130 mEq/L. The numbers needed to treat (NNT) with isotonic IV fluids to prevent hyponatremia in each group were 6 and 17, respectively.7 A Cochrane review published in 2014 presented comparable findings, demonstrating that hypotonic IV fluids had a 34% risk of causing hyponatremia; by comparison, isotonic IV fluids had a 17% risk of causing hyponatremia and a NNT of six to prevent hyponatremia.8 In a large RCT conducted in 2015 with 676 pediatric patients, McNabb et al. found that when compared with patients receiving isotonic IV fluids, those receiving hypotonic IV fluids had a higher incidence of developing hyponatremia (10.9% versus 3.8%) with a NNT of 15 to prevent hyponatremia with the use of isotonic fluids.10 Published trials have likely been underpowered to detect a difference in the infrequent adverse hyponatremia outcomes of seizures and mortality.

On the basis of these data, patient safety alerts have recommended the avoidance of hypotonic IV fluids in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, and the 2015 UK guidelines for children now recommend isotonic IV fluids for maintenance needs.11 Although many of the aforementioned studies included predominantly critically ill or surgical pediatric patients, the risk of hyponatremia with hypotonic IV fluids seems similarly increased in nonsurgical and noncritically ill pediatric patients.10

For patients at risk for excess ADH release, some have supported the use of hypotonic IV fluids at a lower than maintenance rate to theoretically decrease the risk of hyponatremia, but this practice has not been effective in preventing hyponatremia.2,12 Unless a patient is in a fluid overload state, such as in congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, or renal failure; isotonic maintenance IV fluids should not result in fluid overload.3 Available evidence for guiding maintenance IV fluid choice in neonates or young infants is limited. Nevertheless, given the aforementioned reasons, we generally recommend the prescription of isotonic IV fluids for most in this population.

Which Isotonic IV Fluid Should Be Used?

The sodium concentration (154 mmol/L) of 0.9% saline, an isotonic IV fluid, is approximately equal to the tonicity of the aqueous phase of plasma. The majority of studies evaluating the risk of hyponatremia with maintenance IV fluids have used 0.9% saline as the studied isotonic IV fluid. Plasma-Lyte and Ringer’s lactate are low-chloride, buffered/balanced solutions. Plasma-Lyte ([Na] = 140 mmol/L) has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing hyponatremia. Ringers’ lactate is slightly hypotonic ([Na] = 130 mmol/L), and its administration is associated with a decrease in serum sodium.13 A resultant dilutional and hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is more likely to develop with the use of large volumes of 0.9% saline in resuscitation than with the use of balanced solutions.2 Whether the prolonged use of 0.9% saline maintenance IV fluids can lead to this same side effect remains unknown given insufficient evidence.2 Retrospective studies using balanced solutions have shown an association with decreased rates of acute kidney injury (AKI) and mortality when compared with 0.9% saline. However, a RCT with over 2,000 adult ICU patients showed no change in rates of AKI in those that received Plasma-Lyte compared with those who received 0.9% saline.14

Two recent, single-center, prospective studies compared the use of Ringer’s lactate or Plasma-Lyte for resuscitation with that of 0.9% saline. One study was comprised of 15,802 critically ill adults, and the other was comprised of 13,347 noncritically adults. Both studies showed that balanced solutions decreased the rate of major adverse kidney events (defined as a composite of death from any cause, new renal-replacement therapy, or persistent renal injury) within 30 days.15,16 Available published pediatric studies indicate that 0.9% saline is an effective maintenance IV fluid for the prevention of hyponatremia that is not associated with hypernatremia or fluid overload. Further pediatric studies comparing 0.9% saline with balanced solutions are needed.

When Should We Use Hypotonic IV Fluids?

Hypotonic IV fluids may be needed for patients with hypernatremia and a free-water deficit or a renal-concentrating defect with ongoing urinary free-water losses.2 Special care should be taken when choosing maintenance IV fluids for patients with renal disease, liver disease, or heart failure given that these groups have been excluded from some studies.12 These patients may be at risk for increased salt and fluid retention with any IV fluid, and fluid rates need to be restricted. The fluid intake of patients with hyponatremia secondary to SIADH needs close management; these patients benefit from total fluid restriction instead of standard maintenance IV fluid rates.2

What We Should Do Instead?

Maintenance IV fluids should only be used when necessary and should be stopped as soon as they are no longer required, especially in light of the recent shortages in 0.9% saline.17 Similar to all medications, maintenance IV fluids should be individualized to the patient’s needs on the basis of the indication for IV fluids and the patient’s comorbidities.2 Consideration should be given to checking the patient’s electrolyte levels to monitor response to IV fluids, especially during the first 24 hours of admission when risk of hyponatremia is highest. Isotonic IV fluids with 5% dextrose should be used as the maintenance IV fluid in the majority of hospitalized children given its proven benefit in decreasing the rate of hospital-acquired hyponatremia.7,8 Hypotonic IV fluids should be avoided as the default maintenance IV fluid and should only be utilized under specific circumstances.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- When needed, maintenance IV fluids should always be tailored to each individual patient.

- For most acutely ill hospitalized children, isotonic IV fluids should be the maintenance IV fluid of choice.

- Consider monitoring electrolytes to determine the effects of maintenance IV fluids.

CONCLUSION

Enteral maintenance fluids should be used first-line if possible. Although hypotonic IV fluids have historically been the maintenance IV fluid of choice, this class of IV fluids should be avoided for most hospitalized children to decrease the significant risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia, which can be severe and have catastrophic complications. When necessary, isotonic IV fluids should be used for the majority of hospitalized children given that these fluids present a significantly decreased risk for causing hyponatremia. Returning to our case presentation, to decrease the risk of hyponatremia, the senior resident should recommend starting isotonic IV fluids in the 12-month-old and theoretical 2-week-old until oral intake can be maintained.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

Disclosure

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report. No payment or services from a 3rd party were received for any aspect of this submitted work. The authors have no financial relationships with entities in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, what was written in this submitted work.

1. Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics. 1957;19(5):823-832. PubMed

2. Moritz ML, Ayus JC. Maintenance intravenous fluids in acutely Ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1350-1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1412877. PubMed

3. Freeman MA, Ayus JC, Moritz ML. Maintenance intravenous fluid prescribing practices among paediatric residents. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(10):e465-e468. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02780.x. PubMed

4. Schwartz WB BW, Curelop S, Bartter FC. A syndrome of renal sodium loss and hyponatremia probably resulting from inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1957;23(4):529-542. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(57)90224-3. PubMed

5. Wattad A, Chiang ML, Hill LL. Hyponatremia in hospitalized children. Clin Pediatr. 1992;31(3):153-157. doi: 10.1177/000992289203100305. PubMed

6. Greenberg A, Verbalis JG, Amin AN, et al. Current treatment practice and outcomes. Report of the hyponatremia registry. Kidney Int. 2015;88(1):167-177. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.4. PubMed

7. Foster BA, Tom D, Hill V. Hypotonic versus isotonic fluids in hospitalized children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2014;165(1):163-169.e162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.040. PubMed

8. McNab S, Ware RS, Neville KA, et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD009457. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009457.pub2. PubMed

9. Arieff AI, Ayus JC, Fraser CL. Hyponatraemia and death or permanent brain damage in healthy children. BMJ. 1992;304(6836):1218-1222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6836.1218. PubMed

10. McNab S, Duke T, South M, et al. 140 mmol/L of sodium versus 77 mmol/L of sodium in maintenance intravenous fluid therapy for children in hospital (PIMS): A randomised controlled double-blind trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1190-1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61459-8. PubMed

11. Neilson J, O’Neill F, Dawoud D, Crean P, Guideline Development G. Intravenous fluids in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h6388. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6388. PubMed

12. Neville KA, Sandeman DJ, Rubinstein A, Henry GM, McGlynn M, Walker JL. Prevention of hyponatremia during maintenance intravenous fluid administration: a prospective randomized study of fluid type versus fluid rate. J Pediatr. 2010;156(2):313-319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.059. PubMed

13. Moritz ML, Ayus JC. Preventing neurological complications from dysnatremias in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(12):1687-1700. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1933-6. PubMed

14. Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R, et al. Effect of a buffered crystalloid solution vs saline on acute kidney injury among patients in the intensive care unit: The SPLIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1701-1710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12334. PubMed

15. Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced crystalloids versus salinein critically Ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):829-839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584. PubMed

16. Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in noncritically Ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):819-828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711586. PubMed

17. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER. Saline shortages - Many causes, no simple solution. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1472-1474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1800347. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 12-month-old female is admitted for acute bronchiolitis with increased work of breathing and decreased oral intake. She is mildly dehydrated upon exam with a sodium level of 139 mEq/L and is given a 20 mL/kg bolus of 0.9% saline. Given the patient’s poor oral intake, the admitting intern orders maintenance intravenous (IV) fluids and asks her senior resident which IV fluid should be used. The medical student on the team wonders if a different IV fluid would be selected for a 2-week-old with a similar presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance IV fluids are continuously infused to preserve extracellular volume and electrolyte balance when fluids cannot be taken orally. In contrast, resuscitation IV fluids are given as a bolus to patients in states of hypoperfusion to restore extracellular volume. The given IV fluid concentration can be categorized as approximately equal to (isotonic) or less than (hypotonic) the plasma sodium concentration. Refer to Table 1 for the electrolyte composition of commonly used IV fluids. Dextrose is rapidly metabolized upon infusion and does not affect tonicity.

Why You Might Think Hypotonic Maintenance IV Fluids Are The Right Choice

A 1957 publication by Holliday and Segar laid the foundation for maintenance IV fluid and electrolyte requirements in children and was the initial catalyst for the use of hypotonic maintenance IV fluids.1 This manuscript contended that hypotonic IV fluids could supply the water and sodium needed to meet maintenance dietary requirements. This claim led to the predominant use of hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in children. By contrast, isotonic IV fluids have been avoided given the apprehension over electrolytes exceeding maintenance needs.

Concerns about the unintended consequences of fluid overload – edema, hypernatremia, and hypertension secondary to increased sodium load – have led some to avoid isotonic IV fluids.2 When presented with common clinical scenarios of patients at risk for excess antidiuretic hormone (ADH; also known as arginine vasopressin), pediatric residents chose hypotonic (instead of isotonic) IV fluids 78% of the time.3

Why Isotonic Maintenance IV Fluids Are Usually The Right Choice For Children

General recommendations for hypotonic IV fluids are primarily based on theoretical calculations from the fluid and electrolyte requirements of healthy individuals, and studies have not validated the use of hypotonic IV fluids in clinical practice.1 Acutely ill patients are at risk for excessive levels of ADH from numerous causes (see Table 2).2 As a result, nearly every hospitalized patient is at risk for excess ADH release, thus making them vulnerable to the development of hyponatremia. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH (SIADH) occurs when nonosmotic/nonhemodynamic stimuli trigger ADH release, which leads to excessive free-water retention and resultant hyponatremia. Schwartz and Bartter reported the first two cases of SIADH in 1957 when hyponatremia developed in the setting of bronchogenic carcinoma.4 Although the publication by Holliday and Seger did acknowledge the potential for water intoxication, it was written before this report and before the effects of ADH on the sodium levels of hospitalized patients were clearly understood.2 SIADH is now recognized as one of the most common causes of hyponatremia in hospitalized patients.5, 6

Numerous studies have demonstrated that patients who receive hypotonic IV fluids have a significantly higher risk of developing hyponatremia than patients who receive isotonic IV fluids.7,8 An infrequent, yet serious, complication of iatrogenic hyponatremia is hyponatremic encephalopathy, which carries a high rate of morbidity or mortality.9 The prevention of hyponatremia is essential as the early symptoms of hyponatremic encephalopathy are nonspecific and can be easily missed.2

More than 15 prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 2,000 children have demonstrated that isotonic IV fluids are more effective in preventing hospital-acquired hyponatremia than hypotonic IV fluids and are not associated with the development of fluid overload or hypernatremia. A 2014 metaanalysis comprising 10 RCTs and involving over 800 children found that when compared with isotonic IV fluids, hypotonic IV fluids present a relative risk of 2.37 for sodium levels to drop below 135 mEq/L and a relative risk of 6.1 for levels to drop below 130 mEq/L. The numbers needed to treat (NNT) with isotonic IV fluids to prevent hyponatremia in each group were 6 and 17, respectively.7 A Cochrane review published in 2014 presented comparable findings, demonstrating that hypotonic IV fluids had a 34% risk of causing hyponatremia; by comparison, isotonic IV fluids had a 17% risk of causing hyponatremia and a NNT of six to prevent hyponatremia.8 In a large RCT conducted in 2015 with 676 pediatric patients, McNabb et al. found that when compared with patients receiving isotonic IV fluids, those receiving hypotonic IV fluids had a higher incidence of developing hyponatremia (10.9% versus 3.8%) with a NNT of 15 to prevent hyponatremia with the use of isotonic fluids.10 Published trials have likely been underpowered to detect a difference in the infrequent adverse hyponatremia outcomes of seizures and mortality.

On the basis of these data, patient safety alerts have recommended the avoidance of hypotonic IV fluids in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, and the 2015 UK guidelines for children now recommend isotonic IV fluids for maintenance needs.11 Although many of the aforementioned studies included predominantly critically ill or surgical pediatric patients, the risk of hyponatremia with hypotonic IV fluids seems similarly increased in nonsurgical and noncritically ill pediatric patients.10

For patients at risk for excess ADH release, some have supported the use of hypotonic IV fluids at a lower than maintenance rate to theoretically decrease the risk of hyponatremia, but this practice has not been effective in preventing hyponatremia.2,12 Unless a patient is in a fluid overload state, such as in congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, or renal failure; isotonic maintenance IV fluids should not result in fluid overload.3 Available evidence for guiding maintenance IV fluid choice in neonates or young infants is limited. Nevertheless, given the aforementioned reasons, we generally recommend the prescription of isotonic IV fluids for most in this population.

Which Isotonic IV Fluid Should Be Used?