User login

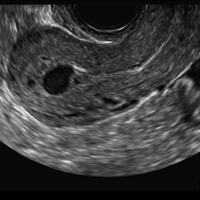

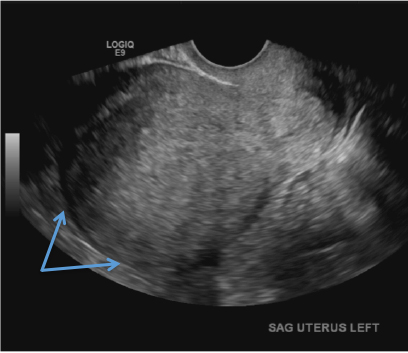

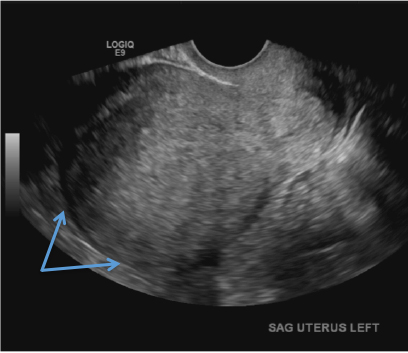

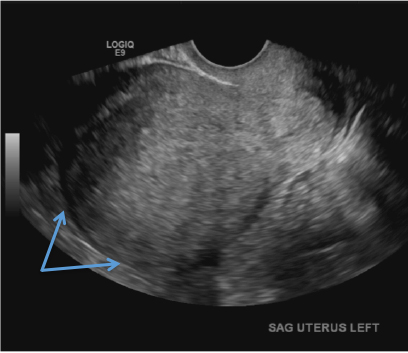

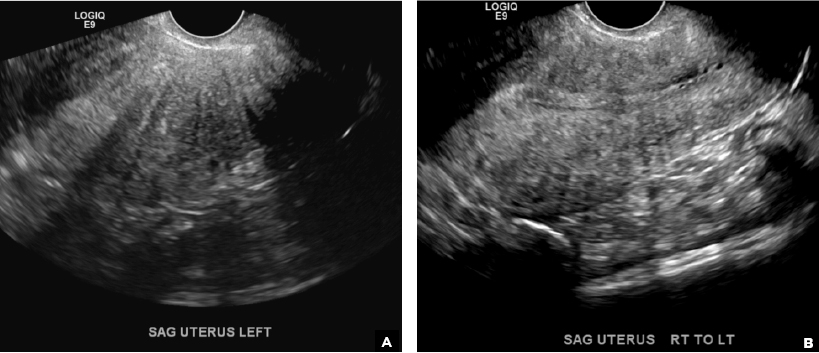

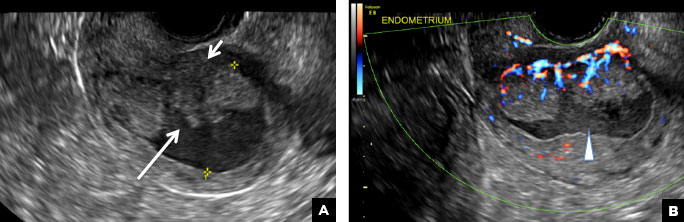

Adenomyosis in the spotlight, but which sign is featured?

A) Globular enlarged uterus INCORRECT

A homogeneously enlarged uterus in the absence of fibroids is characteristic of adenomyosis.1

B) Cystic myometrial spaces INCORRECT

Myometrial cysts are dilated cystic glands or foci of hemorrhage within heterotopic endometrial tissue.2 They are often less than 5 mm in size but can be extensive and of variable sizes and can be differentiated from arcuate veins seen in the outer myometrium by the use of color Doppler.1,2

C) Asymmetric myometrial thickening INCORRECT

The finding of asymmetric uterine wall thickening in adenomyosis is usually seen when there is focal disease and presents with wall thickening that demonstrates anteroposterior asymmetry.1

D) Indistinct endomyometrial interface INCORRECT

The heterotopic endometrial tissue invading the myometrium obscures the normal endometrial myometrial border with pseudo-widening of the endometrial echo resulting in poor definition of the endomyometrial junction.1,2

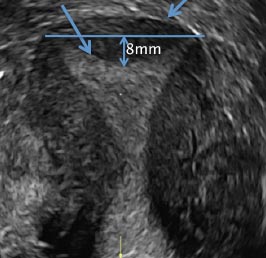

E) Myometrial linear striations CORRECT

A hyperplastic reaction to the infiltration of the heterotrophic endometrial glands into the myometrium results in radiating linear echogenic striations (sometimes referred to as the "venetian blinds" sign).1,2

- Sakhel A, Abuhamad A. Sonography of adenomyosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(5):805-808.

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160.

A) Globular enlarged uterus INCORRECT

A homogeneously enlarged uterus in the absence of fibroids is characteristic of adenomyosis.1

B) Cystic myometrial spaces INCORRECT

Myometrial cysts are dilated cystic glands or foci of hemorrhage within heterotopic endometrial tissue.2 They are often less than 5 mm in size but can be extensive and of variable sizes and can be differentiated from arcuate veins seen in the outer myometrium by the use of color Doppler.1,2

C) Asymmetric myometrial thickening INCORRECT

The finding of asymmetric uterine wall thickening in adenomyosis is usually seen when there is focal disease and presents with wall thickening that demonstrates anteroposterior asymmetry.1

D) Indistinct endomyometrial interface INCORRECT

The heterotopic endometrial tissue invading the myometrium obscures the normal endometrial myometrial border with pseudo-widening of the endometrial echo resulting in poor definition of the endomyometrial junction.1,2

E) Myometrial linear striations CORRECT

A hyperplastic reaction to the infiltration of the heterotrophic endometrial glands into the myometrium results in radiating linear echogenic striations (sometimes referred to as the "venetian blinds" sign).1,2

A) Globular enlarged uterus INCORRECT

A homogeneously enlarged uterus in the absence of fibroids is characteristic of adenomyosis.1

B) Cystic myometrial spaces INCORRECT

Myometrial cysts are dilated cystic glands or foci of hemorrhage within heterotopic endometrial tissue.2 They are often less than 5 mm in size but can be extensive and of variable sizes and can be differentiated from arcuate veins seen in the outer myometrium by the use of color Doppler.1,2

C) Asymmetric myometrial thickening INCORRECT

The finding of asymmetric uterine wall thickening in adenomyosis is usually seen when there is focal disease and presents with wall thickening that demonstrates anteroposterior asymmetry.1

D) Indistinct endomyometrial interface INCORRECT

The heterotopic endometrial tissue invading the myometrium obscures the normal endometrial myometrial border with pseudo-widening of the endometrial echo resulting in poor definition of the endomyometrial junction.1,2

E) Myometrial linear striations CORRECT

A hyperplastic reaction to the infiltration of the heterotrophic endometrial glands into the myometrium results in radiating linear echogenic striations (sometimes referred to as the "venetian blinds" sign).1,2

- Sakhel A, Abuhamad A. Sonography of adenomyosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(5):805-808.

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160.

- Sakhel A, Abuhamad A. Sonography of adenomyosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(5):805-808.

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:S147-S160.

A 37-year-old woman with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea presents to her gynecologist. Physical exam suggests an enlarged uterus; the gynecologist orders pelvic ultrasonography.

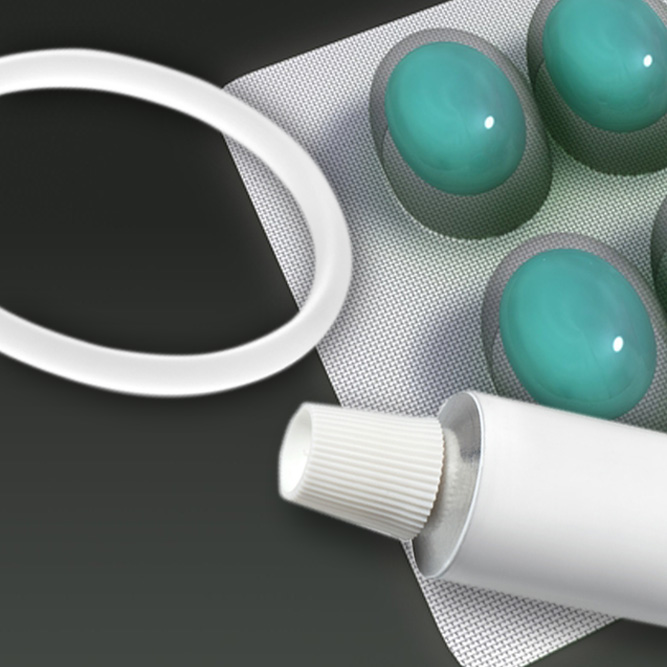

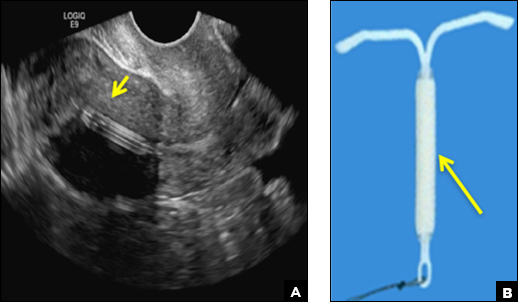

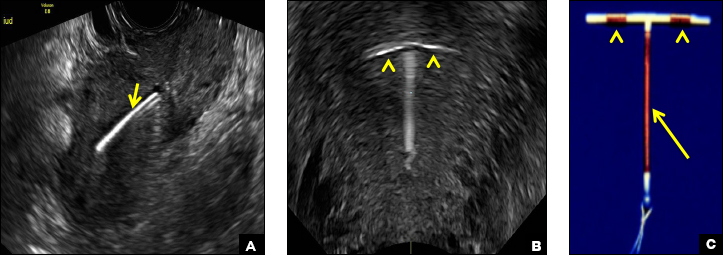

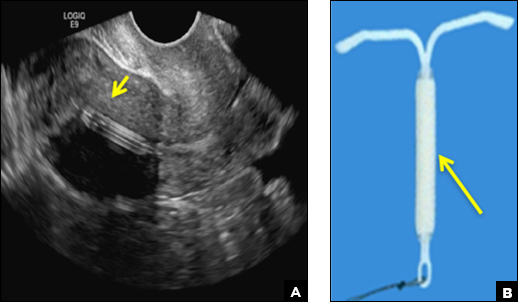

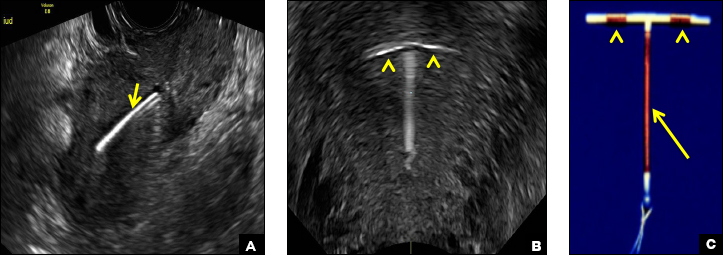

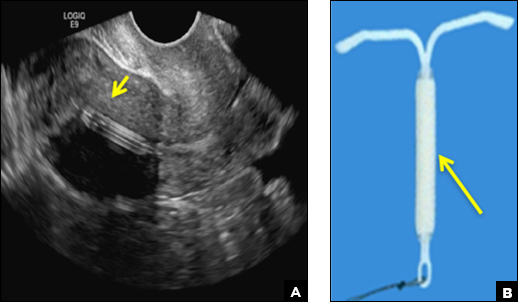

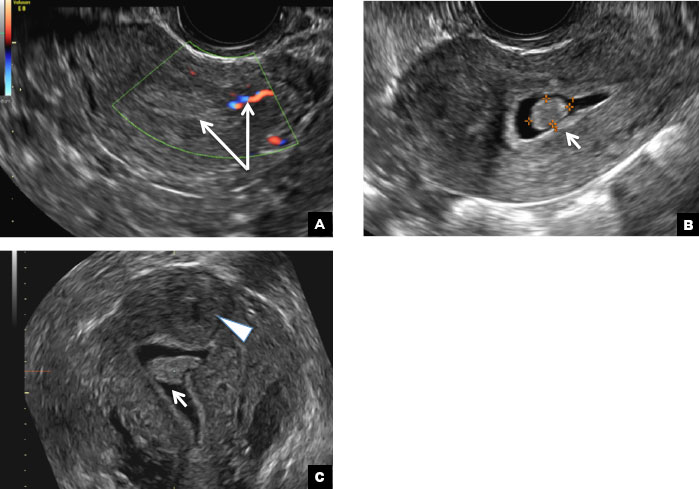

Eye spy: Name that IUD

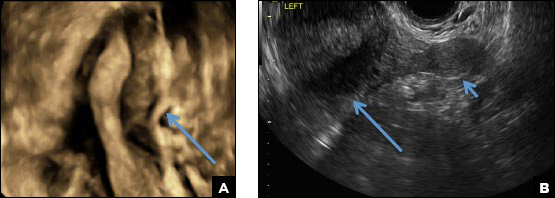

A) Mirena or Liletta (52 mg LNG-IUD) CORRECT

Mirena (Bayer) and Liletta (Allergan) are progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) of similar size and shape. On ultrasonography, both the arms and the distal tip are echogenic. The progestin-containing plastic sleeve surrounding the stem in the middle demonstrates a laminated acoustic shadowing with distinctive parallel lines.1–4

B) Small-framed LNG-IUDs: Skyla (13.5 mg) or Kyleena (19.5 mg) INCORRECT

Skyla (Bayer) and Kyleena (Bayer) are small-framed LNG-IUDs. The ultrasound appearance of Skyla (LNG 13.5 mg) is similar to that of Mirena but has a markedly echogenic silver ring superiorly just below the crossbar, best seen with 2D (sagittal) views but also imaged with 3D ultrasound.1,2,5

The Kyleena device (LNG 19.5 mg) uses the same smaller T-shaped frame and metal ring, but the plastic sleeve is longer to accommodate the greater quantity of progestin.6

C) Paragard (intrauterine copper contraceptive) INCORRECT

Paragard (Teva Women’s Health) is a nonhormonal IUD containing copper wire wrapped around its stem and solid copper bands on each crossbar. On ultrasonography, the stem is uniformly and markedly echogenic due to the copper wire.1,2,7

- Stalnaker ML, Kaunitz AM. How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound. OBG Manag. 2014;26(8):38,40–41,44.

- Boortz HE, Margolis DJ, Ragavendra N, Patel MK, Kadell BM. Migration of intrauterine devices: Radiologic findings and implications for patient care. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):335–352.

- Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Allergan; 2015.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Paragard [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Women’s Health, Inc; 2014.

A) Mirena or Liletta (52 mg LNG-IUD) CORRECT

Mirena (Bayer) and Liletta (Allergan) are progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) of similar size and shape. On ultrasonography, both the arms and the distal tip are echogenic. The progestin-containing plastic sleeve surrounding the stem in the middle demonstrates a laminated acoustic shadowing with distinctive parallel lines.1–4

B) Small-framed LNG-IUDs: Skyla (13.5 mg) or Kyleena (19.5 mg) INCORRECT

Skyla (Bayer) and Kyleena (Bayer) are small-framed LNG-IUDs. The ultrasound appearance of Skyla (LNG 13.5 mg) is similar to that of Mirena but has a markedly echogenic silver ring superiorly just below the crossbar, best seen with 2D (sagittal) views but also imaged with 3D ultrasound.1,2,5

The Kyleena device (LNG 19.5 mg) uses the same smaller T-shaped frame and metal ring, but the plastic sleeve is longer to accommodate the greater quantity of progestin.6

C) Paragard (intrauterine copper contraceptive) INCORRECT

Paragard (Teva Women’s Health) is a nonhormonal IUD containing copper wire wrapped around its stem and solid copper bands on each crossbar. On ultrasonography, the stem is uniformly and markedly echogenic due to the copper wire.1,2,7

A) Mirena or Liletta (52 mg LNG-IUD) CORRECT

Mirena (Bayer) and Liletta (Allergan) are progestin-releasing intrauterine devices (IUDs) of similar size and shape. On ultrasonography, both the arms and the distal tip are echogenic. The progestin-containing plastic sleeve surrounding the stem in the middle demonstrates a laminated acoustic shadowing with distinctive parallel lines.1–4

B) Small-framed LNG-IUDs: Skyla (13.5 mg) or Kyleena (19.5 mg) INCORRECT

Skyla (Bayer) and Kyleena (Bayer) are small-framed LNG-IUDs. The ultrasound appearance of Skyla (LNG 13.5 mg) is similar to that of Mirena but has a markedly echogenic silver ring superiorly just below the crossbar, best seen with 2D (sagittal) views but also imaged with 3D ultrasound.1,2,5

The Kyleena device (LNG 19.5 mg) uses the same smaller T-shaped frame and metal ring, but the plastic sleeve is longer to accommodate the greater quantity of progestin.6

C) Paragard (intrauterine copper contraceptive) INCORRECT

Paragard (Teva Women’s Health) is a nonhormonal IUD containing copper wire wrapped around its stem and solid copper bands on each crossbar. On ultrasonography, the stem is uniformly and markedly echogenic due to the copper wire.1,2,7

- Stalnaker ML, Kaunitz AM. How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound. OBG Manag. 2014;26(8):38,40–41,44.

- Boortz HE, Margolis DJ, Ragavendra N, Patel MK, Kadell BM. Migration of intrauterine devices: Radiologic findings and implications for patient care. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):335–352.

- Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Allergan; 2015.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Paragard [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Women’s Health, Inc; 2014.

- Stalnaker ML, Kaunitz AM. How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound. OBG Manag. 2014;26(8):38,40–41,44.

- Boortz HE, Margolis DJ, Ragavendra N, Patel MK, Kadell BM. Migration of intrauterine devices: Radiologic findings and implications for patient care. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):335–352.

- Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Liletta [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Allergan; 2015.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer; 2000.

- Paragard [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Women’s Health, Inc; 2014.

A 25-year-old woman using an IUD presented to her ObGyn’s office for follow-up care of a 4- to 5-cm left simple ovarian cyst. A pelvic ultrasound was performed. The ovarian cyst had resolved and a fundally-positioned IUD was imaged.

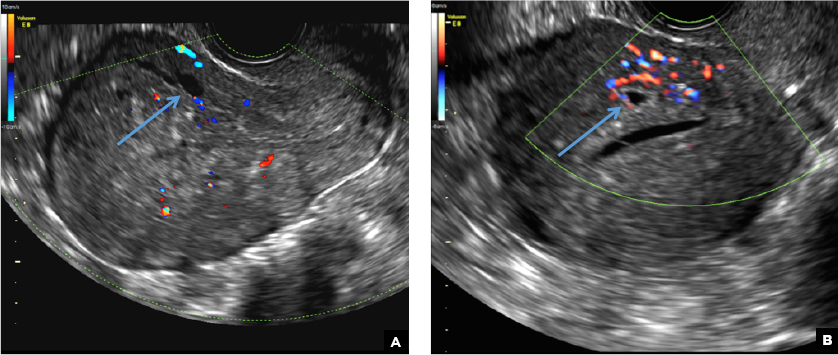

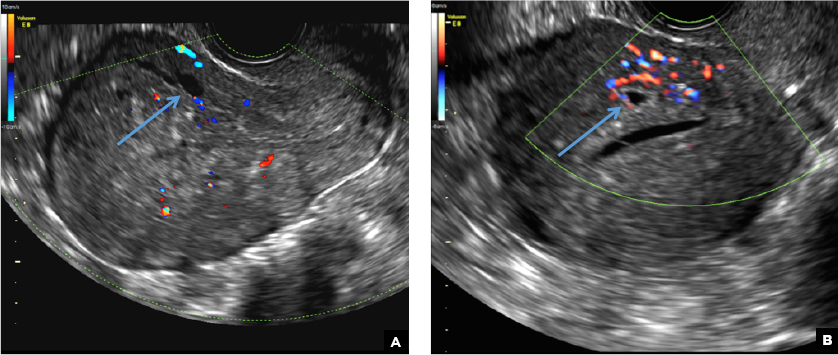

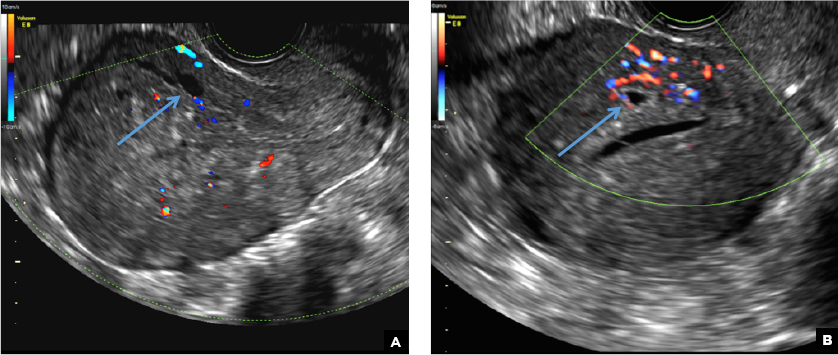

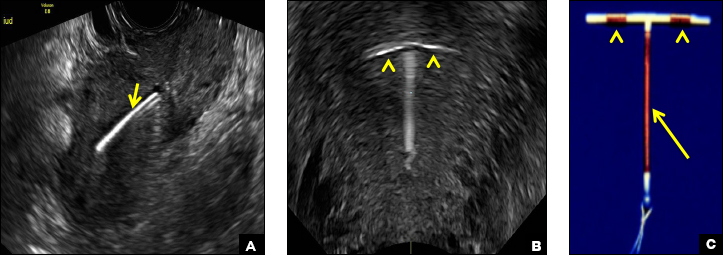

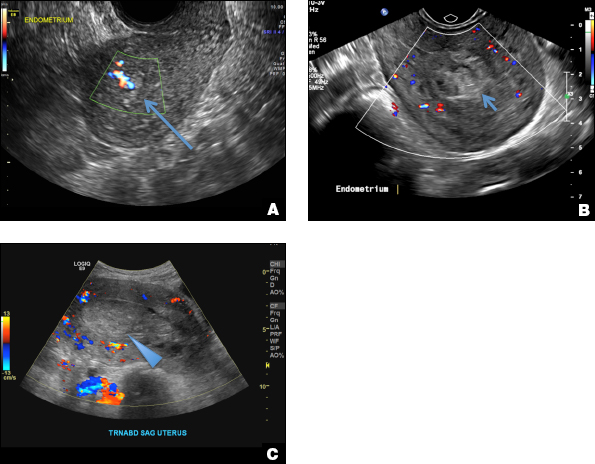

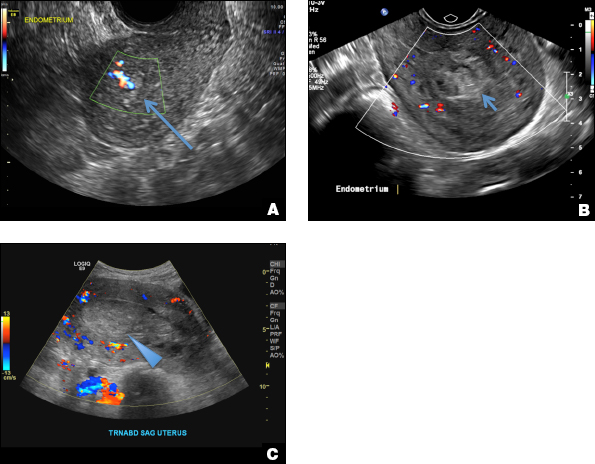

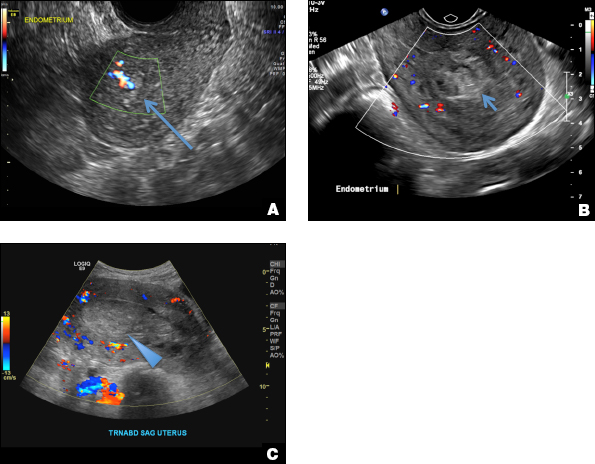

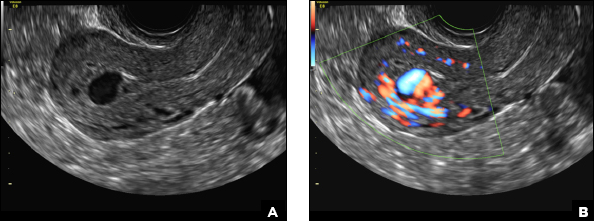

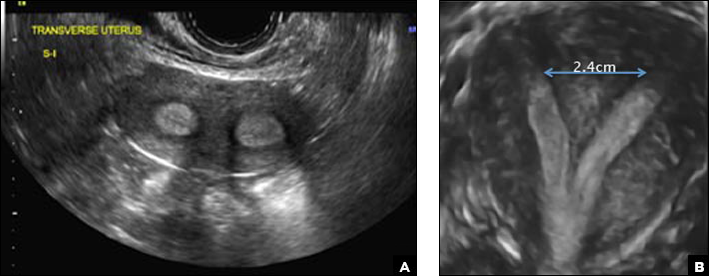

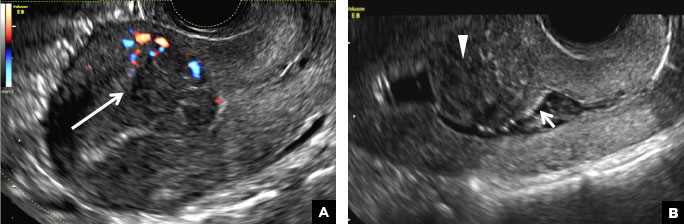

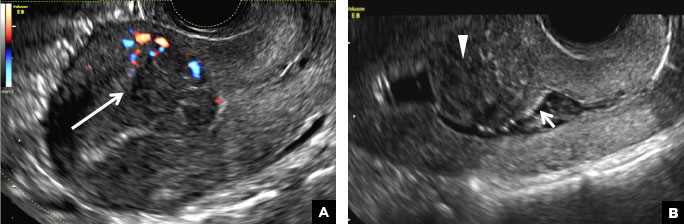

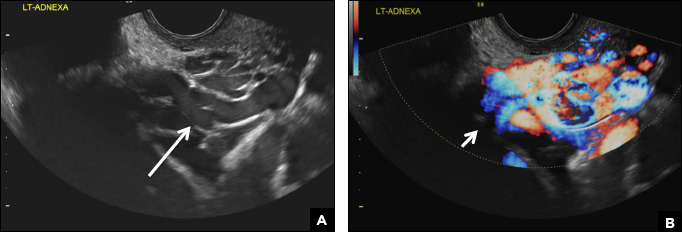

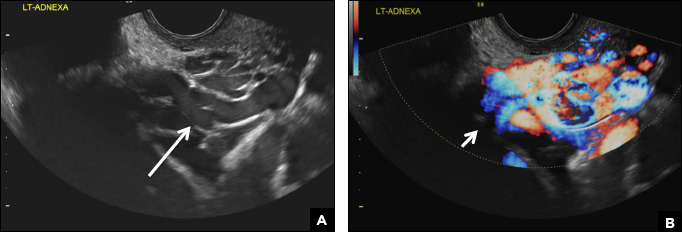

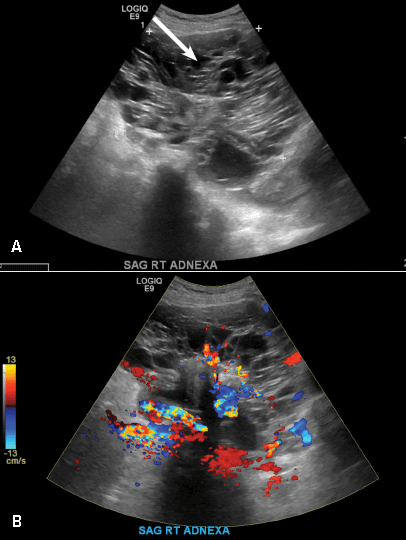

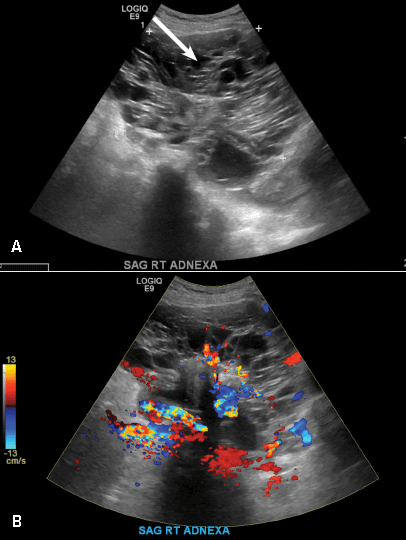

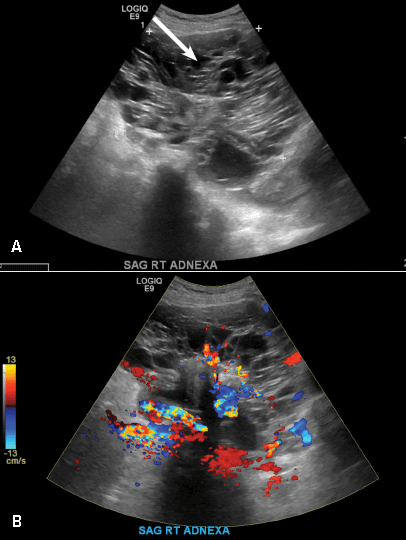

A woman with heavy noncyclical bleeding 6 weeks after abortion

A) Retained products of conception (RPOC) INCORRECT

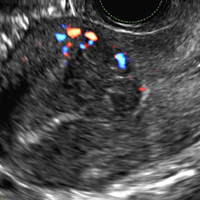

RPOC is a common complication arising from the presence of retained placental or fetal tissue after delivery, spontaneous, or elective abortion and is diagnosed by the presence of chorionic villi suggesting trophoblastic or placental tissue.1,2 Interpreting imaging findings is often a challenge secondary to the nonspecific findings of RPOC and often overlapping imaging features with blood products and enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Management usually is based on clinical findings in collaboration with supportive imaging features. On ultrasound, RPOC is suspected when there is a thickened endometrial echo complex (>8 mm to 13 mm) and/or the presence of an endometrial mass. Additionally, increased vascularity on color Doppler significantly increases the likelihood of RPOC; the absence of vascularity can be seen with both blood products and avascular RPOC.1 Vascularity in RPOC can be differentiated from EMV by its extension into the endometrium.

B) Complete hydatidiform mole INCORRECT

Complete hydatidiform mole (CHM) usually presents early in gestation with markedly elevated β-hCG. On ultrasound, it appears classically as an echogenic mass with innumerable small cystic spaces creating a “snowstorm or cluster of grape appearance” from hydropic chorionic villi along with larger irregular fluid collections and the absence of fetal parts.3 Ovarian hyperstimulation from elevated β-hCG can result in large bilateral ovarian cysts called theca lutein cysts.3

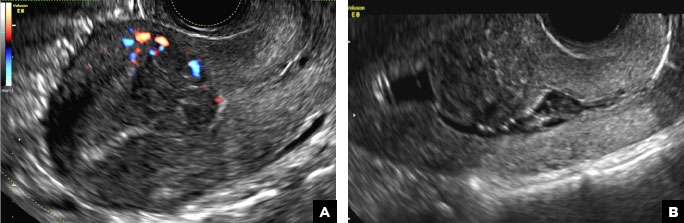

C) Enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). CORRECT

EMV is an extremely rare cause of postpregnancy hemorrhage most often seen secondary to iatrogenic causes but can also be congenital or acquired from excessive hormone stimulation.2 On ultrasound, EMV appears as a hypoechoic vascular lesion or serpiginous network of vessels located in the myometrium with increased velocity and low resistance waveform on spectral Doppler.4 Subinvolution of placental site implantation where there is failure of the vessels to involute can sometimes be indistinguishable from acquired EMV and occasionally difficult to differentiate from RPOC.1 In stable patients with equivocal ultrasound findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with its superior contrast resolution can help delineate the endometrium from myometrium and clearly identify EMV as serpiginous signal voids in the myometrium with avid enhancement following contrast.5 Computed tomography (CT) angiogram is also of value in both the diagnosis and pretreatment planning of EMV prior to transcatheter uterine artery embolization.

D) Endometritis INCORRECT

Endometritis is a common cause of fever and sepsis in the postpartum state, but it can also occur after procedures such as uterine fibroid embolization (UFE). On ultrasound, the endometrium usually is distended with avascular echogenic fluid. The presence of shadowing gas in the appropriate clinical setting is concerning for endometritis. CT scan can confirm the presence of gas and evaluate for septic thrombophlebitis, an uncommon, life-threatening complication of endometritis.

- Sellmyer MA, Desser TS, Maturen KE, Jeffrey RB Jr, Kamaya A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. RadioGraphics. 2013;33(3):781–796.

- Plunk M, Lee JH, Kani K, Dighe M. Imaging of postpartum complications: a multimodality review. AJR. 2013;200(2):W143–W154.

- Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Haroun RR, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: clinical and imaging features. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(2):681–700.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Haynes MC, Monteagudo A, Khatib N, Kovacs S. Ultrasound diagnosis and management of acquired uterine enhanced myometrial vascularity arteriovenous malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):731.e1–e10.

- Yoon DJ, Jones M, Taani JA, Buhimschi C, Dowell JD. A systematic review of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformations: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and transcatheter treatment. Am J Perinatol Rep. 2016;6(1):e6–e14.

A) Retained products of conception (RPOC) INCORRECT

RPOC is a common complication arising from the presence of retained placental or fetal tissue after delivery, spontaneous, or elective abortion and is diagnosed by the presence of chorionic villi suggesting trophoblastic or placental tissue.1,2 Interpreting imaging findings is often a challenge secondary to the nonspecific findings of RPOC and often overlapping imaging features with blood products and enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Management usually is based on clinical findings in collaboration with supportive imaging features. On ultrasound, RPOC is suspected when there is a thickened endometrial echo complex (>8 mm to 13 mm) and/or the presence of an endometrial mass. Additionally, increased vascularity on color Doppler significantly increases the likelihood of RPOC; the absence of vascularity can be seen with both blood products and avascular RPOC.1 Vascularity in RPOC can be differentiated from EMV by its extension into the endometrium.

B) Complete hydatidiform mole INCORRECT

Complete hydatidiform mole (CHM) usually presents early in gestation with markedly elevated β-hCG. On ultrasound, it appears classically as an echogenic mass with innumerable small cystic spaces creating a “snowstorm or cluster of grape appearance” from hydropic chorionic villi along with larger irregular fluid collections and the absence of fetal parts.3 Ovarian hyperstimulation from elevated β-hCG can result in large bilateral ovarian cysts called theca lutein cysts.3

C) Enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). CORRECT

EMV is an extremely rare cause of postpregnancy hemorrhage most often seen secondary to iatrogenic causes but can also be congenital or acquired from excessive hormone stimulation.2 On ultrasound, EMV appears as a hypoechoic vascular lesion or serpiginous network of vessels located in the myometrium with increased velocity and low resistance waveform on spectral Doppler.4 Subinvolution of placental site implantation where there is failure of the vessels to involute can sometimes be indistinguishable from acquired EMV and occasionally difficult to differentiate from RPOC.1 In stable patients with equivocal ultrasound findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with its superior contrast resolution can help delineate the endometrium from myometrium and clearly identify EMV as serpiginous signal voids in the myometrium with avid enhancement following contrast.5 Computed tomography (CT) angiogram is also of value in both the diagnosis and pretreatment planning of EMV prior to transcatheter uterine artery embolization.

D) Endometritis INCORRECT

Endometritis is a common cause of fever and sepsis in the postpartum state, but it can also occur after procedures such as uterine fibroid embolization (UFE). On ultrasound, the endometrium usually is distended with avascular echogenic fluid. The presence of shadowing gas in the appropriate clinical setting is concerning for endometritis. CT scan can confirm the presence of gas and evaluate for septic thrombophlebitis, an uncommon, life-threatening complication of endometritis.

A) Retained products of conception (RPOC) INCORRECT

RPOC is a common complication arising from the presence of retained placental or fetal tissue after delivery, spontaneous, or elective abortion and is diagnosed by the presence of chorionic villi suggesting trophoblastic or placental tissue.1,2 Interpreting imaging findings is often a challenge secondary to the nonspecific findings of RPOC and often overlapping imaging features with blood products and enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Management usually is based on clinical findings in collaboration with supportive imaging features. On ultrasound, RPOC is suspected when there is a thickened endometrial echo complex (>8 mm to 13 mm) and/or the presence of an endometrial mass. Additionally, increased vascularity on color Doppler significantly increases the likelihood of RPOC; the absence of vascularity can be seen with both blood products and avascular RPOC.1 Vascularity in RPOC can be differentiated from EMV by its extension into the endometrium.

B) Complete hydatidiform mole INCORRECT

Complete hydatidiform mole (CHM) usually presents early in gestation with markedly elevated β-hCG. On ultrasound, it appears classically as an echogenic mass with innumerable small cystic spaces creating a “snowstorm or cluster of grape appearance” from hydropic chorionic villi along with larger irregular fluid collections and the absence of fetal parts.3 Ovarian hyperstimulation from elevated β-hCG can result in large bilateral ovarian cysts called theca lutein cysts.3

C) Enhanced myometrial vascularity (EMV) also known as arteriovenous malformation (AVM). CORRECT

EMV is an extremely rare cause of postpregnancy hemorrhage most often seen secondary to iatrogenic causes but can also be congenital or acquired from excessive hormone stimulation.2 On ultrasound, EMV appears as a hypoechoic vascular lesion or serpiginous network of vessels located in the myometrium with increased velocity and low resistance waveform on spectral Doppler.4 Subinvolution of placental site implantation where there is failure of the vessels to involute can sometimes be indistinguishable from acquired EMV and occasionally difficult to differentiate from RPOC.1 In stable patients with equivocal ultrasound findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with its superior contrast resolution can help delineate the endometrium from myometrium and clearly identify EMV as serpiginous signal voids in the myometrium with avid enhancement following contrast.5 Computed tomography (CT) angiogram is also of value in both the diagnosis and pretreatment planning of EMV prior to transcatheter uterine artery embolization.

D) Endometritis INCORRECT

Endometritis is a common cause of fever and sepsis in the postpartum state, but it can also occur after procedures such as uterine fibroid embolization (UFE). On ultrasound, the endometrium usually is distended with avascular echogenic fluid. The presence of shadowing gas in the appropriate clinical setting is concerning for endometritis. CT scan can confirm the presence of gas and evaluate for septic thrombophlebitis, an uncommon, life-threatening complication of endometritis.

- Sellmyer MA, Desser TS, Maturen KE, Jeffrey RB Jr, Kamaya A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. RadioGraphics. 2013;33(3):781–796.

- Plunk M, Lee JH, Kani K, Dighe M. Imaging of postpartum complications: a multimodality review. AJR. 2013;200(2):W143–W154.

- Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Haroun RR, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: clinical and imaging features. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(2):681–700.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Haynes MC, Monteagudo A, Khatib N, Kovacs S. Ultrasound diagnosis and management of acquired uterine enhanced myometrial vascularity arteriovenous malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):731.e1–e10.

- Yoon DJ, Jones M, Taani JA, Buhimschi C, Dowell JD. A systematic review of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformations: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and transcatheter treatment. Am J Perinatol Rep. 2016;6(1):e6–e14.

- Sellmyer MA, Desser TS, Maturen KE, Jeffrey RB Jr, Kamaya A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. RadioGraphics. 2013;33(3):781–796.

- Plunk M, Lee JH, Kani K, Dighe M. Imaging of postpartum complications: a multimodality review. AJR. 2013;200(2):W143–W154.

- Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Haroun RR, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: clinical and imaging features. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(2):681–700.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Haynes MC, Monteagudo A, Khatib N, Kovacs S. Ultrasound diagnosis and management of acquired uterine enhanced myometrial vascularity arteriovenous malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):731.e1–e10.

- Yoon DJ, Jones M, Taani JA, Buhimschi C, Dowell JD. A systematic review of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformations: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and transcatheter treatment. Am J Perinatol Rep. 2016;6(1):e6–e14.

A 25-year-old woman presents to her ObGyn’s office with heavy noncyclical bleeding 6 weeks after a first-trimester suction curettage abortion. Transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography of the uterus with grayscale (A) and color Doppler (B) are performed.

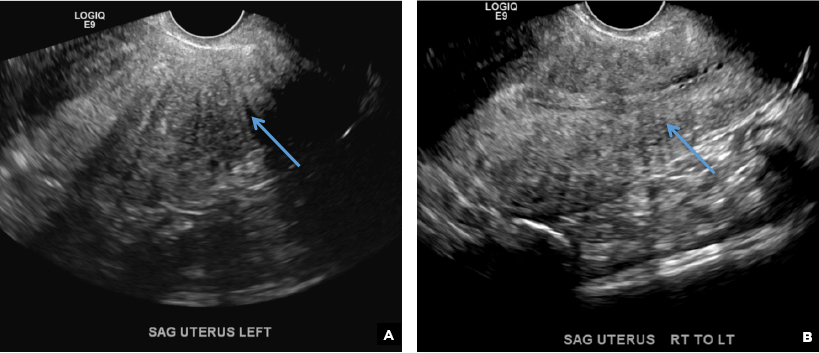

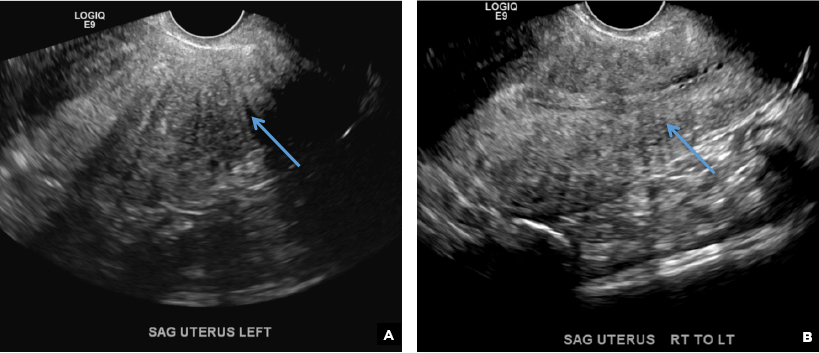

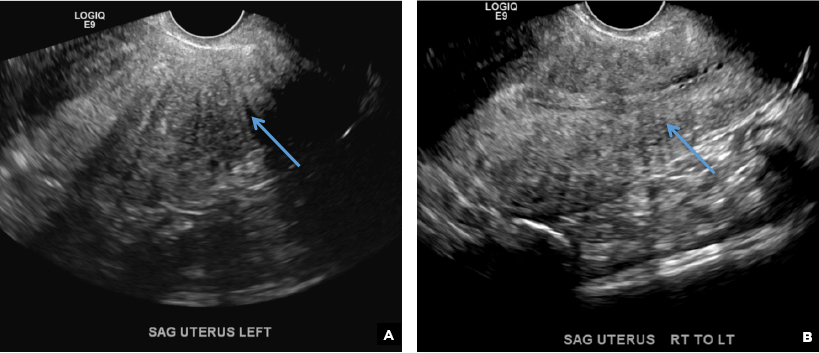

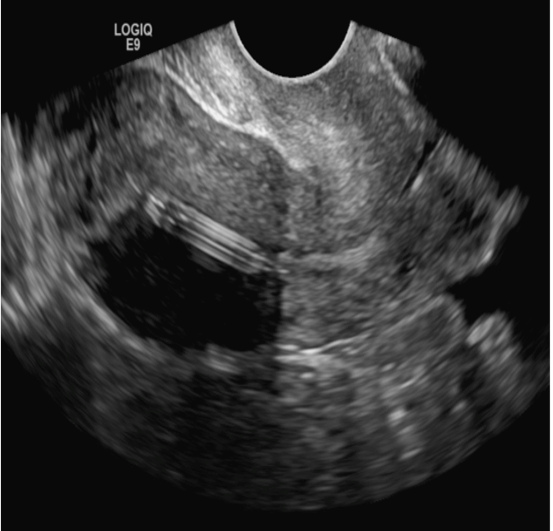

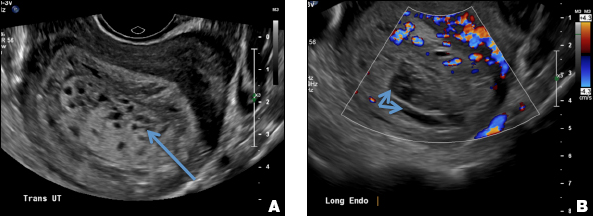

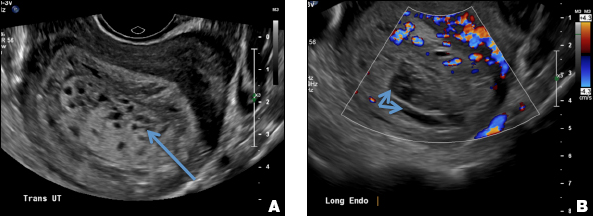

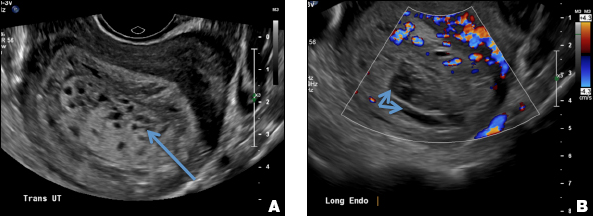

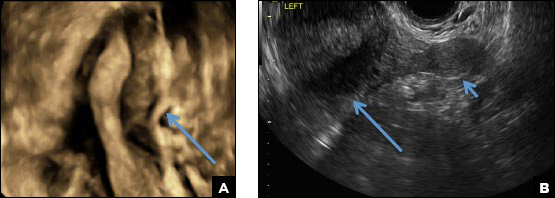

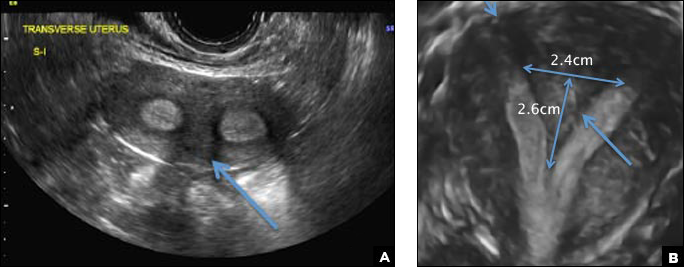

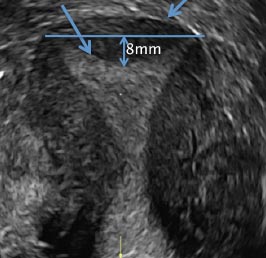

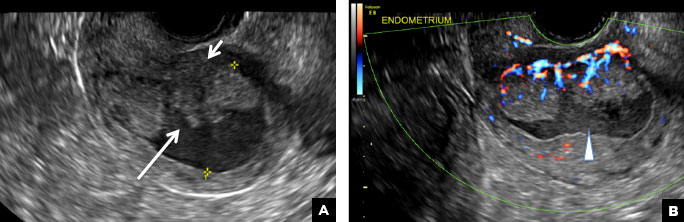

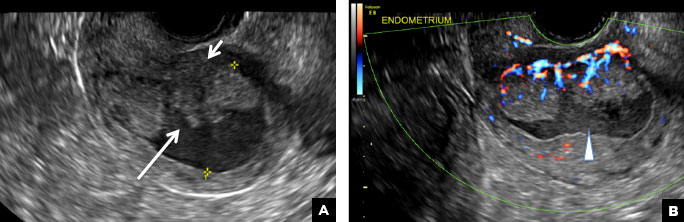

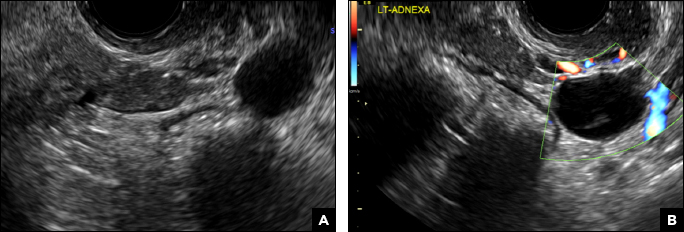

Multiple miscarriages in a 29-year-old woman

A) Didelphys uterus INCORRECT

A didelphys uterus occurs as a result of complete nonfusion of the Müllerian duct, resulting in duplicated uterine horns, duplicated cervices, and occasionally the proximal vagina, which is often associated with a transverse or longitudinal vaginal septum.1,2 Fusion anomalies (didelphys and bicornuate) can be differentiated from resorption anomalies (septate and arcuate) on ultrasonography (US) by a deep fundal cleft (>1 cm).1 3D US is highly accurate in identifying Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs), it correlates well with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and it is more cost effective and accessible.3 For the didelphys uterus, 3D US obtained coronal to the uterine fundus often demonstrates widely divergent uterine horns separated by a deep serosal fundal cleft (>1 cm) and noncommunicating endometrial cavities with 2 cervices.1 Identifying a duplicated vaginal canal can help differentiate a didelphys uterus from a bicornuate bicollis uterus.1

B) Unicornuate uterus INCORRECT

A unicornuate uterus results from arrested development of one Müllerian duct and normal development of the other. There are 4 different subtypes: no rudimentary horn, rudimentary horn without endometrial cavity, rudimentary horn with communicating endometrial cavity, and rudimentary horn with noncommunicating uterine cavity.1 Renal anomalies, especially renal agenesis when present, are usually ipsilateral to the rudimentary horn.1 On US, unicornuate uterus appears as a lobular oblong (banana-shaped) structure away from the midline. The rudimentary horn is often difficult to identify and, when seen, the presence or absence of endometrium is an important finding.1

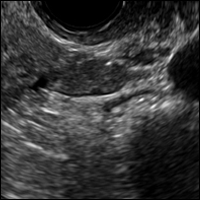

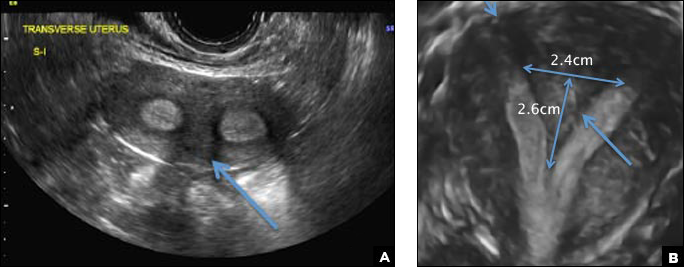

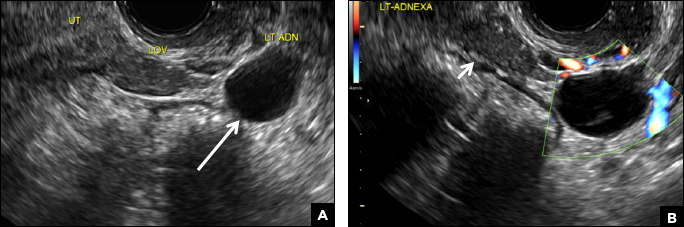

C) Partial septate uterus CORRECT

A septate uterus is a result of a resorption anomaly. The septum may be partial (subseptate) or complete secondary to failure of resorption of the uterovaginal septum. A complete septum extends to the external cervical os and occasionally to the vagina.1 US demonstrates interruption of the myometrium by a hypoechoic fibrous septum and/or a muscular septum which is isoechoic to the myometrium and arises midline from the fundus.1 3D US often clearly delineates the septum and improves visualization of the external fundal contour.2 The external fundal contour in septate uterus is convex (little or no serosal fundal cleft) and the apex is greater than 5 mm above the interostial line compared with a bicornuate or didelphys uterus, where the apex is less than 5 mm from the interostial line.1,2 Additionally, the intercornual distance is less than 4 cm.4 A septate uterus with duplicated cervix can appear similar to a bicornuate bicollis uterus and can be correctly diagnosed by evaluating the external fundal contour.1

D) Arcuate uterus INCORRECT

The arcuate uterus also represents a resorption anomaly as a sequela of near-complete resorption of the uterovaginal septum.1 On 3D US, the fundal indentation in an arcuate uterus is well delineated and appears broad based with an obtuse angle at the most central point, which can help differentiate it from a septate uterus that has an acute angle.2,3 Both an arcuate and a septate uterus have a normal external (serosal) fundal contour.2,3 With an arcuate uterus, the length of the vertical measurement from the tubal ostia line, which is drawn horizontally between the tubal ostia to the fundal midline component of the endometrial cavity, is 1 cm or less. With a septate uterus, this vertical distance is greater than 1 cm.

- CambriaBehr SC, Courtier JL, Qayyum A. Imaging of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. RadioGraphics. 2012;32(6):e23.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Diaz D, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomaly and concordance with MRI. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol.Cambria 2010;35(5):593–601.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamed AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

- CambriaChandler TM, Machan LS, Cooperberg PL, Harris AC, Chang SD. MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies: from diagnosis to intervention.Cambria Br J Radiol. 2009;82(984):1034–1042.

A) Didelphys uterus INCORRECT

A didelphys uterus occurs as a result of complete nonfusion of the Müllerian duct, resulting in duplicated uterine horns, duplicated cervices, and occasionally the proximal vagina, which is often associated with a transverse or longitudinal vaginal septum.1,2 Fusion anomalies (didelphys and bicornuate) can be differentiated from resorption anomalies (septate and arcuate) on ultrasonography (US) by a deep fundal cleft (>1 cm).1 3D US is highly accurate in identifying Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs), it correlates well with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and it is more cost effective and accessible.3 For the didelphys uterus, 3D US obtained coronal to the uterine fundus often demonstrates widely divergent uterine horns separated by a deep serosal fundal cleft (>1 cm) and noncommunicating endometrial cavities with 2 cervices.1 Identifying a duplicated vaginal canal can help differentiate a didelphys uterus from a bicornuate bicollis uterus.1

B) Unicornuate uterus INCORRECT

A unicornuate uterus results from arrested development of one Müllerian duct and normal development of the other. There are 4 different subtypes: no rudimentary horn, rudimentary horn without endometrial cavity, rudimentary horn with communicating endometrial cavity, and rudimentary horn with noncommunicating uterine cavity.1 Renal anomalies, especially renal agenesis when present, are usually ipsilateral to the rudimentary horn.1 On US, unicornuate uterus appears as a lobular oblong (banana-shaped) structure away from the midline. The rudimentary horn is often difficult to identify and, when seen, the presence or absence of endometrium is an important finding.1

C) Partial septate uterus CORRECT

A septate uterus is a result of a resorption anomaly. The septum may be partial (subseptate) or complete secondary to failure of resorption of the uterovaginal septum. A complete septum extends to the external cervical os and occasionally to the vagina.1 US demonstrates interruption of the myometrium by a hypoechoic fibrous septum and/or a muscular septum which is isoechoic to the myometrium and arises midline from the fundus.1 3D US often clearly delineates the septum and improves visualization of the external fundal contour.2 The external fundal contour in septate uterus is convex (little or no serosal fundal cleft) and the apex is greater than 5 mm above the interostial line compared with a bicornuate or didelphys uterus, where the apex is less than 5 mm from the interostial line.1,2 Additionally, the intercornual distance is less than 4 cm.4 A septate uterus with duplicated cervix can appear similar to a bicornuate bicollis uterus and can be correctly diagnosed by evaluating the external fundal contour.1

D) Arcuate uterus INCORRECT

The arcuate uterus also represents a resorption anomaly as a sequela of near-complete resorption of the uterovaginal septum.1 On 3D US, the fundal indentation in an arcuate uterus is well delineated and appears broad based with an obtuse angle at the most central point, which can help differentiate it from a septate uterus that has an acute angle.2,3 Both an arcuate and a septate uterus have a normal external (serosal) fundal contour.2,3 With an arcuate uterus, the length of the vertical measurement from the tubal ostia line, which is drawn horizontally between the tubal ostia to the fundal midline component of the endometrial cavity, is 1 cm or less. With a septate uterus, this vertical distance is greater than 1 cm.

A) Didelphys uterus INCORRECT

A didelphys uterus occurs as a result of complete nonfusion of the Müllerian duct, resulting in duplicated uterine horns, duplicated cervices, and occasionally the proximal vagina, which is often associated with a transverse or longitudinal vaginal septum.1,2 Fusion anomalies (didelphys and bicornuate) can be differentiated from resorption anomalies (septate and arcuate) on ultrasonography (US) by a deep fundal cleft (>1 cm).1 3D US is highly accurate in identifying Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs), it correlates well with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and it is more cost effective and accessible.3 For the didelphys uterus, 3D US obtained coronal to the uterine fundus often demonstrates widely divergent uterine horns separated by a deep serosal fundal cleft (>1 cm) and noncommunicating endometrial cavities with 2 cervices.1 Identifying a duplicated vaginal canal can help differentiate a didelphys uterus from a bicornuate bicollis uterus.1

B) Unicornuate uterus INCORRECT

A unicornuate uterus results from arrested development of one Müllerian duct and normal development of the other. There are 4 different subtypes: no rudimentary horn, rudimentary horn without endometrial cavity, rudimentary horn with communicating endometrial cavity, and rudimentary horn with noncommunicating uterine cavity.1 Renal anomalies, especially renal agenesis when present, are usually ipsilateral to the rudimentary horn.1 On US, unicornuate uterus appears as a lobular oblong (banana-shaped) structure away from the midline. The rudimentary horn is often difficult to identify and, when seen, the presence or absence of endometrium is an important finding.1

C) Partial septate uterus CORRECT

A septate uterus is a result of a resorption anomaly. The septum may be partial (subseptate) or complete secondary to failure of resorption of the uterovaginal septum. A complete septum extends to the external cervical os and occasionally to the vagina.1 US demonstrates interruption of the myometrium by a hypoechoic fibrous septum and/or a muscular septum which is isoechoic to the myometrium and arises midline from the fundus.1 3D US often clearly delineates the septum and improves visualization of the external fundal contour.2 The external fundal contour in septate uterus is convex (little or no serosal fundal cleft) and the apex is greater than 5 mm above the interostial line compared with a bicornuate or didelphys uterus, where the apex is less than 5 mm from the interostial line.1,2 Additionally, the intercornual distance is less than 4 cm.4 A septate uterus with duplicated cervix can appear similar to a bicornuate bicollis uterus and can be correctly diagnosed by evaluating the external fundal contour.1

D) Arcuate uterus INCORRECT

The arcuate uterus also represents a resorption anomaly as a sequela of near-complete resorption of the uterovaginal septum.1 On 3D US, the fundal indentation in an arcuate uterus is well delineated and appears broad based with an obtuse angle at the most central point, which can help differentiate it from a septate uterus that has an acute angle.2,3 Both an arcuate and a septate uterus have a normal external (serosal) fundal contour.2,3 With an arcuate uterus, the length of the vertical measurement from the tubal ostia line, which is drawn horizontally between the tubal ostia to the fundal midline component of the endometrial cavity, is 1 cm or less. With a septate uterus, this vertical distance is greater than 1 cm.

- CambriaBehr SC, Courtier JL, Qayyum A. Imaging of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. RadioGraphics. 2012;32(6):e23.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Diaz D, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomaly and concordance with MRI. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol.Cambria 2010;35(5):593–601.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamed AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

- CambriaChandler TM, Machan LS, Cooperberg PL, Harris AC, Chang SD. MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies: from diagnosis to intervention.Cambria Br J Radiol. 2009;82(984):1034–1042.

- CambriaBehr SC, Courtier JL, Qayyum A. Imaging of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. RadioGraphics. 2012;32(6):e23.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Diaz D, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomaly and concordance with MRI. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol.Cambria 2010;35(5):593–601.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamed AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

- CambriaChandler TM, Machan LS, Cooperberg PL, Harris AC, Chang SD. MMS PGothicüCambriallerian duct anomalies: from diagnosis to intervention.Cambria Br J Radiol. 2009;82(984):1034–1042.

A 29-year-old woman presents to her ObGyn’s office with a history of multiple miscarriages. Transverse pelvic 2D ultrasonography of the uterus (A) and coronal 3D imaging (B) are performed.

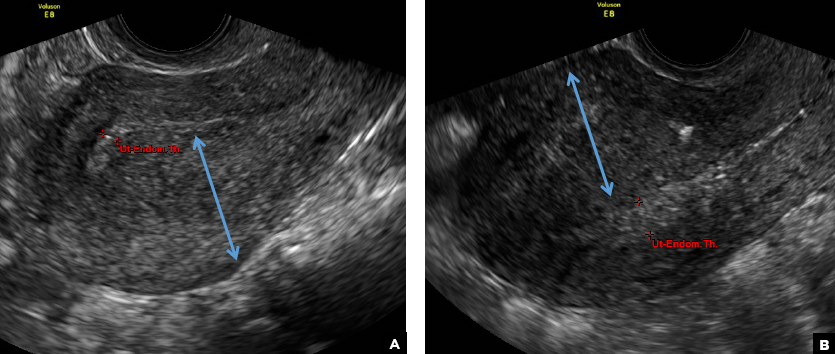

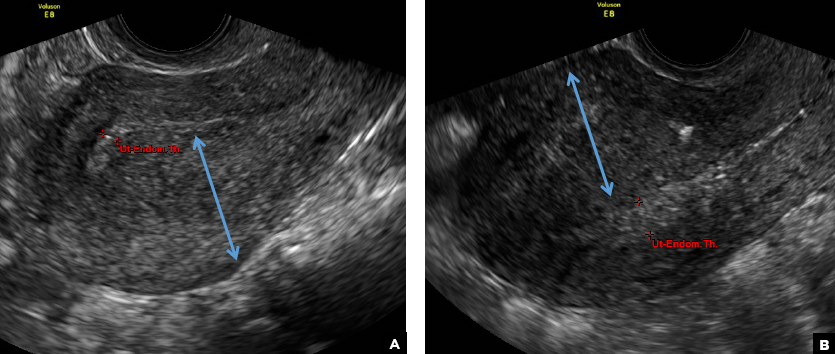

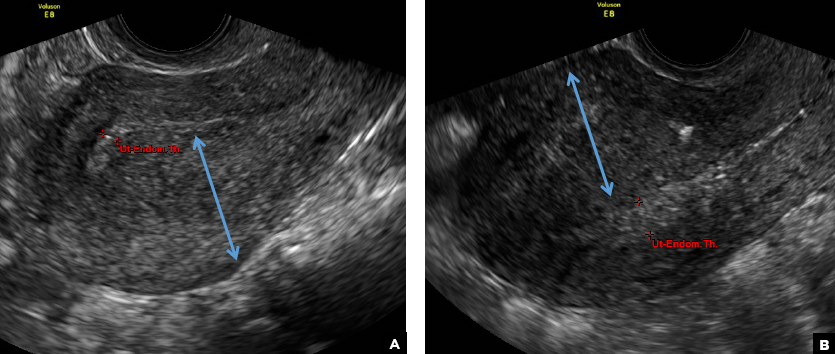

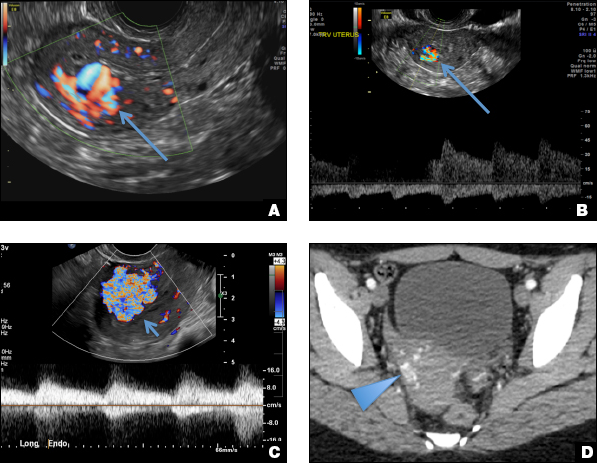

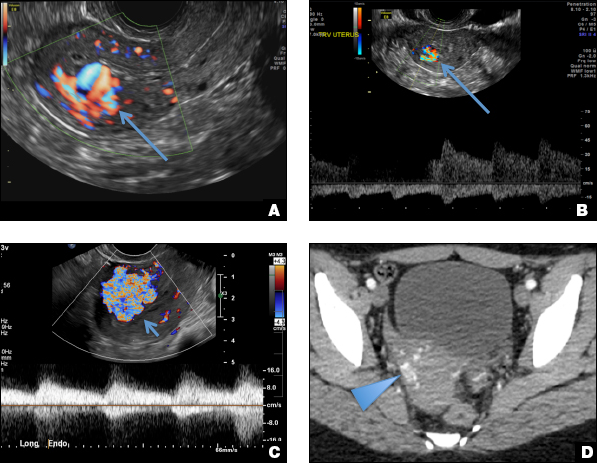

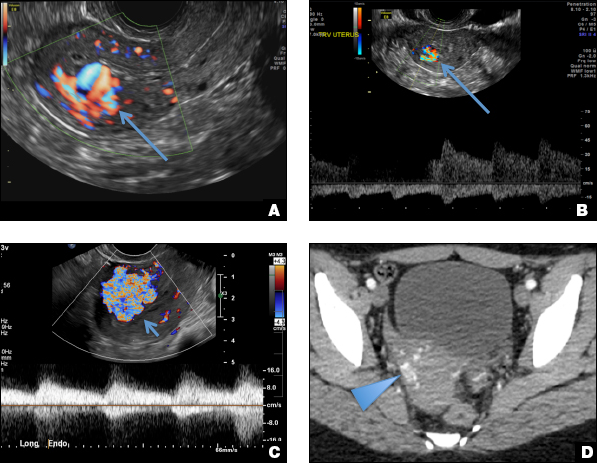

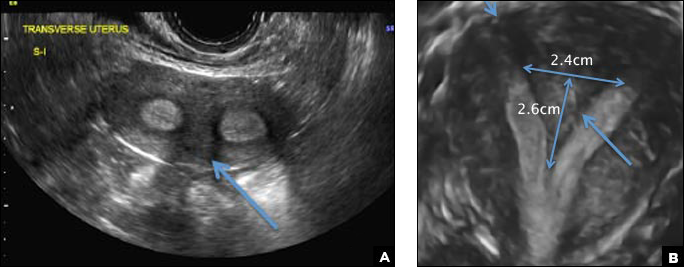

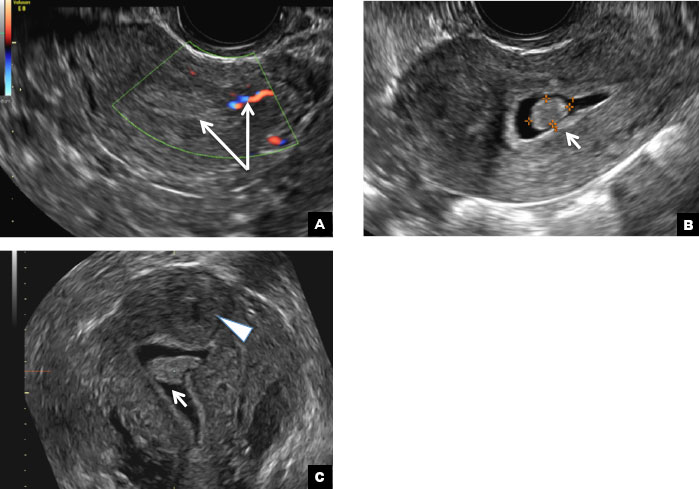

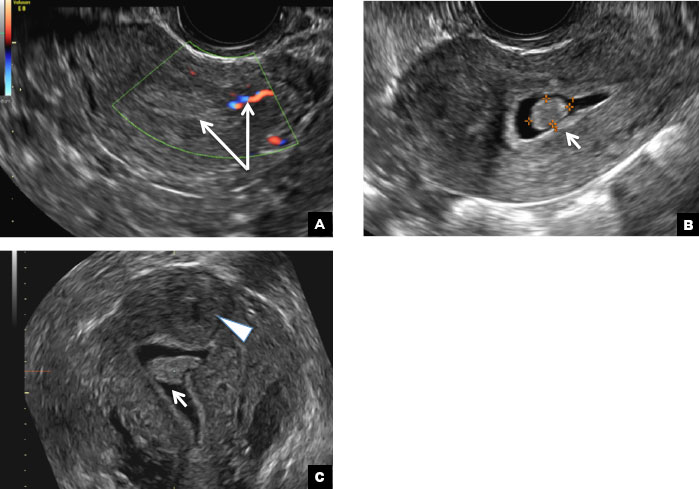

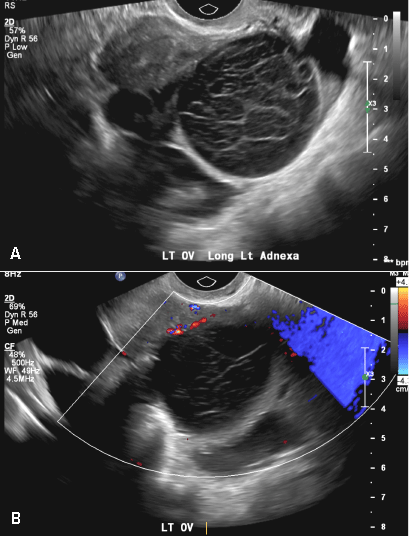

42-year-old woman with abnormal uterine bleeding

A) Endometrial polyp INCORRECT

Endometrial polyps on ultrasonography appear as focal echogenic (hyperechoic) masses or as nonspecific endometrial thickening.1 Color Doppler often demonstrates a vascular stalk, which is a nonspecific finding that also can be seen in submucosal fibroids and endometrial cancer.2 On sonohysterography (SHG), endometrial polyps typically appear as well-defined echogenic/hyperechoic polypoid lesions (tissue appearance similar to that of normal endometrium) protruding into the endometrial canal but still preserving the endometrial−myometrial interface.2,3

B) Submucosal fibroid CORRECT

Submucosal fibroids on ultrasonography appear as heterogeneous hypoechoic lesions distorting the endometrial cavity.1 In contrast to endometrial polyps, which involve the endometrium only, submucosal (intracavitary) fibroids originate in the myometrium, as clarified in Figures 3A & B. SHG demonstrates a broad-based mixed hypoechoic/isoechoic lesion protruding into the endometrial canal but preserving the echogenic endometrium, distinguishing myometrial from endometrial lesions. Submucosal fibroids often distort the endometrial myometrial interface and demonstrate acoustic shadowing.2,3

C) Endometrial carcinoma INCORRECT

Endometrial carcinoma on SHG appears as an irregular inhomogeneous lobulated vascular mass distorting the endometrial−myometrial interface.3 Additionally, irregular frond-like projections can be seen extending from the mass into the endometrial cavity, which are distended with echogenic fluid.2

D) Endometrial hyperplasia INCORRECT

On ultrasonography, endometrial hyperplasia has a nonspecific appearance, often presenting as diffuse smooth endometrial thickening.1 SHG typically demonstrates diffuse thickening of the echogenic endometrial stripe without a focal lesion and, when a focal lesion is present, can mimic a broad-based endometrial polyp.2,3

- Nalaboff KM, Pellerito JS, Ben-Levi E. Imaging the endometrium: disease and normal variants. Radiographics. 2001;21(6):1409-1424.

- Davis PC, O'Neill MJ, Yoder IC, Lee SI, Mueller PR. Sonohysterographic findings of endometrial and subendometrial conditions. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):803- 816.

- Yang T, Pandya A, Marcal L, et al. Sonohysterography: principles, technique and role in diagnosis of endometrial pathology. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):81-87.

A) Endometrial polyp INCORRECT

Endometrial polyps on ultrasonography appear as focal echogenic (hyperechoic) masses or as nonspecific endometrial thickening.1 Color Doppler often demonstrates a vascular stalk, which is a nonspecific finding that also can be seen in submucosal fibroids and endometrial cancer.2 On sonohysterography (SHG), endometrial polyps typically appear as well-defined echogenic/hyperechoic polypoid lesions (tissue appearance similar to that of normal endometrium) protruding into the endometrial canal but still preserving the endometrial−myometrial interface.2,3

B) Submucosal fibroid CORRECT

Submucosal fibroids on ultrasonography appear as heterogeneous hypoechoic lesions distorting the endometrial cavity.1 In contrast to endometrial polyps, which involve the endometrium only, submucosal (intracavitary) fibroids originate in the myometrium, as clarified in Figures 3A & B. SHG demonstrates a broad-based mixed hypoechoic/isoechoic lesion protruding into the endometrial canal but preserving the echogenic endometrium, distinguishing myometrial from endometrial lesions. Submucosal fibroids often distort the endometrial myometrial interface and demonstrate acoustic shadowing.2,3

C) Endometrial carcinoma INCORRECT

Endometrial carcinoma on SHG appears as an irregular inhomogeneous lobulated vascular mass distorting the endometrial−myometrial interface.3 Additionally, irregular frond-like projections can be seen extending from the mass into the endometrial cavity, which are distended with echogenic fluid.2

D) Endometrial hyperplasia INCORRECT

On ultrasonography, endometrial hyperplasia has a nonspecific appearance, often presenting as diffuse smooth endometrial thickening.1 SHG typically demonstrates diffuse thickening of the echogenic endometrial stripe without a focal lesion and, when a focal lesion is present, can mimic a broad-based endometrial polyp.2,3

A) Endometrial polyp INCORRECT

Endometrial polyps on ultrasonography appear as focal echogenic (hyperechoic) masses or as nonspecific endometrial thickening.1 Color Doppler often demonstrates a vascular stalk, which is a nonspecific finding that also can be seen in submucosal fibroids and endometrial cancer.2 On sonohysterography (SHG), endometrial polyps typically appear as well-defined echogenic/hyperechoic polypoid lesions (tissue appearance similar to that of normal endometrium) protruding into the endometrial canal but still preserving the endometrial−myometrial interface.2,3

B) Submucosal fibroid CORRECT

Submucosal fibroids on ultrasonography appear as heterogeneous hypoechoic lesions distorting the endometrial cavity.1 In contrast to endometrial polyps, which involve the endometrium only, submucosal (intracavitary) fibroids originate in the myometrium, as clarified in Figures 3A & B. SHG demonstrates a broad-based mixed hypoechoic/isoechoic lesion protruding into the endometrial canal but preserving the echogenic endometrium, distinguishing myometrial from endometrial lesions. Submucosal fibroids often distort the endometrial myometrial interface and demonstrate acoustic shadowing.2,3

C) Endometrial carcinoma INCORRECT

Endometrial carcinoma on SHG appears as an irregular inhomogeneous lobulated vascular mass distorting the endometrial−myometrial interface.3 Additionally, irregular frond-like projections can be seen extending from the mass into the endometrial cavity, which are distended with echogenic fluid.2

D) Endometrial hyperplasia INCORRECT

On ultrasonography, endometrial hyperplasia has a nonspecific appearance, often presenting as diffuse smooth endometrial thickening.1 SHG typically demonstrates diffuse thickening of the echogenic endometrial stripe without a focal lesion and, when a focal lesion is present, can mimic a broad-based endometrial polyp.2,3

- Nalaboff KM, Pellerito JS, Ben-Levi E. Imaging the endometrium: disease and normal variants. Radiographics. 2001;21(6):1409-1424.

- Davis PC, O'Neill MJ, Yoder IC, Lee SI, Mueller PR. Sonohysterographic findings of endometrial and subendometrial conditions. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):803- 816.

- Yang T, Pandya A, Marcal L, et al. Sonohysterography: principles, technique and role in diagnosis of endometrial pathology. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):81-87.

- Nalaboff KM, Pellerito JS, Ben-Levi E. Imaging the endometrium: disease and normal variants. Radiographics. 2001;21(6):1409-1424.

- Davis PC, O'Neill MJ, Yoder IC, Lee SI, Mueller PR. Sonohysterographic findings of endometrial and subendometrial conditions. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):803- 816.

- Yang T, Pandya A, Marcal L, et al. Sonohysterography: principles, technique and role in diagnosis of endometrial pathology. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):81-87.

A 42-year-old woman presents to her gynecologist's office with abnormal uterine bleeding. Pelvic ultrasonography of the uterus is performed with color Doppler (A) and subsequent sonohysterogram (SHG)/saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) (B). Figures shown above.

More than one-third of tumors found on breast cancer screening represent overdiagnosis

The purpose of screening mammography is to detect tumors when they are small and nonpalpable in order to prevent more advanced breast tumors in women. Overdiagnosis, which leads to unnecessary treatment, refers to screen-detected tumors that will not lead to symptoms. Overdiagnosis cannot be measured directly and, therefore, understanding this concept is problematic for both women and clinicians.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Observations from other types of cancer screening put overdiagnosis in perspective

To help us grasp the overall issue of overdiagnosis, we can consider screening mammography alongside cervical cancer screening and colon cancer screening. For instance, screening with cervical cytology has reduced the incidence of and mortality from invasive cervical cancer.1 Likewise, colonoscopy repeatedly has been found to reduce colon cancer mortality.2,3 Decades of media messaging have emphasized the benefits of screening mammograms.4 However, and in contrast with cervical cytology and colonoscopy, screening mammography has not reduced the incidence of breast cancer presenting with metastatic (advanced) disease.5 Likewise, as the Danish authors of a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine point out, screening mammography has not achieved the promised reduction in breast cancer mortality.

New data from Denmark highlight overdiagnosis concerns

Jørgensen and colleagues conducted a cohort study to estimate the incidence of screen-detected tumors that would not become clinically relevant (overdiagnosis) among women aged 35 to 84 years between 1980 and 2010 in Denmark.6 This country offers a particularly well-suited backdrop for a study of overdiagnosis because biennial screening mammography was introduced by region beginning in the early 1990s. By 2007, one-fifth of the country’s female population aged 50 to 69 years were invited to participate. In the following years, screening became universal for Danish women in this age group.

For the study, researchers identified the size of all invasive breast cancer tumors diagnosed over the study period and then compared the incidence rates of advanced tumors (more than 20-mm in size at detection) with nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened Danish regions. The investigators took into account regional differences not related to screening by assessing the trends in diagnosis of advanced and nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened regions among women older and younger than those screened. This gave them a better estimate of the incidence of overdiagnosis.6

Jørgensen and colleagues found that breast cancer screening resulted in an increase in the incidence of nonadvanced tumors, but that it did not reduce the incidence of advanced tumors. They estimated that 39% of the invasive tumors found among women aged 50 to 69 were overdiagnosed.6

These Danish study results, that more than one-third of screen-detected tumors represent overdiagnosis, are similar to those found for studies conducted in the United States and other countries.7,8 The lengthy follow-up after initiation of screening and the assessment of trends in unscreened women represent strengths of the study by Jørgensen and colleagues, and speak to concerns voiced by those skeptical of reported overdiagnosis incidence rates.9

Although breast cancer mortality is declining, the lion’s share of this decline has resulted from improvements in systemic therapy rather than from screening mammography. Widespread screening mammography has resulted in a scenario in which women are more likely to have a breast cancer that was overdiagnosed than in having earlier detection of a tumor destined to grow larger.5 In the future, by targeting higher-risk women, screening may result in a better benefit:risk ratio. However, and as pointed out by Otis Brawley, MD, Chief Medical and Scientific Officer of the American Cancer Society, we must acknowledge that overdiagnosis is common, the benefits of screening have been overstated, and some patients considered as “cured” from breast cancer have in fact been harmed by unneeded treatment.10

Related article:

No surprises from the USPSTF with new guidance on screening mammography

My breast cancer screening approach

As Brawley indicates, we should not abandon screening.10 I continue to recommend screening based on US Preventive Services Taskforce guidance, beginning biennial screens at age 50.11 I also recognize that some women prefer earlier and more frequent screens, while others may prefer less frequent or even no screening.

- Nieminen P, Kallio M, Hakama M. The effect of mass screening on incidence and mortality of squamous and adenocarcinoma of cervix uteri. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):1017-1021.

- Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(1):1-8.

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, Kliewer EV, Mahmud SM, Bernstein CN. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1128-1137.

- Orenstein P. Our feel-good war on breast cancer. New York Times website. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/magazine/our-feel-good-war-on-breast-cancer.html?pagewanted=all& _r=0. Published April 25, 2013. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- Welch HG, Gorski DH, Albertsen PC. Trends in metastatic breast and prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):596.

- Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, Kalager M, Zahl PH. Breast cancer screening in Denmark: a cohort study of tumor size and overdiagnosis. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 10. doi:10.7326/M16-0270.

- Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1438-1447.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Middleton R, et al. Advanced breast cancer incidence following population-based mammographic screening. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1726-1735.

- Kopans DB. Breast-cancer tumor size and screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(1):93-94.

- Brawley OW. Accepting the existence of breast cancer overdiagnosis [published online ahead of print January 10, 2017]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M16-2850.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727-737.

The purpose of screening mammography is to detect tumors when they are small and nonpalpable in order to prevent more advanced breast tumors in women. Overdiagnosis, which leads to unnecessary treatment, refers to screen-detected tumors that will not lead to symptoms. Overdiagnosis cannot be measured directly and, therefore, understanding this concept is problematic for both women and clinicians.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Observations from other types of cancer screening put overdiagnosis in perspective

To help us grasp the overall issue of overdiagnosis, we can consider screening mammography alongside cervical cancer screening and colon cancer screening. For instance, screening with cervical cytology has reduced the incidence of and mortality from invasive cervical cancer.1 Likewise, colonoscopy repeatedly has been found to reduce colon cancer mortality.2,3 Decades of media messaging have emphasized the benefits of screening mammograms.4 However, and in contrast with cervical cytology and colonoscopy, screening mammography has not reduced the incidence of breast cancer presenting with metastatic (advanced) disease.5 Likewise, as the Danish authors of a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine point out, screening mammography has not achieved the promised reduction in breast cancer mortality.

New data from Denmark highlight overdiagnosis concerns

Jørgensen and colleagues conducted a cohort study to estimate the incidence of screen-detected tumors that would not become clinically relevant (overdiagnosis) among women aged 35 to 84 years between 1980 and 2010 in Denmark.6 This country offers a particularly well-suited backdrop for a study of overdiagnosis because biennial screening mammography was introduced by region beginning in the early 1990s. By 2007, one-fifth of the country’s female population aged 50 to 69 years were invited to participate. In the following years, screening became universal for Danish women in this age group.

For the study, researchers identified the size of all invasive breast cancer tumors diagnosed over the study period and then compared the incidence rates of advanced tumors (more than 20-mm in size at detection) with nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened Danish regions. The investigators took into account regional differences not related to screening by assessing the trends in diagnosis of advanced and nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened regions among women older and younger than those screened. This gave them a better estimate of the incidence of overdiagnosis.6

Jørgensen and colleagues found that breast cancer screening resulted in an increase in the incidence of nonadvanced tumors, but that it did not reduce the incidence of advanced tumors. They estimated that 39% of the invasive tumors found among women aged 50 to 69 were overdiagnosed.6

These Danish study results, that more than one-third of screen-detected tumors represent overdiagnosis, are similar to those found for studies conducted in the United States and other countries.7,8 The lengthy follow-up after initiation of screening and the assessment of trends in unscreened women represent strengths of the study by Jørgensen and colleagues, and speak to concerns voiced by those skeptical of reported overdiagnosis incidence rates.9

Although breast cancer mortality is declining, the lion’s share of this decline has resulted from improvements in systemic therapy rather than from screening mammography. Widespread screening mammography has resulted in a scenario in which women are more likely to have a breast cancer that was overdiagnosed than in having earlier detection of a tumor destined to grow larger.5 In the future, by targeting higher-risk women, screening may result in a better benefit:risk ratio. However, and as pointed out by Otis Brawley, MD, Chief Medical and Scientific Officer of the American Cancer Society, we must acknowledge that overdiagnosis is common, the benefits of screening have been overstated, and some patients considered as “cured” from breast cancer have in fact been harmed by unneeded treatment.10

Related article:

No surprises from the USPSTF with new guidance on screening mammography

My breast cancer screening approach

As Brawley indicates, we should not abandon screening.10 I continue to recommend screening based on US Preventive Services Taskforce guidance, beginning biennial screens at age 50.11 I also recognize that some women prefer earlier and more frequent screens, while others may prefer less frequent or even no screening.

The purpose of screening mammography is to detect tumors when they are small and nonpalpable in order to prevent more advanced breast tumors in women. Overdiagnosis, which leads to unnecessary treatment, refers to screen-detected tumors that will not lead to symptoms. Overdiagnosis cannot be measured directly and, therefore, understanding this concept is problematic for both women and clinicians.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Observations from other types of cancer screening put overdiagnosis in perspective

To help us grasp the overall issue of overdiagnosis, we can consider screening mammography alongside cervical cancer screening and colon cancer screening. For instance, screening with cervical cytology has reduced the incidence of and mortality from invasive cervical cancer.1 Likewise, colonoscopy repeatedly has been found to reduce colon cancer mortality.2,3 Decades of media messaging have emphasized the benefits of screening mammograms.4 However, and in contrast with cervical cytology and colonoscopy, screening mammography has not reduced the incidence of breast cancer presenting with metastatic (advanced) disease.5 Likewise, as the Danish authors of a recent study published in Annals of Internal Medicine point out, screening mammography has not achieved the promised reduction in breast cancer mortality.

New data from Denmark highlight overdiagnosis concerns

Jørgensen and colleagues conducted a cohort study to estimate the incidence of screen-detected tumors that would not become clinically relevant (overdiagnosis) among women aged 35 to 84 years between 1980 and 2010 in Denmark.6 This country offers a particularly well-suited backdrop for a study of overdiagnosis because biennial screening mammography was introduced by region beginning in the early 1990s. By 2007, one-fifth of the country’s female population aged 50 to 69 years were invited to participate. In the following years, screening became universal for Danish women in this age group.

For the study, researchers identified the size of all invasive breast cancer tumors diagnosed over the study period and then compared the incidence rates of advanced tumors (more than 20-mm in size at detection) with nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened Danish regions. The investigators took into account regional differences not related to screening by assessing the trends in diagnosis of advanced and nonadvanced tumors in screened and unscreened regions among women older and younger than those screened. This gave them a better estimate of the incidence of overdiagnosis.6

Jørgensen and colleagues found that breast cancer screening resulted in an increase in the incidence of nonadvanced tumors, but that it did not reduce the incidence of advanced tumors. They estimated that 39% of the invasive tumors found among women aged 50 to 69 were overdiagnosed.6

These Danish study results, that more than one-third of screen-detected tumors represent overdiagnosis, are similar to those found for studies conducted in the United States and other countries.7,8 The lengthy follow-up after initiation of screening and the assessment of trends in unscreened women represent strengths of the study by Jørgensen and colleagues, and speak to concerns voiced by those skeptical of reported overdiagnosis incidence rates.9

Although breast cancer mortality is declining, the lion’s share of this decline has resulted from improvements in systemic therapy rather than from screening mammography. Widespread screening mammography has resulted in a scenario in which women are more likely to have a breast cancer that was overdiagnosed than in having earlier detection of a tumor destined to grow larger.5 In the future, by targeting higher-risk women, screening may result in a better benefit:risk ratio. However, and as pointed out by Otis Brawley, MD, Chief Medical and Scientific Officer of the American Cancer Society, we must acknowledge that overdiagnosis is common, the benefits of screening have been overstated, and some patients considered as “cured” from breast cancer have in fact been harmed by unneeded treatment.10

Related article:

No surprises from the USPSTF with new guidance on screening mammography

My breast cancer screening approach

As Brawley indicates, we should not abandon screening.10 I continue to recommend screening based on US Preventive Services Taskforce guidance, beginning biennial screens at age 50.11 I also recognize that some women prefer earlier and more frequent screens, while others may prefer less frequent or even no screening.

- Nieminen P, Kallio M, Hakama M. The effect of mass screening on incidence and mortality of squamous and adenocarcinoma of cervix uteri. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):1017-1021.

- Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(1):1-8.

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, Kliewer EV, Mahmud SM, Bernstein CN. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1128-1137.

- Orenstein P. Our feel-good war on breast cancer. New York Times website. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/magazine/our-feel-good-war-on-breast-cancer.html?pagewanted=all& _r=0. Published April 25, 2013. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- Welch HG, Gorski DH, Albertsen PC. Trends in metastatic breast and prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):596.

- Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, Kalager M, Zahl PH. Breast cancer screening in Denmark: a cohort study of tumor size and overdiagnosis. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 10. doi:10.7326/M16-0270.

- Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1438-1447.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Middleton R, et al. Advanced breast cancer incidence following population-based mammographic screening. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1726-1735.

- Kopans DB. Breast-cancer tumor size and screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(1):93-94.

- Brawley OW. Accepting the existence of breast cancer overdiagnosis [published online ahead of print January 10, 2017]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M16-2850.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727-737.

- Nieminen P, Kallio M, Hakama M. The effect of mass screening on incidence and mortality of squamous and adenocarcinoma of cervix uteri. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):1017-1021.

- Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(1):1-8.

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, Kliewer EV, Mahmud SM, Bernstein CN. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(4):1128-1137.

- Orenstein P. Our feel-good war on breast cancer. New York Times website. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/magazine/our-feel-good-war-on-breast-cancer.html?pagewanted=all& _r=0. Published April 25, 2013. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- Welch HG, Gorski DH, Albertsen PC. Trends in metastatic breast and prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):596.

- Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, Kalager M, Zahl PH. Breast cancer screening in Denmark: a cohort study of tumor size and overdiagnosis. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 10. doi:10.7326/M16-0270.

- Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1438-1447.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Middleton R, et al. Advanced breast cancer incidence following population-based mammographic screening. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1726-1735.

- Kopans DB. Breast-cancer tumor size and screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(1):93-94.

- Brawley OW. Accepting the existence of breast cancer overdiagnosis [published online ahead of print January 10, 2017]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M16-2850.

- Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727-737.

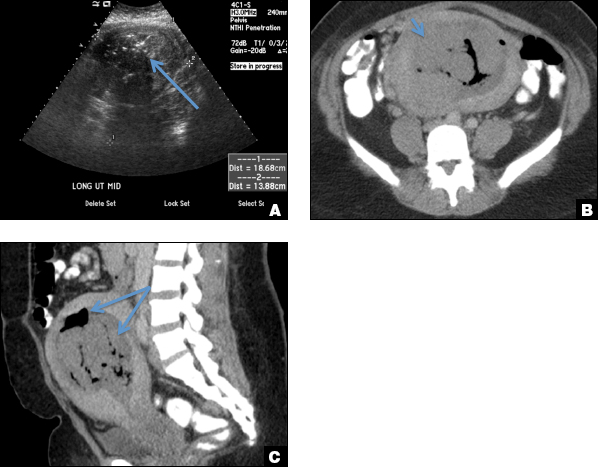

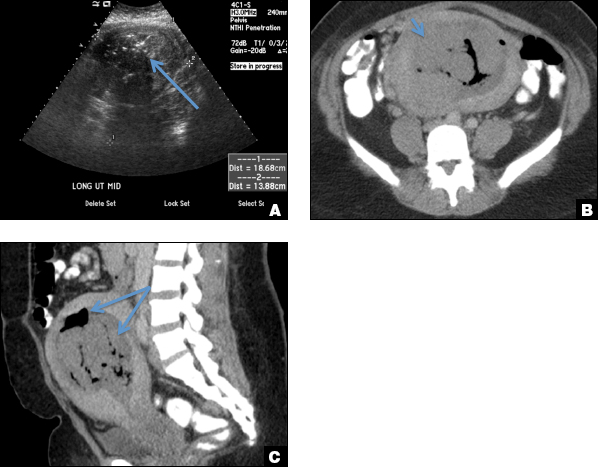

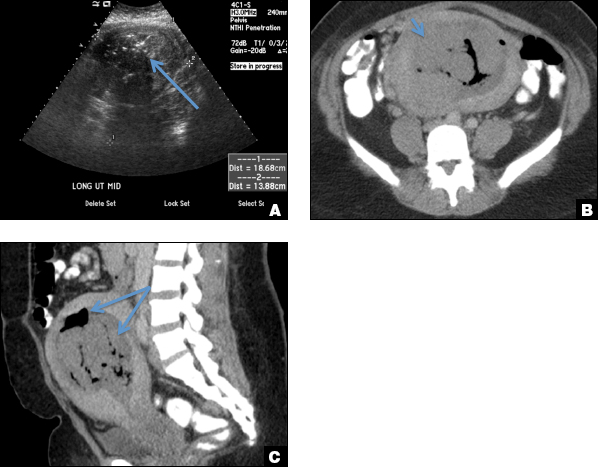

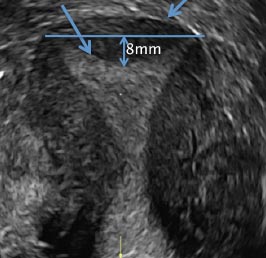

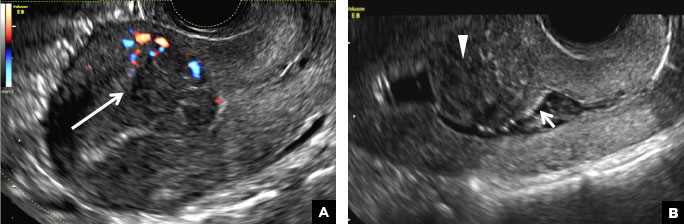

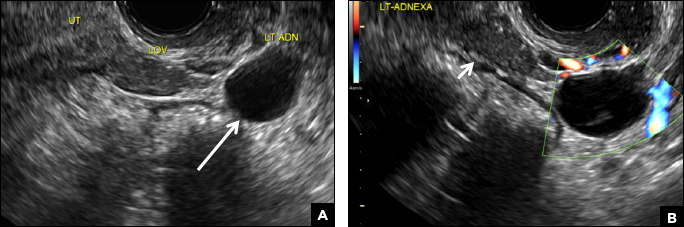

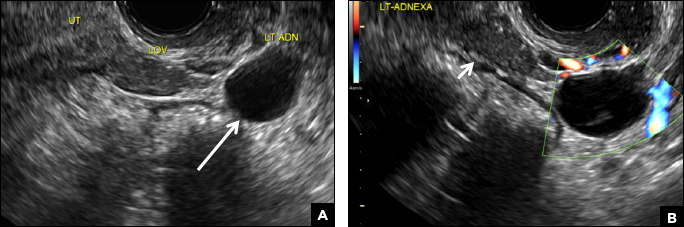

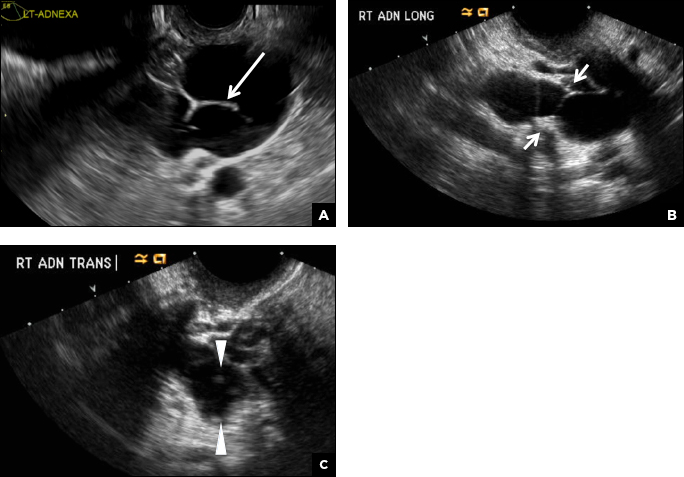

32-year-old woman with pelvic pain and irregular menstrual periods

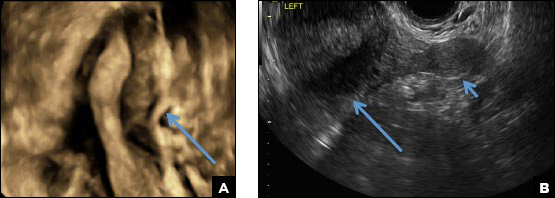

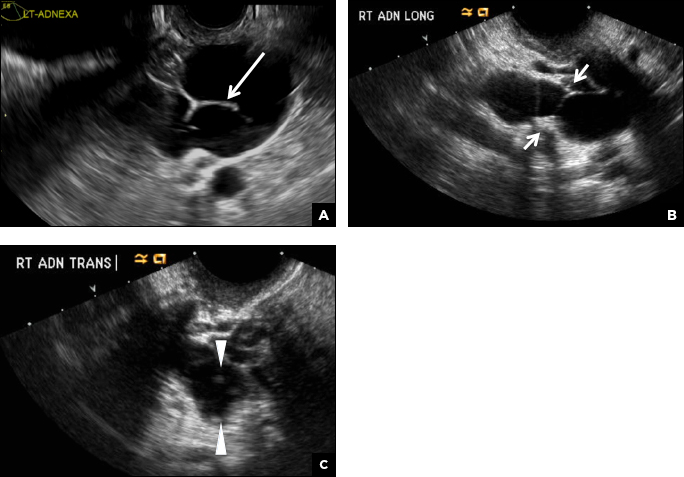

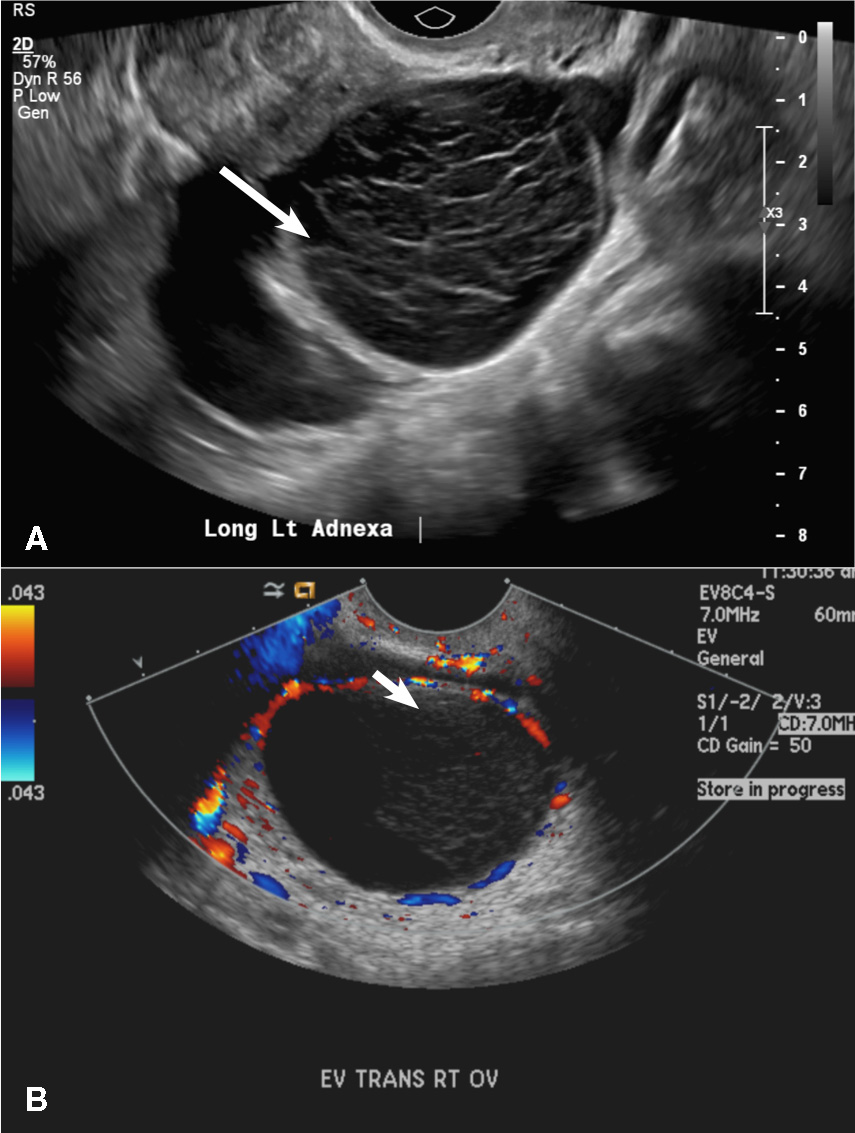

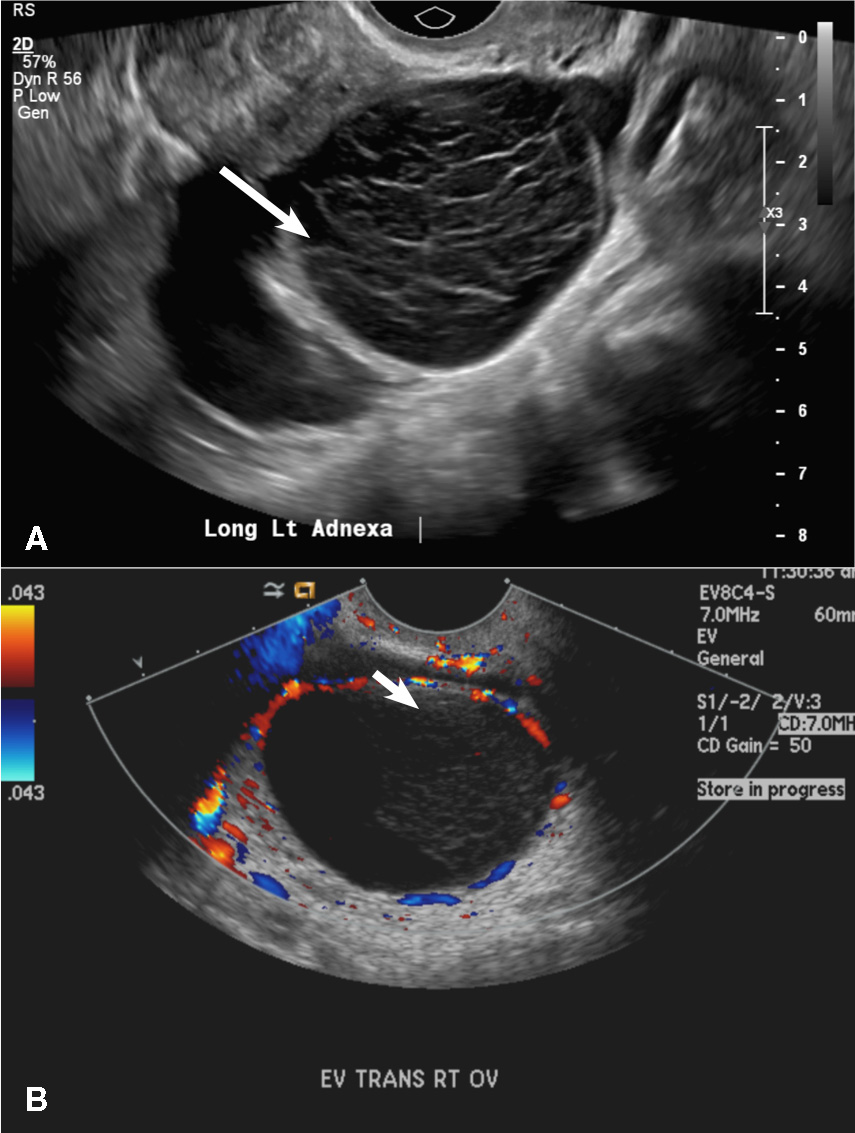

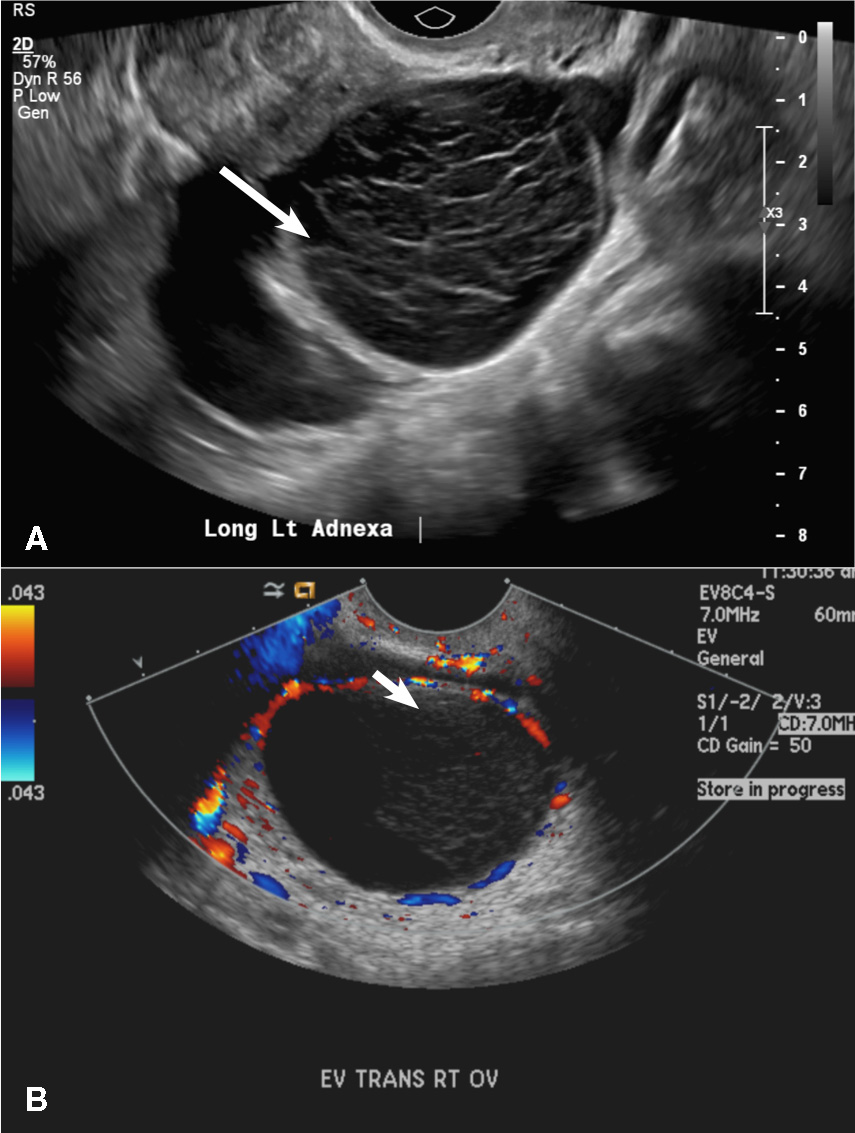

(A) Paratubal cyst CORRECT

Paratubal, or paraovarian, cysts typically are round or oval avascular hypoechoic cysts (long arrow) separate from the adjacent ovary (short arrow). Since they are congenital remnants of the Wolffian duct, they arise from the mesosalpinx, specifically the broad ligament or fallopian tube.1,2 They usually are seen in close proximity to but separate from the ovary without distorting the ovary’s architecture.1,2

B) Hydrosalpinx INCORRECT

A hydrosalpinx appears as an elongated C- or S-shaped, thin-walled tubular serpiginous cystic lesion separate from the ovary. It often has incomplete septations that are infolding of the tube on itself (long arrow).3 Other findings include diametrically opposed indentations (short arrows) of the wall (Waist sign) and short linear mucosal or submucosal folds (arrowhead) that when viewed in cross section appear similar to the spokes of a cogwheel (Cogwheel sign).1–3 Prior tubal infection or gynecologic surgery represent risk factors for hydrosalpinx.

C) Peritoneal inclusion cyst INCORRECT

A peritoneal inclusion cyst appears as an anechoic cystic mass that conforms passively to the shape of the peritoneal cavity/pelvic sidewall (long arrow) and may contain entrapped ovaries (short arrow) within or along the periphery of the fluid collection.1,2 Septations within it are likely from peritoneal adhesions (arrowhead) and may show vascularity.2 Prior (often multiple) gynecologic surgeries represent a risk factor for peritoneal inclusion cysts.

D) Dilated pelvic veins INCORRECT

Dilated pelvic veins appear on sonography as a cluster of elongated and tubular cystic lesions in the adnexa along the broad ligament and demonstrate low level echoes due to sluggish flow (long arrow) and visible red blood cell rouleaux formation. This can be confirmed on color Doppler images (short arrow) and help differentiate it from hydrosalpinx.

- Laing FC, Allison SF. US of the ovary and adnexa: to worry or not to worry? Radiographics. 2012:32(6):1621−1639.

- Moyle PL, Kataoka MY, Nakai A, Takahata A, Reinhold C, Sala E. Nonovarian cystic lesions of the pelvis. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):921−938.

- Rezvani M, Shaaban AM. Fallopian tube disease in the nonpregnant patient. Radiographics. 2011;31(2):527−548.

(A) Paratubal cyst CORRECT

Paratubal, or paraovarian, cysts typically are round or oval avascular hypoechoic cysts (long arrow) separate from the adjacent ovary (short arrow). Since they are congenital remnants of the Wolffian duct, they arise from the mesosalpinx, specifically the broad ligament or fallopian tube.1,2 They usually are seen in close proximity to but separate from the ovary without distorting the ovary’s architecture.1,2

B) Hydrosalpinx INCORRECT

A hydrosalpinx appears as an elongated C- or S-shaped, thin-walled tubular serpiginous cystic lesion separate from the ovary. It often has incomplete septations that are infolding of the tube on itself (long arrow).3 Other findings include diametrically opposed indentations (short arrows) of the wall (Waist sign) and short linear mucosal or submucosal folds (arrowhead) that when viewed in cross section appear similar to the spokes of a cogwheel (Cogwheel sign).1–3 Prior tubal infection or gynecologic surgery represent risk factors for hydrosalpinx.

C) Peritoneal inclusion cyst INCORRECT

A peritoneal inclusion cyst appears as an anechoic cystic mass that conforms passively to the shape of the peritoneal cavity/pelvic sidewall (long arrow) and may contain entrapped ovaries (short arrow) within or along the periphery of the fluid collection.1,2 Septations within it are likely from peritoneal adhesions (arrowhead) and may show vascularity.2 Prior (often multiple) gynecologic surgeries represent a risk factor for peritoneal inclusion cysts.

D) Dilated pelvic veins INCORRECT

Dilated pelvic veins appear on sonography as a cluster of elongated and tubular cystic lesions in the adnexa along the broad ligament and demonstrate low level echoes due to sluggish flow (long arrow) and visible red blood cell rouleaux formation. This can be confirmed on color Doppler images (short arrow) and help differentiate it from hydrosalpinx.

(A) Paratubal cyst CORRECT

Paratubal, or paraovarian, cysts typically are round or oval avascular hypoechoic cysts (long arrow) separate from the adjacent ovary (short arrow). Since they are congenital remnants of the Wolffian duct, they arise from the mesosalpinx, specifically the broad ligament or fallopian tube.1,2 They usually are seen in close proximity to but separate from the ovary without distorting the ovary’s architecture.1,2

B) Hydrosalpinx INCORRECT

A hydrosalpinx appears as an elongated C- or S-shaped, thin-walled tubular serpiginous cystic lesion separate from the ovary. It often has incomplete septations that are infolding of the tube on itself (long arrow).3 Other findings include diametrically opposed indentations (short arrows) of the wall (Waist sign) and short linear mucosal or submucosal folds (arrowhead) that when viewed in cross section appear similar to the spokes of a cogwheel (Cogwheel sign).1–3 Prior tubal infection or gynecologic surgery represent risk factors for hydrosalpinx.

C) Peritoneal inclusion cyst INCORRECT

A peritoneal inclusion cyst appears as an anechoic cystic mass that conforms passively to the shape of the peritoneal cavity/pelvic sidewall (long arrow) and may contain entrapped ovaries (short arrow) within or along the periphery of the fluid collection.1,2 Septations within it are likely from peritoneal adhesions (arrowhead) and may show vascularity.2 Prior (often multiple) gynecologic surgeries represent a risk factor for peritoneal inclusion cysts.

D) Dilated pelvic veins INCORRECT

Dilated pelvic veins appear on sonography as a cluster of elongated and tubular cystic lesions in the adnexa along the broad ligament and demonstrate low level echoes due to sluggish flow (long arrow) and visible red blood cell rouleaux formation. This can be confirmed on color Doppler images (short arrow) and help differentiate it from hydrosalpinx.

- Laing FC, Allison SF. US of the ovary and adnexa: to worry or not to worry? Radiographics. 2012:32(6):1621−1639.

- Moyle PL, Kataoka MY, Nakai A, Takahata A, Reinhold C, Sala E. Nonovarian cystic lesions of the pelvis. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):921−938.

- Rezvani M, Shaaban AM. Fallopian tube disease in the nonpregnant patient. Radiographics. 2011;31(2):527−548.

- Laing FC, Allison SF. US of the ovary and adnexa: to worry or not to worry? Radiographics. 2012:32(6):1621−1639.

- Moyle PL, Kataoka MY, Nakai A, Takahata A, Reinhold C, Sala E. Nonovarian cystic lesions of the pelvis. Radiographics. 2010;30(4):921−938.

- Rezvani M, Shaaban AM. Fallopian tube disease in the nonpregnant patient. Radiographics. 2011;31(2):527−548.

A 32-year-old women presents to her gynecologist’s office reporting pelvic pain and irregular menstrual periods. Results of a urine pregnancy test are negative. Pelvic ultrasonography is performed, with gray scale ( A ) and color Doppler ( B ) images of the left adnexa obtained. Figures shown above.

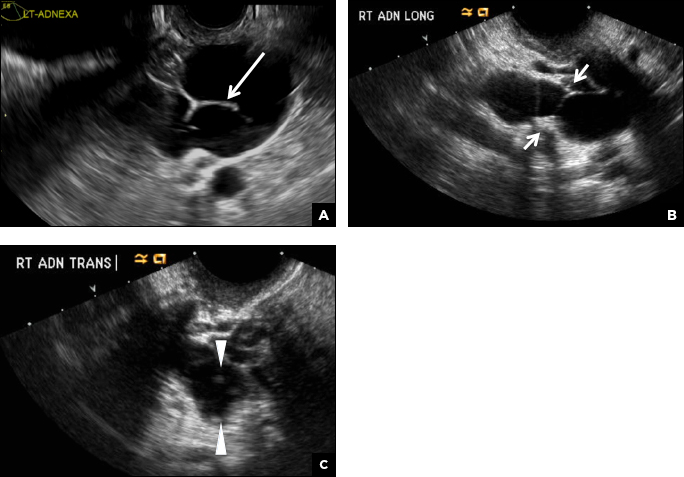

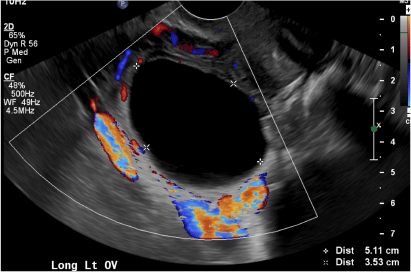

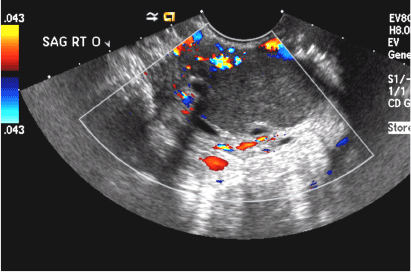

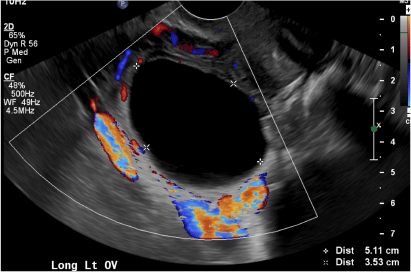

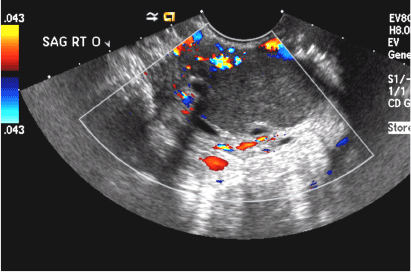

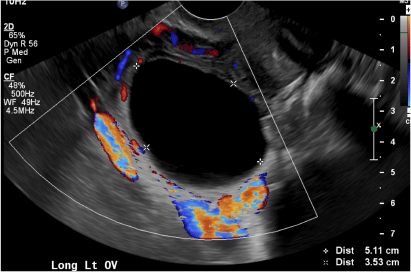

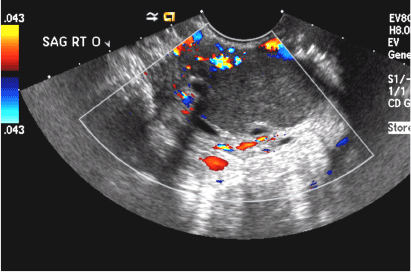

2-week left-sided pelvic pain

(A) Simple ovarian cyst INCORRECT

Here is an example of a well circumscribed round or oval anechoic, avascular simple ovarian cyst with posterior acoustic enhancement and thin smooth walls.1 No septations or solid components are identified.

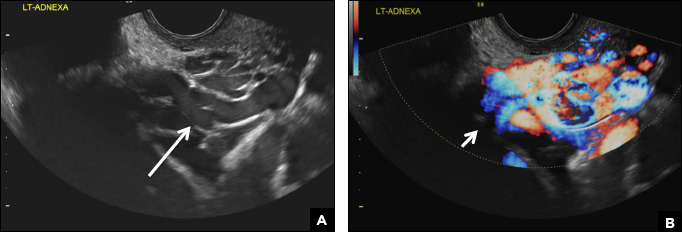

(B) Hemorrhagic cyst CORRECT

This type of cyst is well circumscribed and hypoechoic, with posterior acoustic enhancement and demonstrates a lacy reticular pattern of internal echoes due to fibrin strands (long arrow). The internal echoes also may be solid appearing with concave margins (short arrow) due to retractile hemorrhagic clot.1 The absence of internal vascular flow on color Doppler helps differentiate it from the solid components seen in ovarian neoplasm.

(C) Endometrioma INCORRECT

This mass is a well-circumscribed hypoechoic cyst with homogeneous ground glass or low level echoes and increased through transmission.1 It is also avascular without solid components.

(D) Dermoid INCORRECT

This common benign ovarian tumor has varying appearances. The most common appearance is a cystic lesion with a focal echogenic nodule (long arrow) protruding into the cyst (Rokitansky nodule).2 The second most common appearance is a focal or diffuse hyperechoic mass with areas of acoustic shadowing (arrowhead) from the sebaceous material and hair (tip of the iceberg sign). A third common appearance is a cystic lesion with multiple thin echogenic bands (lines and dots), which are hair floating within the cyst (short arrow). There is no internal vascular flow identified.

(E) Cystic ovarian neoplasm INCORRECT

These are large complex masses with both cystic and solid components demonstrating internal vascular flow. They usually demonstrate a thick irregular wall, multiple septations, and nodular papillary projections.3

- Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology. 2010;256:(3):943−954.

- Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):475−490.

- Wasnik AP, Menias CO, Platt JF, Lalchandani UR, Bedi DG, Elsayes KM. Multimodality imaging of ovarian cystic lesions: review with an imaging based algorithmic approach. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):113−125.

(A) Simple ovarian cyst INCORRECT

Here is an example of a well circumscribed round or oval anechoic, avascular simple ovarian cyst with posterior acoustic enhancement and thin smooth walls.1 No septations or solid components are identified.

(B) Hemorrhagic cyst CORRECT

This type of cyst is well circumscribed and hypoechoic, with posterior acoustic enhancement and demonstrates a lacy reticular pattern of internal echoes due to fibrin strands (long arrow). The internal echoes also may be solid appearing with concave margins (short arrow) due to retractile hemorrhagic clot.1 The absence of internal vascular flow on color Doppler helps differentiate it from the solid components seen in ovarian neoplasm.

(C) Endometrioma INCORRECT

This mass is a well-circumscribed hypoechoic cyst with homogeneous ground glass or low level echoes and increased through transmission.1 It is also avascular without solid components.

(D) Dermoid INCORRECT

This common benign ovarian tumor has varying appearances. The most common appearance is a cystic lesion with a focal echogenic nodule (long arrow) protruding into the cyst (Rokitansky nodule).2 The second most common appearance is a focal or diffuse hyperechoic mass with areas of acoustic shadowing (arrowhead) from the sebaceous material and hair (tip of the iceberg sign). A third common appearance is a cystic lesion with multiple thin echogenic bands (lines and dots), which are hair floating within the cyst (short arrow). There is no internal vascular flow identified.

(E) Cystic ovarian neoplasm INCORRECT

These are large complex masses with both cystic and solid components demonstrating internal vascular flow. They usually demonstrate a thick irregular wall, multiple septations, and nodular papillary projections.3

(A) Simple ovarian cyst INCORRECT

Here is an example of a well circumscribed round or oval anechoic, avascular simple ovarian cyst with posterior acoustic enhancement and thin smooth walls.1 No septations or solid components are identified.

(B) Hemorrhagic cyst CORRECT

This type of cyst is well circumscribed and hypoechoic, with posterior acoustic enhancement and demonstrates a lacy reticular pattern of internal echoes due to fibrin strands (long arrow). The internal echoes also may be solid appearing with concave margins (short arrow) due to retractile hemorrhagic clot.1 The absence of internal vascular flow on color Doppler helps differentiate it from the solid components seen in ovarian neoplasm.

(C) Endometrioma INCORRECT

This mass is a well-circumscribed hypoechoic cyst with homogeneous ground glass or low level echoes and increased through transmission.1 It is also avascular without solid components.

(D) Dermoid INCORRECT

This common benign ovarian tumor has varying appearances. The most common appearance is a cystic lesion with a focal echogenic nodule (long arrow) protruding into the cyst (Rokitansky nodule).2 The second most common appearance is a focal or diffuse hyperechoic mass with areas of acoustic shadowing (arrowhead) from the sebaceous material and hair (tip of the iceberg sign). A third common appearance is a cystic lesion with multiple thin echogenic bands (lines and dots), which are hair floating within the cyst (short arrow). There is no internal vascular flow identified.

(E) Cystic ovarian neoplasm INCORRECT

These are large complex masses with both cystic and solid components demonstrating internal vascular flow. They usually demonstrate a thick irregular wall, multiple septations, and nodular papillary projections.3

- Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology. 2010;256:(3):943−954.

- Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):475−490.

- Wasnik AP, Menias CO, Platt JF, Lalchandani UR, Bedi DG, Elsayes KM. Multimodality imaging of ovarian cystic lesions: review with an imaging based algorithmic approach. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):113−125.

- Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology. 2010;256:(3):943−954.

- Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):475−490.

- Wasnik AP, Menias CO, Platt JF, Lalchandani UR, Bedi DG, Elsayes KM. Multimodality imaging of ovarian cystic lesions: review with an imaging based algorithmic approach. World J Radiol. 2013;5(3):113−125.

A 37-year-old woman presents to the emergency department reporting left-sided pelvic pain for 2 weeks duration. She has a negative urine pregnancy test. Pelvic ultrasonography of the left adnexa is performed with gray scale (A) and color Doppler images (B). Figures shown above.

Focus on treating genital atrophy symptoms

As estrogen levels decline, postmenopausal women commonly experience uncomfortable and distressing symptoms of genital atrophy, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Moreover, aromatase inhibitors (AIs), increasingly used as adjuvant therapy by menopausal breast cancer survivors, contribute to vaginal dryness and sexual pain. This discussion focuses on studies of several local vaginal treatments (including a recently approved agent) that ameliorate GSM symptoms but do not appreciably raise serum sex steroid levels—reassuring data for certain patient populations.

EXPERT COMMENTARY