User login

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is among the most common elective orthopedic procedures performed annually in the United States, with an estimated 635,000 to 909,000 THAs expected each year by 2030.1 Consequently, complication rates and revision surgeries related to THA have been increasing, along with the financial burden on the health care system.2-4 Optimizing outcomes for patients undergoing THA and identifying risk factors for treatment failure have become areas of focus.

Over the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in the effect of previous lumbar spine fusion (LSF) surgery on THA outcomes. Studies have explored the rates of complications, postoperative mobility, and THA implant impingement.5-8 However, the outcome receiving the most attention in recent literature is the rate and effect of dislocation in patients with lumbar fusion surgery. Large Medicare database analyses have discovered an association with increased rates of dislocations in patients with lumbar fusion surgeries compared with those without.9,10 Prosthetic hip dislocation is an expensive complication of THA and is projected to have greater impact through 2035 due to a growing number of THA procedures.11 Identifying risk factors associated with hip dislocation is paramount to mitigating its effect on patients who have undergone THA.

Recent research has found increased rates of THA dislocation and revision surgery in patients with LSF, with some studies showing previous LSF as the strongest independent predictor.6-16 However, controversy surrounds this relationship, including the sequence of procedures (LSF before or after THA), the time between procedures, and involvement of the sacrum in LSF. One study found that patients had a 106% increased risk of dislocation when LSF was performed before THA compared with patients who underwent LSF 5 years after undergoing THA, while another study showed no significant difference in dislocations pre- vs post-LSF.16,17 An additional study showed no significant difference in the rate of dislocation in patients without sacral involvement in the LSF, while also showing significantly higher rates of dislocation in LSF with sacral involvement.12 The researchers also found a trend toward more dislocations in longer lumbosacral fusions. Recent studies have also examined dislocation rates with lumbar fusion in patients treated with dual-mobility liners.18-20 The consensus from these studies is that dual-mobility liners significantly decrease the rate of dislocation in primary THAs with lumbar fusion.

The present study sought to determine the rates of hip dislocations in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital setting. To the authors’ knowledge, no retrospective study focusing on THAs in the veteran population has been performed. This study benefits from controlling for various surgeon techniques and surgical preferences when compared to large Medicare database studies because the orthopedic surgeon (ABK) only performed the posterior approach for all patients during the study period.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether the rates of hip dislocation would, in fact, be higher in patients with lumbar fusion surgery, as recent database studies suggest. Secondary objectives included determining whether patient characteristics, comorbidities, number of levels fused, or inclusion of the sacrum in the fusion construct influenced dislocation rates. Furthermore, VA Dayton Healthcare System (VADHS) began routine use of dual-mobility liners for lumbar fusion patients in 2018, allowing for examination of these patients.

Methods

The Wright State University and VADHS Institutional Review Board approved this study design. A retrospective review of all primary THAs at VADHS was performed to investigate the relationship between previous lumbar spine fusion and the incidence of THA revision. Manual chart review was performed for patients who underwent primary THA between January 2003, and December 2022. One surgeon performed all surgeries using only the posterior approach. Patients were not excluded if they had bilateral procedures and all eligible hips were included. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of fracture of the femoral head or femoral neck at the time of surgery were excluded. Additionally, only patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up data were included.

The primary outcome was dislocation within 12 months of THA; the primary independent variable was LSF prior to THA. Covariates included patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, with additional data collected on the number of levels fused, sacral spine involvement, revision rates, and use of dual-mobility liners. Year of surgery was also included in analyses to account for any changes that may have occurred during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4. Patients were grouped into 2 cohorts, depending on whether they had received LSF prior to THA. Analyses were adjusted for repeated measures to account for the small percentage of patients with bilateral procedures.

Univariate comparisons between cohorts for covariates, as well as rates of dislocation and revision, were performed using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous categorical variables. Significant comorbidities, as well as age, sex, BMI, liner type, LSF cohort, and surgery year, were included in a logistic regression model to determine what effect, if any, they had on the likelihood of dislocation. Variables were removed using a backward stepwise approach, starting with the nonsignificant variable effect with the lowest χ2 value, and continuing until reaching a final model where all remaining variable effects were significant. For the variables retained in the final model, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were derived, with dislocation designated as the event. Individual comorbidity subcomponents of the CCI were also analyzed for their effects on dislocation using backward stepwise logistic regression. A secondary analysis among patients with LSF tested for the influence of the number of vertebral levels fused, the presence or absence of sacral involvement in the fusion, and the use of dual-mobility liners on the likelihood of hip dislocation.

Results

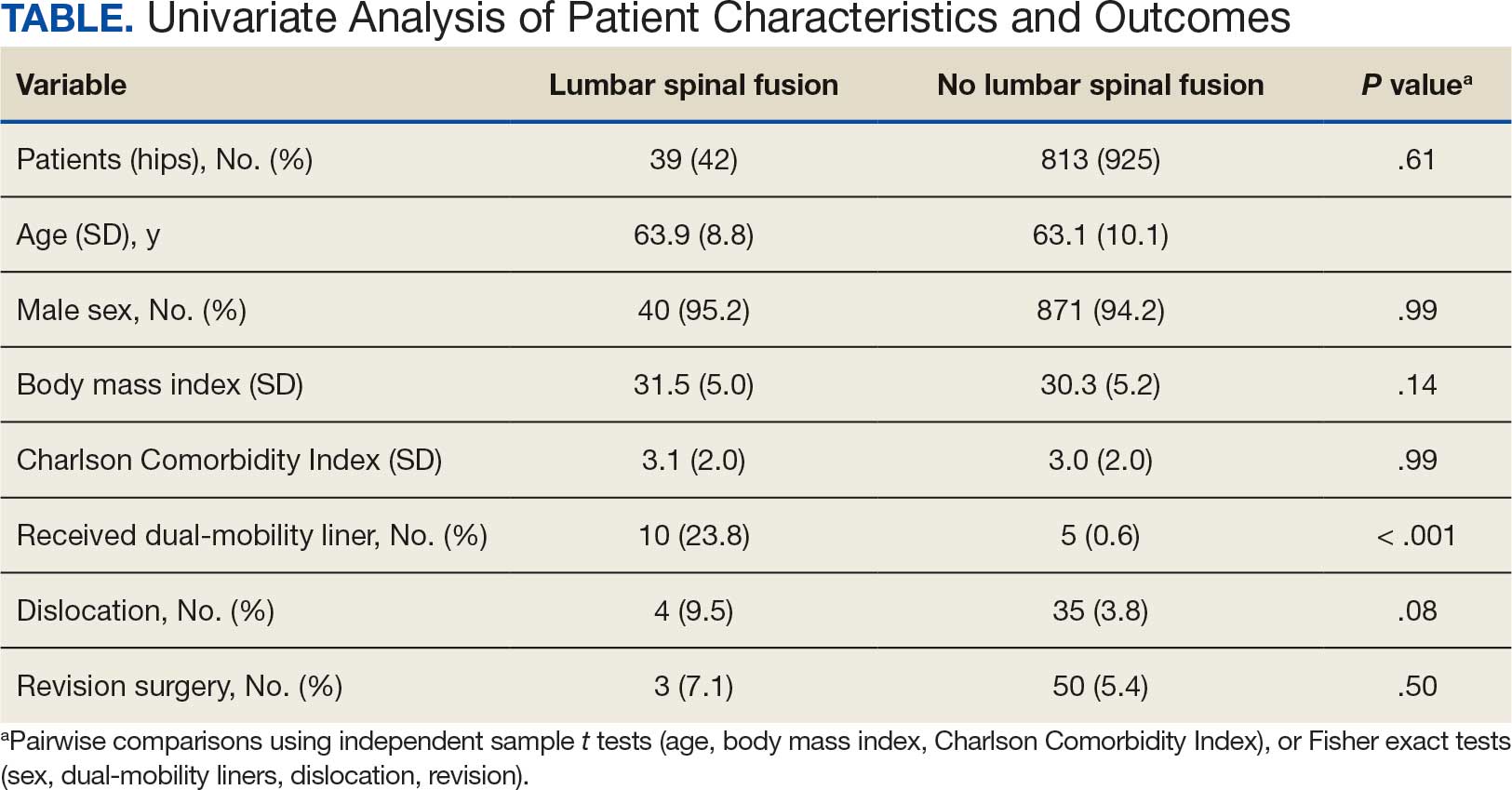

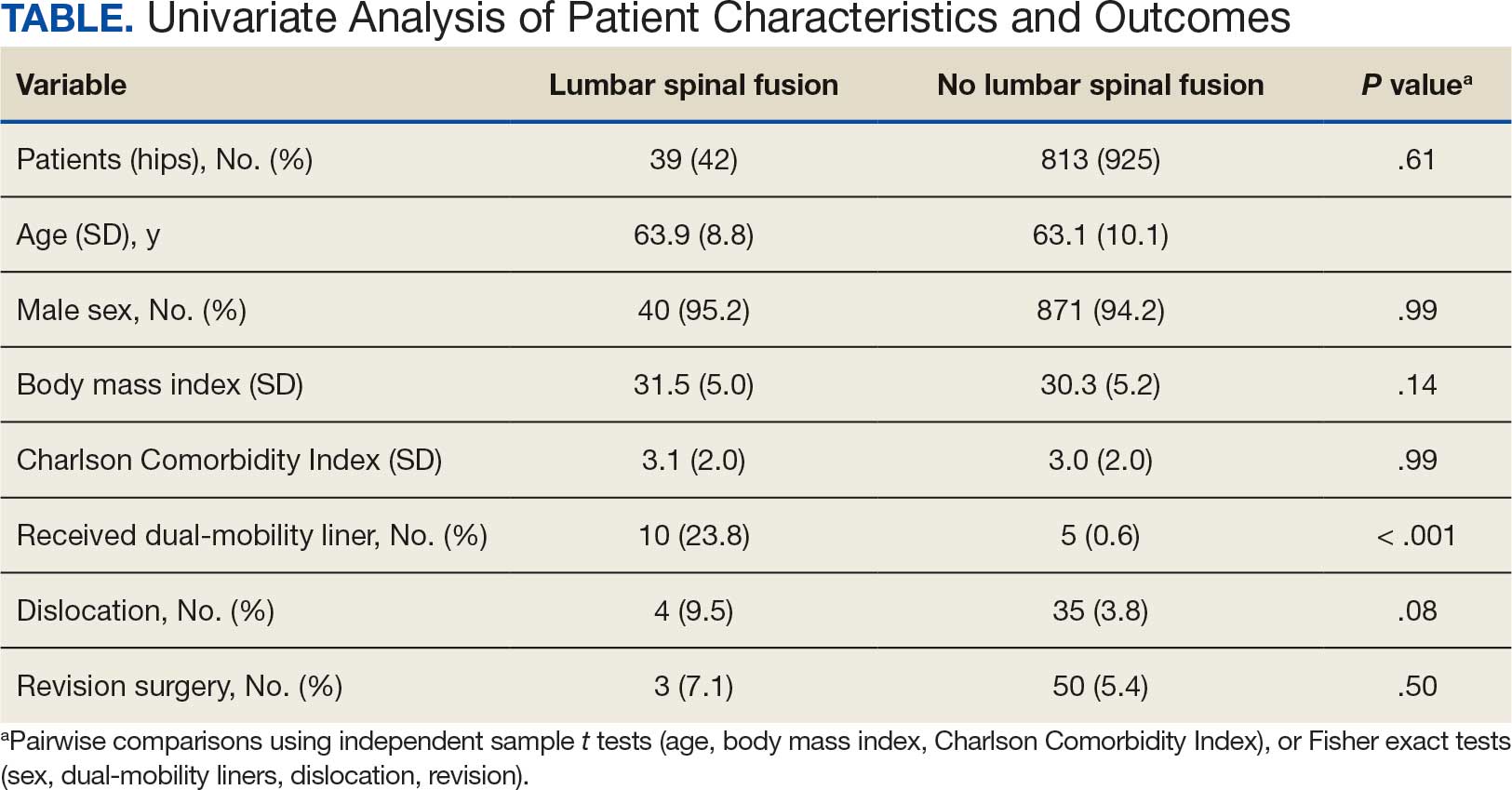

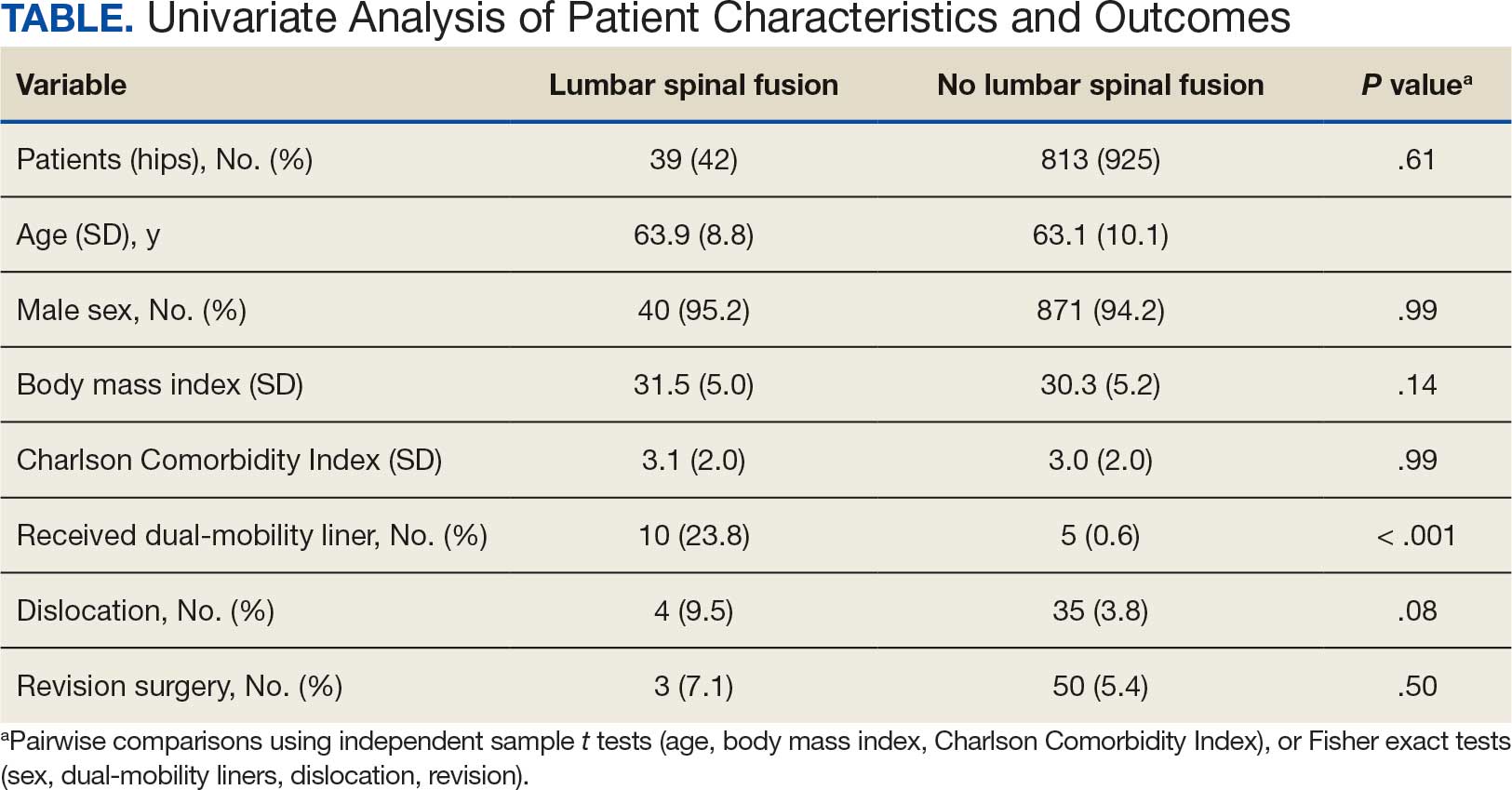

The LSF cohort included 39 patients with THA and prior LSF, 3 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 42 hips. The non-LSF cohort included 813 patients with THA, 112 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 925 hips. The LSF and non-LSF cohorts did not differ significantly in age, sex, BMI, CCI, or revision rates (Table). The LSF cohort included a significantly higher percentage of hips receiving dual-mobility liners than did the non-LSF cohort (23.8% vs 0.6%; P < .001) and had more than twice the rate of dislocation (4 of 42 hips [9.5%] vs 35 of 925 hips [3.8%]), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .08).

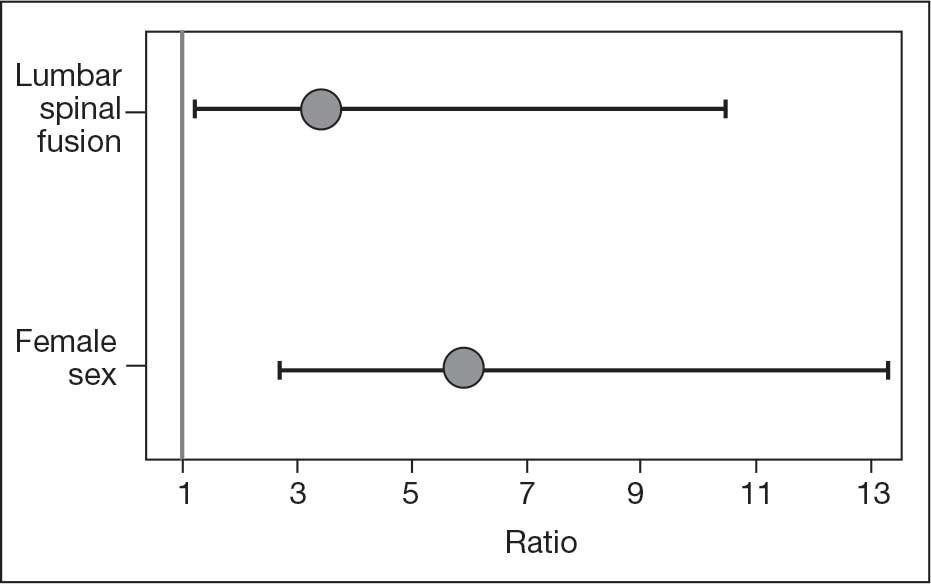

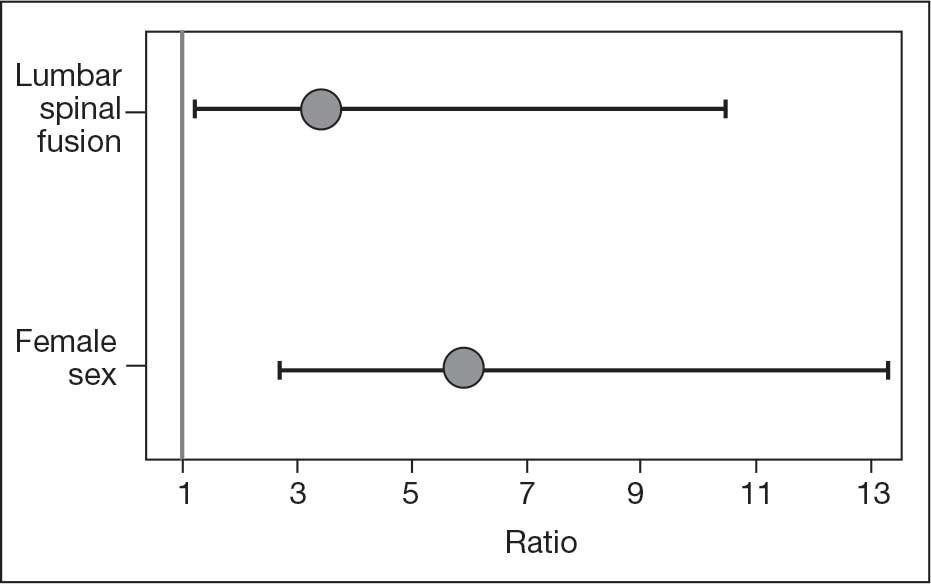

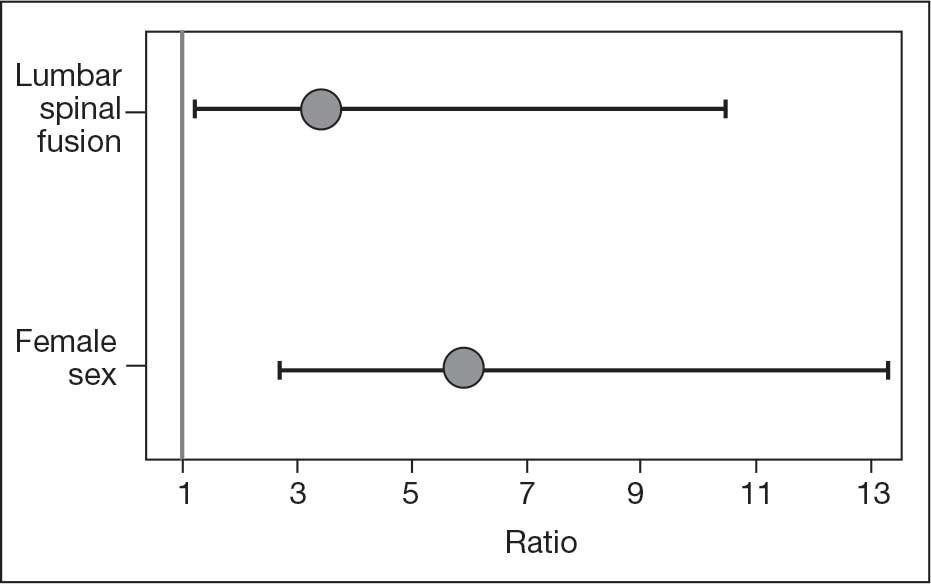

The final logistic regression model with dislocation as the outcome was statistically significant (χ2, 17.47; P < .001) and retained 2 significant predictor variables: LSF cohort (χ2, 4.63; P = .03), and sex (χ2, 18.27; P < .001). Females were more likely than males to experience dislocation (OR, 5.84; 95% CI, 2.60-13.13; P < .001) as were patients who had LSF prior to THA (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.12-10.47; P = .03) (Figure). None of the CCI subcomponent comorbidities significantly affected the probability of dislocation (myocardial infarction, P = .46; congestive heart failure, P = .47; peripheral vascular disease, P = .97; stroke, P = .51; dementia, P = .99; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, P = .95; connective tissue disease, P = .25; peptic ulcer, P = .41; liver disease, P = .30; diabetes, P = .06; hemiplegia, P = .99; chronic kidney disease, P = .82; solid tumor, P = .90; leukemia, P = .99; lymphoma, P = .99; AIDS, P = .99). Within the LSF cohort, neither the number of levels fused (P = .83) nor sacral involvement (P = .42), significantly affected the probability of hip dislocation. None of the patients in either cohort who received dual-mobility liners subsequently dislocated their hips, nor did any of them require revision surgery.

Discussion

Spinopelvic biomechanics have been an area of increasing interest and research. Spinal fusion has been shown to alter the mobility of the pelvis and has been associated with decreased stability of THA implants.21 For example, in the setting of a fused spine, the lack of compensatory changes in pelvic tilt or acetabular anteversion when adjusting to a seated or standing position may predispose patients to impingement because the acetabular component is not properly positioned. Dual-mobility constructs mitigate this risk by providing an additional articulation, which increases jump distance and range of motion prior to impingement, thereby enhancing stability.

The use of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF has also been examined.18-20 These studies demonstrate a reduced risk of postoperative THA dislocation in patients with previous LSF. The rate of postoperative complications and revisions for LSF patients with dual-mobility liners was also found to be similar to that of THAs without dual-mobility in patients without prior LSF. This study focused on a veteran population to demonstrate the efficacy of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF. The results indicate that LSF prior to THA and female sex were predictors for prosthetic hip dislocations in the 12-month postoperative period in this patient population, which aligns with the current literature.

The dislocation rate in the LSF-THA group (9.5%) was higher than the dislocation rate in the control group (3.8%). Although not statistically significant in the univariate analysis, LSF was shown to be a significant risk factor after controlling for patient sex. Other studies have found the dislocation rate to be 3% to 7%, which is lower than the dislocation rate observed in this study.8,10,16

The reasons for this higher rate of dislocation are not entirely clear. A veteran population has poorer overall health than the general population, which may contribute to the higher than previously reported dislocation rates.22 These results can be applied to the management of veterans seeking THA.

There have been conflicting reports regarding the impact a patient’s sex has on THA outcomes in the general population.23-26 This study found that female patients had higher rates of dislocation within 1 year of THA than male patients. This difference, which could be due to differences in baseline anatomic hip morphology between the sexes; females tend to have smaller femoral head sizes and less offset compared with males.27,28 However, this finding could have been confounded by the small number of female veterans in the study cohort.

A type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) diagnosis, which is a component of CCI, trended toward increased risk of prosthetic hip dislocation. Multiple studies have also discussed the increased risk of postoperative infections and revisions following THA in patients with T2DM.29-31 One study found T2DM to be an independent risk factor for immediate in-hospital postoperative complications following hip arthroplasty.32

Another factor that may influence postoperative dislocation risk is surgical approach. The posterior approach has historically been associated with higher rates of instability when compared to anterior or lateral THA.33 Researchers have also looked at the role that surgical approach plays in patients with prior LSF. Huebschmann et al confirmed that not only is LSF a significant risk factor for dislocation following THA, but anterior and laterally based surgical approaches may mitigate this risk.34

Limitations

As a retrospective cohort study, the reliability of the data hinges on complete documentation. Documentation of all encounters for dislocations was obtained from the VA Computerized Patient Record System, which may have led to some dislocation events being missed. However, as long as there was adequate postoperative follow-up, it was assumed all events outside the VA were included. Another limitation of this study was that male patients greatly outnumbered female patients, and this fact could limit the generalizability of findings to the population as a whole.

Conclusions

This study in a veteran population found that prior LSF and female sex were significant predictors for postoperative dislocation within 1 year of THA surgery. Additionally, the use of a dual-mobility liner was found to be protective against postoperative dislocation events. These data allow clinicians to better counsel veterans on the risk factors associated with postoperative dislocation and strategies to mitigate this risk.

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1455-1460. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01617

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:144-151. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00587

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:195-203. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015

- Yamato Y, Furuhashi H, Hasegawa T, et al. Simulation of implant impingement after spinal corrective fusion surgery in patients with previous total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective case series. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46:512-519. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003836

- Mudrick CA, Melvin JS, Springer BD. Late posterior hip instability after lumbar spinopelvic fusion. Arthroplast Today. 2015;1:25-29. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2015.05.002

- Diebo BG, Beyer GA, Grieco PW, et al. Complications in patients undergoing spinal fusion after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:412-417.doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000009 8.

- Sing DC, Barry JJ, Aguilar TU, et al. Prior lumbar spinal arthrodesis increases risk of prosthetic-related complication in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:227-232.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.069

- King CA, Landy DC, Martell JM, et al. Time to dislocation analysis of lumbar spine fusion following total hip arthroplasty: breaking up a happy home. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3768-3772. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.029

- Buckland AJ, Puvanesarajah V, Vigdorchik J, et al. Dislocation of a primary total hip arthroplasty is more common in patients with a lumbar spinal fusion. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:585-591.doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.BJJ-2016-0657.R1

- Pirruccio K, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. The burden of prosthetic hip dislocations in the United States is projected to significantly increase by 2035. Hip Int. 2021;31:714-721. doi:10.1177/1120700020923619

- Salib CG, Reina N, Perry KI, et al. Lumbar fusion involving the sacrum increases dislocation risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:198-206. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0754.R1

- An VVG, Phan K, Sivakumar BS, et al. Prior lumbar spinal fusion is associated with an increased risk of dislocation and revision in total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:297-300. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.040

- Klemt C, Padmanabha A, Tirumala V, et al. Lumbar spine fusion before revision total hip arthroplasty is associated with increased dislocation rates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e860-e868. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00824

- Gausden EB, Parhar HS, Popper JE, et al. Risk factors for early dislocation following primary elective total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1567-1571. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.034

- Malkani AL, Himschoot KJ, Ong KL, et al. Does timing of primary total hip arthroplasty prior to or after lumbar spine fusion have an effect on dislocation and revision rates?. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:907-911. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.009

- Parilla FW, Shah RR, Gordon AC, et al. Does it matter: total hip arthroplasty or lumbar spinal fusion first? Preoperative sagittal spinopelvic measurements guide patient-specific surgical strategies in patients requiring both. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2652-2662. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.053

- Chalmers BP, Syku M, Sculco TP, et al. Dual-mobility constructs in primary total hip arthroplasty in high-risk patients with spinal fusions: our institutional experience. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6:749-754. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2020.07.024

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Sachdeva S, et al. Use of dual mobility cups in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty with prior lumbar spine fusion. Int Orthop. 2020;44:857-862. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04507-y

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Yep PJ, et al. Dislocation rates of primary total hip arthroplasty in patients with prior lumbar spine fusion and lumbar degenerative disk disease with and without utilization of dual mobility cups: an American Joint Replacement Registry study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31:e271-e277. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00767

- Phan D, Bederman SS, Schwarzkopf R. The influence of sagittal spinal deformity on anteversion of the acetabular component in total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:1017-1023. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B8.35700

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.325223.

- Basques BA, Bell JA, Fillingham YA, et al. Gender differences for hip and knee arthroplasty: complications and healthcare utilization. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1593-1597.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.03.064

- Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Influence of patient-, design-, and surgery-related factors on rate of dislocation after primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1258-1263. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.017

- Chen A, Paxton L, Zheng X, et al. Association of sex with risk of 2-year revision among patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2110687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10687

- Inacio MCS, Ake CF, Paxton EW, et al. Sex and risk of hip implant failure: assessing total hip arthroplasty outcomes in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:435-441. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3271

- Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Liang MH, et al. Gender differences in patient preferences may underlie differential utilization of elective surgery. Am J Med. 1997;102:524-530. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00050-8

- Kostamo T, Bourne RB, Whittaker JP, et al. No difference in gender-specific hip replacement outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:135-140. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0466-2

- Papagelopoulos PJ, Idusuyi OB, Wallrichs SL, et al. Long term outcome and survivorship analysis of primary total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):124-132. doi:10.1097/00003086-199609000-00015

- Fitzgerald RH Jr, Nolan DR, Ilstrup DM, et al. Deep wound sepsis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:847-855.

- Blom AW, Brown J, Taylor AH, et al. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:688-691. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.86b5.14887

- Jain NB, Guller U, Pietrobon R, et al. Comorbidities increase complication rates in patients having arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:232-238. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000156479.97488.a2

- Docter S, Philpott HT, Godkin L, et al. Comparison of intra and post-operative complication rates among surgical approaches in Total Hip Arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2020;20:310-325. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2020.05.008

- Huebschmann NA, Lawrence KW, Robin JX, et al. Does surgical approach affect dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients who have prior lumbar spinal fusion? A retrospective analysis of 16,223 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:S306-S313. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2024.03.068

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is among the most common elective orthopedic procedures performed annually in the United States, with an estimated 635,000 to 909,000 THAs expected each year by 2030.1 Consequently, complication rates and revision surgeries related to THA have been increasing, along with the financial burden on the health care system.2-4 Optimizing outcomes for patients undergoing THA and identifying risk factors for treatment failure have become areas of focus.

Over the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in the effect of previous lumbar spine fusion (LSF) surgery on THA outcomes. Studies have explored the rates of complications, postoperative mobility, and THA implant impingement.5-8 However, the outcome receiving the most attention in recent literature is the rate and effect of dislocation in patients with lumbar fusion surgery. Large Medicare database analyses have discovered an association with increased rates of dislocations in patients with lumbar fusion surgeries compared with those without.9,10 Prosthetic hip dislocation is an expensive complication of THA and is projected to have greater impact through 2035 due to a growing number of THA procedures.11 Identifying risk factors associated with hip dislocation is paramount to mitigating its effect on patients who have undergone THA.

Recent research has found increased rates of THA dislocation and revision surgery in patients with LSF, with some studies showing previous LSF as the strongest independent predictor.6-16 However, controversy surrounds this relationship, including the sequence of procedures (LSF before or after THA), the time between procedures, and involvement of the sacrum in LSF. One study found that patients had a 106% increased risk of dislocation when LSF was performed before THA compared with patients who underwent LSF 5 years after undergoing THA, while another study showed no significant difference in dislocations pre- vs post-LSF.16,17 An additional study showed no significant difference in the rate of dislocation in patients without sacral involvement in the LSF, while also showing significantly higher rates of dislocation in LSF with sacral involvement.12 The researchers also found a trend toward more dislocations in longer lumbosacral fusions. Recent studies have also examined dislocation rates with lumbar fusion in patients treated with dual-mobility liners.18-20 The consensus from these studies is that dual-mobility liners significantly decrease the rate of dislocation in primary THAs with lumbar fusion.

The present study sought to determine the rates of hip dislocations in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital setting. To the authors’ knowledge, no retrospective study focusing on THAs in the veteran population has been performed. This study benefits from controlling for various surgeon techniques and surgical preferences when compared to large Medicare database studies because the orthopedic surgeon (ABK) only performed the posterior approach for all patients during the study period.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether the rates of hip dislocation would, in fact, be higher in patients with lumbar fusion surgery, as recent database studies suggest. Secondary objectives included determining whether patient characteristics, comorbidities, number of levels fused, or inclusion of the sacrum in the fusion construct influenced dislocation rates. Furthermore, VA Dayton Healthcare System (VADHS) began routine use of dual-mobility liners for lumbar fusion patients in 2018, allowing for examination of these patients.

Methods

The Wright State University and VADHS Institutional Review Board approved this study design. A retrospective review of all primary THAs at VADHS was performed to investigate the relationship between previous lumbar spine fusion and the incidence of THA revision. Manual chart review was performed for patients who underwent primary THA between January 2003, and December 2022. One surgeon performed all surgeries using only the posterior approach. Patients were not excluded if they had bilateral procedures and all eligible hips were included. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of fracture of the femoral head or femoral neck at the time of surgery were excluded. Additionally, only patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up data were included.

The primary outcome was dislocation within 12 months of THA; the primary independent variable was LSF prior to THA. Covariates included patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, with additional data collected on the number of levels fused, sacral spine involvement, revision rates, and use of dual-mobility liners. Year of surgery was also included in analyses to account for any changes that may have occurred during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4. Patients were grouped into 2 cohorts, depending on whether they had received LSF prior to THA. Analyses were adjusted for repeated measures to account for the small percentage of patients with bilateral procedures.

Univariate comparisons between cohorts for covariates, as well as rates of dislocation and revision, were performed using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous categorical variables. Significant comorbidities, as well as age, sex, BMI, liner type, LSF cohort, and surgery year, were included in a logistic regression model to determine what effect, if any, they had on the likelihood of dislocation. Variables were removed using a backward stepwise approach, starting with the nonsignificant variable effect with the lowest χ2 value, and continuing until reaching a final model where all remaining variable effects were significant. For the variables retained in the final model, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were derived, with dislocation designated as the event. Individual comorbidity subcomponents of the CCI were also analyzed for their effects on dislocation using backward stepwise logistic regression. A secondary analysis among patients with LSF tested for the influence of the number of vertebral levels fused, the presence or absence of sacral involvement in the fusion, and the use of dual-mobility liners on the likelihood of hip dislocation.

Results

The LSF cohort included 39 patients with THA and prior LSF, 3 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 42 hips. The non-LSF cohort included 813 patients with THA, 112 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 925 hips. The LSF and non-LSF cohorts did not differ significantly in age, sex, BMI, CCI, or revision rates (Table). The LSF cohort included a significantly higher percentage of hips receiving dual-mobility liners than did the non-LSF cohort (23.8% vs 0.6%; P < .001) and had more than twice the rate of dislocation (4 of 42 hips [9.5%] vs 35 of 925 hips [3.8%]), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .08).

The final logistic regression model with dislocation as the outcome was statistically significant (χ2, 17.47; P < .001) and retained 2 significant predictor variables: LSF cohort (χ2, 4.63; P = .03), and sex (χ2, 18.27; P < .001). Females were more likely than males to experience dislocation (OR, 5.84; 95% CI, 2.60-13.13; P < .001) as were patients who had LSF prior to THA (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.12-10.47; P = .03) (Figure). None of the CCI subcomponent comorbidities significantly affected the probability of dislocation (myocardial infarction, P = .46; congestive heart failure, P = .47; peripheral vascular disease, P = .97; stroke, P = .51; dementia, P = .99; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, P = .95; connective tissue disease, P = .25; peptic ulcer, P = .41; liver disease, P = .30; diabetes, P = .06; hemiplegia, P = .99; chronic kidney disease, P = .82; solid tumor, P = .90; leukemia, P = .99; lymphoma, P = .99; AIDS, P = .99). Within the LSF cohort, neither the number of levels fused (P = .83) nor sacral involvement (P = .42), significantly affected the probability of hip dislocation. None of the patients in either cohort who received dual-mobility liners subsequently dislocated their hips, nor did any of them require revision surgery.

Discussion

Spinopelvic biomechanics have been an area of increasing interest and research. Spinal fusion has been shown to alter the mobility of the pelvis and has been associated with decreased stability of THA implants.21 For example, in the setting of a fused spine, the lack of compensatory changes in pelvic tilt or acetabular anteversion when adjusting to a seated or standing position may predispose patients to impingement because the acetabular component is not properly positioned. Dual-mobility constructs mitigate this risk by providing an additional articulation, which increases jump distance and range of motion prior to impingement, thereby enhancing stability.

The use of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF has also been examined.18-20 These studies demonstrate a reduced risk of postoperative THA dislocation in patients with previous LSF. The rate of postoperative complications and revisions for LSF patients with dual-mobility liners was also found to be similar to that of THAs without dual-mobility in patients without prior LSF. This study focused on a veteran population to demonstrate the efficacy of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF. The results indicate that LSF prior to THA and female sex were predictors for prosthetic hip dislocations in the 12-month postoperative period in this patient population, which aligns with the current literature.

The dislocation rate in the LSF-THA group (9.5%) was higher than the dislocation rate in the control group (3.8%). Although not statistically significant in the univariate analysis, LSF was shown to be a significant risk factor after controlling for patient sex. Other studies have found the dislocation rate to be 3% to 7%, which is lower than the dislocation rate observed in this study.8,10,16

The reasons for this higher rate of dislocation are not entirely clear. A veteran population has poorer overall health than the general population, which may contribute to the higher than previously reported dislocation rates.22 These results can be applied to the management of veterans seeking THA.

There have been conflicting reports regarding the impact a patient’s sex has on THA outcomes in the general population.23-26 This study found that female patients had higher rates of dislocation within 1 year of THA than male patients. This difference, which could be due to differences in baseline anatomic hip morphology between the sexes; females tend to have smaller femoral head sizes and less offset compared with males.27,28 However, this finding could have been confounded by the small number of female veterans in the study cohort.

A type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) diagnosis, which is a component of CCI, trended toward increased risk of prosthetic hip dislocation. Multiple studies have also discussed the increased risk of postoperative infections and revisions following THA in patients with T2DM.29-31 One study found T2DM to be an independent risk factor for immediate in-hospital postoperative complications following hip arthroplasty.32

Another factor that may influence postoperative dislocation risk is surgical approach. The posterior approach has historically been associated with higher rates of instability when compared to anterior or lateral THA.33 Researchers have also looked at the role that surgical approach plays in patients with prior LSF. Huebschmann et al confirmed that not only is LSF a significant risk factor for dislocation following THA, but anterior and laterally based surgical approaches may mitigate this risk.34

Limitations

As a retrospective cohort study, the reliability of the data hinges on complete documentation. Documentation of all encounters for dislocations was obtained from the VA Computerized Patient Record System, which may have led to some dislocation events being missed. However, as long as there was adequate postoperative follow-up, it was assumed all events outside the VA were included. Another limitation of this study was that male patients greatly outnumbered female patients, and this fact could limit the generalizability of findings to the population as a whole.

Conclusions

This study in a veteran population found that prior LSF and female sex were significant predictors for postoperative dislocation within 1 year of THA surgery. Additionally, the use of a dual-mobility liner was found to be protective against postoperative dislocation events. These data allow clinicians to better counsel veterans on the risk factors associated with postoperative dislocation and strategies to mitigate this risk.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is among the most common elective orthopedic procedures performed annually in the United States, with an estimated 635,000 to 909,000 THAs expected each year by 2030.1 Consequently, complication rates and revision surgeries related to THA have been increasing, along with the financial burden on the health care system.2-4 Optimizing outcomes for patients undergoing THA and identifying risk factors for treatment failure have become areas of focus.

Over the last decade, there has been a renewed interest in the effect of previous lumbar spine fusion (LSF) surgery on THA outcomes. Studies have explored the rates of complications, postoperative mobility, and THA implant impingement.5-8 However, the outcome receiving the most attention in recent literature is the rate and effect of dislocation in patients with lumbar fusion surgery. Large Medicare database analyses have discovered an association with increased rates of dislocations in patients with lumbar fusion surgeries compared with those without.9,10 Prosthetic hip dislocation is an expensive complication of THA and is projected to have greater impact through 2035 due to a growing number of THA procedures.11 Identifying risk factors associated with hip dislocation is paramount to mitigating its effect on patients who have undergone THA.

Recent research has found increased rates of THA dislocation and revision surgery in patients with LSF, with some studies showing previous LSF as the strongest independent predictor.6-16 However, controversy surrounds this relationship, including the sequence of procedures (LSF before or after THA), the time between procedures, and involvement of the sacrum in LSF. One study found that patients had a 106% increased risk of dislocation when LSF was performed before THA compared with patients who underwent LSF 5 years after undergoing THA, while another study showed no significant difference in dislocations pre- vs post-LSF.16,17 An additional study showed no significant difference in the rate of dislocation in patients without sacral involvement in the LSF, while also showing significantly higher rates of dislocation in LSF with sacral involvement.12 The researchers also found a trend toward more dislocations in longer lumbosacral fusions. Recent studies have also examined dislocation rates with lumbar fusion in patients treated with dual-mobility liners.18-20 The consensus from these studies is that dual-mobility liners significantly decrease the rate of dislocation in primary THAs with lumbar fusion.

The present study sought to determine the rates of hip dislocations in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital setting. To the authors’ knowledge, no retrospective study focusing on THAs in the veteran population has been performed. This study benefits from controlling for various surgeon techniques and surgical preferences when compared to large Medicare database studies because the orthopedic surgeon (ABK) only performed the posterior approach for all patients during the study period.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether the rates of hip dislocation would, in fact, be higher in patients with lumbar fusion surgery, as recent database studies suggest. Secondary objectives included determining whether patient characteristics, comorbidities, number of levels fused, or inclusion of the sacrum in the fusion construct influenced dislocation rates. Furthermore, VA Dayton Healthcare System (VADHS) began routine use of dual-mobility liners for lumbar fusion patients in 2018, allowing for examination of these patients.

Methods

The Wright State University and VADHS Institutional Review Board approved this study design. A retrospective review of all primary THAs at VADHS was performed to investigate the relationship between previous lumbar spine fusion and the incidence of THA revision. Manual chart review was performed for patients who underwent primary THA between January 2003, and December 2022. One surgeon performed all surgeries using only the posterior approach. Patients were not excluded if they had bilateral procedures and all eligible hips were included. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of fracture of the femoral head or femoral neck at the time of surgery were excluded. Additionally, only patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up data were included.

The primary outcome was dislocation within 12 months of THA; the primary independent variable was LSF prior to THA. Covariates included patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, with additional data collected on the number of levels fused, sacral spine involvement, revision rates, and use of dual-mobility liners. Year of surgery was also included in analyses to account for any changes that may have occurred during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4. Patients were grouped into 2 cohorts, depending on whether they had received LSF prior to THA. Analyses were adjusted for repeated measures to account for the small percentage of patients with bilateral procedures.

Univariate comparisons between cohorts for covariates, as well as rates of dislocation and revision, were performed using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous categorical variables. Significant comorbidities, as well as age, sex, BMI, liner type, LSF cohort, and surgery year, were included in a logistic regression model to determine what effect, if any, they had on the likelihood of dislocation. Variables were removed using a backward stepwise approach, starting with the nonsignificant variable effect with the lowest χ2 value, and continuing until reaching a final model where all remaining variable effects were significant. For the variables retained in the final model, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were derived, with dislocation designated as the event. Individual comorbidity subcomponents of the CCI were also analyzed for their effects on dislocation using backward stepwise logistic regression. A secondary analysis among patients with LSF tested for the influence of the number of vertebral levels fused, the presence or absence of sacral involvement in the fusion, and the use of dual-mobility liners on the likelihood of hip dislocation.

Results

The LSF cohort included 39 patients with THA and prior LSF, 3 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 42 hips. The non-LSF cohort included 813 patients with THA, 112 of whom had bilateral procedures, for a total of 925 hips. The LSF and non-LSF cohorts did not differ significantly in age, sex, BMI, CCI, or revision rates (Table). The LSF cohort included a significantly higher percentage of hips receiving dual-mobility liners than did the non-LSF cohort (23.8% vs 0.6%; P < .001) and had more than twice the rate of dislocation (4 of 42 hips [9.5%] vs 35 of 925 hips [3.8%]), although this difference was not statistically significant (P = .08).

The final logistic regression model with dislocation as the outcome was statistically significant (χ2, 17.47; P < .001) and retained 2 significant predictor variables: LSF cohort (χ2, 4.63; P = .03), and sex (χ2, 18.27; P < .001). Females were more likely than males to experience dislocation (OR, 5.84; 95% CI, 2.60-13.13; P < .001) as were patients who had LSF prior to THA (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.12-10.47; P = .03) (Figure). None of the CCI subcomponent comorbidities significantly affected the probability of dislocation (myocardial infarction, P = .46; congestive heart failure, P = .47; peripheral vascular disease, P = .97; stroke, P = .51; dementia, P = .99; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, P = .95; connective tissue disease, P = .25; peptic ulcer, P = .41; liver disease, P = .30; diabetes, P = .06; hemiplegia, P = .99; chronic kidney disease, P = .82; solid tumor, P = .90; leukemia, P = .99; lymphoma, P = .99; AIDS, P = .99). Within the LSF cohort, neither the number of levels fused (P = .83) nor sacral involvement (P = .42), significantly affected the probability of hip dislocation. None of the patients in either cohort who received dual-mobility liners subsequently dislocated their hips, nor did any of them require revision surgery.

Discussion

Spinopelvic biomechanics have been an area of increasing interest and research. Spinal fusion has been shown to alter the mobility of the pelvis and has been associated with decreased stability of THA implants.21 For example, in the setting of a fused spine, the lack of compensatory changes in pelvic tilt or acetabular anteversion when adjusting to a seated or standing position may predispose patients to impingement because the acetabular component is not properly positioned. Dual-mobility constructs mitigate this risk by providing an additional articulation, which increases jump distance and range of motion prior to impingement, thereby enhancing stability.

The use of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF has also been examined.18-20 These studies demonstrate a reduced risk of postoperative THA dislocation in patients with previous LSF. The rate of postoperative complications and revisions for LSF patients with dual-mobility liners was also found to be similar to that of THAs without dual-mobility in patients without prior LSF. This study focused on a veteran population to demonstrate the efficacy of dual-mobility liners in patients with LSF. The results indicate that LSF prior to THA and female sex were predictors for prosthetic hip dislocations in the 12-month postoperative period in this patient population, which aligns with the current literature.

The dislocation rate in the LSF-THA group (9.5%) was higher than the dislocation rate in the control group (3.8%). Although not statistically significant in the univariate analysis, LSF was shown to be a significant risk factor after controlling for patient sex. Other studies have found the dislocation rate to be 3% to 7%, which is lower than the dislocation rate observed in this study.8,10,16

The reasons for this higher rate of dislocation are not entirely clear. A veteran population has poorer overall health than the general population, which may contribute to the higher than previously reported dislocation rates.22 These results can be applied to the management of veterans seeking THA.

There have been conflicting reports regarding the impact a patient’s sex has on THA outcomes in the general population.23-26 This study found that female patients had higher rates of dislocation within 1 year of THA than male patients. This difference, which could be due to differences in baseline anatomic hip morphology between the sexes; females tend to have smaller femoral head sizes and less offset compared with males.27,28 However, this finding could have been confounded by the small number of female veterans in the study cohort.

A type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) diagnosis, which is a component of CCI, trended toward increased risk of prosthetic hip dislocation. Multiple studies have also discussed the increased risk of postoperative infections and revisions following THA in patients with T2DM.29-31 One study found T2DM to be an independent risk factor for immediate in-hospital postoperative complications following hip arthroplasty.32

Another factor that may influence postoperative dislocation risk is surgical approach. The posterior approach has historically been associated with higher rates of instability when compared to anterior or lateral THA.33 Researchers have also looked at the role that surgical approach plays in patients with prior LSF. Huebschmann et al confirmed that not only is LSF a significant risk factor for dislocation following THA, but anterior and laterally based surgical approaches may mitigate this risk.34

Limitations

As a retrospective cohort study, the reliability of the data hinges on complete documentation. Documentation of all encounters for dislocations was obtained from the VA Computerized Patient Record System, which may have led to some dislocation events being missed. However, as long as there was adequate postoperative follow-up, it was assumed all events outside the VA were included. Another limitation of this study was that male patients greatly outnumbered female patients, and this fact could limit the generalizability of findings to the population as a whole.

Conclusions

This study in a veteran population found that prior LSF and female sex were significant predictors for postoperative dislocation within 1 year of THA surgery. Additionally, the use of a dual-mobility liner was found to be protective against postoperative dislocation events. These data allow clinicians to better counsel veterans on the risk factors associated with postoperative dislocation and strategies to mitigate this risk.

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1455-1460. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01617

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:144-151. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00587

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:195-203. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015

- Yamato Y, Furuhashi H, Hasegawa T, et al. Simulation of implant impingement after spinal corrective fusion surgery in patients with previous total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective case series. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46:512-519. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003836

- Mudrick CA, Melvin JS, Springer BD. Late posterior hip instability after lumbar spinopelvic fusion. Arthroplast Today. 2015;1:25-29. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2015.05.002

- Diebo BG, Beyer GA, Grieco PW, et al. Complications in patients undergoing spinal fusion after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:412-417.doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000009 8.

- Sing DC, Barry JJ, Aguilar TU, et al. Prior lumbar spinal arthrodesis increases risk of prosthetic-related complication in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:227-232.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.069

- King CA, Landy DC, Martell JM, et al. Time to dislocation analysis of lumbar spine fusion following total hip arthroplasty: breaking up a happy home. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3768-3772. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.029

- Buckland AJ, Puvanesarajah V, Vigdorchik J, et al. Dislocation of a primary total hip arthroplasty is more common in patients with a lumbar spinal fusion. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:585-591.doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.BJJ-2016-0657.R1

- Pirruccio K, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. The burden of prosthetic hip dislocations in the United States is projected to significantly increase by 2035. Hip Int. 2021;31:714-721. doi:10.1177/1120700020923619

- Salib CG, Reina N, Perry KI, et al. Lumbar fusion involving the sacrum increases dislocation risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:198-206. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0754.R1

- An VVG, Phan K, Sivakumar BS, et al. Prior lumbar spinal fusion is associated with an increased risk of dislocation and revision in total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:297-300. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.040

- Klemt C, Padmanabha A, Tirumala V, et al. Lumbar spine fusion before revision total hip arthroplasty is associated with increased dislocation rates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e860-e868. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00824

- Gausden EB, Parhar HS, Popper JE, et al. Risk factors for early dislocation following primary elective total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1567-1571. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.034

- Malkani AL, Himschoot KJ, Ong KL, et al. Does timing of primary total hip arthroplasty prior to or after lumbar spine fusion have an effect on dislocation and revision rates?. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:907-911. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.009

- Parilla FW, Shah RR, Gordon AC, et al. Does it matter: total hip arthroplasty or lumbar spinal fusion first? Preoperative sagittal spinopelvic measurements guide patient-specific surgical strategies in patients requiring both. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2652-2662. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.053

- Chalmers BP, Syku M, Sculco TP, et al. Dual-mobility constructs in primary total hip arthroplasty in high-risk patients with spinal fusions: our institutional experience. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6:749-754. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2020.07.024

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Sachdeva S, et al. Use of dual mobility cups in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty with prior lumbar spine fusion. Int Orthop. 2020;44:857-862. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04507-y

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Yep PJ, et al. Dislocation rates of primary total hip arthroplasty in patients with prior lumbar spine fusion and lumbar degenerative disk disease with and without utilization of dual mobility cups: an American Joint Replacement Registry study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31:e271-e277. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00767

- Phan D, Bederman SS, Schwarzkopf R. The influence of sagittal spinal deformity on anteversion of the acetabular component in total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:1017-1023. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B8.35700

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.325223.

- Basques BA, Bell JA, Fillingham YA, et al. Gender differences for hip and knee arthroplasty: complications and healthcare utilization. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1593-1597.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.03.064

- Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Influence of patient-, design-, and surgery-related factors on rate of dislocation after primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1258-1263. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.017

- Chen A, Paxton L, Zheng X, et al. Association of sex with risk of 2-year revision among patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2110687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10687

- Inacio MCS, Ake CF, Paxton EW, et al. Sex and risk of hip implant failure: assessing total hip arthroplasty outcomes in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:435-441. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3271

- Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Liang MH, et al. Gender differences in patient preferences may underlie differential utilization of elective surgery. Am J Med. 1997;102:524-530. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00050-8

- Kostamo T, Bourne RB, Whittaker JP, et al. No difference in gender-specific hip replacement outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:135-140. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0466-2

- Papagelopoulos PJ, Idusuyi OB, Wallrichs SL, et al. Long term outcome and survivorship analysis of primary total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):124-132. doi:10.1097/00003086-199609000-00015

- Fitzgerald RH Jr, Nolan DR, Ilstrup DM, et al. Deep wound sepsis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:847-855.

- Blom AW, Brown J, Taylor AH, et al. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:688-691. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.86b5.14887

- Jain NB, Guller U, Pietrobon R, et al. Comorbidities increase complication rates in patients having arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:232-238. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000156479.97488.a2

- Docter S, Philpott HT, Godkin L, et al. Comparison of intra and post-operative complication rates among surgical approaches in Total Hip Arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2020;20:310-325. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2020.05.008

- Huebschmann NA, Lawrence KW, Robin JX, et al. Does surgical approach affect dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients who have prior lumbar spinal fusion? A retrospective analysis of 16,223 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:S306-S313. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2024.03.068

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1455-1460. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01617

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:144-151. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00587

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, et al. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:195-203. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015

- Yamato Y, Furuhashi H, Hasegawa T, et al. Simulation of implant impingement after spinal corrective fusion surgery in patients with previous total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective case series. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46:512-519. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003836

- Mudrick CA, Melvin JS, Springer BD. Late posterior hip instability after lumbar spinopelvic fusion. Arthroplast Today. 2015;1:25-29. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2015.05.002

- Diebo BG, Beyer GA, Grieco PW, et al. Complications in patients undergoing spinal fusion after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:412-417.doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000009 8.

- Sing DC, Barry JJ, Aguilar TU, et al. Prior lumbar spinal arthrodesis increases risk of prosthetic-related complication in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:227-232.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.069

- King CA, Landy DC, Martell JM, et al. Time to dislocation analysis of lumbar spine fusion following total hip arthroplasty: breaking up a happy home. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3768-3772. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.029

- Buckland AJ, Puvanesarajah V, Vigdorchik J, et al. Dislocation of a primary total hip arthroplasty is more common in patients with a lumbar spinal fusion. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:585-591.doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B5.BJJ-2016-0657.R1

- Pirruccio K, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. The burden of prosthetic hip dislocations in the United States is projected to significantly increase by 2035. Hip Int. 2021;31:714-721. doi:10.1177/1120700020923619

- Salib CG, Reina N, Perry KI, et al. Lumbar fusion involving the sacrum increases dislocation risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:198-206. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0754.R1

- An VVG, Phan K, Sivakumar BS, et al. Prior lumbar spinal fusion is associated with an increased risk of dislocation and revision in total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:297-300. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.040

- Klemt C, Padmanabha A, Tirumala V, et al. Lumbar spine fusion before revision total hip arthroplasty is associated with increased dislocation rates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e860-e868. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00824

- Gausden EB, Parhar HS, Popper JE, et al. Risk factors for early dislocation following primary elective total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1567-1571. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.034

- Malkani AL, Himschoot KJ, Ong KL, et al. Does timing of primary total hip arthroplasty prior to or after lumbar spine fusion have an effect on dislocation and revision rates?. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:907-911. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.009

- Parilla FW, Shah RR, Gordon AC, et al. Does it matter: total hip arthroplasty or lumbar spinal fusion first? Preoperative sagittal spinopelvic measurements guide patient-specific surgical strategies in patients requiring both. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2652-2662. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.053

- Chalmers BP, Syku M, Sculco TP, et al. Dual-mobility constructs in primary total hip arthroplasty in high-risk patients with spinal fusions: our institutional experience. Arthroplast Today. 2020;6:749-754. doi:10.1016/j.artd.2020.07.024

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Sachdeva S, et al. Use of dual mobility cups in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty with prior lumbar spine fusion. Int Orthop. 2020;44:857-862. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04507-y

- Nessler JM, Malkani AL, Yep PJ, et al. Dislocation rates of primary total hip arthroplasty in patients with prior lumbar spine fusion and lumbar degenerative disk disease with and without utilization of dual mobility cups: an American Joint Replacement Registry study. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31:e271-e277. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00767

- Phan D, Bederman SS, Schwarzkopf R. The influence of sagittal spinal deformity on anteversion of the acetabular component in total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:1017-1023. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B8.35700

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.325223.

- Basques BA, Bell JA, Fillingham YA, et al. Gender differences for hip and knee arthroplasty: complications and healthcare utilization. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1593-1597.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.03.064

- Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Influence of patient-, design-, and surgery-related factors on rate of dislocation after primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1258-1263. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.017

- Chen A, Paxton L, Zheng X, et al. Association of sex with risk of 2-year revision among patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2110687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10687

- Inacio MCS, Ake CF, Paxton EW, et al. Sex and risk of hip implant failure: assessing total hip arthroplasty outcomes in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:435-441. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3271

- Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Liang MH, et al. Gender differences in patient preferences may underlie differential utilization of elective surgery. Am J Med. 1997;102:524-530. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00050-8

- Kostamo T, Bourne RB, Whittaker JP, et al. No difference in gender-specific hip replacement outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:135-140. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0466-2

- Papagelopoulos PJ, Idusuyi OB, Wallrichs SL, et al. Long term outcome and survivorship analysis of primary total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):124-132. doi:10.1097/00003086-199609000-00015

- Fitzgerald RH Jr, Nolan DR, Ilstrup DM, et al. Deep wound sepsis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:847-855.

- Blom AW, Brown J, Taylor AH, et al. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:688-691. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.86b5.14887

- Jain NB, Guller U, Pietrobon R, et al. Comorbidities increase complication rates in patients having arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:232-238. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000156479.97488.a2

- Docter S, Philpott HT, Godkin L, et al. Comparison of intra and post-operative complication rates among surgical approaches in Total Hip Arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2020;20:310-325. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2020.05.008

- Huebschmann NA, Lawrence KW, Robin JX, et al. Does surgical approach affect dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients who have prior lumbar spinal fusion? A retrospective analysis of 16,223 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:S306-S313. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2024.03.068

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population

Effects of Lumbar Fusion and Dual-Mobility Liners on Dislocation Rates Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in a Veteran Population