User login

Membership priorities shape the AGA advocacy agenda

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

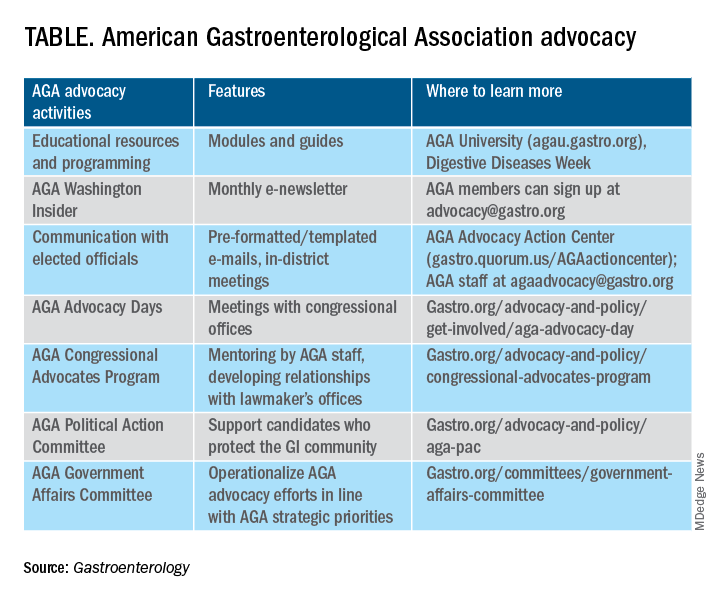

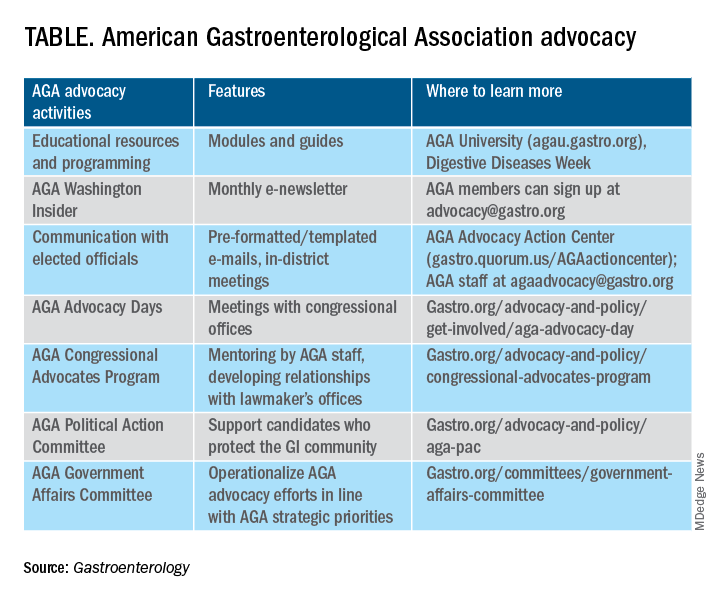

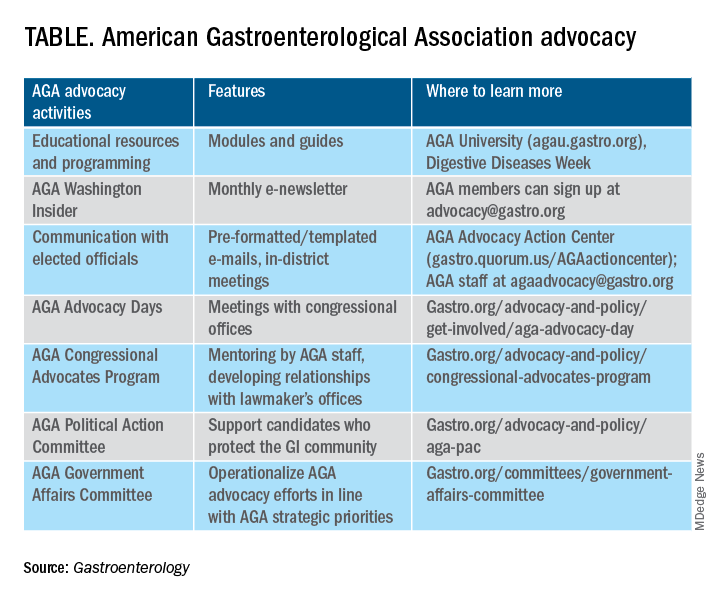

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) , both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor-HHS Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

• Removing Barriers to the Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies – regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

• Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life-threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

• Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

• NIH research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured, L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina Senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R) on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy due to delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-OH, has circulated asking CMS to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Cary, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) , both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor-HHS Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

• Removing Barriers to the Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies – regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

• Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life-threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

• Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

• NIH research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured, L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina Senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R) on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy due to delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-OH, has circulated asking CMS to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Cary, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) , both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor-HHS Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

• Removing Barriers to the Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies – regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

• Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life-threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

• Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

• NIH research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured, L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina Senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R) on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy due to delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-OH, has circulated asking CMS to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Cary, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

AGA News

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

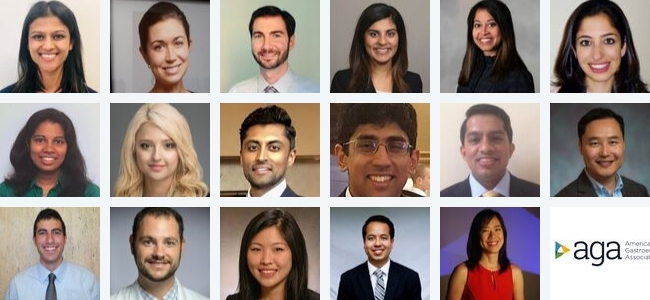

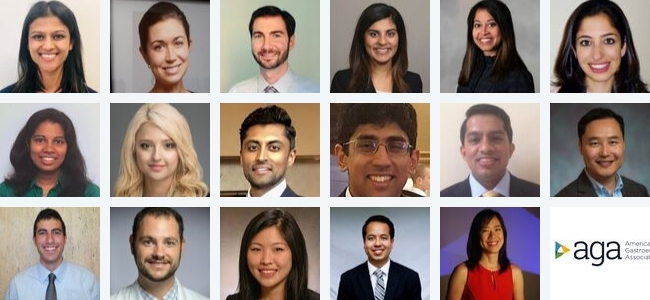

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York

@AdamFaye4

Shelly Gurwara, MD

Wake Forest Baptist Health Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Afrin Kamal, MD

Stanford (Calif.) University

Ani Kardashian, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

@AniKardashianMD

Sonali Palchaudhuri, MD

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

@sopalchaudhuri

Nasim Parsa, MD

University of Missouri Health System, Columbia

Sahil Patel, MD

Drexel University, Philadelphia

@sahilr

Vikram Raghu, MD

Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Amit Shah, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lin Shen, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

@LinShenMD

Charles Snyder, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Brian Sullivan, MD

Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Ashley Vachon, MD

University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora

Ted Walker, MD

Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

Xiao Jing Wang, MD

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

@IrisWangMD

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York

@AdamFaye4

Shelly Gurwara, MD

Wake Forest Baptist Health Medical Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Afrin Kamal, MD

Stanford (Calif.) University

Ani Kardashian, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

@AniKardashianMD

Sonali Palchaudhuri, MD

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

@sopalchaudhuri

Nasim Parsa, MD

University of Missouri Health System, Columbia

Sahil Patel, MD

Drexel University, Philadelphia

@sahilr

Vikram Raghu, MD

Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Amit Shah, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Lin Shen, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

@LinShenMD

Charles Snyder, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York

Brian Sullivan, MD

Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Ashley Vachon, MD

University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora

Ted Walker, MD

Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

Xiao Jing Wang, MD

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

@IrisWangMD

Ten tips to help you get a research grant

It’s almost time to submit your application for the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award, the application deadline is Nov. 13, 2019. Review these tips for writing and preparing your application.

1. Start early. Allow plenty of time to complete your application, give it multiple reviews, and get feedback from others. Most applicants start working on the Specific Aims for the project 6 months in advance of the deadline.

2. Look at examples. Ask your division if there are any templates/prior grant submissions that you can review. There’s no recipe for a successful grant, so the only way to compose one is to have a sense of what has worked in the past. In general, prior awardees are happy to share their applications if you contact them.

3. Request feedback. Ask mentors and colleagues for early feedback on your Specific Aims page. If it makes sense and is interesting to them, reviewers will likely feel the same way.

4. Ask your collaborators for letters of support. In addition to your preceptor, consider including letters of support from prior researchers that you have worked with or any collaborators for the current project, especially if they will help you with a new technique or reagents.

5. Contact the grants staff with questions and concerns early on. If you don’t understand part of the application, aren’t sure if you’re eligible or are having problems with submission, contact the grant staff right away. Don’t wait until the week or day the grant is due when staff may be flooded with calls. They can assist you much better with advance notice, which will allow you to avoid last-minute stress.

6. Each application should be different. Keep in mind the scope of the grant and amount of funding. Don’t just recycle an R01-level application for a 1-year AGA pilot award.

7. More is better than less when it comes to preliminary data. If your expertise in a technique you are proposing is established, you will not need to demonstrate the capability to do the work but will likely need to show preliminary data. If you are looking to build expertise (as a part of your career development), you may need to show that the infrastructure that enables you to do the work is accessible.

8. Don’t take constructive feedback personally. As you share your draft with mentors and colleagues for feedback, you may receive some unanticipated criticism. Try not to take this personally. If you can detach yourself emotionally, you’ll be in a better position to answer critiques and make adjustments.

9. Remember your end goal: To help patients! Even the most basic science proposals are rooted in a clear potential to benefit patients.

10. Stay positive. If you do not succeed on your first application, believe in your work, make it better, and apply again.

Thanks to the following AGA Research Foundation grant recipients for sharing their advice, which resulted in the above 10 tips:

- Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, 2016 AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award

- Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, 2014 AGA Research Scholar Award

- Josephine Ni, MD, 2017 AGA-Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Sahar Nissim, MD, PhD, 2017 AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer

- Jatin Roper, MD, 2011 AGA Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Award

- Christina Twyman-Saint Victor, MD, 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award

Visit www.gastro.org/research-funding to review the AGA Research Foundation research grants now open for applications. If you have questions about the AGA awards program, please contact [email protected].

The importance of getting involved for gastroenterology

On Sept. 20, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in AGA’s Advocacy Day for the second time, joining 40 of our gastroenterology colleagues from across the United States on Capitol Hill to advocate for our profession and our patients.

The evening before Advocacy Day, we discussed strategies for having a successful meeting on Capitol Hill with AGA staff (including Kathleen Teixeira, AGA vice president of government affairs, and Jonathan Sollish, AGA senior coordinator, public policy). We discussed having our “asks” supported with evidence, and “getting personal” about how these policy issues directly affect us and our patients. We also had the chance to hear from Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), both of whom invited our questions. Both congressmen are friends of AGA, with Rep. McGovern serving as chair of the House Rules Committee, and Sen. Blunt serving as chair of the Senate Labor–Health & Human Services Subcommittee on Appropriations.

Advocacy Day began with a group breakfast during which we reviewed some of the policy issues of central importance to gastroenterology:

- Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act (HR1570/S668), which enjoys strong bipartisan support, would correct the “cost-sharing” problem of screening colonoscopies turning therapeutic (with polypectomy) for our Medicare patients, by waiving the coinsurance for screening colonoscopies — regardless of whether we remove polyps during these colonoscopies.

- Safe Step Act, HR2279, legislation introduced in the House, facilitates a common-sense and timely (72 hours or 24 hours if life threatening) appeals process when our patients are subjected to step therapy (“fail first”) by insurers.

- Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2019, HR3107, legislation in the House, eases onerous prior authorization burdens by promoting an electronic prior authorization process, ensuring requests are approved by qualified medical professionals who have specialty-specific experience, and mandating that plans report their rates of delays and denials.

- National Institutes of Health research funding facilitates innovative research and supports young investigators in our field.

Full of enthusiasm, our six-strong North Carolina contingent (pictured L-R, Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF; David Leiman, MD, MSPH; Animesh Jain, MD; Anne Finefrock Peery, MD; Lisa Gangarosa, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Government Affairs Committee; and Amit Patel, MD) met with the offices of Rep. David Price (D-N.C.), and both North Carolina senators, Richard Burr (R) and Thom Tillis (R), on Capitol Hill to convey our “asks.”

At Rep. Price’s office in the stately Rayburn House Office Building, we thanked his team for cosponsorship of H.R. 1570 and H.R. 2279. We also discussed the importance of increasing research funding by the AGA’s goal of $2.5 billion for NIH for fiscal year 2020, noting that a majority of our delegation has received NIH funding for our training and/or research activities. We also encouraged Price’s office to cosponsor H.R. 3107, sharing our personal experiences about the administrative toll of the prior authorization process for obtaining appropriate and recommended medications for our patients – in my case, swallowed topical corticosteroids for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

We moved on to Sen. Tillis’s office, where we thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged his office to cosponsor upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107. Our colleague capably conveyed how an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient he saw recently may require a colectomy because of delays in appropriate treatment stemming from these regulatory processes. We also showed Tillis’s office how NIH funding generates significant economic activity in North Carolina, supporting jobs in our state.

After a quick stop at the U.S. Senate gift shop in the basement to buy souvenirs for our kids, our last meeting was with Sen. Burr’s office. There, we also thanked his office for cosponsorship of S. 668 but encouraged him to sign the “Dear Colleague” letter that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) has circulated asking the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to address the colonoscopy cost-sharing “loophole.” We discussed the importance of cosponsoring upcoming companion Senate legislation for H.R. 2279 and H.R. 3107, sharing stories from our clinical practices about how these regulatory burdens have delayed treatment for our patients.

You can get involved, too.

AGA Advocacy Day was a tremendous experience, but it is not the only way AGA members can get involved and take action. The AGA Advocacy website, gastro.org/advocacy, provides more information on multiple avenues for advocacy. These include an online advocacy tool for sending templated letters on these issues to your elected officials.

Perhaps now more than ever, it is crucial that we get involved to support gastroenterology and advocate for our patients.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor, division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; member, AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee.

GI of the week: Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD

Congrats to Arthur Beyder, MD, PhD, who was selected for an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, part of the NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research award program. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Award will provide Dr. Beyder with more than $2 million in funding over a 5-year period to continue his project: Does the gut have a sense of touch?

Dr. Beyder’s lab at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., recently discovered a novel population of mechanosensitive epithelial sensory cells that are similar to skin’s touch sensors, which prompted a potentially transformative question: “Does the gut have a sense of touch?” We look forward to seeing the results of future research on this topic.

Dr. Beyder – a physician-scientist at the Mayo Clinic – is a 2015 AGA Research Scholar Award recipient and graduate of the 2018 AGA Future Leaders Program. Dr. Beyder currently serves on the AGA Nominating Committee.

Please join us in congratulating Dr. Beyder on Twitter (@BeyderLab) or in the AGA Community.

The NIH director’s high-risk, high-reward research program funds highly innovative, high-impact biomedical research proposed by extraordinarily creative scientists – these awards have one of the lowest funding rates for NIH. Congrats to two additional AGA members who also received a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award: Maayan Levy, PhD, and Christoph A. Thaiss, PhD, both from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Eight new insights about diet and gut health

During your 4 years of medical school, you likely received only 4 hours of nutrition training. Yet we know diet is so integral to the care of GI patients. That’s why AGA focused the 2019 James W. Freston Conference on the topic: Food at the Intersection of Gut Health and Disease.

Our course directors William Chey, MD, AGAF, Sheila E. Crowe, MD, AGAF, and Gerard E. Mullin, MD, AGAF, share eight points from the meeting that stuck with them and can help all practicing GIs as they consider dietary treatments for their patients.

1. Personalized nutrition is important. Genetic differences lead to differences in health outcomes. One size or recommendation does not fit all. This is why certain diets only work on certain people. There is no one diet for all and for all disease states. Genetic tests can be helpful, but they rely on reporting that isn’t readily available yet.

2. Dietary therapy is key to managing eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). EoE is becoming more and more prevalent. Genes can’t change that fast, but epigenetic factors can, and the evidence seems to be in food. EoE is not an IgE-mediated disease and therefore most allergy tests will not prove useful; however, food is often the trigger – most common, dairy. Dietary therapy is likely the best way to manage. You want to reduce the number of eliminated foods by way of a reintroduction protocol. The six-food elimination diet is standard, though some are moving to a four-food elimination diet (dairy, wheat, egg, and soy).

3. There has been a reported increase in those with food allergies, sensitivities, celiac disease, and other adverse reactions to food. Many of the food allergy tests available are not helpful. In addition, many afflicted patients are using self-imposed diets rather than working with a GI, allergist, or dietitian. This needs to change.

4. There is currently insufficient evidence to support a gluten-free diet for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is possible that fructans, more than gluten, are causing the GI issues. Typically, the low-FODMAP diet is beneficial to IBS patients if done correctly with the guidance of a dietitian; however, not everyone with IBS improves on it. All the steps are important though, including reintroduction and maintenance.

5. When working with patients on the low-FODMAP or other restrictive diets, it is important to know their food and eating history. Avoidance/restrictive food intake disorder is something we need to be aware of when it comes to patients with a history or likelihood to develop disordered eating/eating disorders. The patient team may need to include an eating disorder therapist.

6. The general population in the United States has increased the adoption of a gluten-free diet although the number of cases of celiac disease has not increased. Many have self-reported gluten sensitivities. Those that have removed gluten, following trends, are more at risk of bowel irregularity (low fiber), weight gain, and disordered eating. Celiac disease is not a do-it-yourself disease, patients will be best served working with a dietitian and GI.

7. Food can induce symptoms in patients with IBD. It can also trigger gut inflammation resulting in incident or relapse. There is experimental plausibility for some factors of the relationship to be causal and we may be able to modify the diet to prevent and manage IBD.

8. The focus on nutrition education must continue! Nutrition should be a required part of continuing medical education for physicians. And physicians should work with dietitians to improve the care of GI patients.

17 fellows advancing GI and patient care

Each year during Digestive Disease Week®, AGA hosts a session titled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality-Improvement Projects.” During the 2019 session, 17 quality improvement initiatives were presented — you can review these abstracts in the July issue of Gastroenterology in the “AGA Section” or review a presenter’s abstract by clicking their name or image. Kudos to the promising fellows featured below, who all served as lead authors for their quality improvement projects.

Manasi Agrawal, MD

Lenox Hill Hospital, New York

@ManasiAgrawalMD

Jessica Breton, MD

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Adam Faye, MD