User login

Attitudes Surrounding Continuous Telemetry Utilization by Providers at an Academic Tertiary Medical Center

From the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Drs. Johnson, Knight, Maygers, and Zakaria), and Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC (Dr. Mock).

Abstract

- Objective: To determine patterns of telemetry use at a tertiary academic institution and identify factors contributing to noncompliance with guidelines regarding telemetry use.

- Methods: Web-based survey of 180 providers, including internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

- Results: Of the 180 providers surveyed, 67 (37%) replied. Most providers (76%) were unaware of guidelines regarding appropriate telemetry use and 85% selected inappropriate diagnoses as warranting telemetry. Only 21% routinely discontinued the telemetry order within 48 hours.

- Conclusions: Many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilize continuous telemetry inappropriately and are unaware of telemetry guidelines. These findings should guide interventions to improve telemetry utilization.

For many decades, telemetry has been widely used in the management and monitoring of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes (ACS), arrhythmias, cardiac events, and strokes [1]. In addition, telemetry has often been used in other clinical scenarios with less rigorous data supporting its use [2–4]. As a result, in 2004 the American Heart Association (AHA) issued guidelines providing recommendations for best practices in hospital ECG monitoring. Indications for telemetry were classified into 3 diagnosis-driven groups: class I (indicated in all patients), class II (indicated in most patients, may be of benefit) and class III (not indicated, no therapeutic benefit) [2]. However, these recommendations have not been widely followed and telemetry is inappropriately used for many inpatients [5,6].

There are several reasons why clinicians fail to adhere to guidelines, including knowledge deficits, attitudes regarding the current guidelines, and institution-specific factors influencing practitioner behaviors [7]. In response to reports of widespread telemetry overuse, the Choosing Wisely Campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has championed judicious telemetry use, advocating evidence-based, protocol-driven telemetry management for patients not in intensive care units who do not meet guideline-based criteria for continuous telemetry [8].

In order to understand patterns of telemetry use at our academic institution and identify factors associated with this practice, we systematically analyzed telemetry use perceptions through provider surveys. We hypothesized that providers have misperceptions about appropriate use of telemetry and that this knowledge gap results in overuse of telemetry at our institution.

Methods

Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center is a 400-bed academic medical center serving southeastern Baltimore. Providers included internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows who rotate to the medical center and Johns Hopkins Hospital, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs).

Current Telemetry Practice

Remote telemetric monitoring is available in all adult, non-intensive care units of the hospital except for the psychiatry unit. However, the number of monitors are limited and it is not possible to monitor every patient if the wards are at capacity. Obstetrics uses its own unique cardiac monitoring system and thus was not included in the survey. Each monitor (IntelliVue, Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands) is attached to the patient using 5 lead wires, with electrocardiographic data transmitted to a monitoring station based in the progressive care unit, a cardio-pulmonary step-down unit. Monitors can be ordered in one of 3 manners, as mandated by hospital policy:

- Continuous telemetry – Telemetry monitoring is uninterrupted until discontinued by a provider.

- Telemetry protocol – Within 12 hours of telemetry placement, a monitor technician generates a report, which is reviewed by the nurse caring for the patient. The nurse performs an electrocardiogram (ECG) if the patient meets pre-specified criteria for telemetry discontinuation, which includes the absence of arrhythmias, troponin elevations, chest pain, or hemodynamic instability. The repeat ECG is then read and signed by the provider. After these criteria are met, telemetry can be discontinued.

- Stroke telemetry protocol – Telemetry is applied for 48 hours, mainly for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Monitoring can be temporarily discontinued if the patient requires magnetic resonance imaging, which interferes with the telemetric monitors.

When entering any of the 3 possible telemetry orders in our computerized provider order entry system (Meditech, Westwood, MA), the ordering provider is required to indicate baseline rhythm, pacemaker presence, and desired heart rate warning parameters. Once the order is electronically signed, a monitor technician notes the order in a logbook and assigns the patient a telemeter, which is applied by the patient’s nurse.

If a monitored patient develops any predefined abnormal rhythm, audible alerts notify monitor technicians and an alert is sent to a portable telephone carried by the patient’s assigned nurse. Either the monitoring technician or the nurse then has the discretion to silence the alarm, note it in the chart, and/or contact the patient’s provider. If alerts are recorded, then a sample telemetry monitoring strip is saved into the patient’s paper medical chart.

Survey Instrument

After approval from the Johns Hopkins institutional review board, we queried providers who worked on the medicine and cardiology wards to assess the context and culture in which telemetry monitoring is used (see Appendix). The study was exempt from requiring informed consent. All staff had the option to decline study participation. We administered the survey using an online survey software program (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA), sending survey links via email to all internal medicine residents, cardiovascular disease fellows, internal medicine and cardiology teaching attending physicians, hospitalists, NPs, and PAs. Respondents completed the survey anonymously. To increase response rates, providers were sent a monthly reminder email. The survey was open from March 2014 to May 2014 for a total of 3 months.

Analysis

The survey data were compiled and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Mac version 14.4; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Variables are displayed as numbers and percentages, as appropriate.

Results

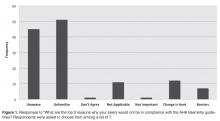

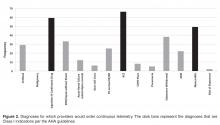

All providers reported having ordered telemetry, but almost all were either unaware of (76%) or only somewhat familiar with (21%) the AHA guidelines for appropriate telemetry use. Notably, the vast majority of fellows and residents reported that they were not at all familiar with the guidelines (100% and 96%, respectively). When asked why providers do not adhere to telemetry guidelines, lack of awareness of and lack of familiarity with the guidelines were the top 2 choices among respondents (Figure 1).

Additionally, most providers acknowledged experiencing adverse effects of telemetry: 86% (57/66) had experienced delayed patient transfers from the emergency department to inpatient floors due to telemetry unavailability and 97% (65/67) had experienced some delay in obtaining tests or studies for their telemetry-monitored patients. Despite acknowledging the potential consequences of telemetry use, only 21% (14/66) of providers routinely (ie, > 75% of the time) discontinued telemetry within 48 hours. Fifteen percent (10/65) routinely allowed telemetry to continue until the time of patient discharge. When discontinued, it was mainly due to the provider’s decision (57%); however, respondents noted that nurses prompted telemetry discontinuation 28% of the time.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies [3–5,9–15], the majority of providers at our institution do not think continuous telemetry is appropriately utilized. Most survey respondents acknowledged a lack of awareness surrounding current guideline recommendations, which could explain why providers often do not follow them. Despite conceding their knowledge deficits, providers assumed their practice patterns for ordering telemetry were “appropriate”(ie, guideline-supported). This assertion may be incorrect as the majority of providers in our survey chose at least 1 non–guideline-supported indication for telemetry. Other studies have suggested additional reasons for inappropriate telemetry utilization. Providers may disagree with guideline recommendations, may assign lesser importance to guidelines when caring for an individual patient, or may fall victim to inertia (ie, not ordering telemetry appropriately simply because changing one’s practice pattern is difficult) [7].

In addition, the majority of our providers perceived telemetry overuse, which has been well-recognized nationwide [4]. While we did not assess this directly, other studies suggest that providers may overuse telemetry to provide a sense of reassurance when caring for a sick patient, since continuous telemetry is perceived to provide a higher level of care [6,15–17]. Unfortunately, no study has shown a benefit for continuous telemetry when placed for non-guideline-based diagnoses—whether for cardiac or non-cardiac diagnoses [3,9–11,13,14]. Likewise, the guidelines suggest that telemetry use should be time-limited, since the majority of benefit is accrued in the first 48 hours. Beyond that time, no study has shown a clear benefit to continuous telemetry [2]. Therefore, telemetry overuse may lead to unnecessarily increased costs without added benefits [3,9–11,13–15,18].

Our conclusions are tempered by the nature of our survey data. We recognize that our survey has not been previously validated. In addition, our response rates were low. This low sample size may lead to under-representation of diverse ideas. Also, our survey results may not be generalizable, since our study was conducted at a single academic hospital. Our institution’s telemetry ordering culture may differ from others, therefore making our results less applicable to other centers.

Despite these limitations, our results aid in understanding attitudes that surround the use of continuous telemetry, which can shape formal educational interventions to encourage appropriate guideline-based telemetry use. Since our providers agree on the need for more education about the guidelines, components such as online modules or in-person lecture educational sessions, newsletters, email communications, and incorporation of AHA guidelines into the institution’s automated computer order entry system could be utilized [17]. Didactic interventions could be designed especially for trainees given their overall lack of familiarity with the guidelines. Another potential intervention could include supplying providers with publically shared personalized measures of their own practices, since providers benefit from reinforcement and individualized feedback on appropriate utilization practices [19]. Previous studies have suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to patient care leads to positive outcomes [20,21], and in our experience, nursing input is absolutely critical in outlining potential problems and in developing solutions. Our findings suggest that nurses could play an active role in alerting providers when patients have telemetry in use and identifying patients who may no longer need it.

In summary, we have shown that many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilized continuous telemetry inappropriately, and were unaware of guidelines surrounding telemetry use. Future interventions aimed at educating providers, encouraging dialogue between staff, and enabling guideline-supported utilization may increase appropriate telemetry use leading to lower cost and improved quality of patient care.

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thank Dr. Colleen Christmas, Dr. Panagis Galiatsatos, Mrs. Barbara Brigade, Ms. Joetta Love, Ms. Terri Rigsby, and Mrs. Lisa Shirk for their invaluable technical and administrative support.

Corresponding author: Amber Johnson, MD, MBA, 200 Lothrop St., S-553 Scaife Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Day H. Preliminary studies of an acute coronary care area. J Lancet 1963;83:53–5.

2. Drew B, Califf R, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110:2721–46.

3. Estrada C, Battilana G, Alexander M, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:51–5.

4. Henriques-Forsythe M, Ivonye C, Jamched U, et al. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med 2009;76:368–72.

5. Chen E, Hollander, J. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007;33:53–60.

6. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1349–50.

7. Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines?: A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65.

8. Adult hospital medicine. Five things physicians and patients should question. 15 Aug 2013. Available at www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/society-of-hospital-medicine-adult-hospital-medicine/

9. Durairaj L, Reilly B, Das K, et al. Emergency department admissions to inpatient cardiac telemetry beds: A prospective cohort study of risk stratification and outcomes. Am J Med 2001;110:7–11.

10. Estrada C, Rosman H, Prasad N, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:960–5.

11. Hollander J, Sites F, Pollack C, Shofer F. Lack of utility of telemetry monitoring for identification of cardiac death and life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias in low-risk patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:71–6.

12. Ivonye C, Ohuabunwo C, Henriques-Forsythe M, et al. Evaluation of telemetry utilization, policy, and outcomes in an inner-city academic medical center. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102:598–604.

13. Schull M, Redelmeier D. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:647–52.

14. Sivaram C, Summers J, Ahmed N. Telemetry outside critical care units: patterns of utilization and influence on management decisions. Clin Cardiol 1998;21:503–5.

15. Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002;122:517–23.

16. Chen S, Zakaria S. Behind the monitor-The trouble with telemetry: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:894.

17. Dressler R, Dryer M, Coletti C, et al. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1852–4.

18. Benjamin E, Klugman R, Luckmann R, et al. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e225–32.

19. Solomon D, Hashimoto H, Daltroy L, Liang M. Techniques to improve physicians use of diagnostic tests: A new conceptual framework. JAMA 1998;280:2020–7.

20. Richeson J, Johnson J. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung 1992;21:18–24.

21. Curley C, McEachern J, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care 1998;36:AS4–12.

From the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Drs. Johnson, Knight, Maygers, and Zakaria), and Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC (Dr. Mock).

Abstract

- Objective: To determine patterns of telemetry use at a tertiary academic institution and identify factors contributing to noncompliance with guidelines regarding telemetry use.

- Methods: Web-based survey of 180 providers, including internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

- Results: Of the 180 providers surveyed, 67 (37%) replied. Most providers (76%) were unaware of guidelines regarding appropriate telemetry use and 85% selected inappropriate diagnoses as warranting telemetry. Only 21% routinely discontinued the telemetry order within 48 hours.

- Conclusions: Many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilize continuous telemetry inappropriately and are unaware of telemetry guidelines. These findings should guide interventions to improve telemetry utilization.

For many decades, telemetry has been widely used in the management and monitoring of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes (ACS), arrhythmias, cardiac events, and strokes [1]. In addition, telemetry has often been used in other clinical scenarios with less rigorous data supporting its use [2–4]. As a result, in 2004 the American Heart Association (AHA) issued guidelines providing recommendations for best practices in hospital ECG monitoring. Indications for telemetry were classified into 3 diagnosis-driven groups: class I (indicated in all patients), class II (indicated in most patients, may be of benefit) and class III (not indicated, no therapeutic benefit) [2]. However, these recommendations have not been widely followed and telemetry is inappropriately used for many inpatients [5,6].

There are several reasons why clinicians fail to adhere to guidelines, including knowledge deficits, attitudes regarding the current guidelines, and institution-specific factors influencing practitioner behaviors [7]. In response to reports of widespread telemetry overuse, the Choosing Wisely Campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has championed judicious telemetry use, advocating evidence-based, protocol-driven telemetry management for patients not in intensive care units who do not meet guideline-based criteria for continuous telemetry [8].

In order to understand patterns of telemetry use at our academic institution and identify factors associated with this practice, we systematically analyzed telemetry use perceptions through provider surveys. We hypothesized that providers have misperceptions about appropriate use of telemetry and that this knowledge gap results in overuse of telemetry at our institution.

Methods

Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center is a 400-bed academic medical center serving southeastern Baltimore. Providers included internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows who rotate to the medical center and Johns Hopkins Hospital, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs).

Current Telemetry Practice

Remote telemetric monitoring is available in all adult, non-intensive care units of the hospital except for the psychiatry unit. However, the number of monitors are limited and it is not possible to monitor every patient if the wards are at capacity. Obstetrics uses its own unique cardiac monitoring system and thus was not included in the survey. Each monitor (IntelliVue, Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands) is attached to the patient using 5 lead wires, with electrocardiographic data transmitted to a monitoring station based in the progressive care unit, a cardio-pulmonary step-down unit. Monitors can be ordered in one of 3 manners, as mandated by hospital policy:

- Continuous telemetry – Telemetry monitoring is uninterrupted until discontinued by a provider.

- Telemetry protocol – Within 12 hours of telemetry placement, a monitor technician generates a report, which is reviewed by the nurse caring for the patient. The nurse performs an electrocardiogram (ECG) if the patient meets pre-specified criteria for telemetry discontinuation, which includes the absence of arrhythmias, troponin elevations, chest pain, or hemodynamic instability. The repeat ECG is then read and signed by the provider. After these criteria are met, telemetry can be discontinued.

- Stroke telemetry protocol – Telemetry is applied for 48 hours, mainly for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Monitoring can be temporarily discontinued if the patient requires magnetic resonance imaging, which interferes with the telemetric monitors.

When entering any of the 3 possible telemetry orders in our computerized provider order entry system (Meditech, Westwood, MA), the ordering provider is required to indicate baseline rhythm, pacemaker presence, and desired heart rate warning parameters. Once the order is electronically signed, a monitor technician notes the order in a logbook and assigns the patient a telemeter, which is applied by the patient’s nurse.

If a monitored patient develops any predefined abnormal rhythm, audible alerts notify monitor technicians and an alert is sent to a portable telephone carried by the patient’s assigned nurse. Either the monitoring technician or the nurse then has the discretion to silence the alarm, note it in the chart, and/or contact the patient’s provider. If alerts are recorded, then a sample telemetry monitoring strip is saved into the patient’s paper medical chart.

Survey Instrument

After approval from the Johns Hopkins institutional review board, we queried providers who worked on the medicine and cardiology wards to assess the context and culture in which telemetry monitoring is used (see Appendix). The study was exempt from requiring informed consent. All staff had the option to decline study participation. We administered the survey using an online survey software program (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA), sending survey links via email to all internal medicine residents, cardiovascular disease fellows, internal medicine and cardiology teaching attending physicians, hospitalists, NPs, and PAs. Respondents completed the survey anonymously. To increase response rates, providers were sent a monthly reminder email. The survey was open from March 2014 to May 2014 for a total of 3 months.

Analysis

The survey data were compiled and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Mac version 14.4; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Variables are displayed as numbers and percentages, as appropriate.

Results

All providers reported having ordered telemetry, but almost all were either unaware of (76%) or only somewhat familiar with (21%) the AHA guidelines for appropriate telemetry use. Notably, the vast majority of fellows and residents reported that they were not at all familiar with the guidelines (100% and 96%, respectively). When asked why providers do not adhere to telemetry guidelines, lack of awareness of and lack of familiarity with the guidelines were the top 2 choices among respondents (Figure 1).

Additionally, most providers acknowledged experiencing adverse effects of telemetry: 86% (57/66) had experienced delayed patient transfers from the emergency department to inpatient floors due to telemetry unavailability and 97% (65/67) had experienced some delay in obtaining tests or studies for their telemetry-monitored patients. Despite acknowledging the potential consequences of telemetry use, only 21% (14/66) of providers routinely (ie, > 75% of the time) discontinued telemetry within 48 hours. Fifteen percent (10/65) routinely allowed telemetry to continue until the time of patient discharge. When discontinued, it was mainly due to the provider’s decision (57%); however, respondents noted that nurses prompted telemetry discontinuation 28% of the time.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies [3–5,9–15], the majority of providers at our institution do not think continuous telemetry is appropriately utilized. Most survey respondents acknowledged a lack of awareness surrounding current guideline recommendations, which could explain why providers often do not follow them. Despite conceding their knowledge deficits, providers assumed their practice patterns for ordering telemetry were “appropriate”(ie, guideline-supported). This assertion may be incorrect as the majority of providers in our survey chose at least 1 non–guideline-supported indication for telemetry. Other studies have suggested additional reasons for inappropriate telemetry utilization. Providers may disagree with guideline recommendations, may assign lesser importance to guidelines when caring for an individual patient, or may fall victim to inertia (ie, not ordering telemetry appropriately simply because changing one’s practice pattern is difficult) [7].

In addition, the majority of our providers perceived telemetry overuse, which has been well-recognized nationwide [4]. While we did not assess this directly, other studies suggest that providers may overuse telemetry to provide a sense of reassurance when caring for a sick patient, since continuous telemetry is perceived to provide a higher level of care [6,15–17]. Unfortunately, no study has shown a benefit for continuous telemetry when placed for non-guideline-based diagnoses—whether for cardiac or non-cardiac diagnoses [3,9–11,13,14]. Likewise, the guidelines suggest that telemetry use should be time-limited, since the majority of benefit is accrued in the first 48 hours. Beyond that time, no study has shown a clear benefit to continuous telemetry [2]. Therefore, telemetry overuse may lead to unnecessarily increased costs without added benefits [3,9–11,13–15,18].

Our conclusions are tempered by the nature of our survey data. We recognize that our survey has not been previously validated. In addition, our response rates were low. This low sample size may lead to under-representation of diverse ideas. Also, our survey results may not be generalizable, since our study was conducted at a single academic hospital. Our institution’s telemetry ordering culture may differ from others, therefore making our results less applicable to other centers.

Despite these limitations, our results aid in understanding attitudes that surround the use of continuous telemetry, which can shape formal educational interventions to encourage appropriate guideline-based telemetry use. Since our providers agree on the need for more education about the guidelines, components such as online modules or in-person lecture educational sessions, newsletters, email communications, and incorporation of AHA guidelines into the institution’s automated computer order entry system could be utilized [17]. Didactic interventions could be designed especially for trainees given their overall lack of familiarity with the guidelines. Another potential intervention could include supplying providers with publically shared personalized measures of their own practices, since providers benefit from reinforcement and individualized feedback on appropriate utilization practices [19]. Previous studies have suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to patient care leads to positive outcomes [20,21], and in our experience, nursing input is absolutely critical in outlining potential problems and in developing solutions. Our findings suggest that nurses could play an active role in alerting providers when patients have telemetry in use and identifying patients who may no longer need it.

In summary, we have shown that many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilized continuous telemetry inappropriately, and were unaware of guidelines surrounding telemetry use. Future interventions aimed at educating providers, encouraging dialogue between staff, and enabling guideline-supported utilization may increase appropriate telemetry use leading to lower cost and improved quality of patient care.

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thank Dr. Colleen Christmas, Dr. Panagis Galiatsatos, Mrs. Barbara Brigade, Ms. Joetta Love, Ms. Terri Rigsby, and Mrs. Lisa Shirk for their invaluable technical and administrative support.

Corresponding author: Amber Johnson, MD, MBA, 200 Lothrop St., S-553 Scaife Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Drs. Johnson, Knight, Maygers, and Zakaria), and Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC (Dr. Mock).

Abstract

- Objective: To determine patterns of telemetry use at a tertiary academic institution and identify factors contributing to noncompliance with guidelines regarding telemetry use.

- Methods: Web-based survey of 180 providers, including internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

- Results: Of the 180 providers surveyed, 67 (37%) replied. Most providers (76%) were unaware of guidelines regarding appropriate telemetry use and 85% selected inappropriate diagnoses as warranting telemetry. Only 21% routinely discontinued the telemetry order within 48 hours.

- Conclusions: Many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilize continuous telemetry inappropriately and are unaware of telemetry guidelines. These findings should guide interventions to improve telemetry utilization.

For many decades, telemetry has been widely used in the management and monitoring of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes (ACS), arrhythmias, cardiac events, and strokes [1]. In addition, telemetry has often been used in other clinical scenarios with less rigorous data supporting its use [2–4]. As a result, in 2004 the American Heart Association (AHA) issued guidelines providing recommendations for best practices in hospital ECG monitoring. Indications for telemetry were classified into 3 diagnosis-driven groups: class I (indicated in all patients), class II (indicated in most patients, may be of benefit) and class III (not indicated, no therapeutic benefit) [2]. However, these recommendations have not been widely followed and telemetry is inappropriately used for many inpatients [5,6].

There are several reasons why clinicians fail to adhere to guidelines, including knowledge deficits, attitudes regarding the current guidelines, and institution-specific factors influencing practitioner behaviors [7]. In response to reports of widespread telemetry overuse, the Choosing Wisely Campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has championed judicious telemetry use, advocating evidence-based, protocol-driven telemetry management for patients not in intensive care units who do not meet guideline-based criteria for continuous telemetry [8].

In order to understand patterns of telemetry use at our academic institution and identify factors associated with this practice, we systematically analyzed telemetry use perceptions through provider surveys. We hypothesized that providers have misperceptions about appropriate use of telemetry and that this knowledge gap results in overuse of telemetry at our institution.

Methods

Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center is a 400-bed academic medical center serving southeastern Baltimore. Providers included internal medicine residents and cardiovascular disease fellows who rotate to the medical center and Johns Hopkins Hospital, hospitalists, non-hospitalist teaching attending physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs).

Current Telemetry Practice

Remote telemetric monitoring is available in all adult, non-intensive care units of the hospital except for the psychiatry unit. However, the number of monitors are limited and it is not possible to monitor every patient if the wards are at capacity. Obstetrics uses its own unique cardiac monitoring system and thus was not included in the survey. Each monitor (IntelliVue, Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands) is attached to the patient using 5 lead wires, with electrocardiographic data transmitted to a monitoring station based in the progressive care unit, a cardio-pulmonary step-down unit. Monitors can be ordered in one of 3 manners, as mandated by hospital policy:

- Continuous telemetry – Telemetry monitoring is uninterrupted until discontinued by a provider.

- Telemetry protocol – Within 12 hours of telemetry placement, a monitor technician generates a report, which is reviewed by the nurse caring for the patient. The nurse performs an electrocardiogram (ECG) if the patient meets pre-specified criteria for telemetry discontinuation, which includes the absence of arrhythmias, troponin elevations, chest pain, or hemodynamic instability. The repeat ECG is then read and signed by the provider. After these criteria are met, telemetry can be discontinued.

- Stroke telemetry protocol – Telemetry is applied for 48 hours, mainly for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Monitoring can be temporarily discontinued if the patient requires magnetic resonance imaging, which interferes with the telemetric monitors.

When entering any of the 3 possible telemetry orders in our computerized provider order entry system (Meditech, Westwood, MA), the ordering provider is required to indicate baseline rhythm, pacemaker presence, and desired heart rate warning parameters. Once the order is electronically signed, a monitor technician notes the order in a logbook and assigns the patient a telemeter, which is applied by the patient’s nurse.

If a monitored patient develops any predefined abnormal rhythm, audible alerts notify monitor technicians and an alert is sent to a portable telephone carried by the patient’s assigned nurse. Either the monitoring technician or the nurse then has the discretion to silence the alarm, note it in the chart, and/or contact the patient’s provider. If alerts are recorded, then a sample telemetry monitoring strip is saved into the patient’s paper medical chart.

Survey Instrument

After approval from the Johns Hopkins institutional review board, we queried providers who worked on the medicine and cardiology wards to assess the context and culture in which telemetry monitoring is used (see Appendix). The study was exempt from requiring informed consent. All staff had the option to decline study participation. We administered the survey using an online survey software program (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA), sending survey links via email to all internal medicine residents, cardiovascular disease fellows, internal medicine and cardiology teaching attending physicians, hospitalists, NPs, and PAs. Respondents completed the survey anonymously. To increase response rates, providers were sent a monthly reminder email. The survey was open from March 2014 to May 2014 for a total of 3 months.

Analysis

The survey data were compiled and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Mac version 14.4; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Variables are displayed as numbers and percentages, as appropriate.

Results

All providers reported having ordered telemetry, but almost all were either unaware of (76%) or only somewhat familiar with (21%) the AHA guidelines for appropriate telemetry use. Notably, the vast majority of fellows and residents reported that they were not at all familiar with the guidelines (100% and 96%, respectively). When asked why providers do not adhere to telemetry guidelines, lack of awareness of and lack of familiarity with the guidelines were the top 2 choices among respondents (Figure 1).

Additionally, most providers acknowledged experiencing adverse effects of telemetry: 86% (57/66) had experienced delayed patient transfers from the emergency department to inpatient floors due to telemetry unavailability and 97% (65/67) had experienced some delay in obtaining tests or studies for their telemetry-monitored patients. Despite acknowledging the potential consequences of telemetry use, only 21% (14/66) of providers routinely (ie, > 75% of the time) discontinued telemetry within 48 hours. Fifteen percent (10/65) routinely allowed telemetry to continue until the time of patient discharge. When discontinued, it was mainly due to the provider’s decision (57%); however, respondents noted that nurses prompted telemetry discontinuation 28% of the time.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies [3–5,9–15], the majority of providers at our institution do not think continuous telemetry is appropriately utilized. Most survey respondents acknowledged a lack of awareness surrounding current guideline recommendations, which could explain why providers often do not follow them. Despite conceding their knowledge deficits, providers assumed their practice patterns for ordering telemetry were “appropriate”(ie, guideline-supported). This assertion may be incorrect as the majority of providers in our survey chose at least 1 non–guideline-supported indication for telemetry. Other studies have suggested additional reasons for inappropriate telemetry utilization. Providers may disagree with guideline recommendations, may assign lesser importance to guidelines when caring for an individual patient, or may fall victim to inertia (ie, not ordering telemetry appropriately simply because changing one’s practice pattern is difficult) [7].

In addition, the majority of our providers perceived telemetry overuse, which has been well-recognized nationwide [4]. While we did not assess this directly, other studies suggest that providers may overuse telemetry to provide a sense of reassurance when caring for a sick patient, since continuous telemetry is perceived to provide a higher level of care [6,15–17]. Unfortunately, no study has shown a benefit for continuous telemetry when placed for non-guideline-based diagnoses—whether for cardiac or non-cardiac diagnoses [3,9–11,13,14]. Likewise, the guidelines suggest that telemetry use should be time-limited, since the majority of benefit is accrued in the first 48 hours. Beyond that time, no study has shown a clear benefit to continuous telemetry [2]. Therefore, telemetry overuse may lead to unnecessarily increased costs without added benefits [3,9–11,13–15,18].

Our conclusions are tempered by the nature of our survey data. We recognize that our survey has not been previously validated. In addition, our response rates were low. This low sample size may lead to under-representation of diverse ideas. Also, our survey results may not be generalizable, since our study was conducted at a single academic hospital. Our institution’s telemetry ordering culture may differ from others, therefore making our results less applicable to other centers.

Despite these limitations, our results aid in understanding attitudes that surround the use of continuous telemetry, which can shape formal educational interventions to encourage appropriate guideline-based telemetry use. Since our providers agree on the need for more education about the guidelines, components such as online modules or in-person lecture educational sessions, newsletters, email communications, and incorporation of AHA guidelines into the institution’s automated computer order entry system could be utilized [17]. Didactic interventions could be designed especially for trainees given their overall lack of familiarity with the guidelines. Another potential intervention could include supplying providers with publically shared personalized measures of their own practices, since providers benefit from reinforcement and individualized feedback on appropriate utilization practices [19]. Previous studies have suggested that a multidisciplinary approach to patient care leads to positive outcomes [20,21], and in our experience, nursing input is absolutely critical in outlining potential problems and in developing solutions. Our findings suggest that nurses could play an active role in alerting providers when patients have telemetry in use and identifying patients who may no longer need it.

In summary, we have shown that many providers at a tertiary academic institution utilized continuous telemetry inappropriately, and were unaware of guidelines surrounding telemetry use. Future interventions aimed at educating providers, encouraging dialogue between staff, and enabling guideline-supported utilization may increase appropriate telemetry use leading to lower cost and improved quality of patient care.

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thank Dr. Colleen Christmas, Dr. Panagis Galiatsatos, Mrs. Barbara Brigade, Ms. Joetta Love, Ms. Terri Rigsby, and Mrs. Lisa Shirk for their invaluable technical and administrative support.

Corresponding author: Amber Johnson, MD, MBA, 200 Lothrop St., S-553 Scaife Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Day H. Preliminary studies of an acute coronary care area. J Lancet 1963;83:53–5.

2. Drew B, Califf R, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110:2721–46.

3. Estrada C, Battilana G, Alexander M, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:51–5.

4. Henriques-Forsythe M, Ivonye C, Jamched U, et al. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med 2009;76:368–72.

5. Chen E, Hollander, J. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007;33:53–60.

6. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1349–50.

7. Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines?: A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65.

8. Adult hospital medicine. Five things physicians and patients should question. 15 Aug 2013. Available at www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/society-of-hospital-medicine-adult-hospital-medicine/

9. Durairaj L, Reilly B, Das K, et al. Emergency department admissions to inpatient cardiac telemetry beds: A prospective cohort study of risk stratification and outcomes. Am J Med 2001;110:7–11.

10. Estrada C, Rosman H, Prasad N, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:960–5.

11. Hollander J, Sites F, Pollack C, Shofer F. Lack of utility of telemetry monitoring for identification of cardiac death and life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias in low-risk patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:71–6.

12. Ivonye C, Ohuabunwo C, Henriques-Forsythe M, et al. Evaluation of telemetry utilization, policy, and outcomes in an inner-city academic medical center. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102:598–604.

13. Schull M, Redelmeier D. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:647–52.

14. Sivaram C, Summers J, Ahmed N. Telemetry outside critical care units: patterns of utilization and influence on management decisions. Clin Cardiol 1998;21:503–5.

15. Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002;122:517–23.

16. Chen S, Zakaria S. Behind the monitor-The trouble with telemetry: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:894.

17. Dressler R, Dryer M, Coletti C, et al. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1852–4.

18. Benjamin E, Klugman R, Luckmann R, et al. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e225–32.

19. Solomon D, Hashimoto H, Daltroy L, Liang M. Techniques to improve physicians use of diagnostic tests: A new conceptual framework. JAMA 1998;280:2020–7.

20. Richeson J, Johnson J. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung 1992;21:18–24.

21. Curley C, McEachern J, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care 1998;36:AS4–12.

1. Day H. Preliminary studies of an acute coronary care area. J Lancet 1963;83:53–5.

2. Drew B, Califf R, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: Endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110:2721–46.

3. Estrada C, Battilana G, Alexander M, et al. Evaluation of guidelines for the use of telemetry in the non-intensive-care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:51–5.

4. Henriques-Forsythe M, Ivonye C, Jamched U, et al. Is telemetry overused? Is it as helpful as thought? Cleve Clin J Med 2009;76:368–72.

5. Chen E, Hollander, J. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007;33:53–60.

6. Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1349–50.

7. Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines?: A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65.

8. Adult hospital medicine. Five things physicians and patients should question. 15 Aug 2013. Available at www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/society-of-hospital-medicine-adult-hospital-medicine/

9. Durairaj L, Reilly B, Das K, et al. Emergency department admissions to inpatient cardiac telemetry beds: A prospective cohort study of risk stratification and outcomes. Am J Med 2001;110:7–11.

10. Estrada C, Rosman H, Prasad N, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:960–5.

11. Hollander J, Sites F, Pollack C, Shofer F. Lack of utility of telemetry monitoring for identification of cardiac death and life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias in low-risk patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:71–6.

12. Ivonye C, Ohuabunwo C, Henriques-Forsythe M, et al. Evaluation of telemetry utilization, policy, and outcomes in an inner-city academic medical center. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102:598–604.

13. Schull M, Redelmeier D. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:647–52.

14. Sivaram C, Summers J, Ahmed N. Telemetry outside critical care units: patterns of utilization and influence on management decisions. Clin Cardiol 1998;21:503–5.

15. Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002;122:517–23.

16. Chen S, Zakaria S. Behind the monitor-The trouble with telemetry: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:894.

17. Dressler R, Dryer M, Coletti C, et al. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1852–4.

18. Benjamin E, Klugman R, Luckmann R, et al. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:e225–32.

19. Solomon D, Hashimoto H, Daltroy L, Liang M. Techniques to improve physicians use of diagnostic tests: A new conceptual framework. JAMA 1998;280:2020–7.

20. Richeson J, Johnson J. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung 1992;21:18–24.

21. Curley C, McEachern J, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care 1998;36:AS4–12.

Medication Warnings for Adults

Many computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems suffer from having too much of a good thing. Few would question the beneficial effect of CPOE on medication order clarity, completeness, and transmission.[1, 2] When mechanisms for basic decision support have been added, however, such as allergy, interaction, and duplicate warnings, reductions in medication errors and adverse events have not been consistently achieved.[3, 4, 5, 6, 7] This is likely due in part to the fact that ordering providers override medication warnings at staggeringly high rates.[8, 9] Clinicians acknowledge that they are ignoring potentially valuable warnings,[10, 11] but suffer from alert fatigue due to the sheer number of messages, many of them judged by clinicians to be of low‐value.[11, 12]

Redesign of medication alert systems to increase their signal‐to‐noise ratio is badly needed,[13, 14, 15, 16] and will need to consider the clinical significance of alerts, their presentation, and context‐specific factors that potentially contribute to warning effectiveness.[17, 18, 19] Relatively few studies, however, have objectively looked at context factors such as the characteristics of providers, patients, medications, and warnings that are associated with provider responses to warnings,[9, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] and only 2 have studied how warning acceptance is associated with medication risk.[18, 26] We wished to explore these factors further. Warning acceptance has been shown to be higher, at least in the outpatient setting, when orders are entered by low‐volume prescribers for infrequently encountered warnings,[24] and there is some evidence that patients receive higher‐quality care during the day.[27] Significant attention has been placed in recent years on inappropriate prescribing in older patients,[28] and on creating a culture of safety in healthcare.[29] We therefore hypothesized that our providers would be more cautious, and medication warning acceptance rates would be higher, when orders were entered for patients who were older or with more complex medical problems, when they were entered during the day by caregivers who entered few orders, when the medications ordered were potentially associated with greater risk, and when the warnings themselves were infrequently encountered.

METHODS

Setting and Caregivers

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC) is a 400‐bed academic medical center serving southeastern Baltimore, Maryland. Prescribing caregivers include residents and fellows who rotate to both JHBMC and Johns Hopkins Hospital, internal medicine hospitalists, other attending physicians (including teaching attendings for all departments, and hospitalists and clinical associates for departments other than internal medicine), and nurse practitioners and physician assistants from most JHBMC departments. Nearly 100% of patients on the surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, neurology, psychiatry, and chemical dependence services are hospitalized on units dedicated to their respective specialty, and the same is true for approximately 95% of medicine patients.

Order Entry

JHBMC began using a client‐server order entry system by MEDITECH (Westwood, MA) in July 2003. Provider order entry was phased in beginning in October 2003 and completed by the end of 2004. MEDITECH version 5.64 was being used during the study period. Medications may generate duplicate, interaction, allergy, adverse reaction, and dose warnings during a patient ordering session each time they are ordered. Duplicate warnings are generated when the same medication (no matter what route) is ordered that is either on their active medication list, was on the list in the preceding 24 hours, or that is being ordered simultaneously. A drug‐interaction database licensed from First DataBank (South San Francisco, CA) is utilized, and updated monthly, which classifies potential drug‐drug interactions as contraindicated, severe, intermediate, and mild. Those classified as contraindicated by First DataBank are included in the severe category in MEDITECH 5.64. During the study period, JHBMC's version of MEDITECH was configured so that providers were warned of potential severe and intermediate drug‐drug interactions, but not mild. No other customizations had been made. Patients' histories of allergies and other adverse responses to medications can be entered by any credentialed staff member. They are maintained together in an allergies section of the electronic medical record, but are identified as either allergy or adverse reactions at the time they are entered, and each generates its own warnings.

When more than 1 duplicate, interaction, allergy, or adverse reaction warning is generated for a particular medication, all appear listed on a single screen in identical fonts. No visual distinction is made between severe and intermediate drug‐drug interactions; for these, the category of medication ordered is followed by the category of the medication for which there is a potential interaction. A details button can be selected to learn specifically which medications are involved and the severity and nature of the potential interactions identified. In response to the warnings, providers can choose to either override them, erase the order, or replace the order by clicking 1 of 3 buttons at the bottom of the screen. Warnings are not repeated unless the medication is reordered for that patient. Dose warnings appear on a subsequent screen and are not addressed in this article.

Nurses are discouraged from entering verbal orders but do have the capacity to do so, at which time they encounter and must respond to the standard medication warnings, if any. Medical students are able to enter orders, at which time they also encounter and must respond to the standard medication warnings; their orders must then be cosigned by a licensed provider before they can be processed. Warnings encountered by nurses and medical students are not repeated at the time of cosignature by a licensed provider.

Data Collection

We collected data regarding all medication orders placed in our CPOE system from October 1, 2009 to April 20, 2010 for all adult patients. Intensive care unit (ICU) patients were excluded, in anticipation of a separate analysis. Hospitalizations under observation were also excluded. We then ran a report showing all medications that generated any number of warnings of any type (duplicate, interaction, allergy, or adverse reaction) for the same population. Warnings generated during readmissions that occurred at any point during the study period (ranging from 1 to 21 times) were excluded, because these patients likely had many, if not all, of the same medications ordered during their readmissions as during their initial hospitalization, which would unduly influence the analysis if retained.

There was wide variation in the number of warnings generated per medication and in the number of each warning type per medication that generated multiple warnings. Therefore, for ease of analysis and to ensure that we could accurately determine varying response to each individual warning type, we thereafter focused on the medications that generated single warnings during the study period. For each single warning we obtained patient name, account number, event date and time, hospital unit at the time of the event, ordered medication, ordering staff member, warning type, and staff member response to the warning (eg, override warning or erase order [accept the warning]). The response replace was used very infrequently, and therefore warnings that resulted in this response were excluded. Medications available in more than 1 form included the route of administration in their name, and from this they were categorized as parenteral or nonparenteral. All nonparenteral or parenteral forms of a given medication were grouped together as 1 medication (eg, morphine sustained release and morphine elixir were classified as a single‐medication, nonparenteral morphine). Medications were further categorized according to whether or not they were on the Institute for Safe Medication Practice (ISMP) List of High‐Alert Medications.[30]

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

We collected descriptive data about patients and providers. Age and length of stay (LOS) at the time of the event were determined based on the patients' admit date and date of birth, and grouped into quartiles. Hospital units were grouped according to which service or services they primarily served. Medications were grouped into quartiles according to the total number of warnings they generated during the study period. Warnings were dichotomously categorized according to whether they were overridden or accepted. Unpaired t tests were used to compare continuous variables for the 2 groups, and [2] tests were used to compare categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression was then performed, using variables with a P value of <0.10 in the univariate analysis, to control for confounders and identify independent predictors of medication warning acceptance. All analyses were performed using Intercooled Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 259,656 medication orders were placed for adult non‐ICU patients during the 7‐month study period. Of those orders, 45,835 generated some number of medication warnings.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20] The median number of warnings per patient was 4 (interquartile range [IQR]=28; mean=5.9, standard deviation [SD]=6.2), with a range from 1 to 84. The median number of warnings generated per provider during the study period was 36 (IQR=6106, mean=87.4, SD=133.7), with a range of 1 to 1096.

There were 40,391 orders placed for 454 medications for adult non‐ICU patients, which generated a single‐medication warning (excluding those with the response replace, which was used 20 times) during the 7‐month study period. Data regarding the patients and providers associated with the orders generating single warnings are shown in Table 1. Most patients were on medicine units, and most orders were entered by residents. Patients' LOS at the time the orders were placed ranged from 0 to 118 days (median=1, IQR=04; mean=4.0, SD=7.2). The median number of single warnings per patient was 4 (IQR=28; mean=6.1, SD=6.5), with a range from 1 to 84. The median number of single warnings generated per provider during the study period was 15 (IQR=373; mean=61.7, SD=109.6), with a range of 1 to 1057.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patients (N=6,646) | |

| Age | |

| 1545 years | 2,048 (31%) |

| 4657 years | 1,610 (24%) |

| 5872 years | 1,520 (23%) |

| 73104 years | 1,468 (22%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 2,934 (44%) |

| Hospital unita | |

| Medicine | 2,992 (45%) |

| Surgery | 1,836 (28%) |

| Neuro/psych/chem dep | 1,337 (20%) |

| OB/GYN | 481 (7%) |

| Caregivers (N=655) | |

| Resident | 248 (38%)b |

| Nurse | 154 (24%) |

| Attending or other | 97 (15%) |

| NP/PA | 69 (11%) |

| IM hospitalist | 31 (5%) |

| Fellow | 27 (4%) |

| Medical student | 23 (4%) |

| Pharmacist | 6 (1%) |

Patient and caregiver characteristics for the medication orders that generated single warnings are shown in Table 2. The majority of medications were nonparenteral and not on the ISMP list (Table 3). Most warnings generated were either duplicate (47%) or interaction warnings (47%). Warnings of a particular type were repeated 14.5% of the time for a particular medication and patient (from 2 to 24 times, median=2, IQR=22, mean=2.7, SD=1.4), and 9.8% of the time for a particular caregiver, medication, and patient (from 2 to 18 times, median=2, IQR=22, mean=2.4, SD=1.1).

| Variable | No. of Warnings (%)a | No. of Warnings Accepted (%)a | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Patient age | |||

| 1545 years | 10,881 (27) | 602 (5.5%) | <0.001 |

| 4657 years | 9,733 (24) | 382 (3.9%) | |

| 5872 years | 10,000 (25) | 308 (3.1%) | |

| 73104 years | 9,777 (24) | 262 (2.7%) | |

| Patient gender | |||

| Female | 23,395 (58) | 866 (3.7%) | 0.074 |

| Male | 16,996 (42) | 688 (4.1%) | |

| Patient length of stay | |||

| <1 day | 10,721 (27) | 660 (6.2%) | <0.001 |

| 1 day | 10,854 (27) | 385 (3.5%) | |

| 24 days | 10,424 (26) | 277 (2.7%) | |

| 5118 days | 8,392 (21) | 232 (2.8%) | |

| Patient hospital unit | |||

| Medicine | 20,057 (50) | 519 (2.6%) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 10,274 (25) | 477 (4.6%) | |

| Neuro/psych/chem dep | 8,279 (21) | 417 (5.0%) | |

| OB/GYN | 1,781 (4) | 141 (7.9%) | |

| Ordering caregiver | |||

| Resident | 22,523 (56) | 700 (3.1%) | <0.001 |

| NP/PA | 7,534 (19) | 369 (4.9%) | |

| IM hospitalist | 5,048 (13) | 155 (3.1%) | |

| Attending | 3225 (8) | 219 (6.8%) | |

| Fellow | 910 (2) | 34 (3.7%) | |

| Nurse | 865 (2) | 58 (6.7%) | |

| Medical student | 265 (<1) | 17 (6.4%) | |

| Pharmacist | 21 (<1) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| Day ordered | |||

| Weekday | 31,499 (78%) | 1276 (4.1%) | <0.001 |

| Weekend | 8,892 (22%) | 278 (3.1%) | |

| Time ordered | |||

| 00000559 | 4,231 (11%) | 117 (2.8%) | <0.001 |

| 06001159 | 11,696 (29%) | 348 (3.0%) | |

| 12001759 | 15,879 (39%) | 722 (4.6%) | |

| 18002359 | 8,585 (21%) | 367 (4.3%) | |

| Administration route (no. of meds) | |||

| Nonparenteral (339) | 27,086 (67%) | 956 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| Parenteral (115) | 13,305 (33%) | 598 (4.5%) | |

| ISMP List of High‐Alert Medications status (no. of meds)[30] | |||

| Not on ISMP list (394) | 27,503 (68%) | 1251 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| On ISMP list (60) | 12,888 (32%) | 303 (2.4%) | |

| No. of warnings per med (no. of meds) | |||

| 11062133 (7) | 9,869 (24%) | 191 (1.9%) | <0.001 |

| 4681034 (13) | 10,014 (25%) | 331 (3.3%) | |

| 170444 (40) | 10,182 (25%) | 314 (3.1%) | |

| 1169 (394) | 10,326 (26%) | 718 (7.0%) | |

| Warning type (no. of meds)b | |||

| Duplicate (369) | 19,083 (47%) | 1041 (5.5%) | <0.001 |

| Interaction (315) | 18,894 (47%) | 254 (1.3%) | |

| Allergy (138) | 2,371 (6%) | 243 (10.0%) | |

| Adverse reaction (14) | 43 (0.1%) | 16 (37%) | |

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patient age | ||

| 1545 years | 1.00 | Reference |

| 4657 years | 0.89 | 0.771.02 |

| 5872 years | 0.85 | 0.730.99 |

| 73104 years | 0.91 | 0.771.08 |

| Patient gender | ||

| Female | 1.00 | Reference |

| Male | 1.26 | 1.131.41 |

| Patient length of stay | ||

| <1 day | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1 day | 0.65 | 0.550.76 |

| 24 days | 0.49 | 0.420.58 |

| 5118 days | 0.49 | 0.410.58 |

| Patient hospital unit | ||

| Medicine | 1.00 | Reference |

| Surgery | 1.45 | 1.251.68 |

| Neuro/psych/chem dep | 1.35 | 1.151.58 |

| OB/GYN | 2.43 | 1.923.08 |

| Ordering caregiver | ||

| Resident | 1.00 | Reference |

| NP/PA | 1.63 | 1.421.88 |

| IM hospitalist | 1.24 | 1.021.50 |

| Attending | 1.83 | 1.542.18 |

| Fellow | 1.41 | 0.982.03 |

| Nurse | 1.92 | 1.442.57 |

| Medical student | 1.17 | 0.701.95 |

| Pharmacist | 3.08 | 0.6714.03 |

| Medication factors | ||

| Nonparenteral | 1.00 | Reference |

| Parenteral | 1.79 | 1.592.03 |

| HighAlert Medication status (no. of meds)[30] | ||

| Not on ISMP list | 1.00 | Reference |

| On ISMP list | 0.37 | 0.320.43 |

| No. of warnings per medication | ||

| 11062133 | 1.00 | Reference |

| 4681034 | 2.30 | 1.902.79 |

| 170444 | 2.25 | 1.852.73 |

| 1169 | 4.10 | 3.424.92 |

| Warning type | ||

| Duplicate | 1.00 | Reference |

| Interaction | 0.24 | 0.210.28 |

| Allergy | 2.28 | 1.942.68 |

| Adverse reaction | 9.24 | 4.5218.90 |

One thousand five hundred fifty‐four warnings were erased (ie, accepted by clinicians [4%]). In univariate analysis, only patient gender was not associated with warning acceptance. Patient age, LOS, hospital unit at the time of order entry, ordering caregiver type, day and time the medication was ordered, administration route, presence on the ISMP list, warning frequency, and warning type were all significantly associated with warning acceptance (Table 2).

Older patient age, longer LOS, presence of the medication on the ISMP list, and interaction warning type were all negatively associated with warning acceptance in multivariable analysis. Warning acceptance was positively associated with male patient gender, being on a service other than medicine, being a caregiver other than a resident, parenteral medications, lower warning frequency, and allergy or adverse reaction warning types (Table 3).

The 20 medications that generated the most single warnings are shown in Table 4. Medications on the ISMP list accounted for 8 of these top 20 medications. For most of them, duplicate and interaction warnings accounted for most of the warnings generated, except for parenteral hydromorphone, oral oxycodone, parenteral morphine, and oral hydromorphone, which each had more allergy than interaction warnings.

| Medication | ISMP Listb | No. of Warnings | Duplicate, No. (%)c | Interaction, No. (%)c | Allergy, No. (%)c | Adverse Reaction, No. (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Hydromorphone injectable | Yes | 2,133 | 1,584 (74.3) | 127 (6.0) | 422 (19.8) | |

| Metoprolol | 1,432 | 550 (38.4) | 870 (60.8) | 12 (0.8) | ||

| Aspirin | 1,375 | 212 (15.4) | 1,096 (79.7) | 67 (4.9) | ||

| Oxycodone | Yes | 1,360 | 987 (72.6) | 364 (26.8) | 9 (0.7) | |

| Potassium chloride | 1,296 | 379 (29.2) | 917 (70.8) | |||

| Ondansetron injectable | 1,167 | 1,013 (86.8) | 153 (13.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Aspart insulin injectable | Yes | 1,106 | 643 (58.1) | 463 (41.9) | ||

| Warfarin | Yes | 1,034 | 298 (28.8) | 736 (71.2) | ||

| Heparin injectable | Yes | 1,030 | 205 (19.9) | 816 (79.2) | 9 (0.3) | |

| Furosemide injectable | 980 | 438 (45.0) | 542 (55.3) | |||

| Lisinopril | 926 | 225 (24.3) | 698 (75.4) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| Acetaminophen | 860 | 686 (79.8) | 118 (13.7) | 54 (6.3) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Morphine injectable | Yes | 804 | 467 (58.1) | 100 (12.4) | 233 (29.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Diazepam | 786 | 731 (93.0) | 41 (5.2) | 14 (1.8) | ||

| Glargine insulin injectable | Yes | 746 | 268 (35.9) | 478 (64.1) | ||

| Ibuprofen | 713 | 125 (17.5) | 529 (74.2) | 54 (7.6) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Hydromorphone | Yes | 594 | 372 (62.6) | 31 (5.2) | 187 (31.5) | 4 (0.7) |

| Furosemide | 586 | 273 (46.6) | 312 (53.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Ketorolac injectable | 487 | 39 (8.0) | 423 (86.9) | 23 (4.7) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Prednisone | 468 | 166 (35.5) | 297 (63.5) | 5 (1.1) | ||

DISCUSSION

Medication warnings in our study were frequently overridden, particularly when encountered by residents, for patients with a long LOS and on the internal medicine service, and for medications generating the most warnings and on the ISMP list. Disturbingly, this means that potentially important warnings for medications with the highest potential for causing harm, for possibly the sickest and most complex patients, were those that were most often ignored by young physicians in training who should have had the most to gain from them. Of course, this is not entirely surprising. Despite our hope that a culture of safety would influence young physicians' actions when caring for these patients and prescribing these medications, these patients and medications are those for whom the most warnings are generated, and these physicians are the ones entering the most orders. Only 13% of the medications studied were on the ISMP list, but they generated 32% of the warnings. We controlled for number of warnings and ISMP list status, but not for warning validity. Most likely, high‐risk medications have been set up with more warnings, many of them of lower quality, in an errant but well‐intentioned effort to make them safer. If developers of CPOE systems want to gain serious traction in using decision support to promote prescribing safe medications, they must take substantial action to increase attention to important warnings and decrease the number of clinically insignificant, low‐value warnings encountered by active caregivers on a daily basis.

Only 2 prior studies, both by Seidling et al., have specifically looked at provider response to warnings for high risk medications. Interaction warnings were rarely accepted in 1,[18] as in our study; however, in contrast to our findings, warning acceptance in both studies was higher for drugs with dose‐dependent toxicity.[18, 26] The effect of physician experience on warning acceptance has been addressed in 2 prior studies. In Weingart et al., residents were more likely than staff physicians to erase medication orders when presented with allergy and interaction warnings in a primary care setting.[20] Long et al. found that physicians younger than 40 years were less likely than older physicians to accept duplicate warnings, but those who had been at the study hospital for a longer period of time were more likely to accept them.[23] The influence of patient LOS and service on warning acceptance has not previously been described. Further study is needed looking at each of these factors.

Individual hospitals tend to avoid making modifications to order entry warning systems, because monitoring and maintaining these changes is labor intensive. Some institutions may make the decision to turn off certain categories of alerts, such as intermediate interaction warnings, to minimize the noise their providers encounter. There are even tools for disabling individual alerts or groups of alerts, such as that available for purchase from our interaction database vendor.[31] However, institutions may fear litigation should an adverse event be attributed to a disabled warning.[15, 16] Clearly, a comprehensive, health system‐wide approach is warranted.[13, 15] To date, published efforts describing ways to improve the effectiveness of medication warning systems have focused on either heightening the clinical significance of alerts[14, 21, 22, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36] or altering their presentation and how providers experience them.[21, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43] The single medication warnings our providers receive are all presented in an identical font, and presumably response to each would be different if they were better distinguished from each other. We also found that a small but significant number of warnings were repeated for a given patient and even a given provider. If the providers knew they would only be presented with warnings the first time they occurred for a given patient and medication, they might be more attuned to the remaining warnings. Previous studies describe context‐specific decision support for medication ordering[44, 45, 46]; however, only 1 has described the use of patient context factors to modify when or how warnings are presented to providers.[47] None have described tailoring allergy, duplicate, and interaction warnings according to medication or provider types. If further study confirms our findings, modulating basic warning systems according to severity of illness, provider experience, and medication risk could powerfully increase their effectiveness. Of course, this would be extremely challenging to achieve, and is likely outside the capabilities of most, if not all, CPOE systems, at least for now.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was limited to medications that generated a single warning. We did this for ease of analysis and so that we could ensure understanding of provider response to each warning type without bias from simultaneously occurring warnings; however, caregiver response to multiple warnings appearing simultaneously for a particular medication order might be quite different. Second, we did not include any assessment of the number of medications ordered by each provider type or for each patient, either of which could significantly affect provider response to warnings. Third, as previously noted, we did not include any assessment of the validity of the warnings, beyond the 4 main categories described, which could also significantly affect provider response. However, it should be noted that although the validity of interaction warnings varies significantly from 1 medication to another, the validity of duplicate, allergy, and adverse reaction warnings in the described system are essentially the same for all medications. Fourth, it is possible that providers did modify or even erase their orders even after selecting override in response to the warning; it is also possible that providers reentered the same order after choosing erase. Unfortunately auditing for actions such as these would be extremely laborious. Finally, the study was conducted at a single medical center using a single order‐entry system. The system in use at our medical center is in use at one‐third of the 6000 hospitals in the United States, though certainly not all are using our version. Even if a hospital was using the same CPOE version and interaction database as our institution, variations in patient population and local decisions modifying how the database interacts with the warning presentation system might affect reproducibility at that institution.

Commonly encountered medication warnings are overridden at extremely high rates, and in our study this was particularly so for medications on the ISMP list, when ordered by physicians in training. Warnings of little clinical significance must be identified and eliminated, the most important warnings need to be visually distinct to increase user attention, and further research should be done into the patient, provider, setting, and medication factors that affect user responses to warnings, so that they may be customized accordingly and their significance increased. Doing so will enable us to reap the maximum possible potential from our CPOE systems, and increase the CPOE's power to protect our most vulnerable patients from our most dangerous medications, particularly when cared for by our most inexperienced physicians.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank, in particular, Scott Carey, Research Informatics Manager, for assistance with data collection. Additional thanks go to Olga Sherman and Kathleen Ancinich for assistance with data collection and management.

Disclosures: This research was supported in part by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. All listed authors contributed substantially to the study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. No one who fulfills these criteria has been excluded from authorship. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors. The authors have no competing interests to declare.

- , , , et al., Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280:1311–1316.

- , , , , , . Effects of computerized provider order entry on prescribing practices. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2741–2747.

- , , , et al. Effects of computerized clinician decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:1223–1238.

- , , , et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support on the rates of adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:451–458.

- , , . The impact of computerized physician medication order entry in hospitalized patients—a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:365–376.

- , , , et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians' prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531–538.

- , , , , . Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:613–623.

- , , , . Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138–147.

- , , , , , . Evaluating clinical decision support systems: monitoring CPOE order check override rates in the Department of Veterans Affairs' Computerized Patient Record System. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:620–626.

- , , . GPs' views on computerized drug interaction alerts: questionnaire survey. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:377–382.

- , , , et al. Clinicians' assessments of electronic medication safety alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1627–1632.

- , , , , . A mixed method study of the merits of e‐prescribing drug alerts in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:442–446.

- . CPOE and clinical decision support in hospitals: getting the benefits: comment on “Unintended effects of a computerized physician order entry nearly hard‐stop alert to prevent a drug interaction.” Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1583–1584.

- , , . Critical drug‐drug interactions for use in electronic health records systems with computerized physician order entry: review of leading approaches. J Patient Saf. 2011;7:61–65.

- , , , , . Clinical decision support systems could be modified to reduce 'alert fatigue' while still minimizing the risk of litigation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:2310–2317.

- , , , . Critical issues associated with drug‐drug interactions: highlights of a multistakeholder conference. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:941–946.

- , , , , , . Development of a context model to prioritize drug safety alerts in CPOE systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:35.

- , , , et al. Factors influencing alert acceptance: a novel approach for predicting the success of clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:479–484.