User login

Cervical cancer in African American women: Optimizing prevention to reduce disparities

Primary care providers play a crucial role in cancer control, including screening and follow-up.1,2 In particular, they are often responsible for performing the initial screening and, when necessary, discussing appropriate treatment options. However, cancer screening practices in primary care can vary significantly, leading to disparities in access to these services.3

Arvizo and Mahdi,4 in this issue of the Journal, discuss disparities in cervical cancer screening, noting that African American women have a higher risk of developing and dying of cervical cancer than white women, possibly because they are diagnosed at a later stage and have lower stage-specific survival rates. The authors state that equal access to healthcare may help mitigate these factors, and they also discuss how primary care providers can reduce these disparities.

PRIORITIZING CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Even in patients who have access to regular primary care, other barriers to cancer screening may exist. A 2014 study used self-reported data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey to assess barriers to cervical cancer screening in older women (ages 40 to 65) who reported having health insurance and a personal healthcare provider.5 Those who were never or rarely screened for cervical cancer were more likely than those who were regularly screened to have a chronic condition, such as heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, depression, kidney disease, or diabetes.

This finding suggests that cancer screening may be a low priority during an adult primary care visit in which multiple chronic diseases must be addressed. To reduce disparities in cancer screening, primary care systems need to be designed to optimize delivery of preventive care and disease management using a team approach.

SYSTEMATIC FOLLOW-UP

Arvizo and Mahdi also discuss the follow-up of abnormal screening Papanicolaou (Pap) smears. While appropriate follow-up is a key factor in the management of cervical dysplasia, follow-up rates vary among African American women. System-level interventions such as the use of an electronic medical record-based tracking system in primary care settings6 with established protocols for follow-up may be effective.

But even with such systems in place, patients may face psychosocial barriers (eg, lack of health literacy, distress after receiving an abnormal cervical cytology test result7) that prevent them from seeking additional care. To improve follow-up rates, providers must be aware of these barriers and know how to address them through effective communication.

VACCINATION FOR HPV

Finally, the association between human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer makes HPV vaccination a crucial step in cervical cancer prevention. Continued provider education regarding HPV vaccination can improve knowledge about the HPV vaccine,8 as well as improve vaccination rates.9 The recent approval of a 2-dose vaccine schedule for younger girls10 may also help improve vaccine series completion rates.

The authors also suggest that primary care providers counsel all patients about risk factors for cervical cancer, including unsafe sex practices and tobacco use.

OPTIMIZING SCREENING AND PREVENTION

I commend the authors for their discussion of cervical cancer disparities and for raising awareness of the important role primary care providers play in reducing these disparities. Improving cervical cancer screening rates and follow-up will require providers and patients to be aware of cervical cancer risk factors. Further, system-level practice interventions will optimize primary care providers’ ability to engage patients in cancer screening conversations and ensure timely follow-up of screening tests.

- Emery JD, Shaw K, Williams B, et al. The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11:38–48.

- Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:1231–1272.

- Martires KJ, Kurlander DE, Minwell GJ, Dahms EB, Bordeaux JS. Patterns of cancer screening in primary care from 2005 to 2010. Cancer 2014; 120:253–261.

- Arvizo C, Mahdi H. Disparities in cervical cancer in African-American women: what primary care physicians can do. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:788–794.

- Crawford A, Benard V, King J, Thomas CC. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening in women with access to care, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2016; 13:E154.

- Dupuis EA, White HF, Newman D, Sobieraj JE, Gokhale M, Freund KM. Tracking abnormal cervical cancer screening: evaluation of an EMR-based intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25:575–580.

- Hui SK, Miller SM, Wen KY, et al. Psychosocial barriers to follow-up adherence after an abnormal cervical cytology test result among low-income, inner-city women. J Prim Care Community Health 2014; 5:234–241.

- Berenson AB, Rahman M, Hirth JM, Rupp RE, Sarpong KO. A brief educational intervention increases providers’ human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:1331–1336.

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015; 33:1223–1229.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:1405–1408.

Primary care providers play a crucial role in cancer control, including screening and follow-up.1,2 In particular, they are often responsible for performing the initial screening and, when necessary, discussing appropriate treatment options. However, cancer screening practices in primary care can vary significantly, leading to disparities in access to these services.3

Arvizo and Mahdi,4 in this issue of the Journal, discuss disparities in cervical cancer screening, noting that African American women have a higher risk of developing and dying of cervical cancer than white women, possibly because they are diagnosed at a later stage and have lower stage-specific survival rates. The authors state that equal access to healthcare may help mitigate these factors, and they also discuss how primary care providers can reduce these disparities.

PRIORITIZING CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Even in patients who have access to regular primary care, other barriers to cancer screening may exist. A 2014 study used self-reported data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey to assess barriers to cervical cancer screening in older women (ages 40 to 65) who reported having health insurance and a personal healthcare provider.5 Those who were never or rarely screened for cervical cancer were more likely than those who were regularly screened to have a chronic condition, such as heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, depression, kidney disease, or diabetes.

This finding suggests that cancer screening may be a low priority during an adult primary care visit in which multiple chronic diseases must be addressed. To reduce disparities in cancer screening, primary care systems need to be designed to optimize delivery of preventive care and disease management using a team approach.

SYSTEMATIC FOLLOW-UP

Arvizo and Mahdi also discuss the follow-up of abnormal screening Papanicolaou (Pap) smears. While appropriate follow-up is a key factor in the management of cervical dysplasia, follow-up rates vary among African American women. System-level interventions such as the use of an electronic medical record-based tracking system in primary care settings6 with established protocols for follow-up may be effective.

But even with such systems in place, patients may face psychosocial barriers (eg, lack of health literacy, distress after receiving an abnormal cervical cytology test result7) that prevent them from seeking additional care. To improve follow-up rates, providers must be aware of these barriers and know how to address them through effective communication.

VACCINATION FOR HPV

Finally, the association between human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer makes HPV vaccination a crucial step in cervical cancer prevention. Continued provider education regarding HPV vaccination can improve knowledge about the HPV vaccine,8 as well as improve vaccination rates.9 The recent approval of a 2-dose vaccine schedule for younger girls10 may also help improve vaccine series completion rates.

The authors also suggest that primary care providers counsel all patients about risk factors for cervical cancer, including unsafe sex practices and tobacco use.

OPTIMIZING SCREENING AND PREVENTION

I commend the authors for their discussion of cervical cancer disparities and for raising awareness of the important role primary care providers play in reducing these disparities. Improving cervical cancer screening rates and follow-up will require providers and patients to be aware of cervical cancer risk factors. Further, system-level practice interventions will optimize primary care providers’ ability to engage patients in cancer screening conversations and ensure timely follow-up of screening tests.

Primary care providers play a crucial role in cancer control, including screening and follow-up.1,2 In particular, they are often responsible for performing the initial screening and, when necessary, discussing appropriate treatment options. However, cancer screening practices in primary care can vary significantly, leading to disparities in access to these services.3

Arvizo and Mahdi,4 in this issue of the Journal, discuss disparities in cervical cancer screening, noting that African American women have a higher risk of developing and dying of cervical cancer than white women, possibly because they are diagnosed at a later stage and have lower stage-specific survival rates. The authors state that equal access to healthcare may help mitigate these factors, and they also discuss how primary care providers can reduce these disparities.

PRIORITIZING CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Even in patients who have access to regular primary care, other barriers to cancer screening may exist. A 2014 study used self-reported data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey to assess barriers to cervical cancer screening in older women (ages 40 to 65) who reported having health insurance and a personal healthcare provider.5 Those who were never or rarely screened for cervical cancer were more likely than those who were regularly screened to have a chronic condition, such as heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, depression, kidney disease, or diabetes.

This finding suggests that cancer screening may be a low priority during an adult primary care visit in which multiple chronic diseases must be addressed. To reduce disparities in cancer screening, primary care systems need to be designed to optimize delivery of preventive care and disease management using a team approach.

SYSTEMATIC FOLLOW-UP

Arvizo and Mahdi also discuss the follow-up of abnormal screening Papanicolaou (Pap) smears. While appropriate follow-up is a key factor in the management of cervical dysplasia, follow-up rates vary among African American women. System-level interventions such as the use of an electronic medical record-based tracking system in primary care settings6 with established protocols for follow-up may be effective.

But even with such systems in place, patients may face psychosocial barriers (eg, lack of health literacy, distress after receiving an abnormal cervical cytology test result7) that prevent them from seeking additional care. To improve follow-up rates, providers must be aware of these barriers and know how to address them through effective communication.

VACCINATION FOR HPV

Finally, the association between human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer makes HPV vaccination a crucial step in cervical cancer prevention. Continued provider education regarding HPV vaccination can improve knowledge about the HPV vaccine,8 as well as improve vaccination rates.9 The recent approval of a 2-dose vaccine schedule for younger girls10 may also help improve vaccine series completion rates.

The authors also suggest that primary care providers counsel all patients about risk factors for cervical cancer, including unsafe sex practices and tobacco use.

OPTIMIZING SCREENING AND PREVENTION

I commend the authors for their discussion of cervical cancer disparities and for raising awareness of the important role primary care providers play in reducing these disparities. Improving cervical cancer screening rates and follow-up will require providers and patients to be aware of cervical cancer risk factors. Further, system-level practice interventions will optimize primary care providers’ ability to engage patients in cancer screening conversations and ensure timely follow-up of screening tests.

- Emery JD, Shaw K, Williams B, et al. The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11:38–48.

- Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:1231–1272.

- Martires KJ, Kurlander DE, Minwell GJ, Dahms EB, Bordeaux JS. Patterns of cancer screening in primary care from 2005 to 2010. Cancer 2014; 120:253–261.

- Arvizo C, Mahdi H. Disparities in cervical cancer in African-American women: what primary care physicians can do. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:788–794.

- Crawford A, Benard V, King J, Thomas CC. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening in women with access to care, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2016; 13:E154.

- Dupuis EA, White HF, Newman D, Sobieraj JE, Gokhale M, Freund KM. Tracking abnormal cervical cancer screening: evaluation of an EMR-based intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25:575–580.

- Hui SK, Miller SM, Wen KY, et al. Psychosocial barriers to follow-up adherence after an abnormal cervical cytology test result among low-income, inner-city women. J Prim Care Community Health 2014; 5:234–241.

- Berenson AB, Rahman M, Hirth JM, Rupp RE, Sarpong KO. A brief educational intervention increases providers’ human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:1331–1336.

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015; 33:1223–1229.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:1405–1408.

- Emery JD, Shaw K, Williams B, et al. The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11:38–48.

- Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:1231–1272.

- Martires KJ, Kurlander DE, Minwell GJ, Dahms EB, Bordeaux JS. Patterns of cancer screening in primary care from 2005 to 2010. Cancer 2014; 120:253–261.

- Arvizo C, Mahdi H. Disparities in cervical cancer in African-American women: what primary care physicians can do. Cleve Clin J Med 2017; 84:788–794.

- Crawford A, Benard V, King J, Thomas CC. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening in women with access to care, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2016; 13:E154.

- Dupuis EA, White HF, Newman D, Sobieraj JE, Gokhale M, Freund KM. Tracking abnormal cervical cancer screening: evaluation of an EMR-based intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25:575–580.

- Hui SK, Miller SM, Wen KY, et al. Psychosocial barriers to follow-up adherence after an abnormal cervical cytology test result among low-income, inner-city women. J Prim Care Community Health 2014; 5:234–241.

- Berenson AB, Rahman M, Hirth JM, Rupp RE, Sarpong KO. A brief educational intervention increases providers’ human papillomavirus vaccine knowledge. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015; 11:1331–1336.

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015; 33:1223–1229.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:1405–1408.

Medical scribes: How do their notes stack up?

ABSTRACT

Objective Medical scribes are increasingly employed to improve physician efficiency with regard to the electronic medical record (EMR). The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes is not known. To assess the effect, we conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory progress notes written before and after 8 practice sites transitioned to the use of medical assistants as scribes.

Methods The Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9) was used to compare the quality of outpatient progress notes written by medical assistant scribes with the quality of notes written by 18 primary care physicians working without a scribe. The notes pertained to diabetes encounters and same-day appointments and were written during the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after scribes were employed (scribe period).

Results One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 from the scribe period were reviewed. Scribed notes were rated higher in overall quality than unscribed notes (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribed notes vs 28.9 for nonscribed notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible. The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same-day appointments, scribed and nonscribed notes did not differ in quality. The total word count of all scribed and nonscribed notes was similar (mean words 618, standard deviation (SD) 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

Conclusions In this retrospective review, ambulatory notes were of higher quality when medical assistants acted as scribes than when physicians wrote them alone, at least for diabetes visits. Our findings may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the clinical care team. As the use of medical scribes expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on other aspects of care quality.

Team-based models of primary care delivery may incorporate medical scribes to improve efficiency of electronic documentation.1-4 The employment of medical scribes has grown rapidly, and it is estimated that within several years there may be one scribe for every 9 physicians.3

Accurate documentation is important to providing high-quality patient care but can take a significant amount of time. Attending physicians have been estimated to spend as long as 52 minutes per day authoring notes.5 Medical scribes can help physicians improve the efficiency of electronic documentation6 and save time.2 Using scribes can also improve physician productivity7-10 and thereby potentially increase access to care. The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes, however, is unknown.

A team-based care delivery model in our health system’s primary care clinics uses medical assistants to scribe notes during the outpatient encounter. We hypothesized that outpatient notes written by medical assistant scribes would be of similar quality to notes written by the same group of physicians without a scribe.

METHODS

Study design and sample

We conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory notes from 18 primary care physicians at 8 practice sites in our health system who had adopted a care model in which medical assistants act as scribes. Each physician works with 2 medical assistants. To train for the new model, the physician and medical assistants participated in 2 training sessions of 2 hours each and a half day of clinic observation and evaluation with a project manager.

Of the 18 primary care physicians included in this study, none had less than one year of experience in our health system. Tenure ranged from one to 24 years with a mean of 11.3 years.

For each participating provider, we requested all available outpatient progress notes with either an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code for diabetes or a designation of “same day” for the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after employing scribes (scribe period). We chose diabetes encounters as examples of notes addressing chronic disease management and same-day encounters as examples of problem-focused notes because these 2 types of encounters are common in outpatient primary care practice.

Note quality was evaluated using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9), a validated instrument designed for this purpose, comprising 9 items rated subjectively on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all, 5= extremely). The items assess whether notes are up-to-date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, and internally consistent.11,12 The PDQI-9 has been applied previously in inpatient12 and outpatient settings.13

While the PDQI-9 is a validated tool, it relies on subjective ratings of note quality by the reviewer. To control for the subjective nature of the ratings, an experienced internist and an internal medicine resident coded 10 progress notes separately using the PDQI-9 and discussed the results. The process was repeated for a total of 20 notes, after which consensus was reached with >70% agreement on each attribute of the PDQI-9, suggesting that the resident’s ratings were reliable when compared with those of an experienced practicing physician.

The resident then evaluated a random sample of notes written by each physician for diabetes or same-day appointments in the pre-scribe and scribe periods. Word counts for the entire note were measured. The notes used to establish the reliability of the ratings were excluded from the analysis for this study.

Data analysis

We used linear mixed-effects models to examine note quality measures by adjusting for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. Least-squares estimates were derived; the results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

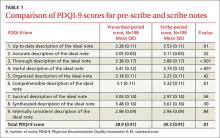

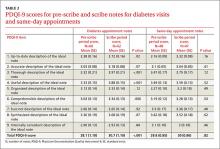

RESULTS

One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 notes from the scribe period were reviewed. Compared with notes written by a physician alone, scribed notes were rated slightly higher in overall quality (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribe notes vs 28.9 for pre-scribe notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible (TABLES 1 AND 2). The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same day appointments, scribed notes did not differ in quality from nonscribed notes (TABLE 2). Total word count did not vary significantly between all scribe and pre-scribe notes (mean words 618, SD 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective review of ambulatory notes, progress notes written by medical assistant scribes were of higher quality than notes physicians wrote alone, at least for diabetes visits. Scribe and pre-scribe notes were of similar quality for problem-focused same-day visits. This is the first study of which we are aware that compares the quality of scribed notes with notes written by physicians.

Quality scribe notes can save physician time. The progress note is an important vehicle for describing care provided and transferring information among physicians caring for the same patient. Writing a note, however, adds a considerable amount of time to the physician’s workflow. Using a scribe can decrease the time burden of note writing, and if scribed notes are of similar or better quality, this practice innovation can allow the physician to focus more on clinical than clerical tasks.

Over-documentation is a possible concern. While implementation of the EMR may improve certain aspects of quality of care delivered14,15 and note quality,16 concern has been raised about over-documentation related to the connection between documentation and reimbursement.17 In our study, we found that physician notes and scribed notes for both diabetes and same-day encounters often used EMR-based note templates, which can lead to over-documentation.

In general, both physician and scribed notes were rated to be of average to low quality because none of the mean scores on the 9 individual components of the PDQI-9 reached 4.0. Scribed notes were not inaccurate and had word counts similar to physician notes.

Scribing has potential drawbacks—and benefits. Drawbacks to scribing have not been well-studied. It has been suggested that using scribes to work around the EMR may actually hinder its further advancement because scribing insulates physicians from the inefficiencies of current EMRs and will not spur demands for improvements.3 Inaccurate or poor-quality notes could represent another downside to scribing, although concern about the quality of notes has not been documented. Our results suggest the opposite may be true.

Note quality has not been associated with quality of care as assessed by clinical quality scores,13 but using scribes may improve the quality of care in other ways. For example, the EMR may negatively affect patient-physician communication,18,19 and freeing the physician from documentation may improve the interaction.8,20 Incorporating scribing into practice may also improve the physician experience,9,10,21,22 a possible benefit that we did not measure.

We also did not measure the cost of using a scribe to assist in EMR documentation compared with the cost of physician time spent in performing this task. If the scribe model were associated with cost savings through increased physician productivity, as well as improved physician experience, future EMR development might best focus on planned utilization by physician-scribe teams.

Study limitations. The study was conducted in a single health system, although at 8 different practice sites. The sites all used the same EMR, but templates used for documentation could be individualized by the physician and medical assistant team, so our findings may reflect variation in template design. Our analysis did adjust for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. The selection of note types in our study may make our results less generalizable to other encounter types. Our sample was not large enough to detect variations in note quality among different providers and scribes.

The ratings on the PDQI-9 may be subjective, and the reviewers were not blinded to whether a scribe was used to write the note. The differences in PDQI-9 scores were small. Although statistically significant, they may not significantly affect clinical practice. Our care model is unique in that scribes are active members of the clinical care team; the higher quality of scribed notes we found may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the team.

Future research directions. In our study, medical assistants acting as scribes composed progress notes of similar or higher quality than physicians who wrote notes alone, although all notes were of generally average quality. As the use of scribes in medicine expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on primary care workflow, quality and cost of care delivered, and quality of physician experience.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anita D. Misra-Hebert, MD, MPH, Center for Value-Based Care Research, Medicine Institute, 9500 Euclid Avenue, G10, Cleveland, OH 44195; [email protected].

1. Bodenheimer T, Willard-Grace R, Ghorob A. Expanding the roles of medical assistants: Who does what in primary care? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1025-1026.

2. Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, et al. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1190-1193.

3. Gellert GA, Ramirea R, Webster S. The rise of the medical scribe industry: Implications for the advancement of electronic health records. JAMA. 2015;313:1315-1316.

4. Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:371-381.

5. Hripcsak G, Vawdrey DK, Fred MR, et al. Use of electronic clinical documentation: time spent and team interactions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:112-117.

6. Silverman L. Scribes Are Back, Helping Doctors Tackle Electronic Medical Records. NPR.org. Available at: www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/21/303406306/scribes-are-back-helping-doctors-tackle-electronic-medical-records. Accessed April 23, 2014.

7. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

8. Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:399-406.

9. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

10. Allen B, Banapoor B, Weeks EC, et al. An assessment of emergency department throughput and provider satisfaction after the implementation of a scribe program. Advances in Emergency Medicine. 2014;2014:e517319.

11. Stetson PD, Morrison FP, Bakken S, et al. Preliminary development of the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:534-541.

12. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, et al. Assessing electronic note quality using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3:164-174.

13. Edwards ST, Neri PM, Volk LA, et al. Association of note quality and quality of care: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;23:406-413.

14. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1066-1069.

15. Samal L, Wright A, Healey MJ, et al. Meaningful use and quality of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:997-998.

16. Burke HB, Sessums LL, Hoang A, et al. Electronic health records improve clinical note quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:199-205.

17. Sheehy AM, Weissburg DJ, Dean SM. The role of copy-and-paste in the hospital electronic health record. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1217-1218.

18. Shachak A, Hadas-Dayagi M, Ziv A, et al. Primary care physicians’ use of an electronic medical record system: a cognitive task analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:341-348.

19. Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient-doctor communication during consultation: a narrative literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:641-649.

20. Misra-Hebert AD, Rabovsky A, Yan C, et al. A team-based model of primary care delivery and physician-patient interaction. Am J Med. 2015;128:1025-1028.

21. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

22. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.

ABSTRACT

Objective Medical scribes are increasingly employed to improve physician efficiency with regard to the electronic medical record (EMR). The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes is not known. To assess the effect, we conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory progress notes written before and after 8 practice sites transitioned to the use of medical assistants as scribes.

Methods The Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9) was used to compare the quality of outpatient progress notes written by medical assistant scribes with the quality of notes written by 18 primary care physicians working without a scribe. The notes pertained to diabetes encounters and same-day appointments and were written during the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after scribes were employed (scribe period).

Results One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 from the scribe period were reviewed. Scribed notes were rated higher in overall quality than unscribed notes (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribed notes vs 28.9 for nonscribed notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible. The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same-day appointments, scribed and nonscribed notes did not differ in quality. The total word count of all scribed and nonscribed notes was similar (mean words 618, standard deviation (SD) 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

Conclusions In this retrospective review, ambulatory notes were of higher quality when medical assistants acted as scribes than when physicians wrote them alone, at least for diabetes visits. Our findings may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the clinical care team. As the use of medical scribes expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on other aspects of care quality.

Team-based models of primary care delivery may incorporate medical scribes to improve efficiency of electronic documentation.1-4 The employment of medical scribes has grown rapidly, and it is estimated that within several years there may be one scribe for every 9 physicians.3

Accurate documentation is important to providing high-quality patient care but can take a significant amount of time. Attending physicians have been estimated to spend as long as 52 minutes per day authoring notes.5 Medical scribes can help physicians improve the efficiency of electronic documentation6 and save time.2 Using scribes can also improve physician productivity7-10 and thereby potentially increase access to care. The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes, however, is unknown.

A team-based care delivery model in our health system’s primary care clinics uses medical assistants to scribe notes during the outpatient encounter. We hypothesized that outpatient notes written by medical assistant scribes would be of similar quality to notes written by the same group of physicians without a scribe.

METHODS

Study design and sample

We conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory notes from 18 primary care physicians at 8 practice sites in our health system who had adopted a care model in which medical assistants act as scribes. Each physician works with 2 medical assistants. To train for the new model, the physician and medical assistants participated in 2 training sessions of 2 hours each and a half day of clinic observation and evaluation with a project manager.

Of the 18 primary care physicians included in this study, none had less than one year of experience in our health system. Tenure ranged from one to 24 years with a mean of 11.3 years.

For each participating provider, we requested all available outpatient progress notes with either an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code for diabetes or a designation of “same day” for the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after employing scribes (scribe period). We chose diabetes encounters as examples of notes addressing chronic disease management and same-day encounters as examples of problem-focused notes because these 2 types of encounters are common in outpatient primary care practice.

Note quality was evaluated using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9), a validated instrument designed for this purpose, comprising 9 items rated subjectively on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all, 5= extremely). The items assess whether notes are up-to-date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, and internally consistent.11,12 The PDQI-9 has been applied previously in inpatient12 and outpatient settings.13

While the PDQI-9 is a validated tool, it relies on subjective ratings of note quality by the reviewer. To control for the subjective nature of the ratings, an experienced internist and an internal medicine resident coded 10 progress notes separately using the PDQI-9 and discussed the results. The process was repeated for a total of 20 notes, after which consensus was reached with >70% agreement on each attribute of the PDQI-9, suggesting that the resident’s ratings were reliable when compared with those of an experienced practicing physician.

The resident then evaluated a random sample of notes written by each physician for diabetes or same-day appointments in the pre-scribe and scribe periods. Word counts for the entire note were measured. The notes used to establish the reliability of the ratings were excluded from the analysis for this study.

Data analysis

We used linear mixed-effects models to examine note quality measures by adjusting for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. Least-squares estimates were derived; the results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 notes from the scribe period were reviewed. Compared with notes written by a physician alone, scribed notes were rated slightly higher in overall quality (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribe notes vs 28.9 for pre-scribe notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible (TABLES 1 AND 2). The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same day appointments, scribed notes did not differ in quality from nonscribed notes (TABLE 2). Total word count did not vary significantly between all scribe and pre-scribe notes (mean words 618, SD 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective review of ambulatory notes, progress notes written by medical assistant scribes were of higher quality than notes physicians wrote alone, at least for diabetes visits. Scribe and pre-scribe notes were of similar quality for problem-focused same-day visits. This is the first study of which we are aware that compares the quality of scribed notes with notes written by physicians.

Quality scribe notes can save physician time. The progress note is an important vehicle for describing care provided and transferring information among physicians caring for the same patient. Writing a note, however, adds a considerable amount of time to the physician’s workflow. Using a scribe can decrease the time burden of note writing, and if scribed notes are of similar or better quality, this practice innovation can allow the physician to focus more on clinical than clerical tasks.

Over-documentation is a possible concern. While implementation of the EMR may improve certain aspects of quality of care delivered14,15 and note quality,16 concern has been raised about over-documentation related to the connection between documentation and reimbursement.17 In our study, we found that physician notes and scribed notes for both diabetes and same-day encounters often used EMR-based note templates, which can lead to over-documentation.

In general, both physician and scribed notes were rated to be of average to low quality because none of the mean scores on the 9 individual components of the PDQI-9 reached 4.0. Scribed notes were not inaccurate and had word counts similar to physician notes.

Scribing has potential drawbacks—and benefits. Drawbacks to scribing have not been well-studied. It has been suggested that using scribes to work around the EMR may actually hinder its further advancement because scribing insulates physicians from the inefficiencies of current EMRs and will not spur demands for improvements.3 Inaccurate or poor-quality notes could represent another downside to scribing, although concern about the quality of notes has not been documented. Our results suggest the opposite may be true.

Note quality has not been associated with quality of care as assessed by clinical quality scores,13 but using scribes may improve the quality of care in other ways. For example, the EMR may negatively affect patient-physician communication,18,19 and freeing the physician from documentation may improve the interaction.8,20 Incorporating scribing into practice may also improve the physician experience,9,10,21,22 a possible benefit that we did not measure.

We also did not measure the cost of using a scribe to assist in EMR documentation compared with the cost of physician time spent in performing this task. If the scribe model were associated with cost savings through increased physician productivity, as well as improved physician experience, future EMR development might best focus on planned utilization by physician-scribe teams.

Study limitations. The study was conducted in a single health system, although at 8 different practice sites. The sites all used the same EMR, but templates used for documentation could be individualized by the physician and medical assistant team, so our findings may reflect variation in template design. Our analysis did adjust for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. The selection of note types in our study may make our results less generalizable to other encounter types. Our sample was not large enough to detect variations in note quality among different providers and scribes.

The ratings on the PDQI-9 may be subjective, and the reviewers were not blinded to whether a scribe was used to write the note. The differences in PDQI-9 scores were small. Although statistically significant, they may not significantly affect clinical practice. Our care model is unique in that scribes are active members of the clinical care team; the higher quality of scribed notes we found may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the team.

Future research directions. In our study, medical assistants acting as scribes composed progress notes of similar or higher quality than physicians who wrote notes alone, although all notes were of generally average quality. As the use of scribes in medicine expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on primary care workflow, quality and cost of care delivered, and quality of physician experience.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anita D. Misra-Hebert, MD, MPH, Center for Value-Based Care Research, Medicine Institute, 9500 Euclid Avenue, G10, Cleveland, OH 44195; [email protected].

ABSTRACT

Objective Medical scribes are increasingly employed to improve physician efficiency with regard to the electronic medical record (EMR). The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes is not known. To assess the effect, we conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory progress notes written before and after 8 practice sites transitioned to the use of medical assistants as scribes.

Methods The Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9) was used to compare the quality of outpatient progress notes written by medical assistant scribes with the quality of notes written by 18 primary care physicians working without a scribe. The notes pertained to diabetes encounters and same-day appointments and were written during the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after scribes were employed (scribe period).

Results One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 from the scribe period were reviewed. Scribed notes were rated higher in overall quality than unscribed notes (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribed notes vs 28.9 for nonscribed notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible. The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same-day appointments, scribed and nonscribed notes did not differ in quality. The total word count of all scribed and nonscribed notes was similar (mean words 618, standard deviation (SD) 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

Conclusions In this retrospective review, ambulatory notes were of higher quality when medical assistants acted as scribes than when physicians wrote them alone, at least for diabetes visits. Our findings may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the clinical care team. As the use of medical scribes expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on other aspects of care quality.

Team-based models of primary care delivery may incorporate medical scribes to improve efficiency of electronic documentation.1-4 The employment of medical scribes has grown rapidly, and it is estimated that within several years there may be one scribe for every 9 physicians.3

Accurate documentation is important to providing high-quality patient care but can take a significant amount of time. Attending physicians have been estimated to spend as long as 52 minutes per day authoring notes.5 Medical scribes can help physicians improve the efficiency of electronic documentation6 and save time.2 Using scribes can also improve physician productivity7-10 and thereby potentially increase access to care. The impact of scribes on the quality of outpatient visit notes, however, is unknown.

A team-based care delivery model in our health system’s primary care clinics uses medical assistants to scribe notes during the outpatient encounter. We hypothesized that outpatient notes written by medical assistant scribes would be of similar quality to notes written by the same group of physicians without a scribe.

METHODS

Study design and sample

We conducted a retrospective review of ambulatory notes from 18 primary care physicians at 8 practice sites in our health system who had adopted a care model in which medical assistants act as scribes. Each physician works with 2 medical assistants. To train for the new model, the physician and medical assistants participated in 2 training sessions of 2 hours each and a half day of clinic observation and evaluation with a project manager.

Of the 18 primary care physicians included in this study, none had less than one year of experience in our health system. Tenure ranged from one to 24 years with a mean of 11.3 years.

For each participating provider, we requested all available outpatient progress notes with either an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code for diabetes or a designation of “same day” for the 3 to 6 months preceding the use of scribes (pre-scribe period) and the 3 to 6 months after employing scribes (scribe period). We chose diabetes encounters as examples of notes addressing chronic disease management and same-day encounters as examples of problem-focused notes because these 2 types of encounters are common in outpatient primary care practice.

Note quality was evaluated using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument 9 (PDQI-9), a validated instrument designed for this purpose, comprising 9 items rated subjectively on a 5-point Likert scale (1= not at all, 5= extremely). The items assess whether notes are up-to-date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, and internally consistent.11,12 The PDQI-9 has been applied previously in inpatient12 and outpatient settings.13

While the PDQI-9 is a validated tool, it relies on subjective ratings of note quality by the reviewer. To control for the subjective nature of the ratings, an experienced internist and an internal medicine resident coded 10 progress notes separately using the PDQI-9 and discussed the results. The process was repeated for a total of 20 notes, after which consensus was reached with >70% agreement on each attribute of the PDQI-9, suggesting that the resident’s ratings were reliable when compared with those of an experienced practicing physician.

The resident then evaluated a random sample of notes written by each physician for diabetes or same-day appointments in the pre-scribe and scribe periods. Word counts for the entire note were measured. The notes used to establish the reliability of the ratings were excluded from the analysis for this study.

Data analysis

We used linear mixed-effects models to examine note quality measures by adjusting for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. Least-squares estimates were derived; the results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

One hundred eight notes from the pre-scribe period and 109 notes from the scribe period were reviewed. Compared with notes written by a physician alone, scribed notes were rated slightly higher in overall quality (mean total PDQI-9 score 30.3 for scribe notes vs 28.9 for pre-scribe notes; P=.01) and more up-to-date, thorough, useful, and comprehensible (TABLES 1 AND 2). The differences were limited to diabetes encounters. For same day appointments, scribed notes did not differ in quality from nonscribed notes (TABLE 2). Total word count did not vary significantly between all scribe and pre-scribe notes (mean words 618, SD 273 for scribed notes vs 558 words, SD 289 for nonscribed notes; P=.12).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective review of ambulatory notes, progress notes written by medical assistant scribes were of higher quality than notes physicians wrote alone, at least for diabetes visits. Scribe and pre-scribe notes were of similar quality for problem-focused same-day visits. This is the first study of which we are aware that compares the quality of scribed notes with notes written by physicians.

Quality scribe notes can save physician time. The progress note is an important vehicle for describing care provided and transferring information among physicians caring for the same patient. Writing a note, however, adds a considerable amount of time to the physician’s workflow. Using a scribe can decrease the time burden of note writing, and if scribed notes are of similar or better quality, this practice innovation can allow the physician to focus more on clinical than clerical tasks.

Over-documentation is a possible concern. While implementation of the EMR may improve certain aspects of quality of care delivered14,15 and note quality,16 concern has been raised about over-documentation related to the connection between documentation and reimbursement.17 In our study, we found that physician notes and scribed notes for both diabetes and same-day encounters often used EMR-based note templates, which can lead to over-documentation.

In general, both physician and scribed notes were rated to be of average to low quality because none of the mean scores on the 9 individual components of the PDQI-9 reached 4.0. Scribed notes were not inaccurate and had word counts similar to physician notes.

Scribing has potential drawbacks—and benefits. Drawbacks to scribing have not been well-studied. It has been suggested that using scribes to work around the EMR may actually hinder its further advancement because scribing insulates physicians from the inefficiencies of current EMRs and will not spur demands for improvements.3 Inaccurate or poor-quality notes could represent another downside to scribing, although concern about the quality of notes has not been documented. Our results suggest the opposite may be true.

Note quality has not been associated with quality of care as assessed by clinical quality scores,13 but using scribes may improve the quality of care in other ways. For example, the EMR may negatively affect patient-physician communication,18,19 and freeing the physician from documentation may improve the interaction.8,20 Incorporating scribing into practice may also improve the physician experience,9,10,21,22 a possible benefit that we did not measure.

We also did not measure the cost of using a scribe to assist in EMR documentation compared with the cost of physician time spent in performing this task. If the scribe model were associated with cost savings through increased physician productivity, as well as improved physician experience, future EMR development might best focus on planned utilization by physician-scribe teams.

Study limitations. The study was conducted in a single health system, although at 8 different practice sites. The sites all used the same EMR, but templates used for documentation could be individualized by the physician and medical assistant team, so our findings may reflect variation in template design. Our analysis did adjust for possible correlations of notes from the same physician. The selection of note types in our study may make our results less generalizable to other encounter types. Our sample was not large enough to detect variations in note quality among different providers and scribes.

The ratings on the PDQI-9 may be subjective, and the reviewers were not blinded to whether a scribe was used to write the note. The differences in PDQI-9 scores were small. Although statistically significant, they may not significantly affect clinical practice. Our care model is unique in that scribes are active members of the clinical care team; the higher quality of scribed notes we found may not apply to professional scribes who are not part of the team.

Future research directions. In our study, medical assistants acting as scribes composed progress notes of similar or higher quality than physicians who wrote notes alone, although all notes were of generally average quality. As the use of scribes in medicine expands, additional studies should examine the impact of scribes on primary care workflow, quality and cost of care delivered, and quality of physician experience.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anita D. Misra-Hebert, MD, MPH, Center for Value-Based Care Research, Medicine Institute, 9500 Euclid Avenue, G10, Cleveland, OH 44195; [email protected].

1. Bodenheimer T, Willard-Grace R, Ghorob A. Expanding the roles of medical assistants: Who does what in primary care? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1025-1026.

2. Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, et al. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1190-1193.

3. Gellert GA, Ramirea R, Webster S. The rise of the medical scribe industry: Implications for the advancement of electronic health records. JAMA. 2015;313:1315-1316.

4. Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:371-381.

5. Hripcsak G, Vawdrey DK, Fred MR, et al. Use of electronic clinical documentation: time spent and team interactions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:112-117.

6. Silverman L. Scribes Are Back, Helping Doctors Tackle Electronic Medical Records. NPR.org. Available at: www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/21/303406306/scribes-are-back-helping-doctors-tackle-electronic-medical-records. Accessed April 23, 2014.

7. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

8. Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:399-406.

9. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

10. Allen B, Banapoor B, Weeks EC, et al. An assessment of emergency department throughput and provider satisfaction after the implementation of a scribe program. Advances in Emergency Medicine. 2014;2014:e517319.

11. Stetson PD, Morrison FP, Bakken S, et al. Preliminary development of the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:534-541.

12. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, et al. Assessing electronic note quality using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3:164-174.

13. Edwards ST, Neri PM, Volk LA, et al. Association of note quality and quality of care: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;23:406-413.

14. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1066-1069.

15. Samal L, Wright A, Healey MJ, et al. Meaningful use and quality of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:997-998.

16. Burke HB, Sessums LL, Hoang A, et al. Electronic health records improve clinical note quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:199-205.

17. Sheehy AM, Weissburg DJ, Dean SM. The role of copy-and-paste in the hospital electronic health record. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1217-1218.

18. Shachak A, Hadas-Dayagi M, Ziv A, et al. Primary care physicians’ use of an electronic medical record system: a cognitive task analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:341-348.

19. Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient-doctor communication during consultation: a narrative literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:641-649.

20. Misra-Hebert AD, Rabovsky A, Yan C, et al. A team-based model of primary care delivery and physician-patient interaction. Am J Med. 2015;128:1025-1028.

21. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

22. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.

1. Bodenheimer T, Willard-Grace R, Ghorob A. Expanding the roles of medical assistants: Who does what in primary care? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1025-1026.

2. Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, et al. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1190-1193.

3. Gellert GA, Ramirea R, Webster S. The rise of the medical scribe industry: Implications for the advancement of electronic health records. JAMA. 2015;313:1315-1316.

4. Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:371-381.

5. Hripcsak G, Vawdrey DK, Fred MR, et al. Use of electronic clinical documentation: time spent and team interactions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:112-117.

6. Silverman L. Scribes Are Back, Helping Doctors Tackle Electronic Medical Records. NPR.org. Available at: www.npr.org/blogs/health/2014/04/21/303406306/scribes-are-back-helping-doctors-tackle-electronic-medical-records. Accessed April 23, 2014.

7. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

8. Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:399-406.

9. Bastani A, Shaqiri B, Palomba K, et al. An ED scribe program is able to improve throughput time and patient satisfaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:399-402.

10. Allen B, Banapoor B, Weeks EC, et al. An assessment of emergency department throughput and provider satisfaction after the implementation of a scribe program. Advances in Emergency Medicine. 2014;2014:e517319.

11. Stetson PD, Morrison FP, Bakken S, et al. Preliminary development of the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:534-541.

12. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, et al. Assessing electronic note quality using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3:164-174.

13. Edwards ST, Neri PM, Volk LA, et al. Association of note quality and quality of care: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;23:406-413.

14. Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1066-1069.

15. Samal L, Wright A, Healey MJ, et al. Meaningful use and quality of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:997-998.

16. Burke HB, Sessums LL, Hoang A, et al. Electronic health records improve clinical note quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:199-205.

17. Sheehy AM, Weissburg DJ, Dean SM. The role of copy-and-paste in the hospital electronic health record. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1217-1218.

18. Shachak A, Hadas-Dayagi M, Ziv A, et al. Primary care physicians’ use of an electronic medical record system: a cognitive task analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:341-348.

19. Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient-doctor communication during consultation: a narrative literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:641-649.

20. Misra-Hebert AD, Rabovsky A, Yan C, et al. A team-based model of primary care delivery and physician-patient interaction. Am J Med. 2015;128:1025-1028.

21. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

22. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, et al. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;184:258-262.