User login

Babies die as congenital syphilis continues a decade-long surge across the U.S.

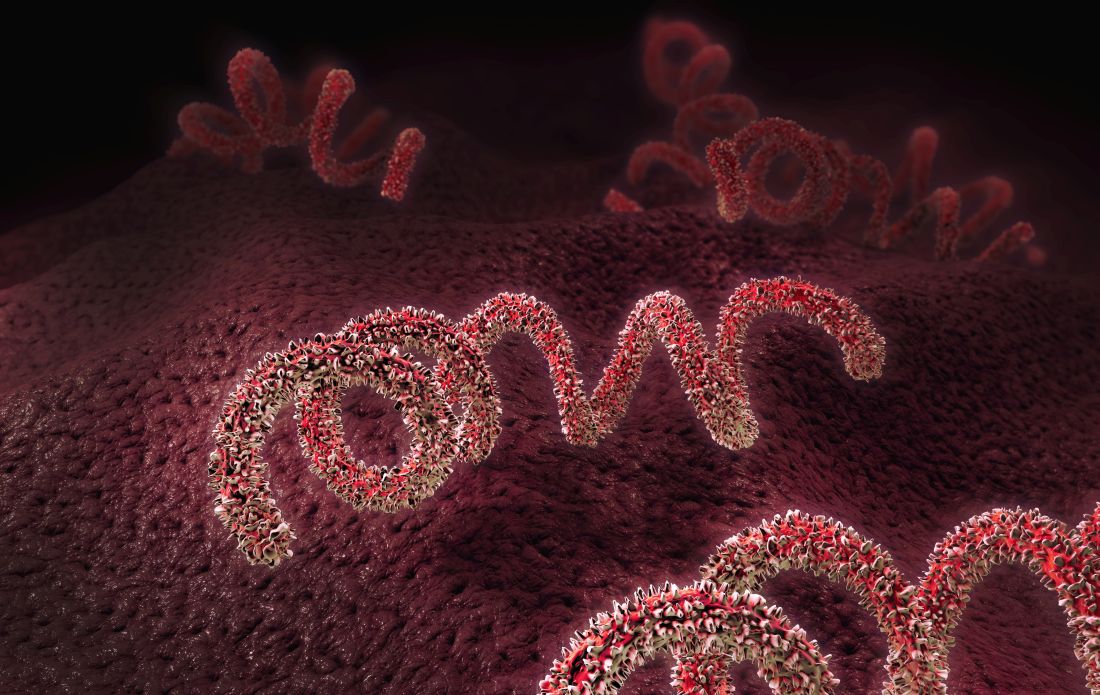

For a decade, the number of babies born with syphilis in the United States has surged, undeterred. Data released Apr. 12 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows just how dire the outbreak has become.

In 2012, 332 babies were born infected with the disease. In 2021, that number had climbed nearly sevenfold, to at least 2,268, according to preliminary estimates. And 166 of those babies died.

About 7% of babies diagnosed with syphilis in recent years have died; thousands of others born with the disease have faced problems that include brain and bone malformations, blindness, and organ damage.

For public health officials, the situation is all the more heartbreaking, considering that congenital syphilis rates reached near-historic modern lows from 2000 to 2012 amid ambitious prevention and education efforts. By 2020, following a sharp erosion in funding and attention, the nationwide case rate was more than seven times that of 2012.

“The really depressing thing about it is we had this thing virtually eradicated back in the year 2000,” said William Andrews, a public information officer for Oklahoma’s sexual health and harm reduction service. “Now it’s back with a vengeance. We are really trying to get the message out that sexual health is health. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

Even as caseloads soar, the CDC budget for STD prevention – the primary funding source for most public health departments – has been largely stagnant for two decades, its purchasing power dragged even lower by inflation.

The CDC report on STD trends provides official data on congenital syphilis cases for 2020, as well as preliminary case counts for 2021 that are expected to increase. CDC data shows that congenital syphilis rates in 2020 continued to climb in already overwhelmed states like Texas, California, and Nevada and that the disease is now present in almost every state in the nation. All but three states – Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont – reported congenital syphilis cases in 2020.

From 2011 to 2020, congenital syphilis resulted in 633 documented stillbirths and infant deaths, according to the new CDC data.

Preventing congenital syphilis – the term used when syphilis is transferred to a fetus in utero – is from a medical standpoint exceedingly simple: If a pregnant woman is diagnosed at least a month before giving birth, just a few shots of penicillin have a near-perfect cure rate for mother and baby. But funding cuts and competing priorities in the nation’s fragmented public health care system have vastly narrowed access to such services.

The reasons pregnant people with syphilis go undiagnosed or untreated vary geographically, according to data collected by states and analyzed by the CDC.

In Western states, the largest share of cases involve women who have received little to no prenatal care and aren’t tested for syphilis until they give birth. Many have substance use disorders, primarily related to methamphetamines. “They’ve felt a lot of judgment and stigma by the medical community,” said Stephanie Pierce, MD, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who runs a clinic for women with high-risk pregnancies.

In Southern states, a CDC study of 2018 data found that the largest share of congenital syphilis cases were among women who had been tested and diagnosed but hadn’t received treatment. That year, among Black moms who gave birth to a baby with syphilis, 37% had not been treated adequately even though they’d received a timely diagnosis. Among white moms, that number was 24%. Longstanding racism in medical care, poverty, transportation issues, poorly funded public health departments, and crowded clinics whose employees are too overworked to follow up with patients all contribute to the problem, according to infectious disease experts.

Doctors are also noticing a growing number of women who are treated for syphilis but reinfected during pregnancy. Amid rising cases and stagnant resources, some states have focused disease investigations on pregnant women of childbearing age; they can no longer prioritize treating sexual partners who are also infected.

Eric McGrath, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Wayne State University, Detroit, said that he’d seen several newborns in recent years whose mothers had been treated for syphilis but then were re-exposed during pregnancy by partners who hadn’t been treated.

Treating a newborn baby for syphilis isn’t trivial. Penicillin carries little risk, but delivering it to a baby often involves a lumbar puncture and other painful procedures. And treatment typically means keeping the baby in the hospital for 10 days, interrupting an important time for family bonding.

Dr. McGrath has seen a couple of babies in his career who weren’t diagnosed or treated at birth and later came to him with full-blown syphilis complications, including full-body rashes and inflamed livers. It was an awful experience he doesn’t want to repeat. The preferred course, he said, is to spare the baby the ordeal and treat parents early in the pregnancy.

But in some places, providers aren’t routinely testing for syphilis. Although most states mandate testing at some point during pregnancy, as of last year just 14 required it for everyone in the third trimester. The CDC recommends third-trimester testing in areas with high rates of syphilis, a growing share of the United States.

After Arizona declared a statewide outbreak in 2018, state health officials wanted to know whether widespread testing in the third trimester could have prevented infections. Looking at 18 months of data, analysts found that nearly three-quarters of the more than 200 pregnant women diagnosed with syphilis in 2017 and the first half of 2018 got treatment. That left 57 babies born with syphilis, nine of whom died. The analysts estimated that a third of the infections could have been prevented with testing in the third trimester.

Based on the numbers they saw in those 18 months, officials estimated that screening all women on Medicaid in the third trimester would cost the state $113,300 annually, and that treating all cases of syphilis that screening would catch could be done for just $113. Factoring in the hospitalization costs for infected infants, the officials concluded the additional testing would save the state money.

And yet prevention money has been hard to come by. Taking inflation into account, CDC prevention funding for STDs has fallen 41% since 2003, according to an analysis by the National Coalition of STD Directors. That’s even as cases have risen, leaving public health departments saddled with more work and far less money.

Janine Waters, STD program manager for the state of New Mexico, has watched the unraveling. When Ms. Waters started her career more than 20 years ago, she and her colleagues followed up on every case of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis reported, not only making sure that people got treatment but also getting in touch with their sexual partners, with the aim of stopping the spread of infection. In a 2019 interview with Kaiser Health News, she said her team was struggling to keep up with syphilis alone, even as they registered with dread congenital syphilis cases surging in neighboring Texas and Arizona.

By 2020, New Mexico had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic drained the remaining resources. Half of health departments across the country discontinued STD fieldwork altogether, diverting their resources to COVID. In California, which for years has struggled with high rates of congenital syphilis, three-quarters of local health departments dispatched more than half of their STD staffers to work on COVID.

As the pandemic ebbs – at least in the short term – many public health departments are turning their attention back to syphilis and other diseases. And they are doing it with reinforcements. Although the Biden administration’s proposed STD prevention budget for 2023 remains flat, the American Rescue Plan Act included $200 million to help health departments boost contact tracing and surveillance for covid and other infectious diseases. Many departments are funneling that money toward STDs.

The money is an infusion that state health officials say will make a difference. But when taking inflation into account, it essentially brings STD prevention funding back to what it was in 2003, said Stephanie Arnold Pang of the National Coalition of STD Directors. And the American Rescue Plan money doesn’t cover some aspects of STD prevention, including clinical services.

The coalition wants to revive dedicated STD clinics, where people can drop in for testing and treatment at little to no cost. Advocates say that would fill a void that has plagued treatment efforts since public clinics closed en masse in the wake of the 2008 recession.

Texas, battling its own pervasive outbreak, will use its share of American Rescue Plan money to fill 94 new positions focused on various aspects of STD prevention. Those hires will bolster a range of measures the state put in place before the pandemic, including an updated data system to track infections, review boards in major cities that examine what went wrong for every case of congenital syphilis, and a requirement that providers test for syphilis during the third trimester of pregnancy. The suite of interventions seems to be working, but it could be a while before cases go down, said Amy Carter, the state’s congenital syphilis coordinator.

“The growth didn’t happen overnight,” Ms. Carter said. “So our prevention efforts aren’t going to have a direct impact overnight either.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation

For a decade, the number of babies born with syphilis in the United States has surged, undeterred. Data released Apr. 12 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows just how dire the outbreak has become.

In 2012, 332 babies were born infected with the disease. In 2021, that number had climbed nearly sevenfold, to at least 2,268, according to preliminary estimates. And 166 of those babies died.

About 7% of babies diagnosed with syphilis in recent years have died; thousands of others born with the disease have faced problems that include brain and bone malformations, blindness, and organ damage.

For public health officials, the situation is all the more heartbreaking, considering that congenital syphilis rates reached near-historic modern lows from 2000 to 2012 amid ambitious prevention and education efforts. By 2020, following a sharp erosion in funding and attention, the nationwide case rate was more than seven times that of 2012.

“The really depressing thing about it is we had this thing virtually eradicated back in the year 2000,” said William Andrews, a public information officer for Oklahoma’s sexual health and harm reduction service. “Now it’s back with a vengeance. We are really trying to get the message out that sexual health is health. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

Even as caseloads soar, the CDC budget for STD prevention – the primary funding source for most public health departments – has been largely stagnant for two decades, its purchasing power dragged even lower by inflation.

The CDC report on STD trends provides official data on congenital syphilis cases for 2020, as well as preliminary case counts for 2021 that are expected to increase. CDC data shows that congenital syphilis rates in 2020 continued to climb in already overwhelmed states like Texas, California, and Nevada and that the disease is now present in almost every state in the nation. All but three states – Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont – reported congenital syphilis cases in 2020.

From 2011 to 2020, congenital syphilis resulted in 633 documented stillbirths and infant deaths, according to the new CDC data.

Preventing congenital syphilis – the term used when syphilis is transferred to a fetus in utero – is from a medical standpoint exceedingly simple: If a pregnant woman is diagnosed at least a month before giving birth, just a few shots of penicillin have a near-perfect cure rate for mother and baby. But funding cuts and competing priorities in the nation’s fragmented public health care system have vastly narrowed access to such services.

The reasons pregnant people with syphilis go undiagnosed or untreated vary geographically, according to data collected by states and analyzed by the CDC.

In Western states, the largest share of cases involve women who have received little to no prenatal care and aren’t tested for syphilis until they give birth. Many have substance use disorders, primarily related to methamphetamines. “They’ve felt a lot of judgment and stigma by the medical community,” said Stephanie Pierce, MD, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who runs a clinic for women with high-risk pregnancies.

In Southern states, a CDC study of 2018 data found that the largest share of congenital syphilis cases were among women who had been tested and diagnosed but hadn’t received treatment. That year, among Black moms who gave birth to a baby with syphilis, 37% had not been treated adequately even though they’d received a timely diagnosis. Among white moms, that number was 24%. Longstanding racism in medical care, poverty, transportation issues, poorly funded public health departments, and crowded clinics whose employees are too overworked to follow up with patients all contribute to the problem, according to infectious disease experts.

Doctors are also noticing a growing number of women who are treated for syphilis but reinfected during pregnancy. Amid rising cases and stagnant resources, some states have focused disease investigations on pregnant women of childbearing age; they can no longer prioritize treating sexual partners who are also infected.

Eric McGrath, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Wayne State University, Detroit, said that he’d seen several newborns in recent years whose mothers had been treated for syphilis but then were re-exposed during pregnancy by partners who hadn’t been treated.

Treating a newborn baby for syphilis isn’t trivial. Penicillin carries little risk, but delivering it to a baby often involves a lumbar puncture and other painful procedures. And treatment typically means keeping the baby in the hospital for 10 days, interrupting an important time for family bonding.

Dr. McGrath has seen a couple of babies in his career who weren’t diagnosed or treated at birth and later came to him with full-blown syphilis complications, including full-body rashes and inflamed livers. It was an awful experience he doesn’t want to repeat. The preferred course, he said, is to spare the baby the ordeal and treat parents early in the pregnancy.

But in some places, providers aren’t routinely testing for syphilis. Although most states mandate testing at some point during pregnancy, as of last year just 14 required it for everyone in the third trimester. The CDC recommends third-trimester testing in areas with high rates of syphilis, a growing share of the United States.

After Arizona declared a statewide outbreak in 2018, state health officials wanted to know whether widespread testing in the third trimester could have prevented infections. Looking at 18 months of data, analysts found that nearly three-quarters of the more than 200 pregnant women diagnosed with syphilis in 2017 and the first half of 2018 got treatment. That left 57 babies born with syphilis, nine of whom died. The analysts estimated that a third of the infections could have been prevented with testing in the third trimester.

Based on the numbers they saw in those 18 months, officials estimated that screening all women on Medicaid in the third trimester would cost the state $113,300 annually, and that treating all cases of syphilis that screening would catch could be done for just $113. Factoring in the hospitalization costs for infected infants, the officials concluded the additional testing would save the state money.

And yet prevention money has been hard to come by. Taking inflation into account, CDC prevention funding for STDs has fallen 41% since 2003, according to an analysis by the National Coalition of STD Directors. That’s even as cases have risen, leaving public health departments saddled with more work and far less money.

Janine Waters, STD program manager for the state of New Mexico, has watched the unraveling. When Ms. Waters started her career more than 20 years ago, she and her colleagues followed up on every case of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis reported, not only making sure that people got treatment but also getting in touch with their sexual partners, with the aim of stopping the spread of infection. In a 2019 interview with Kaiser Health News, she said her team was struggling to keep up with syphilis alone, even as they registered with dread congenital syphilis cases surging in neighboring Texas and Arizona.

By 2020, New Mexico had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic drained the remaining resources. Half of health departments across the country discontinued STD fieldwork altogether, diverting their resources to COVID. In California, which for years has struggled with high rates of congenital syphilis, three-quarters of local health departments dispatched more than half of their STD staffers to work on COVID.

As the pandemic ebbs – at least in the short term – many public health departments are turning their attention back to syphilis and other diseases. And they are doing it with reinforcements. Although the Biden administration’s proposed STD prevention budget for 2023 remains flat, the American Rescue Plan Act included $200 million to help health departments boost contact tracing and surveillance for covid and other infectious diseases. Many departments are funneling that money toward STDs.

The money is an infusion that state health officials say will make a difference. But when taking inflation into account, it essentially brings STD prevention funding back to what it was in 2003, said Stephanie Arnold Pang of the National Coalition of STD Directors. And the American Rescue Plan money doesn’t cover some aspects of STD prevention, including clinical services.

The coalition wants to revive dedicated STD clinics, where people can drop in for testing and treatment at little to no cost. Advocates say that would fill a void that has plagued treatment efforts since public clinics closed en masse in the wake of the 2008 recession.

Texas, battling its own pervasive outbreak, will use its share of American Rescue Plan money to fill 94 new positions focused on various aspects of STD prevention. Those hires will bolster a range of measures the state put in place before the pandemic, including an updated data system to track infections, review boards in major cities that examine what went wrong for every case of congenital syphilis, and a requirement that providers test for syphilis during the third trimester of pregnancy. The suite of interventions seems to be working, but it could be a while before cases go down, said Amy Carter, the state’s congenital syphilis coordinator.

“The growth didn’t happen overnight,” Ms. Carter said. “So our prevention efforts aren’t going to have a direct impact overnight either.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation

For a decade, the number of babies born with syphilis in the United States has surged, undeterred. Data released Apr. 12 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows just how dire the outbreak has become.

In 2012, 332 babies were born infected with the disease. In 2021, that number had climbed nearly sevenfold, to at least 2,268, according to preliminary estimates. And 166 of those babies died.

About 7% of babies diagnosed with syphilis in recent years have died; thousands of others born with the disease have faced problems that include brain and bone malformations, blindness, and organ damage.

For public health officials, the situation is all the more heartbreaking, considering that congenital syphilis rates reached near-historic modern lows from 2000 to 2012 amid ambitious prevention and education efforts. By 2020, following a sharp erosion in funding and attention, the nationwide case rate was more than seven times that of 2012.

“The really depressing thing about it is we had this thing virtually eradicated back in the year 2000,” said William Andrews, a public information officer for Oklahoma’s sexual health and harm reduction service. “Now it’s back with a vengeance. We are really trying to get the message out that sexual health is health. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

Even as caseloads soar, the CDC budget for STD prevention – the primary funding source for most public health departments – has been largely stagnant for two decades, its purchasing power dragged even lower by inflation.

The CDC report on STD trends provides official data on congenital syphilis cases for 2020, as well as preliminary case counts for 2021 that are expected to increase. CDC data shows that congenital syphilis rates in 2020 continued to climb in already overwhelmed states like Texas, California, and Nevada and that the disease is now present in almost every state in the nation. All but three states – Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont – reported congenital syphilis cases in 2020.

From 2011 to 2020, congenital syphilis resulted in 633 documented stillbirths and infant deaths, according to the new CDC data.

Preventing congenital syphilis – the term used when syphilis is transferred to a fetus in utero – is from a medical standpoint exceedingly simple: If a pregnant woman is diagnosed at least a month before giving birth, just a few shots of penicillin have a near-perfect cure rate for mother and baby. But funding cuts and competing priorities in the nation’s fragmented public health care system have vastly narrowed access to such services.

The reasons pregnant people with syphilis go undiagnosed or untreated vary geographically, according to data collected by states and analyzed by the CDC.

In Western states, the largest share of cases involve women who have received little to no prenatal care and aren’t tested for syphilis until they give birth. Many have substance use disorders, primarily related to methamphetamines. “They’ve felt a lot of judgment and stigma by the medical community,” said Stephanie Pierce, MD, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, who runs a clinic for women with high-risk pregnancies.

In Southern states, a CDC study of 2018 data found that the largest share of congenital syphilis cases were among women who had been tested and diagnosed but hadn’t received treatment. That year, among Black moms who gave birth to a baby with syphilis, 37% had not been treated adequately even though they’d received a timely diagnosis. Among white moms, that number was 24%. Longstanding racism in medical care, poverty, transportation issues, poorly funded public health departments, and crowded clinics whose employees are too overworked to follow up with patients all contribute to the problem, according to infectious disease experts.

Doctors are also noticing a growing number of women who are treated for syphilis but reinfected during pregnancy. Amid rising cases and stagnant resources, some states have focused disease investigations on pregnant women of childbearing age; they can no longer prioritize treating sexual partners who are also infected.

Eric McGrath, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Wayne State University, Detroit, said that he’d seen several newborns in recent years whose mothers had been treated for syphilis but then were re-exposed during pregnancy by partners who hadn’t been treated.

Treating a newborn baby for syphilis isn’t trivial. Penicillin carries little risk, but delivering it to a baby often involves a lumbar puncture and other painful procedures. And treatment typically means keeping the baby in the hospital for 10 days, interrupting an important time for family bonding.

Dr. McGrath has seen a couple of babies in his career who weren’t diagnosed or treated at birth and later came to him with full-blown syphilis complications, including full-body rashes and inflamed livers. It was an awful experience he doesn’t want to repeat. The preferred course, he said, is to spare the baby the ordeal and treat parents early in the pregnancy.

But in some places, providers aren’t routinely testing for syphilis. Although most states mandate testing at some point during pregnancy, as of last year just 14 required it for everyone in the third trimester. The CDC recommends third-trimester testing in areas with high rates of syphilis, a growing share of the United States.

After Arizona declared a statewide outbreak in 2018, state health officials wanted to know whether widespread testing in the third trimester could have prevented infections. Looking at 18 months of data, analysts found that nearly three-quarters of the more than 200 pregnant women diagnosed with syphilis in 2017 and the first half of 2018 got treatment. That left 57 babies born with syphilis, nine of whom died. The analysts estimated that a third of the infections could have been prevented with testing in the third trimester.

Based on the numbers they saw in those 18 months, officials estimated that screening all women on Medicaid in the third trimester would cost the state $113,300 annually, and that treating all cases of syphilis that screening would catch could be done for just $113. Factoring in the hospitalization costs for infected infants, the officials concluded the additional testing would save the state money.

And yet prevention money has been hard to come by. Taking inflation into account, CDC prevention funding for STDs has fallen 41% since 2003, according to an analysis by the National Coalition of STD Directors. That’s even as cases have risen, leaving public health departments saddled with more work and far less money.

Janine Waters, STD program manager for the state of New Mexico, has watched the unraveling. When Ms. Waters started her career more than 20 years ago, she and her colleagues followed up on every case of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis reported, not only making sure that people got treatment but also getting in touch with their sexual partners, with the aim of stopping the spread of infection. In a 2019 interview with Kaiser Health News, she said her team was struggling to keep up with syphilis alone, even as they registered with dread congenital syphilis cases surging in neighboring Texas and Arizona.

By 2020, New Mexico had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic drained the remaining resources. Half of health departments across the country discontinued STD fieldwork altogether, diverting their resources to COVID. In California, which for years has struggled with high rates of congenital syphilis, three-quarters of local health departments dispatched more than half of their STD staffers to work on COVID.

As the pandemic ebbs – at least in the short term – many public health departments are turning their attention back to syphilis and other diseases. And they are doing it with reinforcements. Although the Biden administration’s proposed STD prevention budget for 2023 remains flat, the American Rescue Plan Act included $200 million to help health departments boost contact tracing and surveillance for covid and other infectious diseases. Many departments are funneling that money toward STDs.

The money is an infusion that state health officials say will make a difference. But when taking inflation into account, it essentially brings STD prevention funding back to what it was in 2003, said Stephanie Arnold Pang of the National Coalition of STD Directors. And the American Rescue Plan money doesn’t cover some aspects of STD prevention, including clinical services.

The coalition wants to revive dedicated STD clinics, where people can drop in for testing and treatment at little to no cost. Advocates say that would fill a void that has plagued treatment efforts since public clinics closed en masse in the wake of the 2008 recession.

Texas, battling its own pervasive outbreak, will use its share of American Rescue Plan money to fill 94 new positions focused on various aspects of STD prevention. Those hires will bolster a range of measures the state put in place before the pandemic, including an updated data system to track infections, review boards in major cities that examine what went wrong for every case of congenital syphilis, and a requirement that providers test for syphilis during the third trimester of pregnancy. The suite of interventions seems to be working, but it could be a while before cases go down, said Amy Carter, the state’s congenital syphilis coordinator.

“The growth didn’t happen overnight,” Ms. Carter said. “So our prevention efforts aren’t going to have a direct impact overnight either.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation

Racism a strong factor in Black women’s high rate of premature births, study finds

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Can the U.S. keep COVID-19 variants in check? Here’s what it takes

The COVID-19 variants that have emerged in the United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa and now Southern California are eliciting two notably distinct responses from U.S. public health officials.

First, broad concern. A variant that wreaked havoc in the United Kingdom, leading to a spike in cases and hospitalizations, is surfacing in a growing number of places in the United States. During the week of Jan. 24, another worrisome variant seen in Brazil surfaced in Minnesota. If these or other strains significantly change the way the virus transmits and attacks the body, as scientists fear they might, they could cause yet another prolonged surge in illness and death in the U.S., even as cases have begun to plateau and vaccines are rolling out.

On the other hand, variants aren’t novel or even uncommon in viral illnesses. The viruses that trigger common colds and flus regularly evolve. Even if a mutated strain of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, makes it more contagious or makes people sicker,

The problem is that the U.S. has struggled with every step of its public health response in its first year of battle against COVID-19. And that raises the question of whether the nation will devote the attention and resources needed to outflank the virus as it evolves.

Researchers are quick to stress that a coronavirus mutation in itself is no cause for alarm. In the course of making millions and billions of copies as part of the infection process, small changes to a virus’s genome happen all the time as a function of evolutionary biology.

“The word ‘variant’ and the word ‘mutation’ have these scary connotations, and they aren’t necessarily scary,” said Kelly Wroblewski, director of infectious disease programs for the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

When a mutation rings public health alarms, it’s typically because it has combined with other mutations and, collectively, changed how the virus behaves. At that point, it may be named a variant. A variant can make a virus spread faster, or more easily jump between species. It can make a virus more successful at making people sicker, or change how our immune systems respond.

SARS-CoV-2 has been mutating for as long as we’ve known about it; mutations were identified by scientists throughout 2020. Though relevant scientifically – mutations can actually be helpful, acting like a fingerprint that allows scientists to track a virus’s spread – the identified strains mostly carried little concern for public health.

Then came the end of the year, when several variants began drawing scrutiny. One of the most concerning, first detected in the United Kingdom, appears to make the virus more transmissible. Emerging evidence suggests it also could be deadlier, though scientists are still debating that.

We know more about the U.K. variant than others not because it’s necessarily worse, but because the British have one of the best virus surveillance programs in the world, said William Hanage, PhD, an epidemiologist and a professor at Harvard University.

By contrast, the U.S. has one of the weakest genomic surveillance programs of any rich country, Dr. Hanage said. “As it is, people like me cobble together partnerships with places and try and beg them” for samples, he said on a recent call with reporters.

Other variant strains were identified in South Africa and Brazil, and they share some mutations with the U.K. variant. That those changes evolved independently in several parts of the world suggests they might present an evolutionary advantage for the virus. Yet another strain was recently identified in Southern California and flagged due to its increasing presence in hard-hit cities like Los Angeles.

The Southern California strain was detected because a team of researchers at Cedars-Sinai, a hospital and research center in Los Angeles, has unfettered access to patient samples. They were able to see that the strain made up a growing share of cases at the hospital in recent weeks, as well as among the limited number of other samples haphazardly collected at a network of labs in the region.

Not only does the U.S. do less genomic sequencing than most wealthy countries, but it also does its surveillance by happenstance. That means it takes longer to detect new strains and draw conclusions about them. It’s not yet clear, for example, whether that Southern California strain was truly worthy of a press release.

Vast swaths of America’s privatized and decentralized system of health care aren’t set up to send samples to public health or academic labs. “I’m more concerned about the systems to detect variants than I am these particular variants,” said Mark Pandori, PhD, director of Nevada’s public health laboratory and associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno School of Medicine.

Limited genomic surveillance of viruses is yet another side effect of a fragmented and underfunded public health system that’s struggled to test, track contacts and get COVID-19 under control throughout the pandemic, Ms. Wroblewski said.

The nation’s public health infrastructure, generally funded on a disease-by-disease basis, has decent systems set up to sequence flu, foodborne illnesses and tuberculosis, but there has been no national strategy on COVID-19. “To look for variants, it needs to be a national picture if it’s going to be done well,” Ms. Wroblewski said.

The Biden administration has outlined a strategy for a national response to COVID-19, which includes expanded surveillance for variants.

So far, vaccines for COVID-19 appear to protect against the known variants. Moderna has said its vaccine is effective against the U.K. and South African strains, though it yields fewer antibodies in the face of the latter. The company is working to develop a revised dose of the vaccine that could be added to the current two-shot regimen as a precaution.

But a lot of damage can be done in the time it will take to roll out the current vaccine, let alone an update.

Even with limited sampling, the U.K. variant has been detected in more than two dozen U.S. states, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned it could be the predominant strain in the U.S. by March. When it took off in the United Kingdom at the end of last year, it caused a swell in cases, overwhelmed hospitals, and led to a holiday lockdown. Whether the U.S. faces the same fate could depend on which strains it is competing against, and how the public behaves in the weeks ahead.

Already risky interactions among people could, on average, get a little riskier. Many researchers are calling for better masks and better indoor ventilation. But any updates on recommendations likely would play at the margins. Even if variants spread more easily, the same recommendations public health experts have been espousing for months – masking, physical distancing, and limiting time indoors with others – will be the best way to ward them off, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, a physician and professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s very unsexy what the solutions are,” Dr. Bibbins-Domingo said. “But we need everyone to do them.”

That doesn’t make the task simple. Masking remains controversial in many states, and the public’s patience for maintaining physical distance has worn thin.

Adding to the concerns: Though case numbers stabilized in many parts of the U.S. in January, they have stabilized at rates many times what they were during previous periods in the pandemic or in other parts of the world. Having all that virus in so many bodies creates more opportunities for new mutations and new variants to emerge.

“If we keep letting this thing sneak around, it’s going to get around all the measures we take against it, and that’s the worst possible thing,” said Nevada’s Dr. Pandori.

Compared with less virulent strains, a more contagious variant likely will require that more people be vaccinated before a community can see the benefits of widespread immunity. It’s a bleak outlook for a nation already falling behind in the race to vaccinate enough people to bring the pandemic under control.

“When your best solution is to ask people to do the things that they don’t like to do anyway, that’s very scary,” said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The COVID-19 variants that have emerged in the United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa and now Southern California are eliciting two notably distinct responses from U.S. public health officials.

First, broad concern. A variant that wreaked havoc in the United Kingdom, leading to a spike in cases and hospitalizations, is surfacing in a growing number of places in the United States. During the week of Jan. 24, another worrisome variant seen in Brazil surfaced in Minnesota. If these or other strains significantly change the way the virus transmits and attacks the body, as scientists fear they might, they could cause yet another prolonged surge in illness and death in the U.S., even as cases have begun to plateau and vaccines are rolling out.

On the other hand, variants aren’t novel or even uncommon in viral illnesses. The viruses that trigger common colds and flus regularly evolve. Even if a mutated strain of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, makes it more contagious or makes people sicker,

The problem is that the U.S. has struggled with every step of its public health response in its first year of battle against COVID-19. And that raises the question of whether the nation will devote the attention and resources needed to outflank the virus as it evolves.

Researchers are quick to stress that a coronavirus mutation in itself is no cause for alarm. In the course of making millions and billions of copies as part of the infection process, small changes to a virus’s genome happen all the time as a function of evolutionary biology.

“The word ‘variant’ and the word ‘mutation’ have these scary connotations, and they aren’t necessarily scary,” said Kelly Wroblewski, director of infectious disease programs for the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

When a mutation rings public health alarms, it’s typically because it has combined with other mutations and, collectively, changed how the virus behaves. At that point, it may be named a variant. A variant can make a virus spread faster, or more easily jump between species. It can make a virus more successful at making people sicker, or change how our immune systems respond.

SARS-CoV-2 has been mutating for as long as we’ve known about it; mutations were identified by scientists throughout 2020. Though relevant scientifically – mutations can actually be helpful, acting like a fingerprint that allows scientists to track a virus’s spread – the identified strains mostly carried little concern for public health.

Then came the end of the year, when several variants began drawing scrutiny. One of the most concerning, first detected in the United Kingdom, appears to make the virus more transmissible. Emerging evidence suggests it also could be deadlier, though scientists are still debating that.

We know more about the U.K. variant than others not because it’s necessarily worse, but because the British have one of the best virus surveillance programs in the world, said William Hanage, PhD, an epidemiologist and a professor at Harvard University.

By contrast, the U.S. has one of the weakest genomic surveillance programs of any rich country, Dr. Hanage said. “As it is, people like me cobble together partnerships with places and try and beg them” for samples, he said on a recent call with reporters.

Other variant strains were identified in South Africa and Brazil, and they share some mutations with the U.K. variant. That those changes evolved independently in several parts of the world suggests they might present an evolutionary advantage for the virus. Yet another strain was recently identified in Southern California and flagged due to its increasing presence in hard-hit cities like Los Angeles.

The Southern California strain was detected because a team of researchers at Cedars-Sinai, a hospital and research center in Los Angeles, has unfettered access to patient samples. They were able to see that the strain made up a growing share of cases at the hospital in recent weeks, as well as among the limited number of other samples haphazardly collected at a network of labs in the region.

Not only does the U.S. do less genomic sequencing than most wealthy countries, but it also does its surveillance by happenstance. That means it takes longer to detect new strains and draw conclusions about them. It’s not yet clear, for example, whether that Southern California strain was truly worthy of a press release.

Vast swaths of America’s privatized and decentralized system of health care aren’t set up to send samples to public health or academic labs. “I’m more concerned about the systems to detect variants than I am these particular variants,” said Mark Pandori, PhD, director of Nevada’s public health laboratory and associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno School of Medicine.

Limited genomic surveillance of viruses is yet another side effect of a fragmented and underfunded public health system that’s struggled to test, track contacts and get COVID-19 under control throughout the pandemic, Ms. Wroblewski said.

The nation’s public health infrastructure, generally funded on a disease-by-disease basis, has decent systems set up to sequence flu, foodborne illnesses and tuberculosis, but there has been no national strategy on COVID-19. “To look for variants, it needs to be a national picture if it’s going to be done well,” Ms. Wroblewski said.

The Biden administration has outlined a strategy for a national response to COVID-19, which includes expanded surveillance for variants.

So far, vaccines for COVID-19 appear to protect against the known variants. Moderna has said its vaccine is effective against the U.K. and South African strains, though it yields fewer antibodies in the face of the latter. The company is working to develop a revised dose of the vaccine that could be added to the current two-shot regimen as a precaution.

But a lot of damage can be done in the time it will take to roll out the current vaccine, let alone an update.

Even with limited sampling, the U.K. variant has been detected in more than two dozen U.S. states, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned it could be the predominant strain in the U.S. by March. When it took off in the United Kingdom at the end of last year, it caused a swell in cases, overwhelmed hospitals, and led to a holiday lockdown. Whether the U.S. faces the same fate could depend on which strains it is competing against, and how the public behaves in the weeks ahead.

Already risky interactions among people could, on average, get a little riskier. Many researchers are calling for better masks and better indoor ventilation. But any updates on recommendations likely would play at the margins. Even if variants spread more easily, the same recommendations public health experts have been espousing for months – masking, physical distancing, and limiting time indoors with others – will be the best way to ward them off, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, a physician and professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s very unsexy what the solutions are,” Dr. Bibbins-Domingo said. “But we need everyone to do them.”

That doesn’t make the task simple. Masking remains controversial in many states, and the public’s patience for maintaining physical distance has worn thin.

Adding to the concerns: Though case numbers stabilized in many parts of the U.S. in January, they have stabilized at rates many times what they were during previous periods in the pandemic or in other parts of the world. Having all that virus in so many bodies creates more opportunities for new mutations and new variants to emerge.

“If we keep letting this thing sneak around, it’s going to get around all the measures we take against it, and that’s the worst possible thing,” said Nevada’s Dr. Pandori.

Compared with less virulent strains, a more contagious variant likely will require that more people be vaccinated before a community can see the benefits of widespread immunity. It’s a bleak outlook for a nation already falling behind in the race to vaccinate enough people to bring the pandemic under control.

“When your best solution is to ask people to do the things that they don’t like to do anyway, that’s very scary,” said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The COVID-19 variants that have emerged in the United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa and now Southern California are eliciting two notably distinct responses from U.S. public health officials.

First, broad concern. A variant that wreaked havoc in the United Kingdom, leading to a spike in cases and hospitalizations, is surfacing in a growing number of places in the United States. During the week of Jan. 24, another worrisome variant seen in Brazil surfaced in Minnesota. If these or other strains significantly change the way the virus transmits and attacks the body, as scientists fear they might, they could cause yet another prolonged surge in illness and death in the U.S., even as cases have begun to plateau and vaccines are rolling out.

On the other hand, variants aren’t novel or even uncommon in viral illnesses. The viruses that trigger common colds and flus regularly evolve. Even if a mutated strain of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, makes it more contagious or makes people sicker,

The problem is that the U.S. has struggled with every step of its public health response in its first year of battle against COVID-19. And that raises the question of whether the nation will devote the attention and resources needed to outflank the virus as it evolves.

Researchers are quick to stress that a coronavirus mutation in itself is no cause for alarm. In the course of making millions and billions of copies as part of the infection process, small changes to a virus’s genome happen all the time as a function of evolutionary biology.

“The word ‘variant’ and the word ‘mutation’ have these scary connotations, and they aren’t necessarily scary,” said Kelly Wroblewski, director of infectious disease programs for the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

When a mutation rings public health alarms, it’s typically because it has combined with other mutations and, collectively, changed how the virus behaves. At that point, it may be named a variant. A variant can make a virus spread faster, or more easily jump between species. It can make a virus more successful at making people sicker, or change how our immune systems respond.

SARS-CoV-2 has been mutating for as long as we’ve known about it; mutations were identified by scientists throughout 2020. Though relevant scientifically – mutations can actually be helpful, acting like a fingerprint that allows scientists to track a virus’s spread – the identified strains mostly carried little concern for public health.

Then came the end of the year, when several variants began drawing scrutiny. One of the most concerning, first detected in the United Kingdom, appears to make the virus more transmissible. Emerging evidence suggests it also could be deadlier, though scientists are still debating that.

We know more about the U.K. variant than others not because it’s necessarily worse, but because the British have one of the best virus surveillance programs in the world, said William Hanage, PhD, an epidemiologist and a professor at Harvard University.

By contrast, the U.S. has one of the weakest genomic surveillance programs of any rich country, Dr. Hanage said. “As it is, people like me cobble together partnerships with places and try and beg them” for samples, he said on a recent call with reporters.

Other variant strains were identified in South Africa and Brazil, and they share some mutations with the U.K. variant. That those changes evolved independently in several parts of the world suggests they might present an evolutionary advantage for the virus. Yet another strain was recently identified in Southern California and flagged due to its increasing presence in hard-hit cities like Los Angeles.

The Southern California strain was detected because a team of researchers at Cedars-Sinai, a hospital and research center in Los Angeles, has unfettered access to patient samples. They were able to see that the strain made up a growing share of cases at the hospital in recent weeks, as well as among the limited number of other samples haphazardly collected at a network of labs in the region.

Not only does the U.S. do less genomic sequencing than most wealthy countries, but it also does its surveillance by happenstance. That means it takes longer to detect new strains and draw conclusions about them. It’s not yet clear, for example, whether that Southern California strain was truly worthy of a press release.

Vast swaths of America’s privatized and decentralized system of health care aren’t set up to send samples to public health or academic labs. “I’m more concerned about the systems to detect variants than I am these particular variants,” said Mark Pandori, PhD, director of Nevada’s public health laboratory and associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno School of Medicine.

Limited genomic surveillance of viruses is yet another side effect of a fragmented and underfunded public health system that’s struggled to test, track contacts and get COVID-19 under control throughout the pandemic, Ms. Wroblewski said.

The nation’s public health infrastructure, generally funded on a disease-by-disease basis, has decent systems set up to sequence flu, foodborne illnesses and tuberculosis, but there has been no national strategy on COVID-19. “To look for variants, it needs to be a national picture if it’s going to be done well,” Ms. Wroblewski said.

The Biden administration has outlined a strategy for a national response to COVID-19, which includes expanded surveillance for variants.

So far, vaccines for COVID-19 appear to protect against the known variants. Moderna has said its vaccine is effective against the U.K. and South African strains, though it yields fewer antibodies in the face of the latter. The company is working to develop a revised dose of the vaccine that could be added to the current two-shot regimen as a precaution.

But a lot of damage can be done in the time it will take to roll out the current vaccine, let alone an update.

Even with limited sampling, the U.K. variant has been detected in more than two dozen U.S. states, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned it could be the predominant strain in the U.S. by March. When it took off in the United Kingdom at the end of last year, it caused a swell in cases, overwhelmed hospitals, and led to a holiday lockdown. Whether the U.S. faces the same fate could depend on which strains it is competing against, and how the public behaves in the weeks ahead.