User login

Diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder in primary care

Patients presenting with depression commonly have undiagnosed bipolar depression,1–7 that is, depression with shifts to periods of mania. During manic or hypomanic episodes, people feel energetic, need little sleep, and are often happy and charming.8 But too much of a good thing can also wreak havoc on their life.

Bipolar depression (ie, depression in patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder) is treated differently from unipolar depression,3,9–13 making it especially important that clinicians recognize if a patient who presents with depression has a history of (hypo)manic symptoms.

CASE 1: THE IMPULSIVE NURSE

A 32-year-old nurse presents to her primary care provider with depressed mood. She reports having had a single depressive episode when she was a college freshman. Her family history includes depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, and her paternal grandfather and a maternal aunt committed suicide. Upon questioning, she reveals that in the past, she has had 3 episodes lasting several weeks and characterized by insubordinate behavior at work, irritability, high energy, and decreased need for sleep. She regrets impulsive sexual and financial decisions that she made during these episodes and recently filed for personal bankruptcy. For the past month, her mood has been persistently low, with reduced sleep, appetite, energy, and concentration, and with passive thoughts of suicide.

A CAREFUL HISTORY IS CRITICAL

This case illustrates many typical features of bipolar depression that are revealed only by taking a thorough history. Although the patient is high-functioning, having attained a professional career, she has serious problems with sexual and financial impulsivity and at her job. She has a strong family history of mood disorder. And she describes episodes of depression and mania in the past.

Starts in young adulthood, strong heritability

Bipolar disorder can be a devastating condition with lifelong consequences,14–20 especially as it typically starts when patients are getting an education or embarking on a career. It usually first manifests in the late teenage years and progresses in the patient’s early 20s.21,22 The first hospitalization can occur soon thereafter.23,24

Bipolar disorder is one of the most heritable conditions in psychiatry, and about 13% of children who have an afflicted parent develop it.25 In identical twins, the concordance is about 50% to 75%, indicating the importance of genetics and environmental factors.26,27

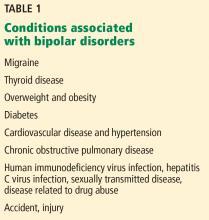

Associated with migraine, other conditions

The disorder is associated with a variety of conditions (Table 1).28,29 Some conditions (eg, thyroid disease) can cause mood cycling, and some (eg, sexually transmitted infections, accidents) are the consequences of the lifestyle that may accompany mania. For unknown reasons, migraine is highly associated with bipolar disorder.

DEPRESSION AND MANIA: TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Symptoms of depression and mania are frequently viewed as opposite mood states, though many times patients report a mixture of them.17,30–35 For both states, the features of a distinct change from the patient’s normal condition and the sustained nature of the symptoms are important diagnostically and indicate a likely underlying biological cause.

Major depressive disorder: Slowing down

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),8 defines major depressive disorder as having either depressed mood or markedly diminished pleasure in most activities for most days during at least 2 weeks.

In addition, at least 4 of the following must be present during the same period:

- Appetite disturbance

- Sleep disturbance

- Motor retardation or agitation

- Lack of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt

- Decreased concentration

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

An estimated 20% of the population experience a major depressive episode over their lifetime. A surprisingly high proportion of people with depression—30% to 40%—also have had subthreshold symptoms of mania (symptoms not meeting the criteria for hypomania or mania in terms of number of symptoms or duration).21,22 Because of these odds, it is important to suspect bipolar disorder even in patients who present with depression but who may not yet have manifested episodes of mania or hypomania.

Mood disorders can be regarded as falling into a spectrum, ranging from unipolar or “pure” major depression without any features of hypomania to major depression and severe mania.17,31–36

Mania: Speeding up

The DSM-5 defines mania as the presence of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood with increased activity for more than 1 week. In addition, at least 3 of the following features must be present, with impaired functioning (4 features are required if mood is only irritable)8:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- Pressured speech

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Excessive involvement in pleasurable, high-risk activities.

Hypomania: No functional impairment

Hypomania is a less severe condition, in which the abnormally elevated mood is of shorter duration (4–7 days) and meets the other criteria for mania but without significant functional impairment. People may, in fact, be very functional and productive during hypomanic episodes.8

CLASSIFYING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Bipolar disorder is categorized according to severity.24,37,38 The most severe form, bipolar I disorder, is marked by major depression and manic episodes. It affects up to 1.5% of the US population, with equal proportions of men and women.39 Bipolar II disorder is less severe. It affects 0.8% to 1.6% of the US population, predominantly women.21,40 In bipolar II disorder, depression is more prominent, with episodes of hypomania.

Subthreshold bipolar disorders are characterized by episodic symptoms that do not meet the threshold for depression or hypomania; the symptoms are fewer or of shorter duration. These minor types of bipolar disorder affect up to 6% of the US population.17

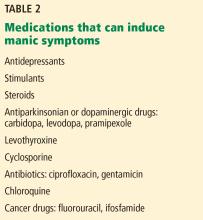

Other conditions within the spectrum of bipolar and depressive disorders include medication- and substance-induced mania, agitated or anxious depression, and mixed states.31,34–36

DISTINGUISHING UNIPOLAR FROM BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Considerable research has focused on finding a clear-cut clinical or biological feature to differentiate unipolar from bipolar depression, but so far none has been discovered. Distinguishing the two conditions still depends on clinical judgment. There are important reasons to identify the distinction between unipolar depression and bipolar disorder.

Prognosis differs. Bipolar disorder tends to be a more severe condition. Young people, who may initially present with only mild symptoms of mania, may develop serious episodes over the years. People may lose their savings, their marriage, and their career during a manic episode. The more critical the occupation (eg, doctor, pilot), the greater the potential consequences of impaired judgment brought on by even mild hypomania.14–20

Treatment differs. Typical antidepressants given for depression can trigger a manic episode in patients with bipolar depression, with devastating consequences. Atypical neuroleptic drugs used to treat bipolar disorder can also have serious effects (eg, metabolic and neurologic effects, including irreversible tardive dyskinesia).3,13,40–43

Despite the good reasons to do so, many doctors (including some psychiatrists) do not ask their patients about a propensity to mania or hypomania.4–6 More stigma is attached to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder than to depression44–47; once it is in the medical record, the patient may have problems with employment and obtaining medical insurance.17,44 The old term “manic-depressive” is often associated in the public mind with a person on the streets displaying severely psychotic behavior; the condition is now understood to consist of a spectrum from mild to more severe illness.

Clinical indicators of bipolarity

There are many indicators that a person who presents with depression may be on the bipolar spectrum, but this is not always easily identified.48–53

History of hypomanic symptoms or subthreshold manic symptoms. Although directly asking the patient about the defining symptoms (eg, “Have you ever had episodes of being ‘hyper’ or too happy?”) may help elicit the diagnosis, many patients with bipolar disorder only report depression, as it is psychically painful. In contrast, hypomania and even mania can be perceived as positive, as patients may have less insight into the abnormality of the condition and feel that they are functioning extremely well.

Early age of onset of a mood disorder, such as severe depression in childhood or early adulthood, points toward bipolar disorder. Diagnosing mood disorders in childhood is difficult, as children are less able to recognize or verbalize many of their symptoms.

Postpartum mood disorder, particularly with psychotic symptoms, indicates a strong possibility of a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Drug-induced mania, hypomania, and periods of hyperactivity are key features of bipolar disorder. If asked, patients may report feeling a “buzz” when taking an antidepressant.

Erratic patterns in work and relationships are a red flag and are viewed as “soft signs” of bipolar depression. Akiskal54 described the “rule of three” that should make one consider bipolar disorder: for example, three failed marriages, three current jobs or frequent job changes, three distinct professions practiced at the same time, and simultaneously dating three people. Such features indicate both the hyperfunctioning and the disruptive aspects of mania.

Family history of bipolar disorder or severe psychiatric illness is a very important clue. A more subtle clue described by Akiskal54 may be that several members of the family are very high-functioning in several different fields: eg, one may be a highly accomplished doctor, another a famous lawyer, and another a prominent politician. Or several members of the family may have erratic patterns of work and relationships. However, these subtle clues have been derived from clinical experiences and have not been validated in large-scale studies.

CASE 2: THE FRIENDLY SURGEON

Dr. Z is a prominent surgical subspecialist who is part of a small group practice. His wife has become increasingly worried about his behavior changes at home, including sleeping only a few hours a night, spending sprees, and binge drinking. He reluctantly agrees to an outpatient psychiatric evaluation if she attends with him. He creates a disturbance in the waiting room by shaking everyone’s hands and trying to hug all the women. During his examination, he is loud and expansive, denying he has any problems and describing himself as “the greatest doctor in the world.” The psychiatrist recommends hospitalization, but Dr. Z refuses and becomes belligerent. He announces that he just needs a career change and that he will fly to Mexico to open a bar.

This case, from the Texas Medical Association Archives,55 is not unusual. In addition to many characteristics discussed above, this case is typical in that the spouse brought the patient in, reflecting that the patient lacked insight that his behavior was abnormal. The disinhibition (hugging women), grandiosity, and unrealistic plans are also typical.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Anxiety disorders may be associated with dissociative speech or racing thoughts, which can be confused with bipolar illness. Personality disorders (eg, borderline, narcissistic, sociopathic) can involve a tumultuous and impulsive lifestyle resembling episodes of depression and mania. Schizoaffective illness has features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

It is also possible that, despite what may look like mild features of bipolar disorder, there is no psychiatric condition. Some people with mild mania—often successful professionals or politicians—have high energy and can function very well with only a few hours of sleep. Similarly, depressive symptoms for short periods of time can be adaptive, such as in the face of a serious setback when extreme reflection and a period of inactivity can be useful, leading to subsequent reorganization.

A psychiatric diagnosis is usually made only when there is an abnormality, ie, the behavior is beyond normal limits, the person cannot control his or her symptoms, or social or occupational functioning is impaired.

SCREENING INSTRUMENTS

A few tools help determine the likelihood of bipolar disorder.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)59,60 is a good 9-item screening tool for depression.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire60 is specific for bipolar disorder, and like the PHQ-9, it is a patient-reported, short questionnaire that is available free online. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire asks about the symptoms of mania in a yes-no format. The result is positive if all of the following are present:

- A “yes” response to 7 of the 13 features

- Several features occur simultaneously

- The features are a moderate or serious problem.

Unlike most screening instruments, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire is more specific than sensitive. It is 93% specific for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a primary care setting, but only 58% sensitive.61–63

WHEN TO REFER TO PSYCHIATRY

Patients suspected of having bipolar disorder or who have been previously diagnosed with it should be referred to a psychiatrist if they have certain features, including:

- Bipolar I disorder

- Psychotic symptoms

- Suicide risk or in danger of harming others

- Significantly impaired functioning

- Unclear diagnosis.

CASE 3: A TELEVISION ANCHOR’S DREAM TURNS TO NIGHTMARE

According to a famous news anchor’s autobiography,64 the steroids prescribed for her hives “revved her up.” The next course left her depressed. Antidepressant medications propelled her into a manic state, and she was soon planning a book, a television show, and a magazine all at once. During that time, she bought a cottage online. Her shyness evaporated at parties. “I was suddenly the equal of my high-energy friends who move fast and talk fast and loud,” she wrote. “I told everyone that I could understand why men felt like they could run the world, because I felt like that. This was a new me, and I liked her!”64 She was soon diagnosed with bipolar disorder and admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

TREAT WITH ANTIDEPRESSANTS, MOOD STABILIZERS

In general, acute bipolar disorder should be treated with a combination of an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer, and possibly an antipsychotic drug. An antidepressant should not be used alone, particularly with patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, because of the risk of triggering mania or the risk of faster cycling between mania and depression.13

Mood stabilizers include lithium, lamotrigine, and valproate. Each can prevent episodes of depression and mania. Lithium, which has been used as a mood stabilizer for 60 years, is specific for bipolar disorder, and it remains the best mood stabilizer treatment.

Antidepressants. The first-line antidepressant medication is bupropion, which is thought to be less likely to precipitate a manic episode,65 though all antidepressants have been associated with this side effect in patients with bipolar disorder. Other antidepressants—for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine and dual reuptake inhibitors such as venlafaxine and duloxetine—can also be used. The precipitation of mania and possible increased mood cycling was first described with tricylic antidepressants, so drugs of this class should be used with caution.

Neuroleptic drugs such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lurasidone may be the easiest drugs to use, as they have antidepressant effects and can also prevent the occurrence of mania. These medications are frequently classified as mood stabilizers. However, they may not have true mood stabilizing properties such as that of lithium. Importantly, their use tends to entail significant metabolic problems and can lead to hyperlipidemia and diabetes. In addition, Parkinson disease-like symptoms— and in some cases irreversible involuntary movements of the mouth and tongue, as well as the body (tardive dyskinesia)—are important possible side effects.

All psychiatric medications have potential side effects (Table 3). Newer antidepressants and neuroleptics may have fewer side effects than older medications but are not more effective.

Should milder forms of bipolar depression be treated?

A dilemma is whether we should treat milder forms of bipolar depression, such as bipolar II depression, depression with subthreshold hypomania symptoms, or depression in persons with a strong family history of bipolar disorder.

Many doctors are justifiably reluctant to prescribe antidepressants for depression because of the risk of triggering mania. Although mood stabilizers such as lithium would counteract possible mania emergence, physicians often do not prescribe them because of inexperience and fear of risks and possible side effects. Patients are likewise resistant because they feel that use of mood stabilizers is tantamount to being told they are “manic-depressive,” with its associated stigma.

Overuse of atypical neuroleptics such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and olanzapine has led to an awareness of metabolic syndrome and tardive dyskinesia, also making doctors cautious about using these drugs.

Answer: Yes, but treat with caution

Not treating depression consigns a patient to suffer with untreated depression, sometimes for years. Outcomes for patients with depression and bipolar disorder are often poor because the conditions are not recognized, and even when the conditions are recognized, doctors and patients may be reluctant to medicate appropriately. Medications should be used as needed to treat depression, but with an awareness of the possible side effects and with close patient monitoring.

A truly sustained manic state (unlike the brief euphoria brought on by some drugs) is not actually so easy to induce. In an unpublished Cleveland Clinic study, we monitored peaks of hypomanic symptoms in young patients (ages 15–30) during antidepressant treatment without mood stabilizers. About 30% to 40% of patients had subthreshold manic symptoms or a family history of bipolar disorder; 3 patients out of 51 developed hypomania leading to a change of diagnosis to bipolar disorder. Even in patients who had no risk factors for bipolar disorder, 2 out of 53 converted to a bipolar diagnosis. So conversion rates in patients with subthreshold bipolar disorder seem to be low, and the disorder can be identified early by monitoring the patient closely.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS FOR DEPRESSION

Psychotherapy is indicated for all patients on medications for depression, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments are more effective when combined.66 Other treatments include transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, and exercise. Having a consistent daily routine, particularly regarding the sleep-wake schedule, is also helpful, and patients should be educated about its importance.

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. Am Psychol 1998; 53(2):221–241. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.221

- Glick ID. Undiagnosed bipolar disorder: new syndromes and new treatments. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004;6(1):27–33. pmid:15486598

- Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(10):804–808. pmid:11078046

- Singh T, Rajput M. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006; 3(10):57–63. pmid: 20877548

- Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31(4):281–294. pmid:7989643

- Howes OD, Falkenberg I. Early detection and intervention in bipolar affective disorder: targeting the development of the disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2011; 13(6):493–499. pmid:21850462

- Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, Pandurangi AK, Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999; 52(1–3):135–144. pmid:10357026

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

- Hlastala SA, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Ritenour AM, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar depression: an underestimated treatment challenge. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5(2):73–83. pmid:9262937

- Smith DJ, Craddock N. Unipolar and bipolar depression: different or the same? Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199(4):272–274. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092726

- Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171(10):1067–1073. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111501

- Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007; 356(17):1711–1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064135

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(4 suppl):1–50. pmid:11958165

- Leonpacher AK, Liebers D, Pirooznia M, et al. Distinguishing bipolar from unipolar depression: the importance of clinical symptoms and illness features. Psychol Med 2015; 45(11):2437–2446. doi:10.1017/S0033291715000446

- Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1–2):133–146. pmid:12507746

- Faravelli C, Rosi S, Alessandra Scarpato M, Lampronti L, Amedei SG, Rana N. Threshold and subthreshold bipolar disorders in the Sesto Fiorentino Study. J Affect Disord 2006; 94(1–3):111–119. pmid:16701902

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1–2):123–131. pmid:12507745

- Park Y-M, Lee B-H. Treatment response in relation to subthreshold bipolarity in patients with major depressive disorder receiving antidepressant monotherapy: a post hoc data analysis (KOMDD study). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016; 12:1221–1227. doi:10.2147/NDT.S104188

- Perlis RH, Uher R, Ostacher M, Goldberg JF, et al. Association between bipolar spectrum features and treatment outcomes in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(4):351–360. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.179

- Dudek D, Siwek M, Zielin´ska D, Jaeschke R, Rybakowski J. Diagnostic conversions from major depressive disorder into bipolar disorder in an outpatient setting: results of a retrospective chart review. J Affect Disord 2013; 144(1–2):112–115. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.014

- Angst J, Cui L, Swendsen J, et al. Major depressive disorder with subthreshold bipolarity in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167(10):1194–1201. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09071011

- Zimmermann P, Brückl T, Nocon A, et al. Heterogeneity of DSM-IV major depressive disorder as a consequence of subthreshold bipolarity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66(12):1341–1352. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.158

- Patel NC, DelBello MP, Keck PE, Strakowski SM. Phenomenology associated with age at onset in patients with bipolar disorder at their first psychiatric hospitalization. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8(1):91–94. pmid:16411986

- Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(2):161–174. pmid:12633125

- Craddock N, Jones I. Genetics of bipolar disorder. J Med Genet 1999; 36(8):585–594. pmid:10465107

- Griswold KS, Pessar LF. Management of bipolar disorder. Am Fam Physician 2000; 62(6):1343–1358. pmid:11011863

- Kerner B. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Appl Clin Genet 2014; 7:33–42. doi:10.2147/TACG.S39297

- Scheffer RE, Linden S. Concurrent medical conditions with pediatric bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007; 20(4):398–401. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281a305c3

- Carney CP, Jones LE. Medical comorbidity in women and men with bipolar disorders: a population-based controlled study. Psychosom Med 2006;68(5):684–691. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000237316.09601.88

- Cassano GB, Akiskal HS, Savino M, Musetti L, Perugi G. Proposed subtypes of bipolar II and related disorders: with hypomanic episodes (or cyclothymia) and with hyperthymic temperament. J Affect Disord 1992; 26(2):127–140. pmid:1447430

- Akiskal HS, Mallya G. Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23(1):68–73. pmid:3602332

- Fiedorowicz JG, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Keller MB, Coryell WH. Subthreshold hypomanic symptoms in progression from unipolar major depression to bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168(1):40–48. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030328

- Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Bartoli L. Agitated “unipolar” major depression: prevalence, phenomenology, and outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(5):712–719. pmid:16841620

- Akiskal HS. The bipolar spectrum: new concepts in classification and diagnosis. In: Psychiatry Update: the American Psychiatric Association Annual Review. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1983:271–292.

- Akiskal HS, Pinto O. The evolving bipolar spectrum. Prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22(3):517–534. pmid:10550853

- Cassano GB, Savino M, Perugi G, Musetti L, Akiskal HS. Major depressive episode: unipolar and bipolar II. Encephale 1992 Jan;18 Spec No:15–18. pmid:1600898

- Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Berghöfer A, Bauer M. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2002; 359(9302):241–247. pmid:11812578

- Hirschfeld RMA, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(1):53–59. pmid:12590624

- Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 bipolar I disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions—III. J Psychiatr Res 2017; 84:310–317. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.003

- McGirr A, Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive second-generation antidepressant therapy with a mood stabiliser or an atypical antipsychotic in acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(12):1138–1146. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30264-4

- Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, Nolen WA, Goodwin GM. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161(9):1537–1547. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1537

- Sidor MM, Macqueen GM. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72(2):156–167. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05385gre

- Liu B, Zhang Y, Fang H, Liu J, Liu T, Li L. Efficacy and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment for bipolar disorders - A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 2017; 223(139):41–48. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.023

- Krupa T, Kirsh B, Cockburn L, Gewurtz R. Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work 2009; 33(4):413–425. doi:10.3233/WOR-2009-0890

- Hawke LD, Parikh SV, Michalak EE. Stigma and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2013; 150(2):181–191. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.030

- Cerit C, Filizer A, Tural Ü, Tufan AE. Stigma: a core factor on predicting functionality in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2012; 53(5):484–489. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.08.010

- O’Donnell L, Himle JA, Ryan K, et al. Social aspects of the workplace among individuals with bipolar disorder. J Soc Social Work Res 2017; 8(3):379–398. doi:10.1086/693163

- Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, et al. Switching from “unipolar” to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52(2):114–123. pmid:7848047

- Kroon JS, Wohlfarth TD, Dieleman J, et al. Incidence rates and risk factors of bipolar disorder in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15(3):306–313. doi:10.1111/bdi.12058

- Fiedorowicz JG, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Keller MB, Coryell WH. Subthreshold hypomanic symptoms in progression from unipolar major depression to bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168(1):40–48. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030328

- Akiskal HS, Walker P, Puzantian VR, King D, Rosenthal TL, Dranon M. Bipolar outcome in the course of depressive illness. Phenomenologic, familial, and pharmacologic predictors. J Affect Disord 1983; 5(2):115–128. pmid:6222091

- Strober M, Carlson G. Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacologic predictors in a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39(5):549–555. pmid:7092488

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Whiteside JE. Risk for bipolar illness in patients initially hospitalized for unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(8):1265–1270. pmid:11481161

- Akiskal HS. Searching for behavioral indicators of bipolar II in patients presenting with major depressive episodes: the “red sign,” the “rule of three” and other biographic signs of temperamental extravagance, activation and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2005; 84(2–3):279–290. pmid:15708427

- Texas Medical Association. Mood disorders in physicians. www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=6833. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- Hirschfeld RM. Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2014;169(suppl 1):S12–S16. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(14)70004-7

- Dunner DL. Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(1suppl):7S–12S. pmid:1541721

- Peet M, Peters S. Drug-induced mania. Drug Saf 1995; 12(2):146–153. pmid:7766338

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999; 282(18):1737–1744. pmid:10568646

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(9):606–613. pmid:11556941

- Hirschfeld RMMA, Williams JBBW, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(11)1873–1875. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873

- Hirschfeld RMA. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a simple, patient-rated screening instrument for bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 4(1):9–11. pmid: 15014728

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA 2005; 293(8):956–963. doi:10.1001/jama.293.8.956

- Pauley J. Skywriting: A Life Out of the Blue. New York: Random House, 2004.

- Goren JL, Levin GM. Mania with bupropion: a dose-related phenomenon? Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34(5):619–621. doi:10.1345/aph.19313

- Swann AC. Long-term treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(suppl 1):7–12. pmid:15693746

Patients presenting with depression commonly have undiagnosed bipolar depression,1–7 that is, depression with shifts to periods of mania. During manic or hypomanic episodes, people feel energetic, need little sleep, and are often happy and charming.8 But too much of a good thing can also wreak havoc on their life.

Bipolar depression (ie, depression in patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder) is treated differently from unipolar depression,3,9–13 making it especially important that clinicians recognize if a patient who presents with depression has a history of (hypo)manic symptoms.

CASE 1: THE IMPULSIVE NURSE

A 32-year-old nurse presents to her primary care provider with depressed mood. She reports having had a single depressive episode when she was a college freshman. Her family history includes depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, and her paternal grandfather and a maternal aunt committed suicide. Upon questioning, she reveals that in the past, she has had 3 episodes lasting several weeks and characterized by insubordinate behavior at work, irritability, high energy, and decreased need for sleep. She regrets impulsive sexual and financial decisions that she made during these episodes and recently filed for personal bankruptcy. For the past month, her mood has been persistently low, with reduced sleep, appetite, energy, and concentration, and with passive thoughts of suicide.

A CAREFUL HISTORY IS CRITICAL

This case illustrates many typical features of bipolar depression that are revealed only by taking a thorough history. Although the patient is high-functioning, having attained a professional career, she has serious problems with sexual and financial impulsivity and at her job. She has a strong family history of mood disorder. And she describes episodes of depression and mania in the past.

Starts in young adulthood, strong heritability

Bipolar disorder can be a devastating condition with lifelong consequences,14–20 especially as it typically starts when patients are getting an education or embarking on a career. It usually first manifests in the late teenage years and progresses in the patient’s early 20s.21,22 The first hospitalization can occur soon thereafter.23,24

Bipolar disorder is one of the most heritable conditions in psychiatry, and about 13% of children who have an afflicted parent develop it.25 In identical twins, the concordance is about 50% to 75%, indicating the importance of genetics and environmental factors.26,27

Associated with migraine, other conditions

The disorder is associated with a variety of conditions (Table 1).28,29 Some conditions (eg, thyroid disease) can cause mood cycling, and some (eg, sexually transmitted infections, accidents) are the consequences of the lifestyle that may accompany mania. For unknown reasons, migraine is highly associated with bipolar disorder.

DEPRESSION AND MANIA: TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Symptoms of depression and mania are frequently viewed as opposite mood states, though many times patients report a mixture of them.17,30–35 For both states, the features of a distinct change from the patient’s normal condition and the sustained nature of the symptoms are important diagnostically and indicate a likely underlying biological cause.

Major depressive disorder: Slowing down

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),8 defines major depressive disorder as having either depressed mood or markedly diminished pleasure in most activities for most days during at least 2 weeks.

In addition, at least 4 of the following must be present during the same period:

- Appetite disturbance

- Sleep disturbance

- Motor retardation or agitation

- Lack of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt

- Decreased concentration

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

An estimated 20% of the population experience a major depressive episode over their lifetime. A surprisingly high proportion of people with depression—30% to 40%—also have had subthreshold symptoms of mania (symptoms not meeting the criteria for hypomania or mania in terms of number of symptoms or duration).21,22 Because of these odds, it is important to suspect bipolar disorder even in patients who present with depression but who may not yet have manifested episodes of mania or hypomania.

Mood disorders can be regarded as falling into a spectrum, ranging from unipolar or “pure” major depression without any features of hypomania to major depression and severe mania.17,31–36

Mania: Speeding up

The DSM-5 defines mania as the presence of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood with increased activity for more than 1 week. In addition, at least 3 of the following features must be present, with impaired functioning (4 features are required if mood is only irritable)8:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- Pressured speech

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Excessive involvement in pleasurable, high-risk activities.

Hypomania: No functional impairment

Hypomania is a less severe condition, in which the abnormally elevated mood is of shorter duration (4–7 days) and meets the other criteria for mania but without significant functional impairment. People may, in fact, be very functional and productive during hypomanic episodes.8

CLASSIFYING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Bipolar disorder is categorized according to severity.24,37,38 The most severe form, bipolar I disorder, is marked by major depression and manic episodes. It affects up to 1.5% of the US population, with equal proportions of men and women.39 Bipolar II disorder is less severe. It affects 0.8% to 1.6% of the US population, predominantly women.21,40 In bipolar II disorder, depression is more prominent, with episodes of hypomania.

Subthreshold bipolar disorders are characterized by episodic symptoms that do not meet the threshold for depression or hypomania; the symptoms are fewer or of shorter duration. These minor types of bipolar disorder affect up to 6% of the US population.17

Other conditions within the spectrum of bipolar and depressive disorders include medication- and substance-induced mania, agitated or anxious depression, and mixed states.31,34–36

DISTINGUISHING UNIPOLAR FROM BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Considerable research has focused on finding a clear-cut clinical or biological feature to differentiate unipolar from bipolar depression, but so far none has been discovered. Distinguishing the two conditions still depends on clinical judgment. There are important reasons to identify the distinction between unipolar depression and bipolar disorder.

Prognosis differs. Bipolar disorder tends to be a more severe condition. Young people, who may initially present with only mild symptoms of mania, may develop serious episodes over the years. People may lose their savings, their marriage, and their career during a manic episode. The more critical the occupation (eg, doctor, pilot), the greater the potential consequences of impaired judgment brought on by even mild hypomania.14–20

Treatment differs. Typical antidepressants given for depression can trigger a manic episode in patients with bipolar depression, with devastating consequences. Atypical neuroleptic drugs used to treat bipolar disorder can also have serious effects (eg, metabolic and neurologic effects, including irreversible tardive dyskinesia).3,13,40–43

Despite the good reasons to do so, many doctors (including some psychiatrists) do not ask their patients about a propensity to mania or hypomania.4–6 More stigma is attached to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder than to depression44–47; once it is in the medical record, the patient may have problems with employment and obtaining medical insurance.17,44 The old term “manic-depressive” is often associated in the public mind with a person on the streets displaying severely psychotic behavior; the condition is now understood to consist of a spectrum from mild to more severe illness.

Clinical indicators of bipolarity

There are many indicators that a person who presents with depression may be on the bipolar spectrum, but this is not always easily identified.48–53

History of hypomanic symptoms or subthreshold manic symptoms. Although directly asking the patient about the defining symptoms (eg, “Have you ever had episodes of being ‘hyper’ or too happy?”) may help elicit the diagnosis, many patients with bipolar disorder only report depression, as it is psychically painful. In contrast, hypomania and even mania can be perceived as positive, as patients may have less insight into the abnormality of the condition and feel that they are functioning extremely well.

Early age of onset of a mood disorder, such as severe depression in childhood or early adulthood, points toward bipolar disorder. Diagnosing mood disorders in childhood is difficult, as children are less able to recognize or verbalize many of their symptoms.

Postpartum mood disorder, particularly with psychotic symptoms, indicates a strong possibility of a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Drug-induced mania, hypomania, and periods of hyperactivity are key features of bipolar disorder. If asked, patients may report feeling a “buzz” when taking an antidepressant.

Erratic patterns in work and relationships are a red flag and are viewed as “soft signs” of bipolar depression. Akiskal54 described the “rule of three” that should make one consider bipolar disorder: for example, three failed marriages, three current jobs or frequent job changes, three distinct professions practiced at the same time, and simultaneously dating three people. Such features indicate both the hyperfunctioning and the disruptive aspects of mania.

Family history of bipolar disorder or severe psychiatric illness is a very important clue. A more subtle clue described by Akiskal54 may be that several members of the family are very high-functioning in several different fields: eg, one may be a highly accomplished doctor, another a famous lawyer, and another a prominent politician. Or several members of the family may have erratic patterns of work and relationships. However, these subtle clues have been derived from clinical experiences and have not been validated in large-scale studies.

CASE 2: THE FRIENDLY SURGEON

Dr. Z is a prominent surgical subspecialist who is part of a small group practice. His wife has become increasingly worried about his behavior changes at home, including sleeping only a few hours a night, spending sprees, and binge drinking. He reluctantly agrees to an outpatient psychiatric evaluation if she attends with him. He creates a disturbance in the waiting room by shaking everyone’s hands and trying to hug all the women. During his examination, he is loud and expansive, denying he has any problems and describing himself as “the greatest doctor in the world.” The psychiatrist recommends hospitalization, but Dr. Z refuses and becomes belligerent. He announces that he just needs a career change and that he will fly to Mexico to open a bar.

This case, from the Texas Medical Association Archives,55 is not unusual. In addition to many characteristics discussed above, this case is typical in that the spouse brought the patient in, reflecting that the patient lacked insight that his behavior was abnormal. The disinhibition (hugging women), grandiosity, and unrealistic plans are also typical.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Anxiety disorders may be associated with dissociative speech or racing thoughts, which can be confused with bipolar illness. Personality disorders (eg, borderline, narcissistic, sociopathic) can involve a tumultuous and impulsive lifestyle resembling episodes of depression and mania. Schizoaffective illness has features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

It is also possible that, despite what may look like mild features of bipolar disorder, there is no psychiatric condition. Some people with mild mania—often successful professionals or politicians—have high energy and can function very well with only a few hours of sleep. Similarly, depressive symptoms for short periods of time can be adaptive, such as in the face of a serious setback when extreme reflection and a period of inactivity can be useful, leading to subsequent reorganization.

A psychiatric diagnosis is usually made only when there is an abnormality, ie, the behavior is beyond normal limits, the person cannot control his or her symptoms, or social or occupational functioning is impaired.

SCREENING INSTRUMENTS

A few tools help determine the likelihood of bipolar disorder.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)59,60 is a good 9-item screening tool for depression.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire60 is specific for bipolar disorder, and like the PHQ-9, it is a patient-reported, short questionnaire that is available free online. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire asks about the symptoms of mania in a yes-no format. The result is positive if all of the following are present:

- A “yes” response to 7 of the 13 features

- Several features occur simultaneously

- The features are a moderate or serious problem.

Unlike most screening instruments, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire is more specific than sensitive. It is 93% specific for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a primary care setting, but only 58% sensitive.61–63

WHEN TO REFER TO PSYCHIATRY

Patients suspected of having bipolar disorder or who have been previously diagnosed with it should be referred to a psychiatrist if they have certain features, including:

- Bipolar I disorder

- Psychotic symptoms

- Suicide risk or in danger of harming others

- Significantly impaired functioning

- Unclear diagnosis.

CASE 3: A TELEVISION ANCHOR’S DREAM TURNS TO NIGHTMARE

According to a famous news anchor’s autobiography,64 the steroids prescribed for her hives “revved her up.” The next course left her depressed. Antidepressant medications propelled her into a manic state, and she was soon planning a book, a television show, and a magazine all at once. During that time, she bought a cottage online. Her shyness evaporated at parties. “I was suddenly the equal of my high-energy friends who move fast and talk fast and loud,” she wrote. “I told everyone that I could understand why men felt like they could run the world, because I felt like that. This was a new me, and I liked her!”64 She was soon diagnosed with bipolar disorder and admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

TREAT WITH ANTIDEPRESSANTS, MOOD STABILIZERS

In general, acute bipolar disorder should be treated with a combination of an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer, and possibly an antipsychotic drug. An antidepressant should not be used alone, particularly with patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, because of the risk of triggering mania or the risk of faster cycling between mania and depression.13

Mood stabilizers include lithium, lamotrigine, and valproate. Each can prevent episodes of depression and mania. Lithium, which has been used as a mood stabilizer for 60 years, is specific for bipolar disorder, and it remains the best mood stabilizer treatment.

Antidepressants. The first-line antidepressant medication is bupropion, which is thought to be less likely to precipitate a manic episode,65 though all antidepressants have been associated with this side effect in patients with bipolar disorder. Other antidepressants—for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine and dual reuptake inhibitors such as venlafaxine and duloxetine—can also be used. The precipitation of mania and possible increased mood cycling was first described with tricylic antidepressants, so drugs of this class should be used with caution.

Neuroleptic drugs such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lurasidone may be the easiest drugs to use, as they have antidepressant effects and can also prevent the occurrence of mania. These medications are frequently classified as mood stabilizers. However, they may not have true mood stabilizing properties such as that of lithium. Importantly, their use tends to entail significant metabolic problems and can lead to hyperlipidemia and diabetes. In addition, Parkinson disease-like symptoms— and in some cases irreversible involuntary movements of the mouth and tongue, as well as the body (tardive dyskinesia)—are important possible side effects.

All psychiatric medications have potential side effects (Table 3). Newer antidepressants and neuroleptics may have fewer side effects than older medications but are not more effective.

Should milder forms of bipolar depression be treated?

A dilemma is whether we should treat milder forms of bipolar depression, such as bipolar II depression, depression with subthreshold hypomania symptoms, or depression in persons with a strong family history of bipolar disorder.

Many doctors are justifiably reluctant to prescribe antidepressants for depression because of the risk of triggering mania. Although mood stabilizers such as lithium would counteract possible mania emergence, physicians often do not prescribe them because of inexperience and fear of risks and possible side effects. Patients are likewise resistant because they feel that use of mood stabilizers is tantamount to being told they are “manic-depressive,” with its associated stigma.

Overuse of atypical neuroleptics such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and olanzapine has led to an awareness of metabolic syndrome and tardive dyskinesia, also making doctors cautious about using these drugs.

Answer: Yes, but treat with caution

Not treating depression consigns a patient to suffer with untreated depression, sometimes for years. Outcomes for patients with depression and bipolar disorder are often poor because the conditions are not recognized, and even when the conditions are recognized, doctors and patients may be reluctant to medicate appropriately. Medications should be used as needed to treat depression, but with an awareness of the possible side effects and with close patient monitoring.

A truly sustained manic state (unlike the brief euphoria brought on by some drugs) is not actually so easy to induce. In an unpublished Cleveland Clinic study, we monitored peaks of hypomanic symptoms in young patients (ages 15–30) during antidepressant treatment without mood stabilizers. About 30% to 40% of patients had subthreshold manic symptoms or a family history of bipolar disorder; 3 patients out of 51 developed hypomania leading to a change of diagnosis to bipolar disorder. Even in patients who had no risk factors for bipolar disorder, 2 out of 53 converted to a bipolar diagnosis. So conversion rates in patients with subthreshold bipolar disorder seem to be low, and the disorder can be identified early by monitoring the patient closely.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS FOR DEPRESSION

Psychotherapy is indicated for all patients on medications for depression, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments are more effective when combined.66 Other treatments include transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, and exercise. Having a consistent daily routine, particularly regarding the sleep-wake schedule, is also helpful, and patients should be educated about its importance.

Patients presenting with depression commonly have undiagnosed bipolar depression,1–7 that is, depression with shifts to periods of mania. During manic or hypomanic episodes, people feel energetic, need little sleep, and are often happy and charming.8 But too much of a good thing can also wreak havoc on their life.

Bipolar depression (ie, depression in patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder) is treated differently from unipolar depression,3,9–13 making it especially important that clinicians recognize if a patient who presents with depression has a history of (hypo)manic symptoms.

CASE 1: THE IMPULSIVE NURSE

A 32-year-old nurse presents to her primary care provider with depressed mood. She reports having had a single depressive episode when she was a college freshman. Her family history includes depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, and her paternal grandfather and a maternal aunt committed suicide. Upon questioning, she reveals that in the past, she has had 3 episodes lasting several weeks and characterized by insubordinate behavior at work, irritability, high energy, and decreased need for sleep. She regrets impulsive sexual and financial decisions that she made during these episodes and recently filed for personal bankruptcy. For the past month, her mood has been persistently low, with reduced sleep, appetite, energy, and concentration, and with passive thoughts of suicide.

A CAREFUL HISTORY IS CRITICAL

This case illustrates many typical features of bipolar depression that are revealed only by taking a thorough history. Although the patient is high-functioning, having attained a professional career, she has serious problems with sexual and financial impulsivity and at her job. She has a strong family history of mood disorder. And she describes episodes of depression and mania in the past.

Starts in young adulthood, strong heritability

Bipolar disorder can be a devastating condition with lifelong consequences,14–20 especially as it typically starts when patients are getting an education or embarking on a career. It usually first manifests in the late teenage years and progresses in the patient’s early 20s.21,22 The first hospitalization can occur soon thereafter.23,24

Bipolar disorder is one of the most heritable conditions in psychiatry, and about 13% of children who have an afflicted parent develop it.25 In identical twins, the concordance is about 50% to 75%, indicating the importance of genetics and environmental factors.26,27

Associated with migraine, other conditions

The disorder is associated with a variety of conditions (Table 1).28,29 Some conditions (eg, thyroid disease) can cause mood cycling, and some (eg, sexually transmitted infections, accidents) are the consequences of the lifestyle that may accompany mania. For unknown reasons, migraine is highly associated with bipolar disorder.

DEPRESSION AND MANIA: TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Symptoms of depression and mania are frequently viewed as opposite mood states, though many times patients report a mixture of them.17,30–35 For both states, the features of a distinct change from the patient’s normal condition and the sustained nature of the symptoms are important diagnostically and indicate a likely underlying biological cause.

Major depressive disorder: Slowing down

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),8 defines major depressive disorder as having either depressed mood or markedly diminished pleasure in most activities for most days during at least 2 weeks.

In addition, at least 4 of the following must be present during the same period:

- Appetite disturbance

- Sleep disturbance

- Motor retardation or agitation

- Lack of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt

- Decreased concentration

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

An estimated 20% of the population experience a major depressive episode over their lifetime. A surprisingly high proportion of people with depression—30% to 40%—also have had subthreshold symptoms of mania (symptoms not meeting the criteria for hypomania or mania in terms of number of symptoms or duration).21,22 Because of these odds, it is important to suspect bipolar disorder even in patients who present with depression but who may not yet have manifested episodes of mania or hypomania.

Mood disorders can be regarded as falling into a spectrum, ranging from unipolar or “pure” major depression without any features of hypomania to major depression and severe mania.17,31–36

Mania: Speeding up

The DSM-5 defines mania as the presence of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood with increased activity for more than 1 week. In addition, at least 3 of the following features must be present, with impaired functioning (4 features are required if mood is only irritable)8:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- Pressured speech

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Excessive involvement in pleasurable, high-risk activities.

Hypomania: No functional impairment

Hypomania is a less severe condition, in which the abnormally elevated mood is of shorter duration (4–7 days) and meets the other criteria for mania but without significant functional impairment. People may, in fact, be very functional and productive during hypomanic episodes.8

CLASSIFYING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Bipolar disorder is categorized according to severity.24,37,38 The most severe form, bipolar I disorder, is marked by major depression and manic episodes. It affects up to 1.5% of the US population, with equal proportions of men and women.39 Bipolar II disorder is less severe. It affects 0.8% to 1.6% of the US population, predominantly women.21,40 In bipolar II disorder, depression is more prominent, with episodes of hypomania.

Subthreshold bipolar disorders are characterized by episodic symptoms that do not meet the threshold for depression or hypomania; the symptoms are fewer or of shorter duration. These minor types of bipolar disorder affect up to 6% of the US population.17

Other conditions within the spectrum of bipolar and depressive disorders include medication- and substance-induced mania, agitated or anxious depression, and mixed states.31,34–36

DISTINGUISHING UNIPOLAR FROM BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Considerable research has focused on finding a clear-cut clinical or biological feature to differentiate unipolar from bipolar depression, but so far none has been discovered. Distinguishing the two conditions still depends on clinical judgment. There are important reasons to identify the distinction between unipolar depression and bipolar disorder.

Prognosis differs. Bipolar disorder tends to be a more severe condition. Young people, who may initially present with only mild symptoms of mania, may develop serious episodes over the years. People may lose their savings, their marriage, and their career during a manic episode. The more critical the occupation (eg, doctor, pilot), the greater the potential consequences of impaired judgment brought on by even mild hypomania.14–20

Treatment differs. Typical antidepressants given for depression can trigger a manic episode in patients with bipolar depression, with devastating consequences. Atypical neuroleptic drugs used to treat bipolar disorder can also have serious effects (eg, metabolic and neurologic effects, including irreversible tardive dyskinesia).3,13,40–43

Despite the good reasons to do so, many doctors (including some psychiatrists) do not ask their patients about a propensity to mania or hypomania.4–6 More stigma is attached to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder than to depression44–47; once it is in the medical record, the patient may have problems with employment and obtaining medical insurance.17,44 The old term “manic-depressive” is often associated in the public mind with a person on the streets displaying severely psychotic behavior; the condition is now understood to consist of a spectrum from mild to more severe illness.

Clinical indicators of bipolarity

There are many indicators that a person who presents with depression may be on the bipolar spectrum, but this is not always easily identified.48–53

History of hypomanic symptoms or subthreshold manic symptoms. Although directly asking the patient about the defining symptoms (eg, “Have you ever had episodes of being ‘hyper’ or too happy?”) may help elicit the diagnosis, many patients with bipolar disorder only report depression, as it is psychically painful. In contrast, hypomania and even mania can be perceived as positive, as patients may have less insight into the abnormality of the condition and feel that they are functioning extremely well.

Early age of onset of a mood disorder, such as severe depression in childhood or early adulthood, points toward bipolar disorder. Diagnosing mood disorders in childhood is difficult, as children are less able to recognize or verbalize many of their symptoms.

Postpartum mood disorder, particularly with psychotic symptoms, indicates a strong possibility of a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Drug-induced mania, hypomania, and periods of hyperactivity are key features of bipolar disorder. If asked, patients may report feeling a “buzz” when taking an antidepressant.

Erratic patterns in work and relationships are a red flag and are viewed as “soft signs” of bipolar depression. Akiskal54 described the “rule of three” that should make one consider bipolar disorder: for example, three failed marriages, three current jobs or frequent job changes, three distinct professions practiced at the same time, and simultaneously dating three people. Such features indicate both the hyperfunctioning and the disruptive aspects of mania.

Family history of bipolar disorder or severe psychiatric illness is a very important clue. A more subtle clue described by Akiskal54 may be that several members of the family are very high-functioning in several different fields: eg, one may be a highly accomplished doctor, another a famous lawyer, and another a prominent politician. Or several members of the family may have erratic patterns of work and relationships. However, these subtle clues have been derived from clinical experiences and have not been validated in large-scale studies.

CASE 2: THE FRIENDLY SURGEON

Dr. Z is a prominent surgical subspecialist who is part of a small group practice. His wife has become increasingly worried about his behavior changes at home, including sleeping only a few hours a night, spending sprees, and binge drinking. He reluctantly agrees to an outpatient psychiatric evaluation if she attends with him. He creates a disturbance in the waiting room by shaking everyone’s hands and trying to hug all the women. During his examination, he is loud and expansive, denying he has any problems and describing himself as “the greatest doctor in the world.” The psychiatrist recommends hospitalization, but Dr. Z refuses and becomes belligerent. He announces that he just needs a career change and that he will fly to Mexico to open a bar.

This case, from the Texas Medical Association Archives,55 is not unusual. In addition to many characteristics discussed above, this case is typical in that the spouse brought the patient in, reflecting that the patient lacked insight that his behavior was abnormal. The disinhibition (hugging women), grandiosity, and unrealistic plans are also typical.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Anxiety disorders may be associated with dissociative speech or racing thoughts, which can be confused with bipolar illness. Personality disorders (eg, borderline, narcissistic, sociopathic) can involve a tumultuous and impulsive lifestyle resembling episodes of depression and mania. Schizoaffective illness has features of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

It is also possible that, despite what may look like mild features of bipolar disorder, there is no psychiatric condition. Some people with mild mania—often successful professionals or politicians—have high energy and can function very well with only a few hours of sleep. Similarly, depressive symptoms for short periods of time can be adaptive, such as in the face of a serious setback when extreme reflection and a period of inactivity can be useful, leading to subsequent reorganization.

A psychiatric diagnosis is usually made only when there is an abnormality, ie, the behavior is beyond normal limits, the person cannot control his or her symptoms, or social or occupational functioning is impaired.

SCREENING INSTRUMENTS

A few tools help determine the likelihood of bipolar disorder.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)59,60 is a good 9-item screening tool for depression.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire60 is specific for bipolar disorder, and like the PHQ-9, it is a patient-reported, short questionnaire that is available free online. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire asks about the symptoms of mania in a yes-no format. The result is positive if all of the following are present:

- A “yes” response to 7 of the 13 features

- Several features occur simultaneously

- The features are a moderate or serious problem.

Unlike most screening instruments, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire is more specific than sensitive. It is 93% specific for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a primary care setting, but only 58% sensitive.61–63

WHEN TO REFER TO PSYCHIATRY

Patients suspected of having bipolar disorder or who have been previously diagnosed with it should be referred to a psychiatrist if they have certain features, including:

- Bipolar I disorder

- Psychotic symptoms

- Suicide risk or in danger of harming others

- Significantly impaired functioning

- Unclear diagnosis.

CASE 3: A TELEVISION ANCHOR’S DREAM TURNS TO NIGHTMARE

According to a famous news anchor’s autobiography,64 the steroids prescribed for her hives “revved her up.” The next course left her depressed. Antidepressant medications propelled her into a manic state, and she was soon planning a book, a television show, and a magazine all at once. During that time, she bought a cottage online. Her shyness evaporated at parties. “I was suddenly the equal of my high-energy friends who move fast and talk fast and loud,” she wrote. “I told everyone that I could understand why men felt like they could run the world, because I felt like that. This was a new me, and I liked her!”64 She was soon diagnosed with bipolar disorder and admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

TREAT WITH ANTIDEPRESSANTS, MOOD STABILIZERS

In general, acute bipolar disorder should be treated with a combination of an antidepressant and a mood stabilizer, and possibly an antipsychotic drug. An antidepressant should not be used alone, particularly with patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, because of the risk of triggering mania or the risk of faster cycling between mania and depression.13

Mood stabilizers include lithium, lamotrigine, and valproate. Each can prevent episodes of depression and mania. Lithium, which has been used as a mood stabilizer for 60 years, is specific for bipolar disorder, and it remains the best mood stabilizer treatment.

Antidepressants. The first-line antidepressant medication is bupropion, which is thought to be less likely to precipitate a manic episode,65 though all antidepressants have been associated with this side effect in patients with bipolar disorder. Other antidepressants—for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine and dual reuptake inhibitors such as venlafaxine and duloxetine—can also be used. The precipitation of mania and possible increased mood cycling was first described with tricylic antidepressants, so drugs of this class should be used with caution.

Neuroleptic drugs such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lurasidone may be the easiest drugs to use, as they have antidepressant effects and can also prevent the occurrence of mania. These medications are frequently classified as mood stabilizers. However, they may not have true mood stabilizing properties such as that of lithium. Importantly, their use tends to entail significant metabolic problems and can lead to hyperlipidemia and diabetes. In addition, Parkinson disease-like symptoms— and in some cases irreversible involuntary movements of the mouth and tongue, as well as the body (tardive dyskinesia)—are important possible side effects.

All psychiatric medications have potential side effects (Table 3). Newer antidepressants and neuroleptics may have fewer side effects than older medications but are not more effective.

Should milder forms of bipolar depression be treated?

A dilemma is whether we should treat milder forms of bipolar depression, such as bipolar II depression, depression with subthreshold hypomania symptoms, or depression in persons with a strong family history of bipolar disorder.

Many doctors are justifiably reluctant to prescribe antidepressants for depression because of the risk of triggering mania. Although mood stabilizers such as lithium would counteract possible mania emergence, physicians often do not prescribe them because of inexperience and fear of risks and possible side effects. Patients are likewise resistant because they feel that use of mood stabilizers is tantamount to being told they are “manic-depressive,” with its associated stigma.

Overuse of atypical neuroleptics such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, and olanzapine has led to an awareness of metabolic syndrome and tardive dyskinesia, also making doctors cautious about using these drugs.

Answer: Yes, but treat with caution

Not treating depression consigns a patient to suffer with untreated depression, sometimes for years. Outcomes for patients with depression and bipolar disorder are often poor because the conditions are not recognized, and even when the conditions are recognized, doctors and patients may be reluctant to medicate appropriately. Medications should be used as needed to treat depression, but with an awareness of the possible side effects and with close patient monitoring.

A truly sustained manic state (unlike the brief euphoria brought on by some drugs) is not actually so easy to induce. In an unpublished Cleveland Clinic study, we monitored peaks of hypomanic symptoms in young patients (ages 15–30) during antidepressant treatment without mood stabilizers. About 30% to 40% of patients had subthreshold manic symptoms or a family history of bipolar disorder; 3 patients out of 51 developed hypomania leading to a change of diagnosis to bipolar disorder. Even in patients who had no risk factors for bipolar disorder, 2 out of 53 converted to a bipolar diagnosis. So conversion rates in patients with subthreshold bipolar disorder seem to be low, and the disorder can be identified early by monitoring the patient closely.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS FOR DEPRESSION

Psychotherapy is indicated for all patients on medications for depression, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments are more effective when combined.66 Other treatments include transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, and exercise. Having a consistent daily routine, particularly regarding the sleep-wake schedule, is also helpful, and patients should be educated about its importance.

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. Am Psychol 1998; 53(2):221–241. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.221

- Glick ID. Undiagnosed bipolar disorder: new syndromes and new treatments. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004;6(1):27–33. pmid:15486598

- Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(10):804–808. pmid:11078046

- Singh T, Rajput M. Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006; 3(10):57–63. pmid: 20877548

- Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31(4):281–294. pmid:7989643

- Howes OD, Falkenberg I. Early detection and intervention in bipolar affective disorder: targeting the development of the disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2011; 13(6):493–499. pmid:21850462

- Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, Pandurangi AK, Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999; 52(1–3):135–144. pmid:10357026

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

- Hlastala SA, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Ritenour AM, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar depression: an underestimated treatment challenge. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5(2):73–83. pmid:9262937

- Smith DJ, Craddock N. Unipolar and bipolar depression: different or the same? Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199(4):272–274. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092726

- Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171(10):1067–1073. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111501

- Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007; 356(17):1711–1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064135

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(4 suppl):1–50. pmid:11958165

- Leonpacher AK, Liebers D, Pirooznia M, et al. Distinguishing bipolar from unipolar depression: the importance of clinical symptoms and illness features. Psychol Med 2015; 45(11):2437–2446. doi:10.1017/S0033291715000446

- Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1–2):133–146. pmid:12507746

- Faravelli C, Rosi S, Alessandra Scarpato M, Lampronti L, Amedei SG, Rana N. Threshold and subthreshold bipolar disorders in the Sesto Fiorentino Study. J Affect Disord 2006; 94(1–3):111–119. pmid:16701902

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord 2003; 73(1–2):123–131. pmid:12507745

- Park Y-M, Lee B-H. Treatment response in relation to subthreshold bipolarity in patients with major depressive disorder receiving antidepressant monotherapy: a post hoc data analysis (KOMDD study). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016; 12:1221–1227. doi:10.2147/NDT.S104188

- Perlis RH, Uher R, Ostacher M, Goldberg JF, et al. Association between bipolar spectrum features and treatment outcomes in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(4):351–360. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.179

- Dudek D, Siwek M, Zielin´ska D, Jaeschke R, Rybakowski J. Diagnostic conversions from major depressive disorder into bipolar disorder in an outpatient setting: results of a retrospective chart review. J Affect Disord 2013; 144(1–2):112–115. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.014

- Angst J, Cui L, Swendsen J, et al. Major depressive disorder with subthreshold bipolarity in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167(10):1194–1201. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09071011

- Zimmermann P, Brückl T, Nocon A, et al. Heterogeneity of DSM-IV major depressive disorder as a consequence of subthreshold bipolarity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66(12):1341–1352. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.158

- Patel NC, DelBello MP, Keck PE, Strakowski SM. Phenomenology associated with age at onset in patients with bipolar disorder at their first psychiatric hospitalization. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8(1):91–94. pmid:16411986

- Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(2):161–174. pmid:12633125

- Craddock N, Jones I. Genetics of bipolar disorder. J Med Genet 1999; 36(8):585–594. pmid:10465107

- Griswold KS, Pessar LF. Management of bipolar disorder. Am Fam Physician 2000; 62(6):1343–1358. pmid:11011863

- Kerner B. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Appl Clin Genet 2014; 7:33–42. doi:10.2147/TACG.S39297

- Scheffer RE, Linden S. Concurrent medical conditions with pediatric bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007; 20(4):398–401. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281a305c3

- Carney CP, Jones LE. Medical comorbidity in women and men with bipolar disorders: a population-based controlled study. Psychosom Med 2006;68(5):684–691. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000237316.09601.88

- Cassano GB, Akiskal HS, Savino M, Musetti L, Perugi G. Proposed subtypes of bipolar II and related disorders: with hypomanic episodes (or cyclothymia) and with hyperthymic temperament. J Affect Disord 1992; 26(2):127–140. pmid:1447430

- Akiskal HS, Mallya G. Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23(1):68–73. pmid:3602332

- Fiedorowicz JG, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Keller MB, Coryell WH. Subthreshold hypomanic symptoms in progression from unipolar major depression to bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168(1):40–48. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030328

- Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Bartoli L. Agitated “unipolar” major depression: prevalence, phenomenology, and outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67(5):712–719. pmid:16841620

- Akiskal HS. The bipolar spectrum: new concepts in classification and diagnosis. In: Psychiatry Update: the American Psychiatric Association Annual Review. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1983:271–292.

- Akiskal HS, Pinto O. The evolving bipolar spectrum. Prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22(3):517–534. pmid:10550853

- Cassano GB, Savino M, Perugi G, Musetti L, Akiskal HS. Major depressive episode: unipolar and bipolar II. Encephale 1992 Jan;18 Spec No:15–18. pmid:1600898

- Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Berghöfer A, Bauer M. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2002; 359(9302):241–247. pmid:11812578

- Hirschfeld RMA, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(1):53–59. pmid:12590624