User login

A Quality Improvement Initiative to Improve Emergency Department Care for Pediatric Patients with Sickle Cell Disease

From the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, CA.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine whether a quality improvement (QI) initiative would result in more timely assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell–related pain for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) treated in the emergency department (ED).

- Methods: We created and implemented a protocol for SCD pain management in the ED with the goals of improving (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose; (2) percentage of patients that received their first analgesic dose within 30 minutes of triage, and (3) percentage of patients who had pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage and who were re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first analgesic dose.

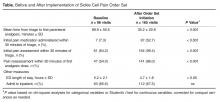

- Results: Significant improvements were achieved between baseline (55 patient visits) and post order set implementation (165 visits) in time from triage to administration of first analgesic (decreased from 89.9 ± 50.5 to 35.2 ± 22.8 minutes, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits receiving pain medications within 30 minutes of triage (from 7% to 53%, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits assessed within 30 minutes of triage (from 64% to 99.4%, P < 0.001); and percentage of patient visits re-assessed within 30 minutes of initial analgesic (from 54% to 86%, P < 0.001).

- Conclusions: Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with pain. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we address our objective of decreasing the quality gap in SCD medical care.

Pain is the leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) [1]. In the United States, 78% of the nearly 200,000 annual ED visits for SCD are for a complaint of pain [1]. Guidelines for the management of sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain episodes (VOE) suggest prompt initiation of parenteral opioids, use of effective opioid doses, and repeat opioid doses at frequent intervals [2–4]. Adherence to guidelines is poor. Both pediatric and adult patients with SCD experience delays in the initiation of analgesics and are routinely undertreated with respect to opioid dosing [5–8]. Even after controlling for race, the delays in time to analgesic administration experienced by patients with SCD exceed the delays encountered by patients who present to the ED with other types of pain [5,9]. These disparities warrant efforts designed to improve the delivery of quality care to patients with SCD.

Barriers to rapid and appropriate care of VOE in the ED are multifactorial and include systems-based limitations, such as acuity of the ED census, staffing limitations (eg, nurse-to-patient ratios), and facility limitations (eg, room availability) [6]. Provider-based limitations may include lack of awareness of available guidelines [10]. Biases and misunderstandings amongst providers about sickle cell pain and adequate medication dosing may also play a role [11–13]. These provider biases often lead to undertreatment of the pain, which in turn can lead to pseudoaddiction (drug-seeking behavior due to inadequate treatment) and a cycle of increased ED and inpatient utilization [14,15].

Patient-specific barriers to effective ED management of pain are equally complex. Previous negative experiences in the ED can lead patients and families to delay seeking care or avoid the ED altogether despite severe VOE pain [16]. Patients report frustration with the lack of consideration that they receive for their reports of pain, perceived insensitivity of hospital staff, inadequate analgesic administration, staff preoccupation with concerns of drug addiction, and an overall lack of respect and trust [17–19]. Patients also perceive a lack of knowledge of SCD and its treatments on the part of ED staff [7]. Other barriers to effective management are technical in nature, such as difficulty in establishing timely intravenous (IV) access.

Gaps and variations in quality of care contribute to poor outcomes for patients with SCD [20,21]. To help address these inequities, the Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project began in 2010 to improve care and outcomes for patients with SCD. WISCH is a collaborative quality improvement (QI) project funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) that has the goal to use improvement science to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course (Ed note: see Editorial by Oyeku et al in this issue). As one of the HRSA-WISCH grantee networks, we undertook a QI project designed to decrease the quality gap in SCD medical care by creating and implementing a protocol for ED pain management for pediatric patients. Goals of the project were to improve the timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute VOE in the ED.

Methods

Setting

This ED QI initiative was implemented at Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, an urban free-standing pediatric hospital that serves a demographically diverse population. The hospital ED sees over 45,000 visits per year, with 250 visits per year for VOE. Residents in pediatrics, family medicine, and emergency medicine staff the ED. All attending physicians are subspecialists in pediatric emergency medicine. Study procedures were approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Intervention

A multidisciplinary team consisting of ED staff and sickle cell center staff drafted a nursing-driven protocol for the assessment and management of acute pain associated with VOE, incorporating elements from a protocol in use by another WISCH collaborative member. The protocol called for the immediate triage and assessment of all patients with SCD who presented with moderate to severe pain suggestive of VOE. Moderate to severe pain was defined as a pain score of ≥ 5 on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst pain imaginable. Exclusion criteria included a chief complaint of pain not considered secondary to VOE (eg, trauma, fracture). Patients were also excluded if they had been transferred from another facility. The protocol called for IV pain medication to be administered within 10 minutes of the patient being roomed, with re-evaluation at 20-minute intervals and re-dosing of pain medication based on the patient’s subsequent pain rating.

Measures

We selected performance measures from the bank developed by the WISCH team to track improvement and evaluate progress. These performance measures included (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, (2) percentage of patients that received their first dose of analgesic within 30 minutes of triage, (3) percentage of patients who had a pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage, and (4) percentage of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first dose of analgesic had been administered. Our aims were to have 80% of patients assessed and given pain medications within 30 minutes of triage, and to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, within 12 months of implementing our intervention.

Data Collection and Analysis

The WISCH project coordinator reviewed records of visits to the ED for a baseline period of 6 months and post-order set implementaton. Demographic data (age, gender), clinical data (hemoglobin type), pain scores, utilization data (number of ED visits during the study period), and data pertaining to the metrics chosen from the WISCH measurement bank were extracted from each eligible patient’s ED chart after the visit was completed. If patients were admitted, their length of hospitalization was extracted from their inpatient medical record.

All biostatistical analyses were conducted using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics computed at 2 time-points (pre and post order set implementation) were utilized to examine means, standard deviations and percentages. The 2 time-points were initially compared at the visit level of measurement, using Student’s t tests corrected for unequal variances where necessary for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables, to evaluate if there was an improvement in timely triage, assessment, and treatment of acute VOE pain for all ED visits pre and post order set implementation. To account for trends and possible correlations across the months post order set implementation, we ran a mixed linear model with repeated measures over time to compare visits during all months post order set implementation with the baseline months, for metric 1, time from triage to first pain medication. If significant differences were found, we used Dunnett’s method of multiple comparisons to determine which months differed from baseline. For metrics 2 through 4, we ran linear models with a binary outcome, a logit link function and using general estimating equations to determine trends and to account for correlations over time.

Secondary analyses were conducted to evaluate whether mean pain scores were significantly different over the course of the ED visit for the 78 unique patients seen post order set implementation. A multivariable mixed linear model, for the outcome of the third pain score, was used to assess the associations with prior scores and to control for potential covariates (age, gender, number of ED visits, hemoglobin type) that were determined in advance. A statistical significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests.

Results

Baseline data were collected from December 2011 to May 2012. The protocol was implemented in July 2012 and was utilized during 165 ED visits (91% of eligible visits) through April 2013. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between the 55 patients whose charts were reviewed prior to implementing the order set and the 78 unique patients treated thereafter. Pre order set implementation, the mean age was 14.6 ± 6.4 years; 60% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.8% of diagnoses). Post order set implementation, the mean age was 16.0 ± 8.0 years; 51.3% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.5% of diagnoses). The mean number of visits was 1.5 visits per patient with a range of 1–8 visits, both pre and post order set implementation. Thirty-one patients had ED visits at both time periods.

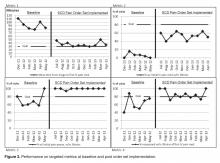

It can be seen in Figure 2 that staff performance on 3 of the 4 metrics (with the exception of initial analgesic within 30 minutes of triage) began to improve prior to implementing the order set. The mean length of ED stays decreased by 30 minutes, from a mean of 5.2 hours down to 4.7 hours (P < 0.05, Table). There was no significant change in the percentage of patients admitted to the inpatient unit.

We performed secondary analyses to determine if performance on our first metric, mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, was associated with any improvement on the third pain assessment for the patients enrolled post order set implementation. Looking at the first ED visit during the study period for the 78 unique patients, we found significant decreases in mean pain scores from the first to the second, from the second to the third, and from the first to the third assessment (P < 0.01). The mean pain scores were 8.3 ± 1.8, 5.9 ± 2.8, and 5.1 ± 3.0 on initial, second and third assessments, respectively. A multivariable model controlling for gender, hemoglobin type, number of ED visits and time to first pain medication showed that only the score at the second pain assessment (β = 0.88 ± 0.08, P < 0.001) was a significant predictor of the score at the third pain assessment.

Discussion

We demonstrated that a QI initiative to improve acute pain management resulted in more timely assessment and treatment of pain in pediatric patients with SCD. Significant improvements from baseline were achieved and sustained over a 10-month period in all 4 targeted metrics. We consistently exceeded our goal of having 80% of patients assessed within 30 minutes of triage, and our mean time to first pain medication (35.2 ± 22.8 minutes) came close to our goal of 30 minutes from triage. While we also achieved our goal to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, we fell short in the percent who received their initial pain medication within 30 minutes of triage (52.7% versus goal of 80%). Although the length of stay in the ED decreased, no change was observed in the percentage of patients who required admission to the inpatient unit. A secondary analysis showed that mean pain scores significantly decreased over the course of the ED visit, from severe to moderate intensity.

The improvements that we observed began prior to implementation of the order set. We recognize that simply raising awareness and educating staff about the importance of timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell related pain in the ED might be a potential confounder of our results. However, changes were sustained for 10 months post order set implementation and beyond, with no evidence that the performance on the target metrics is drifting back to baseline levels. Education and awareness-raising alone rarely result in sustained application of clinical practice guidelines [22]. We collaborated with NICHQ and other HRSA-WISCH grantees to systematically implement improvement science to ensure that the changes that we observed were indeed improvements and would be sustained [23] by first changing the system of care in the ED by introducing a standard order set [24,25]. We put a system into place to track use of the order set and to work with providers almost immediately if deviations were observed, to understand and overcome any barriers to the order set implementation. Systems in the ED and in the sickle cell center were aligned with the hospital’s QI initiatives [23].

Another strategy that we used to insure that the changes we observed would be sustained was to create a multidisciplinary team to build knowledge, skills, and new practices, including learning from other WISCH grantees and the NICHQ coordinating center [23]. We modified and adapted the intervention to our specific context [25]; although the outline of the order set was influenced by our WISCH colleagues, the final order set was structured to be consistent with other protocols within our institution. Finally, we included consumer input in the design of the project from the outset.

A previous study of a multi-institutional QI initiative aimed at improving acute SCD pain management for adult patients in the ED was unable to demonstrate an improvement in time to administration of initial analgesic [26]. Our study with pediatric patients was able to demonstrate a clinically meaningful decrease in the time to administration of first parenteral analgesic. The factors that account for the discrepant findings between these studies are likely multifactorial. Age (ie, pediatric vs. adult patients) may have played a role given that IV access may become increasingly difficult as patients with SCD age [26]. Education for providers should include the importance of alternative methods of administration of opioids, including subcutaneous and intranasal routes, to avoid delays when IV access is difficult. It is possible that negative provider attitudes converge with the documented increase in patient visits during the young adult years [27]. This may set up a challenging feedback loop wherein these vulnerable young adults are faced with greater stigma and consequently receive lower quality care, even when there is an attempt to carry out a standardized protocol.

We did not find that the QI intervention resulted in decreased admissions to the inpatient unit, with 68% of visits resulting in admission. In a recent pediatric SCD study, hospital admissions for pain control accounted for 78% of all admissions and 70% of readmissions within 30 days [28]. The investigators found that use of a SCD analgesic protocol including patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) improved quality of care as well as hospital readmission rates within 30 days (from 28% to 11%). Our ED QI protocol focused on only the first 90 minutes of the visit for pain. Our team has discussed the potential for starting the PCA in the ED and we should build on our success to focus on specific care that patients receive beyond their initial presentation. Further, we introduced pain action planning into outpatient care and need to continue to improve positive patient self-management strategies to ensure more seamless transition of pain management between home, ED, and inpatient settings.

Several valuable lessons were learned over the course of the ED QI initiative. Previous researchers [28] have emphasized the importance of coupling provider education with standardized order sets in efforts to improve the care of patients with SCD. Although we did not offer monthly formal education to our providers, the immediate follow-up when there were protocol deviations most likely served as teaching moments. These teaching moments also surfaced when some ED and hematology providers expressed concerns about the risk for oversedation with the rapid reassessment of pain and re-dosing of pain medications. Although rare, some parents also expressed that their child was being treated too vigorously with opioids. Our project highlighted the element of stigma that still accompanies the use of opioids for SCD pain management.

The project could not have been undertaken were it not for a small but determined multidisciplinary team of individuals who were personally invested in seeing the project come to fruition. The identification of physician and nurse champions who were enthusiastic about the project, invested in its conduct, and committed to its success was a cornerstone of the project’s success. These champions played an essential role in engaging staff interest in the project and oversaw the practicalities of implementing a new protocol in the ED. A spirit of collaboration, teamwork, and good communication between all involved parties was also critical. At the same time, we incorporated input from the treating ED and hematology clinicians using PDSA cycles as we were refining our protocol. We believe that our process enhanced buy-in from participating providers and clarified any issues that needed to be addressed in our setting, resulting in accelerated and sustained quality improvement.

Limitations

Although protocol-driven interventions are designed to provide a certain degree of uniformity of care, the protocol was not designed nor utilized in such a way that it superseded the best medical judgment of the treating clinicians. Deviations from the protocol were permissible when they were felt to be in the patient’s best interest. The study did not control for confounding variables such as disease severity, how long the patient had been in pain prior to coming to the ED, nor did we assess therapeutic interventions the patient had utilized at home prior to seeking out care in the ED. All of these factors could affect how well a patient might respond to treatment. We believe that sharing baseline data and monthly progress via run charts (graphs of data over time) with ED and sickle cell center staff and with consumer representatives enhanced the pace and focus of the project [23]. We had a dedicated person managing our data in real time through our HRSA funding, thus the project might not be generalizable to other institutions that do not have such staffing or access to the technology to allow project progress to be closely monitored by stakeholders.

Future Directions

With the goal of further reducing the time to administration of first analgesic dose in the ED setting, intranasal fentanyl will be utilized in our ED as the initial drug of choice for patients who do not object to or have a contraindication to its use. Collection of data from patients and family members is being undertaken to assess consumer satisfaction with the ED QI initiative. Recognizing that the ED management of acute pain addresses only one aspect of sickle cell pain, we are looking at ways to more comprehensively address pain. Individualized outpatient pain management plans are being created and patients and families are being encouraged and empowered to become active partners with their sickle cell providers in their own care. Although our initial efforts have focused on our pediatric patients, an additional aim of our project is to broaden the scope of our ED QI initiative to include community hospitals in the region that serve adult patients with SCD.

Conclusion

Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED has led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with VOE. A multidisciplinary approach, ongoing staff education, and commitment to the initiative have been necessary to sustain the improvements. Our success can provide a template for other QI initiatives in the ED that translate to improved patient care for other diseases. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we addressed our objective to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Theresa Freitas, RN, Lisa Hale, PNP, Carolyn Hoppe, MD, Ileana Mendez, RN, Helen Mitchell, Mary Rutherford, MD, Augusta Saulys, MD and the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland Emergency Medicine Department and Sickle Cell Center for their support.

Corresponding author: Marsha Treadwell, PhD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, 747 52nd St, Oakland, CA 94609, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was conducted as part of the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project. Further support came from a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Demonstration Project Grant No. U1EMC16492 and from NIH CTSA grant UL1 RR024131. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of WISCH, NICHQ, or HRSA.

1. Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, et al. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Preventive Med 2010;38 (4 Suppl):S536–41.

2. Benjamin L, Dampier C, Jacox A, et al. Guideline for the management of acute and chronic pain in sickle cell disease. American Pain Society; 1999.

3. Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, et al. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematology 2003;120:744–52.

4. Solomon LR. Pain management in adults with sickle cell disease in a medical center emergency department. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1025–32.

5. Lazio MP, Costello HH, Courtney DM, et al. A comparison of analgesic management for emergency department patients with sickle cell disease and renal colic. Clin J Pain 2010;26:199–205.

6. Shenoi R, Ma L, Syblik D, Yusuf S. Emergency department crowding and analgesic delay in pediatric sickle cell pain crises. Ped Emerg Care 2011;27:911–7.

7. Tanabe P, Artz N, Mark Courtney D, et al. Adult emergency department patients with sickle cell pain crisis: a learning collaborative model to improve analgesic management. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:399–407.

8. Zempsky WT. Evaluation and treatment of sickle cell pain in the emergency department: paths to a better future. Clin Ped Emerg Med 2010;11:265–73.

9. Haywood C Jr, Tanabe P, Naik R, et al. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:651–6.

10. Solomon LR. Treatment and prevention of pain due to vaso-occlusive crises in adults with sickle cell disease: an educational void. Blood 2008;111:997–1003.

11. Ballas SK. New era dawns on sickle cell pain. Blood 2010;116:311–2.

12. Haywood C Jr, Lanzkron S, Ratanawongsa N, et al. The association of provider communication with trust among adults with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:543–8.

13. Zempsky WT. Treatment of sickle cell pain: fostering trust and justice. JAMA 2009;302:2479–80.

14. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, Telfer P. Pain management and symptoms of substance dependence among patients with sickle cell disease. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1683–96.

15. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, et al. Understanding the causes of problematic pain management in sickle cell disease: evidence that pseudoaddiction plays a more important role than genuine analgesic dependence. J Pain Sympt Manag 2004;27:156–69.

16. Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:94–101.

17. Harris A, Parker N, Baker C. Adults with sickle cell. Psychol Health Med 1998;3:171–9.

18. Jenerette CM, Brewer C. Health-related stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1050–5.

19. Maxwell K, Streetly A, Bevan D. Experiences of hospital care and treatment seeking for pain from sickle cell disease: qualitative study. BMJ 1999;318:1585–90.

20. Oyeku SO, Wang CJ, Scoville R, et al. Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative: using quality improvement (QI) to achieve equity in health care quality, coordination, and outcomes for sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23(3 Suppl):34–48.

21. Wang CJ, Kavanagh PL, Little AA, et al. Quality-of-care indicators for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 2011;128:484–93.

22. Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Ed Health Prof 2007;27:6–15.

23. The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003.

24. Berwick DM. Improvement, trust, and the healthcare workforce. Qual Safety Health Care 2003;12:448–52.

25. Hovlid E, Bukve O, Haug K, et al. Sustainability of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from learning theory? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:235.

26. Tanabe P, Hafner JW, Martinovich Z, Artz N. Adult emergency department patients with sickle cell pain crisis: results from a quality improvement learning collaborative model to improve analgesic management. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:430–8.

27. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

28. Frei-Jones MJ, Field JJ, DeBaun MR. Multi-modal intervention and prospective implementation of standardized sickle cell pain admission orders reduces 30-day readmission rate. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:401–5.

From the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, CA.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine whether a quality improvement (QI) initiative would result in more timely assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell–related pain for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) treated in the emergency department (ED).

- Methods: We created and implemented a protocol for SCD pain management in the ED with the goals of improving (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose; (2) percentage of patients that received their first analgesic dose within 30 minutes of triage, and (3) percentage of patients who had pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage and who were re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first analgesic dose.

- Results: Significant improvements were achieved between baseline (55 patient visits) and post order set implementation (165 visits) in time from triage to administration of first analgesic (decreased from 89.9 ± 50.5 to 35.2 ± 22.8 minutes, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits receiving pain medications within 30 minutes of triage (from 7% to 53%, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits assessed within 30 minutes of triage (from 64% to 99.4%, P < 0.001); and percentage of patient visits re-assessed within 30 minutes of initial analgesic (from 54% to 86%, P < 0.001).

- Conclusions: Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with pain. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we address our objective of decreasing the quality gap in SCD medical care.

Pain is the leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) [1]. In the United States, 78% of the nearly 200,000 annual ED visits for SCD are for a complaint of pain [1]. Guidelines for the management of sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain episodes (VOE) suggest prompt initiation of parenteral opioids, use of effective opioid doses, and repeat opioid doses at frequent intervals [2–4]. Adherence to guidelines is poor. Both pediatric and adult patients with SCD experience delays in the initiation of analgesics and are routinely undertreated with respect to opioid dosing [5–8]. Even after controlling for race, the delays in time to analgesic administration experienced by patients with SCD exceed the delays encountered by patients who present to the ED with other types of pain [5,9]. These disparities warrant efforts designed to improve the delivery of quality care to patients with SCD.

Barriers to rapid and appropriate care of VOE in the ED are multifactorial and include systems-based limitations, such as acuity of the ED census, staffing limitations (eg, nurse-to-patient ratios), and facility limitations (eg, room availability) [6]. Provider-based limitations may include lack of awareness of available guidelines [10]. Biases and misunderstandings amongst providers about sickle cell pain and adequate medication dosing may also play a role [11–13]. These provider biases often lead to undertreatment of the pain, which in turn can lead to pseudoaddiction (drug-seeking behavior due to inadequate treatment) and a cycle of increased ED and inpatient utilization [14,15].

Patient-specific barriers to effective ED management of pain are equally complex. Previous negative experiences in the ED can lead patients and families to delay seeking care or avoid the ED altogether despite severe VOE pain [16]. Patients report frustration with the lack of consideration that they receive for their reports of pain, perceived insensitivity of hospital staff, inadequate analgesic administration, staff preoccupation with concerns of drug addiction, and an overall lack of respect and trust [17–19]. Patients also perceive a lack of knowledge of SCD and its treatments on the part of ED staff [7]. Other barriers to effective management are technical in nature, such as difficulty in establishing timely intravenous (IV) access.

Gaps and variations in quality of care contribute to poor outcomes for patients with SCD [20,21]. To help address these inequities, the Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project began in 2010 to improve care and outcomes for patients with SCD. WISCH is a collaborative quality improvement (QI) project funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) that has the goal to use improvement science to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course (Ed note: see Editorial by Oyeku et al in this issue). As one of the HRSA-WISCH grantee networks, we undertook a QI project designed to decrease the quality gap in SCD medical care by creating and implementing a protocol for ED pain management for pediatric patients. Goals of the project were to improve the timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute VOE in the ED.

Methods

Setting

This ED QI initiative was implemented at Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, an urban free-standing pediatric hospital that serves a demographically diverse population. The hospital ED sees over 45,000 visits per year, with 250 visits per year for VOE. Residents in pediatrics, family medicine, and emergency medicine staff the ED. All attending physicians are subspecialists in pediatric emergency medicine. Study procedures were approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Intervention

A multidisciplinary team consisting of ED staff and sickle cell center staff drafted a nursing-driven protocol for the assessment and management of acute pain associated with VOE, incorporating elements from a protocol in use by another WISCH collaborative member. The protocol called for the immediate triage and assessment of all patients with SCD who presented with moderate to severe pain suggestive of VOE. Moderate to severe pain was defined as a pain score of ≥ 5 on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst pain imaginable. Exclusion criteria included a chief complaint of pain not considered secondary to VOE (eg, trauma, fracture). Patients were also excluded if they had been transferred from another facility. The protocol called for IV pain medication to be administered within 10 minutes of the patient being roomed, with re-evaluation at 20-minute intervals and re-dosing of pain medication based on the patient’s subsequent pain rating.

Measures

We selected performance measures from the bank developed by the WISCH team to track improvement and evaluate progress. These performance measures included (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, (2) percentage of patients that received their first dose of analgesic within 30 minutes of triage, (3) percentage of patients who had a pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage, and (4) percentage of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first dose of analgesic had been administered. Our aims were to have 80% of patients assessed and given pain medications within 30 minutes of triage, and to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, within 12 months of implementing our intervention.

Data Collection and Analysis

The WISCH project coordinator reviewed records of visits to the ED for a baseline period of 6 months and post-order set implementaton. Demographic data (age, gender), clinical data (hemoglobin type), pain scores, utilization data (number of ED visits during the study period), and data pertaining to the metrics chosen from the WISCH measurement bank were extracted from each eligible patient’s ED chart after the visit was completed. If patients were admitted, their length of hospitalization was extracted from their inpatient medical record.

All biostatistical analyses were conducted using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics computed at 2 time-points (pre and post order set implementation) were utilized to examine means, standard deviations and percentages. The 2 time-points were initially compared at the visit level of measurement, using Student’s t tests corrected for unequal variances where necessary for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables, to evaluate if there was an improvement in timely triage, assessment, and treatment of acute VOE pain for all ED visits pre and post order set implementation. To account for trends and possible correlations across the months post order set implementation, we ran a mixed linear model with repeated measures over time to compare visits during all months post order set implementation with the baseline months, for metric 1, time from triage to first pain medication. If significant differences were found, we used Dunnett’s method of multiple comparisons to determine which months differed from baseline. For metrics 2 through 4, we ran linear models with a binary outcome, a logit link function and using general estimating equations to determine trends and to account for correlations over time.

Secondary analyses were conducted to evaluate whether mean pain scores were significantly different over the course of the ED visit for the 78 unique patients seen post order set implementation. A multivariable mixed linear model, for the outcome of the third pain score, was used to assess the associations with prior scores and to control for potential covariates (age, gender, number of ED visits, hemoglobin type) that were determined in advance. A statistical significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests.

Results

Baseline data were collected from December 2011 to May 2012. The protocol was implemented in July 2012 and was utilized during 165 ED visits (91% of eligible visits) through April 2013. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between the 55 patients whose charts were reviewed prior to implementing the order set and the 78 unique patients treated thereafter. Pre order set implementation, the mean age was 14.6 ± 6.4 years; 60% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.8% of diagnoses). Post order set implementation, the mean age was 16.0 ± 8.0 years; 51.3% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.5% of diagnoses). The mean number of visits was 1.5 visits per patient with a range of 1–8 visits, both pre and post order set implementation. Thirty-one patients had ED visits at both time periods.

It can be seen in Figure 2 that staff performance on 3 of the 4 metrics (with the exception of initial analgesic within 30 minutes of triage) began to improve prior to implementing the order set. The mean length of ED stays decreased by 30 minutes, from a mean of 5.2 hours down to 4.7 hours (P < 0.05, Table). There was no significant change in the percentage of patients admitted to the inpatient unit.

We performed secondary analyses to determine if performance on our first metric, mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, was associated with any improvement on the third pain assessment for the patients enrolled post order set implementation. Looking at the first ED visit during the study period for the 78 unique patients, we found significant decreases in mean pain scores from the first to the second, from the second to the third, and from the first to the third assessment (P < 0.01). The mean pain scores were 8.3 ± 1.8, 5.9 ± 2.8, and 5.1 ± 3.0 on initial, second and third assessments, respectively. A multivariable model controlling for gender, hemoglobin type, number of ED visits and time to first pain medication showed that only the score at the second pain assessment (β = 0.88 ± 0.08, P < 0.001) was a significant predictor of the score at the third pain assessment.

Discussion

We demonstrated that a QI initiative to improve acute pain management resulted in more timely assessment and treatment of pain in pediatric patients with SCD. Significant improvements from baseline were achieved and sustained over a 10-month period in all 4 targeted metrics. We consistently exceeded our goal of having 80% of patients assessed within 30 minutes of triage, and our mean time to first pain medication (35.2 ± 22.8 minutes) came close to our goal of 30 minutes from triage. While we also achieved our goal to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, we fell short in the percent who received their initial pain medication within 30 minutes of triage (52.7% versus goal of 80%). Although the length of stay in the ED decreased, no change was observed in the percentage of patients who required admission to the inpatient unit. A secondary analysis showed that mean pain scores significantly decreased over the course of the ED visit, from severe to moderate intensity.

The improvements that we observed began prior to implementation of the order set. We recognize that simply raising awareness and educating staff about the importance of timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell related pain in the ED might be a potential confounder of our results. However, changes were sustained for 10 months post order set implementation and beyond, with no evidence that the performance on the target metrics is drifting back to baseline levels. Education and awareness-raising alone rarely result in sustained application of clinical practice guidelines [22]. We collaborated with NICHQ and other HRSA-WISCH grantees to systematically implement improvement science to ensure that the changes that we observed were indeed improvements and would be sustained [23] by first changing the system of care in the ED by introducing a standard order set [24,25]. We put a system into place to track use of the order set and to work with providers almost immediately if deviations were observed, to understand and overcome any barriers to the order set implementation. Systems in the ED and in the sickle cell center were aligned with the hospital’s QI initiatives [23].

Another strategy that we used to insure that the changes we observed would be sustained was to create a multidisciplinary team to build knowledge, skills, and new practices, including learning from other WISCH grantees and the NICHQ coordinating center [23]. We modified and adapted the intervention to our specific context [25]; although the outline of the order set was influenced by our WISCH colleagues, the final order set was structured to be consistent with other protocols within our institution. Finally, we included consumer input in the design of the project from the outset.

A previous study of a multi-institutional QI initiative aimed at improving acute SCD pain management for adult patients in the ED was unable to demonstrate an improvement in time to administration of initial analgesic [26]. Our study with pediatric patients was able to demonstrate a clinically meaningful decrease in the time to administration of first parenteral analgesic. The factors that account for the discrepant findings between these studies are likely multifactorial. Age (ie, pediatric vs. adult patients) may have played a role given that IV access may become increasingly difficult as patients with SCD age [26]. Education for providers should include the importance of alternative methods of administration of opioids, including subcutaneous and intranasal routes, to avoid delays when IV access is difficult. It is possible that negative provider attitudes converge with the documented increase in patient visits during the young adult years [27]. This may set up a challenging feedback loop wherein these vulnerable young adults are faced with greater stigma and consequently receive lower quality care, even when there is an attempt to carry out a standardized protocol.

We did not find that the QI intervention resulted in decreased admissions to the inpatient unit, with 68% of visits resulting in admission. In a recent pediatric SCD study, hospital admissions for pain control accounted for 78% of all admissions and 70% of readmissions within 30 days [28]. The investigators found that use of a SCD analgesic protocol including patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) improved quality of care as well as hospital readmission rates within 30 days (from 28% to 11%). Our ED QI protocol focused on only the first 90 minutes of the visit for pain. Our team has discussed the potential for starting the PCA in the ED and we should build on our success to focus on specific care that patients receive beyond their initial presentation. Further, we introduced pain action planning into outpatient care and need to continue to improve positive patient self-management strategies to ensure more seamless transition of pain management between home, ED, and inpatient settings.

Several valuable lessons were learned over the course of the ED QI initiative. Previous researchers [28] have emphasized the importance of coupling provider education with standardized order sets in efforts to improve the care of patients with SCD. Although we did not offer monthly formal education to our providers, the immediate follow-up when there were protocol deviations most likely served as teaching moments. These teaching moments also surfaced when some ED and hematology providers expressed concerns about the risk for oversedation with the rapid reassessment of pain and re-dosing of pain medications. Although rare, some parents also expressed that their child was being treated too vigorously with opioids. Our project highlighted the element of stigma that still accompanies the use of opioids for SCD pain management.

The project could not have been undertaken were it not for a small but determined multidisciplinary team of individuals who were personally invested in seeing the project come to fruition. The identification of physician and nurse champions who were enthusiastic about the project, invested in its conduct, and committed to its success was a cornerstone of the project’s success. These champions played an essential role in engaging staff interest in the project and oversaw the practicalities of implementing a new protocol in the ED. A spirit of collaboration, teamwork, and good communication between all involved parties was also critical. At the same time, we incorporated input from the treating ED and hematology clinicians using PDSA cycles as we were refining our protocol. We believe that our process enhanced buy-in from participating providers and clarified any issues that needed to be addressed in our setting, resulting in accelerated and sustained quality improvement.

Limitations

Although protocol-driven interventions are designed to provide a certain degree of uniformity of care, the protocol was not designed nor utilized in such a way that it superseded the best medical judgment of the treating clinicians. Deviations from the protocol were permissible when they were felt to be in the patient’s best interest. The study did not control for confounding variables such as disease severity, how long the patient had been in pain prior to coming to the ED, nor did we assess therapeutic interventions the patient had utilized at home prior to seeking out care in the ED. All of these factors could affect how well a patient might respond to treatment. We believe that sharing baseline data and monthly progress via run charts (graphs of data over time) with ED and sickle cell center staff and with consumer representatives enhanced the pace and focus of the project [23]. We had a dedicated person managing our data in real time through our HRSA funding, thus the project might not be generalizable to other institutions that do not have such staffing or access to the technology to allow project progress to be closely monitored by stakeholders.

Future Directions

With the goal of further reducing the time to administration of first analgesic dose in the ED setting, intranasal fentanyl will be utilized in our ED as the initial drug of choice for patients who do not object to or have a contraindication to its use. Collection of data from patients and family members is being undertaken to assess consumer satisfaction with the ED QI initiative. Recognizing that the ED management of acute pain addresses only one aspect of sickle cell pain, we are looking at ways to more comprehensively address pain. Individualized outpatient pain management plans are being created and patients and families are being encouraged and empowered to become active partners with their sickle cell providers in their own care. Although our initial efforts have focused on our pediatric patients, an additional aim of our project is to broaden the scope of our ED QI initiative to include community hospitals in the region that serve adult patients with SCD.

Conclusion

Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED has led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with VOE. A multidisciplinary approach, ongoing staff education, and commitment to the initiative have been necessary to sustain the improvements. Our success can provide a template for other QI initiatives in the ED that translate to improved patient care for other diseases. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we addressed our objective to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Theresa Freitas, RN, Lisa Hale, PNP, Carolyn Hoppe, MD, Ileana Mendez, RN, Helen Mitchell, Mary Rutherford, MD, Augusta Saulys, MD and the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland Emergency Medicine Department and Sickle Cell Center for their support.

Corresponding author: Marsha Treadwell, PhD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, 747 52nd St, Oakland, CA 94609, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was conducted as part of the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project. Further support came from a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Demonstration Project Grant No. U1EMC16492 and from NIH CTSA grant UL1 RR024131. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of WISCH, NICHQ, or HRSA.

From the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, Oakland, CA.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine whether a quality improvement (QI) initiative would result in more timely assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell–related pain for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) treated in the emergency department (ED).

- Methods: We created and implemented a protocol for SCD pain management in the ED with the goals of improving (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose; (2) percentage of patients that received their first analgesic dose within 30 minutes of triage, and (3) percentage of patients who had pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage and who were re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first analgesic dose.

- Results: Significant improvements were achieved between baseline (55 patient visits) and post order set implementation (165 visits) in time from triage to administration of first analgesic (decreased from 89.9 ± 50.5 to 35.2 ± 22.8 minutes, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits receiving pain medications within 30 minutes of triage (from 7% to 53%, P < 0.001); percentage of patient visits assessed within 30 minutes of triage (from 64% to 99.4%, P < 0.001); and percentage of patient visits re-assessed within 30 minutes of initial analgesic (from 54% to 86%, P < 0.001).

- Conclusions: Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with pain. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we address our objective of decreasing the quality gap in SCD medical care.

Pain is the leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) [1]. In the United States, 78% of the nearly 200,000 annual ED visits for SCD are for a complaint of pain [1]. Guidelines for the management of sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain episodes (VOE) suggest prompt initiation of parenteral opioids, use of effective opioid doses, and repeat opioid doses at frequent intervals [2–4]. Adherence to guidelines is poor. Both pediatric and adult patients with SCD experience delays in the initiation of analgesics and are routinely undertreated with respect to opioid dosing [5–8]. Even after controlling for race, the delays in time to analgesic administration experienced by patients with SCD exceed the delays encountered by patients who present to the ED with other types of pain [5,9]. These disparities warrant efforts designed to improve the delivery of quality care to patients with SCD.

Barriers to rapid and appropriate care of VOE in the ED are multifactorial and include systems-based limitations, such as acuity of the ED census, staffing limitations (eg, nurse-to-patient ratios), and facility limitations (eg, room availability) [6]. Provider-based limitations may include lack of awareness of available guidelines [10]. Biases and misunderstandings amongst providers about sickle cell pain and adequate medication dosing may also play a role [11–13]. These provider biases often lead to undertreatment of the pain, which in turn can lead to pseudoaddiction (drug-seeking behavior due to inadequate treatment) and a cycle of increased ED and inpatient utilization [14,15].

Patient-specific barriers to effective ED management of pain are equally complex. Previous negative experiences in the ED can lead patients and families to delay seeking care or avoid the ED altogether despite severe VOE pain [16]. Patients report frustration with the lack of consideration that they receive for their reports of pain, perceived insensitivity of hospital staff, inadequate analgesic administration, staff preoccupation with concerns of drug addiction, and an overall lack of respect and trust [17–19]. Patients also perceive a lack of knowledge of SCD and its treatments on the part of ED staff [7]. Other barriers to effective management are technical in nature, such as difficulty in establishing timely intravenous (IV) access.

Gaps and variations in quality of care contribute to poor outcomes for patients with SCD [20,21]. To help address these inequities, the Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project began in 2010 to improve care and outcomes for patients with SCD. WISCH is a collaborative quality improvement (QI) project funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) that has the goal to use improvement science to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course (Ed note: see Editorial by Oyeku et al in this issue). As one of the HRSA-WISCH grantee networks, we undertook a QI project designed to decrease the quality gap in SCD medical care by creating and implementing a protocol for ED pain management for pediatric patients. Goals of the project were to improve the timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute VOE in the ED.

Methods

Setting

This ED QI initiative was implemented at Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, an urban free-standing pediatric hospital that serves a demographically diverse population. The hospital ED sees over 45,000 visits per year, with 250 visits per year for VOE. Residents in pediatrics, family medicine, and emergency medicine staff the ED. All attending physicians are subspecialists in pediatric emergency medicine. Study procedures were approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Intervention

A multidisciplinary team consisting of ED staff and sickle cell center staff drafted a nursing-driven protocol for the assessment and management of acute pain associated with VOE, incorporating elements from a protocol in use by another WISCH collaborative member. The protocol called for the immediate triage and assessment of all patients with SCD who presented with moderate to severe pain suggestive of VOE. Moderate to severe pain was defined as a pain score of ≥ 5 on a numeric scale of 0 to 10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst pain imaginable. Exclusion criteria included a chief complaint of pain not considered secondary to VOE (eg, trauma, fracture). Patients were also excluded if they had been transferred from another facility. The protocol called for IV pain medication to be administered within 10 minutes of the patient being roomed, with re-evaluation at 20-minute intervals and re-dosing of pain medication based on the patient’s subsequent pain rating.

Measures

We selected performance measures from the bank developed by the WISCH team to track improvement and evaluate progress. These performance measures included (1) mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, (2) percentage of patients that received their first dose of analgesic within 30 minutes of triage, (3) percentage of patients who had a pain assessment performed within 30 minutes of triage, and (4) percentage of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after the first dose of analgesic had been administered. Our aims were to have 80% of patients assessed and given pain medications within 30 minutes of triage, and to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, within 12 months of implementing our intervention.

Data Collection and Analysis

The WISCH project coordinator reviewed records of visits to the ED for a baseline period of 6 months and post-order set implementaton. Demographic data (age, gender), clinical data (hemoglobin type), pain scores, utilization data (number of ED visits during the study period), and data pertaining to the metrics chosen from the WISCH measurement bank were extracted from each eligible patient’s ED chart after the visit was completed. If patients were admitted, their length of hospitalization was extracted from their inpatient medical record.

All biostatistical analyses were conducted using Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics computed at 2 time-points (pre and post order set implementation) were utilized to examine means, standard deviations and percentages. The 2 time-points were initially compared at the visit level of measurement, using Student’s t tests corrected for unequal variances where necessary for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables, to evaluate if there was an improvement in timely triage, assessment, and treatment of acute VOE pain for all ED visits pre and post order set implementation. To account for trends and possible correlations across the months post order set implementation, we ran a mixed linear model with repeated measures over time to compare visits during all months post order set implementation with the baseline months, for metric 1, time from triage to first pain medication. If significant differences were found, we used Dunnett’s method of multiple comparisons to determine which months differed from baseline. For metrics 2 through 4, we ran linear models with a binary outcome, a logit link function and using general estimating equations to determine trends and to account for correlations over time.

Secondary analyses were conducted to evaluate whether mean pain scores were significantly different over the course of the ED visit for the 78 unique patients seen post order set implementation. A multivariable mixed linear model, for the outcome of the third pain score, was used to assess the associations with prior scores and to control for potential covariates (age, gender, number of ED visits, hemoglobin type) that were determined in advance. A statistical significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests.

Results

Baseline data were collected from December 2011 to May 2012. The protocol was implemented in July 2012 and was utilized during 165 ED visits (91% of eligible visits) through April 2013. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between the 55 patients whose charts were reviewed prior to implementing the order set and the 78 unique patients treated thereafter. Pre order set implementation, the mean age was 14.6 ± 6.4 years; 60% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.8% of diagnoses). Post order set implementation, the mean age was 16.0 ± 8.0 years; 51.3% were female and the primary diagnosis was HgbSS disease (61.5% of diagnoses). The mean number of visits was 1.5 visits per patient with a range of 1–8 visits, both pre and post order set implementation. Thirty-one patients had ED visits at both time periods.

It can be seen in Figure 2 that staff performance on 3 of the 4 metrics (with the exception of initial analgesic within 30 minutes of triage) began to improve prior to implementing the order set. The mean length of ED stays decreased by 30 minutes, from a mean of 5.2 hours down to 4.7 hours (P < 0.05, Table). There was no significant change in the percentage of patients admitted to the inpatient unit.

We performed secondary analyses to determine if performance on our first metric, mean time from triage to first analgesic dose, was associated with any improvement on the third pain assessment for the patients enrolled post order set implementation. Looking at the first ED visit during the study period for the 78 unique patients, we found significant decreases in mean pain scores from the first to the second, from the second to the third, and from the first to the third assessment (P < 0.01). The mean pain scores were 8.3 ± 1.8, 5.9 ± 2.8, and 5.1 ± 3.0 on initial, second and third assessments, respectively. A multivariable model controlling for gender, hemoglobin type, number of ED visits and time to first pain medication showed that only the score at the second pain assessment (β = 0.88 ± 0.08, P < 0.001) was a significant predictor of the score at the third pain assessment.

Discussion

We demonstrated that a QI initiative to improve acute pain management resulted in more timely assessment and treatment of pain in pediatric patients with SCD. Significant improvements from baseline were achieved and sustained over a 10-month period in all 4 targeted metrics. We consistently exceeded our goal of having 80% of patients assessed within 30 minutes of triage, and our mean time to first pain medication (35.2 ± 22.8 minutes) came close to our goal of 30 minutes from triage. While we also achieved our goal to have 80% of patients re-assessed within 30 minutes after having received their first dose of an analgesic, we fell short in the percent who received their initial pain medication within 30 minutes of triage (52.7% versus goal of 80%). Although the length of stay in the ED decreased, no change was observed in the percentage of patients who required admission to the inpatient unit. A secondary analysis showed that mean pain scores significantly decreased over the course of the ED visit, from severe to moderate intensity.

The improvements that we observed began prior to implementation of the order set. We recognize that simply raising awareness and educating staff about the importance of timely and appropriate assessment and treatment of acute sickle cell related pain in the ED might be a potential confounder of our results. However, changes were sustained for 10 months post order set implementation and beyond, with no evidence that the performance on the target metrics is drifting back to baseline levels. Education and awareness-raising alone rarely result in sustained application of clinical practice guidelines [22]. We collaborated with NICHQ and other HRSA-WISCH grantees to systematically implement improvement science to ensure that the changes that we observed were indeed improvements and would be sustained [23] by first changing the system of care in the ED by introducing a standard order set [24,25]. We put a system into place to track use of the order set and to work with providers almost immediately if deviations were observed, to understand and overcome any barriers to the order set implementation. Systems in the ED and in the sickle cell center were aligned with the hospital’s QI initiatives [23].

Another strategy that we used to insure that the changes we observed would be sustained was to create a multidisciplinary team to build knowledge, skills, and new practices, including learning from other WISCH grantees and the NICHQ coordinating center [23]. We modified and adapted the intervention to our specific context [25]; although the outline of the order set was influenced by our WISCH colleagues, the final order set was structured to be consistent with other protocols within our institution. Finally, we included consumer input in the design of the project from the outset.

A previous study of a multi-institutional QI initiative aimed at improving acute SCD pain management for adult patients in the ED was unable to demonstrate an improvement in time to administration of initial analgesic [26]. Our study with pediatric patients was able to demonstrate a clinically meaningful decrease in the time to administration of first parenteral analgesic. The factors that account for the discrepant findings between these studies are likely multifactorial. Age (ie, pediatric vs. adult patients) may have played a role given that IV access may become increasingly difficult as patients with SCD age [26]. Education for providers should include the importance of alternative methods of administration of opioids, including subcutaneous and intranasal routes, to avoid delays when IV access is difficult. It is possible that negative provider attitudes converge with the documented increase in patient visits during the young adult years [27]. This may set up a challenging feedback loop wherein these vulnerable young adults are faced with greater stigma and consequently receive lower quality care, even when there is an attempt to carry out a standardized protocol.

We did not find that the QI intervention resulted in decreased admissions to the inpatient unit, with 68% of visits resulting in admission. In a recent pediatric SCD study, hospital admissions for pain control accounted for 78% of all admissions and 70% of readmissions within 30 days [28]. The investigators found that use of a SCD analgesic protocol including patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) improved quality of care as well as hospital readmission rates within 30 days (from 28% to 11%). Our ED QI protocol focused on only the first 90 minutes of the visit for pain. Our team has discussed the potential for starting the PCA in the ED and we should build on our success to focus on specific care that patients receive beyond their initial presentation. Further, we introduced pain action planning into outpatient care and need to continue to improve positive patient self-management strategies to ensure more seamless transition of pain management between home, ED, and inpatient settings.

Several valuable lessons were learned over the course of the ED QI initiative. Previous researchers [28] have emphasized the importance of coupling provider education with standardized order sets in efforts to improve the care of patients with SCD. Although we did not offer monthly formal education to our providers, the immediate follow-up when there were protocol deviations most likely served as teaching moments. These teaching moments also surfaced when some ED and hematology providers expressed concerns about the risk for oversedation with the rapid reassessment of pain and re-dosing of pain medications. Although rare, some parents also expressed that their child was being treated too vigorously with opioids. Our project highlighted the element of stigma that still accompanies the use of opioids for SCD pain management.

The project could not have been undertaken were it not for a small but determined multidisciplinary team of individuals who were personally invested in seeing the project come to fruition. The identification of physician and nurse champions who were enthusiastic about the project, invested in its conduct, and committed to its success was a cornerstone of the project’s success. These champions played an essential role in engaging staff interest in the project and oversaw the practicalities of implementing a new protocol in the ED. A spirit of collaboration, teamwork, and good communication between all involved parties was also critical. At the same time, we incorporated input from the treating ED and hematology clinicians using PDSA cycles as we were refining our protocol. We believe that our process enhanced buy-in from participating providers and clarified any issues that needed to be addressed in our setting, resulting in accelerated and sustained quality improvement.

Limitations

Although protocol-driven interventions are designed to provide a certain degree of uniformity of care, the protocol was not designed nor utilized in such a way that it superseded the best medical judgment of the treating clinicians. Deviations from the protocol were permissible when they were felt to be in the patient’s best interest. The study did not control for confounding variables such as disease severity, how long the patient had been in pain prior to coming to the ED, nor did we assess therapeutic interventions the patient had utilized at home prior to seeking out care in the ED. All of these factors could affect how well a patient might respond to treatment. We believe that sharing baseline data and monthly progress via run charts (graphs of data over time) with ED and sickle cell center staff and with consumer representatives enhanced the pace and focus of the project [23]. We had a dedicated person managing our data in real time through our HRSA funding, thus the project might not be generalizable to other institutions that do not have such staffing or access to the technology to allow project progress to be closely monitored by stakeholders.

Future Directions

With the goal of further reducing the time to administration of first analgesic dose in the ED setting, intranasal fentanyl will be utilized in our ED as the initial drug of choice for patients who do not object to or have a contraindication to its use. Collection of data from patients and family members is being undertaken to assess consumer satisfaction with the ED QI initiative. Recognizing that the ED management of acute pain addresses only one aspect of sickle cell pain, we are looking at ways to more comprehensively address pain. Individualized outpatient pain management plans are being created and patients and families are being encouraged and empowered to become active partners with their sickle cell providers in their own care. Although our initial efforts have focused on our pediatric patients, an additional aim of our project is to broaden the scope of our ED QI initiative to include community hospitals in the region that serve adult patients with SCD.

Conclusion

Implementation of a QI initiative in the ED has led to expeditious care for pediatric patients with SCD presenting with VOE. A multidisciplinary approach, ongoing staff education, and commitment to the initiative have been necessary to sustain the improvements. Our success can provide a template for other QI initiatives in the ED that translate to improved patient care for other diseases. A QI framework provided us with unique challenges but also invaluable lessons as we addressed our objective to improve outcomes for patients with SCD across the life course.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Theresa Freitas, RN, Lisa Hale, PNP, Carolyn Hoppe, MD, Ileana Mendez, RN, Helen Mitchell, Mary Rutherford, MD, Augusta Saulys, MD and the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland Emergency Medicine Department and Sickle Cell Center for their support.

Corresponding author: Marsha Treadwell, PhD, Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, 747 52nd St, Oakland, CA 94609, [email protected].

Funding/support: This research was conducted as part of the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) Working to Improve Sickle Cell Healthcare (WISCH) project. Further support came from a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Demonstration Project Grant No. U1EMC16492 and from NIH CTSA grant UL1 RR024131. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of WISCH, NICHQ, or HRSA.

1. Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, et al. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Preventive Med 2010;38 (4 Suppl):S536–41.

2. Benjamin L, Dampier C, Jacox A, et al. Guideline for the management of acute and chronic pain in sickle cell disease. American Pain Society; 1999.

3. Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, et al. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematology 2003;120:744–52.

4. Solomon LR. Pain management in adults with sickle cell disease in a medical center emergency department. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1025–32.

5. Lazio MP, Costello HH, Courtney DM, et al. A comparison of analgesic management for emergency department patients with sickle cell disease and renal colic. Clin J Pain 2010;26:199–205.

6. Shenoi R, Ma L, Syblik D, Yusuf S. Emergency department crowding and analgesic delay in pediatric sickle cell pain crises. Ped Emerg Care 2011;27:911–7.

7. Tanabe P, Artz N, Mark Courtney D, et al. Adult emergency department patients with sickle cell pain crisis: a learning collaborative model to improve analgesic management. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:399–407.

8. Zempsky WT. Evaluation and treatment of sickle cell pain in the emergency department: paths to a better future. Clin Ped Emerg Med 2010;11:265–73.

9. Haywood C Jr, Tanabe P, Naik R, et al. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:651–6.

10. Solomon LR. Treatment and prevention of pain due to vaso-occlusive crises in adults with sickle cell disease: an educational void. Blood 2008;111:997–1003.

11. Ballas SK. New era dawns on sickle cell pain. Blood 2010;116:311–2.

12. Haywood C Jr, Lanzkron S, Ratanawongsa N, et al. The association of provider communication with trust among adults with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:543–8.

13. Zempsky WT. Treatment of sickle cell pain: fostering trust and justice. JAMA 2009;302:2479–80.

14. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, Telfer P. Pain management and symptoms of substance dependence among patients with sickle cell disease. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1683–96.

15. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, et al. Understanding the causes of problematic pain management in sickle cell disease: evidence that pseudoaddiction plays a more important role than genuine analgesic dependence. J Pain Sympt Manag 2004;27:156–69.

16. Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:94–101.

17. Harris A, Parker N, Baker C. Adults with sickle cell. Psychol Health Med 1998;3:171–9.

18. Jenerette CM, Brewer C. Health-related stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1050–5.

19. Maxwell K, Streetly A, Bevan D. Experiences of hospital care and treatment seeking for pain from sickle cell disease: qualitative study. BMJ 1999;318:1585–90.

20. Oyeku SO, Wang CJ, Scoville R, et al. Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative: using quality improvement (QI) to achieve equity in health care quality, coordination, and outcomes for sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23(3 Suppl):34–48.

21. Wang CJ, Kavanagh PL, Little AA, et al. Quality-of-care indicators for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 2011;128:484–93.

22. Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Ed Health Prof 2007;27:6–15.

23. The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003.

24. Berwick DM. Improvement, trust, and the healthcare workforce. Qual Safety Health Care 2003;12:448–52.

25. Hovlid E, Bukve O, Haug K, et al. Sustainability of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from learning theory? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:235.

26. Tanabe P, Hafner JW, Martinovich Z, Artz N. Adult emergency department patients with sickle cell pain crisis: results from a quality improvement learning collaborative model to improve analgesic management. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:430–8.

27. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

28. Frei-Jones MJ, Field JJ, DeBaun MR. Multi-modal intervention and prospective implementation of standardized sickle cell pain admission orders reduces 30-day readmission rate. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:401–5.

1. Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, et al. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Preventive Med 2010;38 (4 Suppl):S536–41.

2. Benjamin L, Dampier C, Jacox A, et al. Guideline for the management of acute and chronic pain in sickle cell disease. American Pain Society; 1999.

3. Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, et al. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematology 2003;120:744–52.

4. Solomon LR. Pain management in adults with sickle cell disease in a medical center emergency department. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1025–32.

5. Lazio MP, Costello HH, Courtney DM, et al. A comparison of analgesic management for emergency department patients with sickle cell disease and renal colic. Clin J Pain 2010;26:199–205.

6. Shenoi R, Ma L, Syblik D, Yusuf S. Emergency department crowding and analgesic delay in pediatric sickle cell pain crises. Ped Emerg Care 2011;27:911–7.

7. Tanabe P, Artz N, Mark Courtney D, et al. Adult emergency department patients with sickle cell pain crisis: a learning collaborative model to improve analgesic management. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:399–407.

8. Zempsky WT. Evaluation and treatment of sickle cell pain in the emergency department: paths to a better future. Clin Ped Emerg Med 2010;11:265–73.

9. Haywood C Jr, Tanabe P, Naik R, et al. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:651–6.

10. Solomon LR. Treatment and prevention of pain due to vaso-occlusive crises in adults with sickle cell disease: an educational void. Blood 2008;111:997–1003.

11. Ballas SK. New era dawns on sickle cell pain. Blood 2010;116:311–2.

12. Haywood C Jr, Lanzkron S, Ratanawongsa N, et al. The association of provider communication with trust among adults with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:543–8.

13. Zempsky WT. Treatment of sickle cell pain: fostering trust and justice. JAMA 2009;302:2479–80.

14. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, Telfer P. Pain management and symptoms of substance dependence among patients with sickle cell disease. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1683–96.

15. Elander J, Lusher J, Bevan D, et al. Understanding the causes of problematic pain management in sickle cell disease: evidence that pseudoaddiction plays a more important role than genuine analgesic dependence. J Pain Sympt Manag 2004;27:156–69.

16. Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:94–101.

17. Harris A, Parker N, Baker C. Adults with sickle cell. Psychol Health Med 1998;3:171–9.

18. Jenerette CM, Brewer C. Health-related stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. J Nat Med Assoc 2010;102:1050–5.