User login

SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized children and youth

Clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity

Clinical questions: What are the demographics and clinical features of pediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) syndromes, and which admitting demographics and clinical features are predictive of disease severity?

Background: In children, SARS-CoV-2 causes respiratory disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as well as other clinical manifestations. The authors of this study chose to address the gap of identifying characteristics for severe disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, including respiratory disease, MIS-C and other manifestations.

Study design: Retrospective and prospective cohort analysis of hospitalized children

Setting: Participating hospitals in Tri-State Pediatric COVID-19 Consortium, including hospitals in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Synopsis: The authors identified hospitalized patients 22 years old or younger who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test or met the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions’ MIS-C case definition. For comparative analysis, patients were divided into a respiratory disease group (based on the World Health Organization’s criteria for COVID-19), MIS-C group or other group (based on the primary reason for hospitalization).

The authors included 281 patients in the study. 51% of the patients presented with respiratory disease, 25% with MIS-C and 25% with other symptoms, including gastrointestinal, or fever. 51% of all patients were Hispanic and 23% were non-Black Hispanic. The most common pre-existing comorbidities amongst all groups were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Patients with respiratory disease had a median age of 14 years while those with MIS-C had a median age of 7 years. Patients more commonly identified as non-Hispanic Black in the MIS-C group vs the respiratory group (35% vs. 18%). Obesity and medical complexity were more prevalent in the respiratory group relative to the MIS-C group. 75% of patients with MIS-C had gastrointestinal symptoms. 44% of respiratory patients had a chest radiograph with bilateral infiltrates on admission, and 18% or respiratory patients required invasive mechanical ventilation. The most common complications in the respiratory group were acute respiratory distress syndrome (17%) and acute kidney injury (11%), whereas shock (35%) and cardiac dysfunction (25%) were the most common complications in the MIS-C group. The median length of stay for all patients was 4 days (IQR 2-8 days).

Patients with MIS-C were more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) but all deaths (7 patients) occurred in the respiratory group. 40% of patients with respiratory disease, 56% of patients with MIS-C, and 6% of other patients met the authors’ definition of severe disease (ICU admission > 48 hours). For the respiratory group, younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph were independent predictors of severe disease based on multivariate analyses. For the MIS-C group, lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP at admission were independent predictors of severity.

Bottom line: Mortality in pediatric patients is low. Ethnicity and race were not predictive of disease severity in this model, even though 51% of the patients studied were Hispanic and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. Severity of illness for patients with respiratory disease was found to be associated with younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph. Severity of illness in patients with MIS-C was associated with lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP.

Citation: Fernandes DM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity in hospitalized children and youth. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 14;S0022-3476(20):31393-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

Dr. Kumar is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity

Clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity

Clinical questions: What are the demographics and clinical features of pediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) syndromes, and which admitting demographics and clinical features are predictive of disease severity?

Background: In children, SARS-CoV-2 causes respiratory disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as well as other clinical manifestations. The authors of this study chose to address the gap of identifying characteristics for severe disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, including respiratory disease, MIS-C and other manifestations.

Study design: Retrospective and prospective cohort analysis of hospitalized children

Setting: Participating hospitals in Tri-State Pediatric COVID-19 Consortium, including hospitals in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Synopsis: The authors identified hospitalized patients 22 years old or younger who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test or met the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions’ MIS-C case definition. For comparative analysis, patients were divided into a respiratory disease group (based on the World Health Organization’s criteria for COVID-19), MIS-C group or other group (based on the primary reason for hospitalization).

The authors included 281 patients in the study. 51% of the patients presented with respiratory disease, 25% with MIS-C and 25% with other symptoms, including gastrointestinal, or fever. 51% of all patients were Hispanic and 23% were non-Black Hispanic. The most common pre-existing comorbidities amongst all groups were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Patients with respiratory disease had a median age of 14 years while those with MIS-C had a median age of 7 years. Patients more commonly identified as non-Hispanic Black in the MIS-C group vs the respiratory group (35% vs. 18%). Obesity and medical complexity were more prevalent in the respiratory group relative to the MIS-C group. 75% of patients with MIS-C had gastrointestinal symptoms. 44% of respiratory patients had a chest radiograph with bilateral infiltrates on admission, and 18% or respiratory patients required invasive mechanical ventilation. The most common complications in the respiratory group were acute respiratory distress syndrome (17%) and acute kidney injury (11%), whereas shock (35%) and cardiac dysfunction (25%) were the most common complications in the MIS-C group. The median length of stay for all patients was 4 days (IQR 2-8 days).

Patients with MIS-C were more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) but all deaths (7 patients) occurred in the respiratory group. 40% of patients with respiratory disease, 56% of patients with MIS-C, and 6% of other patients met the authors’ definition of severe disease (ICU admission > 48 hours). For the respiratory group, younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph were independent predictors of severe disease based on multivariate analyses. For the MIS-C group, lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP at admission were independent predictors of severity.

Bottom line: Mortality in pediatric patients is low. Ethnicity and race were not predictive of disease severity in this model, even though 51% of the patients studied were Hispanic and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. Severity of illness for patients with respiratory disease was found to be associated with younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph. Severity of illness in patients with MIS-C was associated with lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP.

Citation: Fernandes DM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity in hospitalized children and youth. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 14;S0022-3476(20):31393-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

Dr. Kumar is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

Clinical questions: What are the demographics and clinical features of pediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) syndromes, and which admitting demographics and clinical features are predictive of disease severity?

Background: In children, SARS-CoV-2 causes respiratory disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as well as other clinical manifestations. The authors of this study chose to address the gap of identifying characteristics for severe disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, including respiratory disease, MIS-C and other manifestations.

Study design: Retrospective and prospective cohort analysis of hospitalized children

Setting: Participating hospitals in Tri-State Pediatric COVID-19 Consortium, including hospitals in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Synopsis: The authors identified hospitalized patients 22 years old or younger who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test or met the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions’ MIS-C case definition. For comparative analysis, patients were divided into a respiratory disease group (based on the World Health Organization’s criteria for COVID-19), MIS-C group or other group (based on the primary reason for hospitalization).

The authors included 281 patients in the study. 51% of the patients presented with respiratory disease, 25% with MIS-C and 25% with other symptoms, including gastrointestinal, or fever. 51% of all patients were Hispanic and 23% were non-Black Hispanic. The most common pre-existing comorbidities amongst all groups were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Patients with respiratory disease had a median age of 14 years while those with MIS-C had a median age of 7 years. Patients more commonly identified as non-Hispanic Black in the MIS-C group vs the respiratory group (35% vs. 18%). Obesity and medical complexity were more prevalent in the respiratory group relative to the MIS-C group. 75% of patients with MIS-C had gastrointestinal symptoms. 44% of respiratory patients had a chest radiograph with bilateral infiltrates on admission, and 18% or respiratory patients required invasive mechanical ventilation. The most common complications in the respiratory group were acute respiratory distress syndrome (17%) and acute kidney injury (11%), whereas shock (35%) and cardiac dysfunction (25%) were the most common complications in the MIS-C group. The median length of stay for all patients was 4 days (IQR 2-8 days).

Patients with MIS-C were more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) but all deaths (7 patients) occurred in the respiratory group. 40% of patients with respiratory disease, 56% of patients with MIS-C, and 6% of other patients met the authors’ definition of severe disease (ICU admission > 48 hours). For the respiratory group, younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph were independent predictors of severe disease based on multivariate analyses. For the MIS-C group, lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP at admission were independent predictors of severity.

Bottom line: Mortality in pediatric patients is low. Ethnicity and race were not predictive of disease severity in this model, even though 51% of the patients studied were Hispanic and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. Severity of illness for patients with respiratory disease was found to be associated with younger age, obesity, increasing white blood cell count, hypoxia, and bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph. Severity of illness in patients with MIS-C was associated with lower absolute lymphocyte count and increasing CRP.

Citation: Fernandes DM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 clinical syndromes and predictors of disease severity in hospitalized children and youth. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 14;S0022-3476(20):31393-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

Dr. Kumar is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

#ConsentObtained – Patient Privacy in the Age of Social Media

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

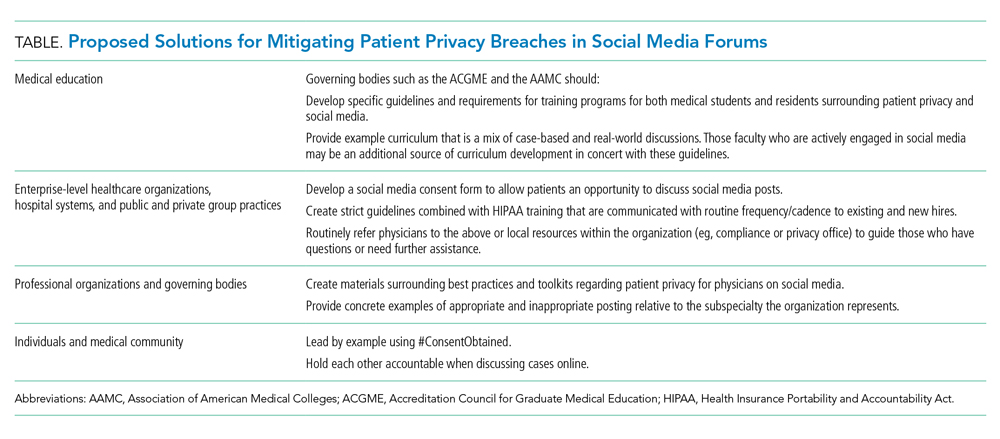

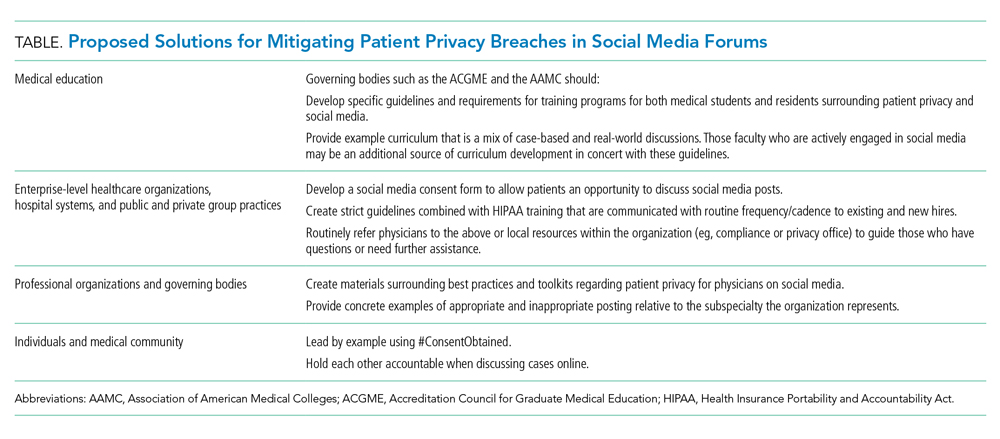

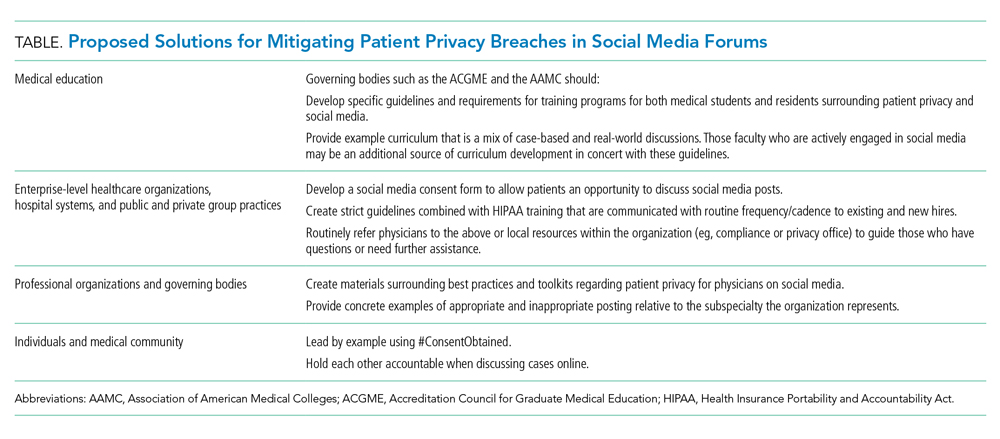

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

“I have a rare dermatologic disorder. In medical school, I read a case report about treatment for my disorder. I was surprised to read my history and shocked to see my childhood face staring back at me in the figures section. The case report was written when I was a child and my parents had signed a consent form that stated my case and images could be used for ‘educational purposes.’ My parents were not notified that my images and case were published. While surprised and shocked to read my history and see images of myself in a medical journal, I trusted my privacy was protected because the journal would only be read by medical professionals. Fast-forward to today, I do not know how comfortable I would feel if my images were shared on social media, with the potential to reach viewers outside of the medical community. If I were a parent, I would feel even more uncomfortable with reading my child’s case on social media, let alone viewing an image of my child.”

—A.K.

Social media has become ingrained in our society, including many facets of our professional life. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans use social media.1 The PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Institute found 90% of physicians use social media personally, and 65% use it professionally.2

As the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference Social Media Cochairs (2015-2019), we managed official profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. We also crafted and executed the conference’s social media strategy. During that time, we witnessed a substantial increase in the presence of physicians on social media with little available guidance on best practices. Here, we discuss patient privacy challenges with social media as well as solutions to address them.

PATIENT PRIVACY CHALLENGES ON SOCIAL MEDIA

In 2011, Greyson et al surveyed executive directors of all medical and osteopathic boards in the United States for online professionalism violations.3 Online violations of patient confidentiality were reported by over 55% of the 48 boards that responded. Of those, 10% reported more than three violations of patient confidentiality, and no actions were initially taken in 25% of violations. While these violations were not specific to social media, they highlight online patient confidentiality breaches are occurring, even if they are not being disciplined.

Several organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have developed social media guidelines.4-6 However, these guidelines are not always followed. Fanti Silva and Colleoni studied surgeons and surgical trainees at a university hospital and found that social media guidelines were unknown to 100% of medical students, 85% of residents, and 78% of attendings.7 They also found that 53% of medical students, 86% of residents, and 32% of attendings were sharing patient information on social media despite hospitals’ privacy policies.

Social media provides forums for physicians to discuss cases and share experiences in hopes of educating others. These posts may include images or videos. Unfortunately, sharing specific clinical information or improperly deidentifying images may lead to the unintentional identification of patients.8 Some information may not be protected by the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, and may lead to patient identification when shared.9 Despite disguising or omitting demographics, encounter information, or unique characteristics of the presentation, some physicians—not the posting physician—believe patients may still be able to identify their cases.8

Physicians who try to be mindful of patient privacy concerns face challenges with social media platforms themselves. For example, Facebook allows users to create Closed Groups (CGs) in which the group’s “administrators” can grant “admission” to users wishing to join the conversation (eg, Physician Moms Group). These groups are left to govern themselves and comply only with Facebook’s safety standards. The Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons used Facebook’s CGs to create a forum for education, consultation, and collaboration for society members. Group administrators grant admittance only after group members have agreed to HIPAA compliance. Group members may then share deidentified images and videos when discussing cases.10 However, Facebook’s Terms of Service states the company has “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, translate, and create derivative works” of the content based on the privacy settings of the individual posting the content.11 Therefore, these CGs may create a false sense of security because many members may assume the content of the CGs are private. Twitter’s Terms of Service are similar to Facebook’s, but state that users should have “obtained, all rights, licenses, consents, permissions, power and/or authority necessary to grant the rights . . . for any Content that is posted.”12 If a patient’s deidentified story is posted on Twitter, the posting physician may be violating Twitter’s Terms of Service by not obtaining the patient’s consent/permission or explicitly stating so in their tweet.

SOLUTIONS

In light of the challenges faced when posting medical cases on social media, we propose several solutions that the medical community should adopt to mitigate and limit any potential breaches to patient privacy. These are summarized in the Table.

Medical Education

Many medical students and residents are active on social media. However, not all are formally educated on appropriate engagement online and social media etiquette. A recent article from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) highlights how this “curriculum” is missing from many medical schools and residency programs.13 There are plenty of resources outlining how to maintain professionalism on social media in a general sense, but maintaining patient privacy usually is not concretely explored. Consequently, many programs are left to individually provide this education without firm guidance on best practices. We propose that governing organizations for medical education such as the AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have formal requirements, guidelines, and example curriculum on educating trainees on best practices for social media activity.

Health Organization Consent Forms

Healthcare organizations have a responsibility to protect patient privacy. We propose that healthcare organizations should develop independent social media consent forms that address sharing of images, videos, and cases. This separate social media consent form would allow patients/guardians to discuss whether they want their information shared. Some organizations have taken this step and developed consent forms for sharing deidentified posts on HIPAA-compliant CGs.10 However, it is still far from standard of practice for a healthcare organization to develop a separate consent form addressing the educational uses of sharing cases on social media. The Federation of State Medical Board’s (FSMB) Social Media and Electronic Communications policy endorses obtaining “express written consent” from patients.14 The policy states that “the physician must adequately explain the risks . . . for consent to be fully informed.” The FSMB policy also reminds readers that any social media post is permanent, even after it has been deleted.

Professional Organizations

Many professional organizations have acknowledged the growing role of social media in the professional lives of medical providers and have adopted policy statements and guidelines to address social media use. However, these guidelines are quite variable. All professional organizations should take the time to clarify and discuss the nuances of patient privacy on social media in their guidelines. For example, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology statement warns members that “any public communication about work-related clinical events may violate . . . privacy” and posting of deidentified general events “may be traced, through public vital statistics data, to a specific patient or hospital” directly violating HIPAA.15 In comparison, the AAP and ACP’s social media guidelines and toolkits fall short when discussing how to maintain patient privacy specifically. Within these toolkits and guidelines, there is no explicit guidance or discussion about maintaining patient privacy with the use of case examples or best practices.5,6 As physicians on social media, we should be aware of these variable policy statements and guidelines from our professional organizations. Even further, as active members of our professional organizations, we should call on them to update their guidelines to increase details regarding the nuances of patient privacy.

#ConsentObtained

When a case is posted on social media, it should be the posting physician’s responsibility to clearly state in the initial post that consent was obtained. To simplify the process, we propose the use of the hashtag, #ConsentObtained, to easily identify that assurances were made to protect the patient. Moreover, we encourage our physician colleagues to remind others to explicitly state if consent was obtained if it is not mentioned. The AMA’s code of ethics states that if physicians read posts that they feel are unprofessional, then those physicians “have a responsibility to bring that content to the attention of the individual, so that he or she can remove it and/or take other appropriate actions.”4 Therefore, we encourage all readers of social media posts to ensure that posts include #ConsentObtained or otherwise clearly state that patient permission was obtained. If the hashtag or verbiage is not seen, then it is the reader’s responsibility to contact the posting physician. The AMA’s code of ethics also recommends physicians to “report the matter to appropriate authorities” if the individual posting “does not take appropriate actions.”4 While we realize that verification of consent being obtained may be virtually impossible online, we hope that, as physicians, we hold patient privacy to the highest regard and would never use this hashtag inappropriately. Lastly, it’s important to remember that removing/deleting a post may delete it from the platform, but that post and its contents are not deleted from the internet and may be accessed through another site.

CONCLUSION

Social media has allowed the healthcare community to develop a voice for individuals and communities; it has allowed for collaboration, open discussion, and education. However, it also asks us to reevaluate the professional ethics and rules we have abided for decades with regard to keeping patient health information safe. We must be proactive to develop solutions regarding patient privacy as our social media presence continues to grow.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

1. Perrin A, Anderson M. Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Research Center. April 10, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018

2. Modahl M, Tompsett L, Moorhead T. Doctors, Patients, and Social Media.QuantiaMD. September 2011. Accessed September 9, 2019. http://www.quantiamd.com/q-qcp/social_media.pdf

3. Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1141-1142. https://.org/10.1001/jama.2012.330

4. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.3.2. American Medical Associaiton. November 14, 2016. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media

5. Social Media Toolkit. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Media-and-Children.aspx

6. Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Annal Intern Med. 2013;158:620-627. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100

7. Fanti Silva DA, Colleoni R. Patient’s privacy violation on social media in the surgical area. Am Surg. 2018;84(12):1900-1905.

8. Cifu AS, Vandross AL, Prasad V. Case reports in the age of Twitter. Am J Med. 2019;132(10):e725-e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.044

9. OCR Privacy Brief: Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Department of Health & Human Services; 2003. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf

10. Bittner JG 4th, Logghe HJ, Kane ED, et al. A Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on closed social media (Facebook) groups for clinical education and consultation: issues of informed consent, patient privacy, and surgeon protection. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6569-2

11. Terms of Service. Facebook. 2019. Accessed August 18, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

12. Terms of Service. Twitter. 2020. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://twitter.com/en/tos

13. Kalter L. The social media dilemma. Special to AAMC News. Mar 4, 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/social-media-dilemma

14. Social Media and Electronic Communications; Report and Recommendations of the FSMB Ethics and Professionalism Committee; Adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards April 2019. Federation of State Medical Boards. Accessed August 18, 2019. http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/social-media-and-electronic-communications.pdf

15. Professional use of digital and social media: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 791. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):e117-e121. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003451

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

PHM fellowship changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

Detection of COVID-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).