User login

More Than 100 GIs Strong for Advocacy Day 2025!

For our leaders, showing up on behalf of their patients is a privilege and an opportunity to represent the specialty with individuals who have a role in dictating health care policy.

In total, 124 members, patient advocates, and AGA staffers met with lawmakers and attended 130 meetings – 70 unique House districts and 60 unique Senate districts – with Republican and Democratic staff.

Our advocacy contingent represented the diversity of the country with 30 states represented from coast-to-coast. No matter the home state, everyone was united in the calls to Congress: to reform prior authorization, increase digestive disease funding, and secure a permanent solution for Medicare physician reimbursement.

As in past years, patient advocates participated alongside GI clinicians and researchers.

Their participation underscored the importance of including diverse voices. As patients with chronic health conditions, they were able to convey how their experiences navigating insurance barriers or managing delays to care as prescribed by their health care provider impacted their well-being and quality of life.

Throughout the day, patient advocates and GIs alike were encouraged by their meetings with congressional staffers. Conversations were constructive, engaging, and meaningful as everyone collaborated on common ground: seeking solutions to ensure GI patients have timely access to care that they need.

Many AGA leaders appreciated the value of being able to unite with colleagues to advocate and share their firsthand experiences in the lab or clinic in meetings with House and Senate staffers.

While Advocacy Day lasts a single day, its value hasn’t diminished. Thanks to the engagement and participation of the more than 100 AGA leaders and patient advocates, we can continue to build positive relationships with influential policymakers and make strides to improve and protect access to GI patient care.

For our leaders, showing up on behalf of their patients is a privilege and an opportunity to represent the specialty with individuals who have a role in dictating health care policy.

In total, 124 members, patient advocates, and AGA staffers met with lawmakers and attended 130 meetings – 70 unique House districts and 60 unique Senate districts – with Republican and Democratic staff.

Our advocacy contingent represented the diversity of the country with 30 states represented from coast-to-coast. No matter the home state, everyone was united in the calls to Congress: to reform prior authorization, increase digestive disease funding, and secure a permanent solution for Medicare physician reimbursement.

As in past years, patient advocates participated alongside GI clinicians and researchers.

Their participation underscored the importance of including diverse voices. As patients with chronic health conditions, they were able to convey how their experiences navigating insurance barriers or managing delays to care as prescribed by their health care provider impacted their well-being and quality of life.

Throughout the day, patient advocates and GIs alike were encouraged by their meetings with congressional staffers. Conversations were constructive, engaging, and meaningful as everyone collaborated on common ground: seeking solutions to ensure GI patients have timely access to care that they need.

Many AGA leaders appreciated the value of being able to unite with colleagues to advocate and share their firsthand experiences in the lab or clinic in meetings with House and Senate staffers.

While Advocacy Day lasts a single day, its value hasn’t diminished. Thanks to the engagement and participation of the more than 100 AGA leaders and patient advocates, we can continue to build positive relationships with influential policymakers and make strides to improve and protect access to GI patient care.

For our leaders, showing up on behalf of their patients is a privilege and an opportunity to represent the specialty with individuals who have a role in dictating health care policy.

In total, 124 members, patient advocates, and AGA staffers met with lawmakers and attended 130 meetings – 70 unique House districts and 60 unique Senate districts – with Republican and Democratic staff.

Our advocacy contingent represented the diversity of the country with 30 states represented from coast-to-coast. No matter the home state, everyone was united in the calls to Congress: to reform prior authorization, increase digestive disease funding, and secure a permanent solution for Medicare physician reimbursement.

As in past years, patient advocates participated alongside GI clinicians and researchers.

Their participation underscored the importance of including diverse voices. As patients with chronic health conditions, they were able to convey how their experiences navigating insurance barriers or managing delays to care as prescribed by their health care provider impacted their well-being and quality of life.

Throughout the day, patient advocates and GIs alike were encouraged by their meetings with congressional staffers. Conversations were constructive, engaging, and meaningful as everyone collaborated on common ground: seeking solutions to ensure GI patients have timely access to care that they need.

Many AGA leaders appreciated the value of being able to unite with colleagues to advocate and share their firsthand experiences in the lab or clinic in meetings with House and Senate staffers.

While Advocacy Day lasts a single day, its value hasn’t diminished. Thanks to the engagement and participation of the more than 100 AGA leaders and patient advocates, we can continue to build positive relationships with influential policymakers and make strides to improve and protect access to GI patient care.

Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month is Here!

Happy Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Awareness Month! Today, CRC is the third-most common cancer in men and women in the United States. But there’s good news: We know that screening saves lives. That’s why

We have a variety of resources for both physicians and patients to navigate the CRC screening process.

Clinical Guidance

AGA’s clinical guidelines and clinical practice updates provide evidence-based recommendations to guide your clinical practice decisions. Visit AGA’s new toolkit on CRC for the latest guidance on topics including colonoscopy follow-up, liquid biopsy, appropriate and tailored polypectomy, and more.

Patient Resources

AGA’s GI Patient Center can help your patients understand the need for CRC screening, colorectal cancer symptoms and risks, available screening tests, and the importance of preparing for a colonoscopy. Visit patient.gastro.org to access patient education materials.

Join the Conversation

We’ll be sharing resources and encouraging screenings on social media all month long. Join us as we remind everyone that 45 is the new 50.

Happy Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Awareness Month! Today, CRC is the third-most common cancer in men and women in the United States. But there’s good news: We know that screening saves lives. That’s why

We have a variety of resources for both physicians and patients to navigate the CRC screening process.

Clinical Guidance

AGA’s clinical guidelines and clinical practice updates provide evidence-based recommendations to guide your clinical practice decisions. Visit AGA’s new toolkit on CRC for the latest guidance on topics including colonoscopy follow-up, liquid biopsy, appropriate and tailored polypectomy, and more.

Patient Resources

AGA’s GI Patient Center can help your patients understand the need for CRC screening, colorectal cancer symptoms and risks, available screening tests, and the importance of preparing for a colonoscopy. Visit patient.gastro.org to access patient education materials.

Join the Conversation

We’ll be sharing resources and encouraging screenings on social media all month long. Join us as we remind everyone that 45 is the new 50.

Happy Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Awareness Month! Today, CRC is the third-most common cancer in men and women in the United States. But there’s good news: We know that screening saves lives. That’s why

We have a variety of resources for both physicians and patients to navigate the CRC screening process.

Clinical Guidance

AGA’s clinical guidelines and clinical practice updates provide evidence-based recommendations to guide your clinical practice decisions. Visit AGA’s new toolkit on CRC for the latest guidance on topics including colonoscopy follow-up, liquid biopsy, appropriate and tailored polypectomy, and more.

Patient Resources

AGA’s GI Patient Center can help your patients understand the need for CRC screening, colorectal cancer symptoms and risks, available screening tests, and the importance of preparing for a colonoscopy. Visit patient.gastro.org to access patient education materials.

Join the Conversation

We’ll be sharing resources and encouraging screenings on social media all month long. Join us as we remind everyone that 45 is the new 50.

What gastroenterologists need to know about the 2024 Medicare payment rules

Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) Final Rule

Cuts to physician payments continue: The final calendar year (CY) 2024 MPFS conversion factor will be $32.7442, a cut of approximately 3.4% from CY 2023, unless Congress acts. The reduction is the result of several factors, including the statutory base payment update of 0 percent, the reduction in assistance provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (from 2.5% for 2023 to 1.25% for 2024), and budget neutrality adjustments of –2.18 percent resulting from CMS’ finalized policies.

New add-on code for complex care: CMS is finalizing complexity add-on code, G2211 (Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious condition or a complex condition), that it originally proposed in 2018 rulemaking. CMS noted that G2211 cannot be used with an office and outpatient E/M procedure reported with modifier –25. CMS further clarified that the add-on code “is not intended for use by a professional whose relationship with the patient is of a discrete, routine, or time-limited nature ...” CMS further stated, “The inherent complexity that this code (G2211) captures is not in the clinical condition itself ... but rather the cognitive load of the continued responsibility of being the focal point for all needed services for this patient.” For gastroenterologists, it is reasonable to assume G2211 could be reported for care of patients with complex, chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and/or chronic liver disease.

CMS to align split (or shared) visit policy with CPT rules: Originally, CMS proposed to again delay “through at least December 31, 2024” its planned implementation of defining the “substantive portion” of a split/shared visit as more than half of the total time. However, after the American Medical Association’s CPT Editorial Panel, the body responsible for maintaining the CPT code set, issued new guidelines for split (or shared) services CMS decided to finalize the following policy to align with those guidelines: “Substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit, or a substantive part of the medical decision making except as otherwise provided in this paragraph. For critical care visits, substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit.”

While the CPT guidance states, “If code selection is based on total time on the date of the encounter, the service is reported by the professional who spent the majority of the face-to-face or non-face-to-face time performing the service,” this direction does not appear in the finalized CMS language.

CMS has extended Telehealth flexibility provisions through Dec. 31, 2024:

- Reporting of Home Address — CMS will continue to permit distant site practitioners to use their currently enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from their home through CY 2024.

- Place of Service (POS) for Medicare Telehealth Services — Beginning in CY 2024, claims billed with POS 10 (Telehealth Provided in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the non-facility rate, and claims billed with POS 02 (Telehealth Provided Other than in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the facility rate. CMS also clarified that modifier –95 should be used when the clinician is in the hospital and the patient is at home.

- Direct Supervision with Virtual Presence — CMS will continue to define direct supervision to permit the presence and “immediate availability” of the supervising practitioner through real-time audio and visual interactive telecommunications through CY 2024.

- Supervision of Residents in Teaching Settings — CMS will allow teaching physicians to have a virtual presence (to continue to include real-time audio and video observation by the teaching physician) in all teaching settings, but only in clinical instances when the service is furnished virtually, through CY 2024.

- Telephone E/M Services — CMS will continue to pay for CPT codes for telephone assessment and management services (99441-99443) through CY 2024.

Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) Final Rule

Hospital and ASC payments will increase: Conversion factors will increase 3.1% to $87.38 for hospitals and $53.51 for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

Hospital payments for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) increase: The GI societies successfully advocated for a 67% increase to the facility payment for POEM. To better align with the procedure’s cost, CMS will place CPT code 43497 for POEM into a higher-level Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) (5331 — Complex GI procedures) with a facility payment of $5,435.83.

Cuts to hospital payments for some Level 3 upper GI procedures: CMS has finalized moving the following GI CPT codes that had previously been assigned to APC 5303 (Level 3 Upper GI Procedures — $3,260.69) to APC 5302 (Level 2 Upper GI Procedures — $1,814.88) without explanation and against advice from AGA and the GI societies. This will result in payment cuts of 44% to hospitals.

- 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

- 43263 (ERCP with pressure measurement, sphincter of Oddi)

- 43275 (ERCP, remove foreign body/stent biliary/pancreatic duct)

GI Comprehensive APC complexity adjustments: Based on a cost and volume threshold, CMS sometimes makes payment adjustments for Comprehensive APCs when two procedures are performed together. In response to comments received, CMS is adding the following procedures to the list of code combinations eligible for an increased payment via the Complexity Adjustment.

- CPT 43270 (EGD, ablate tumor polyp/lesion with dilation and wire)

- CPT 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

For more information, see 2024 the payment rules summary and payment tables at https://gastro.org/practice-resources/reimbursement.

The Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee members have no conflicts of interest.

Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) Final Rule

Cuts to physician payments continue: The final calendar year (CY) 2024 MPFS conversion factor will be $32.7442, a cut of approximately 3.4% from CY 2023, unless Congress acts. The reduction is the result of several factors, including the statutory base payment update of 0 percent, the reduction in assistance provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (from 2.5% for 2023 to 1.25% for 2024), and budget neutrality adjustments of –2.18 percent resulting from CMS’ finalized policies.

New add-on code for complex care: CMS is finalizing complexity add-on code, G2211 (Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious condition or a complex condition), that it originally proposed in 2018 rulemaking. CMS noted that G2211 cannot be used with an office and outpatient E/M procedure reported with modifier –25. CMS further clarified that the add-on code “is not intended for use by a professional whose relationship with the patient is of a discrete, routine, or time-limited nature ...” CMS further stated, “The inherent complexity that this code (G2211) captures is not in the clinical condition itself ... but rather the cognitive load of the continued responsibility of being the focal point for all needed services for this patient.” For gastroenterologists, it is reasonable to assume G2211 could be reported for care of patients with complex, chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and/or chronic liver disease.

CMS to align split (or shared) visit policy with CPT rules: Originally, CMS proposed to again delay “through at least December 31, 2024” its planned implementation of defining the “substantive portion” of a split/shared visit as more than half of the total time. However, after the American Medical Association’s CPT Editorial Panel, the body responsible for maintaining the CPT code set, issued new guidelines for split (or shared) services CMS decided to finalize the following policy to align with those guidelines: “Substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit, or a substantive part of the medical decision making except as otherwise provided in this paragraph. For critical care visits, substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit.”

While the CPT guidance states, “If code selection is based on total time on the date of the encounter, the service is reported by the professional who spent the majority of the face-to-face or non-face-to-face time performing the service,” this direction does not appear in the finalized CMS language.

CMS has extended Telehealth flexibility provisions through Dec. 31, 2024:

- Reporting of Home Address — CMS will continue to permit distant site practitioners to use their currently enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from their home through CY 2024.

- Place of Service (POS) for Medicare Telehealth Services — Beginning in CY 2024, claims billed with POS 10 (Telehealth Provided in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the non-facility rate, and claims billed with POS 02 (Telehealth Provided Other than in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the facility rate. CMS also clarified that modifier –95 should be used when the clinician is in the hospital and the patient is at home.

- Direct Supervision with Virtual Presence — CMS will continue to define direct supervision to permit the presence and “immediate availability” of the supervising practitioner through real-time audio and visual interactive telecommunications through CY 2024.

- Supervision of Residents in Teaching Settings — CMS will allow teaching physicians to have a virtual presence (to continue to include real-time audio and video observation by the teaching physician) in all teaching settings, but only in clinical instances when the service is furnished virtually, through CY 2024.

- Telephone E/M Services — CMS will continue to pay for CPT codes for telephone assessment and management services (99441-99443) through CY 2024.

Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) Final Rule

Hospital and ASC payments will increase: Conversion factors will increase 3.1% to $87.38 for hospitals and $53.51 for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

Hospital payments for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) increase: The GI societies successfully advocated for a 67% increase to the facility payment for POEM. To better align with the procedure’s cost, CMS will place CPT code 43497 for POEM into a higher-level Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) (5331 — Complex GI procedures) with a facility payment of $5,435.83.

Cuts to hospital payments for some Level 3 upper GI procedures: CMS has finalized moving the following GI CPT codes that had previously been assigned to APC 5303 (Level 3 Upper GI Procedures — $3,260.69) to APC 5302 (Level 2 Upper GI Procedures — $1,814.88) without explanation and against advice from AGA and the GI societies. This will result in payment cuts of 44% to hospitals.

- 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

- 43263 (ERCP with pressure measurement, sphincter of Oddi)

- 43275 (ERCP, remove foreign body/stent biliary/pancreatic duct)

GI Comprehensive APC complexity adjustments: Based on a cost and volume threshold, CMS sometimes makes payment adjustments for Comprehensive APCs when two procedures are performed together. In response to comments received, CMS is adding the following procedures to the list of code combinations eligible for an increased payment via the Complexity Adjustment.

- CPT 43270 (EGD, ablate tumor polyp/lesion with dilation and wire)

- CPT 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

For more information, see 2024 the payment rules summary and payment tables at https://gastro.org/practice-resources/reimbursement.

The Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee members have no conflicts of interest.

Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) Final Rule

Cuts to physician payments continue: The final calendar year (CY) 2024 MPFS conversion factor will be $32.7442, a cut of approximately 3.4% from CY 2023, unless Congress acts. The reduction is the result of several factors, including the statutory base payment update of 0 percent, the reduction in assistance provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (from 2.5% for 2023 to 1.25% for 2024), and budget neutrality adjustments of –2.18 percent resulting from CMS’ finalized policies.

New add-on code for complex care: CMS is finalizing complexity add-on code, G2211 (Visit complexity inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single, serious condition or a complex condition), that it originally proposed in 2018 rulemaking. CMS noted that G2211 cannot be used with an office and outpatient E/M procedure reported with modifier –25. CMS further clarified that the add-on code “is not intended for use by a professional whose relationship with the patient is of a discrete, routine, or time-limited nature ...” CMS further stated, “The inherent complexity that this code (G2211) captures is not in the clinical condition itself ... but rather the cognitive load of the continued responsibility of being the focal point for all needed services for this patient.” For gastroenterologists, it is reasonable to assume G2211 could be reported for care of patients with complex, chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and/or chronic liver disease.

CMS to align split (or shared) visit policy with CPT rules: Originally, CMS proposed to again delay “through at least December 31, 2024” its planned implementation of defining the “substantive portion” of a split/shared visit as more than half of the total time. However, after the American Medical Association’s CPT Editorial Panel, the body responsible for maintaining the CPT code set, issued new guidelines for split (or shared) services CMS decided to finalize the following policy to align with those guidelines: “Substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit, or a substantive part of the medical decision making except as otherwise provided in this paragraph. For critical care visits, substantive portion means more than half of the total time spent by the physician and nonphysician practitioner performing the split (or shared) visit.”

While the CPT guidance states, “If code selection is based on total time on the date of the encounter, the service is reported by the professional who spent the majority of the face-to-face or non-face-to-face time performing the service,” this direction does not appear in the finalized CMS language.

CMS has extended Telehealth flexibility provisions through Dec. 31, 2024:

- Reporting of Home Address — CMS will continue to permit distant site practitioners to use their currently enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from their home through CY 2024.

- Place of Service (POS) for Medicare Telehealth Services — Beginning in CY 2024, claims billed with POS 10 (Telehealth Provided in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the non-facility rate, and claims billed with POS 02 (Telehealth Provided Other than in Patient’s Home) will be paid at the facility rate. CMS also clarified that modifier –95 should be used when the clinician is in the hospital and the patient is at home.

- Direct Supervision with Virtual Presence — CMS will continue to define direct supervision to permit the presence and “immediate availability” of the supervising practitioner through real-time audio and visual interactive telecommunications through CY 2024.

- Supervision of Residents in Teaching Settings — CMS will allow teaching physicians to have a virtual presence (to continue to include real-time audio and video observation by the teaching physician) in all teaching settings, but only in clinical instances when the service is furnished virtually, through CY 2024.

- Telephone E/M Services — CMS will continue to pay for CPT codes for telephone assessment and management services (99441-99443) through CY 2024.

Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) Final Rule

Hospital and ASC payments will increase: Conversion factors will increase 3.1% to $87.38 for hospitals and $53.51 for ASCs that meet applicable quality reporting requirements.

Hospital payments for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) increase: The GI societies successfully advocated for a 67% increase to the facility payment for POEM. To better align with the procedure’s cost, CMS will place CPT code 43497 for POEM into a higher-level Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) (5331 — Complex GI procedures) with a facility payment of $5,435.83.

Cuts to hospital payments for some Level 3 upper GI procedures: CMS has finalized moving the following GI CPT codes that had previously been assigned to APC 5303 (Level 3 Upper GI Procedures — $3,260.69) to APC 5302 (Level 2 Upper GI Procedures — $1,814.88) without explanation and against advice from AGA and the GI societies. This will result in payment cuts of 44% to hospitals.

- 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

- 43263 (ERCP with pressure measurement, sphincter of Oddi)

- 43275 (ERCP, remove foreign body/stent biliary/pancreatic duct)

GI Comprehensive APC complexity adjustments: Based on a cost and volume threshold, CMS sometimes makes payment adjustments for Comprehensive APCs when two procedures are performed together. In response to comments received, CMS is adding the following procedures to the list of code combinations eligible for an increased payment via the Complexity Adjustment.

- CPT 43270 (EGD, ablate tumor polyp/lesion with dilation and wire)

- CPT 43252 (EGD, flexible transoral with optical microscopy)

For more information, see 2024 the payment rules summary and payment tables at https://gastro.org/practice-resources/reimbursement.

The Coverage and Reimbursement Subcommittee members have no conflicts of interest.

Membership priorities shape the AGA advocacy agenda

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

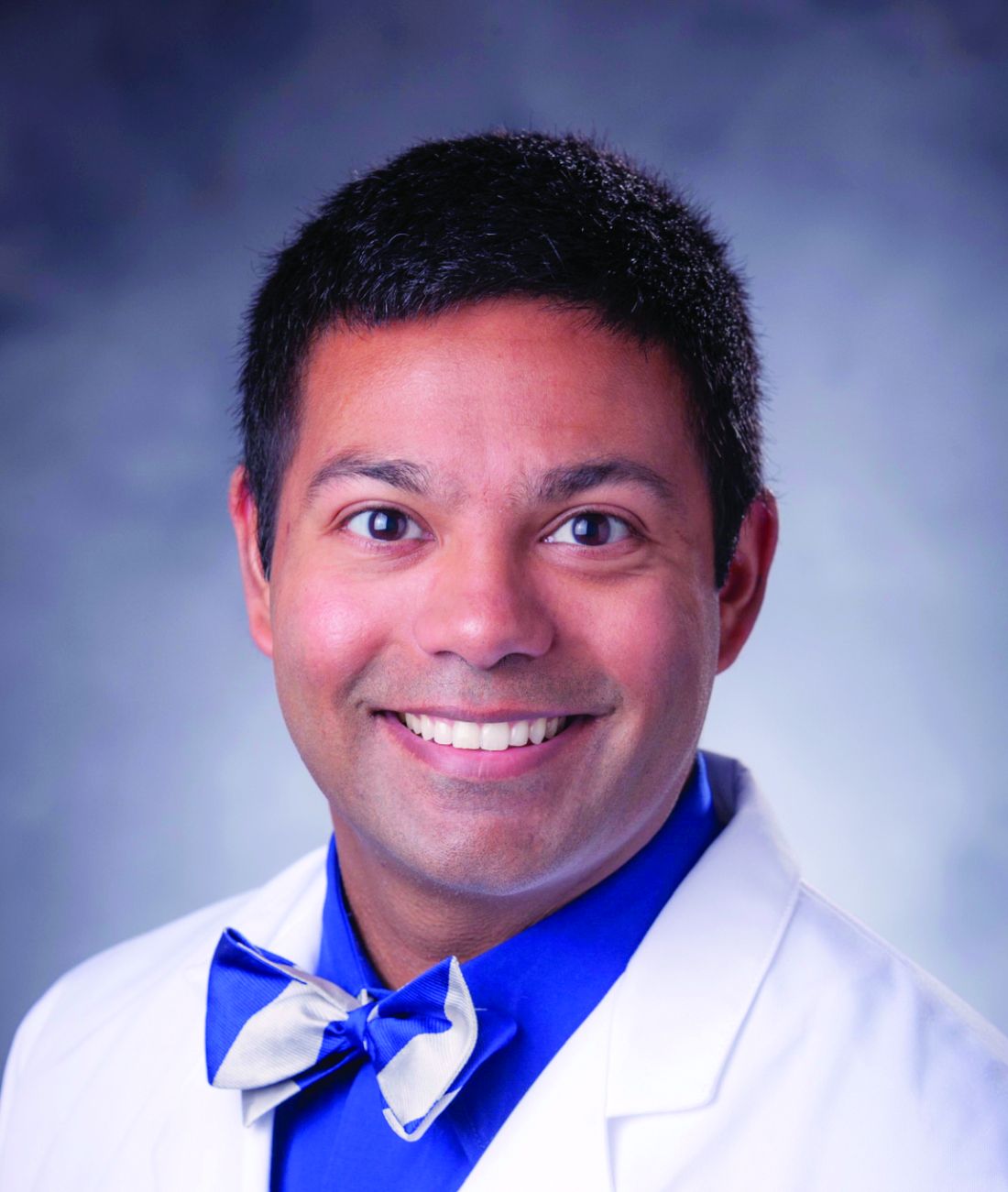

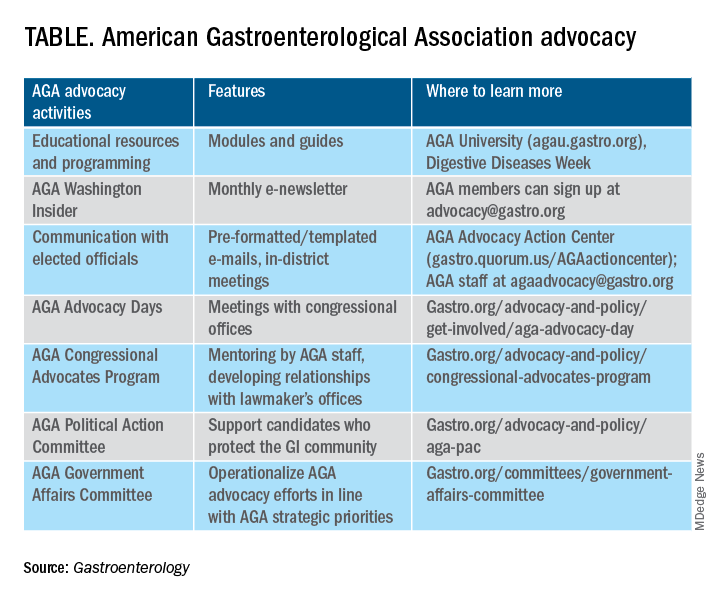

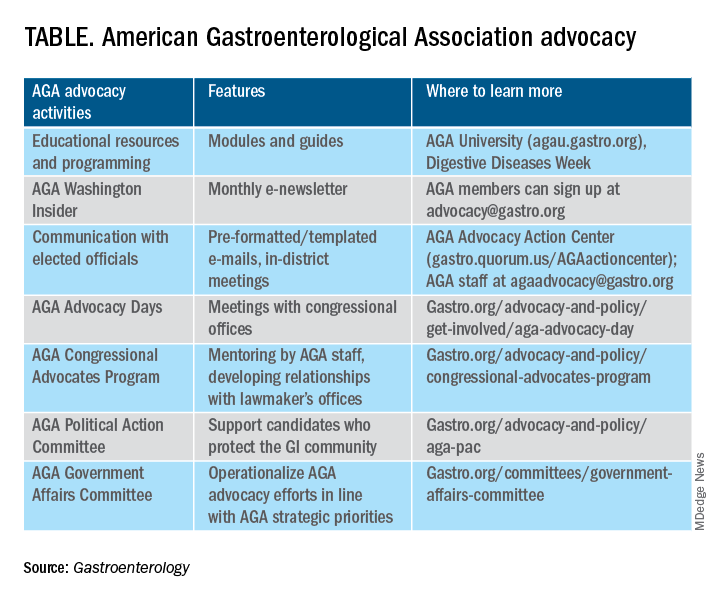

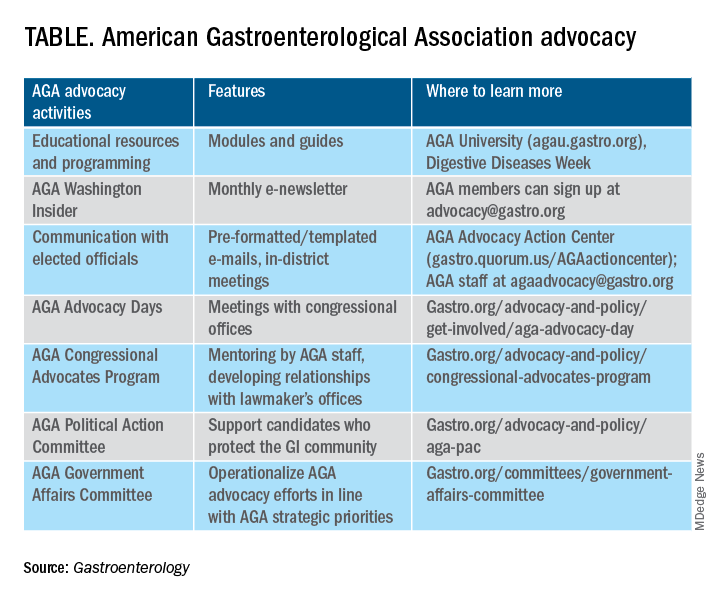

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Reforming prior authorization remains AGA’s top policy priority

Reforming prior authorization polices to reduce red tape for physicians and help patients get the care they need in a timely manner is the AGA’s number one policy priority as it impacts every gastroenterologist regardless of practice setting. We have seen an increase in prior authorization policies from every major insurer. The most recent prior authorization program to impact gastroenterologists was announced by UnitedHealthcare (UHC) in March for implementation on June 1, 2023 and will require prior authorization for most colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopy procedures with the exception of screening colonoscopy.1 This policy is a step back at a time when payers should be developing innovative policies in collaboration with health care providers to improve patient care.

UHC’s GI prior authorization policy

AGA met with UHC in March to discuss their plan to require prior authorization for most GI endoscopy procedures. We stressed how this change will cause care delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from undergoing medically recommended procedures, exacerbate existing sociodemographic disparities in care and outcomes, and add unnecessary paperwork burden to physicians who have mounting rates of burnout.

Linda Lee, MD, medical director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, recently spoke of the impact this policy will have on gastroenterologists and their patients. “We all know that requiring prior authorizations really only leads to more bureaucracy within the insurance company, as well as within each health care provider’s practice, because we need people to fill out these prior authorization forms, waste time trying to get through to their 1-800 number to speak with someone who has no clinical knowledge, then be told we need to speak with someone else who actually does have some medical knowledge about why these procedures are necessary.”

However, Dr. Lee stressed that “most importantly, this will lead to poorer patient care with delays in care as we are struggling to wade through the morass of prior authorization while patients are bleeding, not able to swallow, vomiting, and more while waiting for their insurance company to approve their potentially life-saving procedures.”

We were particularly troubled that UHC announced this policy during Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, given the need to screen more Americans for colorectal cancer which remains the nation’s number two cancer killer. The UHC program would require a PA on surveillance colonoscopy for those patients who have previously had polyps removed and are at a higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.

“We know that patients with high-risk adenomas or advanced sessile serrated lesions have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer and timely access to the necessary surveillance colonoscopy is critical,” said David Lieberman, MD, past president of the AGA and chair of the AGA Executive Committee on the Screening Continuum.

AGA plans to meet with UHC again to ask them to reconsider this policy, but we need your advocacy now to tell United how this will impact you and your patients.

How you can help stop UHC’s prior authorization program

Write to UHC: Tell UHC how this policy would impact you and your patients. Contact their CEO using our customizable letter2 that outlines the impact of United’s GI endoscopy prior authorization program on gastroenterologists and their patients available on the AGA Advocacy Action Center.

Use social media: Tag United (@UHC) on Twitter and tell them how this burdensome program will cause delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from seeking treatment, and exacerbate existing disparities in care, all while saddling physicians with even more paperwork. Once you’ve tweeted, tag your colleagues and encourage them to get involved.

AGA is working to reform prior authorization

The AGA has supported federal legislation that would streamline prior authorization processes in Medicare Advantage (MA), the private insurance plans that contract with the Medicare program, given the explosion of these policies over the past several years. The Improving Seniors Timely Access to Care Act, bipartisan, bicameral legislation, would reduce prior authorization burdens by:

- Establishing an electronic prior authorization (ePA) program and require MA plans to adopt ePA capabilities.

- Requiring the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a list of items and services eligible for real-time decisions under an MA ePA program.

- Standardizing and streamlining the prior authorization process for routinely approved items and services.

- Ensuring prior authorization requests are reviewed by qualified medical personnel.

- Increasing transparency around MA prior authorization requirements and their use.

- Protecting beneficiaries from any disruptions in care due to prior authorization requirements as they transition between MA plans.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has also recognized the impact that prior authorization is having on physician wellness and how it is contributing to physician burnout. The agency recently proposed implementing many of the provisions that are outlined in the legislation, and AGA has expressed our support for moving forward with many of their proposals.

Earlier this year, Shivan Mehta, MD, MPH, met with CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, to express AGA’s support for prior authorization reform and discussed how it impacts how patients with chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease maintain continuity of care. He also stressed how prior authorization further exacerbates health inequities since it creates an additional barrier to care when barriers already exist.

AGA is taking a multi-pronged approach to advocating for prior authorization reform and reducing paperwork through legislative advocacy, regulatory advocacy with the CMS, and payer advocacy. We can’t do this alone. Join our AGA Advocacy Center3 and get involved in our AGA Congressional Advocates Program.4The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1. UnitedHealthcare (2023 Mar 01) New requirements for gastroenterology services.

2. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Tell United to Stop New Prior Auth Requirements!

3. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Advocacy & Policy. Get Involved.

4. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Congressional Advocates Program.

Reforming prior authorization polices to reduce red tape for physicians and help patients get the care they need in a timely manner is the AGA’s number one policy priority as it impacts every gastroenterologist regardless of practice setting. We have seen an increase in prior authorization policies from every major insurer. The most recent prior authorization program to impact gastroenterologists was announced by UnitedHealthcare (UHC) in March for implementation on June 1, 2023 and will require prior authorization for most colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopy procedures with the exception of screening colonoscopy.1 This policy is a step back at a time when payers should be developing innovative policies in collaboration with health care providers to improve patient care.

UHC’s GI prior authorization policy

AGA met with UHC in March to discuss their plan to require prior authorization for most GI endoscopy procedures. We stressed how this change will cause care delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from undergoing medically recommended procedures, exacerbate existing sociodemographic disparities in care and outcomes, and add unnecessary paperwork burden to physicians who have mounting rates of burnout.

Linda Lee, MD, medical director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, recently spoke of the impact this policy will have on gastroenterologists and their patients. “We all know that requiring prior authorizations really only leads to more bureaucracy within the insurance company, as well as within each health care provider’s practice, because we need people to fill out these prior authorization forms, waste time trying to get through to their 1-800 number to speak with someone who has no clinical knowledge, then be told we need to speak with someone else who actually does have some medical knowledge about why these procedures are necessary.”

However, Dr. Lee stressed that “most importantly, this will lead to poorer patient care with delays in care as we are struggling to wade through the morass of prior authorization while patients are bleeding, not able to swallow, vomiting, and more while waiting for their insurance company to approve their potentially life-saving procedures.”

We were particularly troubled that UHC announced this policy during Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, given the need to screen more Americans for colorectal cancer which remains the nation’s number two cancer killer. The UHC program would require a PA on surveillance colonoscopy for those patients who have previously had polyps removed and are at a higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.

“We know that patients with high-risk adenomas or advanced sessile serrated lesions have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer and timely access to the necessary surveillance colonoscopy is critical,” said David Lieberman, MD, past president of the AGA and chair of the AGA Executive Committee on the Screening Continuum.

AGA plans to meet with UHC again to ask them to reconsider this policy, but we need your advocacy now to tell United how this will impact you and your patients.

How you can help stop UHC’s prior authorization program

Write to UHC: Tell UHC how this policy would impact you and your patients. Contact their CEO using our customizable letter2 that outlines the impact of United’s GI endoscopy prior authorization program on gastroenterologists and their patients available on the AGA Advocacy Action Center.

Use social media: Tag United (@UHC) on Twitter and tell them how this burdensome program will cause delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from seeking treatment, and exacerbate existing disparities in care, all while saddling physicians with even more paperwork. Once you’ve tweeted, tag your colleagues and encourage them to get involved.

AGA is working to reform prior authorization

The AGA has supported federal legislation that would streamline prior authorization processes in Medicare Advantage (MA), the private insurance plans that contract with the Medicare program, given the explosion of these policies over the past several years. The Improving Seniors Timely Access to Care Act, bipartisan, bicameral legislation, would reduce prior authorization burdens by:

- Establishing an electronic prior authorization (ePA) program and require MA plans to adopt ePA capabilities.

- Requiring the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a list of items and services eligible for real-time decisions under an MA ePA program.

- Standardizing and streamlining the prior authorization process for routinely approved items and services.

- Ensuring prior authorization requests are reviewed by qualified medical personnel.

- Increasing transparency around MA prior authorization requirements and their use.

- Protecting beneficiaries from any disruptions in care due to prior authorization requirements as they transition between MA plans.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has also recognized the impact that prior authorization is having on physician wellness and how it is contributing to physician burnout. The agency recently proposed implementing many of the provisions that are outlined in the legislation, and AGA has expressed our support for moving forward with many of their proposals.

Earlier this year, Shivan Mehta, MD, MPH, met with CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, to express AGA’s support for prior authorization reform and discussed how it impacts how patients with chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease maintain continuity of care. He also stressed how prior authorization further exacerbates health inequities since it creates an additional barrier to care when barriers already exist.

AGA is taking a multi-pronged approach to advocating for prior authorization reform and reducing paperwork through legislative advocacy, regulatory advocacy with the CMS, and payer advocacy. We can’t do this alone. Join our AGA Advocacy Center3 and get involved in our AGA Congressional Advocates Program.4The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1. UnitedHealthcare (2023 Mar 01) New requirements for gastroenterology services.

2. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Tell United to Stop New Prior Auth Requirements!

3. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Advocacy & Policy. Get Involved.

4. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Congressional Advocates Program.

Reforming prior authorization polices to reduce red tape for physicians and help patients get the care they need in a timely manner is the AGA’s number one policy priority as it impacts every gastroenterologist regardless of practice setting. We have seen an increase in prior authorization policies from every major insurer. The most recent prior authorization program to impact gastroenterologists was announced by UnitedHealthcare (UHC) in March for implementation on June 1, 2023 and will require prior authorization for most colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopy procedures with the exception of screening colonoscopy.1 This policy is a step back at a time when payers should be developing innovative policies in collaboration with health care providers to improve patient care.

UHC’s GI prior authorization policy

AGA met with UHC in March to discuss their plan to require prior authorization for most GI endoscopy procedures. We stressed how this change will cause care delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from undergoing medically recommended procedures, exacerbate existing sociodemographic disparities in care and outcomes, and add unnecessary paperwork burden to physicians who have mounting rates of burnout.

Linda Lee, MD, medical director of endoscopy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, recently spoke of the impact this policy will have on gastroenterologists and their patients. “We all know that requiring prior authorizations really only leads to more bureaucracy within the insurance company, as well as within each health care provider’s practice, because we need people to fill out these prior authorization forms, waste time trying to get through to their 1-800 number to speak with someone who has no clinical knowledge, then be told we need to speak with someone else who actually does have some medical knowledge about why these procedures are necessary.”

However, Dr. Lee stressed that “most importantly, this will lead to poorer patient care with delays in care as we are struggling to wade through the morass of prior authorization while patients are bleeding, not able to swallow, vomiting, and more while waiting for their insurance company to approve their potentially life-saving procedures.”

We were particularly troubled that UHC announced this policy during Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, given the need to screen more Americans for colorectal cancer which remains the nation’s number two cancer killer. The UHC program would require a PA on surveillance colonoscopy for those patients who have previously had polyps removed and are at a higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.

“We know that patients with high-risk adenomas or advanced sessile serrated lesions have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer and timely access to the necessary surveillance colonoscopy is critical,” said David Lieberman, MD, past president of the AGA and chair of the AGA Executive Committee on the Screening Continuum.

AGA plans to meet with UHC again to ask them to reconsider this policy, but we need your advocacy now to tell United how this will impact you and your patients.

How you can help stop UHC’s prior authorization program

Write to UHC: Tell UHC how this policy would impact you and your patients. Contact their CEO using our customizable letter2 that outlines the impact of United’s GI endoscopy prior authorization program on gastroenterologists and their patients available on the AGA Advocacy Action Center.

Use social media: Tag United (@UHC) on Twitter and tell them how this burdensome program will cause delays for high-risk individuals, deter patients from seeking treatment, and exacerbate existing disparities in care, all while saddling physicians with even more paperwork. Once you’ve tweeted, tag your colleagues and encourage them to get involved.

AGA is working to reform prior authorization

The AGA has supported federal legislation that would streamline prior authorization processes in Medicare Advantage (MA), the private insurance plans that contract with the Medicare program, given the explosion of these policies over the past several years. The Improving Seniors Timely Access to Care Act, bipartisan, bicameral legislation, would reduce prior authorization burdens by:

- Establishing an electronic prior authorization (ePA) program and require MA plans to adopt ePA capabilities.

- Requiring the Secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a list of items and services eligible for real-time decisions under an MA ePA program.

- Standardizing and streamlining the prior authorization process for routinely approved items and services.

- Ensuring prior authorization requests are reviewed by qualified medical personnel.

- Increasing transparency around MA prior authorization requirements and their use.

- Protecting beneficiaries from any disruptions in care due to prior authorization requirements as they transition between MA plans.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has also recognized the impact that prior authorization is having on physician wellness and how it is contributing to physician burnout. The agency recently proposed implementing many of the provisions that are outlined in the legislation, and AGA has expressed our support for moving forward with many of their proposals.

Earlier this year, Shivan Mehta, MD, MPH, met with CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, to express AGA’s support for prior authorization reform and discussed how it impacts how patients with chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease maintain continuity of care. He also stressed how prior authorization further exacerbates health inequities since it creates an additional barrier to care when barriers already exist.

AGA is taking a multi-pronged approach to advocating for prior authorization reform and reducing paperwork through legislative advocacy, regulatory advocacy with the CMS, and payer advocacy. We can’t do this alone. Join our AGA Advocacy Center3 and get involved in our AGA Congressional Advocates Program.4The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1. UnitedHealthcare (2023 Mar 01) New requirements for gastroenterology services.

2. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Tell United to Stop New Prior Auth Requirements!

3. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Advocacy Action Center. Advocacy & Policy. Get Involved.

4. American Gastroenterological Association (n.d.) AGA Congressional Advocates Program.

New coding policies to prevent surprise billing for CRC screening

The Departments of Labor, Health & Human Services, and the Treasury issued guidance in 2022 that plans and insurers “must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive non-invasive stool-based screening test” for plan or policy years1 beginning on or after May 31, 2022, and, further, “may not impose cost-sharing with respect to a polyp removal during a colonoscopy performed as a screening procedure.”2 So why are so many patients still being charged fees for these screening services? In many cases, the answer comes down to missing code modifiers.

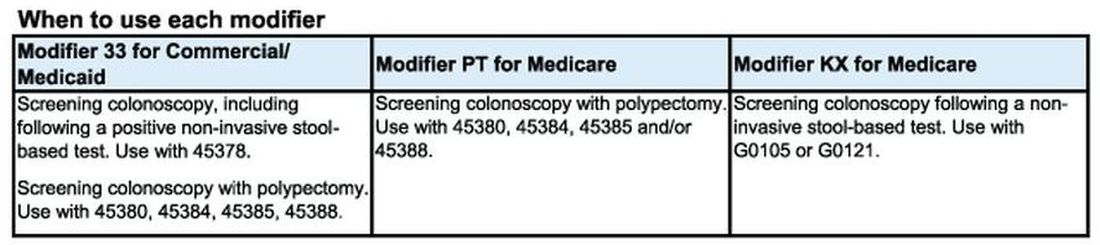

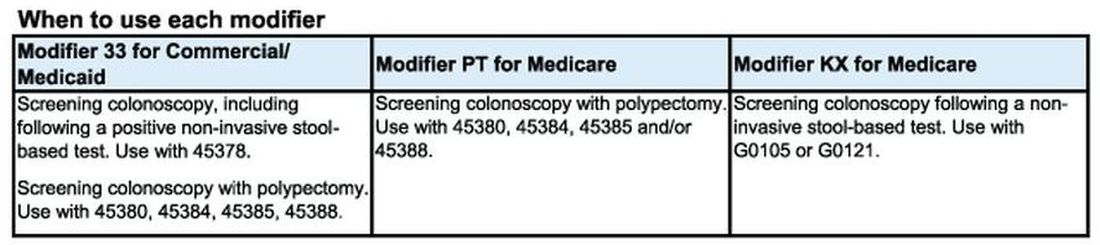

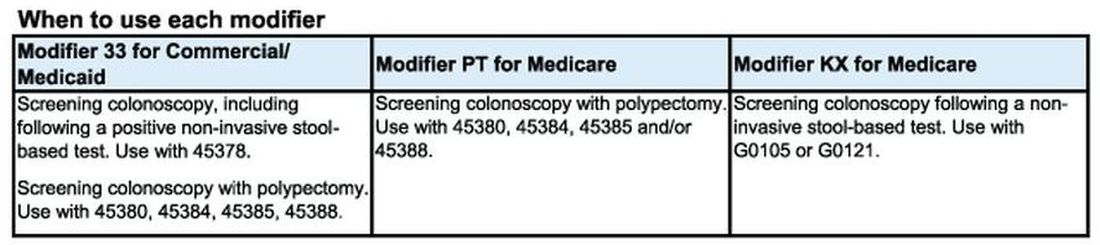

Commercial insurers want you to use modifier 33

AGA spoke to Elevance (formerly Anthem), Cigna, Aetna, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association about how physicians should report colorectal cancer screening procedures and tests. They said using the 33 modifier (preventive service) is essential for their systems to trigger the screening benefits for beneficiaries. Without the 33 modifier, the claim will be processed as a diagnostic service, and coinsurance may apply.

According to the CPT manual, modifier 33 should be used “when the primary purpose of the service is the delivery of an evidence-based service in accordance with a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force A or B rating in effect and other preventive services identified in preventive mandates (legislative or regulatory) ...” Use modifier 33 with colonoscopies that start out as screening procedures and with colonoscopies following a positive non-invasive stool-based test, like fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or Cologuard™ multi-target stool DNA test.

It is important to note that modifier 33 won’t ensure all screening colonoscopy claims are paid, because not all commercial plans are required to cover 100 percent of the costs of CRC screening tests and procedures. For example, employer-sponsored insurance plans and legacy plans can choose not to adopt the expanded CRC benefits. Patients who are covered under these plans may not be aware that their CRC test or procedure will not be fully covered. These patients may still receive a “surprise” bill if their screening colonoscopy requires removal of polyps or if they have a colonoscopy following a positive non-invasive CRC test.

Medicare wants you to use modifiers PT and KX, but not together

CMS uses Healthcare Common Procedural Coding System (HCPCS) codes to differentiate between screening and diagnostic colonoscopies to apply screening benefits. For Medicare beneficiaries who choose colonoscopy as their CRC screening, use HCPCS code G0105 (Colorectal cancer screening; colonoscopy on individual at high risk) or G0121 (Colorectal cancer screening; colonoscopy on individual not meeting the criteria for high risk) for screening colonoscopies as appropriate. No modifier is necessary with G0105 or G0121.

Effective for claims with dates of service on or after 1/1/2023, use the appropriate HCPCS codes G0105 or G0121 with the KX modifier for colonoscopy following a positive result for any of the following non-invasive stool-based CRC screening tests:

• Screening guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) (CPT 82270)

• Screening immunoassay-based fecal occult blood test (iFOBT) (HCPCS G0328)

• Cologuard™ – multi-target stool DNA (sDNA) test (CPT 81528)

According to the guidance in the CMS Manual System, if modifier KX is not added to G0105 or G0121 for colonoscopy following a positive non-invasive stool-based test, Medicare will return the screening colonoscopy claim as “unprocessable.”3 If this happens, add modifier KX and resubmit the claim.

If polyps are removed during a screening colonoscopy, use the appropriate CPT code (45380, 45384, 45385, 45388) and add modifier PT (colorectal cancer screening test; converted to diagnostic test or other procedure) to each CPT code for Medicare. However, it is important to note that if a polyp is removed during a screening colonoscopy, the Medicare beneficiary is responsible for 15% of the cost from 2023 to 2026. This falls to 10% of the cost from 2027 to 2029, and by 2030 it will be covered 100% by Medicare. Some Medicare beneficiaries are not aware that Medicare has not fully eliminated the coinsurance responsibility yet.

What to do if your patient gets an unexpected bill

If your patient gets an unexpected bill and you coded the procedure correctly with the correct modifier, direct them to the AGA GI Patient Care Center’s “Colorectal cancer screening: what to expect when paying” resource for help with next steps.4

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1. U.S. Department of Labor (2022, Jan. 10) FAQs About Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 51. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/aca-part-51.pdf

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.d.) Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 12. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs12.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2023, Jan. 27) CMS Manual System Pub 100-03 Medicare National Coverage Determinations Transmittal 11824. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/r11824ncd.pdf.

4. American Gastroenterological Association (2023, Feb. 21) AGA GI Patient Center Colorectal Cancer Screening: What to expect when paying. https://patient.gastro.org/paying-for-your-colonoscopy/.

The Departments of Labor, Health & Human Services, and the Treasury issued guidance in 2022 that plans and insurers “must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive non-invasive stool-based screening test” for plan or policy years1 beginning on or after May 31, 2022, and, further, “may not impose cost-sharing with respect to a polyp removal during a colonoscopy performed as a screening procedure.”2 So why are so many patients still being charged fees for these screening services? In many cases, the answer comes down to missing code modifiers.

Commercial insurers want you to use modifier 33

AGA spoke to Elevance (formerly Anthem), Cigna, Aetna, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association about how physicians should report colorectal cancer screening procedures and tests. They said using the 33 modifier (preventive service) is essential for their systems to trigger the screening benefits for beneficiaries. Without the 33 modifier, the claim will be processed as a diagnostic service, and coinsurance may apply.

According to the CPT manual, modifier 33 should be used “when the primary purpose of the service is the delivery of an evidence-based service in accordance with a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force A or B rating in effect and other preventive services identified in preventive mandates (legislative or regulatory) ...” Use modifier 33 with colonoscopies that start out as screening procedures and with colonoscopies following a positive non-invasive stool-based test, like fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or Cologuard™ multi-target stool DNA test.

It is important to note that modifier 33 won’t ensure all screening colonoscopy claims are paid, because not all commercial plans are required to cover 100 percent of the costs of CRC screening tests and procedures. For example, employer-sponsored insurance plans and legacy plans can choose not to adopt the expanded CRC benefits. Patients who are covered under these plans may not be aware that their CRC test or procedure will not be fully covered. These patients may still receive a “surprise” bill if their screening colonoscopy requires removal of polyps or if they have a colonoscopy following a positive non-invasive CRC test.

Medicare wants you to use modifiers PT and KX, but not together

CMS uses Healthcare Common Procedural Coding System (HCPCS) codes to differentiate between screening and diagnostic colonoscopies to apply screening benefits. For Medicare beneficiaries who choose colonoscopy as their CRC screening, use HCPCS code G0105 (Colorectal cancer screening; colonoscopy on individual at high risk) or G0121 (Colorectal cancer screening; colonoscopy on individual not meeting the criteria for high risk) for screening colonoscopies as appropriate. No modifier is necessary with G0105 or G0121.

Effective for claims with dates of service on or after 1/1/2023, use the appropriate HCPCS codes G0105 or G0121 with the KX modifier for colonoscopy following a positive result for any of the following non-invasive stool-based CRC screening tests:

• Screening guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) (CPT 82270)

• Screening immunoassay-based fecal occult blood test (iFOBT) (HCPCS G0328)

• Cologuard™ – multi-target stool DNA (sDNA) test (CPT 81528)

According to the guidance in the CMS Manual System, if modifier KX is not added to G0105 or G0121 for colonoscopy following a positive non-invasive stool-based test, Medicare will return the screening colonoscopy claim as “unprocessable.”3 If this happens, add modifier KX and resubmit the claim.

If polyps are removed during a screening colonoscopy, use the appropriate CPT code (45380, 45384, 45385, 45388) and add modifier PT (colorectal cancer screening test; converted to diagnostic test or other procedure) to each CPT code for Medicare. However, it is important to note that if a polyp is removed during a screening colonoscopy, the Medicare beneficiary is responsible for 15% of the cost from 2023 to 2026. This falls to 10% of the cost from 2027 to 2029, and by 2030 it will be covered 100% by Medicare. Some Medicare beneficiaries are not aware that Medicare has not fully eliminated the coinsurance responsibility yet.

What to do if your patient gets an unexpected bill

If your patient gets an unexpected bill and you coded the procedure correctly with the correct modifier, direct them to the AGA GI Patient Care Center’s “Colorectal cancer screening: what to expect when paying” resource for help with next steps.4

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1. U.S. Department of Labor (2022, Jan. 10) FAQs About Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 51. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/aca-part-51.pdf

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.d.) Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 12. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs12.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2023, Jan. 27) CMS Manual System Pub 100-03 Medicare National Coverage Determinations Transmittal 11824. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/r11824ncd.pdf.

4. American Gastroenterological Association (2023, Feb. 21) AGA GI Patient Center Colorectal Cancer Screening: What to expect when paying. https://patient.gastro.org/paying-for-your-colonoscopy/.

The Departments of Labor, Health & Human Services, and the Treasury issued guidance in 2022 that plans and insurers “must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive non-invasive stool-based screening test” for plan or policy years1 beginning on or after May 31, 2022, and, further, “may not impose cost-sharing with respect to a polyp removal during a colonoscopy performed as a screening procedure.”2 So why are so many patients still being charged fees for these screening services? In many cases, the answer comes down to missing code modifiers.

Commercial insurers want you to use modifier 33

AGA spoke to Elevance (formerly Anthem), Cigna, Aetna, and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association about how physicians should report colorectal cancer screening procedures and tests. They said using the 33 modifier (preventive service) is essential for their systems to trigger the screening benefits for beneficiaries. Without the 33 modifier, the claim will be processed as a diagnostic service, and coinsurance may apply.

According to the CPT manual, modifier 33 should be used “when the primary purpose of the service is the delivery of an evidence-based service in accordance with a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force A or B rating in effect and other preventive services identified in preventive mandates (legislative or regulatory) ...” Use modifier 33 with colonoscopies that start out as screening procedures and with colonoscopies following a positive non-invasive stool-based test, like fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or Cologuard™ multi-target stool DNA test.