User login

Reoperation Rates After Cartilage Restoration Procedures in the Knee: Analysis of a Large US Commercial Database

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the operating room (OR) following microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and osteochondral allograft (OCA) procedures at 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years. Current Procedural Terminology codes for all patients undergoing MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA were used to search a prospectively collected, commercially available private payer insurance company database from 2007 to 2011. Within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery, the database was searched for the occurrence of these same patients undergoing knee diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy, lysis of adhesions, synovectomy, arthroscopy for infection or lavage, arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies, chondroplasty, MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA, and/or knee arthroplasty. Descriptive statistical analysis and contingency table analysis were performed. A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX, 640 ACI, 386 open OATS, 997 arthroscopic OATS, 714 open OCA, and 894 arthroscopic OCA procedures. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. At 2 years, patients who underwent MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA had reoperation rates of 14.65%, 29.69%, 8.82%, and 12.22%, respectively. There was a statistically significantly increased risk for ACI return to OR within all intervals (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative treatment options. With a large US commercial insurance database from 2007 to 2011, reparative procedures were favored for chondral injuries, but yielded an increased risk for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative approaches, yet cell-based approaches yielded a significantly increased risk for a return to the OR.

Continue to: Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage

Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage defects in the knee are difficult to manage, particularly in the young, athletic patient population. Fortunately, a variety of cartilage repair (direct repair of the cartilage or those procedures which attempt to generate fibrocartilage) and restoration (those aimed at restoring hyaline cartilage) procedures are available, with encouraging short- and long-term clinical outcomes. After failure of nonoperative management, several surgical options are available for treating symptomatic focal chondral defects, including microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and open and arthroscopic osteochondral allograft (OCA) transplantation procedures.1,2 When appropriately indicated, each of these techniques has demonstrated good to excellent clinical outcomes with respect to reducing pain and improving function.3-5

While major complications following cartilage surgery are uncommon, the need for reoperation following an index articular cartilage operation is poorly understood. Recently, McCormick and colleagues6 found that reoperation within the first 2 years following meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) is associated with an increased likelihood of revision MAT or future arthroplasty. Given the association between early reoperation following meniscus restoration surgery and subsequent failure, an improved understanding of the epidemiology and implications of reoperations following cartilage restoration surgery is warranted. Further, in deciding which treatment option is best suited to a particular patient, the rate of return to the operating room (OR) should be taken into consideration, as this could potentially influence surgical decision-making as to which procedure to perform, especially in value-based care decision-making environments.

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the OR for knee procedures following cartilage restoration at intervals of 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years across a large-scale US patient database. The authors hypothesize that the rate of return to the OR following knee cartilage repair or restoration procedures will be under 20% during the first post-operative year, with increasing reoperation rates over time. A secondary hypothesis is that there will be no difference in reoperation rates according to sex, but that younger patients (those younger than 40 years) will have higher reoperation rates than older patients.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected, large-scale, and commercially available private payer insurance company database (PearlDiver) from 2007 to 2011. The PearlDiver database is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant, publicly available national database consisting of a collection of private payer records, with United Health Group representing the contributing health plan. The database has more than 30 million patient records and contains Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes related to orthopedic procedures. From 2007 to 2011, the private payer database captured between 5.9 million and 6.2 million patients per year.

Our search was based on the CPT codes for MFX (29879), ACI (27412), OATS (29866, 29867), and OCA (27415, 27416). Return to the OR for revision surgery for the above-mentioned procedures was classified as patients with a diagnosis of diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy (CPT 29870), lysis of adhesions (CPT 29884), synovectomy (29875, 29876), arthroscopy for infection or lavage (CPT 29871), arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies (29874), chondroplasty (29877), unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (27446), total knee arthroplasty (27447), and/or patellar arthroplasty (27438). Patient records were followed for reoperations occurring within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after the index cartilage procedure. All data were compared based on patient age and sex.

Table 1. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Sex | ||||||

MFX | ACI | Open OATS | Arthroscopic OATS | Open OCA | Arthroscopic OCA | |

Females | 20,589 | 276 | 167 | 401 | 275 | 350 |

Males | 22,987 | 364 | 219 | 596 | 439 | 544 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 386 | 997 | 714 | 894 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis of this study was primarily descriptive to demonstrate the incidence for each code at each time interval. One-way analysis of variance, Chi-square analysis, and contingency tables were used to compare the incidence of each type of procedure throughout the various time intervals. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.20 (International Business Machines).

RESULTS

A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX (92.3%) 640 ACI (1.4%), 386 open OATS (0.82%), 997 arthroscopic OATS (2.11%), 714 open OCA (1.51%), and 894 arthroscopic OCA (1.89%) procedures. A summary of the procedures performed, broken down by age and sex, is provided in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 25,149 male patients (53.3%) underwent surgical procedures compared to 22,058 female patients (46.7%). For each category of procedure (MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA), there was a significantly higher proportion of males than females undergoing surgery (P < .0001 for all). Surgical treatment with MFX was consistently the most frequently performed surgery across all age groups (92.31%), while cell-based therapy with ACI was the least frequently performed procedure across all age ranges (1.36%). Restorative OATS and OCA techniques were performed with the greatest frequency in the 15-year-old to 19-year-old age group, but were not utilized in patients over 64 years of age (Table 2).

Table 2. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Age | ||||

Age (y) | MFX | ACI | OATS | OCA |

10 to 14 | 572 | 22 | 74 | 47 |

15 to 19 | 1984 | 83 | 254 | 235 |

20 to 24 | 1468 | 54 | 140 | 144 |

25 to 29 | 1787 | 74 | 152 | 176 |

30 to 34 | 2824 | 114 | 152 | 204 |

35 to 39 | 4237 | 96 | 153 | 210 |

40 to 44 | 5441 | 103 | 166 | 217 |

45 to 49 | 7126 | 57 | 149 | 180 |

50 to 54 | 7004 | 25 | 83 | 140 |

55 to 59 | 6410 | 12 | 40 | 40 |

60 to 64 | 4409 | 0 | 20 | 15 |

65 to 69 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

70 to 74 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 1383 | 1608 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

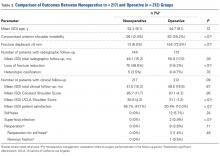

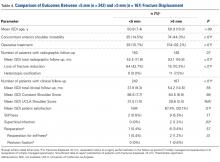

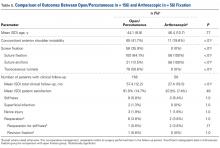

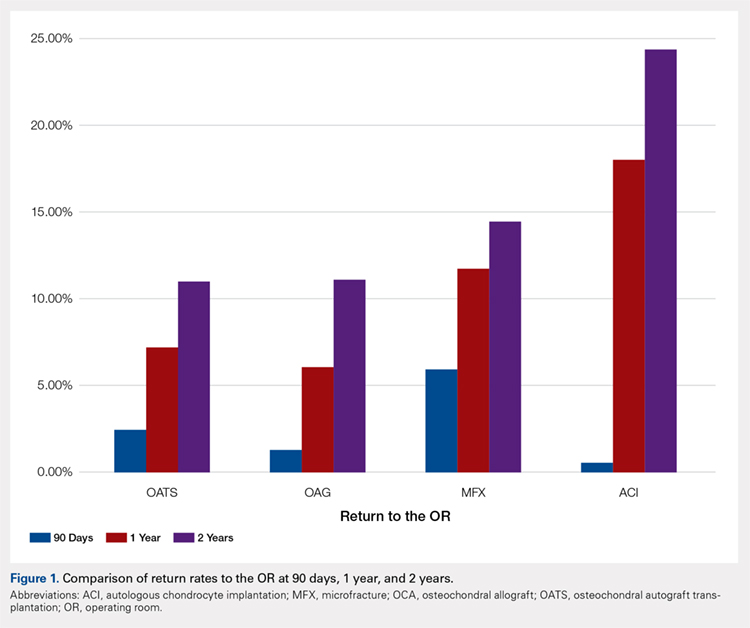

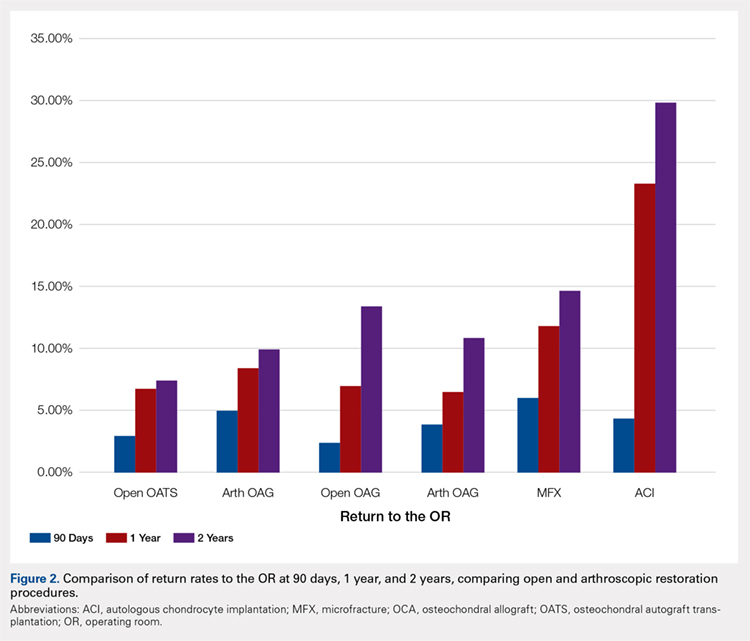

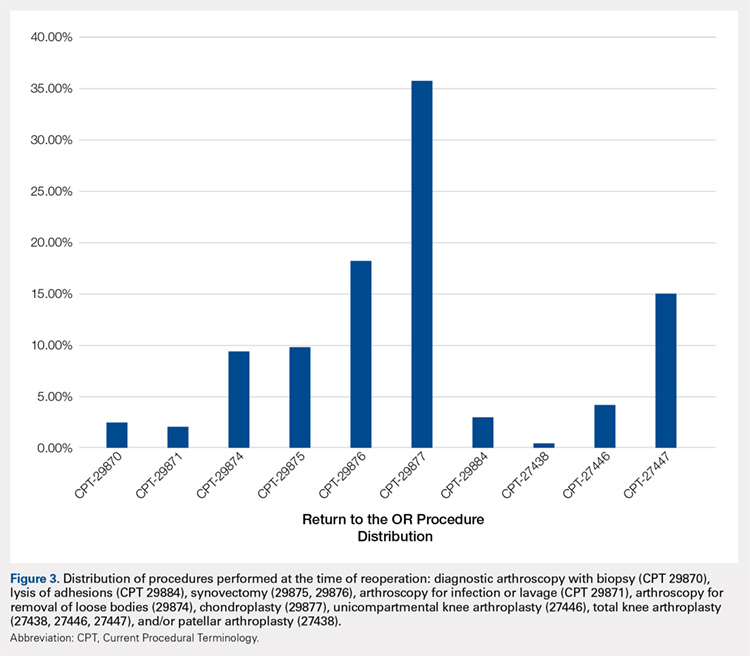

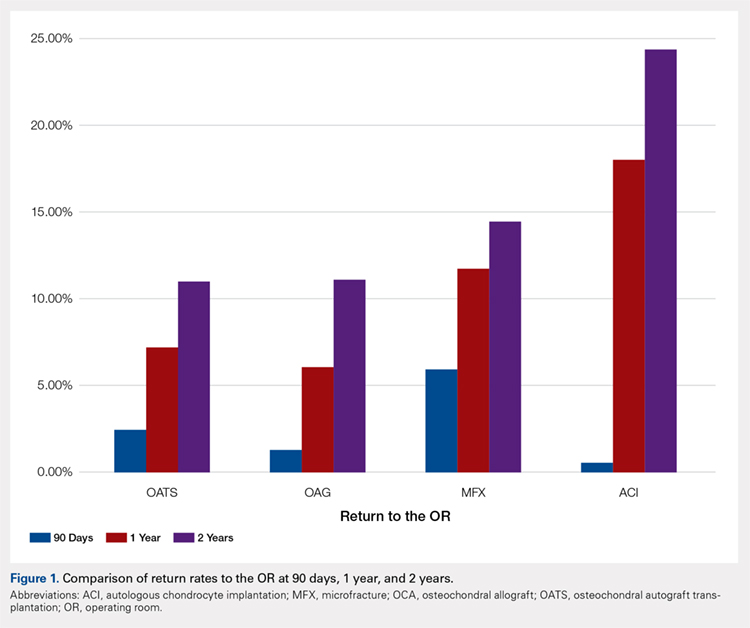

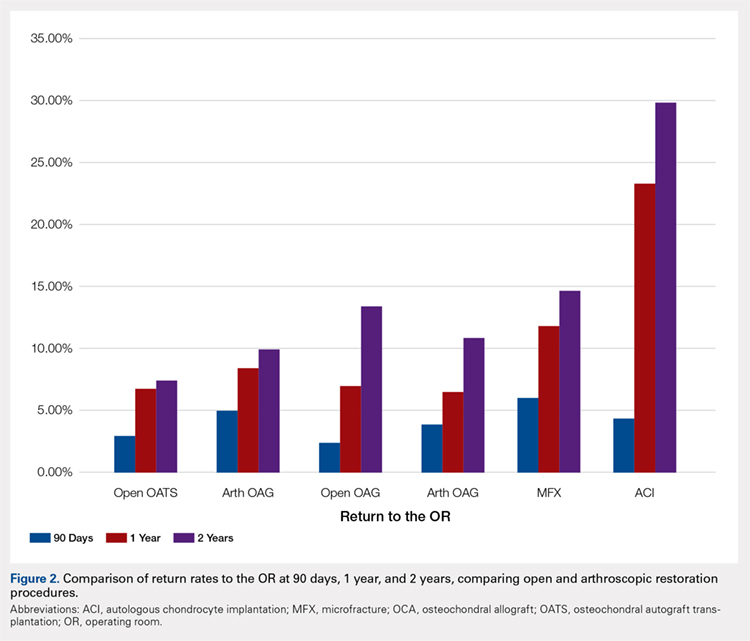

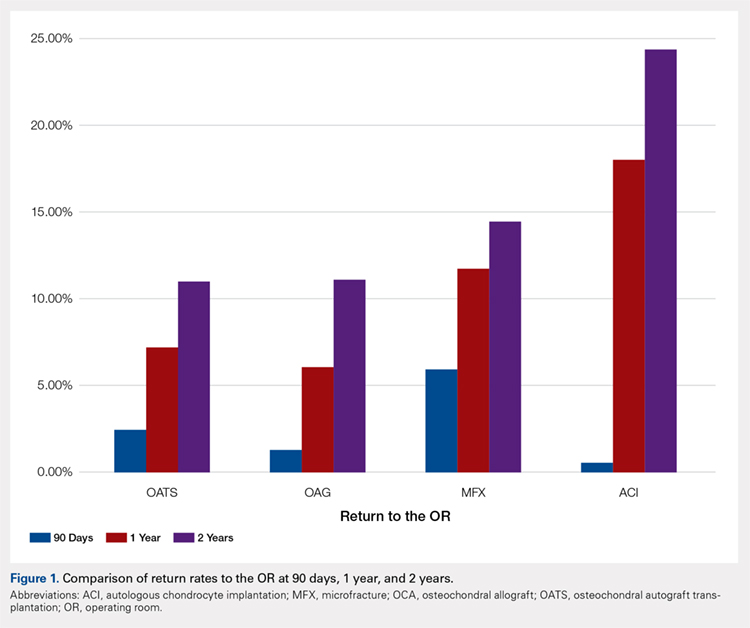

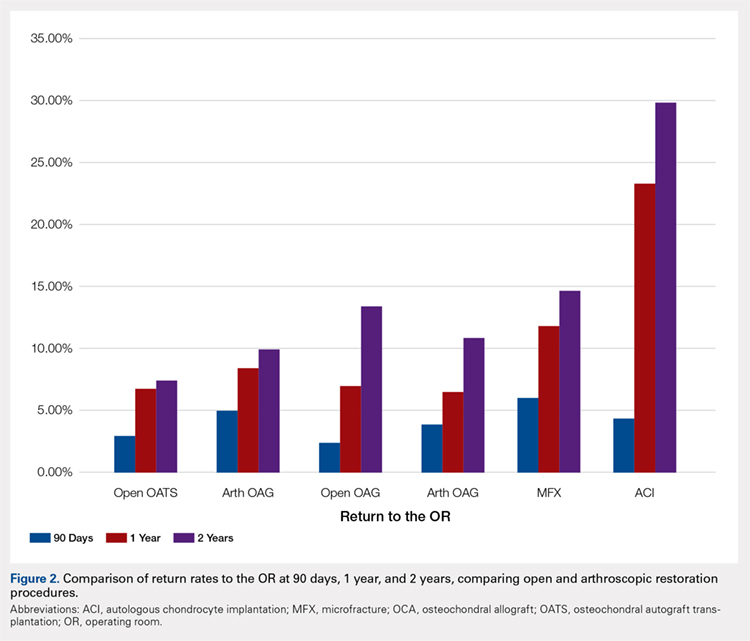

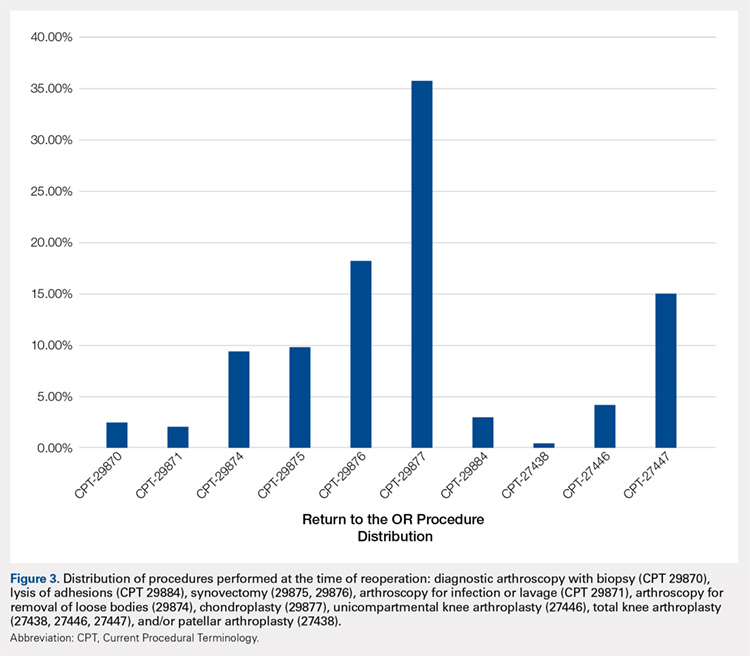

A summary of all reoperation data is provided in Tables 3 to 7 and Figures 1 and 2. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. Patients who underwent MFX had reoperation rates of 6.05% at 90 days, 11.80% at 1 year, and 14.65% at 2 years. Patients who underwent ACI had reoperation rates of 4.53% at 90 days, 23.28% at 1 year, and 29.69% at 2 years. Patients who had open and arthroscopic OATS had reoperation rates of 3.122% and 5.12% at 90 days, 6.74% and 8.53% at 1 year, and 7.51% and 10.13% at 2 years, respectively. Patients who underwent open and arthroscopic OCA had reoperation rates of 2.52% and 3.91% at 90 days, 7.14% and 6.60% at 1 year, and 13.59% and 10.85% at 2 years (Table 3). There was a statistically significantly increased risk for reoperation following ACI within all intervals compared to all other surgical techniques (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty at 6.70%. There was no significant difference between failure rates (revision OATS/OCA or conversion to arthroplasty) between the restorative treatment options, with 14 failures for OATS (9.52% of reoperations at 2 years) compared to 22 failures for OCA (12.7% of reoperations at 2 years, P = .358). Among the entire cohort of cartilage surgery patients, arthroscopic chondroplasty was the most frequent procedure performed at the time of reoperation at all time points assessed, notably accounting for 33.08% of reoperations 2 years following microfracture, 51.58% of reoperations at 2 years following ACI, 53.06% of reoperations at 2 years following OATS, and 54.07% of reoperations at 2 years following OCA (Figure 3, Tables 4–7).

Table 3. Comparison of Return to OR Following MFX, ACI, OCA, and OATS | |||||||

Procedure | Total No. of Cases in Study Period | No. of Reoperations at 90 Days | Return to OR Rate at 90 Days | No. of Reoperations at 1 Year | Return to OR Rate at 1 Year | No. of Reoperations at 2 Years | Return to OR Rate at 2 Years |

MFX | 43,576 | 2636 | 6.05% | 5142 | 11.80% | 6385 | 14.65% |

ACI | 640 | 29 | 4.53% | 149 | 23.28% | 190 | 29.69% |

Open OATS | 386 | 12 | 3.12% | 26 | 6.74% | 29 | 7.51% |

Arthroscopic OATS | 997 | 51 | 5.12% | 85 | 8.53% | 101 | 10.13% |

Open OCA | 714 | 18 | 2.52% | 51 | 7.14% | 97 | 13.59% |

Arthroscopic OCA | 894 | 161 | 3.91% | 59 | 6.60% | 97 | 10.85% |

Weighted average for all procedures |

| 5.87% |

| 11.94% |

| 14.90% | |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 4. Rate of Return to OR Following MFX (n = 43,574) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 54 | 122 | 162 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 84 | 102 | 104 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 300 | 468 | 549 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 324 | 528 | 611 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 557 | 926 | 1087 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 1063 | 1722 | 2112 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 61 | 129 | 171 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 38 | 49 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 51 | 242 | 328 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 142 | 865 | 1212 |

Total | 2636 | 5142 | 6385 | |

Return to OR | 6.05% | 11.80% | 14.65% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; MFX, microfracture; OR, operating room.

Table 5. Rate of Return to OR Following ACI (n = 640) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Daysa | 1 Yeara | 2 Yearsa |

Revision ACI | 27412 | 29 | 33 | 35 |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | -1 | 12 | 20 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | -1 | 71 | 98 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | -1 | 33 | 37 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Total | 29 | 149 | 190 | |

Return to OR | 4.53% | 23.28% | 29.69% | |

aA -1 denotes No. <11 within the PearlDiver database, and exact numbers are not reported due to patient privacy considerations.

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OR, operating room.

Table 6. Rate of Return to OR Following OATS (n = 1320) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 12 | 13 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 16 | 25 | 28 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 17 | 58 | 78 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Total | 33 | 95 | 147 | |

Return to OR | 2.50% | 7.20% | 11.14% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 7. Rate of Return to OR Following OCA Transplantation (n = 1531) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Year |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 15 | 19 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 0 | 20 | 38 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 22 | 59 | 93 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

Total | 22 | 94 | 172 | |

Return to OR | 1.44% | 6.14% | 11.23% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OR, operating room.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

The principle findings of this study demonstrate that there is an overall reoperation rate of 14.90% at 2 years following cartilage repair/restoration surgery, with the highest reoperation rates following MFX at 90 days, and ACI at both 1 year and 2 years following the index procedure. Also, patients undergoing index MFX as the index procedure have the highest risk for conversion to arthroplasty, reoperation rates for all cartilage surgeries increase over time, and arthroscopic chondroplasty is the most frequent procedure performed at the time of reoperation.

The management of symptomatic articular cartilage knee pathology is extremely challenging. With improvements in surgical technique, instrumentation, and clinical decision-making, indications are constantly evolving. Techniques that may work for “small” defects, though there is some debate as to what constitutes a “small” defect, are not necessarily going to be successful for larger defects, and this certainly varies depending on where the defect is located within the knee joint (distal femur vs patella vs trochlea, etc.). Recently, in a 2015 analysis of 3 level I or II studies, Miller and colleagues7 demonstrated both MFX and OATS to be viable, cost-effective, first-line treatment options for articular cartilage injuries, with similar clinical outcomes at 8.7 years. The authors noted cumulative reoperation rates of 29% among patients undergoing MFX compared to 13% among patients undergoing OATS. While ACI and OCA procedures were not included in their study, the reported reoperation rates of 29% following MFX and 13% following OATS at nearly 10 years suggest a possible increased need for reoperation following MFX over time (approximately 15% at 2 years in our study) and a stable rate of reoperation following OATS (approximately 11% at 2 years in our study). This finding is significant, as one of the goals with these procedures is to deliver effective, long-lasting pain relief and restoration of function. Interestingly, in this study, restorative OATS and OCA techniques were performed with the greatest frequency in the 15-year-old to 19-year-old age group, but were not performed in patients older than 64 years. This may be explained by the higher prevalence of acute traumatic injuries and osteochondritis dissecans diagnoses in younger patients compared with older patients, as these diagnoses are more often indicated to undergo restorative procedures as opposed to marrow stimulation.

In a 2016 systematic review of 20 studies incorporating 1117 patients, Campbell and colleagues8 assessed return-to-play rates following MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA. The authors noted that return to sport (RTS) rates were greatest following OATS (89%), followed by OCA (88%), ACI (84%), and MFX (75%). Positive prognostic factors for RTS included younger age, shorter duration of preoperative symptoms, no history of prior ipsilateral knee surgery, and smaller chondral defects. Reoperation rates between the 4 techniques were not statistically compared in their study. Interestingly, in 2013, Chalmers and colleagues9 conducted a separate systematic review of 20 studies comprising 1375 patients undergoing MFX, ACI, or OATS. In their study, the authors found significant advantages following ACI and OATS compared to MFX with respect to patient-reported outcome scores but noted significantly faster RTS rates with MFX. Reoperation rates were noted to be similar between the 3 procedures (25% for ACI, 21% for MFX, and 28% for OATS) at an average 3.7 years following the index procedure. When considering these 2 systematic reviews together, despite a faster RTS rate following MFX, a greater proportion of patients seem to be able to RTS over time following other procedures such as OATS, OCA, and ACI. Unfortunately, these reviews do not provide insight as to the role, if any, of reoperation on return to play rates nor on overall clinical outcome scores on patients undergoing articular cartilage surgery. However, this information is valuable when counseling athletes who are in season and would like to RTS as soon as possible as opposed to those who do not have tight time constraints for when they need to RTS.

Regardless of the cartilage technique chosen, the goals of surgery remain similar—to reduce pain and improve function. For athletes, the ultimate goal is to return to the same level of play that the athlete was able to achieve prior to injury. Certainly, the need for reoperation following a cartilage surgery has implications on pain, function, and ability to RTS. Our review of nearly 50,000 cartilage surgeries demonstrates that reoperations following cartilage repair surgery are not uncommon, with a rate of 14.90% at 2 years, and that while reoperation rates are the highest following ACI, the rate of conversion to knee arthroplasty is highest following MFX. Due to the limitations of the PearlDiver database, it is not possible to determine the clinical outcomes of patients undergoing reoperation following cartilage surgery, but certainly, given these data, reoperation is clearly not necessarily indicative of clinical failure. This is highlighted by the fact that the most common procedure performed at the time of reoperation is arthroscopic chondroplasty, which, despite being an additional surgical procedure, may be acceptable for patients who wish to RTS, particularly in the setting of an index ACI in which there may be graft hypertrophy. Ideally, additional studies incorporating a cost-effectiveness analysis of each of the procedures, incorporating reoperation rates as well as patient-reported clinical outcomes, would be helpful to truly determine the patient and societal implications of reoperation following cartilage repair/restoration.

Many of the advantages and disadvantages of the described cartilage repair/restoration procedures have been well described.10-17 Microfracture is the most commonly utilized first-line repair/restoration option for small articular cartilage lesions, mainly due to its low cost, low morbidity, and relatively low level of difficulty.18 Despite these advantages, MFX is not without limitations, and the need for revision cartilage restoration and/or conversion to arthroplasty is concerning. In 2013, Salzmann and colleagues19 evaluated a cohort of 454 patients undergoing MFX for a symptomatic knee defect and noted a reoperation rate of 26.9% (n = 123) within 2 years of the index surgery, with risk factors for reoperation noted to include an increased number of pre-MFX ipsilateral knee surgeries, patellofemoral lesions, smoking, and lower preoperative numeric analog scale scores. The definition of reoperation in their study is unfortunately not described, and thus the extent of reoperation (arthroscopy to arthroplasty) is unclear. In a 2009 systematic review of 3122 patients (28 studies) undergoing MFX conducted by Mithoefer and colleagues,20 revision rates were noted to range from 2% to 31% depending on the study analyzed, with increasing revision rates after 2 years. Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of the included studies makes it difficult to determine which patients tend to fail over time.

Continue to: OATS...

OATS is a promising cartilage restoration technique indicated for treatment of patients with large, uncontained chondral lesions, and/or lesions with both bone and cartilage loss.1 OCA is similar to OATS but uses allograft tissue instead of autograft tissue and is typically considered a viable treatment option in larger lesions (>2 cm2).21 Cell-based ACI therapy has evolved substantially over the past decade and is now available as a third-generation model utilizing biodegradable 3-dimensional scaffolds seeded with chondrocytes. Reoperation rates following ACI can often be higher than those following other cartilage treatments, particularly given the known complication of graft hypertrophy and/or delamination. Harris and colleagues22 conducted a systematic review of 5276 subjects undergoing ACI (all generations), noting an overall reoperation rate of 33%, but a failure rate of 5.8% at an average of 22 months following ACI. Risk factors for reoperation included periosteal-based ACI as well as open (vs arthroscopic) ACI. In this study, we found a modestly lower return to OR rate of 29.69% at 2 years.

When the outcomes of patients undergoing OATS or OCA are compared to those of patients undergoing MFX or ACI, it can be difficult to interpret the results, as the indications for performing these procedures tend to be very different. Further, the reasons for reoperation, as well as the procedures performed at the time of reoperation, are often poorly described, making it difficult to truly quantify the risk of reoperation and the implications of reoperation for patients undergoing any of these index cartilage procedures.

Overall, in this database, the return to the OR rate approaches 15% at 2 years following cartilage surgery, with cell-based therapy demonstrating higher reoperation rates at 2 years, without the risk of conversion to arthroplasty. Reoperation rates appear to stabilize at 1 year following surgery and consist mostly of minor arthroscopic procedures. These findings can help surgeons counsel patients as to the rate and type of reoperations that can be expected following cartilage surgery. Additional research incorporating patient-reported outcomes and patient-specific risk factors are needed to complement these data as to the impact of reoperations on overall clinical outcomes. Further, studies incorporating 90-day, 1-year, and 2-year costs associated with cartilage surgery will help to determine which index procedure is the most cost effective over the short- and long-term.

LIMITATIONS

This study is not without limitations. The PearlDiver database is reliant upon accurate CPT and ICD-9 coding, which creates a potential for a reporting bias. The overall reliability of the analyses is dependent on the quality of the available data, which, as noted in previous PearlDiver studies,18,23-28 may include inaccurate billing codes, miscoding, and/or non-coding by physicians as potential sources of error. At the time of this study, the PearlDiver database did not provide consistent data points on laterality, and thus it is possible that the reported rates of reoperation overestimate the true reoperation rate following a given procedure. Fortunately, the reoperation rates for each procedure analyzed in this database study are consistent with those previously presented in the literature. In addition, it is not uncommon for patients receiving one of these procedures to have previously been treated with one of the others. Due to the inherent limitations of the PearlDiver database, this study did not investigate concomitant procedures performed along with the index procedure, nor did it investigate confounding factors such as comorbidities. The PearlDiver database does not provide data on defect size, location within the knee, concomitant pathologies (eg, meniscus tear), prior surgeries, or patient comorbidities, and while important, these factors cannot be accounted for in our analysis. The inability to account for these important factors, particularly concomitant diagnoses, procedures, and lesion size/location, represents an important limitation of this study, as this is a source of selection bias and may influence the need for reoperation in a given patient. Despite these limitations, the results of this study are supported by previous and current literature. In addition, the PearlDiver database, as a HIPAA-compliant database, does not report exact numbers when the value of the outcome of interest is between 0 and 10, which prohibits analysis of any cartilage procedure performed in a cohort of patients greater than 1 and less than 11. Finally, while not necessarily a limitation, it should be noted that CPT 29879 is not specific for microfracture, as the code also includes abrasion arthroplasty and drilling. Due to the limitations of the methodology of searching the database for this code, it is unclear as to how many patients underwent actual microfracture vs abrasion arthroplasty.

CONCLUSION

Within a large US commercial insurance database from 2007 to 2011, reparative procedures were favored for chondral injuries, but yielded an increased risk for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference between failure/revision rates among the restorative approaches, yet cell-based approaches yielded a significantly increased risk for a return to the OR.

- Farr J, Cole B, Dhawan A, Kercher J, Sherman S. Clinical cartilage restoration: evolution and overview. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2696-2705. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1764-z.

- Alford JW, Cole BJ. Cartilage restoration, part 1: basic science, historical perspective, patient evaluation, and treatment options. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):295-306. doi:10.1177/03635465004273510.

- Alford JW, Cole BJ. Cartilage restoration, part 2: techniques, outcomes, and future directions. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(3):443-460. doi:10.1177/0363546505274578.

- Gudas R, Gudaitė A, Pocius A, et al. Ten-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized clinical study of mosaic osteochondral autologous transplantation versus microfracture for the treatment of osteochondral defects in the knee joint of athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2499-2508. doi:10.1177/0363546512458763.

- Saris DBF, Vanlauwe J, Victor J, et al. Treatment of symptomatic cartilage defects of the knee: characterized chondrocyte implantation results in better clinical outcome at 36 months in a randomized trial compared to microfracture. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(suppl 1):10-19. doi:10.1177/0363546509350694.

- McCormick F, Harris JD, Abrams GD, et al. Survival and reoperation rates after meniscal allograft transplantation: analysis of failures for 172 consecutive transplants at a minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):892-897. doi:10.1177/0363546513520115.

- Miller DJ, Smith MV, Matava MJ, Wright RW, Brophy RH. Microfracture and osteochondral autograft transplantation are cost-effective treatments for articular cartilage lesions of the distal femur. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(9):2175-2181. doi:10.1177/0363546515591261.

- Campbell AB, Pineda M, Harris JD, Flanigan DC. Return to sport after articular cartilage repair in athletes' knees: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(4):651-668.

- Chalmers PN, Vigneswaran H, Harris JD, Cole BJ. Activity-related outcomes of articular cartilage surgery: a systematic review. Cartilage. 2013;4(3):193-203.

- Bentley G, Biant LC, Vijayan S, Macmull S, Skinner JA, Carrington RW. Minimum ten-year results of a prospective randomised study of autologous chondrocyte implantation versus mosaicplasty for symptomatic articular cartilage lesions of the knee. JBone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(4):504-509. doi:10.1177/1947603513481603.

- Beris AE, Lykissas MG, Kostas-Agnantis I, Manoudis GN. Treatment of full-thickness chondral defects of the knee with autologous chondrocyte implantation: a functional evaluation with long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):562-567.

- Chahal J, Gross AE, Gross C, et al. Outcomes of osteochondral allograft transplantation in the knee. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):575-588. doi:10.1177/0363546511428778.

- Emmerson BC, Görtz S, Jamali AA, Chung C, Amiel D, Bugbee WD. Fresh osteochondral allografting in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyle. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(6):907-914. doi:10.1177/0363546507299932.

- Gudas R, Stankevičius E, Monastyreckienė E, Pranys D, Kalesinskas R. Osteochondral autologous transplantation versus microfracture for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in the knee joint in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(9):834-842. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0067-0.

- Lynch TS, Patel RM, Benedick A, Amin NH, Jones MH, Miniaci A. Systematic review of autogenous osteochondral transplant outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):746-754. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.018.

- Niemeyer P, Porichis S, Steinwachs M, et al. Long-term outcomes after first-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation for cartilage defects of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(1):150-157. doi:10.1177/0363546513506593.

- Ulstein S, Årøen A, Røtterud J, Løken S, Engebretsen L, Heir S. Microfracture technique versus osteochondral autologous transplantation mosaicplasty in patients with articular chondral lesions of the knee: a prospective randomized trial with long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(6):1207-1215. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2843-6.

- Montgomery S, Foster B, Ngo S, et al. Trends in the surgical treatment of articular cartilage defects of the knee in the United States. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(9):2070-2075. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2614-9.

- Salzmann GM, Sah B, Südkamp NP, Niemeyer P. Reoperative characteristics after microfracture of knee cartilage lesions in 454 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):365-371. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-1973-y.

- Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR. Clinical efficacy of the microfracture technique for articular cartilage repair in the knee: an evidence-based systematic analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):2053-2063. doi:10.1177/0363546508328414.

- Wajsfisz A, Makridis KG, Djian P. Arthroscopic retrograde osteochondral autograft transplantation for cartilage lesions of the tibial plateau: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):411-415. doi:10.1177/0363546512469091.

- Harris JD, Siston RA, Brophy RH, Lattermann C, Carey JL, Flanigan DC. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation–a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779-791. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.010.

- Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339. doi:10.1177/0363546513495641.

- Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T, et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):661-665. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.005.

- Yeranosian MG, Arshi A, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Incidence of acute postoperative infections requiring reoperation after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):437-441. doi:10.1177/0363546513510686.

- Zhang AL, Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization: current practice patterns in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):436-443. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.12.013.

- Werner BC, Carr JB, Wiggins JC, Gwathmey FW, Browne JA. Manipulation under anesthesia after total knee arthroplasty is associated with an increased incidence of subsequent revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(suppl 9):72-75. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.061.

- Carr JB 2nd, Werner BC, Browne JA. Trends and outcomes in the treatment of failed septic total knee arthroplasty: comparing arthrodesis and above-knee amputation. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(7):1574-1577. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.010.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the operating room (OR) following microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and osteochondral allograft (OCA) procedures at 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years. Current Procedural Terminology codes for all patients undergoing MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA were used to search a prospectively collected, commercially available private payer insurance company database from 2007 to 2011. Within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery, the database was searched for the occurrence of these same patients undergoing knee diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy, lysis of adhesions, synovectomy, arthroscopy for infection or lavage, arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies, chondroplasty, MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA, and/or knee arthroplasty. Descriptive statistical analysis and contingency table analysis were performed. A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX, 640 ACI, 386 open OATS, 997 arthroscopic OATS, 714 open OCA, and 894 arthroscopic OCA procedures. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. At 2 years, patients who underwent MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA had reoperation rates of 14.65%, 29.69%, 8.82%, and 12.22%, respectively. There was a statistically significantly increased risk for ACI return to OR within all intervals (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative treatment options. With a large US commercial insurance database from 2007 to 2011, reparative procedures were favored for chondral injuries, but yielded an increased risk for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative approaches, yet cell-based approaches yielded a significantly increased risk for a return to the OR.

Continue to: Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage

Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage defects in the knee are difficult to manage, particularly in the young, athletic patient population. Fortunately, a variety of cartilage repair (direct repair of the cartilage or those procedures which attempt to generate fibrocartilage) and restoration (those aimed at restoring hyaline cartilage) procedures are available, with encouraging short- and long-term clinical outcomes. After failure of nonoperative management, several surgical options are available for treating symptomatic focal chondral defects, including microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and open and arthroscopic osteochondral allograft (OCA) transplantation procedures.1,2 When appropriately indicated, each of these techniques has demonstrated good to excellent clinical outcomes with respect to reducing pain and improving function.3-5

While major complications following cartilage surgery are uncommon, the need for reoperation following an index articular cartilage operation is poorly understood. Recently, McCormick and colleagues6 found that reoperation within the first 2 years following meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) is associated with an increased likelihood of revision MAT or future arthroplasty. Given the association between early reoperation following meniscus restoration surgery and subsequent failure, an improved understanding of the epidemiology and implications of reoperations following cartilage restoration surgery is warranted. Further, in deciding which treatment option is best suited to a particular patient, the rate of return to the operating room (OR) should be taken into consideration, as this could potentially influence surgical decision-making as to which procedure to perform, especially in value-based care decision-making environments.

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the OR for knee procedures following cartilage restoration at intervals of 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years across a large-scale US patient database. The authors hypothesize that the rate of return to the OR following knee cartilage repair or restoration procedures will be under 20% during the first post-operative year, with increasing reoperation rates over time. A secondary hypothesis is that there will be no difference in reoperation rates according to sex, but that younger patients (those younger than 40 years) will have higher reoperation rates than older patients.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected, large-scale, and commercially available private payer insurance company database (PearlDiver) from 2007 to 2011. The PearlDiver database is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant, publicly available national database consisting of a collection of private payer records, with United Health Group representing the contributing health plan. The database has more than 30 million patient records and contains Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes related to orthopedic procedures. From 2007 to 2011, the private payer database captured between 5.9 million and 6.2 million patients per year.

Our search was based on the CPT codes for MFX (29879), ACI (27412), OATS (29866, 29867), and OCA (27415, 27416). Return to the OR for revision surgery for the above-mentioned procedures was classified as patients with a diagnosis of diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy (CPT 29870), lysis of adhesions (CPT 29884), synovectomy (29875, 29876), arthroscopy for infection or lavage (CPT 29871), arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies (29874), chondroplasty (29877), unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (27446), total knee arthroplasty (27447), and/or patellar arthroplasty (27438). Patient records were followed for reoperations occurring within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after the index cartilage procedure. All data were compared based on patient age and sex.

Table 1. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Sex | ||||||

MFX | ACI | Open OATS | Arthroscopic OATS | Open OCA | Arthroscopic OCA | |

Females | 20,589 | 276 | 167 | 401 | 275 | 350 |

Males | 22,987 | 364 | 219 | 596 | 439 | 544 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 386 | 997 | 714 | 894 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis of this study was primarily descriptive to demonstrate the incidence for each code at each time interval. One-way analysis of variance, Chi-square analysis, and contingency tables were used to compare the incidence of each type of procedure throughout the various time intervals. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.20 (International Business Machines).

RESULTS

A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX (92.3%) 640 ACI (1.4%), 386 open OATS (0.82%), 997 arthroscopic OATS (2.11%), 714 open OCA (1.51%), and 894 arthroscopic OCA (1.89%) procedures. A summary of the procedures performed, broken down by age and sex, is provided in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 25,149 male patients (53.3%) underwent surgical procedures compared to 22,058 female patients (46.7%). For each category of procedure (MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA), there was a significantly higher proportion of males than females undergoing surgery (P < .0001 for all). Surgical treatment with MFX was consistently the most frequently performed surgery across all age groups (92.31%), while cell-based therapy with ACI was the least frequently performed procedure across all age ranges (1.36%). Restorative OATS and OCA techniques were performed with the greatest frequency in the 15-year-old to 19-year-old age group, but were not utilized in patients over 64 years of age (Table 2).

Table 2. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Age | ||||

Age (y) | MFX | ACI | OATS | OCA |

10 to 14 | 572 | 22 | 74 | 47 |

15 to 19 | 1984 | 83 | 254 | 235 |

20 to 24 | 1468 | 54 | 140 | 144 |

25 to 29 | 1787 | 74 | 152 | 176 |

30 to 34 | 2824 | 114 | 152 | 204 |

35 to 39 | 4237 | 96 | 153 | 210 |

40 to 44 | 5441 | 103 | 166 | 217 |

45 to 49 | 7126 | 57 | 149 | 180 |

50 to 54 | 7004 | 25 | 83 | 140 |

55 to 59 | 6410 | 12 | 40 | 40 |

60 to 64 | 4409 | 0 | 20 | 15 |

65 to 69 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

70 to 74 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 1383 | 1608 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

A summary of all reoperation data is provided in Tables 3 to 7 and Figures 1 and 2. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. Patients who underwent MFX had reoperation rates of 6.05% at 90 days, 11.80% at 1 year, and 14.65% at 2 years. Patients who underwent ACI had reoperation rates of 4.53% at 90 days, 23.28% at 1 year, and 29.69% at 2 years. Patients who had open and arthroscopic OATS had reoperation rates of 3.122% and 5.12% at 90 days, 6.74% and 8.53% at 1 year, and 7.51% and 10.13% at 2 years, respectively. Patients who underwent open and arthroscopic OCA had reoperation rates of 2.52% and 3.91% at 90 days, 7.14% and 6.60% at 1 year, and 13.59% and 10.85% at 2 years (Table 3). There was a statistically significantly increased risk for reoperation following ACI within all intervals compared to all other surgical techniques (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty at 6.70%. There was no significant difference between failure rates (revision OATS/OCA or conversion to arthroplasty) between the restorative treatment options, with 14 failures for OATS (9.52% of reoperations at 2 years) compared to 22 failures for OCA (12.7% of reoperations at 2 years, P = .358). Among the entire cohort of cartilage surgery patients, arthroscopic chondroplasty was the most frequent procedure performed at the time of reoperation at all time points assessed, notably accounting for 33.08% of reoperations 2 years following microfracture, 51.58% of reoperations at 2 years following ACI, 53.06% of reoperations at 2 years following OATS, and 54.07% of reoperations at 2 years following OCA (Figure 3, Tables 4–7).

Table 3. Comparison of Return to OR Following MFX, ACI, OCA, and OATS | |||||||

Procedure | Total No. of Cases in Study Period | No. of Reoperations at 90 Days | Return to OR Rate at 90 Days | No. of Reoperations at 1 Year | Return to OR Rate at 1 Year | No. of Reoperations at 2 Years | Return to OR Rate at 2 Years |

MFX | 43,576 | 2636 | 6.05% | 5142 | 11.80% | 6385 | 14.65% |

ACI | 640 | 29 | 4.53% | 149 | 23.28% | 190 | 29.69% |

Open OATS | 386 | 12 | 3.12% | 26 | 6.74% | 29 | 7.51% |

Arthroscopic OATS | 997 | 51 | 5.12% | 85 | 8.53% | 101 | 10.13% |

Open OCA | 714 | 18 | 2.52% | 51 | 7.14% | 97 | 13.59% |

Arthroscopic OCA | 894 | 161 | 3.91% | 59 | 6.60% | 97 | 10.85% |

Weighted average for all procedures |

| 5.87% |

| 11.94% |

| 14.90% | |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 4. Rate of Return to OR Following MFX (n = 43,574) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 54 | 122 | 162 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 84 | 102 | 104 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 300 | 468 | 549 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 324 | 528 | 611 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 557 | 926 | 1087 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 1063 | 1722 | 2112 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 61 | 129 | 171 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 38 | 49 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 51 | 242 | 328 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 142 | 865 | 1212 |

Total | 2636 | 5142 | 6385 | |

Return to OR | 6.05% | 11.80% | 14.65% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; MFX, microfracture; OR, operating room.

Table 5. Rate of Return to OR Following ACI (n = 640) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Daysa | 1 Yeara | 2 Yearsa |

Revision ACI | 27412 | 29 | 33 | 35 |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | -1 | 12 | 20 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | -1 | 71 | 98 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | -1 | 33 | 37 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Total | 29 | 149 | 190 | |

Return to OR | 4.53% | 23.28% | 29.69% | |

aA -1 denotes No. <11 within the PearlDiver database, and exact numbers are not reported due to patient privacy considerations.

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OR, operating room.

Table 6. Rate of Return to OR Following OATS (n = 1320) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 12 | 13 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 16 | 25 | 28 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 17 | 58 | 78 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Total | 33 | 95 | 147 | |

Return to OR | 2.50% | 7.20% | 11.14% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 7. Rate of Return to OR Following OCA Transplantation (n = 1531) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Year |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 15 | 19 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 0 | 20 | 38 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 22 | 59 | 93 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

Total | 22 | 94 | 172 | |

Return to OR | 1.44% | 6.14% | 11.23% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OR, operating room.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION

The principle findings of this study demonstrate that there is an overall reoperation rate of 14.90% at 2 years following cartilage repair/restoration surgery, with the highest reoperation rates following MFX at 90 days, and ACI at both 1 year and 2 years following the index procedure. Also, patients undergoing index MFX as the index procedure have the highest risk for conversion to arthroplasty, reoperation rates for all cartilage surgeries increase over time, and arthroscopic chondroplasty is the most frequent procedure performed at the time of reoperation.

The management of symptomatic articular cartilage knee pathology is extremely challenging. With improvements in surgical technique, instrumentation, and clinical decision-making, indications are constantly evolving. Techniques that may work for “small” defects, though there is some debate as to what constitutes a “small” defect, are not necessarily going to be successful for larger defects, and this certainly varies depending on where the defect is located within the knee joint (distal femur vs patella vs trochlea, etc.). Recently, in a 2015 analysis of 3 level I or II studies, Miller and colleagues7 demonstrated both MFX and OATS to be viable, cost-effective, first-line treatment options for articular cartilage injuries, with similar clinical outcomes at 8.7 years. The authors noted cumulative reoperation rates of 29% among patients undergoing MFX compared to 13% among patients undergoing OATS. While ACI and OCA procedures were not included in their study, the reported reoperation rates of 29% following MFX and 13% following OATS at nearly 10 years suggest a possible increased need for reoperation following MFX over time (approximately 15% at 2 years in our study) and a stable rate of reoperation following OATS (approximately 11% at 2 years in our study). This finding is significant, as one of the goals with these procedures is to deliver effective, long-lasting pain relief and restoration of function. Interestingly, in this study, restorative OATS and OCA techniques were performed with the greatest frequency in the 15-year-old to 19-year-old age group, but were not performed in patients older than 64 years. This may be explained by the higher prevalence of acute traumatic injuries and osteochondritis dissecans diagnoses in younger patients compared with older patients, as these diagnoses are more often indicated to undergo restorative procedures as opposed to marrow stimulation.

In a 2016 systematic review of 20 studies incorporating 1117 patients, Campbell and colleagues8 assessed return-to-play rates following MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA. The authors noted that return to sport (RTS) rates were greatest following OATS (89%), followed by OCA (88%), ACI (84%), and MFX (75%). Positive prognostic factors for RTS included younger age, shorter duration of preoperative symptoms, no history of prior ipsilateral knee surgery, and smaller chondral defects. Reoperation rates between the 4 techniques were not statistically compared in their study. Interestingly, in 2013, Chalmers and colleagues9 conducted a separate systematic review of 20 studies comprising 1375 patients undergoing MFX, ACI, or OATS. In their study, the authors found significant advantages following ACI and OATS compared to MFX with respect to patient-reported outcome scores but noted significantly faster RTS rates with MFX. Reoperation rates were noted to be similar between the 3 procedures (25% for ACI, 21% for MFX, and 28% for OATS) at an average 3.7 years following the index procedure. When considering these 2 systematic reviews together, despite a faster RTS rate following MFX, a greater proportion of patients seem to be able to RTS over time following other procedures such as OATS, OCA, and ACI. Unfortunately, these reviews do not provide insight as to the role, if any, of reoperation on return to play rates nor on overall clinical outcome scores on patients undergoing articular cartilage surgery. However, this information is valuable when counseling athletes who are in season and would like to RTS as soon as possible as opposed to those who do not have tight time constraints for when they need to RTS.

Regardless of the cartilage technique chosen, the goals of surgery remain similar—to reduce pain and improve function. For athletes, the ultimate goal is to return to the same level of play that the athlete was able to achieve prior to injury. Certainly, the need for reoperation following a cartilage surgery has implications on pain, function, and ability to RTS. Our review of nearly 50,000 cartilage surgeries demonstrates that reoperations following cartilage repair surgery are not uncommon, with a rate of 14.90% at 2 years, and that while reoperation rates are the highest following ACI, the rate of conversion to knee arthroplasty is highest following MFX. Due to the limitations of the PearlDiver database, it is not possible to determine the clinical outcomes of patients undergoing reoperation following cartilage surgery, but certainly, given these data, reoperation is clearly not necessarily indicative of clinical failure. This is highlighted by the fact that the most common procedure performed at the time of reoperation is arthroscopic chondroplasty, which, despite being an additional surgical procedure, may be acceptable for patients who wish to RTS, particularly in the setting of an index ACI in which there may be graft hypertrophy. Ideally, additional studies incorporating a cost-effectiveness analysis of each of the procedures, incorporating reoperation rates as well as patient-reported clinical outcomes, would be helpful to truly determine the patient and societal implications of reoperation following cartilage repair/restoration.

Many of the advantages and disadvantages of the described cartilage repair/restoration procedures have been well described.10-17 Microfracture is the most commonly utilized first-line repair/restoration option for small articular cartilage lesions, mainly due to its low cost, low morbidity, and relatively low level of difficulty.18 Despite these advantages, MFX is not without limitations, and the need for revision cartilage restoration and/or conversion to arthroplasty is concerning. In 2013, Salzmann and colleagues19 evaluated a cohort of 454 patients undergoing MFX for a symptomatic knee defect and noted a reoperation rate of 26.9% (n = 123) within 2 years of the index surgery, with risk factors for reoperation noted to include an increased number of pre-MFX ipsilateral knee surgeries, patellofemoral lesions, smoking, and lower preoperative numeric analog scale scores. The definition of reoperation in their study is unfortunately not described, and thus the extent of reoperation (arthroscopy to arthroplasty) is unclear. In a 2009 systematic review of 3122 patients (28 studies) undergoing MFX conducted by Mithoefer and colleagues,20 revision rates were noted to range from 2% to 31% depending on the study analyzed, with increasing revision rates after 2 years. Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of the included studies makes it difficult to determine which patients tend to fail over time.

Continue to: OATS...

OATS is a promising cartilage restoration technique indicated for treatment of patients with large, uncontained chondral lesions, and/or lesions with both bone and cartilage loss.1 OCA is similar to OATS but uses allograft tissue instead of autograft tissue and is typically considered a viable treatment option in larger lesions (>2 cm2).21 Cell-based ACI therapy has evolved substantially over the past decade and is now available as a third-generation model utilizing biodegradable 3-dimensional scaffolds seeded with chondrocytes. Reoperation rates following ACI can often be higher than those following other cartilage treatments, particularly given the known complication of graft hypertrophy and/or delamination. Harris and colleagues22 conducted a systematic review of 5276 subjects undergoing ACI (all generations), noting an overall reoperation rate of 33%, but a failure rate of 5.8% at an average of 22 months following ACI. Risk factors for reoperation included periosteal-based ACI as well as open (vs arthroscopic) ACI. In this study, we found a modestly lower return to OR rate of 29.69% at 2 years.

When the outcomes of patients undergoing OATS or OCA are compared to those of patients undergoing MFX or ACI, it can be difficult to interpret the results, as the indications for performing these procedures tend to be very different. Further, the reasons for reoperation, as well as the procedures performed at the time of reoperation, are often poorly described, making it difficult to truly quantify the risk of reoperation and the implications of reoperation for patients undergoing any of these index cartilage procedures.

Overall, in this database, the return to the OR rate approaches 15% at 2 years following cartilage surgery, with cell-based therapy demonstrating higher reoperation rates at 2 years, without the risk of conversion to arthroplasty. Reoperation rates appear to stabilize at 1 year following surgery and consist mostly of minor arthroscopic procedures. These findings can help surgeons counsel patients as to the rate and type of reoperations that can be expected following cartilage surgery. Additional research incorporating patient-reported outcomes and patient-specific risk factors are needed to complement these data as to the impact of reoperations on overall clinical outcomes. Further, studies incorporating 90-day, 1-year, and 2-year costs associated with cartilage surgery will help to determine which index procedure is the most cost effective over the short- and long-term.

LIMITATIONS

This study is not without limitations. The PearlDiver database is reliant upon accurate CPT and ICD-9 coding, which creates a potential for a reporting bias. The overall reliability of the analyses is dependent on the quality of the available data, which, as noted in previous PearlDiver studies,18,23-28 may include inaccurate billing codes, miscoding, and/or non-coding by physicians as potential sources of error. At the time of this study, the PearlDiver database did not provide consistent data points on laterality, and thus it is possible that the reported rates of reoperation overestimate the true reoperation rate following a given procedure. Fortunately, the reoperation rates for each procedure analyzed in this database study are consistent with those previously presented in the literature. In addition, it is not uncommon for patients receiving one of these procedures to have previously been treated with one of the others. Due to the inherent limitations of the PearlDiver database, this study did not investigate concomitant procedures performed along with the index procedure, nor did it investigate confounding factors such as comorbidities. The PearlDiver database does not provide data on defect size, location within the knee, concomitant pathologies (eg, meniscus tear), prior surgeries, or patient comorbidities, and while important, these factors cannot be accounted for in our analysis. The inability to account for these important factors, particularly concomitant diagnoses, procedures, and lesion size/location, represents an important limitation of this study, as this is a source of selection bias and may influence the need for reoperation in a given patient. Despite these limitations, the results of this study are supported by previous and current literature. In addition, the PearlDiver database, as a HIPAA-compliant database, does not report exact numbers when the value of the outcome of interest is between 0 and 10, which prohibits analysis of any cartilage procedure performed in a cohort of patients greater than 1 and less than 11. Finally, while not necessarily a limitation, it should be noted that CPT 29879 is not specific for microfracture, as the code also includes abrasion arthroplasty and drilling. Due to the limitations of the methodology of searching the database for this code, it is unclear as to how many patients underwent actual microfracture vs abrasion arthroplasty.

CONCLUSION

Within a large US commercial insurance database from 2007 to 2011, reparative procedures were favored for chondral injuries, but yielded an increased risk for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference between failure/revision rates among the restorative approaches, yet cell-based approaches yielded a significantly increased risk for a return to the OR.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the operating room (OR) following microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and osteochondral allograft (OCA) procedures at 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years. Current Procedural Terminology codes for all patients undergoing MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA were used to search a prospectively collected, commercially available private payer insurance company database from 2007 to 2011. Within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery, the database was searched for the occurrence of these same patients undergoing knee diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy, lysis of adhesions, synovectomy, arthroscopy for infection or lavage, arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies, chondroplasty, MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA, and/or knee arthroplasty. Descriptive statistical analysis and contingency table analysis were performed. A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX, 640 ACI, 386 open OATS, 997 arthroscopic OATS, 714 open OCA, and 894 arthroscopic OCA procedures. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. At 2 years, patients who underwent MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA had reoperation rates of 14.65%, 29.69%, 8.82%, and 12.22%, respectively. There was a statistically significantly increased risk for ACI return to OR within all intervals (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative treatment options. With a large US commercial insurance database from 2007 to 2011, reparative procedures were favored for chondral injuries, but yielded an increased risk for conversion to arthroplasty. There was no difference in failure/revision rates between the restorative approaches, yet cell-based approaches yielded a significantly increased risk for a return to the OR.

Continue to: Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage

Symptomatic, full-thickness articular cartilage defects in the knee are difficult to manage, particularly in the young, athletic patient population. Fortunately, a variety of cartilage repair (direct repair of the cartilage or those procedures which attempt to generate fibrocartilage) and restoration (those aimed at restoring hyaline cartilage) procedures are available, with encouraging short- and long-term clinical outcomes. After failure of nonoperative management, several surgical options are available for treating symptomatic focal chondral defects, including microfracture (MFX), autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS), and open and arthroscopic osteochondral allograft (OCA) transplantation procedures.1,2 When appropriately indicated, each of these techniques has demonstrated good to excellent clinical outcomes with respect to reducing pain and improving function.3-5

While major complications following cartilage surgery are uncommon, the need for reoperation following an index articular cartilage operation is poorly understood. Recently, McCormick and colleagues6 found that reoperation within the first 2 years following meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) is associated with an increased likelihood of revision MAT or future arthroplasty. Given the association between early reoperation following meniscus restoration surgery and subsequent failure, an improved understanding of the epidemiology and implications of reoperations following cartilage restoration surgery is warranted. Further, in deciding which treatment option is best suited to a particular patient, the rate of return to the operating room (OR) should be taken into consideration, as this could potentially influence surgical decision-making as to which procedure to perform, especially in value-based care decision-making environments.

The purpose of this study is to describe the rate of return to the OR for knee procedures following cartilage restoration at intervals of 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years across a large-scale US patient database. The authors hypothesize that the rate of return to the OR following knee cartilage repair or restoration procedures will be under 20% during the first post-operative year, with increasing reoperation rates over time. A secondary hypothesis is that there will be no difference in reoperation rates according to sex, but that younger patients (those younger than 40 years) will have higher reoperation rates than older patients.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected, large-scale, and commercially available private payer insurance company database (PearlDiver) from 2007 to 2011. The PearlDiver database is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant, publicly available national database consisting of a collection of private payer records, with United Health Group representing the contributing health plan. The database has more than 30 million patient records and contains Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes related to orthopedic procedures. From 2007 to 2011, the private payer database captured between 5.9 million and 6.2 million patients per year.

Our search was based on the CPT codes for MFX (29879), ACI (27412), OATS (29866, 29867), and OCA (27415, 27416). Return to the OR for revision surgery for the above-mentioned procedures was classified as patients with a diagnosis of diagnostic arthroscopy with biopsy (CPT 29870), lysis of adhesions (CPT 29884), synovectomy (29875, 29876), arthroscopy for infection or lavage (CPT 29871), arthroscopy for removal of loose bodies (29874), chondroplasty (29877), unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (27446), total knee arthroplasty (27447), and/or patellar arthroplasty (27438). Patient records were followed for reoperations occurring within 90 days, 1 year, and 2 years after the index cartilage procedure. All data were compared based on patient age and sex.

Table 1. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Sex | ||||||

MFX | ACI | Open OATS | Arthroscopic OATS | Open OCA | Arthroscopic OCA | |

Females | 20,589 | 276 | 167 | 401 | 275 | 350 |

Males | 22,987 | 364 | 219 | 596 | 439 | 544 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 386 | 997 | 714 | 894 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis of this study was primarily descriptive to demonstrate the incidence for each code at each time interval. One-way analysis of variance, Chi-square analysis, and contingency tables were used to compare the incidence of each type of procedure throughout the various time intervals. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.20 (International Business Machines).

RESULTS

A total of 47,207 cartilage procedures were performed from 2007 to 2011, including 43,576 MFX (92.3%) 640 ACI (1.4%), 386 open OATS (0.82%), 997 arthroscopic OATS (2.11%), 714 open OCA (1.51%), and 894 arthroscopic OCA (1.89%) procedures. A summary of the procedures performed, broken down by age and sex, is provided in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 25,149 male patients (53.3%) underwent surgical procedures compared to 22,058 female patients (46.7%). For each category of procedure (MFX, ACI, OATS, OCA), there was a significantly higher proportion of males than females undergoing surgery (P < .0001 for all). Surgical treatment with MFX was consistently the most frequently performed surgery across all age groups (92.31%), while cell-based therapy with ACI was the least frequently performed procedure across all age ranges (1.36%). Restorative OATS and OCA techniques were performed with the greatest frequency in the 15-year-old to 19-year-old age group, but were not utilized in patients over 64 years of age (Table 2).

Table 2. Breakdown of MFX, ACI, OATS, and OCA Procedures by Age | ||||

Age (y) | MFX | ACI | OATS | OCA |

10 to 14 | 572 | 22 | 74 | 47 |

15 to 19 | 1984 | 83 | 254 | 235 |

20 to 24 | 1468 | 54 | 140 | 144 |

25 to 29 | 1787 | 74 | 152 | 176 |

30 to 34 | 2824 | 114 | 152 | 204 |

35 to 39 | 4237 | 96 | 153 | 210 |

40 to 44 | 5441 | 103 | 166 | 217 |

45 to 49 | 7126 | 57 | 149 | 180 |

50 to 54 | 7004 | 25 | 83 | 140 |

55 to 59 | 6410 | 12 | 40 | 40 |

60 to 64 | 4409 | 0 | 20 | 15 |

65 to 69 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

70 to 74 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Total | 43,576 | 640 | 1383 | 1608 |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation.

A summary of all reoperation data is provided in Tables 3 to 7 and Figures 1 and 2. The weighted average reoperation rates for all procedures were 5.87% at 90 days, 11.94% at 1 year, and 14.90% at 2 years following the index cartilage surgery. Patients who underwent MFX had reoperation rates of 6.05% at 90 days, 11.80% at 1 year, and 14.65% at 2 years. Patients who underwent ACI had reoperation rates of 4.53% at 90 days, 23.28% at 1 year, and 29.69% at 2 years. Patients who had open and arthroscopic OATS had reoperation rates of 3.122% and 5.12% at 90 days, 6.74% and 8.53% at 1 year, and 7.51% and 10.13% at 2 years, respectively. Patients who underwent open and arthroscopic OCA had reoperation rates of 2.52% and 3.91% at 90 days, 7.14% and 6.60% at 1 year, and 13.59% and 10.85% at 2 years (Table 3). There was a statistically significantly increased risk for reoperation following ACI within all intervals compared to all other surgical techniques (P < .0001); however, MFX had a greater risk factor (P < .0001) for conversion to arthroplasty at 6.70%. There was no significant difference between failure rates (revision OATS/OCA or conversion to arthroplasty) between the restorative treatment options, with 14 failures for OATS (9.52% of reoperations at 2 years) compared to 22 failures for OCA (12.7% of reoperations at 2 years, P = .358). Among the entire cohort of cartilage surgery patients, arthroscopic chondroplasty was the most frequent procedure performed at the time of reoperation at all time points assessed, notably accounting for 33.08% of reoperations 2 years following microfracture, 51.58% of reoperations at 2 years following ACI, 53.06% of reoperations at 2 years following OATS, and 54.07% of reoperations at 2 years following OCA (Figure 3, Tables 4–7).

Table 3. Comparison of Return to OR Following MFX, ACI, OCA, and OATS | |||||||

Procedure | Total No. of Cases in Study Period | No. of Reoperations at 90 Days | Return to OR Rate at 90 Days | No. of Reoperations at 1 Year | Return to OR Rate at 1 Year | No. of Reoperations at 2 Years | Return to OR Rate at 2 Years |

MFX | 43,576 | 2636 | 6.05% | 5142 | 11.80% | 6385 | 14.65% |

ACI | 640 | 29 | 4.53% | 149 | 23.28% | 190 | 29.69% |

Open OATS | 386 | 12 | 3.12% | 26 | 6.74% | 29 | 7.51% |

Arthroscopic OATS | 997 | 51 | 5.12% | 85 | 8.53% | 101 | 10.13% |

Open OCA | 714 | 18 | 2.52% | 51 | 7.14% | 97 | 13.59% |

Arthroscopic OCA | 894 | 161 | 3.91% | 59 | 6.60% | 97 | 10.85% |

Weighted average for all procedures |

| 5.87% |

| 11.94% |

| 14.90% | |

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFX, microfracture; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 4. Rate of Return to OR Following MFX (n = 43,574) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 54 | 122 | 162 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 84 | 102 | 104 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 300 | 468 | 549 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 324 | 528 | 611 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 557 | 926 | 1087 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 1063 | 1722 | 2112 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 61 | 129 | 171 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 38 | 49 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 51 | 242 | 328 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 142 | 865 | 1212 |

Total | 2636 | 5142 | 6385 | |

Return to OR | 6.05% | 11.80% | 14.65% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; MFX, microfracture; OR, operating room.

Table 5. Rate of Return to OR Following ACI (n = 640) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Daysa | 1 Yeara | 2 Yearsa |

Revision ACI | 27412 | 29 | 33 | 35 |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | -1 | 12 | 20 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | -1 | 71 | 98 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | -1 | 33 | 37 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | -1 | -1 |

Total | 29 | 149 | 190 | |

Return to OR | 4.53% | 23.28% | 29.69% | |

aA -1 denotes No. <11 within the PearlDiver database, and exact numbers are not reported due to patient privacy considerations.

Abbreviations: ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OR, operating room.

Table 6. Rate of Return to OR Following OATS (n = 1320) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Years |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 12 | 13 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 16 | 25 | 28 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 17 | 58 | 78 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

Total | 33 | 95 | 147 | |

Return to OR | 2.50% | 7.20% | 11.14% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OATS, osteochondral autograft transplantation; OR, operating room.

Table 7. Rate of Return to OR Following OCA Transplantation (n = 1531) | ||||

Procedure | CPT Code | 90 Days | 1 Year | 2 Year |

Knee arthroscopy | 29870 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Knee arthroscopic drainage and lavage | 29871 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Arthroscopic adhesions débridement | 29874 | 0 | 15 | 19 |

Arthroscopic synovectomy | 29875 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Major arthroscopic synovectomy | 29876 | 0 | 20 | 38 |

Knee arthroscopic chondroplasty | 29877 | 22 | 59 | 93 |

Arthroscopic lysis of adhesions | 29884 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Patellar arthroplasty | 27438 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial or lateral knee arthroplasty | 27446 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Medial and lateral knee arthroplasty | 27447 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

Total | 22 | 94 | 172 | |

Return to OR | 1.44% | 6.14% | 11.23% | |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; OCA, osteochondral allograft; OR, operating room.

Continue to: Discussion...

DISCUSSION