User login

Stigma is a family affair

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

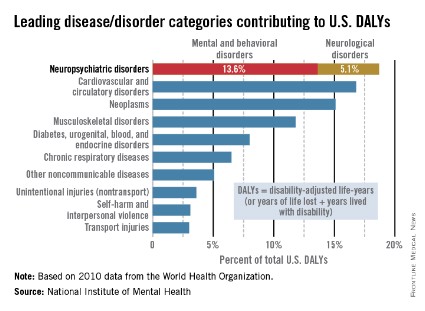

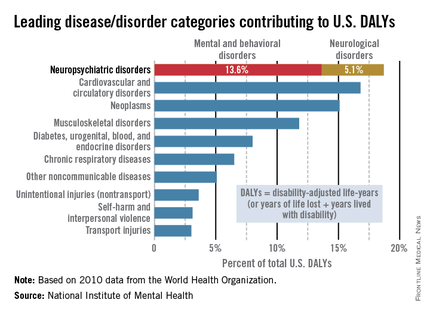

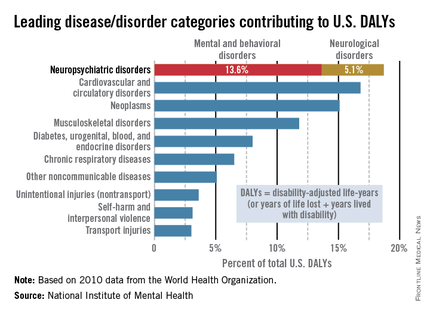

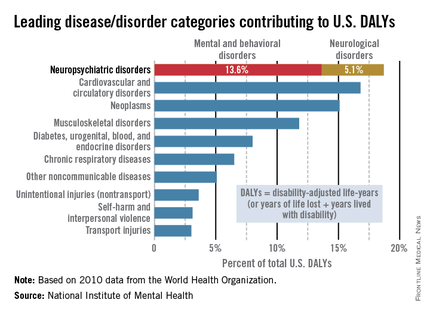

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Each year, 60 million Americans experience mental illness. Across the United States, each year, regardless of race, age, religion, or economic status, mental illness affects the lives of one in four adults and one in 10 children. This means that someone in every family has mental illness.

Most of our patients probably don’t tell anyone that they or one of their family members has mental illness They probably are doing what most of us do: Pretend it’s not there. Why? Because the stigma of mental illness is pervasive and destructive. What can we do to decrease the stigma?

The word stigma is derived from Greek and means "to mark the body." The bearer of the mark, or the stigma, is avoided and shunned. This practice has continued through the ages. In medieval times, if a person had a mental illness, he or she was thought to be possessed by demons and viewed as weak. Today, people with mental illness are viewed as menacing, deviant, unpredictable, incompetent, or even dangerous. It is entirely reasonable then, that we would want to avoid the stigma of mental illness. However, this prejudice against mental illness must be challenged.

Mental illness accounts for increased morbidity and mortality as well as lifetime disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States, followed by cardiovascular and circulatory diseases, and neoplasms. The neuropsychiatric disorders category, which includes mental and behavioral disorders, accounts for 13.6% of total U.S. disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Neurological disorders account for 5.1% of total U.S. DALYs.

Impact on the family

Not only does stigma affect individuals, it affects family members as well. Family members suffer from SBA, or stigma by association (Brit. J. Psych. 2002;181:494-8), also known as courtesy stigma (Social. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003;38:593-602). Families share stigma because families share a genetic heritage. Families share stigma by assuming responsibility for their family members’ behaviors. Families share stigma because they are seen as having common motivations (J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:224-41).

SBA causes psychological distress in family members (Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58:73-80; J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1987;175:4-11; Br. J. Psychiatry 2002;181:494-8; and Schizophr. Bull. 1998;24:115-126).

Psychological complaints, such as brooding, inner unrest, and irritability, and physical complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, and neck and shoulder pain, have been attributed to the psychological distress of SBA. Family members may avoid social interactions and conceal their relationship to the family member who is mentally ill (Acad. Psychiatry 2008;32:87-91). They might psychologically distance themselves from a relative with mental illness.

SBA varies by disease type, family role, and age. The greatest SBA is associated with drug dependence. These family members are blamed for the illness, held responsible for relapse, and viewed as incompetent. In the study of Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., (J. Fam. Psychol. 2006;20:239-46), family members report feelings of "contamination" and shame. Severe depression or panic and phobias engender less stigma. More educated people are less likely to report feelings of stigma.

According to Dr. Corrigan, SBA varies by family role: Parents are blamed for causing the child’s mental illness, siblings are blamed for not ensuring that relatives with mental illness adhere to treatment plans, and children are fearful of being "contaminated" with the mental illness of their parent. The closer the relationship, the less the stigma is perceived as defining the person. Family closeness can reduce stigma (The Gerontologist 2012;52:89-97). Regarding age, a British study showed that the highest stigma is reported in the 16- to 19-year-old age group (Br. J. Psychiatry 2000;177:4-7).

Psychiatry as a profession has not helped diminish stigma. It is not uncommon to hear psychiatrists assign blame to parents or spouses. Psychiatrists often believe that the family has a role in the patient’s illness. How many spouses have been told they are "codependent" with the implication that they have somehow "caused the illness"? What can we do diminish stigma?

Fighting stigma

Fighting stigma means confronting stigma (Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000;6:65-72). Most efforts worldwide have begun with the idea of educating people about mental illness. These efforts, focused on promoting mental illness as a biological illness, have had limited success and in some situations actually increased stigma (Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012; 125:440-52). The answer may lie in targeted education: specific facts for specific groups.

For example, young couples with children become less fearful after education targeted specifically for them (Br. J. Psychiatry 1996;168:191-8). Antistigma campaigns are common throughout the world. The websites of most professional psychiatric organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, provide information about antistigma campaigns. Organizations often partner with mental health charities. Antistigma efforts also focus on publishing articles about stigma as the Lancet did in a series a few years ago (1998;352:1048). It is unclear whether these efforts reduce stigma. Dr. Corrigan suggests that meeting people who have mental illness weakens the tendency to link mental illness and violence (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002;6: 312-34).

The current consensus is that antistigma campaigns should focus on the competence of people with mental illness. In this vein, the Scottish Mental Health Arts & Film Festival highlights the contributions that people with mental illness make to society. The festival, which began in 2007, also sponsors a contest for films that depict people with mental illness in realistic, holistic ways. In 2013, the festival drew 12,000 attendees and sparked 120 newspaper articles that emphasized the fact that people with mental illness are generally active, useful members of society.

Meanwhile, a Canadian antistigma campaign tells the stories of people with mental illness and provides evidence of the competence of these people. The APA’s public service video series, "A Healthy Minds Minute," features celebrities and prominent figures calling for equal access to quality care, and insurance coverage for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

What do we do to reduce stigma? Psychiatrists such as William Beardslee have written about their personal experience of a family member with mental illness. A member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists, Julie Totten, lost her brother to suicide and in response, she developed an organization called Families for Depression Awareness, which is devoted to reducing the stigma of mental illness. For me, it is my personal campaign to say: "One in four means that someone in everyone’s family has mental illness."

What more can we do?

• Speak up when you hear or see stigma.

• Stress the normalcy of people who have mental illness.

• Come out of the closet on behalf of yourself or a family member.

• Include people who acknowledge they suffer from mental illness in antistigma campaigns.

• Discuss the role of stigma with patients and their families. Ask "How has stigma affected you as a family? In what ways has your family helped reduce the stigma of your mental illness?"

• Encourage attendance at support groups, such as NAMI (the National Alliance on Mental Illness).

• Embrace your family member or yourself: Look for personal qualities that wipe out stigma.

• Don’t allow people to stigmatize patients: It might be your family member they are talking about.

• Talk positively about respecting our patients.

• Start a conversation to reduce stigma.

• Remember that fighting stigma means confronting stigma.

Dr. Heru is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She has been a member of the Association of Family Psychiatrists since 2002 and currently serves as the organization’s treasurer. She is the author of a new book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Thinking about the institution of marriage – Part II

An earlier column reviewed the institution of marriage up to the middle of the last century. Since the 1950s, postmodernism has been gathering momentum, beginning as a critique of art, architecture, philosophy, and how we think about society and culture. Views on many aspects of our lives, as we live it, began to change.

Postmodernism stands in contrast to the "modern’ " or scientific view that touts a singularity of truth and a singular view of the world. Social construction is a type of postmodern theory that states that truth, reality, and knowledge are based in the social context of that particular person. This aspect of postmodernism is most applicable to mental health professionals assessing and treating patients, and to families in specific social and cultural contexts.

A postmodern view of the family considers the traditional view of the family, the "nuclear family," as only one view. Other forms of family and other views of marriage that had been marginalized, considered deviant and nonconforming, are now brought forward and considered as viable alternatives. Postmodernism discards many assumptions that we have been taught. One assumption that is being reexamined, for example, is that sexual nonexclusivity or extra-relationship sex, or romantic involvements are symptoms of troubled relationships or forms of sexual acting out.

Another assumption that needs to be reexamined is the notion that family structures found in other cultures are "abnormal" or dysfunctional. These assumptions are not necessarily true or false but require assessment in context of the relationship at hand. Postmodernism challenges us to assess each family variation on its own merit.

Beginnings

In the 20th century, Monica McGoldrick, Ph.D., one of the strong voices in family therapy, advocated for increased sensitivity to cultural variation. Her book, "Ethnicity and Family Therapy" (New York: The Guilford Press, 2005), describes characteristics of common ethnicities in American society.

Family therapists have attempted to address "nontraditional" families with articles, for example, about raising a biracial child, what to do if your child identifies as gay, etc. Most older articles focused on helping families "cope" with the nontraditional. Family therapists are now more willing to acknowledge "difference" as a normal rather than a pathological variant, and to recognize strengths inherent in diversity.

Acknowledging diversity

Marlene F. Watson, Ph.D., brings a nuanced understanding of the African American family, detailing the effect of slavery on the individuals in the family, and how internalized racism can be recognized and managed in family therapy (e-book, "Facing the Black Shadow," 2013). This is an important book for therapists, especially those who come from traditional families, as it articulates the reality of African American lives in a way that therapists can apply to clinical practice.

Dr. Watson illustrates through case examples how internalized racism affects marriages, and offers effective ways to help couples negotiate and overcome the negative aspects of their heritage. A postmodern stance also will help the couple recognize the resilience and strengths that are inherent in overcoming adversity.

Linda M. Burton, Ph.D., and Cecily R. Hardaway, Ph.D., highlight the role of "othermothers" in raising children in low-income families, be they white, Latino, or African American. They define "othermothering" as a form of coparenting, distinct from stepparenting. Women othermother children who are their romantic partners’ children from previous and concurrent relationships. Compared to stepfamilies, these multiple partner fertility relationships are more prevalent among young couples with limited financial resources, contentious relationships, and serial childbearing through serial repartnering.

In general, low-income women and women of color take on this style of coparenting to help the biological parents of relatives and friends who have limited social and psychological capital to protect and raise "good children"(Fam. Process. 2012;51:343-59). Family therapists will become much more effective if they understand and recognize that the motivation behind this form of mothering fosters resilience in the mothers. The more we know and understand alternate family structures, the more we can work toward building and sustaining resilience.

Assimilation has for many decades been the main focus of political and therapeutic endeavors. In postmodern times, transnationalism described a new way of thinking about relationships that extend across national boundaries and cultures (Fam. Process. 2007;46:157-71).

Immigrants maintain connections with their countries of origin with children who are parented by grandparents, or other relatives, perhaps in several countries at the same time. Family members use Skype, often daily, to connect with the matriarch or patriarch "back home."

Postmodern theories of social justice and cultural diversity work well with immigrants, bringing multiple perspectives into the treatment room. Immigrants bring many complex and diverse values in relation to marriage, gender, parenting, and religious practices. A social justice approach focuses on the racism and discrimination that is common in the lives of immigrants. Marriage might take place across nations, be arranged, or might be mixed race or mixed nationalities. Therapy that acknowledges these complexities will be most helpful. We still need to think further about global family life, how relationships evolve over long distances, and how to develop systemic and transnational interventions for separations and reunifications.

Sex and marriage

Nelson Mandela’s father had four wives, and he reported in an interview that he considered all of them his mothers and gained support from them all.

Polygamy has flourished in Africa and Asia for centuries, and more than 40 countries recognize polygamous marriages. In the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan, rich Kazakhs used to buy second wives from parents, often in exchange for livestock. Since Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, polygamy, although illegal, has again become common practice and is a status symbol for rich Kazakhs. Polygamy reportedly also is a way out of poverty for young women who save money and support their relatives back home

In the United Kingdom, polygamy has become more common in Muslim communities. Successful British Muslim women, who have delayed marriage to build careers, may choose to become a co-wife. They choose to share a husband in a relationship that they see as sanctioned by Islam. These women retain an independent lifestyle. "I didn’t want a full-time husband," one Muslim woman noted in an interview.

In the United States, the practice of polygamy was officially ended in the Mormon church in 1890. Nevertheless, several small "fundamentalist" groups continue the practice. One family of 14 wives and 17 children, the Browns of Nevada, are stars of a reality show that they reportedly hope educates the public about the choice.

Polyandry, a woman with multiple husbands, is described in many cultures. This practice frequently involves the marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife, which allows family-owned land to remain undivided. In some cultures, such as the Inuit, a man might arrange a second husband (frequently his brother) for his wife because he knows that, when he is absent, the second husband will protect his wife. Should she become pregnant while he is gone, it would be by someone he had approved in advance.

Penn State’s Stephen Beckerman, Ph.D., and his colleagues, in their study of the Bari people of Venezuela, found that children understood to have two fathers are significantly more likely to survive to age 15 than are children with only one. This is called "informal polyandry," because while the two fathers might not be formally married to and living with the mother in all cases, the society around them officially recognizes both men as legitimate mates to the mother, and father to her child.

Polyamory, the practice of open, multiple-partner relationships, is a structure that is increasingly common in Western countries, according to sociologist Elisabeth Sheff, Ph.D. Dr. Sheff’s 15 years of research leads her to believe that polyamory is a "legitimate relationship style that can be tremendously rewarding for adults and provide excellent nurturing for children."

She said she has found that children aged 5-8 do not seem to care about how the adults relate to one another, as long as they are taken care of. Overall, such children seem to fare well as long as they live in stable, loving homes.

Making this practice work, she acknowledges, is "time consuming and potentially fraught with emotional booby traps." People in polyamorous relationships emphasize that their relationships are about emotional connections with others, as opposed to primarily physical relationships.

The term polyfidelity, a subset of polyamory, was coined in the 1970s by members of the Kerista commune, which started in New York City in 1956. Polyfidelity is a concept in which clusters of friends form nonmonogamous sexual relationships. Under this family structure, group members do not relate sexually to anyone outside of the family group.

Although mainstream Judaism does not accept polyamory, some people do consider themselves Jewish and polyamorous. Sharon Kleinbaum, the senior rabbi at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York, has said that polyamory is a choice that does not preclude a Jewishly observant, socially conscious life. Some polyamorous Jews also point to biblical patriarchs having multiple wives and concubines as evidence that polyamorous relationships can be sacred in Judaism.

Jim Fleckenstein, director of the Institute for 21st-Century Relationships, has said that the polyamory movement has been driven by science fiction and feminism. He states that disillusionment with monogamy occurs "because of widespread cheating and divorce."

One fact going for the polys (as they are often known), is the belief that polyamory is more honest and less hypocritical than monogamy with secret affairs. A manual, "What Psychology Professionals Should Know About Polyamory," for psychotherapists who deal with polyamorous clients, was published in September 2009 by the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom.

The late Michael Shernoff, who was an openly gay psychotherapist, wrote that nonmonogamy is "a well-accepted part of gay subculture," and that somewhere between 30% and 67% of men in male couples reported being in a sexually nonmonogamous relationship. A majority of male couples are not sexually exclusive, but describe themselves as emotionally monogamous.

Mr. Shernoff stated: One of the biggest differences between male couples and mixed-sex couples is that many, but by no means all, within the gay community have an easier acceptance of sexual nonexclusivity than does heterosexual society in general. Research confirms that nonmonogamy in and of itself does not create a problem for male couples when it has been openly negotiated (Fam. Process. 2006;45:407-18).

The role of affairs in marriage can now be subjected to a more nuanced discussion, after digesting the above views and practice of marriage. What is the meaning of an affair? What is an open relationship? What are the models of intimacy? Is an affair a breach in the couple’s definition of intimacy? What are the rules? How does a couple define an affair within the context of their own relationship?

Conclusion

Postmodernism provides family therapists a new set of theories and a new language for describing the variety of families. As Jacqueline Hudak, Ph.D., and Shawn V. Giammattei, Ph.D., have written: "As family therapists, we are uniquely poised to transform the meanings attached to ‘marriage’ and ‘family,’ to focus on the quality of relationships rather than on the gender of a partner or the assumption of particular roles" ("Expanding Our Social Justice Practices: Advances in Theory and Practice," Washington: American Family Therapy Academy, Winter 2010).

The traditional view of marriage is referred to as "heteronormativity" and is defined by the belief that a viable family consists of "a heterosexual mother and a father raising heterosexual children together" ("Handbook of Qualitative Research," Thousand Oaks, Calif.:Sage, 2000). Despite the above expansion of views on marriage and families, heteronormativity remains the current organizing principle of family theory, practice, research, and training. It will take many decades to shift the dominant paradigm. Developing awareness, and listening to families and couples is the first step.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

An earlier column reviewed the institution of marriage up to the middle of the last century. Since the 1950s, postmodernism has been gathering momentum, beginning as a critique of art, architecture, philosophy, and how we think about society and culture. Views on many aspects of our lives, as we live it, began to change.

Postmodernism stands in contrast to the "modern’ " or scientific view that touts a singularity of truth and a singular view of the world. Social construction is a type of postmodern theory that states that truth, reality, and knowledge are based in the social context of that particular person. This aspect of postmodernism is most applicable to mental health professionals assessing and treating patients, and to families in specific social and cultural contexts.

A postmodern view of the family considers the traditional view of the family, the "nuclear family," as only one view. Other forms of family and other views of marriage that had been marginalized, considered deviant and nonconforming, are now brought forward and considered as viable alternatives. Postmodernism discards many assumptions that we have been taught. One assumption that is being reexamined, for example, is that sexual nonexclusivity or extra-relationship sex, or romantic involvements are symptoms of troubled relationships or forms of sexual acting out.

Another assumption that needs to be reexamined is the notion that family structures found in other cultures are "abnormal" or dysfunctional. These assumptions are not necessarily true or false but require assessment in context of the relationship at hand. Postmodernism challenges us to assess each family variation on its own merit.

Beginnings

In the 20th century, Monica McGoldrick, Ph.D., one of the strong voices in family therapy, advocated for increased sensitivity to cultural variation. Her book, "Ethnicity and Family Therapy" (New York: The Guilford Press, 2005), describes characteristics of common ethnicities in American society.

Family therapists have attempted to address "nontraditional" families with articles, for example, about raising a biracial child, what to do if your child identifies as gay, etc. Most older articles focused on helping families "cope" with the nontraditional. Family therapists are now more willing to acknowledge "difference" as a normal rather than a pathological variant, and to recognize strengths inherent in diversity.

Acknowledging diversity

Marlene F. Watson, Ph.D., brings a nuanced understanding of the African American family, detailing the effect of slavery on the individuals in the family, and how internalized racism can be recognized and managed in family therapy (e-book, "Facing the Black Shadow," 2013). This is an important book for therapists, especially those who come from traditional families, as it articulates the reality of African American lives in a way that therapists can apply to clinical practice.

Dr. Watson illustrates through case examples how internalized racism affects marriages, and offers effective ways to help couples negotiate and overcome the negative aspects of their heritage. A postmodern stance also will help the couple recognize the resilience and strengths that are inherent in overcoming adversity.

Linda M. Burton, Ph.D., and Cecily R. Hardaway, Ph.D., highlight the role of "othermothers" in raising children in low-income families, be they white, Latino, or African American. They define "othermothering" as a form of coparenting, distinct from stepparenting. Women othermother children who are their romantic partners’ children from previous and concurrent relationships. Compared to stepfamilies, these multiple partner fertility relationships are more prevalent among young couples with limited financial resources, contentious relationships, and serial childbearing through serial repartnering.

In general, low-income women and women of color take on this style of coparenting to help the biological parents of relatives and friends who have limited social and psychological capital to protect and raise "good children"(Fam. Process. 2012;51:343-59). Family therapists will become much more effective if they understand and recognize that the motivation behind this form of mothering fosters resilience in the mothers. The more we know and understand alternate family structures, the more we can work toward building and sustaining resilience.

Assimilation has for many decades been the main focus of political and therapeutic endeavors. In postmodern times, transnationalism described a new way of thinking about relationships that extend across national boundaries and cultures (Fam. Process. 2007;46:157-71).

Immigrants maintain connections with their countries of origin with children who are parented by grandparents, or other relatives, perhaps in several countries at the same time. Family members use Skype, often daily, to connect with the matriarch or patriarch "back home."

Postmodern theories of social justice and cultural diversity work well with immigrants, bringing multiple perspectives into the treatment room. Immigrants bring many complex and diverse values in relation to marriage, gender, parenting, and religious practices. A social justice approach focuses on the racism and discrimination that is common in the lives of immigrants. Marriage might take place across nations, be arranged, or might be mixed race or mixed nationalities. Therapy that acknowledges these complexities will be most helpful. We still need to think further about global family life, how relationships evolve over long distances, and how to develop systemic and transnational interventions for separations and reunifications.

Sex and marriage

Nelson Mandela’s father had four wives, and he reported in an interview that he considered all of them his mothers and gained support from them all.

Polygamy has flourished in Africa and Asia for centuries, and more than 40 countries recognize polygamous marriages. In the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan, rich Kazakhs used to buy second wives from parents, often in exchange for livestock. Since Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, polygamy, although illegal, has again become common practice and is a status symbol for rich Kazakhs. Polygamy reportedly also is a way out of poverty for young women who save money and support their relatives back home

In the United Kingdom, polygamy has become more common in Muslim communities. Successful British Muslim women, who have delayed marriage to build careers, may choose to become a co-wife. They choose to share a husband in a relationship that they see as sanctioned by Islam. These women retain an independent lifestyle. "I didn’t want a full-time husband," one Muslim woman noted in an interview.

In the United States, the practice of polygamy was officially ended in the Mormon church in 1890. Nevertheless, several small "fundamentalist" groups continue the practice. One family of 14 wives and 17 children, the Browns of Nevada, are stars of a reality show that they reportedly hope educates the public about the choice.

Polyandry, a woman with multiple husbands, is described in many cultures. This practice frequently involves the marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife, which allows family-owned land to remain undivided. In some cultures, such as the Inuit, a man might arrange a second husband (frequently his brother) for his wife because he knows that, when he is absent, the second husband will protect his wife. Should she become pregnant while he is gone, it would be by someone he had approved in advance.

Penn State’s Stephen Beckerman, Ph.D., and his colleagues, in their study of the Bari people of Venezuela, found that children understood to have two fathers are significantly more likely to survive to age 15 than are children with only one. This is called "informal polyandry," because while the two fathers might not be formally married to and living with the mother in all cases, the society around them officially recognizes both men as legitimate mates to the mother, and father to her child.

Polyamory, the practice of open, multiple-partner relationships, is a structure that is increasingly common in Western countries, according to sociologist Elisabeth Sheff, Ph.D. Dr. Sheff’s 15 years of research leads her to believe that polyamory is a "legitimate relationship style that can be tremendously rewarding for adults and provide excellent nurturing for children."

She said she has found that children aged 5-8 do not seem to care about how the adults relate to one another, as long as they are taken care of. Overall, such children seem to fare well as long as they live in stable, loving homes.

Making this practice work, she acknowledges, is "time consuming and potentially fraught with emotional booby traps." People in polyamorous relationships emphasize that their relationships are about emotional connections with others, as opposed to primarily physical relationships.

The term polyfidelity, a subset of polyamory, was coined in the 1970s by members of the Kerista commune, which started in New York City in 1956. Polyfidelity is a concept in which clusters of friends form nonmonogamous sexual relationships. Under this family structure, group members do not relate sexually to anyone outside of the family group.

Although mainstream Judaism does not accept polyamory, some people do consider themselves Jewish and polyamorous. Sharon Kleinbaum, the senior rabbi at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York, has said that polyamory is a choice that does not preclude a Jewishly observant, socially conscious life. Some polyamorous Jews also point to biblical patriarchs having multiple wives and concubines as evidence that polyamorous relationships can be sacred in Judaism.

Jim Fleckenstein, director of the Institute for 21st-Century Relationships, has said that the polyamory movement has been driven by science fiction and feminism. He states that disillusionment with monogamy occurs "because of widespread cheating and divorce."

One fact going for the polys (as they are often known), is the belief that polyamory is more honest and less hypocritical than monogamy with secret affairs. A manual, "What Psychology Professionals Should Know About Polyamory," for psychotherapists who deal with polyamorous clients, was published in September 2009 by the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom.

The late Michael Shernoff, who was an openly gay psychotherapist, wrote that nonmonogamy is "a well-accepted part of gay subculture," and that somewhere between 30% and 67% of men in male couples reported being in a sexually nonmonogamous relationship. A majority of male couples are not sexually exclusive, but describe themselves as emotionally monogamous.

Mr. Shernoff stated: One of the biggest differences between male couples and mixed-sex couples is that many, but by no means all, within the gay community have an easier acceptance of sexual nonexclusivity than does heterosexual society in general. Research confirms that nonmonogamy in and of itself does not create a problem for male couples when it has been openly negotiated (Fam. Process. 2006;45:407-18).

The role of affairs in marriage can now be subjected to a more nuanced discussion, after digesting the above views and practice of marriage. What is the meaning of an affair? What is an open relationship? What are the models of intimacy? Is an affair a breach in the couple’s definition of intimacy? What are the rules? How does a couple define an affair within the context of their own relationship?

Conclusion

Postmodernism provides family therapists a new set of theories and a new language for describing the variety of families. As Jacqueline Hudak, Ph.D., and Shawn V. Giammattei, Ph.D., have written: "As family therapists, we are uniquely poised to transform the meanings attached to ‘marriage’ and ‘family,’ to focus on the quality of relationships rather than on the gender of a partner or the assumption of particular roles" ("Expanding Our Social Justice Practices: Advances in Theory and Practice," Washington: American Family Therapy Academy, Winter 2010).

The traditional view of marriage is referred to as "heteronormativity" and is defined by the belief that a viable family consists of "a heterosexual mother and a father raising heterosexual children together" ("Handbook of Qualitative Research," Thousand Oaks, Calif.:Sage, 2000). Despite the above expansion of views on marriage and families, heteronormativity remains the current organizing principle of family theory, practice, research, and training. It will take many decades to shift the dominant paradigm. Developing awareness, and listening to families and couples is the first step.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

An earlier column reviewed the institution of marriage up to the middle of the last century. Since the 1950s, postmodernism has been gathering momentum, beginning as a critique of art, architecture, philosophy, and how we think about society and culture. Views on many aspects of our lives, as we live it, began to change.

Postmodernism stands in contrast to the "modern’ " or scientific view that touts a singularity of truth and a singular view of the world. Social construction is a type of postmodern theory that states that truth, reality, and knowledge are based in the social context of that particular person. This aspect of postmodernism is most applicable to mental health professionals assessing and treating patients, and to families in specific social and cultural contexts.

A postmodern view of the family considers the traditional view of the family, the "nuclear family," as only one view. Other forms of family and other views of marriage that had been marginalized, considered deviant and nonconforming, are now brought forward and considered as viable alternatives. Postmodernism discards many assumptions that we have been taught. One assumption that is being reexamined, for example, is that sexual nonexclusivity or extra-relationship sex, or romantic involvements are symptoms of troubled relationships or forms of sexual acting out.

Another assumption that needs to be reexamined is the notion that family structures found in other cultures are "abnormal" or dysfunctional. These assumptions are not necessarily true or false but require assessment in context of the relationship at hand. Postmodernism challenges us to assess each family variation on its own merit.

Beginnings

In the 20th century, Monica McGoldrick, Ph.D., one of the strong voices in family therapy, advocated for increased sensitivity to cultural variation. Her book, "Ethnicity and Family Therapy" (New York: The Guilford Press, 2005), describes characteristics of common ethnicities in American society.

Family therapists have attempted to address "nontraditional" families with articles, for example, about raising a biracial child, what to do if your child identifies as gay, etc. Most older articles focused on helping families "cope" with the nontraditional. Family therapists are now more willing to acknowledge "difference" as a normal rather than a pathological variant, and to recognize strengths inherent in diversity.

Acknowledging diversity

Marlene F. Watson, Ph.D., brings a nuanced understanding of the African American family, detailing the effect of slavery on the individuals in the family, and how internalized racism can be recognized and managed in family therapy (e-book, "Facing the Black Shadow," 2013). This is an important book for therapists, especially those who come from traditional families, as it articulates the reality of African American lives in a way that therapists can apply to clinical practice.

Dr. Watson illustrates through case examples how internalized racism affects marriages, and offers effective ways to help couples negotiate and overcome the negative aspects of their heritage. A postmodern stance also will help the couple recognize the resilience and strengths that are inherent in overcoming adversity.

Linda M. Burton, Ph.D., and Cecily R. Hardaway, Ph.D., highlight the role of "othermothers" in raising children in low-income families, be they white, Latino, or African American. They define "othermothering" as a form of coparenting, distinct from stepparenting. Women othermother children who are their romantic partners’ children from previous and concurrent relationships. Compared to stepfamilies, these multiple partner fertility relationships are more prevalent among young couples with limited financial resources, contentious relationships, and serial childbearing through serial repartnering.

In general, low-income women and women of color take on this style of coparenting to help the biological parents of relatives and friends who have limited social and psychological capital to protect and raise "good children"(Fam. Process. 2012;51:343-59). Family therapists will become much more effective if they understand and recognize that the motivation behind this form of mothering fosters resilience in the mothers. The more we know and understand alternate family structures, the more we can work toward building and sustaining resilience.

Assimilation has for many decades been the main focus of political and therapeutic endeavors. In postmodern times, transnationalism described a new way of thinking about relationships that extend across national boundaries and cultures (Fam. Process. 2007;46:157-71).

Immigrants maintain connections with their countries of origin with children who are parented by grandparents, or other relatives, perhaps in several countries at the same time. Family members use Skype, often daily, to connect with the matriarch or patriarch "back home."

Postmodern theories of social justice and cultural diversity work well with immigrants, bringing multiple perspectives into the treatment room. Immigrants bring many complex and diverse values in relation to marriage, gender, parenting, and religious practices. A social justice approach focuses on the racism and discrimination that is common in the lives of immigrants. Marriage might take place across nations, be arranged, or might be mixed race or mixed nationalities. Therapy that acknowledges these complexities will be most helpful. We still need to think further about global family life, how relationships evolve over long distances, and how to develop systemic and transnational interventions for separations and reunifications.

Sex and marriage

Nelson Mandela’s father had four wives, and he reported in an interview that he considered all of them his mothers and gained support from them all.

Polygamy has flourished in Africa and Asia for centuries, and more than 40 countries recognize polygamous marriages. In the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan, rich Kazakhs used to buy second wives from parents, often in exchange for livestock. Since Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, polygamy, although illegal, has again become common practice and is a status symbol for rich Kazakhs. Polygamy reportedly also is a way out of poverty for young women who save money and support their relatives back home

In the United Kingdom, polygamy has become more common in Muslim communities. Successful British Muslim women, who have delayed marriage to build careers, may choose to become a co-wife. They choose to share a husband in a relationship that they see as sanctioned by Islam. These women retain an independent lifestyle. "I didn’t want a full-time husband," one Muslim woman noted in an interview.

In the United States, the practice of polygamy was officially ended in the Mormon church in 1890. Nevertheless, several small "fundamentalist" groups continue the practice. One family of 14 wives and 17 children, the Browns of Nevada, are stars of a reality show that they reportedly hope educates the public about the choice.

Polyandry, a woman with multiple husbands, is described in many cultures. This practice frequently involves the marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife, which allows family-owned land to remain undivided. In some cultures, such as the Inuit, a man might arrange a second husband (frequently his brother) for his wife because he knows that, when he is absent, the second husband will protect his wife. Should she become pregnant while he is gone, it would be by someone he had approved in advance.

Penn State’s Stephen Beckerman, Ph.D., and his colleagues, in their study of the Bari people of Venezuela, found that children understood to have two fathers are significantly more likely to survive to age 15 than are children with only one. This is called "informal polyandry," because while the two fathers might not be formally married to and living with the mother in all cases, the society around them officially recognizes both men as legitimate mates to the mother, and father to her child.

Polyamory, the practice of open, multiple-partner relationships, is a structure that is increasingly common in Western countries, according to sociologist Elisabeth Sheff, Ph.D. Dr. Sheff’s 15 years of research leads her to believe that polyamory is a "legitimate relationship style that can be tremendously rewarding for adults and provide excellent nurturing for children."

She said she has found that children aged 5-8 do not seem to care about how the adults relate to one another, as long as they are taken care of. Overall, such children seem to fare well as long as they live in stable, loving homes.

Making this practice work, she acknowledges, is "time consuming and potentially fraught with emotional booby traps." People in polyamorous relationships emphasize that their relationships are about emotional connections with others, as opposed to primarily physical relationships.

The term polyfidelity, a subset of polyamory, was coined in the 1970s by members of the Kerista commune, which started in New York City in 1956. Polyfidelity is a concept in which clusters of friends form nonmonogamous sexual relationships. Under this family structure, group members do not relate sexually to anyone outside of the family group.

Although mainstream Judaism does not accept polyamory, some people do consider themselves Jewish and polyamorous. Sharon Kleinbaum, the senior rabbi at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York, has said that polyamory is a choice that does not preclude a Jewishly observant, socially conscious life. Some polyamorous Jews also point to biblical patriarchs having multiple wives and concubines as evidence that polyamorous relationships can be sacred in Judaism.

Jim Fleckenstein, director of the Institute for 21st-Century Relationships, has said that the polyamory movement has been driven by science fiction and feminism. He states that disillusionment with monogamy occurs "because of widespread cheating and divorce."

One fact going for the polys (as they are often known), is the belief that polyamory is more honest and less hypocritical than monogamy with secret affairs. A manual, "What Psychology Professionals Should Know About Polyamory," for psychotherapists who deal with polyamorous clients, was published in September 2009 by the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom.

The late Michael Shernoff, who was an openly gay psychotherapist, wrote that nonmonogamy is "a well-accepted part of gay subculture," and that somewhere between 30% and 67% of men in male couples reported being in a sexually nonmonogamous relationship. A majority of male couples are not sexually exclusive, but describe themselves as emotionally monogamous.

Mr. Shernoff stated: One of the biggest differences between male couples and mixed-sex couples is that many, but by no means all, within the gay community have an easier acceptance of sexual nonexclusivity than does heterosexual society in general. Research confirms that nonmonogamy in and of itself does not create a problem for male couples when it has been openly negotiated (Fam. Process. 2006;45:407-18).

The role of affairs in marriage can now be subjected to a more nuanced discussion, after digesting the above views and practice of marriage. What is the meaning of an affair? What is an open relationship? What are the models of intimacy? Is an affair a breach in the couple’s definition of intimacy? What are the rules? How does a couple define an affair within the context of their own relationship?

Conclusion

Postmodernism provides family therapists a new set of theories and a new language for describing the variety of families. As Jacqueline Hudak, Ph.D., and Shawn V. Giammattei, Ph.D., have written: "As family therapists, we are uniquely poised to transform the meanings attached to ‘marriage’ and ‘family,’ to focus on the quality of relationships rather than on the gender of a partner or the assumption of particular roles" ("Expanding Our Social Justice Practices: Advances in Theory and Practice," Washington: American Family Therapy Academy, Winter 2010).

The traditional view of marriage is referred to as "heteronormativity" and is defined by the belief that a viable family consists of "a heterosexual mother and a father raising heterosexual children together" ("Handbook of Qualitative Research," Thousand Oaks, Calif.:Sage, 2000). Despite the above expansion of views on marriage and families, heteronormativity remains the current organizing principle of family theory, practice, research, and training. It will take many decades to shift the dominant paradigm. Developing awareness, and listening to families and couples is the first step.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Thinking about the institution of marriage – Part I

Throughout history, views of marriage have evolved as societies change. Since the 6th century, the Roman Catholic Church has played a prominent role in thinking and developing our ideas about marriage and family. In October, the church sent out a document that included a questionnaire to its bishops around the world to find out what Catholics think about the "modern family." The Vatican sent out the document in preparation for the Synod of Bishops on the Family, which is slated for October 2014. Before we get the results, let’s review how society has reflected on marriage and family.

Historically, marriages often were strategic alliances between families. It was common for marriage to be between first and second cousins in order to strengthen family ties. Polygamy has been common throughout history and continues in many communities to this day.

Monogamy is also found throughout history, but in 1215, the Catholic Church decreed that partners had to publicly post notices of an impending marriage in a local parish to cut down on the number of invalid marriages. Until the 1500s, the Catholic Church accepted a couple’s word that they had exchanged marriage vows, with no witnesses or corroborating evidence needed. In the 1500s, with the rise in Protestantism, marriage became a civil matter rather than a sacrament. By 1639, states such as Massachusetts began requiring marriage licenses, and by the 19th century, marriage licenses were common in the United States.

Marriage through the ages

Here is a listing of the way in which marriage has been conceptualized over the years:

Arranged alliances: A strategic alliance between families.

Family ties: Keeping alliances within the family; the majority of all marriages throughout history were between first and second cousins.

Polygamy: A phenomenon that has been common throughout history.

Babies optional: In many early cultures, men could dissolve a marriage or take another wife if a woman was infertile. However, the early Christian church was a trailblazer in arguing that marriage was not contingent upon producing offspring.

Monogamy: This practice became the guiding principle for Western marriages between the 6th and 9th centuries because of the church.

Sacred vs. secular: In 1215, the Roman Catholic Church decreed that partners had to publicly post notices, or banns, of an impending marriage in a local parish in order to cut down on the number of invalid marriages. Until the 1500s, the church accepted a couple’s word that they had exchanged marriage vows, with no witnesses or corroborating evidence needed.

Civil marriage: By 1639, states such as Massachusetts began requiring marriage licenses and, by the 19th century, marriage licenses were common in the United States.

Romance: By the 1900s, mutual attraction became important.

Market economics: Families historically controlled access to inheritance of agricultural land, but with the spread of a market economy, it becomes possible for people to marry outside of this inheritance.

Women’s equality: About 50 years ago, in Western countries, women and men began to have equal rights and responsibilities. Instead of being about unique, gender-based roles, most partners conceived of their unions in terms of flexible divisions of labor, companionship, and mutual sexual attraction.

Same-sex marriages: One of the reasons for the stunningly rapid increase in acceptance of same-sex marriage is because heterosexuals have completely changed their notion that all marriages are between a man and a woman, notes Stephanie Coontz, Ph.D. "We now believe marriage is based on love, mutual sexual attraction, equality, and a flexible division of labor."

Source: Adapted from "Marriage, a History: From Obedience to Intimacy, or How Love Conquered Marriage," (New York: Viking, 2005), by Dr. Coontz.

A sacred view of marriage

The Catholic position throughout history has been that marriage is one of the seven sacraments bestowed by Christ. This questionnaire is an attempt by the Vatican to understand more about "mixed or interreligious marriages; the single-parent family; polygamy; marriages with the consequent problem of a dowry, sometimes understood as the purchase price of the woman; the caste system; a culture of noncommitment and a presumption that the marriage bond can be temporary; forms of feminism hostile to the Church; migration and the reformulation of the very concept of the family; relativist pluralism in the conception of marriage; the influence of the media on popular culture in its understanding of marriage and family life; underlying trends of thought in legislative proposals which devalue the idea of permanence and faithfulness in the marriage covenant; an increase in the practice of surrogate motherhood (wombs for hire); and new interpretations of what is considered a human right."

Thirty-nine questions are on the questionnaire. Questions 4, 5, and 6 are of most interest to family psychiatrists. Deserving of admiration is its concern for families in migration and for the mistreatment of women.

The terms "regular" and "irregular," used in the questionnaire, are canonical terms unrelated to what actually happens in any given society. It should also be explained that Catholics who married always had to declare that they would welcome such children as God happened to send along, recognizing that he might choose not to send any. A decision to refuse to accept the possibility of children invalidated the marriage vows and constitutes grounds for annulment.

Excerpts from the Vatican document

Questions 4, 5, and 6 of the Vatican’s questionnaire seem aimed at gathering data on different kinds of families. Here are those three questions:

Pastoral Care in Certain Difficult Marital Situations

a) Is cohabitation ad experimentum a pastoral reality in your particular Church? Can you approximate a percentage?

b) Do unions which are not recognized either religiously or civilly exist? Are reliable statistics available?

c) Are separated couples and those divorced and remarried a pastoral reality in your particular Church? Can you approximate a percentage? How do you deal with this situation in appropriate pastoral programmes? (sic)

d) In all the above cases, how do the baptized live in this irregular situation? Are they aware of it? Are they simply indifferent? Do they feel marginalized or suffer from the impossibility of receiving the sacraments?

f) Could a simplification of canonical practice in recognizing a declaration of nullity of the marriage bond provide a positive contribution to solving the problems of the persons involved? If yes, what form would it take?

Does a ministry exist to attend to these cases? Describe this pastoral ministry? Do such programmes exist on the national and diocesan levels? How is God’s mercy proclaimed to separated couples and those divorced and remarried, and how does the Church put into practice her support for them in their journey of faith?

On Unions of Persons of the Same Sex

a) Is there a law in your country recognizing civil unions for people of the same-sex and equating it in some way to marriage?

b) What is the attitude of the local and particular Churches towards both the State as the promoter of civil unions between persons of the same sex and the people involved in this type of union?

c) What pastoral attention can be given to people who have chosen to live in these types of union?

In the case of unions of persons of the same sex who have adopted children, what can be done pastorally in light of transmitting the faith?

The Education of Children in Irregular Marriages

a) What is the estimated proportion of children and adolescents in these cases, as regards children who are born and raised in regularly constituted families?

b) How do parents in these situations approach the Church? What do they ask? Do they request the sacraments only or do they also want catechesis and the general teaching of religion?

c) How do the particular Churches attempt to meet the needs of the parents of these children to provide them with a Christian education?

Source: Pastoral Challenges to the Family in the Context of Evangelization

A secular view of marriage

A secular view of marriage has been advanced by economists Betsey Stevenson, Ph.D., and Justin Wolfers, Ph.D., who describe the extent to which marriage is shaped by economic forces. "Productive marriage" is based on a division of labor. In the earlier part of the 20th century in Western countries, school, education, and the emerging TV and magazine markets illustrated how women could be good homemakers and men could be good providers. The liberation of women through education and access to birth control changed the playing field. Prior to this, college-educated women were the least likely to marry. Since the 1960s and 1970s, educated women could prevent pregnancy and support themselves, and found little use for the previous productive model of marriage.

Men, also, did not see educated, financially independent women as suitable marriage partners. The high divorce rate among those who married in the1970s reflected discontent with this model of the productive marriage.

In contrast, Dr. Stevenson and Dr. Wolfers write, "hedonic marriage" occurs when people who marry are of similar age, educational background, and perhaps occupation. The hedonic marriage better suits educated women who seek a companion, and it thrives when time and resources are available to enjoy companionable life. Same-sex marriages make sense when considered in this broad frame. Supporting this concept is the fact that couples who have married in recent years are more likely to stay together than were their parents’ generation. Of course, this discourse is only relevant in parts of the world in which women have access to birth control and opportunities for education, work, and social standing.

Romance and marriage

The question of romance in marriage is the hardest for psychiatrists, as scientists, to address. Romance has always been around, sometimes present in marriages and sometimes not. Romance is thought to be both essential and nonessential to marriage, depending on the purpose of the marriage. A good discussion by Dr. Henry Grunebaum can be found an article titled "Thinking about romantic/erotic love" in the Journal of Marital and Family Therapy(1997;23:295-307). His main points are that we do not have control over our feelings of romantic/erotic love, that these feelings occur relatively infrequently during most people’s lives, that being with a partner whom one loves, is valued and regarded as a good, that it sometimes conflicts with other values and goods, and lastly that although love is regarded as one essential basis for marriage, other qualities and capacities are important in sustaining a long-term relationship such as a marriage. He concludes with, "What makes matters even more challenging is the fact that we ask a great deal of marriage, of any serious intimate relationship. Perhaps the greatest demand we make is that it should combine passion and stability, romance and monogamy, transports of tenderness and excitement from the person who will also perform the many mundane tasks of daily living. In other words, meld everyday love with romantic/erotic love." He offers suggestions for discussion and guidelines for therapists.

Applying all of this in our work

As family psychiatrists, we can allow couples and families a therapeutic space to discuss the meaning and assumptions in their marriage. We can discuss the frame of the marriage: Is it sacred, secular, or postmodern? In this way, we can provide a context to the current struggles that couples and families might have.

To begin, we can ask about the past. We can say, "People get married for different reasons. What were your reasons? Do you consider your marriage to be a sacred or a secular? What does this mean to you?"

Delving deeper and focusing more on the present, "What is your current experience of your marriage? How do your expectations differ now than from your expectations in the past? What is the role of romance in your marriage?

What type of marriage did you want when you began this marriage? Is there romance in your marriage? What kind of marriage do you want now?

Focusing on going forward we can ask: "What works well in your marriage/family? What are your strengths? What needs to change in your marriage?"

In the late 1970s, postmodernism emerged in the world. Postmodernism stands in contrast to the "modern" or scientific view that touts a singularity of truth and a singular view of the world. Social construction is a type of postmodern theory that states that truth, reality, and knowledge are based in the social context of that particular person. Inevitably, postmodernism affects how we think about and conceptualize marriage. Postmodernism and marriage will be the subject of the next column.

I would like to thank Peter Chaloner, M.A., LL.B, B.A. (Honors), and Dip. Theo., for his comments and corrections.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Throughout history, views of marriage have evolved as societies change. Since the 6th century, the Roman Catholic Church has played a prominent role in thinking and developing our ideas about marriage and family. In October, the church sent out a document that included a questionnaire to its bishops around the world to find out what Catholics think about the "modern family." The Vatican sent out the document in preparation for the Synod of Bishops on the Family, which is slated for October 2014. Before we get the results, let’s review how society has reflected on marriage and family.

Historically, marriages often were strategic alliances between families. It was common for marriage to be between first and second cousins in order to strengthen family ties. Polygamy has been common throughout history and continues in many communities to this day.