User login

When is it time to stop hormone therapy?

Extended use of systemic hormone therapy represents one area that clinicians commonly encounter. However, because randomized trial data are not available, helping women make decisions regarding long-term use of hormone therapy is controversial. When it is finalized, the 2016 hormone therapy position statement from the North American Menopause Society will address this topic.

Here I’m referring to the patient who likely started systemic hormone therapy when she was a younger, or more recently menopausal, woman (perhaps in her early 50s), but now she’s in her 60s. In my practice, a patient in this age range would likely be on a lower-than-standard dose of hormone therapy than what she began with originally.

And now the question is, Should she continue, or should she stop, hormone therapy? The median duration of bothersome symptoms is about 10 or 11 years, from the best available data – far longer than what many physicians assume.

And risk stratification also becomes relevant. Let’s say the patient is a slender white or Asian woman with a low body mass index , or she has a parent who had a hip fracture. Continuing low-dose systemic hormone therapy in this case, particularly for osteoporosis prevention when vasomotor symptoms are no longer present, might make sense. However, if the patient is obese, and, therefore has a lower risk for osteoporosis, it may be that ongoing use of systemic hormone therapy would not be indicated, and that patient should be encouraged to discontinue at that point.

Also, if a uterus is not present – and we’re talking only about estrogen therapy, given its greater safety profile with long-term use with respect to breast cancer – clinicians and women can be more comfortable with continued use of low-dose systemic hormone therapy for osteoporosis prevention. If a uterus is present, then women making decisions about long-term use of hormone therapy need to be aware of the small, but I believe real, elevated risk of breast cancer. With each office visit and when decisions about refilling prescriptions or continuing hormone therapy are made, this is an important issue to discuss, particularly if there’s an intact uterus. These discussions also need to be documented in the record.

What about the route of estrogen? Age, BMI, and oral estrogen therapy each represent independent risk factors for venous thromboembolism. For older, as well as obese menopausal women, who are candidates for systemic hormone therapy, I prefer transdermal over oral estrogen therapy.

Finally, I counsel women that although vasomotor symptoms/hot flashes improve as women age, the same is not true for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM, also known as genital atrophy). If vaginal dryness, pain with sex, or other manifestations of GSM occur in women tapering their dose of systemic hormone therapy or in women who have discontinued systemic hormone therapy, initiation and long-term use of low-dose vaginal estrogen should be considered.

References

1. Menopause. 2014 Jun;21(6):679-81.

Dr. Kaunitz is a professor and associate chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida in Jacksonville. He is on the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society. He reports being a consultant or on the advisory board or review panel of several pharmaceutical companies, and receiving grant support from several pharmaceutical companies. He receives royalties from UpToDate.

Extended use of systemic hormone therapy represents one area that clinicians commonly encounter. However, because randomized trial data are not available, helping women make decisions regarding long-term use of hormone therapy is controversial. When it is finalized, the 2016 hormone therapy position statement from the North American Menopause Society will address this topic.

Here I’m referring to the patient who likely started systemic hormone therapy when she was a younger, or more recently menopausal, woman (perhaps in her early 50s), but now she’s in her 60s. In my practice, a patient in this age range would likely be on a lower-than-standard dose of hormone therapy than what she began with originally.

And now the question is, Should she continue, or should she stop, hormone therapy? The median duration of bothersome symptoms is about 10 or 11 years, from the best available data – far longer than what many physicians assume.

And risk stratification also becomes relevant. Let’s say the patient is a slender white or Asian woman with a low body mass index , or she has a parent who had a hip fracture. Continuing low-dose systemic hormone therapy in this case, particularly for osteoporosis prevention when vasomotor symptoms are no longer present, might make sense. However, if the patient is obese, and, therefore has a lower risk for osteoporosis, it may be that ongoing use of systemic hormone therapy would not be indicated, and that patient should be encouraged to discontinue at that point.

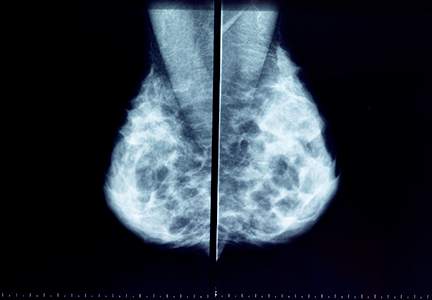

Also, if a uterus is not present – and we’re talking only about estrogen therapy, given its greater safety profile with long-term use with respect to breast cancer – clinicians and women can be more comfortable with continued use of low-dose systemic hormone therapy for osteoporosis prevention. If a uterus is present, then women making decisions about long-term use of hormone therapy need to be aware of the small, but I believe real, elevated risk of breast cancer. With each office visit and when decisions about refilling prescriptions or continuing hormone therapy are made, this is an important issue to discuss, particularly if there’s an intact uterus. These discussions also need to be documented in the record.

What about the route of estrogen? Age, BMI, and oral estrogen therapy each represent independent risk factors for venous thromboembolism. For older, as well as obese menopausal women, who are candidates for systemic hormone therapy, I prefer transdermal over oral estrogen therapy.

Finally, I counsel women that although vasomotor symptoms/hot flashes improve as women age, the same is not true for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM, also known as genital atrophy). If vaginal dryness, pain with sex, or other manifestations of GSM occur in women tapering their dose of systemic hormone therapy or in women who have discontinued systemic hormone therapy, initiation and long-term use of low-dose vaginal estrogen should be considered.

References

1. Menopause. 2014 Jun;21(6):679-81.

Dr. Kaunitz is a professor and associate chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida in Jacksonville. He is on the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society. He reports being a consultant or on the advisory board or review panel of several pharmaceutical companies, and receiving grant support from several pharmaceutical companies. He receives royalties from UpToDate.

Extended use of systemic hormone therapy represents one area that clinicians commonly encounter. However, because randomized trial data are not available, helping women make decisions regarding long-term use of hormone therapy is controversial. When it is finalized, the 2016 hormone therapy position statement from the North American Menopause Society will address this topic.

Here I’m referring to the patient who likely started systemic hormone therapy when she was a younger, or more recently menopausal, woman (perhaps in her early 50s), but now she’s in her 60s. In my practice, a patient in this age range would likely be on a lower-than-standard dose of hormone therapy than what she began with originally.

And now the question is, Should she continue, or should she stop, hormone therapy? The median duration of bothersome symptoms is about 10 or 11 years, from the best available data – far longer than what many physicians assume.

And risk stratification also becomes relevant. Let’s say the patient is a slender white or Asian woman with a low body mass index , or she has a parent who had a hip fracture. Continuing low-dose systemic hormone therapy in this case, particularly for osteoporosis prevention when vasomotor symptoms are no longer present, might make sense. However, if the patient is obese, and, therefore has a lower risk for osteoporosis, it may be that ongoing use of systemic hormone therapy would not be indicated, and that patient should be encouraged to discontinue at that point.

Also, if a uterus is not present – and we’re talking only about estrogen therapy, given its greater safety profile with long-term use with respect to breast cancer – clinicians and women can be more comfortable with continued use of low-dose systemic hormone therapy for osteoporosis prevention. If a uterus is present, then women making decisions about long-term use of hormone therapy need to be aware of the small, but I believe real, elevated risk of breast cancer. With each office visit and when decisions about refilling prescriptions or continuing hormone therapy are made, this is an important issue to discuss, particularly if there’s an intact uterus. These discussions also need to be documented in the record.

What about the route of estrogen? Age, BMI, and oral estrogen therapy each represent independent risk factors for venous thromboembolism. For older, as well as obese menopausal women, who are candidates for systemic hormone therapy, I prefer transdermal over oral estrogen therapy.

Finally, I counsel women that although vasomotor symptoms/hot flashes improve as women age, the same is not true for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM, also known as genital atrophy). If vaginal dryness, pain with sex, or other manifestations of GSM occur in women tapering their dose of systemic hormone therapy or in women who have discontinued systemic hormone therapy, initiation and long-term use of low-dose vaginal estrogen should be considered.

References

1. Menopause. 2014 Jun;21(6):679-81.

Dr. Kaunitz is a professor and associate chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida in Jacksonville. He is on the board of trustees of the North American Menopause Society. He reports being a consultant or on the advisory board or review panel of several pharmaceutical companies, and receiving grant support from several pharmaceutical companies. He receives royalties from UpToDate.

2016 Update on menopause

In this Update, I discuss important new study results regarding the cardiovascular safety of hormone therapy (HT) in early menopausal women. In addition, I review survey data that reveal a huge number of US women are using compounded HT preparations, which have unproven efficacy and safety.

Earlier initiation is better: ELITE trial provides strong support for the estrogen timing hypothesis

Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

Keaney JF, Solomon G. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and atherosclerosis--time is of the essence [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1279-1280.

A substantial amount of published data, including from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), supports the timing hypothesis, which proposes that HT slows the progression of atherosclerosis among recently menopausal women but has a neutral or adverse effect among women who are a decade or more past menopause onset.1 To directly test this hypothesis, Hodis and colleagues randomly assigned healthy postmenopausal women (<6 years or ≥10 years past menopause) without cardiovascular disease (CVD) to oral estradiol 1 mg or placebo. Women with a uterus also were randomly assigned to receive either vaginal progesterone gel or placebo gel. The primary outcome was the rate of change in carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), which was assessed at baseline and each 6 months of the study. (An earlier report had noted that baseline CIMT correlated well with CVD risk factors.2) Coronary artery atherosclerosis, a secondary outcome, was assessed at study completion using computed tomography (CT).

Details of the study

Among the 643 participants in the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE), the median years since menopause and the median age at enrollment were 3.5 and 55.4, respectively, in the early postmenopause group and 14.3 and 63.6, respectively, in the late postmenopause group.

Among the younger women, after a median of 5 years of study medications, the estradiol group had less progression of CIMT than the placebo group (P = .008). By contrast, in the older group, rates of CIMT progression were similar in the HT and placebo groups (P = .29). The relationship between estrogen and CIMT progression differed significantly between the younger and older groups (P = .007). Use of progesterone did not change these trends. Coronary artery CT parameters did not differ significantly between the placebo and HT groups in the age group or in the time-since-menopause group.

What this evidence means for practice

In an editorial accompanying the published results of the ELITE trial, Keaney and Solomon concluded that, although estrogen had a favorable effect on atherosclerosis in early menopause, it would be premature to recommend HT for prevention of cardiovascular events. I agree with them, but I also would like to note that the use of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms has plummeted since the initial WHI findings in 2002, with infrequent HT use even among symptomatic women in early menopause.3 (And I refer you to the special inset featuring JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH) The takeaway message is that this important new clinical trial provides additional reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when initiated by recently menopausal women to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms. This message represents welcome news for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms considering use of HT.

A word about the vaginal progesterone gel used in the ELITE trial in relation to clinical practice: Given the need for vaginal placement of progesterone gel, potential messiness, and high cost, few clinicians may prescribe this formulation, and few women probably would choose to use it. As an alternative, micronized progesterone 100-mg capsules are less expensive and well accepted by most patients. These capsules are formulated with peanut oil. Because they may cause women to feel drowsy, the capsules should be taken at bedtime. In women with an intact uterus who are taking oral estradiol 1-mg tablets, one appropriate progestogen regimen for endometrial suppression is a 100-mg micronized progesterone capsule each night, continuously.

WHI, ELITE and the timing hypothesis:

New evidence on HT in early menopause is reassuring

Q&A with JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH

In this interview, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses the reassuring results of recent hormone therapy (HT) trials in early versus later postmenopausal women, examines these outcomes in the context of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial and ELITE trial, and debunks an enduring common misconception about the WHI.

Q You have said for several years that there has been a misconception about the WHI trial. What is that misconception, and what has been its impact on clinicians, women, and the use of HT?

A The WHI HT trial has been largely misunderstood. It was designed to address the balance of benefits and risks of long-term HT for the prevention of chronic disease in postmenopausal women across a broad range of ages (average age 63).1,2 It was not intended to evaluate the clinical role of HT for managing menopausal symptoms in young and early menopausal women.3 Overall, the WHI study findings have been inappropriately extrapolated to women in their 40s and early 50s who report distressing hot flashes, night sweats, and other menopausal symptoms, and they are often used as a reason to deny therapy when in fact many of these women would be appropriate candidates for HT.

There is increasing evidence that younger women in early menopause who are taking HT have a lower risk of adverse outcomes and lower absolute risks of disease than older women.2,3 In younger, early menopausal women with bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, or other menopausal symptoms and who have no contraindications to HT, the benefits of treatment are likely to outweigh the risks, and these patients derive quality-of-life benefits from treatment.

Q How do the results of the recent ELITE (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) trial build on cardiovascular safety, in particular, of HT and when HT is optimally initiated?

A The ELITE trial directly tested the "timing hypothesis" and the role of HT in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis in early menopause (defined as within 6 years of menopause onset) compared with the effect in women in later menopause (defined as at least 10 yearspast menopause).4 The investigators used carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate end point. In this trial, 643 women were randomly assigned according to whether they were in early or later menopause to receive either placebo or estradiol 1 mg daily; women with a uterus also received progesterone 45 mg as a 4% vaginal gel or matching placebo gel. The median duration of intervention was 5 years.

The ELITE study results provide support for the "critical window hypothesis" in that the estradiol-treated younger women closer to onset of menopause had slowing of atherosclerosis compared with the placebo group, while the older women more distant from menopause did not have slowing of atherosclerosis with estradiol.

The ELITE trial was not large enough, however, to assess clinical end points--rates of heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular events. So it remains unclear whether the findings for the surrogate end point of CIMT would translate into a reduced risk of clinical events in the younger women. Nevertheless, ELITE does provide more reassurance about the use of HT in early menopause and supports the possibility that the overall results of the WHI among women enrolled at an average age of 63 years may not apply directly to younger women in early menopause.

Q What impact on clinical practice do you anticipate as a result of the ELITE trial results?

A The findings provide further support for the timing hypothesis and offer additional reassurance regarding the safety of HT in early menopause for management of menopausal symptoms. However, the trial does not provide conclusive evidence to support recommendations to use HT for the express purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD), even if HT is started in early menopause. Using a surrogate end point for atherosclerosis (CIMT) is not the same as looking at clinical events. There are many biologic pathways for heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular events. In addition to atherosclerosis, for example, there is thrombosis, clotting, thrombo-occlusion within a blood vessel, and plaque rupture. Again, we do not know whether the CIMT-based results would translate directly into a reduction in clinical heart attacks and stroke.

The main takeaway point from the ELITE trial results is further reassurance for use of HT for management of menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but not for long-term chronic disease prevention at any age.

Q Another recent study, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses HT and the timing hypothesis but in this instance relating to glucose tolerance.5 What did these study authors find?

A This study by Pereira and colleagues is very interesting and suggests that the window of opportunity for initiating estrogen therapy may apply not only to coronary events but also to glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes risk.5

The authors investigated the effects of short-term high-dose transdermal estradiol on the insulin-mediated glucose disposal rate (GDR), which is a measure of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Participants in this randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled study included 22 women who were in early menopause (6 years or less since final menses) and 24 women who were in later menopause (10 years or longer since final menses). All of the women were naïve to hormone therapy, and baseline GDR did not differ between groups. After 1 week of treatment with transdermal estradiol (a high dose of 150 μg) or placebo, the participants' GDR was measured via a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp.

The investigators found that in the younger women, estradiol had a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and GDR, whereas in the older women, there was no evidence of a favorable effect and, in fact, there was a signal for risk and more adverse findings in this group.

Several studies in the WHI also looked at glucose tolerance and at the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes. While the results of the WHI estrogen-alone trial revealed a reduction in diabetes and favorable effects across age groups, in the WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial we did see a signal that the results for diabetes may have been more favorable in the younger than in the older women, somewhat consistent with the findings of Pereira and colleagues.2,5

Overall this issue requires more research, but the Pereira study provides further support for the possibility that estrogen's metabolic effects may vary by age and time since menopause, and there is evidence that the estrogen receptors may be more functional and more sensitive in early rather than later menopause. These findings are very interesting and consistent with the overall hypothesis about the importance of age and time since menopause in relation to estrogen action. Again, they offer further support for use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but they should not be interpreted as endorsing the use of HT to prevent either diabetes or CVD, due to the potential for other risks.

Q Where would you like to see future research conducted regarding the timing hypothesis?

A I would like to see more research on the role of oral versus transdermal estrogen in relation to insulin sensitivity, diabetes risk, and CVD risk, and more research on the role of estrogen dose, different types of progestogens, and the benefits and risks of novel formulations, including selective estrogen receptor modulators and tissue selective estrogen complexes.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women's Health at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. She is a past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and a NAMS Certified Menopause Practitioner.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-333.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013(13);310:1353-1368.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management-- getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):803-806.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

- Pereira RI, Casey BA, Swibas TA, Erickson CB, Wolfe P, Van Pelt RE. Timing of estradiol treatment after menopause may determine benefit or harm to insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4456-4462.

FDA-approved HT is preferable to compounded HT formulations

Pinkerton JV, Santoro N. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US women. Menopause. 2015;22(9):926-936.

Pinkerton JV, Constantine GD. Compounded non-FDA-approved menopausal hormone therapy prescriptions have increased: results of a pharmacy survey. Menopause. 2016;23(4):359-367.

Gass ML, Stuenkel CA, Utian WH, LaCroix A, Liu JH, Shifren JL.; North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Advisory Panel consisting of representatives of NAMS Board of Trustees and other experts in women's health. Use of compounded hormone therapy in the United States: report of The North American Menopause Society Survey. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1276-1284.

Consider how you would manage this clinical scenario: During a well-woman visit, your 54-year-old patient mentions that, after seeing an advertisement on television, she visited a clinic that sells compounded hormones. There, she underwent some testing and received an estrogen-testosterone implant and a progesterone cream that she applies to her skin each night to treat her menopausal symptoms. Now what?

The use of HT for menopausal symptoms declined considerably following the 2002 publication of the initial findings from the WHI, and its use remains low.4 Symptomatic menopausal women often find that their physicians are reluctant to consider prescribing treatment for menopausal symptoms because of safety concerns regarding HT use. Further, confusion about HT safety has opened the door to the increasing use of compounded bioidentical HT formulations, which are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3 Since the publication of my 2015 Update on menopause (OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):37−40,42−43), several reports have addressed the use of "custom compounded" bioidentical menopausal HT in US women.

Millions use compounded HT for menopausal symptoms

A recent study by Pinkerton and Santoro that analyzed data from 2 national surveys suggested that as many as 2.5 million US women currently use non−FDA-approved custom-compounded HT. The authors also found that more than three-quarters of women using compounded HT are unaware that these medications, which include oral, topical, injectable, and implantable (pellet) formulations, are not FDA approved. In a study by Pinkerton and Constantine, total annual sales of compounded HT were estimated at approximately $1.5 billion. The dramatic growth in the use of compounded HT appears to have stemmed from celebrity endorsements, aggressive and unregulated marketing, and beliefs about the safety of "natural" hormones.5

Spurious laboratory testing. Women seeking care from physicians and clinics that provide compounded HT are often advised to undergo saliva and serum testing to determine hormone levels. Many women are unaware, however, that saliva testing does not correlate with serum levels of hormones. Further, in contrast with conditions such as thyroid disease and diabetes, routine laboratory testing is neither indicated nor helpful in the management of menopausal symptoms.6 Of note, insurance companies often do not reimburse for the cost of saliva hormone testing or for non-FDA-approved hormones.5

Inadequate endometrial protection. Topical progesterone cream, which is not absorbed in sufficient quantities to generate therapeutic effects, is often prescribed by practitioners who sell bioidentical compounded hormones to their patients.7 According to a report by the North American Menopause Society, several cases of endometrial cancer have been reported among women using compounded HT. These cases may reflect use of systemic estrogen without adequate progesterone protection, as could occur when topical progesterone cream is prescribed to women with an intact uterus using systemic estrogen therapy.

What this evidence means for practice

Clinicians should be alert to the growing prevalence of use of compounded HT and should educate themselves and their patients about the differences between non−FDA-approved HT and FDA-approved HT. Further, women interested in using "natural," "bioidentical," or "custom compounded" HT should be aware that FDA-approved estradiol (oral, transdermal, and vaginal) and progesterone (oral and vaginal) formulations are available.

Because the FDA does not test custom compounded hormones for efficacy or safety and the standardization and purity of these products are uncertain, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has stated that FDA-approved HT is preferred for management of menopausal symptoms.8 Similarly, the North American Menopause Society does not recommend the use of compounded HT for treatment of menopausal symptoms unless a patient is allergic to ingredients contained in FDA-approved HT formulations.9

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015;22(4):391–401.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):803–806.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333.

- Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check? Menopause. 2015;22(9):919–920.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):859–876.

- Benster B, Carey A, Wadsworth F, Vashisht A, Domoney C, Studd J. A double-blind placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effect of progestelle progesterone cream on postmenopausal women. Menopause Int. 2009;15(2):63–69.

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

In this Update, I discuss important new study results regarding the cardiovascular safety of hormone therapy (HT) in early menopausal women. In addition, I review survey data that reveal a huge number of US women are using compounded HT preparations, which have unproven efficacy and safety.

Earlier initiation is better: ELITE trial provides strong support for the estrogen timing hypothesis

Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

Keaney JF, Solomon G. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and atherosclerosis--time is of the essence [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1279-1280.

A substantial amount of published data, including from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), supports the timing hypothesis, which proposes that HT slows the progression of atherosclerosis among recently menopausal women but has a neutral or adverse effect among women who are a decade or more past menopause onset.1 To directly test this hypothesis, Hodis and colleagues randomly assigned healthy postmenopausal women (<6 years or ≥10 years past menopause) without cardiovascular disease (CVD) to oral estradiol 1 mg or placebo. Women with a uterus also were randomly assigned to receive either vaginal progesterone gel or placebo gel. The primary outcome was the rate of change in carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), which was assessed at baseline and each 6 months of the study. (An earlier report had noted that baseline CIMT correlated well with CVD risk factors.2) Coronary artery atherosclerosis, a secondary outcome, was assessed at study completion using computed tomography (CT).

Details of the study

Among the 643 participants in the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE), the median years since menopause and the median age at enrollment were 3.5 and 55.4, respectively, in the early postmenopause group and 14.3 and 63.6, respectively, in the late postmenopause group.

Among the younger women, after a median of 5 years of study medications, the estradiol group had less progression of CIMT than the placebo group (P = .008). By contrast, in the older group, rates of CIMT progression were similar in the HT and placebo groups (P = .29). The relationship between estrogen and CIMT progression differed significantly between the younger and older groups (P = .007). Use of progesterone did not change these trends. Coronary artery CT parameters did not differ significantly between the placebo and HT groups in the age group or in the time-since-menopause group.

What this evidence means for practice

In an editorial accompanying the published results of the ELITE trial, Keaney and Solomon concluded that, although estrogen had a favorable effect on atherosclerosis in early menopause, it would be premature to recommend HT for prevention of cardiovascular events. I agree with them, but I also would like to note that the use of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms has plummeted since the initial WHI findings in 2002, with infrequent HT use even among symptomatic women in early menopause.3 (And I refer you to the special inset featuring JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH) The takeaway message is that this important new clinical trial provides additional reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when initiated by recently menopausal women to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms. This message represents welcome news for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms considering use of HT.

A word about the vaginal progesterone gel used in the ELITE trial in relation to clinical practice: Given the need for vaginal placement of progesterone gel, potential messiness, and high cost, few clinicians may prescribe this formulation, and few women probably would choose to use it. As an alternative, micronized progesterone 100-mg capsules are less expensive and well accepted by most patients. These capsules are formulated with peanut oil. Because they may cause women to feel drowsy, the capsules should be taken at bedtime. In women with an intact uterus who are taking oral estradiol 1-mg tablets, one appropriate progestogen regimen for endometrial suppression is a 100-mg micronized progesterone capsule each night, continuously.

WHI, ELITE and the timing hypothesis:

New evidence on HT in early menopause is reassuring

Q&A with JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH

In this interview, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses the reassuring results of recent hormone therapy (HT) trials in early versus later postmenopausal women, examines these outcomes in the context of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial and ELITE trial, and debunks an enduring common misconception about the WHI.

Q You have said for several years that there has been a misconception about the WHI trial. What is that misconception, and what has been its impact on clinicians, women, and the use of HT?

A The WHI HT trial has been largely misunderstood. It was designed to address the balance of benefits and risks of long-term HT for the prevention of chronic disease in postmenopausal women across a broad range of ages (average age 63).1,2 It was not intended to evaluate the clinical role of HT for managing menopausal symptoms in young and early menopausal women.3 Overall, the WHI study findings have been inappropriately extrapolated to women in their 40s and early 50s who report distressing hot flashes, night sweats, and other menopausal symptoms, and they are often used as a reason to deny therapy when in fact many of these women would be appropriate candidates for HT.

There is increasing evidence that younger women in early menopause who are taking HT have a lower risk of adverse outcomes and lower absolute risks of disease than older women.2,3 In younger, early menopausal women with bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, or other menopausal symptoms and who have no contraindications to HT, the benefits of treatment are likely to outweigh the risks, and these patients derive quality-of-life benefits from treatment.

Q How do the results of the recent ELITE (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) trial build on cardiovascular safety, in particular, of HT and when HT is optimally initiated?

A The ELITE trial directly tested the "timing hypothesis" and the role of HT in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis in early menopause (defined as within 6 years of menopause onset) compared with the effect in women in later menopause (defined as at least 10 yearspast menopause).4 The investigators used carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate end point. In this trial, 643 women were randomly assigned according to whether they were in early or later menopause to receive either placebo or estradiol 1 mg daily; women with a uterus also received progesterone 45 mg as a 4% vaginal gel or matching placebo gel. The median duration of intervention was 5 years.

The ELITE study results provide support for the "critical window hypothesis" in that the estradiol-treated younger women closer to onset of menopause had slowing of atherosclerosis compared with the placebo group, while the older women more distant from menopause did not have slowing of atherosclerosis with estradiol.

The ELITE trial was not large enough, however, to assess clinical end points--rates of heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular events. So it remains unclear whether the findings for the surrogate end point of CIMT would translate into a reduced risk of clinical events in the younger women. Nevertheless, ELITE does provide more reassurance about the use of HT in early menopause and supports the possibility that the overall results of the WHI among women enrolled at an average age of 63 years may not apply directly to younger women in early menopause.

Q What impact on clinical practice do you anticipate as a result of the ELITE trial results?

A The findings provide further support for the timing hypothesis and offer additional reassurance regarding the safety of HT in early menopause for management of menopausal symptoms. However, the trial does not provide conclusive evidence to support recommendations to use HT for the express purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD), even if HT is started in early menopause. Using a surrogate end point for atherosclerosis (CIMT) is not the same as looking at clinical events. There are many biologic pathways for heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular events. In addition to atherosclerosis, for example, there is thrombosis, clotting, thrombo-occlusion within a blood vessel, and plaque rupture. Again, we do not know whether the CIMT-based results would translate directly into a reduction in clinical heart attacks and stroke.

The main takeaway point from the ELITE trial results is further reassurance for use of HT for management of menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but not for long-term chronic disease prevention at any age.

Q Another recent study, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses HT and the timing hypothesis but in this instance relating to glucose tolerance.5 What did these study authors find?

A This study by Pereira and colleagues is very interesting and suggests that the window of opportunity for initiating estrogen therapy may apply not only to coronary events but also to glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes risk.5

The authors investigated the effects of short-term high-dose transdermal estradiol on the insulin-mediated glucose disposal rate (GDR), which is a measure of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Participants in this randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled study included 22 women who were in early menopause (6 years or less since final menses) and 24 women who were in later menopause (10 years or longer since final menses). All of the women were naïve to hormone therapy, and baseline GDR did not differ between groups. After 1 week of treatment with transdermal estradiol (a high dose of 150 μg) or placebo, the participants' GDR was measured via a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp.

The investigators found that in the younger women, estradiol had a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and GDR, whereas in the older women, there was no evidence of a favorable effect and, in fact, there was a signal for risk and more adverse findings in this group.

Several studies in the WHI also looked at glucose tolerance and at the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes. While the results of the WHI estrogen-alone trial revealed a reduction in diabetes and favorable effects across age groups, in the WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial we did see a signal that the results for diabetes may have been more favorable in the younger than in the older women, somewhat consistent with the findings of Pereira and colleagues.2,5

Overall this issue requires more research, but the Pereira study provides further support for the possibility that estrogen's metabolic effects may vary by age and time since menopause, and there is evidence that the estrogen receptors may be more functional and more sensitive in early rather than later menopause. These findings are very interesting and consistent with the overall hypothesis about the importance of age and time since menopause in relation to estrogen action. Again, they offer further support for use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but they should not be interpreted as endorsing the use of HT to prevent either diabetes or CVD, due to the potential for other risks.

Q Where would you like to see future research conducted regarding the timing hypothesis?

A I would like to see more research on the role of oral versus transdermal estrogen in relation to insulin sensitivity, diabetes risk, and CVD risk, and more research on the role of estrogen dose, different types of progestogens, and the benefits and risks of novel formulations, including selective estrogen receptor modulators and tissue selective estrogen complexes.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women's Health at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. She is a past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and a NAMS Certified Menopause Practitioner.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-333.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013(13);310:1353-1368.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management-- getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):803-806.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

- Pereira RI, Casey BA, Swibas TA, Erickson CB, Wolfe P, Van Pelt RE. Timing of estradiol treatment after menopause may determine benefit or harm to insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4456-4462.

FDA-approved HT is preferable to compounded HT formulations

Pinkerton JV, Santoro N. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US women. Menopause. 2015;22(9):926-936.

Pinkerton JV, Constantine GD. Compounded non-FDA-approved menopausal hormone therapy prescriptions have increased: results of a pharmacy survey. Menopause. 2016;23(4):359-367.

Gass ML, Stuenkel CA, Utian WH, LaCroix A, Liu JH, Shifren JL.; North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Advisory Panel consisting of representatives of NAMS Board of Trustees and other experts in women's health. Use of compounded hormone therapy in the United States: report of The North American Menopause Society Survey. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1276-1284.

Consider how you would manage this clinical scenario: During a well-woman visit, your 54-year-old patient mentions that, after seeing an advertisement on television, she visited a clinic that sells compounded hormones. There, she underwent some testing and received an estrogen-testosterone implant and a progesterone cream that she applies to her skin each night to treat her menopausal symptoms. Now what?

The use of HT for menopausal symptoms declined considerably following the 2002 publication of the initial findings from the WHI, and its use remains low.4 Symptomatic menopausal women often find that their physicians are reluctant to consider prescribing treatment for menopausal symptoms because of safety concerns regarding HT use. Further, confusion about HT safety has opened the door to the increasing use of compounded bioidentical HT formulations, which are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3 Since the publication of my 2015 Update on menopause (OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):37−40,42−43), several reports have addressed the use of "custom compounded" bioidentical menopausal HT in US women.

Millions use compounded HT for menopausal symptoms

A recent study by Pinkerton and Santoro that analyzed data from 2 national surveys suggested that as many as 2.5 million US women currently use non−FDA-approved custom-compounded HT. The authors also found that more than three-quarters of women using compounded HT are unaware that these medications, which include oral, topical, injectable, and implantable (pellet) formulations, are not FDA approved. In a study by Pinkerton and Constantine, total annual sales of compounded HT were estimated at approximately $1.5 billion. The dramatic growth in the use of compounded HT appears to have stemmed from celebrity endorsements, aggressive and unregulated marketing, and beliefs about the safety of "natural" hormones.5

Spurious laboratory testing. Women seeking care from physicians and clinics that provide compounded HT are often advised to undergo saliva and serum testing to determine hormone levels. Many women are unaware, however, that saliva testing does not correlate with serum levels of hormones. Further, in contrast with conditions such as thyroid disease and diabetes, routine laboratory testing is neither indicated nor helpful in the management of menopausal symptoms.6 Of note, insurance companies often do not reimburse for the cost of saliva hormone testing or for non-FDA-approved hormones.5

Inadequate endometrial protection. Topical progesterone cream, which is not absorbed in sufficient quantities to generate therapeutic effects, is often prescribed by practitioners who sell bioidentical compounded hormones to their patients.7 According to a report by the North American Menopause Society, several cases of endometrial cancer have been reported among women using compounded HT. These cases may reflect use of systemic estrogen without adequate progesterone protection, as could occur when topical progesterone cream is prescribed to women with an intact uterus using systemic estrogen therapy.

What this evidence means for practice

Clinicians should be alert to the growing prevalence of use of compounded HT and should educate themselves and their patients about the differences between non−FDA-approved HT and FDA-approved HT. Further, women interested in using "natural," "bioidentical," or "custom compounded" HT should be aware that FDA-approved estradiol (oral, transdermal, and vaginal) and progesterone (oral and vaginal) formulations are available.

Because the FDA does not test custom compounded hormones for efficacy or safety and the standardization and purity of these products are uncertain, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has stated that FDA-approved HT is preferred for management of menopausal symptoms.8 Similarly, the North American Menopause Society does not recommend the use of compounded HT for treatment of menopausal symptoms unless a patient is allergic to ingredients contained in FDA-approved HT formulations.9

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this Update, I discuss important new study results regarding the cardiovascular safety of hormone therapy (HT) in early menopausal women. In addition, I review survey data that reveal a huge number of US women are using compounded HT preparations, which have unproven efficacy and safety.

Earlier initiation is better: ELITE trial provides strong support for the estrogen timing hypothesis

Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

Keaney JF, Solomon G. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and atherosclerosis--time is of the essence [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1279-1280.

A substantial amount of published data, including from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), supports the timing hypothesis, which proposes that HT slows the progression of atherosclerosis among recently menopausal women but has a neutral or adverse effect among women who are a decade or more past menopause onset.1 To directly test this hypothesis, Hodis and colleagues randomly assigned healthy postmenopausal women (<6 years or ≥10 years past menopause) without cardiovascular disease (CVD) to oral estradiol 1 mg or placebo. Women with a uterus also were randomly assigned to receive either vaginal progesterone gel or placebo gel. The primary outcome was the rate of change in carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), which was assessed at baseline and each 6 months of the study. (An earlier report had noted that baseline CIMT correlated well with CVD risk factors.2) Coronary artery atherosclerosis, a secondary outcome, was assessed at study completion using computed tomography (CT).

Details of the study

Among the 643 participants in the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE), the median years since menopause and the median age at enrollment were 3.5 and 55.4, respectively, in the early postmenopause group and 14.3 and 63.6, respectively, in the late postmenopause group.

Among the younger women, after a median of 5 years of study medications, the estradiol group had less progression of CIMT than the placebo group (P = .008). By contrast, in the older group, rates of CIMT progression were similar in the HT and placebo groups (P = .29). The relationship between estrogen and CIMT progression differed significantly between the younger and older groups (P = .007). Use of progesterone did not change these trends. Coronary artery CT parameters did not differ significantly between the placebo and HT groups in the age group or in the time-since-menopause group.

What this evidence means for practice

In an editorial accompanying the published results of the ELITE trial, Keaney and Solomon concluded that, although estrogen had a favorable effect on atherosclerosis in early menopause, it would be premature to recommend HT for prevention of cardiovascular events. I agree with them, but I also would like to note that the use of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms has plummeted since the initial WHI findings in 2002, with infrequent HT use even among symptomatic women in early menopause.3 (And I refer you to the special inset featuring JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH) The takeaway message is that this important new clinical trial provides additional reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when initiated by recently menopausal women to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms. This message represents welcome news for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms considering use of HT.

A word about the vaginal progesterone gel used in the ELITE trial in relation to clinical practice: Given the need for vaginal placement of progesterone gel, potential messiness, and high cost, few clinicians may prescribe this formulation, and few women probably would choose to use it. As an alternative, micronized progesterone 100-mg capsules are less expensive and well accepted by most patients. These capsules are formulated with peanut oil. Because they may cause women to feel drowsy, the capsules should be taken at bedtime. In women with an intact uterus who are taking oral estradiol 1-mg tablets, one appropriate progestogen regimen for endometrial suppression is a 100-mg micronized progesterone capsule each night, continuously.

WHI, ELITE and the timing hypothesis:

New evidence on HT in early menopause is reassuring

Q&A with JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH

In this interview, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses the reassuring results of recent hormone therapy (HT) trials in early versus later postmenopausal women, examines these outcomes in the context of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial and ELITE trial, and debunks an enduring common misconception about the WHI.

Q You have said for several years that there has been a misconception about the WHI trial. What is that misconception, and what has been its impact on clinicians, women, and the use of HT?

A The WHI HT trial has been largely misunderstood. It was designed to address the balance of benefits and risks of long-term HT for the prevention of chronic disease in postmenopausal women across a broad range of ages (average age 63).1,2 It was not intended to evaluate the clinical role of HT for managing menopausal symptoms in young and early menopausal women.3 Overall, the WHI study findings have been inappropriately extrapolated to women in their 40s and early 50s who report distressing hot flashes, night sweats, and other menopausal symptoms, and they are often used as a reason to deny therapy when in fact many of these women would be appropriate candidates for HT.

There is increasing evidence that younger women in early menopause who are taking HT have a lower risk of adverse outcomes and lower absolute risks of disease than older women.2,3 In younger, early menopausal women with bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, or other menopausal symptoms and who have no contraindications to HT, the benefits of treatment are likely to outweigh the risks, and these patients derive quality-of-life benefits from treatment.

Q How do the results of the recent ELITE (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) trial build on cardiovascular safety, in particular, of HT and when HT is optimally initiated?

A The ELITE trial directly tested the "timing hypothesis" and the role of HT in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis in early menopause (defined as within 6 years of menopause onset) compared with the effect in women in later menopause (defined as at least 10 yearspast menopause).4 The investigators used carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate end point. In this trial, 643 women were randomly assigned according to whether they were in early or later menopause to receive either placebo or estradiol 1 mg daily; women with a uterus also received progesterone 45 mg as a 4% vaginal gel or matching placebo gel. The median duration of intervention was 5 years.

The ELITE study results provide support for the "critical window hypothesis" in that the estradiol-treated younger women closer to onset of menopause had slowing of atherosclerosis compared with the placebo group, while the older women more distant from menopause did not have slowing of atherosclerosis with estradiol.

The ELITE trial was not large enough, however, to assess clinical end points--rates of heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular events. So it remains unclear whether the findings for the surrogate end point of CIMT would translate into a reduced risk of clinical events in the younger women. Nevertheless, ELITE does provide more reassurance about the use of HT in early menopause and supports the possibility that the overall results of the WHI among women enrolled at an average age of 63 years may not apply directly to younger women in early menopause.

Q What impact on clinical practice do you anticipate as a result of the ELITE trial results?

A The findings provide further support for the timing hypothesis and offer additional reassurance regarding the safety of HT in early menopause for management of menopausal symptoms. However, the trial does not provide conclusive evidence to support recommendations to use HT for the express purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD), even if HT is started in early menopause. Using a surrogate end point for atherosclerosis (CIMT) is not the same as looking at clinical events. There are many biologic pathways for heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular events. In addition to atherosclerosis, for example, there is thrombosis, clotting, thrombo-occlusion within a blood vessel, and plaque rupture. Again, we do not know whether the CIMT-based results would translate directly into a reduction in clinical heart attacks and stroke.

The main takeaway point from the ELITE trial results is further reassurance for use of HT for management of menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but not for long-term chronic disease prevention at any age.

Q Another recent study, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses HT and the timing hypothesis but in this instance relating to glucose tolerance.5 What did these study authors find?

A This study by Pereira and colleagues is very interesting and suggests that the window of opportunity for initiating estrogen therapy may apply not only to coronary events but also to glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes risk.5

The authors investigated the effects of short-term high-dose transdermal estradiol on the insulin-mediated glucose disposal rate (GDR), which is a measure of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Participants in this randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled study included 22 women who were in early menopause (6 years or less since final menses) and 24 women who were in later menopause (10 years or longer since final menses). All of the women were naïve to hormone therapy, and baseline GDR did not differ between groups. After 1 week of treatment with transdermal estradiol (a high dose of 150 μg) or placebo, the participants' GDR was measured via a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp.

The investigators found that in the younger women, estradiol had a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and GDR, whereas in the older women, there was no evidence of a favorable effect and, in fact, there was a signal for risk and more adverse findings in this group.

Several studies in the WHI also looked at glucose tolerance and at the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes. While the results of the WHI estrogen-alone trial revealed a reduction in diabetes and favorable effects across age groups, in the WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial we did see a signal that the results for diabetes may have been more favorable in the younger than in the older women, somewhat consistent with the findings of Pereira and colleagues.2,5

Overall this issue requires more research, but the Pereira study provides further support for the possibility that estrogen's metabolic effects may vary by age and time since menopause, and there is evidence that the estrogen receptors may be more functional and more sensitive in early rather than later menopause. These findings are very interesting and consistent with the overall hypothesis about the importance of age and time since menopause in relation to estrogen action. Again, they offer further support for use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but they should not be interpreted as endorsing the use of HT to prevent either diabetes or CVD, due to the potential for other risks.

Q Where would you like to see future research conducted regarding the timing hypothesis?

A I would like to see more research on the role of oral versus transdermal estrogen in relation to insulin sensitivity, diabetes risk, and CVD risk, and more research on the role of estrogen dose, different types of progestogens, and the benefits and risks of novel formulations, including selective estrogen receptor modulators and tissue selective estrogen complexes.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women's Health at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. She is a past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and a NAMS Certified Menopause Practitioner.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-333.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013(13);310:1353-1368.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management-- getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):803-806.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

- Pereira RI, Casey BA, Swibas TA, Erickson CB, Wolfe P, Van Pelt RE. Timing of estradiol treatment after menopause may determine benefit or harm to insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4456-4462.

FDA-approved HT is preferable to compounded HT formulations

Pinkerton JV, Santoro N. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US women. Menopause. 2015;22(9):926-936.

Pinkerton JV, Constantine GD. Compounded non-FDA-approved menopausal hormone therapy prescriptions have increased: results of a pharmacy survey. Menopause. 2016;23(4):359-367.

Gass ML, Stuenkel CA, Utian WH, LaCroix A, Liu JH, Shifren JL.; North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Advisory Panel consisting of representatives of NAMS Board of Trustees and other experts in women's health. Use of compounded hormone therapy in the United States: report of The North American Menopause Society Survey. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1276-1284.

Consider how you would manage this clinical scenario: During a well-woman visit, your 54-year-old patient mentions that, after seeing an advertisement on television, she visited a clinic that sells compounded hormones. There, she underwent some testing and received an estrogen-testosterone implant and a progesterone cream that she applies to her skin each night to treat her menopausal symptoms. Now what?

The use of HT for menopausal symptoms declined considerably following the 2002 publication of the initial findings from the WHI, and its use remains low.4 Symptomatic menopausal women often find that their physicians are reluctant to consider prescribing treatment for menopausal symptoms because of safety concerns regarding HT use. Further, confusion about HT safety has opened the door to the increasing use of compounded bioidentical HT formulations, which are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3 Since the publication of my 2015 Update on menopause (OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):37−40,42−43), several reports have addressed the use of "custom compounded" bioidentical menopausal HT in US women.

Millions use compounded HT for menopausal symptoms

A recent study by Pinkerton and Santoro that analyzed data from 2 national surveys suggested that as many as 2.5 million US women currently use non−FDA-approved custom-compounded HT. The authors also found that more than three-quarters of women using compounded HT are unaware that these medications, which include oral, topical, injectable, and implantable (pellet) formulations, are not FDA approved. In a study by Pinkerton and Constantine, total annual sales of compounded HT were estimated at approximately $1.5 billion. The dramatic growth in the use of compounded HT appears to have stemmed from celebrity endorsements, aggressive and unregulated marketing, and beliefs about the safety of "natural" hormones.5

Spurious laboratory testing. Women seeking care from physicians and clinics that provide compounded HT are often advised to undergo saliva and serum testing to determine hormone levels. Many women are unaware, however, that saliva testing does not correlate with serum levels of hormones. Further, in contrast with conditions such as thyroid disease and diabetes, routine laboratory testing is neither indicated nor helpful in the management of menopausal symptoms.6 Of note, insurance companies often do not reimburse for the cost of saliva hormone testing or for non-FDA-approved hormones.5

Inadequate endometrial protection. Topical progesterone cream, which is not absorbed in sufficient quantities to generate therapeutic effects, is often prescribed by practitioners who sell bioidentical compounded hormones to their patients.7 According to a report by the North American Menopause Society, several cases of endometrial cancer have been reported among women using compounded HT. These cases may reflect use of systemic estrogen without adequate progesterone protection, as could occur when topical progesterone cream is prescribed to women with an intact uterus using systemic estrogen therapy.

What this evidence means for practice

Clinicians should be alert to the growing prevalence of use of compounded HT and should educate themselves and their patients about the differences between non−FDA-approved HT and FDA-approved HT. Further, women interested in using "natural," "bioidentical," or "custom compounded" HT should be aware that FDA-approved estradiol (oral, transdermal, and vaginal) and progesterone (oral and vaginal) formulations are available.

Because the FDA does not test custom compounded hormones for efficacy or safety and the standardization and purity of these products are uncertain, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has stated that FDA-approved HT is preferred for management of menopausal symptoms.8 Similarly, the North American Menopause Society does not recommend the use of compounded HT for treatment of menopausal symptoms unless a patient is allergic to ingredients contained in FDA-approved HT formulations.9

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015;22(4):391–401.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):803–806.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333.

- Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check? Menopause. 2015;22(9):919–920.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):859–876.

- Benster B, Carey A, Wadsworth F, Vashisht A, Domoney C, Studd J. A double-blind placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effect of progestelle progesterone cream on postmenopausal women. Menopause Int. 2009;15(2):63–69.

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015;22(4):391–401.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):803–806.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333.

- Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check? Menopause. 2015;22(9):919–920.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):859–876.

- Benster B, Carey A, Wadsworth F, Vashisht A, Domoney C, Studd J. A double-blind placebo-controlled study to evaluate the effect of progestelle progesterone cream on postmenopausal women. Menopause Int. 2009;15(2):63–69.

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

In this article

• JoAnn E. Manson discusses new data on HT benefits vs risks

• Use of compounded hormones growing

How gynecologic procedures and pharmacologic treatments can affect the uterus

Transvaginal ultrasound: We are gaining a better understanding of its clinical applications

Steven R. Goldstein, MD

In my first book I coined the phrase "sonomicroscopy." We are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) that you could not see with your naked eye even if you could it hold it at arms length and squint at it. For instance, cardiac activity can be seen easily within an embryo of 4 mm at 47 days since the last menstrual period. If there were any possible way to hold this 4-mm embryo in your hand, you would not appreciate cardiac pulsations contained within it! This is one of the beauties, and yet potential foibles, of TVUS.

In this excellent pictorial article, Michelle Stalnaker Ozcan, MD, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, have done an outstanding job of turning this low-power "sonomicroscope" into the uterus to better understand a number of unique yet important clinical applications of TVUS.

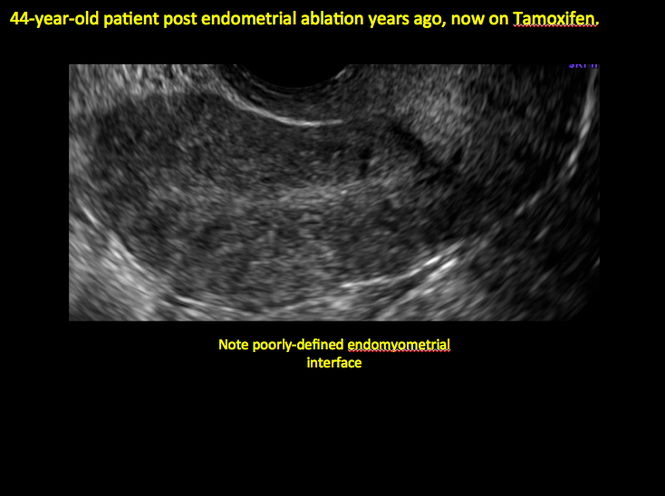

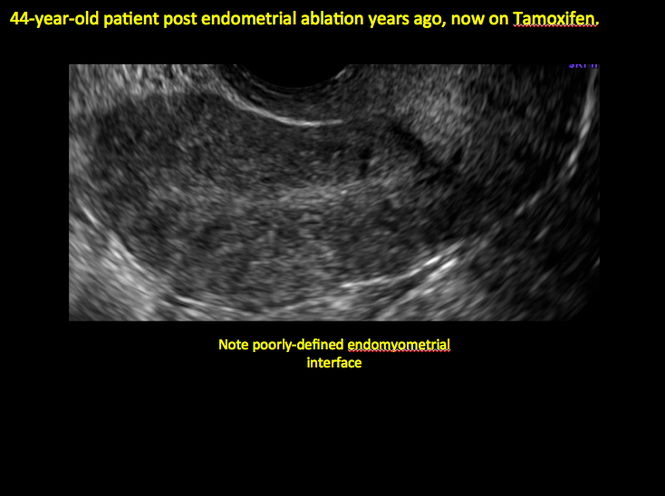

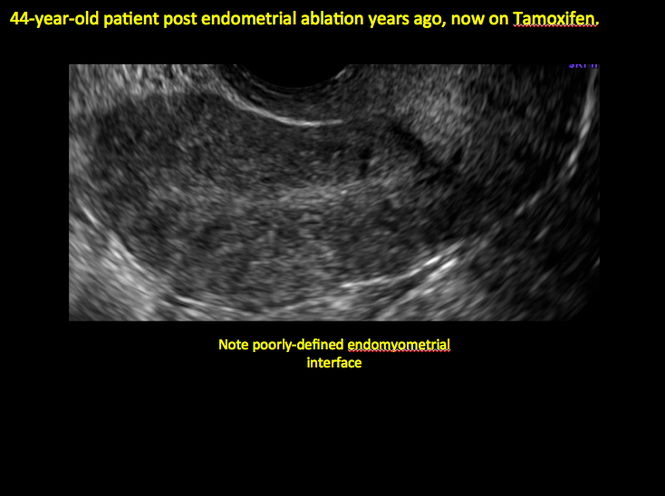

Tamoxifen is known to cause a slight but statistically significant increase in endometrial cancer. In 1994, I first described an unusual ultrasound appearance in the uterus of patients receiving tamoxifen, which was being misinterpreted as "endometrial thickening," and resulted in many unnecessary biopsies and dilation and curettage procedures.1 This type of uterine change has been seen in other selective estrogen-receptor modulators as well.2,3 In this article, Drs. Ozcan and Kaunitz correctly point out that such an ultrasound pattern does not necessitate any intervention in the absence of bleeding.

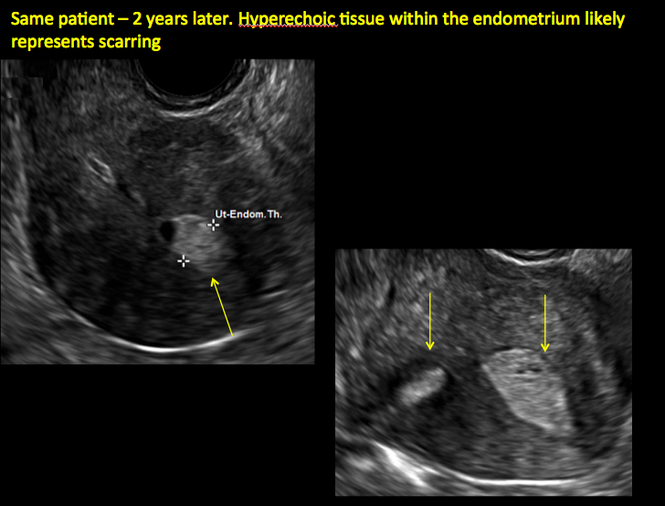

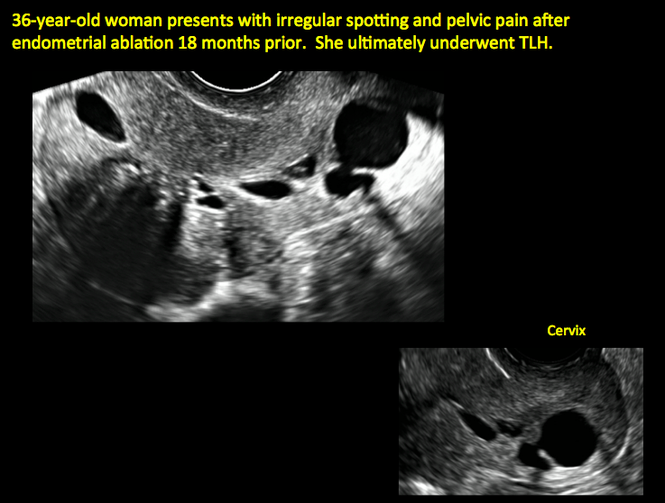

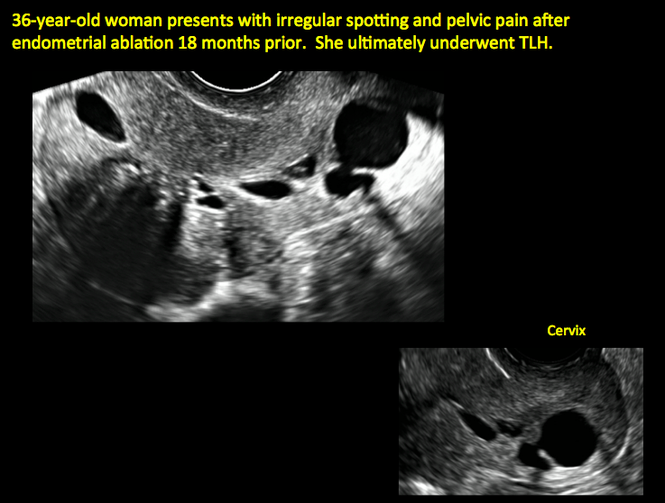

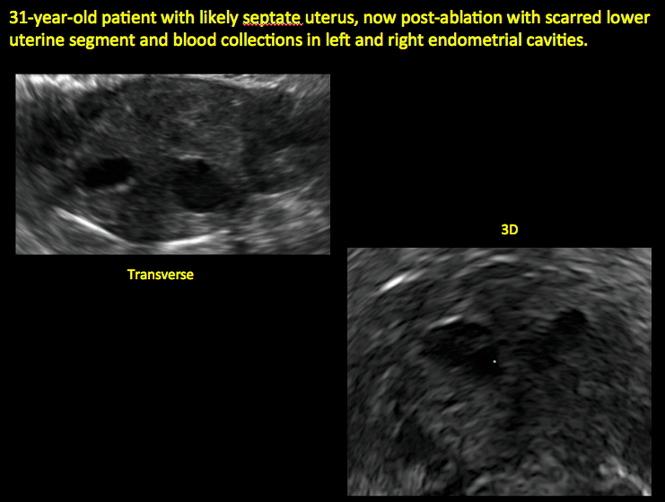

Another common question I am often asked is, "How do we handle the patient whose status is post-endometrial ablation and presents with staining?" The scarring shown in the figures that follow make any kind of meaningful evaluation extremely difficult.

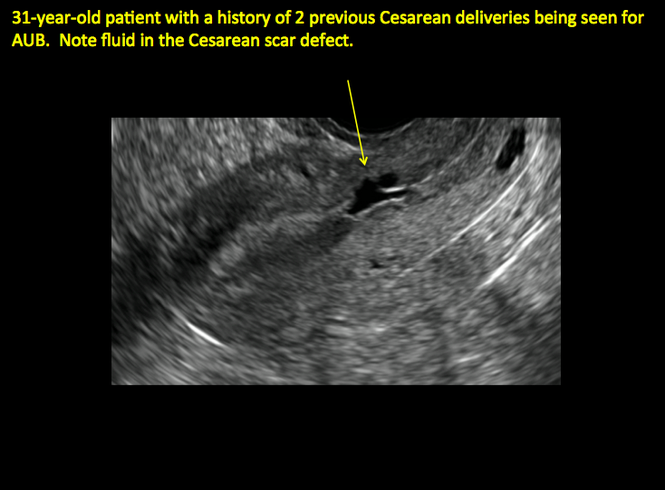

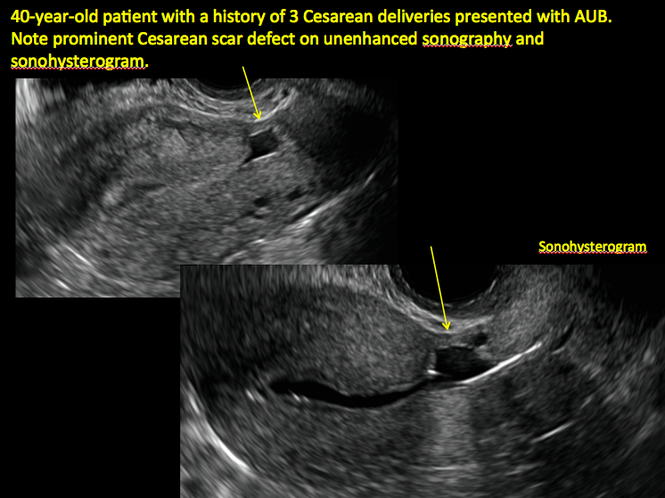

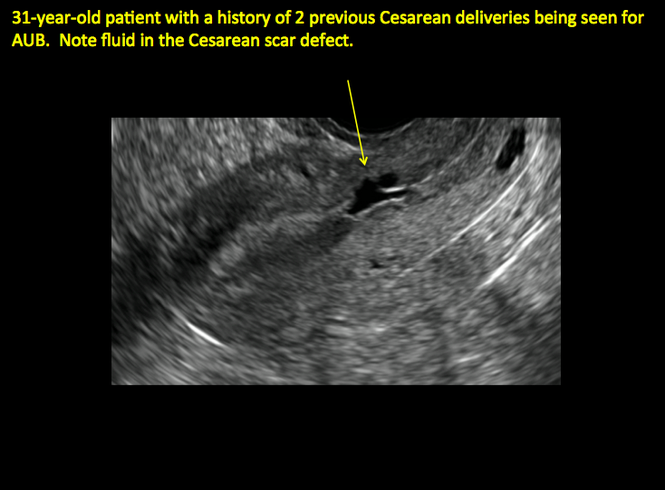

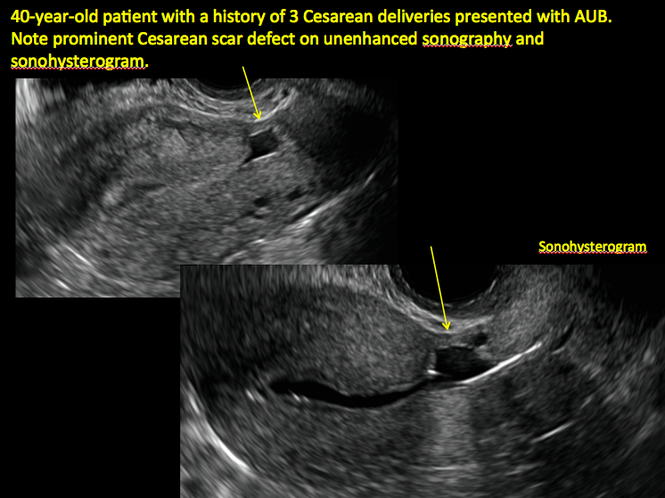

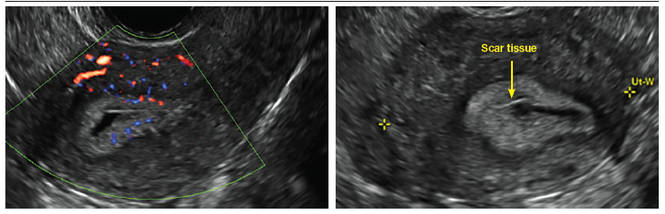

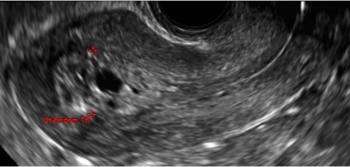

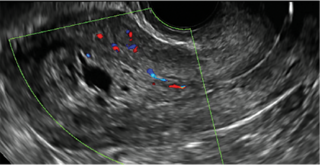

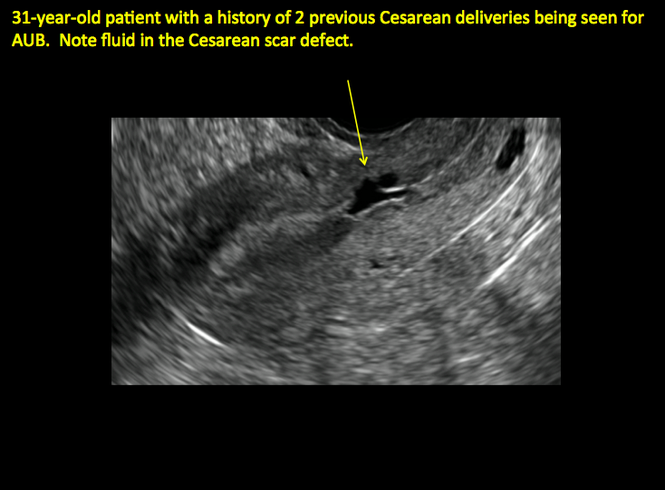

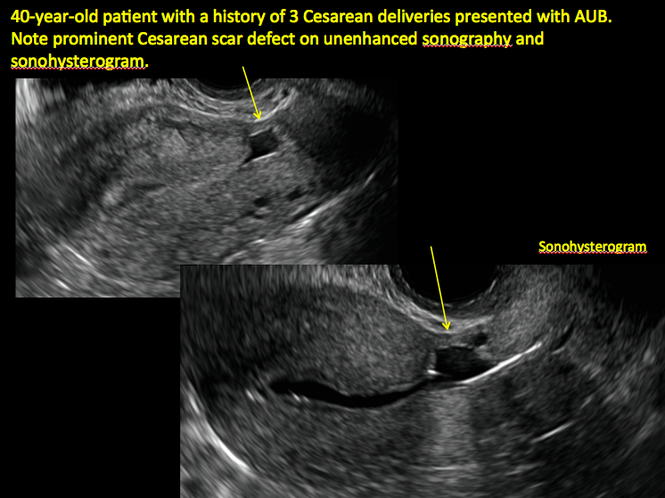

There has been an epidemic of cesarean scar pregnancies when a subsequent gestation implants in the cesarean scar defect.4 Perhaps the time has come when all patients with a previous cesarean delivery should have their lower uterine segment scanned to look for such a defect as shown in the pictures that follow. If we are not yet ready for that, at least early TVUS scans in subsequent pregnancies, in my opinion, should be employed to make an early diagnosis of such cases that are the precursors of morbidly adherent placenta, a potentially life-threatening situation that appears to be increasing in frequency.

Finally, look to obgmanagement.com for next month's web-exclusive look at outstanding images of patients who have undergone transcervical sterilization.

Dr. Goldstein is Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine, Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound, and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Dr. Goldstein reports that he has an equipment loan from Philips, and is past President of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine.

References

- Goldstein SR. Unusual ultrasonographic appearance of the uterus in patients receiving tamoxifen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(2):447–451.

- Goldstein SR, Neven P, Cummings S, et al. Postmenopausal evaluation and risk reduction with lasofoxifene (PEARL) trial: 5-year gynecological outcomes. Menopause. 2011;18(1):17–22.

- Goldstein SR, Nanavati N. Adverse events that are associated with the selective estrogen receptor modulator levormeloxifene in an aborted phase III osteoporosis treatment study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):521–527.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14–29.

New technology, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and medications continue to change how physicians manage specific medical issues. Many procedures and medications used by gynecologists can cause characteristic findings on sonography. These findings can guide subsequent counseling and management decisions and are important to accurately interpret on imaging. Among these conditions are Asherman syndrome, postendometrial ablation uterine damage, cesarean scar defect, and altered endometrium as a result of tamoxifen use. In this article, we provide 2 dimensional and 3 dimensional sono‑graphic images of uterine presentations of these 4 conditions.

Asherman syndromeCharacterized by variable scarring, or intrauterine adhesions, inside the uterine cavity following endometrial trauma due to surgical procedures, Asherman syndrome can cause menstrual changes and infertility. Should pregnancy occur in the setting of Asherman syndrome, placental abnormalities may result.1 Intrauterine adhesions can follow many surgical procedures, including curettage (diagnostic or for missed/elective abortion or retained products of conception), cesarean delivery, and hysteroscopic myomectomy. They may even occur after spontaneous abortion without curettage. Rates of Asherman syndrome are highest after procedures that tend to cause the most intrauterine inflammation, including2:

- curettage after septic abortion

- late curettage after retained products of conception

- hysteroscopy with multiple myomectomies.

In severe cases Asherman syndrome can result in complete obliteration of the uterine cavity.3

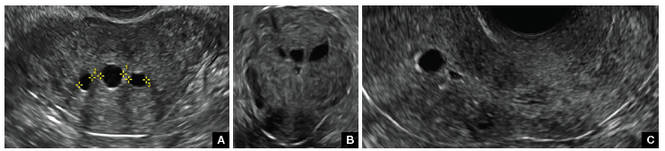

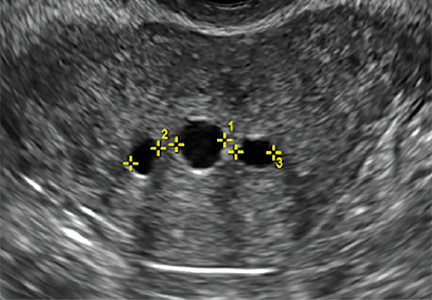

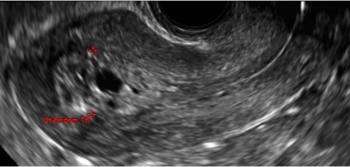

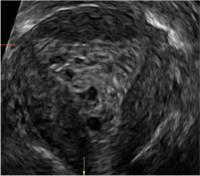

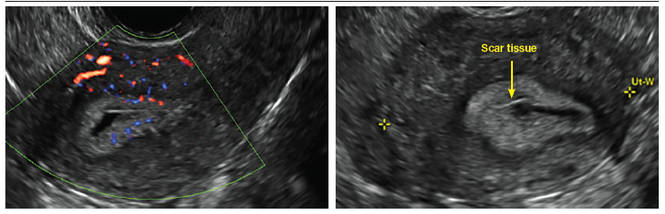

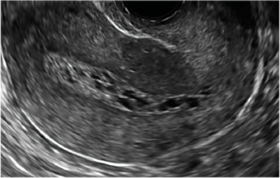

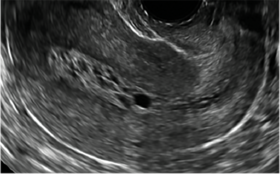

Clinicians should be cognizant of the appearance of Asherman syndrome on imaging because patients reporting menstrual abnormalities, pelvic pain (FIGURE 1), infertility, and other symptoms may exhibit intrauterine lesions on sonohysterography, or sometimes unenhanced sonography if endometrial fluid/blood is present. Depending on symptoms and patient reproductive plans, treatment may be indicated.2

| FIGURE 1 Asherman syndrome | ||||

|

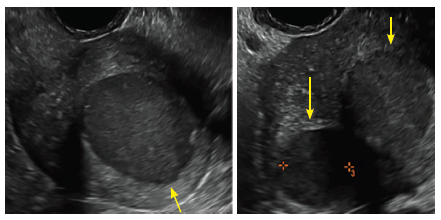

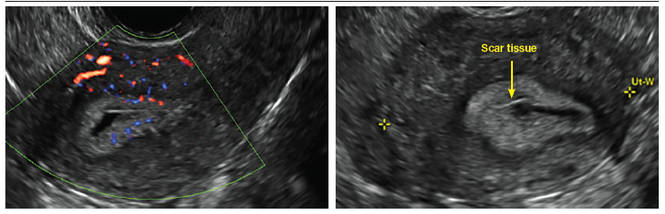

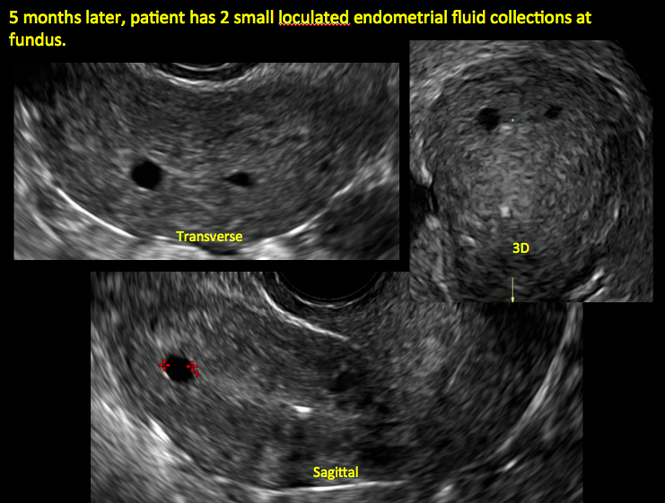

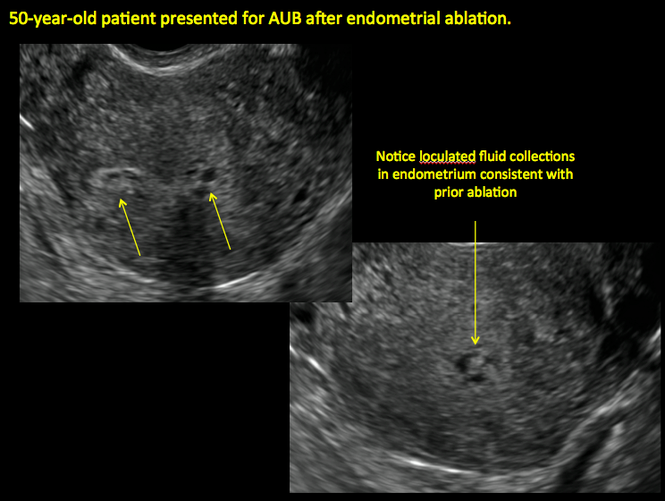

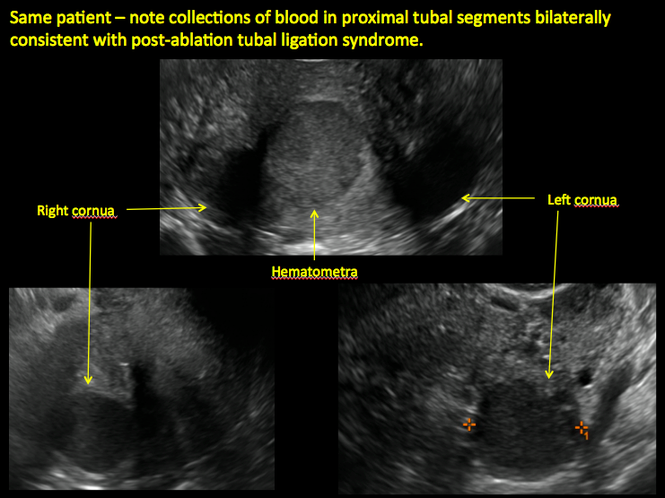

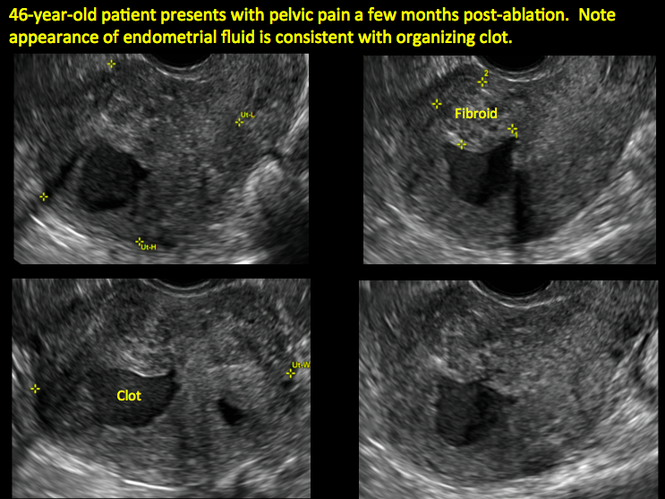

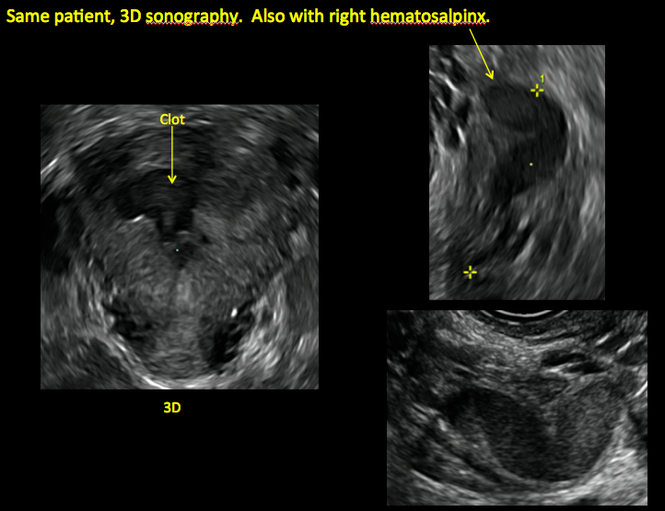

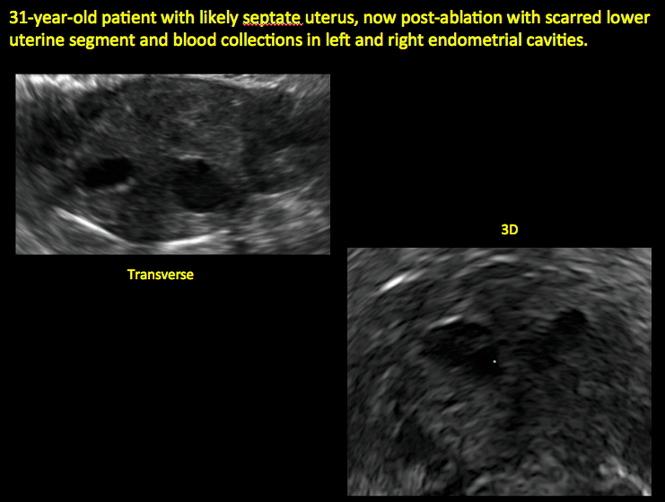

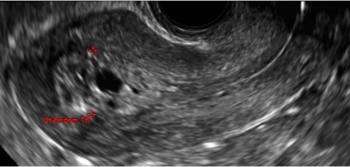

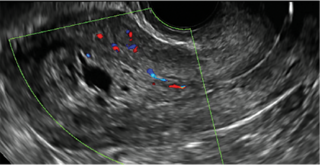

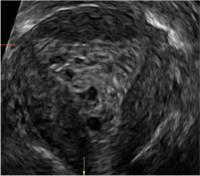

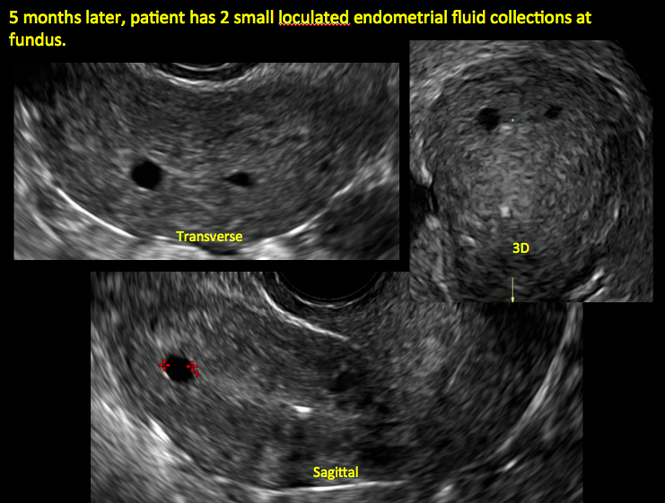

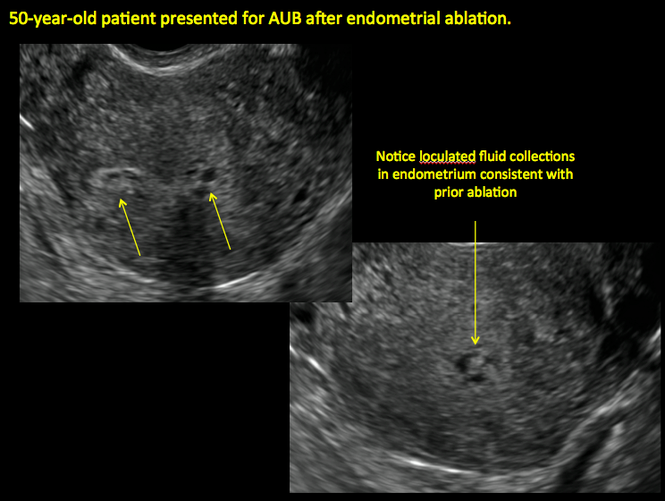

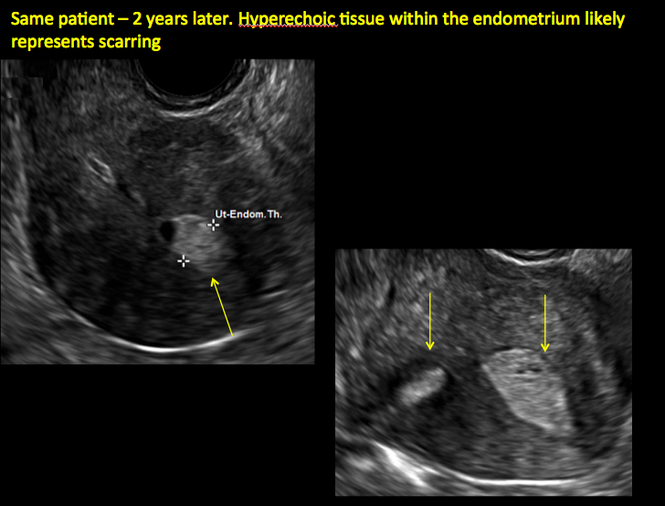

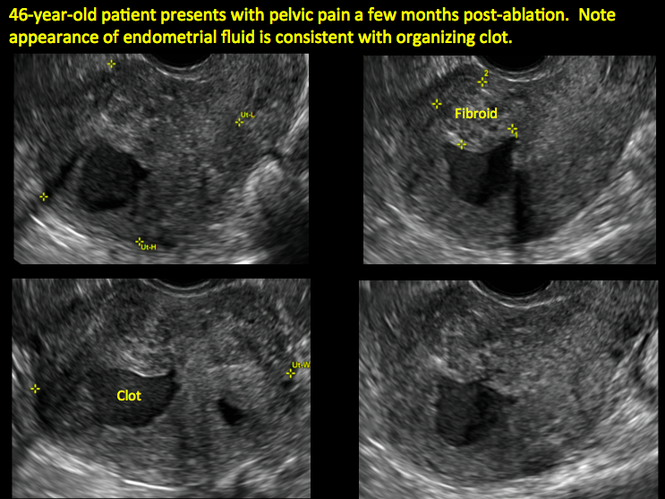

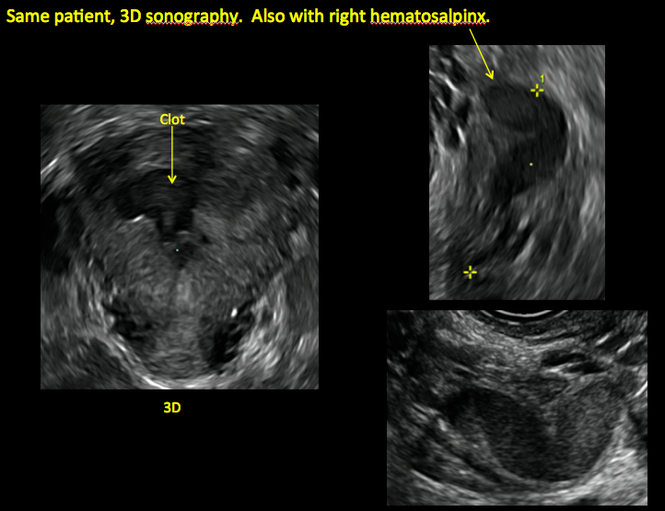

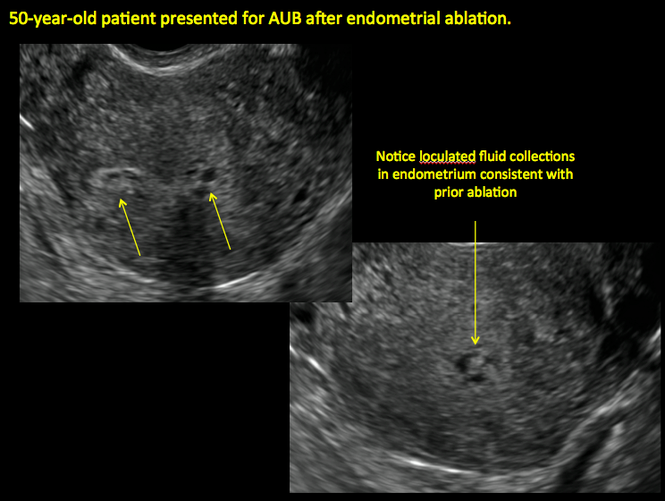

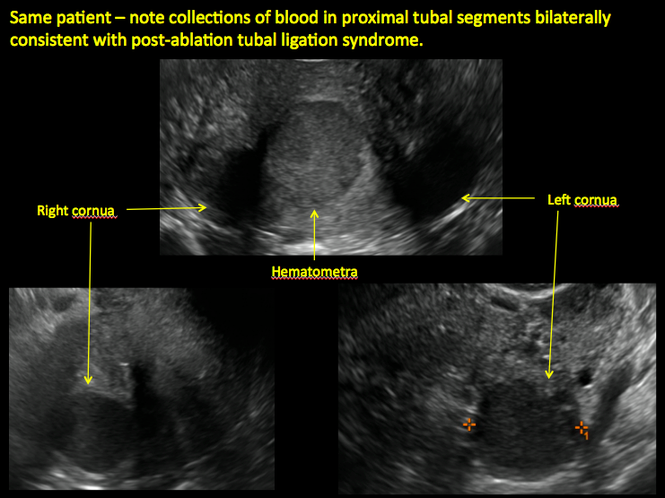

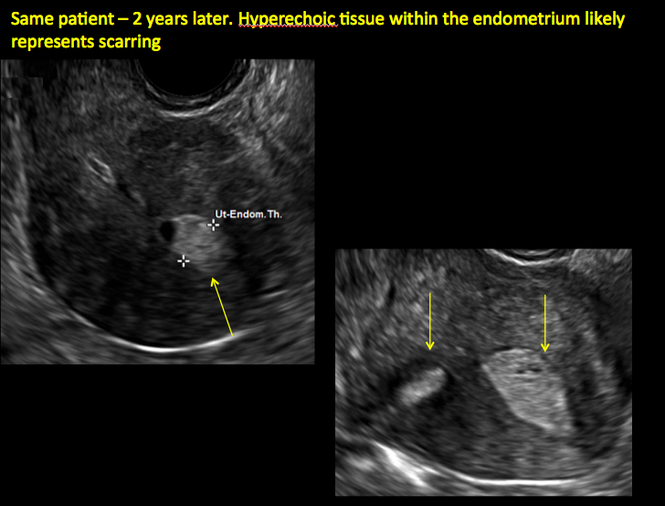

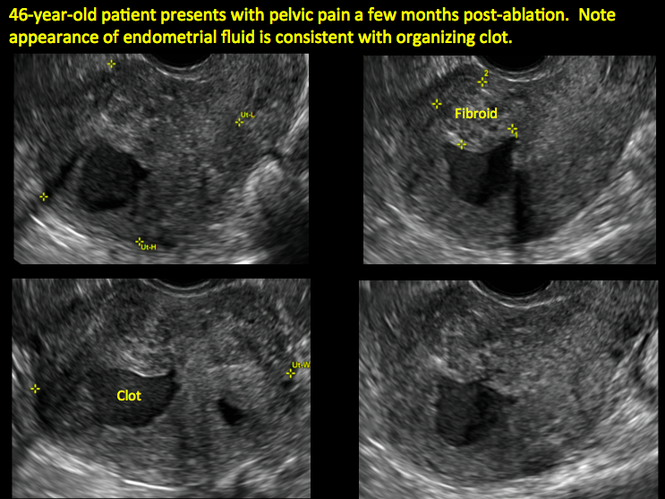

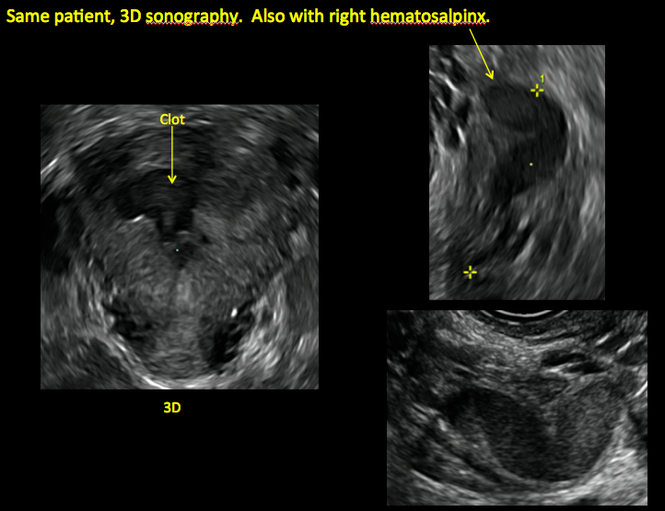

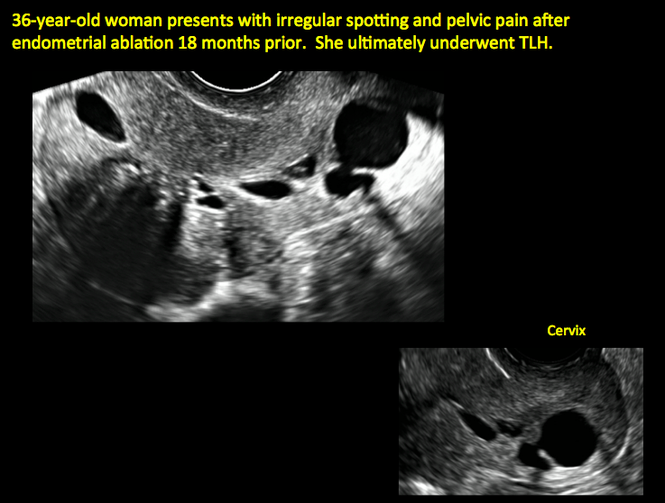

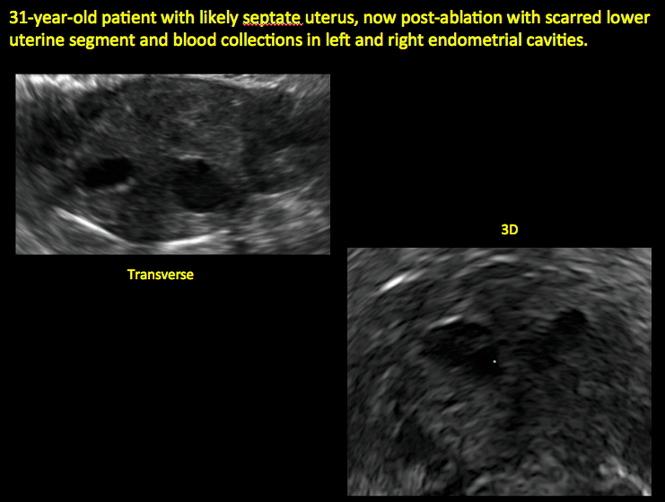

Postablation endometrial destruction

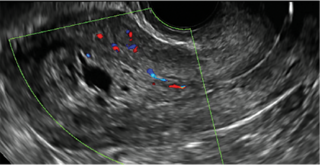

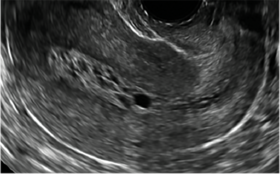

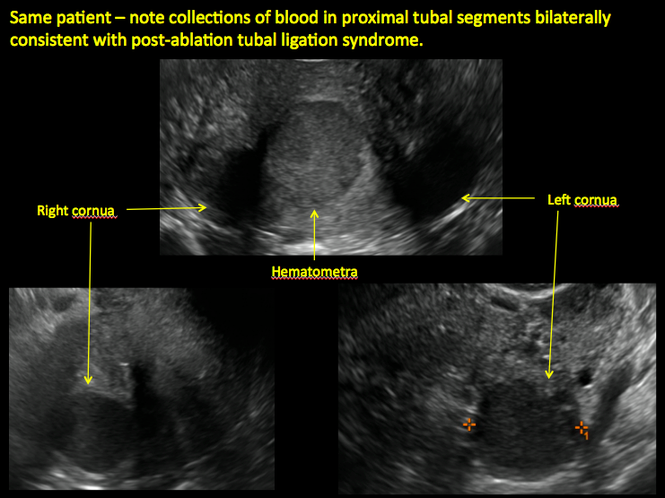

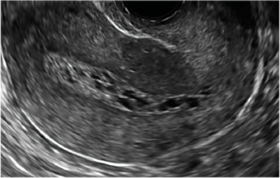

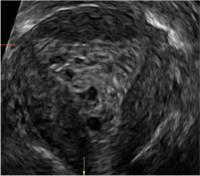

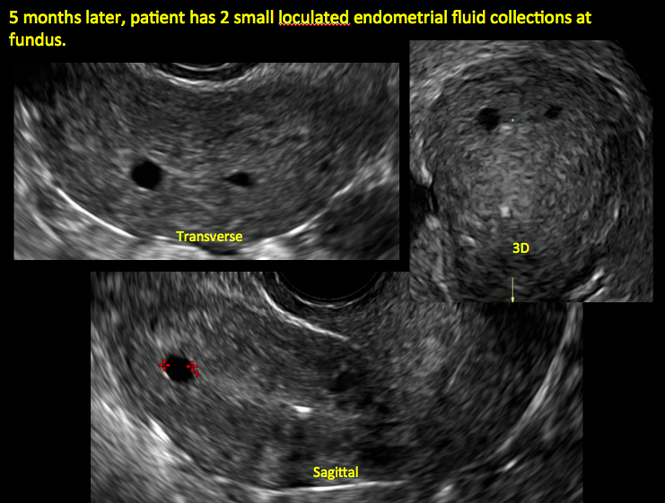

Surgical destruction of the endometrium to the level of the basalis has been associated with the formation of intrauterine adhesions (FIGURE 2) as well as pockets of hematometra (FIGURE 3). In a large Cochrane systematic review, the reported rate of hematometra was 0.9% following non− resectoscopic ablation and 2.4% following resectoscopic ablation.4

FIGURE 2 Intrauterine changes postablation | ||||

| ||||

| Loculated fluid collections in the endometrium on transverse (A), sagittal (B), and 3 dimensional images (C) of a 41-year-old patient who presented with dysmenorrhea 3 years after an endometrial ablation procedure. The patient ultimately underwent transvaginal hysterectomy. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| 2 dimensional sonograms of a 40-year-old patient with a history of bilateral tubal ligation who presented for severe cyclic pelvic pain postablation. |

Postablation tubal sterilization syndrome—cyclic cramping with or without vaginal bleeding—occurs in up to 10% of previously sterilized women who undergo endometrial ablation.4 The syndrome is thought to be caused by bleeding from active endometrium trapped at the uterine cornua by intrauterine adhesions postablation.

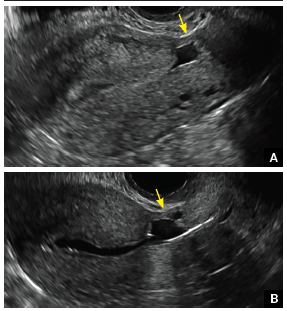

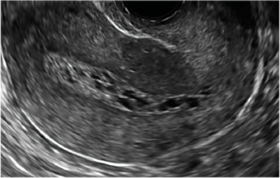

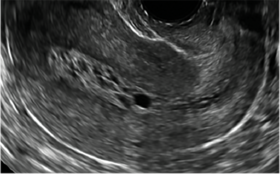

FIGURE 4 Cesarean scar defect with 1 previous cesarean delivery | ||||

| ||||

| Unenhanced sonogram in a 41-year-old patient. Myometrial notch is seen at both the endometrial surface and the serosal surface. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Unenhanced sonogram (A) and sonohysterogram (B) in a 40-year-old patient. |